Impact of Personality Traits on Small Charitable Donations: The Role of Altruism and Attitude towards an Advertisement

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Personality Traits and Donations

1.2. Charitable Attitudes and Advertisement

2. Materials and Methods

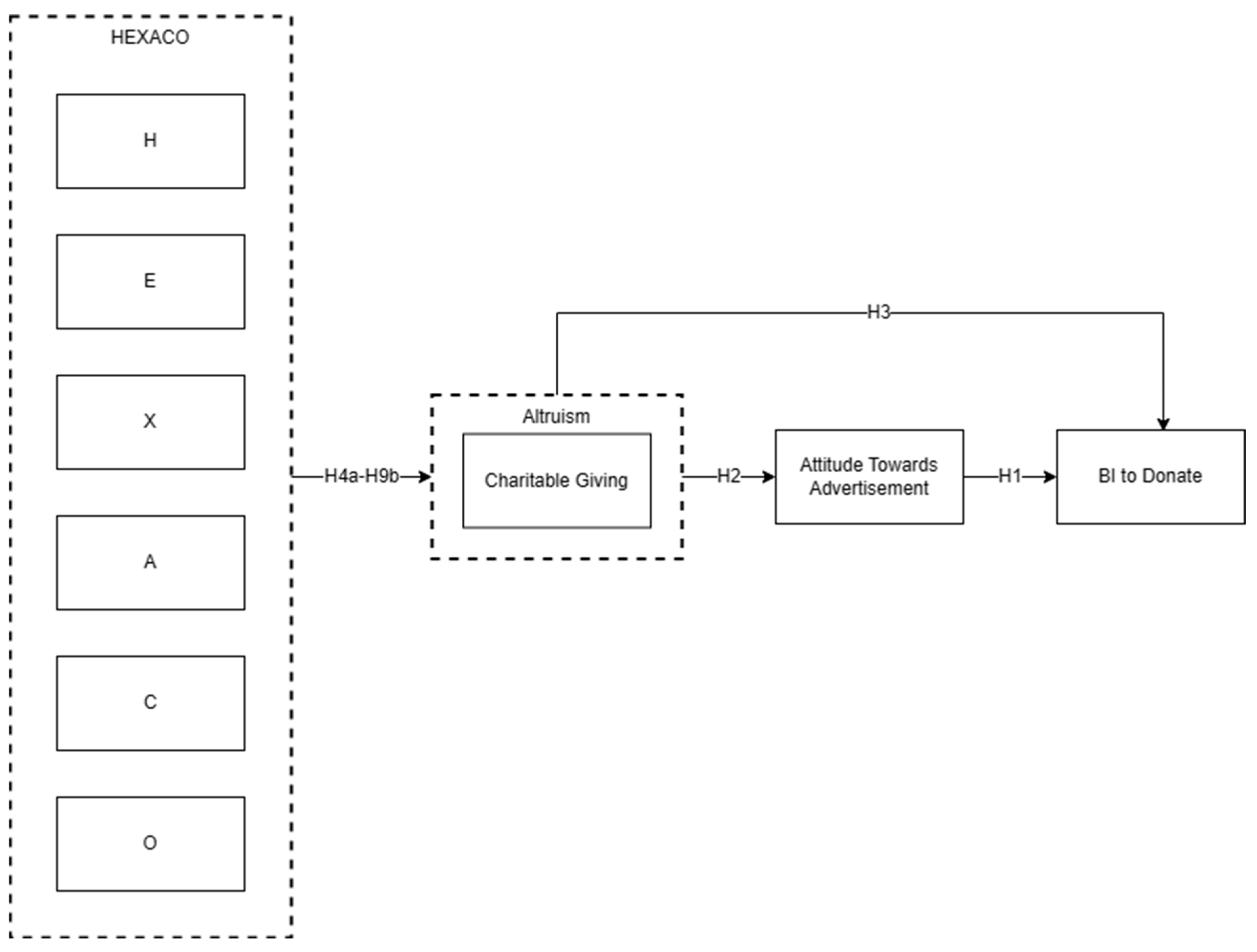

2.1. Research Model

2.2. Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Measurement Model

3.2. Structural Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Measurement Items Used for Data Collection

| Attitude towards advertisement (5-point semantic differential scale) | ||

| AAD1 | Like the ad (I dislike the ad—I like the ad) | Originally Holbrook and Batra [61] Adapted from Ranganathan and Henley [57] |

