Abstract

One of the main challenges in welding aluminium concerns structural integrity and a significant reduction in mechanical properties in the region adjacent to the weld. Design provisions can result in a drastic reduction, which may exceed 50% of the base metal resistance. This research aims to evaluate the accuracy of the HAZ extent values codified in Eurocode 9 for T-connections fabricated from artificially aged 6082 aluminium alloy, which is widely used in load-bearing structures. Three plate thicknesses (6, 8 and 10 mm) and two pulsed MIG welding processes (DC-MIG-P and AC-MIG-P) were used to fabricate 20 T-connection specimens (10 different configurations) in accordance with EN 1090-3. The study focuses on characterising the welding zones through hardness testing and metallographic examination. Results show that AC-MIG-P offers better control over thermal input and may reduce structural distortion, while DC-MIG-P provides more robust fusion and metallurgical continuity. Findings related to HAZ extent (12.77 mm and 15.36 mm maximum measured for AC-MIG-P and DC-MIG-P, respectively) suggest that Eurocode 9 may be overly conservative for pulsed MIG welding processes, particularly for greater plate thicknesses where a HAZ extent of 22.50 mm or more is specified. Consequently, adopting more precise, process-specific HAZ characterisations could lead to more realistic connection design and structural behaviour.

1. Introduction

Aluminium structural members are typically manufactured by extrusion, which allows a wide range of profile shapes that cannot be achieved with conventional structural materials [1,2,3]. However, the size of extruded cross-sections is limited by the capacity of the hydraulic presses used in the extrusion process. As a result, extruded members may be insufficient when higher load-bearing capacities are required. In such cases, aluminium profiles with greater dimensions can be produced by longitudinal welding of aluminium plates. Longitudinal welding also enables the fabrication of tapered members, allowing more efficient use of material. Due to the numerous difficulties associated with welding aluminium alloys, welded aluminium members remain poorly investigated [4,5].

One of the main challenges in welding aluminium structures is related to a significant reduction in mechanical properties in the region adjacent to the weld, commonly referred to as the Heat-Affected Zone (HAZ) [6]. An additional challenge represents the occurrence of pronounced welding-induced deformations, resulting from the relatively higher coefficients of thermal expansion and thermal conductivity of aluminium compared to steel [7]. For this reason, welding processes with low thermal transfer efficiency, such as Tungsten Inert Gas (TIG) welding, often lead to significant deformation [8]. Consequently, to minimise deformations, it is desirable to employ welding processes with higher thermal efficiency, while simultaneously reducing the heat input into the base material [9].

Considering the recommendations of EN 1090-3 [10], the applicable processes for manufacturing aluminium structures are Metal Inert Gas (MIG), TIG and Friction Stir Welding (FSW) processes. The FSW process fundamentally differs from arc welding processes (TIG and MIG), as it does not involve melting of the material [11,12]. As such, the HAZ and connection geometry (for instance, achieving the required throat thickness of a fillet weld) are not directly comparable. Additionally, FSW requires specialised equipment and conditions and inherently offers limited flexibility.

Compared to TIG welding, MIG offers significantly higher productivity and is better suited for automation and robotic applications. Furthermore, by adjusting the waveform of the welding current, it is possible to control the amount of deposited material and heat distribution, while also reducing the consumption of shielding gases and minimising the generation of welding fumes and vapours. Consequently, current industrial practice predominantly favours the MIG process [13].

The standardised technological framework recommends the application of the MIG process with conventional spray arc metal transfer, or the use of pulsed currents, which allow for reduced heat input while achieving the same melting effect [14]. Although the pulsed MIG welding process with direct current (DC-MIG-P) is already established as an industry standard, the pulsed MIG process using alternating current (AC-MIG-P) has recently become increasingly common. In this method, metal transfer occurs under alternating current conditions, further reducing heat input compared to conventional MIG processes [15]. It is well established that minimal heat input and a narrower fusion zone result in reduced extent of the HAZ and welding-induced deformations; however, it remains essential to determine appropriate process parameters to ensure acceptable weld quality without defects such as lack of fusion. Nevertheless, ongoing advancements in pulsed MIG welding, such as the development of double-pulse currents [16,17,18] or the use of alternating currents [19,20,21], continue to enhance operational performance and productivity. Further improvement in deposition rate and welding speed is achieved through the application of AC-MIG-P welding, where, due to certain physical phenomena, higher melting rates can be achieved at the same nominal current as in conventional positive-pole wire welding [22]. Due to the variable polarity in the AC-MIG-P process, there is a repeatable change between the cathode and anode on the metal wire, as well as forces in the arc, which require modern high-frequency inverter power sources to control the behaviour in the arc plasma. Consequently, further research is needed to give a more detailed understanding of electromagnetic forces not only in experimental research but also in a simulation approach [23,24].

Therefore, in aluminium structural welding, the MIG process enables optimal productivity while minimising deformation and loss of mechanical strength in the welded connection. The MIG process, especially when using variable-polarity pulsed current, is a viable welding technology, and its reduced heat input also makes it suitable for Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM). However, it is essential to note that low heat input can lead to imperfections such as porosity and lack of fusion, making precise quantification and control of all operating parameters essential.

The most commonly used aluminium alloys for structural purposes are those of the 6xxx series, owing to their favourable mechanical properties [2,25,26,27]. However, due to their strengthening mechanism, these alloys are particularly susceptible to strength loss within the HAZ. The main alloying elements in 6xxx series aluminium alloys are magnesium (Mg) and silicon (Si). These alloys are heat-treatable and typically undergo solution heat treatment followed by ageing [28]. The primary strengthening mechanism of the 6xxx series alloys is the formation of magnesium silicide (Mg2Si) precipitates within the metal matrix. These precipitates hinder dislocation motion and thereby improve the mechanical properties of the material, primarily by increasing its strength [29,30,31]. During welding, however, the elevated temperatures in the HAZ cause precipitates to dissolve into the matrix, resulting in a loss of strength. Artificially aged alloys (T5, T6) of the 6xxx series, which contain a higher precipitate density, are more susceptible to strength loss at elevated temperatures compared with naturally aged (T4) alloys [32].

For the design of aluminium structures in Europe, the set of standards collectively known as Eurocode 9 is applied. The first part of this standard, EN 1999-1-1 [33], provides design guidance on the extent of the HAZ and the reduction of mechanical properties within this region. For aluminium alloys of the 6xxx series, particularly the artificially aged tempers, the reduction in 0.2% proof strength can exceed 50% [34,35]. In addition, the codified HAZ extent can reach 40 mm, depending on the connection type and plate thickness [33]. These provisions can lead to a significant reduction in the design resistance of welded members.

One of the earliest studies on the reduction of mechanical properties in the HAZ was conducted by Hill et al. [36] and published in 1962. The authors tested a series of welded aluminium connections and proposed the “1-inch rule” for estimating the extent of the HAZ. Subsequent studies by Mazzolani [37], Soetens [38], and Moen [39] on butt-welded aluminium connections reported that the 1-inch rule provides a relatively good measure of the extent of the HAZ. Although the use of the MIG welding process was reported in the above studies, considering the date of publication, it can be assumed that the spray-arc technique was used.

The present research aims to evaluate the findings presented in the above studies and the accuracy of the HAZ extent values codified in EN 1999-1-1 [33] for T-connections fabricated from artificially aged 6xxx series aluminium alloy (EN AW-6082-T651), welded using two different pulsed MIG welding processes. One of the main objectives of the study was based on the assumption that modern pulsed MIG welding processes can achieve the fusion of the metal with reduced heat input and, therefore, a reduced extent of the HAZ. In accordance with the standard, the specimens were fabricated by longitudinal fillet welding of two plates measuring 150 × 500 mm to form a T-connection, which, according to EN 1999-1-1 [33], can be regarded as a T-connection with three valid heat paths. Hardness testing showed that the extents of the HAZ were consistently below the codified values defined in EN 1999-1-1 [33]. Specifically, for the DC-MIG-P and AC-MIG-P welded specimens, the measured values were up to approximately two times and three times lower than the corresponding codified values, respectively. Additionally, microstructural analyses were conducted to evaluate the weld quality of the fabricated specimens.

It should be noted that this research is part of a larger scientific project, REAL-fit (Reliable design methods for aluminium structures fit for future requirements [40]) [41]. The project aims to conduct comprehensive interdisciplinary research into the feasibility of utilising advanced automated welding technologies and to develop reliable design methods for welded structural members, connections/joints, and structural systems made of aluminium alloys.

2. Experimental Study

2.1. Scope of the Experimental Program

The experimental programme was designed to investigate the hardness distribution and metallurgical properties of welded aluminium T-connections fabricated using the EN AW-6082-T651 aluminium alloy. Two variations of metal inert gas processes were applied: DC-MIG-P and AC-MIG-P. The DC-MIG-P process represents a conventional and widely adopted industrial method, while the AC-MIG-P process was selected to explore its potential advantages in controlling heat input, thereby reducing residual stresses and limiting the extent of the HAZ.

To assess the influence of plate thickness on weld quality, three thicknesses were investigated: 6 mm, 8 mm, and 10 mm. The selection of plate thicknesses for the T-connection specimens presented in this paper was influenced by several factors related to the objectives of the broader research programme in which these specimens were tested. As noted in the introduction, the T-connection specimens were fabricated and tested as part of the REAL-fit project [40,41], which aims to develop reliable design methods for welded structural members, connections, joints, and systems made from aluminium alloys. Therefore, the plate thicknesses were deliberately chosen with careful consideration of the available funding, the required number of test specimens, and the limitations of the testing equipment used in the study. In addition, the plate thicknesses used in this study fall into different thickness ranges for which EN 1999-1-1 [33] specifies different values of HAZ extent. The selected thicknesses, therefore, enable several HAZ extent intervals to be examined rather than only a single thickness range.

