Abstract

The electrical behavior of the electric smelting furnace (ESF) in ferronickel production is primarily governed by slag conductivity, which is closely linked to ionic mobility. This study examines the relationship between slag viscosity and electrical conductivity through experimental measurements and thermodynamic modeling. The viscosity and conductivity of actual ferronickel slags were measured, and synthetic slags with similar compositions were analyzed to isolate the effects of individual oxides. Results show that viscosity decreases with increasing basicity and FeO content, while solid-phase formation at lower temperatures sharply increases viscosity. Electrical conductivity rises with temperature due to reduced viscosity and enhanced ionic transport, and increases markedly up to 17 wt.% FeO owing to higher Fe ion concentrations and partial electronic conduction. Actual ferronickel slags exhibited slightly higher conductivity than synthetic ones, likely due to minor oxides such as NiO. These findings provide insight into the coupled thermophysical and electrical behavior of ferronickel slags, offering guidance for optimizing ESF efficiency and operation.

1. Introduction

With the recent surge in global demand for secondary batteries, the production of nickel (Ni) has significantly increased worldwide [1,2,3]. In the early 20th century, blast furnaces were predominantly used for nickel smelting; however, since the latter half of the century, most smelting operations have transitioned to systems that combine rotary kilns with electric smelting furnaces (ESFs). In such processes, carbon-based reductants are employed in both the rotary kiln and the furnace, and numerous studies have focused on controlling the reduction rates of nickel, iron, and other elements [4,5,6,7]. The global decline in nickel ore grade and the continual rise in energy costs compounded by increasing carbon emission penalties have intensified interest in improving energy efficiency in nickel extraction processes. In particular, pyrometallurgical routes employing ESFs have been the focus of numerous studies aimed at reducing electrical power consumption. To this end, various strategies have been proposed to minimize heat losses from the furnace system [8,9]. Among these, reducing the sensible heat loss through slag tapping has emerged as a key factor in enhancing furnace energy efficiency. The temperature of discharged slag and energy consumption are strongly influenced by slag composition, furnace design, and operating conditions, and thus has become a major research topic in process optimization [10,11,12]. There are also complex electric and electronic interactions among the slag, electrodes, and the molten metal bath [13,14].

Within a typical ferronickel smelting furnace, materials are stratified based on their specific gravity. At the bottom lies a molten ferronickel (metal) layer, followed by a molten slag layer, and on top resides a calcined ore (calcine) layer (Figure 1). Electrical conduction between electrodes is facilitated through the conductive molten slag and metal, and two primary current paths are commonly considered: Path A, the main conduction route (electrode → slag → molten metal → slag → electrode), and Path B, an alternative route (electrode → slag → electrode), as illustrated in Figure 1. Industrial ESFs are typically designed to favor current flow through Path A by adjusting electrode spacing and slag layer thickness [15,16]. The dominant heat sources for ore melting in the furnace are arc heating at the electrode tips and resistive heating within the slag. The total electrical resistance of the furnace system can thus be described as the sum of the arc resistance (Rarc) and the bath resistance (Rbath), represented as: Rtotal = Rbath + Rarc.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of electrical current paths in the ESF. Two principal current paths are depicted: Path A (electrode → slag → molten metal → slag → electrode) and Path B (electrode → slag → electrode), highlighting the respective roles of calcine and slag in conducting current.

During furnace operation, the total electrical resistance applied to the electrodes is actively controlled, while the balance between arc heating and resistive heating within the slag layer is simultaneously regulated. A common approach involves adjusting the applied voltage to modulate the distance between the electrodes and the slag surface. However, accurately quantifying the resistivity of molten slag remains a challenge, making it difficult to precisely control arc resistance based solely on total resistance measurements. Key variables that strongly influence the total resistance and current distribution include the inter-electrode spacing, slag layer thickness, intrinsic slag resistivity, and arc length. Electrical conductivity within molten slag is governed by two primary mechanisms: ionic conduction and electronic conduction. Ionic conduction is strongly affected by the viscosity of the slag, which in turn is directly related to the mobility of constituent ions. In contrast, electronic conduction is significantly influenced by the presence of transition metal oxides, particularly iron oxides such as FeO and Fe2O3. Three major factors affect the electrical conductivity of slag in actual furnace operations. First, slag temperature critically determines its viscosity, which has a direct impact on the mobility of ionic species and thus on ionic conductivity [17,18]. As the temperature decreases near the liquidus line, a critical viscosity temperature (CVT) is often observed, beyond which viscosity rises sharply due to the formation of solid phases. Correspondingly, abrupt changes in electrical conductivity can occur [19,20]. Second, slag composition, particularly its basicity (defined as the ratio of basic oxides such as CaO and MgO to acidic oxides like SiO2), plays a significant role. An increase in basicity induces partial depolymerization of the silicate network structure, thereby enhancing ion mobility and altering the ionic conductivity of the melt [17,21,22,23,24]. Third, the FexO content in slag affects the relative contribution of electronic conduction. At low concentrations of FexO, ionic conduction via Fe2+, Mg2+, and Ca2+ diffusion predominates. However, above a certain threshold, charge transport through charge hopping mechanisms involving FexO becomes dominant. Since electronic conduction is more effective when accompanied by short-range ion displacement, the conductivity tends to increase more rapidly as slag viscosity decreases at elevated temperatures [25,26,27,28,29].

