Abstract

This exploratory study examines how discursive design—using provocative, speculative artifacts to spark reflection and discussion—might expand public health experts’ problematization of approaches to tailoring and targeting interventions. Cultural tailoring and targeting (CTT) refers to adapting interventions for specific sociocultural populations. Because LGBTQ+ communities experience disproportionately high rates of tobacco use, this study applies discursive intervention concepts within this context to explore how they might help experts critically engage with CTT strategies for reaching LGBTQ+ populations more effectively. To investigate this, two pairs of discursive intervention concepts were designed and presented to three focus groups of public health experts. Each pair juxtaposed a conventional intervention approach with a more provocative, unfamiliar one—for example, deepfake-driven behavior disruption. The goal was to document the type of conversation discursive design could stimulate around CTT considerations and generate insights relevant to the value of design methodologies to foster new ways to problematize public health matters. Findings indicate that the concepts prompted critical conversations about CTT, although the depth and focus of engagement varied. Those with greater expertise in LGBTQ+ issues engaged more with CTT mechanisms and implications, while others focused on implementation and feasibility concerns—essential to intervention development but outside the study’s focus. These patterns highlight who should be included in such efforts and how they should be engaged from a facilitation perspective, raising important considerations for methodological refinements and future research. Overall, this initial exploration aims to uncover the potential of discursive design to deepen understanding of CTT interventions and inform more responsive, innovative approaches to addressing tobacco use among priority populations.

1. Introduction

The tobacco industry has a long history of leveraging design to entice consumers—from the iconic advertising featuring the Marlboro Men by Leo Burnett and the cigarette tap-tap packaging to fashionable vaping devices [1,2]. In contrast, the full potential of design within public health remains largely untapped, despite growing recognition of its value [3]. Public health guidance and innovation frameworks increasingly recommend involving designers and design thinking in intervention development [4]. However, these approaches tend to position design primarily as a tool for generating or refining solutions after problems are already defined and when ideation, prototyping, or implementation is underway. This orientation overlooks design’s capacity to contribute earlier in the process—when foundational understandings of problems, assumptions, and strategic directions begin to take shape.

We propose that this tendency reflects not a limitation in designers’ abilities but a structural gap in how public health conceptualizes—and therefore operationalizes—the role of design. Design holds an original capacity to problematize and to nurture a particular moral phenomenology [5,6]. Discursive, speculative, and critical design scholarship demonstrates designers’ ability to reframe problems and imaginatively explore alternative futures [7,8,9]. Yet, as noted above, these capacities remain underutilized in public health, especially during early problem framing, when assumptions and value commitments take shape. Because our understanding of a problem—and the assumptions and values that guide how we address it—profoundly shapes intervention outcomes, it is essential that design contribute its strengths in surfacing and interrogating these dimensions.

Why, then, does this gap between public health and design persist? Scholars have offered several explanations. Bazzano and Martin [3], for example, argue that the divide stems partly from how the two fields conceptualize and conduct research. Public health often relies on linear, hypothesis-driven processes with fixed problems and predefined methods. The authors explain that, by contrast, design research is iterative, adaptive, and more tolerant of ambiguity. As such, these characteristics can clash with normative expectations of evidence-based research. Such misalignments may help explain why design’s problematizing capacities have not been widely adopted in formative public health work.

For these reasons, there is a need to demonstrate how discursive design can contribute to problematization and to articulate more clearly how public health and design might collaborate. Doing so can help bridge the gap and create a more direct pathway for integrating design’s strengths into formative intervention development.

Thus, as part of a larger project addressing smoking cessation among LGBTQ+ populations—a group with nearly double the smoking prevalence of the general population [10]—this research explores how designers can surface new issues, problems, opportunities, and strategies for culturally tailored and targeted public health interventions. In this paper, we use the terms cultural tailoring and targeting (collectively referred to at times as CTT) to refer to the systematic modification of evidence-based interventions to align them with the psychosocial experiences, norms, beliefs, and actions of specific populations [11]. Indeed, while evidence-based interventions have made strides in reducing smoking prevalence in the general population, their success in attenuating tobacco disparities is limited. Therefore, further research remains essential to broaden the understanding of issues at stake and explore alternative methods of intervention [12].

To explore how discursive design might contribute to this early-stage work, we convened focus groups with professionals who are typically involved in shaping tobacco prevention and control interventions or LGBTQ+-focused programs. Participants included academics and researchers specializing in health behavior and health promotion, epidemiology, and environmental health, as well as practitioners from allied fields that frequently collaborate with public health on intervention development, including social work, clinical psychology, and chemistry. Several participants also had experience working directly with LGBTQ+ populations or implementing culturally tailored interventions. These experts were intentionally selected because their disciplinary orientations and applied experience positioned them to engage with the speculative design concepts meaningfully and to reflect on their implications for culturally tailored and targeted intervention strategies.

Drawing on methodologies detailed by Auger [7], Tharp & Tharp [8,9], and Kinch et al. [13] we envisioned a series of uncanny, radical, and preposterous culturally relevant smoking cessation interventions to provoke critical reflection and foster a space for nuanced conversation around public health intervention scenarios.

This paper presents four speculative design concepts, summarizes the feedback derived from three focus groups held with public health and adjacent experts, and discusses how discursive design might expand the problematization of culturally tailored and targeted smoking cessation interventions for LGBTQ+ populations. Our research highlights the potential contributions of design to public health practice and expands the conversation on how innovative, culturally sensitive strategies can support the development of effective strategies to reduce health disparities.

2. Background

2.1. Persistent Challenges in Public Health

Despite ongoing efforts to address public health challenges, many problems persist, with tobacco cessation standing out as a particularly wicked problem [14,15]. While the landmark 1964 Surgeon General’s report [16] initiated a new wave of research aimed at developing multilevel, evidence-based interventions to reduce tobacco use [17], declines in smoking rates have not been realized across all populations, including LGBTQ+ people [18,19]. US government spending priorities complicate this issue. A meager 0.8% of National Institutes of Health funding concerns LGBTQ+ populations and most awards address HIV prevention and treatment [20]. Similarly, less than 2% of National Institutes of Health funding is directed to tobacco research [21] and the number of awarded tobacco research projects is declining [22]. These realities are problematic as evidence-based approaches rely on existing data and the scientific literature to inform intervention development. In the absence of robust funding for LGBTQ+ and tobacco-focused research, our ability to develop evidence-based interventions to reduce tobacco disparities is diminished. Accordingly, this traditional approach may fall short in producing solutions that fully address the needs of LGBTQ+ populations.

The emerging literature in LGBTQ+ tobacco control reveals that a complex web of psychosocial and environmental factors contributes to high tobacco use rates among LGBTQ+ populations, including structural stigma (i.e., discriminatory laws and practices), interpersonal minority stress and coping, targeted marketing by the tobacco industry, and social tobacco norms. Importantly, these influences do not affect all LGBTQ+ individuals uniformly. Patterns of tobacco use—and the risk factors that drive them—vary across sexual and gender identities (e.g., bisexual women, transgender men, non-binary youth) and their intersections with other facets of identity such as race, ethnicity, generational cohort, socioeconomic status, and geographic context [23,24]. An intersectional perspective [25] is therefore essential for both understanding and intervening in these disparities. By recognizing how overlapping aspects of identity and oppression shape tobacco use, designers and public health practitioners can better attend to within-group variation and avoid treating LGBTQ+ and other minoritized communities as monolithic populations [26].

Recognizing this heterogeneity is crucial for intervention development, as LGBTQ+ health researchers recommend applying cultural tailoring and targeting (CTT) to address the specific contexts driving tobacco disparities among LGBTQ+ populations [26,27]. Evidence indicates that adding CTT components to evidence-based tobacco cessation interventions intended for the general population can improve cessation rates among minoritized populations [28].

CTT encompasses distinct approaches. Cultural targeting designs a single intervention for a group based on shared cultural characteristics presumed to be consistent across its members [18]. Cultural tailoring, by contrast, adapts intervention content to the individual level by identifying and addressing meaningful within-group differences, and may involve [several variations of an intervention to reach [29]. Additionally, CTT can involve surface-level adaptations—such as modifying imagery, language, or symbols—and deep-level adaptations, which address cultural values, identity-related stressors, and underlying sociocultural meanings. Selecting among these approaches requires a nuanced understanding of both the commonalities and differences that shape tobacco use across intersecting LGBTQ+ identities.

