Theoretical Prediction of Yield Strength in Co(1-x-y)CryNix Medium-Entropy Alloys: Integrated Solid Solution and Grain Boundary Strengthening

Abstract

1. Introduction

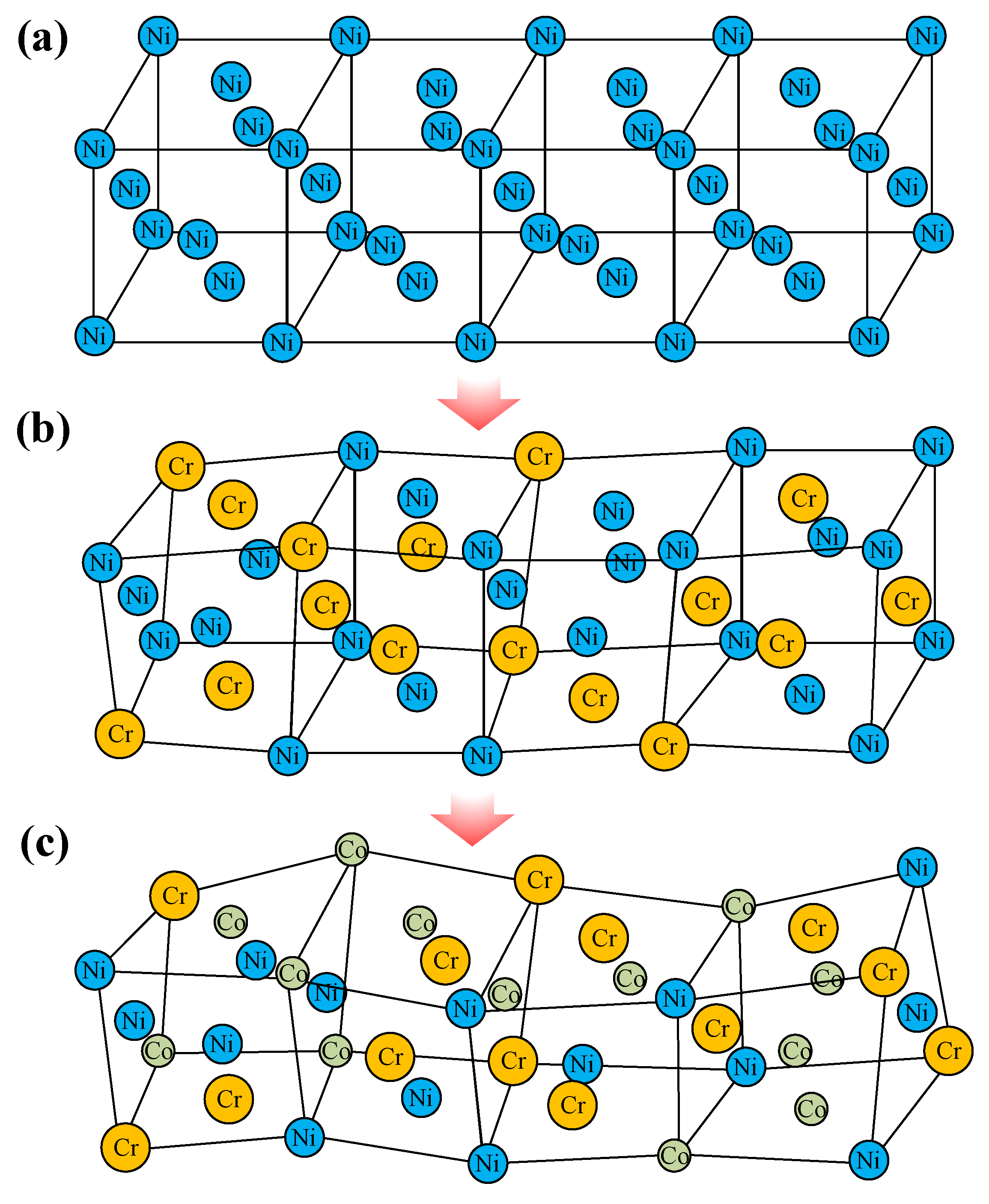

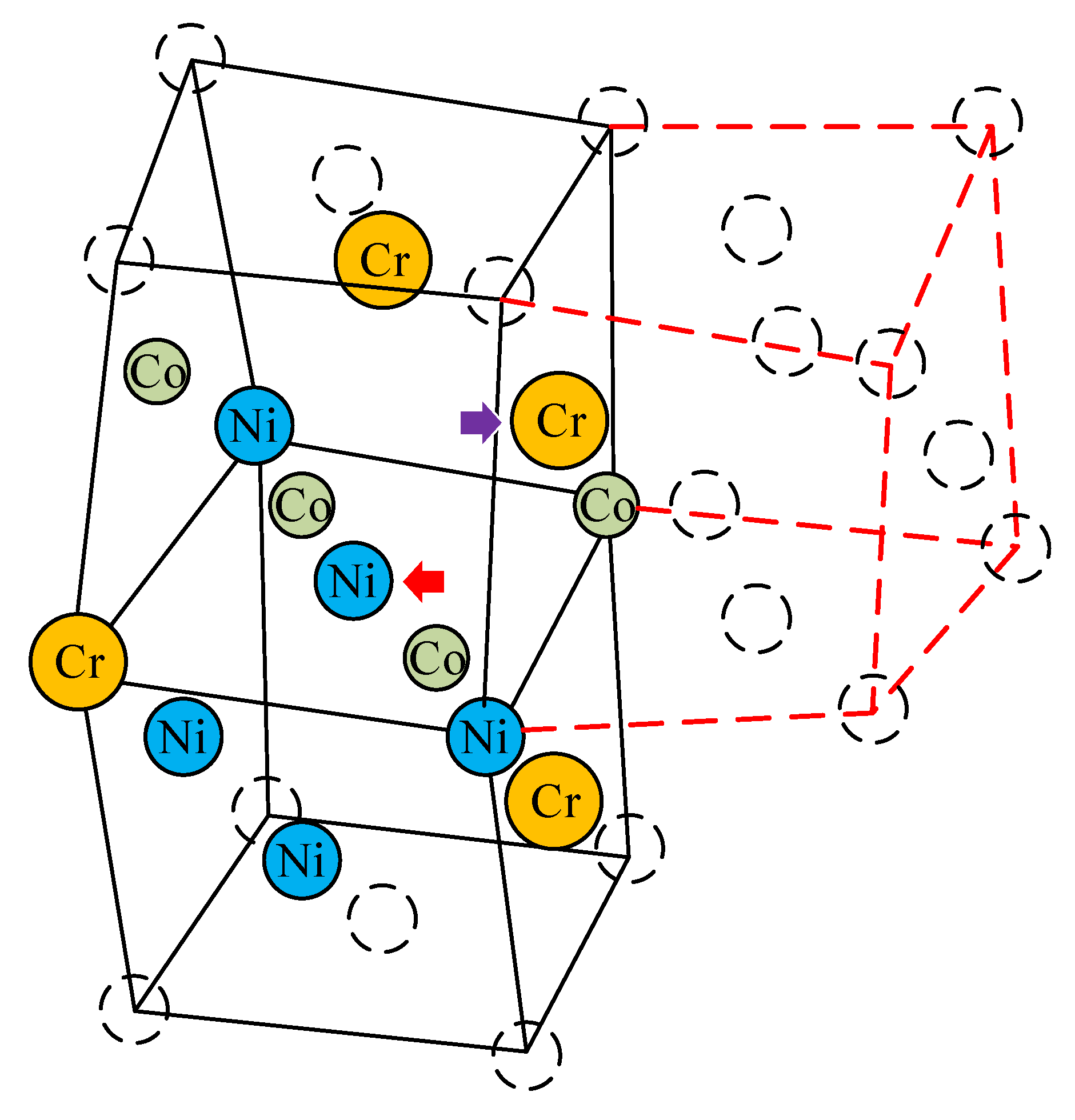

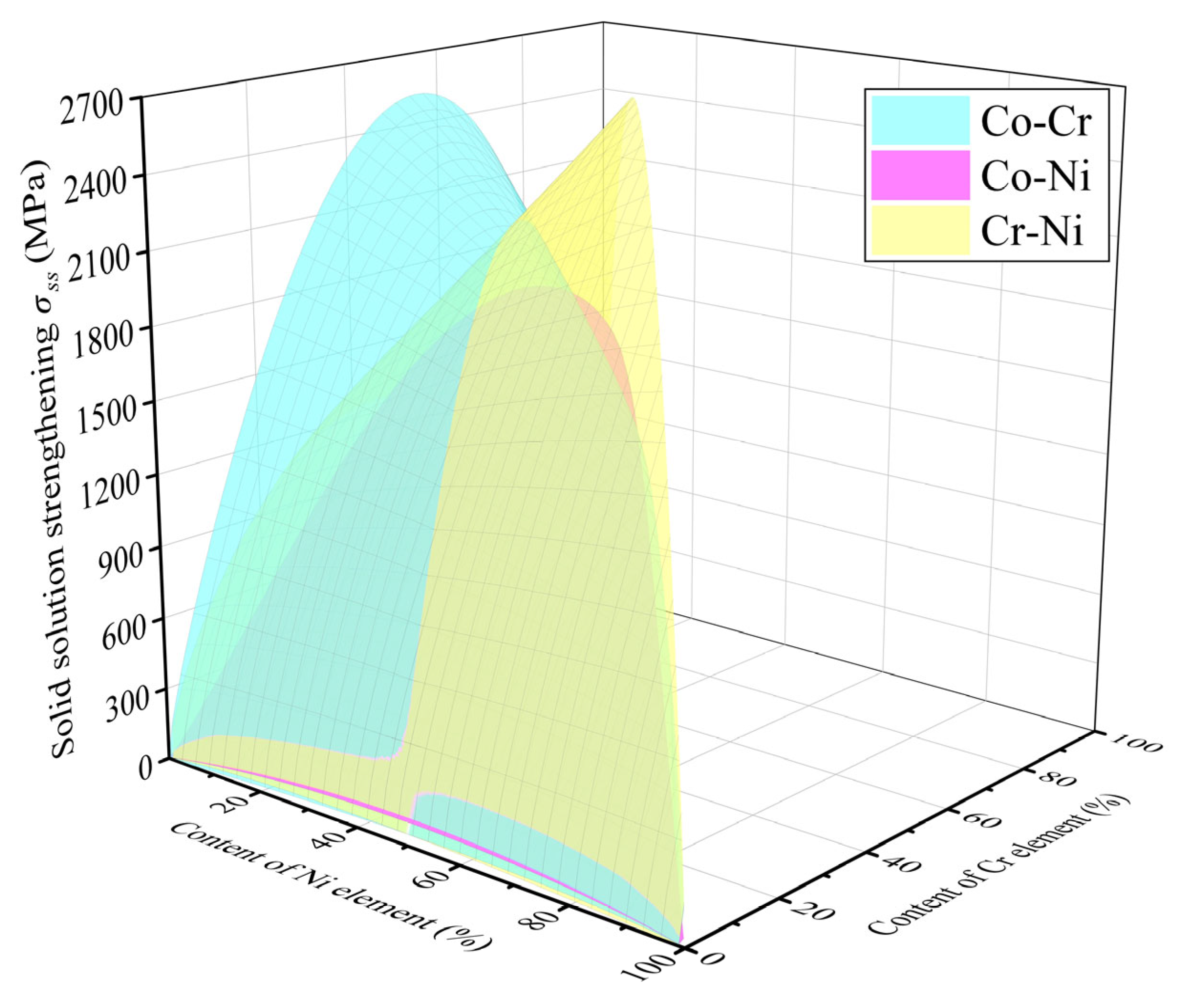

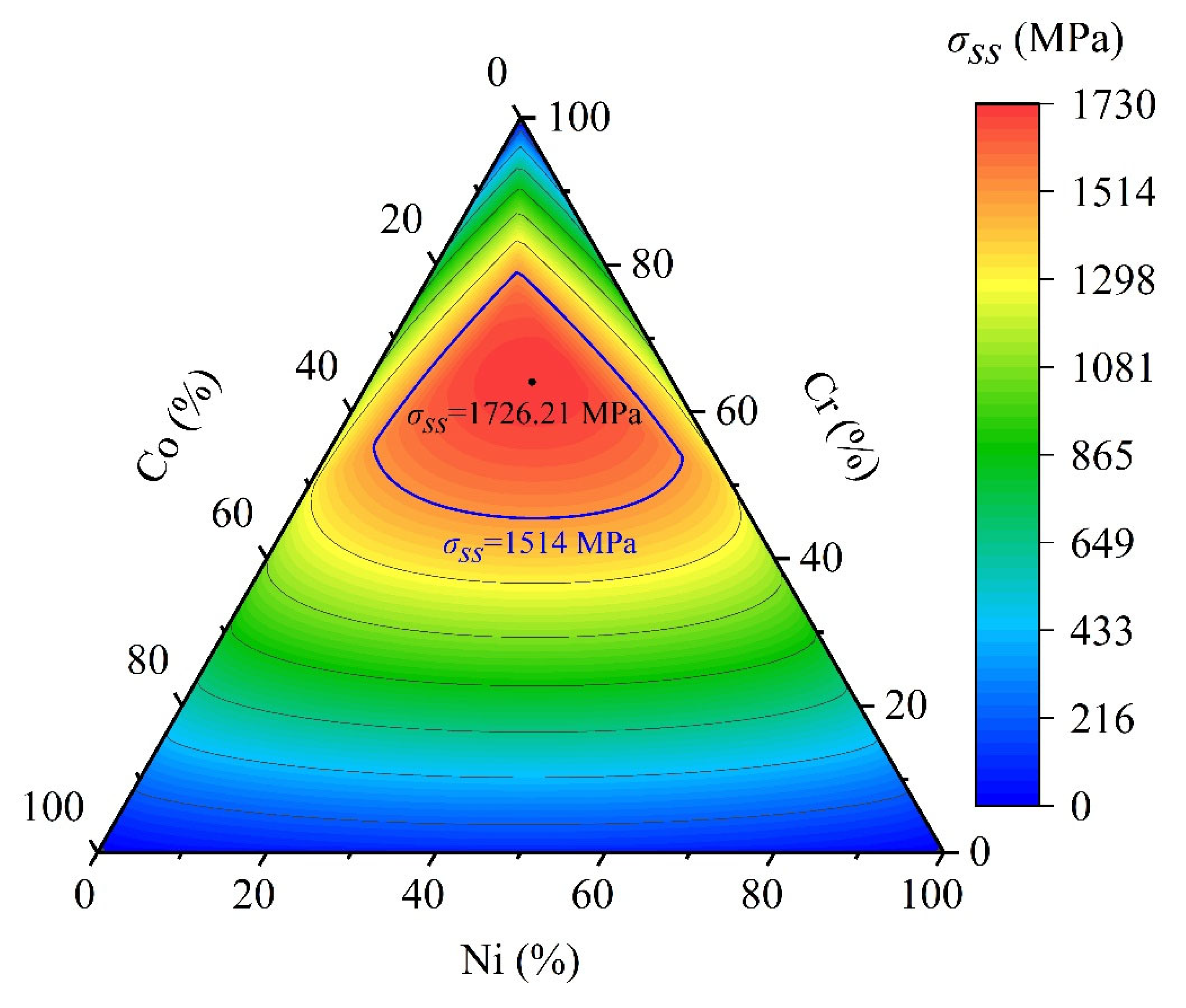

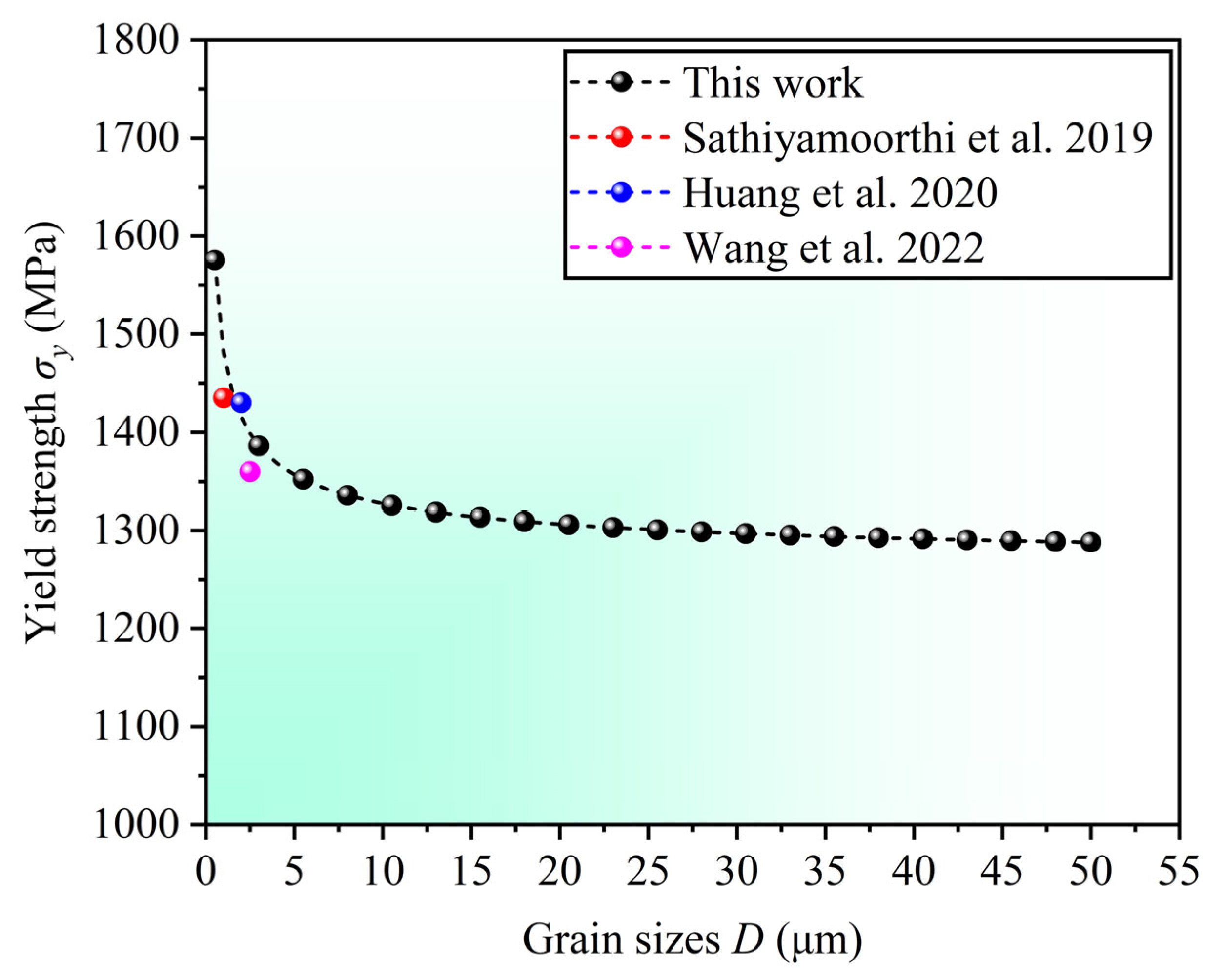

2. Theoretical Model

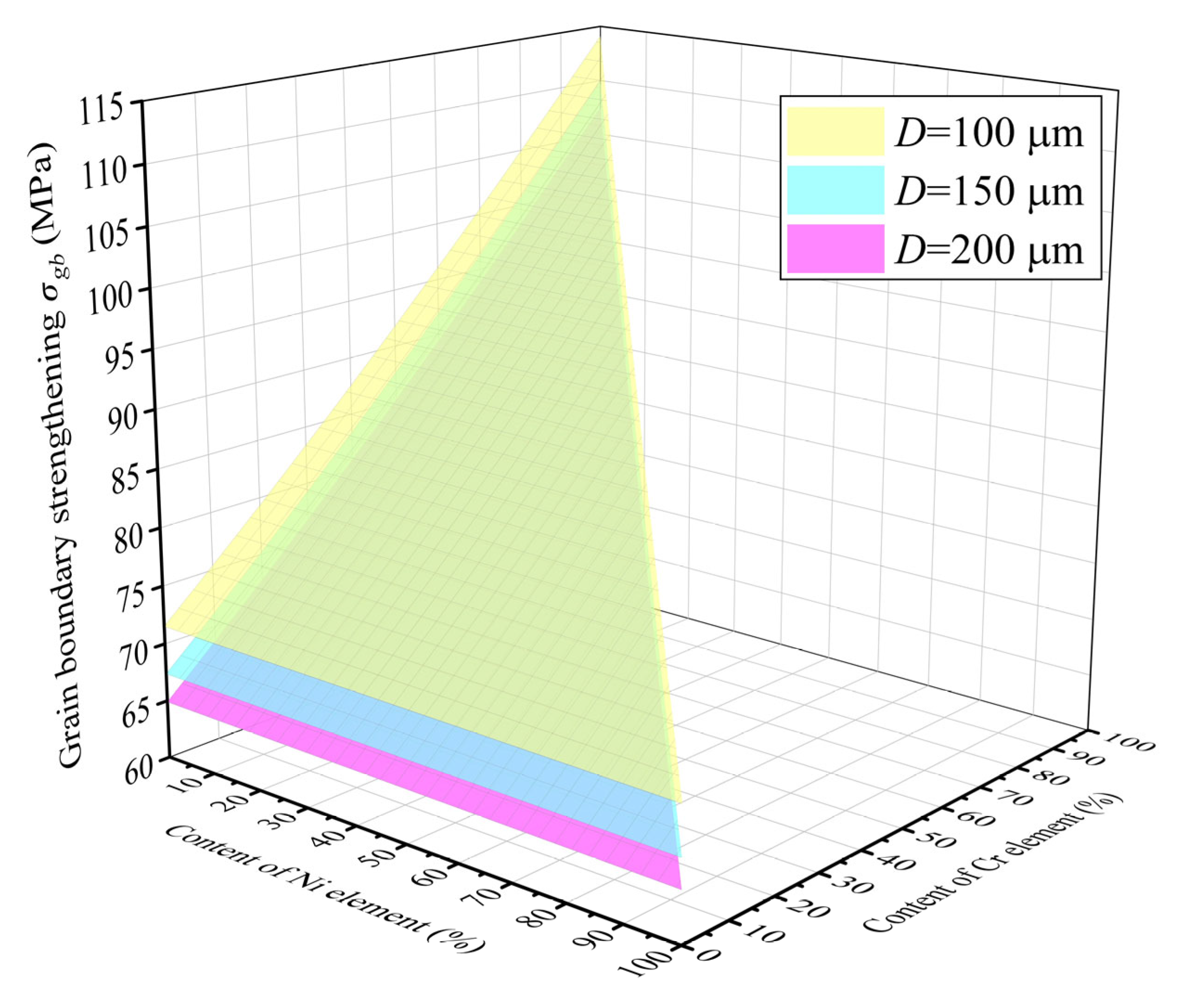

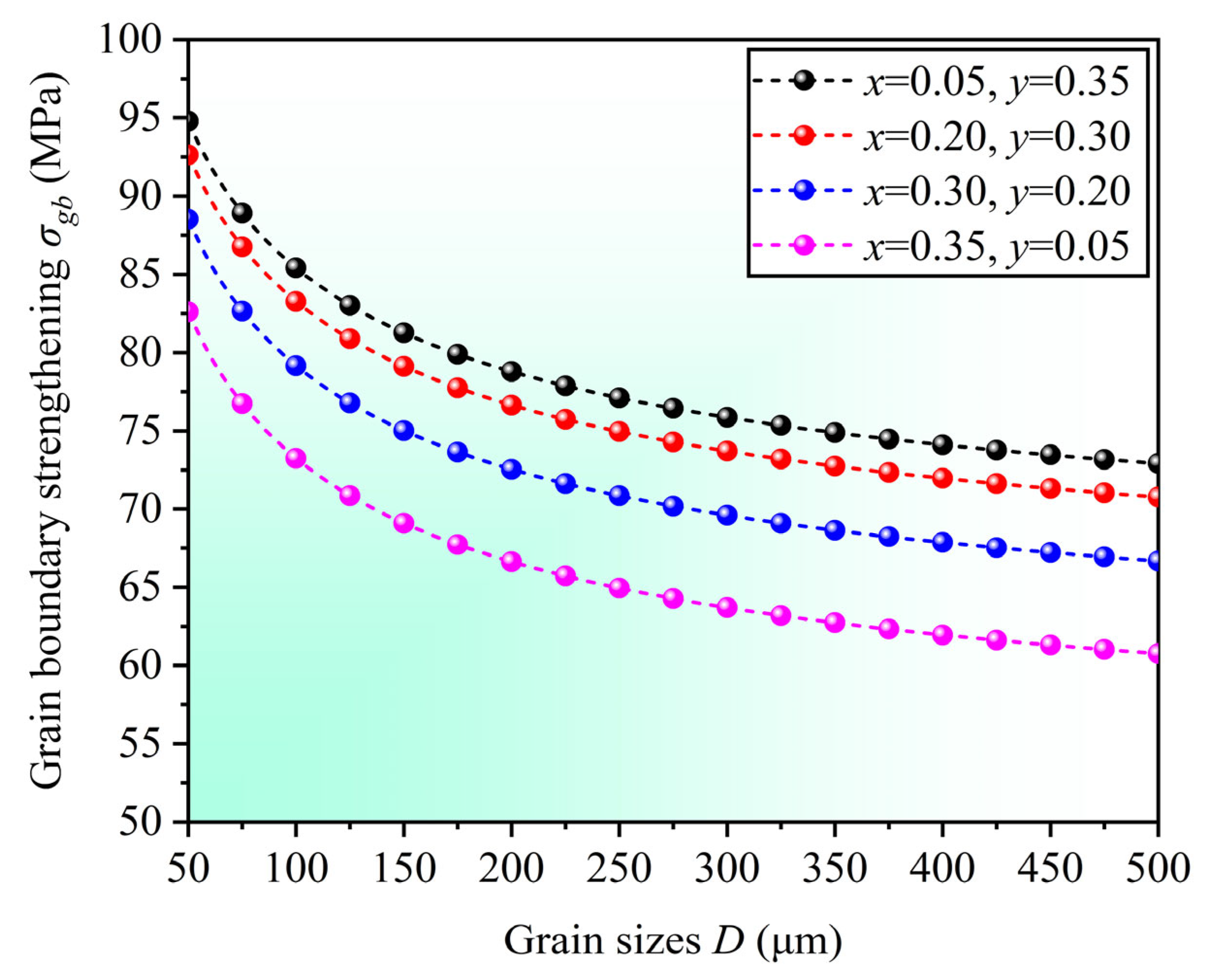

3. Results and Discussions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ye, Y.F.; Wang, Q.; Lu, J.; Liu, C.T.; Yang, Y. The generalized thermodynamic rule for phase selection in multicomponent alloys. Intermetallics 2015, 59, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zuo, T.T.; Tang, Z.; Gao, M.C.; Dahmen, K.A.; Liaw, P.K.; Lu, Z.P. Microstructures and properties of high-entropy alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2014, 61, 1–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.P.; Fang, Q.H.; Li, J.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y. Effect of lattice distortion on solid solution strengthening of BCC high-entropy alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2018, 34, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.D.; Ma, Y.M.; Dong, W.Q.; Liu, X.S.