Abstract

We review bulk transition-metal nitrides synthesized at high pressure–high temperature and recoverable at ambient conditions. We establish an elasticity-anchored framework that links crystal structure and bonding to elastic descriptors and hardness at the phase-resolved level, enabling fair cross-study comparison. Overall, hardness shows a robust association with the shear modulus G, while the Pugh ratio k = G/B modulates relative rankings across phases. When metallic bonding or non-stoichiometry/defects are pronounced, systematic deviations arise; accordingly, elasticity-based models are best used for cross-phase trends and qualitative guidance rather than absolute predictions, especially for metallic or defect-rich phases. Building on this baseline, we outline application pathways and future research directions, and we propose a minimal reporting checklist to improve reproducibility and cross-study comparability.

1. Introduction

Transition-metal nitrides (TMNs) are compelling candidates for high-hardness materials because they couple high valence-electron density with directional metal–N bonding [1,2,3,4,5]. Superhard and hard TMNs are used in cutting and wear-resistant tools, forming dies, tribological/protective coatings, and load-bearing components for high-pressure instrumentation [6,7,8,9,10]. Under high pressure, they adopt polymorphs and N-rich motifs that are difficult to stabilize at ambient conditions with N-N units [11,12,13]. High-pressure synthesis and transformation methods, such as diamond anvil cells (DACs), large-volume apparatus (LVP), and high-pressure and high-temperature (HPHT) apparatus, produce phases with high bulk modulus and high shear modulus [14,15,16]. When such phases can be quenched and retained at ambient pressure, they offer practical pathways to bulk superhard materials [17,18,19]. In this review we take a comparative, phase-resolved perspective across representative families, including Th3P4-type c-Zr3N4/c-Hf3N4, pernitrides in Re/Ir/Os systems, noble-metal nitrides, ε-NbN, δ-WN, γ/δ-MoN, and bulk Mn-N phases [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

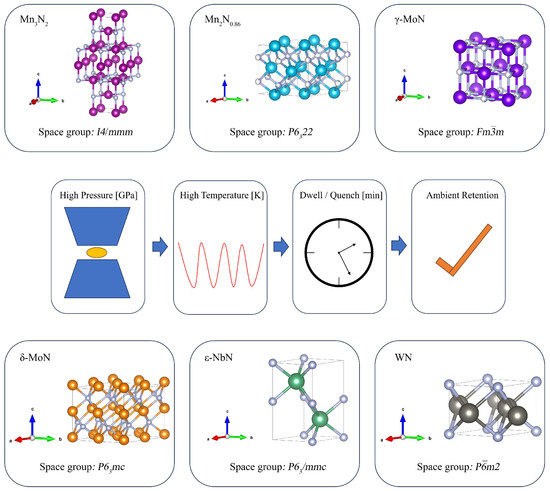

We focus on this direction for three reasons. First, many of the existing studies center on thin films [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51], where substrate constraints and residual stresses make hardness values unreliable as absolute benchmarks. Bulk behavior therefore requires a distinct, high-pressure-centric synthesis and characterization framework. Representative bulk TMN structures and a typical HPHT synthesis pathway are shown in Figure 1. Second, measurement and computational protocols differ across studies, impeding direct cross-paper comparisons. Third, discussions of theory–experiment agreement are often qualitative; a structured, phase-resolved view is needed to delineate where hardness models do and do not apply in bulk nitrides [52,53,54,55,56].

Figure 1.

Representative bulk TMN structures and an HPHT pressure–temperature–time (P-T-t) pathway. In all TMN structures shown (e.g., Mn3N2, Mn2N0.86, γ/δ-MoN, ε-NbN, WN), the colored spheres represent transition-metal atoms, whereas the white spheres represent N atoms.

Accordingly, we examine structure, elasticity, and hardness within a single framework for bulk high-pressure nitrides. Thin-film results are used only as mechanistic evidence (e.g., coherency strain, vacancies, short-range order) and are not included in hardness benchmarks. Our aims are twofold: (i) to identify the pressure and temperature routes under which each phase can be quenched and retained at ambient conditions; and (ii) to benchmark theoretical predictions against experimental hardness across representative phases, placing both on a common footing.

2. High-Pressure Phase Formation and Ambient Retention

High pressure enables access to nitride structures that are difficult to obtain or only marginally stable at ambient conditions. To render these materials practically usable, three points must be clarified: (i) which phases form under pressure; (ii) whether these phases can be quenched and retained at ambient pressure; and (iii) within what annealing windows they remain stable. Accordingly, we first survey the reported structural families, and then select representative systems to provide phase-resolved P-T-t formation windows together with the key elements of structural confirmation.

2.1. Structural Families Accessed Under Pressure

First is the competition between the rock-salt/zinc-blende and hexagonal families. A typical manifestation is a pressure-driven transformation from tetrahedrally coordinated zinc-blende or wurtzite at ambient conditions to octahedrally coordinated rock-salt or NiAs-derived lattices, reflecting the general increase in coordination number and packing density under compression. Specifically, ε-NbN and δ-WN exemplify hexagonal/NiAs-type phases that are stabilized at high pressure and can be quenched and retained at ambient pressure; by contrast, the γ/δ-MoN system demonstrates the coexistence of cubic and hexagonal polymorphs at the same nominal stoichiometry, whose relative stability and degree of ordering can be finely tuned by introducing point defects or brief anneals without triggering a phase reversion [28,29,30,57,58,59,60]. The second thread comprises the cubic Th3P4-type framework, exemplified by c-Zr3N4 and c-Hf3N4. Its salient feature is eightfold coordination of nitrogen within a highly interlocked, corner-sharing three-dimensional network. These nitrides typically require multi-GPa pressures combined with laser heating; the products are often micro- or nanocrystalline aggregates that can nevertheless be quenched and retained at ambient conditions. Rigorous control of the synthesis and post-processing environment, especially avoiding oxidative pickup from air during mechanical grinding, is crucial for long-term ambient stability [61,62,63,64]. The third thread features N-rich architectures with N-N dimers, such as Re2(N2)(N)2 and polymorphic ReN2. In these compounds, dinitrogen units (e.g., N24−) are embedded within a metal framework, imparting ultralow compressibility. Although some N-rich phases can be recovered after controlled quenching or short anneals, their complex bonding and potential polymorphism demand stringent criteria for structural assignment and cross-validation by multiple techniques [22,23].

Beyond the three principal structural threads, several high-density derivative branches also merit attention. For example, marcasite-type (Pnnm) FeN2 forms under high pressure and builds a rigid three-dimensional network of [FeN6] octahedra through edge and corner sharing. In Ta3N5, laser-heated DAC conditions have enabled the synthesis of previously predicted U3Se5/U3Te5-type dense polymorphs, markedly extending the compositional and structural landscape beyond the ambient-pressure phase diagram [34,65,66,67]. In noble-metal nitrides (Pt, Ir, Os), early studies established that the combination of high nitrogen chemical potential with high P-T conditions is the key driving force for forming dense binaries. At the same time, they repeatedly underscore that rigorous structural assignment (e.g., discriminating B1, B3, and lower-symmetry variants) is essential. Importantly, densification does not automatically translate into high hardness [26,27]. In OsN2, an increased metallic bond fraction markedly reduces the shear modulus, thereby diminishing macroscopic hardness. This clearly shows that the bulk modulus alone is insufficient to predict indentation hardness responses [35].

Ambient retention is the critical factor determining whether high-pressure nitrides can be adopted in applications. It is governed by both thermodynamic equilibrium and kinetic pathways. In practice, successful retention depends on several key factors: (i) the P-T-t path and the decompression/cooling rates, which determine whether the material avoids back-transformation or decomposition; (ii) stoichiometry and defect concentration (excess vacancies or off-stoichiometry can reduce G and phase stability while promoting oxygen uptake); (iii) microstructural characteristics such as grain size, texture, density, and any residual epitaxial stress; and (iv) stringent control of impurities, particularly oxygen and carbon, during steps like powder grinding and specimen transfer. Therefore, the practically accessible phase space of high-pressure nitrides is not determined by pressure alone, but emerges from the interplay of structural type, bonding character, kinetic trajectory, and chemical or microstructural control.

