Abstract

A Machine Learning (ML)-based surrogate modeling framework is presented for mapping structure–property relationships in architected Ti6Al4V cylindrical TPMS metamaterials subjected to quasi-static compression. A Python–nTop pipeline automatically generated 3456 cylindrical shell lattices (Gyroid, Diamond, Split-P), and ABAQUS/Explicit simulations with a Johnson–Cook failure model for Ti6Al4V quantified their mechanical response. From 3024 valid designs, key mechanical properties targets including elastic modulus (E), yield stress (Y), ultimate strength (U), plateau stress (PL), and energy absorption (EA) were extracted alongside geometric descriptors such as surface area (SA), surface-area-to-volume ratio (SA/VR), and relative density (RD). A multi-output surrogate model (feedforward neural network) trained on the simulated set accurately predicts these properties directly from seven design parameters (thickness; unit cell counts in X, Y, and Z directions; unit cell orientation; height; diameter), enabling rapid property estimation across large design spaces. Topology-dependent trends indicate that Split-P exhibits the highest strength, energy absorption, and total SA, and shows the largest variation in SA/VR; Gyroid exhibits the lowest SA with a moderate SA/VR; and Diamond is the most compliant lattice and maintains a higher SA/VR than Gyroid despite lower SA. RD increases with both SA and SA/VR across all topologies. The framework provides a reusable computational tool for architectured lattices, enabling quick prescreening of implant designs without repeated finite-element analyses.

1. Introduction

Bone tissue engineering is an approach for addressing significant issues related to bone repair [1,2]. Conventional bone grafting methods, such as autografts and allografts, have considerable limitations, including donor site morbidity, limited availability, and immune rejection [1,3,4]. Synthetic scaffolds are developed to enhance bone repair by mimicking bone architecture and morphology [5], providing crucial mechanical support and promoting cell attachment and tissue growth [6].

The design of bone scaffolds must consider key design requirements such as biocompatibility, appropriate porosity, mechanical strength, and structural stability under different loading conditions [7,8]. These factors play an essential role in ensuring the effectiveness and safety of the scaffolds in biomedical applications [9]. The mechanical requirements of bone implants vary based on their specific anatomical location [10]. Load-bearing implants, like those found in the femur or tibia, must have strong compressive strength and stiffness [11]. In contrast, non-load-bearing implants, such as those in cranial or facial bones, require lower stiffness and higher flexibility. Essential mechanical properties for scaffolds include elastic modulus (E), yield stress (Y) and ultimate strength (U), energy absorption (EA), and plateau stress (PL) [12]. Enhancing these characteristics guarantees practical compatibility with adjacent tissue and minimizes the likelihood of implant failure [13].

Triply periodic minimal surfaces (TPMSs) have attracted significant attention in bone scaffold design because they combine geometrical complexity with regular periodicity [14,15,16]. Unlike simple Euclidean geometries, TPMSs exhibit highly curved, non-self-intersecting surfaces that create complex, interpenetrating pore networks with very high surface-area-to-volume ratios (SA/VR). These characteristics are crucial for cellular attachment, proliferation, and nutrient transport [17]. Complex surfaces can be described as statistically rough or fractal and distinguished from smooth Euclidean surfaces by a smooth–rough crossover (SRC) boundary. In this sense, the TPMS-based titanium scaffolds considered here belong to the complex/rough class of surfaces due to their multiscale curvature and high SA/VR, which is expected to promote enhanced fluid transport and enhance surface interactions for cells [18]. TPMS architectures, like Gyroid, Split-P, and Diamond, enable accurate adjustment of mechanical properties and maintain sufficient porosity for successful tissue regeneration [19,20,21]. Their periodic surfaces (with no intersections) exhibit predictable mechanical behavior, making them ideal for various applications in bone implants [22].

Cylindrical scaffolds, due to resembling the morphology of long bones, like the femur, tibia, and humerus, are especially beneficial in bone implants [23]. These structures ensure uniform stress distribution and flexibility for different TPMS configurations [24]. TPMS-based cylindrical scaffolds have shown excellent structural strength and sufficient porosity, making them superior for vascularization and fluid flow [25]. Their scalability and customizability allow for use in various implant locations while ensuring optimal mechanical performance.

The choice of material plays a crucial role in the success of bone implants. Ti6Al4V is widely utilized in orthopedic applications due to its excellent biocompatibility, high strength-to-weight ratio, and corrosion resistance [26]. It is frequently used in joint replacement procedures [27] and dental implants [28]. Ti6Al4V’s combination of high strength and low density makes it suitable for load-bearing applications while ensuring long-term stability through bone integration [29]. In clinical applications, Ti6Al4V is typically used either as the standard Grade 5 alloy or as its extra-low-interstitial variant, Ti6Al4V ELI (Grade 23), which is specifically developed for biomedical applications. The ELI grade has the same nominal Ti6Al4V composition but stricter limits on interstitial elements such as oxygen, nitrogen, carbon, and iron, which slightly reduce yield strength while improving ductility, fracture toughness, and fatigue resistance. In this study, we use the term Ti6Al4V to denote implant-grade Ti6Al4V/Ti6Al4V ELI, and the material parameters employed in the simulations fall within the range reported for SLM-processed implant grade Ti6Al4V ELI.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is now commonly integrated into scaffold and implant design as a rapid, data-based alternative to complex numerical and huge experimental workflows. In hard tissue mechanics, artificial neural network (ANN) models have been utilized to map trabecular bone morphology and imaging descriptors directly to apparent stiffness, load-bearing capacity, and other quality indicators. This demonstrates that complex relationships between structure and property can be effectively captured from data [30,31]. Similar ANN frameworks have been applied to cartilage- and bone-mimicking scaffolds, where they predict effective elastic modulus, nonlinear load–displacement curves, and failure behavior for complex geometries [32,33]. Machine Learning (ML) workflows in bone tissue engineering combine FEA with regression or hybrid models to design TPMS scaffolds with specific stiffness and morphology. They also enable the inverse design of anisotropic bone scaffolds based on target elasticity matrices and optimize cylindrical TPMS implants through multi-objective optimization for mechanical and geometrical targets [34,35,36,37]. These advancements align with broader reviews showing how AI can enhance tissue-engineering workflows in biomaterial selection, scaffold design, fabrication, and performance prediction when combined with high-fidelity simulations and 3D printing [38].

In our previous work, TPMS lattices were optimized using a forward model in conjunction with NSGA-II [36]. The current study utilizes an ANN surrogate, which is trained on a comprehensive FEA dataset that includes 3024 cylindrical Ti6Al4V TPMS lattices. This approach allows us to investigate the relations between mechanical performance and the geometric features with design parameters. A Python-nTop workflow was used to generate Gyroid, Split-P, and Diamond structures based on systematically varied geometric inputs. These designs were subjected to quasi-static compression simulations using ABAQUS with the Johnson–Cook material model to capture the behavior of Ti6Al4V. The dataset facilitates the training of a multi-output ANN that can accurately predict key mechanical properties, including E, Y, U, EA, and PL, directly from design parameters. This approach delivers a reusable surrogate model that eliminates the need for repeated simulations, offering a scalable and efficient solution for evaluating new bone implant architectures.

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Design Parameters

This study focuses on the ANN-based prediction of mechanical performance in cylindrical lattice structures designed from three TPMS geometries: Gyroid, Split-P, and Diamond [15,20,39]. A total of 3024 unique designs were analyzed, generated by varying key design parameters consistent with our previous work [36] in which multi-objective optimization of cylindrical TPMS lattices was performed. The geometrical configuration of each lattice was controlled through seven design variables. Shell-based structures were generated with three different surface thickness (T) values of 0.2, 0.3, and 0.4 mm. To investigate how internal morphology influences performance, the unit cell sizes were adjusted along the X, Y, and Z axes (X-UC, Y-UC, and Z-UC) using two different size of 3 and 4 mm. Additionally, the rotational orientation of unit cells () around the X-axis was altered by 0°, 30°, and 60° to evaluate direction-dependent mechanical effects.

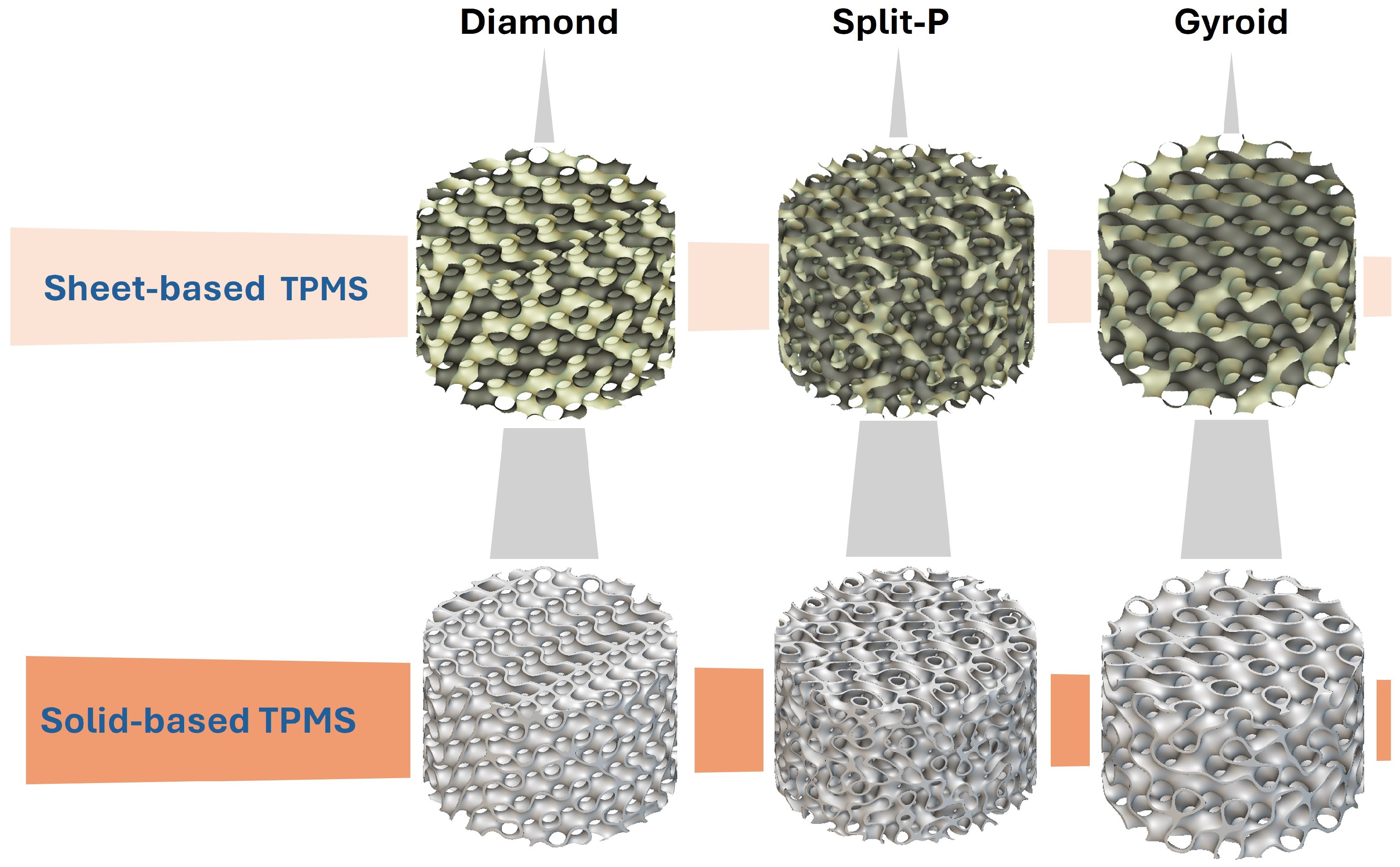

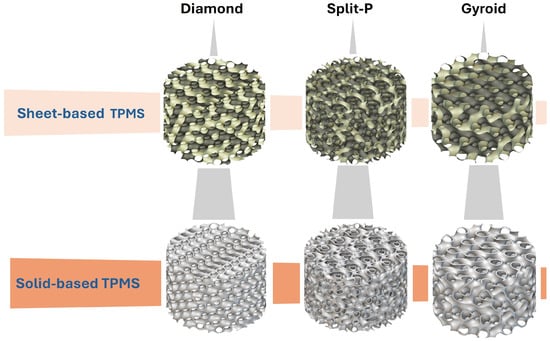

To simulate realistic implant geometries, the cylindrical lattices were designed with varying outer diameters (D; 5, 10, 15, and 20 mm) and heights (H; 8, 10, 15, and 20 mm), ensuring a diverse range of potential implant sizes. These parameterized designs enabled the generation of various structures, thereby enabling detailed predictive analysis of structure–property relationships. Table 1 briefly shows the design parameters in each column, and Figure 1 illustrates sheet-based and solid-based TPMS lattice configurations.

Table 1.

Design specifications for the lattice structures. All lengths are in (mm), and the angle is in degrees.

Figure 1.

Sheet-based and solid-based TPMS lattice structures.

Data Generation—Lattice Design

A full factorial design of the experiments was used to generate all possible combinations of the design parameters. This led to 1152 distinct lattice designs for each type of TPMS (Gyroid, Split-P, and Diamond), resulting in 3456 lattice configurations with different relative density (RD), porosity, surface area (SA), and SA/VR values.

A filtering step was conducted to exclude geometries with a height-to-diameter ratio constraint (H/D >= 2), which are prone to buckling and could potentially be unstable under compression. Thus, a total of 144 designs prone to buckling were excluded, leaving 3024 lattice designs for analysis.