These complexities underscore the need for intervention developers to critically examine assumptions about population homogeneity, consider intersectional identities, and make intentional, well-justified decisions about when targeting or tailoring and deep-level or surface-level approaches are most appropriate. Such reflection is essential for designing culturally responsive interventions for LGBTQ+ communities—and also exposes the limitations of relying solely on traditional evidence-based approaches, as discussed in the next section.

2.2. Limitations of the Evidence-Based Approach

Guidance for intervention development commonly emphasizes reviewing existing research evidence as a key action, recommended to be undertaken before beginning the development process [4]. This review is intended to facilitate defining and understanding the health problem, priority population, and context, as well as to identify facilitators, barriers, and uncertainties related to implementing interventions in the intended setting [4]. While this evidence-based approach offers value in grounding interventions in established knowledge supporting intervention feasibility and effectiveness, it also has its limitations.

For instance, evidence-based approaches, while valuable for grounding solutions, rely on generalizable perspectives that can constrain our ability to address the particularized and nuanced intricacies characterizing the complex reality of tobacco use cessation. CTT requires rigorous formative research and engagement of the target population as experts to both problematize tobacco cessation within the context of culture and develop solutions that align cessation interventions with target population members’ psychosocial experiences, norms, and beliefs. If and when innovation is a central goal, an evidence-focused approach alone may prove insufficient, often yielding only incremental advancements [30].

2.3. The Need for Alternative Problematization Methods

Therefore, we see a need to explore alternative problematization approaches that extend beyond utilizing evidence as a starting point—not to replace evidence, but to complement it with methods that foster more provocative exploration of issues, opportunities, and uncertainties early in the process. Approaching the problem from a new light can first reveal new issues, matters of concern and success criteria that open the possibilities for innovative intervention strategies that can later be refined and tested using evidence-based methods. Discursive design, we argue, is one such method with the potential to aid in unpacking the complexities of public health challenges, thereby expanding the possibilities for innovation in intervention development.

2.4. Discursive Design in Public Health

As described by Tharp & Tharp, discursive design involves creating artifacts or representations of artifacts as “tools for thinking”—designs not intended for practical implementation but aimed at stimulating reflection and “substantive, values-based exchange” among an audience about an intended discourse [8] (pp. 407–408). By leveraging the “visual and experiential” qualities of artifacts [9] (p. 115), this approach can stimulate “critical assessment” of an idea and “personal or emotive reflection” [9] (p. 116). In this way, discursive design can provoke alternative perspectives on problems that evidence-based methods alone may not.

Discursive design can be utilized in applied research, particularly as we envision its use in public health, to create artifacts that probe “subjects’ attitudes, beliefs, and values that are otherwise more difficult for researchers to access” [9] (p. 292). This problematization process, facilitated through design artifacts, fosters a “better understanding of the issue” and ultimately supports the creation of “better products, services, and systems,” or, in our case, interventions aimed at addressing and reducing health disparities [9] (p. 292).

3. Research Goal and Methodology

To examine the relevance and reception of discursive design in fostering new ways of accounting for culturally appropriate interventions in public health, we explored whether and how discussions among public health and allied experts on discursive speculative interventions problematized facets of culturally tailoring and targeting (CTT).

To facilitate these discussions, we developed and presented two discursive speculative intervention pairs to three focus groups of public health and allied experts, using them as stimuli to provoke reflection on CTT assumptions, limitations, and alternative possibilities.

The findings reported draw on insights from the focus groups conducted in January 2025, which engaged six participants. Our aim was to examine and analyze the ways through which discursive design influences public experts’ reactions to an innovative methodology for problem definition. The goal was not to measure the method’s impact, but to gauge the nature of participants’ reactions and better understand how discursive design can be leveraged to problematize approaches to culturally tailoring and targeting interventions, based on experts’ responses to the method and their reflections on its usefulness. In doing so, we explore how design can offer alternative perspectives on cultural appropriateness in public health and expand conversations about innovative, contextually responsive strategies to address health disparities.

Additionally, this research proposes hypotheses about the factors influencing experts’ engagement with CTT problematization and offers recommendations for future research to refine discursive design methodologies for more impactful contributions to public health intervention development.

To meet these research objectives, the study takes on the following question:

How might discursive design participate in the problematization of CTT strategies aimed at envisioning innovative solutions to public health disparities?

3.1. Discursive Speculative Artifacts Development

To address this question, the design of the discursive speculative interventions, or artifacts, was guided by the aim to provoke critical examination of CTT strategies for LGBTQ+ populations. Their iterative conceptual development drew on three key areas of literature:

- Frameworks for developing provocative discursive and speculative designs [7,8,9,13,31];

- Approaches to cultural tailoring and targeting [29];

- Research on the unique determinants of tobacco use among LGBTQ+ populations, including barriers to cessation, psychosocial experiences, norms, beliefs, and behaviors drawn from a broad body of public health research.

