Abstract

A focal point of this article is symbols (e.g., flags) and how low-income communities use them to construct ownership over spaces that would have otherwise been inaccessible to them. This conception of contested ownership through symbolism helps us to elaborate the main point of this article: how low-income communities continuously battle gentrification through symbols. The following article employs interviews and a theoretical framework on symbols and collective ethnic identity to understand how they operate in the appropriation of space by applying a case study of Humboldt Park, Chicago, and the Puerto Rican community.

Symbolism transforms an object of perception into an idea, the idea into an image, and does it in such a way that the idea always remains infinitely operative and unattainable so that even if it is put into words in all languages, it still remains inexpressible.Goethe, Maxims and Reflections (1999) [1]

1.Introduction

I remember the first time that I visited Paseo Boricua which translates to Puerto Rican Promenade. Paseo Boricua is a Puerto Rican commercial district marked by two large flags made of steel. I was visiting Chicago, IL, from Springfield, MO. I knew there were many Puerto Ricans in Chicago, but I did not have family or friends. I had one uncle in New York and one uncle in New Mexico, but I had none in Chicago. I wanted to visit the Puerto Rican enclave because I wanted to eat traditional food and reconnect with my roots. At the time I did not own a smartphone, and I had trouble finding the address. I only had a general idea where to find these giant flags. They were the first thing that appeared on Google when I typed “Puerto Rican neighborhood Chicago”.

I took my rental car, and I drove around searching for these giant Puerto Rican flags in Humboldt Park. Not knowing the area, I got lost. It was like playing a hot and cold game. I knew that I was getting closer (getting hot) when I would see Puerto Rican flags in people’s homes, cars, murals, and commercial signs. I would also see Puerto Ricans, many of whom also wore the Puerto Rican flag or other symbols like the coquí (a small frog) or a Taíno (indigenous) sun. I would be far (getting cold) when I did not see any more of these symbols.