While many studies have been conducted to evaluate the electrical conductivity of slags in various electric furnaces, investigations focusing specifically on the electrical behavior and current distribution within ferronickel electric furnaces remain very limited despite the recent surge in nickel production using such systems. This lack of fundamental understanding is especially critical given the growing reliance on electric smelting furnaces for large-scale ferronickel production. In this study, the influence of slag composition and temperature on the electrical conductivity of ferronickel slags is systematically examined, with particular emphasis on actual smelting slags rather than simplified synthetic systems. The viscosities of synthetic slags were calculated using FactSage to analyze general compositional trends among major oxide components, while the viscosities and electrical conductivities of actual smelting slags were experimentally measured to obtain reliable data and identify key influencing factors under realistic furnace conditions. Unlike previous studies that primarily focused on melting behavior or artificial slag modifications such as CaO addition [7,18,28], this work establishes a direct correlation between viscosity and electrical conductivity in real ferronickel slags. The objective of this study is to provide fundamental data that can be utilized for both furnace operation and design optimization. Furthermore, the effects of chemical composition and temperature on slag viscosity, one of the dominant factors influencing electrical conductivity, are systematically investigated. Through this comprehensive analysis, the relationship between viscosity and electrical conductivity in ferronickel slags is quantitatively established. In addition, a practical expression for slag resistance is proposed, offering valuable insights for determining optimal operating conditions in electric smelting furnaces for ferronickel production. The unique aspects and practical significance of this work have been further emphasized in the revised manuscript to highlight its originality and contribution.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, synthetic slags with chemical compositions analogous to those of typical ferronickel slags were prepared to systematically investigate the effects of slag composition and temperature on viscosity and electrical conductivity. The chemical compositions of the synthesized slags are listed in Table 1. All chemical composition analyses were conducted using XRF (X-ray Fluorescence, Rigaku Simultix 15, Tokyo, Japan). Specifically, the FeO content was varied at 7, 15, and 17 wt.%, while the MgO/SiO2 mass ratio (denoted as M/S) was adjusted to 0.51, 0.55, and 0.66. The M/S ratio effectively represents the slag basicity, which is commonly defined as the ratio of basic oxides to acidic oxides. These compositions were selected to closely replicate the primary constituents of slags generated in electric furnaces during the smelting of laterite ores, where FeO, MgO, and SiO2 typically account for more than 90% of the total slag mass [11].

Table 1.

Chemical compositions of synthetic slags and the corresponding experimental temperatures.

The temperature range for electrical conductivity measurements was set between 1450 °C and 1600 °C, which is consistent with the typical tapping temperatures (1500–1600 °C) observed in industrial ferronickel electric furnaces.

In addition, the viscosities of synthetic slags were calculated using FactSage 8.3, a widely accepted tool for high-temperature process modeling, because the SiO2–MgO–FeO system represents a relatively simple ternary composition for which the latest FactSage database provides sufficient and reliable viscosity data [30]. The typical deviation between FactSage-predicted and experimental values is approximately 20%, which is comparable to the variation often observed among independent experimental measurements under identical conditions [31,32,33,34,35]. However, at lower temperatures near the liquidus point where solid phases begin to precipitate, the viscosity prediction accuracy decreases. To address this, the Einstein–Roscoe equation, a conventional model for estimating the viscosity of liquid-solid mixtures, was applied to improve the reliability of viscosity estimations under these conditions. In addition to synthetic slags formulated to simulate ferronickel slag compositions, actual industrial ferronickel slags obtained from commercial electric furnaces were used to investigate the effects of temperature on slag viscosity and electrical conductivity. However, for the actual smelting slags, FactSage lacks adequate interaction data for their complex multicomponent compositions; therefore, their viscosities were measured experimentally in the laboratory. The chemical compositions of the industrial slags are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Chemical compositions of ferronickel smelting slags.

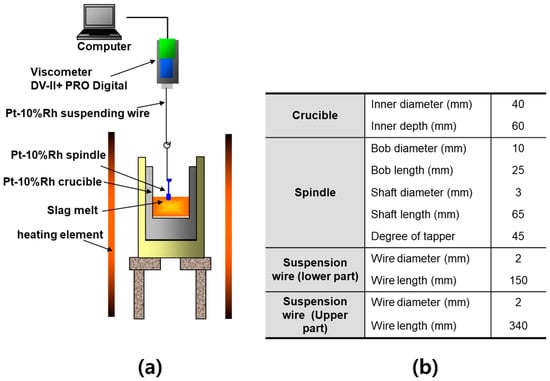

The experimental setup for viscosity measurements is schematically illustrated in Figure 2 [24,36]. To eliminate the effects of solid precipitation or complex phase formation at elevated temperatures, each slag sample was first fully melted by heating above the target temperature. Viscosity was then measured during controlled cooling. Approximately 120 g of slag was charged into a crucible, and argon gas was supplied at a flow rate of 400 cm3/min to prevent oxidation. A spindle with a diameter of 10 mm and a length of 25 mm was immersed in the slag, and viscosity measurements were conducted using a Brookfield DV-II+ PRO Viscometer (AMETEK, Berwyn, PA, USA). Measurements were taken at 1550 °C, 1500 °C, 1450 °C, and 1420 °C. Although the plan was to collect data down to 1400 °C in 50 °C intervals, a rapid increase in viscosity below 1450 °C rendered accurate measurements difficult; thus, 1420 °C was selected as the lower limit.

Figure 2.

Experimental setup for measuring the viscosity of molten slags using the rotating cylinder method: (a) Schematic illustration of the measurement principle, showing a platinum spindle immersed in molten slag contained within a platinum crucible. (b) Dimensions of the experimental apparatus, including the crucible, spindle, suspension wire, and related components.