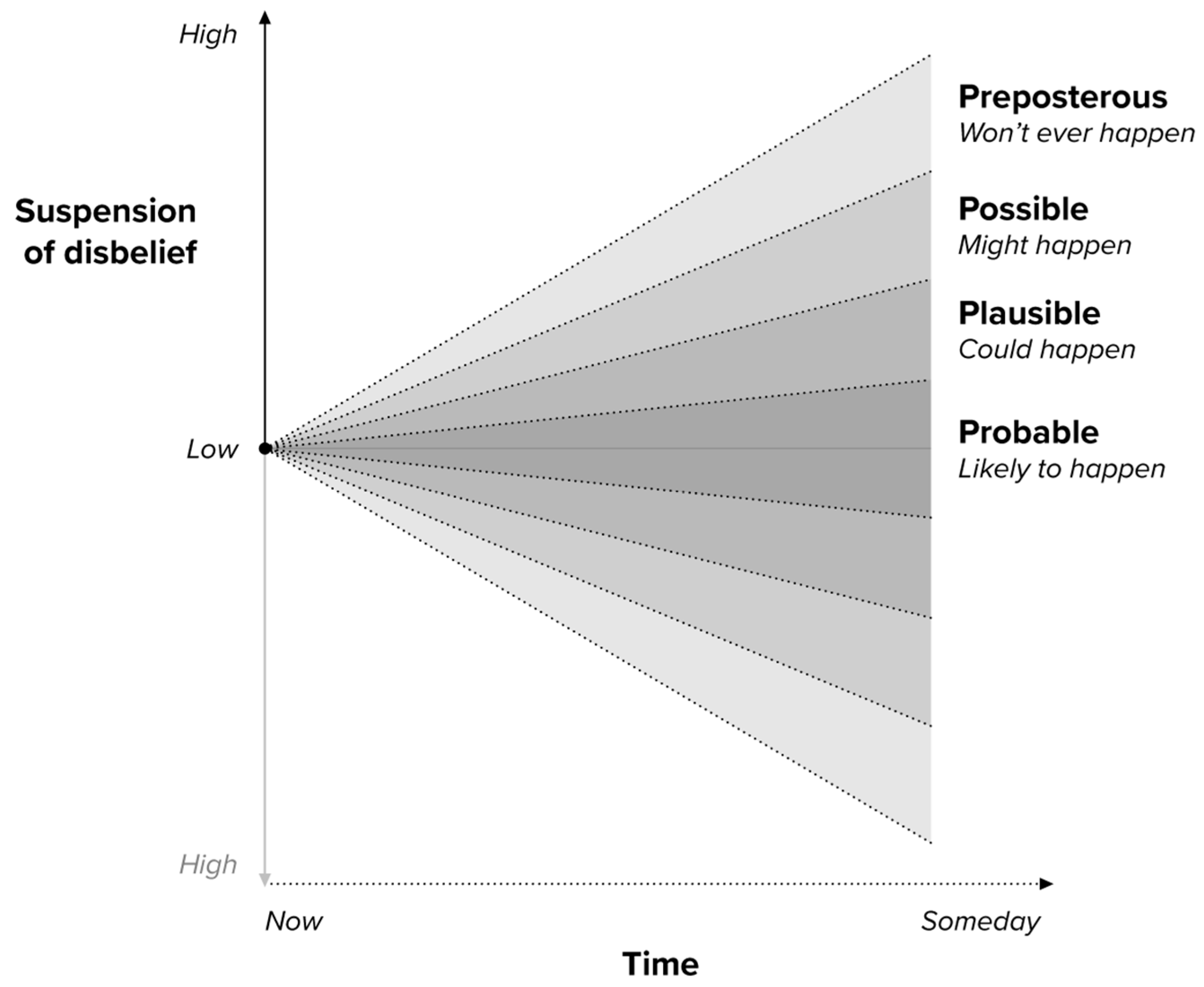

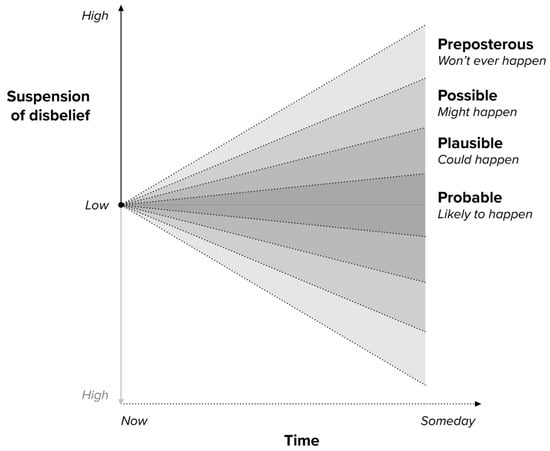

To ensure that the intervention concepts were not just speculative but also provocative in ways that align with discursive design principles, we drew from Kinch et al.’s playful speculative design framework and adopted the concept of exploring the “peripheral design space” of speculative design, referred to as “the preposterous” [13] (p. 3). This term originates from Kinch [31] expansion of Hancock and Bezold’s [13] Futures Cone framework (Figure 1), encompassing “the futures we judge to be ‘ridiculous,’ ‘impossible,’ or that will ‘never’” occur.

Figure 1.

Futures Cone diagram adapted from Kinch et al. [13], based on Voros’ [31] Futures Cone.

Preposterous alternatives stand in contrast to those within the ‘probable, plausible, and possible’ spaces, which represent what is ‘likely to,’ ‘could,’ or ‘might’ happen, respectively [31]. We see these traditional future categories—particularly the ‘probable’ and ‘plausible’—as reflective of evidence-based solutions due to their reliance on “current trends” and “our current understanding of how the world works”[31]. Kinch et al. contend that exploring alternatives beyond these traditional future categories “challenges our conventional thinking and ignites curiosity” by leveraging their provocative and imaginative potential [13] (p. 6).

To evaluate discursive design’s potential in a public health context, we framed our speculative interventions as contrasting pairs, each consisting of one “conventional” intervention—situated within the “probable” and “plausible” realms—and one “preposterous” intervention. Each pair centered around a shared context or strategy, with contrasts drawn within these frameworks. For instance:

- Pair 1: From Passive Cues to Direct Confrontation—Cultural Targeted and Tailored Interventions at the Point of Purchase

- Pair 2: Disrupting Convenience to Challenge Vaping Behaviors—From Motivational to Coercive Sociocultural Approaches

By juxtaposing conventional and preposterous interventions within these themes, we sought to leverage the contrast to provoke deeper reflection through two key mechanisms. Given that this method is largely unfamiliar in public health, scaffolding the interventions from conventional to preposterous served as an entry point for participants to engage with the aims of our discursive design approach. First, in alignment with Auger’s [7] “ecological approach,” the conventional intervention provided an accessible starting point, offering familiar and relatable conditions or solutions for the audience to ground their understanding. This grounding in familiarity amplified the impact of the preposterous intervention presented next, which introduced deliberate provocations designed to evoke “the uncanny,” as described by Freud, or “cognitive dissonance” [7]. This structured juxtaposition aimed to guide participants toward meaningful and reflective consideration of the potential implications of the preposterous interventions in real-world settings.

To further enhance “the uncanny” and encourage participants to imagine these interventions as if they were real, we visualized the interventions as high-fidelity, realistic mockups and presented them through scenarios. As part of this visualization strategy, several mockups included depictions of a potential user interacting with the intervention (and, when appropriate, text or audio indicating aspects of the user’s identity, such as sexual orientation). These representational choices served as subtle prompts to encourage participants to consider how individuals with different intersecting identities might experience or be affected by the intervention. By embedding cues related to race/ethnicity, gender, sexual identity, and age or generational cohort into the narrative and imagery, we sought to introduce an implicit intersectional lens—inviting participants to reflect on how the same intervention could carry different implications for different users. A step-by-step slideshow and narrative walkthroughs guided focus group participants through each intervention’s intended context and application, fostering an immersive experience.

Importantly, the purpose of presenting these speculative interventions was not to propose immediately viable solutions or guide participants toward selecting a specific intervention. Instead, they were designed as discursive tools to assess their ability and relevance in problematizing CTT approaches, sparking critical reflection and uncovering insights to inform culturally tailored and targeted solutions.

3.2. Participant Sampling and Recruitment

Six participants were recruited via professional networks for their expertise in tobacco regulation, prevention, cessation, and LGBTQ+ populations. These experts included academics and researchers specializing in public health behavior and health promotion, epidemiology, and environmental health, as well as professionals from fields that closely collaborate with public health professionals on interventions, including social work, psychology, and chemistry. The inclusion of participants from outside traditional public health roles reflected the interdisciplinary nature of addressing health disparities and fostered discussions with both breadth and depth.

Although the sample size was small, it was deemed adequate for the study’s exploratory orientation and aligned with the principle of information power [32]. As Malterud et al. [32] explain, information power suggests that smaller samples can be sufficient when the study’s aim is focused, the sample is specific, the analysis is theoretically informed, and the quality of dialogue is strong. While some of these conditions are more fragilely met, this study did meet several key criteria: (1) a narrow aim centered on how discursive methods may support problematization of culturally tailored and targeted interventions; (2) a strategically selected sample with relevant expertise; and (3) rich, high-quality discussions that generated substantive reflections, supporting depth of insights over breadth.

3.3. Focus Group Procedures

Focus group sessions were facilitated via Zoom. Each session lasted 1.5 h and included two participants to allow for in-depth discussion and exchanges. Participants signed a digital informed consent form prior to their session, permitting video and audio recording for transcription and analysis. All sessions followed a similar structure, detailed below in Table 1:

Table 1.

Phases of the discursive design focus groups.

3.4. Analysis

Focus group transcripts were analyzed using both a phenomenological approach and interpretive phenomenological analysis. The former was used to “examine participants’ experiences” engaging with discursive design, while the latter aimed to “develop themes and concepts” that represent and interpret their responses [33] (p. 20). To achieve this, we employed a combination of description- and interpretation-focused qualitative coding strategies [34] (p. 57).

This method served two purposes: (1) to determine whether participants problematized aspects of CTT, thereby evaluating the impact of the discursive design method, and (2) to generate tentative hypotheses about the factors influencing the focus, depth, and ease with which these responses were produced.

4. Discursive Speculative Intervention Pairs

4.1. Pair 1: From Passive Cues to Direct Confrontation—Cultural Targeted and Tailored Interventions at the Point of Purchase

The first discursive speculative intervention pair explores the point of purchase as a strategic setting for engaging LGBTQ+ people who smoke through culturally targeted and tailored interventions. Existing national policies mandating health warnings on cigarette packages highlight the potential of this setting to prompt reflection and encourage quit attempts at the critical moment of decision-making [35]. These intervention concepts respond to key questions: What other opportunities exist to intervene at the point of purchase? How might these interventions be made engaging? How can they be culturally targeted or tailored to better reach priority populations?

In terms of CTT, the conventional concept (Table 2, Figure 2) employs a more prominent peripheral approach to cultural targeting, making overt references to the LGBTQ+ population [29] (p. 135) In contrast, the preposterous concept (Table 3, Figure 3) adopts a deeper sociocultural tailoring strategy, subtly embedding LGBTQ+ values, beliefs, and behaviors [29] (p. 136) by referencing minority stress and chosen family [36].

Table 2.

Pair 1: Conventional Concept Description.

Figure 2.

This image illustrates a speculative, probable intervention where purchase receipts include culturally targeted quit messaging. A QR code links to an LGBTQ+-inclusive quitline, with callouts emphasizing key features like affirming language on the receipt and a badge for cultural competency training.

Table 3.

Pair 1: Preposterous Concept Description.

Figure 3.