2.2. Experimentally Recovered Bulk Phases

2.2.1. Th3P4-Type: c-Zr3N4/c-Hf3N4

The defining structural feature of these phases is that the metal cations (Zr/Hf) are eightfold-coordinated by nitrogen, forming a highly interlocked three-dimensional network (Th3P4 topology). They are typically synthesized under multi-tens of GPa with laser heating, and the products can be quenched and retained at ambient conditions as micro-/nanocrystalline aggregates. A representative route employs 16–18 GPa and 2500–3000 K in laser-heated DAC or large-volume multianvil apparatus. Recovered specimens support phase identification by X-ray diffraction with Rietveld refinement and Raman spectroscopy, as well as room-temperature equation-of-state (EOS) fitting and, in some studies, nano-indentation, collectively indicating good ambient stability. It is crucial to minimize oxygen uptake during post-processing (grinding/polishing/specimen handling) to avoid surface transformation and hardness drift. The high coordination/connectivity of the framework, together with its large bulk modulus (200–250 GPa), endows the phases with strong shear rigidity and resistance to collapse, which rationalizes their comparative ease of quench–retention at ambient conditions [20,21].

2.2.2. Rhenium Pernitrides and Noble Metal (Pt/Ir/Os) Nitrides

Re-based pernitrides (e.g., Re2(N2)(N)2 containing [N2]4− units) and the polymorphs of ReN2 are prototypical outcomes of the N-rich motif combined with high-pressure activation. Owing to the presence of strong N-N covalent dimers tightly integrated into the metal framework, these compounds typically exhibit ultraincompressibility (high bulk modulus, B) and can be recovered after controlled quenching, and in some cases, brief annealing, which underscores their potential applicability [22,23]. In the noble-metal nitride systems (binary nitrides of Pt, Ir, Os), early pioneering studies established that the combination of high nitrogen chemical potential and extreme HPHT conditions is the key driving force for forming dense binaries. These studies also emphasized that rigorous phase assignment such as discriminating rock-salt (B1), zinc-blende (B3), or lower-symmetry variants must rely on cross-validation by X-ray diffraction and spectroscopic probes to avoid misidentification [24,25,26,27]. Regarding synthesis and recoverability, experimental routes primarily employ laser-heated DAC or multianvil HPHT apparatus, where metallic rhenium is reacted with nitrogen-containing media/precursors to produce nitrogen-rich phases. Recovered specimens are identified by powder XRD (with Rietveld refinement) and assigned to crystal structures that include N-N units. Complementary Raman/IR spectroscopy can verify N-N vibrational modes, and valence-state analysis further strengthens the phase assignment, together forming a robust cross-validation chain. For polymorphs observed only in situ at high pressure, the decompression path, cooling protocol, and nitrogen chemical potential must be systematically optimized in order to evaluate the metastable retention window. From a mechanical standpoint, a high bulk modulus (B) in Re-based pernitrides does not automatically imply a high shear modulus (G). Even so, the embedded N-N units enhance the connectivity of the three-dimensional covalent network and tend to stiffen the lattice, which is generally favorable for sustaining macroscopic hardness.

2.2.3. ε-NbN

ε-NbN is a high-pressure-stable member within the B1/B3 hexagonal (NiAs-type) structural competition. Its formation exemplifies a pressure-driven evolution from a tetrahedrally coordinated covalent network to a sixfold-coordinated, densely packed motif. Under pressure, this phase exhibits excellent elastic moduli and near-isotropic mechanical behavior, making it a suitable bulk benchmark for studying the physical properties of hexagonal transition-metal nitrides. Experimentally, a multianvil high-pressure apparatus combined with ultrasonic interferometry was used to determine the elastic parameters of crystalline ε-NbN up to 30 GPa. Importantly, the synthesized specimen shows robust ambient stability after decompression: the length deviation between the recovered specimen and the initial state is within ±1 μm, with no discernible plastic deformation, indicating that the phase can be quenched and retained at ambient conditions for subsequent mechanical characterization. Vickers microhardness testing on the recovered specimen yields Hv = 21.5 GPa at the standard load of 9.8 N, in good agreement with the theoretical prediction [28].

2.2.4. δ-WN

As a prototypical WC-type member of the hexagonal nitride family, δ-WN exemplifies a pressure-/chemistry-driven crystallographic evolution from a fourfold-coordinated covalent network to a sixfold-coordinated close-packed structure. Unlike the more common NiAs-type hexagonal framework, the WC-type lattice features pronounced W-W metallic interactions within tungsten layers, while W-N bonds display a strongly ionic character. This distinctive bonding environment directly limits the shear modulus and, consequently, the macroscopic hardness ceiling. Using a nonconventional synthesis route with W2N3 as the tungsten precursor and melamine as the nitrogen source, this study produced high-quality bulk δ-WN with the WC-type structure. In situ high-pressure X-ray diffraction was employed to characterize compressibility, and the recovered specimens were subjected to Vickers microhardness testing to evaluate mechanical performance. Under the standard 9.8 N load, the recovered material exhibits a Vickers hardness Hv = 13.8 GPa. Combined experimental–theoretical analysis yields elastic constants of approximately B0 ≈ 376.7 GPa and G0 ≈ 149.2 GPa. Electronic structure analysis further indicates dominant W-W metallic bonding within the tungsten layers, highly ionic W-N bonds, and an absence of N-N covalent linkages. This bonding motif—dominated by metallic and ionic components and lacking a fully three-dimensional covalent network—directly explains why δ-WN is merely hard and not superhard, providing a mechanistic basis for understanding hardness behavior across transition-metal nitrides [29].

2.2.5. Mo-N: γ-MoN and δ-MoN

Within the same stoichiometry, the MoN system exhibits polymorphic coexistence and interconversion between cubic γ-MoN and hexagonal δ-MoN, making it an ideal internal benchmark for probing the linkage between crystal structure and macroscopic hardness. Experiments show that under 3.5–5 GPa and 1300 °C, a short 20 min HPHT dwell is sufficient to co-synthesize γ-MoN and δ-MoN and quench–recover both phases. A subsequent short anneal can lower point defect density and improve long-range order without triggering a phase transformation, thereby further optimizing mechanical performance. Powder X-ray diffraction cleanly distinguishes the two polymorphs by peak profiles and symmetry, and yields precise lattice parameters. The complete synthesis–recovery–characterization workflow demonstrates that both γ and δ are structurally stable at ambient conditions, suitable for systematic bulk property studies. Under a standardized Vickers load (recommended 9.8 N), δ-MoN consistently exhibits higher hardness than γ-MoN, establishing a robust “hexagonal > cubic” hardness sequence. Structurally, the layered close-packed topology of δ-MoN and its stronger directional Mo-N bonds enhance the shear modulus G; reducing defects and increasing order further consolidate the hardness platform of δ-MoN. Furthermore, neutron diffraction studies have provided accurate atomic positions and crystallographic parameters for δ-MoN, furnishing the structural data needed to derive Voigt–Reuss–Hill (VRH) averages B and G from reported Cij [30,31].

2.2.6. Mn-N: Mn2N0.86 and Mn3N2

In our previous study, under HPHT conditions, two representative bulk nitrides could be obtained in the Mn-N system: Mn2N0.86 and Mn3N2. The two phases differ distinctly in crystal structure, bonding characteristics, and macroscopic hardness. The case of Mn2N0.86 (P6322) shows that hardness predictions can be systematically overestimated if the metallic bonding contribution is not properly treated in theoretical models. Bonding analyses indicate mixed ionic covalent Mn-N interactions with no N-N dimers, consistent with its moderate hardness and load-stable mechanical response. By contrast, Mn3N2 (I4/mmm) exhibits a higher metallic ionic mixing fraction and accordingly lower hardness, making it a useful reference for the medium-hardness regime among low-valent transition-metal nitrides. From a structure–elasticity–hardness perspective, although both phases are synthesized near 5 GPa under comparable HPHT conditions, Mn3N2 attains higher hardness under identical loads owing to stronger Mn-N bonding and better long-range order; Mn2N0.86, due to substoichiometry and a larger metallic contribution, shows significantly lower hardness. Studying the two side-by-side establishes a methodological baseline for the low-valent TMN family: on the one hand for calibrating metallic bond corrections and valence-electron-density terms in models, and on the other for setting reproducible experimental benchmarks [32,33].