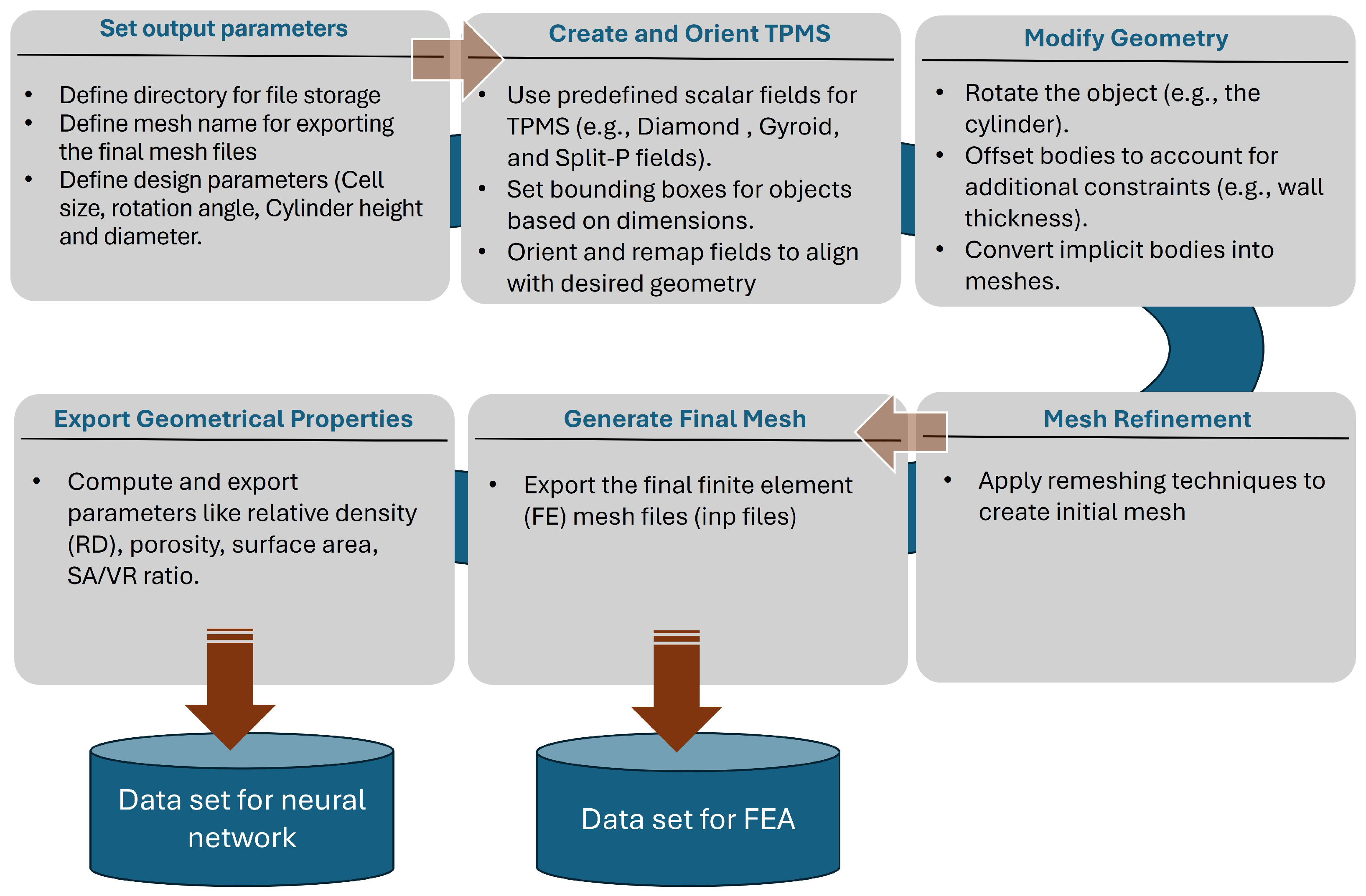

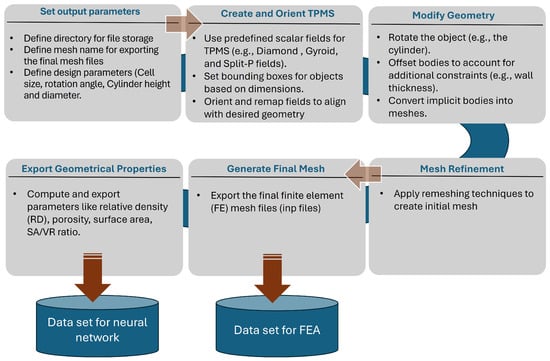

A Python (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA; version 3.X) script interfaced with the software nTop (nTop, Release 4.1, nTop Inc., https://ntop.com, New York, NY, USA) [40] was developed to automate data generation. This script generated the sheet-based lattice geometries based on the defined design parameters and exported them in the .inp file format, which is compatible with ABAQUS for simulation. Additionally, the lattice name and geometrical features, including SA, SA/VR, RD, and porosity, will also be exported to a text file for further processing. Figure 2 shows Workflow of generating sheet-based lattices and mesh files and computing geometric parameters in nTop to generate the ANN data set.

Figure 2.

Workflow of generating sheet-based lattices and mesh files and computing geometric parameters in nTop.

2.2. Finite Element Analysis

The software package ABAQUS/Explicit (Abaqus, Dassault Systèmes Simulia Corp., Providence, RI, USA; version 2022) was used for FEA utilizing the ABAQUS scripting interface and the Python programming language, which significantly reduces the time required for simulating numerous complex models. To validate the simulation workflow, we selected a representative Gyroid lattice structure that had been previously analyzed in [41]. This study also provided experimental tensile data for bulk Ti6Al4V, which were used to verify the accuracy of our simulations during the elastic-plastic stage. Since the referenced research did not include failure modeling in FEA, we performed a series of calibration simulations in this study to estimate appropriate Johnson–Cook failure parameters. Different combinations of , , and were tested while keeping and at zero. The resulting stress–strain responses were then matched as closely as possible to the experimental curve. The calibrated parameters (, , and ) were consistently applied across all lattice simulations to ensure a reliable representation of the material’s behavior. A constant velocity was applied in the loading direction to the upper plate, while the other degrees of freedom (DOF) were constrained. The lower plate remained fixed in all DOF. General contact was defined as “hard” between the lattice and the two plates, while penalty friction was implemented in the tangential direction. Self-contact was considered for the lattice to capture localized interactions within the lattice structure, resulting in more accurate predictions of post-buckling stiffness and failure behavior. The friction coefficient was set as 0.1. The elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio were defined as 107.5 GPa and 0.3, respectively [41]. Mesh sensitivity analysis was performed to ensure convergence of the mechanical response, and a global mesh size of 0.3 mm was selected as the optimal compromise between computational efficiency and result accuracy.

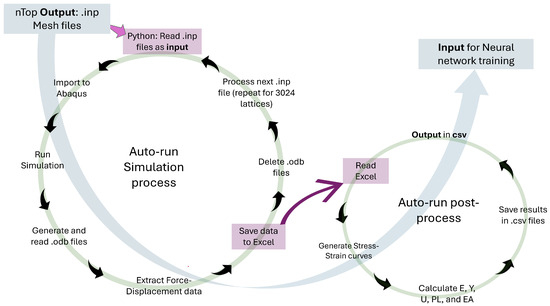

Data Generation—Automatic FEA

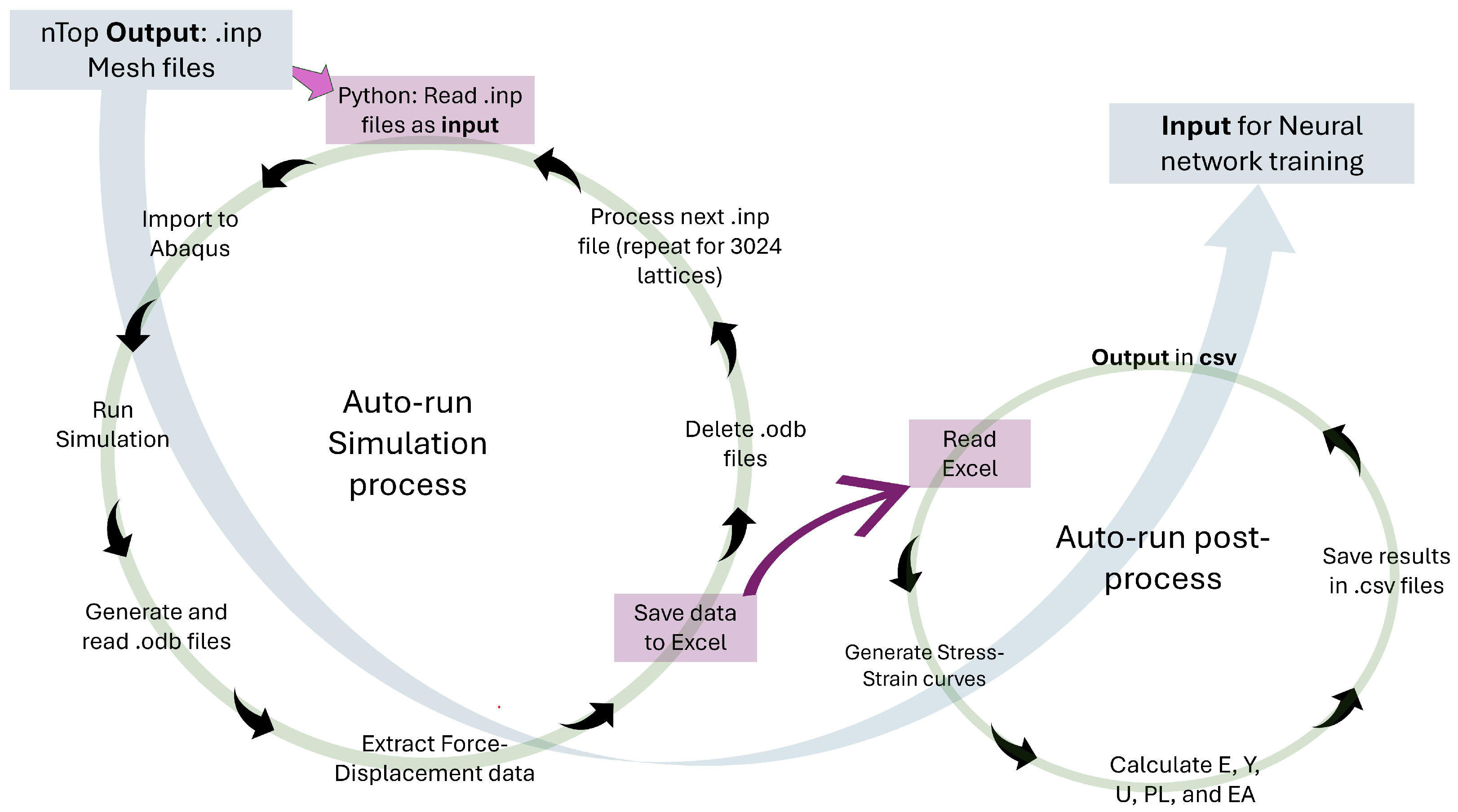

To handle the large number of TPMS designs and obtain consistent mechanical data, we developed a fully automated finite-element workflow in ABAQUS, summarized in Figure 3. nTopology first exports the lattice meshes as .inp files. A Python script then iterates over these files, automatically assigns the correct shell thickness to each sheet-based TPMS lattice, imports the model into ABAQUS, and runs a quasi-static compression analysis using the Johnson–Cook material and failure model for Ti6Al4V. For every one of the 3024 lattices, the script reads the resulting .odb database, extracts the reaction force–displacement response, writes the data to structured Excel files, and deletes the large .odb files to save disk space.

Figure 3.

Workflow diagram illustrating the automated process of finite-element simulations and post-processing for neural network training.

A second automated post-processing script (right loop in Figure 3) reads the stored force–displacement data, converts them to engineering stress–strain curves, and computes the key mechanical properties: E, Y, U, EA, and PL. These results are consolidated in compact .csv files, which serve as the input dataset for training the neural network. By automating both the simulation and post-processing stages, the workflow eliminates manual intervention, reduces the risk of user error, and ensures that all TPMS lattices are evaluated under identical modelling assumptions, leading to accurate, consistent, and reproducible mechanical characterization.

3. Artificial Neural Network

3.1. Neural Network Architecture

This study initially implemented traditional ML regression models to predict the mechanical properties of TPMS lattice structures. Random forest regressor (RFR) [42], and XGBoost regressor (XGBR) [43] were employed, which are widely used for regression tasks. LR provides a baseline model by assuming a linear relationship between input features and target variables [44]. RFR, an ensemble learning method, improves accuracy by training multiple decision trees and averaging their outputs, making it robust to noise [42]. XGBR, a gradient-boosting algorithm, further enhances predictive performance by sequentially optimizing decision trees and minimizing errors iteratively [43]. While these models demonstrated strong predictive capabilities, they could not fully capture the high-dimensional and nonlinear relationships inherent in complex TPMS lattice structures. Therefore, an ANN was developed to predict the mechanical properties of the TPMS lattice structures. The model is a feed-forward neural network (FNN) that takes the design parameters as inputs and simultaneously outputs all target mechanical properties. Through multiple hidden layers and nonlinear activation functions, the network learns deep, shared feature representations that capture complex relationships between geometry and response. In contrast to traditional regression or tree-based models, this ANN can exploit hierarchical patterns in the data, enabling more accurate and better predictions, especially when the mechanical behavior depends on interactions among several structural parameters.

The ANN used in this work is a fully connected feed-forward neural network for multi-output regression. The input layer receives the seven design parameters (thickness, unit cell counts, rotation angle, height, and radius), followed by three hidden layers with 128, 64, and 32 neurons, respectively, each using a ReLU activation function to capture nonlinear relationships between geometry and mechanical response. The output layer contains five neurons with linear activation, corresponding to the target mechanical properties. The network was implemented in TensorFlow/Keras and trained using the Adam optimizer with mean squared error as the loss function and mean absolute error as an additional performance metric, with early stopping based on the validation loss to prevent overfitting.

3.2. Training and Evaluation

The model was trained using the Adam optimizer, which adaptively updates the learning rate during training. Mean squared error (MSE) was used as the loss function, while mean absolute error (MAE) was monitored as an additional performance metric. The input features were standardized using StandardScaler, and the TPMS lattice design dataset was randomly split into 80% (2419 samples) for training and 20% (605 samples) for testing using a train–test split. The network was trained for up to 100 epochs with a batch size of 16, and the final model corresponds to the set of weights that minimized the validation loss. The predictive performance on the held-out test set was evaluated using MAE and the coefficient of determination (). The key parameters of the ANN are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Key hyperparameters of the ANN.