Bottom left: This image represents the initial screen that interrupts a user when they go to pay for their tobacco purchase, displaying a “Pause Before Purchase” message before the tailored video plays. Top: This image illustrates the deepfake portion of the intervention, where a payment screen video generates a personalized message using the customer’s own likeness and voice. The background is imagined to be drawn from their personal photos—such as a familiar home setting—to enhance “the uncanny” [7]. Bottom right: This image presents the forced-choice confirmation dialog, requiring the customer to actively decide whether to proceed with the purchase or remove cigarettes from their cart.

4.2. Pair 2: Disrupting Convenience to Challenge Vaping Behaviors—From Motivational to Coercive Sociocultural Approaches

The second discursive design intervention pair explores e-cigarette cessation. While vaping is often promoted as a harm reduction tool for cigarette cessation, it poses new risks—particularly for youth—due to its addictive nature and negative effects on brain development and overall health [37]. This issue is especially relevant to LGBTQ+ communities, as both LGBTQ+ young people in 2021 [38] and LGB adults from 2019 to 2021 [39] (p. 92) reported higher rates of ever and current e-cigarette use than their non-LGBTQ+ peers.

One key factor contributing to vaping’s widespread use is its convenience [40]. Unlike cigarettes, vapes lack a strong smell, are easy to use discreetly, and can often be used in spaces where smoking is prohibited—making them both accessible and appealing. Therefore, this intervention pair explores how disrupting vaping’s convenience can encourage cessation while also examining deep sociocultural strategies for CTT [29] (p. 136) and varying engagement approaches, from motivational (Table 4, Figure 4) to coercive (Table 5, Figure 5).

Table 4.

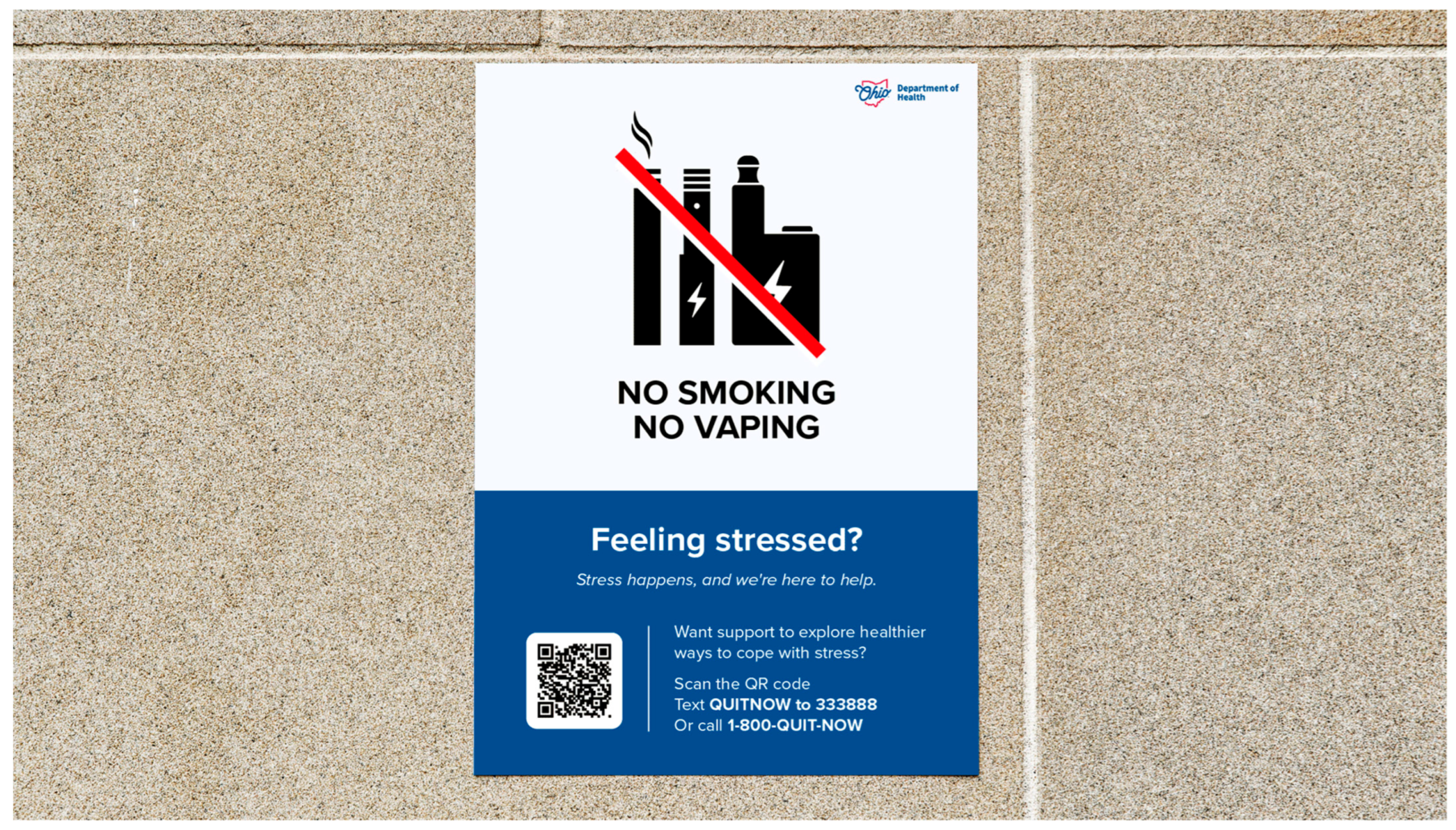

Pair 2: Conventional Concept Description.

Figure 4.

This image illustrates a speculative, probable intervention where no-smoking/no-vaping signage integrates stress-related messaging alongside cessation resources. The design pairs restriction with support, using a QR code to connect individuals to additional quitting assistance.

Table 5.

