Abstract

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, platform capitalism has expanded greatly in the delivery sector. The consolidation of an oligopoly controlled by a few corporate platforms has led to precarious working conditions for “gig economy” workers. Increasing protests and strikes have led to the reform of labour directives and to the emergence of alternative ways of organising work through platform cooperatives. This article examines how these emergent platform cooperatives are mobilised and their challenges and implications. Barcelona, the cradle of many platform economy and delivery sector start-ups, is a critical case for examining the recent birth of alternative delivery cooperatives. This article is informed by the cases of three cooperatives, organised by those working as riders, providing delivery services in the city of Barcelona: Mensakas, Les Mercedes, and 2GoDelivery. The paper shows how the embeddedness of these nascent platform cooperatives in favourable governance arrangements, a supportive social and solidarity movement, the knowledge and experience of workers, and the territory where the cooperatives are embedded are essential for their creation. This multi-layered embeddedness is necessary, but not sufficient, to explain how platform cooperatives thrive. The study concludes that the agency of platform workers, who triggered this transformation, was essential for the emergence of alternative ways of organising work in the platform economy.

1. Introduction

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, platform capitalism has expanded greatly in the delivery sector. Riders have become new “waiters on wheels”. The consolidation of an oligopoly controlled by a few online corporate platforms has led to the emergence of the “gig economy” [1], in which gig workers constitute a flexible working force. The externalisation of risks through self-employment, economic dependency on the digital platforms, and the surveillance of workers who are powerless to counteract users’ evaluations have made such work even more precarious in terms of income, autonomy, and scheduling [2].

However, workers in the platform economy have not remained passive. Increasing protests and strikes have led to the transformation of national and European labour directives and to the emergence of alternative ways of organising work through platform cooperatives [2,3]. Platform co-ops, as they are also called, combine online digital technologies with ownership and democratic governance in the form of producer or worker cooperatives [4].

While the dire negative impacts of the platform economy have already been widely documented in the scientific literature, the rationales and implications of the emergence of a variety of platform cooperatives have only been recently examined [5,6,7,8]. Much existing research on the platform economy and cooperatives has been descriptive, rather than critically scrutinising the role of embeddedness in its structure as well as the tensions that cooperative platforms experience [9]. This paper bridges this gap by examining how alternative ways of organising work in the platform economy are being mobilized as well as what their challenges and implications are. It focuses particularly on the role of embeddedness and the tensions and challenges experienced by nascent cooperatives in the platform economy.

Barcelona, the cradle of many start-ups, including in the delivery sector, serves as a critical case for examining the recent birth of alternative delivery cooperatives. The paper is informed by the cases of three delivery cooperatives in the city of Barcelona: Mensakas, Les Mercedes, and 2GoDelivery. The paper examines the embeddedness of these nascent cooperatives in favourable governance arrangements (fostered by public policies and trade union organisations), a supportive social and solidarity economy (SSE) movement, the knowledge and professional experience of gig workers, and the territory where the economic activities are embedded. This multi-layered embeddedness is essential, but not sufficient, to explain how platform cooperatives thrive, which also requires the agency of the workers who autonomously triggered this transformation.

Next, the paper presents the literature on platform capitalism and cooperativism as well as our framework of analysis. The methods used to collect and analyse the data are then described, followed by a presentation of the cases of the city of Barcelona and the three platform cooperatives. We continue by presenting the results and then discussing them by answering our two research questions. The paper ends with conclusions as well as recommendations for future research.

2. Platform Capitalism and Platform Cooperativism

2.1. Platform Capitalism, Precarious Work, and Workers’ Responses

Platform capitalism has acquired a growing role in multiple aspects of everyday life in big cities. Platform companies, through applications on mobile phones offering multiple services, facilitate the connection between customers and workers. Depending on how the labour relationship is spatially configured, platform economy services can be classified as “crowdwork” or “place-based work” [10]. Crowdwork is performed online and connects dispersed workers, clients, and companies that do not necessarily share the same location [11,12,13], as the work is conducted online based on microtasks, such as translation, graphic design, illustration, and training activities, for which clients, companies, and workers do not need to share the same space. In contrast, “place-based work” is tied to a certain territory where the service, such as the home delivery of food, transportation, cleaning, and care tasks, is provided [14].

Both research and policy have focused on the qualities of the kind of work that platform economies generate [15]. On the one hand, there are those who value the opportunities for more efficient and competitive business development [16], allowing them to build markets from the bottom up, with an ethic based on the ideal of community. This would allow greater economic autonomy and creativity in the construction of working life [17]. On the other hand, the literature has increasingly shown how platform capitalism increases job insecurity. That is, the gig economy implies the continuity and deepening of precariousness rather than a rupture [18]. The lack of a workplace and the replacement of employees with independent contractors who provide a timely service have had devastating effects on the quality of employment [5]. Companies can use the workforce more flexibly, hiring workers only when needed, which dramatically lowers labour costs [19,20,21].