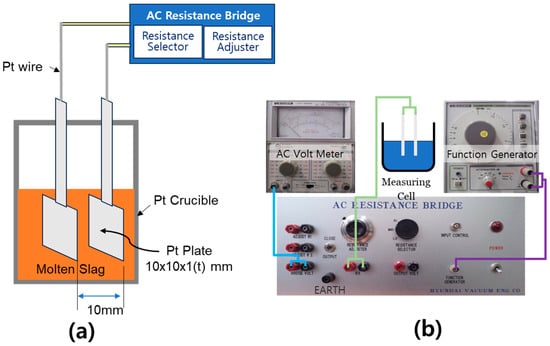

The setup used to measure the electrical conductivity of the slag is shown in Figure 3. A two-electrode method, as illustrated in Figure 3a, was adopted. Initially, experiments were conducted using a graphite crucible and Mo wire electrodes, aiming to isolate resistance between the electrodes and crucible. However, interfacial reactions between certain slag components and the crucible material led to composition changes, compromising measurement accuracy. To address this, platinum plate electrodes (1 mm thick, 1 cm × 1 cm) were employed, with a fixed electrode spacing of 1 cm to minimize interference. Slag samples were fully melted above the target temperature and gradually cooled to allow conductivity measurements under consistent thermal conditions while avoiding solidification effects. Electrical resistance was measured using a Wheatstone bridge circuit [37], and conductivity was calculated from the resistance values. An LMV-189AR AC voltmeter (Leader Electronics, Yokohama, Japan) was used for voltage measurements, while an LAG-120B function generator from the same manufacturer was employed to control the AC frequency. The combined resistance of fixed resistors R1 and R2 was set at 5 kΩ, and three modes of resistance selectors (5.6 Ω, 11.2 Ω, and 16.8 Ω) were employed. To validate the measurement system and optimize operating parameters, reference resistors (10 Ω and 17 Ω) were tested under varying input voltages (100 mV, 500 mV, and 1 V) and AC frequencies (1 kHz, 5 kHz, and 10 kHz). Results indicated that resistance values were minimally affected by variations in input voltage and frequency. Based on these findings, the optimal measurement conditions were determined to be an input voltage of 500 mV, AC frequency of 1 kHz, and variable resistance of 11.2 Ω, which yielded the most consistent and accurate results. These conditions were used for all slag conductivity measurements. It is important to note that the experimental uncertainty for electrical conductivity was approximately ±2.8%, and that for viscosity was ±3.6%, primarily due to minor temperature fluctuations during measurement and slight inhomogeneities in the slag samples.

Figure 3.

Experimental setup for measuring the electrical conductivity of molten slags: (a) Schematic diagram of the measurement principle using platinum electrodes inserted into molten slag within a platinum crucible (electrode spacing: 10 mm). (b) System configuration for electrical conductivity measurement, consisting of an AC resistance bridge, AC voltmeter, and function generator, with detailed connections to the measurement cell.

3. Results and Discussions

Effect of Basicity (M/S Ratio) on Slag Viscosity

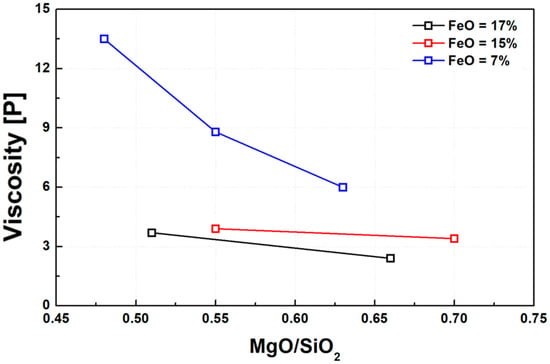

Figure 4 illustrates the variation in slag viscosity as a function of basicity, expressed as the M/S ratio. Consistent with previous studies on various slag systems [21,22,29,38], the slags used in this study exhibited a significant decrease in viscosity with increasing basicity. This trend was particularly pronounced in slags with lower FeO content. The likely explanation is that in slags with high FeO content, the silica network structure has already been substantially disrupted, thereby reducing the marginal effect of increasing basicity on viscosity reduction.

Figure 4.

Effect of M/S ratio on slag viscosity at 1600 °C under varying FeO contents.

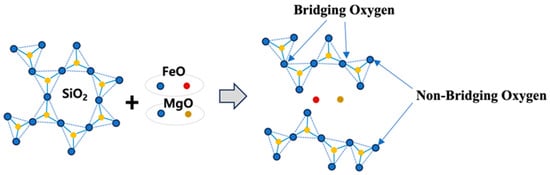

Basic oxides such as MgO and FeO act as network modifiers by supplying oxygen to break the strong covalent Si–O–Si bonds present in the tetrahedral SiO4 network, as shown in Figure 5. These basic oxides donate oxygen atoms, cleaving the bridging oxygen (BO) bonds between silicon atoms and producing non-bridging oxygen (NBO) atoms that are bonded to only one silicon atom. This depolymerization mechanism leads to the breakdown of the extended silicate network into smaller, more mobile silicate species. The increase in the NBO/T ratio (number of non-bridging oxygens per tetrahedrally coordinated atom) facilitates the formation of low-molecular-weight silicate species, thereby reducing slag viscosity and enhancing cation mobility. This structural transformation, characterized by an increase in NBO/T, has been confirmed in prior studies using Raman spectroscopy and Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy [36,39]. Moreover, the depolymerizing tendency of basic oxides is influenced by the ionic field strength (Z/r2) of the cation, where Z is the cation valence and r is its ionic radius. Smaller cations with higher valence (i.e., higher Z/r2 values) exhibit stronger depolymerization effects on the silicate structure [40].

Figure 5.

Depolymerization of silicate networks by basic oxides. Note: Blue circles represent oxygen atoms, yellow circles are silicon, red circles are iron, brown color circles represent magnesium atoms.

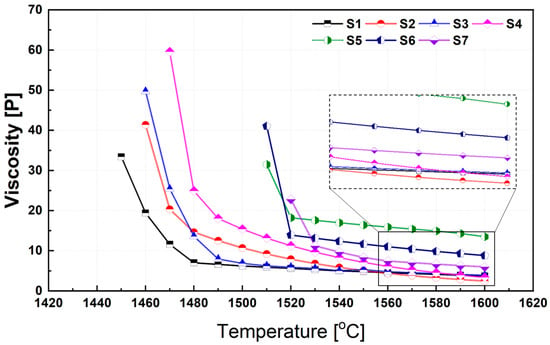

Figure 6 illustrates the temperature-dependent variation in viscosity for each synthesized slag composition. A distinct critical temperature, at which a rapid change in viscosity occurs, was observed for each composition. This transition temperature is influenced by the phase transformations that develop as the slag cools and differs depending on the slag chemistry. In general, the relationship between slag viscosity (η) and temperature (T) can be described by the Arrhenius-type equation.

where η is the viscosity (in Poise), η0 is a pre-exponential constant, Eη is the apparent activation energy for viscous flow (J/mol), R is the universal gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature (K). As shown in Figure 6 and predicted by Equation (1), all slags exhibit strong temperature dependence in viscosity. This behavior can be attributed to two concurrent phenomena occurring at elevated temperatures: (i) increased ionic mobility and (ii) partial depolymerization or weakening of the silicate network structure. At temperatures above 1500 °C, slag viscosities were calculated using FactSage. However, below this range, the formation of high-melting-point solid phases within the molten slag introduces non-negligible heterogeneity. In such cases, the viscosity of the liquid phase was first estimated using FactSage, and the overall (mixture) viscosity was then corrected using the Einstein–Roscoe equation [41], which accounts for the presence of suspended solids. In all slag systems, a sharp drop in viscosity was observed above a certain temperature threshold, which corresponds to a significant reduction in the solid phase fraction. This phenomenon is well-documented and reflects the strong sensitivity of slag rheology to the solid content in the two-phase region [19,20,41].