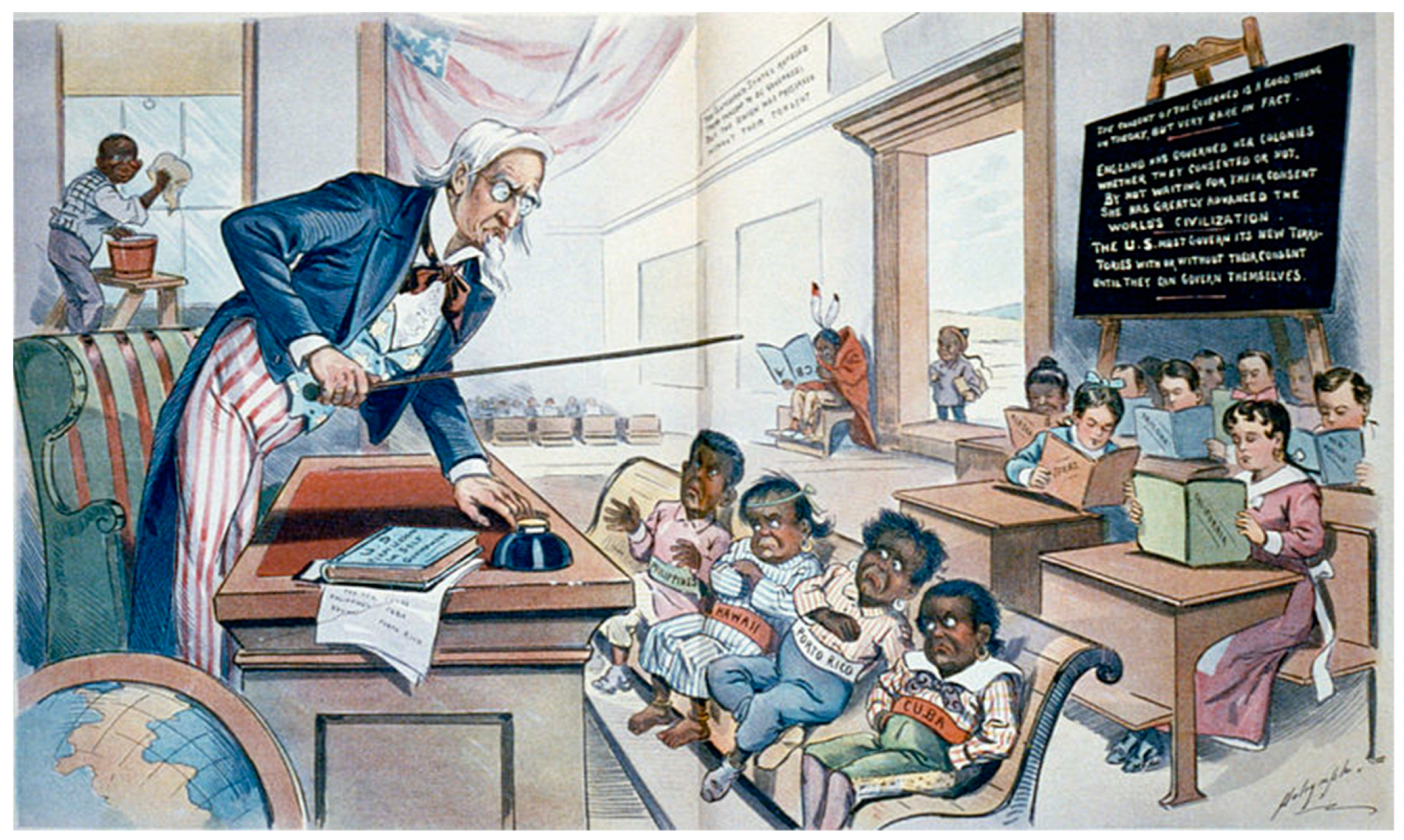

Once I saw the flag near the park, I parked my car and I immediately approached it. Of course, before I had to stop and greet the older gentlemen playing dominos in the park stationed under the flag in California Ave (see Figure 1). The flags made me feel welcomed and at home, even if I did not know the neighborhood at all. The whole space made me feel proud. I wanted to participate, be part of something more significant than myself. Why these flags, and not only the flags but Paseo Boricua as a whole, made me feel this way? That’s when I became aware of semiotics in practice and my own life. I had to find out more about the theory of semiotics to understand this feeling.

Figure 1.

Flag between California Ave. and Division Street at One of the Entrances of Paseo Boricua.

Soon I found there is a long history of thought—from Descartes, Locke, and Hume, through to Kant, Hegel, and Marx, progressing to Nietzsche, Barthes, Lukács, Adorno, Lyotard, Baudrillard, and others—on what constitutes subjects and objects and how they are interpreted and understood by social actors. This article employs these philosophical foundations for understanding mental conceptions and interpretations generally and how those interpretations lead to the creation of symbols more specifically. As such, this article seeks to introduce the reader to the study of symbols to establish the theoretical framework. I will critically engage in what is often taken as commonsensical presuppositions by positivists about symbols, and the exposition of such symbols left unexamined. Specifically, I wish to evaluate the givenness of the symbol and the uncritical assumption of what is expressed by symbols as readily apparent to the naked eye.

By defining symbols, we are indeed reifying a concept that is metaphysical and cannot be explained by science. In other words, symbols are not words. One could not possibly express them in verbal, written or gestural form. Symbols are meant to be communicated and interpreted, not through words or pictures as an end product, but in their entirety—that is, the sound of the word, the observed object, and the conceptions of its meaning—in a particular historical time and place.

In an attempt to define what a symbol is, we could say that symbols are objects, pictures, sounds, actions, things that stand for something else. For our purposes, we will use the word symbol and sign as synonyms. To my understanding, there is no real difference between the two, except that signs are studied in the field of semiotics by philosophers, especially linguists such as Ferdinand de Saussure. For simple definitions, the manner whereby a sign “signifies” is called “semiosis” and the explanation of how semiosis produces its effects is called “semiotics”. Unlike a sign and the study of semiotics, a symbol is a term that is taken to be more mundane, used by all kinds of people, while sign is an academic term used among Saussurians. However, they are synonyms. A sign is a symbol and vice versa.

In this article, we will use the term symbol more often than a sign. A symbol could be the color red used in the traffic light, which indicates danger or stop. A critical element of the symbol is that it is context-specific, the red in the traffic light is something that we can understand because we are part of the driving culture and this would not make much sense in another context. Some symbols are derived from things in nature, such as red being indicative of danger in some species of insects, frogs, and so on, so they are not entirely arbitrary. Just as green and red mean something specific in the context of a traffic light in the U.S., one must ask which symbols among historically marginalized minority groups are used in the context of gentrification?

That first time that I visited Humboldt Park, I did not know that the flags of Paseo Boricua were constructed in 1995 by members of the Puerto Rican Agenda with the explicit purpose of appropriating space in a gentrifying neighborhood. Months after visiting Paseo Boricua, I was invited to start attending the Puerto Rican Agenda meetings as part of a research project. It was in this space that I learned that the number one issue in the community was gentrification and that the flags had a particular role. As one community leader put it,

Gentrification is the number one issue facing the Puerto Rican community. But we are not victims, and we do not preach victimology here. This supports the colonial mentality, and we need to become liberated in our own minds first. Nobody is going to do that for us. This is why we constructed the flags of Paseo Boricua with the explicit intention of saying we can improve our community. We said that to the gentrifiers because if they do it, they would displace us and increase rents. So, we have to develop! You can come here, but this is our space.

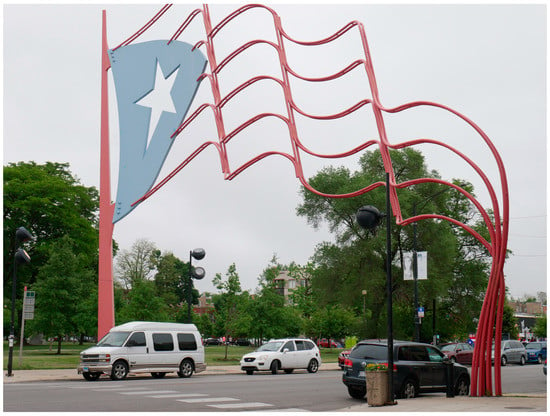

The flags of Paseo communicate different messages depending on the recipient. On the one hand, it communicates to outsiders that Humboldt Park is a Puerto Rican neighborhood. But it also communicates to Puerto Ricans that they have the ability and the power to develop. Puerto Ricans have been defined historically as deficient, as in a famous cartoon titled “School Begins: Uncle Sam lectures his class in Civilization”, where the pupils are labeled Philippines, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and Cuba (see Figure 2). Many Puerto Ricans have internalized colonialism. Some have come to believe that Puerto Ricans need Americans to rescue them from their poverty.