This has resulted in the deregulation of labour relations, the individualisation and erosion of existing social protection mechanisms, and, consequently, the weakening of the social power of workers [22,23]. Consequently, new forms of exploitation have emerged [15,24,25,26] with more capacity for the surveillance and control of workers [27], high demands for compliance with certain standards, strong competition between workers, isolation, and the lack of a workplace [1,28]. Platform economies have also resulted in low pay and insufficient income in the lower employment categories [15,29], increasingly unprotected workers with fewer rights [24,30], and workers with less power vis à vis the platforms [9]. The consequences have been multiple health problems [31,32] as well as stress and psychological discomfort, beyond what other labour groups may suffer [33]. Existing gender inequalities in work and in the distribution of care responsibilities also mean that platform economy work affects women more negatively [34]. In turn, this allows informal work to expand in new forms, which particularly hinders improving the working and living conditions of women [35].

Despite the individualisation and precarisation of work, workers have also demonstrated their capacity to respond to this situation [5], particularly in the delivery sector. Platform workers’ agency has taken shape in two different responses: first, by creating new forms of trade union organisations and by incorporating the claims of gig workers in traditional trade union organisations [36]; second, by creating platform cooperatives based on the principles of the SSE and constituted by the workers themselves [8].

Recent research has reported the challenges that traditional unions experience in gaining a foothold in platform companies, particularly in “crowdwork” jobs [37,38,39,40,41]. Yet, despite the organisational and cultural difficulties inherent to traditional trade unions, they are striving to respond, at times with notable success. These responses, however, have not yet been reported in the literature, with a few exceptions [5]. For example, Mcloughlin [42] (2022) showed how the Glovo riders’ strike that took place in Barcelona in 2022 resulted in the unionisation of workers and the constitution of a company committee. The holding of informal meetings, for example, while waiting between food delivery orders, has created spaces where workers can socialise, share information, generate solidarity, and start organising cooperative companies, as we elaborate on next. The importance of such space is reinforced through the simultaneous use of social networks with hybrid forms of organising [43,44,45]. The configuration of place-based work is, however, significantly different for crowdwork workers, who can find it much more difficult to organise as they do not share this bond with their territory.

2.2. Platform Cooperativism

Platform cooperativism [46,47] has been another emergent response of gig workers, who have created alternative, more democratic, and fairer online platforms based on cooperative forms of organisation. The underlying rationale is simple: take away the agent and replace the corporation with a delivery service managed by the gig workers themselves [48]. Platform cooperativism aims at benefitting cooperative members and local communities as well as prompting broader social change [47]. It adds to the earlier cooperative movement a belief in the potential of the Internet to ignite societal change. Compared with open and collaborative Internet production, the focus is on improving the workers’ conditions. In other words, platform cooperativism brings together the characteristics and potentials of digital technologies with ownership and democratic values [9]. This includes ICT commons, open-source technologies, decent work, and democratic and digital governance [49,50].

Scholz describes the key principles of platform cooperativism as being collective ownership by those who generate the profit, decent wages, transparency, a decent working environment, worker involvement in design and management, a protective legal framework, worker protections and benefits, the management of surveillance, the right to log off, and protection from inappropriate behaviour [47]. Scholz also distinguished among several types of platform cooperatives, including cooperatively owned online labour brokerages and marketplaces, city-owned platform cooperatives, producer-owned platforms, union-backed labour platforms, and workers’ cooperatives forming inside the platform economy.

Platform cooperativism is, as mentioned above, grounded in the principles of the collective organising of work. Cooperativism understands work fundamentally differently from platform capitalism, stressing non-hierarchical organising and collectivism [51], autonomy, self-management and control [52], democratic decision making and solidarity [53,54], and emancipatory practices [55]. Cooperativism also arguably resignifies work, changing it from a matter of individual transformation and competition into a practice of cooperation and social change [56].

Worker cooperatives are also believed to promote work as a creative and productive activity in opposition to the alienating, profit-driven, and deskilling processes that platform capitalism corporations impose on workers [57,58]. For example, their aim of safeguarding employment can be often accompanied by a desire to reduce the environmental footprint or increase social justice among minorities. Cooperatives thus arguably provide more stable jobs and social protections than does business as usual by reducing their profit margins and showing an ability to provide services to niche markets, such as low-income users, and job opportunities for marginalised groups, such as immigrants [9].

3. The Embeddedness and Logics of Platform Cooperatives: A Framework of Analysis

In this paper, the social and institutional embeddedness of platform cooperatives is used as the framework for answering the first research question: How are platform cooperatives, as alternative ways of organising work in the platform economy, being mobilised? The tensions arising from the adoption of market versus social logic are used as the framework for answering the second research question: What challenges do these platforms cooperatives experience, and what are their implications? In the following, we develop our framework of analysis.

Social embeddedness is fundamental for cooperatives to mobilise the necessary resources to thrive [59,60] through strong ties embedded in trust, solidarity, and reciprocity [59] and weak ties involving less frequent interactions [61]. Institutional embeddedness also shapes cooperatives’ formation, qualities, and capacities. For example, the legal framework, public policy support, and other institutional arrangements can constitute either favourable conditions for cooperatives to bloom [62] or barriers to be overcome [63,64].

