Living Counter-Maps: A Board Game as Critical Design for Relational Communication in Dementia Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Relational Communication in Dementia Care

2.2. Communication Interventions: Therapy or Relationship?

2.3. Mapping and Counter-Mapping

2.4. Play as Relational Embodied Practice in Dementia Care

2.5. Critical Design Thinking and Ri&tD

2.6. Learning and Unlearning in Design for Dementia

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Participants and Setting

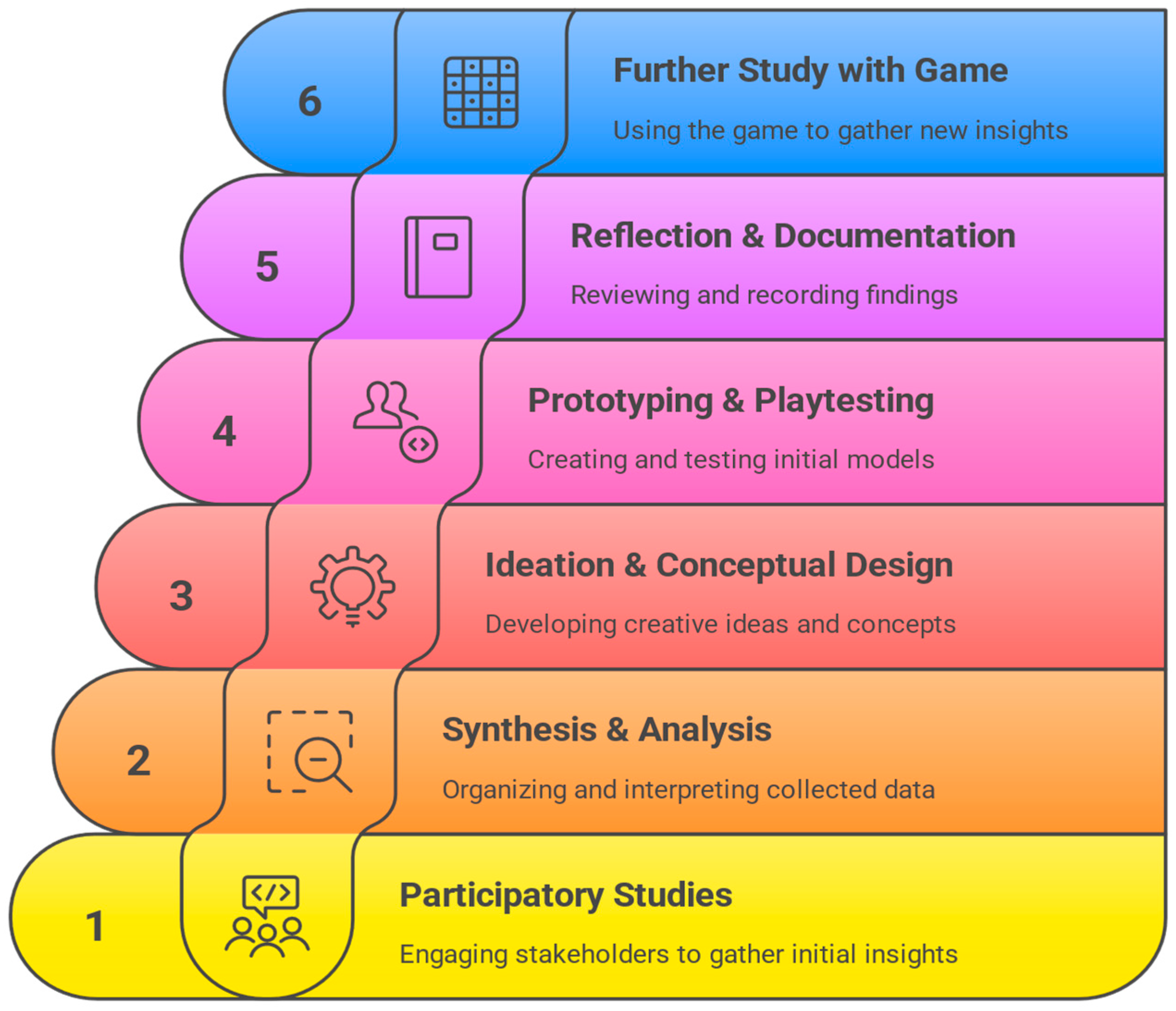

3.3. Iterative Phases of the Ri&tD Process

3.3.1. Phase 1–2: Synthesis and Analysis

- Communication was sustained through co-regulation rather than directive exchange.

- Multimodal reciprocity, gesture, gaze, rhythm, supported communication closeness even when verbal fluency fluctuated.

- Predictability and relational trust enabled meaningful participation despite cognitive variation.

- Empirical Grounding of Design Decisions

- 2.

- Embodied Co-Regulation During Interaction

- 3.

- Tactile Manipulation as a Shared Focus of Attention

- 4.

- Multimodal Prompts Shaped Confidence and Participation

- 5.

- Difficulty Shifting Between Physical and Virtual Contexts

- 6.

- Everyday Objects as Affective and Cognitive Anchors

- 7.

- Boundary Objects Facilitated Cross-Stakeholder Sense-Making

- 8.

- Comfort, Familiarity, and Material Affordances Guided Engagement

- 9.

- Multimodal, Relational Meaning-Making Spanned Both Studies

3.3.2. Phase 3: Ideation and Conceptualization

3.3.3. Phase 4–6: Prototyping, Refinement, and Evaluation

3.4. Materials

- A modular game board comprising nine Place Tiles representing neighbourhood spaces (e.g., market, library, community center).

- Activity Cards depicting everyday activities with clear iconography and minimal text.