| AAD2 | Favorable (I react unfavorably to the ad—I react favorably to the ad) | |

| AAD3 | Positive (I feel negative toward the ad—I feel positive toward the ad) | |

| AAD4 | Advertisement is good (The ad is bad—The ad is good) | |

| Altruism (charitable giving) (5-point scale) | ||

| ACG1 | I have given money to a charity | Johnson et al. [62], and adapted from Kaya et al. [58], |

| ACG2 | I have given a money to a stranger who needed it (or asked me for it) | |

| ACG3 | I have donated goods or clothes to a charity | |

| ACG4 | I have pointed out a clerk’s error (in a bank, at the market) in undercharging me for an item | |

| ACG5 | I have paid a little more to buy an item from a merchant who I felt deserved my support | |

| Behavioral intention to donate (5-point scale) | ||

| BI1 | It is very likely that I will donate money | Originally from Coyle and Thorson [63] adapted from Ranganathan and Henley [57] |

| BI2 | I will donate money next time | |

| BI3 | I will definitely donate money | |

| BI4 | I will recommend others to donate money | |

References

- Kotler, P. Strategies for introducing marketing into nonprofit organizations. J. Mark. 1979, 43, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J. Philanthropy. In Handbook of the Economics of Giving, Altruism and Reciprocity; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 2, pp. 1201–1269. [Google Scholar]