Figure 2.

School Begins: Uncle Sam lectures his class in Civilization, Image in the Public Domain Created by Louis, Published by Dalrymple Puck Magazine in 1899.

The Puerto Rican Agenda starts from the perspective that Puerto Ricans are capable of leading their development [2]. After years of attending Puerto Rican Agenda meetings, I became the co-chair of this collective of Puerto Rican leaders. This article uses participant observations of about eight years, notes and recording from these meetings, as well as formal and informal conversations with community leaders, friends, and acquaintances. I also interviewed realtors, government officials, residents, and others. By having conversations day in and day out with community leaders and others in the neighborhood, I became more and more interested in the role that symbols and collective identities of marginalized groups play in the politics of appropriating space. In this article, I discuss why symbols matter to marginalized groups and why they should matter to scholars. The next section conceptualizes the complexity of symbols, specifically the Puerto Rican flag, which is the most frequently used symbol among Puerto Ricans.

2. The Flag as a Symbol

To give an example of a symbol that is more pertinent to our study of the Puerto Rican community in Chicago, we could say that a flag is a symbol of a nation. As a member of the Puerto Rican Agenda shared,

The flag symbolizes our nation. One people, those from Puerto Rico and those from the diaspora. We are not bounded by space but by a common sense of identity. We are a giant Puerto Rican family. Cuba and Puerto Rico have inverted flags, they both were created to declare independence from Spanish Imperialism at the time in 1895. It was a call to revolution. It was created not in Puerto Rico, but in the United States, in New York City in fact. Today it is the most important national symbol. But before 1952, the flag was illegal. Those who dare to show it could go to jail. This is why we have it everywhere. Once illegal, today, it distinguishes us as Puerto Ricans everywhere we go.

An interpretation that resonates with me about the flags as a representation of the Puerto Rican nation is that the flag has historically been a symbol of declaring autonomy. It is also a way to unify people, those in Puerto Rico and those in the diaspora.

In the next paragraphs, we will go a little further into semiotics, which is the philosophical study of signs, including their creation and interpretation. Probably, the best maestro of semiotics is de Saussure, a renowned linguist who took the task of elucidating the dyadic of the sign as the relationship between the form (the signifier) and the concept represented (the signified). The two parts of the sign are then the relationship between the signifier and signified [3].

Something that we first must note is that Saussure’s whole project was to contradict positivism. The positivist would say, for example, the word “cat” is the synonym of the being that we humans call “cat”. For the positivist, they are the same, and there are no symbols. Saussure tried to say that the sound that we make when we say the word “cat” (the signifier) is not the same as the concept that exists of the being we call “cat” (the signified). The sound pattern that we produce for a cat is a symbol for something that exists; we use this word or sound to communicate a concept. Thus, the symbol encompasses both the signifier and the signified. The concept that a symbol communicates is historically contingent. In our particular culture and our particular time, the symbol of a “cat” (in a drawing or spoken word) stands for an animal that humans have domesticated and often keep as a pet; it’s from the feline family; in nature, they hunt mice, birds, crickets, etc. If I were going to use the symbol of a “cat” with a caveman or woman, they would probably not understand what we are trying to communicate, even if they spoke English or Spanish, or also if I drew a hieroglyph of a cat on the cave wall. The caveman or woman would not get what we are trying to communicate at all, because naturally, they cannot relate to our reality. All this to say that when symbols are taken outside of their historical context and thus the associations often made by our peer group, they become utterly useless. The construction and interpretation of a symbol can only be socially and communally achieved. It can only be shared amongst a particular group.

As the quote above describes, for Saussure the signified is immaterial or abstract [3]. Our example of the Puerto Rican flag (see Figure 3), a symbol for the “Puerto Rican nation”, is quite oversimplistic, as there is a psychological impression of the flag that does not equal the words “Puerto Rican nation”. A Puerto Rican might equate very loosely or strongly the flag with feelings about “home”, “community” or “family”. Maybe a particular family member comes to mind. Some might think about the U.S.—others about Chicago specifically if that is where they live right now. Some might have a general feeling of inspiration, happiness, hope, bravery, power, autonomy, independence, and so on—the feelings, interpretations and mental constructions of the signifier are endless. The thoughts, emotions, and feelings evoked by the Puerto Rican flag are simply impossible to be communicated by the phrase “the Puerto Rican nation”. Words cannot adequately express everything embedded in the symbol of the Puerto Rican flag. And that is the power of symbols.

Figure 3.

Saussure’s Dyadic System of “signified” and “signifier” as applied by the author.