Figure 6.

Influence of temperature on the viscosity of synthetic slags. Note: The inset shows a magnified view highlighting the differences in viscosity values at higher temperatures.

Figure 7 shows the variation in slag viscosity with temperature for different FeO contents. When the FeO content exceeds 15 wt.%, a more pronounced viscosity drop is observed in the high-basicity slags as the temperature increases from 1550 °C to 1600 °C. This behavior is likely due to the dissolution of high-melting-point solid particles that were present in the melt at lower temperatures. In the temperature range where liquid and solid phases coexist, slag viscosity exhibits a strong positive correlation with the volume fraction of solid particles suspended in the liquid phase. As the solids dissolve with increasing temperature, the reduction in solid fraction leads to a significant decrease in the overall viscosity.

Figure 7.

Temperature dependence of slag viscosity for different FeO contents: (a) 17 wt.% FeO, (b) 15 wt.% FeO, (c) 7 wt.% FeO. Each graph illustrates the viscosity trend over the temperature range of 1550–1600 °C.

Furthermore, a general trend of decreasing viscosity with increasing FeO content was observed across all compositions. This can be attributed to the role of FeO as a network modifier, which weakens the silicate network structure and enhances slag fluidity. The viscosity-reducing effect of FeO becomes especially evident at lower temperatures, where structural depolymerization significantly contributes to lowering the melt viscosity. These observations underscore the dual role of FeO in slag systems both as a fluidity enhancer by breaking down silicate linkages and as a temperature-sensitive modifier that facilitates the dissolution of solid phases, particularly in high-basicity slags.

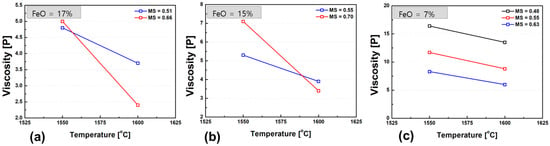

Figure 8 compares the experimentally measured average viscosities of three ferronickel slag samples (FeNi_Slag1 to FeNi_Slag3, as listed in Table 2) within the temperature range of 1420–1550 °C, against calculated values obtained using FactSage. Below 1420 °C, a rapid increase in viscosity was observed, rendering further measurements infeasible. This sharp rise in viscosity is attributed to the sudden precipitation of high-melting-point solid phases within the slag. Based on these observations, 1450 °C can be regarded as the critical viscosity temperature for these slags, indicating the onset of significant structural transitions. The discrepancies between the calculated and experimental viscosities arise mainly from variations in the solid fraction during cooling and solidification. Around 1450 °C, a sharp increase in viscosity was observed due to the accelerated formation of solid phases within the slag. In this transition region, the deviation between calculated and experimental values tends to increase because of the limited thermodynamic data in FactSage and the growing influence of non-equilibrium effects. Since all calculations are based on thermodynamic equilibrium, deviations may occur under non-equilibrium conditions. The software also assumes that the entire slag system remains physically homogeneous throughout the temperature range; however, near the critical viscosity temperature (CVT), where solid phases begin to form, this assumption may not accurately represent the real behavior of partially molten slags. These discrepancies are consistent with the variability often observed among independent experimental measurements, as phase segregation and crystal formation can influence viscosity readings. Moreover, in the solid–liquid coexistence region, viscosity models such as the Einstein–Roscoe equation exhibit limited accuracy, which may further contribute to differences between calculated and measured values.

Figure 8.

Temperature dependence of viscosity in real ferronickel slags and comparison with calculated values over the range of 1420–1550 °C.

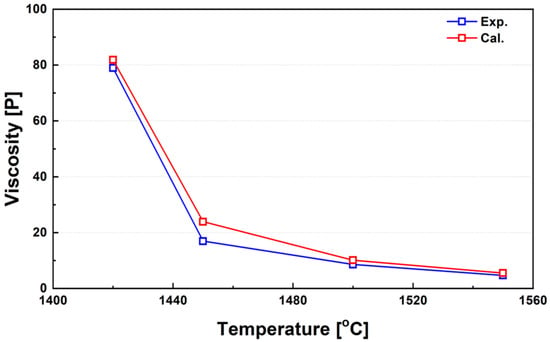

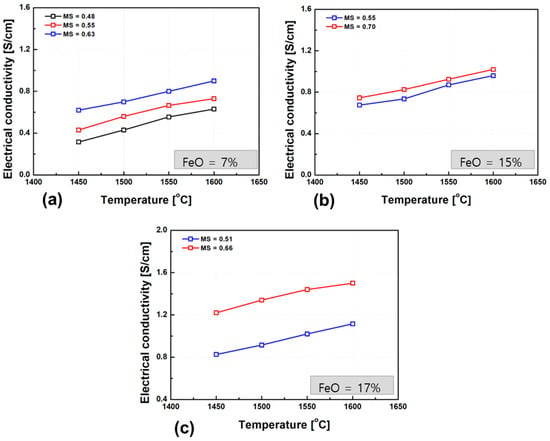

Figure 9 presents the experimentally measured electrical conductivity of the slags as a function of temperature. As with other silicate-based slags, the conductivity increased markedly with temperature, confirming the thermally activated behavior of ion transport. Notably, slags with similar FeO contents and basicity (M/S ratio) exhibited comparable conductivity slopes (i.e., temperature dependence), indicating a consistent ionic conduction mechanism. The temperature dependence of ionic conductivity can be described by the Arrhenius-type expression, as shown in Equation (2) [42].

where σi is the ionic conductivity (S/cm), A is the pre-exponential constant, Ei is the activation energy for ionic conduction (J/mol), R is the universal gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature (K). As shown in Equation (2), ionic conductivity increases with temperature in a manner analogous to viscosity reduction, reflecting the thermally activated nature of ion transport in molten slags.

Figure 9.