2.2.7. Ta3N5: (U3Se5/U3Te5 Type)

At ambient conditions, Ta3N5 typically crystallizes in a low-density Cmcm phase. First-principles calculations predict that, under high pressure, the system accesses two denser polymorphs with U3Se5-type and U3Te5-type structures (both in Pnma and nearly degenerate in energy). By adopting an “amorphous precursor HPHT” synthesis route-laser heating in a DAC, a direct transformation from amorphous Ta3N5 to these two dense phases can be achieved. This strategy underscores the key roles of pre-structuring and pressure-driven topological reconstruction in such systems. Placing the two Pnma phases within a structure–elasticity–hardness framework provides experimental support for high pressure unlocking new structural families. It also lays out a clear path for follow-up research: first, prepare bulk specimens; second, conduct hardness tests under standardized loading conditions; third, derive elastic tensors and corresponding moduli; and finally, regulate defects and stoichiometry. Through these steps, a quantitative structure–property relationship can be established, one that links densification, shear rigidity, and macroscopic hardness throughout the Ta-N system [34,57,67].

2.2.8. Bulk ε-Fe2N

Via the high-pressure solid-state metathesis (HPSSM) synthetic route, bulk ε-Fe2N with high densification was prepared from calcium nitride (Ca3N2) and ferrous chloride (FeCl2) precursors through a two-step HPHT process [68]. Firstly, ε-Fe2N powder was successfully synthesized under 5 GPa pressure and approximately 1073 K for a holding time of 30 min; subsequently, this powder was sintered at elevated HPHT conditions (8 GPa, 1273 K) for 30 min to obtain the dense bulk ε-Fe2N. Rietveld structural refinement based on X-ray diffraction data revealed that the bulk ε-Fe2N crystallizes in a trigonal system with the space group P312, and its lattice parameters are determined as a = 4.7767(1) Å and c = 4.4179(3) Å. For mechanical property characterization, micro-Vickers hardness measurements showed that the hardness value varies with increasing applied load and tends toward a stable plateau at an applied load of 1000 g, confirming an asymptotic Vickers hardness of approximately 6.5 GPa.

2.2.9. Stoichiometric VN, CrN, and TiN

For the preparation and property investigation of stoichiometric VN, CrN, and TiN [69], stoichiometric VN and CrN single crystals with a size range of 50–120 μm were successfully synthesized via a high-pressure ion-exchange reaction route. In addition, TiN and VN crystals were prepared via hot-press recrystallization under 6–8 GPa, 1800 °C for a holding time of 45 min.

In terms of mechanical properties, single-crystal indentation tests revealed that the asymptotic Vickers hardness values of TiN, VN, and CrN are 18 GPa, 10 GPa, and 16 GPa, respectively. Studies on phase formation indicated that pure B1-type (rock-salt) VN and CrN can be obtained under the conditions of 5 GPa, 1300 °C, and a holding time of 20 min. To further grow the single crystals, a sandwiched specimen assembly was adopted, and the process was regulated by slowly heating to approximately 1600 °C, which effectively reduced the number of nucleation sites and promoted the directional growth of crystals.

2.2.10. OsN2

The polymorphs of OsN2 exhibit a clear structure–electronic–mechanical coupling under high pressure. From first-principles enthalpy pressure relations, a pressure-induced transition from the marcasite structure (Pnnm, m-OsN2) to a simple tetragonal phase (ST-OsN2) is predicted at 220–223 GPa, in agreement with an independent report of 215 GPa. For both phases, the density of states displays a metallic character at ambient and high pressure with increasing pressure, Os-d and N-p hybridization strengthens, and DOS peaks shift away from the Fermi level, indicating a progressive increase in metallic bonding character.

A comparison of structural parameters and elastic constants shows that m-OsN2 has B/G ≈ 1.6, lying on the brittle side, while the rise of the shear modulus G under pressure is significantly suppressed by the metallic component: although the bulk modulus B increases with densification, G does not grow proportionally. Thus, in the OsN2 system, the counter-example “densification ≠ higher hardness” is concretely manifested.

Regarding hardness modeling, directly applying empirical relations developed for covalent/ionic solids to metallic systems typically overestimates hardness. Accordingly, the research introduces a metallic bond correction (effectively a penalty for the metallic fraction) [35]: the hardness Hv computed without this correction is markedly high, whereas the value Hv with the correction is substantially lower and closer to the reported Vickers hardness (the model is cross-calibrated on several metallic hard materials). Within the OsN2 polymorphs, theory predicts ST-OsN2 to have a higher nominal hardness than m-OsN2, yet both are limited by the increasing metallic contribution: as pressure rises and metallicity strengthens, the upper bounds of G and Hv become constrained.

This provides a representative counter-example for the B/G-Hexp joint analysis in Section 3: an increase in B alone cannot be taken to imply higher macroscopic hardness; G and the bonding character must be considered together. These HPHT-recovered bulk nitrides, together with their chemical formulas, space groups, synthesis P-T-t conditions, and 9.8 N Vickers hardness values, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

HPHT-recovered bulk nitrides at ambient: phase, chemical formula, space group, P-T-t, and Vickers hardness at 9.8 N. Among them, “NA” stands for not available (i.e., not provided). The “≈” values are used because the original text lacks corresponding descriptions; these values are estimated based on the trends of the load curves in the original text.

3. Hardness Models for Bulk HP Nitrides: Elastic Correlates and Applicability

3.1. Data Scope and Evaluation Framework

This section restricts the validation and comparison to experimentally recovered, ambient-retainable bulk TMNs listed in Section 2.2, which refer to bulk transition-metal nitrides synthesized under HPHT conditions and proven to be retainable at ambient pressure. These phases specifically include δ-WN, ε-NbN, γ-MoN, δ-MoN, Mn2N0.86, and Mn3N2. The Pnma polymorphs of Ta3N5 and the Th3P4-type c-Zr3N4/c-Hf3N4 serve as structural anchors for qualitative reference to bonding and elasticity, but—owing to the lack of bulk hardness data reported under a uniform load (especially 9.8 N)—they are not included in quantitative scatter-plot fitting or error analysis.

We include experimentally recovered bulk TMNs that are retainable at ambient conditions (Section 2.2) with traceable structure and mechanical data. Inclusion criteria are as follows: (i) bulk specimens synthesized under HPHT/DAC/LVP and quenched to ambient; (ii) phase identity confirmed by XRD/Rietveld (and Raman/IR where relevant); (iii) Vickers hardness at 9.8 N (plateau regime), or sufficient multi-load data to interpolate/extrapolate to 9.8 N; or (iv) elastic parameters available from ultrasound/Brillouin or a complete set of Cij enabling VRH B and G. Exclusion criteria are as follows: (a) thin-film data (used only for mechanistic context), (b) absence of bulk Hv at or reducible to 9.8 N, (c) incomplete elastic constants preventing VRH, or (d) ambiguous phase/stoichiometry. Accordingly, Pnma-Ta3N5 and Th3P4-type c-Zr3N4/c-Hf3N4 are retained as qualitative structural anchors but excluded from quantitative fits due to the lack of bulk Hv reported under a uniform load.

For hardness, we prioritize the Vickers hardness (Hv) plateau value, which is the regime where hardness becomes load-invariant; 9.8 N is used as the primary reference load. When multiple loads are reported in the literature, we obtain the effective 9.8 N value by interpolation or trend-based extrapolation to avoid load-dependent systematic bias. For elasticity B and G, we follow an “experiment-first, computation-supplemented” principle: ultrasonic interferometry and Brillouin scattering are preferred; in the absence of measurements, DFT elastic constants (Cij) are converted to VRH averages (B, G) to ensure internal consistency and comparability. Unless otherwise stated, the elastic constants derived from DFT are calculated at 0 K. For TMNs with metallic properties, the difference between room-temperature and 0 K elastic moduli is typically small, so the VRH-averaged B and G values obtained from DFT can be used directly for comparisons between studies, with preference given to experimental data from ultrasound or Brillouin scattering when available. Throughout this review, “theory” refers to first-principles DFT calculations or DFT-derived descriptors (e.g., elastic constants used to obtain VRH B and G; charge/bond metrics). Classical MD is treated as complementary for finite-temperature and microstructure-sensitive responses, but its results are not included in the quantitative hardness benchmarks because of interatomic-potential dependence and limited transferability across TMN families.

3.2. Decoupling of B and Hv in HPHT Nitrides

In evaluating hardness in HPHT nitrides, the lack of synchronicity between B and Hv is a central issue that must be clarified. Physically, B measures resistance to hydrostatic volume compression and is governed primarily by atomic packing density and the short-range stiffness of chemical bonds. By contrast, Hv—a prototypical elasto–plastic response—depends more sensitively on resistance to shear deformation; at the microscopic level this involves the nucleation and motion of dislocations, and its direct elastic correlate is G rather than B.