- Payton, R.L.; Moody, M.P. Understanding Philanthropy: Its Meaning and Mission; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sulek, M. On the modern meaning of philanthropy. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2010, 39, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, C.E.; Lio, B.H. Innovation in non-profit and for-profit organizations: Visionary, strategic, and financial considerations. J. Chang. Manag. 2006, 6, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Lazarevski, K. Marketing in non-profit organizations: An international perspective. Int. Mark. Rev. 2009, 26, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blery, E.K.; Katseli, E.; Tsara, N. Marketing for a non-profit organization. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2010, 7, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prugsamatz, R. Factors that influence organization learning sustainability in non-profit organizations. Learn. Organ. 2010, 17, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymer, W. Nonprofit marketing research: Developing ideas for new studies. SN Bus. Econ. 2021, 1, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, C.D.; Shanahan, K.J.; Raymond, M.A. The moderating role of religiosity on nonprofit advertising. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vveinhardt, J.; Zygmantaite, R. Impact of social context on strategic philanthropy: Theoretical insight. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 214, 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Jia, L. The effects of the facial expression of beneficiaries in charity appeals and psychological involvement on donation intentions: Evidence from an online experiment. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2017, 27, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, M.; Dietrich, T.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Alhabash, S. Emotional appeals effectiveness in enhancing charity digital advertisements. J. Philanthr. Mark. 2022, 27, e1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G.W. Pattern and Growth in Personality; Holt, Reinhart & Winston: Austin, TX, USA, 1961; p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, G.W. Personality: A Psychological Interpretation; Holt, Reinhart & Winston: Austin, TX, USA, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, M.C.; Lee, K. Objections to the HEXACO model of personality structure—And why those objections fail. Eur. J. Personal. 2020, 34, 492–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielmann, I.; Spadaro, G.; Balliet, D. Personality and prosocial behavior: A theoretical framework and meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 146, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks-Leduc, L.; Feldman, G.; Bardi, A. Personality traits and personal values: A meta-analysis. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 19, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, N.; Wisse, B.; Heesink, J.A.; Van der Zee, K.I. Personality traits and career role enactment: Career role preferences as a mediator. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.L.; Abbott, R.D. Measurement of personality traits: Theory and technique. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1973, 24, 241–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, D.J. Implicit personality theory: A review. Psychol. Bull. 1973, 79, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkness, A.R. Theory and Measurement of Personality Traits; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P.T., Jr.; McCrae, R.R.; Dye, D.A. Facet scales for agreeableness and conscientiousness: A revision of the NEO Personality Inventory. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1991, 12, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; John, O.P. An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. J. Personal. 1992, 60, 175–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, P.T., Jr.; McCrae, R.R. The Revised Neo Personality Inventory (Neo-pi-r); Sage Publications, Inc.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Ashton, M.C. Psychometric properties of the HEXACO personality inventory. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2004, 39, 329–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashton, M.C.; Lee, K. Empirical, theoretical, and practical advantages of the HEXACO model of personality structure. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 11, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, M.C.; Lee, K. The HEXACO–60: A short measure of the major dimensions of personality. J. Personal. Assess. 2009, 91, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashton, M.C.; Lee, K. The HEXACO model of personality structure and the importance of the H factor. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2008, 2, 1952–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlo, G.; Okun, M.A.; Knight, G.P.; de Guzman, M.R.T. The interplay of traits and motives on volunteering: Agreeableness, extraversion and prosocial value motivation. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2005, 38, 1293–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Ashton, M.C. Psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism in the Five-Factor Model and the HEXACO model of personality structure. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2005, 38, 1571–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen-Campbell, L.A.; Adams, R.; Perry, D.G.; Workman, K.A.; Furdella, J.Q.; Egan, S.K. Agreeableness, extraversion, and peer relations in early adolescence: Winning friends and deflecting aggression. J. Res. Personal. 2002, 36, 224–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claxton-Oldfield, S.; Banzen, Y. Personality characteristics of hospice palliative care volunteers: The “big five” and empathy. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2010, 27, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoto, A.M.; Snyder, M.; Hackett, J.D. Personality and motivational antecedents of activism and civic engagement. J. Personal. 2010, 78, 1703–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.S.; Bouchacourt, L.; Brown-Devlin, N. Nonprofit organization advertising on social media: The role of personality, advertising appeals, and bandwagon effects. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.M.; Poulsen, B.E.; Hyde, M.K. Identity and personality influences on donating money, time, and blood. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2017, 46, 372–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei, N.; Błachnio, A.; Aminikhoo, M. The relations of gratitude to religiosity, well-being, and personality. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2018, 21, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarkoni, T.; Ashar, Y.K.; Wager, T.D. Interactions between donor Agreeableness and recipient characteristics in predicting charitable donation and positive social evaluation. PeerJ 2015, 3, e1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goi, C.L. A review of marketing mix: 4Ps or more. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2009, 1, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londhe, B.R. Marketing mix for next generation marketing. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 11, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargeant, A.; Hudson, J.; West, D.C. Conceptualizing brand values in the charity sector: The relationship between sector, cause and organization. Serv. Ind. J. 2008, 28, 615–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymer, W.; Gross, H. Charity advertising: A literature review and research agenda. J. Philanthr. Mark. 2021, e1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhati, A.; Dean, J. Charity advertising: Visual methods, images and elicitation. In Researching Voluntary Action; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2022; pp. 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Das, E.; Kerkhof, P.; Kuiper, J. Improving the effectiveness of fundraising messages: The impact of charity goal attainment, message framing, and evidence on persuasion. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2008, 36, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freriksen, D. Creating Trust through Charity Advertisement: Focusing on Charity Successes or Future Goals, by Using Statistical or Anecdotal Evidence? University of Twente: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, R.; Barkensjo, A. Causes and consequences of donor perceptions of the quality of the relationship marketing activities of charitable organisations. J. Target. Meas. Anal. Mark. 2005, 13, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anik, L.; Aknin, L.B.; Norton, M.I.; Dunn, E.W. Feeling good about giving: The benefits (and costs) of self-interested charitable behavior. In Harvard Business School Marketing Unit Working Paper; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albouy, J. Emotions and prosocial behaviours: A study of the effectiveness of shocking charity campaigns. Rech. Et Appl. En Mark. 2017, 32, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.-H.; Yucel-Aybat, O. Persuasive charity appeals for less and more controllable health causes: The roles of implicit mindsets and benefit frames. J. Advert. 2018, 47, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, H. Emotional death: The charity advert and photographs of childhood trauma. J. Cult. Res. 2004, 8, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbert, S.; Smith, A.; Davies, A.; Ireland, F. Guilt appeals: Persuasion knowledge and charitable giving. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. The impact of guilt and shame in charity advertising: The role of self-construal. J. Philanthr. Mark. 2022, 27, e1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargeant, A.; Ewing, M. Fundraising direct: A communications planning guide for charity marketing. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2001, 9, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R. Individual characteristics and the arousal of mixed emotions: Consequences for the effectiveness of charity fundraising advertisements. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2015, 20, 188–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.; Shiparo, S.; Ridinger, L.; Gomez, E. An Examination of Motivations, Attitudes and Charitable Intentions for Running in a Charity Event. J. Amat. Sport 2021, 7, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.R.; Brunel, F.F.; Supphellen, M.; Manchanda, R.V. Effects of culture, gender, and moral obligations on responses to charity advertising across masculine and feminine cultures. J. Consum. Psychol. 2006, 16, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, S.K.; Henley, W.H. Determinants of charitable donation intentions: A structural equation model. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2008, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, I.; Yeniaras, V.; Kaya, O. Dimensions of religiosity, altruism and life satisfaction. Rev. Soc. Econ. 2021, 79, 717–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlandsson, A.; Nilsson, A.; Västfjäll, D. Attitudes and donation behavior when reading positive and negative charity appeals. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2018, 30, 444–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay, J.C.; Hoppmann, C.A. Altruism and prosocial behavior. Encycl. Geropsychol. 2015, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Batra, R. Assessing the role of emotions as mediators of consumer responses to advertising. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 14, 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.C.; Danko, G.P.; Darvill, T.J.; Bochner, S.; Bowers, J.K.; Huang, Y.-H.; Park, J.Y.; Pecjak, V.; Rahim, A.R.; Pennington, D. Cross-cultural assessment of altruism and its correlates. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1989, 10, 855–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, J.R.; Thorson, E. The effects of progressive levels of interactivity and vividness in web marketing sites. J. Advert. 2001, 30, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, R.E. The 24-item brief HEXACO inventory (BHI). J. Res. Personal. 2013, 47, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, L.A. Snowball sampling. Ann. Math. Stat. 1961, 32, 148–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadish, W.R.; Cook, T.D.; Campbell, D.T. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference; Houghton, Mifflin and Company: Ventura, CA, USA, 2002; p. 504. [Google Scholar]