Nowak and Raffaelli [65] argued that the embeddedness of social innovations, such as platform cooperatives, can be addressed as multiple and interactive layers of social and institutional embeddedness, encompassing the macro level (e.g., global economic shifts, neoliberalisation paradigms and discourses, and national policies), local institutions (e.g., local government), internal organisational characteristics (e.g., management practices and policies), and individuals (e.g., experiences of social actors in their organisations) (p. 337). In other words, platform cooperatives are intimately connected, i.e., embedded, in their social and political environment, as well as in pre-existing networks. They mirror the local context and experiences of the people creating them [7] and supporting their formation.

Platform cooperatives operating in the delivery sector have developed a particular configuration of labour relations in which work is “place-based” [10], that is, bounded to a territory (De Stefano, 2016). The digital delivery platform connects workers with restaurants and customers, but the work is still performed in a particular place. This territorial embeddedness of place-based work can facilitate workers’ agency, by organising the collective defence of their rights through protests and unionisation, as discussed above, and by facilitating the space for creating alternative ways of organising work, such as platform cooperatives, by lobbying for regulatory change, etc. [5].

The collective organising of work is as embedded in a social logic as in a market logic [66], as cooperatives engage with capitalist markets, competition, and property logics to prompt societal change [67]. Differently expressed, cooperatives aim to achieve societal goals through market mechanisms [6]. They are therefore embedded in the ambivalences of resisting precarity and exploitation, challenging but also engaging in entrepreneurialism and commercialisation [68].

As a result, cooperatives combine features of both social and business organisations. They also develop practices and strategies to navigate the tensions between different features and conflicting logics, without losing sight of their purpose of meeting social needs [69,70]. To avoid the risk referred to as mission drift, cooperatives have a considerable governance challenge: “how to handle the trade-offs between their social activities and their commercial ones, so as to generate enough revenues but without losing sight of their social purpose” [69].

Cooperatives thus can become tools that can democratise work and rehumanise economies [71]. Yet, they also risk reproducing a neoliberal paradigm whereby cooperatives succumb to capitalist pressures, abandoning their principles for market survival [72]. Another strain of research also argues that cooperatives risk being reduced to self-help entrepreneurial initiates in the context of precarious work (see Sandoval [73], for a discussion of this).

Yet, in practice, cooperatives bring together elements of discourses of cooperatives as both transformative and palliative [58]. As Kasparian [74] has argued, the everyday operation of a cooperative—like any other organisation—is messy and riddled with conflicts, the difference being the democratisation and collective management of these conflicts along more horizontal lines.

4. Method

This study is informed by a total of ten in-depth interviews with: representatives of three platform cooperatives (Mensakas, Las Mercedes, and 2GoDeliver), municipal officers and other stakeholders (CCOO officer). These three cooperatives are at the forefront of platform cooperatives in Barcelona, and although Las Mercedes and 2GoDeliver were more recently established than Mensakas, they are all well known in the sector and financially sustainable. We chose these three cooperatives in Barcelona, as the city is at the forefront of both the platform economy and the nascent platform cooperative movement in Europe. Barcelona is also a paradigmatic case of a city with a historical, political, and social environment supporting SSE, as we elaborate on below, making the city a critical case [75] in which to examine nascent and alternative social innovations in the platform economy.

Informed by this “critical case” approach, we have selected as favourable a setting as possible, one of the leading cities in Europe for proactively supporting the development of SSE in the digital platform economy, in which to examine the role of embeddedness in nascent platform cooperatives. A critical case approach provides the opportunity to draw valid insights from a single case that has strategic importance for a general problem, such as the challenges that nascent cooperatives face, the tensions they navigate, and their implications.

Interviews with cooperative workers and municipal officers were conducted in person and virtually in April and December 2022 by the two researchers from Barcelona for the purpose of observing the dynamics, evolution, and changes in these cooperatives’ practices, challenges, and implications. Additional interviews with municipal officers were conducted in person in April 2022 by the third researcher. The second round of interviews with co-op workers in December 2022 was particularly important to improve our understanding of the evolution and consolidation of two of the youngest cooperatives, Las Mercedes and 2GoDeliver. We conducted interviews with the designated spokesperson of each cooperative. We also conducted interviews with key stakeholders supporting the creation and consolidation of the platform cooperatives in Barcelona. For example, we interviewed the secretary of New Realities of Work and SEE of Comisiones Obreras (CCOO) in Barcelona (until April 2022), and three officers of the Department of SSE in the city of Barcelona. The interviews with cooperative workers focused on their personal experiences and perceptions of the arrangements supporting the creation of the cooperatives, as well as their interpretations of the tensions and challenges they addressed in that process. The interviews with municipal and trade union officers served to contextualise and validate part of the information stemming from the interviews with cooperative workers, mostly regarding the embeddedness of the cooperatives in local institutional arrangements.

All interviews were recorded and then transcribed verbatim. Furthermore, we also conducted a search of communication and social media to understand the events preceding the formation of the cooperatives as well as examining documents generated by the cooperatives and other supportive organisations. The limited representation of interviewees from the three cooperatives nevertheless has implications for the interpretation of these three cases, as other internal voices were not incorporated, but rather those of the representatives and founders of these cooperatives.

