Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the growth behavior of key precipitates in 9–12 wt.% Cr ferritic/martensitic heat-resistant steel as a function of tempering duration. Tempering was carried out at 670 °C for durations between 1 h and 300 h. The precipitates identified were M23C6, Laves phase, Nb-rich MX, and V-rich MX, each exhibiting distinct growth behavior with increasing tempering time. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to quantitatively analyze their growth behavior. The results revealed that M23C6, Laves phase, and V-rich MX underwent progressive coarsening with time, whereas Nb-rich MX showed negligible growth even after prolonged tempering. Based on the quantified data, a precipitate-growth model was implemented in MatCalc, and the key parameters were derived and validated against experimental data. The modeling results showed excellent agreement with experimental observations, confirming that the proposed model can reliably predict the microstructural evolution of ferritic/martensitic heat-resistant steel under long-term high-temperature exposure relevant to USC applications.

1. Introduction

Owing to their excellent thermal conductivity, oxidation resistance, high-temperature strength, and low thermal expansion, 9–12% Cr ferritic/martensitic (F/M) heat-resistant steels are widely used in steam turbines for power plants [1,2,3]. In recent years, efforts have been made to further increase the operating temperature and pressure of steam turbines to enhance the thermal efficiency of power plants and reduce greenhouse gas emissions [4]. For these steels, maintaining a stable microstructure under high-temperature service conditions is essential, as microstructural features such as grain size, precipitate distribution, and dislocation density strongly influence creep resistance at elevated temperatures [5,6].

In F/M steels, precipitates such as M23C6, laves phase, and MX carbonitrides play a critical role in determining creep strength. M23C6 (M = Fe, Cr,) carbides, typically 50–100 nm in size, are predominantly distributed along prior austenite grain boundaries (PAGBs), packet boundaries, and block boundaries, acting as effective Zener pinning obstacles and maintaining boundary stability during long-term exposure [7,8]. These MX carbonitrides (M = Nb, V; X = C, N) are generally smaller than 60 nm and are present both along lath boundaries and at dislocations within the matrix [9,10]. These fine precipitates are known to effectively restrict PAGB through Zener pinning, thereby contributing to grain refinement, as demonstrated in previous work [11]. Laves phase (Fe2(Mo, W)), ranging from several tens to hundreds of nanometers, is generally found at PAGBs and lath boundaries [12]. If the Laves phase remains fine and uniformly distributed, it can positively contribute to creep strength by hindering dislocation motion and stabilizing the microstructure [13]. These precipitates affect the microstructural factors that determine creep life. These precipitates effectively impede grain boundary migration and dislocation motion at high temperatures, thereby contributing to microstructural stabilization and improved creep resistant [14,15,16]. However, prolonged high-temperature exposure leads to the coarsening of these precipitates, which in turn degrades the creep strength. Consequently, understanding of these precipitates growth and coarsening during tempering is crucial for achieving stable microstructure and improving long-term creep properties in heat resistant steel.

In this study, the growth behavior of key precipitates including M23C6, laves phase, Nb-rich MX, and V-rich MX was investigated in 9–12 wt.% Cr ferritic/martensitic heat-resistant steel designed for ultra-supercritical (USC) power plant steam turbines. The steel was tempered at 670 °C for various durations, and the resulting microstructural evolution was analyzed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Based on the experimental data, a precipitate growth model was developed using the MatCalc software to determine the interfacial energy and other key parameters of each precipitate. The established model provides a predictive framework for understanding precipitate coarsening behavior and evaluating microstructural stability during long-term high-temperature service.

2. Materials and Experimental Procedures

To investigate the microstructural evolution during tempering at 670 °C, a ferritic/martensitic heat-resistant steel was prepared within compositional range of the MTR10A, containing 0.16 wt.% C, 10.1 wt.% Cr, 0.7 wt.% Mo, 1.9 wt.% W, 3.5 wt.% Co, 0.2 wt.% V, and 0.02 wt.% Nb was designed. Excluding the adjusted carbon content, the overall chemical composition is consistent with that of the MTR10A steel developed for USC power plants operating above 600 °C [17].