In TMNs this distinction is especially pronounced. Even when HPHT processing densifies the lattice, thereby raising B through bond shortening, the presence of significant metallic bonding (stemming from the delocalized d-electron character of transition metals) and off-stoichiometry/vacancy defects can markedly weaken directional bonding. As a result, G often fails to increase in step with B, and may even decline. Taking the polymorphs of OsN2 as an example [26,35], under pressure, the increase in crystal density leads to a systematic rise in the B; at the same time, the enhanced density of states at the Fermi level strengthens the metallic character of the material, and this enhanced metallic character limits the maximum achievable value of the G. Ultimately, the macroscopic indentation Hv falls far short of the hardness expectation that a “high bulk modulus” would otherwise imply. Only after introducing explicit metallic bond corrections in hardness models such as the metallicity factor (fm) and exponential correction proposed by Guo et al. [54]. for TMNs do theoretical predictions align with experimental measurements.

This behavior is not an outlier but a general feature of TMNs’ B-Hv decoupling, consistent with prior classic results. Guo et al. [54]. explicitly showed that metallic bonding diminishes shear resistance and must be accounted for via a dedicated correction term. Chen et al. [56] further demonstrated that indentation hardness correlates more directly with G, whereas B influences hardness only indirectly through the Pugh ratio (k = G/B); B alone cannot serve as a criterion for high hardness.

3.3. Gao Model—Hardness Correlation Based on Bond Density and the Homopolar Band Gap

The hardness model proposed by Gao et al. [53] is centered on the core idea that the hardness of a covalent crystal is regarded as the sum of the resistances exerted by all covalent bonds per unit area against indenter-induced deformation. A key step of this model involves stripping off the ionic contribution of chemical bonds, retaining only the homopolar band gap (Eh) that is directly related to covalent bond strength. Through closed-form expressions, the model further establishes an explicit correlation between hardness and microscopic bond parameters.

Gao et al. express Vickers hardness as the product of an effective bond areal density, a homopolar (covalent) bond-strength scale, and an exponential penalty for ionicity:

with two algebraically equivalent working forms,

where is the effective number of bonds per unit area, is the bond length (Å), is the valence-electron density (eÅ−3), and is the Phillips ionicity. For multibond crystals, geometric averaging is used, with is the optical gap, is the homopolar scale, in practice, and represents the proportional coefficient.

A notable advantage of this model lies in its realization of the quantitative correlation between a macroscopic mechanical property and microscopic bond parameters (bond length, bond density, ionicity) for the first time. It does not rely on elastic modulus; instead, hardness trends can be predicted solely using crystal structure data (e.g., lattice constants, coordination numbers). This makes the model particularly suitable for hardness ranking of systems dominated by covalent or polar covalent bonding.

However, the application of this model in TMNs requires strict delineation of scenarios, and it is not recommended to use it for “absolute value” predictions in TMNs with significant metallicity. Its core limitation lies in the failure to account for the metallic bond component formed by the delocalization of d-electrons in transition metals: metallic bonds reduce the effective covalent bond density of the crystal, and the model’s only ionic correction term cannot compensate for this effect. Consequently, when the proportion of metallic bonds is significant, the model exhibits a systematic overestimation of hardness predictions. For instance, δ-WN has a measured Hv of approximately 13.8 GPa due to the presence of significant W-W metallic bonds, yet if the model ignores the effect of these metallic bonds, it predicts a much higher hardness than the experimental Hv [29,53]. As for Mn2N0.86, its nitrogen vacancies enhance the material’s metallicity, resulting in an even lower measured hardness, and the model’s overestimation bias for hardness becomes more pronounced as a result. For Mn2N0.86, where nitrogen vacancies enhance metallicity, the measured hardness is even lower, and the model’s overestimation bias becomes more pronounced [32]. Therefore, when using this model to evaluate TMNs synthesized via HPHT methods, it is first necessary to confirm whether the system is dominated by covalent or polar covalent bonding. If the specimen has a significant proportion of metallic bonds or prominent defects, the model’s prediction results cannot be used as a reference for absolute values. Instead, they can only assist in trend analysis when combined with other data, and the prediction results must be interpreted with caution.

3.4. A Fully Ab Initio Hardness Model

The hardness model proposed by Šimůnek in 2006 is the first hardness calculation method entirely based on ab initio principles [52]. Its core innovation lies in starting from the charge density at the atomic scale, defining two key physical quantities—namely atomic reference energy (ei) and bond strength (Sij)—and by integrating and correlating these two microscopic parameters, it establishes a quantitative relationship between macroscopic hardness and the bonding characteristics of the crystal.

Among these quantities, the atomic reference ei characterizes the potential energy of an atom to attract surrounding valence charges in the crystal, while the bond Sij quantifies the resistance capacity of chemical bonds between atoms. Both of these quantities must be determined through charge density integration derived from ab initio calculations, and the reliability of charge density data serves as a core prerequisite for the application of this model.

Šimůnek defines a bond strength Sij built from reference atomic energies ei and coordination, and assembly hardness as a product over bonds with an ionicity penalty:

where is the valence-electron number, is the radius of a neutral sphere containing the valence charge, is the bond length, and is the coordination number. For an elemental crystal, therefore, in the simplest crystal structure, the crystal that contains only one type of chemical bond in its structure, its hardness can be expressed by the following formula:

In the formula, Ω denotes the volume of the primitive cell and C denotes the proportional constant. And for binaries (generalizable to multibond systems),

In the formula, the ionicity penalty adopts the geometric/arithmetic-mean interpretation, and is the general multicomponent expression and the exponent (where n usually refers to the number of components in the multicomponent system or a specified integer associated with the model).

A notable advantage of this model lies in its clear physical meaning and microscopic interpretability: all parameters are directly derived from charge density without relying on empirical values, and it supports “bond-by-bond decomposition” analysis—by comparing the Sij values of different chemical bonds, the contribution weight of each type of bond to hardness can be directly distinguished.

The application of this model in TMNs needs to be tailored to data availability. For systems with coexisting N-N covalent units and M-N bonds, the model can accurately decompose the contribution ratios of N-N bonds and M-N bonds to hardness when high-quality ab initio charge density data are available. However, if only lattice constants and atomic occupancy information are accessible, and there are no reliable charge density integration results, it is not recommended to force the application of the model. In such cases, the atomic reference ei must be estimated based on empirical values. This approach is prone to causing inaccurate calculation of bond Sij, as discrepancies may arise between the assumed atomic potential field and the actual crystal environment. Ultimately, this inaccuracy leads to deviations between the predicted hardness values and experimental results.

3.5. Guo’s Model: Incorporating Metallicity/d-Electron Corrections into the Gao Framework

The hardness model proposed by Guo et al. [54] is essentially a key optimization based on the “bond parameter-hardness” correlation framework of the Gao model, targeting the unique bonding characteristic of the “covalent-ionic-metallic bond mixture” in TMNs. Its core breakthrough lies in incorporating the effects of the metallicity factor (fm) and the orbital configuration of d-electrons in transition metals, thereby breaking the limitation of the Gao model which only applies to purely covalent and weakly ionic systems. Particularly for “TMNs with prominent metallic bonds or vacancies”, this model can explain both qualitatively and semi-quantitatively the core phenomenon that G is capped by metallic bonds and the Hv is lower than the expectation for purely covalent systems.

Guo et al. retain Gao’s bond-density picture but subtract a metallicity term that accounts for free-electron screening and d-electron effects in covalent compounds with metallic components:

where , carry the same meanings as in Gao, while quantifies the metallic fraction of states near EF. For multibond crystals, geometric averaging applies to the bond-resolved contributions.

The core improvements of this model center on matching the bonding and elastic properties of TMNs, which directly serve the accurate correlation between G and Hv. For bulk TMNs dominated by metallic bonds or containing vacancies—specifically including δ-WN with W-W metallic bonds, Mn2N0.86 (where metallicity is enhanced by nitrogen vacancies), and Mn3N2 (where Mn-N bonds have partial metallic character)—the consistency between the predicted values of the Guo model and the experimental hardness plateau values is far higher than that of the Gao model. The key reason lies in its ability to capture the critical mechanism of G being capped by metallic bonds. Taking δ-WN as an example, the Gao model, which fails to consider the constraint of W-W metallic bonds on G, assumes that G increases synchronously with bond density. In contrast, after the Guo model incorporates the fm correction, it quantifies the capping effect of W-W metallic bonds on G through fm. This, significantly, clearly reflects the logic that G is restricted by metallic bonds and Hv is lower than the covalent expectation.