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.F.; Li, R.; Wang, Y.Y.; Yu, P.F.; Gao, Y.P.; et al. Phase evolution, microstructure, and mechanical behaviors of the CrFeNiAlxTiy medium-entropy alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 771, 138566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gludovatz, B.; Hohenwarter, A.; Thurston, K.V.S.; Bei, H.B.; Wu, Z.G.; George, E.P.; Ritchie, R.O. Exceptional damage-tolerance of a medium-entropy alloy CrCoNi at cryogenic temperatures. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.W.; Chen, S.K.; Lin, S.J.; Gan, J.Y.; Chin, T.S.; Shun, T.T.; Tsau, C.H.; Chang, S.Y. Nanostructured High-Entropy Alloys with Multiple Principal Elements: Novel Alloy Design Concepts and Outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2004, 6, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.X.; Kang, K.W.; Zhang, J.S.; Xu, M.K.; Huang, D.; Liu, S.K.; Jiang, Y.T.; Li, G. Pursuing ultrahigh strength–ductility CoCrNi-based medium-entropy alloy by low-temperature pre-aging. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 220, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.P.; Zhou, D.Z.; Jiang, D.; Song, X.J.; Zhang, G.S.; Wang, G.J.; Suo, T.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, H.Z. Wear and wear-corrosion performance of CoCrNi-based high-entropy alloys modified by Mo and C under ultrasonic-assisted laser cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 513, 