Abstract

The promise of lithium–oxygen batteries lie not merely in their record-breaking theoretical energy density, but in the challenge of making such energy truly reversible. Rising as the key obstacle is the lithium metal anode, whose remarkable capacity and low potential come at the cost of dendritic growth, unstable solid electrolyte interphases, and relentless reactions with oxygen species. These instabilities, once overshadowed by cathode-related limitations, now define the frontier of research as current densities and energy demands approach practical levels. This review highlights recent progress in two complementary directions for anode protection: physical approaches, such as artificial protective layers, solid or functional separators, and oxygen-blocking interlayers that isolate and stabilize the surface; and chemical strategies, including electrolyte and additive design that enable in situ formation of LiF- and Li3N-rich interfaces with high ionic conductivity and chemical robustness. Together, these approaches establish a unified framework for achieving dendrite-free and oxygen-resistant lithium interfaces. Mastering solid electrolyte interfacial stability rather than only cathode catalysis will ultimately determine whether lithium oxygen battery can evolve from laboratory prototypes to truly viable high-energy systems.

1. Introduction

Rechargeable lithium–oxygen batteries (LOBs, also known as lithium–air batteries) have attracted great interest due to their exceptionally high theoretical energy density (up to ~3500–3600 Wh/kg), far exceeding conventional lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) [1,2]. This unique performance stems from two key differences: the use of a lithium metal anode (LMAs, instead of a graphitic intercalation anode) and the use of oxygen from the air as the cathode reactant [3,4]. Lithium metal offers an ultrahigh specific capacity (~3860 mAh/g) and an extremely low electrochemical potential, making it indispensable for achieving the full energy potential of Li–O2 cells [5]. However, these very advantages come with serious challenges. Unlike the stable intercalation process in the anodes of LIBs, the LOB’s bare LMA operates via repeated dissolution and deposition of Li metal, which can lead to hostless Li plating/stripping and the notorious formation of lithium dendrites [6,7]. Dendritic Li growth not only consumes active lithium (forming “dead” Li and a high-surface-area mossy structure) but also poses a severe safety risk if filaments penetrate the separator and short-circuit the cell [1]. Furthermore, the Li metal experiences essentially infinite volume change during cycling, as fresh Li is plated and stripped with no host matrix to buffer these fluctuations [8,9]. These well-known Li metal issues, including dendrite growth, unstable solid electrolyte interphase (SEI), and large volume changes, have long impeded the practical deployment of lithium-metal batteries [3,10]. In the context of LOBs, they are compounded by additional factors arising from the cell’s unique chemistry [11].

One distinctive aspect of LOB cells is their open (semi-open) cell design: the cathode is typically porous carbon that allows O2 gas diffusion from the environment [12,13]. During discharge, O2 is reduced to form Li2O2 on the cathode; during charge, Li2O2 decomposes back to O2. Critically, dissolved oxygen species (O2 and its reactive intermediates such as superoxide O2−) can migrate through the liquid electrolyte and reach the LMA [14]. This oxygen crossover phenomenon has no parallel in traditional LIBs and has profound implications for anode stability. Direct contact between Li metal and O2 (or soluble O2−) triggers parasitic reactions forming oxidative byproducts like LiOH and Li2CO3 on the anode surface [11,15]. These by-products alter the composition and morphology of the SEI layer at the Li/electrolyte interface, often making it thicker, more resistive, and less uniform. In effect, the normally fragile SEI on lithium is continuously corrupted by crossover O2 and electrolyte degradation products, leading to accelerated capacity decay of the LMA [6,16,17]. On the other hand, interestingly, some studies suggest that the presence of O2 can modulate dendrite formation. For instance, dissolved O2 has been reported to partially suppress lithium dendrite growth under certain conditions by forming a Li2O/Li2CO3-rich passivation layer [3,18]. This has led to differing observations: some authors find that dissolved O2 reduces unwanted side reactions at the LMA by building a more robust SEI [19,20], whereas others report that O2 worsens anode stability due to continuous parasitic reactions [21]. Regardless of these nuances, the semi-open oxygen environment in Li–O2 cells makes the LMA’s situation more complex than in closed-cell systems [22]. The Li metal must withstand not only the usual dendritic plating/stripping and SEI cycling but also attack by oxygen species and moisture (if any leaks) from the cathode side. This unique challenge underscores that protecting the LMA is just as critical to Li–O2 battery success as catalyzing the O2 reactions on the cathode [11,23].

Historically, the research emphasis in LOBs has been skewed toward the cathode [24,25]. A large body of work focused on developing efficient cathode catalysts and optimized porous carbon structures to improve oxygen reduction/evolution reactions, aiming to lower overpotentials and increase discharge capacity. Significant achievements include cathodes that deliver exceptionally high specific capacities (e.g., tens of thousands of mAh per gram carbon) and improved cycle life through catalyst and electrode architecture innovations [26,27]. In recent years, growing attention has also been paid to electrolyte stability (for instance, employing redox mediators to assist O2 reactions or using additives to suppress side reactions) as well as exploring all-solid-state LOB cells to eliminate volatile organic electrolytes [28,29]. Solid-state or hybrid solid–liquid electrolytes can indeed prevent direct contact between O2 and the Li metal, thereby mitigating some of the crossover-induced anode degradation [30]. These strategies have improved stability to a degree; however, even in all-solid-state Li–O2 batteries (ASSLOBs), the LMA remains a major bottleneck [29]. Issues of Li dendrite formation and high interfacial resistance persist in solid-state cells, often limiting the cycle life and rate capability [31]. Thus, whether in liquid-electrolyte LOB systems or emerging solid-state designs, the fundamental challenges posed by the LMA continue to restrict performance. For true long-term commercialization of LOB technology, it is increasingly recognized that anode-focused solutions must accompany cathode advancements [5,11,32]. In other words, stabilizing the LMAs by preventing dendritic growth, curbing side reactions, and maintaining a stable SEI is essential to unlock LOBs’ full potential.

Another important consideration is the disparity in operating current densities between typical LOB experiments and conventional LIBs. LOB cells are often tested under very low absolute current loads (sometimes reported in terms of mA per gram of cathode catalyst). For example, a common discharge condition might be ~0.1 mA/cm2 (which could correspond to ~100–500 mA per gram of carbon catalyst depending on loading) [33]. At such low rates, cells can attain high capacities (on the order of 5–15 mAh/cm2) as the formation of Li2O2 is allowed to proceed relatively unimpeded [34,35]. However, 0.1 mA/cm2 is orders of magnitude lower than the current densities at which LIBs typically operate; a standard LIB can easily sustain 1–2 mA/cm2 (roughly a 1C rate for a ~2 mAh/cm2 electrode) and even higher for power-oriented cells [36,37]. In fact, practical applications of LOBs will demand much higher current outputs than 0.1 mA/cm2; a recent analysis pointed out that delivering ~1000 W at ~2.5 V would require on the order of 1 mA/cm2 across the cell, which is ten times the current density used in many lab tests [25]. Pushing the LOB cell to such higher current densities is problematic, not only because of cathode polarization but also because of the LMA’s behavior. It is well-known from lithium metal battery studies that higher current density accelerates dendrite growth and aggravates non-uniform Li deposition, due to enhanced concentration polarization and kinetic roughening of the metal surface [10,38]. Under faster plating/stripping, lithium tends to deposit in a more uneven, filamentary manner, consuming electrolyte and forming “mossy” Li deposits and dendritic protrusions [1,10,36]. Thus far, many LOB studies have not reported severe dendrite-induced failures, likely because the current densities used were relatively low, and the cells often have limited cycle numbers [34]. We suspect that the dendrite problem has been masked under these gentle conditions. As the field moves toward higher-power and long-cycle LOB prototypes, the dormant issue of lithium dendrites will become unmistakably prominent [7]. In other words, even if all cathode challenges were solved, an unprotected LMA running at practical currents would quickly form dendrites, leading to short-circuits or rapid capacity fade. It is therefore imperative to address LMA protection head-on in the context of LOBs, especially for high-rate and extended cycling operation.

In recent years, a broad range of strategies have been proposed to stabilize LMAs in LOBs, reflecting the multifaceted nature of the challenges at this interface [6,39]. Physical approaches, such as artificial SEI coatings, mechanically robust interlayers, and oxygen-blocking membranes or solid-state separators have focused on constructing protective barriers to isolate the lithium surface from reactive oxygen species (ROS) and discharge products [11]. These methods can effectively suppress dendrite initiation, reduce direct chemical attack, and improve short-term cycling stability. In parallel, chemistry-driven strategies have gained increasing attention, aiming to regulate the interfacial reactions that define SEI formation and evolution [12,40]. By tailoring electrolyte composition, lithium salt chemistry, and reactive additives, researchers have demonstrated the possibility of in situ forming SEIs enriched with stable inorganic species such as LiF, Li3N, or Li2CO3 [3,41]. These interphases offer enhanced ionic conductivity and chemical robustness while maintaining uniform lithium deposition during cycling. Rather than competing paradigms, these two directions represent complementary aspects of the same objective achieving a stable, dendrite-free, and oxygen-tolerant lithium surface. Physical protection provides immediate mechanical and chemical stability, while interfacial chemistry tuning enables adaptive and self-regulating behavior under electrochemical stress [36]. Together, they form the foundation for the next generation of anode engineering in LOB systems, emphasizing that long-term progress will depend on integrating both structural and chemical control within a unified design framework.