As the two researchers conducting the interviews live, work, and conduct part of their research in Barcelona, their previous fieldwork in related studies provided privileged knowledge compensating for the limited representation of interviewees, helping us understand and contextualise the data stemming from this study. While consideration of the rationales and factors explaining the formation of the cooperatives (question 1) was triangulated using different sources of data (e.g., the media, previous interviews, and existing literature), consideration of the challenges and tensions experienced by these cooperatives (question 2) was more exploratory and limited to the experiences of the interviewees, calling for further research, as we elaborate in the conclusions.

The interview transcripts and selected documents were submitted to content analysis with a focus on the two research questions concerning how the cooperatives were created, as well as their challenges and implications. Our analytical strategy was abductive, as it combines a concrete theoretical starting point (i.e., the embeddedness and logics framework) with a close connection between empirical observations and the themes that account for them. As a result, the analysis was conducted iteratively between collecting, sorting, coding, and proofreading the data, and discussing our preliminary findings with the participants in the second round of interviews [76]. The first coding sought issues related to the rationales and factors underlying the creation of the cooperatives as well as the effects and the tensions that the cooperatives had to navigate. It resulted in the emergence of common categories explaining the formation of the three cooperatives, the challenges experienced and their implications: trade union support, regional and local governments, the cooperative movement, the SSE movement, and issues of space and knowledge. In a second-order analysis [77], consisting of an iterative process shifting between data analysis and theory, the practices were grouped into two overarching categories in order to answer our two questions: (1) social economy, governmental, knowledge, and territorial embeddedness; and (2) social versus market logics. All these themes emerged in the three studied cooperatives, although with different nuances as we elaborate in the results and discussion.

5. Barcelona, Cooperative City

Catalonia has a long cooperative tradition [78]. From the mid-nineteenth century until the Spanish Civil War in 1936, there was a strong cooperativist tradition in the region that was interrupted by Franco’s dictatorship. With the restoration of democracy in 1978, the cooperative movement started recovering strength. From the mid-1990s to the early 2000s, SSE networks such as the Xarxa d’Economia Solidaria (Network for the Solidarity Economy) emerged. Since 2015, with a new progressive political party leading Barcelona City Council, the local government in collaboration with other SSE actors developed first the Impetus Plan for SSE in the City of Barcelona, 2016–2019, and later the Barcelona 2030 SSE Strategy [79]. The Barcelona 2030 SSE Strategy outlines eight strategic lines of work that crystallise in ten city projects, one of them supporting the creation of the cooperativism hub of Barcelona, Coopolis, located in Can Batlló, in the Sant neighbourhood. Can Batlló, hosting Coopolis, is today considered the largest centre of cooperativism in southern Europe, being the home of more than 80 cooperatives. This centre is managed by Associació Bloc 4 (Bloc Association 4), formed by Coopolis, the Federació de Cooperatives de Treball (Federation of Working Cooperatives), the Fundació Seira (Seira Foundation), and the Confederació de Cooperatives de Catalunya (Cooperative Confederation of Catalonia), with the support of Barcelona City Hall. As a result of these different processes, a dense civil society-driven and public ecosystem has been developed to support the SSE.

Other city councils in the Barcelona Metropolitan Area have also developed policies to support the SSE. For example, the neighbouring city of El Prat offers financial and technical support to encourage the creation of cooperatives. El Prat also created a social innovation business lab, Labesoc. This initiative is headed by GATS—Grupos Asociados por el Trabajo Social, Cultural, Ambiental y Comunitario (Associated Groups for Social, Cultural, Environmental and Community Work)—formed in 2000 in the region of Baix Llobregat, with support from city hall and other public administrations. The favourable institutional arrangements created by several neighbouring municipalities are particularly relevant because cooperatives, as businesses selling services and products, operate beyond municipal borders.

Furthermore, the Generalitat de Catalunya (Catalonia Regional Government) has implemented policies to support the cooperative sector through the Singulars Programme, as part of its economic growth strategy to boost employment and the creation of new businesses and markets. For example, a grant line is available to support the SSE by creating cooperatives and fostering inter-cooperative projects.

The new phenomenon of platform capitalism and the precarious work it generates has, nevertheless, not gone unnoticed by the SSE movement in Catalonia, which has supported the mobilisation of nascent cooperatives. Delivery platforms entered Spain with Deliveroo in 2015. That same year, Glovo was born in Barcelona and is now the third-largest such platform in Spain [80]. Initially, the riders were self-employed, a situation that worsened their working conditions and social benefits. Complaints and mobilisations followed, organised by the Riders X Derechos workers’ association, which was founded in Barcelona and later spread to Madrid and Valencia with the support of different unions and activists [5]. Thereafter, the support of unions such as CCOO, UGT, and CGT also grew. As a result of these actions, and the social and media pressure, the Rider Law was passed in August 2021 decreeing the obligation for companies to employ delivery workers and to inform them about the algorithms affecting them.

Simultaneously, delivery cooperatives have been created, manifesting the values of the SSE. Not in vain, Spain is among the countries that have recently developed platform cooperativism with the greatest intensity [81].

