Abstract

This study investigates the desulfurization and smelting reduction processes of zinc leaching residue and analyzes the kinetics of the desulfurization and smelting reduction processes of zinc leaching residue. The results showed that, when the desulfurization temperature was 1623 K and the desulfurization time was 27 min, the desulfurization rate of zinc leaching residue was over 95%. When the melting reduction temperature is 1773 K and the melting reduction time is 40 min, the zinc reduction rate is over 98%, and when the melting reduction time is 100 min, the iron reduction rate is over 98%. The desulfurization process of zinc leaching residue is jointly controlled by mass transfer diffusion and interfacial chemical reactions (1373~1623 K), and the kinetic equation is [1 − (1 − x)1/3]2 = 21,897.11 × exp[−202.881/RT]t. The smelting reduction process of desulfurization slag is jointly controlled by interfacial chemical reactions and mass transfer diffusion (1673~1773 K). The kinetic equation of the zinc smelting reduction process is 1 − 2R/3 − (1 − R)2/3 = 4185.03 × exp[−194.78/RT]t. The kinetic equation of the iron smelting reduction process is 1 − (1 − R)1/3 = 8672.22 × exp[−207.13/RT]t.

1. Introduction

At present, more than 85% of zinc smelters in the world adopt the wet zinc smelting process. During the wet zinc smelting process, a large amount of zinc leaching residue is inevitably generated during the leaching stage [1]. Zinc leaching residue contains various valuable metals. As shown in Table 1, almost all zinc leaching residues contain a high amount of zinc and iron [2]. The increasing amount of zinc leaching residue not only causes a large amount of valuable metal waste, such as Fe, Zn, and Pb, but also results in a significant waste of land resources, and safety hazards such as dam collapse also arise [3].

Table 1.

Valuable metal components and contents in zinc leaching residue from domestic zinc smelters [2].

This study proposes the smelting reduction treatment of zinc leaching residue. In the zinc leaching residue recovery process, in terms of wet metallurgy, because of relatively high iron content in the zinc sulfide ore, a significant portion of zinc is unavoidably converted into zinc ferrite [4,5]. Zeqiang X et al. [6] used CaO to degrade the structure of zinc ferrite, and then the ammonia leaching method was applied to recover zinc; Zhang C et al. [7] adopted the sulfur dioxide reduction leaching process instead of the traditional hot-acid leaching method. In addition, multiple studies have replaced traditional processes with innovative methods to recover valuable metals from zinc leaching slag, in order to improve recovery efficiency [8,9,10]. Huimin X et al. [11] developed an ultrasonic-assisted one-stage leaching process and compared it with a two-stage leaching process under conventional conditions. In terms of pyrometallurgy, the applications and the development of pyrometallurgy are impeded by some drawbacks like high energy and resource consumption, expensive operating costs, and serious air pollution [12,13,14]. However, with the continuous improvement in process optimization and exhaust gas treatment technology [15], the pyrometallurgical process is still widely used as a zinc slag treatment technology. Ao Z et al. [16] investigated the industrial application of this process, and the material balance was analyzed using data collected by field sampling and quantitative analysis; Zhang Z et al. [17] proposed a novel technology for the recovery of zinc from the zinc leaching residue by the bottom-blown reduction process. The effects of reduction temperature, reduction time, coal rate, and lime addition on the metal content in the slag and the volatilization rate of lead and zinc during reduction were evaluated. In other aspects, Yunpeng D et al. [18] studied the recovery of zinc (Zn) and silver (Ag) from ZLR wastes from zinc hydrometallurgy workshops using water leaching followed by flotation. Liu J et al. [19] studied the effect of key parameters, i.e., grinding fineness, dosage of collectors, and dosage of sodium chloride on the flotation performance. Zeng W et al. [20] studied the process of treating zinc leaching residue by cavitation and dissociation technology. Through the process optimization test, the control technology of zinc leaching residue monomer is formed.

This study proposes the smelting reduction treatment of zinc slag while extracting metallic iron and zinc elements together. The aim of this study is to analyze the effects of reduction temperature, reduction time, and other factors on the desulfurization and smelting reduction processes of zinc leaching residue; to determine the applicable kinetic model; and to provide basic data for the technology of collaborative extraction of iron and zinc in the smelting reduction treatment of zinc leaching residue.