In this review, we provide a focused overview of the LMA in LOBs, with an emphasis on recent progress in interfacial protective strategies between LMA and separator and SEI engineering approaches aimed at dendrite suppression and interfacial stabilization [Figure 1]. We first discuss the fundamental challenges facing the LMAs in the LOB environment, as outlined above, then systematically examine various protective strategies that have been reported, including artificial protective layers, electrolyte and separator modifications, and novel cell configurations designed to protect the LMAs. For each strategy, we summarize how it influences dendrite formation, Li plating/stripping behavior, and LMA longevity, drawing on evidence from the literature. Finally, we offer our perspective on the future directions and remaining challenges for achieving a dendrite-free, long-life LMAs in LOBs. By highlighting the anode side of the LOB equation, we aim to complement the extensive cathode-centered research and shine light on what is arguably the critical hurdle for translating LOB technology from laboratory promise to commercial reality.

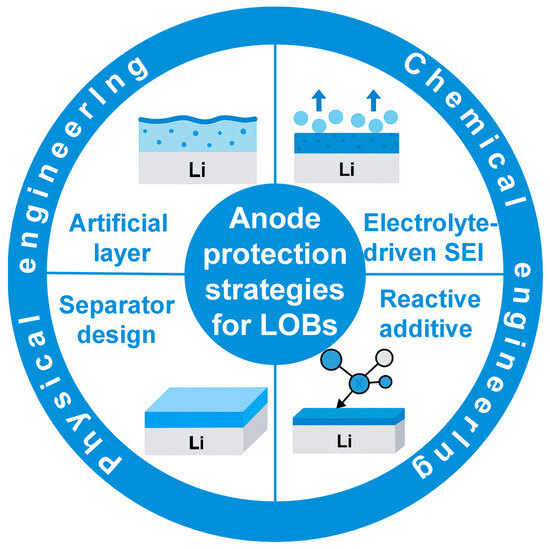

Figure 1.

Summary of anode protection strategies for LOBs, highlighting physical (artificial layer and separator design) and chemical (electrolyte-driven SEI and reactive additives) engineering to enhance lithium anode stability.

2. LMA Protection Strategies for High-Performance LOBs

2.1. Artificial Protective Layers

Artificial protective layers (APLs) have emerged as one of the most effective and versatile strategies to stabilize LMAs in LOBs. In contrast to other strategies, this approach focuses on constructing interfacial APLs positioned between the LMA and the separator/electrolyte to mitigate dendritic growth, suppress parasitic reactions, and prevent oxygen crossover while maintaining efficient Li+ transport [42,43,44]. The APL materials can be inorganic, polymeric, carbon-based, or hybrid in nature, each tailored to provide mechanical confinement, chemical stability, and ionic conductivity simultaneously [17,45]. A distinctive advantage of APLs is their dual functional mechanism. First, they act as chemical passivation layers, preventing direct contact between LMA and reactive oxygen intermediates such as O2−, LiO2, and Li2O2, which cause continuous side reactions and SEI degradation [22]. Second, they serve as ionically conductive regulators that promote homogeneous Li+ flux and uniform plating/stripping behavior by the presence of the APLs, effectively eliminating localized current concentrations that trigger dendrite nucleation [46]. The result is a more stable and reversible Li interface with improved Coulombic efficiency (CE) and prolonged cycle life. Furthermore, recent advances have focused on developing APLs with ion-selective or molecular-sieving capabilities, which can further enhance interfacial selectivity and suppress shuttle-induced degradation at the Li surface.

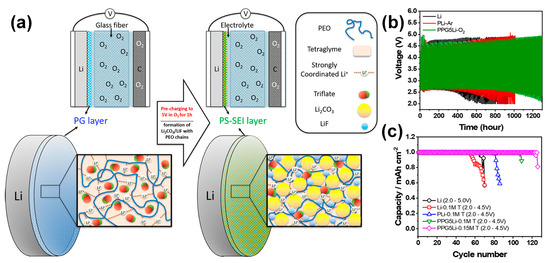

At the fundamental APL design level for LOBs, simple polymeric coatings were primarily explored to mitigate interfacial instability of LMAs. For example, Amici et al. introduced chitosan-derived biorenewable membranes that moderately improved Li corrosion resistance and extended the cycling life compared with bare Li anodes, owing to the antioxidant and radical-scavenging nature of chitosan [16]. Similarly, Poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene (PVDF-HFP)-based polymer coatings have been reported to form elastic and ionically conductive interphases that suppress parasitic reactions and promote smoother Li deposition during cycling [47]. Despite these promising effects, such single-component polymeric APLs generally exhibit limited mechanical robustness and insufficient resistance to oxygen-induced degradation. Consequently, recent studies have moved toward more sophisticated APL architectures that integrate inorganic, carbonaceous, and polymeric components, enabling synergistic enhancement in chemical stability, ionic conductivity, and interfacial compatibility. These hybrid systems have shown more effective and durable protection than simple polymer coatings. Following the development of simple polymer-based APLs, Lim et al. proposed a more advanced in situ approach that utilizes an electrochemically induced protective layer formation process on the Li surface (Figure 2a) [4]. In this work, a thin poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO)-based gel-like polymer coating was applied onto the LMA, followed by an electrochemical precharging step to 5.0 V under an oxygen atmosphere using a 1 M lithium trifluoromethanesulfonate/tetraglyme electrolyte. This precharging induced controlled decomposition of the electrolyte and polymer, leading to the in situ formation of a polymer-supported solid electrolyte interphase (PS-SEI) rich in inorganic components such as Li2CO3 and LiF that were uniformly embedded within the flexible PEO matrix. The resulting PS-SEI exhibited a submicrometer-scale continuous morphology with excellent interfacial conformity, effectively suppressing electrolyte consumption and Li corrosion even under O2-rich conditions. The beneficial effect of this in situ-formed PS-SEI was verified through LOB cell tests (Figure 2b), where the cell with the PS-SEI-protected anode showed a notably reduced overpotential and smoother charge–discharge profiles compared with the pristine Li cell. In extended cycling experiments (Figure 2c), the PS-SEI anode enabled stable operation for over 130 cycles with low polarization, nearly twice that of the control cell. This improvement was attributed to the synergistic combination of the polymer matrix’s mechanical flexibility and the inorganic component’s chemical robustness, which collectively mitigated parasitic reactions, enhanced interfacial ion transport, and maintained the structural integrity of the LMA during repeated cycling.

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic illustration of formation of PS−SEI layer on LMA surface by electrochemical precharging to 5.0 V under O2 atmosphere. (b) Voltage profiles of LOB cells with pristine LMA (Li), PPG5Li−O2 (after precharging treatment with PG coating), and PLi−Ar (after precharging treatment without PG coating) at 0.2 mA/cm2 for 1.0 mAh/cm2. (c) Cycle life of LOB cells with various anodes at 0.2 mA/cm2 for 1.0 mAh/cm2. (Reproduced with permission from Ref. [4], copyright 2021, American Chemical Society).

