Abstract

The aim of the proposed study is to present the partial results of research activities focused on vocational school teachers’ resilience realized within the grant project IGA003DTI/2022. The present study aims to examine the existence of associations between teacher resilience and years of teaching experience. The research sample consisted of 474 vocational school teachers in Slovakia. The level of their teacher resilience was measured by The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale CD-RISC-25SLOVAK. The scale measures seven dimensions—Hardiness, Coping, Adaptability/Flexibility, Meaningfulness/Purpose, Optimism, Regulation of emotion and cognition, and Self-Efficacy. The findings confirmed the existence of associations between teacher resilience and years of teaching experience as novice teachers and teachers with ten or fewer years of teaching experience achieved lower scores in the scale than their more experienced colleagues. Although we are aware of the limits of the research study given the size and composition of the sample, the findings suggest that years of teaching experience can be considered an important variable from the aspect of teacher resilience and it is important to pay increased attention especially to novice teachers’ well-being and building their resilience, e.g., by providing guidance through developing effective coping strategies. As there are a lack of available data on vocational school teachers’ resilience, the present findings have the potential to broaden the existing knowledge and have implications for further research.

1. Introduction

The concept of human resilience points to the indicators of life adaptation, including the field of work. In the context of the teaching profession, it can be assumed that resilience as an individual’s characteristic can have a significant impact on a teacher’s career path and can contribute to the decision of whether to leave the teaching profession or to remain in the school system despite the presence of a whole range of stressors. Resilience is important also from the aspect of coping with demanding tasks and fulfilling the requirements asked of teachers in such complex organizations [1] as schools undeniably are [2]. Mansfield et al. [3] accentuate that resilient teachers are able to take advantage of their individual characteristics, as well as of the occurring situations, in order to deal with challenges and to achieve professional/job satisfaction contributing to their well-being.

In schools, there is a range of factors that have an impact on teachers’ motivation, their activities in the classroom, and their students’ performance—including stress, which is defined by WHO [4] as a “state of worry or mental tension caused by a difficult situation”. Teacher stress—as a specific type of occupational stress occurring in the context of the teaching profession—can be defined as negative physical and psychological responses to a variety of events pertaining to a teacher’s job caused by an imbalance between risk and protective factors [5], which means that when stressful situations occur, increased demands are placed on a person’s adaptive capacity [6] and there is an inconsistency between society’s expectations and requirements on one hand and the educational reality on the other hand [7]. Kyriacou [8] identified three types of stress in teachers’ work—1. stress stemming from work requirements; 2. stress as an emotional and behavioral response to pedagogical situations; and 3. Stress as transaction between teachers’ resources and demands.

Several research studies have been carried out on specific sources of teacher stress, e.g., Průcha, Walterová, and Mareš [9] identified the following nine factors: 1. students’ negative attitude towards learning; 2. behavior issues in the classroom that were also confirmed in the TALIS 2018 survey, according to which 18% of teachers reported experiencing stress frequently [10]; 3. curricular changes; 4. frequent organizational changes; 5. unfavorable conditions in the workplace; 6. a lack of opportunities for career advancement; 7. a lack of time; 8. conflicts between colleagues, and 9. a lack of recognition. Harmsen et al. [11] also include work requirements, conflict of roles, role ambiguity, lack of autonomy, and poor school ethos among the most frequently occurring sources of teacher stress, while Stapleton, Garby, and Sabot [12], Mark and Smith [13] and Leher, Hillert, and Keller [14] draw attention to the perceived lack of balance between teachers’ effort and remuneration. In the context of classroom management, other factors related to managerial stress, such as exhaustion, emotional distress, and conflicts between the demands placed on teachers at work and in their private lives also occur (for more details, see Richardsen and Matthiesen [15]).

As confirmed by TALIS 2018 results, teacher stress and stressors in schools are considered a serious issue by teachers [16]. They are associated with teachers’ job dissatisfaction, which plays an important role from the aspect of teachers’ decision to remain in the teaching profession or to find a job outside the school system. Ingersoll’s [17] findings show that constant challenges and stressors in the school environment are the reason for changing occupation in the case of teachers with fewer than ten years of experience.

Hennig and Keller [18] categorized sources of teacher stress into 1. psychological—related to teachers’ cognition, emotions, and situations subjectively experienced as stressful—e.g., personality traits, coping strategies, resilience, etc.; 2. physical—e.g., unhealthy lifestyle, injury, or serious disease; 3. institutional—e.g., working conditions, workload, relationships, autonomy, professional development, and career advancement; and 4. social—e.g., family background, media, social status, etc.

1.1. Teacher Stress in the Context of Vocational Schools

Vocational school teachers are confronted with some additional sources of stress when compared with their colleagues in other types of secondary schools, i.e., secondary grammar schools. This is due to the fact that a decrease in students’ interest in VET has been observed during the last decades and studying at a vocational school is usually not the applicants’ first choice. Therefore, in Slovakia, in certain cases, carrying out selection of students is impossible and schools must also recruit poor-performing students and subsequently, motivate them to learn. Moreover, available research results shows that, for the above reasons, working with vocational school students is more demanding compared with students in other types of schools [19].

Gonon [20] claims that vocational subject teachers, particularly teachers working in schools with dual VET, are the most impacted by specific requirements placed on them—i.e., to keep pace with the newest developments in a particular field; develop their knowledge, skills, and competencies related to the vocational subject they teach; and find links between theory and practice—as their students are confronted with the reality at workplaces as soon as during their studies. Moreover, especially vocational subject teachers feel pressure from the educational system, but also from the labor market, as their requirements are often conflicting. According to Adams [21], the highest levels of stress are experienced by vocational school teachers who do not feel sufficiently prepared for performing their job.

In their research studies, Kärner et al. [22], Kärner and Höning [23], and Sappa, Aprea, and Barbarasch [24] focused on specific sources of teacher stress in vocational schools and they identified heavy workload, performance pressure, factors interrupting the natural workflow, tight deadlines, conflicts at the workplace, and vocational school teachers’ administrative burden. Boldrini, Sappa, and Aprea [25]—alongside factors reported by other groups of teachers—identified factors such as teachers’ frustration from students’ weak motivation to study in vocational schools, immaturity of students, and challenges related to teaching vocational subjects. Kärner et al. [22] also included behavior issues in the classroom, conflicts between students, between teachers and students, and the heterogeneous composition of classes among the above factors.

