Conflict Management Strategies as Moderators of Burnout in the Context of Emotional Labor

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Emotional Labor and Burnout

1.2. Conflict Management Strategies and Burnout

1.3. The Moderating Role of Conflict Management Strategies

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Data Collection Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. Sociodemographic Questionnaire

2.3.2. Oldenburg Burnout Inventory

2.3.3. Conflict Management Strategies Assessment Scale (ROCI-II)

2.3.4. Emotional Labor Scale (ELS)

2.4. Data Analysis Procedures

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

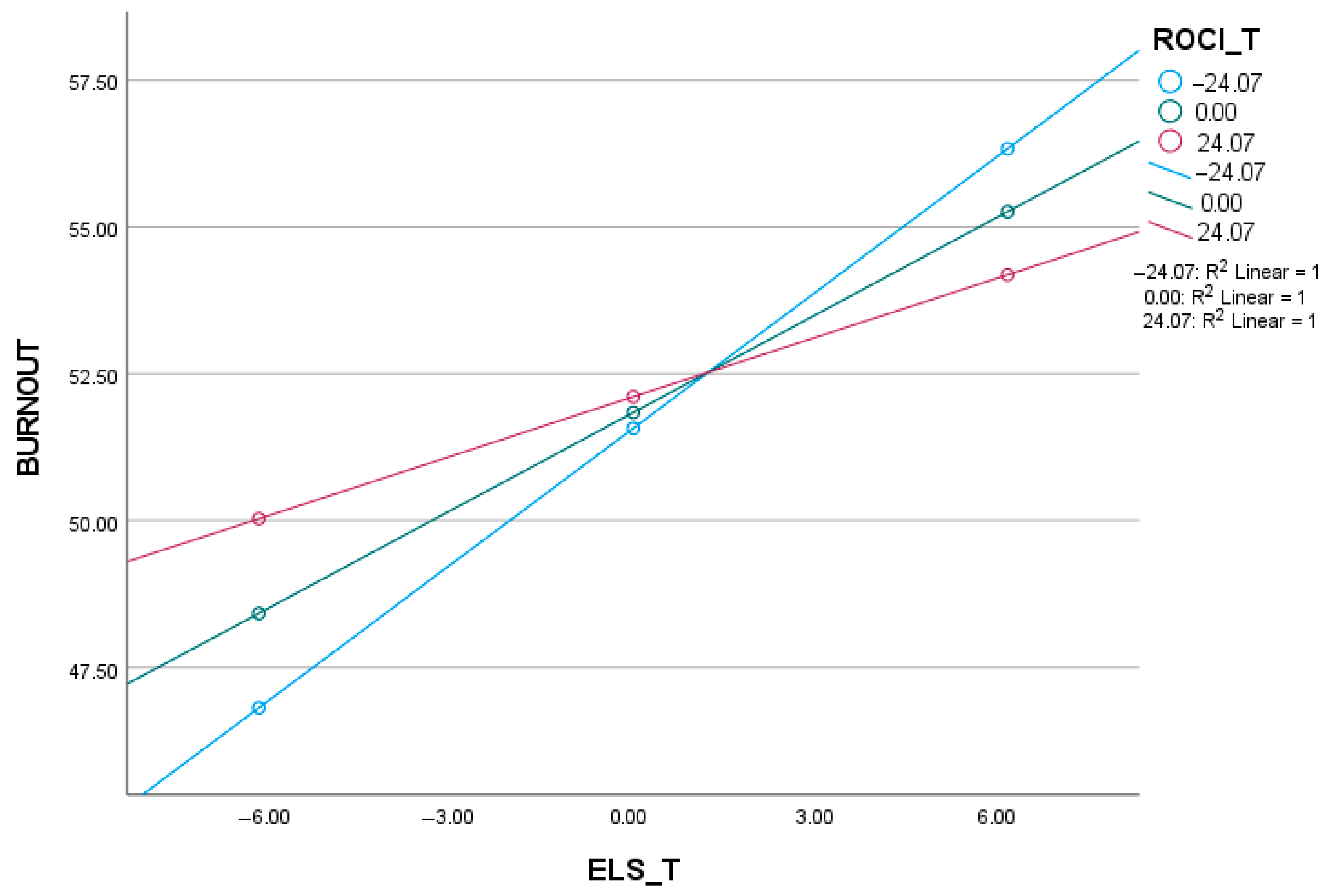

3.2. Test of Hypotheses

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cao, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, S. How CEOs’ inclusive leadership fuels employees’ well-being: A three-level model. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 34, 2305–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claes, S.; Vandepitte, S.; Clays, E.; Annemans, L. How job demands and job resources contribute to our overall subjective well-being. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1220263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.; Shamroukh, S. Predictive modeling of burnout based on organizational culture perceptions among health systems employees: A comparative study using correlation, decision tree, and Bayesian analyses. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C. Job burnout: New directions in research and intervention. Am. Psychol. Soc. 2003, 2, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.; Demerouti, E. The construct validity of an alternative measure of burnout: Investigating the English translation of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory. Work Stress 2005, 19, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization [WHO]. Burn-Out an “Occupational Phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. 28 May 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Aziz, S.; Widis, A.; Wuensch, K. The association between emotional labor and burnout: The moderating role of psychological capital. Occup. Health Sci. 2018, 2, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeung, D.Y.; Kim, C.; Chang, S.J. Emotional labor and burnout: A review of the literature. Yonsei Med. J. 2018, 59, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kızılkaya, S. The mediating role of job burnout in the effect of conflict management on work stress in nurses. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 20275–20285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michinov, E. The moderating role of emotional intelligence on the relationship between conflict management styles and burnout among firefighters. Saf. Health Work 2022, 13, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joffe, A.D.; Peters, L. The association between emotional labor, affective symptoms, and burnout in Australian psychologists. Aust. Psychol. 2024, 59, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, A. The Presentation of Emotion; Sage Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer, G.; Shuster, S.M. Emotional labor, teaching and burnout: Investigating complex relationships. Educ. Res. 2020, 62, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rughoobur-Seetah, S. An assessment of the impact of emotional labor and burnout on the employees’ work performance. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2024, 32, 1264–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S. Emotional labor strategies, stress, and burnout among hospital nurses: A path analysis. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2020, 52, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikolajczak, M.; Menil, C.; Luminet, O. Explaining the protective effect of trait emotional intelligence regarding occupational stress: Exploration of emotional labor processes. J. Res. Personal. 