4. Results

4.1. Comparison of Average Mechanical Properties Across Lattice Structures

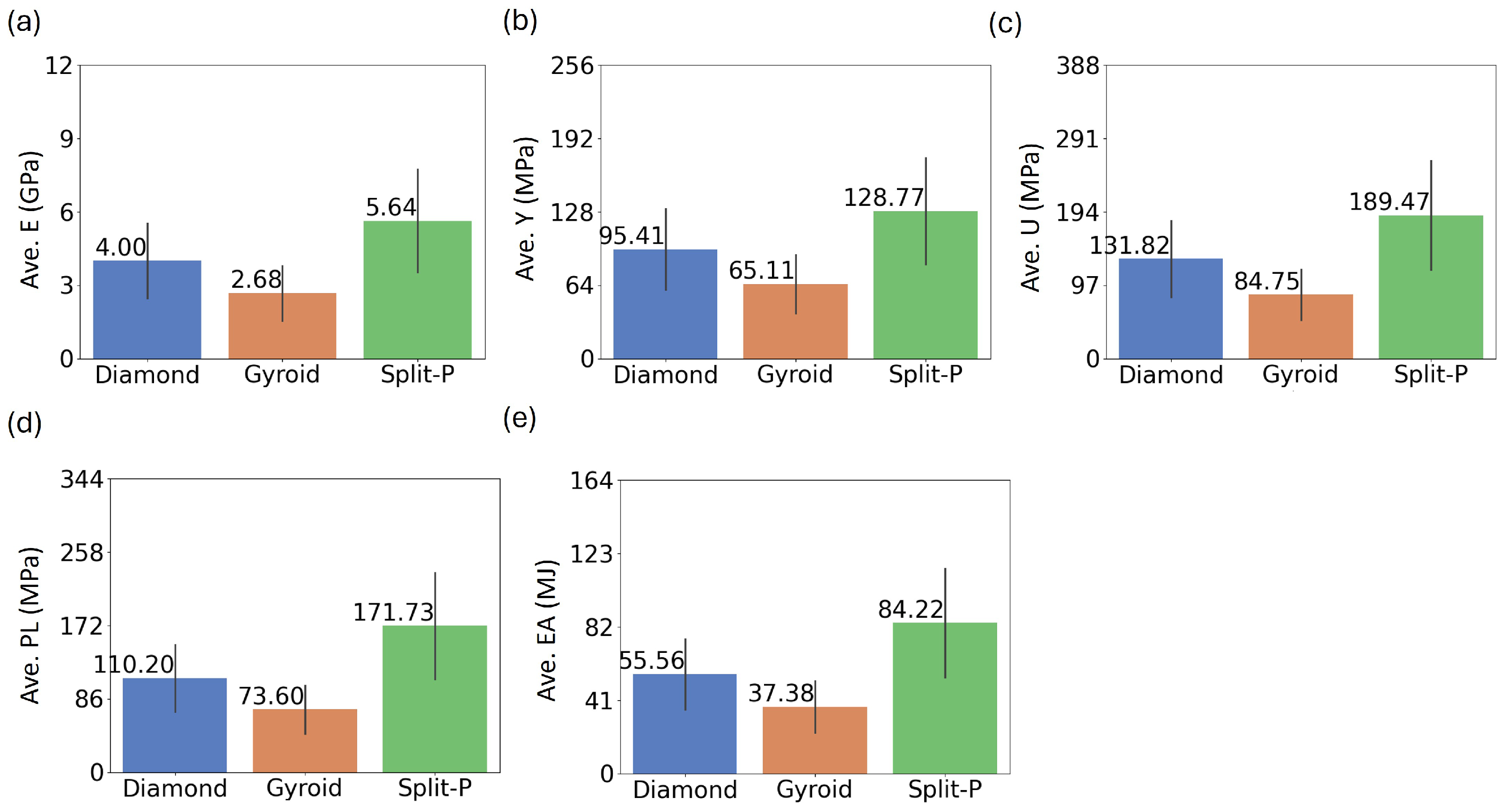

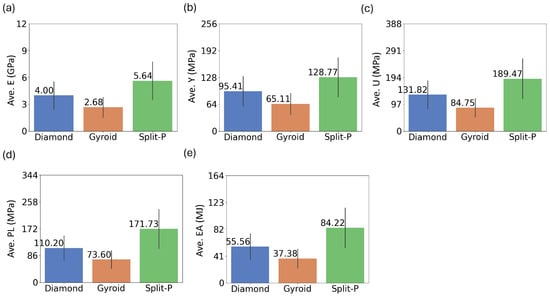

The bar plots in Figure 4 illustrate the average values of five key mechanical properties for the three lattice types. The results indicate that the Split-P lattice with an average stiffness of 5.64 GPa exhibits the highest average values across all mechanical properties, suggesting superior structural performance. Gyroid lattice demonstrates the lowest average stiffness at 2.68 GPa, while Diamond lattice keeps the moderate value of 4.00 GPa. This pattern suggests that Split-P structures offer the highest resistance to deformation under elastic loading, whereas Gyroid structures are the most compliant.

Figure 4.

Comparative bar plots of the average mechanical properties; (a) Ave.E, (b) Ave.Y, (c) Ave.U, (d) Ave.PL, and (e) Ave.EA; for Diamond, Gyroid, and Split-P latticesf.

The average yield stress, at which permanent deformation begins, is also the highest for the Split-P lattice (128.77 MPa). The Diamond lattice follows with a moderate value of 95.41 MPa, while the Gyroid lattice ranks the lowest with 65.11 MPa. A similar trend is observed for average U, with Split-P reaching 189.47 MPa, Diamond showing 131.82 MPa, and Gyroid, again, the lowest value of 84.75 MPa. Plateau stress, which measures the sustained stress beyond yielding, further reinforces this trend. The Split-P lattice maintains the highest PL at 171.73 MPa, followed by the Diamond lattice at 110.20 MPa and the Gyroid lattice at 73.60 MPa. This suggests that Split-P structures can sustain higher loads even after initial yielding, making them highly suitable for load-bearing applications. EA, which is a critical property for impact-resistant applications, follows the same pattern. The Split-P lattice absorbs the most energy at 84.22 MJ, making it highly effective in applications requiring high energy dissipation. The Diamond lattice exhibits a moderate average EA of 55.56 MJ, whereas the Gyroid lattice, at 37.38 MJ, has the least EA capacity.

4.2. Comparative Analysis of Mechanical Properties in All Lattice Designs

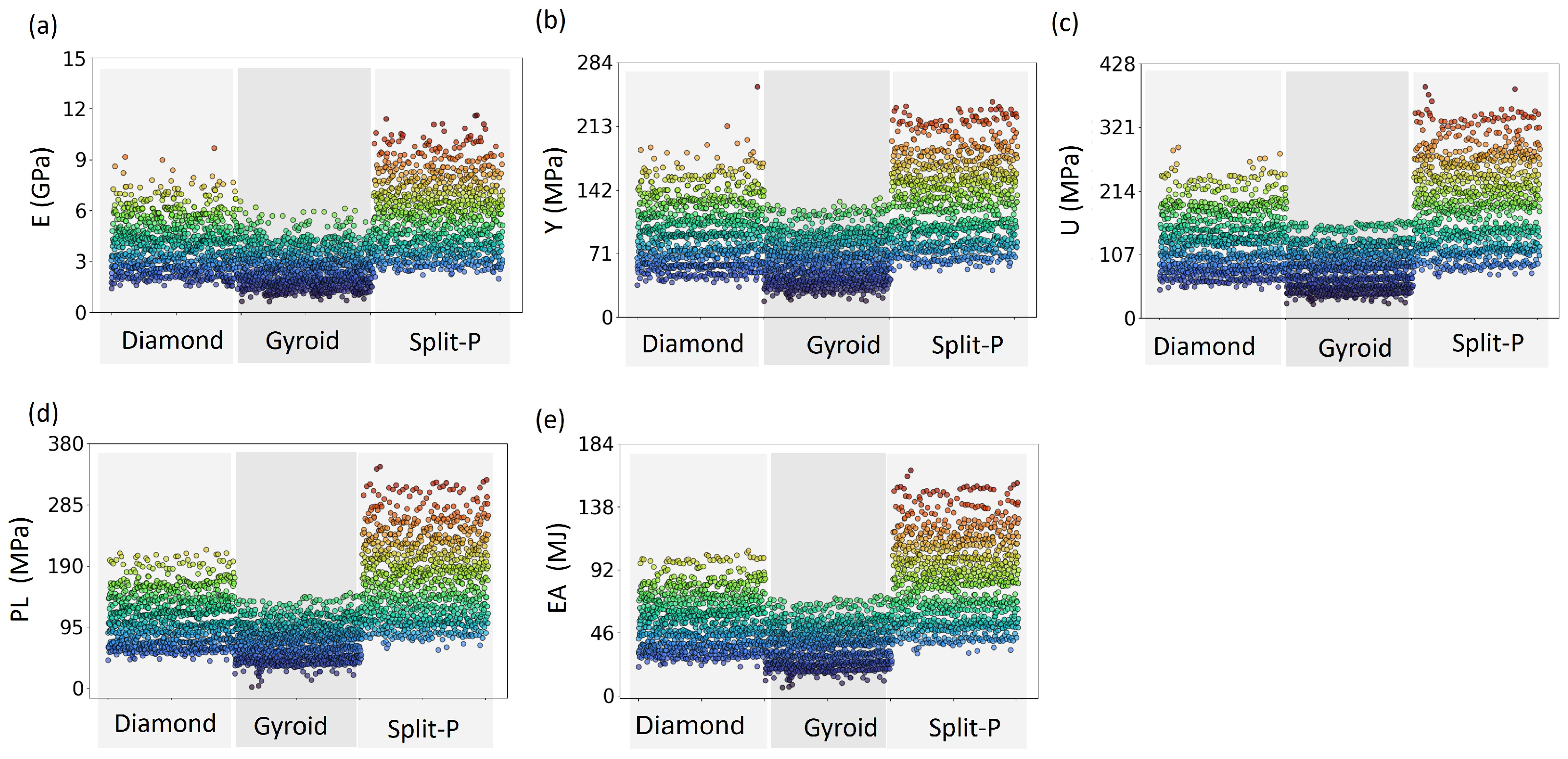

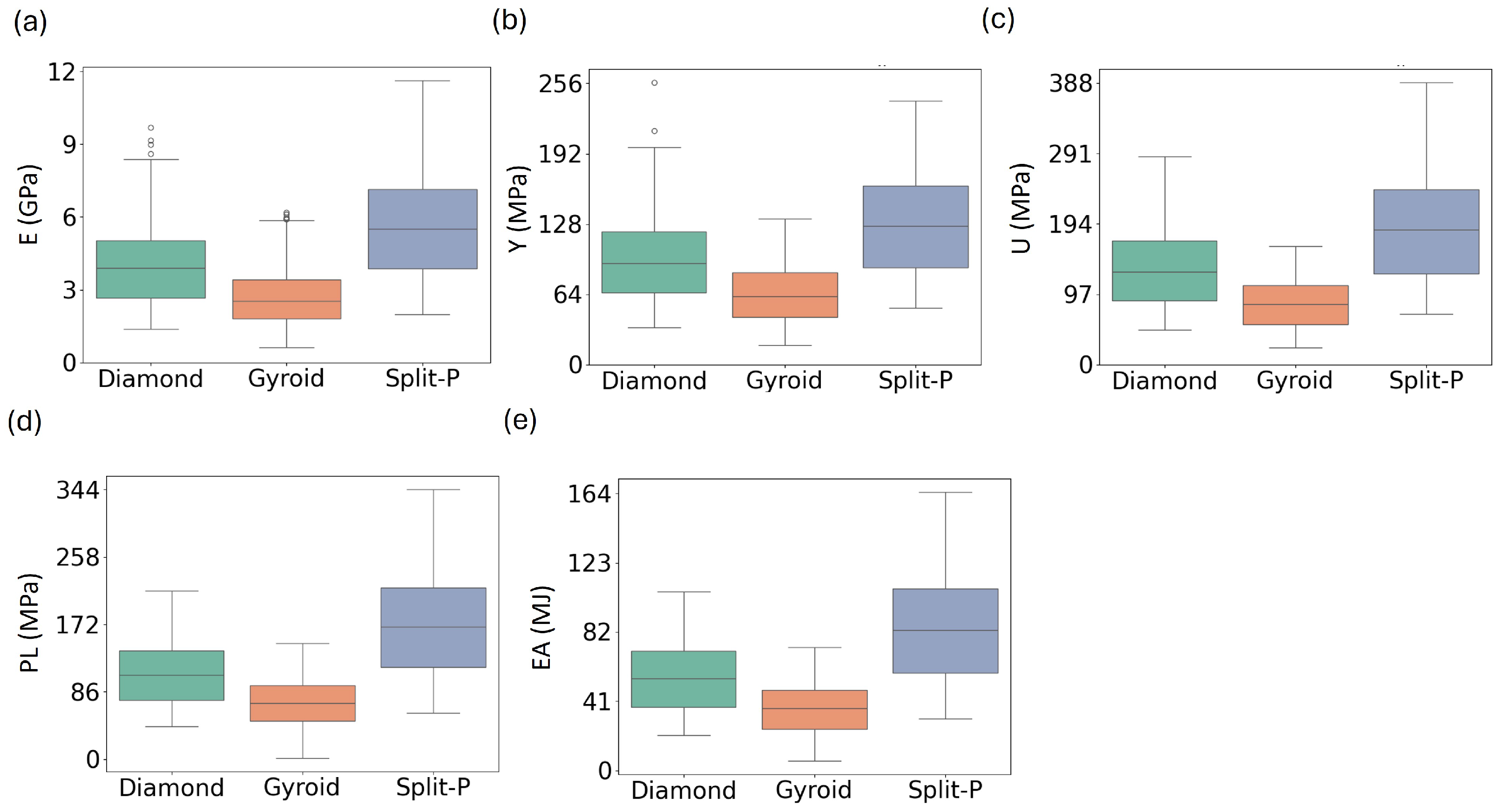

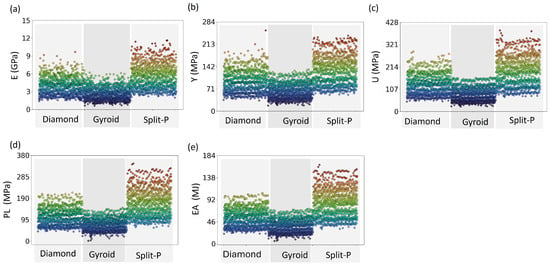

Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of mechanical properties among all 3024 lattices, demonstrating that Split-P lattices exhibited the highest stiffness, with values reaching up to 11.61 GPa. Diamond and Gyroid lattices exhibit lower values of 9.67 and 6.18 GPa, respectively. The Gyroid lattices display the lowest stiffness, reinforcing their flexibility and compliance in structural applications.