2. Materials and Methods

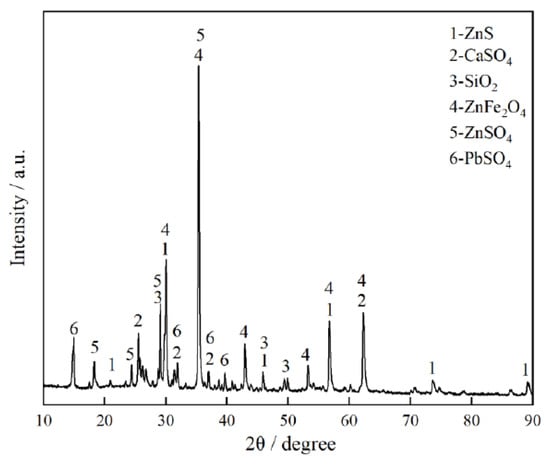

The zinc leaching residue used in this study comes from Henan, China. Its main chemical composition and XRD pattern (BRUKER, Billerica, MA, USA) are shown in Table 2 and Figure 1, respectively. Table 2 shows that the iron content in the zinc leaching residue is the highest, followed by zinc. Figure 1 shows that iron in the zinc leaching residue mainly exists in the form of ZnFe2O4; zinc mainly exists in three forms: ZnSO4, ZnFe2O4, and ZnS; silicon mainly exists in the form of SiO2; lead mainly exists in the form of PbSO4, and calcium mainly exists in the form of CaSO4.

Table 2.

Main chemical components of zinc leaching residue.

Figure 1.

XRD pattern of zinc leaching residue.

The reducing agent is coke. The main components of coke are shown in Table 3. The slag-forming agent used is CaO (analytical grade, Tianjin Yongda Ltd., Tianjin, China). By adding CaO, the alkalinity of the slag is adjusted; the melting point of the slag system is lowered, and the separation of slag and metal is promoted.

Table 3.

Main components of coke.

The experimental parameters for desulfurization of zinc leaching residue are shown in Table 4. The ground zinc leaching residue (50 g) was thoroughly mixed with coke and calcium oxide in proportion and placed in a resistance furnace (Northeastern University, Shenyang, Liaoning, China) to raise the temperature to the preset experimental temperature. After the reaction was completed, the samples obtained from desulfurization were analyzed.

Table 4.

Zinc leaching residue desulfurization parameters.

In the pre-reduction experiment, we investigated the effect of 0.6–1.0 W (CaO)/W (SiO2) on melt reduction. When the calcium silicon ratio was 0.6–0.9, the reduction rates of iron and zinc gradually increased with the increase in calcium oxide addition. When W (CaO)/W (SiO2) exceeded 0.9, the reduction rates of iron and zinc changed weakly, so we chose W(CaO)/W(SiO2) = 0.9. The main parameters of desulfurization slag smelting reduction are shown in Table 5. A total of 180g of uniformly mixed desulfurization slag, calcium oxide, coke, and other raw materials and reagents are taken for the smelting reduction reaction.

Table 5.

Melting reduction parameters of desulfurization slag.

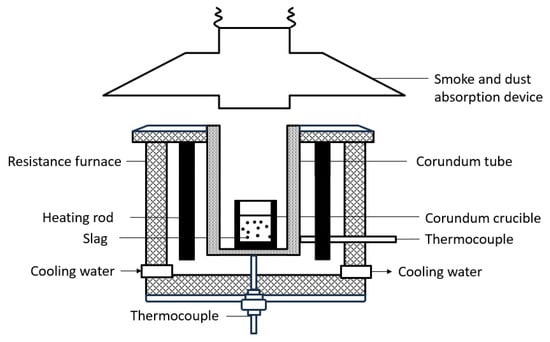

The equipment used in this study is a resistance furnace, as shown in Figure 2. The size of the reaction vessel used in the experiment is a corundum crucible with a height of 120 mm and an inner diameter of 48 mm. The Pt− 13 pct Rh/Pt thermocouple at the bottom of the crucible is used to measure the temperature of the slag. The temperature control program of the computer can control the temperature of the electric furnace and adjust the heating rate, with a temperature control accuracy of 1 °C.