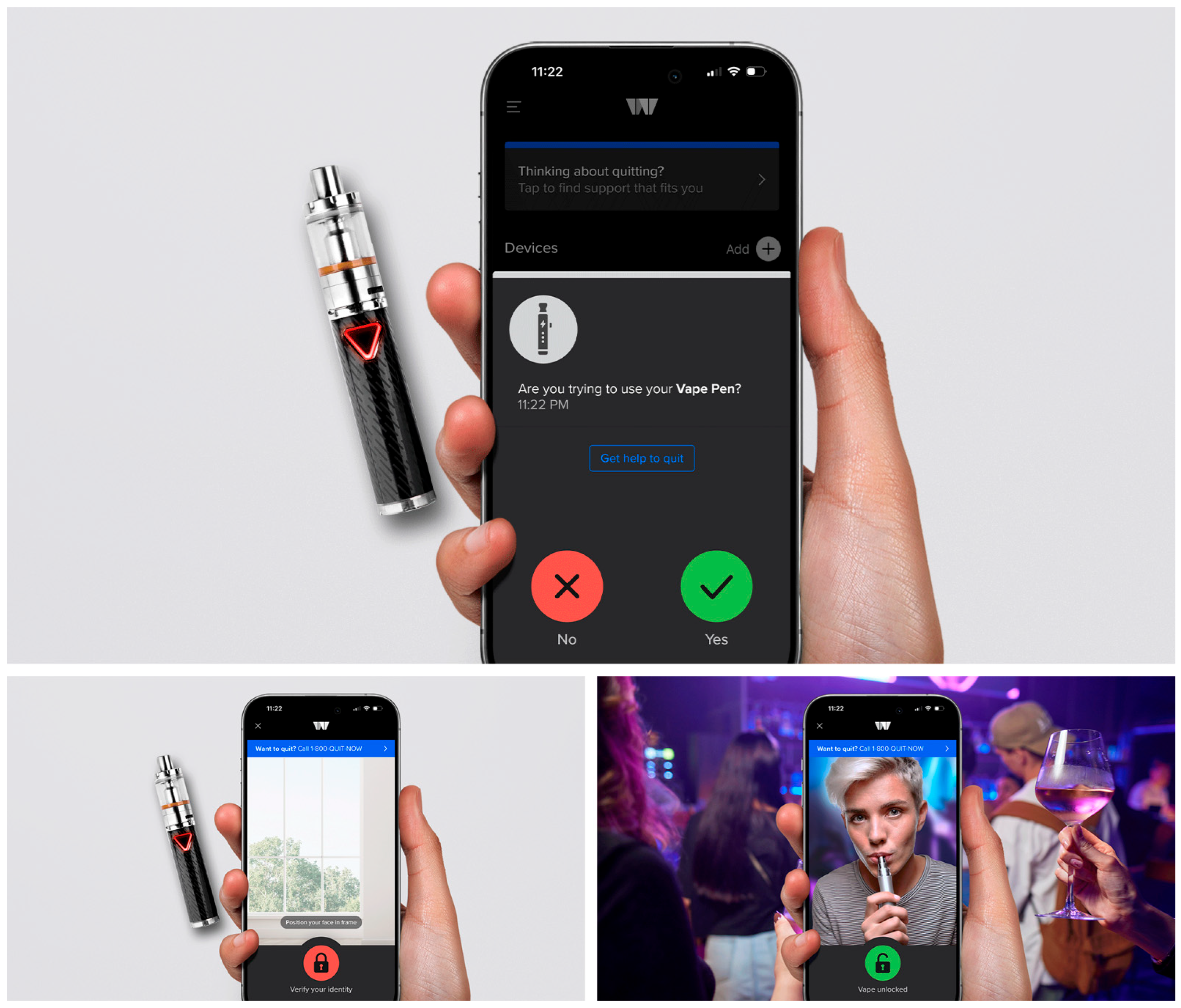

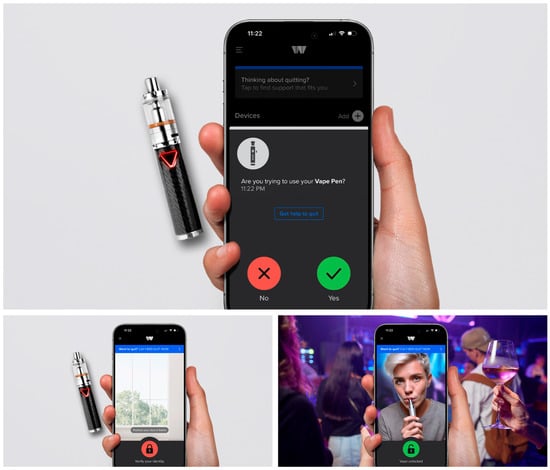

Pair 2: Preposterous Concept Description.

Figure 5.

Top: This image illustrates the initial authentication prompt, where attempting to activate a vape device triggers a push notification on the user’s smartphone, requiring confirmation before proceeding. Bottom left: This image depicts the face verification step, where users must hold their phone up to their face for the duration of activation. Here, the vape remains locked as the user’s face is not in frame, emphasizing the added friction in the process. Bottom right: This image demonstrates the intervention’s disruptive effect in social settings, making vaping more conspicuous by requiring a visible authentication process, potentially deterring habitual use.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Evaluating the Impact of Discursive Design

According to Tharp & Tharp, measuring the impact of discursive design in applied research is challenging due to factors such as unintended consequences, which require researchers to reconcile both positive and negative results, and variable contexts, in which participants may perceive and respond to artifacts differently [9] (pp. 295–296). Because of these complexities, they suggest that the primary concern should be whether discursive design has an impact at all, rather than attempting to measure it precisely [9] (p. 285). However, in contexts where demonstrating its value is necessary—such as this study—Tharp & Tharp propose audience reflection as a baseline indicator of success [9] (p. 290). Since reflection is broad and sometimes ambiguous, they outline three more structured categories of effectiveness to assess meaningful impact in applied settings.

The following table (Table 6) summarizes this structured approach, detailing the three levels of impact—relevant thinking, relevant responses, and actionable insights—along with their definitions, measurements, and specific applications to this study.

Table 6.

Levels of Impact in Evaluating the Success of Discursive Design in Applied Research.

Since we cannot directly access participants’ thoughts, our evaluation focuses on two measurable indicators: (1) relevant responses as evidence of relevant thinking and (2) actionable insights derived from these responses.

5.2. Relevant Responses and Actionable Insights

For this study, our first concern was whether discursive design can effectively problematize CTT strategies aimed at envisioning innovative solutions for public health disparities. Based on our current analysis, we tend to believe that it can: relevant responses were indeed generated, and actionable insights emerged through the discursive design method.

To illustrate this, Table 7 presents a sample of participant responses that problematize CTT strategies, alongside the specific intervention concept being discussed and the actionable insights that can inform the development of more effective and contextually relevant interventions.

Table 7.

Sample of participant responses problematizing CTT strategies and corresponding actionable insights.

Notably, while several participants interrogated both the mechanisms of CTT and the effectiveness of the interventions’ attempts to signal inclusivity and personalized messaging (Participants 1, 2, 4, 5), others focused on broader feasibility and contextual issues—for example, the difficulty of disentangling overlapping drivers of smoking for specific populations or designing interventions that address the social reinforcement of vaping (Participants 3, 6). This diversity of responses—generated through engagement with the discursive design concepts—demonstrates the breadth of culturally relevant considerations that this method can elicit. Such insights are critical for intervention developers designing interventions for socioculturally defined populations.

However, while the responses summarized in Table 5 indicate that the discursive interventions generated relevant and actionable insights, these insights were not raised consistently across participants. Responses directly engaging with CTT strategies were more limited than those addressing broader intervention concerns. Participants seemed to raise concerns more often about privacy, feasibility, implementation challenges, and general social acceptability rather than interrogating the CTT strategies themselves. This does not necessarily read as a limitation of discursive design. On the contrary, it demonstrates that public health experts’ focus on technical considerations such as feasibility may actually hinder their ability to raise critical questions and to account for the sociocultural dimensions that should inform intervention strategies.

Moreover, despite this pattern, the examples highlighted above demonstrate that, when engagement with CTT does occur, discursive design directly supports critical examination of the underlying assumptions, mechanisms, and value tensions that shape such interventions. We hypothesize that because the concepts were presented as high-fidelity, scenario-based mockups, participants were able to interrogate concrete manifestations of CTT and begin to speculate about their implications, which led to more mechanism-specific insights. For example, as shown in Table 5, the preposterous concept in Pair 1 enabled Participant 2 to articulate both what felt meaningful in a deeply tailored intervention for LGBTQ+ folk (e.g., references to family as a culturally salient motivator) and what felt unpalatable about a forced, opt-out personalization system. This response surfaces a foundational problematization question for CTT: at what point does deep tailoring shift from supportive to intrusive, and how should interventions balance autonomy with personalization? Although these discussions did not resolve such questions, the method clearly seeded them. Notably, this reflection could also translate into a highly specific actionable insight—the need for optional, user-driven personalization features (e.g., allowing individuals to input their own motivators)—illustrating how discursive design can move from speculative provocation to concrete design direction.

Taken together, the ability of discursive design to elicit both deeper CTT-specific reflections and broader contextual concerns underscores a key strength of the method: it can surface considerations—such as cultural, psychosocial, practical, or ethical ones—that often remain implicit or underexamined until later in intervention development. By confronting intervention developers with these considerations early on—through the evaluation of speculative interventions situated within imagined yet concrete contexts, involving particular people, settings, and touchpoints, consistent with Auger’s [7] ecological approach—discursive design helps make implicit assumptions explicit, fostering proactive rather than reactive problem-solving. This, in turn, creates opportunities for more nuanced, adaptable, and contextually responsive solutions—for both generalized and culturally specific populations.

However, while these broader considerations are valuable in their own right, the relative lack of direct engagement with CTT-specific mechanisms suggests a need to explore not only why experts problematized certain aspects but also the depth and ease with which they did so. The next two sections outline hypotheses derived from our preliminary results regarding factors that may have influenced experts’ engagement with discursive speculative designs.

If our hypotheses hold, these factors could have significant implications for determining both who should participate in discursive design discussions on cultural tailoring and targeting and how best to engage them—both of which are crucial for maximizing relevant, actionable insights for intervention development. Thus, both sections outline potential refinements to enhance experts’ engagement with CTT-specific concepts, highlighting key directions for future research.