Figure 5.

Scatter plots of 3024 lattice designs displaying the distribution of mechanical properties; (a) Ave.E, (b) Ave.Y, (c) Ave.U, (d) Ave.PL, and (e) Ave.EA; across the three lattice types (Diamond, Gyroid, and Split-P). The color gradient represents the range of values, with noticeable clustering patterns indicating the performance variability among different lattice structures.

For Y, the Split-P lattices dominate with higher values, peaking around 240.12 MPa. In contrast, Diamond lattices maintain a moderate range, and Gyroid lattices consistently exhibit lower yield strengths of 231.03 and 132.70, respectively. This pattern continues for U, with Split-P lattices reaching up to 388.72 MPa, while Diamond lattices follow at a lower range, and Gyroid lattices remain at the lowest end. The variation in the data indicates that while some Diamond and Gyroid lattices perform comparably to Split-P designs, they are less consistent in achieving higher mechanical strength. PL and EA further affirm the superiority of Split-P lattices, with the highest data points clustering in the upper ranges with maximum values of 343.98 and 164.62 MPa, respectively. The wider variation observed in the mechanical response of Split-P and Diamond lattices suggests more inconsistency, with Split-P showing the most variability, followed by Diamond. In contrast, the Gyroid lattices are grouped closely together at the lower end of the performance spectrum, indicating their limited ability to withstand high loads after yielding, compared to both Split-P and Diamond.

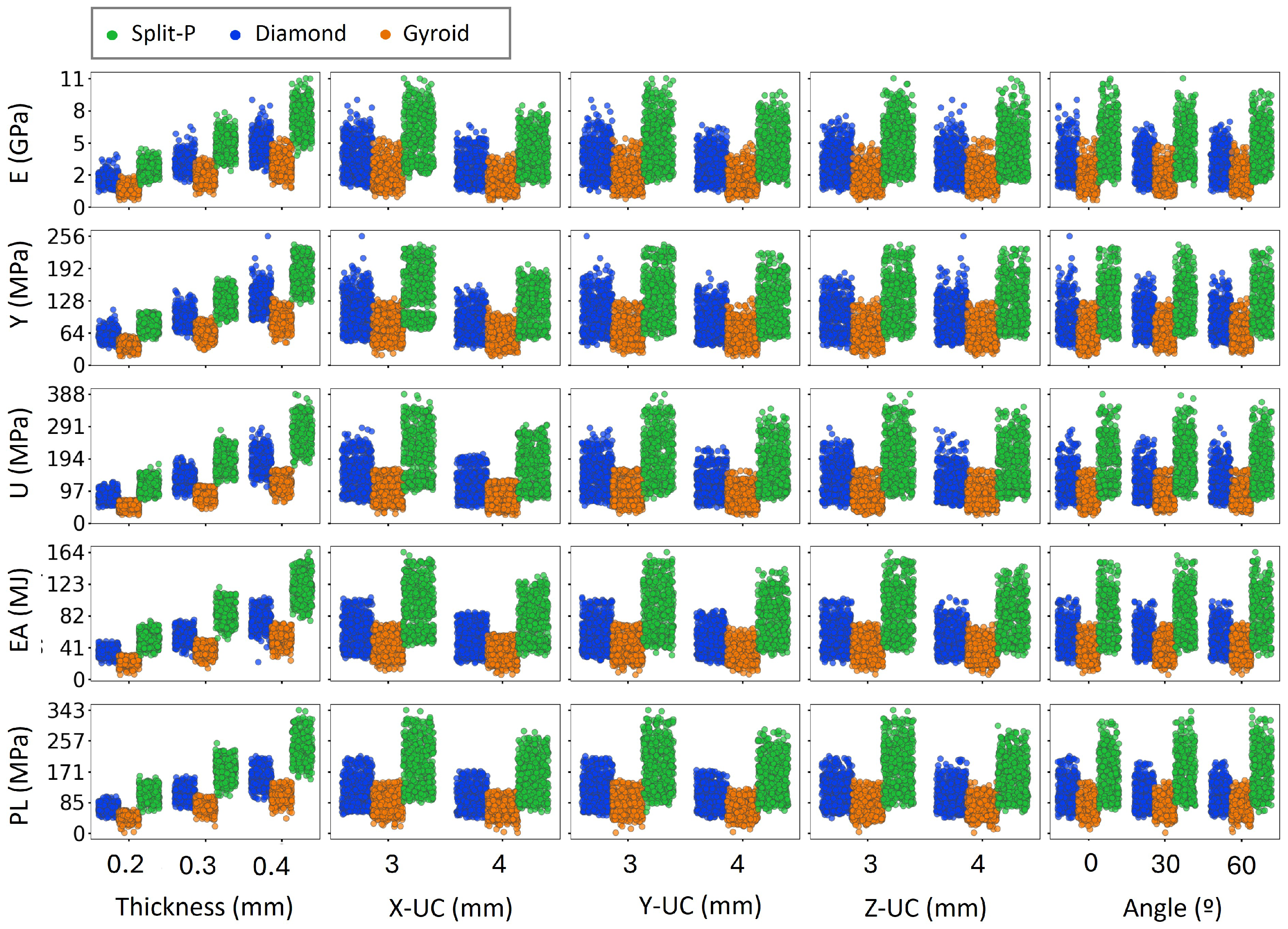

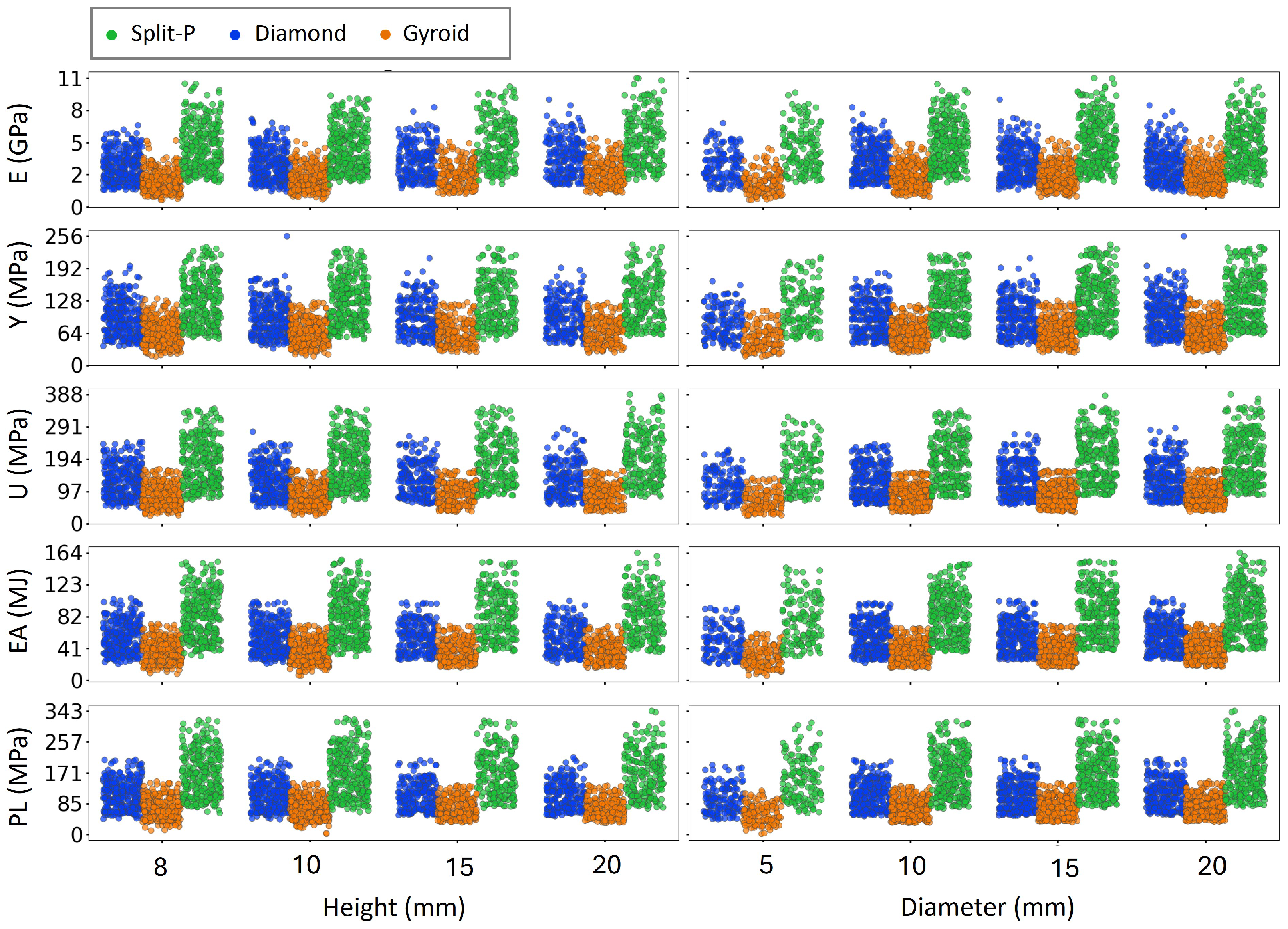

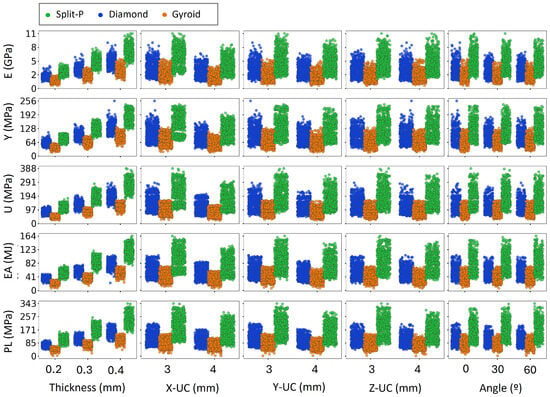

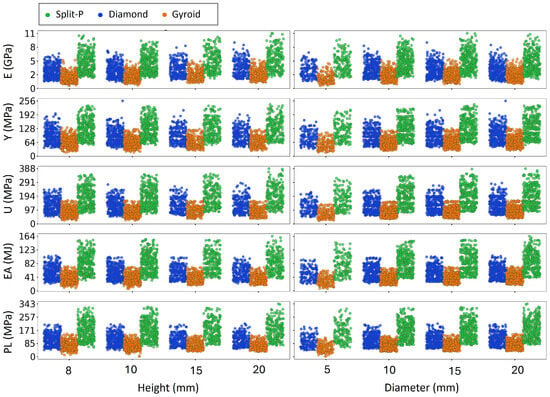

4.3. Influence of Structural Design Parameters on the Mechanical Properties

The scatter plots presented in Figure 6 and Figure 7 depict the variation of key mechanical properties as functions of various geometrical parameters, including T, X-UC, Y-UC, Z-UC, , H, and D, separately. The analysis revealed distinct trends across all design parameters. As expected, increasing thickness consistently leads to higher values in all mechanical properties, indicating that thicker lattice structures exhibit greater stiffness and strength. Similarly, more unit cell numbers generally enhance mechanical performance, particularly for E, U, and PL, suggesting that increasing the number of unit cells results in a more load-bearing structure. The rotation angle (0°, 30°, and 60°) moderately affects mechanical properties, with a slight increase in stress values for higher angles. This is likely due to structural reconfiguration, which enhances the efficiency of load distribution. Moreover, increased H and D result in more scattered mechanical properties, implying variations in structural stability and EA capacity.

Figure 6.

Influence of structural design parameters on mechanical properties as a function of thickness, unit cell size, and angle.

Figure 7.

Influence of structural design parameters on mechanical properties as a function of height and diameter.