For the special case of densification without increased hardness, take OsN2 polymorphs as an example: high-pressure synthesis leads to unit cell densification (increasing the B), but the d-electrons of Os cause an increase in the density of states at the Fermi level (DF) and fm. As a result, metallic bonds significantly “cap” the growth space of the shear modulus G. Without the fm correction, the model overestimates G and thus predicts an excessively high hardness; after incorporating the fm correction, the model not only accurately reflects the experimental phenomenon of “increasing B but restricted G and Hv” but also semi-quantitatively determines the extent to which metallic bonds constrain the upper limit of G. This provides a direct bonding-level explanation for the asynchrony between densification and hardness.

3.6. Rapid Screening Method Based on Electronegativity and Bond Hardness

The hardness model proposed by Li et al. [55] has a core physical idea: starting from the “electron retention capacity” of chemical bonds, it directly correlates macroscopic hardness with microscopic electronegativity and crystal structure parameters. First, the model redefines atomic electronegativity according to the actual chemical environment of atoms in covalent crystals: taking the Pauling electronegativity of tetrahedral carbon (2.5) as the benchmark, it derives the formula = 0.481(where 0.481 is the calibration coefficient) based on the number of valence electrons of the atom (nj) and the covalent radius of the crystal (). This ensures that the electronegativity value can reflect the binding strength of the atom to bonding electrons in the crystal. Li et al. relate hardness to bond electronegativity (electron-holding energy of a bond) and bond density , again with an ionicity penalty. Using the Knoop scale for calibration,

Key definitions are as follows: (i) elemental electronegativity = 0.481 valence electrons and crystalline covalent radius ; (ii) bond electronegativity

(iii) bond density (number of covalent bonds per unit volume), and (iv) ionicity indicator

For multibond crystals with X bond types, a geometric sum gives

where .

Among the model’s key calculations, the product of “bond electronegativity × bond density” directly quantifies the “electron retention capacity of chemical bonds per unit volume”, while the ionicity correction term is used to mitigate the reduction effect of ionicity in heterogeneous bonds on electron retention capacity. The core advantage of this model lies in rapid screening and trend judgment: it does not rely on ab initio charge density calculations or complex elastic parameter fitting. Instead, it can quickly evaluate the relative hardness of materials with different compositions or coordination configurations using easily accessible basic parameters (such as atomic electronegativity, coordination number, and unit cell volume), providing preliminary guidance for the synthesis direction of high-pressure and high-temperature TMNs.

The model can quickly predict the relative hardness order of different structures or coordination configurations within the same system through differences in bond electronegativity, providing a reference for prioritizing structural regulation in HPHT synthesis. It should be noted that this model cannot be used alone as a tool for predicting absolute hardness: because it adopts an empirically calibrated electronegativity scale and correction coefficients, and fails to consider the metallic bond component caused by the d-electrons of transition metals, the absolute hardness values calculated by the model lack direct experimental verification. Therefore, in practical applications, it is necessary to conduct parallel verification by combining it with the correlation between hardness and shear modulus Hv and G, and indirectly verify the rationality of trends through elastic parameters so as to avoid drawing conclusions about absolute hardness based solely on this model.

3.7. Chen Model—Hardness Correlation Formula Based on Elastic Moduli

The hardness model proposed by Chen et al. [56] takes as its core establishing a quantitative correlation between hardness and elastic moduli G and B based on the “coupling mechanism of elastic deformation and plastic response”. It formulates two sets of core equations for materials with different mechanical behaviors, providing an elasticity-driven reference benchmark for hardness evaluation of “brittle-ductile transition” materials such as transition-metal nitrides (TMNs).

This model improves on Teter’s model, and both sets of its equations are derived based on Vickers indentation geometry and elasticity mechanics: (1) For materials “dominated by brittle fracture or elastic deformation” (e.g., high-pressure–high-temperature (HPHT)-synthesized bulk ceramics with no obvious plastic flow, and bulk metallic glasses), Teter’s model proposes a linear correlation between hardness and shear modulus [70]:

Its physical essence is as follows: when a material is dominated by elastic shear deformation during indentation, with no significant dislocation motion or plastic accumulation, hardness is directly determined by the shear modulus; the shear modulus reflects the material’s resistance to shear deformation, and the essence of indentation hardness is precisely the macroscopic response to “local shear deformation”. This study verified this relationship using experimental data of 37 types of bulk metallic glasses, with the deviation between calculated and measured hardness values within 10%. For polycrystalline bulk materials (systems with grain boundaries, slight plastic deformation, or brittle–ductile transition), the model introduces the Pugh ratio k = G/B classic parameter quantifying a material’s brittle–ductile property (the larger the k value, the more brittle the material) and proposes the modified formula

The core design of this formula is to balance G and brittle–ductile regulation k: when the material is highly brittle (e.g., Th3P4-type c-Zr3N4 synthesized under high pressure and high temperature), k approaches a constant, and the formula degenerates into an approximate linear correlation between Hv and G; when the material exhibits slight ductility (e.g., δ-WN containing weak metallic bonds), k decreases, and the k2 term weakens the contribution of G to hardness, so as to match the hardness reduction caused by actual plastic deformation. This study determined the exponent and constant term through fitting with measured data of polycrystalline materials such as diamond, c-BN, WC, and AlN, and the consistency between calculated and experimental hardness values covers the hardness range of 2–100 GPa.

The application of this model in TMNs should focus on “elasticity-driven correlation” as the “primary reference line” for hardness evaluation, with specific usage as follows. First, prioritize comparing the measured hardness Hv-G data points of the target TMN with the linear line Hv ≈ 0.151G. For example, for bulk-synthesized TMNs such as δ-WN, ε-NbN, γ-MoN, δ-MoN, Mn2N0.86, and Mn3N2, first obtain the reliable shear modulus G via ab initio calculation or ultrasonic interferometry, then calculate the theoretical value of 0.151G. If the measured Hv is close to this theoretical value (deviation <15%), it indicates that the material is dominated by elastic fracture, with no significant microdefects affecting hardness; if there is a systematic deviation (e.g., the measured Hv is much lower than 0.151G), priority should be given to investigating the material’s own properties for causes—including density (porosity reduces the actual shear response, leading to lower hardness), non-stoichiometry (e.g., N vacancies in Mn2N0.86), and metallic bond fraction (e.g., W-W metallic bonds in δ-WN). These factors all weaken the effective shear modulus, causing the measured hardness to deviate from the elasticity-dominated linear relationship. Second, if the deviation between the measured Hv and 0.151G in Step 1 is large (>15%), then use the modified polycrystalline Formula (15) for calculation. Distinguish between brittleness dominance and the polycrystalline effect by comparing the fitting effects of the two sets of formulas: if the calculated value of the modified formula is closer to the measured Hv, it indicates that the material has brittle–ductile transition or slight plastic deformation specific to polycrystalline bulks (e.g., local plasticity caused by grain boundary sliding). If deviations still exist, further supplementary verification with micro-characterization (e.g., defect analysis via X-ray diffraction, grain boundary observation via high-resolution electron microscopy) is required to ensure the physical mechanism of hardness deviation is interpretable.

It is particularly noted that the advantage of this model in TMN applications lies in it having no need for bond parameters, only relying on elastic moduli; elastic moduli G and B can be accurately calculated via ab initio methods or directly measured through experiments, avoiding the dependence of other models on hard-to-obtain parameters such as bond length, bond density, and charge density. Therefore, it has become a benchmark reference model for hardness evaluation of high-pressure–high-temperature TMNs.

After surveying available hardness models, we retain only the elastic baselines (14) and (15) with k = G/B for dataset-wide predictions. The rationale is pragmatic: for the bulk phases reviewed in Section 2.2, B and G either are measured (ultrasound/Brillouin) or can be consistently derived via VRH from reported Cij. In contrast, other models require inputs (e.g., bond-electron density Ne, ionicity fi, metallicity factor fm, or charge density) that are not uniformly reported across papers, making unbiased, cross-study fitting impractical.