2.1. Symbols of Gentrification

Gentrification refers to a type of neighborhood change linking the movement of wealthier inhabitants into more impoverished neighborhoods resulting in rent increases and the displacement of low-income residents [4]. The physical improvements that more affluent newcomers perform in their new space of residence or business become a sign that triggers further investment in an area. The signs of urban investment in a gentrifying area seem to be for the most part “known” to the point that supporters or condemners of gentrification often engage in considerable debate over these symbols: (1) the presence of white young people, coffee, frozen yogurt, cupcake and bike shops, hip restaurants, gourmet groceries, yoga, dance and art studios, (2) new residents walking dogs, biking, jogging, and with baby strollers, (3) new condominiums and housing developments, (4) cultural production events such as festivals, shows, street vendors and so on, (5) the re-branding of commercial districts with street signs, benches, and other beautification projects in the landscape. A resident explained,

There is a lot of symbols of gentrification, and you can see them approaching this traditionally Latino neighborhood. We are surrounded by condos, coffee shops, fancy bars, you name it. Cute dogs and yoga before you did not see any of that! Whatever is created for people who have money to throw away.

The direct inspection of displacement, which is the main feature of gentrification, is more often than not, invisible. Therefore, most observers seem to fixate on aesthetics, rent increases and the overall neighborhood upscaling, as well as the bodies associated with those changes—from black and brown to white—as ways to “read” gentrification.

Some of the symbols of gentrification are immaterial. For instance, the rhetoric used in the promotion of the newfound neighborhood: “hot”, “up and coming”, “revitalized”, “authentic” and so on [5]. Often this is accompanied by changing the name of the neighborhood usually on the web, real estate posts, and op-ed pieces. The rhetoric of an “up and coming” area paves the way for the settlement of new inhabitants. A realtor stated,

This community is up and coming. Location, location, location! Where you invest is important. This area is one of the best places to invest. But I bring my clients here, and some of them are scared because this area still a little rough. But I help my clients, and I tell them they can shape the area. There are specific places they can go that are attractive. Businesses are growing, little by little nice places are getting on the map. There are also great festivals for young people with music and food. And, now there is more police. You can call on the cops if you see someone potentially dangerous that looks like a gang member.

But policing doesn’t have to come from the cops. It can come from your neighbors too. A street vendor was harassed because he did not translate his menu,

This white lady came and called me racist and lazy because I did not translate the menu. She could have asked me and I would have explained to her what I had. But, instead, she chose to say that I was a racist. Then she went to complain to someone in government. I ended up translating the menu…it did not cross my mind that someone might want that. Honestly. I am sorry! The way she treated me affected me a lot. So much hate. I wonder why.

Cultural control could be considered another type of immaterial symbol, where the newcomers exercise a form of power over the original inhabitants [6]. The new cultural production of space results in more policing from neighbors who despise the old residents ways of being. For example, the public use of music could be perceived as a public nuance and hanging out with friends could be considered gang behavior. In general, practices associated with “the poor” are highly contested by newcomers who are from a very different social class and have little tolerance for the local customs of other groups. Even using Spanish in a meeting or having it in a menu without translating could be perceived as inappropriate or even a violent act. All these normal practices of the extant community somehow become symbols associated with otherness or a “culture of poverty” [7]. On this basis, poor people are classified as deficient in human capital, inassimilable, lacking desirable cultural values, skills, work ethic, and so on [8].

On the other hand, residents in poor communities often contest the diasporic forces that make them unstable as a community. The material symbols of gentrification such as new condominiums and the immaterial symbols—for example, the change of names or the presence of white young people in communities of color—are, often and undeniably, questioned. Local people protest against the existence of new shops and housing developments that do not seem to address their basic needs while displacing the local shops and places of residence that they can afford [9]. Some communities start grassroots “not for sale campaigns” to create consciousness among local homeowners who might be tempted to sell their homes and to generally make their frustrations known to those who intend to develop the place [10]. An organizer for Humboldt Park No Se Vende (Not for Sale) campaign, also a member of the Puerto Rican Agenda shared,

Young white people are approaching people about specific buildings. ‘Do you know who lives here?’ They would ask people around. They would also ask people sitting on their porches give them their business card. Start just a casual conversation with an elderly person to ask later on if they can go inside the home to see it. By any means necessary. Then they say ‘you can sell it for this much.’ They would pay with cash. Cash! That is how much money they have sitting around. They are predators. Some people do it. The temptation is too big. We don’t have that kind of money. But the whole point of this campaign is to tell long-term residents that if they own, they should not be taken advantage of (by outsiders). People are not getting the actual value of their homes. We understand. They are not going to give us the real value. They are offering $300,000. What are people going to do with that? They want us out of here, so they can raise the prices, and they are the one who gain. They want to take what we have. They are lobbing people.