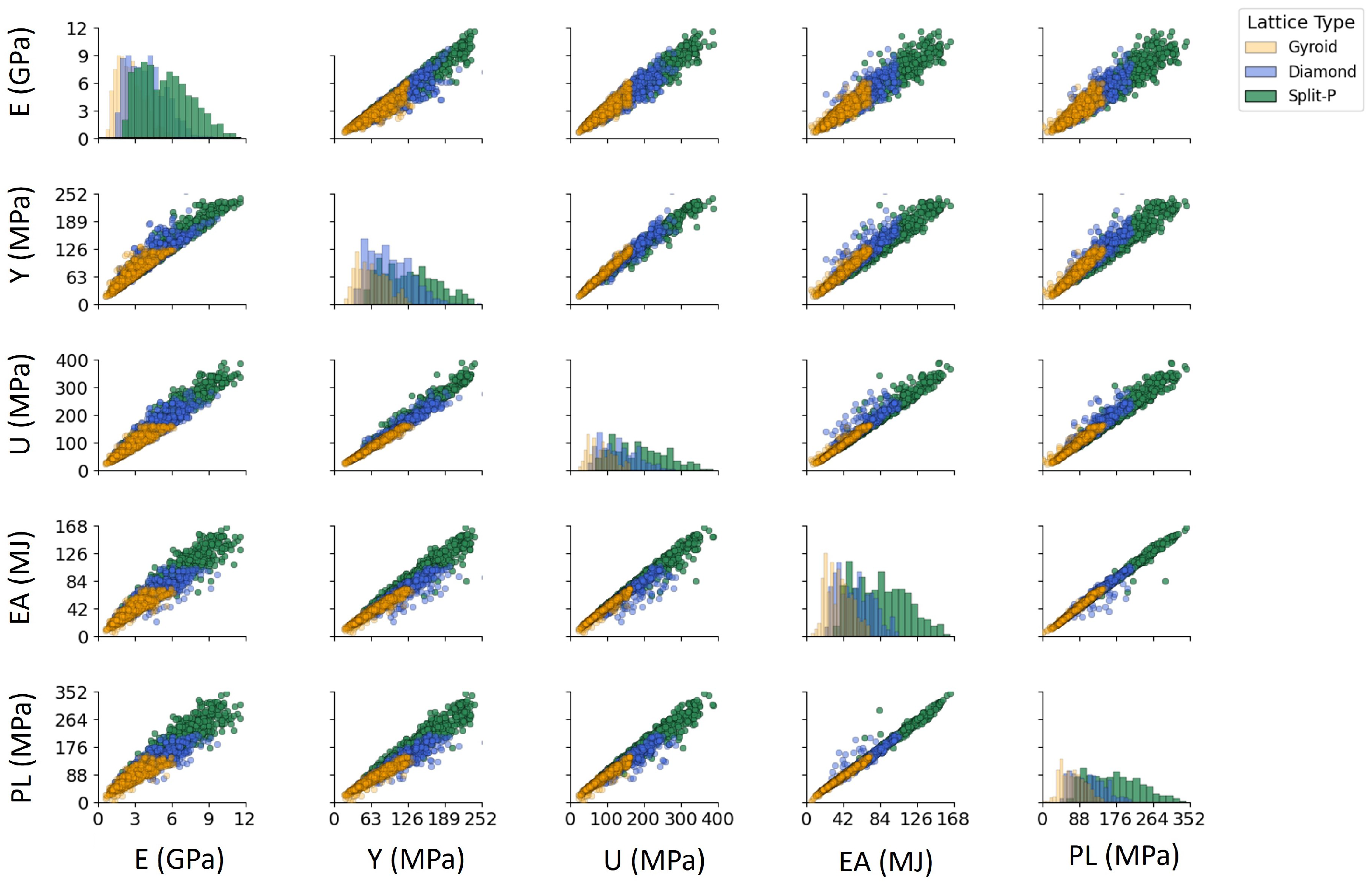

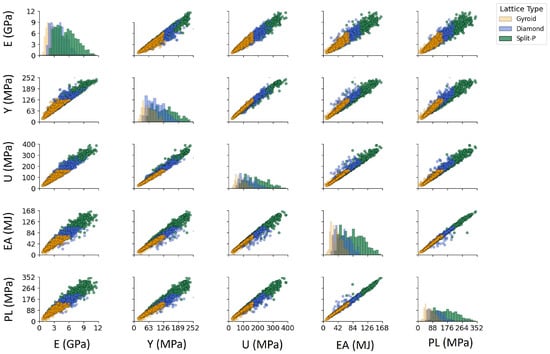

4.4. Pairwise Correlation of Mechanical Properties

The scatter plot matrix in Figure 8 presents pairwise relationships between key mechanical properties. Each scatter plot in the lower-triangular portion of the matrix visualizes the correlation between two properties. In contrast, the diagonal plots illustrate the distribution of each mechanical property across lattice structures. The high correlation between Y, U, EA, and PL is visible from the strong linear relationships observed in their respective scatter plots. Meanwhile, E shows a relatively weaker correlation with other properties, indicating its dependence on structural parameters rather than direct mechanical failure criteria. The distributions along the diagonal plots confirm that Gyroid lattices tend to have lower values across all mechanical properties, whereas Split-P lattices exhibit broader distributions with higher peak values.

Figure 8.

Symmetric pairwise correlation scatter plot of mechanical properties for different lattice structures. The lower/upper triangular scatter plots show pairwise relationships, while the diagonal plots present the distribution of each property.

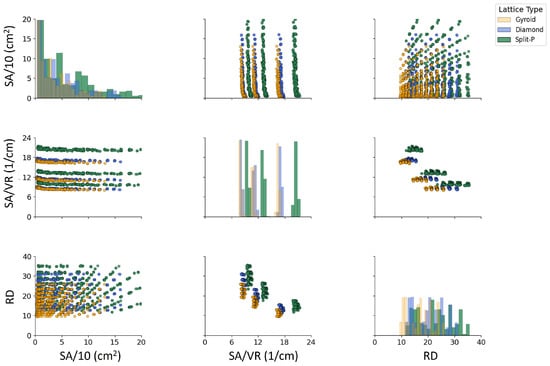

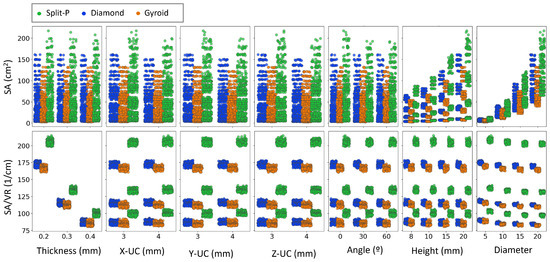

4.5. Influence of Design Parameters on Geometrical Features

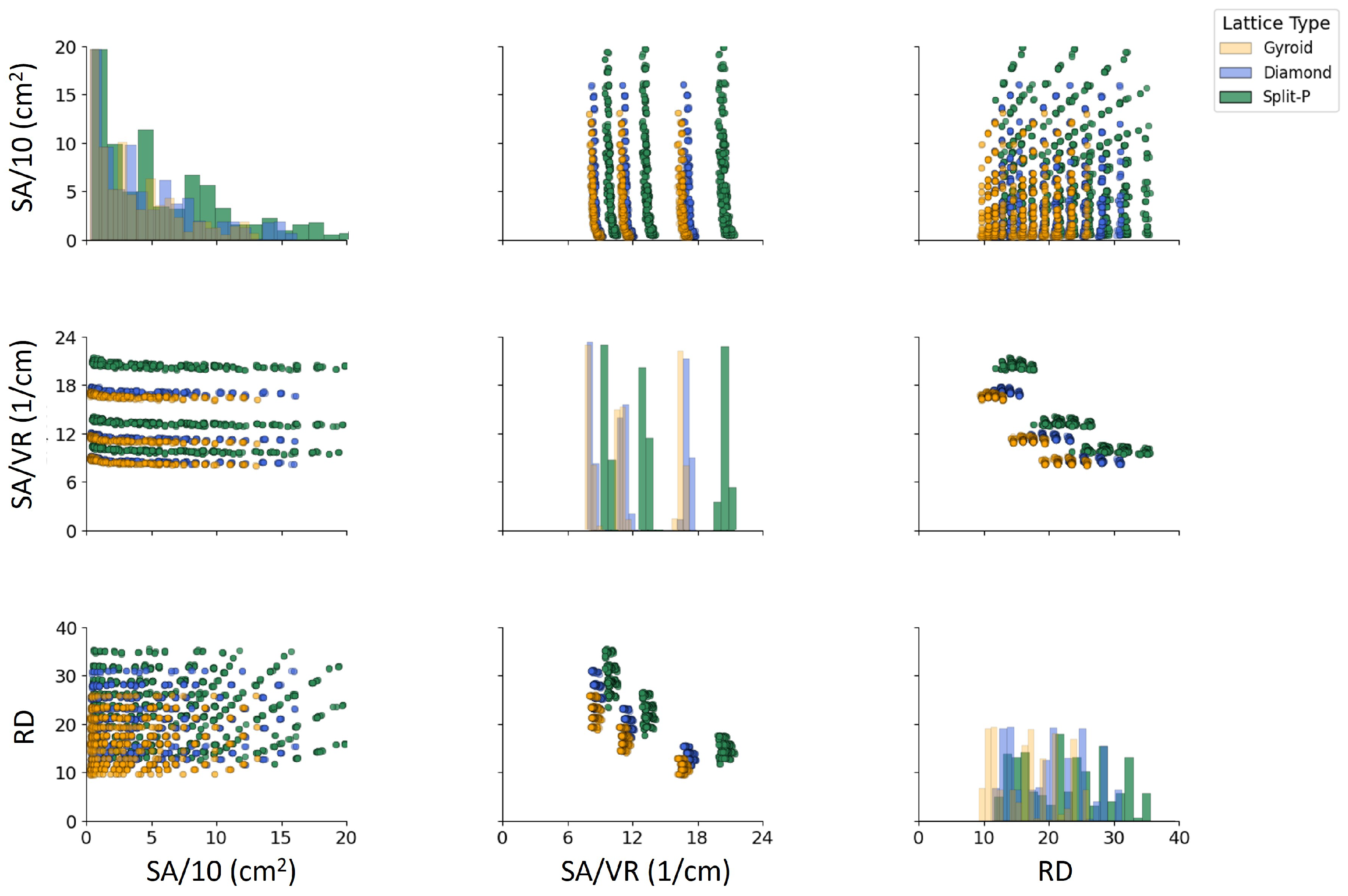

The scatter plots in Figure 9 represent the variations in SA, SA/VR, and RD across different lattice types. A clear distinction is observed among the Diamond, Gyroid, and Split-P structures. The Split-P lattices exhibit the highest SA values, followed by Gyroid and Diamond. The SA/VR values show a systematic pattern, where Split-P exhibits the most significant variations. The RD also follows an increasing trend with SA and SA/VR, confirming the interdependence between these geometrical properties. Notably, Gyroid lattices tend to have lower SA but maintain a high SA/VR, indicating a more intricate internal structure with a greater proportion of void space. The distribution of RD suggests a direct relationship with SA and SA/VR, where higher SA corresponds to an increase in RD.

Figure 9.

Pairwise comparison of geometrical features of lattice structures. The diagonal plots represent the distribution of each property using kernel density estimation (KDE), while the scatter plots illustrate the correlations between these geometrical properties.

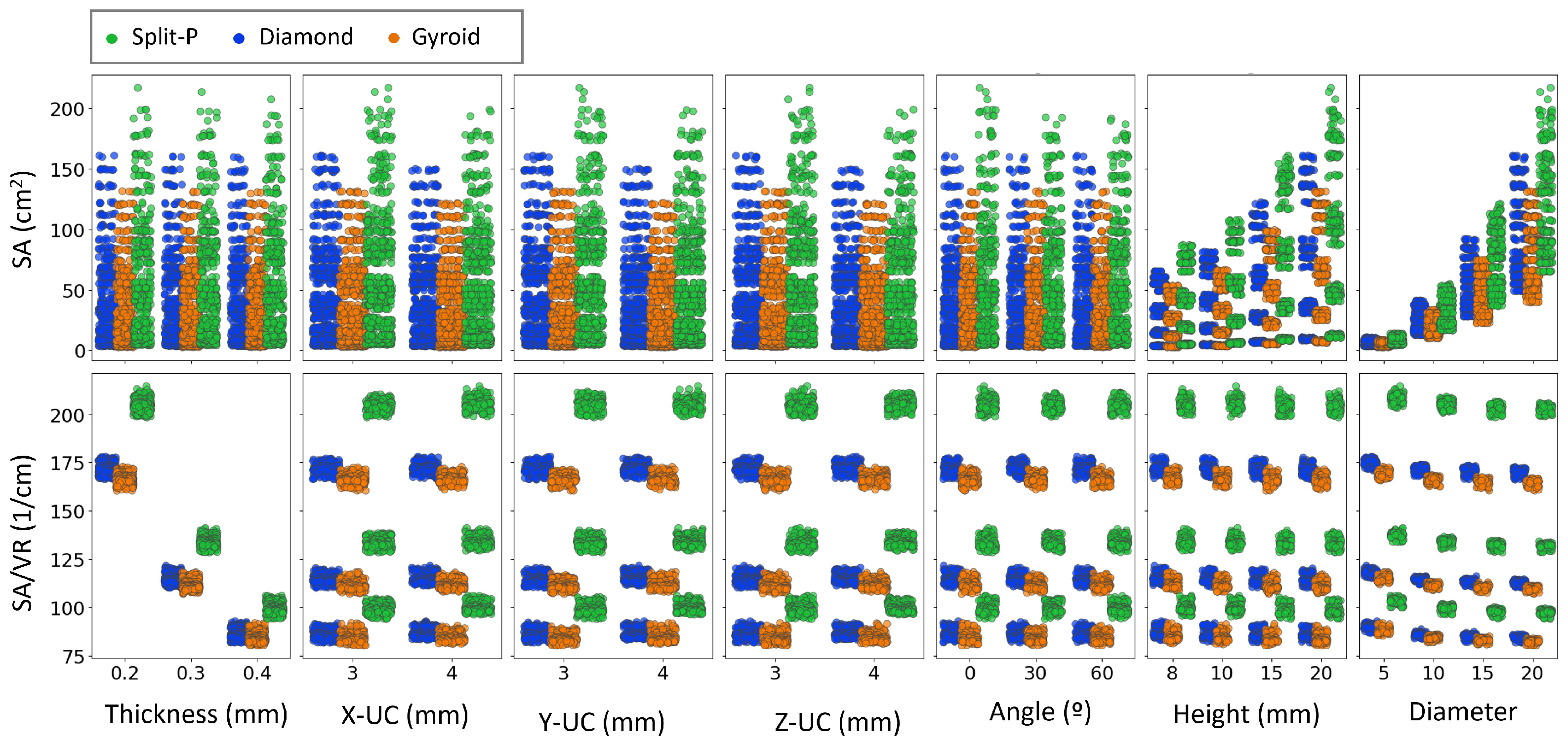

Figure 10 compares SA and SA/VR with the seven design parameters for the three TPMS lattices. Within each lattice type, shell thickness has a pronounced effect on SA/VR; for Split-P, Diamond, and Gyroid, the three thickness levels form clearly separated SA/VR bands, indicating a strong sensitivity of SA/VR to thickness at fixed unit cell counts and implant size. By contrast, the absolute SA is mainly governed by diameter, height, and the number of unit cells. The point clouds at various thickness levels significantly overlap in SA, showing no clear trend of SA with thickness. Thus, thickness is an important design lever for tuning SA/VR (and thereby surface exposure per unit volume).

Figure 10.

Scatter plots showing the relationship between SA and SA/VR against key design parameters, including thickness, Y-UC, Y-UC, Y-UC, angle, height, and diameter. Data points are color-coded based on the lattice type.

For X-UC, Y-UC, and Z-UC, the SA values remain relatively clustered, with only minor variations observed between different lattice types. However, a distinct trend is seen in SA/VR, where Split-P lattices maintain consistently higher values, suggesting that their geometry retains more surface exposure regardless of unit cell parameters. The effect of angle and height on SA is less pronounced, though a slight increase in SA is observed at higher values of height. SA/VR values for Gyroid and Diamond lattices show a more stable distribution across these parameters, while Split-P lattices exhibit more significant fluctuations.