6. The Three Nascent Platform Cooperatives: Mensakas, Las Mercedes, and 2GoDeliver

6.1. Mensakas

Mensakas emerged in 2017 from the first protests organised by Riders X Derechos. This cooperative reinvests all its profits in the organisation, and it is governed by democratic values of equality and equity. One example of how it strives to live up to its values is that Mensakas initially worked only with either restaurants affiliated with the SSE network or with local businesses upholding like-minded values, with the aim of promoting local businesses and responsible consumption. Mensakas also aims to create workplaces with decent working conditions. For example, it pays all female workers 5% more than their male peers as a symbolic gesture against the salary gap and the harassment and disrespect that female workers suffer during the workday.

One of the main challenges Mensakas faces is that of owning the means of production, that is, the digital application. To overcome this obstacle, Mensakas uses an open-source application developed by CoopCycle, an international cooperative federation. Being part of CoopCycle allows the co-ownership and use of the digital platform by the federation members, such as Mensakas.

Mensakas is growing and strengthening its ties with other organisations. The cooperative has developed a last-mile service, which assembles goods and delivers them to stores. It has also expanded its portfolio of restaurants. Yet, unlike conventional companies, Mensakas charges less than a 20% commission to businesses and less than five euros to the end user. They have also expanded their collaborations with other initiatives in the SSE, for example, with other delivery cooperatives. Another effort is the creation in 2022 of Som Ecologística (We are Eco-logistic), a second-tier cooperative that pools services among several cooperatives.

6.2. Las Mercedes

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the collapse of international tourism arrivals, a group of tour guides from a bicycle tour company in Barcelona decided to provide delivery services through a platform co-op. Unlike most other platform cooperatives, Las Mercedes arose because of the need for alternative employment during the COVID-19 pandemic and the opportunity presented by the rise of food delivery demands, rather than in response to precarious work. The transformation to the new sector was facilitated by projects and subsidies funded by Barcelona City Council. For example, Las Mercedes received support from Barcelona Activa (the Barcelona Employment Agency), within the Camí a la solidesa (Way to solidarity) programme. It was also supported by MatchImpulsa, a project driven by the Open University of Catalonia together with Barcelona Activa to promote the digitisation of the SSE.

Since its founding, Las Mercedes has specialised in providing reliable courier services. At present, they work mainly with local producers, mostly providing business-to-business (B2B) delivery services for businesses such as confectioneries, bars, and restaurants and, to a lesser extent, for companies, caterers, and households. Las Mercedes decided to specialise in this B2B niche because household food delivery orders require an immediacy of service that, due to the characteristics of the cooperative, cannot be ensured. Yet, despite the difficulties, Las Mercedes is in the process of consolidating the Bol en bici (Bowl on bike) project, together with Reusabol (Reuse bowl), a reusable packaging company. This project consists of a digital platform that gathers a selection of restaurants offering takeaway food services in returnable containers.

As a result of the reactivation of the tourism sector after the pandemic, one of Las Mercedes’ members decided to return to previous employment in tour guide services. The cooperative continued growing and today consists of four members plus three employees. The last employee hired was a male, since the cooperative found it difficult to recruit a woman with an appropriate driving license, which is indispensable as the cooperative also uses an electric motorcycle to facilitate the workload. As a result of collaboration with organisations working within the SEE to support labour reintegration, Las Mercedes is now aware of the lack of women with this permit, which is a great impediment to the integration of women in this sector.

6.3. GoDeliver

The most recent of these cooperatives is the 2GoDeliver platform. It was created by the Cooperativa Unión de Repartidores y Servicio Bajo Demanda, legally constituted in mid-2021 by 24 associated workers who had previously worked as riders, most of them foreign-born and five of them women. 2GoDeliver was created because of the uncertainty characteristic of the sector, disagreement with the Rider Law, and incredulity regarding its enforcement and the transformation of gig workers into waged employees. In this context, these workers started looking for alternatives, exploring the previous professional capacities that they had developed in their countries of origin to design and start this cooperative.

One of the challenges was, as with Mensakas, creating a well-functioning and attractive app. 2GoDeliver decided to create its own digital platform. To do so, the cooperative members crowdfunded the costs and commissioned the design of their own app through contacts with other Venezuelan migrants, residing in Chile and the United States, who had experience in the IT sector. With this app, 2GoDeliver can now connect users, restaurants, and delivery workers directly, as well as provide a payment service.

Apart from its own resources, 2GoDeliver has received some public subsidies from the Generalitat de Catalunya through the Singulars Programme, El Prat City, and Labesoc, the social innovation incubator in El Prat. The Comisiones Obreras trade union has also supported the co-op, for example, by providing advice as well as access to their premises for the cooperative office, meetings, and assemblies.

2GoDeliver’s growth strategy is based on the creation of new cooperatives that can provide service to small areas in the territory, each with a radius not exceeding 3.5 km and connected to the 2GoDeliver platform. The underlying rationale is to compete with large platforms by offering substantial delivery capacity in a delimited territory. Accordingly, the strategy is to add new cooperatives that, under the same brand and platform, expand the service provided in the territory.