5.3. Expertise and Problematization: Who Should Be at the Table?

Our preliminary data suggest that participants’ professional or disciplinary backgrounds influenced the relevance and depth of their responses regarding cultural tailoring and targeting. Participants with strong expertise in LGBTQ+ health appeared to engage in more nuanced and critical evaluations, assessing not only the degree of tailoring but also the underlying mechanisms shaping its effectiveness or limitations. For example, in response to Pair 1: Conventional Concept, Participant 2 reflected:

“I really appreciated sort of the open-ended, or sort of broadly inclusive focus of the receipt. And then, say you did use the QR code and go to the website—would the focus on LGBTQ+ populations actually potentially create barriers or disrupt in some way other marginalized populations? Because [...] if we think about marginalized populations, they’re at higher risk of substance use disorders. Is focusing on one population the most effective approach versus presenting material in some way that shows inclusion across populations? Also, because of intersectionality in LGBTQ+ populations and who tends to use substances in the LGBTQ+ community—what subgroups?”(Participant 2)

This quote demonstrates a deeper level of problematization, interrogating not just the presence of tailoring but also its broader implications for intersectionality and inclusion. Such an evaluation is one that the method sought to elicit—yet one that only some participants articulated. In contrast, participants with limited understanding of LGBTQ+ populations tended to focus more broadly on whether the intervention seemed tailored rather than critically assessing the means or implications of that tailoring. For example, after viewing the same concept (Pair 1: Conventional Concept), Participant 1′s initial reflection regarding cultural tailoring and targeting was:

“And while I appreciate the badge on, like, the LGBTQ+ training, this isn’t an especially highly targeted message for this specific population. But for other populations I think it’s an interesting idea.”(Participant 1)

A similar pattern appeared in responses to Pair 1: Preposterous Concept. Participants with more experience working with LGBTQ+ populations appeared more attuned to deep-tailoring strategies that address psychosocial factors, norms, and behaviors, rather than relying solely on explicit tailoring markers. For instance, Participant 6 evaluated the balance between broad and highly personalized tailoring in Pair 1: Preposterous Concept:

“So too general a smoking cessation might not be effective, but too tailor[ed] at the level of feeling like my privacy is invaded [...] That’s gonna make more issues than [be effective]. [...] So I agree with [Participant 5]’s point—it’s about balance. So [a] surface level of tailoring, such as mentioning stress or financial savings for quitting smoking—because there are a bunch of literature studies about why people are using or want to quit smoking—I think a surface level of tailoring might be enough.”(Participant 6)

While we argue that references to stress, when contextualized within LGBTQ+ experiences of minority stress, constitute a form of deep or sociocultural tailoring, this response illustrates a nuanced understanding of how different intervention elements may be tailored to specific populations. In contrast, participants with less expertise in LGBTQ+ populations seemed to focus more on explicit, peripheral markers of inclusion rather than the underlying mechanisms that contribute to cultural relevance. This distinction is evident in Participant 3′s assessment of cultural tailoring across interventions after viewing Pair 2: Preposterous Concept:

“I feel like, outside of the little badge that [..] you had in the QR code that went to the actual website—none of these necessarily feel very tailored to that population in the small experience that I have had, you know, doing some research and things with that priority population.”(Participant 3)

In interpreting these contrasting orientations, our data suggest that culturally grounded expertise supports deeper CTT analysis. Importantly, we do not claim that one form of engagement is superior. Rather, these differences illustrate how participants’ knowledge bases shape the problematization process in complementary ways. As Magistretti et al. [41] emphasize in their integrative review of the creative process of problem framing, different participants bring distinct forms of knowledge that can be activated as lenses for interpreting a problem. Yet, they caution that such orientations may also lead participants to fixate on familiar ways of seeing. This dynamic was evident in our data, as some experts appeared especially attuned to particular dimensions of the discursive artifacts.

At the same time, diversity among problem-framing teams—whether cultural, cognitive, or practice-based—enables a broader set of potential frames [41]. In this study, that diversity helped ensure that unintended consequences were not overlooked (Participant 2) while also keeping attention on broader strategic considerations (Participant 1). Participants further raised important questions about what constitutes an effective balance between sociocultural (Participant 6) and peripheral (Participant 3) tailoring in CTT interventions.

While we hypothesize that professional and disciplinary backgrounds shaped these orientational differences, they were not the only influence. Participants’ unique lived experiences, constituting a form of knowledge, undoubtedly contributed, among other factors. Nor do we suggest that disciplinary background effects are a novel finding; rather, we highlight their relevance for public health research and intervention development, especially when assembling expert teams to problematize culturally tailored and targeted interventions.

Future research could build on this observation by more explicitly examining how participants’ disciplinary identities shape their engagement in discursive problematization. Sociologist Harvey Sacks’ Membership Categorization Analysis (MCA) [42] offers a useful lens for examining how participants’ disciplinary identities may have shaped their contributions. This was evident in our data: Participant 1 drew on their policy background to assess feasibility within existing regulatory frameworks (“I study policy—so I was like, ‘Of course, it would have to be a policy in order for it to happen.’”), while Participant 3, a clinical psychologist, emphasized the role of behavior change in intervention effectiveness (“Again, if you’re thinking about—clinical psychologist [here] [laughs]—if you’re thinking about wanting to get people to change, you have to identify the things that are most salient to them, right?”). Applying MCA to analyze our data could provide deeper insight into how disciplinary backgrounds influence problematization in discursive design sessions. Together, these patterns point to the need for intentional team composition in discursive problematization efforts.

Our findings suggest that including experts with deep knowledge of the priority population is essential for ensuring contextual relevance, while simultaneously engaging a diverse set of experts—including those from adjacent fields outside traditional public health domains—can enrich discussions by surfacing overlooked aspects of problematization. As Magistretti et al. propose, “by fostering systematic interactions with diverse problem constituents, the creative process of problem framing enables deeper creative leaps and multiple problem framings” [41] (p. 1006). Diversity, then, is not simply desirable but critical to generating innovative and relevant frames.

At the same time, when interventions are intended for a specific population, authentic representation becomes essential; lived experience offers cultural and contextual insights that even experts with experience working with the intended population may not access. Building on this, future studies could strengthen the problematization process by involving members of the priority population who can diagnose discursive intervention concepts through the lens of lived experience. As Kreuter et al. [29] argue, “constituent-involving strategies” are vital for cultural tailoring, and Magistretti et al. [41], similarly stress how culturally diverse teams access different cultural lenses to interpret problems. Therefore, co-designing or evaluating discursive artifacts with community members may enhance the novelty and relevance of responses by grounding them in lived experience and population priorities that professionals alone may overlook.

Taken together, these findings highlight how the interplay between specialized domain knowledge, lived experience, and diverse disciplinary perspectives can foster productive discursive design discussions that push beyond conventional assumptions—an area warranting further exploration in future research.

5.4. Readiness for Speculative Thinking: Challenges and Opportunities

However, assembling the right mix of expertise is only one part of the equation. Once the right people are at the table, how do we effectively engage them in problematizing a given topic? This section explores key challenges in discursive speculative engagement around cultural tailoring and targeting, including (1) unclear boundaries between CTT strategies, (2) misunderstandings of speculative framing and the broader aims of discursive design, and (3) professional constraints that may limit experts’ ability to fully and openly engage in speculative thinking.

The first challenge of note was the lack of a shared understanding of CTT strategies. Some participants demonstrated familiarity with distinctions such as tailoring versus targeting or surface-level (peripheral) versus deep (sociocultural) approaches, while others engaged more superficially or conflated these concepts. For instance, Participant 6′s reference to targeted messaging about sociocultural realities like minority stress as “surface-level” rather than deep-level (as previously discussed) highlights how even among public health experts, these distinctions are not always clear.

In our assessment, these knowledge gaps appeared to limit participants’ ability to critically evaluate CTT approaches, raising the question: Would establishing a shared understanding of CTT strategies lead to more novel insights? Or is it more valuable to have experts introduce these distinctions organically, enriching discussions without requiring a standardized vocabulary? If a shared foundation is beneficial, should discursive design efforts incorporate introductory material on key CTT strategies? Or should this knowledge-building be a broader responsibility within public health? We pose these questions for future investigation.

A related challenge concerns participants’ readiness to engage intersectionality. As noted in Section 5.3, only some participants recognized how intersecting identities shape the relevance, risks, and implications of particular tailoring and targeting strategies. This suggests that intersectional reasoning cannot be assumed, even among experts, and may require more intentional methodological scaffolding than was incorporated in our current session structure. Future discursive design work could more deliberately scaffold intersectional engagement by integrating prompts that invite participants to consider how interventions might differentially support—or disadvantage—users positioned at varying intersections of race, gender identity, sexual identity, age, socioeconomic status, and geographic location. For example, presenting multiple high-fidelity mockups featuring users with contrasting intersectional identities could elicit richer and more equity-attentive insights. Similarly, discussion cues such as, “How might this intervention operate for an older transgender adult?” or “How would this concept be experienced differently in a rural community?” could push reflection beyond surface-level identity markers. Such extensions would help ensure that intersectionality becomes an active analytical lens within discursive problematization rather than a background consideration.