132446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, H.; Park, K.; Jung, Y.J.; Lee, K.J.; Hong, S.H.; Kim, K.B.; Lee, C.; Song, G. Overcoming strength-ductility trade-off via L21 precipitate-strengthening in Al0.3CoCrNiTi0.1 high entropy alloy at room and cryogenic temperatures. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 39, 933–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Bei, H.; Pharr, G.M.; George, E.P. Temperature dependence of the mechanical properties of equiatomic solid solution alloys with face-centered cubic crystal structures. Acta Mater. 2014, 81, 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S.; Bhattacharjee, T.; Bai, Y.; Tsuji, N. Friction stress and Hall-Petch relationship in CoCrNi equi-atomic medium entropy alloy processed by severe plastic deformation and subsequent annealing. Scr. Mater. 2017, 134, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.F.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.T.; He, J.Y.; Liu, J.B.; Chen, C.X.; Liu, X.J.; Wang, H.; Lu, Z.P. Stacking fault energy of face-centered-cubic high entropy alloys. Intermetallics 2018, 93, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.B.; Yang, H.K.; Fan, R.; Zhang, W.Q.; Meng, F.L.; Gan, B.; Lu, Y. Heavily twinned CoCrNi medium-entropy alloy with superior strength and crack resistance. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 788, 139591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; He, Q.F.; Gao, X.; Shang, Y.H.; Zhu, W.Q.; Zhao, W.J.; Chen, Z.Q.; Gong, H.; Yang, Y. Multifunctional high entropy alloys enabled by severe lattice distortion. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2305453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Tucker, W.C.; Balasubramanian, G. Optimal interplay of charge localization, lattice dynamics and slip systems drives structural softening in dilute W alloys with Re additives. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2025, 128, 107086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.O. The Deformation and Ageing of Mild Steel: III Discussion of Results. Proc. Phys. Soc. B 1951, 64, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petch, N.J. The Cleavage Strength of Polycrystals. J. Iron Steel Inst. Jpn. 1953, 174, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.N. A new modification of the formulation of Peierls stress. Acta Mater. 1996, 44, 1541–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.N. Prediction of Peierls stresses for different crystals. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1996, 206, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, D.L. Transition metal alloys: Elastic properties and Peierls–Nabarro stresses. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2000, 293, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegard, L. Die konstitution der mischkristalle und die raumfüllung der atome. Z. Phys. 1921, 5, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couzinié, J.P.; Senkov, O.N.; Miracle, D.B.; Dirras, G. Comprehensive data compilation on the mechanical properties of refractory high-entropy alloys. Data Brief. 2018, 21, 1622–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsse, S.; Nguyen, M.H.; Senkov, O.N.; Miracle, D.B. Database on the mechanical properties of high entropy alloys and complex concentrated alloys. Data Brief. 2018, 21, 2664–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petch, N.J. The ductile-brittle transition in the fracture of α-iron: I. Philos. Mag. A 1958, 3, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.M.; Hariharan, V.S.; Yadav, S.K.; Murty, B.S. CALPHAD and rule-of-mixtures: A comparative study for refractory high entropy alloys. Intermetallics 2020, 127, 106926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.Y.; Chen, Z.J.; Su, M.Y.; Ding, G.; Jiang, M.Q.; Xie, Z.C.; Gong, Y.; Wu, T.; Wu, Z.H.; Wang, H.Y.; et al. Lattice distortion and magnetic property of high entropy alloys at low temperatures. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 104, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, S.; Sharma, A.; Jiang, C.; Gwalani, B.; Lin, W.C.; Lo, K.C.; Gorsse, S.; Yeh, A.C.; Srinivasan, S.G.; Banerjee, R. Exceptional enhancement of mechanical properties in high-entropy alloys via