Abstract

Museums are cultural spaces that should promote accessibility and inclusion for all. However, accessibility is often interpreted as removing physical barriers, overlooking less visible obstacles—such as cognitive, sensory, and communicative challenges—that can profoundly shape the museum experience for people with intellectual disabilities. This paper presents an ethnographic case study conducted in the Veneto region of Italy, in collaboration with a group of individuals with Down Syndrome (DS), aiming to explore their lived experiences of a museum visit. Drawing on participant observation and in-depth interviews, the study examines how visitors with DS engage with the museum environment on behavioural and sensory levels. Findings reveal the impact of environmental stimuli, difficulties in navigating abstract or densely layered visual content, and the importance of embodied interaction with objects and spatial cues. Positive experiences emerged from relational engagement, guided facilitation, and the use of multi-sensory supports. The study underscores the need for museums to move beyond compensatory or charity-based models of accessibility, and instead adopt inclusive design principles that value neurodiversity and participatory co-creation. In doing so, this research contributes to the emerging discourse on how museums can become safe spaces for learning, dialogue, and self-expression for people with intellectual disabilities.

1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, the concept of the museum and its associated missions have undergone a significant transformation. While the traditional functions of conservation, safeguarding, and cultural heritage enhancement remain central, museums can no longer be conceived as isolated institutions, detached from their social environment and confined within architecturally imposing buildings. Reflecting this shift, the latest definition of the museum proposed by the International Council of Museums (ICOM) incorporates a series of terms that had never appeared in earlier versions [1]. For the first time, words such as accessibility, inclusivity, diversity, sustainability, participation, and varied experience are explicitly mentioned.

The redefinition calls upon museums to fulfil a clear mandate of public engagement, opening up their research, collections, and programming to society and actively involving the broadest possible range of people. The issue hinges on what this multitude encompasses, following a decolonial understanding and an interpretation that counters ableism [2].

Museums are increasingly recognised as agents of social and economic change, promoting cultural democratisation and affirming the universal right to knowledge, representation, and cultural participation [3]. Nevertheless, people with developmental, emotional, physical or psychiatric (dis)abilities are often excluded from museum-based activities, as they frequently have to rely on caregivers to benefit from the foregoing rights.

At their core, museums have enormous potential to reshape society’s view of disability: not as a deficit, but as a form of human diversity to be recognised, engaged with, and included [4,5,6]. As cultural institutions that convey collective values, museums can either perpetuate social exclusion or foster inclusive narratives. Since they are not neutral spaces, museums actively participate in shaping public understandings of disability, constructing the terms through which difference is recognised and discussed. Accessibility, in this renewed framework, becomes an interdisciplinary field of practice and research, grounded in the capacity to step into the perspectives of others.

Historically, disability has been interpreted through the lens of the medical or individual model, which positions disability as a condition to be diagnosed, treated, or managed [7]. This perspective tends to reinforce negative stereotypes and often homogenises people with disabilities, obscuring the diversity of their experiences, identities, and capacities. In contrast, the social model of disability emphasises the environmental and social barriers that hinder participation. It reframes disability as a relational phenomenon, highlighting how inadequate responses from society (through physical, cultural, social, and economic barriers) create disabling conditions. The very expression “person with a disability” emphasises putting the individual, rather than their condition, at the forefront.

Over the last five decades, the field of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDDs) has undergone a significant transformation [8]. The initialism IDD recognizes the interdependence of cognitive, social, and environmental dimensions. Intellectual disability (ID) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by limitations in cognitive functioning and adaptive behaviours [9]. Depending on its severity, ID may affect reasoning, memory, planning, problem-solving, and abstraction. Social and communicative skills are often impacted, as are self-care abilities, educational and occupational functioning, and, consequently, economic autonomy [10,11]. Causes can range from genetic conditions (such as Down Syndrome) to congenital anomalies or unknown etiologies. The barriers experienced by people with ID are rarely singular and often intersect across multiple domains: economic, physical, sensory, technological, linguistic, intellectual, emotional, and cultural. These barriers may remain invisible to most, yet they affect every phase of a museum visit: from navigating the website to booking tickets, from entering the space to understanding interpretive materials.

For individuals with developmental or intellectual disabilities, offerings often include multisensory activities, hands-on learning opportunities, simplified language (Easy-to-Read), augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) tools, and visual schedules or social stories to support pre-visit planning. Adjustments may include reduced lighting and noise, noise-cancelling headphones, sensory maps that mark overstimulating or quiet areas, and designated rest spaces. These strategies not only improve access but also foster self-awareness, skill-building, and greater engagement with complex ideas [12]. Tactile and embodied experiences are particularly effective in bridging the perceived intellectual distance between the visitor and the displayed object, helping to create a more intimate and empowering relationship with cultural content.

While such efforts are important, they tend to focus predominantly on children with IDD, often accompanied by family members or caregivers. This reflects a persistent infantilisation of intellectual disability, whereby disability is primarily imagined in childhood and rarely in adult life. As a result, adults with intellectual disabilities—particularly those with limited verbal communication—continue to be excluded from many aspects of cultural life. In this context, the concept of the museum as a safe space for adults with IDD remains underexplored. The term safe space implies more than the absence of harm; it suggests the presence of trust, autonomy, dignity, and meaningful engagement. It requires environments that respect the agency of neurodivergent individuals and actively dismantle the implicit hierarchies that can structure museum visits—from the presentation of information to the facilitation of participation.

For many people with IDD, artmaking serves as a meaningful and socially accepted form of non-verbal expression [13,14,15]. When framed within a therapeutic context, such as art therapy, it can offer tools for emotional processing and self-representation [16]. However, the importance of art extends beyond therapy; it can also serve as a vehicle for critical engagement in cultural life. Within this framework, the notion of “Design for All” (DfA) offers a holistic approach to accessibility. Rather than targeting a specific “user group”, DfA promotes diversity, social inclusion, and equality as foundational design principles. Applied to museums, this concept becomes both a creative challenge and an ethical imperative, requiring the involvement of interdisciplinary teams and, crucially, the active participation of people with disabilities throughout the design process [17,18,19]. Participatory design does more than remove barriers: it makes disability visible, both physically and symbolically, transforming it from a marginalised condition to a shared point of reference. By involving people with disabilities in the creation of inclusive exhibitions and environments, museums can foster virtuous cycles of encounter, dissolving labels and freeing disability from the confines of exceptionality and exclusion.

As noted by Ciaccheri and Fornasari [20], accessibility in the museum field possesses its own “grammar” and is constantly evolving, driven by the search for new methods that can expand access to spaces, content, and services.

A commonly accepted definition frames accessibility as the removal of barriers and the creation of conditions that enable as many people as possible to take part in cultural life. Crucially, the term itself does not necessarily refer to disability. On the contrary, it challenges the persistent stereotype that accessibility is a niche concern, relevant only to a minority of people with limited autonomy or “special needs”. This semantic distinction is particularly important in the museum context, as it shapes the conceptual approach to design and directly affects the outcome of inclusion initiatives.