These campaigns are managed by long-time residents to oppose the plans that either investors or new occupants of the area have in mind, hoping to dissuade them of their intentions. In other communities Not for Sale campaigns have placed signs telling yuppies to get out. Although some might see the attack on a particular group of people inappropriate, in this context a yuppie becomes a rather clear sign or external representation of the process of gentrification. Moreover, to put this process to a stop, residents in Humboldt Park and other communities put the flags of their country of origin, like the Puerto Rican flag, if they are immigrants. It is meant to condemn the process in the strongest terms possible [11]. Putting the flag of Puerto Rico is a way of declaring ownership of an area and putting an end to (or at least slowing down) gentrification [12]. Gentrification has always faced resistance from people whom it affects, the incumbent inhabitants of the area. In the lack of financial means to contest these changes, poor communities turn to tools that might allow them to re-claim their community. Humboldt Park serves as an example of such resistance.

2.2. Space Appropriation

In this article, I seek to bring to the forefront how people claim space either by using it, being there or by creating territorial markers—such as murals and symbols and other evidence of a group’s presence. Space appropriation is the act of occupying a space for means of residence or even business without necessarily owning the area [13]. First and foremost, people come to appropriate space by using it. A member of the Puerto Rican Agenda made a call to action to use space as a way of making claims to it:

The City of Chicago developed the 606. But it doesn’t have to be like the Highland in Manhattan for tourist and gentrifiers. We can change the attitude of our people. They are already here. They are up in here. And we are sitting saying we are not going to use it. No! That park is public! Our role as people of color is to be present. To show our presence in this neighborhood. Not be willing to give up the park, we were the ones who fought for it. We supported it because it was going to be great for our kids and our families. We build this community for decades and is not going to be taken over. I want to go to that park and see people like me enjoying it.

The phenomenon of claiming space has been discussed for instance in Lefebvre (1984) “right to the city” [14]. Sack (1986) came to name this trend of appropriating space “territoriality” [15]. Repic (2011) attributes this to mostly rural urban migration owing to the demand for labor vis-à-vis the opportunities that industrial development brings to people [16]. Cohen (1969), Strathern (1975), and Goddard (2005) are all for the idea that as soon as rural people reach urban centers, they tend to create communities similar in values, norms, and traditions to those they are used to in their rural settling [17,18,19]. This, with time, builds in them a sense of belonging to what might feel like home and eventually become home. Social networks become extremely important to them in their everyday survival [20]. In times of hardship, these networks work as umbrella protectorates to their members [21].

Secondly, people appropriate space by creating territorial markers and symbols [22]. According to Sack, these territories are secured via the symbolic cultural expression of groups (1986). Relph (1976) reiterates on this issue by adding the very human need for association with places of significance [23]. It becomes, therefore, a regular practice that once a specific group has identified an area and occupied it, they seek to mark it using several methods so that they can become the recognized members of that place. Paseo Boricua is an excellent example of that. It marks the Puerto Rican neighborhood. One member of the Puerto Rican Agenda explains,

Puerto Ricans historically do not buy homes. But historically, this neighborhood has been the Puerto Rican neighborhood. That means that here there is more Puerto Ricans homeowners and business owners. We did a study that shows that this place had the most Puerto Rican owned businesses. This is the reason that the flags were placed between Western and California. Because there was already a presence (of Puerto Ricans) here. So, already there were a lot of owners. But again, the majority of Puerto Ricans are renters. But basically, by having owners here and by claiming this space as Puerto Rican with restaurants, the flags, murals and everything that makes this is a Puerto Rican community. At the core what we are saying is that we own this area. In essence, this is our area. This is our space.

In capitalist and western society, where all the land is already owned, it is hard for the poor to grab land and claim ownership. I argue that people turn to other means of appropriation, the creation of murals and other cultural symbols to declare a space of their own.

2.3. Symbols in Humboldt Park

In the context of Humboldt Park, I explore various types of symbols. The first type involves markers around the concept of a distinct ethnic group such as the word Puerto Rican. An important point to make here is that we cannot possibly define what a Puerto Rican is or means. All we know is that Puerto Ricans as a particular ethnic group exist, in the sense that there is a group of people who identify themselves as Puerto Ricans. We could say a little more than this—that self-identification with the Puerto Rican culture and people are what make someone a Puerto Rican.

The second type involves symbols associated with being Puerto Rican or belonging to this specific ethnic group, such as the Puerto Rican flag. Puertoricanness always surrounds other concepts that require a particular heritage and folklore such as the Spanish language, indigenous graffiti, bomba music, native food, and so forth. In the abstract, these symbols equate to Puertoricanness. However, this doesn’t mean that an individual is not Puerto Rican because he or she does not speak Spanish, they do not know how to draw a cemí, dance bomba or make fried plantains. As long as someone declares that he or she is a Puerto Rican and other people who also self-identify as Puerto Rican accept this person as a member of the group called “Puerto Rican”, then you can build a community of Puerto Ricans who are held together by the “Puerto Rican” symbol. A community leader told me,

You know that you are Puerto Rican when you display the Puerto Rican flag. You can be born and raised on the Island or here in Chicago. You love and dance salsa, Reggaeton, or trova. Enjoy rice and beans with pretty much anything […] I think they just have to be proud of being Puerto Rican by calling themselves Puerto Rican.