2007, 41, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, N.M.; Zainuddin, M. Emotional labor and burnout among female teachers: Work–family conflict as mediator. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 14, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, H.A.; Susanto, E. Conflict management styles, emotional intelligence, and job performance in public organisations. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2010, 21, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamdan, Z.; Adnan Al-Ta’amneh, I.; Rayan, A.; Bawadi, H. The impact of emotional intelligence on conflict management styles used by Jordanian nurse managers. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.X.; Xu, X.; Phillips, P. Emotional intelligence and conflict management styles. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2019, 27, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariou, A.; Koutsimani, P.; Montgomery, A.; Lainidi, O. Emotional labor and burnout among teachers: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brotheridge, C.M.; Lee, R.T. Development and validation of the emotional labor scale. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2003, 76, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, J.S.C.; Bendassolli, P.F.; Gondim, S.M.G. Trabalho emocional e burnout: Um estudo com policiais militares [Emotional labor and burnout: A study with the military police]. Av. En Psicol. Latinoam. 2017, 35, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celiker, N.; Ustunel, M.F.; Guzeller, C.O. The relationship between emotional labor and burnout: A meta-analysis. Anatolia 2019, 30, 328–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülsheger, U.R.; Schewe, A.F. On the costs and benefits of emotional labor: A meta-analysis of three decades of research. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammeyer-Mueller, J.D.; Rubenstein, A.L.; Long, D.M.; Odio, M.A.; Buckman, B.R.; Zhang, Y.; Halvorsen-Ganepola, M.D.K. A meta-analytic structural model of dispositonal affectivity and emotional labor. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 66, 47–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynie, J.J.; Fuller, B.; Martin, C.L.; Story, J. Overall justice and emotion regulation: Combining surface acting with unfairness talk for greater satisfaction and less exhaustion. Manag. Decis. 2023, 61, 1517–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Romero, A.; Martinez-Iñigo, D. Validation of an attributional and distributive justice mediational model on the effects of surface acting on emotional exhaustion: An experimental study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeung, D. Effect of Emotional Labor on Burnout Among Korean Firefighters; Korean Association of Health and Medical Sociology: Busan, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbey, D.O.; Gelmez, E. A Research to Determine the Relationship Between Emotional Labor and Burnout. In Business Challenges in the Changing Economic Landscape—Vol. 2: Proceedings of the 14th Eurasia Business and Economics Society Conference; Springer International Publishing: Barcelona, Spain, 2016; pp. 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çağlıyan, V.; Fındık, M.; Doğanalp, B. A consideration on emotional labor, burnout syndrome and job performance: The case of health institutions. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 4, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zaghini, F.; Biagioli, V.; Proietti, M.; Badolamenti, S.; Fiorini, J.; Sili, A. The role of occupational stress in the association between emotional labor and burnout in nurses: A cross-sectional study. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2020, 54, 151277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, Y.; Shin, S.Y. Moderating Effects of resilience on the relationship between emotional labor and burnout in care workers. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2018, 44, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, J.; Singh, M. Donning the mask: Effects of emotional labor strategies on burnout and job satisfaction in community healthcare. Health Policy Plan. 2016, 31, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotheridge, C.M.; Grandey, A.A. Emotional labor and burnout: Comparing two perspectives of “people work”. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 60, 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, A.; Marzi, G.; Maley, J.; Silic, M. Ten years of conflict management research 2007-2017: An update on themes, concepts and relationships. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2019, 30, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winardi, M.A.; Prentice, C.; Weaven, S. Systematic literature review on emotional intelligence and conflict management. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2022, 32, 372–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, M.A. A measure of styles of handling interpersonal conflict. Acad. Manag. J. 1983, 26, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashisht, R.; Singh, K.; Sharma, S. Emotional intelligence and its relationship with conflict management and occupational stress: A meta-analysis. Pac. Bus. Rev. Int. 2018, 11, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano-Vázquez, I.; Cajachagua Castro, M.; Morales-García, W.C. Emotional intelligence as a predictor of job satisfaction: The mediating role of conflict management in nurses. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1249020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlaerth, A.; Ensari, N.; Christian, J. A meta-analytical review of the relationship between emotional intelligence and leaders’ constructive conflict management. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2013, 16, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutner, P.; Riemenschneider, C. The impact of emotional labor and conflict-management style on work exhaustion of information technology professionals. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2015, 36, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safi, M.H.; Mohamadi, F.; Kolahi, A.A. The Relationship between Job Satisfaction with Burnout and Conflict Management Styles in Employees. Community Health 2015, 2, 266–274. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, H. The Moderating Effect of The Demographic Variables on the Relationship between Burnout Syndrome and the Management of Conflicts. Yönetim Bilim. Derg. 2022, 20, 497–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, A.S.; Omar, M.K.; Mohd, I.H. Psychological Capital, Emotional Labor, and Burnout Among Malaysian Workers. Evolutionary Studies in Imaginative Culture. Evol. Stud. Imaginative Cult. 2024, 8, 292–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazliyar, M.; Borghei, Z. Determination of the relationship between job burnout and conflict management styles in employees of health administration and assessment of medical documents office of Golestan Province branch of social security organization of Islamic Republic of Iran. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.P.; Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.A.D.B.; Carlotto, M.S.; Marôco, J. Oldenburg Burnout Inventory-student version: Cultural adaptation and validation into Portuguese. Psicol. Reflexão Crítica 2012, 25, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimas, I.C.D. (Re)pensar o Conflito Intragrupal: Níveis de Desenvolvimento e Eficácia [(Re)Thinking Intragroup Conflict: Levels of Development and Effectiveness]. Doctoral Dissertation, Faculdade de Psicologia e de Ciências da Educação, Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal, 2007. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10316/7484 (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Castanheira, F.; Chambel, M.J. Emotion work, psychological contract, and their relationship with burnout. In New Research Trends in Effectiveness, Health, and Work: A Criteos Scientific and Professional Account; Morin, E., Ramalho, N., Silva, C., Eds.; Edições Sílabo: Lisboa, Portugal, 2009; pp. 101–120. [Google Scholar]