Temperature dependence of electrical conductivity in slags with varying FeO contents: (a) 7 wt.% FeO, (b) 15 wt.% FeO, (c) 17 wt.% FeO. The plots depict the effect of temperature (1450–1600 °C) on conductivity, emphasizing the role of FeO content.

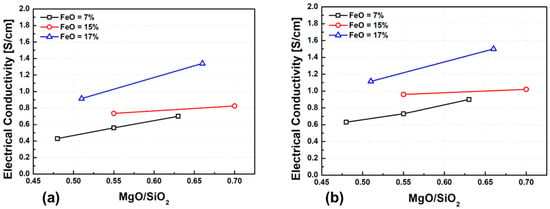

Figure 10 presents the experimental results of electrical conductivity as a function of slag basicity, defined as the M/S ratio. An increase in MgO content leads to a clear increase in conductivity, which can be attributed to the enhanced activity of oxygen ions, partial depolymerization of the silicate structure, and an increased concentration of mobile cations. This effect is particularly pronounced when FeO content exceeds 17 wt.%, suggesting a synergistic role of Fe2+ and Mg2+ ions in promoting network breakdown and improving ionic transport.

Figure 10.

Effect of M/S ratio on electrical conductivity at different temperatures: (a) 1500 °C, (b) 1600 °C.

As discussed earlier, Fe2+ and Mg2+ act as network modifiers, weakening the silicate network and reducing viscosity. This structural depolymerization, when combined with increased basicity and higher NBO/T ratio (number of non-bridging oxygens per tetrahedrally coordinated silicon), results in enhanced cation mobility and ionic conductivity. Such trends are widely observed in silicate-based slags: increasing basicity and NBO/T leads to disruption of the polymerized network and a corresponding increase in ionic mobility. Notably, this behavior is not limited to MgO, but also appears in slags containing similar alkali and alkaline-earth oxides. The ionic conductivity of slags is primarily governed by the concentration of small, mobile cations such as Na+, Ca2+, Fe2+, and Mg2+. Previous studies on ferronickel slags have also reported similar correlations between viscosity, basicity, and the effects of multivalent cations [30]. Furthermore, the ionic conductivity due to the diffusion of basic cations can be expressed using the Nernst–Einstein equation, shown as Equation (3) [28]:

where σi is the ionic conductivity (S/cm), Ci is the concentration of ion i (mol/cm3), Di is the self-diffusion coefficient of ion i (cm2/s), Zi is the valence of ion i, F is Faraday’s constant (C/mol), R is the gas constant (J/mol·K), and T is the absolute temperature (K). Equation (3) clearly indicates that ionic conductivity is influenced by the concentration, diffusivity, and charge of each ionic species. Hence, higher valence and higher mobility cations contribute more significantly to slag conductivity.

Figure 11 presents the experimentally measured electrical conductivity of ferronickel slags as a function of FeO content. A clear trend of increasing conductivity with higher FeO concentrations was observed. This result indicates that FeO plays a significant role in enhancing both ionic and electronic conductivity within the slag. FeO contributes to ionic conduction by supplying Fe2+ ions that act as mobile charge carriers. In addition, it has the potential to facilitate electronic conduction through a charge-hopping mechanism between Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions. However, for such hopping to occur efficiently, a sufficiently high local concentration of both Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions are required to enable continuous electron transfer pathways. The observed conductivity enhancement with increasing FeO content and temperature is therefore primarily attributed to an increase in ionic concentration and mobility, rather than a dominant contribution from electronic conduction. The temperature dependence supports this conclusion, as higher thermal energy promotes ionic diffusion and reduces slag viscosity, further facilitating ion transport. Thus, although both ionic and electronic mechanisms are present, the dominant contribution to the increased electrical conductivity at elevated FeO levels is associated with enhanced ionic conduction, with electronic conduction playing a secondary role under the tested conditions.

Figure 11.

Influence of FeO content (7%, 15%, 17%) on electrical conductivity at 1500 °C and 1600 °C with M/S ≈ 0.55. Note: The graph highlights the combined effect of FeO content and temperature on both ionic and electronic contributions to conductivity.

Although this study did not observe a distinct charge-hopping phenomenon due to the relatively low FeO content, previous investigations on slag systems with FeO contents ranging from 30 to 60 wt.% have reported a significant contribution from charge hopping as a dominant conduction mechanism. For charge hopping to occur effectively, Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions must be located in close proximity, typically within 4 Å of each other, to facilitate electron transfer between adjacent sites [27,28]. Given the FeO levels in the present slag compositions, charge hopping is unlikely to be the predominant mechanism. Instead, the conduction behavior is best described as a mixed-mode transport, involving both ionic conduction and a lesser contribution from electronic conduction. Some researchers have proposed a hybrid conduction model known as Diffusion-Assisted Charge Transfer (DACT), which combines ion migration with intermittent electron transfer via hopping mechanisms under specific compositional and thermal conditions. Based on the experimentally measured conductivity values as functions of slag composition and temperature, an empirical regression model was developed, shown as Equation (4).

Electrical Conductivity (S/cm) = −3.35 + 1.21(%MgO)/(%SiO2) + 0.0414(%FeO) + 0.00196 T (°C),

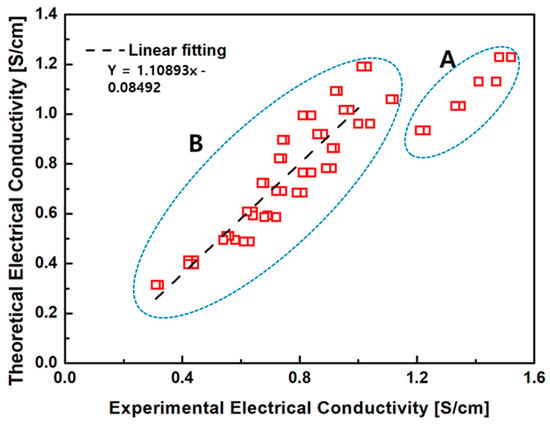

Figure 12 compares the predicted electrical conductivity values from Equation (4) with the experimental measurements. In Region B, corresponding to low FeO content and thus relatively low conductivity, the empirical model shows good agreement with the measured data. However, in Region A, where FeO content is higher, the measured conductivity values exceeded those predicted by the model. This deviation is attributed to additional conduction enhancement mechanisms activated at elevated FeO contents. Specifically, in addition to the increase in basicity and the corresponding decrease in slag viscosity, a higher density of charge-hopping sites (Fe2+/Fe3+ pairs) becomes available, leading to a non-linear increase in total conductivity that exceeds ionic contribution alone.