These amalgam of symbols that express the Puerto Rican identity (the word Puerto Rican, the food, flags, and so forth), as interviewees see them, become an integral part of my analysis. On the other side of the spectrum, symbols associated with the opposite of being Puerto Rican—namely, being a “white gentrifier”—are also treated quite heavily by interviewees of this study. For example, Puerto Rican interviewees would discuss what the “white gentrifier” consumes and their tastes for food, clothing, modes of transportation, third-places, as well as their everyday activities like running and walking their dogs. As one community leader expressed,

The gentrifiers are overwhelmly white. But not all of them are white. We speak more in generalities, right? In the social structure of the United States, white people are disproportionately middle-class because of redlining and other policies that institutionalized privilege. Disproportionally people of color, black and brown people, tend to be lower income. We can go back and do a history lesson on this. White people have historical privileges […] Some things or preferences are associated with white people who are not working-class…like specialty supermarkets, vegan restaurants, yoga studios, pet shops, and the list goes on. They do not like this because they are white, is because they are middle-class. They have the disposable income to be able to afford these things. That is one explanation. But there is also culture. There is a middle-class culture in the United States. You can be black and run with your dog. But if I see you doing this, is very likely that you are not working-class, that you are middle-class. But again, the majority of Puerto Ricans are not middle-class, while the majority of the white people moving here are.

Saussure underlined that “concepts ... are defined not positively, concerning their content, but negatively by contrast with other items in the same system” [2] (p. 115). In a gentrifying space, the Puerto Rican and the white gentrifier are part of the same system, namely, the neighborhood. Some symbols authenticate “Puertoricanness”, or on the other side of the spectrum they authenticate “whiteness”. Thus, this study looks at the relationship of concepts, as negatively expressed by symbols employed by research participants. That is, between the binary oppositions of privileged signifier—“white”—and the non-privileged signifier, “Puerto Rican”.

3. Collective Identity

The following section is not meant to give an exhaustive definition of the concept of collective identity, its purpose is to provide a basis that could be used later on to understand how Puerto Ricans, based on their collective identity, organize community development projects in Humboldt Park, which in turn allows them to claim ownership over space. One thing to point out is that the term collective identity in the literature is often mixed up with other concepts such as identity politics, social identity, collective consciousness, among others [24,25,26]. Although there are several grey areas in these concepts and authors do not share perspectives on all points, I will assume these terms to be for the most part synonymous. In this section, I will refer to the term collective identity most times, but I have also considered literature under the identity politics label.

While a number of scholars argue that all identity is collective because it is socially constructed, in this section we will use the term collective identity instead of identity to denote that I am interested in the sociology of identity as opposed to its psychology [27,28,29]. That established, collective identity implies a group unity based on a claim of being. For example, racial, gender, sexual orientation, class and collective national identities suggest that individuals in these broad and relatively fixed social categories share similar experiences. Additionally, collective identity could also be formed out of dress, language, social roles, values, functions, and so on. A simple definition would then be, “identity as an individual’s cognitive, moral, and emotional connection with a broader community, category, practice, or institution” [30]. A Puerto Rican woman told me,

I am Puerto Rican, and I embrace my culture. I am connected to my culture and where I am from. There are different ways of expressing it. I am proud of being Boricua. There is an energy that identifies us. It is standing in the shoulder of those who came before me. To remember where I am from is important to me. I am a part of the Puerto Rican community. I say Puerto Rican a lot because most people do not know what we are. It’s important to show other people our culture. They have to know that we are around. The first language I learned is Spanish, even though I do not have an accent. I dance salsa and bachata, merengue. I express my indent not as an individual but as a Puerto Rican. This is my culture. It influences my individuality. It is part of me.

There are two crucial elements of collective identity: one, the individual must accept the identity not having perceivable incentives or coercion and two, there must be some social recognition by those within the group. This second element is what distinguishes personal identity from a collective identity. For example, my cultural heritage may make me a Puerto Rican, and I might have an individual agreement to being Puerto Rican, but unless other Puerto Ricans recognize my membership in that community, my identity as a collective cannot be fulfilled. In other words, collective identity is being with others [31].

Membership—who is to be included or excluded from a group—is always a contested issue as it is practically impossible to define the boundaries of belonging theoretically in itself. Therefore, difference is one of the most critical elements of constructing collective identities [32]. How do we distinguish a hunter from a gatherer? In the specific or individual basis, we might observe that a hunter throws spears at animals, whereas a gatherer collects fruits and vegetables in nature. In the abstract form, however, we may say that we know that a gatherer is a gatherer because he or she is not a hunter and vice versa. In other words, social relations are dialectically formulated in opposing relations—there is a thesis on the one hand and an antithesis on the other. For example, the identity of the feudal lord is distinguished by its difference from the serf. When emphasizing difference, a symbolic barrier is used to recognize someone who belongs to the group versus someone who does not. Nonetheless, often, there are material and physical manifestations of these differences that are evident to each reference group being clothing, possessions, and so on.

3.1. Linkages Between Space and Identity

Space is an essential element in the formation of collective identity [33]. National identity, for instance, involves the subjects’ perception of the importance of the national territory [34]. Likewise, residents of an urban neighborhood also rely on a shared history, shared experiences and traditions. Thus, the geography of the community could also become the basis for new forms of collective identity [35].

