Abstract

This paper presents the theoretical and operational approach of the AMIF-funded project INTE-great “Stakeholder Partnership for the Integration of Migrants”, which has the aim of building a stronger integration strategy and ecosystem for migrants, in particular asylum seekers, refugees and migrants with subsidiary protection (women, men, families and LGBTIQ+) at the urban level through cross-sector stakeholder partnerships, developing an innovative integration strategy framework (ISF) according to which five pilot initiatives will be tested through experimentation in five partnering countries (IT, ES, EL, CY and IE). The paper is structured as follows: After retracing the main development of the integration concept in different social sciences, we propose the operational definition of integration adopted in the project. We then concentrate on the role of migrants’ participation in enhancing a more effective integration path, before presenting the way in which we interpret the meaning of social innovation in the five pilot initiatives of the INTE-great project. We conclude by highlighting that a multistakeholder partnership adopting a real participatory migrant approach in the codesign, implementation and evaluation of the pilot initiatives constitutes the added value of social innovation in the field of migrants’ integration services.

1. Introduction

Despite the widespread perception within European public opinion, migration does not represent a new phenomenon: people have been on the move since the beginning of humankind, with the aim of reacting to environmental stress, social upheaval and other challenges. The same is true today, even though migration has now become global in scale. Concurrently, migrant integration is not a new topic in the social sciences, as it can be traced back to the 1920s, when scholars analyzed similarities, differences and interactions among groups [1], enhancing the difficulties and complexities faced by migrants in their “adaptation” process, which has, for a long time, been mainly intended as one-way. Since then, many concepts—varying across time and space—have been used to refer to this process. Therefore, some reflections are needed before presenting the understanding of integration that we adopted in the INTE-great project: integration is a multifaceted term that is given a different meaning on a range of levels with immensely varied political and normative consequences. Therefore, the need to conceptualize it is not merely a question pertaining to the academic debate but a critical and conscious choice of field regarding the principles inspiring actions.

In fact, scholars have clearly demonstrated the strict connection existing between the field of integration research and the development of integration policy and discourse [2,3]. The definition of integration has an increasing influence on both political and social discourse, as it is used “indirectly to substantiate policy choices or to legitimize political actors” [4] (330). However, the influence of research risks being minimized through the growing power of the media, which are increasingly acting “as an intermediary between integration scholars and policy-making, thereby affecting the public discourse on integration” [4] (334). As a result, media, politicians and policy discourses are significant stakeholders regarding the movement of people in the European Union while framing public opinion and people’s attitudes towards migrants’ integration. Starting from 2015, the representations of migrants that have emerged in public debates and the media have become more negative and aggressive than in previous decades, especially in online social media [5].

It is true that EU Member States differ in the number and structure of migrants, laws and rules of admittance, migration and integration policies and the objectives constituting integration systems. However, what emerges in most of them is a strong correlation between the media coverage of migration and political agendas. Influencing the perception of migration by the public, media play a determining role in shaping policy measures, either hindering or supporting migrants’ integration into EU Member States [6], causing the mood towards migrants to swing between inclusionary and exclusionary demands. To counteract this trend, there is the need for the growing engagement of scholars in legitimizing migration and integration policies and discourses, contributing in this way to also influence the course of integration processes. This paper presents the theoretical and operational approach of the AMIF-funded project INTE-great “Stakeholder Partnership for the Integration of Migrants”, which has the aim of building a stronger integration strategy and ecosystem for migrants, in particular asylum seekers, refugees and migrants with subsidiary protection (women, men, families and LGBTIQ+)1 at the urban level through cross-sector stakeholders partnerships, developing an innovative integration strategy framework (ISF) according to which five pilot initiatives will be tested through experimentation in five partnering countries (IT, ES, EL, CY and IE). The paper is structured as follows: After retracing the main developments of the integration concept in different social sciences, we propose the operational definition of integration adopted in the project. We then concentrate on the role of migrants’ participation in enhancing a more effective integration path before presenting the way in which we interpret the meaning of social innovation in the five pilot initiatives of the INTE-great project. The paper ends with some concluding remarks.