For 2GoDeliver, the delivery sector has become increasingly important and widespread in society. 2GoDeliver claims that it is the oligopoly of a few large corporations that control the market and the labour force that causes harm: to delivery workers with their low incomes; to restaurants, particularly small ones, due to the high commissions; and to users, due to the poor service they receive. 2GoDeliver argues that a new balance is necessary. Consequently, this platform cooperative aims to improve the working conditions of the riders, as well as their professional training, which allows them to provide better service. The cooperative is also considering reducing the fees charged to businesses, which are currently below 18%. Large corporate platforms, according to the interviewees, charge restaurants 35–40%, despite formally claiming to charge percentages of 25%, 22%, or 18%. These low percentages are only charged occasionally, according to the same sources.

7. Results and Discussion

In this section, our results are presented and discussed in light of the existing literature. The section is structured by the two research questions. The first part discusses how platform cooperatives, as alternative ways of organising work in the platform economy, are being mobilised with the support of the social and institutional embeddedness framework. The second part discusses the challenges that these platforms cooperatives experience and their implications, informed by the analytical framework of market versus social logics.

7.1. The Multi-Scalar Embeddedness of Nascent Platform Cooperatives

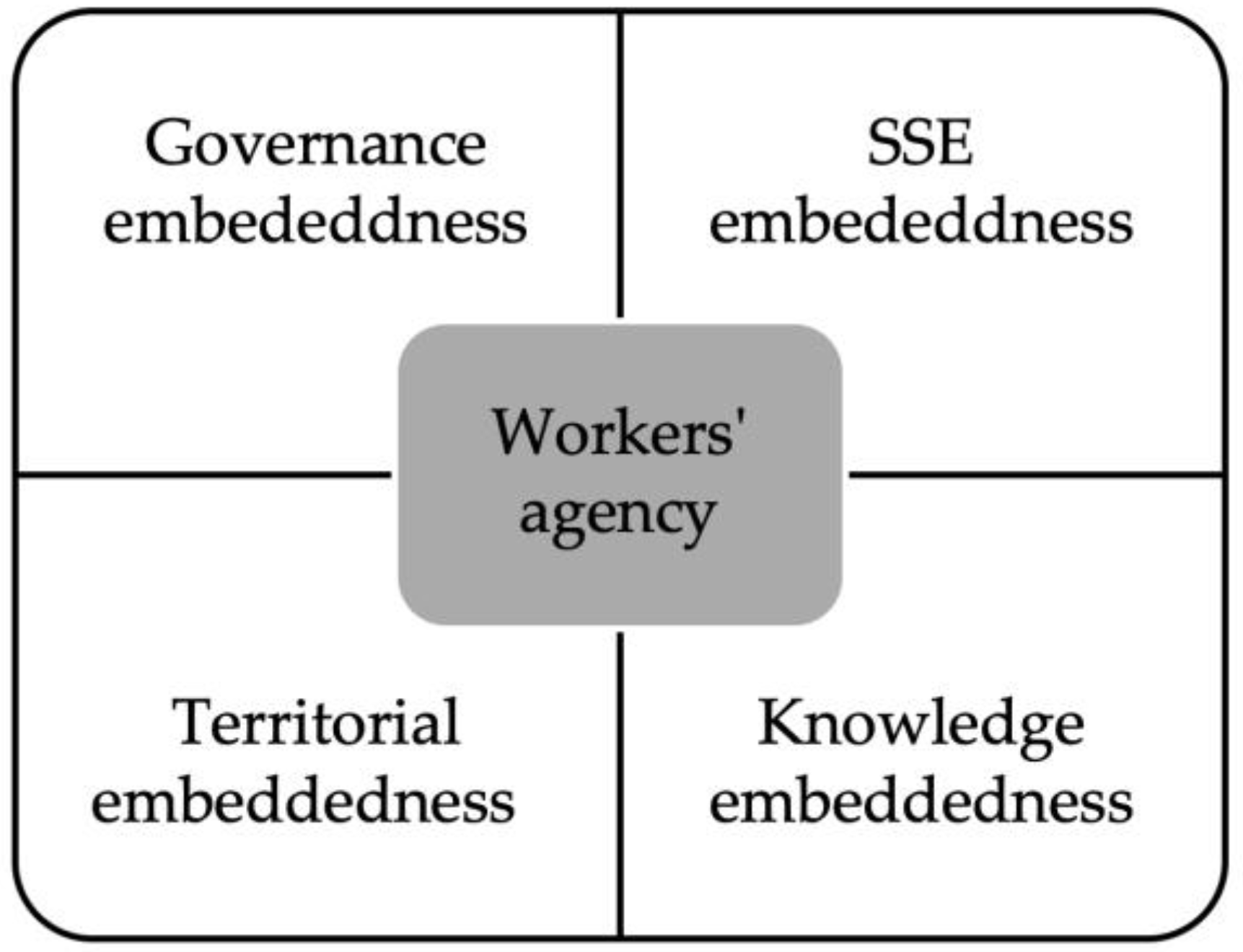

In this section, we discuss how these nascent platform cooperatives mobilised the necessary resources to thrive, by examining their embeddedness in (1) governance arrangements (e.g., national institutional arrangements, trade unions, local and regional government support, and SSE policies), (2) the SSE movement, (3) territory, and (4) knowledge. These are the themes that emerged from our content analysis and that are represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The embeddedness of platform cooperatives.