Figure 2.

Experimental resistance furnace.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Desulfurization Process

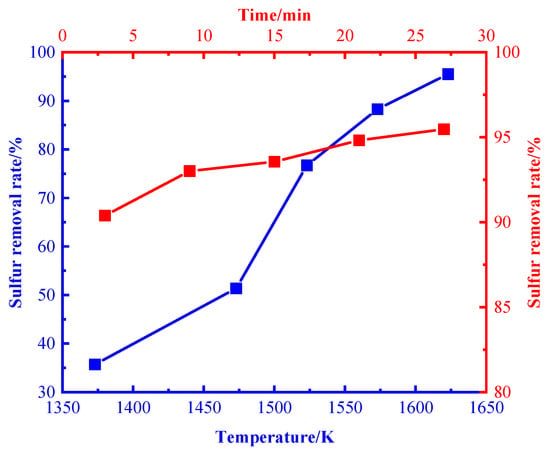

Figure 3 shows the variation of the desulfurization rate with temperature and time. It can be seen that the overall desulfurization rate increases with the increase in reaction temperature and time. The growth is relatively slow from 1373 K to 1473 K, and the desulfurization rate increases significantly with the increase in temperature from 1473 K to 1573 K at a desulfurization time of 27 min. When the temperature reaches 1623 K, the desulfurization rate is over 95%, which is consistent with the research results of Liu Yang et al. [21]. In this study, 1623 K was selected as the appropriate desulfurization temperature.

Figure 3.

Effect of temperature and time on desulfurization rate.

At a desulfurization temperature of 1623 K and a desulfurization time of 3–27 min, the desulfurization rate increased from 90.39% to 95.47%. In this study, 1623 K and 27 min were selected as the appropriate desulfurization temperature and time.

3.2. Smelting Reduction Process

Table 6 shows the main chemical components of desulfurization slag, from which the experimental carbon content and calcium oxide addition amount were calculated. Figure S1 shows the XRD pattern of desulfurization slag.

Table 6.

Main chemical components of desulfurization slag.

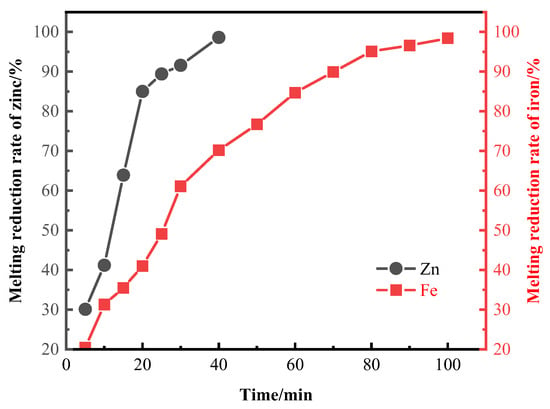

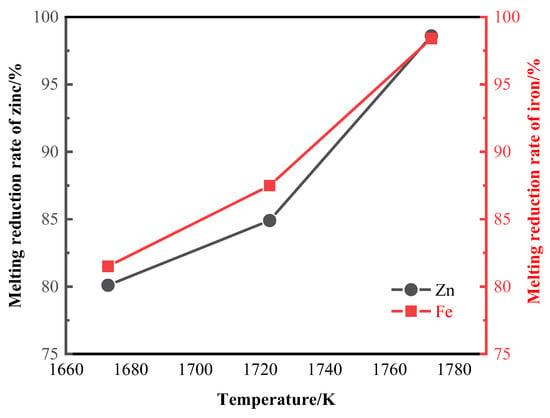

When the smelting reduction temperature is 1773 K, the relationship between the smelting reduction rate of zinc and iron and time is shown in Figure 4. Figure S2 shows the XRD patterns of slag at different temperatures after 100 minutes of reduction. Within 5–20 min, the smelting reduction rate of zinc increases from 30.1% to 85%, an increase of 54.9%. Within 20–40 min, the smelting reduction rate of zinc increases from 85% to 98.6%, an increase of 13.6%. From 0 to 40 min, the iron smelting reduction rate increased from 20.4% to 70.2%, an increase of 49.8%. From 40 to 100 min, the iron smelting reduction rate increased from 70.2% to 98.4%, an increase of 28.2%. At 100 min, the iron smelting reduction rate reached 98.4%, approaching the endpoint of the smelting reduction.