2. The Ambiguous Nature of Integration

Even today, integration remains an umbrella term under which sits a whole range of processes and domains [7] that are understood differently in policy, practice and academia according to the perspective, interests, assumptions and values of the different actors tackling the topic [8]. Social psychologists, particularly Berry [9], refer to the idea of integration as a process, retaining that over time both migrant groups and host societies change, and new identities emerge as a consequence of an acculturation process. This interpretation of integration, as produced through the dialectical relationship among either groups or individuals, represents a shift from the “classical model” of assimilation proposed by the Chicago School [1] which, since the 1920s, has been for nearly half a century the dominant vision of immigrant adaptation. This approach considers integration to be a one-way process, with the onus on migrants to integrate into societies of settlement, denying their original cultural links. This normativity implies an asymmetric understanding of social processes, characterized by rigid structures (state’s integration requirements) and minimal room left for the agency of migrants themselves [10]. On the contrary, the core of Berry’s conceptualization of integration is the two-way nature of the process that implies both host and migrant adaptation so that new values and identities emerge. However, it cannot be denied that public discourse—assessing integration—often judges migrants as “successfully” or “unsuccessfully” integrated, assuming in this way that there is a set of homogenous norms to adopt, neglecting how migrants experience integration as individuals [8].

Differently than social psychological research, sociological and social policy analyses are much more focused on the different dimensions of integration, highlighting the need to interpret it as a multidimensional process in which individuals, migrant and refugee community organizations (MRCOs), institutions and society all take part [11,12]. Despite this, policy concentrates mainly on the concrete and quantifiable aspects of the process, adopting a top-down approach focused on the structural and organizational elements of the system [13]. Outlining the functional dimensions of integration, it [14] identifies progress in education and training, the labor market, health and housing as necessary fuel for starting the integration process, forgetting the importance that the individual and relational aspects play in it. As the academic literature underlines, integration implies the development of a sense of belonging in the host community and a critical negotiation of identity by both refugees and hosts that is by necessity based on the development of social relationships and networks [15]. Moreover, individual migrants differ in what concerns the means and confidence to exercise their rights to access resources such as education, work and housing depending, for example, on their knowledge of the host language, educational employment background and/or their willingness to utilize them [16]. Therefore, research on integration is needed that investigates the subjective nature of the integration process, allowing migrants to express their views and valorize their experiences [11,13], focusing holistically on the many dimensions of integration and the way that they are perceived and experienced by individuals and their interconnected nature to be considered in the planning, implementation and evaluation of the actions set in motion to reach the goal. The INTE-great project tries to pave this ambitious way.

3. The Operational Definition of Integration in the INTE-great Project

The AMIF-funded project INTE-great, Stakeholder Partnership for the Integration of Migrants, involving partners from Italy, Spain, Greece, Cyprus and Ireland, has the aim of building at the urban level a stronger integration strategy and ecosystem for migrants who arrived in these countries from 2015 onwards, in particular for asylum seekers, refugees and migrants with subsidiary protection (women, men, families and LGBTQIA+). This should be achieved setting in motion cross-sectoral stakeholders’ partnerships and developing an innovative integration strategy framework (ISF) from which to derive practical guidelines to be used as reflective tools by stakeholders and social workers operating in integration projects, services and spot actions. ISF and guidelines should be tested and experimented through five pilot initiatives by the partnering organizations located in the cities of Varese (IT), Barcelona (ES), Athens (EL), Nicosia (CY) and Limerick (IE). This operational goal should be achieved with the involvement of municipalities, nonprofit organizations, academia, civil society and migrants in the codesign and implementation of the pilot activities that are grounded on the direct engagement of migrants and local citizens in order to increase mutual trust and sense of belonging making all interacting people sure that all contributions matter.

Activities include the organization of intercultural events to reduce prejudice and discrimination, information sessions for migrants on local policies related to healthcare and employment, training programs to build and strengthen their soft and professional skills and cultural training for local citizens to facilitate interactions. A set of digital tools, such as social media, web-based platform and an online integration hub (IHub), are used to reach the target groups of each activity and disseminate the results. The mobilization of the target groups will be activated through the pilots and by engaging local stakeholders in awareness-raising events, workshops and digital live forums. The long-term vision of INTE-great is to activate the durable involvement of stakeholders and set in motion a new relational approach and commitment between migrants and local communities.