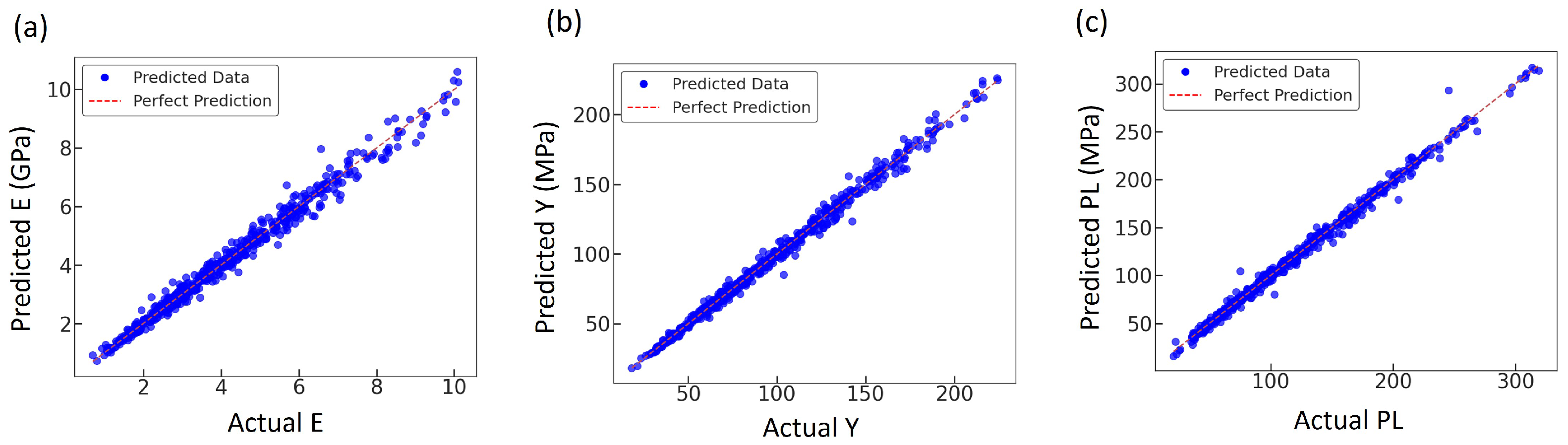

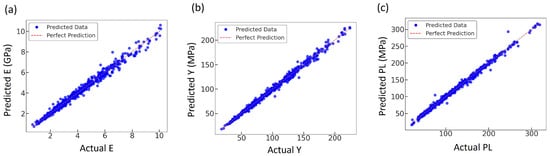

4.6. Prediction of Mechanical Properties Using ANN

Prediction quality was examined by comparing the ANN outputs with the FEA results for each mechanical property. Figure 11a–c show scatter plots of predicted versus simulated values for E, Y, U, EA, and PL. In all three cases, the data points are tightly clustered along the diagonal perfect-prediction line, indicating an almost one-to-one correspondence between the ANN predictions and the FE results, and confirming that the network accurately reproduces the variability of the mechanical response across the design space. The corresponding scatter plots for U and EA have been reported in our previous study [36] and are therefore not repeated here.

Figure 11.

Comparison of actual and predicted mechanical properties; (a) E, (b) Y, and (c) PL; using the trained ANN model.

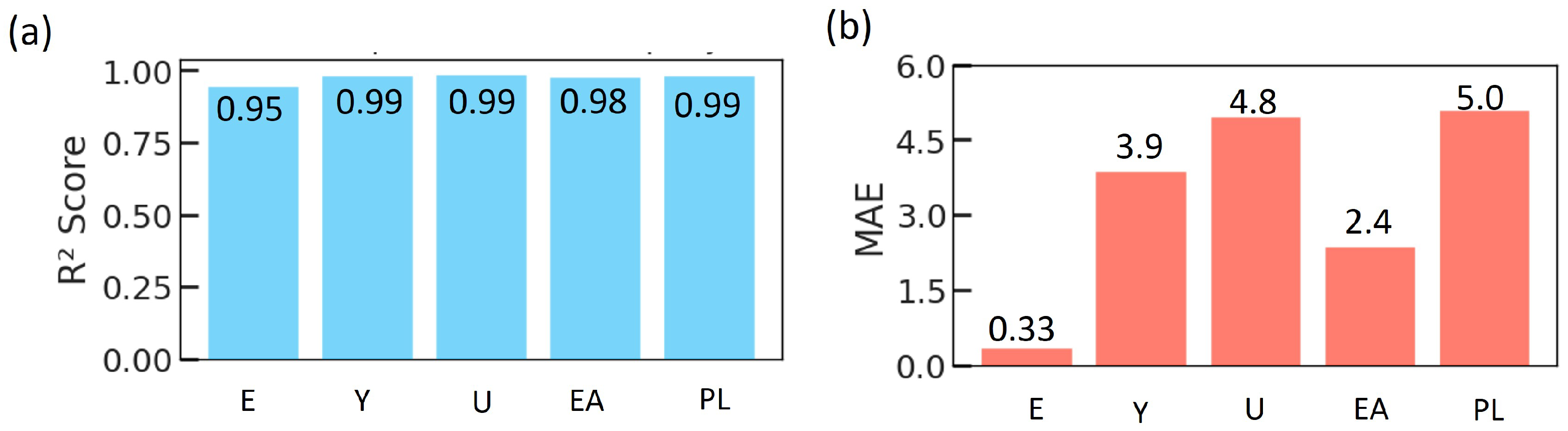

In assessing the predictive performance of classical ML models (RFR and XGBR) for the mechanical response, these models were first employed as baselines. We considered a linear regressor and two tree-based ensemble methods (FRF and XGBR). Linear regression provided only moderate accuracy, with a global MAE of 19.87 and a global coefficient of determination of 0.64. Adding nonlinear interactions through ensembles markedly improved performance: the random forest regressor reduced the global MAE to 2.52 and increased to 0.98, while XGBR achieved the best aggregate scores, with a global MAE of 1.95 and of 0.99. These results indicate that the mapping from design parameters to mechanical response is highly nonlinear but can be captured effectively by sufficiently flexible models. A feed-forward ANN was also designed and tailored to the present dataset with a global of 0.97 and MAE of 3.16. The model takes the lattice design parameters as inputs and simultaneously predicts five mechanical properties. The ANN architecture and training hyperparameters are summarized in Table 2; in brief, the network is a fully connected multi-output regressor with several hidden layers using ReLU activation and a five-neuron linear output layer. The model was trained with the Adam optimizer using MSE as the loss function and MAE as an additional performance metric, with an 80/20 train–test split and internal validation.

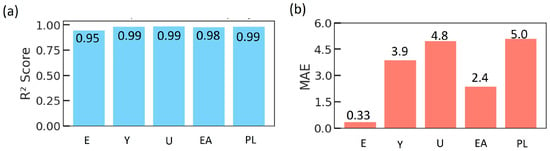

The predictive quality of the ANN is represented in Figure 12 for each mechanical property. All five outputs exhibit high coefficients of determination, with consistently above 0.95, indicating that the ANN explains nearly all of the variance in the simulated data for each property. The corresponding MAE values remain below 6 in their respective units. Given the range of mechanical properties, the MAE values correspond to percentage errors typically in the single digits to low double digits. This level of accuracy is sufficient for rapid evaluation and prioritization of potential TPMS implant designs.

Figure 12.

Comparison of surrogate models used to predict the mechanical properties of TPMS lattices. (a) Corresponding coefficient of determination () values for the same properties and models, and (b) MAE for each mechanical property obtained with RF, XGBR, and ANN.

At the global level, the ANN achieves an MAE of 3.16 and a global of 0.97, slightly below the best tree-based ensemble (XGBR) but still within a few percentage points of the optimum. We nonetheless adopt the ANN as our primary surrogate model for the subsequent optimization and design analyses for several reasons. First, in our implementation, the tree-based models are trained separately for each target property, whereas the ANN is a single multi-output network that jointly learns the correlations between E, Y, U, EA, and PL, leading to more self-consistent predictions across outputs during design optimization. Second, the ANN provides a smooth, differentiable approximation of the mechanical response surface, and finally, the performance gap between the ANN and the best ensemble model is small in absolute terms (all models reach > 0.97), indicating that the ANN offers a favorable compromise among accuracy, model compactness, and compatibility with our broader optimization framework.

4.7. Predicted Mechanical Properties—Case Studies

To demonstrate the practical utility of the trained ANN model, predictions were generated for three distinct TPMS lattice configurations characterized by different categorical and geometrical design parameters. Table 3 presents the input features along with the corresponding predicted mechanical properties, including E, Y, U, EA, and PL. The outputs suggest a consistent increase in all mechanical responses with increasing unit cell size and thickness, reflecting the expected behavior based on lattice densification.

Table 3.

Predicted mechanical properties for selected TPMS lattice configurations. All lengths are in mm, and the angle is in degrees. Outputs: E (GPa); Y, U, and PL (MPa); and EA (MJ).

5. Discussion

5.1. Application-Oriented Interpretation of Lattice Mechanical Performance

Figure 4 and Figure 5 together summarize how the three TPMS architectures distribute their mechanical response across the design space. On average, Split-P lattices consistently exhibit the highest values of all measured mechanical properties, making them the most robust and load-resistant structures. Their superior stiffness, yield strength, ultimate strength, and energy absorption suggest that they are well suited for situations where high mechanical integrity is critical, such as structural supports or bone scaffolds with demanding load-bearing requirements [45,46]. At the same time, this increased stiffness may be a limitation in cases where flexibility or controlled deformation is desired [47]. The scatter plots in Figure 5 further show that this dominance is maintained across a wide range of geometrical configurations, underlining the robustness of Split-P designs for load-bearing and energy-absorbing applications, including impact-resistant and high-strength structures [48,49].

Diamond lattices provide a more balanced response, offering an intermediate compromise between strength and compliance. With moderate values across all mechanical properties, they emerge as versatile candidates for implants and other components that must combine sufficient load-bearing capacity with some adaptability to surrounding tissues [50]. The wide spread of Diamond data points in Figure 5 indicates a wider tunability range, suggesting that Diamond architectures can be customized through parameter optimization to target specific combinations of stiffness, strength, and flexibility [51,52].

Gyroid lattices, while the weakest in terms of absolute strength, are the most compliant of the three. This enhanced flexibility can be advantageous where mechanical conformity is important, for example in biomedical scaffolds that must better match the behavior of natural bone or in mechanically adaptive structures [53,54]. The clustering of Gyroid data at lower mechanical property values suggests that additional geometric tailoring or hybrid designs may be required to meet more demanding load-bearing applications [20]. Overall, these findings highlight that the choice of lattice architecture should be guided by the target application: Split-P for high-strength and energy-absorbing roles [15,48], Diamond as a tunable intermediate option balancing mechanical efficiency and manufacturability [51,52], and Gyroid where mechanical compliance and conformability are prioritized [55].

5.2. Distribution Analysis of Mechanical Properties Across Lattice Types

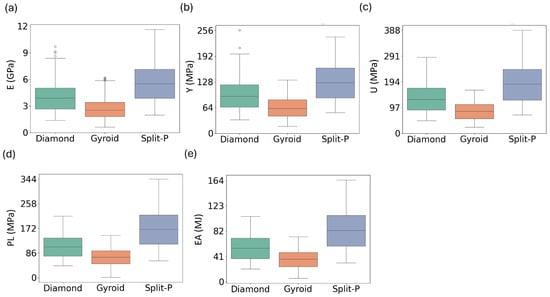

The distribution of mechanical properties for the three lattice types provides additional insight into their structural behavior and variability. As illustrated in Figure 13, the Split-P lattices consistently exhibit the highest median values and the widest spread across all properties, with the largest interquartile ranges and upper whiskers in E, Y, U, EA, and PL [56,57]. This confirms their superior load-bearing and energy-absorbing capacity but also indicates a stronger sensitivity to design parameters, which may require more careful tuning when highly repeatable performance is needed.

Figure 13.

Distribution of mechanical properties across lattice types, illustrating the spread and variability of (a) Ave.E, (b) Ave.Y, (c) Ave.U, (d) Ave.PL, and (e) Ave.EA for the Diamond, Gyroid, and Split-P lattices.

The Diamond lattices show median values that lie between those of Split-P and Gyroid for most properties, together with a moderate spread. This suggests a more balanced combination of strength and variability; they do not reach the extreme values of Split-P, but their distributions are less dispersed, particularly for Y and PL, where they maintain relatively stable load-bearing and post-yield behavior. In contrast, the Gyroid lattices display the lowest medians and the narrowest distributions, with tight clustering of E, Y, and U around lower values. This also indicates a more uniform, compliant mechanical response with fewer extreme outliers.

Overall, Figure 13 highlights a trade-off between peak performance and consistency across the three architectures: Split-P offers the highest attainable mechanical properties at the cost of larger variability, Diamond occupies an intermediate regime with balanced strength and dispersion, and Gyroid provides the most uniform but least stiff response. These distribution-level observations complement the mean trends and application-oriented interpretations discussed in the previous subsection.

5.3. Trends and Impact of Structural Parameters Adjustments on the Mechanical Properties

In Figure 6, the increasing trends observed in E, Y, and U with thickness indicate that increasing the material volume and connectivity within the lattice enhances its overall mechanical strength. Thicker lattices exhibit higher stiffness, leading to greater mechanical properties values, making them more suitable for load-bearing applications [58]. In contrast, when increasing X-UC, Y-UC, and Z-UC, a decline in mechanical properties can be observed [59]. However, mechanical properties do not always increase with these parameters, as specific configurations may lead to premature failure or stress localization. Uniform behavior of the angle indicates that the lattice orientation has little effect in mechanical performance [60].

Figure 7 shows that height and diameter influence the mechanical properties much more strongly for Diamond and Split-P lattices than for Gyroids. For Split-P and Diamond, increasing height from 8 to 20 mm clearly shifts the point clouds of E, Y, U, EA, and PL to higher levels and also widens their spread, indicating not only higher average stiffness and strength but also a wider tunable range of responses. A similar effect is observed when increasing the diameter from 5 to 20 mm: all mechanical properties rise noticeably for Split-P and Diamond, with denser clusters at higher values and larger variability. In contrast, the Gyroid lattices show only modest changes in both height and diameter; their mechanical properties increase only slightly and the overall cloud remains relatively compact, so the trends are less visually pronounced. This suggests that global dimensions (height and diameter) are powerful design levers for strengthening and tailoring Split-P and Diamond lattices, whereas Gyroid behavior is dominated more by its intrinsic topology than by these global size changes.

5.4. Mechanical Properties Correlation

The pairwise correlation patterns in Figure 8 provide several insights that go beyond the direct numerical comparison of mechanical properties. Initially, the nearly collinear relationships observed among Y, U, PL, and EA suggest that a shared underlying mechanism mainly controls these strength-related variables [61,62]. Once the lattice architecture and relative density fix the onset of yielding, the subsequent hardening response and energy absorption capacity follow in a reasonably predictable way. From a design perspective, this means that optimizing Y is effectively equivalent to co-optimizing U, PL, and EA within the current design space, thereby considerably reducing the dimensionality of the optimization problem and simplifying surrogate modeling.