Ingots weighing 60 kg were fabricated by means of vacuum induction melting (VIM) followed by electroslag remelting (ESR). The remelted ingots were subsequently hot-forged into slabs and machined into plates with dimensions of 100 mm × 200 mm × 20 mm for heat-treatment experiments.

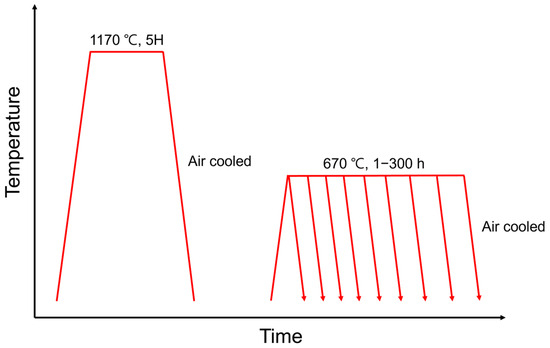

Homogenization heat treatment was conducted at 1170 °C for 5 h, followed by tempering at 670 °C for various durations of 1, 2, 5, 10, 30, 50, 100, 200, and 300 h. After each heat treatment, the specimens were air-cooled to room temperature. The overall heat treatment process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the two-step heat-treatment process: homogenization at 1170 °C for 5 h followed by tempering at 670 °C for various durations, with air cooling after each step.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEM-2100F; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) was performed to characterize the precipitates. Thin-foil specimens for TEM observation were prepared using twin-jet polishing (TenuPol-5; Struers, Ballerup, Denmark) at −25 °C under an applied voltage of 21.5 V in an electrolyte composed of methanol and perchloric acid (9:1 by volume) after mechanical thinning. Quantitative analysis of the precipitates, including the average size and volume fraction, was conducted using image analysis software (Image-Pro 11; Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA).

The Vickers hardness test was performed under a load of 1 kgf, and thirty indentations were taken for each condition. The average value of these measurements was used to represent the hardness.

Equilibrium phase fraction and precipitation growth behavior were simulated using MatCalc 6 (Version 6.03). The simulations were performed based on the Gibbs free energy database (mc_steel, version 2.06) and the mobility database (mc_steel, version 2.012) to model the nucleation, growth, and coarsening behavior of precipitates during tempering. Equilibrium phase fraction and precipitation growth behavior were simulated using MatCalc 6 (Version 6.03). The simulations were performed based on the Gibbs free energy database (mc_steel, version 2.06) and the mobility database (mc_steel, version 2.012) to model the nucleation, growth, and coarsening behavior of precipitates during tempering.

3. Results

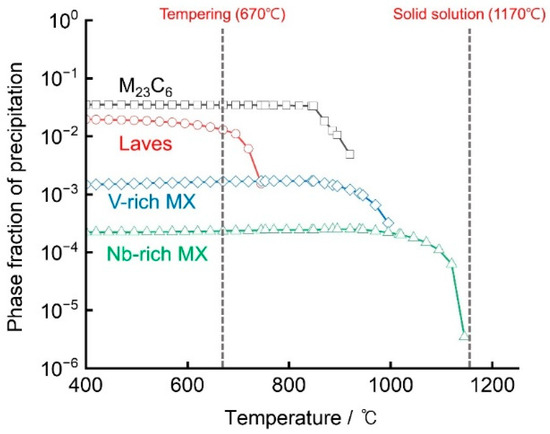

As illustrated in Figure 2, the equilibrium phase fractions of the investigated steel as a function of temperature were calculated using MatCalc 6 software [18,19]. The complete dissolution temperature of NbC was determined to be approximately 1145 °C, indicating that all precipitates were fully dissolved in the matrix at the solutionizing temperature of 1170 °C. At the tempering temperature of 670 °C, four types of precipitates M23C6, laves phase, V-rich MX and Nb-rich MX were predicted to be thermodynamically stable in the matrix. Among these, M23C6 exhibited the highest phase fraction and was the dominant precipitate, followed by the Laves phase, V-rich MX, and Nb-rich MX. As illustrated in Figure 1, the equilibrium phase fractions of the investigated steel as a function of temperature were calculated using MatCalc 6 software [13,14]. The complete dissolution temperature of NbC was determined to be approximately 1145 °C, indicating that all precipitates were fully dissolved in the matrix at the solutionizing temperature of 1170 °C. At the tempering temperature of 670 °C, four types of precipitates M23C6, Laves phase, V-rich MX and Nb-rich MX were predicted to be thermodynamically stable in the matrix. Among these, M23C6 exhibited the highest phase fraction and was the dominant precipitate, followed by the Laves phase, V-rich MX, and Nb-rich MX.