To this aim, we needed to adopt an operational concept of integration that guides the planning, implementation and evaluation criteria of the five pilot initiatives we aim to achieve. For this purpose, we chose the integration definition proposed by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), which, since 1951, has grown as the leading intergovernmental organization in the field of migration, working closely with governmental, intergovernmental and nongovernmental partners to promote its humane management. Recognizing the right of freedom of movement and the link between migration and economic, social and cultural development, IOM’s principles are in line with the innovation criteria of our proposal and the suggestions emerging from the holistic research approach to integration. According to IOM:

“Integration can generally be defined as the process of mutual adaptation between the host society and the migrants themselves, both as individuals and as groups. Migrant integration policy frameworks should take into consideration the rights and obligations of migrants and host societies, including access to the labor market, health and social services, and education for children and adults. Integration implies a sense of obligation and respect for a core set of values that bind migrants and their host communities in a common purpose.”[17]

In the EU context, the integration process is linked to the recognition of rights, duties and citizenship. During this process, individuals move through a multisectoral inclusion route involving employment, housing, education and health that are referred to as “public outcomes”, because these are both the outward “markers” of integration and, at the same time, “means” towards a deeper inclusion in the community in which they live. However, internal dimensions as the subjective integration factors [18] are also important. Indeed, all along this path, individuals’ subjective well-being and feelings of safety, stability, belongingness and detachment are subject to and depend on the quality of the interaction they have with other societal actors that can be enhanced or impeded through facilitators such as language and cultural knowledge. All in all, integration results in a tridirectional process, in which migrants themselves, the pre-existing refugees and migrant communities, and the host community participates.

Among these three levels of actors, Ager and Strang [15] identified three different forms of social connections or relationships resulting in social bonds within a migrants’ community sharing either an ethnic/national or religious identity. Such connections also produce social bridges between them and other communities, including relationships with members of other migrant communities and/or local community members that could facilitate the development of social links with institutions, including local and central government services, improving migrants’ access to social services and their participation in broader civic engagement activities (see also [19]). Finally, this process also incorporates several external dimensions, including the general conditions in which the reception takes place, as well as legal, socioeconomic and sociocultural factors [20]. This means that beyond the migration and integration policies framing the integration process and counteracting the media discourse on migrants (see Section 1), the success of integration is highly dependent on the local community’s attitude towards migrants in term of personal proximity and rates of interactions as a supportive environment is of high importance for the success and well-being of migrants.

Adopting this operational approach, in INTE-great we assume that integration can be no more intended as the final result of the commitments, efforts and achievements of migrants, but it strongly depends on the structure and openness of the receiving society [15,21,22,23]. Therefore, the planning and implementation of the five pilot initiatives are based on the active participation and interaction of all the parts (partners) involved in them. As a final step, their impact will be evaluated and critically analyzed to assess whether they have been successful in fostering mixing, interaction and pluralism, considered as the main result of the process of ongoing negotiation [24] between societies and migrants [15,23]. This focus on social mixing and positive contact between migrants and local communities is theoretically grounded on Allport’s contact hypothesis [25] IGCT, claiming that “when people from different backgrounds meet and mix under the right circumstances, trust grows and prejudice declines across participating social groups” [26]. Recent academic literature on intergroup contact shows solid empirical evidence that under certain conditions (participants’ equal status and common goals, intergroup cooperation and support of authorities, law or customs) positive contact among individuals of different social groups are more likely to improve relations among those groups [27] (5). Pettigrew and Tropp (2006) reviewed 203 studies from 25 countries (involving 90,000 participants) and found that 94% of them supported the contact hypothesis, demonstrating that 94% of the time, prejudice diminished as intergroup contact increased [27]. Therefore, trying to encourage friendly, helpful and egalitarian attitudes and condemning ingroup–outgroup comparisons, in INTE-great we adopt a participatory approach to encourage migrants and local communities meet and act together towards shared goals. At this point, a new conceptual challenge arose: what does participation mean?

4. The Many Meanings of Participation: Challenges and Opportunities

Generally speaking, participation means both to take part in and to take part of something, being involved in as well as sharing something. This is reflected by discourses of participation that relate to a variety of phenomena. While political participation refers to the relationship between individual and society in terms of citizen and state, social or civic participation refer to the relationship between the individual self and a group or community and primarily refer to collective action: membership, especially active membership, in associations and organizations. With regard to participation of young people, Walther [28] distinguished participation as a principle of societal practice from participation as an objective, which points to an understanding according to which young people first have to be prepared for participation [29,30].