In contrast, E occupies a more independent role. Its comparatively weaker and more scattered correlation with the strength metrics suggests that stiffness can be tuned somewhat separately from failure-related properties [63,64]. This decoupling is particularly important for bone-mimetic applications, where matching the elastic response of host tissue (to mitigate stress shielding) is often more critical than maximizing strength alone. The ability to adjust E without proportionally increasing Y, U, or PL opens opportunities for lattices that are compliant enough to promote physiological load transfer while still maintaining adequate safety margins against failure [65].

The diagonal distributions and the clustering observed in the scatter plots also highlight a clear separation between lattice topologies. Gyroid structures occupy the low-stiffness, low-strength regime with relatively compact distributions, consistent with their role as mechanically compliant architectures. Diamond lattices populate an intermediate region, providing a broad spectrum of trade-offs between stiffness and strength. Split-P lattices dominate the upper ranges of all properties and show the widest spread, reflecting both their superior load-bearing capacity and their sensitivity to design parameters. This stratification confirms that topology choice is a primary lever for navigating the global performance space, while fine-tuning of geometric parameters (thickness, unit cell counts, height, diameter) provides local control within each family.

Ultimately, the pairwise correlations highlight that TPMS lattices do not cover the mechanical space in a random manner; rather, they fill structured manifolds influenced by both topology and geometry. Recognizing these relationships is essential for rational design; it clarifies which properties can be improved together, which are constrained by shared mechanisms, and where real independence exists for tailoring stiffness and strength to the requirements of specific implant or structural applications.

5.5. Geometrical Properties Correlations

Figure 9 shows that the three geometrical descriptors (SA, SA/VR, and RD) are strongly coupled, but in a topology-dependent manner. Split-P lattices populate the upper range of both SA and RD, confirming that this architecture naturally generates highly textured, material-rich structures, whereas Gyroid lattices cluster at lower RD and moderate SA, and Diamond occupies an intermediate region. This division indicates that the selection of TPMS topology inherently determines a design choice; Split-P for compact, intricately organized structures, Gyroid for lighter and more flexible frameworks, and Diamond as a moderately balanced option [66,67]. In biomedical applications, where both mechanical support and surface-mediated biological interactions are critical, such topological tuning is particularly valuable [68].

The SA/VR–RD scatter plot highlights a clear relation between surface exposure and density. Across all three TPMS families, higher SA/VR values are generally associated with lower RD, indicating that very surface-rich architectures tend to be more porous. This trend is especially evident for Gyroid and Split-P lattices and is consistent with observations that high SA/VR promotes cell attachment, nutrient transport, and osseointegration [69,70], while excessive density can hinder mass transport [71]. Split-P designs are distinguished by their ability to form clusters that achieve both high sSA and high RD simultaneously. This characteristic maximizes the interfacial area and increasing stiffness. While this makes them attractive for robust, load-bearing implants, they may not be suitable for areas where mechanical compatibility with bone is essential [72,73].

5.6. Design Parameters Influence on Geometrical Features

The trends in Figure 10 highlight that different design variables control different aspects of the surface architecture. Within each lattice family, the three thickness levels form clearly separated SA/VR bands, whereas the corresponding SA clouds have a strong overlap. This means that adding material by thickening the shell increases volume faster than surface, thereby reducing SA/VR, even though the absolute SA changes only modestly. From a design point of view, this behavior is consistent with earlier observations that thicker struts improve load-bearing capacity at the expense of surface exposure [74]. It also confirms that thickness should be adjusted with notice in applications where high SA/VR is critical, such as bone scaffolds or compact heat exchangers, where efficient use of material and short diffusion paths are required [75].

For all three TPMS families, SA grows markedly with increasing diameter and height, while SA/VR stays more uniform. This implies that once a suitable SA/VR band has been chosen via thickness, implant size can be increased to boost absolute SA without drastically altering surface efficiency. Such a two-step strategy is attractive for biomedical devices, where one may first select a lattice type and thickness to achieve a target SA/VR and porosity, and then use diameter and height to match anatomical constraints and required contact area [15]. The Split-P topology consistently occupies the upper SA and SA/VR ranges, confirming its potential when maximizing surface interaction and mechanical anchorage is desired, whereas Gyroid remains more conservative and less sensitive to scaling in several parameters, which can be beneficial when stable, predictable surface characteristics are preferred.

In summary, the closely grouped SA values for X-UC, Y-UC, and Z-UC, together with the notable changes observed in SA/VR, suggest that the redistribution of unit cells impacts how the surface is organized within the available volume instead of simply increasing the surface area. This supports the idea that the internal connections and curvature are at least as significant as the overall size in influencing surface efficiency. In conclusion, Figure 10 illustrates a hierarchical design strategy where the lattice type establishes the initial SA/VR framework, thickness enhances surface efficiency, and overall dimensions (such as diameter, height, and unit cell counts) are subsequently utilized to adjust the design according to the functional and anatomical needs of the intended application [15,74,75].

5.7. ANN Surrogate Performance and Design Implications

The study using surrogate models reveals that the TPMS design space behaves in a smoothly varying way. After accounting for nonlinear dependencies, all three data-based models can accurately reproduce the responses obtained from FEA. In this context, the main role of the classical regressors (RF and XGBR) is to demonstrate that relatively simple, local partitioning of the feature space is already sufficient to approximate the underlying mechanics. The ANN is chosen as the working surrogate not due to a significant improvement in numerical accuracy but because it provides a compact, multi-output representation. This approach treats the five mechanical properties as a coupled system instead of viewing them as independent targets. The present results indicate that a single neural network can act as a readable mechanical response operator for TPMS lattices, which is particularly advantageous for downstream tasks such as multi-objective optimization, inverse design, and sensitivity analysis within a unified framework.

The scatter plots in Figure 11 (when considered alongside with Figure 12) reinforce this interpretation. For E, Y, and PL, the predicted values follow the 1:1 line over the full range, with only a modest spread at the extremes. Together with the smooth, closely aligned training and validation loss curves, this suggests that the ANN captures the dominant trends in the data without severe overfitting. The property-related performance is also physically meaningful; E exhibits the smallest absolute error, consistent with its smoother dependence on relative density and unit cell morphology, whereas U and PL show larger errors, reflecting the higher sensitivity of post-yield response to local failure modes and mesh-level details that are not explicitly encoded in the input features. These observations are in line with previous studies where ANNs were able to reproduce global stiffness more accurately than failure quantities or full stress–strain curves for porous and trabecular structures [31,33,76].

In comparison with earlier ANN applications in bone mechanics and scaffold design [31,33,36,76], the present network operates on a relatively compact input space (seven design parameters) but still achieves similar levels of predictive accuracy. This suggests that much of the relevant information for quasi-static compression can be captured by global descriptors such as thickness, unit cell counts, and implant dimensions, without the need to explicitly encode voxelized geometries or local stress features. At the same time, the moderate values highlight that part of the variability remains unexplained; additional descriptors related to local curvature, strut connectivity, or manufacturing defects could further reduce prediction errors, especially for U, EA, and PL. Incorporating physics-informed constraints or lattice-type-specific subnetworks is another promising direction to better represent the subtle differences between Gyroid, Diamond, and Split-P architectures.

From a design perspective, the ANN’s accuracy is adequate for quickly evaluating candidate configurations before proceeding to more detailed simulations or experiments. The case studies in Table 3 illustrate how the model can be queried to compare topologies under realistic parameter combinations. The predicted trends are consistent with the understanding represented in Section 4; the Split-P design with thicker walls, larger diameter, and more unit cells attains the highest stiffness, strengths, and energy absorption, while the Diamond and Gyroid examples occupy intermediate and lower ranges, respectively. This indicates that the surrogate model functions not just as a method for interpolating numerical values, but also exhibits behavior that is realistic.

Altogether, the combination of model comparison (Figure 12), prediction scatter plots (Figure 11), and illustrative design queries (Table 3) shows that the proposed ANN offers a practical relationship between accuracy and computational cost. While it cannot replace detailed FEA for final verification, it can substantially reduce the size of the design space that must be explored with expensive simulations. In the context of TPMS-based bone implants, this capability is particularly valuable for multi-objective optimization, where thousands of designs must be evaluated to balance stiffness, strength, energy absorption, and surface-related metrics within clinically relevant ranges [36]. Future work should therefore focus on integrating the ANN into optimization and uncertainty quantification frameworks, as well as validating its predictions against additively manufactured specimens under experimental loading.

6. Conclusions

This study builds on our prior work on forward optimization [36] and presents an AI-based framework for optimizing the mechanical properties of TPMS lattice structures for bone-implant applications. By integrating FEA with ANN, the mechanical behavior of Gyroid, Diamond, and Split-P lattices under quasi-static compression can be accurately modeled and predicted. Among the evaluated lattice types, Split-P structures demonstrated the highest mechanical strength and energy absorption capacity, making them well suited for high-load-bearing applications. Diamond lattices offered a balanced compromise between strength and ductility. In contrast, Gyroid lattices exhibited the highest SA/VR, indicating their suitability for enhanced osseointegration and nutrient transport in biomedical contexts.

The ANN model achieved high predictive performance, with the highest scores exceeding 0.95 and low mean absolute errors across all five target properties. Sample predictions illustrate the model’s capacity to estimate mechanical properties for new TPMS designs, reinforcing its value as a computational screening tool. This predictive capability significantly reduces the need for extensive experimental testing and accelerates the design-to-prototype cycle for patient-specific bone scaffolds.

7. Limitations

While this study offers valuable insights into the AI-based optimization of TPMS lattice structures for bone implants, several limitations should be considered. First, the ANN’s predictive capability relies on the quality and diversity of the training dataset. Since the model was trained on a specific set of lattice geometries and material properties (Ti6Al4V), its applicability to other materials or lattice configurations may require further validation and retraining.

Second, the FEA used in this study operates under idealized boundary conditions, which may not fully capture the complexities of in vivo conditions. Factors such as biological degradation, fatigue loading over time, and the interaction between bone and implant tissues were not explicitly modeled and should be investigated in future work.

Additionally, while TPMS lattices are known for their high manufacturability via additive manufacturing, challenges such as residual stress buildup, surface roughness, and fabrication inconsistencies can impact their mechanical performance. These factors were not explicitly considered in the computational models and may affect the real-world applicability of the designs.

The study primarily focuses on mechanical performance, without direct experimental validation of biological responses such as osseointegration, cell proliferation, or tissue ingrowth. Future work should incorporate in vitro and in vivo experiments to assess how different TPMS lattice structures interact with biological tissues, ensuring that optimized designs meet mechanical and biomedical requirements for successful bone implantation.

Challenges in Inverse Design and Future Work

Although the inverse design approach—predicting lattice geometry from target mechanical properties—is an attractive concept for implant personalization, our analysis revealed several key limitations that currently hinder its reliability. When training inverse ANN models separately for load-bearing (using elastic modulus, yield stress, and ultimate strength as inputs) and energy-absorbing (using energy absorption as input) applications, the resulting values for most geometrical parameters were relatively low, particularly for cell counts (X-UC, Y-UC, Z-UC) and angle. Only thickness demonstrated consistent predictive strength across both categories, while other parameters, such as angle and cell numbers, showed poor or even negative , indicating limited learnability. This outcome is consistent with our earlier sensitivity analysis, which showed that thickness, diameter, and height are the dominant factors influencing the mechanical response. At the same time, the impact of cell distribution and rotation is relatively minor. Moreover, enforcing geometric constraints—such as positivity, manufacturability, and height-to-diameter ratio limits—further complicates inverse prediction and may necessitate hybrid rule-based filtering post-inference.