7.1.1. Governance Embeddedness

The background to the formation of Mensakas and 2GoDeliver in Barcelona was the depletion of a labour market model that generated precariousness, social unrest, and the consequent diverse responses of different actors, ranging from the first strikes in spring 2017, through the organisation of the first union responses (e.g., Riders X Derechos), to the creation of cooperatives (e.g., Mensakas following the 2017 protests and supported by Riders X Derechos):

The strikes started in 2017, we got fired, and in 2018 Mensakas was born from the Riders X Derechos movement. We liked that job, but we didn’t like the conditions and we didn’t accept that innovation and digitalization meant a lack of labour rights.(Mensakas)

Similarly, the weak enforcement of the recent Rider Law (August 2021), the consequent lack of compliance on the part of platforms such as Glovo, and the distrust of many workers of the transformation of self-employed platform workers into salaried workers also contributed to a climate of discontent. This climate was propitious for the innovation of collective ways of organising work in the sector, as the formation of the cooperatives 2GoDelivery, Mensakas, and Las Mercedes shows. In the case of the latest cooperative, Las Mercedes, the members used to work as tour guides for international students. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the decrease in international tourism activity, they decided to form a delivery cooperative. Therefore, Las Mercedes was also born from the necessity of improving its members’ working situation, although triggered by other events.

Initially, more alternative unions such as Intersindical Alternativa de Catalunya provided support for the formation of syndical organisations such as Riders X Derechos in 2017 [5], which in turn supported the creation of the cooperative Mensakas. Mainstream trade unions such as Comisiones Obreras also underwent internal change to develop structures that facilitate the support of platform workers. For example, in 2019 a new department was created within Comisiones Obreras, the New Realities of Work and the Social and Solidarity Economy. One initial output was the research report Digital platform workers: Labour conditions, needs, demands and perspectives, which constituted the first effort to examine the needs of gig workers in this emergent sector. CCOO also supported the strike in Barcelona in 2021 and provided other supportive services such as advice and the provision of office space for cooperatives such as 2GoDeliver:

We decided to form a cooperative thanks to the support provided by X and Y through Comisiones Obreras Trade Union.(2GoDeliver)

That some of these nascent cooperatives arose as a result of their embeddedness in a favourable union institutional arrangement is a finding consistent with previous research elsewhere [82] and with other workers’ struggles in the digital economy [61]. Nevertheless, this embeddedness must be viewed in a nuanced way, as the formation of these cooperatives was the result of the autonomous efforts of delivery workers:

Beyond the crucial support of trade unions, L’Ateneu Cooperatiu, or public subsidies, Mensakas exists because of our capacity to resist. This resistance is possible because of the relationships among us, which have made us endure where others have not. We have crucial support, but we are the result of our own self-organization. They have not looked for us; it is we who have looked for who could support us.(Mensakas)

Together with trade unions, local and regional governments have also played a significant role in the configuration of an ecosystem of sympathies and alliances favourable to the articulation of nascent platform cooperatives by the agency of workers. It is no coincidence that these emergent cooperatives emerged in Barcelona. The rise of these cooperatives is intimately connected to the local governance structures of the city of Barcelona and its metropolitan area and to the practices and values embedded in the SEE, which have a deep tradition in the city. Barcelona is one of the metropolitan areas at the forefront of the SSE in Europe, supporting cooperatives and the local economy to foster more sustainable urban development. Just a few examples of the innovativeness of the city in the SSE are the creation of several organisational units working with SSE (e.g., the office of the Commissioner for the Social Economy, Local Development, and Food Policy; the Directorate of Social and Solidarity Economy Services and Sustainable Food; and the Department of the Social and Solidarity Economy) and the design and implementation of the Impetus Plan for SSE in the city of Barcelona (interview, municipal officer).

These institutional arrangements have created a favourable context in which cooperatives can thrive (as previously reported by Muñoz and Kliber) [62] through, for example: municipal subsidies supporting the electrification of Las Mercedes’ bikes as part of a green project to reduce traffic, noise, and air pollution [7]; Barcelona Activa and other municipal agencies supporting cooperatives such as Mensakas; the Labesoc social entrepreneur incubator facilitating the creation of cooperatives such as 2GoDeliver; regional government programmes such as Singulars supporting the seed capital to start up 2GoDeliver; and other public programmes such as Match Impulsa supporting Las Mercedes cooperative through training, advice, and seed funding.

Institutional arrangements can nevertheless also turn into barriers to be overcome [63,64]. One downside of this favourable institutional environment is the time spent on applications and the corresponding bureaucracy. Another is the lack of continuity in supporting cooperatives after they have been created, as the cooperative members complained about in our interviews:

Rather than subsidies what we need is work (e.g., in the form of procurement of their services), stable work.(Mensakas)

7.1.2. SSE Embeddedness

The organisation of the first strikes in 2017 also prompted the creation of new connections with the international cooperative movement and led to the hosting of the Second Transnational Federation of Couriers conference in Barcelona in April 2019 [5]. These international networks provide knowledge and support that are crucial for the imagination of the alternatives and their formation.