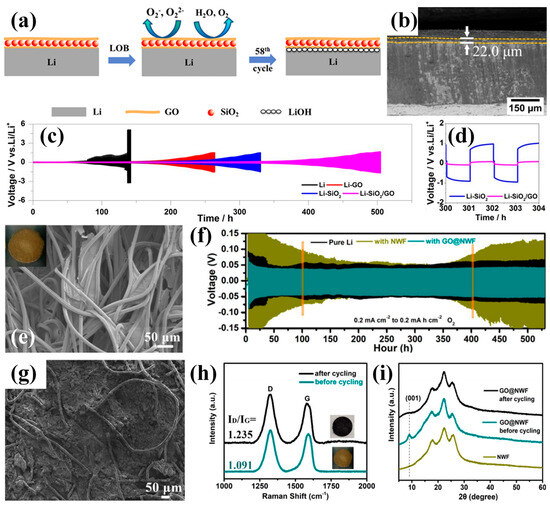

In parallel with such in situ-formed polymer-supported layers, a variety of ex situ engineered APLs have also been developed by incorporating inorganic or carbonaceous fillers into polymeric or composite matrices. These hybrid structures are designed to provide enhanced mechanical rigidity, chemical durability, and lithiophilicity, thereby suppressing dendritic Li growth and parasitic interfacial reactions under oxygen-rich conditions. A representative example of inorganic–carbon hybrid APLs was reported by Luo et al., who proposed a facile surface preservation approach using a hybrid SiO2/graphene oxide (GO) APL positioned at the LMA surface [31]. As illustrated in Figure 3a,b, the SiO2/GO hybrid APL (~22 μm) possesses a laminated architecture in which SiO2 nanoparticles are intercalated between GO sheets. This configuration effectively prevents the excessive stacking of GO layers and forms interconnected nano-/mesopores that facilitate Li+ transport through the coating. Such a laminated structure acts as an interfacial APL that blocks the penetration of O2 and H2O while maintaining efficient ionic conduction across the interface, thereby stabilizing the Li surface against corrosion and dendrite initiation during cycling. The electrochemical stability of the SiO2/GO APL was further evaluated using Li/Li symmetric cells under both sealed and O2-containing environments. In an Ar-filled configuration, both the SiO2-coated and SiO2/GO-coated LMAs exhibited much longer cycling stability compared with pure Li and GO-coated electrodes. Between the two, the cell with the SiO2-only coating delivered the most stable voltage profile, indicating that the rigid oxide layer effectively suppresses dendritic growth and parasitic reactions during Li plating/stripping in an oxygen-free environment. However, when tested under an O2 atmosphere (mimicking practical LOB conditions), the difference between these coatings became more pronounced (Figure 3c,d). Both SiO2− and SiO2/GO-coated electrodes showed lower polarization and more stable voltage profiles than bare Li and GO-coated ones. After approximately 300 h of cycling, the Li|Li symmetric cell with the SiO2-coated anode exhibited an increase in overpotential exceeding 2.0 V, whereas the SiO2/GO-coated cell showed a smaller rise of about 140 mV. These results indicate that both coatings can enhance the interfacial stability of LMAs, while the laminated SiO2/GO hybrid structure provides comparatively better resistance to oxygen-induced degradation. The combination of SiO2 nanoparticles and GO nanosheets maintains Li+ transport across the interface and mitigates side reactions under oxygen-rich conditions. As expected, the enhanced interfacial stability of the SiO2/GO-coated LMA translated into improved performance in Li symmetric cell tests. As expected, the enhanced interfacial stability of the SiO2/GO-coated LMA translated into significantly improved LOB performance. The cell employing the hybrid-protected anode exhibited a several-fold increase in cycle life and noticeably better rate capability compared with those using pristine Li, SiO2−, or GO-coated electrodes. Post-cycling analyses confirmed that the SiO2/GO APL effectively reduced Li consumption and LiOH accumulation, thereby mitigating corrosion and preserving the metallic Li morphology during prolonged operation.

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic illustration of the working mechanism of the SiO2/GO hybrid APC on the LMA in LOBs. (b) Cross−sectional SEM image of Li−SiO2/GO anode. (c) Li stripping/plating curves in Li|Li symmetric cells with pristine Li, Li−GO, Li−SiO2 and Li−SiO2/GO at 0.1 mA/cm2 in O2 atmosphere. (d) The selected voltage profiles in the range from 300 to 304 h (Reproduced from Ref. [31]). (e) SEM image of GO@NWF APL (inset: digital photo of GO@NWF). (f) Voltage profiles for Li|Li symmetric cells using pure Li, Li+NWF, and Li+GO@NWF with 0.2 mAh/cm2 at 0.2 mA/cm2 in O2 atmosphere. (g) SEM image of LMA under GO@NWF after 550 h cycling in Li|Li symmetric cell with 0.2 mAh/cm2 at 0.2 mA/cm2 in O2 atmosphere. (h) Raman spectra of GO@NWF before/after the first cycle in Li|Li symmetric cell. (i) XRD patterns of NWF, as well as GO@NWF before/after the first cycle in Li|Li symmetric cell. (Reproduced with permission from Ref. [48], copyright 2020, American Chemical Society).

In addition to inorganic–carbon hybrid APLs, a different approach emphasizing mechanical flexibility and conductive network formation has also been demonstrated. In a separate study, Guo et al. developed a flexible graphene oxide-modified nonwoven fabric (GO@NWF, Figure 3e) that served as a freestanding APL for LOBs [48]. The GO@NWF APL was inserted between the LMA and the separator, serving as an interfacial barrier that stabilized Li plating and stripping under O2 atmosphere. Symmetric Li|Li cells equipped with this membrane exhibited flatter voltage profiles and smaller hysteresis than those using bare Li or pristine NWF (Figure 3f). The GO@NWF-protected cell maintained a stable voltage hysteresis below 45 mV without short-circuiting for over 550 h, confirming its ability to enhance Li+ transport kinetics and suppress interfacial degradation in oxygen-rich conditions. Post-cycling SEM observations revealed that the GO@NWF-covered Li surface remained relatively smooth and compact with coralloid Li deposition (Figure 3g), confirming that the membrane effectively guided uniform Li growth and mitigated surface roughening during repeated cycling. The remarkable LMA stabilization achieved by the GO@NWF APL was attributed to an in situ reduction process of GO during the initial cycling, which transformed the insulating GO@NWF into a conductive rGO@NWF network through an electrochemical reaction between GO and Li (GO + 2H+ + 2e− → rGO + H2O, the electron exchange reaction between GO and Li) [49,50]. This transformation was verified by an increased ID/IG ratio in the Raman spectra (Figure 3h) and the disappearance of the (001) diffraction peak of GO in XRD patterns (Figure 3i), confirming the formation of rGO during the first Li plating/stripping cycle. The resulting thin rGO layer uniformly coated on the NWF fibers enhanced the electronic conductivity of the membrane and promoted even Li+ flux distribution at the anode interface, thereby suppressing dendrite growth, improving interfacial stability, and ultimately leading to markedly enhanced cycling performance of Li–O2 cells.

While these strategies demonstrated remarkable improvements in interfacial stability and dendrite suppression under O2 atmospheres, they primarily focused on regulating Li plating and stripping behaviors. However, in practical Li–O2 systems, additional degradation arises from the shuttle of soluble redox mediators (RMs, such as 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidinyloxyl (TEMPO) [51], lithium bromide [52], lithium iodide [53], and iron phthalocyanine) [54] between the cathode and the Li surface, which leads to severe parasitic reactions and rapid capacity fading [55,56], similar to the lithium polysulfide migration observed in Li–S batteries [57,58,59]. To this end, several studies have explored composite coatings incorporating carbonaceous or inorganic fillers, such as Super P and graphene–polydopamine composites [60,61], to suppress RM shuttling. Although these designs successfully reduced mediator crossover and improved cycling stability, their functionality was largely limited to chemical shielding, with insufficient consideration of Li deposition uniformity or dendrite suppression [62].

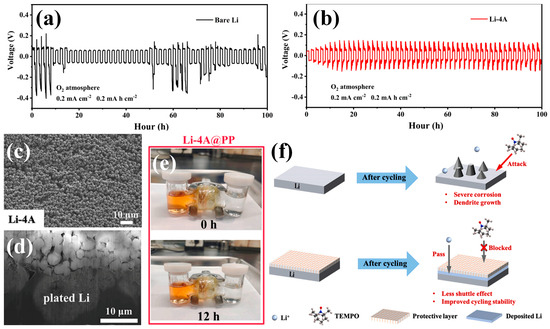

Beyond stabilizing Li plating/stripping, an advanced APL for LOBs must also mitigate parasitic reactions arising from the shuttle of RMs between the cathode and the LMA. Therefore, APLs in LOB systems are increasingly designed to serve not only as ionic regulators but also as molecular sieves that suppress the crossover of oxygen intermediates and soluble mediators [63]. Because their composition, ionic conductivity, and pore structure can be precisely tuned, APLs offer a flexible platform for simultaneously controlling Li+ transport and preventing RM migration [64]. Among the limited studies that concurrently addressed both Li dendrite growth and RM shuttling, Wu et al. developed a lithiated 4A zeolite (Li-4A)-based APL specifically engineered to exploit the molecular sieving ability of zeolites in Li–O2 batteries [65]. The Li-4A zeolite framework, with an aperture size of approximately 4 Å, selectively allows Li+ transport while excluding bulkier TEMPO molecules (~ 9 × 5 × 5 Å), thereby preventing their diffusion toward the anode. At the same time, the pre-lithiated structure provides continuous Li+ conduction pathways that facilitate uniform deposition and suppress dendrite formation. As shown in Figure 4a,b, the Li–4A-protected symmetric cell exhibited stable and symmetric voltage profiles for nearly 100 h under O2, whereas the bare Li cell short-circuited within 60 h, indicating the superior interfacial stability of the Li–4A layer during cycling. Furthermore, post-cycling SEM observations after five plating/stripping cycles (Figure 4c,d) revealed that the Li–4A-protected LMA retained a dense and uniform Li layer beneath the intact zeolite coating, demonstrating that the Li–4A framework promotes homogeneous Li deposition and effectively mitigates dendritic growth. On the other hand, as shown in Figure 4e, the diffusion test using TEMPO-containing electrolyte clearly demonstrated the molecular sieving ability of the Li–4A layer. While the orange-colored TEMPO rapidly permeated through the pristine separator within 12 h, no visible diffusion occurred across the Li–4A@PP membrane, indicating that the zeolite framework effectively blocked the migration of RM species. As illustrated in Figure 4f, the Li–4A-based APL allows selective Li+ transport while blocking bulky redox mediators such as TEMPO, thereby simultaneously suppressing dendrite growth, preventing corrosive mediator attack, and enhancing the overall cycling stability of LOBs.

Figure 4.

Voltage profiles of the symmetric Li|Li cells with (a) a bare LMA or (b) a LMA protected by Li−4A APL under O2 atmosphere. SEM images of LMAs with Li−4A APL after 5 cycles of the LOB cell; (c) top−view and (d) cross−sectional SEM image. (e) Photograph of visual TEMPO diffusion test with Li−4A separator for 12 h. (f) Schematic illustration of the protection mechanism for the Li−4A APL. (Reproduced from Ref. [65]).