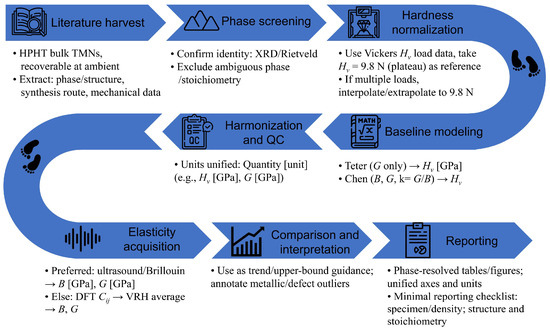

3.8. Methods of Data Assembly and Modeling

We harmonize the reported Vickers hardness to the 9.8 N plateau (interpolating/extrapolating within published load curves where needed). Elastic parameters follow an acoustic-first policy (ultrasound/Brillouin preferred); when unavailable, reported Cij values are converted to VRH averages B, G for comparability. Quantitative benchmarking uses elasticity-based baselines Teter and Chen. Only bulk data enter the regressions; thin-film values, when mentioned for the mechanism, are excluded from fitting. Figure 2 summarizes the pipeline, and Table 2 lists the model inputs/outputs.

Figure 2.

Schematic workflow used for data assembly and modeling.

Table 2.

Inputs/outputs used in phase-resolved benchmarking.

As can be seen from Table 1, some experimentally synthesized and recoverable high-pressure nitrides lack bulk hardness data measured under a unified load (9.8 N). This is primarily due to the limitations of DAC-based small-volume synthesis and restricted specimen quantities, which make standardized indentation tests difficult to perform. Therefore, only phases that meet the following criteria—enabling cross-study quantitative comparison—are retained in Table 2: they (i) possess verifiable bulk Hv plateau values measured at 9.8 N; (ii) have available bulk modulus B and shear modulus G values, preferably experimental data, or uniformly derived from reported elastic constants (Cij) via the VRH averaging method; and (iii) have complete and traceable structural confirmation. It should be noted that Mn3N2 does not satisfy the Born–Huang elastic stability criterion under 0 K DFT conditions [33,71,72]. Consequently, the B and G values of Mn3N2 derived via VRH lack physical significance, and thus the phase is excluded from the elastic–hardness comparisons in Table 2. However, Mn3N2 is retained in the main text as a mechanistic case study, specifically to illustrate the necessity of metallicity correction. The corresponding elastic-baseline comparison for these HPHT-recovered bulk nitrides is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Elastic-baseline comparison for HPHT-recovered bulk nitrides—B, G, k, and Vickers hardness at 9.8 N, with Teter reference(Reprinted form [70]) and Chen prediction (Reprinted form [56]).

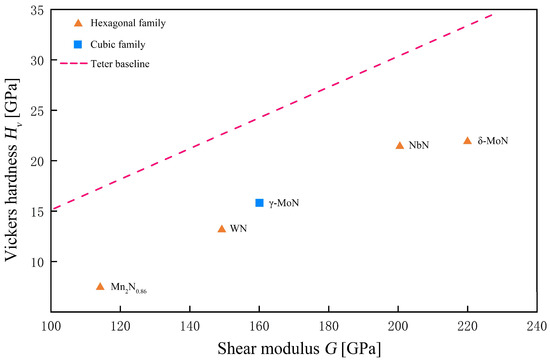

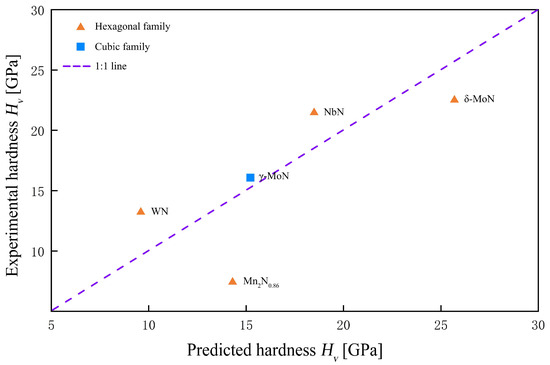

Although the specimen size is modest, Table 3 spans the key structural families we care about: hexagonal family (ε-NbN, δ-WN, δ-MoN), cubic γ-MoN, and low valent Mn nitrides Mn2N0.86. This is sufficient to test, under a unified protocol, two points: (i) indentation hardness primarily tracks the shear modulus G, and (ii) the bulk modulus B is not predictive by itself and enters via the Pugh ratio k = G/B. Based on Table 3 data, Figure 3 plots Hvexp vs. G with the Teter baseline to reveal shear-dominated behavior and downward shifts from metallicity/defects. Figure 4 is a parity plot of Chen prediction vs. the experiment (1:1 guideline), assessing the agreement of the elastic baseline and diagnosing phase-specific deviations.

Figure 3.

Experimental Vickers hardness at 9.8 N and shear modulus G for HPHT-recovered bulk nitrides, with the Teter baseline.

Figure 4.

Parity plot of Chen’s model and experimental Vickers hardness at 9.8 N for HPHT-recovered bulk nitrides, with a 1:1 guideline.

The message from this HP bulk dataset is consistent: (i) Hv correlates cleanly with G, with ε-NbN and δ-MoN falling in the shear-dominated regime. (ii) Phases with pronounced metallicity or defects (δ-WN, Mn2N0.86) lie below the Teter line and appear as “predicted-slightly-high vs measured-low” in the Chen parity plot, as expected. (iii) B alone is not diagnostic, whereas k = G/B explains hardness plateaus within a family. Collectively, this supports our practice: use the elastic baseline for cross-paper quantitation, and reserve bond-resolved models (Gao/Guo/Š-V/Li) to interpret deviations and mechanisms.

4. Conclusions and Outlook

Anchored by Figure 1 and Figure 2, we distill two actionable items: first, complete standardized 9.8 N hardness and acoustic–elastic data (or VRH-consistent B, G, from Cij) for recoverable bulks. Second, provide an outlier-correction path using defect metrology and metallicity descriptors, alongside a minimum reporting checklist and testable predictions. We conclude and outline the outlook accordingly.

- B is not a predictor of hardness on its own. Indentation hardness correlates more robustly with the shear modulus G, while B influences hardness indirectly through the Pugh ratio k = G/B. Parity plots place δ-WN, ε-NbN, and γ/δ-MoN close to or below the 0.151G line, with the multi-grain correction Hv = 2(k2G)0.585 − 3 often capturing the experimentally observed plateaus.

- Metallicity and defects are the main sources of downward deviation. In systems with appreciable metallic bonding or non-stoichiometry, G is capped and hardness falls below purely covalent expectations. This explains why densification B increases do not guarantee a higher hardness platform.

- Bond-resolved models are most useful as mechanistic lenses. Gao’s bond-density framework rationalizes trend ordering. Guo’s metallicity correction explains “high B but not hard” cases by explicitly discounting metallic contributions. Ab initio bond-strength schemes such as Šimůnek’s model are valuable when reliable charge density is available and N-N units coexist with M-N bonds.

Minimum reporting to enable cross-paper comparability should include (i) HPHT P-T-t and the quench/anneal path; (ii) phase identification with XRD/Rietveld (raw/refined files), Raman/IR where relevant; (iii) Hv–load curves with a 9.8 N reference; (iv) elastic data (either Cij or VRH B,G); and (v) composition/stoichiometry, impurity (O,C) control, density/porosity, and microstructure (grain size, texture). With such standardized reporting and simple parity analyses, bulk high-pressure nitrides can be positioned on a common elastic–hardness map, narrowing model uncertainty without heavy computation. Future studies should prioritize unified-load hardness, elastic measurements on recovered bulks, and controlled defect/oxygen management during post-processing, which together will tighten the link between bonding, elasticity, and macroscopic hardness.