thermodynamically guided local chemical ordering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2211787120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, R.L. Substitutional solution hardening. Acta Metall. 1963, 11, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labusch, R. A statistical theory of solid solution hardening. Phys. Status Solidi B 1970, 41, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkov, O.N.; Scott, J.M.; Senkova, S.V.; Miracle, D.B.; Woodward, C.F. Microstructure and room temperature properties of a high-entropy TaNbHfZrTi alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 6043–6048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gypen, L.A.; Deruyttere, A. Multi-component solid solution hardening. J. Mater. Sci. 1977, 12, 1028–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salishchev, G.A.; Tikhonovsky, M.A.; Shaysultanov, D.G.; Stepanov, N.D.; Kuznetsov, A.V.; Kolodiy, I.V.; Tortika, A.S.; Senkov, O.N. Effect of Mn and V on structure and mechanical properties of high-entropy alloys based on CoCrFeNi system. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 591, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Z.Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, J.; Chen, X.H.; Wang, L.; Si, J.J.; Wu, Y.D.; Hui, X.D. Affordable FeCrNiMnCu high entropy alloys with excellent comprehensive tensile properties. Intermetallics 2016, 77, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, E. Unusual dislocation behavior in high-entropy alloys. Scr. Mater. 2020, 181, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Li, S.Z.; Zong, H.X.; Ding, X.D.; Sun, J.; Ma, E. Unusual activated processes controlling dislocation motion in body-centered-cubic high-entropy alloys. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 16199–16206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, J.S.; Liu, Y.; Fang, Q.H.; Wu, Y.; Chen, S.Q.; Liu, C.T. Microstructure and mechanical properties of equimolar FeCoCrNi high entropy alloy prepared via powder extrusion. Intermetallics 2016, 75, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sathiyamoorthi, P.; Moon, J.; Bae, J.W.; Asghari-Rad, P.; Kim, H.S. Superior cryogenic tensile properties of ultrafine-grained CoCrNi medium-entropy alloy produced by high-pressure torsion and annealing. Scr. Mater. 2019, 163, 152–156. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Wang, J.Y.; Yang, H.L.; Ji, S.X.; Yu, H.L.; Liu, Z.L. Strengthening CoCrNi medium-entropy alloy by tuning lattice defects. Scr. Mater. 2020, 188, 216–221. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.Y.; Zou, J.P.; Yang, H.L.; Huang, H.; Liu, Z.L.; Ji, S.X. Strength improvement of CoCrNi medium-entropy alloy through introducing lattice defects in refined grains. Mater. Charact. 2022, 193, 112254. [Google Scholar]