Why did we focus on a definition of participation referring to young people in a project dealing with planning and implementing services promoting migrants’ integration? The answer is simple. Both young people and migrants share the condition of being considered as not full citizens but as citizens “in the making”. This becomes evident when analyzing projects targeted either to young people or migrants in which participation is intended more as a learning tool leading to integration than as common principle. As young people are not autonomous in the management of their life but preparing to become independent—by going to school and learning from adults—migrants too are expected to “prepare” for their life in Europe. Their previous process of maturation, the complexity of the choices they had to make as a man or a woman, or as a teenager grown up very fast because of the very hard trials inherent in every migration project, are often disregarded by the existing approaches of policies and services devoted to migrants that adopt a paternalistic approach limiting individual or group autonomy “for their own good”, often by eliminating any agency from those people it probably intends to help.

To the aim of understanding what kind of participation is proposed to migrants and how it should be interpreted to make them actually involved in topics that are vital for them, in the INTE-great project we adapted the Ladder of Participation of Children and Young people, first introduced by Sherry Arnstein [31] and further developed by Roger Hart [32], to assess the degree of migrants’ participation. Originally, this ladder clusters degrees of participation in eight ascending levels of decision making, agency, control and power that adults decide to share with children and youth. It represents a continuum of power that ascends from nonparticipation (no agency) to degrees of participation (increasing levels of agency). In the same way, we can detect and classify models of participation according to whether migrants are only consulted or involved in decision making and according to who initiates participatory processes, stakeholders only, stakeholder with migrants or migrants themselves. As it offers a compass for the development of a critical perspective of their own work, we suggest to organizations, stakeholders and practitioners involved in the INTE-great project that they should adopt this ladder for the analysis of the integration services they offer, and are explicitly aimed at migrants’ participation. Through this tool, they can reflect systemically on their ways of working, and in so doing, come up with something innovative and more effective for their particular context.

The eight rungs of Hart’s Ladder of Children’s Participation could be interpreted as follows when applied to migrants:

- 1.

- Manipulation takes place when migrants realize neither the reasons of a participatory process nor the role they play in it.

- 2.

- Decoration occurs when migrants are put on public display in the case of events, performances or other activities connected to migration’s issue, but they do not understand how and why they are involved.

- 3.

- Tokenism takes place when migrants are supposed to express their opinion, but they have either no or only a little possibility of choosing the topic or the way in which it is communicated.

- 4.

- Assigned but Informed happens when migrants are conscious of the goal of a certain activity, the reasons of their involvement and they intentionally participate in it.

- 5.

- Consulted and Informed occurs when migrants play the role of consultants for stakeholders and services providers, who plan and implement the activities, but they are aware of the process and feel that their opinions matter.

- 6.

- Stakeholder-Initiated but Shared Decisions occurs when stakeholders set in motion participatory projects, but they share decision making or management with migrants.

- 7.

- Migrant-Initiated Shared Decisions with Stakeholder takes place the other way round, when migrants share decision-making power and management with the stakeholder.

- 8.

- Migrant-Initiated and Directed occurs when migrants are in power of projects that are significant for them and work on them together in small or large groups. Stakeholders act as supporters of the working groups, but they do not play any directive role.

In the INTE-great Project with the aim of mobilizing migrants directly, we invited organizations, stakeholders and practitioners to plan their services and activities according to the last four rungs of the ladder. We also stressed the fact that—like any model—the ladder reflects some degree of cultural bias, and they should apply it with special caution to different cultures. As the ladder is the mirror of a “Western orientation” emphasizing individualism and the value of progressive independence and autonomy as main markers of integration, they should use it critically in the case of cultures that emphasize the value of collectivism and the maintenance of familial or communal interdependence in people’ life.