Figure 2.

Predicted phase equilibriums of major precipitates in the investigated steel as a function of temperature, calculated using MatCalc 6. Symbols represent different precipitates, black-squares: M23C6, red-circles: Laves, blue-diamonds: V-rich MX, green-triangles: Nb-rich MX.

As shown in Figure 3a, the microstructure following solid-solution treatment consisted of martensite. As observed in Figure 3b, needle-like precipitates were present within some martensite laths, whereas no other secondary phases were detected at this stage. These precipitates were further characterized by means of high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) and fast Fourier transformation (FFT) analysis, as shown in Figure 3c. The HR-TEM micrographs and corresponding FFT patterns confirmed that the needle-like precipitates correspond to M3C carbides with an orthorhombic crystal structure. These carbides are considered to have formed through auto-tempering during air cooling after the homogenization heat treatment. During rapid air cooling, non-equilibrium precipitation can occur, allowing Fe3C to nucleate within the martensitic laths. Similar auto-tempering induced M3C formation during cooling has been reported in previous studies [20,21].

Figure 3.

SEM and TEM micrographs of microstructure after heat-treatment at 1170 °C followed by air cooling: (a) SEM image, (b) the bright-field image show M3C (indicated by yellow marked region) distributed within martensitic laths in white marked region of (a), and (c) the HR-TEM images and FFT patterns of M3C extracted from the yellow marked region in (b).

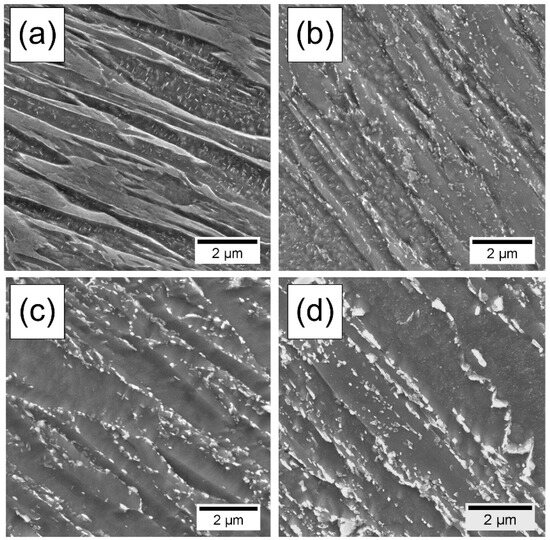

Figure 4 illustrates the microstructural evolution during tempering at 670 °C. Before tempering (Figure 4a), The microstructure consists of fine lath martensite. As the tempering time increases, precipitates begin to form along the grain and lath boundaries (Figure 4b). After 100 h of tempering, the microstructural features within the martensite laths become coarser, accompanied by further growth and coarsening of the precipitates (Figure 4c). When the tempering time is extended to 300 h, significant coarsening of the precipitates occur and some lath boundaries begin to disappear, indicating a gradual recovery of the matrix (Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

SEM micrographs of microstructural evolution as function of tempering time: (a) before tempering, (b) 1 h of tempering, (c) 100 h of tempering and (d) 300 h of tempering.

