The Effects of Perceived Neighborhood Diversity on Preferences for Redistribution: A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Diversity Paradox

2. Data and Methods

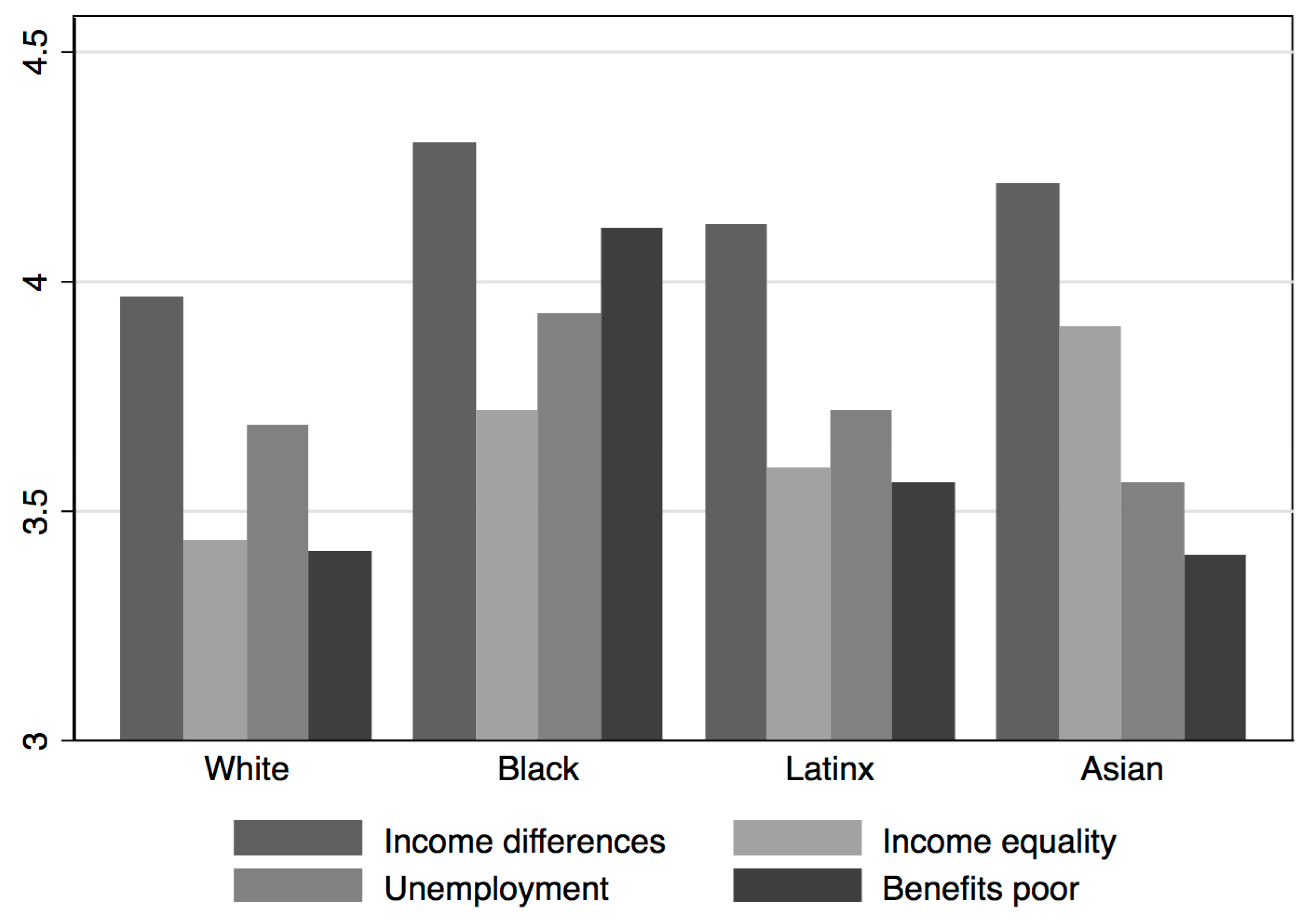

2.1. Outcome Measures

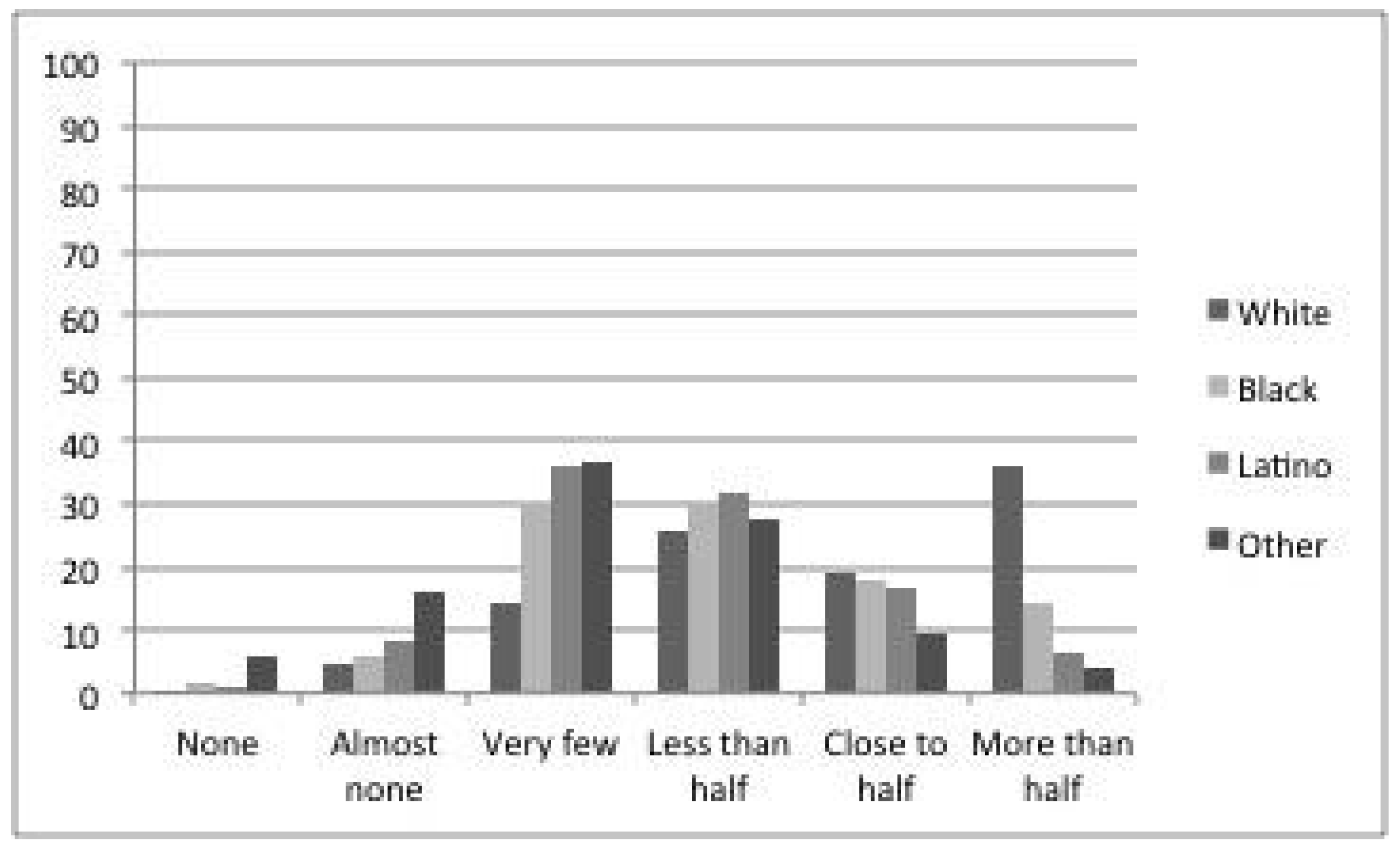

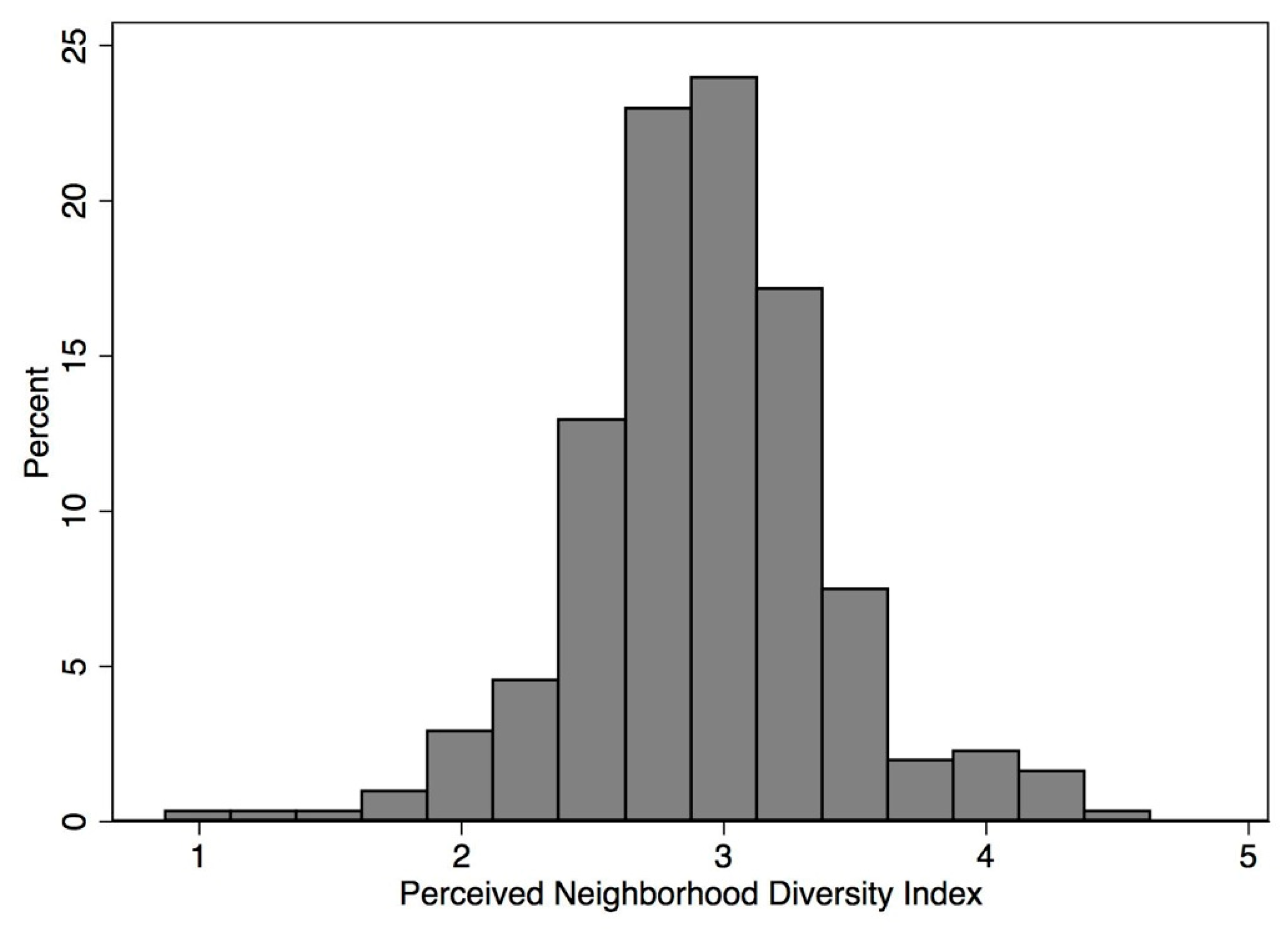

2.2. Key Explanatory Measures

2.3. Analytical Strategy

3. Results

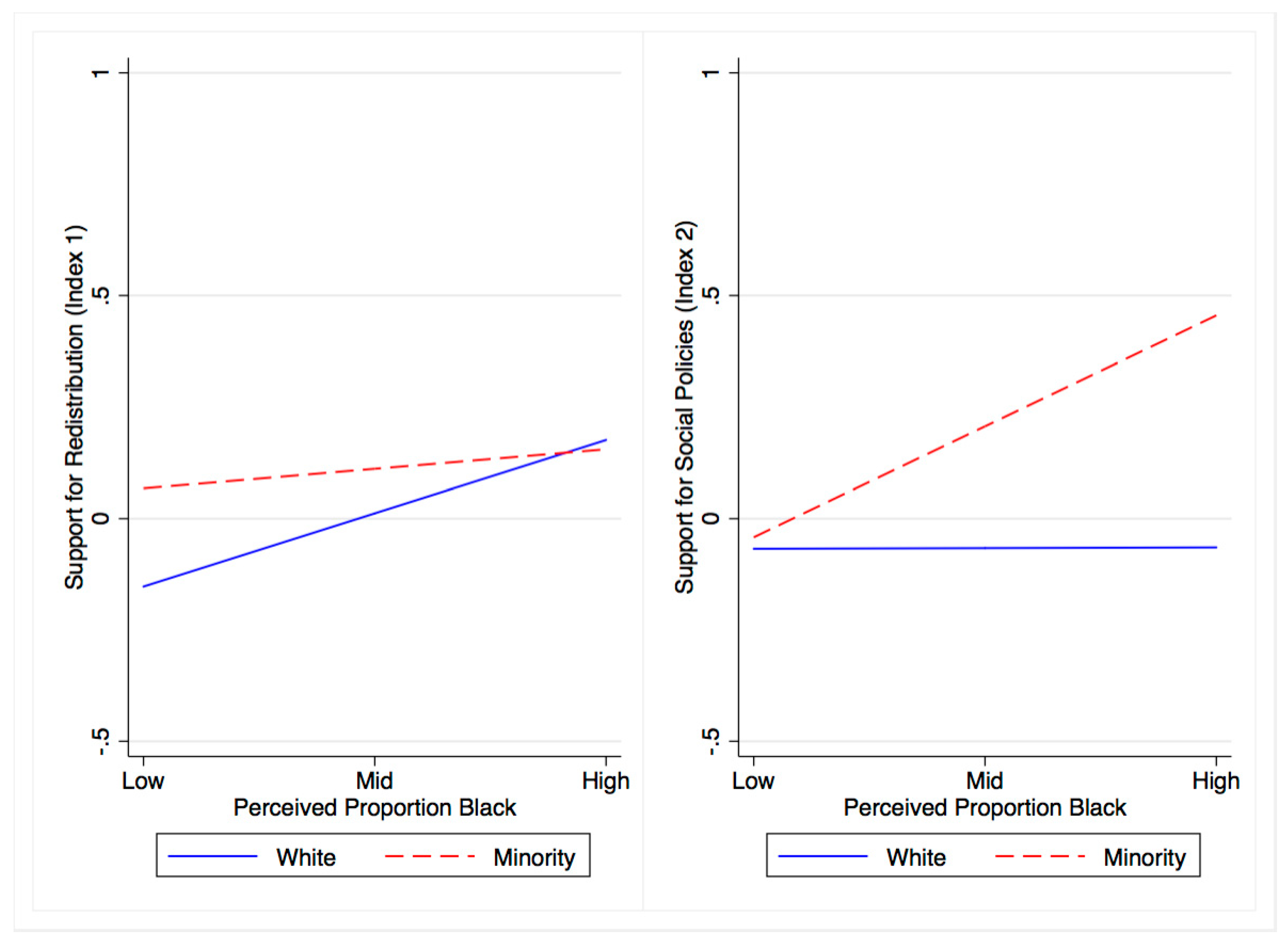

3.1. The Effect of Neighborhood Diversity

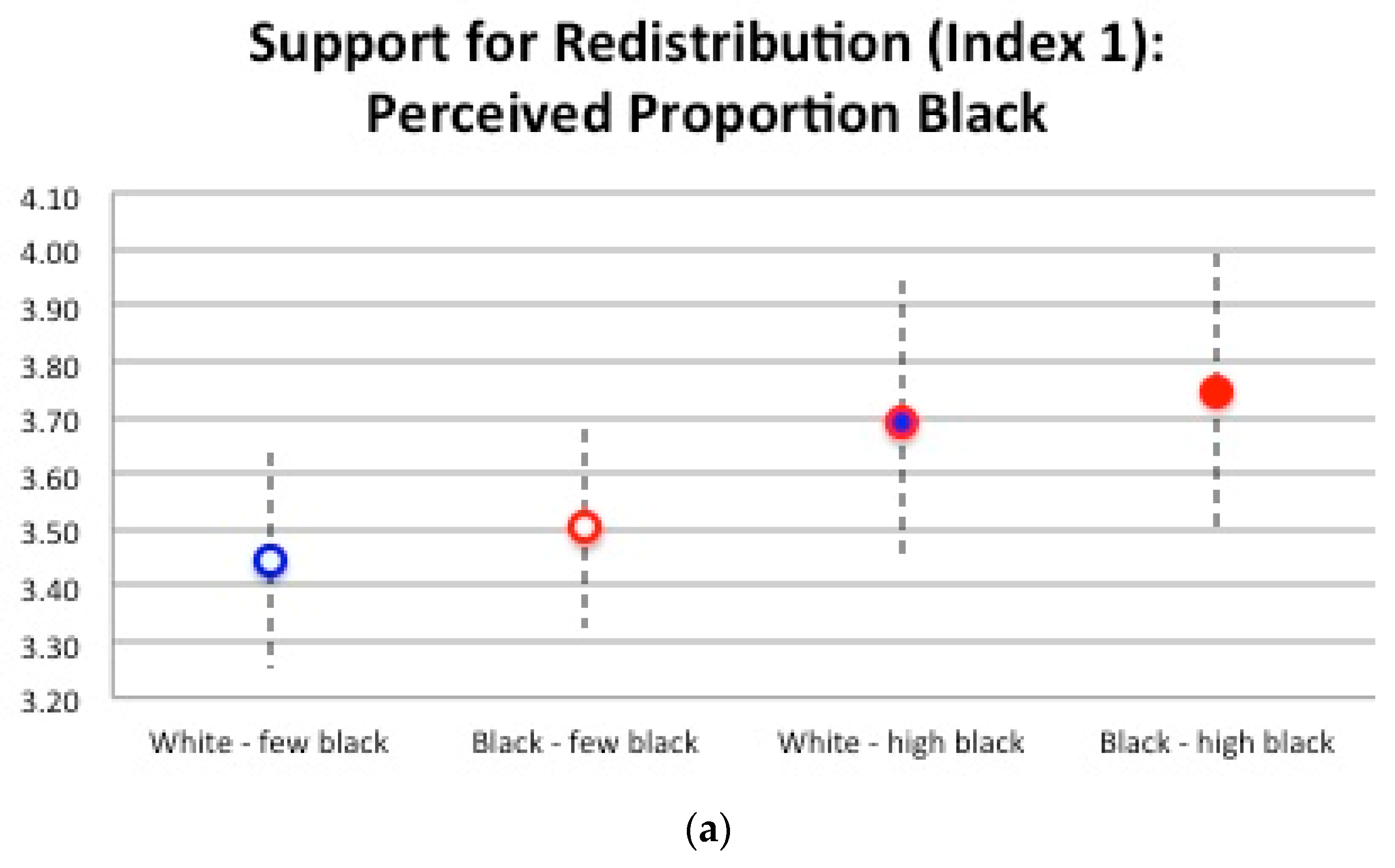