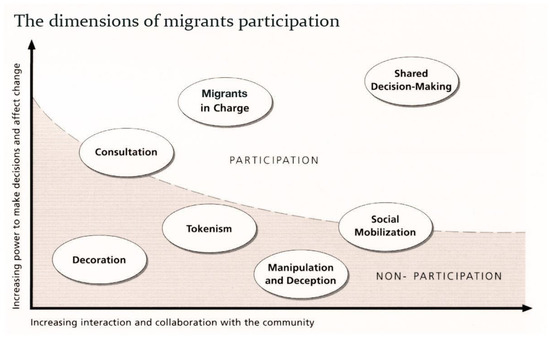

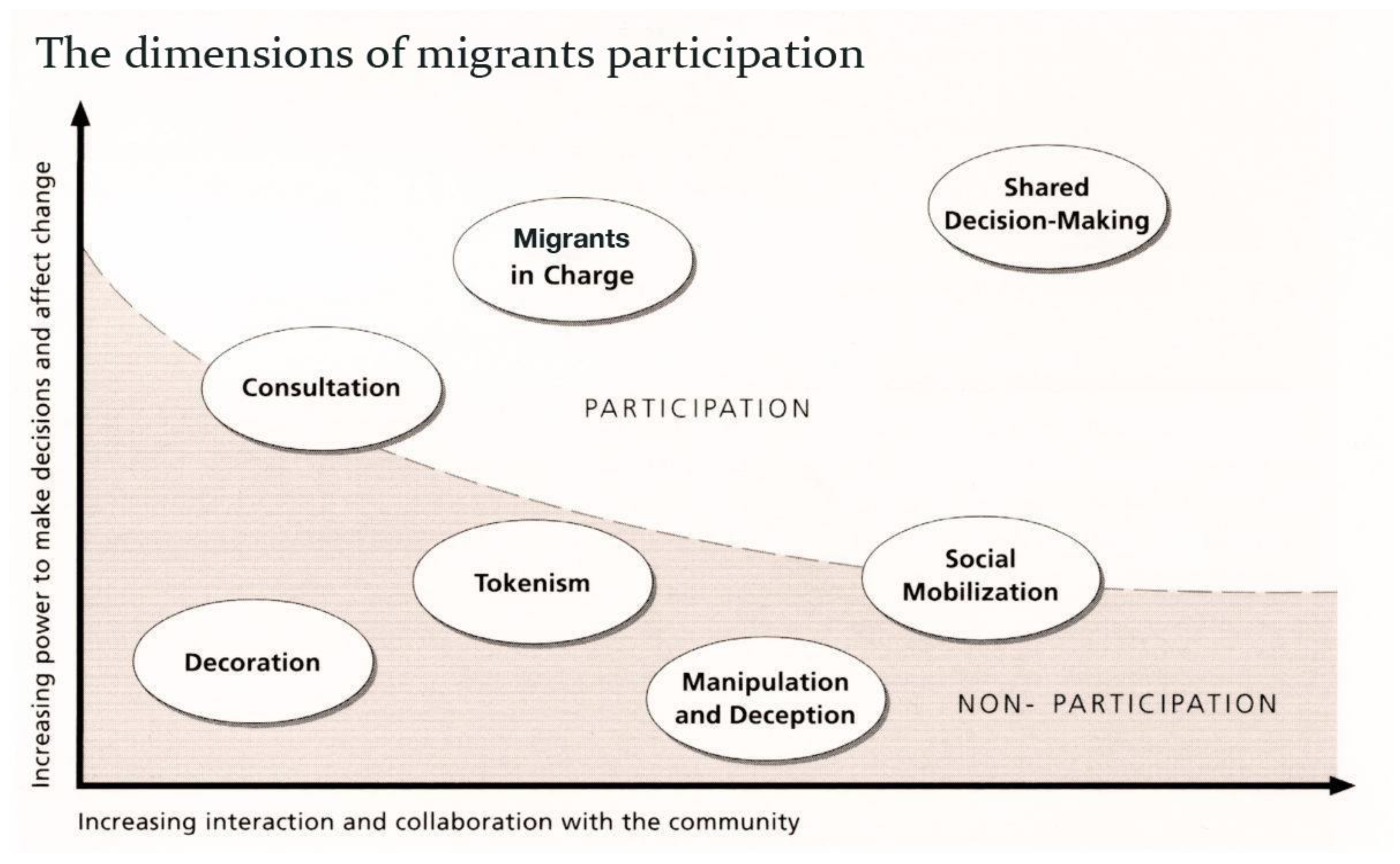

To move a step further, in an attempt to stress the importance of daily life interaction of migrants and local community and the crucial role of joint activities in the integration process, we have transposed the ladder on an X–Y axis illustrating the scope of migrants’ participation. The horizontal dimension shows growing levels of interaction and collaboration between migrants and community, while the vertical one illustrates migrants’ increasing power of decision making and self-determination.

Figure 1.

The scope of migrants’ participation (readaptation of the original image of David Driskell in Creating Better Cities with Children and Youth: A Manual for Participation [33]).

Figure 1.

The scope of migrants’ participation (readaptation of the original image of David Driskell in Creating Better Cities with Children and Youth: A Manual for Participation [33]).