Furthermore, the general methodology within the REAL-fit project adopted the fabrication and testing of two nominally identical specimens as a reasonable compromise between repeatability and coverage of the test scope. In the case of the aluminium alloy EN AW-6082-T651, a total of 20 T-connection specimens (two for each of 10 representative types) were selected for detailed investigation within the scope of this study, as shown in Table 1. An exception to this rule are the specimen types T-DC-6A10/6A10 and T-AC-6A10/6A10, for which a total of four nominally identical specimens were fabricated. The analysis focuses on characterising the HAZ through hardness testing and metallographic examination, with particular emphasis on how welding process type (DC-MIG-P vs. AC-MIG-P) and base plate thickness influence the extent, hardness distribution, and microstructural features of the welded zone.

Table 1.

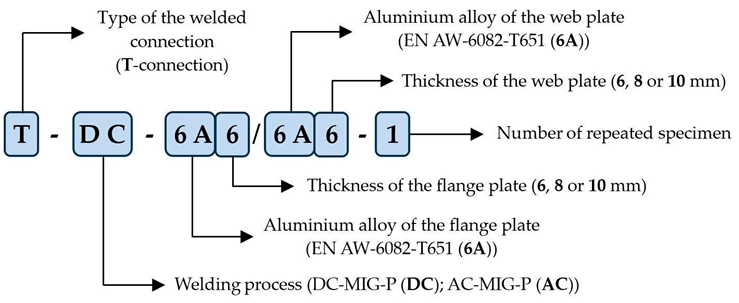

Nomenclature for T-connection specimens.

To facilitate traceability and data organisation, a specimen labelling system was developed, as illustrated in Table 1. Each specimen was marked with a label indicating connection type, alloy designation, plate thickness, welding procedure, and specimen number. Although the coding system may initially seem overly long, this is because the REAL-fit project covered a wide range of connection configurations and aluminium alloys [41]. The intention was to develop a unified coding system that could be used consistently across all papers published as part of the dissemination of the project’s research results.

Other aspects, such as residual stress measurements, detailed grain-level phase analysis, and mechanical behaviour under load (e.g., tensile or fatigue testing), are beyond the scope of this study and will be addressed in future work.

2.2. Material, Connection Design and Specimen Fabrication

The experimental study focused on T-connections welded from aluminium alloy EN AW-6082-T651 (ISO Al Si1MgMn). This alloy belongs to the 6xxx series of heat-treatable aluminium alloys. The Al-Mg-Si system includes a quasi-binary eutectic formed between the aluminium solid solution and the intermetallic compound Mg2Si. In alloy EN AW-6082, the Mg:Si ratio is closer to 1.73, which influences its low solution annealing temperature, between 500 and 530 °C, and low quench sensitivity [42,43]. Thus, it can be quenched in air before artificial ageing. The tested alloy EN AW-6082-T651 is welded after treatment that consisted of solution annealing, stress relieving, stretching, and artificial ageing. Age-hardening treatment produces a base aluminium matrix with 1.1% Mg2Si dispersed precipitates and gives the best combination of properties in the 6xxx series of aluminium alloys. It is widely used in structural applications as a replacement for the alloy EN AW-6061 due to its favourable strength-to-weight ratio, good corrosion resistance, good fabrication in the cold state, good machinability and acceptable weldability [44]. The nominal mechanical properties of the alloy AW-6082-T651, as specified in [33] for thicknesses 6 < t ≤ 12.5 mm, include a 0.2% proof strength of approximately 255 MPa, an ultimate tensile strength of around 300 MPa, and elongation after fracture of 9%.

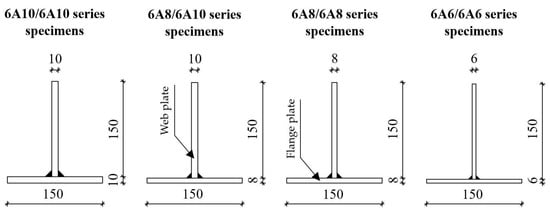

The aluminium plates used to fabricate the T-connections had thicknesses of 6 mm, 8 mm, and 10 mm. Each T-connection consisted of two plates of identical alloy and thickness, with dimensions of 150 mm × 500 mm. The geometrical configurations of the tested T-connections are presented in Figure 1, which shows the various dimensions and thickness combinations. Constituent plates were cut from larger parent hot-rolled plates using plasma cutting and were mechanically cleaned. Degreasing was performed with acetone immediately before welding to ensure surface cleanliness and improve weld quality.

Figure 1.

Geometric properties of T-connection specimens for testing the properties of fillet welds (dimensions in mm).

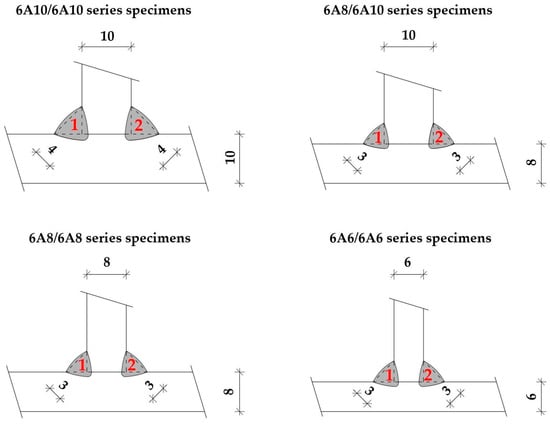

The connection configuration corresponds to a standard T-connection without edge preparation. A double-sided fillet weld was applied along both sides of the vertical plate (web). Each weld pass on one side of the web plate of the T-shaped connection was completed continuously along the entire length before the corresponding weld pass was made on the opposite side. For specimens with plate thicknesses of 6 mm and 8 mm, a 3 mm fillet weld size was used, while for 10 mm plates, the weld size was increased to 4 mm, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Sequence of weld passes on the T-connection (dimensions in mm; weld-pass order shown in bold red numbers).

Welding parameters are systematically summarised in Table 2. It is important to address that the welding parameters were defined to achieve the same throat thickness for both welding processes, depending on the different base material thicknesses. Specifically, the filler material wire feed velocity was kept constant, while only the welding speed was adjusted to achieve the desired throat thickness. From that aspect, based on the same amount of melted filler material, it is possible to compare the influence of the arc physics of the two processes because the heat input differs significantly. Therefore, other effects of heat distribution in the weld metal and base material could be investigated. Welding parameters used in the research were defined through a series of tests as it was important to achieve a stable process, metal transfer, and obtain acceptable weld geometry with imperfections under the limits of valid production standards.

Table 2.

Main welding parameters.

Heat input was calculated according to EN 1011-1 [45] (thermal efficiency factor k = 0.8) using the following equation:

where Q is the heat input, k is the thermal efficiency factor, U is the arc voltage in [V], I is the welding current in [A], and v is the welding speed in [cm/min]. Welding current and voltage were measured according to [46] with true Root Mean Square (RMS) measuring equipment that enables precise and adequate data sampling. The voltmeter and ammeter were calibrated according to [47].

As shown in Table 2, heat input for the DC-MIG-P process is approximately 30% higher than for the AC-MIG-P process for the same wire feed velocity. In general, this means that the same productivity could be achieved for the equivalent weld geometry but with lower energy consumption. Additionally, this level of heat input difference provides a reasonable foundation for expecting different characteristics of the weld.

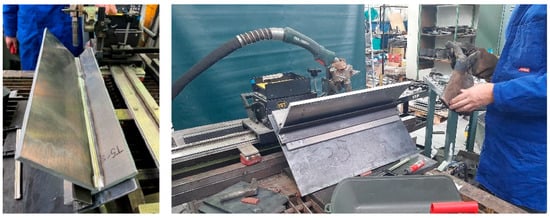

Welding was carried out using two variations of the metal inert gas (MIG 131 according to ISO 4063 [48]) process with pulsed current: DC-MIG-P and AC-MIG-P. The filler metal used was ISO 18273 [49]: S Al 5356/AlMg5Cr with a diameter of 1.2 mm, chosen for its compatibility with the base material and favourable mechanical properties in welded connections. Argon 5.0 (group I1 according to EN ISO 14175 [50]) with a minimum purity of 99.999% was used as shielding gas, with a constant flow rate of 21 L/min. Welding was performed with preheating at 40 °C and an interpass temperature of 60 °C to ensure the same thermal conditions for both processes and eliminate the influence of variable environmental conditions. A dedicated welding fixture was used to ensure repeatability and stability during fabrication, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Welding fixture and setup.

The welding was performed using mechanised assembly with a Bugo tractor to achieve a constant welding speed, as defined in Table 2. After welding, all specimens were visually inspected according to ISO 17637 [51] and ISO 10042 [52] and then grouped before further metallographic and hardness analysis, as presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Fabricated T-connection specimens before cutting and testing.