- Special Action Tiles introduce flexibility through swapping or skipping.

- A Moodboard with six slots per player, used to curate preferred activities.

- Tactile tokens, game pieces, and dice facilitate turn-based coordination.

4. Findings and Outcomes

4.1. From Iteration to Refinement

4.2. Emerging Design Principles and Patterns of Relational Communication

- Co-regulation sustained communication more reliably than instruction: The formative studies demonstrated that PLwD engaged most successfully when interactions unfolded through mutual adjustment and shared pacing. Caregivers and facilitators often slowed gestures, mirrored movements, or paused with participants, establishing a relational rhythm. This informed the incorporation of flexible turn-taking mechanics and slow, predictable interaction cycles in Neighbourly.

- Multimodal reciprocity enabled participation when verbal fluency fluctuated: Across prototypes and empirical observation, tactile handling, rhythmic sequences, gesture, and spatial placement consistently fostered engagement. These modalities provided alternative pathways for expressing preference and emotion. Consequently, Neighbourly incorporates tactile tiles, pictorial cues, and dual-response prompts (open-ended and binary) to accommodate varied expressive capacities.

- A shared material focus anchored joint attention and supported mutual agency: When interaction centred on tangible tasks, placing tokens, arranging tiles, and manipulating objects, participants naturally coordinated with caregivers, often without needing verbal instruction. This affirmed the potential of material play as a medium for relational attunement and guided the choice of textured components, modifiable layouts, and embodied actions within the game.