Figure 4.

Smelting reduction rates of zinc and iron at different melting reduction times.

When the zinc smelting reduction time is 40 min and the iron smelting reduction time is 100 min, the relationship between the smelting reduction rate of zinc and iron and temperature is shown in Figure 5. At 1673 K~1773 K, the zinc smelting reduction rate increases from 80.1% to 98.6%, an increase of 18.5%; the iron smelting reduction rate increased from 81.5% to 98.4%, an increase of 16.9%. This study selected 1773 K as the appropriate melting reduction temperature for zinc and iron.

Figure 5.

Smelting reduction rates of zinc and iron at different melting reduction temperatures.

3.3. Kinetics Analysis of Zinc Leaching Residue Desulfurization Process

The desulfurization process of zinc leaching residue is mainly the decomposition process of sulfate, and from a kinetic perspective, it should belong to the solid–gas reaction model. The construction of this model is based on the unreacted core model, assuming that the decomposition of sulfate is based on a quasi-steady state and only occurs at the interface of the unreacted core. During the decomposition of sulfate, the production of metal oxides is gradual, and according to the different order of metal oxide production, it is believed that the product layer has a layered phenomenon. As the decomposition reaction progresses, the thickness of the product layer (r0−rc) gradually increases, and the reaction core gradually shrinks. The SO2 and O2 produced by decomposition can diffuse outward through the gaps in the product layer.

If the desulfurization process of zinc leaching residue is controlled by interfacial chemical reactions, the reaction rate can be expressed by the Mckwan Equation (1):

If the desulfurization process of zinc leaching residue is controlled by gas-phase diffusion based on Fick’s first law, the reaction rate can be described by the Ginstling Equation (2) and the Jander Equation (3):

In the above equation, x is the desulfurization rate; k is the surface chemical reaction rate constant, and t is the desulfurization time.

Calculate k at different temperatures based on the fitting results and determine the activation energy E and correlation coefficient A (1373~1723K) of the desulfurization reaction using the Arrhenius empirical equation.

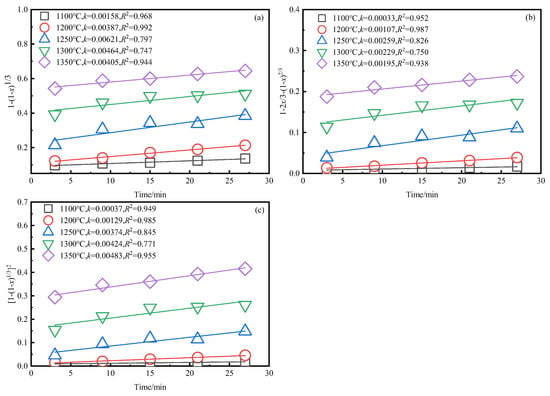

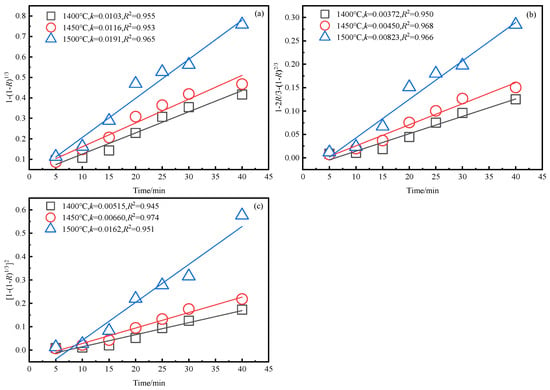

Based on the exploration of desulfurization process in Section 3.1, at the appropriate desulfurization temperature (1623 K), as shown in Figure 6, the best linear correlation was obtained:, with a correlation coefficient of 0.955 and high credibility. According to the Arrhenius empirical equation, an lnk−1/T relationship diagram was drawn, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Relationship between reaction rate equation and time at different temperatures. (a) . (b) . (c) .