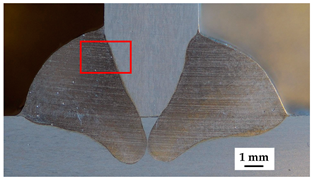

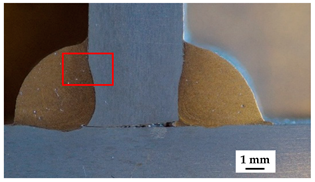

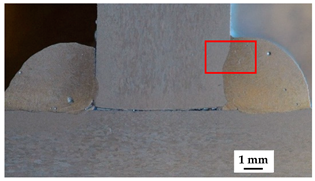

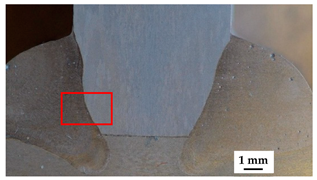

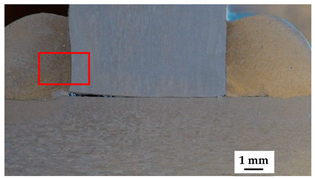

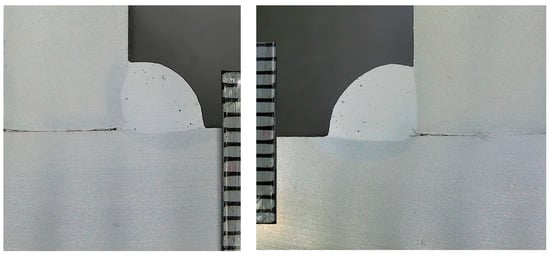

To confirm the proposed welding parameters optimisation, preliminary testing of macrographs was conducted to establish weld geometry and penetration for the AC-MIG-P and DC-MIG-P processes. The testing indicated that both processes achieved sufficient penetration; however, for the AC-MIG-P process, the risk margin for lack of fusion could pose a problem, particularly in poorly controlled real production environments. Nevertheless, to achieve the maximum possible difference in heat input for the same weld deposit, the proposed welding parameters were adopted for further research. Examples of macrographs for plate thicknesses of 8 mm and 10 mm are shown in Figure 5. The preliminary testing is consistent with the known characteristics of the analysed processes, confirming the suitability of the selected parameters for further research with controlled heat input differences.

Figure 5.

Preliminary macrographs for T-connections: of 8 mm/8 mm and 8 mm/10 mm using the AC-MIG-P process.

2.3. Preparation of Specimens for Microstructural Analysis and Hardness Testing

A microstructural analysis and hardness testing of welded connections made from EN AW-6082-T651 aluminium alloy were conducted to assess the weld quality and to examine microstructural changes and hardness properties within the welded specimens. For each process variant, hardness was tested, and macro- and microstructural analyses were performed on 10 different combinations of welded plate thicknesses.

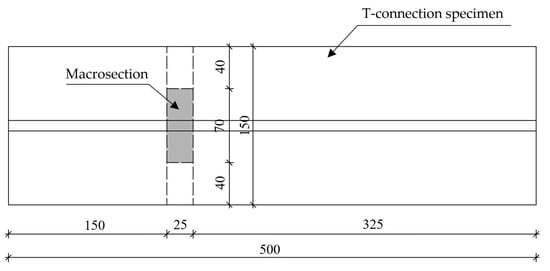

Macrosections were cut from T-connections using a bandsaw at positions specified in Figure 6. From each one of the welded T-connection specimens, one microsection was extracted and prepared. A metallographic polisher was used to polish the specimens to achieve a smooth and uniform surface, ensuring accurate hardness measurements. The polished surfaces were subsequently immersed in a sodium hydroxide solution to enhance the visibility of the microstructure on the testing surface.

Figure 6.

Fabricated T-connection specimens before cutting and testing (top view; dimensions in mm).

Specimens were prepared following standard metallographic procedures, including sectioning, grinding, polishing, and etching with appropriate reagents [53,54,55]. Grinding and polishing were conducted on the metallographic polisher: Mecatech 250 SPC (PRESI France, Eybens; France). The specimens were then cleaned and degreased in 95% ethyl alcohol in the ultrasonic bath: ElmaSonic Easy 40H (Elma Schmidbauer GmbH, Singen, Germany) at 20 °C for 2 min. Etching of microstructure was conducted in a mixture consisting of 15 mL HCl, 10 mL HF, and 85 mL H2O at 20 °C for 60 s, followed by rinsing with distilled water.

3. Microstructural Analysis

3.1. General

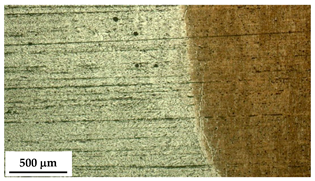

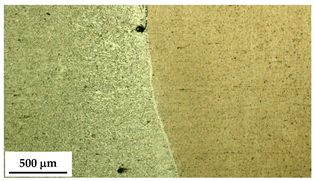

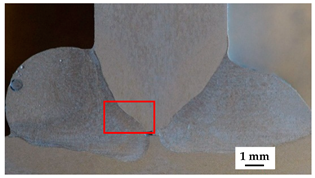

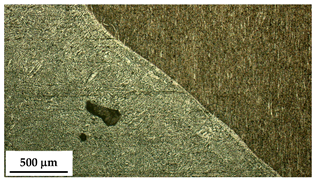

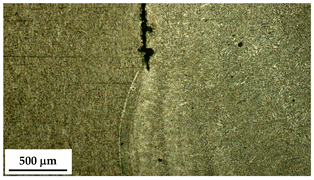

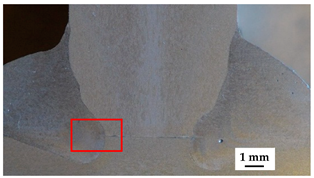

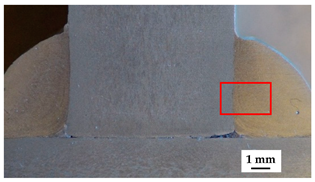

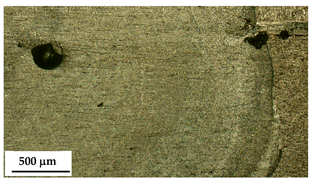

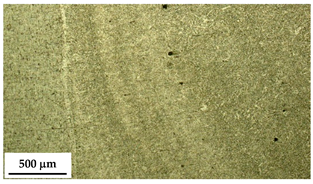

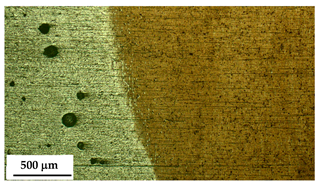

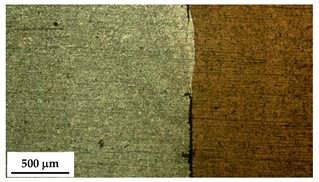

The microstructural characterisation was performed using an optical microscope, Olympus GX51 (Olympus Optical Co (Europa) GmbH, Hamburg, Germany), at various magnifications, with a focus on critical regions of the welds, namely the root, mid-thickness, cap, and HAZ. The objective of this investigation was to identify microstructural changes and potential defects such as microcracks, porosity, or segregation, and to evaluate the homogeneity and overall quality of the welded connections. The morphological characteristics of the weld microstructure and the base material were compared with photographs of the microstructure of alloy 6082-T651 presented in monographs and manuals [32,56]. Quantitative analysis of the weld microstructure, HAZ and base material was performed in the Microvision Suite ver.1. (I. Vovk Zagreb, Croatia) computer program [57]. Using the Microvision Suite ver.1, grain size analysis was performed according to ASTM E112 [58]. In all analysed welds, there were fewer than 10 bubble pores across the entire weld cross-section, which in more than 75% of cases were of regular spherical shape, but of various sizes with diameters between 0.10 and 0.30 mm. Due to the small number of spherical pores, porosity in the weld was analysed solely by measuring the average pore diameter in the Microvision Suite ver.1. computer program. In the macroscopic view of the T-joint in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6, the microstructural analysis location of the weld material is marked with a rectangle in the first row of the table, and the HAZ is shown in the second row. In all macroscopic images of the T-joint in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6, the scale is set to 1 mm. The scale in the HAZ microstructure view is set to 500 μm. As shown in the cross-sections of fillet welds in the Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6, all welds are convex. Weld penetration in a fillet joint depends on the type of electric arc and the plate’s thickness. Its value is measured according to the welding standard [52,59], and is listed in the last row of Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 3.

Microstructure of the weld and HAZ in EN AW 6082-T651 Alloy Specimens, t1 = t2 = 6 mm.

Table 4.

Microstructure of the weld and HAZ in EN AW 6082-T651 Alloy Specimens, t1 = t2 = 8 mm.

Table 5.

Microstructure of the weld and HAZ in EN AW 6082-T651 Alloy Specimens, t1 = t2 = 10 mm.

Table 6.

Microstructure of the weld and HAZ in EN AW 6082-T651 Alloy Specimens, t1 = 8 mm, t2 = 10 mm.

3.2. T-Connections with Uniform Thickness

The macro- and microstructural features of T-connections fabricated from EN AW 6082-T651 aluminium alloy plates of 6 mm, 8 mm, and 10 mm thickness, using both DC-MIG-P and AC-MIG-P welding processes, are presented in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6. The base material microstructure consists of an aluminium matrix alloyed with silicon, magnesium, and manganese, with fine precipitates of the intermetallic Mg2Si phase [30,31]. A rolling texture characteristic of hot-rolled aluminium plates is clearly visible, showing pronounced grain anisotropy in the direction of prior deformation with a relatively coarse-grained structure, corresponding to ASTM E112:2025 [58] numbers G4-G6. The weld material exhibits a fine-grained microstructure, corresponding to ASTM E112:2025 grades G8-G10. The HAZ experiences thermal cycles that can cause grain growth and partial recrystallisation, resulting in grain sizes finer than those of the base material but coarser than those of the weld metal. The average HAZ grain size is between ASTM E112:2025 numbers G6-G8. Welds made with a DC-MIG-P show satisfactory penetration and weld geometry according to [52]. Welds made with an AC-MIG-P exhibit low weld penetration, which can result in a weak joint and potentially reduced mechanical strength.