2.2. Separator Design and Modification

Since the late 2010s, separator design and modification in LOBs have progressively evolved toward functional architectures capable of selectively regulating ionic and molecular transport to suppress RM shuttling across the electrode interface [66]. Various strategies have been reported, including conductive polymer coatings using PEDOT:PSS (poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) poly-styrene sulfonate) layers that immobilize charged mediators through electrostatic interaction [67,68], composite NPG (Nafion–PEO–graphene) membranes proposed by Chen et al. [69], where the O atoms in PEO, the sulfonic acid groups in Nafion, and the graphene skeleton formed a dense network barrier that provided single-ion conductivity and effectively suppressed LiI shuttling in LOBs, and inorganic frameworks like MOF-based separators that utilize molecular sieving and Lewis-acidic adsorption, and surface-engineered separators incorporating catalytic nanoparticles or hydrophobic ceramic fillers to mitigate mediator crossover [66,70]. While these studies have demonstrated significant progress in reducing mediator diffusion and improving cell reversibility, most of them primarily focused on chemical selectivity and transport regulation, with limited consideration of Li dendrite suppression at the anode. To date, only a few separator systems have been rationally designed to simultaneously address both RM shuttling and dendritic Li growth, highlighting the need for integrated design strategies that couple molecular sieving capability with mechanical and interfacial stabilization.

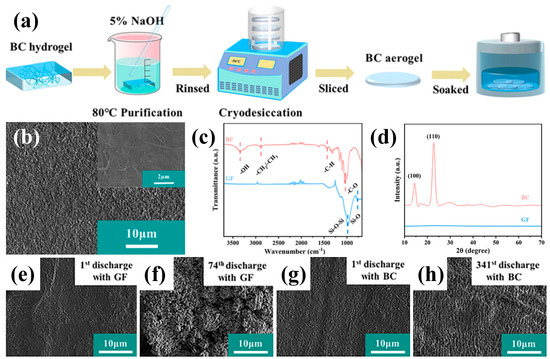

Building on these developments, Wu et al. proposed a single-ion-conductive bacterial cellulose (BC) membrane as a functional separator for LOBs [71]. As illustrated in Figure 5a, the membrane was fabricated by purifying BC hydrogels in a 5% NaOH solution at 80 °C to remove bacterial residues, followed by thorough rinsing and cryodesiccation to obtain a porous, freestanding aerogel structure. The resulting BC separator exhibited a densely entangled nanofibrous morphology with interconnected pores (Figure 5b), which endowed it with excellent mechanical strength, electrolyte wettability, and dimensional stability. The FT-IR spectra (Figure 5c) revealed abundant polar functional groups such as –OH, –CH2–, and –C–O– within the BC framework, which strengthen coordination with Li+ ions, thereby enhancing interfacial affinity toward the electrolyte and facilitating continuous Li+ transport through BC networks. In addition, the XRD patterns (Figure 5d) exhibited distinct peaks corresponding to the (100) and (110) planes, indicating high crystallinity that contributes to structural robustness and ensures stable Li+ conduction during long-term cycling. Surface analyses after long-term cycling (Figure 5e–h) revealed that the BC-protected LMA retained a dense and smooth morphology even after the 341st discharge, whereas the Li surface paired with the conventional glass-fiber (GF) separator became severely corroded and porous after only 74 cycles, confirming the superior interfacial stability and dendrite-suppressing capability of the BC membrane. Another representative study introduced a poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF)-based single-ion-conductive separator modified with an ionic liquid (denoted as MSP separator) to achieve selective Li+ transport and suppress I−/I3− shuttling in iodide-assisted LOBs [72]. The incorporation of anions-immobilized ionic liquid within the PVDF matrix endowed the MSP separator with a high Li+ transference number (≈0.81) and ionic conductivity (~10−3 S cm−1), leading to improved chemical and interfacial stability. The LMA paired with the MSP separator remained flat and compact even after the 210th discharge cycle, exhibiting significantly reduced Li consumption compared to the glass-fiber case, where the Li surface became rough and was gradually depleted with LiOH formation, confirming that the MSP separator effectively suppresses dendritic growth and protects the Li surface during prolonged cycling. The superior LMA stability enabled by the MSP separator was further evidenced by symmetric Li|Li cell tests, in which the cell maintained a stable and low-polarization voltage profile for over 700 h, whereas the one with the glass-fiber separator exhibited rapid voltage divergence, confirming the MSP separator’s remarkable capability to stabilize Li plating and stripping.

Figure 5.

(a) Manufacturing process and (b) SEM image of the BC membrane. (c) FT−IR and (d) XRD data of the BC and GFs. Surface SEM images of the LMA in the iodide-assisted LOB cells. ((e) 1st and (f) 60th discharges with GF; (g) 1st and (h) 341st discharges with BC) (Reproduced from Ref. [71]).

These physical protection strategies operate through distinct yet complementary mechanisms. Artificial layers modulate the interfacial electric field and homogenize Li+ flux, suppressing dendrite initiation, while functional separators provide molecular sieving and ion-selective transport to block oxygen and redox mediator crossover. Together, they maintain uniform Li deposition and minimize parasitic reactions under oxygen-rich conditions. The interplay between mechanical confinement and selective ion conduction ensures stable lithium plating/stripping and underpins the overall electrochemical stability of physically protected LMAs.

Despite their clear advantages, physical protection strategies also face several inherent limitations. Artificial coatings and separators may gradually lose integrity during long-term cycling due to mechanical stress, volume fluctuation of Li, and interfacial delamination. Moreover, dense or multi-component protective films can increase interfacial resistance, limiting Li+ transport under high current operation. The fabrication of uniform, defect-free coatings is also difficult to scale up, especially for large-area electrodes. While mechanical confinement and oxygen blocking improve short-term stability, these methods often lack self-healing capabilities, making them insufficient for prolonged operation at practical current densities. Future efforts should therefore focus on achieving a balance between structural robustness, ionic conductivity, and manufacturing feasibility.

Overall, these studies highlight that rational separator design, combining single-ion conductivity, molecular sieving functionality, and interfacial compatibility, offers an effective pathway to simultaneously suppress RM shuttling and stabilize Li anodes in LOBs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of physical protection strategies for LMAs in LOBs. The table highlights representative approaches such as artificial protective layers, solid or functional separators, and oxygen-blocking interlayers, comparing their protection mechanisms, and achieved electrochemical performance in LOB systems.

3. SEI/Interfacial Chemistry Engineering for LOBs

3.1. Electrolyte-Driven SEI Chemistry for Dendrite Suppression

In LOBs, the lithium metal anode is particularly vulnerable to degradation caused by dendritic lithium growth, parasitic reactions with reactive oxygen species, and structural disintegration at the electrode–electrolyte interface [73]. These issues are further intensified by the presence of singlet oxygen and soluble intermediates such as LiO2 and O2−, both of which can accelerate the breakdown of the interfacial layer. As a result, developing a chemically and mechanically SEI is essential for maintaining long-term battery stability [41]. Unlike externally applied coatings that passively block contact, SEIs formed in situ via electrolyte reaction can respond dynamically to the cycling environment, offering adaptive protection [55,74]. This makes electrolyte-driven SEI engineering a central strategy in the design of next-generation LOB systems.

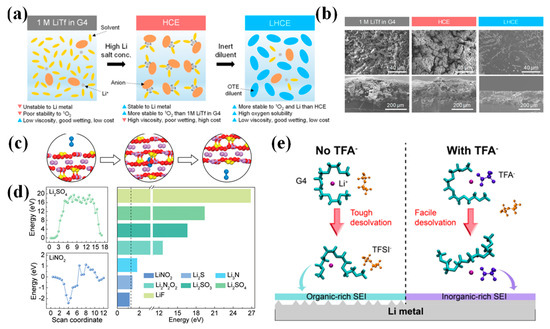

A fundamental lever in this approach is the tuning of lithium ion solvation structures. The local coordination environment around Li+ dictates which species are most likely to undergo decomposition and contribute to SEI formation. For instance, in the study by Kwak et al. [75], the authors explored how electrolyte concentration influences solvation behavior in glyme-based systems. They compared a conventional 1 M Lithium trifluoromethanesulfonate (LiTf) in tetraglyme (G4), a high-concentration electrolyte (2.8 M LiTf), and a localized high-concentration electrolyte (LHCE), which was made by adding specific1H,1H,5H-octafluoropentyl 1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethyl ether (OTE) to 0.84 M LiTFSI. In the conventional system, solvent molecules dominate the solvation shell, leading to ether-rich decomposition products and porous SEI layers. In contrast, the HCE system encourages more anion coordination, resulting in SEIs rich in LiF and other inorganic compounds. The LHCE formulation manages to retain this anion-dominant coordination while improving oxygen solubility and reducing viscosity. SEM images after ten cycles revealed that the LHCE produced smoother and more compact lithium deposits, while the conventional electrolyte led to mossy and dendritic growth. These results point to the SEI’s crucial role in maintaining uniform lithium deposition and preventing dendrite formation (Figure 6a,b).

Figure 6.