Given these observations, the current form of the inverse ANN model may not offer the robustness and generalizability required for clinical or design applications. We therefore propose that future research explore constrained generative design models, physics-informed neural networks, or reinforcement learning frameworks to enhance the fidelity of inverse mapping while embedding geometric feasibility natively into the prediction process. Additionally, integrating multi-objective optimization with forward surrogate models may provide a more controlled and interpretable pathway for reverse-engineering implant geometry to achieve targeted functional performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R. and S.S.; methodology, M.R. and S.S.; software, M.R., A.C.D., and M.K.; validation, M.R., A.C.D., and M.K.; formal analysis, M.R.; investigation, M.R.; resources, I.H.; data curation, M.R. and A.C.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.; writing—review and editing, M.R., I.H., and S.S.; visualization, M.R.; supervision, I.H.; project administration, I.H.; funding acquisition, I.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by the Estonian Research Council, Estonia, under Grant PRG643 (I. Hussainova), M-ERA.Net project “BiLaTex” MNHA23020 (I. Hussainova), and PRG3028 (I. Hussainova), and PRG3028 (I. Hussainova).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inguiries can be directed to the correspondingauthor.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Francis, A.P.; Augustus, A.R.; Chandramohan, S.; Bhat, S.A.; Priya, V.V.; Rajagopalan, R. A review on biomaterials-based scaffold: An emerging tool for bone tissue engineering. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 34, 105124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.C.; Alvites, R.; Lopes, B.; Sousa, P.; Moreira, A.; Coelho, A.; Rêma, A.; Biscaia, S.; Cordeiro, R.; Faria, F.; et al. Hybrid scaffolds for bone tissue engineering: Integration of composites and bioactive hydrogels loaded with hDPSCs. Biomater. Adv. 2025, 166, 214042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghaei, S.; Feizbakhsh, M.; Attar, B.M.; Khoshdel, A.; Abdali, H. Autografts, Bone Substitutes, and Combined Approaches for Secondary Alveolar Bone Grafting: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2025, 83, 950–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, L.; Yang, S.; Zhao, C.; Yang, J.; Li, F.; Xu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, K.; Xiong, C.; et al. Prospects and challenges for the application of tissue engineering technologies in the treatment of bone infections. Bone Res. 2024, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanzadeh, E.; Seifalian, A.; Mellati, A.; Saremi, J.; Asadpour, S.; Enderami, S.E.; Nekounam, H.; Mahmoodi, N. Injectable hydrogels in central nervous system: Unique and novel platforms for promoting extracellular matrix remodeling and tissue engineering. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 20, 100614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.K.; Yee, M.M.F.; Chin, K.Y.; Ima-Nirwana, S. A review of the application of natural and synthetic scaffolds in bone regeneration. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foroughi, A.H.; Razavi, M.J. Multi-objective shape optimization of bone scaffolds: Enhancement of mechanical properties and permeability. Acta Biomater. 2022, 146, 317–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Liu, Y.; Xu, W.; Lu, X.; Guo, L.; Liu, Y.; Tian, S.; Liu, B.; Zhang, J.; Wen, C. Additive manufacturing of functionally graded porous titanium scaffolds for dental applications. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 139, 213018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishchenko, O.; Volchykhina, K.; Maksymov, D.; Manukhina, O.; Pogorielov, M.; Pavlenko, M.; Iatsunskyi, I. Advanced Strategies for Enhancing the Biocompatibility and Antibacterial Properties of Implantable Structures. Materials 2025, 18, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makowski, P.; Kuś, W. Optimization of bone scaffold structures using experimental and numerical data. Acta Mech. 2016, 227, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, A.H.; Razavi, M.J. Shape optimization of orthopedic porous scaffolds to enhance mechanical performance. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 128, 105098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahraminasab, M. Challenges on optimization of 3D-printed bone scaffolds. BioMed. Eng. OnLine 2020, 19, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.R.; Guedes, J.M.; Flanagan, C.L.; Hollister, S.J.; Fernandes, P.R. Optimization of scaffold design for bone tissue engineering: A computational and experimental study. Med. Eng. Phys. 2014, 36, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Günther, F.; Wagner, M.; Pilz, S.; Gebert, A.; Zimmermann, M. Design procedure for triply periodic minimal surface based biomimetic scaffolds. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 126, 104871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezapourian, M.; Jasiuk, I.; Saarna, M.; Hussainova, I. Selective laser melted Ti6Al4V split-P TPMS lattices for bone tissue engineering. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 251, 108353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Meenashisundaram, G.K.; Kandilya, D.; Fuh, J.Y.H.; Dheen, S.T.; Kumar, A.S. A biomechanical evaluation on Cubic, Octet, and TPMS gyroid Ti6Al4V lattice structures fabricated by selective laser melting and the effects of their debris on human osteoblast-like cells. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 137, 212829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maevskaia, E.; Guerrero, J.; Ghayor, C.; Bhattacharya, I.; Weber, F.E. Triply periodic minimal surface-based scaffolds for bone tissue engineering: A mechanical, in vitro and in vivo study. Tissue Eng. Part A 2023, 29, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peta, K.; Kubiak, K.J.; Sfravara, F.; Brown, C.A. Dynamic wettability of complex fractal isotropic surfaces–Multiscale correlations. Tribol. Int. 2025, 214, 111145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehder, E.; Ashcroft, I.; Wildman, R.; Ruiz-Cantu, L.; Maskery, I. A multiscale optimisation method for bone growth scaffolds based on triply periodic minimal surfaces. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2021, 20, 2085–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezapourian, M.; Kumar, R.; Hussainova, I. Effect of unit cell rotation on mechanical performance of selective laser melted Gyroid structures for bone tissue engineering. Prog. Eng. Sci. 2024, 1, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deering, J.; Mahmoud, D.; Rier, E.; Lin, Y.; do Nascimento Pereira, A.C.; Titotto, S.; Fang, Q.; Wohl, G.R.; Deng, F.; Grandfield, K.; et al. Osseointegration of functionally graded Ti6Al4V porous implants: Histology of the pore network. Biomater. Adv. 2023, 155, 213697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suksawang, B.; Chaijareenont, P.; Silthampitag, P. Effect of Unit Cell Design and Volume Fraction of 3D-Printed Lattice Structures on Compressive Response and Orthopedics Screw Pullout Strength. Materials 2025, 18, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedrelow, D.S.; Townsend, J.M.; Detamore, M.S. Osteochondral Regeneration With Anatomical Scaffold 3D-Printing—Design Considerations for Interface Integration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2025, 113, e37804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Zou, S.; Pan, B.; Li, G.; Shao, L.; Du, J. Biomechanical properties of cylindrical and twisted triply periodic minimal surface scaffolds fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 56, 102899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, B.; Salary, R.R. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Modeling of Material Transport through Triply Periodic Minimal Surface (TPMS) Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. J. Biomech. Eng. 2025, 147, 031007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koju, N.; Niraula, S.; Fotovvati, B. Additively Manufactured Porous Ti6Al4V for Bone Implants: A Review. Metals 2022, 12, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranuša, M.; Odehnal, L.; Kučera, O.; Nečas, D.; Hartl, M.; Křupka, I.; Vrbka, M. Effect of surface texturing on friction and lubrication of Ti6Al4V biomaterials for joint implants. Tribol. Lett. 2025, 73, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robau-Porrua, A.; González, J.E.; Arancibia-Castillo, R.; Picardo, A.; Araneda-Hernández, E.; Torres, Y. Design, fabrication, and characterization of novel dental implants with porosity gradient obtained by Selective Laser Melting. Mater. Des. 2025, 251, 113660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomeu, F.; Costa, M.; Gomes, J.; Alves, N.; Abreu, C.; Silva, F.; Miranda, G. Implant surface design for improved implant stability—A study on Ti6Al4V dense and cellular structures produced by Selective Laser Melting. Tribol. Int. 2019, 129, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadpoor, A.A.; Campoli, G.; Weinans, H. Neural network prediction of load from the morphology of trabecular bone. Appl. Math. Model. 2013, 37, 5260–5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikhina, T.; Khovanova, N.A.; Mallick, K.K. Artificial neural networks in hard tissue engineering: Another look at age-dependence of trabecular bone properties in osteoarthritis. In Proceedings of the IEEE-EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics (BHI), Valencia, Spain, 1–4 June 2014; pp. 622–625. [Google Scholar]

- Khalvandi, A.; Saber-Samandari, S.; Aghdam, M.M. Application of artificial neural networks to predict Young’s moduli of cartilage scaffolds: An in-vitro and micromechanical study. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 136, 212768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouloodi, S.; Rahmanpanah, H.; Gohery, S.; Burvill, C.; Davies, H.M. Feedforward backpropagation artificial neural networks for predicting mechanical responses in complex nonlinear structures: A study on a long bone. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 128, 105079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahimi, S.; D’Andrea, L.; Gastaldi, D.; Rivolta, M.W.; Vena, P. Machine Learning approaches for the design of biomechanically compatible bone tissue engineering scaffolds. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2024, 423, 116842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Lyu, Y.; Bosiakov, S.; Liu, Y. Inverse design of anisotropic bone scaffold based on machine learning and regenerative genetic algorithm. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1241151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezapourian, M.; Cheloee Darabi, A.; Khoshbin, M.; Hussainova, I. Multi-Objective Machine Learning Optimization of Cylindrical TPMS Lattices for Bone Implants. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Lee, C.K.M.; Tsang, Y.P.; Waqar, S. A machine learning-based recommendation framework for material extrusion fabricated triply periodic minimal surface lattice structures. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Eng. 2025, 20, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherpour, R.; Bagherpour, G.; Mohammadi, P. Application of artificial intelligence in tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2025, 31, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanwar, S.; Al-Ketan, O.; Janarthanan, G.; Vijayavenkataraman, S. Additively manufactured stochastic and gyroid scaffold design towards osseointegration and bone regeneration in a rabbit femur model. Mater. Des. 2025, 250, 113604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- nTop Inc. nTop, Release 4.1; nTop Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Sun, J.; Guo, K.; Wang, L. Compressive mechanical properties and energy absorption characteristics of SLM fabricated Ti6Al4V triply periodic minimal surface cellular structures. Mech. Mater. 2022, 166, 104241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonlau, M.; Zou, R.Y. The random forest algorithm for statistical learning. Stata J. 2020, 20, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Chen, Y.; Yao, B.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, N. A neural network boosting regression model based on XGBoost. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 125, 109067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neter, J.; Wasserman, W.; Kutner, M.H. Applied Linear Regression Models; Richard D. Irwin: Homewood, IL, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Pilia, M.; Guda, T.; Appleford, M. Development of composite scaffolds for load-bearing segmental bone defects. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 458253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, I.; Savalani, M.M.; Christopher, X.L.; Olkowski, R.; Ekaputra, A.K.; Tan, K.C.; Hutmacher, D.W. Towards a medium/high load-bearing scaffold fabrication system. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2009, 14, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuls, R.; Jiya, T.; Smit, T. Scaffold stiffness influences cell behavior: Opportunities for skeletal tissue engineering. Open Orthop. J. 2008, 2, e109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunaydin, O. Functionally Graded Lattice Structures for Structural Applications: Design, Production and Performance Analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, Politecnico di Torino, Turin, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Miralbes, R.; Santamaria, N.; Ranz, D.; Gomez, J. Mechanical properties of diamond lattice structures based on main parameters and strain rate. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2023, 30, 3721–3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, D.Z.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, M.; Jafar, S. Mechanical properties of optimized diamond lattice structure for bone scaffolds fabricated via selective laser melting. Materials 2018, 11, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.; Nazir, A.; Waqar, S.; Ali, U.; Gokcekaya, O. Effect of additive manufactured hybrid and functionally graded novel designed cellular lattice structures on mechanical and failure properties. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 128, 4873–4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, A.; Hussain, S.; Ali, H.M.; Waqar, S. Design and mechanical performance of nature-inspired novel hybrid triply periodic minimal surface lattice structures fabricated using material extrusion. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 38, 108349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemayehu, D.B.; Todoh, M.; Huang, S.J. Hybrid Biomechanical Design of Dental Implants: Integrating Solid and Gyroid Triply Periodic Minimal Surface Lattice Architectures for Optimized Stress Distribution. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaie, B.; Velay, X.; Saleem, W. Exploring the optimal mechanical properties of triply periodic minimal surface structures for biomedical applications: A numerical analysis. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2024, 160, 106757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, G.; Bala Murali, G. Designs, advancements, and applications of three-dimensional printed gyroid structures: A review. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 2024, 238, 965–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Li, H.; Han, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, H.; Cheng, J.; Shi, J.; Miao, Z.; Yu, B.; Lin, F. Mechanical and damping performances of TPMS lattice metamaterials fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. China Foundry 2024, 21, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghariya, J.; Gurrala, P.K. Finite element studies on Triply Periodic Minimal Surfaces (TPMS)—Based hip replacement implants. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 136, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieding, J.; Wolf, A.; Bader, R. Numerical optimization of open-porous bone scaffold structures to match the elastic properties of human cortical bone. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2014, 37, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Hu, S.; Chen, R.; Gu, Y.; Kong, X.; Tao, J.; Jiang, Y. Mechanical properties tailoring of topology optimized and selective laser melting fabricated Ti6Al4V lattice structure. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2019, 99, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weißmann, V.; Bader, R.; Hansmann, H.; Laufer, N. Influence of the structural orientation on the mechanical properties of selective laser melted Ti6Al4V open-porous scaffolds. Mater. Des. 2016, 95, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Hu, J.; Xu, Y.; Su, J.; Jing, Y. Review on mechanical properties of metal lattice structures. Compos. Struct. 2024, 342, 118267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigliotti, A.; Pasini, D. Mechanical properties of hierarchical lattices. Mech. Mater. 2013, 62, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yao, G.; Gao, K.; Xu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Guo, X.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Han, C. Study on mechanical properties of lattice structures strengthened by synergistic hierarchical arrangement. Compos. Struct. 2023, 304, 116304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhnen, P.; Haase, C.; Bültmann, J.; Ziegler, S.; Schleifenbaum, J.H.; Bleck, W. Mechanical properties and deformation behavior of additively manufactured lattice structures of stainless steel. Mater. Des. 2018, 145, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Meng, J.; Liu, J.; Ao, X.; Lin, S.; Yang, Y. Evaluation of the equivalent mechanical properties of lattice structures based on the finite element method. Materials 2022, 15, 2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamieh, L.L.D.; Popa, N.M.; Milodin, N.L.; Gheorghiu, D.; Comsa, S. The importance of optimization of lattice structures for biomedical applications. Rev. Tehnol. Neconv. 2019, 23, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Martorelli, M.; Gloria, A.; Bignardi, C.; Calì, M.; Maietta, S. Design of additively manufactured lattice structures for biomedical applications. J. Healthc. Eng. 2020, 2020, 2707560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Hou, W.; Xu, Q.; Li, S.; Hao, Y.; Yang, R. Ti-6Al-4V lattice structures fabricated by electron beam melting for biomedical applications. In Titanium in Medical and Dental Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 277–301. [Google Scholar]

- Vilardell, A.M.; Takezawa, A.; du Plessis, A.; Takata, N.; Krakhmalev, P.; Kobashi, M.; Yadroitsava, I.; Yadroitsev, I. Topology optimization and characterization of Ti6Al4V ELI cellular lattice structures by laser powder bed fusion for biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 766, 138330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Ye, J.h.; Huang, C.x.; Dai, J.h.; Cheng, K.j.; Xu, X.; Deng, L.q.; You, J.; Liu, Y.f. Gradient gyroid Ti6Al4V scaffolds with TiO2 surface modification: Promising approach for large bone defect repair. Biomater. Adv. 2024, 161, 213899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan-Manshadi, A.; Venezuela, J.; Demir, A.; Ye, Q.; Dargusch, M. Additively manufactured Fe-35Mn-1Ag lattice structures for biomedical applications. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 80, 642–650. [Google Scholar]

- Zhumabekova, A.; Perveen, A.; Talamona, D. Effect of the lattice structures on mechanical characterisation of additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V for biomedical application. Adv. Mater. Process. Technol. 2024, 11, 1285–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheloni, J.P.M.; Zluhan, B.; Silveira, M.E.; Fonseca, E.B.; Valim, D.B.; Lopes, E.S. Mechanical behavior and failure mode of body-centered cubic, gyroid, diamond, and Voronoi functionally graded additively manufactured biomedical lattice structures. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2025, 163, 106796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezapourian, M.; Hussainova, I. Optimal mechanical properties of Hydroxyapatite gradient Voronoi porous scaffolds for bone applications—A numerical study. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2023, 148, 106232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.J. Advanced porous scaffold design using multi-void triply periodic minimal surface models with high surface area to volume ratios. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2014, 15, 1657–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Semirumi, D.; He, A.; Pan, Z.; Alizadeh, A. Physical, mechanical characterization, and artificial neural network modeling of biodegradable composite scaffold for biomedical applications. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 136, 108889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).