For T-connections produced from 6 mm thick plates, several key observations can be drawn. The weld metal solidifies rapidly, producing a fine, equiaxed grain structure with a smaller grain size, often ASTM E112:2025 number G8 or finer. The HAZ experiences thermal cycles that can cause grain growth or partial recrystallisation, often resulting in grain sizes finer than those of the base material but coarser than those of the weld metal. The presence of small cracks in HAZ suggests thermal stresses and microstructural changes. In both welds, small, entrapped gas pores were observed in within the weld metal. The pores appear separated from each other, forming a spherical shape. The regular spherical shape of porosity in the weld metal indicates their main pattern, the dissolution of hydrogen in liquid aluminium and its excretion from the melt during the weld solidification process. Hydrogen entry into the weld melt occurs for several reasons: moisture and condensation on base metal or filler wire; oxide/hydroxide films (Al2O3/MgO/Mg(OH)2) on plate edges or filler wire; dust contamination, dirty shop air, etc. [60,61].

In specimen T-DC-6A6/6A6-1, pores ranged from 0.12 mm to 0.14 mm in diameter, while in specimen T-AC-6A6/6A6-1, they ranged from 0.10 mm to 0.16 mm. In both specimens, columnar grain structures were evident in the fusion zone, indicating directional solidification under conditions of limited undercooling. On the base material side, within the HAZ, recrystallisation with polygonal grains was observed in specimen T-DC-6A6/6A6-1. In contrast, no recrystallisation was observed in specimen T-AC-6A6/6A6-1, attributed to the lower heat input associated with the AC-MIG-P process.

Specimen T-DC-6A6/6A6-1 showed complete penetration through the plate thickness, resulting in substantial mixing between the filler and base material. Conversely, specimen T-AC-6A6/6A6-1 exhibited minimal mixing, with no full penetration. At the narrowest sections of the weld (weld toe regions), microcracks were observed along the fusion line, likely caused by differential contraction during cooling due to the mismatch in shrinkage between the weld and base materials.

In specimen T-AC-6A8/6A8-1, as shown in Table 4, minimal mixing between the base and filler material was observed without any through-thickness penetration. According to ISO 6520 [62], this weld defect can be described as defect No. 503, Excess cap height. Microcracks up to 0.60 mm in length were detected at the fusion line and weld root. A thin recrystallisation band was noted in the HAZ on the base material side. Internally, gas pores ranging from 0.13 mm to 0.35 mm in diameter were found within the weld metal near HAZ. The presence of pores along the HAZ results from the evaporation of surface moisture and the retention of trapped gas in the solidified weld material. In contrast, on specimen T-DC-6A8/6A8-1, complete penetration of the weld was achieved through the entire thickness of the vertical plate in the T-connection. The weld is free of microcracks. Pores with an average diameter of 0.14 mm to 0.23 mm were found near the outer surface of the weld, indicating the mixing of moisture from the air with the shielding gas and its retention in the surface layer of the weld melt.

Regarding the T-connections made from 10 mm thick plates, as shown in Table 5, further structural distinctions were noted. In specimen T-DC-6A10/6A10-2, one-third of the plate thickness was symmetrically penetrated, and a distinct fusion line was formed, along which columnar grains were observed within the weld metal. No microcracks were detected in the weld, and recrystallised grains were evident in the HAZ of the base material. Gas pores ranging from 0.10 mm to 0.27 mm in diameter were present both at the weld crown and root.

In contrast, specimen T-AC-6A10/6A10-2 showed minimal fusion between the base and filler materials, with only small penetration of the base metal. The weld has a good external appearance, but the internal quality, or weld penetration, is poor. The weld root did not properly fuse with the base material on the left side of the specimen. Only a very thin recrystallised zone was observed in the HAZ. A small internal gas porosity was present within the weld, with pore diameters ranging from 0.18 mm to 0.20 mm. In addition to the already mentioned causes of the appearance of porosity, such as the appearance of moisture and its condensation on base metal or filler wire; remains of oxide/hydroxide films (Al2O3/MgO/Mg(OH)2) on plate edges or filler wire; and dust contamination of the base materials, the cause of the appearance of porosity here can also be the increased turbulence of the melt in the weld and the presence of instability and higher harmonics in the voltage waveform of the AC arc [61,63,64]. The lower heat input during welding with an alternating electric arc, and its rapid removal into the interior of the 10 mm thick plate, caused the filler material in the weld to solidify quickly, without mixing with the base material of the specimen. Because of this, the HAZ is also very thin, and there is no recrystallisation of the base material grains around it. An additional unfavourable effect of rapid solidification of the weld filler is the formation of elongated pores and microcracks near the HAZ. This unfavourable sticking of the weld material at 10 mm thick T-connections indicates that the alternating current strength and the heat introduced into the weld are insufficient for this thickness of the plates.

These microstructural and macrostructural characteristics, detailed in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5, confirm that the choice of welding process, along with the plate thickness, significantly influences the degree of fusion, the formation of defects such as pores and microcracks, and the extent of recrystallisation in the HAZ. The DC-MIG-P process generally resulted in deeper penetration, increased mixing of filler and base metals, and more pronounced recrystallisation. In contrast, the AC-MIG-P process yielded narrower fusion zones and limited thermal effects on the surrounding base material.

The welded parts of the T-connection were made of the same aluminium alloy Al-Mg-Si with a small amount of Cu, which is a favourable alloy for welding, with a low tendency for hot cracks [32]. Therefore, they were not observed in the analysed macro-sections of the welds. However, it should be noted here that the increased tendency of hot cracks to appear occurs in cases of welding aluminium alloys of different chemical composition or significant differences in the thickness of the welded plates.

3.3. T-Connections with Varying Thickness

The macro- and microstructural features of T-connections made from EN AW 6082-T651 aluminium alloy, using combinations of plates with different thicknesses (8 mm and 10 mm), and welded by DC-MIG-P and AC-MIG-P processes, are presented in Table 6. The microstructural characteristics of the T-connections involving the 10 mm thick plate enable several observations regarding the influence of the welding process on the weld zone and the HAZ.

In specimen T-DC-6A8/6A10-1, welded using the DC-MIG-P process, the weld filler penetrated up to one-quarter of the plate thickness and mixed with the base specimen material. Within the weld metal, dendritic structures characteristic of the filler material were observed, accompanied by columnar grains oriented along the solidification front. Numerous gas pores were present throughout the weld metal, with diameters ranging from 0.11 mm to 0.26 mm. The HAZ showed clear signs of recrystallisation of the base material grains, indicating significant thermal influence of the weld on the base material.

In contrast, specimen T-AC-6A8/6A10-1, produced by the AC-MIG-P process, exhibited no significant mixing between the filler and base material, nor any penetration into the base metal. On the left-hand side of the specimen, the weld appeared to be merely adhered to the base metal, with only partial bonding observed. A similar partial lack of fusion was also evident at the weld root on the right-hand side of the specimen. Also, a weld defect No. 503, Excess cap height was observed [62]. The recrystallised zone within the HAZ of the base material was notably thin. Internal gas porosity was present within the weld metal, with pores ranging from 0.10 mm to 0.30 mm in diameter. The absence of mixing of the filler material and the base material of specimens and the very thin HAZ are the result of the smaller amount of heat introduced into the weld and its intensive removal to the cooler core of the plate.

These observations further confirm the sensitivity of weld penetration, fusion characteristics, and microstructural development to both the welding method and the local thickness distribution of the plates. The DC-MIG-P process led to deeper penetration and more significant thermal effects in the base material, while the AC-MIG-P process produced limited fusion and a narrower HAZ with minimal recrystallisation.

However, lower penetration with a lack of fusion generally occurs in thicknesses of 8 mm and 10 mm welded using the AC-MIG-P process. Furthermore, this was not an issue for every analysed joint, but only for a few that were critically addressed in this research. This confirms that these conditions are very close to the minimum heat input limit, where lack of fusion appeared randomly, but it also allows the welding parameter range to be narrowed for further research.

The weld filler material ISO 18273: S Al 5356/AlMg5Cr [49] is not a heat-treatable aluminium alloy and has a lower hardness than the base material, regardless of the welding process. Grain recrystallisation in the heat-affected zone, when welding with the DC-MIG-P process, will cause a significant reduction in the hardness of the EN AW-6082-T651 base material around the weld. In contrast, when welding with the AC-MIG-P process, the HAZ with the grain recrystallisation zone is very narrow, and the softened area around the weld is expected to be narrower than in DC welding.

4. Macrostructural Evaluation

4.1. Hardness Testing

4.1.1. Testing Procedure

Testing was conducted on macrosections to determine the extent of the HAZ. From each welded T-connection, a single macrosection was extracted. This resulted in a total of 20 macrosections selected for analysis and subjected to hardness measurements. All measurements were conducted with the Brivisor KL2 hardness testing device (Reicherter, Esslingen am Neckar, Germany), which was developed by Reicherter in 1977 for carrying out Vickers and Knoop hardness tests. The hardness tester is calibrated according EN ISO 17025 [47], while the hardness measurements were performed using the Vickers HV5 method, following the standard EN ISO 6507-1 [65].