This reframing requires the removal of both physical and communicative barriers, as well as a re-evaluation of how museum environments are designed and presented. The principles of Universal Design (UD) offer a compelling framework for this shift [21], promoting environments that are equitable, intuitive, and accommodating of a wide range of abilities and preferences [22]. As applied to museums, Universal Design encourages institutions to integrate inclusive practices from the outset, rather than as afterthoughts. Sherril York [17] documents how involving people with disabilities in all stages of exhibition planning and design led to more inclusive and meaningful experiences for all visitors. This participatory approach moves beyond a charity-based or compensatory view of disability and instead acknowledges people with disabilities as active cultural agents with valuable insight to offer.

Many museums have developed programming for a wide range of disabilities: from mobility and sensory impairments to developmental, learning, and cognitive disabilities, including autism and dementia.

This paper presents an ethnographic case study conducted with a group of Italian adults with Down syndrome (DS), addressing a gap in the literature on intellectual disability and museum accessibility. The study explores the extent to which people with intellectual disabilities can access museum environments and their contents autonomously. It examines the conditions that shape these experiences as inclusive or exclusionary.

Rather than approaching disability from an external or abstract perspective, the research adopts a participatory ethnographic approach, engaging directly with people with intellectual disabilities to identify barriers within museum exhibitions and to reflect on the feasibility of their active involvement in shaping inclusive museum practices. Grounded in participants’ lived experiences, the study is guided by the following research question: can the museum be conceived as a space where intellectual disability is addressed with, from, and through the perspectives of people with intellectual disabilities themselves?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethnographic Approach and Participatory Principles

This study adopts an ethnographic approach to investigate how individuals with DS experience and engage with the museum environment. Ethnography, with its emphasis on close observation, immersion, and co-presence, is particularly suited for exploring embodied, relational, and contextual dimensions of experience [23], especially when working with communities whose voices have historically been marginalised or misrepresented in research [24]. Rather than extracting data from participants, ethnography seeks to build relational knowledge through shared time, dialogue, and participation.

The fieldwork was conducted with a group of adults with DS from the Province of Treviso, Italy, and focused on two museum visits: the exhibition “Banksy and Friends: The Art of Rebellion” at the JMuseo in Jesolo, and the interactive exhibition Museo Illusione tra Arte e Scienza in Verona. The aim was to explore, from an emic perspective, how visitors with DS perceive, navigate, and make sense of the museum space: both physically and symbolically.

The ethnographic design included the following elements.

- Identification of a participant group suitable for the research question and broadly representative of their community context;

- Contextual analysis of the physical, social, and cultural environment surrounding the lives of participants, including how regional and institutional factors shaped their access to cultural spaces;

- In-depth interviews, tailored to the communicative styles and preferences of each participant, aimed to elicit key indicators such as fears, motivations, behavioural patterns, aspirations, and perceived challenges in museum contexts;

- Development and use of tailored tools (such as visual prompts, simplified guides, and multisensory aids) designed to enhance comprehension, facilitate self-expression, and deepen participants’ awareness of their own experience;

- Daily co-presence and shared routines, including travel, meals, informal activities, and group interactions, which allowed for the emergence of spontaneous insights and relational trust.

Central to this approach was the resort to participant observation, which involved not only observing behaviours during the museum visit but also actively sharing space, time, and activities with the participants. This included the informal moments before and after the visit, which often revealed emotional and social dynamics not immediately visible during the exhibition itself. Throughout the study, the researcher (E.T.) maintained a field diary, where observations, analytical reflections, and personal challenges were recorded. This reflexive journal functioned as both a methodological and ethical tool, documenting the evolving relationship between the investigator and the participant group, and capturing nuances that might otherwise be overlooked in formal data collection. Ultimately, this methodological framework aimed to create a research encounter that was not only about participants, but with them. This meant valuing their perspectives, expressions, and everyday strategies as essential contributions to understanding how museums can become more inclusive, meaningful, and safe for adults with intellectual disabilities.

2.2. Participant Profiles and Observational Criteria

The participants in this study were recruited through the Associazione Italiana Persone Down (AIPD), a national reference point in Italy for families and professionals working in the field of Down Syndrome. The research activities were carried out in collaboration with the local branch, AIPD Marca Trevigiana, which facilitated access to the community and helped ensure the study’s relevance and ethical integrity.

The cohort of participants consisted of two groups of adults with DS (with a total of six men and six women), ranging in age from 21 to 34 years. All participants were living with moderate intellectual disability and demonstrated fair verbal communication skills. One individual presented with a more severe form of intellectual disability, characterised by limited intelligibility of speech and an inability to read or write. All participants had previously taken part in AIPD programmes and were familiar with one another through various social, educational, or recreational activities. A licensed occupational therapist was present during several sessions, contributing professional insight and ensuring an appropriate level of support.

The selection of participants was guided by their communicative proficiency, which was indispensable for establishing relationships based on trust, reciprocity, and emotional resonance—cornerstones of the ethnographic method. To ensure ethical participation, the research team developed an Easy-to-Read information sheet incorporating elements of Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC). This document clearly explained the purpose of the study, how the research would be conducted, and what kind of involvement was expected. The consent process was designed to be as accessible and participatory as possible. The document was read and discussed collectively with the group, using visual support and simplified language to ensure comprehension. Particular attention was given to emphasising participants’ agency: they were reminded that their help was essential for a collective endeavour, but also that they were free to withdraw from the study at any time, without explanation or consequence (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Discussing the information sheet with part of the group.

From a cognitive perspective, individuals with DS often experience difficulties with memory, cognitive flexibility, and the processing of complex information. To address these needs, the information session made extensive use of imagery and examples to evoke memories and spark curiosity about the upcoming experience. Additionally, a short visit booklet was prepared for participants with accessible information about the steps involved in the museum experience (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Part of the group reading and filling in the visit booklet.

The participant observations and interviews were conducted during two residential summer retreats organised by AIPD Marca Trevigiana. The first group participated in June 2024, the second in April 2025. In both cases, the participants spent a week living together in self-managed apartments in Jesolo Lido, a seaside town near Venice. The immersive setting allowed the researcher (E.T.) to share daily routines, meals, and activities with the group, thereby facilitating the kind of close, sustained engagement essential to ethnographic work. The fieldwork took place in both formal and informal contexts, with interviews conducted one-on-one or in small groups, depending on the participants’ preferences and comfort levels, utilising a variety of tools, including games, music, dancing, and visual prompts. Other insights were not elicited verbally but emerged through the observation of behaviour, body language, social dynamics, and emotional responses during everyday life. These observations were systematically recorded in a field diary, which captured not only what happened, but how it was experienced and interpreted, by both the participants and the researcher.