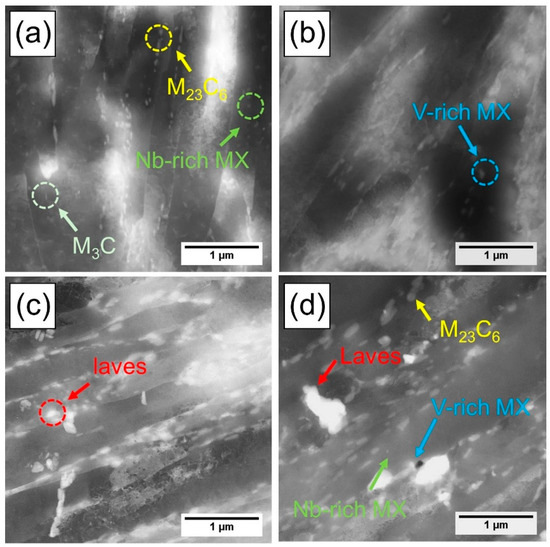

Figure 5 shows the evolution of precipitates as a function of tempering time, observed using high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM, JEM-2100F; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). After 1 h of tempering, M3C, M23C6, and Nb-rich MX were identified, among which M23C6 exhibited the highest number density. As tempering proceeded, the amount of M3C remaining within the martensite laths gradually decreased. This reduction is attributed to the diffusion of alloying elements such as Cr and W into M3C, which promotes its transformation into the more stable M23C6 phase during tempering [22,23,24]. After 2 h of tempering, M3C precipitates were no longer observed, while V-rich MX began to observed. After 10 h of tempering, the laves phase was additionally observed, and no other new precipitate types were formed up to 300 h. The existing precipitates exhibited progressive coarsening with increasing tempering time. Figure 5 shows the evolution of precipitates as a function of tempering time, observed using high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM). After 1 h of tempering, M3C, M23C6, and Nb-rich MX were identified, among which M23C6 exhibited the highest number density. As tempering proceeded, the amount of M3C remaining within the martensite laths gradually decreased. This reduction is attributed to the diffusion of alloying elements such as Cr and W into M3C, which promotes its transformation into the more stable M23C6 phase during tempering [22,23,24]. After 2 h of tempering, M3C precipitates were no longer observed, while V-rich MX began to observed. After 10 h of tempering, the laves phase was additionally observed, and no other new precipitate types were formed up to 300 h. The existing precipitates exhibited progressive coarsening with increasing tempering time.

Figure 5.

HAADF-STEM micrographs of precipitate evolution as a function of tempering time: (a) after 1 h of tempering, (b) after 2 h of tempering, (c) after 10 h of tempering, and (d) after 300 h of tempering.

The crystal structures of the four precipitates in the specimen tempered for 300 h were analyzed, and the corresponding results are presented in Figure 6. The M23C6 and Laves phase were identified as face-centered cubic (FCC) and hexagonal structures, respectively, as shown in Figure 6a,b. The V and Nb-rich MX precipitates were characterized using HR-TEM and FFT pattern analysis, as shown in Figure 6c,d. Both MX-type precipitates exhibited an FCC structure, consistent with previously reported observations in ferritic/martensitic steels. These results confirm the crystallographic stability of the four major precipitates after long-term tempering.

Figure 6.

TEM micrographs of the specimen tempered at 670 °C for 300 h, showing the four major precipitate types: (a) M23C6, (b) Laves phase, (c) V-rich MX, and (d) Nb-rich MX.

Figure 7 presents the variation in Vickers hardness as a function of tempering time. The hardness exhibits a gradual decreasing trend with increasing tempering duration. This softening behavior corresponds well with the microstructural evolution described earlier.

Figure 7.

Vickers hardness test result as function of tempering times.

The quantitative evolution of precipitate size as a function of tempering time at 670 °C is presented in Figure 8a. The M23C6 precipitates exhibited a gradual increase in size, with more pronounced growth observed after 5 h, 50 h, and 300 h. However, the growth rate of M23C6 appears to be considerably suppressed in this alloy due to its higher Co content compared with conventional alloys. Similarly, the Laves phase showed a steady coarsening trend, with significant growth occurring after 100 h. The V-rich MX precipitates displayed a relatively slow growth rate in the early stages but exhibited an accelerated coarsening behavior after 200 h. In contrast, the Nb-rich MX precipitates showed negligible size variation, indicating that they remained thermally stable even after long-term tempering. The experimentally measured phase fractions of the precipitates were compared with the equilibrium phase fractions calculated at 670 °C, as shown in Figure 8b. The M23C6 phase maintained a fraction close to its equilibrium value from the early stages of tempering. In contrast, the laves phase, V-rich MX, and Nb-rich MX exhibited slight deviations from equilibrium in the early stage but gradually approached the equilibrium fractions after 300 h of tempering.