4.3. The Neighbourly Prototype

5. Toward a Framework for Critical Design Thinking in Dementia Care

5.1. Research in and Through Design as Relational Inquiry

5.2. Critical Design Thinking as Situated and Ethical Practice

5.3. Communication Closeness as Relational Praxis

5.4. Methodological Challenges and Adaptations in Designing with People Living with Dementia

5.5. Living Counter-Mapping as Method and Metaphor

The Living Counter-Maps Framework

5.6. Implications and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sabat, S.R.; Harré, R. The Construction and Deconstruction of Self in Alzheimer’s Disease. Ageing Soc. 1992, 12, 443–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitwood, T. Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First; McGraw-Hill Education: Columbus, OH, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0-335-19855-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kontos, P.C. Embodied Selfhood in Alzheimer’s Disease: Rethinking Person-Centred Care. Dementia 2005, 4, 553–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydén, L.-C. Non-Verbal Vocalizations, Dementia and Social Interaction. Commun. Med. 2011, 8, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsawy, S.; Mansell, W.; McEvoy, P.; Tai, S. What Is Good Communication for People Living with Dementia? A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2017, 29, 1785–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, B.; O’Philbin, L.; Farrell, E.M.; Spector, A.E.; Orrell, M. Reminiscence Therapy for Dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, CD001120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Fields, N.L.; Highfill, M.C.; Troutman, B.A. Remembering the Past with Today’s Technology: A Scoping Review of Reminiscence-Based Digital Storytelling with Older Adults. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beukelman, D.R.; Mirenda, P. Augmentative & Alternative Communication: Supporting Children and Adults with Complex Communication Needs; Paul H. Brookes Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.; Anderson, R.A.; Pei, Y.; Xu, H.; Nye, K.; Poole, P.; Bunn, M.; Lynn Downey, C.; Plassman, B.L. Care Partner–Assisted Intervention to Improve Oral Health for Older Adults with Cognitive Impairment: A Feasibility Study. Gerodontology 2021, 38, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Gray, C.; Cox, S. The Use of Talking Mats to Improve Communication and Quality of Care for People with Dementia. Hous. Care Support 2007, 10, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemelmans, R.; Gelderblom, G.J.; Jonker, P.; De Witte, L. Socially Assistive Robots in Elderly Care: A Systematic Review into Effects and Effectiveness. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2012, 13, 114–120.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konrad, R.; Güttler, C.; Öhl, N.; Heidl, C.; Scholz, S.; Bauer, C. Effects of the Tovertafel® on Apathy, Social Interaction and Social Activity of People with Dementia in Long-Term Inpatient Care: Results of a Non-Controlled within-Subject-Design Study. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1455185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, E.N.; Savundranayagam, M.Y.; Murray, L.; Orange, J. Supportive Strategies for Nonverbal Communication with Persons Living with Dementia: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022, 136, 104365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staehler, M.; Benson, C.; Block, L.; Roberts, T.; Gilmore-Bykovskyi, A. Verbal and Nonverbal Expressions of Persons Living with Dementia as Indicators of Person-Centered Caregiving. Gerontologist 2022, 62, 1299–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluso, N.L. Whose Woods Are These? Counter-Mapping Forest Territories in Kalimantan, Indonesia. Antipode 1995, 27, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattray, N.A. Counter-Mapping as Situated Knowledge: Integrating Lay Expertise in Participatory Geographic Research. In Participatory Visual and Digital Research in Action; Routledge: Albingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 131–146. [Google Scholar]