Figure 1 can be easily used as an analytical tool, as it makes immediately visible the point on the Cartesian plane in which an action is placed, in both term of nonparticipation/participation (collaboration) and migrants’ agency (decision making and self-determination). Adopting it, organizations, stakeholders and practitioners can easily assess whether the pilots follow a participative approach and offer those socially innovative integration’s services which are the main object of the INTE-great project.

5. Social Innovation in the INTE-great Project

Social innovation is expected to offer solutions (products, services and models) to emerging contemporary societal problems, which neither classic tools of government policy nor market solutions are able to cope with [34] (3) and explicitly aim at the creation of social value meeting social needs and creating new social relationships and collaborations [35]. However, this concept—like those of integration and participation—is controversial, as it looks very differently in different sectors and locations [36]. Keeping in mind that it is cross-sectoral and multidisciplinary, in the INTE-great project we concentrated on the practice-led definition of social innovation, stressing the aims of meeting social goals and needs and focusing on the development of social innovation models and programs which can be replicated [37] (9).

Emphasizing the goal-oriented aspect of social innovations, Mumford [38] (253) defines it as “the generation and implementation of new ideas of how people should organize interpersonal activities, or social interactions, to meet one or more common goals.” According to him [38], social innovation can be represented as a continuum. On one end of it, there are new ideas about social organization or social relationships involving the creation of new institutions, new ideas of government or new social movements; on the other end, showing a less systemic character, social innovations may set in motion new processes and procedures for structuring new social practices in a group. In both cases, “it is intentionally planned, implemented and diffused through organizations whose primary purposes are social” [37] (8).

Keeping in mind that novelty and improvement are the two backbones of innovation [39], we were also aware that novelty does not necessarily mean originality. Innovation can be also realized when an already existing procedure or service is transferred in a new contest or used by a new social group, empowering beneficiaries by creating new roles, relationships, assets and capabilities [36] (21). Beneficiaries’ activation and self-esteem are considered key in fostering their social inclusion.

In the INTE-great project, the focus of social innovation is on the local development of communities and neighborhoods and the inclusion of migrants into different spheres of society. We consider beneficiaries’ activation and self-esteem as key to fostering their social inclusion. Reaching this is not an easy task, as innovation often implies people’s resistance, defending their interests, mental models and relationships.

According to Mulgan [37], social innovation implies the following stages:

- 1.

- The generation of ideas by intercepting needs and identifying potential solutions. In the INTE-great project, needs have been identified through semi-structured interviews with migrants, stakeholders and practitioners; focus groups and brainstorming were conducted to generate new ideas about viable improvements to the existing services.

- 2.

- The development of prototypes and the piloting of ideas follows the previous step to avoid the risk that without proper piloting the innovation does not work.

- 3.

- Scaling up and diffusion through organic growth, replication or adaption.

- 4.

- Learning and evolving through ongoing evaluation, as innovation can produce unintended consequences and, thus, needs suitable adaptations.

The INTE-great project, because of time and resource constraints, concentrates on the first two steps, but it adopts an ongoing evaluation of the pilots in an attempt to monitor their strengths and weaknesses, thinking of the possible future scaling up and diffusion of the same approach.

Social innovation is very strongly a matter of process innovation, i.e., changes in the dynamics of social relations, including power relations and social inclusion. Therefore, it explicitly refers to the ethical position of social justice that is inherent in the INTE-great project in which, in line with the aim of creating social value, we have concentrated on the content dimension in terms of the satisfaction of human needs in the fields of health; training and labor market; social cohesion; the process dimension, involving the process of changing social relations; and the empowerment dimension, increasing sociopolitical capability and access to resources [40].

6. Discussion

Considering participation and social innovation as a compass towards migrants’ integration, the first challenges of the AMIF-funded INTE-great project was to develop a theoretical framework in which the three concepts could be unambiguously reconnected to avoid misunderstandings between the different backgrounds, languages and implicit assumptions of the partners involved in the project. Integration, intended both as a process of mutual adaptation between the host society and the migrants themselves and an outcome that evolves over time, needs a holistic approach, catering both to the functional and social aspects of integration via a nexus of human and material resources. The ultimate goal is to prevent migrants—despite having access to one sector of society—from remain excluded from broader patterns of integration. From this assumption, we derived that a real participatory approach (see Section 4), both as individuals and as groups in the codesign, implementation and evaluation of the pilot initiatives we aimed to create, was the added value of social innovation in the field of migrants’ integration.

