Optimizing S20C Steel and SUS201 Steel Welding Using Stainless Steel Filler and MIG Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

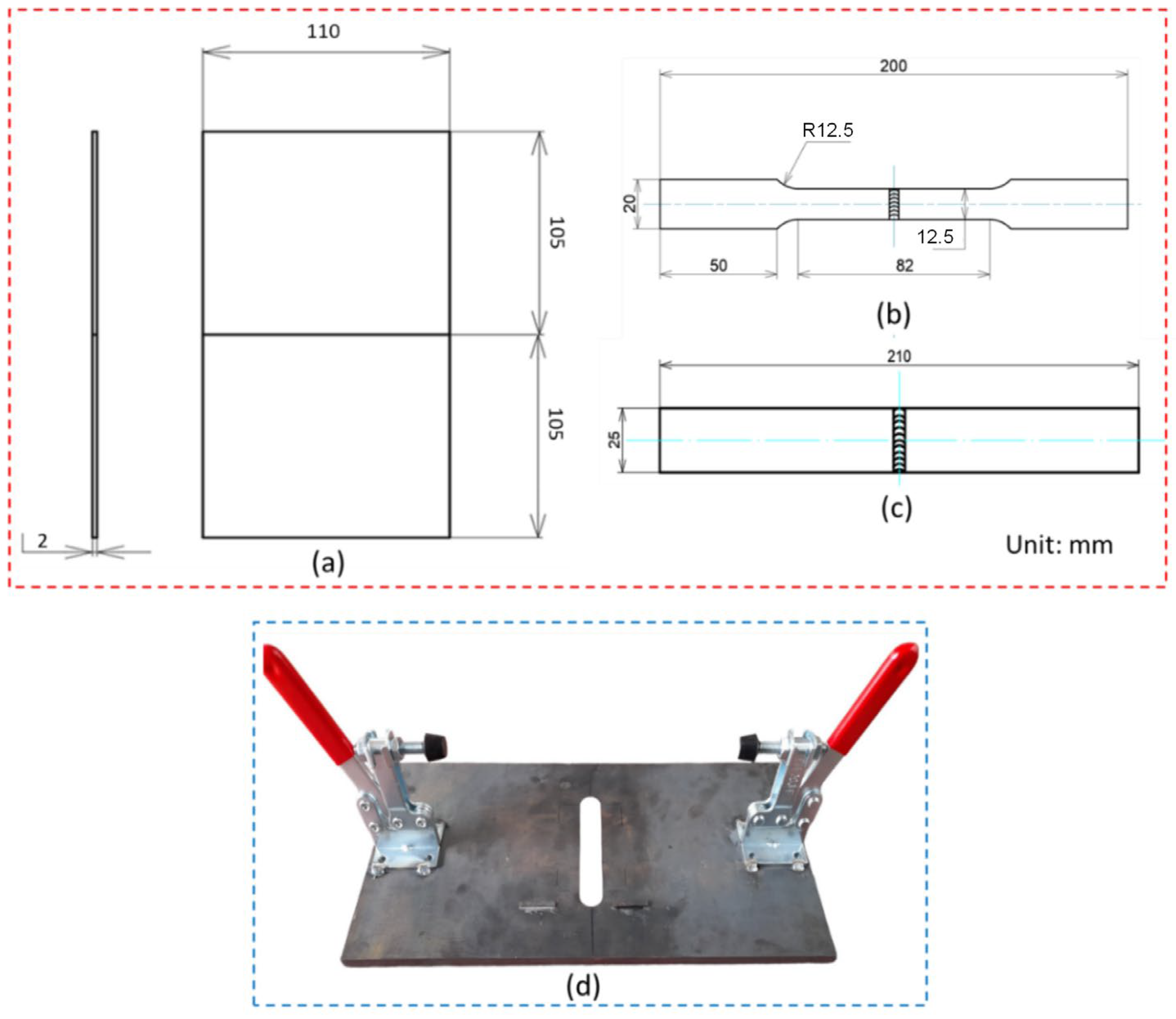

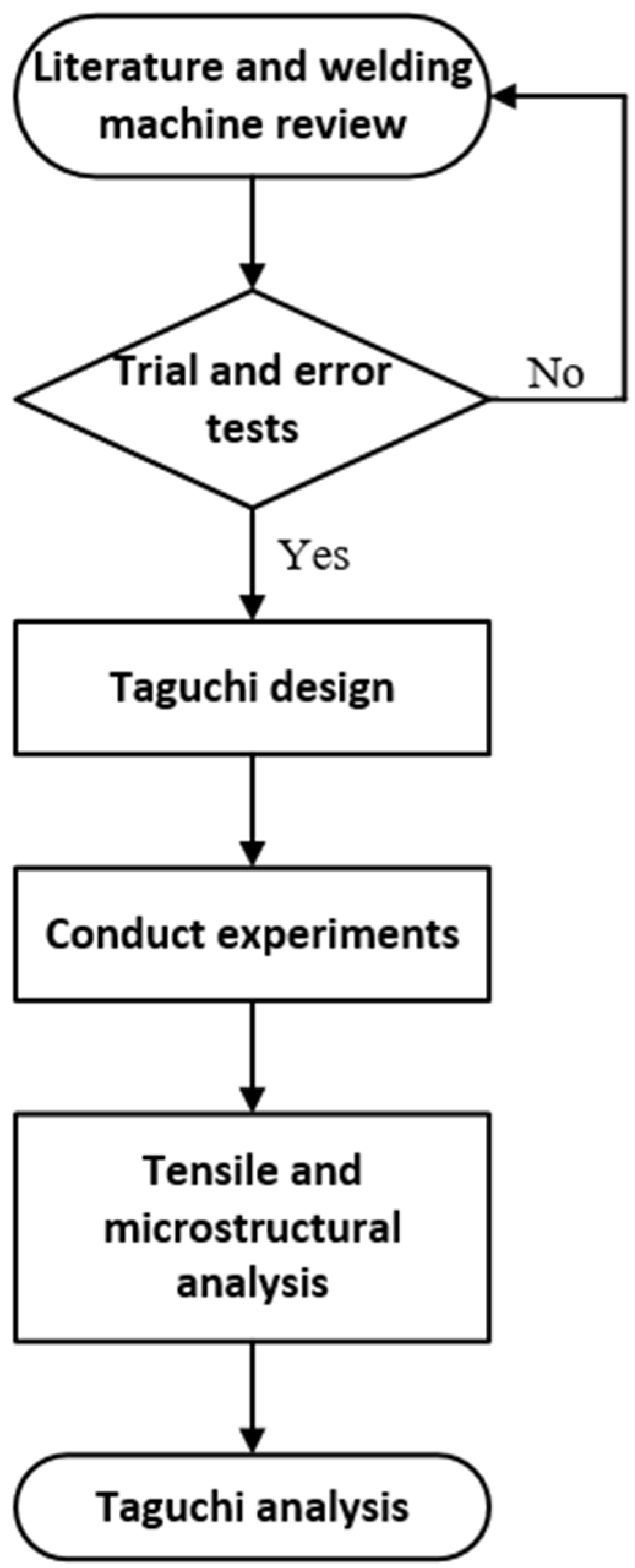

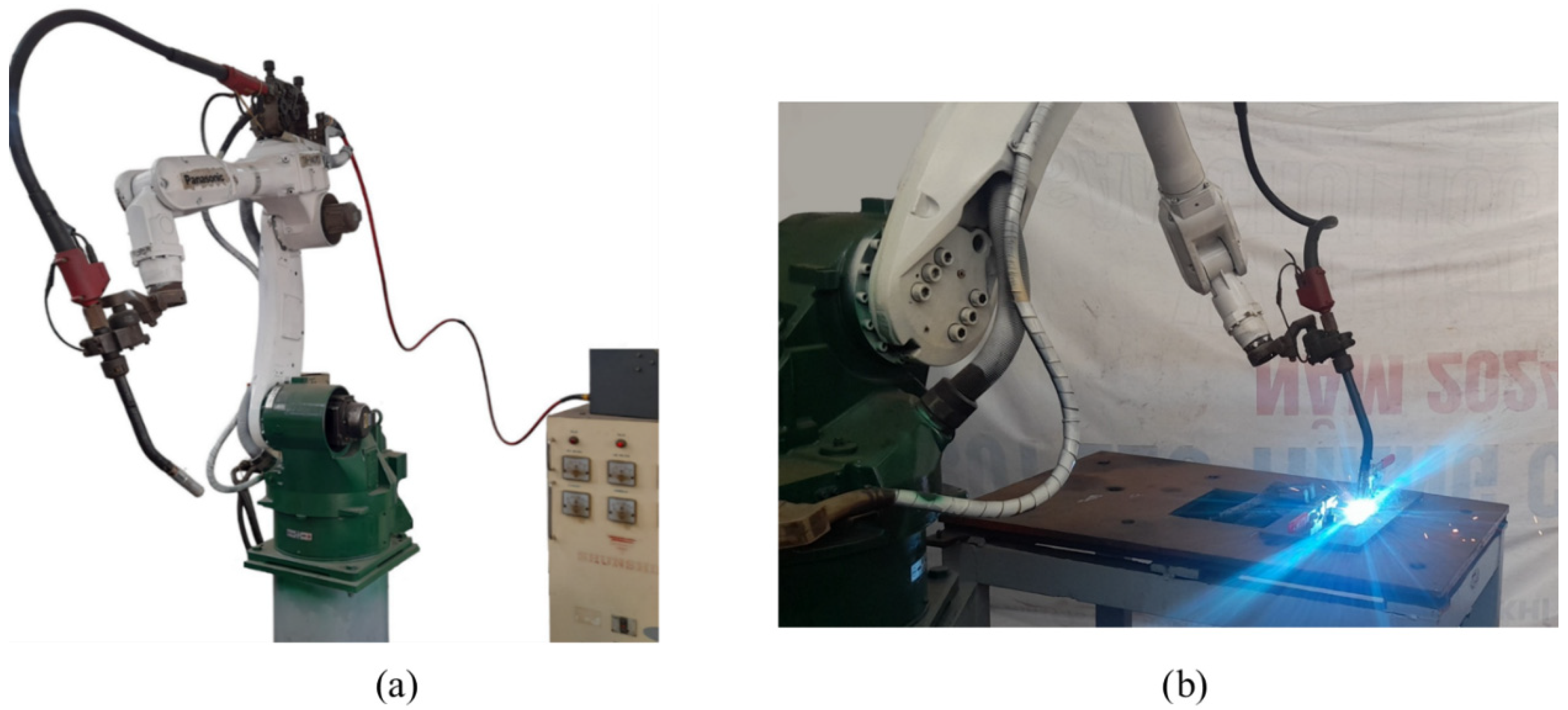

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

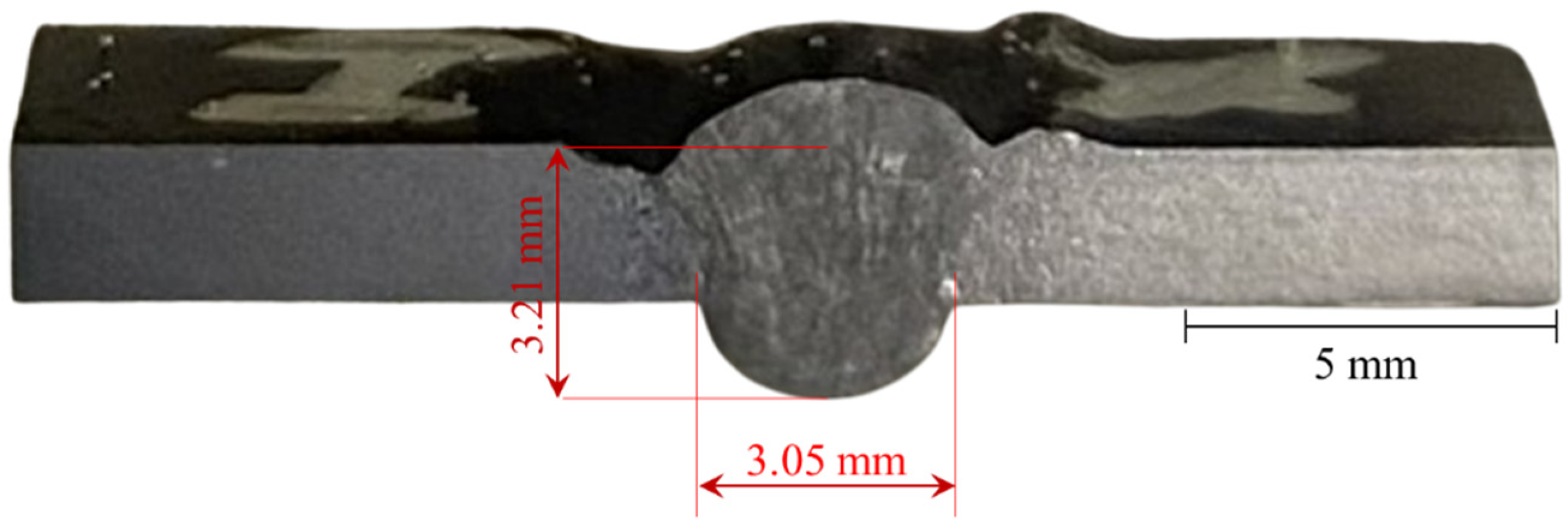

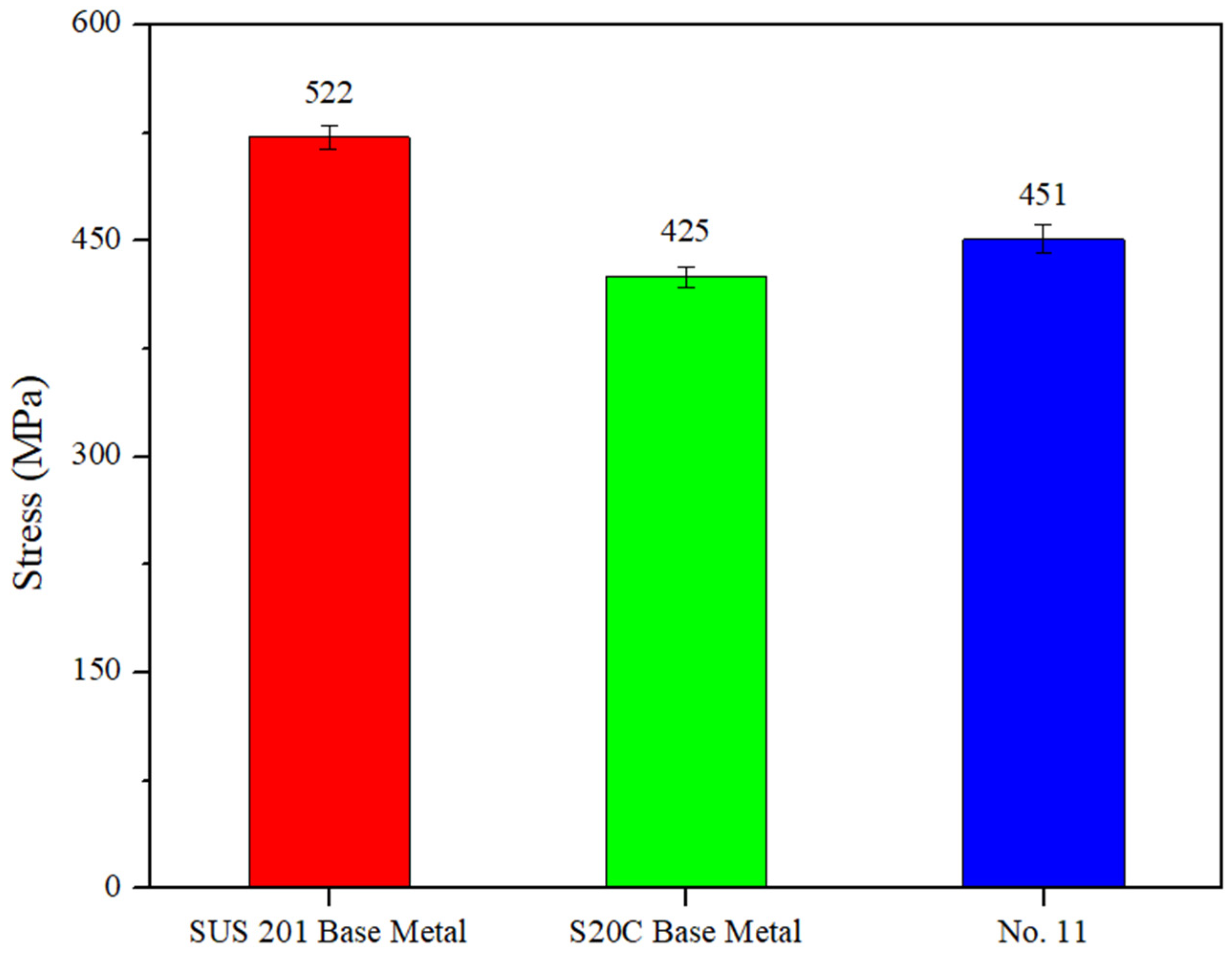

3.1. Tensile Properties

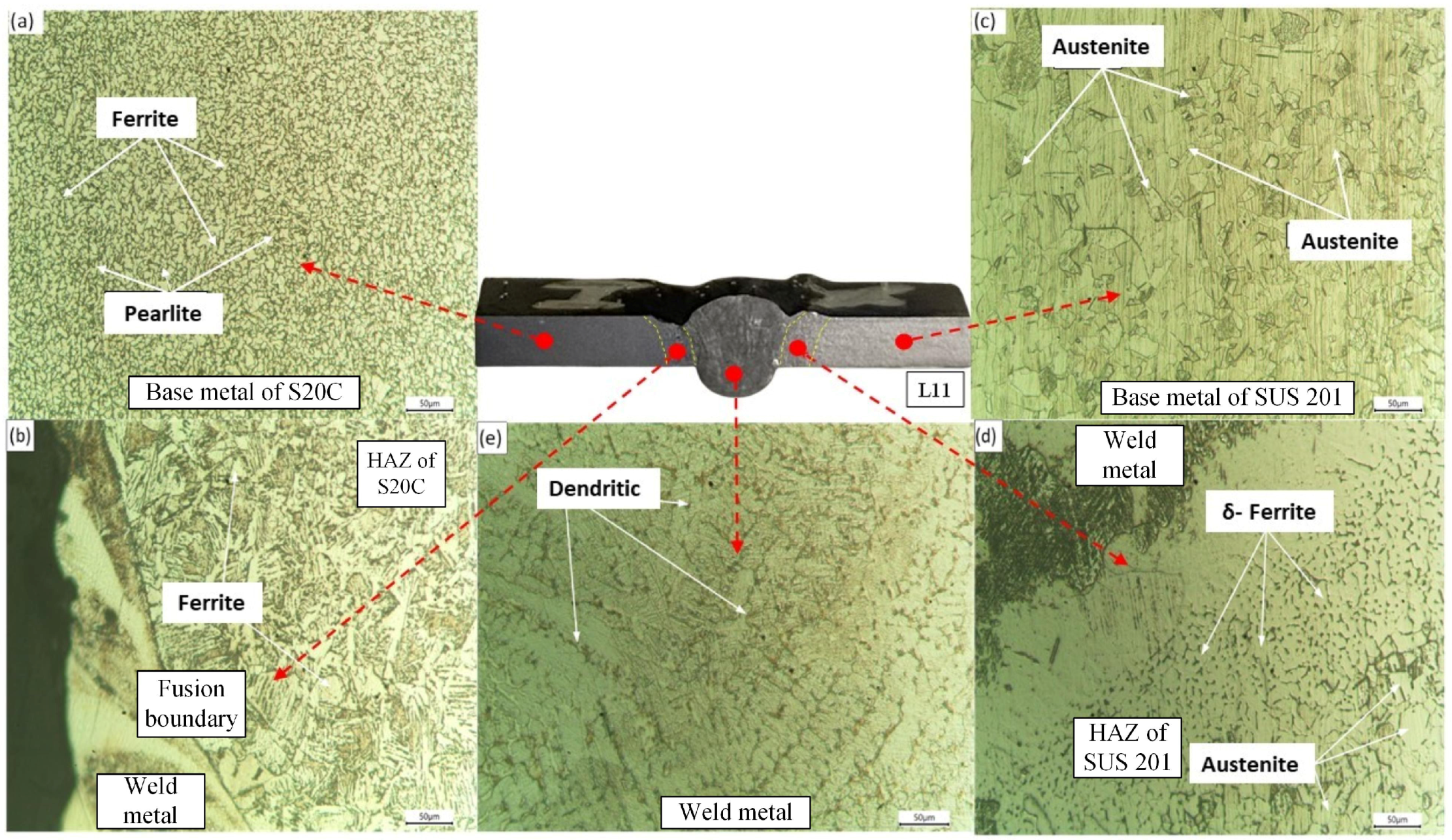

3.2. Microstructure

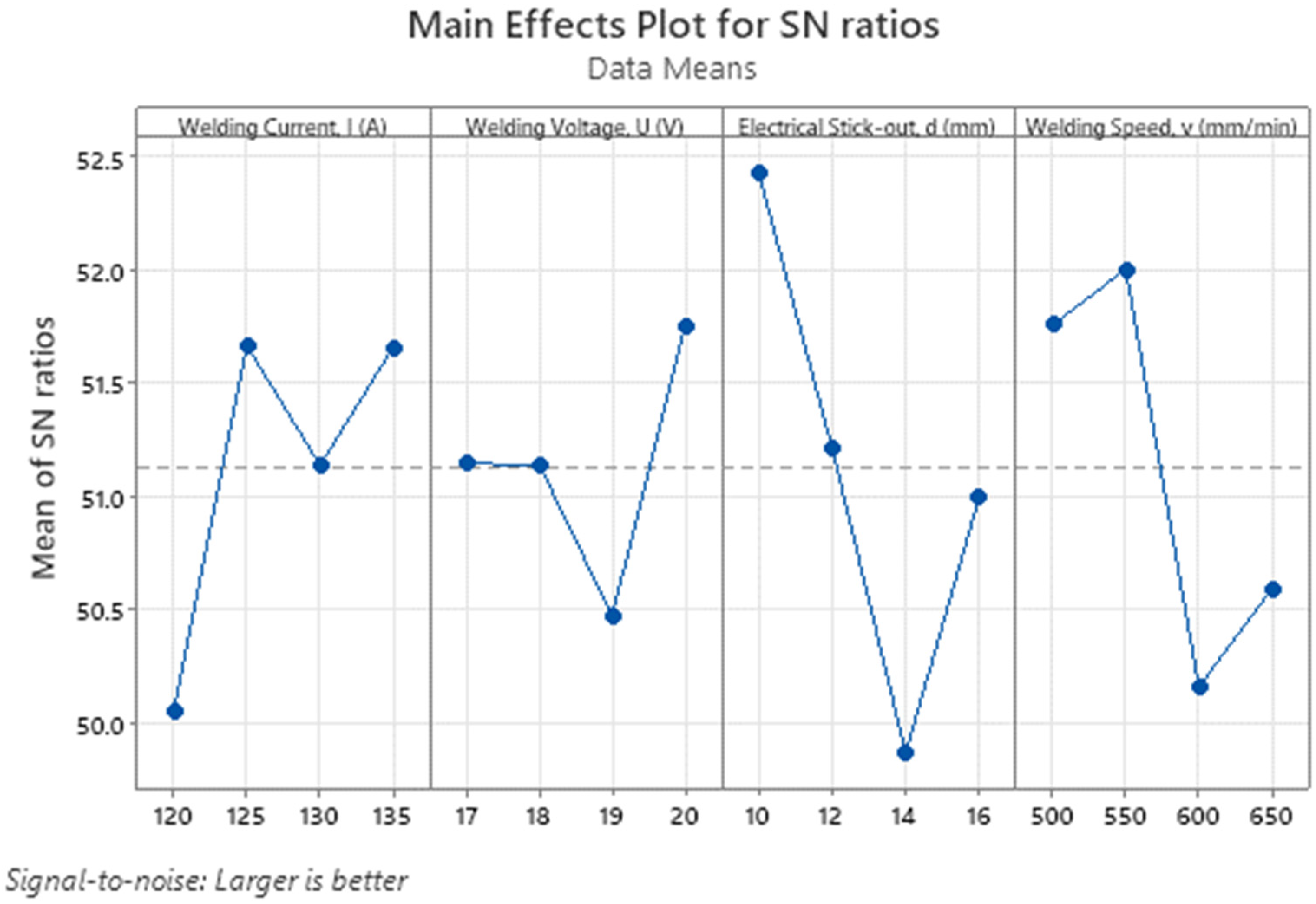

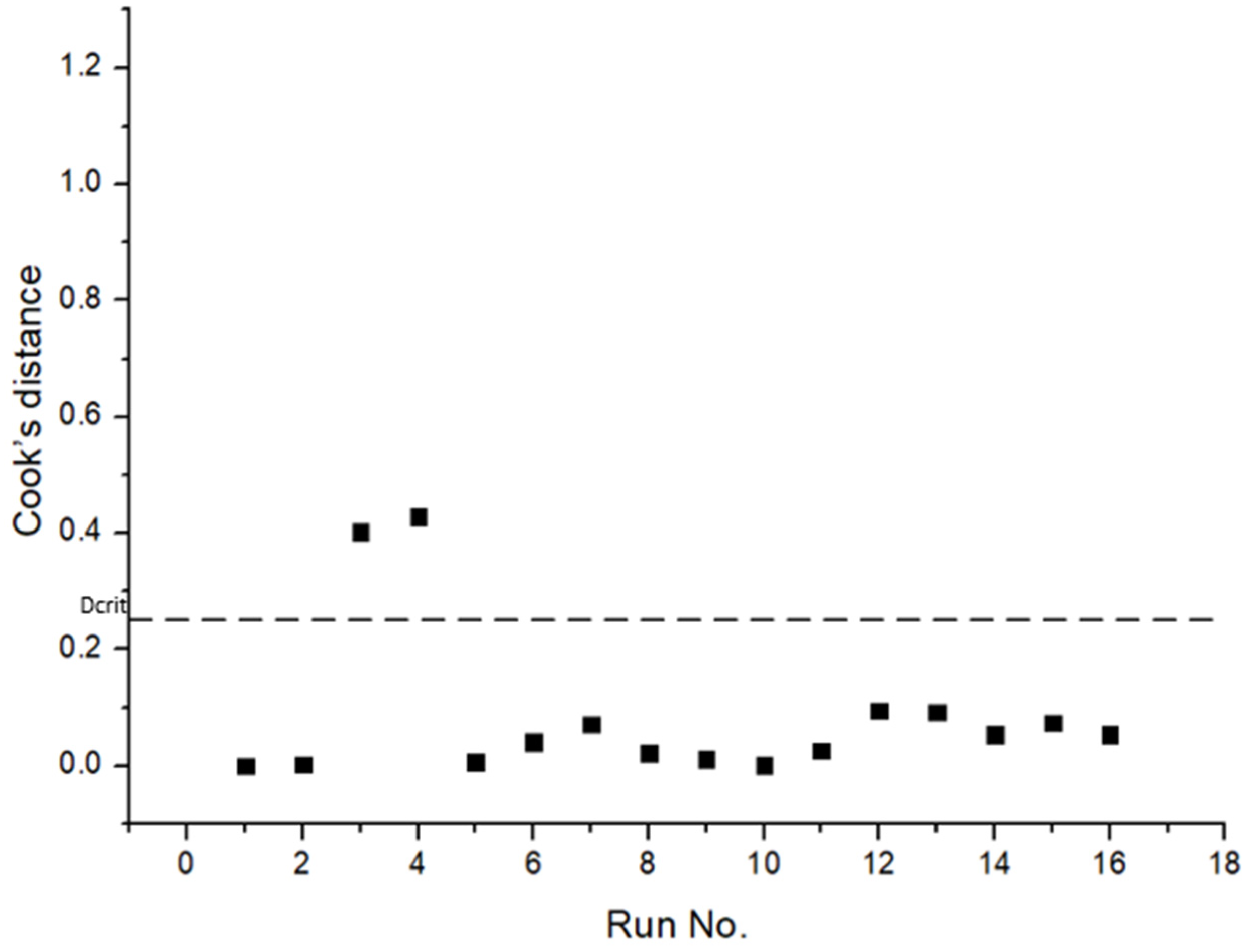

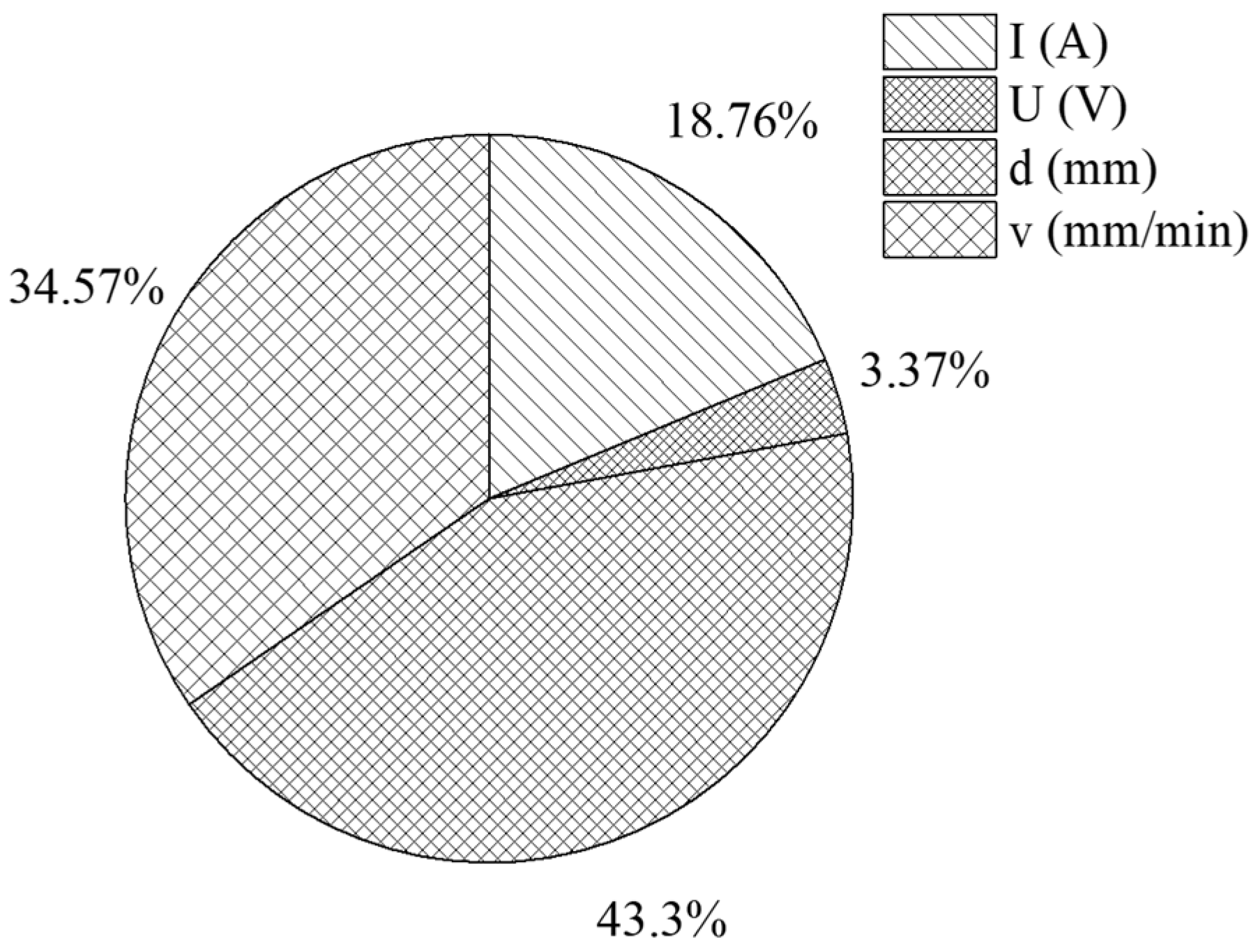

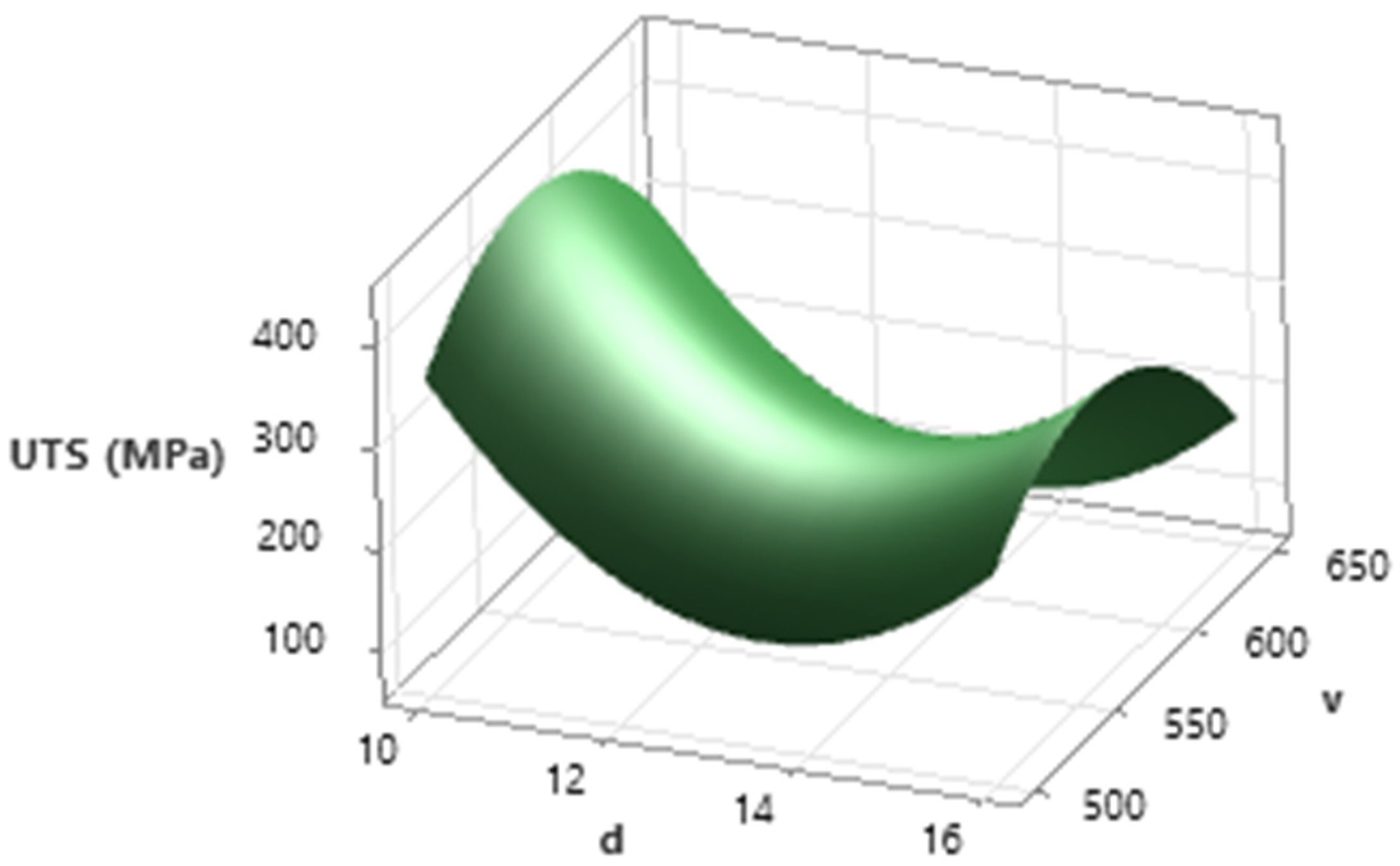

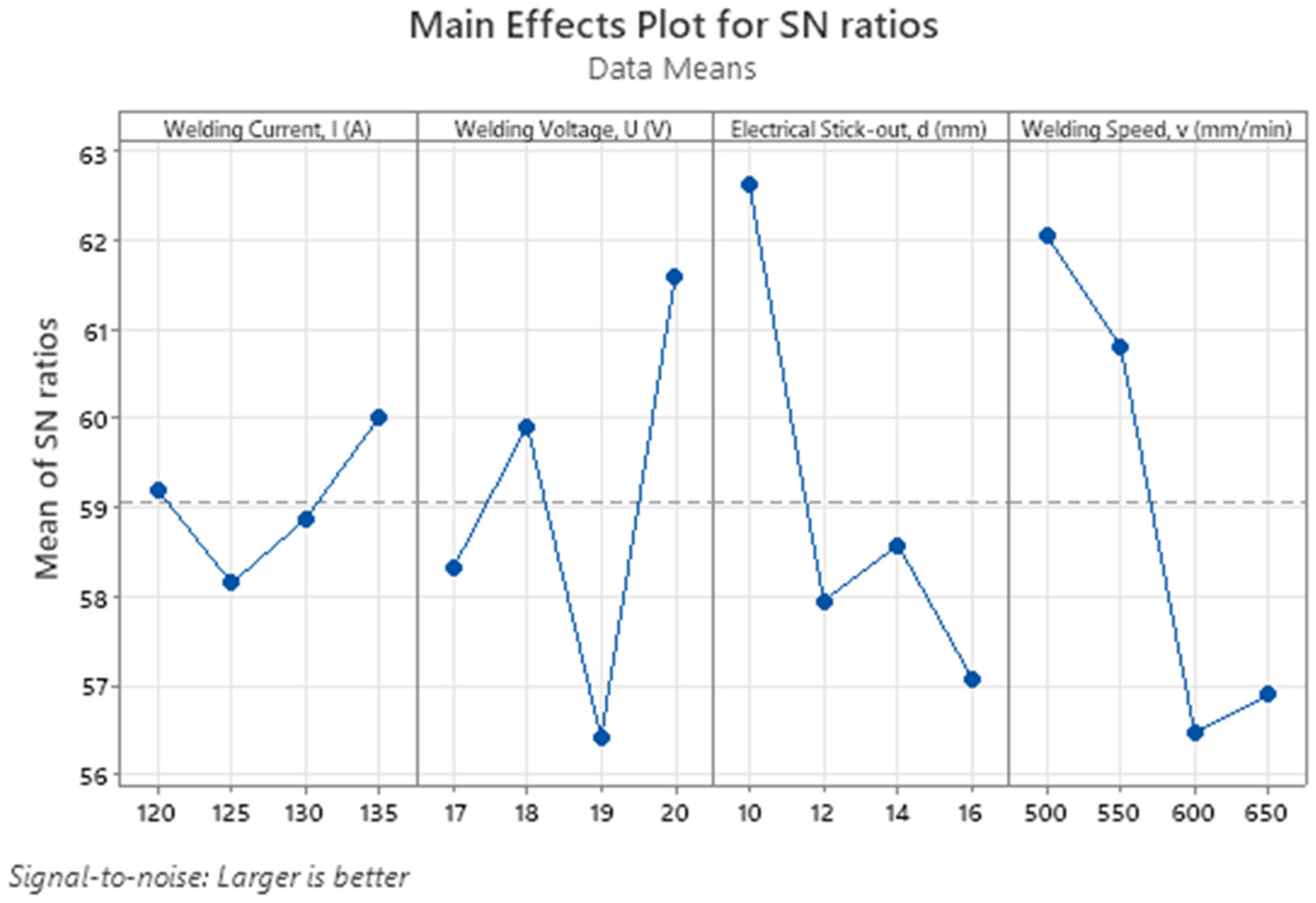

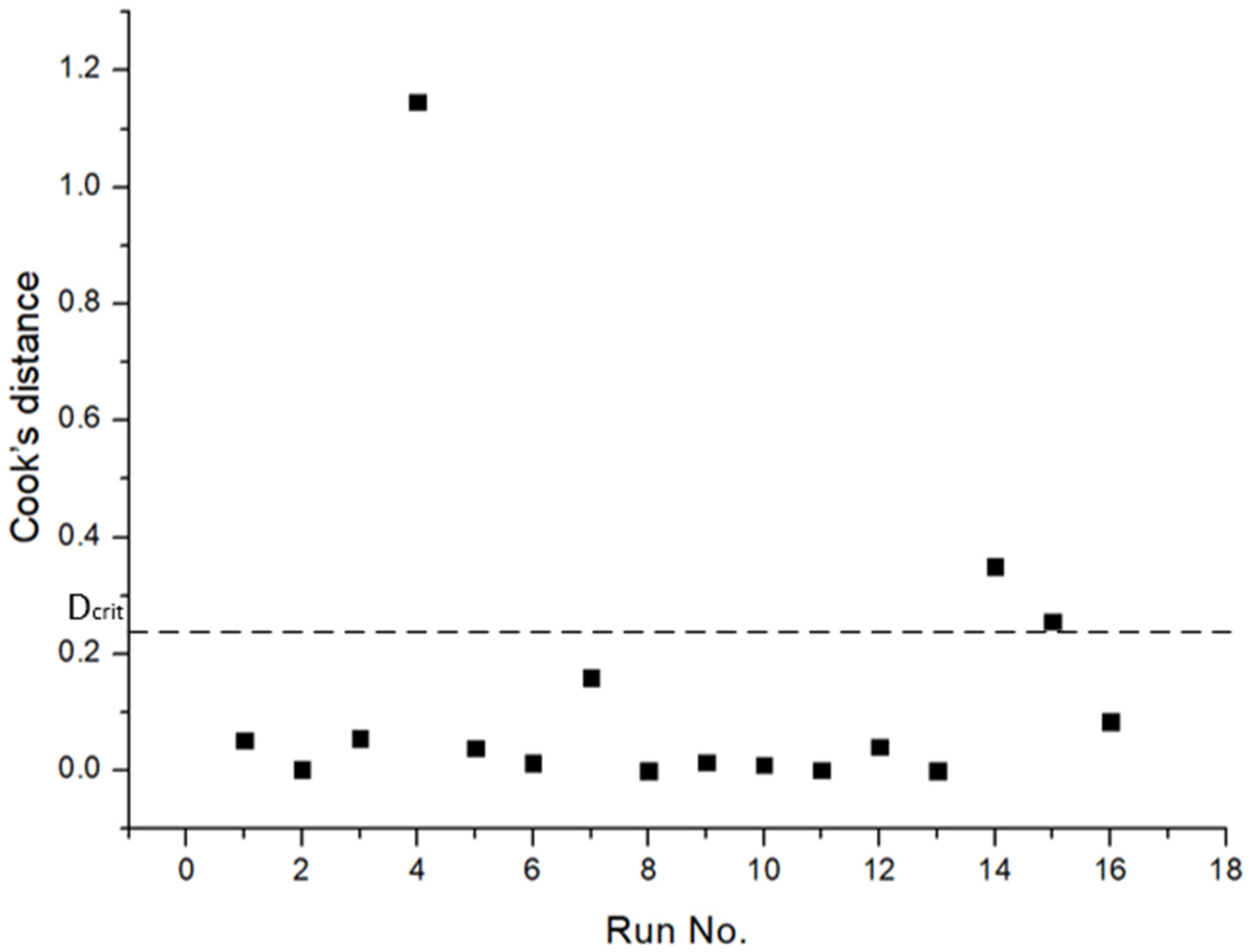

3.3. Taguchi Optimization of Tensile Strength

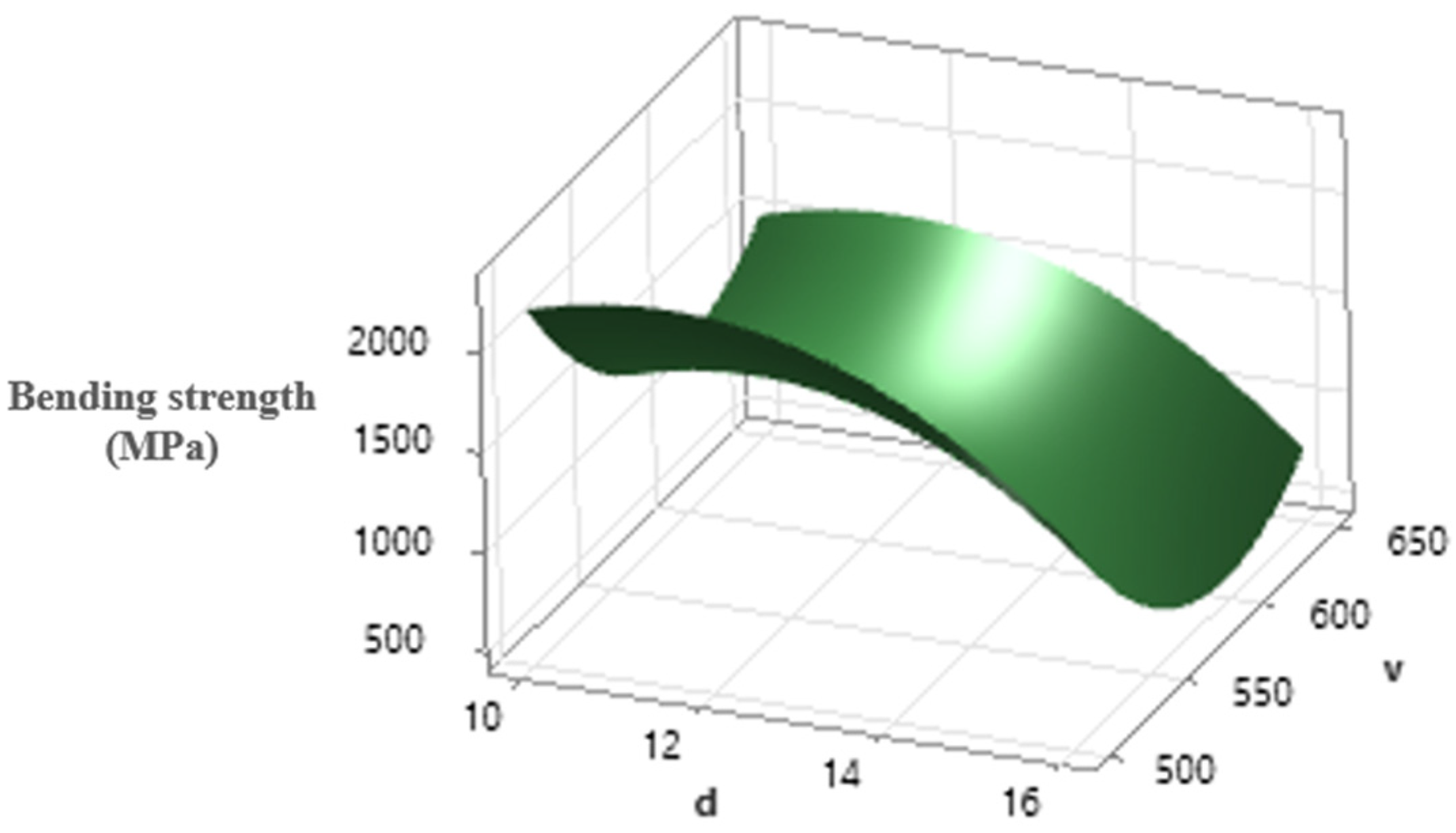

3.4. Bending Strength

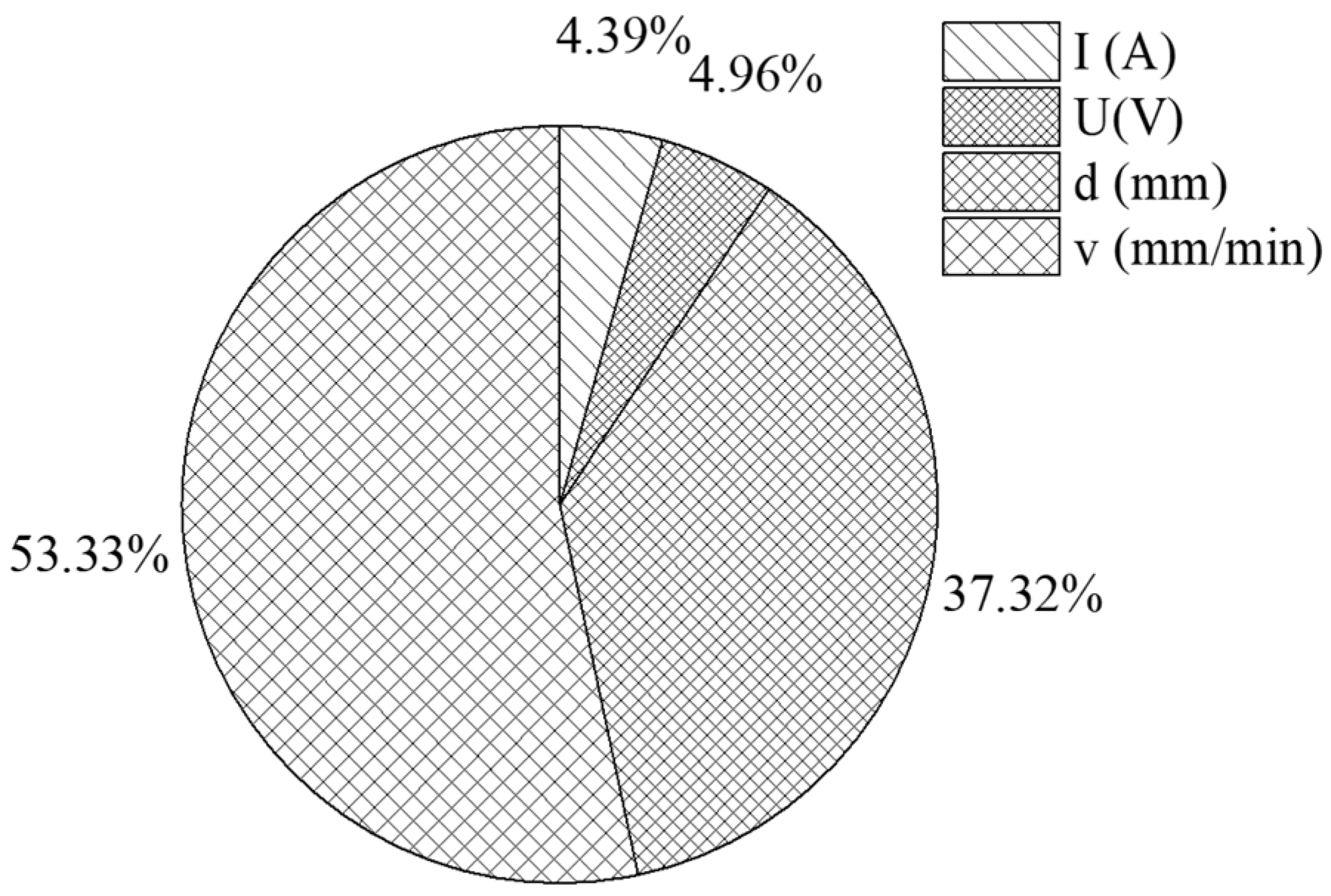

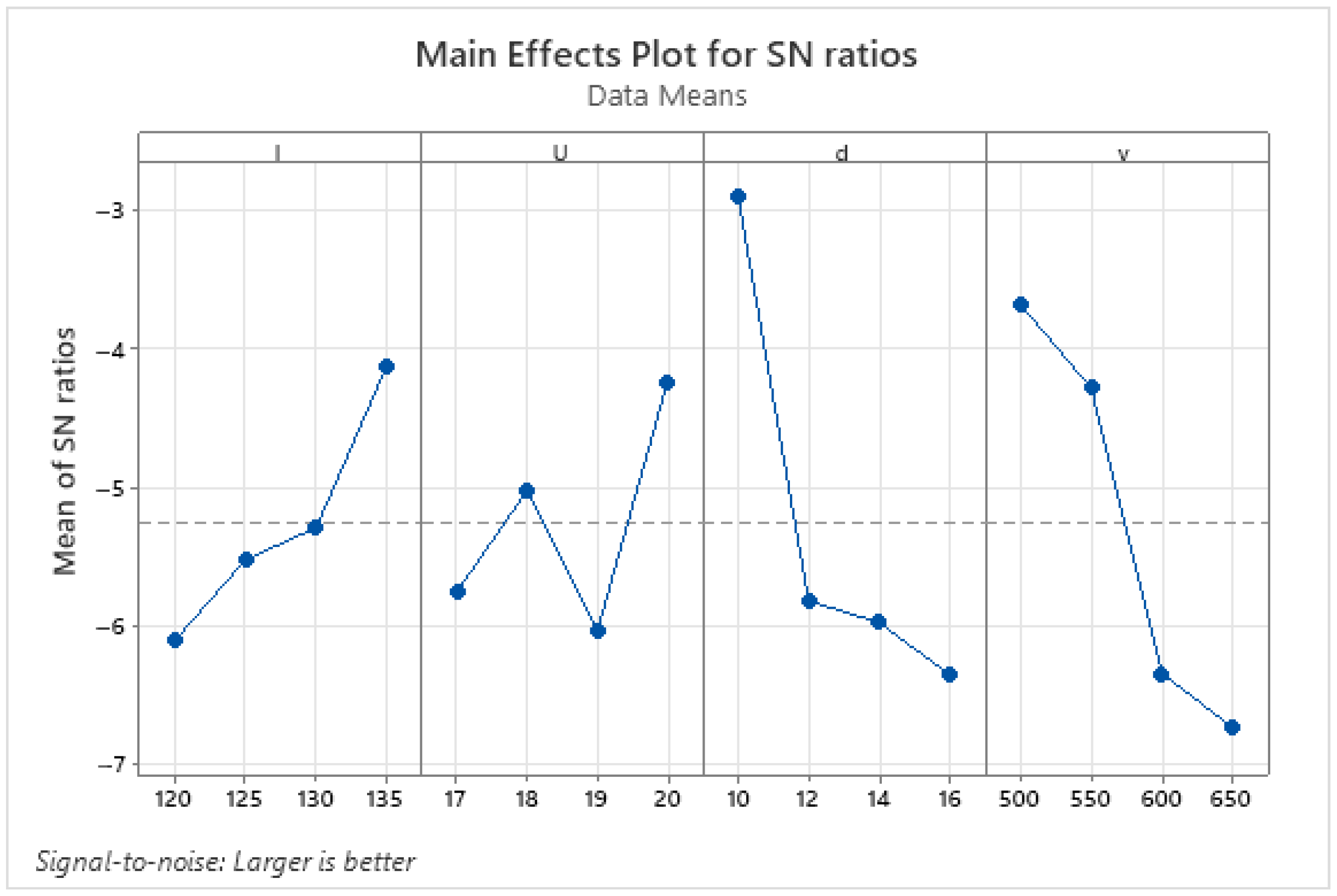

3.5. Taguchi Optimization of Bending Strength

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kleinbaum, S.; Jiang, C.; Logan, S. Enabling sustainable transportation through joining of dissimilar lightweight materials. MRS Bull. 2019, 44, 608–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Gao, S.; Wu, C.; Kar, A.; Basak, S. Towards Sustainability: Critical Insights into Solid-State Joining Processes for Developing Lightweight Hybrid Structures. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Technol. 2025, 13, 89–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kah, P.; Shrestha, M.; Martikainen, J. Trends in Joining Dissimilar Metals by Welding. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 440, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, A. Dissimilar metal welding using Shielded metal arc welding: A Review. Technol. Rep. Kansai Univ. 2020, 62, 1935–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Martinsen, K.; Hu, S.J.; Carlson, B.E. Joining of dissimilar materials. CIRP Ann. 2015, 64, 679–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-T.; Kil, S.-C. Research Trend of Dissimilar Metal Welding Technology. In Computer Applications for Modeling, Simulation, and Automobile; Kim, T., Ramos, C., Abawajy, J., Kang, B.-H., Ślęzak, D., Adeli, H., Eds.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 341, pp. 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taban, E.; Deleu, E.; Dhooge, A.; Kaluc, E. Laser welding of modified 12% Cr stainless steel: Strength, fatigue, toughness, microstructure and corrosion properties. Mater. Des. 2009, 30, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspar, J.; Zimmermann, M.; Ostwaldt, A.; Goebel, G.; Standfuß, J.; Brenner, B. Challenges in Joining Aluminium with Copper for Applications in Electro Mobility. Mater. Sci. Forum 2014, 783–786, 1747–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atabaki, M.M.; Nikodinovski, M.; Chenier, P.; Ma, J.; Harooni, M.; Kovacevic, R. Welding of Aluminum Alloys to Steels: An Overview. J. Manuf. Sci. Prod. 2014, 14, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskutis, S.; Baskutiene, J.; Bendikiene, R.; Ciuplys, A.; Dutkus, K. Comparative Research of Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Stainless and Structural Steel Dissimilar Welds. Materials 2021, 14, 6180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, G.M.; Rao, K.S. Microstructure and mechanical properties of similar and dissimilar stainless steel electron beam and friction welds. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2009, 45, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lu, M.; Zhang, L.; Chang, W.; Xu, L.; Hu, L. Effect of welding process on the microstructure and properties of dissimilar weld joints between low alloy steel and duplex stainless steel. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2012, 19, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abioye, T.E.; Ariwoola, O.E.; Ogedengbe, T.I.; Farayibi, P.K.; Gbadeyan, O.O. Effects of Welding Speed on the Microstructure and Corrosion Behavior of Dissimilar Gas Metal Arc Weld Joints of AISI 304 Stainless Steel and Low Carbon Steel. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 17, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaati, M.; Beidokhti, B. Characterization of AISI 304/AISI 409 stainless steel joints using different filler materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 147, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahador, A.; Hamzah, E.; Mamat, M.F. Effect of filler metals on the mechanical properties of dissimilar welding of stainless steel 316L and carbon steel A516 GR 70. J. Teknol. 2015, 75, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, R.; Tümer, M. Microstructural studies and impact toughness of dissimilar weldments between AISI 316 L and AH36 steels by FCAW. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 67, 1433–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmas, M.; Koçar, O.; Anaç, N. Study of the Microstructure and Mechanical Property Relationships of Gas Metal Arc Welded Dissimilar Protection 600T, DP450 and S275JR Steel Joints. Crystals 2024, 14, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelamasetti, B.; Sandeep, M.; Narella, S.S.; Tiruchanur, V.V.; Sonar, T.; Prakash, C.; Shelare, S.; Mubarak, N.M.; Kumar, S. Optimization of TIG welding process parameters using Taguchi technique for the joining of dissimilar metals of AA5083 and AA7075. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbonna, O.S.; Akinlabi, S.A.; Madushele, N.; Fatoba, O.S.; Akinlabi, E.T. Grey-based taguchi method for multi-weld quality optimization of gas metal arc dissimilar joining of mild steel and 316 stainless steel. Results Eng. 2023, 17, 100963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Hoang, V.H.; Thien, T.N.; Yen, D.T.K.; Minh, T.H.; Tuan, L.M.; Nguyen, A.T.; Nghia, H.T.; Anh, P.Q.; et al. Influence of Post-Heat Treatment on the Tensile Strength and Microstructure of Metal Inert Gas Dissimilar Welded Joints. Crystals 2025, 15, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Huong, H.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, V.-T.; Nguyen, V.T.T. Material Strength Optimization of Dissimilar MIG Welding between Carbon and Stainless Steels. Metals 2024, 14, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thejasree, P.; Natarajan, M.; Khan, M.A.; Vempati, S.; Yelamasetti, B.; Dasore, A. Application of a hybrid Taguchi grey approach for determining the optimal parameters on laser beam welding of dissimilar metals. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. (IJIDeM) 2025, 19, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, J.M.; Turan, F.M. Optimising MIG Welding Parameters for Enhanced Material Properties and Weld Quality: An Experimental Approach. In Symposium on Intelligent Manufacturing and Mechatronics; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E8/E8M-13; Standard Test Methods for Tension Testing of Metallic Materials. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013.

- ASTM E290; Standard Test Methods for Bend Testing of Material for Ductility. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM A276/A276M; Standard Specification for Stainless Steel Bars and Shapes. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- JIS G 4051; Carbon Steels for Machine Structural Use. JSA: Tokyo, Japan, 2023.

- Sahin, A.Z.; Ayar, T.; Yilbasi, B.S. Laser Welding of Dissimilar Metals and Efficiency Analysis. Lasers Eng. (Old City Publ.) 2009, 19, 139. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, X.L.; Wei, R.; Wu, K.M. Effect of acicular ferrite formation on grain refinement in the coarse-grained region of the heat-affected zone. Mater. Charact. 2010, 61, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-García, V.; Reyes-Calderón, F.; Frasco-García, O.D.; Alcantar-Modragón, N. Mechanical behavior of austenitic stainless-steel welds with variable content of δ-ferrite in the heat-affected zone. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 140, 106618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, K.-L. An overview of Taguchi method and newly developed statistical methods for robust design. IIE Trans. 1992, 24, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- e Silva, R.H.G.; dos Santos Paes, L.E.; Barbosa, R.C.; Sartori, F.; Schwedersky, M.B. Assessing the effects of solid wire electrode extension (stick out) increase in MIG/MAG welding. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2018, 40, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhan, X.; Zhou, X.; Liu, T.; Kang, Y. Effect of heat input on macro morphology and porosity of laser-MIG hybrid welded joint for 5A06 aluminum alloy. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 115, 4035–4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Steel Grade | C | Si | Mn | P | S | Cr | Ni | Cu | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUS201 [26] | ≤0.15 | ≤1.0 | 5.5–7.5 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.03 | 16–18 | 3.5–5.5 | – | balance |

| S20C [27] | 0.18–0.23 | 0.15–0.35 | 0.3–0.6 | ≤0.03 | ≤0.035 | ≤0.2 | ≤0.2 | 0.3 | balance |

| Welding Parameters | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (A) | 120 | 125 | 130 | 135 |

| U (V) | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| d (mm) | 10 | 12 | 14 | 16 |