Figure 7.

Arrhenius diagram of desulfurization process.

The slope of the fitted line shown in Figure 7 is −24,402.31. According to the Arrhenius equation, the activation energy of the reaction in the desulfurization process of zinc leaching residue is 202.881 kJ·mol−1. Therefore, the kinetic equation of the desulfurization process of zinc leaching residue can be simply expressed as follows:

For general chemical reactions, according to reference [22], as shown in Table 7, there are the following criteria:

Table 7.

Criteria for determining control steps.

The desulfurization process of zinc leaching residue used in this study is jointly controlled by interfacial chemical reactions and diffusion mass transfer.

3.4. Kinetics Analysis of Smelting Reduction Process

The smelting reduction process involves multiphase reactions, including solid–liquid reactions, solid–gas reactions, and liquid–liquid reactions, but the main reaction is the solid–liquid reaction. Solid–liquid reaction is the slowest operation and reaction rate control process; using the solid–liquid (gas) reaction model, the smelting reduction process can be expressed as follows:

① Fe3+, Fe2+, and Zn2+ in the slag diffuse towards the slag carbon reaction interface.

② Interface chemical reaction occurs, where Fe3+, Fe2+, Zn2+, CO2 react with solid carbon.

③ Products such as zinc vapor and CO undergo growth, polymerization, and rupture to diffuse outward from the reaction interface.

The expression for the reaction rate in the smelting reduction process is the same as in Section 3.3, where the desulfurization rate x corresponds to the reduction rate R; k is the surface chemical reaction rate constant, and t is the reduction time.

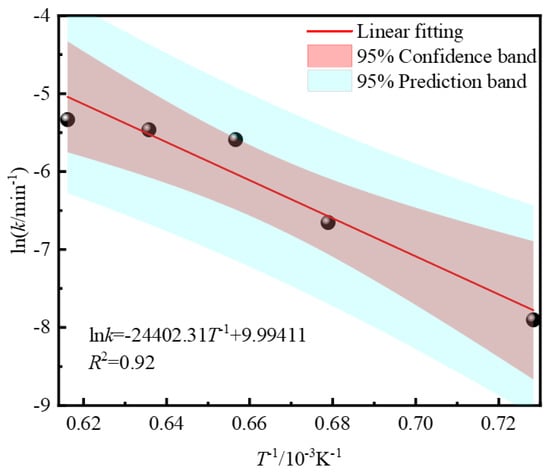

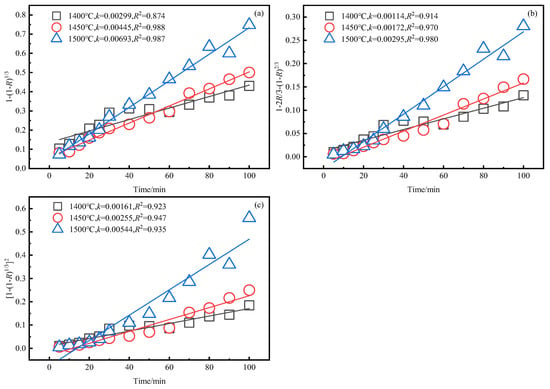

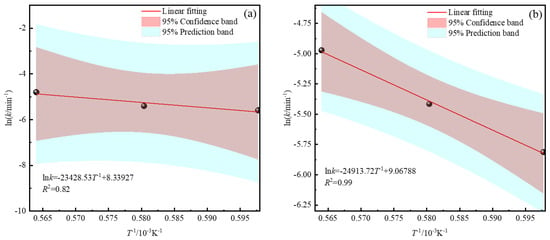

The kinetic results of zinc and iron reduction were obtained using the method described in Section 3.3, as shown in Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Figure 8.

Relationship between reaction rate equation of iron and time at different temperatures. (a) . (b) . (c) .

Figure 9.

Relationship between reaction rate equation of zinc and time at different temperatures. (a) . (b) . (c) .

Figure 10.

Arrhenius diagram of the smelting reduction process (a) Zinc smelting reduction process. (b) Iron smelting reduction process.