The study focused on a set of observational and narrative indicators, developed to guide the interviews and frame the ethnographic analysis. These were grouped into five thematic areas:

- Autonomy

- Awareness of having Down Syndrome;

- Capacity to travel independently (e.g., use of public transport);

- Capability to ask for information in person or by phone;

- Current employment or vocational activities.

- Social Networks and Points of Reference

- Social integration (e.g., participation in associations, sports, scouts, or church activities);

- Present and future figures of reference;

- Emotional relationships and friendships.

- Personal Insecurities and Strengths

- Elements that provoke fear or anxiety;

- Elements that enhance self-confidence or spark joy;

- Typical emotional reactions when travelling alone.

- Personal Interests and Aspirations

- Management of free time;

- Personal interests and passions;

- Professional dreams and vocational goals.

- Cultural and Museum Experiences

- Prior experiences with cultural events (concerts, festivals, performances, etc.);

- Specific experiences in museums;

- Expectations and imaginings about what a museum is or could be.

By mapping participants’ extents, desires, anxieties, and cultural horizons, this section of the study aimed to understand how people with DS position themselves in relation to the museum: not only as visitors, but as individuals with a cultural voice, aesthetic sensibilities, and the right to shape public space.

2.3. Research Settings

The ethnographic research unfolded across two distinct phases, corresponding to two group-based summer retreats organised by AIPD Marca Trevigiana. Each phase included a museum visit integrated within a week-long residential programme, providing a rich context for both structured and informal observation. Although the two groups participated in separate visits, one participant was involved in both experiences, offering a unique point of comparison. The selection of the two museums was informed by practical considerations: specifically, their logistical compatibility with the broader schedule of group activities during the residential stays. However, the choice of exhibitions was left to the participants themselves, aligning with the project’s participatory ethos and reinforcing the agency of people with DS as cultural decision-makers. Together, the following research settings offered contrasting yet complementary environments in which to observe the responses of adults with intellectual disabilities to different types of exhibition content: one grounded in political and aesthetic provocation, the other in perceptual exploration and scientific wonder. These differences provided valuable insights into how environmental, thematic, and sensory elements shape inclusion, comprehension, and enjoyment in the museum context.

- Phase One: JMuseo, Jesolo (June 2024)

During the first retreat, held in June 2024, the initial group of participants visited JMuseo, the civic museum of the city of Jesolo. At the time of the visit, the museum was hosting the temporary exhibition “Banksy & Friends: The Art of Rebellion”, curated by Piernicola Maria Di Iorio. Spread across the third and fourth floors, the exhibition featured over 90 works by some of the most prominent contemporary street artists associated with post-graffiti and guerrilla art. Artists included Banksy, Jago, TVBoy, Takashi Murakami, and Obey, among others. The exhibition aimed to provoke reflection on social systems, political dissent, and the contradictions of contemporary society. Such topics are not immediately associated with audiences with intellectual disabilities, and thus provide a meaningful context in which to explore issues of interpretation, inclusion, and engagement.

- Phase Two: Museo Illusione tra Arte e Scienza, Verona (April 2025)

The second phase of the research took place in April 2025, when the second group of participants visited the Museo Illusione tra Arte e Scienza in Verona, which has since permanently closed. At the time of the visit, the museum housed 60 interactive installations and photographic displays, designed to immerse visitors in the phenomena of perceptual illusions. The objective was to encourage learning through play, offering an environment in which scientific concepts were communicated through humour, surprise, and embodied experience. Such a setting particularly suited for examining sensory engagement and cognitive accessibility.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

This study is grounded in the ethical principle of participation, following the widely recognised motto “Nothing about us without us”, a call to action that has shaped the disability rights movement over the past decades. Originating in 16th-century Polish political discourse and later adopted by disability activism in the 1990s, the phrase underscores a fundamental demand: that people with disabilities be directly involved in decisions, policies, and practices that affect their lives. In this research, the motto becomes not only a statement of intent but a methodological and ethical imperative, realised through the use of participant observation and the shared construction of knowledge with people with Down Syndrome.

In practical terms, the study sought to merge theory and practice by co-developing the research design, tools, and interpretive frameworks with participants and their supporting association (AIPD). The aim was not only to identify invisible barriers within museum environments, but also to foster the development of tools that promote active cultural participation, self-determination, and critical awareness. As Gilmartin and Slevin [25] argue, full access to information and cultural content enables individuals with intellectual disabilities to affirm their rights, make autonomous choices, and exercise greater control over their present and future. The research aligns with and supports the core mission of AIPD, with whom every phase of the study was shared and discussed. The participants were not treated as passive subjects of inquiry, but as co-creators of insight, capable of contributing to the identification of museum access issues and envisioning more inclusive futures.

Although long-term ethnographic research involving people with Down Syndrome exists—especially in clinical [24], educational [26], or group-home [27] contexts—there remains a significant gap in research focusing on cultural participation and the lived experiences of adults with intellectual disabilities in museums. Involving people with DS in the identification and dismantling of barriers within museum settings serves a dual purpose: on one hand, it facilitates the design of more functional and responsive accessibility systems; on the other, it generates meaningful personal benefits in terms of well-being, agency, and social inclusion. To ensure that the research was both ethically sound and accountable to the disability community, the process included:

- Direct dialogue with participants and their support network;

- The use of accessible consent procedures;

- Comparison with established best practices from internationally recognised museums for their commitment to accessibility and inclusive design [17,18,19].

Inspiration was drawn from existing initiatives that demonstrate how people with intellectual disabilities can be directly involved in shaping museum content, such as:

- Co-creating exhibition labels using Easy-to-Read guidelines [28,29];

- The development of digital tools and augmented reality applications that facilitate and personalise access to cultural content [30,31,32].

These examples illustrate the ethical and epistemological importance of involving people with disabilities throughout the entire process of accessibility design: not as test users or recipients of finished outcomes, but as co-authors of their own cultural engagement.

3. Results

3.1. Navigating the Exhibits

During both museum visits, participants encountered a series of challenges related to orientation, spatial understanding, and wayfinding, which began well before their physical arrival at the venue. These challenges, often invisible to the average visitor, emerged at various stages of the museum journey: from digital access and telephone communication to physical arrival and navigation within the space.

3.1.1. Digital Access and Pre-Visit Planning

In both settings, the museum websites were identified as significant barriers to independent access. Despite their high visual impact and aesthetic quality, neither portal was designed with cognitive accessibility in mind. For the JMuseo, participants reported difficulties reading the content due to font style, font size, and visual layout. The website also contained inconsistencies between published information and that provided by museum staff, particularly regarding entrance fees and opening hours (which were subject to change depending on weather conditions).