| Element | Co | Cr | Ni |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic radius, r (pm) | 125 | 128 | 124 |

| Shear modulus, μ (GPa) | 75 | 115 | 76 |

| Melting temperature, Tm (K) | 1768 | 2180 | 1728 |

| Atomic fraction, c | 1-x-y | y | x |

| Element i/j, δrij/δμij | Co | Cr | Ni |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co | 0 | 0.0237 | 0.0080 |

| Cr | 0.4210 | 0 | 0.0317 |

| Ni | 0.0132 | 0.4083 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Chen, S. Theoretical Prediction of Yield Strength in Co(1-x-y)CryNix Medium-Entropy Alloys: Integrated Solid Solution and Grain Boundary Strengthening. Metals 2025, 15, 1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121352

Wang Z, Yu Z, Zhang L, Chen S. Theoretical Prediction of Yield Strength in Co(1-x-y)CryNix Medium-Entropy Alloys: Integrated Solid Solution and Grain Boundary Strengthening. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121352

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhipeng, Zhaowen Yu, Linkun Zhang, and Shuying Chen. 2025. "Theoretical Prediction of Yield Strength in Co(1-x-y)CryNix Medium-Entropy Alloys: Integrated Solid Solution and Grain Boundary Strengthening" Metals 15, no. 12: 1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121352

APA StyleWang, Z., Yu, Z., Zhang, L., & Chen, S. (2025). Theoretical Prediction of Yield Strength in Co(1-x-y)CryNix Medium-Entropy Alloys: Integrated Solid Solution and Grain Boundary Strengthening. Metals, 15(12), 1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121352