Figure 12.

Comparison between measured (red boxes) and predicted (dashed line) values of electrical conductivity (S/cm). While the data exhibit overall consistency (Region B), notable deviations appear in Region A, likely due to elevated FeO content and its enhanced influence on both ionic and electronic conduction mechanisms.

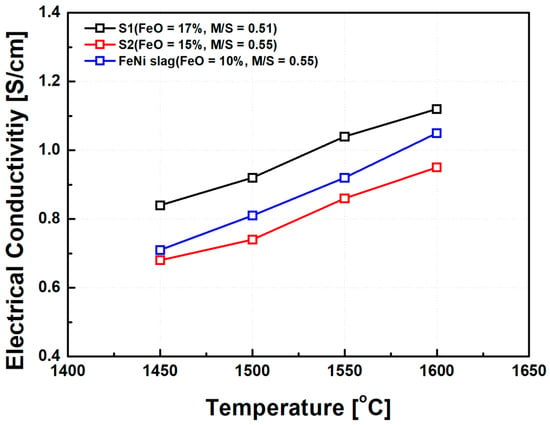

To validate the applicability of the synthetic MgO–SiO2–FeO slag system, electrical conductivity measurements were also conducted on industrial ferronickel slags with similar chemical compositions. The composition of the industrial slags used in this comparison is presented in Table 2, while synthetic slags S1 and S3 from Table 1 were selected for reference. The measurement temperature range was set between 1450 °C and 1650 °C to reflect typical operating conditions in commercial electric furnaces. The comparison results are shown in Figure 13. Both the industrial and synthetic slags exhibited similar trends in electrical conductivity as a function of FeO content and basicity (MgO/SiO2 ratio). Specifically, increasing FeO concentration and higher basicity led to enhanced electrical conductivity across all samples. Notably, even at comparable FeO contents and MgO/SiO2 ratios, the industrial ferronickel slags consistently demonstrated slightly higher electrical conductivity than the synthetic counterparts. This discrepancy is attributed to the presence of minor components in the industrial slag, such as NiO, CaO, and metallic particles, which are not present in the synthetic compositions. These components likely contributed to further depolymerization of the silicate network structure, as discussed in previous sections, thereby increasing the number of mobile ions and facilitating charge.

Figure 13.

Comparison of electrical conductivity between synthetic slag and ferronickel (FeNi) smelting slag. Note: The graph highlights the effects of FeO content and basicity on conductivity, with FeNi slag displaying slightly higher conductivity attributed to the presence of NiO, CaO, and metallic particles.

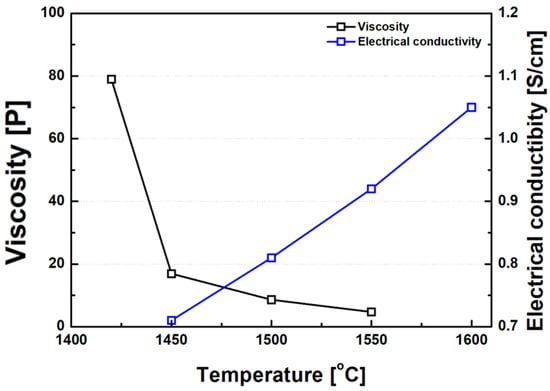

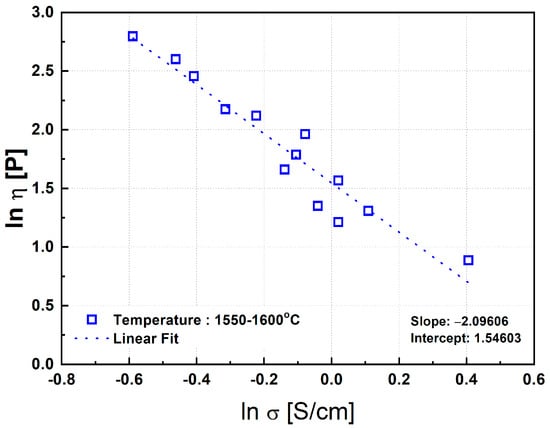

Consistent with earlier studies investigating the inverse relationship between slag viscosity and electrical conductivity in non-charge-hopping-dominated systems [18,43], the ferronickel slags examined in this study also exhibited a clear inverse correlation between viscosity and electrical conductivity, as shown in Figure 14. Previous studies have attempted to establish empirical relationships between slag viscosity and electrical conductivity. One such relationship for binary silicate slags (MO–SiO2 systems) is presented in Equation (5), as proposed by Zhang et al. [43].

ln η = −1.10 σ + 0.15,

Figure 14.

Correlation between electrical conductivity and viscosity of FeNi slag. Note: The inverse relationship suggests that lower viscosity promotes higher ionic mobility, enhancing conductivity.

In the present study, an analogous approach was taken to examine the correlation between viscosity and electrical conductivity for the ternary MgO–SiO2–FeO synthetic slag system. Figure 15 plots the viscosity and electrical conductivity data measured at temperatures between 1550 °C and 1600 °C. A strong correlation was obtained, with a coefficient of determination R2 = 0.91, indicating a reliable inverse relationship under fully molten conditions.

Figure 15.

Correlation between electrical conductivity and viscosity of synthetic slag. Note: The trend indicates a strong inverse relationship, particularly in fully molten states, reinforcing the viscosity’s dominant role in determining conductivity.

From the regression analysis of the data shown in Figure 15, the following relationship was derived:

ln η = −2.1 ln σ + 1.5,

However, below 1500 °C, the correlation between viscosity and conductivity significantly deteriorated. This is likely due to the increased formation of solid phases at lower temperatures. When Equation (6) was applied to data at 1500 °C and 1450 °C, the resulting R2 values were only 0.33 and 0.069, respectively, indicating very weak correlations. The reduced accuracy of the regression at lower temperatures can be attributed to both the increased volume fraction of precipitated solids and the compositional deviation in the remaining liquid phase from the original slag composition. These changes can significantly alter the electrical conductivity, leading to a breakdown in the correlation described by Equation (6). Therefore, Equation (6) is considered to be valid primarily under conditions where the slag is fully molten, and the influence of solid phase precipitation is minimal.