Moreover, in a capitalist society, entire neighborhoods tend to be composed of a particular class (e.g., working class) and this social space can potentially produce class consciousness [36]. Similarly, the spatial organization that capitalist society creates based on class tends to be correlated with ethnicity and race. On this basis, capitalism produces spaces that are considered to be either superior or inferior, which shows us the construction of differences through geography [37]. For instance, the association of ghettoization of Puerto Ricans versus the association of whites with wealth and privilege. These differences are accomplished through an array of traditional social and economic spatial practices. I emphasize the spatiality of these social relations, as in the context of capitalist production of urban spaces, and thus, the neighborhood, become a space of difference and collective identity.

Rinaldo (2002) examines the relationship between physical space and collective identity in Paseo Boricua [38]. The Puerto Rican community of Chicago is heavily tied to its urban area, Humboldt Park, and this space is considered a stronghold for cultural identity. As a community leader explained,

Most of them (the gentrifiers) are young, white, and middle-class. The rents go up, and that is a structural problem. People of color have been thrown out like nothing, evicted, foreclosed. Long-term residents have been systemically displaced because they are low-paying. They have to leave because they cannot buy homes. They (the gentrifiers) are getting closer and closer to Paseo Boricua threatening our cultural heritage and ability to stay because we are lower income. This is a new form of colonialism, this why we had to put the flags. What is the first thing that the U.S. did when they went to the moon? They planted a flag.

Similarly, Rinaldo argues that the Puerto Rican spirit is trying to shake its history of U.S. colonialism. Puerto Rico has belonged to the United States since the late 1800s and was previously a colony of Spain. While the country was granted the rights of a commonwealth territory rather than a colony in the mid-1900s, Puerto Rico remains dependent on the United States. Its population is mostly poor, unemployed, and dependent on welfare. And although it has its flag and elected governor, the island lacks true independence. According to Rinaldo’s ethnographic study in Paseo Boricua, this has weighed heavily on its people and has influenced Puerto Rican identity.

3.2. Identity Politics: A New Form of Organizing

An important point to make here, however, is that in the literature more often than not, collective identity is employed by a minority group within a social hierarchy—females, people of color, gays and lesbians, ethnic minorities, nationals, the working class and so on—in opposition to the dominant group. Collective identity as a subject of study aroused among social movement theorists who were studying women’s rights, civil rights, gay rights and the New Left in the 1960s [26]. These theorists were particularly interested in how collective identity motivated people to act without any direct material incentives being laid out on the table, like in the case of labor unions.

Theorizations on collective identity challenged the class identity as put forward by Marxists, to argue that people also organized based on other identities such as sex, gender, ethnicity, race, and so forth [39]. Collective identity offered new conceptualizations to marginalized groups from which they could denounce power, inequality, and other forms of oppression. This is true for Puerto Ricans as a community leader explained to me,

We started organizations in the 60s. We were in a period of history where Puerto Ricans saw injustices. Take for example the Puerto Rican Riots of 1966 after a policeman wounded a young person. We knew then that something was wrong. People rioted for three days. There was an atmosphere of rebellion because the government and the institutions ignored Puerto Ricans. And we said we need to help each other as Puerto Ricans. We started to organize in the Humboldt Park neighborhood.

As Manuel Castells (2000) noted, identity politics (which is often equated with collective identity) is based on an ethnic, racial or religious community’s rejection of the disembodied and individualized global culture that capitalism and the network society produces [40]. Under capitalism, there are two disparate but overlapping tendencies: globalization (which seeks homogenization) and localization (which aims differentiation). In a neoliberal society, the individual raises over the collective. As a response then, in the absence of labor politics, nowadays, identity politics emerges as a new form of demanding the redistribution of equality and social goods, often at the neighborhood level.

4. Conclusions

This research addresses the gap that exists in symbology by developing a conceptual context on the social pathways of gentrification, community development, and introducing the idea of “reading” communities and their claims of ownership over space as a literary text, not as a reification. Saussure underlined the relative arbitrariness of the symbol, meaning that there is no self-evident or natural association between the signifier and the signified. Because symbols depend on relations, they are not things in themselves that can then be simply defined. Again, rationalizations can be made, but no explanation of such phenomenon exists. Symbols communicate meaning, and because of that, they are dependent on sense-making. This fact does not, however, make them “simple”. Positivism implies that meaning is extracted without the act of interpretation and that the symbol has some essential or intrinsic nature. Nonetheless, Saussure understood that a symbol has no absolute or actual value that is independent of its context.