(a) Schematic illustration of solvation structures in conventional HCE and LHCE, highlighting the evolution toward anion-rich environments favorable for stable SEI formation. (b) SEM images of Li anodes after 10 cycles in LOB cells (Reproduced with permission from Ref. [75], copyright 2020, American Chemical Society). (c) DFT−based atomistic model illustrating O2 interactions. (d) Calculated migration energy barriers of O2 across various SEI compositions (Reproduced with permission from Ref. [76], copyright 2021, Royal Society of Chemistry). (e) Schematic representation of how LiTFA−modified solvation structures promote LiF−rich SEI formation (Reproduced with permission from Ref. [77], copyright 2023, Wiley−VCH).

The improved performance of the LHCE can be attributed to its unique micro-heterogeneous solvation environment. In this system, the OTE is chemically inert toward Li+, thereby preventing direct coordination and physically separating ion–solvent clusters into localized high-concentration domains. This configuration preserves the anion-dominated Li+ coordination characteristic of concentrated electrolytes, which favors the generation of stable inorganic SEI species such as LiF while simultaneously lowering bulk viscosity. Because the diluent phase remains low in polarity, oxygen dissolution and diffusion are maintained, allowing efficient gas transport through the electrolyte. Hence, the LHCE successfully reconciles uniform lithium deposition with efficient oxygen transport, two factors that are typically in conflict in conventional concentrated electrolytes.

The impact of SEI composition extends beyond physical morphology to chemical functionality, particularly in mitigating oxygen crossover. Lin et al. [76] addressed this aspect using DFT simulations. They selectively analyzed O2 migration through bulk crystal channels of various SEI components. Their results showed that LiNO3 permits relatively easy O2 transport, with an energy barrier of ~1.0 eV, while other species such as Li3N, LixNyOz, and Li2xSyOz exhibited much higher barriers ranging from 1.4 to 26.8 eV, effectively impeding O2 migration (Figure 6b,c). These findings indicate that SEIs composed of oxygen-impermeable species can serve as effective barriers against parasitic oxygen reactions [22]. In particular, SEIs engineered to position these impermeable components at the outer surface, such as those formed by electropolishing, are likely to provide significantly better protection than conventional SEIs, which often expose oxygen-permeable species like LiNO3 at the interface.

Huang et al. [77] further demonstrated how electrolyte additives can be used to manipulate solvation environments. The addition of lithium trifluoroacetate (LiTFA) significantly alters the solvation environment and the interfacial chemistry at the lithium metal anode. As illustrated in Figure 6e, introducing TFA− anions into the solvation sheath enhances anion coordination by weakening the interaction between Li+ and G4 solvent molecules. In the standard electrolyte, Li+ ions are primarily coordinated by G4 due to strong solvent chelation, which results in a high desolvation energy barrier (~58.2 kJ mol−1). This tight Li+–G4 interaction not only hinders Li+ transport but also promotes G4 decomposition at the anode surface, leading to the formation of an organic-rich SEI layer with poor ionic conductivity and a high Li+ diffusion barrier (~35.17 kJ mol−1). In contrast, in the TFA-containing electrolyte, the strong ionic interaction between Li+ and TFA− effectively disrupts the Li+–G4 coordination. This lowers the desolvation energy to 46.31 kJ mol−1, allowing G4 to be more readily displaced from the solvation shell and facilitating TFA−-driven interfacial reactions. As a result, a more uniform and inorganic-rich SEI is formed, dominated by stable compounds like LiF and Li3N. This layer exhibits improved ionic conductivity, reflected in the reduced diffusion barrier of Li+ (~32.01 kJ mol−1), which in turn supports smoother lithium deposition and better electrochemical performance in LOBs [78].

Further extending these insights, several recent studies have explored how the intentional selection and design of electrolyte components, whether salts or solvents, can be strategically employed to engineer the SEI via controlled electrolyte reaction. Broadly, the methods can be classified into two categories: salt-driven SEI formation, where the choice of lithium salt or anion additives governs the reaction pathway; and solvent-driven strategies, which utilize non-traditional solvent systems to influence solvation structure and interfacial decomposition dynamics.

In salt-driven systems, researchers have shown that combining anions with complementary reactivity can promote the formation of multifunctional SEIs. A representative example is the study by Marangon et al. [79], which explored a dual-salt electrolyte composed of LiNO3 and LiTFSI in highly concentrated glyme-based solvents. In these concentrated electrolytes, lithium ions are predominantly coordinated by anions rather than solvent molecules, shifting the interfacial decomposition pathways toward the formation of beneficial inorganic SEI components such as LiF, Li3N, and Li2CO3. Depth-profiled XPS analysis indicated that the composition of the SEI varied with depth, suggesting a heterogeneous but functionally synergistic interphase.

The formation of LiF- and Li3N-rich interphases is governed by distinct kinetic factors that determine their nucleation and growth pathways. The generation of LiF primarily depends on anion decomposition kinetics and local fluorine availability, where a high desolvation energy barrier favors surface-confined reactions producing dense, passivating layers. In contrast, Li3N formation involves multistep nitrogen reduction and diffusion processes that require sufficient ionic mobility and electronic accessibility at the Li surface. These differences lead to a stratified SEI structure in which LiF dominates the outer mechanically protective region, while Li3N enriches the inner ion-conductive phase [79]. Operando and in situ spectroscopic techniques, such as XPS, Raman, and solid-state NMR, offer powerful means to distinguish these roles. Together, these approaches elucidate how kinetic control of anion decomposition and nitrogen reduction pathways governs the composition and performance of SEI layers in LOB systems.

This SEI contributed to improved mechanical integrity, enhanced ionic conductivity, and increased interfacial stability. A similar dual-anion concept was explored by Zhang et al. [20], who employed a combination of LiNO3 and lithium (fluorosulfonyl)(pentafluoroethanesulfonyl)imide (LiFPFSI) in a TEGDME solvent system. At an optimized 1:1 ratio, this formulation facilitated the formation of a chemically robust SEI composed primarily of LiNO2, Li3N, and LiF. These SEI components contributed complementary functionalities: LiNO2 served as an effective oxygen barrier, Li3N provided fast lithium-ion transport pathways, and LiF offered strong chemical passivation. The resulting hybrid interphase suppressed interfacial side reactions, minimized impedance growth, and enabled stable lithium cycling over extended periods. As a result, the dual-salt system effectively suppressed dendritic growth and mitigated parasitic reactions, particularly in oxygen-containing environments.

This section focuses on how solvents and salts in the electrolyte contribute to SEI formation on the lithium anode. While such salt-driven interfacial effects are effective on their own, they can be further enhanced when combined with RMs, as will be explored in later chapters. A notable example is the study by Ahmadiparidari et al. [53], where lithium iodide (LiI) was introduced alongside LiNO3 in an ionic liquid-based electrolyte. Interestingly, LiI serves a dual purpose in this system functioning both as a salt and as a source of iodine-based redox mediators. While the NO3− anions decompose at the lithium surface to form nitrogen-rich SEI species such as Li3N, the iodide ions contribute to the formation of iodine-containing compounds that further stabilize the interphase. Together, these components build a protective SEI that suppresses parasitic reactions and improves long-term anode stability. This work demonstrates how integrating multifunctional salts like LiI into the electrolyte can bridge the roles of ion transport, redox mediation, and interfacial engineering within a single formulation.

In contrast to salt-driven strategies, solvent-mediated SEI formation utilizes the inherent solvation characteristics and chemical interactions of unconventional solvents to direct interfacial reactions. A representative case is the study by Li et al. [80], who developed a deep eutectic electrolyte (DEE) by combining N-methylacetamide (NMA) with LiTFSI. This eutectic system is not a simple solvent-salt mixture but rather a structurally reconfigured solvation environment where strong interactions between the carbonyl oxygen of NMA and Li+, as well as hydrogen bonding between the NH group and TFSI−, disrupt the original ionic lattice of the salt. This reorganization weakens the Li+–solvent interaction, which in turn promotes preferential anion decomposition over solvent degradation during SEI formation. As a result, the interphase is enriched with inorganic species such as LiF, and LixN components known for their chemical inertness, ionic conductivity, and structural stability. Furthermore, the dense hydrogen-bonding network of the DEE matrix suppresses the formation of volatile or reactive intermediates and enhances thermal and electrochemical robustness.

Contrary to the prevailing view that oxygen radicals are detrimental to lithium metal anodes, Zhao et al. [21] offered a more nuanced perspective by examining how oxygen influences SEI formation at the Cu/DMSO interface using in situ spectroscopic techniques such as FTIR, SERS, and DEMS. Their study revealed that, rather than promoting harmful reactions, the presence of oxygen can suppress the undesirable decomposition of DMSO, particularly the cleavage of C–S bonds that generates unstable intermediates like CH3• radicals and unsaturated species (e.g., C=C and C≡C). These decomposition pathways, dominant in oxygen-free conditions, lead to porous and chemically fragile SEIs. In contrast, oxygen inhibits these reactions and facilitates the formation of a denser, more uniform SEI with fewer gaseous byproducts. This counterintuitive result underscores that oxygen, when properly integrated into electrolyte design, can enhance interfacial stability by steering solvent decomposition along more favorable routes.