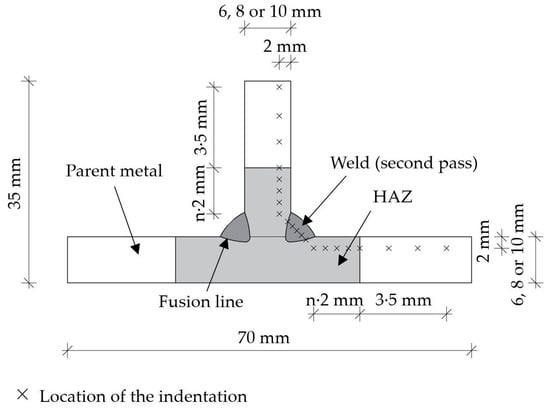

The dimensions of the fillet-welded macrosections and the associated hardness testing plan are shown in Figure 7. The flange length of all fillet-welded macrosections was 70 mm, with a total height of 35 mm. These dimensions were designed to meet the hardness testing requirements specified by EN ISO 9015-1 [66]. One measurement line was defined for hardness testing on each fillet-welded macrosection, located on the side of the specimen where the second weld pass was performed. It was assumed that on this side, the effect of the weld on the base metal hardness reduction would be more pronounced, as the second pass was carried out on material that had been slightly preheated by the first pass. The measurement line was parallel to and positioned 2 mm from the edges of the macrosection.

Figure 7.

Dimensions of fillet-welded macrosections and the corresponding hardness measurement plan.

Along the measurement line, three hardness measurements were performed within the weld metal and two at the fusion line—one on each side of the weld. In the HAZ, hardness measurements were taken along the line with 2 mm spacing between the centres of adjacent indentations until the hardness of the base material was reached. In the base material, six hardness measurements were performed along each measurement line—three on each side of the macrosection—with 5 mm spacing between the centres of adjacent indentations.

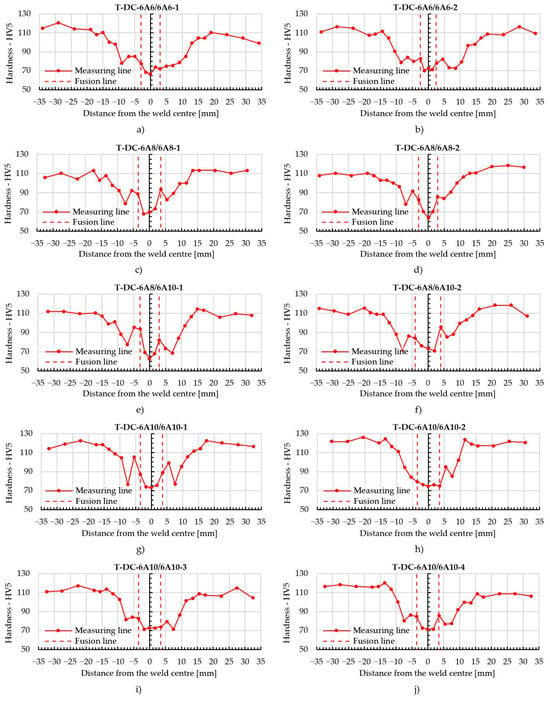

4.1.2. Discussion of Hardness Test Results

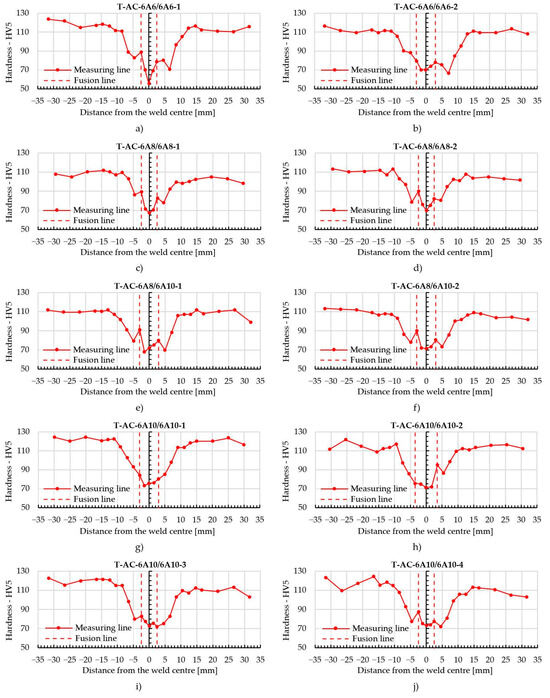

The results of hardness measurements are presented in Figure 8 for T-connections welded using the DC-MIG-P process, and in Figure 9 for T-connections welded using the AC-MIG-P process. The horizontal axis represents the distance from the measurement point to the weld centre along the measurement line. Note that in figures, negative values on the horizontal axis refer to the flange plate of the connection, while positive values refer to the web plate. The vertical axis shows the hardness values obtained from the Vickers hardness test with a testing force of 5 kg (HV5). Hardness distributions are presented as lines with data points, where each point represents the position of an indentation where hardness was measured. The solid red line with points shows the distribution of hardness values along the measurement line, while the vertical dashed red lines represent the intersection between the fusion lines and the measurement line.

Figure 8.

Hardness distribution on macrosections of connections welded using the DC welding process (negative values on diagrams refer to the flange plate, positive values refer to the web plate): (a) T-DC-6A6/6A6-1; (b) T-DC-6A6/6A6-2; (c) T-DC-6A8/6A8-1; (d) T-DC-6A8/6A8-2; (e) T-DC-6A8/6A10-1; (f) T-DC-6A8/6A10-2; (g) T-DC-6A10/6A10-1; (h) T-DC-6A10/6A10-2; (i) T-DC-6A10/6A10-3; (j) T-DC-6A10/6A10-4.

Figure 9.

Hardness distribution on macrosections of connections welded using the AC welding process (negative values on diagrams refer to the flange plate, positive values refer to the web plate): (a) T-AC-6A6/6A6-1; (b) T-AC-6A6/6A6-2; (c) T-AC-6A8/6A8-1; (d) T-AC-6A8/6A8-2; (e) T-AC-6A8/6A10-1; (f) T-AC-6A8/6A10-2; (g) T-AC-6A10/6A10-1; (h) T-AC-6A10/6A10-2; (i) T-AC-6A10/6A10-3; (j) T-AC-6A10/6A10-4.

The hardness profiles of the T-connections welded using the DC-MIG-P process exhibit characteristic softening in the HAZ relative to the base material. For specimens welded with plates of equal thickness, specifically 6 mm and 8 mm, the minimum hardness values were observed in the weld zone, typically ranging between 65 HV5 and 75 HV5, compared to average base material hardness values of approximately 110 HV5, which is typical for age-hardened alloy EN AW-6082-T651.

In specimens welded from 6 mm thick plates (e.g., T-DC-6A6/6A6-2), the softening zone extended over a distance of approximately 8–10 mm from the weld centre on each side, as shown in Figure 8a,b. The hardness within the weld metal was generally comparable to that within the adjacent HAZ, indicating significant thermal cycling and recrystallisation effects. Recovery of the base material hardness was gradual, occurring at distances exceeding 10 mm from the weld centre.

For the 8 mm thick specimens (e.g., T-DC-6A8/6A8-2), a similar behaviour was observed, with minimum hardness values dropping to approximately 65 HV5, and recovery towards base material hardness occurring at slightly shorter distances compared to the 6 mm specimens (around 5–7 mm from the weld), as shown in Figure 8c,d.

In specimens comprising dissimilar thicknesses (8 mm and 10 mm, e.g., T-DC-6A8/6A10-2), the hardness profiles remained asymmetric, with the location of minimum hardness depending on both the process and specimen configuration. In DC-MIG welds, one specimen exhibited nearly symmetric softening Figure 8e, while the other showed a more pronounced reduction on the thicker (10 mm) side Figure 8f. The minimum hardness values in these connections were around 70 HV5.

Specimens welded from 10 mm thick plates (e.g., T-DC-6A10/6A10-2) exhibited the widest softened zones, extending approximately 12–15 mm from the weld centre, as shown in Figure 8g,j. The base material hardness was restored only beyond these distances, indicating prolonged thermal exposure associated with greater thickness and higher heat input during welding. The broader extent of the HAZ is attributed to the higher heat input required to weld thicker sections.

Overall, DC-MIG-P welded connections show broader HAZ extents and moderate softening; however, the extent of the softened zone remains well within—i.e., clearly below—the limits prescribed by applicable standards [33], with hardness recovering towards the base material over larger distances, particularly in thicker plates.

In comparison to the DC-MIG-P welded T-connections, the hardness profiles of the T-connections welded using the AC-MIG-P process showed a narrower and more localised softening around the weld area (Figure 9). Since the heat input for the AC-MIG-P process is approximately 30% lower than for the DC-MIG-P process, it is indicative and expected that the HAZ will be narrower. The quantification of this softened area conducted in this research has shown that although the hardness reduction was relatively similar for both welding processes, the HAZ in the AC-MIG-P welded specimens was on average, approximately 25% narrower than in the DC-MIG-P welded counterparts.

For the 6 mm thick specimens (e.g., T-AC-6A6/6A6-2), minimum hardness values were measured in the range of 55–65 HV5, similar to those observed in DC-MIG-P specimens. However, the recovery to base material hardness occurred much faster in the AC-MIG-P specimens, typically within 5–7 mm from the weld centre, as shown in Figure 9a,b. This was attributed to insufficient heat input to promote recrystallisation processes in a larger area around the weld.