3.2. The Effects of Neighborhood Homogeneity and In-Group/Out-Group Status

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| White Respondents | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

| Index 1: Redist | Index 2: Soc Pol | Index 1: Redist | Index 2: Soc Pol | Index 1: Redist | Index 2: Soc Pol | |

| Perceived proportion: White | −0.02 | 0.11 | ||||

| (0.11) | (0.11) | |||||

| Perceived proportion: Black | 0.16 | 0.00 | ||||

| (0.12) | (0.12) | |||||

| Perceived proportion: Latinx | 0.18 | −0.04 | ||||

| (0.13) | (0.13) | |||||

| Constant | 0.01 | −0.32 | −0.32 | −0.07 | −0.32 | −0.01 |

| (0.27) | (0.27) | (0.21) | (0.21) | (0.21) | (0.21) | |

| Observations | 199 | 199 | 199 | 199 | 199 | 199 |

| R squared | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

| Minority Respondents | Index 1: Redist | Index 2: Soc Pol | Index 1: Redist | Index 2: Soc Pol | Index 1: Redist | Index 2: Soc Pol |

| Perceived proportion: White | −0.07 | −0.18 | ||||

| (0.13) | (0.13) | |||||

| Perceived proportion: Black | 0.04 | 0.25 * | ||||

| (0.13) | (0.12) | |||||

| Perceived proportion: Latinx | 0.14 | 0.10 | ||||

| (0.15) | (0.15) | |||||

| Constant | 0.24 | 0.53 * | 0.02 | −0.29 | −0.13 | 0.03 |

| (0.26) | (0.25) | (0.27) | (0.26) | (0.27) | (0.27) | |

| Observations | 94 | 94 | 94 | 94 | 94 | 94 |

| R-squared | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Respondent Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Proportion Neighbors’ Races/Ethnicities | White | Minority | Own Group White | ||||||