Oxygen crossover and ROS continuously interact with SEI components, altering their chemical evolution and stability. Excess ROS oxidize organic moieties and generate structural heterogeneity, while controlled oxygen incorporation favors the growth of oxygen-tolerant inorganic phases such as Li2O, Li2CO3, and LiF. These stable phases form a compact, oxygen-resistant shell that mitigates electrolyte degradation and interfacial impedance. Therefore, SEIs designed for oxygen-rich LOB systems should combine robust inorganic protection with flexible, ion-conductive organic frameworks to sustain long-term stability under repeated oxygen exposure [21].

Together, these findings illustrate the diversity of strategies available for electrolyte-driven SEI formation. Whether through the deliberate selection of salt pairs that decompose into functional inorganic components or the use of solvents that suppress parasitic reactions while directing SEI chemistry, the overarching principle remains the same: the SEI can and should be engineered. It is no longer viewed as a passive layer that simply accumulates over time, but as an active, dynamic structure that evolves in tandem with battery operation. When properly designed, the SEI not only protects the lithium surface but also mediates ion transport, suppresses side reactions, and adapts to electrochemical conditions. This shift in perspective from passive byproduct to tunable interface marks a fundamental advancement in LOBs research.

3.2. Metal-Iodide-Induced Surface Conversion Strategy

Among the range of reaction-driven interfacial engineering strategies proposed for LOBs, halide-mediated surface conversion has emerged as one of the most effective routes to chemically stabilize lithium metal [60,81,82,83]. Unlike artificial coatings or physical barriers described in previous sections, these systems rely on in situ redox reactions that actively transform the Li surface into more lithiophilic, dendrite-resistant interphases [84,85]. Metal iodides serve a dual role in this context: as soluble redox mediators for oxygen electrocatalysis and as precursors that undergo preferential reduction to form protective metal or alloy layers directly on the Li anode [86,87]. This fundamentally reactive approach diverges from passive surface protection strategies and has enabled the development of chemically adaptive interfaces that remain compatible with the oxygen-rich and electrochemically dynamic environment of LOBs.

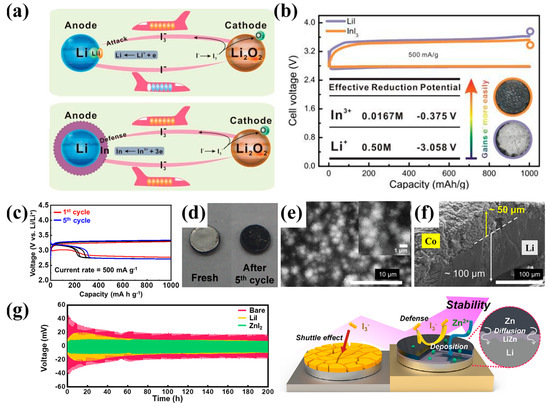

The concept was first demonstrated by Zhang et al. [45] through the use of indium iodide (InI3), in what became the prototypical “self-defense redox mediator.” Upon charging, the I3− species is oxidized at the cathode and can undesirably diffuse toward the anode, triggering shuttle effects and Li corrosion (Figure 7a, top). However, In3+ ions in the electrolyte are preferentially reduced on the lithium surface before Li+ plating occurs, forming a conformal indium metal layer that serves as a sacrificial shield against I3− crossover and dendritic nucleation (Figure 7a, bottom). This electrochemical selectivity is driven by the difference in reduction potentials between In3+ (−0.375 V vs. Li/Li+) and Li+ (−3.058 V), as illustrated in Figure 7b. As a result, the InI3-containing cell exhibits lower charge overpotentials and improved cycling efficiency, compared to its LiI counterpart. The optical images in Figure 7b inset visually confirm the protective behavior of the In layer by showing suppressed blackening of the Li surface after cycling. This dual-functionality mediating cathodic oxygen evolution while simultaneously stabilizing the anode marked a paradigm shift in redox mediator design.

Figure 7.

(a) Schematic illustration of the iodide shuttle effect during charge (top) and the formation of a protective indium layer using InI3 as a self-defense redox mediator (bottom). (b) Galvanostatic discharge–charge curves of LOB cells containing LiI or InI3 (Reproduced with permission from Ref. [45], copyright 2015, Royal Society of Chemistry). (c) Voltage profiles comparing 1st and 5th cycles of CoI2−SDRM cells. (d) Photographs of Li anode before and after cycling with CoI2. (e) SEM image of Co nanoparticle layer on Li surface. (f) Cross-sectional SEM showing ~100 μm Co−based protective layer (Reproduced with permission from Ref. [88], copyright 2022, Elsevier). (g) Long−term cycling stability of symmetric cells (bare, LiI, ZnI2), and schematic of ZnI2−induced LiZn/Zn protective layer formation and I3− suppression. (Reproduced from Ref. [89]).

Building on this framework, Lee et al. [88] introduced cobalt iodide (CoI2) as an alternative halide capable of providing additional electronic benefits. In this system, Co2+ ions are electrochemically reduced on the lithium surface to deposit a metallic cobalt layer, which, although not forming a stable alloy with lithium, acts as a highly conductive and lithiophilic interfacial scaffold. This metallic Co interphase lowers local nucleation overpotentials and homogenizes lithium ion flux, effectively guiding uniform Li plating and suppressing dendrite nucleation. The effectiveness of this strategy is demonstrated in Figure 7c, where CoI2-modified cells exhibit a ~0.6 V reduction in the charge/discharge voltage gap over just five cycles, compared to bare Li. Figure 7d shows the visual transition of the Li surface from a metallic sheen to a darkened, Co-coated appearance after cycling. SEM analysis (Figure 7e) reveals a dense layer of deposited Co nanoparticles, while cross-sectional imaging (Figure 7f) confirms the formation of a ~100 μm thick protective layer, with ~50 μm attributed to cobalt. Unlike the indium-based system, where protection is primarily chemical, the cobalt layer introduces a kinetic dimension to the interfacial regulation by improving charge transfer characteristics. The system is thus evaluated as a “second-phase catalytic interphase,” promoting electrochemical stability by modulating both Li+ flux and surface energetics.

The most recent advancement in this trajectory was achieved by Hwang et al. [89], who reported the use of zinc iodide (ZnI2) as both a redox mediator and an in situ alloying agent. Unlike In or Co, Zn2+ ions form a thermodynamically stable LiZn alloy upon reduction, yielding a robust bilayer structure composed of Zn metal atop a LiZn alloy. This interphase demonstrates superior lithiophilicity and structural integrity, enabling dendrite-free lithium deposition even under high areal capacities and extended cycling. Long-term galvanostatic cycling in symmetric Li||Li cells (Figure 7g, left) clearly shows that ZnI2-treated Li exhibits significantly lower polarization compared to both bare Li and LiI-treated samples. Furthermore, the schematic illustration in Figure 7g (right) captures the multifaceted mechanism of ZnI2: Zn2+ diffuses into Li to form a stable alloy, while I3− is scavenged or repelled, thereby preventing redox shuttle and SEI disruption. In addition to its anode-facing benefits, ZnI2 also enhances the cathodic decomposition of Li2O2, reducing charge overpotentials and promoting discharge product reversibility. This unique bipolar activation-concurrently stabilizing both electrodes-positions ZnI2 as the most advanced metal halide system to date, effectively integrating redox mediation, anode protection, and cathode catalysis in a single additive.

While alloy-forming additives such as ZnI2 effectively combine anode protection and redox mediation, they also introduce several intrinsic trade-offs. The in situ formation of the Li–Zn alloy consumes active lithium and can slightly reduce initial Coulombic efficiency, while the presence of transition-metal species increases interfacial complexity and potential impedance growth during long-term cycling. Moreover, excess Zn2+ or I3− can hinder oxygen transport or trigger parasitic reactions if not precisely balanced. In particular, both overly high and insufficient ZnI2 concentrations lead to performance degradation; high concentrations cause oxygen-diffusion limitation and overpotential increase, whereas low concentrations fail to sustain continuous Li–Zn alloy protection. Therefore, the optimization of alloying kinetics and redox-mediator concentration is essential to maintain both electrochemical reversibility and interfacial stability in these dual-functional systems [89].

Despite their chemical differences, the metal halide systems explored here—InI3, CoI2, and ZnI2—share a common mechanistic foundation: the use of deliberate redox chemistry to construct in situ formed, functionally adaptive interfacial layers that reinforce Li stability without external coatings. This class of reactive interphases represents a critical evolution beyond conventional artificial SEI strategies and provides a promising pathway toward intrinsically self-healing and oxygen-compatible lithium protection in next-generation LOB platforms.

3.3. Reactive Additive Engineering for In Situ Interface Formation

The inclusion of functional additives into electrolyte formulations offers a powerful means to modulate the structure and chemistry of the SEI [18,61]. Recent studies highlight that not only the solvent and salt components but also deliberate additive design can direct SEI composition, spatial arrangement, and stability against parasitic reactions [82,90]. These additives can be broadly categorized by their chemical nature and mechanism of action into two main classes: organic functional additives that react chemically to alter solvation or interfacial dynamics, and inorganic or polymer-based additives that physically modify SEI morphology or stability.