According to the Arrhenius equation and Figure 10a, the slope of the fitted line is −23,428.53; the activation energy of the zinc smelting reduction process is calculated to be 194.78 kJ·mol−1, and the kinetic equation of the zinc smelting reduction process can be simply expressed as follows:

Based on the activation energy results, the zinc smelting reduction process should belong to mixed control. Hou et al. [23] suggests that zinc is controlled by interfacial chemical reactions in the initial stage of smelting reduction and by diffusion mass transfer in the second stage, which is consistent with the experimental results in this paper.

According to the Arrhenius equation and Figure 10b, the slope of the fitted line is −24,913.72; the activation energy of the zinc smelting reduction process is calculated to be 207.13 kJ·mol−1, and the kinetic equation of the iron smelting reduction process can be simply expressed as follows:

According to the activation energy results, the iron smelting reduction process is jointly controlled by interfacial chemical reactions and diffusion. Sasaki Kang et al. [24] believe that the iron smelting reduction process is controlled by the gasification reaction of carbon (i.e., indirect reduction of carbon). The experimental results of Zhou Longwen [25] show that the iron smelting reduction process is jointly controlled by interfacial chemical reactions and diffusion mass transfer. Based on previous research, this study used some empirical formulas, and the results showed that the iron smelting reduction process is jointly controlled by interfacial chemical reactions and diffusion mass transfer.

4. Conclusions

(1) This study investigated the desulfurization and smelting reduction processes of zinc leaching residue and found that the desulfurization conditions for zinc leaching residue were 1623K. When the desulfurization time was 27 min, the desulfurization rate was over 95%. The melting reduction conditions for desulfurization slag are 1773 K with a W(CaO)/W(SiO2) ratio of 0.9. When the melting reduction time is 40 min, the zinc melting reduction rate is over 98%. When the melting reduction time is 100 min, the iron melting reduction rate is over 98%. According to Table S1, it can be seen that the final product is pig iron, with an iron content of 93.86%, a carbon content of 3.97%, and sulfur and phosphorus contents of 0.03% and 0.09%, respectively. According to Table S2, it can be seen that recycled pig iron can be used in steelmaking.