The process of seeking information via phone presented further obstacles. When calling the museum’s listed number, participants were greeted with an automated voice menu that required them to choose among seven different museum locations. One participant, nominated by the group to request information, visibly struggled to interpret the options and appeared increasingly agitated. Confronted with confusion and a sense of inadequacy, they ultimately hung up the phone. Even when a menu option was selected, the call was redirected to a remote cooperative operator, not physically located at the museum and often unable to provide specific answers. These barriers contributed to a sense of disorientation and exclusion, especially given the participants’ need for reassurance and clarity in unfamiliar settings.

The website for the Museo Illusione tra Arte e Scienza posed similar difficulties. It served multiple museum branches, and only a careful selection of the correct city from the dropdown menu granted access to relevant logistical information such as opening hours and ticket costs. While the homepage featured playful imagery showcasing visitor interactions with installations, it did not offer cognitively accessible navigation paths or simplified textual content.

3.1.2. Arrival and Spatial Identification

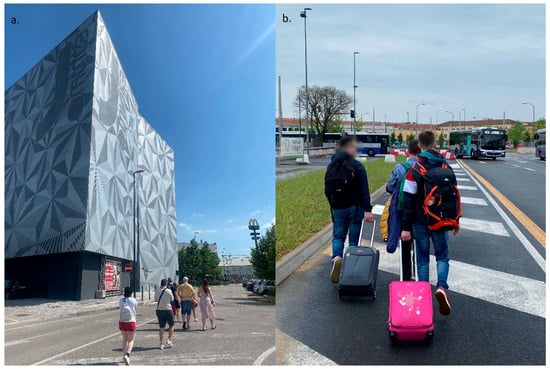

Participants also experienced uncertainty in identifying the museum buildings upon arrival. In both cases, printed images of the building exteriors and interiors, shown to the group in advance, helped create visual anchors and reduce anxiety during the journey. This strategy was particularly effective at the JMuseo (Figure 3a), where photographs of the exhibition spaces not only aided orientation but also supported the group’s informed choice of which exhibit to visit. The museum occupies four floors, with permanent natural history exhibitions on the first and second levels, and temporary exhibitions—including “Banksy & Friends: The Art of Rebellion”—on the third and fourth floors. Visiting the entire museum would have been too demanding for the group; hence, the interior visuals enabled them to make a targeted and autonomous decision.

Figure 3.

The arrival to the museums: (a). The majesty of the building makes JMuseo recognisable to visitors who have already seen it in photographs; (b). The second group caught public transport for reaching Museo Illusioni tra Arte e Scienza in the Verona city centre.

At JMuseo, the building entrance was visually discreet, described by participants as “a slit” within a monumental structure. Upon entering, visitors encountered a small entrance lobby with a ticket desk, opening onto a large atrium that spans five floors, illuminated by a central skylight. The hall, with its bright natural light and open vertical space, made a strong positive impression. It featured a bookshop and large dinosaur reproductions, which immediately caught the attention of the group. A spacious and well-lit elevator transported the participants to the third floor. However, once inside the exhibition, the absence of directional signage left the group without clear cues for navigating the space, relying instead on the sequential arrangement of rooms to infer a route.

At the Museo Illusione tra Arte e Scienza, the building was not easily recognisable despite prior exposure to exterior images. The group only perceived they had reached the correct location when they saw a promotional flag displayed outside the entrance. The museum was accessed via a single step, made accessible by a short, steep ramp, necessary to avoid blocking part of the adjacent street. Inside, the reception area featured dark walls and no natural light, which some participants found disorienting. The exhibition, located entirely on the ground floor, comprised a sequence of interconnected rooms, the layout of which was spatially intuitive, facilitating the group’s navigation of the experience. However, entry and exit occurred through the same point, and resting areas were scarce. Importantly, no quiet room was available in either venue, despite the sensory demands of the exhibitions.

3.1.3. Transportation and Real-Time Orientation

In the case of JMuseo, public transportation between the holiday residence and the museum was deemed impractical due to excessive travel time and distance from the nearest bus stop. Given the summer heat, the group opted to use the association’s van. Participants actively contributed to navigation using the Google Maps app on their smartphones, highlighting their growing digital literacy and desire to exercise spatial agency when environmental supports are appropriate.

3.2. Sensory Dimensions

In both museum visits, the sensory environment played a significant role in shaping participants’ engagement, emotional responses, and overall perception of the space. Although neither museum included formal multisensory elements (such as tactile displays, olfactory prompts, or interactive sound design), the visual dimension alone proved sufficiently rich to stimulate a wide range of sensory and emotional reactions among the participants.

3.2.1. Light and Visual Contrast

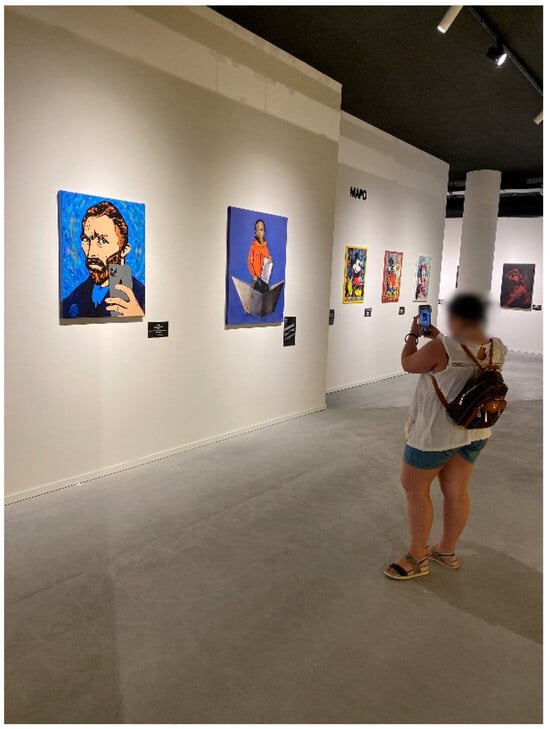

The layout of both exhibitions was characterised by high chromatic contrast: vivid, often provocative artworks were displayed against white walls (chosen to optimise brightness and reflect natural or artificial light) set in contrast to dark flooring and ceilings, typically grey or black (Figure 4). While no additional sensory modalities were activated through the exhibition design, this stark visual field proved engaging, eliciting immediate affective responses in several participants. Pre-visit interviews revealed a consistent sensitivity to colour and light temperature. Warm lighting was widely described as comforting, while red light was associated with alertness or a perceived need to pause. Cooler tones, such as blue or violet, were often noted as less stimulating or emotionally neutral. These responses appear to reflect both cognitive associations and physical reactions, with several participants noting that warm light causes less visual fatigue: a factor particularly relevant given the frequent presence of visual impairments among people with DS. Field observations confirmed these preliminary findings: artworks featuring warm colours (reds, oranges, yellows) consistently attracted participants’ attention, regardless of their thematic content. These works triggered spontaneous expressions of joy or enthusiasm, suggesting that colour had a more immediate emotional impact than the message of the artwork itself. This points to the primacy of embodied, sensory experience over abstract or symbolic interpretation, particularly in cognitively complex environments.