- Dalsgaard, P. Research in and through Design: An Interaction Design Research Approach. In Proceedings of the 22nd Conference of the Computer-Human Interaction Special Interest Group of Australia on Computer-Human Interaction, Brisbane, Australia, 22–26 November 2010; pp. 200–203. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, J.; Forlizzi, J.; Evenson, S. Research through Design as a Method for Interaction Design Research in HCI. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 28 April–3 May 2007; pp. 493–502. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K.N.; Herman, R.; Gajewski, B.; Wilson, K. Elderspeak Communication: Impact on Dementia Care. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement.® 2009, 24, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyle, W.; Bramble, M.; Jones, C.; Murfield, J. Care Staff Perceptions of a Social Robot Called Paro and a Look-Alike Plush Toy: A Descriptive Qualitative Approach. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguzzoli Peres, F.; Haas, A.N.; Martha, A.D.; Chan, M.; Steele, M.; Ferretti, M.T.; Ngcobo, N.N.; Ilinca, S.; Domínguez-Vivero, C.; Leroi, I.; et al. Walking the Talk for Dementia: A Unique Immersive, Embodied, and Multi-Experiential Initiative. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 2309–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huizenga, J.; Scheffelaar, A.; Bleijenberg, N.; Wilken, J.P.; Keady, J.; Van Regenmortel, T. What Matters Most: Exploring the Everyday Lives of People with Dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2023, 38, e5983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- zu Verl, C.M. Dementia, Bodies and Technologies of the We. In Video-Analysis and Knowledge on Rewind: Contributions to Social Theory and the Sociology of Knowledge; Knowledge, Communication and Society; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2025; ISBN 978-1-040-38720-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ridder, H.M.; Anderson-Ingstrup, J.; Krøier, J.K.; McDermott, O. Reciprocity and Caregiver Competencies.: An Explorative Study of Person-Attuned Interaction in Dementia Care. Qual. Stud. 2024, 9, 109–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, E.; Olaison, A. “I See What You Mean”—A Case Study of the Interactional Foundation of Building a Working Alliance in Care Decisions Involving an Older Couple Living with Cognitive Decline. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Steen, J.T.; van der Wouden, J.C.; Methley, A.M.; Smaling, H.J.; Vink, A.C.; Bruinsma, M.S. Music-Based Therapeutic Interventions for People with Dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2025, CD003477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, L.F.; Schenk, F. Unpacking the Cognitive Map: The Parallel Map Theory of Hippocampal Function. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 110, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stufflebeam, S.M.; Rosen, B.R. Mapping Cognitive Function. Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am. 2007, 17, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzálvez-García, F.; Butler, C.S. Mapping Functional-Cognitive Space. Annu. Rev. Cogn. Linguist. 2006, 4, 39–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, E.; Stappers, P.J. Co-Creation and the New Landscapes of Design. CoDesign 2008, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruitenburg, Y.; Lee, M.; Markopoulos, P.; Ijsselsteijn, W. Evolving Presentation of Self: The Influence of Dementia Communication Challenges on Everyday Interactions. In Proceedings of the 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 11–16 May 2024; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, R.; Hendriks, N.; Wilkinson, A.; Bartels, S.L. Artefacts in Action: Facilitating Positive Person Work in Dementia Group Living Environment. In Proceedings of the Dementia Lab Conference, Aveiro, Portugal, 12–14 March 2025; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Moyle, W.; Cooke, M.; Beattie, E.; Jones, C.; Klein, B.; Cook, G.; Gray, C. Exploring the Effect of Companion Robots on Emotional Expression in Older Adults with Dementia: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2013, 39, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czech, E.; Shibasaki, M.; Tsuchiya, K.; Peiris, R.; Minamizawa, K. Multi-Modal Design to Promote Social Engagement with Dementia Patients. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE World Haptics Conference (WHC), Tokyo, Japan, 9–12 July 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Huizenga, J.; Scheffelaar, A.; Fruijtier, A.; Wilken, J.P.; Bleijenberg, N.; Van Regenmortel, T. Everyday Experiences of People Living with Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizinga, J. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Caillois, R. Man, Play, and Games; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton-Smith, B. The Ambiguity of Play; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Whitbourne, S.K.; Ellenberg, S.; Akimoto, K. Reasons for Playing Casual Video Games and Perceived Benefits among Adults 18 to 80 Years Old. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2013, 16, 892–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voida, A.; Carpendale, S.; Greenberg, S. The Individual and the Group in Console Gaming. In Proceedings of the 2010 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Savannah, GA, USA, 6–10 February 2010; pp. 371–380. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, R. Implementation and Impact of the Magic Table for People Living with Dementia in Care Homes and Day Services. Ph.D. Thesis, Leeds Beckett University, Leeds, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste, S.; Jouvelot, P.; Pin, B.; Péquignot, R. The MINWii Project: Renarcissization of Patients Suffering from Alzheimer’s Disease through Video Game-Based Music Therapy. Entertain. Comput. 2012, 3, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, A.; Li, M.; Qiao, R.; Omondi, V. Memorology: Multi-Sensory TangiBalls Game for Patients with Dementia; Berkeley School of Information: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jøranson, N.; Pedersen, I.; Rokstad, A.M.M.; Ihlebaek, C. Effects on Symptoms of Agitation and Depression in Persons with Dementia Participating in Robot-Assisted Activity: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, A.; Raby, F. Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-0-262-01984-2. [Google Scholar]