It is also important to elucidate the effect of increased FeO content on slag conductivity. Several studies have reported that when the FeO content exceeds approximately 20 wt.%, the electrical conductivity increases much more rapidly with further FeO addition. This behavior can be explained by the DACT model, in which the shortened distance between Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions enhances charge hopping, leading to highly active electron transfer [28,44]. Under these conditions, ionic conduction remains the dominant mechanism governing the overall electrical conductivity. Although such high FeO levels lie beyond the compositional range investigated in the present study, in practical ESF operations, a significant rise in FeO content (e.g., >25 wt.%) can markedly increase slag conductivity. This results in a sharp reduction in resistivity, which consequently decreases Joule heating and lowers the slag temperature. While reduced resistive losses can improve overall energy efficiency, they may also cause difficulties in slag tapping and stable furnace operation. Furthermore, maintaining constant furnace power under such high-conductivity conditions would require a substantial increase in current input, potentially exceeding the design limits of the power supply system. Therefore, FeO variations and the corresponding changes in slag conductivity should be carefully considered during the furnace design stage.

4. Conclusions

In this study, the effects of slag composition and temperature on the viscosity and electrical conductivity of ferronickel slags were systematically investigated. The key findings are summarized as follows:

- A consistent increase in electrical conductivity was observed with rising slag temperature, attributed to the decrease in viscosity and enhanced ionic mobility. This indicates that physical transformations in the molten slag at elevated temperatures significantly influence its electrical properties.

- In silicate-based slags, a decrease in basicity (MgO/SiO2 ratio) led to increased viscosity and decreased conductivity. This behavior is explained by the densification of the silicate network, which restricts the mobility of charge-carrying cations.

- Increasing FeO content resulted in lower viscosity and higher electrical conductivity. This trend is primarily due to the increased concentration of mobile Fe2+ ions. At FeO content of approximately 17 wt.%, a minor contribution from Fe2+/Fe3+ charge hopping is also likely to influence conductivity.

- When comparing synthetic slags with industrial ferronickel slags of similar composition, the industrial slags exhibited slightly higher conductivity. This enhancement is attributed to the presence of additional oxides such as NiO and metallic species, which facilitate further depolymerization of the silicate network and enhance ionic transport.