(2) This study analyzed the kinetics of the zinc leaching residue desulfurization process and the smelting reduction process. The desulfurization process mainly involves gas–solid reactions, which follow the gas–solid reaction model and are jointly controlled by mass transfer diffusion and interfacial chemical reactions. The smelting reduction process of desulfurization slag mainly involves liquid–solid reactions, following the liquid–solid reaction model. The smelting reduction process of zinc and iron is jointly controlled by mass transfer diffusion and interfacial chemical reactions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/met15121351/s1, Figure S1: XRD pattern of desulfurization slag; Figure S2: XRD patterns of slag at different temperatures after 100 minutes of reduction; Table S1: Main components of the recycled metals; Table S2: National pig iron standards.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Z.W. and M.Z.; methodology: Z.W.; software: Z.W. and M.Z.; vali dation: Z.W. and Y.W.; formal analysis: M.Z.; investigation: Z.W. and X.D.; resources: Y.W.; data curation: Y.W. and X.D.; writing—original draft preparation: Z.W.; writing—review and editing: Q.Z.; visualization: X.D.; supervision: Q.Z.; project administration: Q.Z.; funding acquisition: Q.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52174332.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ismael, M.R.C.; Carvalho, J.M.R. Iron recovery from sulphate leach liquors in zinc hydrometallurgy. Miner. Eng. 2003, 16, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-Y.; Gao, W.-C.; Wen, J.-K.; Gan, Y.-G.; Wu, B.; Shang, H. Research progress on valuable metal recovery and comprehensive utilization from zinc leaching residue. Chin. J. Eng. 2020, 42, 1400–1410. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, S. Design of Side Blowing Melting Furnace for Zinc Leaching Residue. Nonferrous Metall. Equip. 2020, 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Graydon, J.W.; Kirk, D.W. The mechanism of ferrite formation from iron sulfides during zinc roasting. Metall. Trans. B 1988, 19, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balarini, J.C.; Polli, L.D.O.; Miranda, T.L.S.; Castro, R.M.Z.D.; Salum, A. Importance of roasted sulphide concentrates characterization in the hydrometallurgical extraction of zinc. Miner. Eng. 2008, 21, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Jiang, T.; Chen, F.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S.; Yang, L. Phase transformation and zinc extraction from zinc ferrite by calcium roasting and ammonia leaching process. Crystals 2022, 12, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, A.; Jiang, H.; Deng, Y. Magnetic seed-assisted iron recovery from the reductive leaching solution in hydrometallurgical process. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2019, 72, 2591–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Peng, B.; Liang, Y.; Chai, L.; Wang, Q.; Li, Q.; Hu, M. Recovery of valuable metals from zinc leaching residue by sulfate roasting and water leaching. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2017, 27, 1180–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Ke, Y.; Luo, Y.; Min, X.; Peng, C.; Li, Y. A novel leaching process of zinc ferrite and its application in the treatment of zinc leaching residue. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2738, 012027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.J.; Chen, N.C.; Zhong, X.P.; Gao, J.; Lang, Y.X.; Wang, Z.F.; Liu, C.M.; Wu, Z.Y. Factors on leaching zinc and copper from zinc leach residue. Key Eng. Mater. 2014, 633, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Xiao, X.; Guo, Z.; Li, S. One-stage ultrasonic-assisted calcium chloride leaching of lead from zinc leaching residue. Chem. Eng. Process.—Process Intensif. 2022, 176, 108941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, K.H.; Chang, M.B.; Chang, S.H. Measurement of atmospheric PCDD/F and PCB distributions in the vicinity area of Waelz plant during different operating stages. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 391, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, P.C.; Chi, K.H.; Chen, M.L.; Chang, M.B. Characteristics of dioxin emissions from a Waelz plant with acid and basic kiln mode. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 201–202, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bese, A.V.; Borulu, N.; Copur, M.; Colak, S.; Ata, N.O. Optimization of dissolution of metals from Waelz sintering waste (WSW) by hydrochloric acid solutions. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 162, 718–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Ge, Z.; Bo, W. Application of oxygen-enriched side-blowing technology in treating zinc leaching residue in China. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2738, 012023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Xia, L.; Liu, Z. Co-smelting process of Pb concentrate and Zn leaching residues with oxygen-rich side blowing furnaces: Industrial application and material balance. JOM 2023, 75, 5833–5846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, W.; Zhan, J.; Li, G.; Zhao, Z.; Hwang, J.Y. A novel technology for the recovery of zinc from the zinc leaching residue by the bottom-blown reduction. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Rev. 2020, 42, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Tong, X.; Xie, X.; Zhang, W.; Yang, H.; Song, Q. Recovery of zinc and silver from zinc acid-leaching residues with reduction of their environmental impact using a novel water leaching flotation process. Minerals 2021, 11, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wen, M.S.; Wu, D.D. Recovery of silver from zinc leach residue by flotation. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 1792, 1041–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Hu, X.; Yan, Y.; Chen, B.; Chen, Y.; Tang, C.; Yang, J. Study on the cavitation and dissociation of sulfur from zinc leaching residue. JOM 2024, 76, 1394–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tan, J.; Yin, Z.; Liu, C.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, P.; Liao, D.; Wang, X. Roasting pretreatment of zinc precipitation slag and zinc leaching residue in wet zinc smelting. Chin. J. Nonferrous Met. 2016, 26, 213–216. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, L.-K.; Che, Y.-C. Metallurgical Thermodynamics and Dynamics; Northeast Institute of Technology Press: Shenyang, China, 1985; pp. 158–182. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, X.; Chou, K.C.; Zhao, B. Reduction kinetics of lead-rich slag with carbon in the temperature range of 1073 to 1473 K. J. Min. Metall. Sect. B Metall. 2013, 49, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasushi, S.; Yinhe, S. Study on the kinetics of reduction of molten iron oxide with solid carbon. Trans. Iron Steel Inst. Jpn. 1978, 64, 1797–1799. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.-W. Experimental Study on the Kinetics of Reduction of Feo Containing Slag; Northeastern University: Shenyang, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).