- Marôco, J. Análise Estatística com o SPSS Statistics [Statistical Analysis with SPSS Statistics], 7th ed.; ReportNumber; Edições Nosso Conhecimento: Pêro Pinheiro, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach (2ª); Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, D.; Ferguson, M.; Hunter, E.; Whitten, D. Abusive supervision and work–family conflict: The path through emotional labor and burnout. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, C. Emotional labor and its consequences: The moderating effect of emotional intelligence. In Individual Sources, Dynamics, and Expressions of Emotion; Emerald Group Publishing Ltd.: Leeds, UK, 2013; pp. 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Min. | Max. | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELS Total | 9 | 45 | 27.85 | 6.16 | 0.36 | 1.36 |

| ELS—emotional demands at work | 3 | 15 | 10.22 | 2.59 | 0.01 | −0.22 |

| ELS—emotional regulation strategies | 6 | 30 | 17.62 | 4.89 | 0.10 | 0.72 |

| ELS—surface acting | 3 | 15 | 8.18 | 3.15 | 0.10 | −0.52 |

| ELS—deep acting | 3 | 15 | 9.44 | 2.93 | −0.09 | −0.05 |

| ROCI Total | 29 | 196 | 123.11 | 24.30 | −0.95 | 4.60 |

| ROCI—integrating/collaborating | 7 | 49 | 38.24 | 8.04 | −1.46 | 3.47 |

| ROCI—obliging/accommodating | 7 | 42 | 25.22 | 6.33 | −0.31 | 0.81 |

| ROCI—dominating/competing | 5 | 35 | 16.84 | 6.34 | 0.40 | 0.32 |

| ROCI—avoidance | 6 | 42 | 24.55 | 7.51 | −0.09 | 0.12 |

| ROCI—compromising | 4 | 28 | 18.35 | 4.65 | −0.72 | 1.38 |

| OLBI Total | 16 | 80 | 51.56 | 8.11 | 0.46 | 4.72 |

| OLBI—disengagement | 8 | 40 | 25.77 | 4.43 | 0.56 | 3.52 |

| OLBI—exhaustion | 8 | 40 | 25.78 | 4.80 | 0.06 | 1.83 |

| 1. | 2. | |

|---|---|---|

| ELS Total | ||

| ROCI Total | 0.04 | |

| OLBI Total | 0.49 ** | −0.16 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodrigues, A.; Francisco, M.; Oliveira, Í.M.; Leite, Â.; Lopes, S. Conflict Management Strategies as Moderators of Burnout in the Context of Emotional Labor. Societies 2025, 15, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15030063

Rodrigues A, Francisco M, Oliveira ÍM, Leite Â, Lopes S. Conflict Management Strategies as Moderators of Burnout in the Context of Emotional Labor. Societies. 2025; 15(3):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15030063

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigues, Anabela, Micaela Francisco, Íris M. Oliveira, Ângela Leite, and Sílvia Lopes. 2025. "Conflict Management Strategies as Moderators of Burnout in the Context of Emotional Labor" Societies 15, no. 3: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15030063

APA StyleRodrigues, A., Francisco, M., Oliveira, Í. M., Leite, Â., & Lopes, S. (2025). Conflict Management Strategies as Moderators of Burnout in the Context of Emotional Labor. Societies, 15(3), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15030063