1.2. Coping

When defining coping, most frequently, the relatively old definition by Lazarus and Folkman [26] is used, according to which coping means “constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person”. Coping represents an adaptive force that helps individuals act constructively even in demanding situations [27]. Lazarus [28] considers coping a conscious process of overcoming distress, which plays the role of a mediator between a stressful situation and an individual’s response, and is a determinant of the degree of the individual’s adaptation to particular circumstances. According to Voitenko et al. [29], insufficient adaptation to distress is related to a lack of a flexible system of coping strategies appropriate for a certain situation and its circumstances, as well as an individual’s abilities. Coping strategies can be defined as ways of overcoming adversity, certain patterns of behavior, which are used when dealing with demanding situations. Coping strategies can be developed, extended, and supplemented based on newly gained experiences since for handling a new situation, the existing coping strategies are not necessarily effective.

Coping strategies can be considered a potential resource that can be used for dealing with adversity when performing any profession with the aim to achieve an optimal level of mental functioning (problem solving, positive reassessment, seeking help, etc.) [30]. Lazarus [31] divided coping strategies into two categories—1. problem-focused coping strategies and 2. emotion-focused coping strategies. A third category also exists—the group of the so-called maladaptive coping strategies, e.g., escape or self-blame, but other ineffective or even harmful strategies, such as substance abuse, avoidance, procrastination, self-harm, etc. can also be used. Maladaptive coping strategies can lead to psychosomatic problems, emotional exhaustion, job dissatisfaction, depression, or anxiety [12,30].

Brandtstädter [32] uses the notion of coping processes and distinguishes between assimilative and accommodative processes. While by using assimilative processes, individuals try to change the current situation and life conditions in compliance with their goals, accommodative processes help individuals adapt their personal goals to the existing circumstances. Earlier, Brandtstädter and Greve [33] mentioned a third type of process—immunization—when individuals deny the existence of a problem. Despite using different terminology, it can be assumed that this classification of coping processes is similar to the above-mentioned Lazarus’s [31] categorization of coping strategies.

Ungar et al. [34] carried out a research study on overcoming stress. They identified a three-phase reciprocal process that individuals typically apply when facing harsh circumstances. In the first phase, individuals rely on their own resources and try to solve problems without any external help. This coping strategy can be functional only if the intensity of the burden is weak or moderate. If it comes to an increase in the intensity of stress related to a particular issue or it is a complex situation, to successfully adapt, it is important to select from among available alternative strategies. In the second phase, if the first strategy is shown to be ineffective and the individual is not able to solve the problem without using external help, they should be ready to accept help from significant others. In some cases, individuals get to the stage when institutional help is needed. If this is the case, it is crucial to recognize that without professional help, there is an increased probability of failure.

In everyday situations, it can be observed that there is a group of individuals who are able to deal with harsh circumstances with an ease, but others have problems with handling even much simpler situations, which are subjectively perceived by them as demanding or exceeding their limits. The degree to which individuals can adapt to adverse situations is influenced by several factors, including:

- coping strategies at an individual’s disposal at a certain point in time;

- the extent to which the existing coping strategies are appropriate for a particular situation;

- an individual’s ability to cope with stress, i.e., resilience [35,36].

1.3. Coping Strategies Applied by Teachers

For dealing with stress and negative emotions, teachers use a variety of more or less functioning coping strategies. As research results show, they often experience anxiety or even anger stemming from behavior issues in the classroom and other demanding pedagogical situations. As accentuated by Wang, Lee, and Hall [37], selecting appropriate coping strategies is important as they are sources of positive emotions, prevent exhaustion, and contribute to teachers’ mental well-being. On the other hand, inappropriate coping strategies evoke negative emotions, increase stress levels, and thus, can have a negative impact on individuals’ mental health. It must be pointed out that it is not possible to categorize certain coping strategies as effective or ineffective as their appropriateness is situationally bound and their application depends on a particular teacher’s personality, experiences, available scale of coping strategies, etc.

Boon [2] claims that experiencing stress, insufficient attention paid to well-being, or other mental processes that teachers perceive as sources of dissatisfaction with their working conditions leading to leaving the teaching profession are associated with burnout or an inability to apply effective coping strategies. Montgomery [38] focused on the role of coping in the context of teacher stress and found out that coping strategies regulate the relationship between stressors and burnout by decreasing the impact of stressors. His results also showed that teacher stress in combination with an inability to cope is associated with adversity, such as burnout, low self-efficacy, poor classroom management, students’ underachievement, and depression symptoms, but problems can also be observed in building relationships and teachers’ communication with their students’ parents [39].

Chang [40], in agreement with the above categorization by Lazarus [31], applied the specified types of coping strategies to teachers. Teachers use problem-focused strategies to solve a particular situation when they subjectively evaluate it as difficult to cope with and they ask for advice or help from colleagues that have already experienced such an adversity. It is a different situation when teachers seek psychological and mental support from their colleagues, which does not help them solve the problem, but it can make them feel better—i.e., they apply emotion-focused coping strategies. Escape as an ineffective coping strategy is used when a teacher gives up and resigns, e.g., leaving the teaching profession means using escape as a coping strategy and Marais-Opperman, Rothmann, and Van Eeden [41] consider it the final phase of the decision-making process related to changing jobs.

1.4. Teacher Resilience

There are several definitions of teacher resilience in available literature. Clarà [42] defines teacher resilience as positive adaptation in a demanding situation. Gu and Day [43] provide a more detailed description and define teacher resilience as a teacher’s ability or capacity to deal with an unavoidable level of uncertainty in the educational reality and to maintain balance, sense of duty, and focus. Gu [44] emphasizes the dynamic character of teacher resilience. Mansfield et al. [3] point out that teacher resilience is not exclusively an ability or a process, but an output. In compliance with the above definitions, teacher resilience can be considered a progressive competence, the capacity of an individual to maintain mental health and normal functioning in the context of challenges or significant adversity (stress).