According to the dimensions of integration newly indicated in the European Commission’s Action Plan on Integration and Inclusion 2021–2027 [41] focusing on actions in sectoral areas such as employment, healthcare, capacity building and training, and stressing key principles and values regarding integration and inclusion, we planned to pilot fair and innovative services for migrants that lead to improved capabilities and relationships in the community, while meeting the social need of integration, in the attempt to “enhance society’s capacity to act” [36] (18). In this pluralistic vision, municipalities, nonprofit organizations, academia, civil society and migrants have been involved in piloting activities promoting mixing and interacting. Activities include the organization of intercultural events with the double aim of increasing migrants’ sense of belonging in the host communities, on the one hand, and of reducing prejudice and discrimination, on the other. In the same vein, information sessions for migrants on local policies related to healthcare and employment, training programs to build and strengthen their skills, and intercultural trainings for local citizens to facilitate encounters and interaction have been organized. Mobilization of target groups has been activated by partners through the pilots and by engaging local stakeholders in awareness raising events, workshops and digital live forums.

Ultimately, INTE-great aims to enable those long-term and cross-sectoral involvement of stakeholders and behavioral change by the public towards migrants promoted in 2021 by the Steering Committee on Anti-Discrimination, Diversity and Inclusion of the Council of Europe inviting EU Member States to promote novel integration strategies, valuing diversity as a resource, promoting diversity in institutions, residential and public spaces, and reducing segregation in social, cultural, economic and political life [42]. As soon as the pilots are evaluated and critically analyzed, a new contribution will be proposed to assess whether they have been successful in their aim of strengthening migrants’ integration and social cohesion adopting the theoretical approach presented in this concept paper.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Commission AMIF-2020: grant number: 101038260. The APC was funded by the same program.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | For the sake of brevity, in this paper the term “migrants” comprises all the categories included in the target group unless otherwise specified. |