Figure 8.

Experimentally obtained precipitate characteristics as a function of tempering time: (a) evolution of precipitate size during tempering and (b) comparison between the experimentally measured phase fractions (symbols) and the equilibrium phase fractions calculated at 670 °C (lines).

4. Discussion

To further clarify the experimental observations, a computational model was developed using MatCalc 6 to predict the evolution of precipitates during tempering at 670 °C in 9–12 wt.% Cr ferritic/martensitic heat-resistant steel. MatCalc 6 simulates the precipitation behavior based on Onsager’s classical nucleation theory and incorporates the kinetics of precipitate growth and coarsening within the framework of the Kampmann–Wagner Numerical (KWN) model, which quantitatively describes microstructural evolution during heat treatment [25,26]. The nucleation of new precipitates is analyzed using an extended form of classical nucleation theory, in which the nucleation rate (J) is expressed as follows:

where represents the Zeldovich factor, is the number of potential nucleation sites, denotes the atomic attachment rate, and is the critical energy barrier for nucleation. is the Boltzmann constant, is the absolute temperature, represents time, and is the incubation time. The critical energy barrier for nucleation () can be expressed as follows:

where represents the interfacial energy, and is Gibbs free energy change per unit volume associated with nucleation, which varies with temperature and chemical composition. The interfacial energy is a critical parameter that strongly influences the nucleation, growth, and coarsening of precipitates.

To simulate the growth behavior of the major complex precipitates, key thermodynamic and kinetic parameters of the matrix and precipitates were considered, as summarized in Table 1. The four primary precipitates observed at 670 °C, were selected for simulation with a focus on their individual growth kinetics. To accurately describe the time-dependent evolution of these precipitates, their potential nucleation sites at this temperature were carefully evaluated. Nucleation may occur at multiple locations, including the bulk matrix, dislocations, grain boundaries, and subgrain boundaries, all of which significantly affect precipitate kinetics. Moreover, precise modeling of complex precipitate growth requires consideration of the interfacial energy of each phase, which governs the driving force for nucleation and coarsening.

Table 1.

Key parameters used to define the matrix domain for the precipitation modeling.

Table 1 lists the key matrix parameters used in the simulations. Since the matrix phase was martensitic, the dislocation density was set to 1015 m−2 [27]. The parameters listed in Table 1 and Table 2 are approximate suggestions intended to simulate the present system, and they do not represent optimized values for reproducing the experimentally measured phase fractions and precipitate sizes. Table 2 summarizes the parameters related to nucleation sites and interfacial energy for the four precipitate phases. The simulations of complex precipitate behavior were performed using the parameters presented in Table 1 and Table 2, and the modeling results are presented in Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Table 2.

Principal parameters governing the precipitation kinetics used in the simulation.

Figure 9.

Comparison between the experimentally measured and simulated phase-fraction evolution of the precipitates during tempering at 670 °C for up to 1000 h, calculated using MatCalc 6. Symbols represent experimental data and lines represent simulation results: (a) M23C6, (b) Laves phase, (c) Nb-rich MX, and (d) V-rich MX.

Figure 10.

Comparison between the experimentally measured and simulated growth behavior of the precipitates during tempering at 670 °C for up to 1000 h, calculated using MatCalc 6. symbols represent experimental data, lines represent simulation results: (a) M23C6, (b) Laves phase, (c) Nb-rich MX, and (d) V-rich MX.

Figure 9 presents a comparison between the phase fractions of the four precipitates calculated using MatCalc, based on the parameters listed in Table 1 and Table 2, and the experimentally obtained data. The simulated and experimental results show good overall agreement, demonstrating that the model can effectively predict the phase fraction evolution of the four precipitates during tempering.