Taken together, the above elasticity-anchored comparisons establish a practical baseline for bulk HPHT TMNs. To make the conclusions actionable and comparable across studies, we briefly outline application pathways, future research directions, and a minimal reporting checklist. The outline application pathway is as follows: (i) Cutting/wear tools and dies: prioritize phases with high shear modulus G and favorable k = G/B, and suppress metallicity-driven softening via stoichiometry control (N vacancies, O uptake) and grain boundary engineering. (ii) Protective/tribological coatings: use the elasticity baseline to pre-screen ambient-retained HPHT phases for load-bearing coatings, and match G and k to service loads/temperatures; avoid residual-stress artifacts. (iii) High-pressure instrumentation: select ambient-retained phases with high G and adequate toughness; report elasticity and hardness at a common load (9.8 N) to enable component-level design rules. Future research directions are as follows: Standardize Hv 9.8 N plateaus and ultrasound/Brillouin; when absent, report full Cij and VRH B, G; quantify metallicity descriptors and defect/microstructure effects; and add temperature-dependent moduli/hardness for ambient-retained phases. Minimal reporting checklist: specimen form/density; structure and stoichiometry; Hv load curve with 9.8 N plateau; elasticity (ultrasound/Brillouin or VRH from Cij); and synthesis P-T-t and quench/recovery details.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z. and J.Z.; methodology, J.Z., Z.W. and K.B.; software, S.Z.; validation, S.Z., Y.L., Z.W., J.Z., J.W. and K.B.; formal analysis, S.Z. and Z.W.; investigation, Y.L. and J.W.; resources, S.Z.; data curation, S.Z., Y.L. and J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.Z., Y.L., Z.W., J.Z., J.W. and K.B.; visualization, S.Z.; supervision, S.Z.; project administration, S.Z.; funding acquisition, S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Science and Technology Development Project of Jilin Province (20250201067GX).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| Hv [GPa] | Vickers hardness |

| G [GPa] | Shear modulus |

| B [GPa] | Bulk modulus |

| Cij [GPa] | Single-crystal elastic stiffness constants |

| P/T/t | Pressure [GPa]/temperature [K]/time [min] |

| TMN(s) | Transition-metal nitride(s) |

| HPHT | High pressure and high temperature |

| HP | High pressure |

| DAC | Diamond anvil cell |

| LVP | Large-volume press |

| VRH | Voigt–Reuss–Hill averaging |

| DFT | Density functional theory |

| MD | Molecular dynamics |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| EOS | Equation of state |