| White | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n |

| None—less than half | 3.55 | 0.93 | 73 | 3.28 | 0.76 | 58 | 3.55 | 0.93 | 73 |

| About half—more than half | 3.54 | 1.12 | 126 | 3.07 | 0.85 | 36 | 3.54 | 1.12 | 126 |

| ANOVA | F(1,197) = 0.00, p = 0.948 | F(1,92) = 0.65, p = 0.422 | F(1,197) = 0.00, p = 0.948 | ||||||

| White | Minority | Black | |||||||

| Black | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n |

| None—less than half | 3.44 | 1.07 | 151 | 3.72 | 1.09 | 48 | 3.80 | 0.93 | 10 |

| About half—more than half | 3.87 | 0.93 | 48 | 3.69 | 0.98 | 46 | 3.86 | 1.05 | 33 |

| ANOVA | F(1,197) = 6.08, p = 0.015 | F(1,92) = 0.02, p = 0.875 | F(1,41) = 0.03, p = 0.875 | ||||||

| White | Minority | Latinx | |||||||

| Latinx | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n |

| None—less than half | 3.52 | 1.09 | 162 | 3.61 | 1.07 | 64 | 3.41 | 1.54 | 18 |

| About half—more than half | 3.67 | 0.89 | 37 | 3.90 | 0.93 | 30 | 3.90 | 0.63 | 13 |

| ANOVA | F(1,197) = 0.60, p = 0.441 | F(1,92) = 1.57, p = 0.213 | F(1,29) = 1.17, p = 0.288 | ||||||

| Respondent Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Proportion Neighbors’ Races/Ethnicities | White | Minority | Own Group White | ||||||

| White | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n |

| None—less than half | 2.92 | 0.81 | 73 | 3.28 | 0.76 | 58 | 2.92 | 0.81 | 73 |

| About half—more than half | 3.01 | 0.84 | 126 | 3.07 | 0.85 | 36 | 3.01 | 0.84 | 126 |

| ANOVA | F(1,197) = 0.48, p = 0.487 | F(1,92) = 1.56, p = 0.216 | F(1,197) = 0.48, p = 0.487 | ||||||

| White | Minority | Black | |||||||

| Black | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n |

| None—less than half | 3.01 | 0.80 | 151 | 3.09 | 0.86 | 3.09 | 3.15 | 1.04 | 10 |

| About half—more than half | 2.88 | 0.92 | 48 | 3.32 | 0.72 | 3.32 | 3.40 | 0.72 | 33 |

| ANOVA | F(1,197) = 0.98, p = 0.323 | F(1,92) = 1.91, p = 0.170 | F(1,41) = 0.76, p = 0.389 | ||||||

| White | Minority | Latinx | |||||||

| Latinx | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n |

| None—less than half | 2.99 | 0.83 | 162 | 3.14 | 0.84 | 64 | 3.17 | 0.96 | 18 |

| About half—more than half | 2.93 | 0.85 | 37 | 3.33 | 0.70 | 30 | 3.29 | 0.53 | 13 |

| ANOVA | F(1,197) = 0.14, p = 0.709 | F(1,92) = 1.24, p = 0.268 | F(1,29) = 0.17, p = 0.683 | ||||||

References

- International Migration Report 2017: Highlights; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2017.

- Chang, J.-H.; Hsu, C.-C.; Shih, N.-H.; Chen, H.-C. Multicultural Families and Creative Children. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2014, 45, 1288–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gocłowska, M.A.; Damian, R.I.; Mor, S. The Diversifying Experience Model: Taking a Broader Conceptual View of the Multiculturalism–Creativity Link. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2018, 49, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, P. Exodus: How Migration is Changing Our World; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Glazer, N. The American welfare state: Exceptional no longer? In Challenges to the Welfare State: Internal and External Dynamics for Change; Cavanna, H., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 1998; pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Goodhart, D. Too Diverse? Prospect 2004, 95, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, N. Diversity versus solidarity: A new progressive dilemma. Renew. J. Labour Polit. 2004, 12, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer, M. Ethnic Diversity and Social Cohesion: Immigration, Ethnic Fractionalization and Potentials for Civic Action; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-317-14095-5. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Meer, T.; Tolsma, J. Ethnic Diversity and Its Effects on Social Cohesion. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2014, 40, 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the Twenty-first Century. Scand. Polit. Stud. 2007, 30, 137–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finseraas, H.; Kotsadam, A. Does personal contact with ethnic minorities affect anti-immigrant sentiments? Evidence from a field experiment. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 2017, 56, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A.; Vickstrom, E. Diversity, Social Capital, and Cohesion. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2011, 37, 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stichnoth, H.; Van der Straeten, K. Ethnic Diversity, Public Spending, and Individual Support for the Welfare State: A Review of the Empirical Literature. J. Econ. Surv. 2013, 27, 364–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, M. Ethnic Diversity, Public Goods Provision and Social Cohesion: Lessons from an Inconclusive Literature. WZB Discussion Paper. 2013. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/86148/1/770694160.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- Alesina, A.; Baqir, R.; Easterly, W. Public Goods and Ethnic Divisions. Q. J. Econ. 1999, 114, 1243–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A.; Glaeser, E.L. Fighting Poverty in the US and Europe: A World of Difference; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Banting, K.; Kymlicka, W. (Eds.) Multiculturalism and the Welfare State; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Desmet, K.; Ortuño-Ortin, I.; Weber, S. Linguistic Diversity and Redistribution. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2009, 7, 1291–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, F.K. (Ed.) Welfare, Ethnicity and Altruism: New Findings and Evolutionary Theory; Frank Cass: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, D.C.; Murrell, P. Interest groups and the size of government. Public Choice 1986, 48, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eger, M.A. Even in Sweden: The Effect of Immigration on Support for Welfare State Spending. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2010, 26, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stichnoth, H. Does immigration weaken natives’ support for the unemployed? Evidence from Germany. Public Choice 2011, 151, 631–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, J.D. The Transition from Capitalism to Socialism; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton, A.S.; Dixon, J.C. Racialization, Asymmetry, and the Context of Welfare Attitudes in the American States. J. Polit. Mil. Sociol. 2009, 37, 95–120. [Google Scholar]