In 8 mm thick specimens (e.g., T-AC-6A8/6A8-2), the minimum hardness dropped to approximately 70 HV5 compared to approximately 65 HV5 measured in their respective DC-MIG-P welded counterparts. However, the softening was confined to a narrower zone, with hardness recovery occurring within 8–9 mm, as shown in Figure 9c,d. The profile showed steeper gradients between the softened area and the unaffected base material compared to DC-MIG-P specimens.

Connections involving dissimilar thicknesses (8 mm and 10 mm, e.g., T-AC-6A8/6A10-2) presented an asymmetrical hardness distribution, again reflecting the different thermal responses of the two thicknesses, as shown in Figure 9e,f. However, the softening zone remained narrower than in DC-MIG-P specimens, indicating effective control of heat input.

For the 10 mm thick specimens (e.g., T-AC-6A10/6A10-2), although the absolute minimum hardness values remained comparable (68–72 HV5), the extent of the softened zone was considerably reduced compared to DC-MIG-P welds, with hardness recovery occurring within 10 mm from the weld centre, as shown in Figure 9g–j.

It should be noted that the presence of local hardness increases in the HAZ was observed in the majority of specimens, particularly those welded with the DC-MIG-P welding process. This phenomenon was attributed to local artificial ageing caused by two consecutive passes performed to form a welded connection, as has already been proven by [32,42,56].

Finally, it can be stated that the overall effect of using the AC-MIG-P process is the confinement of thermal effects to a narrower region, resulting in sharper transitions in hardness and more efficient retention of mechanical properties in the base material.

It is important to note that this study does not include results from mechanical testing of welded specimens (e.g., tensile tests) and therefore, relies entirely on hardness profiling to characterise the HAZ extent. While Vickers hardness testing is widely used to qualitatively assess local softening in aluminium alloys, its correlation with reductions in mechanical properties, such as 0.2% proof strength or tensile strength, is empirical and not universally reliable. Some studies have shown that for 6xxx-series aluminium alloys, the relationship between hardness and strength is strongly dependent on alloy temper, thermal history, and post-weld ageing conditions [67,68]. Consequently, any attempt to estimate the reduction in mechanical properties in the HAZ based solely on hardness measurements must be treated with caution.

Eurocode 9 does not define strength reduction in the HAZ through hardness values but instead prescribes reduction factors, often exceeding 50%. These factors are uniform across the HAZ extent and do not account for variations in welding processes. While the present study identifies HAZ extents significantly narrower than those implied by EC9 [33], with a strengthening effect associated with hardening towards the base material, it cannot quantify the associated loss of mechanical strength. In the absence of tensile testing, hardness data alone cannot validate or challenge the Eurocode’s reduction factors with certainty. A more definitive assessment would require combined hardness and mechanical testing data under comparable welding conditions.

4.2. Characterisation of the HAZ

The extent of the HAZ was determined based on hardness testing conducted in accordance with Annex Q of the EN 1999-1-1 [33]. This methodology defines the boundary of the HAZ as the point at which the measured hardness reaches 90% or more of the base material hardness. Between this boundary and the weld centreline, the standard assumes a linear reduction in material strength, corresponding to the characteristic value defined in the code.

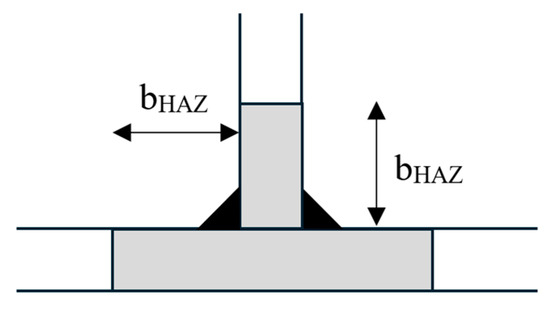

Furthermore, for T-shaped connections, EN 1999-1-1 [33] defines that the extent of the HAZ in the flange is measured in relation to the adjacent face of the web. Similarly, the extent of the HAZ in the web is measured in relation to the adjacent face of the flange, as shown in Figure 10. The EN 1999-1-1 [33] also makes the simplified assumption that a uniform reduction in the strength of the material has taken place from this point to the centre of the weld.

Figure 10.

Eurocode 9 methodology for determining the extent of the HAZ for T-shaped connections.

In accordance with this approach, the effective HAZ extent (bHAZ) was quantified for all tested fillet-welded T-connections. The results are categorised by welding process and summarised in Table 7 for DC-MIG-P welded specimens and in Table 8 for AC-MIG-P welded specimens.

Table 7.

Numerical characterisation of the HAZ extent for DC-MIG-P welded T-connections.

Table 8.

Numerical characterisation of the HAZ extent for AC-MIG-P welded T-connections.

For DC-MIG-P welded specimens, the average measured HAZ extent ranged from 11.16 mm to 13.72 mm, depending on the plate thickness and connection configuration. Specimens welded using the AC-MIG-P process exhibited narrower HAZs, with average extents ranging from 7.63 mm to 10.14 mm. These findings are consistent with expectations, as the DC process typically involves higher net heat input compared to AC, resulting in a broader thermal influence.

All measured extents fall below the corresponding normative limits specified in EN 1999-1-1 (either 15 mm or 22.5 mm, depending on plate thickness), indicating that the actual thermal softening is more localised than the standard conservatively assumes.

The amount of research on MIG-welded T-connections made from AW-6082-T6 alloy reported in the literature is limited. Duan et al. [69] conducted hardness tests on fillet-welded T-connections made of the AW-6082-T6 alloy with the use of the MIG welding process. The authors reported a softening-zone width of about 9 mm measured from the centre of the welding seam based on their hardness profiles. In comparison, the measurements presented in this paper indicate the extent of the HAZ to be 11.16–13.72 mm for DC-MIG-P and 7.63–10.14 mm for the AC-MIG-P process. However, it should be noted that the hardness test plan and methodology for determining the extent of the HAZ used in this paper differed slightly from those reported in [69].

Further research has been published on butt-welded specimens made from AW-6082-T6 alloy. Zhu et al. [70] conducted hardness measurements on butt-welded 6 mm thick AW-6082-T6 plates produced using pulsed MIG welding and reported that the HAZ extended approximately 9 mm from the weld centre. Naing et al. [71] investigated butt-welded specimens of the same alloy, using 4 mm thick plates that included repair welds. All specimens were welded using pulsed MIG at various frequencies, and the authors observed a consistent HAZ width of about 12 mm from the weld centre, regardless of welding frequency. Lundberg and Tjøstheim [72] examined butt-welded connections with plate thicknesses of 10, 16, 20, and 30 mm, all made from EN AW-6082-T6 and welded using MIG process. They reported HAZ widths ranging from approximately 20 mm to 25 mm.

A more detailed analysis of the hardness measurements performed in this study, including the influence of welding parameters and geometric configuration, is provided in the following section.

5. Summarised Discussion

5.1. Effect of Welding Process

A comparative assessment of the microstructural and macrostructural analyses for T-connections welded using DC-MIG-P and AC-MIG-P processes reveals distinct differences arising from variations in heat input and metal transfer properties. The DC-MIG-P process, being a more conventional approach, resulted in deeper penetration and more pronounced dilution. In specimens of 6 mm and 8 mm thickness, full penetration and clear recrystallisation within the HAZ were observed. The HAZ extents for the DC-MIG-P specimens typically ranged between 11 mm and 14 mm when measured according to the EN 1999-1-1 [33] approach as described in Section 4.2. In contrast, the AC-MIG-P process exhibited lower heat input, resulting in shallower penetration, limited recrystallisation, and narrower softened zones. The measured HAZ extents in these specimens ranged between 7 mm and 10 mm.

At the microstructural level, AC-MIG-P welds displayed a lower degree of dilution and more frequent appearance of internal porosity, although with fewer microcracks. This may be attributed to reduced thermal gradients and lower residual stresses. However, due to the shallower penetration, there is a higher risk of incomplete fusion and local strength deficiencies, particularly in thicker plates (10 mm). These trends are supported by hardness test results: in AC-MIG-P specimens, the recovery to base metal hardness occurred within 5–10 mm from the weld centre, while in DC-MIG-P specimens, this recovery was only observed beyond 10–15 mm.

Previous studies on 6xxx-series aluminium alloys have shown that pre-heating before MIG welding can significantly enlarge the heat-affected zone (HAZ). For example, an investigation on AW 6061 [73] reported that pre-heating increased the HAZ width from about 20 mm after the first bead to nearly 32 mm after the third bead, highlighting its influence on the thermal cycle and hardness distribution. Furthermore, due to the very high thermal conductivity of aluminium alloys, pre-heating is often required for thicknesses above 5 mm to prevent lack of penetration and cold joints.

5.2. Effect of Material Thickness

When welding parameters are held constant, increasing thickness generally reduces the HAZ extent because thicker plates extract heat more effectively (stronger heat-sink effect). Wider softened regions observed in some 10 mm specimens arise from parameter adjustments—primarily lower travel speed (higher heat input per unit length)—rather than from thickness per se.

For DC-MIG-P, the average HAZ extent is largest for 6 mm plates (13.72 mm) and decreases for 8 mm plates (11.65 mm). In the 10 mm series (~11.32 mm), the expected decrease does not continue because the process was run with reduced travel speed, which prolongs thermal exposure and offsets the heat-sink benefit. For AC-MIG-P, the trend is similar but clearer: 6 mm shows the widest HAZ (10.14 mm), 8 mm the narrowest (7.63 mm), while 10 mm increases slightly (9.51 mm) due to parameter changes and higher process sensitivity.