Figure 10 compares the calculated growth behavior of the precipitates over 1000 h at 670 °C, based on the interfacial energy values listed in Table 2, with the experimentally measured data. The comparison demonstrates good agreement between the calculated and experimental values, confirming that the interfacial energy parameters used in the model can reliably predict precipitate growth behavior. The predicted growth behavior of the four precipitates during long-term tempering is summarized as follows. As shown in Figure 10a, the M23C6 precipitates are expected to continue coarsening beyond 300 h. Figure 10b indicates that the Laves phase shows limited coarsening up to 1000 h. Figure 10c suggests that the Nb-rich MX precipitates exhibit negligible size change, consistent with the experimental observations. Finally, Figure 10d shows that the V-rich MX precipitates have the potential to grow further during prolonged heat exposure.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the precipitation growth behavior of 9–12 wt.% Cr ferritic/martensitic heat-resistant steel was systematically analyzed as a function of tempering time at 670 °C. Based on the experimental observations, a precipitation growth model was developed using MatCalc, and its reliability was evaluated by comparing the simulation results with the experimental data.

Before tempering, only M3C carbides were identified within the martensite laths. After 1 h of tempering, M23C6, Nb-rich MX, and M3C precipitates were observed, with M3C gradually dissolving as tempering progressed. By 10 h, the Laves phase had formed, and after 300 h, no additional precipitates appeared, although the existing ones exhibited continuous coarsening. Among the four primary precipitates, M23C6 and Laves phase showed relatively high growth rates, V-rich MX exhibited moderate coarsening, whereas Nb-rich MX displayed negligible growth even after long-term tempering.

Using the experimental data, the interfacial energies for each precipitate were determined to be for M23C6, for Laves phase, for Nb-rich MX, and for V-rich MX, which were applied in the MatCalc simulations. The comparison between simulated and experimental results confirmed that the model accurately reproduced the observed precipitate growth and phase-fraction evolution. In particular, the predicted coarsening behavior of M23C6 and Laves phase showed a strong correlation with experimental trends, while the limited growth of Nb-rich MX was also successfully captured.

These findings demonstrate that the precipitation growth model developed in this study can reliably predict the microstructural evolution of ferritic/martensitic heat-resistant steel during long-term tempering and can serve as a useful tool for optimizing alloy design and heat-treatment conditions.