- A clear inverse correlation was identified between slag viscosity and electrical conductivity in actual ferronickel furnace slags. Under the tested conditions, viscosity emerged as a dominant factor governing the electrical conductivity of the slag system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-H.C.; methodology, K.-D.L. and W.-G.S.; software, K.-D.L. and A.G.; validation, W.-G.S. and A.G.; formal analysis, K.-D.L.; investigation, K.-D.L. and W.-G.S.; resources, S.-H.C.; data curation, K.-D.L. and W.-G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, K.-D.L.; writing—review and editing, S.-H.C. and A.G.; visualization, K.-D.L. and A.G.; supervision, S.-H.C.; project administration, S.-H.C.; funding acquisition, S.-H.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was supported by Sunchon National University Glocal University project fund in 2025.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- INSG (International Nickel Study Group). World Nickel Factbook 2024, Lisbon, Portugal. Available online: https://insg.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/publist_The-World-Nickel-Factbook-2024.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Lennon, J. Indonesia’s Role in Meeting Booming Nickel Demand: Opportunities and Threats. In Proceedings of the 2023 Indonesia Nickel and Cobalt Industry Chain Conference, Shanghai Metals Market, Jakarta, Indonesia, 30–31 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Meshram, P.; Abhilash; Pandey, B.D. Advanced Review on Extraction of Nickel from Primary and Secondary Sources. Miner. Proc. Extr. Metal. Rev. 2018, 40, 157–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Yuan, S.; Wen, J.; He, J. Review on comprehensive utilization of nickel laterite ore. Miner. Eng. 2024, 218, 109044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, R.; Pickles, C.A.; Peacey, J. Ferronickel particle formation during the carbothermic reduction of a limonitic laterite ore. Miner. Eng. 2017, 100, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickles, C.A.; Forster, J.; Elliott, R. Thermodynamic analysis of the carbothermic reduction roasting of a nickeliferous limonitic laterite ore. Miner. Eng. 2014, 65, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskinkilic, E. Nickel laterite smelting processes and some examples of recent possible modifications to the conventional route. Metals 2019, 9, 974–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Li, B.; Cheung, S.C.; Wu, W. Material and energy flows in rotary kiln-electric furnace smelting of ferronickel alloy with energy saving. App. Ther. Eng. 2016, 109, 542–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, W.; Li, B.; Liu, P.; Qi, F. Exergy assessment of a rotary kiln-electric furnace smelting of ferronickel alloy. Energy 2017, 138, 942–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, C.; Koehler, T.; Voermann, N.; Wasmund, B. High power shielded arc FeNi furnace operation challenges and solutions. In Proceedings of the 12th International Ferroalloys Congress (INFACON XII), Helsinki, Finland, 6–9 June 2010; Available online: https://www.pyrometallurgy.co.za/InfaconXII/681-Walker.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Voermann, N.; Gerritsen, T.; Candy, I.; Stober, F.; Matyas, A. Developments in furnace technology for ferronickel production. In Proceedings of the 10th International Ferroalloys Congress (INFACON X), Cape Town, South Africa, 1–4 February 2004; Available online: https://www.pyrometallurgy.co.za/InfaconX/069.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Kotze, I.J. Pilot plant production of ferronickel from nickel oxide ores and dusts in a DC arc furnace. Miner. Eng. 2019, 15, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herland, E.V.; Sparta, M.; Halvorsen, S.A. Skin and proximity effects in electrodes and furnace shells. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2019, 50, 2884–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfahunegn, Y.A.; Magnusson, T.; Tangstad, M.; Saevarsdottir, G. Dynamic Current Distribution in the Electrodes of Submerged Arc Furnace Using Scalar and Vector Potentials. In Proceedings of the Computational Science—ICCS 2018, Wuxi, China, 11–13 June 2018; pp. 518–527. Available online: https://www.iccs-meeting.org/archive/iccs2018/papers/108610507.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Dhainaut, M. Simulation of the electric field in a submerged arc furnace. In Proceedings of the 10th International Ferroalloys Congress (INFACON X), Cape Town, South Africa, 1–4 February 2004; Available online: https://www.pyrometallurgy.co.za/InfaconX/079.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Jiao, Q.; Themelis, N. Correlation of geometric factor for slag resistance electric furnaces. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 1991, 22, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.-M.; Shen, Y.; Xie, W.; Wang, J. Viscosity and structure evolution of the SiO2-MgO-FeO-CaO-Al2O3 slag in ferronickel smelting process from laterite. J. Min. Metall. Sect. B Metall. 2017, 53, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.-H.; Yan, B.-J.; Chou, K.-C.; Li, F.-S. Relation between viscosity and electrical conductivity of silicate melts. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2011, 42, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, I.M.; Dougherty, T.J. A Mechanism for Non-Newtonian Flow in Suspensions of Rigid Spheres. Trans. Soc. Rheo. 1959, 3, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, K.; Furuse, H. Extension of Einstein’s viscosity equation to that for concentrated dispersions of solutes and particles. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2006, 102, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, K.C. The estimation of slag properties. South. Afr. Pyromet. 2011, 7, 35–42. Available online: https://www.saimm.co.za/Conferences/Pyro2011/KenMills.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Mills, K.C.; Yuan, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, G. Estimating viscosities, electrical & thermal conductivities of slags. High Temp. High Pres. 2013, 42, 237–256. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, B.; Jiao, F.; Li, H.; Hu, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, T.; Mao, L. Relation between the viscosity and electrical conductivity of molten slag for coal gasification and their dependence on SiO2 content. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2024, 207, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-F.; Lv, X.-M.; Pang, Z.-D.; Lv, X.-W. Effect of basicity and Al2O3 on viscosity of ferronickel smelting slag. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2020, 27, 1400–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibodeau, E.; Jung, I.-H. A Structural Electrical Conductivity Model for Oxide Melts. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2015, 47, 355–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.-H.; Chou, K.-C. Simple method for estimating the electrical conductivity of oxide melts with optical basicity. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2010, 41, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barati, M.; Coley, K.S. Electrical and electronic conductivity of CaO-SiO2-FeOx slags at various oxygen potentials: Part I. Experimental results. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2006, 37, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barati, M.; Coley, K.S. Electrical and electronic conductivity of CaO-SiO2-FeOx slags at various oxygen potentials: Part II. Mechanism and a model of electronic conduction. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2006, 37, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muire, H.; Zaaiman, S.; Zietsman, J.H. Slag physical property models and data: A review of viscosity and electrical conductivity measurements and models. In Proceedings of the Southern African Pyrometallurgy 2024 International Conference, Johannesburg, South Africa, 13–14 March 2024; Available online: https://www.saimm.co.za/Conferences/files/pyrometallurgy-2024/15_P658-Muire.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Jak, E.; Hayes, P.C. Slag phase equilibria and viscosities in ferronickel smelting slag. In Proceedings of the 12th International Ferroalloys Congress (INFACON XII), Helsinki, Finland, 6–9 June 2010; Available online: https://www.pyrometallurgy.co.za/InfaconXII/631-Jak.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Kim, W.Y.; Hudon, P.; Jung, I.H. Modeling the viscosity of silicate melts containing Fe oxide: Fe saturation condition. Calphad 2021, 72, 102242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.L.; Morales Pereira, J.A.; Bielefeldt, W.V.; Vilela, A.C.F. Thermodynamic evaluation of viscosity behavior for CaO–SiO2–Al2O3–MgO slag systems examined at the temperatures range from 1500 to 1700 °C. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielefeldt, W. Slag Viscosity Calculation of the CaO-SiO2-Al2O3 System with FactSage (v6.4), GTT Workshop, Germany. 2015. Available online: https://gtt-technologies.de/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Talk_W.Bielefeldt.2015.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Kovtun, O.; Korobeinikov, I.; C, S.; Shukla, A.K.; Volkova, O. Viscosity of BOF Slag. Metals 2020, 10, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.L.; da Rocha, V.C.; Bielefeldt, W.V.; Vilela, A.C.F. Iso-viscosity curves for CaO-SiO2-MgO steelmaking slags at high temperature. In Proceedings of the 74th Congresso Annual da ABM—Internacional, Part of the ABM Week, São Paulo, Brazil, 1–3 October 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, G.H.; Sohn, I. Effect of TiO2 on the viscosity and slag structure in blast furnace type slags. Steel Res. Int. 2012, 83, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M. Electrical Conductivity Measurements of Slag at Elevated Temperature—Properties of Slag at Elevated Temperature. Trans. Iron Steel Inst. Jap. 1969, 6, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xueming, L.; Jie, Q.; Meng, L.; Mei, L.; Xuewei, L. Viscosity of SiO2-MgO-Al2O3-FeO slag for nickel laterite smelting process. In Proceedings of the 14th International Ferroalloys Congress (INFACON XIV), Kyiv, Ukraine, 31 May–4 June 2015; Available online: https://pyro.co.za/InfaconXIV/561-Xueming.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Kashio, S.; Iguchi, Y.; Goto, T.; Nishina, Y.; Fuwa, T. Raman spectroscopic study on the structure of silicate slag. Trans. Iron Steel Inst. Jap. 1980, 20, 251–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, K.C. The Influence of Structure on the Physico-chemical Properties of slags. ISIJ Int. 1993, 33, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, R. The viscosity of suspensions of rigid spheres. Brit. J. App. Phy. 1952, 3, 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.-H.; Chou, K.-C.; Li, F.-S. A new model for evaluating the electrical conductivity of nonferrous slag. Int. J. Min. Metall. Mat. 2009, 16, 500–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.H.; Chou, K.C. Correlation between viscosity and electrical conductivity of aluminosilicate melts. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2012, 43, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahat, R.; Eissa, M.; Megahed, G.; Fathy, A.; Abdel-Gawad, S.; El-Deab, M.S. Effect of EAF slag temperature and composition on its electrical conductivity. ISIJ Int. 2019, 59, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).