Kärner et al. [45]—in the context of resilience—use the notion of resilience competencies. They define them as individuals’ ability to cope with job-related requirements and to maintain health, which they explain by the fact that resilience can be developed. These competencies have three dimensions—flexibility (ability to adapt); dynamics (openness to changes); and resistance (ability to recover quickly).

Research has confirmed the existence of associations between teacher resilience on one hand and the effectiveness of teachers’ educational work, their job satisfaction, and self-efficacy on the other hand [46]. In their research studies, Pretsch, Flunger, and Schmitt [47], as well as Kärner et al. [45], found statistically significant correlations between teacher resilience and their job satisfaction. Alongside that, the level of teachers’ resilience is determined by a range of factors, e.g., coping strategies, social competencies, teaching skills and competencies, as well as personal characteristics—altruism, enthusiasm, emotional stability, and optimism. From the aspect of the work environment, providing teachers with support from the school leader is important, as well as enabling contact with a mentor, peers, colleagues, family, and friends, which, in general, can be included among protective factors [48]. Ainsworth and Oldfield [49] also point out the importance of external factors from the aspect of teacher resilience and accentuate that in the process of developing resilience in teachers, it is necessary to pay sufficient attention to improving the quality of their work environment. Support by the school management, reasonable workload, a positive school culture characterized by collaboration between teachers, and positive social relationships at the workplace have a big role to play as well. These ecological factors having an impact on teachers’ adaptation to the changing environment and on teacher resilience are highlighted by other authors, too. They mention determinants such as school culture [50], teachers’ participation in decision making [51], positive relationships between teachers and the school management [52], mentoring relationships with colleagues, and mutual support [53].

In their research study, Drew and Sosnowski [46] identified the following characteristics associated with teacher resilience:

- Resilient teachers are rooted in their school community, which helps them react to challenges effectively. They have an overview of risk factors and they can benefit from protective factors.

- Resilient teachers can better cope with uncertainty and turn negative circumstances to experiences that they can learn from. Such transformation helps teachers gain strength to maintain balance between risk and protective factors.

- Resilient teachers use relationships with their colleagues, students, and the school management as resources helping them to overcome adversity.

In the field of teacher resilience, no available research studies have targeted teachers not being able to cope with adversity related to performing their job, but they have studied mainly successful teachers and investigated the factors helping teachers overcome difficulties and thus, promoting their professional development instead of only surviving [48].

2. Present Study

In the last decades, numerous research activities have been carried out in the field of education examining resilience from various aspects, but most of them have focused on the target groups of children and adolescents [54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71]. Recently, teacher resilience has also been dealt with by experts from diverse countries, but vocational school teachers’ resilience remains an internationally neglected field of research. Even though vocational subject teachers form a specific group of teachers also facing additional challenges and different, context-specific situations when compared with their colleagues in other types of schools, following a thorough literature review, it can be assumed that there is no available research study on vocational school teachers’ resilience and international studies are rare. As a reaction to this situation, the aim of the grant project IGA003DTI/2022 Vocational School Teachers’ Resilience is to investigate the issues of vocational school teachers’ resilience, to find out about their resilience levels, and to examine their associations with selected variables. The team of investigators aims to fill in the gap in the field of available information about the resilience levels of this specific target group and to contribute to current knowledge in this under-explored area. It is important to carry out research on vocational school teachers’ resilience in order to gather data that can serve as a basis for developing pre-service and in-service teacher training programs, as well as for implementing measures at national and school levels tailored to their needs.

In the present study, the partial results of the above grant project under realization are presented with a focus on the level of vocational school teacher’s resilience from the aspect of the length of their teaching experience. As discussed in the literature review, novice teachers and teachers with fewer than five years of teaching experience the highest levels of stress and the most experienced teachers are at the highest risk of burnout, but there are certain factors that help prevent negative outcomes despite the presence of cumulative risk factors. It can be presumed that resilience is one among the determinants of success or failure. Moreover, as teachers are permanently confronted with new situations, their scale of coping strategies broadens during their teaching practice, which makes them more resistant to stress, and they can face adversity with no or less harm. In this context, it is interesting to find out about the levels of resilience characteristic of various periods of time during their career paths. Therefore, in the hypothesis, the existence of statistically significant differences in the achieved scores for The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale CD-RISC-25SLOVAK according to the variable years of teaching experience was presumed.

3. Methods

Within an international grant project (no. IGA003DTI/2022 Vocational School Teachers’ Resilience), an investigation into vocational school teachers’ resilience and the factors associated with it—including years of teaching experience—was carried out in the Slovak Republic. For the purposes of the research study, The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) was applied. The questionnaire was developed by Kathryn M. Connor and Jonathan R. T. Davidson primarily for use with adult samples, but it can be applied with respondents of different age groups. The instrument measures individuals’ resilience level (high, medium, low) and provides useful data about coping with stress, for planning treatment and psychotherapy, fostering resilience, etc.

There are three available versions of the Scale—CD-RISC 25 and its shorter versions CD-RISC 10 and CD-RISC 2. In the study, the approved Slovak version of the original 25-item scale was used. Since the copyright does not allow reproducing the scale, in the study, only individual dimensions and not questionnaire items are addressed.

The CD-RISC 25 consists of 25 5-point Likert scale items. The respondents are requested to respond to situations with reference to the previous month. In the case that it is not possible, they indicate how they would have reacted if such a situation had occurred. The items are scored from 0 to 4 (0—not true at all, 1—rarely true, 2—sometimes true, 2—often true, and 4—true nearly all of the time) and the total of all items ranges between 0 and 100. The higher the score is, the higher an individual’s resilience is.

The scale measures five factors—1. personal competence, high standards, and tenacity; 2. trust in one’s instincts, tolerance of negative affect, and strengthening effects of stress; 3. positive acceptance of change and secure relationships; 4. control; and 5. spiritual influences.