- Norheim-Hansen, A. Are ‘green brides’ more attractive? An empirical examination of how prospective partners’ environmental reputation affects the trust-based mechanism in alliance formation. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 132, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, D.A.; Verrochi, N.M. The face of need: Facial emotion expression on charity advertisements. J. Mark. Res. 2009, 46, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Steenburg, E. Nonprofit Advertising and Behavioral Intention: The Effects of Persuasive Messages on Donations and Volunteerism; University of North Texas: Denton, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Yoon, S. Political ideology of donors and attribution messages in charity advertising: An abstract. In Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science Annual Conference, Coronado Island, CA, USA, 27 May 2017; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Ryazanov, A.A.; Christenfeld, N.J. On the limited role of efficiency in charitable giving. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2018, 47, 939–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestler, S.; Lüdtke, O.; Robitzsch, A. Maximum likelihood estimation of a social relations structural equation model. Psychometrika 2020, 85, 870–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Essentials of Psychological Testing; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Ursachi, G.; Horodnic, I.A.; Zait, A. How reliable are measurement scales? External factors with indirect influence on reliability estimators. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 20, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3. Baskı). Guilford 2011, 14, 1497–1513. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, L.; Yang, M.; Marcoulides, K.M. Structural equation modeling with many variables: A systematic review of issues and developments. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Maydeu-Olivares, A. The effect of estimation methods on SEM fit indices. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2020, 80, 421–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Yang, Y. RMSEA, CFI, and TLI in structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: The story they tell depends on the estimation methods. Behav. Res. Methods 2019, 51, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peugh, J.; Feldon, D.F. “How well does your structural equation model fit your data?”: Is Marcoulides and Yuan’s equivalence test the answer? CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2020, 19, es5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimand-Sheiner, D.; Kol, O.; Levy, S. Help me if you can: The advantage of farmers’ altruistic message appeal in generating engagement with social media posts during COVID-19. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, T.H.; Yoon, S. Pride and Gratitude: Egoistic versus Altruistic Appeals in Social Media Advertising. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfattheicher, S.; Nielsen, Y.A.; Thielmann, I. Prosocial behavior and altruism: A review of concepts and definitions. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 44, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier-Watts, J. Faith, Hope and Charity–A Critical Review of Charity Law’s Socio-Legal Reconciliation of the Advancement of Religion as a Recognised Head of Charity; The University of Waikato: Hamilton, New Zealand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Hypotheses | |