Hardness profiles are consistent with these observations: asymmetric softening in 8/10 mm connections is expected, with minima more often on the thinner (8 mm) side in AC welds (higher relative heat input), while DC minima depend on the specific parameter set. All measured HAZ extents remain well below the EC9 reference values, indicating that even the “wider” zones are process-driven and not a thickness-induced integrity issue.

5.3. Comparison with Eurocode 9

Eurocode 9 (EN 1999-1-1 [33]) provides conservative guidelines for estimating the extent of the heat-affected zone, defining its boundary as the location where hardness returns to at least 90% of the base material value. The standard [33] also makes the simplified assumption that a uniform reduction in the strength of the material occurs within the defined HAZ. Furthermore, different values of the HAZ extent are provided regarding the plate thicknesses of the welded connection. The HAZ extent of 15 mm is prescribed for T-shaped connections with a plate thickness equal to or less than 6 mm. For T-shaped connections with a plate thickness greater than 6 mm, but equal to or less than 12 mm, the prescribed HAZ extent is 22.5 mm.

Experimental results from this study reveal that the actual HAZ extents, measured via Vickers hardness testing, are consistently smaller than the Eurocode’s default values. In DC-MIG-P welded connections, measured HAZ extents ranged between 11.2 mm and 13.7 mm, while for AC-MIG-P, the range was 7.3 mm to 10.1 mm. These findings clearly indicate that modern pulsed MIG processes, especially those using alternating current, induce more localised thermal effects than the standard presumes.

It should also be noted that a series of tensile tests were conducted within the REAL-fit project [40,41] on welded EN AW-6082-T651 coupons. These tests showed that the strength reduction in the HAZ ranged from 40% to 54% for the 0.2% proof strength and from 22% to 32% for the ultimate tensile strength. According to EN 1999 [33], the expected strength reduction in the HAZ for this 6xxx-series alloy is 51% for the 0.2% proof strength and 38% for the ultimate tensile strength. Based on these values, the standard provides conservative estimates for the ultimate tensile strength in the HAZ, but not for the 0.2% proof strength. Although the results of these tensile tests are not presented in this paper, they will be reported in detail in future publications.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents the results of microstructural analysis and hardness testing carried out on fillet-welded T-connections made from the aluminium alloy EN AW-6082-T651. The investigation included 20 specimens with nominal plate thicknesses of 10 mm, 8 mm, and 6 mm, welded using both DC-MIG-P and AC-MIG-P processes. It should therefore be noted that the observations and conclusions drawn from this study regarding welded T-connections apply only to the specified alloy, plate thicknesses, and welding parameters used in this experimental programme.

In summary, AC-MIG-P offers better control over thermal input and may reduce structural distortion, yet DC-MIG-P provides more robust fusion and metallurgical continuity—especially vital in connections involving thicker material. The choice of welding process should therefore reflect a trade-off between thermal control and mechanical performance requirements.

AC-MIG-P maintained relatively narrow HAZ extents even in 10 mm plates—typically below 10 mm—demonstrating its efficiency in limiting thermal influence. However, this came at the expense of fusion quality, especially at the weld root and toe regions. This lack of fusion indicated that the AC-MIG-P welding process raises reasonable technical doubt about welding T-connections made from EN AW-6082-T651 plates thicker than 6 mm when using the parameters listed in Table 2. However, this does not rule out the potential use of this process for such applications, as it may still be possible to adjust the welding parameters to achieve welds of acceptable quality. In particular, it is advisable to minimise EN ratio and also apply larger degree of preheating, considering the limitations specified in EN 1011-4 [74]. DC-MIG-P appears more robust and reliable for thicker connections, while AC-MIG-P is advantageous for thin sections where reduced distortion is a priority.

As is evident, the AC-MIG-P process definitely provides better results for smaller thickness ranges. However, another issue to discuss is the degree of dilution, which is significantly lower in the AC-MIG-P process, resulting in fewer metallurgical problems related to critical Mg content in the hot short area. This means that, with a lower degree of dilution, the weld metal retains an Mg content above the critical level (3%), whereas in the DC-MIG-P process, due to greater dilution and penetration, the Mg content drops significantly, especially in base metals with lower Mg content. Therefore, while lack of fusion is a technical aspect that must be addressed, it is not the only issue to consider when evaluating the AC-MIG-P process.

The strict design provisions of EN 1999-1-1 [33] regarding the extent of the HAZ and the reduction of mechanical properties within this zone limit the application of welded aluminium members, consequently restricting the broader use of aluminium alloys in structural engineering. Results related to the HAZ extent indicate that the Eurocode provisions may be somewhat conservative for pulsed welding processes, and that adopting more precise, process-specific HAZ characterisations could lead to more optimised connection design and its structural behaviour. However, the results in Table 7 and Table 8 show that the measured HAZ extents can vary considerably, even though all specimens were made from the same alloy and welded using only two sets of parameters. Given the variability in welding procedures, connection geometry, and execution quality in practice, it must be emphasised that a much larger dataset on HAZ extents in welded aluminium connections is required before the codified values in EN 1999-1-1 [33] can be reliably assessed for conservatism. Consequently, any normative revision must be supported by broader experimental validation across various configurations.

The complexity of this task arises from the wide variety of aluminium alloys available on the market, the diversity of welding procedures, and the use of different filler metals. At the same time, this diversity offers substantial opportunities for further research. Despite these challenges, the results presented in this article provide a meaningful contribution towards harmonising design standards for aluminium structures with modern welding processes, thereby enabling more efficient and reliable structural design.

However, as the development of new waveform MIG welding processes is significantly introduced in modern welded structures production, it is clear that further research is necessary to investigate the influence of this particular process on the behaviour and properties of welded connections and joints. This also shows that the design approach should be aligned with the specific issues of such processes to expose the complete production potential, especially from the aspect of welding automation and robotisation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, D.S.; methodology, D.S. and A.V.; software, D.L., M.Š., A.V. and I.Č.; validation, I.G., D.L., and D.S.; formal analysis, D.L., A.V. and I.Č.; investigation, D.L., M.Š., A.V. and I.Č.; resources, D.S., I.G., and D.L.; data curation, D.S., I.G., and D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S. and A.V.; writing—review and editing, All; visualisation, D.L., I.Č., A.V. and M.Š.; supervision, D.L., I.G. and D.S.; project administration, D.S.; funding acquisition, D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partly supported by the Croatian Science Foundation under the project number HRZZ-IP-2022-10-9298 (REAL-fit: Reliable design methods for aluminium structures fit for the future requirements, project leader: Davor Skejić).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the company Metal Product, Zagreb, Croatia, for their assistance and support in organizing the experimental research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Boko, I.; Skejić, D.; Torić, N. Aluminium Structures; University of Split, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Geodesy: Split, Croatia, 2017. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Skejić, D.; Boko, I.; Torić, N. Aluminium as a material for modern structures. Građevinar 2015, 67, 1075–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajor, T.; Kawałek, A.; Berski, S.; Jurczak, H.; Borowski, J. Analysis of the Extrusion Process of Aluminium Alloy Profile. Materials 2022, 15, 8311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgantzia, E.; Gkantou, M.; Kamaris, G.S. Aluminium alloys as structural material: A review of research. Eng. Struct. 2021, 227, 111372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuelin, W.; Guoqun, Z.; Lu, S.; Xiaowei, W.; Dejin, W.; Linlin, L. Effects of welding angle on microstructure and mechanical properties of longitudinal weld in 6063 aluminum alloy extrusion profiles. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 17, 756–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunaziv, I.; Tomstad, A.J.; Kvam-Langelandsvik, G.; Eriksson, M. A through-process modelling approach of aluminium heat-affected zone softening and weld joint performance. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 137, 4011–4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, E. Challenges in thermal welding of aluminium alloys. World J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 6, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Hu, H.; Tang, X.; Ma, X.; Wang, X. The effect of TIG welding heat input on the deformation of a thin bending plate and its weld zone. Coatings 2023, 13, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabry, I.; Hewidy, A.M.; Naseri, M.; Mourad, A.H.I. Optimization of process parameters of metal inert gas welding process on aluminum alloy 6063 pipes using Taguchi-TOPSIS approach. J. Alloys Metall. Syst. 2024, 7, 100085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1090-3: 2019; Execution of Steel and Aluminium Structures—Part 3: Technical Requirements for Aluminium Structures. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Dada, M.; Popoola, P. Recent advances in joining technologies of aluminum alloys: A review. Discov. Mater. 2024, 4, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habba, M.I.A.; Alsaleh, N.A.; Badran, T.E.; El-Sayed Seleman, M.M.; Ataya, S.; El-Nikhaily, A.E.; Abdul-Latif, A.; Ahmed, M.M.Z. Comparative Study of FSW, MIG, and TIG Welding of AA5083-H111 Based on the Evaluation of Welded Joints and Economic Aspect. Materials 2023, 16, 5124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramji, B.R.; Bharathi, V.; Swamy, N.P. Characterization of TIG and MIG welded aluminium 6063 alloys. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 8895–8899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraresi, V.A.; Figueiredo, K.M.; Ong, T.H. Metal transfer in the aluminum gas metal arc welding. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2003, 25, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Garašić, I.; Štefok, M.; Jurica, M.; Skejić, D.; Perić, M. Mechanical Properties Analysis of WAAM Produced Wall Made from 6063 Alloy Using AC MIG Process. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Xu, M.; Huang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, W.; Jin, L. Stability and heat input controllability of two different modulations for double-pulse MIG welding. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warinsiriruk, E.; Greebmalai, J.; Sangsuriyun, M. Effect of double pulse MIG welding on porosity formation on aluminium 5083 fillet joint. MATEC Web Conf. 2019, 269, 01002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Cao, S.; Li, L.; Guo, P.; Liu, K. Effect of welding current on morphology and microstructure of Al alloy T-joint in double-pulsed MIG welding. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2015, 25, 3204–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Rhee, S.; Kang, M.J.; Kim, D.C. Joining of steel to aluminum alloy by AC pulse MIG welding. Mater. Trans. 2009, 50, 2314–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ro, C.S.; Kim, K.H.; Bang, H.S.; Yoon, H.S. Joint properties of aluminum alloy and galvanized steel by AC pulse MIG braze welding. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.H.; Choi, S.; Yoon, H.S.; Bang, H.S. Weldability of aluminum alloy and hot dip galvanized steel by AC pulse MIG brazing. J. Weld. Join. 2021, 39, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Kim, H.; Lee, I.; Cho, J. Basic research of directed energy deposition for aluminum 4043 alloys using pulsed variable polarity gas metal arc welding. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2024, 25, 1475–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chung, H. Numerical simulation of droplet transfer behaviour in variable polarity gas metal arc welding. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2017, 111, 1129–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, A.; Chung, H. Numerical simulation of arc, metal transfer and its impingement on weld pool in variable polarity gas metal arc welding. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 64, 1529–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, X.; Wang, Z.; Gardner, L. Full-range stress–strain curves for aluminum alloys. J. Struct. Eng. 2021, 147, 04021060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokšanović, T.; Džeba, I.; Markulak, D. Variability of structural aluminium alloys mechanical properties. Struct. Saf. 2017, 67, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skejić, D.; Dokšanović, T.; Čudina, I.; Mazzolani, F.M. The basis for reliability-based mechanical properties of structural aluminium alloys. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, A.; Souissi, M.; Zhou, M.; Assadi, H. Gradient-Based Calibration of a Precipitation Hardening Model for 6xxx Series Aluminium Alloys. Metals 2025, 15, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Jayaganthan, R.; Ruan, D.; Gupta, N.K.; Jones, N.; Velmurugan, R. Energy absorption and dynamic behaviour of 6xxx series aluminium alloys: A review. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2023, 172, 104397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruah, M.; Borah, A. Processing and precipitation strengthening of 6xxx series aluminium alloys: A review. Int. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 1, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Ramacharyulu, D.A.; Kumar, N.; Saxena, K.K.; Eldin, S.M. Change in the structure and mechanical properties of Al-Mg-Si alloys caused by the addition of other elements: A comprehensive review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 1764–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathers, G. The Welding of Aluminium and Its Alloys; Woodhead Publishing Limited: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- EN 1999-1-1: 2023; Eurocode 9–Design of Aluminium Structures–Part 1-1: General Rules. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- Zhu, J.H.; Young, B. Aluminum alloy tubular columns—Part I: Finite element modeling and test verification. Thin-Walled Struct. 2006, 44, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skejić, D.; Žuvelek, V.; Valčić, A. Parametric numerical study of welded aluminium beam-to-column joints. Buildings 2023, 13, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, H.N.; Clark, J.W.; Brungraber, R.J. Design of Welded Aluminum Structures. J. Struct. Div. 1960, 86, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzolani, F.M. Structural imperfections in aluminum welded joints. Alum. Rev. 1974, 431. [Google Scholar]