Author Contributions

Validation, I.P. and J.H.J.; formal analysis, S.-D.K. and I.P.; data curation, B.C.P. and S.-D.K.; writing—original draft, B.C.P.; writing—review & editing, J.H.J. and N.K.; visualization, S.-D.K.; supervision, J.H.J. and N.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Fundamental R&D Program of the Korea Institute of Materials Science (KIMS). Grant No. PNKA600. This work was also supported by the Nuclear Power Plant Decommissioning Competitiveness Enhancement Technology Development Project (RS-2023-00234190) funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea). This work was supported by the Dong-A University research fund.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rojas, D.; Garcia, J.; Prat, O.; Sauthoff, G.; Kaysser-Pyzalla, A.R. 9% Cr heat resistant steels: Alloy design, microstructure evolution and creep response at 650 °C. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 528, 5164–5176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudova, N. 9–12% Cr heat-resistant martensitic steels with increased boron and decreased nitrogen contents. Metals 2022, 12, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Yan, W.; Sha, W.; Wang, W.; Shan, Y.; Yang, K. Microstructure evolution of a 10Cr heat-resistant steel during high temperature creep. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2011, 27, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuyama, F. History of power plants and progress in heat resistant steels. ISIJ Int. 2001, 41, 612–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachadel, U.A.; Morris, P.F.; Clarke, P.D. Design of 10 Cr martensitic steels for improved creep resistance in power plant applications. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2013, 29, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.K.; Behera, S.; Pandey, C.; Guguloth, K. Creep deformation behaviour of Grade 91 steel and its weld joints: A comparative study. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2025, 219, 105678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Qu, F.; Han, J.; Ma, Y. Precipitates and particles coarsening of 9Cr–1.7W–0.4Mo–Co ferritic heat-resistant steel after isothermal aging. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, F. Analysis of creep rates of tempered martensitic 9% Cr steel based on microstructure evolution. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2009, 510, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipelova, A.; Kaibyshev, R.; Belyakov, A.; Molodov, D. Microstructure evolution in a 3% Co modified P911 heat resistant steel under tempering and creep conditions. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 528, 1280–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yan, W.; van Zwaag, S.; Shi, Q.; Wang, W.; Yang, K.; Shan, Y. On the 650 °C thermostability of 9–12Cr heat resistant steels containing different precipitates. Acta Mater. 2017, 134, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.C.; Kim, S.D.; Park, I.; Shin, J.H.; Jang, J.H.; Kang, N. Effect of Nb on austenite grain growth in 10Cr–3Co–2W martensitic heat-resistant steel. Metall. Mater. Int. 2024, 30, 3311–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat, O.; Garcia, J.; Rojas, D.; Sauthoff, G.; Inden, G. The role of Laves phase on microstructure evolution and creep strength of novel 9% Cr heat resistant steels. Intermetallics 2013, 32, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knezevic, V.; Sauthoff, G.; Vilk, J.; Inden, G.; Schneider, A.; Agamennone, R.; Singheiser, L. Martensitic/ferritic super heat-resistant 650 °C steels—Design and testing of model alloys. ISIJ Int. 2002, 42, 1505–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, F. Effect of boron on microstructure and creep strength of advanced ferritic power plant steels. Procedia Eng. 2011, 10, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.D.; Wang, L.; Zhu, B.Y.; Jin, X.; Li, C.F.; Busso, E.P.; Li, D.F. Experimental and micromechanical investigation of precipitate size effects on the creep behaviour of a high chromium martensitic steel. Eur. J. Mech. A Solids 2025, 111, 105591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Tang, L. Microstructural evolution of P92 steel with different creep life consumptions after long-term service. Metals 2024, 14, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, F. Development of creep-resistant steels and alloys for use in power plants. In Structural Alloys for Power Plants; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 250–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoboda, J.; Fischer, F.D.; Fratzl, P.; Kozeschnik, E. Modelling of kinetics in multi-component multi-phase systems with spherical precipitates: I: Theory. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 385, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozeschnik, E.; Svoboda, J.; Fischer, F.D. Modified evolution equations for the precipitation kinetics of complex phases in multi-component systems. Calphad 2004, 28, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.Q.; Zhang, D.T.; Liu, Y.C.; Ning, B.Q.; Qiao, Z.X.; Yan, Z.S.; Li, H.J. Precipitation behavior and martensite lath coarsening during tempering of T/P92 ferritic heat-resistant steel. Int. J. Min. Metall. Mater. 2014, 21, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yan, Z. Investigation on the precipitation behavior of M3C phase in T91 ferritic steels. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2011, 241, 2411–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudova, N.; Kaibyshev, R. On the precipitation sequence in a 10% Cr steel under tempering. ISIJ Int. 2011, 51, 826–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Ex situ and in situ TEM investigations of carbide precipitation in a 10Cr martensitic steel. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 7845–7856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Igarashi, M.; Muneki, S.; Abe, F. Effect of heat treatment on precipitation kinetics in high-Cr ferritic steels. ISIJ Int. 2002, 42, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajek, H. Computer Simulation of Precipitation Kinetics in Solid Metals and Application to the Complex Power Plant Steel CB8. 2005. Available online: https://graz.pure.elsevier.com/en/projects/computer-simulation-of-precipitation-kinetics-in-solid-metals-and (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Holzer, I.; Sommitsch, C.; Reichmann, K.; Hofer, F. Modelling and Simulation of Strengthening in Complex Martensitic 9–12% Cr Steel and a Binary Fe–Cu Alloy; Verlag der Technischen Universität Graz: Graz, Austria, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gururaj, K.; Pal, S. Influence of dislocation density and grain size on precipitation kinetics on P92 grade steel. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 18, 1364–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).