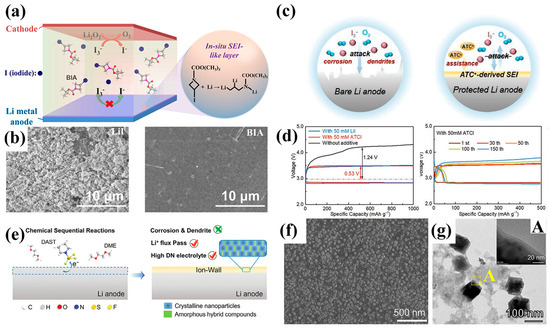

Organic additives have also been employed to simultaneously address cathodic and anodic interfacial challenges in LOBs. Li et al. [91] introduced 1-Boc-3-iodoazetidine (BIA) as a bifunctional organic iodine compound that acts both as a redox mediator and an anode-stabilizing agent (Figure 8a). The Boc-protected azetidine ring provides steric bulk and electron-donating character, while the iodine moiety introduces redox activity. Upon interaction with the lithium metal anode, BIA undergoes reductive cleavage, yielding LiI, which facilitates the formation and decomposition of Li2O2 at reduced overpotentials during charge. Simultaneously, the decomposition of BIA gives rise to organoiodide fragments that coordinate with lithium and solvent molecules at the anode surface, forming a thin, uniform passivation layer (Figure 8b). As shown in Figure 8c, a more tailored approach to iodine-containing redox mediators was presented by Sun et al. [92], who designed acetylthiocholine iodide (ATCI) as a bifunctional molecule combining redox activity and interfacial stabilization. Unlike previously reported organic iodides, ATCI introduces a large quaternary ammonium-based cation (ATC+) that plays a critical role in anode protection. During battery operation, the ATC+ cation migrates toward the lithium surface and undergoes reductive decomposition to generate N- and S-containing fragments. These fragments contribute to a chemically stable SEI rich in Li3N, Li2S, and Li2CO3. This dual functionality allows ATCI to reduce charge overpotential and effectively suppress parasitic reactions at the anode interface, achieving significantly improved cycle life compared to LiI-only systems. Specifically, ATCI-containing cells demonstrated a remarkably extended cycle life of approximately 190 cycles at a charging voltage of ~3.49 V, more than six times higher than the ~27 cycles observed with conventional LiI-based redox mediators (Figure 8d). Building on this concept, Wang et al. [93] developed a dual-component additive system using 3-iodooxetane (IOD) and aluminum trichloride (AlCl3) to address both redox mediator shuttling and interfacial instability. While IOD alone struggles to release iodine for redox mediation, the introduction of AlCl3, a hard Lewis acid, catalyzes iodine dissociation and triggers a ring-opening reaction that yields both iodide ions and reactive organic intermediates. These components lead to the formation of an organic–inorganic hybrid SEI layer composed of flexible oligomers and rigid inorganic species like Al2O3 and LiCl. This multifunctional interphase simultaneously reduces charge overpotential, suppresses the attack of I3− on the lithium metal surface, and accommodates volume changes during cycling.

Figure 8.

(a) Schematic illustration of the bifunctional mechanism of BIA at the lithium anode. (b) SEM images of the anodes with LiI and BIA after 60 cycles (Reproduced with permission from Ref. [91], copyright 2021, ACS Publications). (c) Schematic of the dual−function mechanism of ATCl. (d) Cycling performance comparison of ATCI and LiI in LOBs (Reproduced with permission from Ref. [92], copyright 2022, Wiley−VCH). (e) Conceptual diagram illustrating the in situ formation of an “ion−wall” structure by DAST additive. (f) Magnified top−view SEM image of the lithium surface modified by the ion−wall. (g) TEM image of the ion−wall; LiF particles encapsulated within an amorphous matrix (Inset A: High-resolution TEM image) (Reproduced with permission from Ref. [19], copyright 2024, Wiley−VCH).

Following the use of iodine-based organic complexes, Liao et al. [94] developed a bromine-containing alternative, 4-bromomethyl-phenylboronic acid (BPLA), which offers a distinct path toward redox mediation and SEI formation. Unlike iodine complexes that rely on I−/I3− shuttling and often suffer from instability at the lithium surface, BPLA generates Br− during cycling to serve as a redox mediator while its boronic acid group participates in forming a dynamic SEI through reversible B–O bonding. This bifunctional behavior allows for controlled mediator release and adaptive interphase formation without the complications of iodine shuttling. Importantly, the system was shown to operate not only in pure O2 but also in ambient air, demonstrating environmental tolerance. Cells using BPLA maintained stable cycling over 180 cycles at 1000 mA/g, confirming its robustness under practical conditions.

In addition to the strategies based on redox mediators, several recent studies have explored organic additives that promote the in situ formation of LiF-rich SEI layers at the lithium metal surface. These SEIs are particularly attractive due to their high electrochemical stability and mechanical robustness, which help suppress dendrite formation and minimize side reactions in LOBs. A notable example is the work by Liu et al. [19], who introduced 4-dimethylaminobenzene sulfonyl fluoride (DAST) as a functional additive for use in high donor number electrolytes (Figure 8e). High-DN solvents typically offer good solubility for oxygen and intermediates but are known to be highly reactive toward lithium metal. To address this, DAST was added to the electrolyte as a fluorine source that selectively decomposes at the lithium surface. Upon reduction, the sulfonyl fluoride moiety is cleaved, releasing F− ions that immediately react with lithium to form a dense LiF layer. The resulting interphase behaves like an “ion wall,” effectively passivating the lithium surface and limiting solvent decomposition. Direct morphological evidence of this “ion wall” architecture was provided through high-resolution imaging. The magnified top-view SEM image (Figure 8f) revealed the presence of numerous regularly shaped nanoparticles embedded within the SEI film, suggesting a structured and uniform surface layer. Further confirmation came from TEM analysis (Figure 8g), which showed well-defined cubic nanoparticles enveloped in an amorphous matrix. This composite structure, crystalline LiF nanoparticles within a flexible organic film, confirms the hybrid nature of the SEI and supports its function as a mechanically robust, ionically conductive barrier.

An alternative approach to generating LiF-enriched SEI layers was demonstrated by Wu et al., who introduced 4-methylbenzenesulfonyl fluoride (4-MBSF) as a sulfonyl fluoride-based electrolyte additive. This molecule features a –SO2F functional group capable of reacting directly with the native LiOH layer that naturally forms on lithium metal in ambient conditions. This reaction yields a LiF-rich interphase at the anode surface. The generated LiF layer serves as the inorganic scaffold of the SEI, suppressing dendrite growth and improving interfacial stability and ionic transport. In parallel, the phenyl ring of 4-MBSF contributes to mechanical flexibility, buffering the volume fluctuations of lithium plating and stripping. A similarly effective strategy was proposed by Zhao et al. [78], who employed 4-nitrobenzenesulfonyl fluoride (NBSF) as a dual-function electrolyte additive to construct a robust organic–inorganic hybrid SEI on the lithium metal surface. Like 4-MBSF, NBSF contains a reactive –SO2F group that selectively reacts with pre-existing LiOH on the anode to generate a LiF-rich interphase. In addition to LiF, the incorporation of nitro groups enables the formation of Li3N, contributing further to chemical stability and enhanced ionic conductivity. This combination of LiF and Li3N offers both mechanical strength and effective passivation against parasitic reactions. Meanwhile, the phenyl backbone of NBSF enhances the elasticity and chemical compatibility of the interphase, allowing it to accommodate volume changes during repeated cycling. As a result, lithium–oxygen cells incorporating NBSF achieved extended cycling performance, maintaining stable operation for up to 286 cycles with a current density of 1000 mA/g.

In contrast to the organic additive strategies discussed previously, which rely on chemical decomposition at the Li surface to form SEI layers, Li et al. [95]. proposed an inorganic–polymer hybrid approach centered on physical reinforcement and nucleation control. They introduced a composite SEI formed in situ from PEO and tin(II) fluoride (SnF2) to stabilize the lithium metal anode in LOBs. The SEI is prepared by dissolving SnF2 and PEO in DMSO, a solvent selected for its excellent solubility for SnF2 and thermal stability. This mixture is drop-cast onto the Li surface, where a simple and rapid in situ reaction occurs between SnF2 and metallic lithium, leading to the spontaneous formation of a robust hybrid interphase. Unlike soluble organic molecules that diffuse and react electrochemically, SnF2 acts through direct chemical exchange with lithium metal, with the following reaction: SnF2 + 2Li → 2LiF + Sn, and 5Li + 2Sn → Li5Sn2. The resulting products include LiF, which contributes high mechanical strength and passivation, and Li–Sn alloy, which exhibits strong lithiophilicity and facilitates uniform Li nucleation. By combining LiF for rigidity, Li–Sn alloy for uniform plating, and PEO for mechanical buffering, this approach offers a fundamentally different route from reactive organic additives, focusing instead on interfacial uniformity and mechanical resilience to suppress dendrite formation and extend battery lifespan.

The chemical protection strategies discussed above rely on in situ interfacial chemistry that dynamically reconstructs the SEI during cycling. In anion-rich or additive-modified electrolytes, decomposition of reactive species such as LiNO3, LiFPFSI, and sulfonyl fluorides generates LiF- and Li3N-based inorganic frameworks with high ionic conductivity and low electronic leakage. Meanwhile, organic moieties derived from solvents or functional additives interpenetrate the inorganic matrix, forming flexible hybrid SEIs that accommodate Li volume change. This compositional synergy regulates charge transfer kinetics, blocks oxygen and redox mediators, and enables self-stabilizing interphases under high current densities and oxygen-rich environments.