- Gilens, M. Preference Gaps and Inequality in Representation. PS Polit. Sci. Polit. 2009, 42, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilens, M. Why Americans Hate Welfare: Race, Media, and the Politics of Antipoverty Policy, 1st ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-226-29365-3. [Google Scholar]

- Blalock, H.M. Toward a Theory of Minority-Group Relations; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, L.G. Ethnic Diversity and Support for Redistributive Social Policies. Soc. Forces 2016, 94, 1439–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eger, M.A.; Breznau, N. Immigration and the welfare state: A cross-regional analysis of European welfare attitudes. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 2017, 58, 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soroka, S.N.; Banting, K.; Johnston, R. Immigration and Redistribution in the Global Era. In Globalization and Social Redistribution; Wallerstein, M., Bowles, S., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, D.; Finnigan, R. Does Immigration Undermine Public Support for Social Policy? Am. Sociol. Rev. 2014, 79, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herda, D. How Many Immigrants? Foreign-Born Population Innumeracy in Europe. Public Opin. Q. 2010, 74, 674–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinesen, P.T.; Sønderskov, K.M. Ethnic Diversity and Social Trust: Evidence from the Micro-Context. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2015, 80, 550–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, R.; Schaeffer, M. Statistical and Perceived Diversity and Their Impacts on Neighborhood Social Cohesion in Germany, France and the Netherlands. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 125, 853–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solnit, R.; Jelly-Schapiro, J. Nonstop Metropolis: A New York City Atlas; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-0-520-28594-1. [Google Scholar]

- Abascal, M.; Baldassarri, D. Love Thy Neighbor? Ethnoracial Diversity and Trust Reexamined. Am. J. Sociol. 2015, 121, 722–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolsma, J.; van der Meer, T.W.G. Trust and contact in diverse neighbourhoods: An interplay of four ethnicity effects. Soc. Sci. Res. 2018, 73, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobo, L. Whites’ opposition to busing: Symbolic racism or realistic group conflict? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 45, 1196–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, R.; Rumbaut, R.G.; Marotz, K. A Distorted Nation: Perceptions of Racial/Ethnic Group Sizes and Attitudes Toward Immigrants and Other Minorities. Soc. Forces 2005, 84, 901–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossett, M.A.; Kiecolt, K.J. The Relative Size of Minority Populations and White Racial Attitudes. Soc. Sci. Q. 1989, 70, 820–835. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, T.F. Demographic Correlates of Border-State Desegregation. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1957, 22, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quillian, L. Prejudice as a Response to Perceived Group Threat: Population Composition and Anti-Immigrant and Racial Prejudice in Europe. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1995, 60, 586–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlueter, E.; Scheepers, P. The relationship between outgroup size and anti-outgroup attitudes: A theoretical synthesis and empirical test of group threat- and intergroup contact theory. Soc. Sci. Res. 2010, 39, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, M.A.; Richeson, J.A. More Diverse Yet Less Tolerant? How the Increasingly Diverse Racial Landscape Affects White Americans’ Racial Attitudes. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 40, 750–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, M.A.; Richeson, J.A. On the Precipice of a “Majority-Minority” America: Perceived Status Threat From the Racial Demographic Shift Affects White Americans’ Political Ideology. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danbold, F.; Huo, Y.J. No Longer “All-American”? Whites’ Defensive Reactions to Their Numerical Decline. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2015, 6, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, B.; Blodorn, A.; Major Blascovich, G. The threat of increasing diversity: Why many White Americans support Trump in the 2016 presidential election. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2016, 21, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outten, H.R.; Schmitt, M.T.; Miller, D.A.; Garcia, A.L. Feeling Threatened About the Future: Whites’ Emotional Reactions to Anticipated Ethnic Demographic Changes. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 38, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wetts, R.; Willer, R. Privilege on the Precipice: Perceived Racial Status Threats Lead White Americans to Oppose Welfare Programs. Soc. Forces 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G.W. The Nature of Prejudice; Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner, S.L.; Dovidio, J. Reducing Intergroup Bias: The Common Group Identity Model; Psychology Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Habyarimana, J.; Humphreys, M.; Posner, D.N.; Weinstein, J.M. Why Does Ethnic Diversity Undermine Public Goods Provision? Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2007, 101, 709–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A.; Glaeser, E.L.; Sacerdote, B. Why doesn’t the U.S. have a European-style welfare system? Brook. Pap. Econ. Act. 2001, 2, 187–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, J.T. Fractionalization and the size of government. J. Public Econ. 2007, 91, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, C.G.; Shin, H.; Leal, D.L. The Contact Hypothesis and Attitudes Toward Latinos in the United States. Soc. Sci. Q. 2011, 92, 938–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C. The Changing Color of Welfare? How Whites’ Attitudes toward Latinos Influence Support for Welfare. Am. J. Sociol. 2004, 110, 580–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, G.E.; Yinger, J.M. Techniques for Reducing Prejudice: Changing the Situation. In Psychology and Race; Watson, P., Ed.; AldineTransaction, A Division of Transaction Publishers, Rutgers—The State University: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, G.; Hodson, R.; Sekulić, D. Ethnic Enclaves and Intolerance: The Case of Yugoslavia. Soc. Forces 1999, 78, 669–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berinsky, A.J.; Huber, G.A.; Lenz, G.S. Evaluating Online Labor Markets for Experimental Research: Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk. Polit. Anal. 2012, 20, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, S.; Jewell, R.M.; Waggoner, P.D. Are samples drawn from Mechanical Turk valid for research on political ideology? Res. Polit. 2015, 2, 2053168015622072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibodeau, P.H.; Flusberg, S.J. Metaphorical Accounting: How Framing the Federal Budget Like a Household’s Affects Voting Intentions. Cogn. Sci. 2017, 41, 1168–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISSP Research Group. International Social Survey Programme (ISSP): Social Inequality IV, 2009, ZA5400 (v4.0.0); GESIS: Cologne, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ISSP Research Group. International Social Survey Programme: Role of Government V-ISSP 2016; ZA6900 Data file Version 1.0.0.; GESIS Data Archive: Cologne, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alesina, A.; Devleeschauwer, A.; Easterly, W.; Kurlat, S.; Wacziarg, R. Fractionalization. J. Econ. Growth 2003, 8, 155–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, J.D. Ethnic and Cultural Diversity by Country. J. Econ. Growth 2003, 8, 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banting, K.; Johnston, R.; Kymlicka, W.; Soroka, S.N. Do multiculturalism policies erode the welfare state? An empirical analysis. In Multiculturalism and The Welfare State; Banting, K., Kymlicka, W., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 49–91. [Google Scholar]