The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale CD-RISC-25 examines the following dimensions: Hardiness (H); Coping (C); Adaptability/Flexibility (A); Meaningfulness/Purpose (M); Optimism (O); Regulation of emotion and cognition (R); and Self-Efficacy (S-E). In the context of the present research study, hardiness is defined as not giving up when facing significant adversity, which is characterized by endurance, tenacity, and the belief that individuals can control what is happening around them; coping is understood as an intentional dynamic process of managing harsh circumstances; adaptability/flexibility is reflected in the ability to create a balance between teachers’ needs and social requirements; meaningfulness/purpose means positive, pro-active behavior which is helpful in adapting individuals’ work environment to the changing circumstances; optimism is a positive personality trait or positive attunement, anticipation of success, which is relatively stable in time and is associated with motivation; regulation of emotion and cognition represents teachers’ ability to prevent negative emotions and anxiety by understanding relationships based on the interpretation of own behavior or others’ actions; and self-efficacy is used as belief in own abilities to meet challenges.

In the first phase of the conducted research study, the construct validity of The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale CD-RISC-25SLOVAK for the sample of Slovak vocational school teachers was tested by means of factor analysis. The obtained data’s suitability for factor analysis was confirmed by the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value 0.785. The results of the Barlett’s test of sphericity (χ2 = 0.794, significance 0.000) are significant and confirm the existence of correlations between items. The extracted seven factors explain 71.47% of cumulative variance (see Table 1).

Table 1.

The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale CD-RISC-25SLOVAK—extracted factors.

Based on the carried out statistical analysis, the validity and reliability of The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale CD-RISC-25SLOVAK were confirmed for the sample of Slovak vocational school teachers. The research sample consisted of 474 Slovak vocational school teachers (see Table 2)—282 (59.49%) female and 192 (40.51%) male teachers. Based on the years of teaching experience, the following groups of teachers were identified: 0–2 years—177 teachers (37.34%); 3–10 years—117 teachers (24.68%); 11–20 years—54 teachers (11.39%); 21–30 years—75 teachers (15.82%); and 31 or more years—51 teachers (10.76%).

Table 2.

Composition of the sample—years of teaching experience.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All the respondents participated in the study voluntarily and informed consent was obtained from them. All the gathered data were anonymized. The study was approved by The Board for Internal System of Quality Assurance of DTI University, Slovakia, in compliance with the Code of Ethics of DTI University, Slovakia.

4. Results

In the hypothesis, the existence of statistically significant differences in the subscales of The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale CD-RISC-25SLOVAK according to the variable years of teaching experience was presumed. Based on the Skewness and Kurtosis values for The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale CD-RISC-25SLOVAK (Table 3), the hypothesis was tested by means of one-way ANOVA and Tukey test for post hoc comparison of differences.

Table 3.

The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale CD-RISC-25SLOVAK—Skewness and Kurtosis.

The results of the carried-out analysis confirmed the existence of statistically significant differences between the subscales of The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale CD-RISC-25SLOVAK according to years of teaching experience in the case of Hardiness, Coping, Adaptability/Flexibility, Meaningfulness/Purpose, and Optimism. In the case of Regulation of emotion and cognition and Self-Efficacy, no statistically significant differences were found (Table 4).

Table 4.

The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale CD-RISC-25SLOVAK differences between subscales according to years of teaching experience.

It is interesting to notice that all the dimensions in which significant differences according to years of teaching experience were found can be considered directly linked with the existence of adversity in the external environment surrounding teachers and the experience teachers gain not only in the context of the teaching profession, but also in their personal lives outside the school. In the case of the dimensions Regulation of emotions and cognition and Self-efficacy, it can be assumed that they are associated with individuals’ internal characteristics, certain predispositions that are less influenced by external conditions and more difficult to change or develop when compared with the dimensions of Hardiness, Coping, Adaptability/Flexibility, Meaningfulness/Purpose, and Optimism either intentionally through learning or unintentionally as a result of gaining experience.