|---|---|

| H1 | Attitude towards advertisement (AAD) has a direct positive effect on behavioral intention to donate (BI). |

| H2 | Attitude towards advertisement (AAD) has a direct positive effect on charitable giving (ACG). |

| H3 | Charitable giving (ACG) has a direct positive effect on behavioral intention to donate (BI). |

| H4a | Honesty-humility has a positive relationship with attitude towards advertisement (AAD). |

| H4b | Honesty-humility has a positive relationship with charitable giving (ACG). |

| H5a | Emotionality has a positive relationship with attitude towards advertisement (AAD). |

| H5b | Emotionality has a positive relationship with charitable giving (ACG). |

| H6a | Extraversion has a positive relationship with attitude towards advertisement (AAD). |

| H6b | Extraversion has a positive relationship with charitable giving (ACG). |

| H7a | Agreeableness has a positive relationship with attitude towards advertisement (AAD). |

| H7b | Agreeableness has a positive relationship with charitable giving (ACG). |

| H8a | Conscientiousness has a positive relationship with attitude towards advertisement (AAD). |

| H8b | Conscientiousness has a positive relationship with charitable giving (ACG). |

| H9a | Openness to experience has a positive relationship with attitude towards advertisement (AAD). |

| H9b | Openness to experience has a positive relationship with charitable giving (ACG). |

| Frequency | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 173 | 52.1% |

| Female | 159 | 47.9% | |

| Age | 18–25 | 110 | 33.1% |

| 26–30 | 120 | 36.1% | |

| 31–40 | 48 | 14.5% | |

| 41–50 | 26 | 7.8% | |

| 51–60 | 19 | 5.7% | |

| 60+ | 9 | 2.7% | |

| Education | High school graduate | 53 | 16.0% |

| Undergraduate student | 93 | 28.0% | |

| Graduate | 107 | 32.2% | |

| Postgraduate student | 43 | 13.0% | |

| Postgraduate | 29 | 8.7% | |

| PhD candidate | 1 | 0.3% | |

| Doctoral | 1 | 0.3% | |

| Other | 5 | 1.5% |

| Personality Trait | Hypotheses | R2 | F (Sig) | Beta | T (Sig) | SE | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Honesty-Humility | 3.9081 | 0.68309 | ||||||

| H4a: Honesty-Humility-AAD | 0.154 | 59,877 (<0.01) | 0.392 | 12,868 (<0.01) | 0.191 | |||

| H4b: Honesty-Humility-ACG | 0.131 | 49,961 (<0.01) | −0.363 | 44,782 (<0.01) | 0.102 | |||

| Emotionality | 2.6935 | 0.56524 | ||||||

| H5a: Emotionality-AAD | 0.082 | 29,496 (<0.01) | −0.286 | 21,719 (<0.01) | 0.164 | |||