- James, W. The perception of reality. In The Principles of Psychology, Vol II; Henry Holt and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1890; pp. 283–324. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, C.A. Miscounting Race: Explaining Whites’ Misperceptions of Racial Group Size. Sociol. Perspect. 2003, 46, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telles, E.E. Project on Ethnicity and Race in Latin America (PERLA). 2013. Available online: https://perla.princeton.edu/ (accessed on 10 March 2015).

- Huff, C.; Tingley, D. “Who are these people?” Evaluating the demographic characteristics and political preferences of MTurk survey respondents. Res. Polit. 2015, 2, 2053168015604648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgis, P.; Brunton-Smith, I.; Kuha, J.; Jackson, J. Ethnic diversity, segregation and the social cohesion of neighbourhoods in London. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2014, 37, 1286–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crepaz, M. “If you are my brother, I may give you a dime!” Public opinion on multiculturalism, trust, and the welfare state. In Multiculturalism and the Welfare State; Banting, K., Kymlicka, W., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 92–120. [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell, J.T. The Effects of Racial Segregation on Trust and Volunteering in US Cities. Urban Stud. 2012, 41, 2109–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeskens, T.; Van Oorschot, W. Disentangling the “New Liberal Dilemma”: On the relation between general welfare redistribution preferences and welfare chauvinism. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 2012, 53, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, D.; Sadrieh, A.; Verbon, H.A.A. Cross-racial envy and underinvestment in South African partnerships. Camb. J. Econ. 2008, 32, 703–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gans, H.J. Race as Class. Contexts 2005, 4, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, R.; Hendren, N.; Jones, M.R.; Porter, S.R. Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective; National Bureau of Economic Research, 2018. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w24441 (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- Rosenberg, Z. New York’s Most and Least Affordable Neighborhoods. Available online: https://ny.curbed.com/2017/8/4/16099252/new-york-neighborhood-affordability (accessed on 3 August 2018).

- U.S. Census Bureau Population Division-New York City Department of City Planning. U.S. Census 2010; U.S. Census Bureau New York Regional Office: New York, NY, USA, 2011.

- Kasinitz, P.; Mollenkopf, J.; Waters, M.C. Becoming American/Becoming New Yorkers: Immigrant Incorporation in a Majority Minority City. Int. Migr. Rev. 2002, 36, 1020–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewstone, M. Living Apart, Living Together? The Role of Intergroup Contact in Social Integration. In Proceedings of the British Academy; Johnston, R., Ed.; 2006 Joint British Academy/British Psychological Society Lecture; British Academy: London, UK, 2009; Volume 162, ISBN 978-0-19-173406-9. [Google Scholar]