- Soetens, F. Welded connections in aluminium alloy structures. Heron 1987, 32, 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Moen, L.A.; Hopperstad, O.S.; Langseth, M. Rotational Capacity of Aluminum Beams under Moment Gradient. I: Experiments. J. Struct. Eng. 1999, 125, 910–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REAL-Fit Project: Reliable Design Methods for Aluminium Structures Fit for Future Requirements (HRZZ-IP-2022-10-9298). Available online: https://real-fit.grad.hr/ (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Skejić, D.; Valčić, A.; Čudina, I.; Garašić, I.; Dokšanović, T. A Roadmap for the Reliable Design of Aluminium Structures Fit for Future Requirements—The REAL-Fit Project. Buildings 2025, 15, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASM Handbook. Aluminum Science and Technology; Anderson, K., Weritz, J., Kaufman, J.G., Eds.; ASM International: Metals Park, OH, USA, 2018; Volume 2A. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, J.G. Introduction to Aluminum Alloys and Tempers; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nazemi, N.; Ghrib, F. Strength characteristics of heat-affected zones in welded aluminum connections. J. Eng. Mech. 2019, 145, 04019103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1011-1:2009; Welding—Recommendations for Welding of Metallic Materials—Part 1: General Guidance for Arc Welding. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2009.

- ISO/TR 18491: 2015; Welding and Allied Processes—Guidelines for Measurement of Welding Energies. International Organization for Standardization. ISO Central Secretariat: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- ISO/IEC 17025: 2017; General Requirements for the Competence of Testing and Calibration Laboratories. International Organization for Standardization. ISO Central Secretariat: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- EN ISO 4063: 2023; Welding, Brazing, Soldering and Cutting—Nomenclature of Processes and Reference Numbers. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- EN ISO 18273: 2015; Welding Consumables—Wire Electrodes, Wires and Rods for Welding of Aluminium and aluminium Alloys—Classification. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2015.

- EN ISO 14175: 2008; Welding Consumables—Gases and Gas Mixtures for Fusion Welding and Allied Processes. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2008.

- EN ISO 17637: 2016; Non-Destructive Testing of Welds—Visual Testing of Fusion-Welded Joints. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- EN ISO 10042:2018; Welding—Arc-Welded Joints in Aluminium and Its Alloys—Quality Levels for Imperfections. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

- Geels, K.; Fowler, D.B.; Kopp, W.U.; Rückert, M. Metallographic and Materialographic Specimen Preparation, Light Microscopy, Image Analysis and Hardness Testing; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM E3–11; ASTM Standard Guide for Preparation of Metallographic Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM E 340; ASTM Standard Test Method for Macroetching Metals and Alloys. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2006.

- Stevens, R.H. Aluminum Alloys: Metallographic Techniques and Microstructures. In ASM Handbook Metallography and Microstructures, 9th ed.; Fahrenholz-Mann, S., Sanders, B., Seuffert, M., Kalman, G., Henry, S., Braddock, R., Eds.; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 1998; Volume 9, pp. 707–804. [Google Scholar]

- Vovk, V. Microvision Suite Computer Program. Available online: https://apps.microsoft.com/detail/9ndjq2kqc54t?hl (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- ASTM E112: 2025; Standard Test Methods for Determining Average Grain Size. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2025.

- ISO 5817:2023; Welding—Fusion-Welded Joints in Steel, Nickel, Titanium and Their Alloys (Beam Welding Excluded)—Quality Levels for Imperfections. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- Ardika, R.D.; Triyono, T.; Triyono, M.N. A review porosity in aluminum welding. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2021, 33, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, A.M.; Samuel, E.; Songmene, V.; Samuel, F.H. A Review on Porosity Formation in Aluminum-Based Alloys. Materials 2023, 16, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6520-1:2007; Welding and Allied Processes—Classification of Geometric Imperfections in Metallic Materials. International Organization for Standardization. ISO Central Secretariat: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Anyalebechi, P.A. Hydrogen Solubility in Liquid and Solid Pure Aluminum—Critical Review of Measurement Methodologies and Reported Values. Mater. Sci. Appl. 2022, 13, 158–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huanga, Y.; Yuana, Y.; Yanga, L.; Zhangb, Z.; Houa, S. A study on porosity in gas tungsten arc welded aluminum alloys using spectral analysis. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 57, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6507-1: 2023; Metallic Materials—Vickers Hardness Test, Part 1: Test Method. International Organization for Standardization ISO Central Secretariat: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- EN ISO 9015-1: 2011; Destructive Tests on Welds in Metallic Materials—Hardness Testing—Part 1: Hardness Test on Arc Welded Joints. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- Nazemi, N. Identification of the Mechanical Properties in the Heat-Affected Zone of Aluminum Welded Structures. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Windsor, Windsor, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Aune, S.; Morin, D.; Langseth, M.; Hopperstad, O.S.; Clausen, A.H. Modelling of welded aluminium connections in large-scale analyses. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 201, 112034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Yang, S.; Gu, J.; Xiong, Q.; Wang, Y. Study on microstructure and fatigue damage mechanism of 6082 aluminum alloy T-type metal inert gas (MIG) welded joint. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Yang, S.; Bai, Y.; Fan, C. Microstructure and fatigue damage mechanism of 6082-T6 aluminium alloy welded joint. Mater. Res. Express 2021, 8, 056505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naing, T.H.; Muangjunburee, P. Mechanical properties of repair welds for aluminum alloy 6082-T6 by pulsed MIG welding process. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 2021, 43, 1694–1700. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.; Tjøstheim, N.J. Hydro Report RDK-14-002-01: Mechanical Properties in the Heat-Affected Zone of Welded EN AW-6082 T6; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Novakova, I.; Moravec, J.; Novak, J.; Solfronk, P. Influence of Preheating Temperature on Changes in Properties in the HAZ during Multipass MIG Welding of Alloy AW 6061 and Possibilities of Their Restoration. Metals 2021, 11, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1011-4: 2000; Welding—Recommendations for Welding of Metallic Materials—Part 4: Arc Welding of Aluminium and Aluminium Alloys. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2000.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).