Another issue that emerged was participants’ varying interpretations of the distinction between the speculative and preposterous framing. While some participants appreciated the structured progression from familiar to speculative ideas, others expressed confusion or resistance to the framing. Participant 2, for example, found the scaffolded approach helpful in understanding the purpose behind the discursive speculative process:

“I think one thing I really appreciated about this experience is that it was scaffolded so well. Like, you walking us through each step and building to it, understanding the purpose behind it and why this big future-thinking kind of approach is important, was really helpful.”(Participant 2)

In contrast, Participant 4 questioned the effectiveness of presenting conventional interventions first and challenged the classification of the Pair 1: Conventional Concept:

“If the QR code [Pair 1: Conventional Concept] was the more conventional type of intervention, your other two scenarios did nothing but redirect us to go back to the first one. […] So now, if I imagine your methodology presenting these two [preposterous concepts] before the QR code—we might have another reflection on that. […] we would not go back all the time saying like, “Hey, the QR code is a great idea.” […] for us—for me—it’s not conventional. […] I don’t know if presenting [Pair 1: Conventional Concept] at the beginning is shooting yourself in the foot because the other[s] [preposterous concepts] seemed really imaginative and far from reality. But the QR code could be implemented tomorrow.”(Participant 4)

This response reveals two key tensions in participants’ engagement with the discursive design framework. The first concerns Participant 4′s interpretation of the distinction between the conventional and the preposterous. Their comments suggest a conflation of “conventional” with a lack of novelty or innovation. In contrast, our framework defines the conventional space as one that permits incremental innovation within familiar constraints, whereas the preposterous space opens the possibility for more transformative innovation, in which the very narrative around the solution shifts [13,30]. The difficulty some participants faced in navigating this distinction underscores the need to refine how these categories are introduced and communicated in future discursive design sessions.

Second, Participant 4′s quote speaks to the tendency of some participants to evaluate the discursive speculative interventions (even the conventional ones) as if they were actual intervention proposals rather than tools for reflection, demonstrating a broader misunderstanding of the purpose of discursive design. We argue that Participant 4′s quote demonstrates some participants’ tendencies to focus on implementation, evaluating more surface-level critiques of if a concept “would work,” demonstrating a difficulty with considering deeper questions about implications and possibilities revealed through “what if” thinking, exploring what it would take for a particular intervention to exist and what that might mean for public health practice if real. While a limitation of discursive design, this critique also suggests its importance for surfacing such a mindset.

Lastly, these observations bring us back to the question of how disciplinary and professional backgrounds shape experts’ engagement in discursive speculative thinking. However, whereas the previous section explored how these backgrounds influenced the focus and depth of problematization, we now turn to their impact on participants’ readiness to engage in speculative thinking itself. Some participants may struggle with suspending their disbelief to consider intervention concepts more thoroughly due to entrenched disciplinary norms, expectations, and constraints.

Participants 5 and 6 directly addressed this issue when reflecting on the strengths and limitations of discursive design. Participant 5, for instance, highlighted practical barriers such as fiscal constraints, time limitations, and the rapidly evolving tobacco landscape as challenges for integrating discursive design into intervention development:

“Creating a new intervention already takes a lot of money and time. But with this approach, I think... I want to say it’s going to take two or three times more than that, because you have to think from the extreme phase to the realistic phase too. That’s why, practically speaking, discursive design as a methodology […] is it really beneficial to take that money and time? Our resources are limited. Like, in research—the tobacco industry is getting changed very rapidly—new tobacco products are appearing right now. So, you may want to think about, like, the practicality of this research design.”(Participant 6)

In response, Participant 5 suggested that the feasibility and perceived value of discursive design may also be shaped by the academic versus industry context:

“And maybe one of the issues is context too, [Participant 6], because we are in academia, where we are not reinforced for taking great risks. In fact, we’re disincentivized for taking great risks [laughs] […] In industry, there are plenty of places where people are ready to pursue big ideas and have the funding to do it.”(Participant 5)

This reflection prompted Participant 6 to acknowledge their own bias and professional conditioning, recognizing how their academic background may have influenced their engagement with the approach:

“Yeah, actually […] I’m biased because I’m an academician. So, I’m always taking the most safe, most conventional thing. But sometimes some people want to take a risk. No risk, no gain. So, high risk, high return. So that could be a strength or weakness.”(Participant 6)

This exchange underscores the role of disciplinary positioning in shaping experts’ willingness and ability to engage in speculative inquiry. Future research could employ Membership Categorization Analysis to examine how participants invoke their professional identities (e.g., “academician”) in speculative engagement, providing deeper insight into the barriers and facilitators of this process. These insights could inform refinements to discursive design procedures, ensuring better support for experts across varying levels of readiness for speculative thinking.

Building on these observations, we offer two potential strategies for scaffolding speculative engagement in future work. First, conceptual scaffolding could include brief, pre-session primers that clarify the purpose of discursive design, distinguish conventional from preposterous scenarios, and explicitly frame the artifacts as tools for reflection rather than as implementation-ready proposals. Second, scaffolding in the methodology could involve short warm-up exercises that invite participants to practice “what if” thinking in domains that are lower stakes (e.g., imagining preposterous futures for everyday objects) before turning to more sensitive public health topics.

Addressing these barriers—whether through structured introductions to key concepts or preparatory speculative thinking exercises—is essential for maximizing the impact of discursive design in public health. These refinements could not only strengthen expert engagement, leading to more useful insights to help address health disparities, but also help convey the broader value of design beyond its traditionally conceived aesthetic and solution-focused role.

6. Conclusions

Our findings highlight discursive design as a promising tool for problematizing cultural tailoring and targeting strategies in developing CTT interventions for priority populations experiencing health disparities, such as LGBTQ+ communities. Public health and allied experts were generally receptive, demonstrating a willingness to collaborate with designers—an encouraging sign for interdisciplinary partnerships that could expand how public health interventions are conceptualized and implemented. In other words, the research results suggest a breadth of opportunities for critical and discursive design practices not to envision implementable solutions but feed mindsets on how to tackle complex public health challenges.

In particular, [and the findings about how discursive design specifically supported problematization of CTT aspects].

However, effectively folding experts into the discursive design method in applied research remains a challenge. Differences in disciplinary orientations, familiarity with speculative thinking, practical constraints, and varying levels of [tendency to engage in] with intersectional analysis appeared to shape both the focus and depth of engagement. Some participants were more likely to interrogate the mechanisms and implications of CTT strategies—including their intersectional equity consequences—while others gravitated toward feasibility, acceptability, and implementation concerns. These patterns point to the need for conceptual, methodological, and intersectional scaffolding if discursive design is to reliably support early-stage problematization of CTT in public health.

The study’s small sample also introduces important limitations. Although well-suited for generating in-depth, exploratory insights, a six-participant sample cannot capture the full range of perspectives within tobacco control or LGBTQ+ health, nor can it support broad claims about how discursive design may operate across contexts. Accordingly, the findings should be interpreted as provisional and hypothesis-generating rather than conclusive. Future research would benefit from expanding the sample to include a wider array of public health practitioners and LGBTQ+ community members to assess the transferability of these insights and to examine how discursive design methods function in more diverse settings.

Building on these limitations and insights, we see several priorities for future research. Methodologically, discursive design sessions could be refined through pre-session primers that clarify the purpose of discursive design and distinguish conventional from preposterous scenarios, warm-up exercises that build comfort with “what if” thinking, and explicit prompts or visual variants that foreground intersectional differences in race, gender identity, sexual identity, age, socioeconomic status, and place. Importantly, future studies could examine how different groups of participants—such as combinations of public health experts, designers, and community members with lived experience—shape the kinds of frames, concerns, and opportunities that emerge. Comparative work across other public health topics could further test the generalizability of discursive problematization as a complement to evidence-based approaches.