Figure 4.

The attention of a participant caught by vivid colours and thought-provoking artworks at JMuseo.

3.2.2. Sound and Affective Resonance

Although the museum environments themselves were not designed with sound as an active element, interviews conducted before and after the visits provided insight into the deeply personal and experiential nature of auditory perception. Participants were invited to reflect on various familiar sounds and the emotions they evoke. For example:

- The sound of ocean waves was universally described as positive, evoking joy, peace, or serenity;

- In contrast, the sound of a car passing on an empty street consistently elicited fear, perhaps due to its suddenness or associations with isolation;

- The sound of rain prompted mixed responses: for some it suggested sadness, for others calm or boredom;

- Similarly, birdsong was interpreted as pleasant and uplifting by most participants, yet provoked sadness or irritation in a small minority.

When asked to describe reactions to different musical genres:

- Upbeat, high-tempo music with strong rhythmic patterns (e.g., electronic or dance music) was met with enthusiasm and a desire to move or dance by the majority of participants. However, a few found such music agitating or overwhelming;

- Slow, melodic music (particularly romantic ballads) often triggered positive emotions, including feelings of being moved or emotionally touched. For a minority, yet, these songs provoked sadness, indicating the subjective and context-dependent nature of sensory triggers.

These findings suggest that auditory sensitivity among interviewees with DS is highly individualised, shaped by personal history, mood, and context. While no general rule can be applied across the board, the presence—or absence—of soundscapes within museum spaces should be approached with deliberate sensitivity, particularly given the lack of quiet rooms or acoustic accommodations in either of the visited exhibitions.

3.2.3. Texture and Tactility

Although tactile interaction was not explicitly incorporated into the exhibitions, the desire for touch-based exploration emerged spontaneously during the visits (Figure 5). Several participants reached toward objects or surfaces that were visually engaging, suggesting a sensorimotor curiosity that remained largely unsatisfied within the constraints of a “do not touch” museum environment. This observation reinforces findings from prior literature, which highlight the value of tactile engagement in strengthening the visitor-object relationship, especially for individuals with intellectual disabilities.

Figure 5.

Examples of interaction with the installations at Museo Illusioni tra Arte e Scienza through sight and touch.

3.3. Behavioural Responses and Emotional Engagement

The emotional responses elicited by the museum visits were predominantly positive, though nuanced by the differing sensory and thematic atmospheres of the two exhibitions. The visit to JMuseo generated feelings of serenity and wonder, while the Museo Illusione tra Arte e Scienza sparked joy, excitement, and physical dynamism. These differences reflect the diversity in exhibition content and setting, as well as the participants’ varied emotional receptivity. It is important to note that identifying and naming emotions is not a straightforward task, particularly for individuals with IDD. Individual cognitive profiles strongly influence self-awareness and access to the appropriate emotional vocabulary, and are often mediated by social support structures. Many participants demonstrated a clear awareness of their identity as people with Down Syndrome; however, their understanding of the social implications of their condition (especially regarding stigma, autonomy, and expectation) was often partial or indirect. Within the group, several commonalities emerged:

- Many participants showed signs of personal insecurity and low self-esteem, likely shaped by everyday social comparison, experiences of exclusion, or difficulty meeting perceived societal standards;

- These emotional vulnerabilities were not openly expressed, but became apparent through protective behavioural patterns observed during the museum visits.

When introducing themselves to museum staff and presenting their identity as people with disabilities, no tailored support or personalised welcome was provided. This lack of recognition, compounded by pre-existing self-doubt, triggered a range of compensatory behaviours. For some, this manifested as performing competence, confidence, or enthusiasm in ways that masked inner anxiety. Others adopted a more withdrawn posture, protecting themselves from potential emotional risks by disengaging or avoiding interaction. A shared feature across participants was a strong need for approval and reassurance—both from peers and from adult figures. In this regard, the presence of educators and volunteers proved invaluable. These figures not only facilitated emotional processing during and after the visit but also provided familiar relational anchors in an otherwise unfamiliar and potentially overwhelming environment. To further explore emotional reactions, a brief reflective questionnaire was distributed the day after each museum visit. The tool aimed to assess:

- The affective resonance of the experience;

- Memorability of specific artworks or moments;

- The desire to repeat or expand on the experience in the future.

The responses, though concise, were rich in significance. All participants clearly placed the experience in time and space, indicating a high level of presence and situational awareness. The majority reported feeling happy during the visit. One participant described the museum as “as exciting as being in an amusement park”. Two reported feeling creatively inspired, suggesting that the visit activated not only emotional but also imaginative responses. These positive emotions extended into the hours and days following the visit, even for those who noted physical or mental fatigue after the intense experience. Interestingly, while not everyone expressed a desire to repeat the same visit, nearly all participants said they would like to visit another museum in the future. Each participant was able to recall and describe specific elements that had struck them, and many shared photos of their favourite artworks in the group WhatsApp chat. These acts of sharing further reinforced the social and emotional impact of the museum experience, extending its reach beyond the moment of the visit.

One case deserves particular mention: a female participant in her twenties who took part in both phases of the study. After visiting JMuseo in 2024, she subsequently travelled with her family to New York, where she visited several museums, including the National September 11 Memorial & Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Her family reported a noticeable increase in engagement and emotional responsiveness, especially in exhibitions related to real historical events. She spoke with great emotion about the 9/11 Memorial, while offering only brief comments about the Metropolitan Museum. This participant also remembered and referenced the materials used during the first museum visit in 2024, which had been reintroduced to the group in 2025. She stated that she had carefully preserved the guidebook and appeared proud to share her familiarity with its content. While walking through the city of Verona during her second trip, she took on the role of an informal tour guide, explaining the history of the Arena with a sense of purpose and enthusiasm, drawing on the practice she had honed at home (Figure 6). This episode exemplifies how museum-based learning can enhance self-efficacy, memory consolidation, and social identity among people with intellectual disabilities—especially when scaffolded by repetition, autonomy, and emotional resonance.

Figure 6.

A participant who took part in both phases of the study, on the role of an informal tour guide explaining the history of the Arena in Verona.