- Dunne, A.; Raby, F. Not Here, Not Now: Speculative Thought, Impossibility, and the Design Imagination; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Fry, T. Design Futuring; University of New South Wales Press: Sydney, Australia, 2009; pp. 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Manzini, E. Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza-Chock, S. Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hydén, L.-C. Cutting Brussels Sprouts: Collaboration Involving Persons with Dementia. J. Aging Stud. 2014, 29, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaver, W. What Should We Expect from Research through Design? In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Austin, TX, USA, 5–10 May 2012; pp. 937–946. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, S.; Blackler, A.; Popovic, V. Intuitive Interaction in a Mixed Reality System. In Proceedings of the Design Research Society, Brighton, UK, 27–30 June 2016; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, S.; Blackler, A.; Fels, D.; Astell, A. Supporting People with Dementia—Understanding Their Interactions with Mixed Reality Technologies. In Proceedings of the DRS2020, Brisbane, Australia, 11–14 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, S.; Mutsuddi, R.; Astell, A.J. Enhancing Prompt Perception in Dementia: A Comparative Study of Mixed Reality Cue Modalities. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1419263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, S.; Ong, J.; Fels, D.; Astell, A. Sound Mixed Reality Prompts for People with Dementia: A Familiar and Meaningful Experience. In Designing Interactions for Music and Sound; Focal Press: Oxfordshire, UK, 2022; pp. 151–176. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, S.; Astell, A.J. From Participation to Justice: A Critical Co-Design Framework for Dementia Research. In Critical Methodologies in Dementia Studies; Capstick, A., Changfoot, N., McFarland, J., Eds.; Dementia in Critical Dialogues; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, L.A.; Montgomery, B.M. Relating: Dialogues and Dialectics; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kontos, P.; Miller, K.-L.; Kontos, A.P. Relational Citizenship: Supporting Embodied Selfhood and Relationality in Dementia Care. In Ageing, Dementia and the Social Mind; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Balfour, A. Developing a Relationship Intervention for Couples Living with Dementia. Ph.D. Thesis, UCL (University College London), London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, C.; Webber, R.; Livingston, G.; Beeke, S. What Are the Communication Guidelines for People with Dementia and Their Carers on the Internet and Are They Evidence Based? A Systematic Review. Dementia 2025, 24, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haraway, D.J. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Buse, C.; Martin, D.; Nettleton, S. Materialities of Care: Encountering Health and Illness through Artefacts and Architecture; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Desai, S.; Peris, S.; Saraiya, R.; Remesat, R. Living Counter-Maps: A Board Game as Critical Design for Relational Communication in Dementia Care. Societies 2025, 15, 347. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120347

Desai S, Peris S, Saraiya R, Remesat R. Living Counter-Maps: A Board Game as Critical Design for Relational Communication in Dementia Care. Societies. 2025; 15(12):347. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120347

Chicago/Turabian StyleDesai, Shital, Sheryl Peris, Ria Saraiya, and Rachel Remesat. 2025. "Living Counter-Maps: A Board Game as Critical Design for Relational Communication in Dementia Care" Societies 15, no. 12: 347. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120347

APA StyleDesai, S., Peris, S., Saraiya, R., & Remesat, R. (2025). Living Counter-Maps: A Board Game as Critical Design for Relational Communication in Dementia Care. Societies, 15(12), 347. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120347