| v (mm/min) | 500 | 550 | 600 | 650 |

| Welding Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Argon flow rate | 12 L/min |

| Travel angle | 0° |

| Working angle | 90° |

| No. | I (A) | U (V) | d (mm) | v (mm/min) | UTS (MPa) | UTS Deviation (%) | Elongation (%) | Elongation Deviation (%) | Yield Strength (MPa) | Yield Strength Deviation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 120 | 17 | 10 | 500 | 397.77 | 12.6 | 37.23 | 37.23 | 300.63 | 13.0 |

| 2 | 120 | 18 | 12 | 550 | 370.21 | 11.5 | 37.32 | 37.32 | 286.11 | 10.9 |

| 3 | 120 | 19 | 14 | 600 | 209.10 | 24.2 | 6.33 | 6.33 | 178.8 | 15.6 |

| 4 | 120 | 20 | 16 | 650 | 332.68 | 15.1 | 10.25 | 10.25 | 216.61 | 26.3 |

| 5 | 125 | 17 | 12 | 600 | 363.96 | 5.8 | 18.37 | 18.37 | 302.24 | 3.2 |

| 6 | 125 | 18 | 10 | 650 | 384.27 | 6.3 | 33.37 | 33.37 | 292.59 | 2.0 |

| 7 | 125 | 19 | 16 | 500 | 391.49 | 5.6 | 30.71 | 30.71 | 321.64 | 8.6 |

| 8 | 125 | 20 | 14 | 550 | 393.45 | 19.6 | 19.57 | 19.57 | 291.10 | 20.7 |

| 9 | 130 | 17 | 14 | 650 | 305.38 | 2.5 | 13.95 | 13.95 | 253.71 | 12.7 |

| 10 | 130 | 18 | 16 | 600 | 317.87 | 10.5 | 7.66 | 7.66 | 252.96 | 4.3 |

| 11 | 130 | 19 | 10 | 550 | 450.96 | 2.3 | 38.83 | 38.83 | 363.41 | 6.3 |

| 12 | 130 | 20 | 12 | 500 | 385.64 | 2.9 | 26.31 | 26.31 | 272.11 | 7.6 |

| 13 | 135 | 17 | 16 | 550 | 383.10 | 1.5 | 25.90 | 25.90 | 261.18 | 18.6 |

| 14 | 135 | 18 | 14 | 500 | 374.27 | 2.7 | 30.64 | 30.64 | 262.72 | 15.4 |

| 15 | 135 | 19 | 12 | 650 | 336.68 | 15.7 | 18.09 | 18.09 | 272.62 | 22.1 |

| 16 | 135 | 20 | 10 | 600 | 444.65 | 5.1 | 36.95 | 36.95 | 365.16 | 4.1 |

| No. | Welding Efficiency | Elongation (%) | DOP (mm) | Pass/Fail |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 93.6 | 37.23 | 0.84 | Failed |

| 2 | 87.1 | 37.32 | 0.90 | Failed |

| 3 | 49.2 | 6.33 | 0.35 | Failed |

| 4 | 78.3 | 10.25 | 1.32 | Passed |

| 5 | 85.6 | 18.37 | 0.56 | Failed |

| 6 | 90.4 | 33.37 | 1.53 | Passed |

| 7 | 92.1 | 30.71 | 1.20 | Passed |

| 8 | 92.6 | 19.57 | 1.99 | Passed |

| 9 | 71.9 | 13.95 | 1.29 | Passed |

| 10 | 74.8 | 7.66 | 0.83 | Failed |

| 11 | 106.1 | 38.83 | 3.21 | Passed |

| 12 | 90.7 | 26.31 | 2.24 | Passed |

| 13 | 90.1 | 25.90 | 1.42 | Passed |

| 14 | 88.1 | 30.64 | 1.26 | Passed |

| 15 | 79.2 | 18.09 | 1.28 | Passed |

| 16 | 104.6 | 36.95 | 2.14 | Passed |

| Level | I (A) | U (V) | d (mm) | v (mm/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 327.4 | 362.6 | 419.4 | 387.3 |

| 2 | 383.3 | 361.7 | 364.1 | 399.4 |

| 3 | 365.0 | 347.1 | 320.5 | 333.9 |

| 4 | 384.7 | 389.1 | 356.3 | 339.8 |

| Delta of factor | 57.2 | 42.0 | 98.9 | 65.5 |

| Ranking of the factor | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| Source | DF | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (A) | 1 | 4704.4 | 4704.4 | 2.12 | 0.173 |

| U (V) | 1 | 846.5 | 846.5 | 0.38 | 0.549 |

| Stick-out (mm) | 1 | 10,8528 | 10852.8 | 4.89 | 0.049 |

| Speed (mm/min) | 1 | 8666 | 8666 | 3.9 | 0.074 |

| Error | 11 | 24,4125 | 2219.3 | ||

| Total | 15 | 49,4822 | |||

| S = 47.1097; R-sq: 50.66%; R-sq (adj): 32.72% | |||||

| No. | I (A) | U (V) | d (mm) | v (mm/min) | Bending Strength (MPa) | Bending Strength Deviation (%) | GRG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 120 | 17 | 10 | 500 | 1510.42 | 13.9 | 0.6940 |

| 2 | 120 | 18 | 12 | 550 | 1112.69 | 5.5 | 0.5479 |

| 3 | 120 | 19 | 14 | 600 | 440.33 | 21.0 | 0.3342 |

| 4 | 120 | 20 | 16 | 650 | 930.23 | 13.1 | 0.4722 |

| 5 | 125 | 17 | 12 | 600 | 596.54 | 15.5 | 0.4720 |

| 6 | 125 | 18 | 10 | 650 | 977.63 | 15.7 | 0.5485 |

| 7 | 125 | 19 | 16 | 500 | 687.76 | 10.7 | 0.5255 |

| 8 | 125 | 20 | 14 | 550 | 1058.23 | 12.5 | 0.5777 |

| 9 | 130 | 17 | 14 | 650 | 610.84 | 12.7 | 0.4095 |

| 10 | 130 | 18 | 16 | 600 | 484.80 | 18.8 | 0.4093 |

| 11 | 130 | 19 | 10 | 550 | 1471.60 | 17.7 | 0.8338 |

| 12 | 130 | 20 | 12 | 500 | 1357.96 | 10.8 | 0.6255 |

| 13 | 135 | 17 | 16 | 550 | 833.70 | 15.9 | 0.5271 |

| 14 | 135 | 18 | 14 | 500 | 1817.14 | 2.3 | 0.8060 |

| 15 | 135 | 19 | 12 | 650 | 429.42 | 15.2 | 0.4237 |

| 16 | 135 | 20 | 10 | 600 | 1542.48 | 8.4 | 0.8334 |

| Level | I (A) | U (V) | d (mm) | v (mm/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 998.4 | 887.9 | 1375.5 | 1343.3 |

| 2 | 830.0 | 1098.1 | 874.2 | 1119.1 |

| 3 | 981.3 | 757.3 | 981.6 | 766.0 |

| 4 | 1155.7 | 1222.2 | 734.1 | 737.0 |

| Delta of factor | 325.6 | 464.9 | 641.4 | 606.3 |

| Ranking of the factor | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Source | DF | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (A) | 1 | 77,640 | 77,640 | 0.73 | 0.411 |

| U (V) | 1 | 87,720 | 87,720 | 0.83 | 0.383 |

| d (mm) | 1 | 660,113 | 660,113 | 6.22 | 0.03 |

| v (mm/min) | 1 | 943,419 | 943,419 | 8.88 | 0.013 |

| Error | 11 | 1,168,035 | 106,185 | ||

| Total | 15 | 2,936,926 | |||

| S = 325.860; R-sq: 60.23%; R-sq (adj): 45.77% | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hoang, V.H.; Nguyen, T.T.; Ho, M.T.; Trung, P.T.M.; Sung, N.V.; Nguyen, V.-T.; Nguyen, V.T.T. Optimizing S20C Steel and SUS201 Steel Welding Using Stainless Steel Filler and MIG Method. Metals 2026, 16, 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010110

Hoang VH, Nguyen TT, Ho MT, Trung PTM, Sung NV, Nguyen V-T, Nguyen VTT. Optimizing S20C Steel and SUS201 Steel Welding Using Stainless Steel Filler and MIG Method. Metals. 2026; 16(1):110. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010110

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoang, Van Huong, Thanh Tan Nguyen, Minh Tri Ho, Pham Tran Minh Trung, Nguyen Van Sung, Van-Thuc Nguyen, and Van Thanh Tien Nguyen. 2026. "Optimizing S20C Steel and SUS201 Steel Welding Using Stainless Steel Filler and MIG Method" Metals 16, no. 1: 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010110

APA StyleHoang, V. H., Nguyen, T. T., Ho, M. T., Trung, P. T. M., Sung, N. V., Nguyen, V.-T., & Nguyen, V. T. T. (2026). Optimizing S20C Steel and SUS201 Steel Welding Using Stainless Steel Filler and MIG Method. Metals, 16(1), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010110