3.4. Communication and Comprehension

The museum experiences revealed substantial variation in participants’ background, prior exposure to museums, and conceptual understanding of what a museum is or does. Given this heterogeneity, it was deemed essential to explore participants’ pre-existing representations and expectations prior to the visits, in order to support more informed and meaningful engagement during the exhibitions. In interviews conducted in the days leading up to the visits, only four out of twelve participants responded affirmatively and confidently when asked whether they had previously visited a museum or exhibition. Six participants had never entered a museum, and in two cases, memories of past visits only emerged gradually through examples and visual prompts. Participants’ conceptualisations of the museum varied significantly, often shaped by imagination, indirect experiences, or associations with other architectural spaces. For instance:

- One woman, who had never visited a museum but had toured Venetian villas, described a museum as “a place with lots of things to see, like paintings”;

- Another explained that museums contain “handmade works by people, artists… there are many kinds of museums: war museums, poetry museums”, adding that “sometimes entrance is free, sometimes you have to pay”, and expressing a preference for audio guides “to hear what it says”. This same participant (the only one who experienced both museum visits) also stressed the importance of rules in exhibition spaces, recalling signage about photography: “You can take photos only with phones, not with video cameras,” and noting the need to avoid touching artworks: “If you get too close to the painting and touch it, they’ll take you to prison!”.

Other participants expressed vague or metaphorical conceptions of the museum:

- A 34-year-old man, who had never visited a museum, imagined it as “a city” but could not elaborate further;

- Another participant confused the museum with a church, possibly drawing on notions of grandeur, reverence, and the presence of art. She described it as a place where “Jesus and Mary” are depicted and conserved;

- By contrast, one participant with extensive museum experience, including international travel, described museums as “places with beautiful things to see, like paintings”. He accurately named the Gypsotheca of Possagno and mentioned Antonio Canova as an artist he admired, and recalled a visit to a Banksy exhibition in the Netherlands, as well as castles in Bavaria and the Arena of Verona.

These differing frames of reference significantly influenced how participants approached and interpreted the exhibitions. During the visits, the group demonstrated strong engagement with individual artworks. However, it showed less interest in contextual or introductory panels (Figure 7), which were often too lengthy or complex to be understood independently. Where curiosity was piqued, some participants paused to read object labels—especially at JMuseo, where captions included the artist’s name, title, date, medium, dimensions, and origin. At the Museo Illusioni tra Arte e Scienza, labels served a more instructional function, guiding the viewer through interactive tasks to produce optical effects. In both cases, however, the most meaningful exchanges emerged not from reading but from dialogue with the educators and volunteers accompanying the group. These facilitators offered verbal mediation and personalised explanations, helping participants decode unfamiliar symbols, stay focused, and channel selective attention in cognitively demanding environments.

Figure 7.

Approaching the introductory panel to the “Banksy & Friends. The art of rebellion” exhibition: (a). The length and complexity of the text requires an intermediary to be understood; (b). A man from the group photographs the panel after the explanation given.

Participants’ preference for interpersonal communication over written text became especially apparent in interactions with digital installations. At the entrance to JMuseo, a television screen played an animated sequence by Banksy, originally produced as a dark parody of The Simpsons opening credits [33]. The absence of audio, combined with the grotesque imagery (e.g., dolls stuffed with cat fur, a unicorn exploited to produce DVDs [34]), soon left participants visibly confused or disengaged. Several turned to the nearby explanatory panel for clarity, but the small font size and dense text discouraged sustained attention. Most quickly abandoned the attempt and sought clarification from accompanying adults, who stepped in to bridge the comprehension gap. In another noteworthy moment, a participant asked for help in understanding the meaning of a work that had particularly caught her attention, “Stop Racism” by TVBoy. This prompted a short, accessible conversation about the meaning of racism in contemporary society, linking the artwork to broader questions of justice and identity.

At the Museo Illusioni tra Arte e Scienza, by contrast, the entrance screen was linked to an augmented reality camera, allowing visitors to see themselves projected on the screen in real-time. The installation produced immediate delight, sparking laughter, play, and prolonged interaction. In this case, the digital interface was intuitive, inclusive, and non-verbal, making it accessible regardless of reading ability or prior knowledge. Such moments illustrate the importance of responsive mediation, which does not reduce content to overly simplistic messages but instead invites critical reflection in ways that match the participant’s cognitive and emotional register.

3.5. Objects and Interactivity

Across both museum experiences, participants demonstrated a high level of interest, curiosity, and attention to detail. While comprehension of abstract themes varied across individuals, the emotional and social impact of the artworks—and the freedom to physically interact with certain installations—played a key role in shaping participants’ engagement. At JMuseo, the works on display in the “Banksy & Friends” exhibition sparked both individual reflection and group dialogue (Figure 8). Some participants responded primarily to aesthetic elements or visual familiarity, while others were drawn into deeper thematic discussions. One participant, upon recognising the footballers Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo in TvBoy’s “Love is Blind” (an image depicting the two athletes kissing) spontaneously drew the group’s attention to the artwork. His enthusiasm opened a space for collective conversation about homosexuality, offering an opportunity to surface opinions, ask questions, and listen to one another. While the artwork itself was provocative, it was the act of recognition and emotional resonance that activated the social learning moment.

Figure 8.

Examples of interaction with the artworks at JMuseo: (a). Imitation of what they observe, (b). Search for hidden representations, (c). Exchange and comparison of emotions.

In another case, a 25-year-old woman was struck by the bold blue of the burqa depicted in Laika’s “Zapatos Rojos—Save Afghan Women”, which prompted a collective discussion about women’s rights, cultural oppression, and the violation of human dignity. These moments, though often brief, highlight the potential of visual art to serve as an accessible entry point into complex issues, even for individuals with limited formal education in art or politics. A third participant initiated peer engagement in front of “Hiding in the City” by Liu Bolin, a series that explores the individual’s erasure within the public sphere. In this case, curiosity was sparked not only by the content but by the visual technique—Liu’s body camouflaged within urban backgrounds—which led to spontaneous group interpretation and speculation about identity, invisibility, and the power of images.

Participant responses were not limited to verbal exchanges; they also included nonverbal cues. Observing how attention flowed within the group made it possible to track micro-interactions and shifting social dynamics. Such interactions reflected both emotional expressiveness and divergent perspectives, revealing the importance of open-ended facilitation and the value of accommodating aesthetic disagreement and individual interpretation. Participants were encouraged not only to observe, but to claim authorship of their reactions, sometimes playfully, sometimes viscerally.

4. Discussion

The study offers a valuable opportunity to reflect on how museum visits can be meaningfully redesigned to be more inclusive of people with intellectual disabilities, specifically, individuals with Down syndrome. By examining the entire visitor experience, from the planning phase to the lingering emotional impact after the visit, the research highlights several critical touchpoints for improving accessibility, dignity, and engagement.

One of the study’s key findings concerns the emotional and psychological vulnerabilities expressed by participants: particularly low self-esteem and a pronounced sense of personal inadequacy. These dynamics, while more visible among people with intellectual disabilities due to their heightened exposure to structural and interpersonal barriers, are not exclusive to this population. Indeed, the need for self-affirmation, the tendency to exaggerate or distort one’s self-image to seek approval, and the internalisation of social judgment are common human responses. This insight reframes accessibility not as a niche concern, but as a universal design issue: practices that benefit neurodivergent or intellectually disabled individuals are likely to enhance the experience for all.