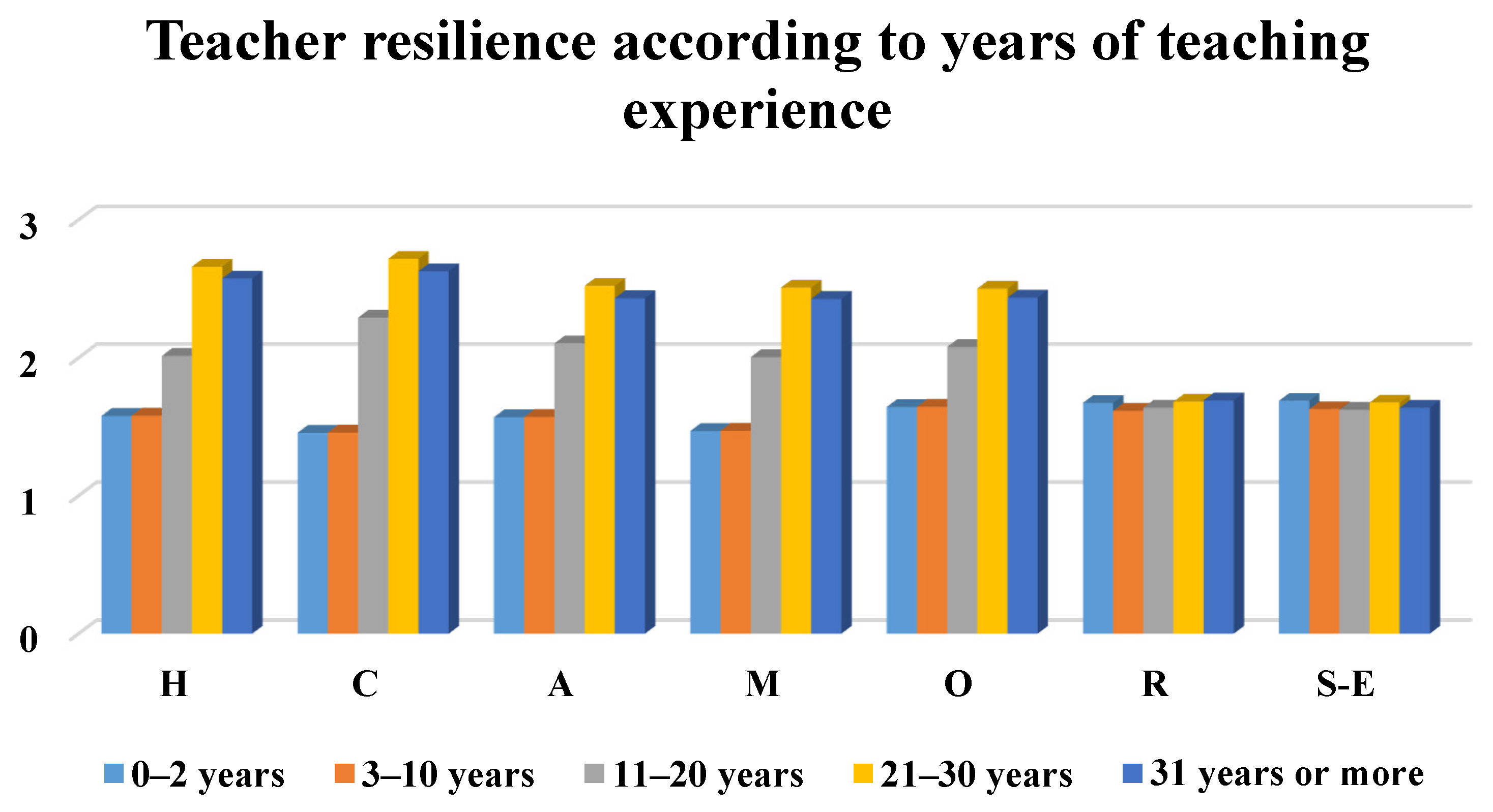

In the next phase of data analysis, the scores for individual subscales (dimensions) were compared. As the data in Table 5 show, in each of the subscales Hardiness, Coping, Adaptability/Flexibility, Meaningfulness/Purpose, and Optimism, the highest scores were achieved by teachers with teaching experience ranging between 21 and 30 years and the scores were the lowest in the case of teachers with years of teaching experience ranging between 0 and 10 years.

Table 5.

Comparison of the subscales of The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale CD-RISC-25SLOVAK according to years of teaching experience.

The above results according to years of teaching experience are—for better visualization—also displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Teacher resilience according to years of teaching experience.

An interesting phenomenon can be observed in Figure 1—there is a slight decrease in the scores in all subscales except the subscale Regulation of emotion and cognition in the case of teachers with 31 or more years of teaching experience when compared with teachers with teaching experience ranging between 21–30 years, which could be associated with tiredness or exhaustion, but it must be noted that if the scores achieved by teachers with 0–10 years of teaching experience are considered, the values in the first five subscales (Hardiness, Coping, Adaptability/Flexibility, Meaningfulness/Purpose, and Optimism) are still relatively high values. In the dimensions Regulation of emotion and cognition and Self-efficacy, respondents—regardless the length of their teaching experience—achieved similar scores. Another interesting fact is that in the first five dimensions (Hardiness, Coping, Adaptability/Flexibility, Meaningfulness/Purpose, and Optimism), in the case of teachers with 0–2 years and 3–10 years of teaching experience, the achieved scores are nearly identical, while in the case of all the mentioned subscales, there was a significant jump in teachers with teaching experience between 11 and 20 years and another significant jump in respondents with 21–30 years of teaching experience.

Based on the almost identical scores for the groups of teachers with 0–2 years and 3–10 years of teaching experience in the first five dimensions of the scale, for which the existence of statistically significant differences was confirmed, for the purposes of further data analysis and interpretation of results, they can be considered one group.

In compliance with the presented results of analysis, the formulated hypothesis, in which the existence of statistically significant differences in the achieved scores for The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale CD-RISC-25SLOVAK according to the variable years of teaching experience was presumed, was confirmed. It can be assumed that teachers’ resilience levels increase with years of teaching experience and so, teachers’ sensitivity to risk factors and their impact on their professional performance, as well as well-being, decreases.

The above-described situation requires changes on both national and school levels as there is a need for developing programs fostering resilience in teachers. As confirmed by our findings, novice teachers and teachers with fewer than 10 years of teaching experience represent the most vulnerable group of teachers, therefore it is important to start with promoting professional resilience as soon as during university studies. In this context, high-quality mentoring programs for novice teachers are important, but also opportunities to take part in relevant and effective in-service training programs have a big role to play. Promoting resilience as a form of burnout prevention should be focused on, especially in the case of experienced teachers. All these measures leading towards increased levels of vocational subject teachers’ resilience can result in higher teacher job satisfaction levels, better job performance, an increased quality of vocational education and training, decreasing teacher fluctuation in schools, and keeping young teachers in the school system.

5. Discussion

Vocational school teachers’ resilience is a neglected field of research and there is a lack of available research studies dealing with issues related to it in international resources. Therefore, the opportunities for confronting the obtained results with other research studies is limited, resources focusing on teacher resilience in general or on other specific groups of teachers can be worked with.

The purpose of the present research study was to fill the gap in available resources and to investigate the issues of vocational teachers’ resilience levels, factors having an impact on their resilience, and to examine the associations between teacher resilience and years’ of teaching practice. The key finding is that years of teaching experience can be considered an important variable from the aspect of teacher resilience, which confirms the presumption that teachers with more years of teaching experience have a broader scale of coping strategies than their less experienced colleagues. This is due to the fact that they have had more opportunities to develop them when facing demanding pedagogical situations (see also [17]). This could suggest that experienced teachers are more resistant to adversity, which is in line with research results showing that novice teachers leave the teaching profession most frequently [72]. However, these findings only apply to the first five dimensions of The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale CD-RISC-25SLOVAK—Hardiness, Coping, Adaptability/Flexibility, Meaningfulness/Purpose, and Optimism, which suggests that years of teaching experience can have an impact on the dimensions of resilience that can be developed and are associated with the presence of risk factors in teachers’ environment. On the other hand, resilience dimensions impacted by teachers’ personality traits and innate characteristics (Regulation of emotion and cognition, and Self-efficacy) do not change significantly in the course of teachers’ career paths.