Although chemical approaches provide dynamic and adaptive SEI formation, they also present notable challenges. The stability of in situ-generated SEIs often depends heavily on electrolyte composition and cycling conditions, making reproducibility and controllability difficult. Reactive additives or halide mediators can trigger undesired side reactions, gas evolution, or continuous electrolyte consumption. In many cases, these SEIs remain chemically heterogeneous, leading to localized variations in ionic conductivity and mechanical strength. Furthermore, the use of complex electrolyte formulations can reduce oxygen solubility or increase viscosity, limiting oxygen transport and overall cell kinetics. Therefore, optimizing interfacial chemistry requires not only designing robust SEI components but also ensuring compatibility with the electrolyte and scalability for practical systems.

When evaluating multifunctional additives, experimental protocols must be carefully designed to decouple the effects of redox mediator shuttling from intrinsic lithium deposition behavior. Symmetric Li‖Li cells without mediators can serve as a baseline to probe dendrite morphology, interfacial resistance, and SEI stability under purely electrochemical conditions. Parallel Li‖Li or Li‖O2 cells containing defined concentrations of redox mediators can then be used to identify shuttle-induced polarization and parasitic reactions through differential voltage and impedance analysis [78,95]. Furthermore, multi-modal operando characterization, such as optical microscopy, cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM), synchrotron X-ray spectroscopy or tomography, and in situ Raman or FTIR spectroscopy, provides complementary insight into the spatial and chemical evolution of the SEI during cycling. These combined diagnostic approaches enable direct correlation between lithium surface morphology, mediator activity, and interfacial chemistry. Such systematic and multi-scale experimental design allows for clear differentiation between shuttle-related effects and intrinsic anode instability.

Collectively, these additive engineering strategies highlight diverse mechanisms ranging from redox mediation to interfacial stabilization and mechanical reinforcement for optimizing SEI formation in LOBs. Whether through reactive organic species or inorganic-polymer hybrids, tailored additive design offers a powerful tool to address the long-standing challenges of lithium metal anodes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of SEI/interfacial chemistry engineering strategies for LOBs. The table summarizes various electrolyte formulations and additive designs that enable in situ formation of robust SEI layers, outlining their mechanisms of interfacial stabilization and achieved electrochemical performance.

In recent developments, increasing attention has been given to the synergistic coupling between mechanically confining artificial protective layers and chemically adaptive electrolyte-derived interphases. The artificial layers physically regulate the lithium-ion flux and buffer volume expansion, maintaining structural integrity under high-rate cycling. Meanwhile, the dynamically reconstructing SEI components generated from electrolyte decomposition continuously heal interfacial defects and sustain ionic pathways. This dual protection mechanism offers complementary benefits: mechanical confinement suppresses dendrite initiation, while chemical adaptability accommodates repeated plating/stripping-induced stress. Together, they form an integrated interphase that balances rigidity and flexibility, leading to uniform Li deposition and enhanced rate capability. Such synergy highlights that quantitative modeling of lithium cycling behavior must consider both elastic stress distribution within the artificial layer and chemical evolution at the SEI, enabling predictive design of next-generation stable lithium interfaces.

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

4.1. Conclusions

LOBs have long been recognized for their remarkable theoretical energy density, offering a promising route toward next-generation rechargeable energy storage systems [96,97]. Over the past decade, most research efforts have focused on addressing challenges at the cathode side such as the sluggish oxygen reduction and evolution reactions, unstable discharge products, and parasitic reactions in oxygen-rich environments [98,99]. These issues have dominated performance at the typically low current densities used in laboratory studies, where the anode-related limitations were relatively less apparent [100,101].

However, as the field progresses toward practical, high-energy, and high-power operation, LOBs are now being tested under higher current densities and higher areal capacities [97]. Under these realistic conditions, the instability of the lithium anode, manifested as dendritic growth, non-uniform Li deposition, and repeated SEI breakdown, emerges as a critical bottleneck for both safety and durability [102]. The dendrite issue, which was once masked by cathodic limitations, has now become one of the primary factors restricting further development.

Recent advances in interfacial engineering have opened new pathways to stabilize the LMA in LOB systems [20,71,103]. Approaches such as artificial protective coatings, electrolyte and additive optimization, and functional separator designs have been shown to suppress parasitic side reactions and improve interfacial uniformity. In particular, hybrid inorganic–polymer interphases and in situ generated LiF- or Li3N-enriched SEI layers have demonstrated the ability to balance mechanical integrity with ionic conductivity, providing more stable cycling behavior [103]. Overall, these achievements confirm that rational anode interface engineering is the cornerstone for improving the electrochemical stability of LOBs and serve as a strong foundation for the next stage of development toward practical systems (Figure 9).

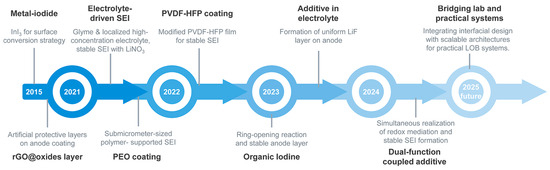

Figure 9.

Chronology of the development and application of anode protection strategies in LOBs.

4.2. Future Perspectives

Moving beyond the recognition of anode instability, future research on LOBs should concentrate on establishing design principles that enable stable lithium cycling under practical, high-rate conditions. Rather than simply preventing dendrite formation, the focus must shift toward understanding and controlling the dynamic interfacial phenomena that occur during fast plating and stripping in oxygen-rich environments. Developing interphases capable of real-time adaptation, those that can redistribute local current density, buffer mechanical stress, and self-repair minor defects could provide a realistic pathway to durable operation.

Equally important is the synergistic design of electrolytes and separators, which directly influences ion transport and interfacial reactivity. Future electrolytes must simultaneously maintain redox stability, high oxygen solubility, and compatibility with the lithium surface. Engineering separators with tailored pore structures or functional coatings that regulate Li+ flux and suppress reactive oxygen crossover may further enhance both performance and safety. In this regard, hybrid or quasi-solid-state electrolytes that combine mechanical rigidity with interfacial compliance have emerged as particularly promising options.

To accelerate material discovery, computational modeling and advanced characterization should be integrated more closely with experimental efforts. Multiscale simulations linking atomic-scale reactions to macroscopic cell behavior can provide valuable insight into SEI evolution and lithium growth kinetics. Meanwhile, in situ and operando techniques such as cryo-TEM, synchrotron X-ray spectroscopy, and Raman mapping will be indispensable for observing interfacial dynamics under realistic electrochemical conditions. Such multi-scale simulation frameworks can bridge the gap between atomic-level interfacial reactions and macroscopic electrode behavior under realistic operating conditions. Atomistic approaches such as DFT and molecular dynamics (MD) elucidate ion desolvation mechanisms and the thermodynamic stability of SEI-forming species, whereas mesoscale models, including phase-field and kinetic Monte Carlo simulations, capture morphological evolution and dendrite propagation over extended timescales. At the continuum level, finite-element methods can quantify current-density heterogeneity and stress distribution in full-cell geometries. When combined with operando characterization, these hierarchical simulations enable predictive understanding of interphase evolution and dendrite dynamics, providing a powerful toolset for guiding the rational design of stable lithium interfaces.

Finally, future progress will depend on translating these findings into engineering-relevant and scalable cell configurations. Most current studies are still based on idealized coin-cell or small single cell setups that do not fully capture the complex gas transport, electrolyte distribution, and interfacial dynamics occurring under realistic conditions. To truly exploit the intrinsic high energy density of oxygen chemistry, future evaluations should move toward larger-area or scaled-up cells that can better reflect practical design constraints, such as oxygen management and electrode architecture. Expanding studies to these more representative systems will enable a more accurate assessment of energy utilization, stability, and system-level feasibility. In this context, closer collaboration among materials scientists, electrochemists, and system engineers will be essential to bridge the gap between fundamental research and the realization of safe, high-performance, and durable LOBs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C. and M.-C.S.; formal analysis, C.C. and M.-C.S.; investigation, C.C., M.-C.S., M.K. and J.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C. and M.-C.S.; writing—review and editing, M.-C.S., M.K. and J.Y.; visualization, C.C., M.-C.S. and M.K.; supervision, C.C.; funding acquisition, C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Sungshin Women’s University Research Grant of H20250103.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bai, T.; Li, D.; Xiao, S.; Ji, F.; Zhang, S.; Wang, C.; Lu, J.; Gao, Q.; Ci, L. Recent progress on single-atom catalysts for lithium–air battery applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 1431–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Yang, J.; Chu, S.; Guo, S.; Zhou, H. Solid-state Li–air batteries: Fundamentals, challenges, and strategies. SmartMat 2023, 4, E1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, Y.; Choi, J.W. Navigating interfacial challenges in lithium metal batteries: From fundamental understanding to practical realization. Nano Converg. 2025, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.-S.; Kwak, W.-J.; Chae, S.; Wi, S.; Li, L.; Hu, J.; Tao, J.; Wang, C.; Xu, W.; Zhang, J.-G. Stable Solid Electrolyte Interphase Layer Formed by Electrochemical Pretreatment of Gel Polymer Coating on Li Metal Anode for Lithium–Oxygen Batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 2021, 6, 3321–3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]