A museum visit begins well before the visitor crosses the threshold. The availability of clear, accurate, and user-friendly information online is crucial. Contrary to outdated assumptions, many individuals with intellectual disabilities—either independently or with caregiver support—are capable of conducting online research to plan their visits. The more intuitive and accessible the digital interface, the greater the sense of autonomy and self-efficacy a visitor can experience even before arriving. The shift toward online accessibility was accelerated by the implications of COVID-19 pandemic, which encouraged institutions to digitalise collections and explore multimedia engagement. Social media platforms now offer a powerful tool to spark curiosity, offer previews, and motivate visits—provided the content is clear, inviting, and inclusive.

The study also revealed difficulties encountered in phone-based communication, especially when automated systems or untrained staff were involved. Participants often felt frustrated or misunderstood, reinforcing feelings of exclusion. As a result, in-person visits to museum ticket desks were perceived as more effective for gathering information and familiarising oneself with the space. This form of embodied pre-visit exploration can significantly lower anxiety and boost confidence.

Consequently, the front desk is the museum’s first point of contact, both physically and emotionally. A warm, informed, and respectful welcome can shape the entire trajectory of a visitor’s experience. Nevertheless, staff attitudes toward people with Down syndrome are often marked by contradictory social scripts: on one hand, infantilising care and condescension (“special people”); on the other, avoidance rooted in discomfort or stigma (“they are different”). These reactions can result in both overcompensation and emotional distancing. Instead, museum staff must be trained to offer transparent communication, attentiveness to individual needs, and the ability to build trust-based relationships. Even subtle architectural features (such as glass or plastic dividers at ticket counters) can become physical and acoustic barriers, particularly for individuals with auditory processing challenges. Consideration should be given to acoustics, lighting reflections, and visual accessibility when designing or modifying such interfaces.

Visitors with intellectual disabilities often experience mental fatigue, reduced working memory, and difficulty shifting focus. Therefore, offering a curated selection of artworks—either recommended in advance or accompanied by clear visual guides—can help structure the visit without imposing limitations. Tools that support autonomy while offering gentle guidance—such as simplified print materials (e.g., Easy-to-Read formats or Augmentative and Alternative Communication systems), audioguides, or trained facilitators—contribute to a sense of being welcomed, capable, and respected.

Moreover, sensory considerations emerged as key. Background music, for instance, may trigger positive emotions, but it must be carefully selected. Sudden or low-frequency sounds may evoke fear, while nature sounds or calming melodies (though often used in therapeutic settings) can also be perceived as dull or melancholic, depending on personal associations. Lighting and warm colours were generally appreciated, but participants demonstrated selective attention that could rapidly shift from attraction to aversion. These findings call for personalised and adaptable pathways, rather than static solutions.

The presence of gallery attendants can significantly enhance the experience. Rather than serving merely as rule enforcers, trained attendants can model appropriate behaviour, explain rules when needed, and offer reassurance. This is especially important when impulsive or non-normative behaviour (such as touching an artwork) may arise not out of disregard, but from different sensory or cognitive processing. Responsive and respectful interactions help establish a sense of belonging and increase the likelihood of return visits.

Wayfinding signage and clear orientation tools help visitors navigate the space independently, reducing disorientation and enabling a sense of spatial agency. Seating areas distributed across the galleries offer not only physical relief but also the chance to pause, reflect, and observe without pressure. As for the interpretation panels, excessive text, overly specialised language, or dense layouts can alienate rather than invite. Instead, incorporating visuals, shared references, minimal text, and layered comprehension strategies (e.g., QR codes linking to videos or alternate formats) can bridge the gap between expertise and accessibility. Finally, fostering a sense of ownership and voice is critical. Inviting visitors to leave a comment, impression, or suggestion at the end of their visit transforms them from passive consumers to co-creators of the museum space. This not only enhances their own experience but also improves the institution’s capacity to grow through inclusion.

5. Conclusions

Over the past two decades, museums have increasingly recognised the need to open their doors to a broader and more diverse public: one that includes individuals with varying degrees of vulnerability and differing needs. This shift necessitates the dismantling of long-standing barriers that have historically limited access, understanding, and participation. To genuinely conceive of the museum as a space for discovery, learning, and dialogue for all requires a holistic, insider-informed approach. Ethnographic engagement with the people most affected by exclusion proves essential in identifying obstacles that may remain invisible to those who do not encounter them. Indeed, what benefits one visitor may hinder another. In this study, many access barriers were made visible only through the direct involvement of people with IDD—particularly those with Down syndrome—as co-authors of the study. Through participant observation, it became possible to build trust, enter the community, and observe the subtle yet critical dynamics of behaviour, communication, and engagement that escape conventional evaluative methods. The reciprocal relationship developed with participants fostered a growing sense of shared purpose and empowered individuals to contribute meaningfully to the research from the outset.

This model of collaboration invites us to reconsider the role of people with IDD, not merely as passive recipients of inclusion, but as active partners in shaping inclusive cultural environments. The creation of focus groups and advisory panels involving such populations in the planning of exhibitions, events, and museum services would enable institutions to address barriers from within. This dialogue recognises forms of knowledge and lived experience that are often excluded from traditional curatorial or design frameworks. Moreover, this reorientation holds broader social and pedagogical potential. Learning how to communicate with patience, listen attentively, observe non-verbal cues, and respond flexibly to diverse communicative styles should not be seen as an accommodation, but as a crucial competency for museum professionals and staff. It is through these skills that museums can become places of genuine welcome and engagement, not only for people with IDD, but for all visitors.

To the threefold question—“Can the museum be a place where we discuss intellectual disability, from the perspective of intellectual disability, and with people with intellectual disabilities?”—this analysis offers an affirmative response. Including this audience among those to whom exhibitions are addressed allows the museum to become a tool for their cultural and personal development. Their involvement as staff—such as gallery attendants or members of working groups—should be actively explored, always in relation to the severity of individual symptoms and strengths. Such inclusion could help reveal barriers that even the most well-intentioned and competent museum leadership may overlook. Likewise, public-facing initiatives (such as training for museum professionals, inclusive programming, and clearly visible pathways for engagement) can indirectly raise awareness among the general public about the lived experiences of individuals with IDD.