It must be also mentioned that teachers with many years of teaching experience are at the highest risk of burnout—some research evidence shows that there is an association between years of teaching experience and teachers’ exhaustion (or even burnout) [73,74,75,76], which can have a significant impact on teachers’ job satisfaction [77,78] and perception of the quality of school climate, but can also lead to problems with dealing with distress. Although there is a lack of studies focusing on the associations between teacher resilience and teaching experience, in the studies by Chu and Liu [79] and Ergün and Dewaele [80], where also the variable of teaching experience was examined, no significant link between teacher resilience and teaching experience was found.

From a different perspective, in the present study, in The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale CD-RISC-25SLOVAK, the highest scores were achieved by teachers with teaching experience ranging between 21 and 30 years and it came to a not significant, but still observable, decrease in the case of teachers with 31 or more years of teaching experience. The achieved scores were the lowest in the case of teachers with years of teaching experience ranging between 0 and 10 years. These findings, similarly to other research studies, suggest that novice teachers experience higher levels of distress than their experienced colleagues (see also [81,82]) and do not have such a broad scale of coping strategies for dealing with a variety of demanding pedagogical and non-pedagogical situations in the workplace. Another explanation is that the most vulnerable novice teachers leave schools during the first 10 years of their teaching practice and only teachers with higher degrees of resilience remain in schools (see [72]). Therefore, it can be assumed that in the group of teachers with 11 or more years of teaching experience, there are fewer teachers who consider teaching extremely stressful than in the group of novice teachers since those have already left the system.

In the subscales Hardiness, Coping, Adaptability/Flexibility, Meaningfulness/Purpose, and Optimism, the results of international research studies conducted on samples of teachers from various types of schools were confirmed. The findings also indicate that vocational school teachers with shorter teaching experience subjectively experience higher levels of distress when compared with their experienced colleagues [72]. Along with a longer time span spent working in the system of education providing space for developing a broader scale of coping strategies, another explanation for this phenomenon is that teachers considering their jobs extremely stressful leave or plan to leave schools during the first five years of their teaching practice [16,72].

The findings indicate that teachers with varying lengths of teaching practice have diverse needs for the content of training programs and other activities focusing on developing teachers’ resilience and promoting their well-being; and there is a strong need for implementing targeted measures to keep teachers, especially the young ones, in the teaching profession.

6. Conclusions

Vocational school teachers’ resilience is a neglected field of research in Slovakia and there is no available study on the associations between teacher resilience and years of teaching experience. By carrying out research activities in the framework of the international grant project IGA003DTI/2022 Vocational School Teachers’ Resilience, the authors aim to react to the existing lack of information and available data in the field. In the present study, as it was presumed, the main findings suggest that years of teaching experience can be considered an important variable from the aspect of teacher resilience, which was also confirmed in five of the seven tested dimensions. Even though it appears that significant differences were confirmed in the dimensions related to external risk factors, there is no proof of it and further investigation in the field is needed.

As for the composition of the sample according to years of teaching experience, experienced teachers—although they are at the highest risk of burnout—achieved statistically significantly higher scores in The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale CD-RISC-25SLOVAK than teachers with teaching experience ranging between 1 and 10 years in five of the seven dimension of the scale. In this context, the question of whether it is caused by a broader developed scale of coping strategies or whether there are other factors that play an important role also arises and has implications for further research.

The findings also suggest that novice teachers experience higher levels of stress than their experienced colleagues, which explains the fact that many of them leave the educational system at an early stage of their career. As there is a shortage of qualified teachers in Slovakia, school leaders and the government should implement measures to keep this group of teachers in schools, including innovations in undergraduate teacher training focusing on how to handle demanding pedagogical situations in schools or how to deal with conflicts in the classroom and between colleagues. Moreover, in the case of all in-service teachers, increased attention should be paid to their well-being. For novice teachers, effective mentoring programs should be offered where mentors provide novice teachers with guidance, help, and support. In addition, in-service training opportunities should be provided to all teachers and a positive organizational climate promoting favorable relationships in the workplace should be built to increase teachers’ engagement and job satisfaction.

Despite the limits of the research given by the size and the composition of the sample, which does not allow generalizing the obtained results to the entire population of vocational school teachers, the present findings have the potential to broaden existing knowledge and have implications for conducting further research in the field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B., G.G., L.H., S.K. and D.B.; methodology, L.H.; software, L.H.; validation, S.B., S.K., G.G., L.H. and D.B.; formal analysis, S.B., G.G., L.H., S.K. and D.B.; investigation, S.B., G.G., S.K. and D.B.; resources, S.B.; data curation, L.H. and S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B.; writing—review and editing, G.G., L.H., S.K. and D.B.; visualization, S.B.; supervision, S.K., L.H. and G.G.; project administration, S.B.; funding acquisition, G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by DTI University, Dubnica nad Váhom, Slovakia, grant number IGA003DTI/2022 Vocational School Teachers’ Resilience.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by The Board for Internal System of Quality Assurance of DTI University, Slovakia, in compliance with the Code of Ethics of DTI University, Slovakia (protocol code: RK/2/31/01/2022, date of approval: 31 January 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Athota, V.S.; Budhwar, P.; Malik, A. Influence of personality traits and moral values on employee well-being, resilience and performance: A cross-national study. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 69, 653–685. [Google Scholar]

- Boon, H.J. Teachers’ Resilience: Conceived, Perceived or Lived-In. In Cultivating Teacher Resilience—International Approaches, Applications and Impact; Mansfield, C.F., Ed.; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 263–278. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield, C.; Beltman, S.; Broadley, T.; Weatherby-Fell, N. Building resilience in teacher education: An evidenced informed framework. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 54, 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Stress. Available online: https://www.who.int//news-room/questions-and-answers/item/stress/?gclid=CjwKCAjwxaanBhBQEiwA84TVXC7c8U57962wJ7KjN6mbvWqKOCG5vbwDdL-XXTbcnqQvuoeo7ScdGRoCJqUQAvD_BwE (accessed on 24 August 2023).