In this article, I have shown how the Puerto Rican collective identity was used to give meaning and value to the practice of community development via the use of symbols that contest gentrification. Gentrification in this instance refers to a social process of urban renewal where the original inhabitants are forced to move. For Humboldt Park in Chicago, this involves landlords refurbishing blocks of flats or houses to a “higher” standard, or of new developments on plots of land previously used for industry or business. Previous tenants, often Puerto Rican or Latino and of a lower income bracket, are evicted or bought off. The new dwellings attract a more affluent crowd, usually white students, professionals, IT specialists, or artists. Rents go up, and the Latino population cannot continue living in the area. Locally owned businesses with Puerto Rican influences are forced to close as upper-class stores and restaurants move into the area to cater to its new inhabitants [41]. Local activists believe that this process of gentrification is about removing unwanted minorities from the city center and allowing Chicago to become more chic and white—in this landscape, their collective identity becomes essential to mobilize politically. Gentrification is a genuine threat to the community of Humboldt Park and one they respond actively to through symbols of appropriation.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Will Smiley for editing the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Goethe, J.W. Maxims and Reflections, Revised Edition; Penguin Classics: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cintrón, R.; Toro-Morn, M.; García, I.; Scott, E. 60 Years of Migration: Puerto Ricans in Chicagoland. The Puerto Rican Agenda. 2012. Available online: http://www.puertoricanchicago.org/ (accessed on 5 September 2018).

- Saussure, F.; Harris, R. Course in General Linguistics, 2nd ed.; Open Court: La Salle, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N.; Williams, P. Gentrification of the City; Allen & Unwin: Boston, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kasinitz, P. The Gentrification of ‘Boerum Hill’: Neighborhood Change and Conflicts over Definitions. Qual. Sociol. 1988, 11, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukin, S. The Cultures of Cities, 1st ed.; Blackwell Publishers Ltd.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, W.J. When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor, 1st ed.; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Toro-Morn, M.; García, I. Gendered Fault Lines: A Demographic Profile of Puerto Rican Women in the United States Published. CENTRO J. 2017, 29, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, D.K.; Comey, J.; Padilla, S. In the Face of Gentrification. Available online: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/face-gentrification (accessed on 5 September 2018).

- Garcia Zambrana, I. The Puerto Rican Identity: Reconstructing Ownership in the Face of Change. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Naegler, L. Gentrification and Resistance: Cultural Criminology, Control, and the Commodification of Urban Protest in Hamburg; LIT Verlag: Münster, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- García, I. Paseo Boricua. Identity, Symbols, and Ownership. Am. Crítica 2017, 1, 117–138. [Google Scholar]

- Orlando, A. Urban common space, heterotopia and the right to the city: Reflections on the ideas of Henri Lefebvre and David Harvey. Braz. J. Urban Manag. 2014, 6, 146–157. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space, 1st ed.; Nicholson-Smith, D., Translator; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sack, R.D. Human Territoriality: Its Theory and History; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Repic, J. Appropriation of Space and Water in Informal Urban Settlements of Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea. Anthropol. Notebooks 2011, 17, 73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, A. Custom and Politics in Urban Africa: A Study of Hausa Migrants in Yoruba Towns; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Strathern, M. No Money on Our Skins: Hagen Migrants in Port Moresby; Australian National University: Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, M. The Unseen City: Anthropological Perspectives on Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea; Pandanus Books, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University: Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hannerz, U. Exploring the City: Inquiries Toward an Urban Anthropology, 1st ed.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Colombijn, F.; Erdentug, A. Introduction: Urban Space and Ethnicity. In Urban Ethnic Encounters: The Spatial Consequences; Colombijn, F., Erdentug, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pickering, J.; Kintrea, K.; Bannister, J. Invisible Walls and Visible Youth: Territoriality among Young People in British Cities. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 945–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relph, E. Place and Placelessness. Available online: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446213742.n5 (accessed on 5 September 2018).

- Schlesinger, A. The Disuniting of America: Reflections on a Multicultural Society; Whittle Books: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H. Social Identity and Intergroup Behavior. Soc. Sci. Inf. 1974, 13, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, E. The Division of Labor in Society by Emile Durkheim, 2nd ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstadt, S.N. The Construction of Collective Identities: Some Analytical and Comparative Indications. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 1998, 1, 229–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.; Breinlinger, S. Identity and Injustice: Exploring Women’s Participation in Collective Action. J. Commun. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 5, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, R.S. Experiences of Intellectually Gifted Students in an Egalitarian and Inclusive Educational System: A Survey Study. J. Educ. Gift. 2010, 33, 536–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polletta, F.; Jasper, J.M. Collective Identity and Social Movements. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2001, 27, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro-Morn, M.; Zambrana, I.G.; Alicea, M. Introduction, De Bandera a Bandera (From Flag to Flag) New Scholarship about the Puerto Rican Diaspora in Chicago. CENTRO J. 2016, 28, 4–35. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward, K. Identity and Difference, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- García, I. Learning about Neighborhood Identity, Streets as Places, and Community Engagement in a Chicago Studio Course. Transform. J. Incl. Sch. Pedagog. 2017, 27, 142–157. [Google Scholar]

- Pile, S.; Keith, M. Place and the Politics of Identity; Pile, S., Keith, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sennett, R. The Uses of Disorder: Personal Identity and City Life; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D.; Denton, N. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sibley, D. Geographies of Exclusion: Society and Difference in the West, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldo, R. Space of Resistance: The Puerto Rican Cultural Center and Humboldt Park. Cult. Crit. 2002, 50, 135–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, C. Social Theory and the Politics of Identity; Calhoun, C., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. The Rise of The Network Society: The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- García, I. The Puerto Rican Business District as a Community Strategy for Resistance Gentrification in Chicago. PLERUS 2015, 25, 79–98. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).