Taken together, this research marks a meaningful first step in integrating discursive design into public health intervention development and advancing understanding of design’s role in public health. By positioning discursive design as a method for early-stage problematization—rather than as a later-stage tool for crafting solutions—this study contributes to emerging efforts to bridge the gap between design and public health and to cultivate more innovative, intersectionally attuned responses to persistent health disparities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P. and N.W.; methodology, N.W., S.P. and J.G.P.; formal analysis, N.W.; writing—original draft preparation, N.W.; writing—review and editing, S.P.; visualization, N.W.; supervision, S.P. and J.G.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ohio State University’s OHRP Federal wide Assurance #00006378 (protocol code: 2024E0950, 17 September 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript and study, the authors used ChatGPT 4.o for the purposes of proofreading and grammatical check. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. We would like to thank the students in the LGBTQ+ Health Equity Lab at The Ohio State University for their thoughtful engagement as pilot testers in this project. We are also grateful to the professionals who generously contributed their time and insights as study participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- DiFranza, J.; Clark, D.; Pollay, R. Cigarette package design: Opportunities for disease prevention. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2003, 1, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, M.; Morley, C.; Horan, J.K.; Cummings, K.M. The cigarette pack as image: New evidence from tobacco industry documents. Tob. Control 2002, 11, I73–I80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzano, A.; Martin, J. Designing Public Health: Synergy and Discord. Des. J. 2017, 20, 735–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Cathain, A.; Croot, L.; Duncan, E.; Rousseau, N.; Sworn, K.; Turner, K.M.; Yardley, L.; Hoddinott, P. Guidance on how to develop complex interventions to improve health and healthcare. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proulx, S. Questioning the Nature of Design Activity Through Alasdair MacIntyre’s Account of the Concept of Practice. Des. J. 2019, 22, 649–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proulx, S.; Gauthier, P.; Hamarat, Y. Qualities of Public Health: Toward an Analysis of Aesthetic Features of Public Policies. In Design and Living Well; Muratovski, G., Vogel, C., Eds.; Intellect; JSTOR: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, J. Speculative design: Crafting the speculation. Digit. Creat. 2013, 24, 11–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharp, B.M.; Tharp, S.M. Discursive design basics: Mode and audience. Nordes 2013, 1, 5. Available online: https://archive.nordes.org/index.php/n13/article/view/326 (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Tharp, B.M.; Tharp, S.M. Discursive Design: Critical, Speculative, and Alternative Things; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, K.E.; Tree, J.N.J.; Giles, M.; El-Sharkawy, K.; Hall, E.; Valera, P. Smoking Cessation Interventions for LGBT Populations: A Scoping Review and Recommendations for Public Health. Ann. LGBTQ Public Popul. Health 2023, 4, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapinski, M.K.; Oetzel, J.G.; Park, S.; Williamson, A.J. Cultural Tailoring and Targeting of Messages: A Systematic Literature Review. Health Commun. 2025, 40, 808–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baskerville, N.B.; Shuh, A.; Wong-Francq, K.; Dash, D.; Abramowicz, A. LGBTQ Youth and Young Adult Perspectives on a Culturally Tailored Group Smoking Cessation Program. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2017, 19, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinch, S.; Rahbek, J.U.; Behrendtzen, S. Playful Speculative Design: Crafting Preposterous Futures Through Playful Tension. DRS Biennial Conference Series. 2024. Available online: https://dl.designresearchsociety.org/drs-conference-papers/drs2024/researchpapers/57 (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Rigotti, N.A.; Wallace, R.B. Using Agent-Based Models to Address “Wicked Problems” Like Tobacco Use: A Report from the Institute of Medicine. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 163, 469–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittel, H.W.J.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lushniak, B.D.; Samet, J.M.; Pechacek, T.F.; Norman, L.A.; Taylor, P.A. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/21569 (accessed on 9 February 2025).

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Smoking Cessation. A Report of the Surgeon General; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020.

- Li, J.; Berg, C.J.; Weber, A.A.; Vu, M.; Nguyen, J.; Haardörfer, R.; Windle, M.; Goodman, M.; Escoffery, C. Tobacco Use at the Intersection of Sex and Sexual Identity in the U.S., 2007-2020: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 60, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchting, F.O.; Emory, K.T.; Scout; Kim, Y.; Fagan, P.; Vera, L.E.; Emery, S. Transgender Use of Cigarettes, Cigars, and E-Cigarettes in a National Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, e1–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weideman, B.C.D.; Ecklund, A.M.; Alley, R.; Rosser, B.R.S.; Rider, G.N. Research Funded by National Institutes of Health Concerning Sexual and Gender Minoritized Populations: A Tracking Update for 2012 to 2022. Am. J. Public Health 2025, 115, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.R. National Institutes of Health Funding for Tobacco Versus Harm From Tobacco. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2016, 18, 1299–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Meissner, H.I.; Sharma, K.; Mandal, R.J.; Garcia-Cazarin, M.; Wanke, K.L.; Moyer, J.; Liggins, C. NIH Tobacco Research and the Emergence of Tobacco Regulatory Science. Nicotine Tob. Res. Off. J. Soc. Res. Nicotine Tob. 2022, 24, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffer, C.E.; Williams, J.M.; Erwin, D.O.; Smith, P.H.; Carl, E.; Ostroff, J.S. Tobacco-Related Disparities Viewed Through the Lens of Intersectionality. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2022, 24, 285–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.J.; Lawrence, S.E.; McCauley, P.S.; Wheldon, C.W.; Fish, J.N.; Eaton, L.A. Examining tobacco use at the intersection of gender, sexual orientation, race, and ethnicity using national U.S. data of sexual and gender diverse youth. Addict. Behav. 2025, 163, 108246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1991, 43, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antin, T.; Cartujano-Barrera, F.; De Genna, N.M.; Hinds, J.T.; Kaner, E.; Lee, J.; Patterson, J.G.; Ruiz, R.A.; Stimatze, T.; Tan, A.S.L.; et al. Structural stigma and inequities in tobacco use among sexual and gender minoritized people: Accounting for context and intersectionality. Nicotine Tob. Res. Off. J. Soc. Res. Nicotine Tob. 2025, 27, 1871–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, J.G.; McQuoid, J.; Heffner, J.L.; Ye, Q.; Ennis, A.C.; Ganz, O.; Tan, A.S.L. Resonating With Pride: Considerations for Tailoring Tobacco Interventions for LGBTQ+ Communities. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2024, 26, 1438–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leinberger-Jabari, A.; Golob, M.M.; Lindson, N.; Hartmann-Boyce, J. Effectiveness of culturally tailoring smoking cessation interventions for reducing or quitting combustible tobacco: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Addiction 2024, 119, 629–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuter, M.W.; Lukwago, S.N.; Bucholtz, D.C.; Clark, E.M.; Sanders-Thompson, V. Achieving Cultural Appropriateness in Health Promotion Programs: Targeted and Tailored Approaches. Health Educ. Behav. 2003, 30, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verganti, R. Design, Meanings, and Radical Innovation: A Metamodel and a Research Agenda. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2008, 25, 436–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voros, J. Big History and Anticipation. In Handbook of Anticipation: Theoretical and Applied Aspects of the Use of Future in Decision Making; Poli, R., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, P. Review of qualitative approaches and their data analysis methods. In A Step-by-Step Guide to Qualitative Data Coding, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Adu, P. Understanding the art of coding qualitative data. In A Step-by-Step Guide to Qualitative Data Coding, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; pp. 23–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, D.; Fong, G.T.; Borland, R.; Cummings, K.M.; McNeill, A.; Driezen, P. Communicating Risk to Smokers: The Impact of Health Warnings on Cigarette Packages. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 32, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, R.L.; Gonzalez, K.A.; Arora, S.; Sostre, J.P.; Lockett, G.M.; Mosley, D.V. “Coming together after tragedy reaffirms the strong sense of community and pride we have:” LGBTQ people find strength in community and cultural values during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2023, 10, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinardo, P.; Rome, E.S. Vaping: The new wave of nicotine addiction. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2019, 86, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truth Initiative. LGBT+ Young People Smoke and Vape at a Higher Prevalence than Non-LGBT+ Peers; Truth Initiative: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; pp. 1–10. Available online: https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/targeted-communities/lgbt-young-people-smoke-and-vape-higher-prevalence-non-lgbt (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Eliminating Tobacco-Related Disease and Death: Addressing Disparities—A Report of the Surgeon General; Office of the Surgeon General: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2024-sgr-tobacco-related-health-disparities-full-report.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Kava, C.M.; Soule, E.K.; Seegmiller, L.; Gold, E.; Snipes, W.; Westfield, T.; Wick, N.; Afifi, R. “Taking Up a New Problem”: Context and Determinants of Pod-Mod Electronic Cigarette Use Among College Students. Qual. Health Res. 2021, 31, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magistretti, S.; Pham, C.T.A.; Dell’Era, C. The creative process of problem framing for innovation: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2025, 42, 987–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oak, A. Performing Architecture: Talking ‘Architect’ and ‘Client’ into Being*. In About Designing; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).