- Prilleltensky, I.; Neff, M.; Bessell, A. Teacher stress: What it is, why it’s important, how it can be alleviated. Theory Pract. 2016, 55, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, D. Psychologie ve školní Praxis; Portál: Prague, Czech Republic, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Řehulka, E.; Řehulková, O. Teacher’s profession and teacher stress. In Proceedings of the 10th European Congress of Psychology, Prague, Czech Republic, 3–6 July 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou, C. Teacher stress and burnout: An international review. Educ. Res. 1987, 29, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Průcha, J.; Walterová, E.; Mareš, J. Pedagogický Slovník; Portál: Prague, Czech Republic, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. TALIS 2018 Results (Volume I): Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners; TALIS, OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Harmsen, R.; Helms-Lorenz, M.; Maulana, R.; van Veen, K. The relationship between beginning teachers’ stress causes, stress responses, teaching behaviour and attrition. Teach. Teach. 2018, 24, 626–643. [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton, P.; Garby, S.; Sabot, D. Psychological distress and coping styles in teachers: A preliminary study. Aust. J. Educ. 2020, 64, 127–146. [Google Scholar]

- Mark, G.; Smith, A.P. Occupational stress, job characteristics, coping, and the mental health of nurses. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 505. [Google Scholar]

- Leher, D.; Hillert, A.; Keller, S. What can balance the effort? Associations between effort-reward imbalance, over-commitment, and affective disorders in German teachers. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2009, 15, 374–384. [Google Scholar]

- Richardsen, A.M.; Matthiesen, S.B. Less Stress when Work Relationships Are Good. Available online: https://www.bi.edu/research/business-review/articles/2014/08/less-stress-when-work-relationships-are-good/ (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- OECD. TALIS 2018 Results (Volume II): Teachers and School Leaders as Valued Professionals; TALIS, OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll, R.M. The teacher shortage: A case of wrong diagnosis and wrong prescription. NASSP Bull. 2002, 86, 16–31. [Google Scholar]

- Henning, C.; Keller, G. Antistresový Program pro Učitele: Projevy, Příčiny a Způsoby Překonaní Stresu z Povolání; Portál: Prague, Czech Republic, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bonica, L.; Sappa, V. Early school-leavers microtransitions: Toward a competent self. Educ. Train. 2010, 52, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonon, P. Apprenticeship as a model for the international architecture of TVET. In Assuring the Acquisition of Expertise: Apprenticeship in the Modern Economy; Zhao, Z., Rauner, F., Hauschildt, U., Eds.; Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press: Beijing, China, 2011; pp. 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, E. Vocational teacher stress and internal characteristics. J. Vocat. Tech. Educ. 1999, 16, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kärner, T.; Steiner, N.; Achatz, M.; Sembill, D. Tagebuchstudie zu Work-Life-Balance, Belastung und Ressourcen bei Lehrkräften an Beruflichen Schulen im Vergleich zu anderen Berufen. Z. Berufs-. Wirtsch. 2016, 112, 270–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kärner, T.; Höning, J. Teachers’ experienced classroom demands and autonomic stress reactions: Results of a pilot study and implications for process-oriented research in vocational education and training. Empir. Res. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2021, 13, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Boldrini, E.; Sappa, V.; Aprea, C. Which difficulties and resources do vocational teachers perceive? An exploratory study setting the stage for investigating teachers’ resilience in Switzerland. Teach. Teach. 2019, 25, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sappa, V.; Aprea, C.; Barbarasch, A. Bouncing Back From Adversity: A Swiss Study on Teacher Resilience in Vocational Education and Training; The Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training: Bonn, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Holahan, C.J.; Moos, R.H. Life stressors and mental health: Advances in conceptualizing stress resistance. In Stress and Mental Health: Contemporary Issues and Prospects for the Future; Avinson, W.R., Godlib, I.H., Eds.; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 213–238. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. Emotions and interpersonal relationships: Toward a person-centered conceptualization of emotions and coping. J. Personal. 2006, 74, 9–46. [Google Scholar]

- Voitenko, E.; Myronets, S.; Osodlo, V.; Kushnirenko, K.; Kalenychenko, R. Influence of emotional burnout on coping behavior in pedagogical activity. Int. J. Organ. Leadersh. 2021, 10, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Cooper, C.; Cartwright, S.; Donald, I.; Taylor, P.; Millet, C. The experience of work-related stress across occupations. J. Manag. Psychol. 2005, 20, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Cognition and motivation in emotion. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 352–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandtstädter, J. Positive Entwicklung: Zur Psychologie Gelingender Lebensführung; Spektrum Akademischer Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brandtstädter, J.; Greve, W. The aging self: Stabilizing and protective processes. Dev. Rev. 1994, 14, 52–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, M.; Theron, L.; Liebenberg, L.; Tian, G.X.; Restrepo, A.; Sanders, J.; Munford, R.; Russell, S. Patterns of individual coping, engagement with social supports and use of formal services among a five-country sample of resilient youth. Glob. Ment. Health 2015, 2, e21. [Google Scholar]