| B1/B3 | Rock-salt/zinc-blende |

| NA | Not available |

References

- Kindlund, H.; Sangiovanni, D.; Martínez-de-Olcoz, L.; Lu, J.; Jensen, J.; Birch, J.; Petrov, I.; Greene, J.; Chirita, V.; Hultman, L. Toughness enhancement in hard ceramic thin films by alloy design. Apl Mater. 2013, 1, 42104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, D.; Chen, E.; Huang, Y.; Chang, Z.; Shieu, F. Structure and characteristic studies of ZrAlNiCu films prepared by magnetron sputtering. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 39, 1278–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; An, X.; Gu, X.; Li, T.; Yang, D.; Huang, B.; Xu, Q.; Ma, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhang, K.; et al. Nanotwinned CrN ceramics with enhanced plasticity. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorwarth, K.; Watroba, M.; Pshyk, O.; Zhuk, S.; Patidar, J.; Schwiedrzik, J.; Sommerhäuser, J.; Sommerhäuser, L.; Siol, S. Reducing the oxygen contamination in conductive (Ti,Zr)N coatings via RF-bias assisted reactive sputtering. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 512, 132326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, B.; Huang, Y.; Stubbers, A.; Thompson, G.; Weinberger, C. Plasticity-fracture competition and anomalous hardness in the hard metals. Acta Mater. 2025, 298, 121350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, D.; Yu, Z. Study on the effect of multi-walled carbon nanotube (MWCNT) addition on the microstructure, mechanical and cutting performance of silicon nitride ceramic tools. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2024, 125, 106907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivashchenko, V.; Turchi, P.; Shevchenko, V.; Gorb, L.; Leszczynski, J. Structural, thermodynamic, electronic, optical and mechanical properties of amorphous BCxN1-x: A first-principles study. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2025, 662, 123542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.; Shen, X.; Allott, R.; Ertel, K.; Robertson, S.; Crookes, R.; Wu, H.; Zammit, A.; Swanson, P.; Fitzpatrick, M. Response of silicon nitride ceramics subject to laser shock treatment. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 34538–34553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.; Favaro, G.; Maros, M. Investigation of the Damage Mechanism of CrN and Diamond-Like Carbon Coatings on Precipitation-Hardened and Duplex-Treated X42Cr13/W Tool Steel by 3D Scratch Testing. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2022, 31, 7830–7842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Wang, Z.; Huang, L.; Tang, D.; Wang, J.; Yuan, J.; Chen, W. Effect of stepwise heating sintering and La2O3 doping on phase transformation, grain morphology, and mechanical properties of Si3N4 ceramics tool materials. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 47250–47263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Lu, S.; Li, Y.; Yao, Z. Nitrogen-rich Ce-N compounds under high pressure. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 9601–9607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazarbek, A.; Sagatov, N.; Omarkhan, A.; Sagatova, D.; Akilbekov, A. High-pressure stability and mechanical properties of manganese nitrides: A DFT study. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2025, 256, 113948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Lv, J.; Ma, Y. Materials discovery at high pressures. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 2, 17005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Sun, W.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; Guan, S.; Liu, P.; Wang, Q.; Li, X.; He, D.; Peng, F. Study of the compression behavior and elastic properties of HfB2 ceramics using experimental method and first-principles calculations. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 808, 151764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Luo, H.; Gao, C.; Xue, X.; Zhu, J.; Li, R.; Jin, C.; Yu, X. Superconductivity in ZrB12 under High Pressure. Metals 2024, 14, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Li, H.; Zheng, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Zhao, H.; Han, S.; Liu, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, P.; et al. Ultrastrong Boron Frameworks in ZrB12: A Highway for Electron Conducting. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1604003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.; Hu, S.; Keane, J.; Pangilinan, L.; Akopov, G.; Kavner, A.; Kaner, R.; Tolbert, S. Understanding Failure Strain and Hardness in Solid Solutions and High-Entropy Superhard Metal Dodecaborides. Chem. Mater. 2025, 37, 7079–7091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.; Lu, J.; Geng, Y.; Cheng, J.; Zhu, S.; Tan, H.; Chen, J.; Chen, W.; Chen, J.; Wang, W.; et al. Breaking the Hardness Limit of WB4: Transformation From β-B to Harder T-B. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2507050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Luo, X.; Zhang, M. Designing superhard B-N compounds with distinct conductive channels through vacancy introduction strategy. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2025, 155, 112300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzivenko, D.; Zerr, A.; Miehe, G.; Riedel, R. Synthesis and properties of oxygen-bearing c-Zr3N4 and c-Hf3N4. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 480, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerr, A.; Miehe, G.; Riedel, R. Synthesis of cubic zirconium and hafnium nitride having Th3P4 structure. Nat. Mater. 2003, 2, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasnádi, F.; Bock, F.; Ponomareva, A.; Bykov, M.; Khandarkhaeva, S.; Dubrovinsky, L.; Abrikosov, I. Thermodynamic and electronic properties of ReN2 polymorphs at high pressure. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 104, 184103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bykov, M.; Chariton, S.; Fei, H.; Fedotenko, T.; Aprilis, G.; Ponomareva, A.; Tasnádi, F.; Abrikosov, I.; Merle, B.; Feldners, P.; et al. High-pressure synthesis of ultraincompressible hard rhenium nitride pernitride Re2(N2)(N)2 stable at ambient conditions. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanoun, M.; Goumri-Said, S.; Jaouen, M. Structure and mechanical stability of molybdenum nitrides: A first-principles study. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76, 134109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamat, A.; Hector, A.; Gray, B.; Kimber, S.; Bouvier, P.; McMillan, P. Synthesis of Tetragonal and Orthorhombic Polymorphs of Hf3N4 by High-Pressure Annealing of a Prestructured Nanocrystalline Precursor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 9503–9511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, A.; Sanloup, C.; Gregoryanz, E.; Scandolo, S.; Hemley, R.; Mao, H. Synthesis of novel transition metal nitrides IrN2 and OsN2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 155501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowhurst, J.; Goncharov, A.; Sadigh, B.; Evans, C.; Morrall, P.; Ferreira, J.; Nelson, A. Synthesis and characterization of the nitrides of platinum and iridium. Science 2006, 311, 1275–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, T.; Li, X.; Qi, X.; Welch, D.; Zhu, P.; Liu, B.; Cui, T.; Li, B. Hexagonal-structured ε-NbN: Ultra-incompressibility, high shear rigidity, and a possible hard superconducting material. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tao, Q.; Dong, S.; Wang, X.; Zhu, P. Synthesis Mechanical Character of Hexagonal Phase, δ.-W.N. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 3970–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Antonio, D.; Yu, X.; Zhang, J.; Cornelius, A.; He, D.; Zhao, Y. The Hardest Superconducting Metal Nitride. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, C.; McMillan, P.; Soignard, E.; Leinenweber, K. Determination of the crystal structure of δ-MoN by neutron diffraction. J. Solid State Chem. 2004, 177, 1488–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, C.; Wang, X.; Bao, K.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, J.; Tao, Q.; Ge, Y.; Yu, Z.; Zhu, P.; et al. The Synthesis and Characterisation of the High-Hardness Magnetic Material Mn2N0.86. Materials 2022, 15, 7780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, C.; Sun, G.; Wang, X.; Bao, K.; Zhu, P.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Tao, Q.; et al. Electronic Structure and Hardness of Mn3N2 Synthesized under High Temperature and High Pressure. Metals 2022, 12, 2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamat, A.; Woodhead, K.; Shah, S.; Hector, A.; McMillan, P. Synthesis of U3Se5 and U3Te5 type polymorphs of Ta3N5 by combining high pressure-temperature pathways with a chemical precursor approach. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 10041–10044, Erratum in Chem. Commun. 2025, 61, 4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Kuang, X.; Zhong, M.; Lu, P.; Mao, A.; Huang, X. Pressure-induced structural transition of OsN2 and effect of metallic bonding on its hardness. Europhys. Lett. 2011, 95, 66005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, A.; Khan, M.; Farooq, S.; Mahmood, A.; Javed, A.; Imtiaz, A.; Khan, A.; Munawar, K. Unveiling the antistatic, anticancer and antibacterial properties of boron nitride and ionic liquid blended polyurethane elastomer films. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 346, 131413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Meindlhumer, M.; Maier-Kiener, V.; Mitterer, C.; Zhang, Z. Highly nanotwinned transition metal nitride film enabled by negative stacking fault energy. Acta Mater. 2025, 299, 121475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; Kim, N.; Hong, S. Effect of Gas Velocity on Thickness Uniformity of TiNxOy Thin Film in Atomic Layer Deposition Process. Coatings 2025, 15, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagerer, S.; Koutná, N.; Zauner, L.; Wojcik, T.; Habler, G.; Riedl, H.; Mayrhofer, P.; Hahn, R. Architecture-driven deformation and fracture behavior of nanolamellar TiN/Nb coatings. Mater. Des. 2025, 256, 114272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, B.; Kou, Q.; Xu, J. Temperature sensitivity and tunable conduction mechanisms of HfNx thin films. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 43414–43423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutlesa, K.; Keckes, J.; Daniel, R.; Zitek, M.; Tkadletz, M.; Schiester, M.; Ziegelwanger, T.; Lassnig, A.; Burghammer, M.; Meindlhumer, M. Crack arrest in nanoceramic multilayers via precipitation-controlled sublayer design. Mater. Des. 2025, 255, 114159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Liang, J.; Ni, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, D.; Jiang, X.; Ma, D. Nb-N solid solution strengthening in (FeCoNiCuNb)Nx high-entropy alloy nitride films. Vacuum 2025, 240, 114536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Glauber, J.; Lorenz, J.; Rogalla, D.; Harms, C.; Devi, A.; Nolan, M. Surface Oxidation of Transition Metal Nitrides. J. Phys. Chem. C 2025, 129, 11173–11182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabeer, N.; Paulson, A.; Pradyumnan, P. Intrinsic induction of resonant energy levels for the enhancement of thermoelectric parameters of ZnSnN2 thin films. Mater. Res. Bull. 2026, 193, 113646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, S.; Gupta, P.; Rajput, P.; Gloskovskii, A.; Gupta, M. Comprehensive Study of Structural and Electrocatalytic Properties of Ni-N Thin Films. Phys. Status Solidi-Rapid Res. Lett. 2025, e202500327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, S.; Singh, R.; Rawat, R.; Gloskovskii, A.; Gupta, M. Synthesis and Characterization of Single-Phase ReN Thin Films. Phys. Status Solidi-Rapid Res. Lett. 2025, 2500288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Rawat, D.; Hjort, V.; Mishra, A.; le Febvrier, A.; Bedanta, S.; Eklund, P.; Soni, A. Lattice Mismatch-Driven In-Plane Strain Engineering for Enhanced Upper Critical Fields in Mo2N Superconducting Thin Films. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2025, e00586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Narayana, T.; Tyagi, R.; Pant, G.; Verma, P. Recent Developments in Self-Lubricating Thin-Film Coatings Deposited by a Sputtering Technique: A Critical Review of Their Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Lubricants 2025, 13, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, W.; Wu, S.; Zhong, X. Electron induced secondary electron emission properties of the oxygen-rich aluminum nitride film. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 710, 163792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Mei, S.; Cai, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, B.; Gu, L. Microstructure and tribological properties of (AlCrTiV)Nx high-entropy alloy films prepared by magnetron sputtering. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 512, 132406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhu, L.; Wei, R.; Zhu, X. Thickness-dependent hydrogen evolution performance of 0.18Ag-Ag0.80Ni0.2NNi3 antiperovskite thin film prepared by chemical solution deposition. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2025, 20, 101150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simunek, A.; Vackár, J. Hardness of covalent and ionic crystals: First-principle calculations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 85501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.; He, J.; Wu, E.; Liu, S.; Yu, D.; Li, D.; Zhang, S.; Tian, Y. Hardness of covalent crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 15502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Li, L.; Liu, Z.; Yu, D.; He, J.; Liu, R.; Xu, B.; Tian, Y.; Wang, H. Hardness of covalent compounds: Roles of metallic component and d valence electrons. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 104, 23503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, X.; Zhang, F.; Xue, D. Electronegativity identification of novel superhard materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 235504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Niu, H.; Li, D.; Li, Y. Modeling hardness of polycrystalline materials and bulk metallic glasses. Intermetallics 2011, 19, 1275–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, T.; Lu, D.; Domen, K. Synthesis of Structurally Defined Ta3N5 Particles by Flux-Assisted Nitridation. Cryst. Growth Des. 2011, 11, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaka, T.; Ikenobe, T.; Hiroi, Z.; Yamane, H.; Yamada, T. Synthesis of ε-NbN and δ-NbN by metathesis reaction of NaNbO3 and BN. Chem. Lett. 2024, 53, upae154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Kuge, N.; Sekiya, T.; Yamane, H. Synthesis of NbN faceted grains from oxides and boron nitride with sodium. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 14525–14529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, A.; Kihira, S.; Takeda, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Harada, T.; Ueno, K.; Fujioka, H. Crystal-Phase Controlled Epitaxial Growth of NbNx Superconductors on Wide-Bandgap AlN Semiconductors. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2270174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, R.; Yamane, K.; Tadano, T.; Terashima, K.; Shinmei, T.; Irifune, T.; Takano, Y. Emergence of Superconductivity at 20 K in Th3P4-type In3-x S4 Synthesized by Diamond Anvil Cell with Boron-Doped Diamond Electrodes. Chem. Mater. 2025, 37, 1648–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, S.; Ali, Z.; Altuijri, R.; Abu El Maati, L.; Khan, S.; Trukhanov, S.; Zubar, T.; Sayyed, M.; Tishkevich, D.; Trukhanov, A. First-principles study of the rare earth anti-TH3P4 type zintles for opto-electronic and thermoelectric applications. Phys. B-Condens. Matter 2023, 670, 415353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, T.; Dzivenko, D.; Riedel, R.; Chauyeau, T.; Zerr, A. Synthesis of cubic zirconium(IV) nitride, c-Zr3N4, in the 6–8 GPa pressure region. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 20028–20032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibel, E.; Xie, W.; Gibson, Q.; Cava, R. Synthesis, Structure, and Basic Magnetic and Thermoelectric Properties of the Light Lanthanide Aurobismuthides. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 3583–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bykov, M.; Bykova, E.; Aprilis, G.; Glazyrin, K.; Koemets, E.; Chuvashova, I.; Kupenko, I.; McCammon, C.; Mezouar, M.; Prakapenka, V.; et al. Fe-N system at high pressure reveals a compound featuring polymeric nitrogen chains. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Harran, I.; Jia, M.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Wu, N. Prediction and characterization of the marcasite phase of iron pernitride under high pressure. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 702, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Density functional study of the high-pressure behavior of Ta3N5. Phys. B-Condens. Matter 2016, 494, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Yin, Y.; Hong, F.; Zhu, P.; Yu, X. Magnetic, Electronic, and Mechanical Properties of Bulk ε-Fe2N Synthesized at High Pressures. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 12591–12597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yu, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Leinenweber, K.; He, D.; Zhao, Y. Synthesis, Hardness, and Electronic Properties of Stoichiometric VN and CrN. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teter, D. Computational alchemy: The search for new superhard materials. Mrs Bull. 1998, 23, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Feng, J.; Zhou, C.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, R. Mechanical properties and chemical bonding characteristics of Cr7C3 type multicomponent carbides. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 109, 23507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Chong, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, R.; Yuan, W.; Feng, J. The stability, electronic structure, elastic and metallic properties of manganese nitrides. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 1620–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).