References

- Park, R.E.; Burgess, E.W.; McKenzie, R.D. The City; Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Bommes, M.; Thraenhardt, D. National Paradigms of Migration Research; V&R Unipress: Goettingen, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dahinden, J. A plea for the ‘de-migranticization’ of research on migration and integration. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2016, 39, 2207–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, P.; Entzinger, H.; Penninx, R. Policy dialogues on migrant integration in Europe: A conceptual framework and key questions. In Integrating immigrants in Europe; Scholten, P., Entzinger, H., Penninx, R., Verbeek, S., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2015; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Titley, G. Racism and Media; Sage: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dennison, J.; Dražanova, L. Public Attitudes on Migration. Rethinking How People Perceive Migration; OPAM: Florence, Italy, 2018; Available online: https://www.icmpd.org/file/download/48432/file/Public0attitudes0on0migration_0rethinking0how0people0perceive0migration0EN.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Favell, A. Philosophies of Integration: Immigration and the Ideal of Citizenship in France and Britain; Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Castles, S.; Korac, M.; Vasta, M.; Vertovec, S. Integration: Mapping the Field; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W. Acculturation and adaptation in a new society. Int. Migr. 1992, 30, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, A.; Ager, A. Refugee integration: Emerging trends and remaining agendas. J. Refug. Stud. 2010, 23, 589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schibel, Y.; Fazel, M.; Robb, R.; Garner, P. Refugee Integration: Can Research Synthesis Inform Policy? Feasibility Study Report; Home Office: London, UK, 2002; Available online: https://silo.tips/download/refugee-integration-can-research-synthesis-inform-policy-feasibility-study-report (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Ager, A.; Strang, A. Indicators of Integration: Final Report, Home Office, Development and Practice Report 28; Home Office: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Korac, M. Integration and how we facilitate it: A comparative study of the settlement experiences of refugees in Italy and the Netherlands. Sociology 2003, 37, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyvie, A.; Ager, A.; Curley, G.; Korac, M. Integration: Mapping the Field: Volume II: Distilling Policy Lessons from the “Mapping the Field” Exercise; Home Office: London, UK, 2003. Available online: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20110218135832/rds.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs2/rdsolr2903.pdfHome (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Strang, A.; Ager, A. Understanding Integration: A Conceptual Framework. J. Refug. Stud. 2008, 21, 166–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gans, H. Ethnic invention and acculturation: A bumpy line approach. J. Am. Ethn. Hist. 1992, 12, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- IOM. Iom and Migrant Integration. Available online: https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/migrated_files/What-We-Do/docs/IOM-DMM-Factsheet-LHD-Migrant-Integration.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Hynie, M. Refugee integration: Research and policy. Peace Confl. J. Peace Psychol. 2018, 24, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolcock, M. Social capital and economic development: Toward a theoretical synthesis and policy framework. Theory Soc. 1998, 27, 151–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osanami Törngren, S.; Emilsson, H.; Khoury, N.; Maviga, T.; Irastorza, N.; Hutcheson, D.S.; Bevelander, P. Measuring Refugee Integration Policies in Sweden: Results from the National Integration Evaluation Mechanism 2021. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1654745/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Phillimore, J. Implementing integration in the UK: Lessons for integration theory, policy and practice. Policy Politics 2012, 40, 525–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, M.C.; Pineau, M.G. The Integration of Immigrants into American Society; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Korteweg, A.C. The failures of ‘immigrant integration’: The gendered racialized production of non-belonging. Migr. Stud. 2017, 5, 428–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrkamp, P. “We Turks are no Germans”: Assimilation discourses and the dialectical construction of identities in Germany. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2006, 38, 1673–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G.W.; Clark, K.; Pettigrew, T. The Nature of Prejudice; Perseus Books: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). The Power of “Contact”. Designing, Facilitating and Evaluating Social Mixing Activities to Strengthen Migrant Integration and Social Cohesion Between Migrants and Local Communities. A Review of Lessons Learned; IOM: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.iom.int/resources/power-contact-social-mixing-activities-strengthen-migrant-integration-and-social-cohesion-between-migrants-and-local-communities (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Pettigrew, T.F.; Tropp, L.R. A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 90, 751–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walther, A. Regimes of youth transitions: Choice, flexibility and security in young people’s experiences across different European contexts. Young 2006, 14, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. White Paper a New Impetus for European Youth. Brussels, 21.11.2001 COM(2001) 681 Final. 2001. Available online: https://pjp-eu.coe.int/documents/42128013/47261806/EC_whitepaper_en.pdf/21c7220a-1f4b-4ca0-a7ca-8d633a62c6b6?t=1382945911000 (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- European Commission. An EU Strategy for Youth-Investing and Empowering. A Renewed Open Method of Coordination to Address Youth Challenges and Opportunities. 2009. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2009:0200:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R.A. Children’s Participation: From Tokenism to Citizenship; United Nations Children’s Fund International Child Development Centre: Florence, Italy, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Driskell, D. Creating Better Cities with Children and Youth: A Manual for Participation; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, R.; Mulgan, G.; Caulier-Grice, J. How to Innovate: The Tools for Social Innovation. Work in Progress–Circulated for Comment. Available online: https://youngfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/How-to-innovate-the-tools-for-social-innovation.pdf. (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Murray, R.; Caulier-Grice, J.; Mulgan, G. The Open book of SOCIAL Innovation. Nesta. 2010. Available online: https://youngfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/The-Open-Book-of-Social-Innovationg.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Caulier-Grice, J.; Davies, A.; Patrick, R.; Norman, W. Social Innovation Overview: A Deliverable of the Project: “The Theoretical, Empirical and Policy Foundations for Building Social Innovation in Europe” (TEPSIE), European Commission–7th Framework Program; European Commission, DG Research: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mulgan, G. Social Innovation: What It Is, Why It Matters and How It Can Be Accelerated; Working Paper; Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurship: Oxford, UK, 2007; Available online: https://youngfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Social-Innovation-what-it-is-why-it-matters-how-it-can-be-accelerated-March-2007.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Mumford, M. Social Innovation: Ten Cases from Benjamin Franklin. Creat. Res. J. 2002, 14, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phills, J.; Deiglmeier, K.; Miller, D. Rediscovering Social Innovation. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2008, 6, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Moulaert, F.; Martinelli, F.; Gonzalez, S.; Swyngedouw, E. Introduction: Social Innovation and Governance in European Cities. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2007, 14, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. European Action Plan on Integration and Inclusion 2021–2027. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/migrant-integration/news/ec-reveals-its-new-eu-action-plan-integration-and-inclusion-2021-2027_en (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Steering Committee on Anti-discrimination, Diversity and Inclusion (CDADI). Model Framework for an Intercultural Integration Strategy at the National Level. Intercultural Integration Strategies: Managing Diversity as an Opportunity; Council of Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://rm.coe.int/prems-093421-gbr-2555-intercultural-integration-strategies-cdadi-web-a/1680a476bd (accessed on 12 June 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).