- Barnová, S. Resiliencia a sociálna opora ako dva kľúčové faktory pri zvládaní záťaže. In Socialium Actualis II; Horváth, M., Barnová, S., Eds.; Tribun: Brno, Czech Republic, 2018; pp. 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Barnová, S.; Tamášová, V.; Krásna, S. The role of resilience in coping with negative parental behaviour. Acta Educ. Gen. 2019, 9, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lee, S.Y.; Hall, N.C. Coping profiles among teachers: Implications for emotions, job satisfaction, burnout, and quitting intentions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 68, 102030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, C. Development and testing of a theoretical-empirical model of educator stress, coping and burnout. In Educator Stress: An Occupational Health Perspective; McIntyre, T.M., McIntyre, S.E., Francis, D.J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 181–196. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, K.C.; Prewitt, S.L.; Eddy, C.L.; Savale, A.; Reinke, W.M. Profiles of middle school teacher stress and coping: Concurrent and prospective correlates. J. Sch. Psychol. 2020, 78, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.L. Toward a theoretical model to understand teacher emotions and teacher burnout in the context of student misbehavior: Appraisal, regulation and coping. Motiv. Emot. 2013, 37, 799–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marais-Opperman, V.; Rothmann, S.; Van Eeden, C. Stress, flourishing and intention to leave of teachers: Does coping type matter? SA J. Ind. Psychol. SA Tydskr. Vir Bedryfsielkunde 2021, 47, a1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarà, M. Teacher resilience and meaning transformation: How teachers reappraise situations of adversity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 63, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Day, C. Challenges to teacher resilience: Conditions count. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 39, 22–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q. The role of relational resilience in teachers’ career-long commitment and effectiveness. Teach. Teach. 2014, 20, 502–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kärner, T.; Bottling, M.; Friederichs, E.; Sembill, D. Between adaptation and resistance: A study on resilience competencies, stress, and well-being in German VET teachers. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 619912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, S.V.; Sosnowski, C. Emerging theory of teacher resilience: A situational analysis. Engl. Teach. Pract. Crit. 2019, 18, 492–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretsch, J.; Flunger, B.; Schmitt, M. Resilience predicts well-being in teachers, but not in non-teaching employees. Soc. Psychol. Educ. Int. J. 2012, 15, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltman, S.; Mansfield, C.; Price, A. Thriving not just surviving: A review of research on teacher resilience. Educ. Res. Rev. 2011, 6, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, S.; Oldfield, J. Quantifying teacher resilience: Context matters. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 82, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C. Resilient principals in challenging schools: The courage and costs of conviction. Teach. Teach. 2014, 20, 638–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.; Down, B.; Le Cornu, R.; Peters, J.; Sullivan, A.; Pearce, J.; Sullivan, A.; Pearce, J.; Hunter, J. Promoting early career teacher resilience: A framework for understanding and acting. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2014, 20, 530–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, M.; Lovett, S. Sustaining the commitment and realising the potential of highly promising teachers. Teach. Teach. 2014, 21, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, G.J. Resilience under fire: Perspectives on the work of experienced, inner city high school teachers in the United States. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2006, 22, 812–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, B.; Marshall, K. A framework for practice: Tapping innate resilience. Res. Pract. Newsl. 1997, 5, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Boon, H.J. Risk or resilience? What makes a difference? Aust. Educ. Res. 2008, 35, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, B.; Zucker, S.; Brehm, K. Resilient Classrooms: Creating Healthy Environments for Learning; Guiford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon Rouse, K.A.; Longo, M.; Trickett, M. Fostering Resilience in Children; Ohio State University Extension: Columbus, OH, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.W.; Webster, R.E. Risk factors among adult children of alcoholics. Int. J. Behav. Consult. Ther. 2007, 3, 494–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handson, T.L.; Kim, J.O. Measuring Resilience and Youth Development: The Psychometric Properties of the Healthy Kids Survey; U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory West: Washington, DC, USA, 2007.

- Kim, T.H.; Lee, S.M.; Yu, K.; Lee, S.; Puig, A. Hope and the meaning of life as influences on Korean adolescents’ resilience: Implications for counselors. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2005, 6, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S. Resilience in children at-risk. Res. Pract. Newsl. 1997, 5, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A.S.; Coatsworth, J.D. The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments. Am. Psychol. 1998, 53, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masten, A.S.; Gewirty, A.H. Resilience in Development: The Importance of Early Childhood; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A.; Obradović, J. Disaster preparation and recovery: Lessons from research on resilience in human development. Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, R.C. Tapping innate resilience in today‘s classrooms. Res. Pract. Newsl. 1997, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, T.; Blackburn, S. Transitions in the Lives of Children and Young People: Resilience Factors; Scottish Executive Education Department: Edinburgh, UK, 2002.

- Pomrenke, M. Using grounded theory to understand resiliency in pre-teen children of high-conflict families. Qual. Rep. 2007, 12, 356–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, K.A.G.; Bamaca-Gomez, M.Y.; Newman, P.; Newman, B. Educationally Resilient Adolescents’ Implicit Knowledge of the Resilience Phenomenon. Presented at the Annual Conference of the American Psychological Association, San Francisco, CA, USA, 24–28 August 2001. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED459393.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- Ungar, M. (Ed.) Handbook for Working with Children and Youth; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar, M. Strength-Based Counseling; Corvin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Haertel, G.; Walberg, H. Educational Resilience; National Research Center on Education in the Inner Cities: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1998.

- Bishay, A. Teacher motivation and job satisfaction: A study employing the experience sampling method. J. Undergrad. Sci. 1996, 3, 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, S.; Johnson, B. Resilient teachers: Resisting stress and burnout. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2004, 7, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, K.A.R.; Levesque-Bristol, C.; Templin, T.J.; Graber, K.C. The impact of resilience on role stressors and burnout in elementary and secondary teachers. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2016, 19, 511–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, D.D.; İskender, M. Exploring teachers’ resilience in relation to job satisfaction, burnout, organizational commitment and perception of organizational climate. Int. J. Psychol. Educ. Stud. 2018, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, Q.; Chu, L. Self-efficacy, reflection, and resilience as predictors of work engagement among English teachers. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1160681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, M.G.; Riding, R.J.; Falzon, J.M. Stress in teaching: A study of occupational stress and its determinants, job satisfaction and career commitment among primary schoolteachers. Educ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nobile, J.J.; McCormick, J. Job Satisfaction and Occupational Stress in Catholic Primary Schools. Presented at the Annual Conference of the Australian Association for Research in Education, Sydney, Australia, 27 November–1 December 2005. Available online: http://www.aare.edu.au/05pap/den05203.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- Chu, W.; Liu, H. A mixed-methods study on senior high school EFL teacher resilience in China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 865599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ergün, A.L.P.; Dewaele, J.-M. Do well-being and resilience predict the foreign language teaching enjoyment of teachers of Italian? System 2021, 99, 102506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.; Forrest, K.; Sanders-O’Connor, E.; Flynn, L.; Bower, J.M.; Fynes-Clinton, S.; York, A.; Ziaei, M. Teacher stress and burnout in Australia: Examining the role of intrapersonal and environmental factors. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2022, 25, 441–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmody, M.; Smyth, E. Job Satisfaction and Occupational Stress among Primary School Teachers and School Principals in Ireland. Available online: https://www.teachingcouncil.ie/en/publications/research/documents/job-satisfaction-and-occupational-stress-among-primary-school-teachers-and-school-principals-in-ireland.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).