This study was shaped by the specificity of its ethnographic context, the characteristics of the participating group, and the two museums involved. As such, its findings are not intended to be generalised without caution, due to the small number of people interviewed and the fact that they were relatively familiar with group activities. This research primarily focused on the experiential and relational aspects of the museum visit. Further investigations could integrate design ethnography, sensorial analysis, or co-design methodologies to develop new prototypes of accessible exhibition strategies and to evaluate their impact over time. Longitudinal studies could also help understand how repeated or sustained access to cultural spaces might influence self-esteem, social engagement, or educational outcomes. Ultimately, the ambition of this work is to contribute to an ethics of accessibility that sees inclusion not as an act of charity, but as a shared, creative, and transformative endeavour.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.C.R. and E.T.; methodology, G.C.R.; validation, G.C.R.; formal analysis, E.T.; investigation, E.T.; data curation, G.C.R. and E.T.; writing—original draft preparation, G.C.R. and E.T.; writing—review and editing, G.C.R. and E.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the local branch of “Marca Trevigiana” from “Associazione Italiana Persone Down”, which provides safeguarding for those involved in the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the qualitative approach of this research, no quantitative dataset has been created. The visit booklets and ethnographic field diary remain unpublished at present.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank AIPD Marca Trevigiana, especially the Board of Directors, for accepting the proposal and providing the time, knowledge and resources for its implementation. Thanks to the people with Down syndrome who chose to participate in this project and without whom this work would not have seen the light of day. Thanks to Margherita Svaizer, part of the team of educators at AIPD Marca Trevigiana, for sharing her skills, observations and opinions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Soares, B.B.; Bonilla-Merchav, L. The Museum Definition Handbook: Words Inspiring Action; ICOM: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, C.J.; Kreps, C. (Eds.) Pragmatic Imagination and the New Museum Anthropology, 1st ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Message, K.; Witcomb, A. Museum Theory: An Expanded Field. In Museum Theory: An Expanded Field; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA; Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 35–63. [Google Scholar]

- Sandell, R. Museums, Prejudice and the Reframing of Difference; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, J.; Sandell, R.; Garland-Thomson, R. Re-Presenting Disability: Activism and Agency in the Museum; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sandell, R. Social inclusion, the museum and the dynamics of sectoral change. Mus. Soc. 2003, 1, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. ICD-11: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th Revision; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://icd.who.int/ (accessed on 2 February 2026).

- Schalock, R.L.; Luckasson, R. Intellectual disability, developmental disabilities, and the field of intellectual and developmental disabilities. In APA Handbook of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: Foundations; Glidden, L.M., Abbeduto, L., McIntyre, L.L., Tassé, M.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; pp. 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Dermitzaki, I.; Stavroussi, P.; Bandi, M.; Nisiotou, I. Investigating ongoing strategic behaviour of students with mildmental retardation: Implementation and relations to performance in a problem-solving situation. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 2008, 21, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.R.; Apple, R.; Kanungo, S.; Akkal, A. Intellectual disability: Definitions, evaluation and principles of treatment. Pediatr. Med. 2018, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andjelkovic, K.; Cantusci, M.; D’Anzica, C.; De Propris, B.; Scarpati, D.; Zupanek, B. Oltre. Laboratori di Archeologia Sperimentale e Disabilità; Edizioni Espera: Monte Compatri, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Got, I.L.; Cheng, S. The Effects of Art Facilitation on the Social Functioning of People With Developmental Disability. Art Ther. 2008, 25, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanareff, R.L. Utilizing Group Art Therapy to Enhance the Social Skills of Children with Syndrome. ProQuest Digital Dissertations. Master’s Thesis, Ursuline College, Pepper Pike, OH, USA, 2002. UMI No. 1408034. [Google Scholar]

- Luftig, R.L. Teaching the Mentally Retarded Student: Curriculum, Methods, and Strategies; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S.; Camic, P.M.; Springham, N. New roles for art galleries: Art-viewing as a community intervention for family carers of people with mental health problems. Arts Health Int. J. Res. Policy Pract. 2011, 32, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, S. The White House Visitor Center: A case study in inclusive exhibition design. Exhibitionist 2015, 34, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Braden, C. Welcoming All Visitors: Museums, Accessibility, and Visitors with Disabilities. In Working Papers in Museum Studies; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2016; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- McMillen, R. Museum disability access: Social inclusion opportunities through innovative new media practices. Pac. J. 2015, 10, 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ciaccheri, M.C.; Fornasari, F. Il museo per tutti. Buone pratiche di accessibilità. In I Libri di AccaParlante; Edizioni La Meridiana: Molfetta, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Steinfeld, E. Advancing Universal Design. In The State of the Science in Universal Design: Emerging Research and Developments; Maisel, J.L., Ed.; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2010; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, M. Shifting the conversation: Improving access with Universal Design. Exhibitionist 2015, 34, 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, S.; Kuper, A.; Hodges, B. Qualitative Research Methodologies: Ethnography. Br. Med. J. 2008, 337, a1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohler, A. Assuming Capacity: Ethical Participatory Research with Adolescents and Adults with Down Syndrome. In Research Involving Participants with Cognitive Disability and Difference: Ethics, Autonomy, Inclusion, and Innovation; Cascio, M.A., Racine, E., Eds.; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glimartin, A.; Slevin, E. Being a member of a self-advocacy group: Experiences of intellectually disabled people. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2010, 38, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliewer, C. Citizenship in the Literate Community: An Ethnography of Children with down Syndrome and the Written Word. Except. Child. 1998, 64, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birt, L.; Charlesworth, G.; Moniz-Cook, E.; Leung, P.; Higgs, P.; Orrell, M.; Poland, F. “The Dynamic Nature of Being a Person”: An Ethnographic Study of People Living With Dementia in Their Communities. Gerontologist 2023, 63, 1320–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shogren, K.A.; Caldarelli, A.; Del Bianco, N.; D’Angelo, I.; Giaconi, C. Co designing inclusive museum itineraries with people with disabilities: A case study from self-determination. Educ. Sci. Soc. 2022, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrogiuseppe, M.; Span, S.; Bortolotti, E. Accessibility to textual resources for people with Intellectual Disabilities within cultural spaces. Form@Re Open J. per la Form. Rete 2022, 22, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, S.L.; Ferrari, V.; Mastrogiuseppe, M.; Span, S.; Landoni, M. ACCESS+: Designing a museum application for people with intellectual disabilities. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs, Proceedings of the 18th International Conference, ICCHP-AAATE, Lecco, Italy, 11–15 July 2022, Part II; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Guedes, S.L.; Zanardi, I.; Mastrogiuseppe, M.; Span, S.; Landoni, M. C-designing a Museum Application with People with Intellectual Disabilities: Findings and Accessible Redesign. In Proceedings of the ECCE’ 23, Swamsea, UK, 19–22 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mastrogiuseppe, M.; Guedes, S.L.; Landoni, M.; Span, S.; Bortolotti, E. Technology Use and Familiarity as an indicator of its adoption in museum by people with intellectual disabilities. In Transforming our World through Universal Design for Human Development; Garofolo, I., Ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 400–407. [Google Scholar]

- The Simpsons Intro. Storyboard for The Simpsons Intro “Couch Gag”, Banksy. Blog. Available online: https://www.banksy.blog/explore/2010/simpsons (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Fink, M. The Simpsons: A Cultural History; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2019; p. 172. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.