| H5b: Emotionality-ACG | 0.1 | 36,807 (<0.01) | −0.317 | 25,509 (<0.01) | 0.086 | |||

| Extraversion | 3.5858 | 0.58957 | ||||||

| H6a: Extraversion-AAD | 0.137 | 52,146 (<0.01) | 0.370 | 14,449 (<0.01) | 0.166 | |||

| H6b: Extraversion-ACG | 0.151 | 58,808 (<0.01) | −0.389 | 48,221 (<0.01) | 0.087 | |||

| Agreeableness | 3.1318 | 0.57365 | ||||||

| H7a: Agreeableness-AAD | 0.038 | 13,033 (<0.01) | 0.195 | 14,779 (<0.01) | 0.171 | |||

| H7b: Agreeableness-ACG | 0.151 | 58,595 (0.01) | −0.388 | 43,999 (<0.01) | 0.085 | |||

| Conscientiousness | 3.5685 | 0.69987 | ||||||

| H8a: Conscientiousness-AAD | 0.101 | 36,965 (<0.01) | 0.317 | 11,726 (<0.01) | 0.202 | |||

| H8b: Conscientiousness-ACG | 0.215 | 90,380 (<0.01) | −0.464 | 44,687 (<0.01) | 0.1 | |||

| Openness to Experience | 3.4661 | 0.65655 | ||||||

| H9a: Openness to Experience-AAD | 0.041 | 13,982 (<0.01) | 0.202 | 14.07 (<0.01) | 0.195 | |||

| H9b: Openness to Experience-ACG | 0.210 | 87,703 (<0.01) | −0.458 | 45,701 (<0.01) | 0.094 |

| Constructs | Items | Factor Loadings | AVE | CR | Cronbach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAD | 0.44 | 0.89 | 0.891 | ||

| AAD 1 | 0.770 | ||||

| AAD 2 | 0.823 | ||||

| AAD3 | 0.842 | ||||

| AAD4 | 0.841 | ||||

| BI | 0.69 | 0.90 | 0.9 | ||

| BI 1 | 0.778 | ||||

| BI 2 | 0.906 | ||||

| BI 3 | 0.875 | ||||

| BI 4 | 0.772 | ||||

| ACG | 0.53 | 0.81 | 0.822 | ||

| ACG2 | 0.541 | ||||

| ACG3 | 0.849 | ||||

| ACG5 | 0.614 | ||||

| ACG1 | 0.876 |

| Hypotheses | Estimates | Result (p-Value) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: AAD | <--> | BI | −0.06 | Not Supported (p < 0.001) |

| H2: AAD | <--> | ACG | −0.12 | Not Supported (p < 0.001) |

| H3: BI | <--> | ACG | 0.87 | Supported (p < 0.001) |

| Goodness-of-Fit Indices | Value | Acceptable Values |

|---|---|---|

| TLI | 0.944 | >0.90 |

| RMSEA | 0.09 | <0.08 |

| GFI | 0.921 | >0.90 |

| CFI | 0.944 | >0.90 |

| NFI | 0.927 | >0.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balaskas, S.; Panagiotarou, A.; Rigou, M. Impact of Personality Traits on Small Charitable Donations: The Role of Altruism and Attitude towards an Advertisement. Societies 2023, 13, 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13060144

Balaskas S, Panagiotarou A, Rigou M. Impact of Personality Traits on Small Charitable Donations: The Role of Altruism and Attitude towards an Advertisement. Societies. 2023; 13(6):144. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13060144

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalaskas, Stefanos, Aliki Panagiotarou, and Maria Rigou. 2023. "Impact of Personality Traits on Small Charitable Donations: The Role of Altruism and Attitude towards an Advertisement" Societies 13, no. 6: 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13060144

APA StyleBalaskas, S., Panagiotarou, A., & Rigou, M. (2023). Impact of Personality Traits on Small Charitable Donations: The Role of Altruism and Attitude towards an Advertisement. Societies, 13(6), 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13060144