- Tropp, L.; Okamoto, D.G.; Marrow, H.; Jones-Correa, M. Intergroup Contact and Social Inclusion: Relations among Immigrant and U.S.-Born Communities in the United States. Presented at the Immigration Seminar Series, The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, NY, USA, 10 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stolle, D.; Soroka, S.; Johnston, R. When Does Diversity Erode Trust? Neighborhood Diversity, Interpersonal Trust and the Mediating Effect of Social Interactions. Polit. Stud. 2008, 56, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herda, D. Innumeracy in Turkey: Misperceptions of an Emerging Immigrant Population. Insight Turk. 2015, 17, 187–205. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Location limited to “US-NY (state)” using mTurk parameters; NYC residence was subsequently confirmed via screening questions (borough name, zip code, and neighborhood name). |

| 2 | Human Intelligence Task (HIT) approval rate greater than or equal to 95%; number of HITs completed greater than or equal to 1000. |

| 3 | MTurk samples tend to be disproportionately male, younger, more politically liberal, less religious, and less racially diverse than the U.S. population [59]. |

| 4 | Source: NYC Planning Population FactFinder using 2012–2016 American Community Survey data (note: these data include those under age 18, who are excluded from our study). |

| 5 | Source: 2015 American Community Survey data (note: these data include those under age 18, who are excluded from our study). |

| 6 | Orthogonally rotated factor loadings indicated that the questions from these two surveys should be treated as separate constructs. |

| 7 | Twenty-four respondents (7.5%) selected more than one ethnic or racial identity. |

| 8 |

| Variable | Sample Median or % | NYC Median or %4 | U.S. Median or %5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 37.5% | 52.3% | 50.8% |

| Age | 29.1 | 35.9 | 37.8 |

| Race/Ethnicity 1 | |||

| White (not Hispanic/Latinx) | 62.2% | 32.3% | 61.5% |

| Black | 13.1% | 22.2% | 13.1% |

| Latinx | 10.3% | 29.1% | 17.6% |

| Asian (East or South) | 12.8% | 13.6% | 5.5% |

| Other | 1.6% | 1.0% | 5.9% |

| Multiracial | 7.5% | 1.8% | 3.1% |

| Citizenship Status | |||

| U.S. citizen (U.S.-born) | 92.5% | 62.8% | 86.5% |

| U.S. citizen (born abroad) | 5.0% | 20.2% | 6.4% |

| Legal permanent resident | 2.2% | ||

| Other | 0.3% | ||

| American Community Survey (ACS) Categories | |||

| Not a U.S. citizen | 2.5% | 17.0% | 7.0% |

| Foreign-born | 7.5% | 37.2% | 13.5% |

| NYC Borough of Residence | |||

| Bronx | 10.9% | 17.0% | |

| Brooklyn | 36.9% | 30.8% | |

| Manhattan | 23.4% | 19.3% | |

| Queens | 23.1% | 27.3% | |

| Staten Island | 5.3% | 5.6% | |

| N | 320 | 8,461,989 | 321,418,821 |

| Variable | Sample Mean (S.D.) | U.S. Mean (S.D.) | Large City Mid-Atlantic U.S. Mean (S.D.) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index 1: Redistribution 1 | ||||

| Income equality | 3.55 (1.23) | 2.66 (1.26) | 3.05 (1.26) | [1, 5] |

| Unemployment | 3.71 (1.10) | 3.10 (1.18) | 3.63 (1.00) | [1, 5] |

| Benefits for the poor | 3.53 (1.21) | 3.53 (1.04) | 3.59 (1.10) | [1, 5] |

| Income difference too large* (*excluded from Index 1) | 4.06 (1.02) | 3.71 (1.12) | 3.97 (0.94) | [1, 5] |

| Number of observations | 320 | 1405 | 91 | |

| Index 2: Social Policies 2 | ||||

| Health | 3.11 (0.99) | 3.33 (0.79) | 3.71 (0.56) | [1, 4] |

| Old age | 3.12 (0.94) | 3.34 (0.74) | 3.54 (0.55) | [1, 4] |

| Student aid | 3.00 (0.95) | 3.32 (0.75) | 3.70 (0.56) | [1, 4] |

| Housing | 2.87 (0.94) | 2.99 (0.81) | 3.38 (0.74) | [1, 4] |

| Jobs* (*excluded from Index 2) | 2.57 (1.01) | 2.20 (0.98) | 2.48 (1.03) | [1, 4] |

| Number of observations | 320 | 1315 | 40 |

| Mean (SE) Index 1: Redistribution | Mean (SE) Index 2: Social Policies | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Minority | Low diversity n = 68 | 3.67 (0.13) | 3.10 (0.10) |

| High diversity n = 31 | 3.76 (0.18) | 3.38 ^ (0.12) | |

| White | Low diversity n = 143 | 3.48 (0.09) | 2.98 (0.07) |

| High diversity n = 63 | 3.70 ^ (0.12) | 2.95 (0.12) |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Steele, L.G.; Perkins, K.M. The Effects of Perceived Neighborhood Diversity on Preferences for Redistribution: A Pilot Study. Societies 2018, 8, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8030082

Steele LG, Perkins KM. The Effects of Perceived Neighborhood Diversity on Preferences for Redistribution: A Pilot Study. Societies. 2018; 8(3):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8030082

Chicago/Turabian StyleSteele, Liza G., and Krystal M. Perkins. 2018. "The Effects of Perceived Neighborhood Diversity on Preferences for Redistribution: A Pilot Study" Societies 8, no. 3: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8030082

APA StyleSteele, L. G., & Perkins, K. M. (2018). The Effects of Perceived Neighborhood Diversity on Preferences for Redistribution: A Pilot Study. Societies, 8(3), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8030082