Similarly, the embeddedness of platform cooperativism in organisations operating at both the local and global levels, and the interaction between these two levels, is also a significant resource for the creation of new cooperatives [7,82]. The role of Coopcycle was, for example, fundamental for Mensaka, by providing open access to the digital platform and supporting the initial crowdfunding to start the cooperative [5]:

Coopcycle is more than an app, it’s the fact of coming together to strive towards the same objective, and sharing values such as sustainability, the cooperative movement, etc., [that matter].(Mensakas)

The nascent cooperatives are not only embedded in the global cooperative ecosystem; their business activities are also aligned with their environmental values:

We only use bicycles and electric vehicles. We contract electricity services from a green energy company… We know with whom we don’t want to [work], with those who are not aligned with us.(Las Mercedes)

Their customer portfolio is also embedded in the local grassroots of the city. Synergies were created with other cooperative organisations to whom they could deliver services (e.g., Coòpolis) or with the local SSE ecosystem (e.g., Mensakas and Som Ecologistica). The latest is the case of Mensakas, which is strongly rooted in the SEE having strong political values of solidarity, gender equality, and relations with other cooperative businesses as customers, as we elaborate on next. Similarly, 2GoDeliver and Mercedes also received support, for example, from the social incubator Labesoc in El Prats, showing that commitment to the SSE goes beyond the boundaries of the City of Barcelona.

7.1.3. Territorial Embeddedness

The new cooperatives were also embedded in the local territory, in their neighbourhoods’ communities and businesses. For example, Mensakas has developed strong connections with the SEE business community. Mensakas started looking for cooperative restaurant members of the Federació de Cooperatives de Treball de Catalunya (Catalan Federation of Work Cooperatives) to offer them their delivery services. Initially, they only worked with restaurants or local businesses in the neighbourhood to promote the local economy and responsible consumption. Las Mercedes also works with local businesses or restaurants that promote vegan food, “restaurants supporting seasonal and locally produced food” (interview, Las Mercedes), and restaurants supporting other environmental values, through the “Reci-bowl” project. Both the Mensakas and Las Mercedes cooperatives refuse to work with multinational companies and franchises:

We always try to work with these types of business or local initiatives. We would never work with McDonalds… We do not collaborate with any organisation against our values. Behind what we do there is a political idea of the city we want, of how we think resources have to be distributed. Our activity fits well within the SSE right now.(Mensakas)

As the Mensakas member states above, the co-ops’ economic activities are embedded in local businesses with which they share like-minded values. The territorial embeddedness of the three cooperatives is also translated into the fees they charge local businesses, which are lower than those of platform corporations, as they all acknowledge the exploitation of local businesses and restaurants:

We noted that we could charge a lower fee [to the restaurants]. We can charge a more balanced fee to avoid drowning small business … and we have learnt that with these lower fees the business model is sustainable. When we present this to restaurants, and they compare the fees to [those of] other platforms, they do not believe it!(2GoDeliver)

The strategies of the three cooperatives differ, however, here in the kinds of local connections they make to embed their economic activities in the social and urban fabric. Mensakas has explicitly developed strong connections with the SEE community as well as a more critical and radical discourse about the platform economy, mirroring its supportive organisations. In contrast, 2GoDeliver draws on its strong ties [83] to global migrant communities, for example, developing its digital platform using Venezuelan migrants living in the USA or Brazil.

By embedding its activities in its neighbourhoods, 2GoDeliver also facilitates the formation of new cooperatives in El Prat, Hospitalet, Badalona, and Tarragona, sharing its platform software and costs, to compete through this form of scaling up with large operators. By so doing, 2GoDeliver “re-scales” [84] and reconnects distant migrant communities within the city and beyond through trans-local migrant networks [85,86].

To conclude, territorial embeddedness [87] is revealed to be crucial for the mobilisation of these cooperatives. First, the space and territory where riders meet facilitated interactions between platform workers, who, in turn, initiated protests and mobilisations [5]. For example, meeting in the zone centres to collect deliveries or in Telegram groups created for internal communication provided space in which to socialise and exchange information. This process was also supported by changes in some platform corporations providing a guaranteed income per hour, which relieved the pressure to rush and gave riders the time to meet “the riders beside you, to meet the people beside you, to share your problems and organise ourselves” (interview, Mensakas). Second, the territory also enables the cooperatives to embed their economic services in social relations and organisations with like-minded values within, across, and beyond the city.

7.1.4. Knowledge Embeddedness

Another common feature is that the economic activities of the three cooperatives are embedded in the knowledge and professional experience of the workers. For example, a member of Las Mercedes “had been working as a chef for years” (interview, Las Mercedes), and her professional knowledge was useful in improving the quality of food handling. She has trained other members to provide high-quality food delivery.

Mensakas, the oldest of the three cooperatives, had a younger membership, many of them university graduates, who had worked in the delivery sector to support themselves while studying. Mensakas members could draw on their education (e.g., in journalism and communication) to start running the business. They lacked, however, commercial and business experience, which was a challenge when establishing the cooperative. Being the first platform cooperative created in Barcelona also implied experimentation, as the SSE movement was still inexperienced in the field of digital platforms and there has been lots of learning by doing.

In 2GoDeliver, other Venezuelan migrants living in Chile and the USA, with knowledge of IT services, were contacted by their compatriots to develop the app. This is a clear example of how trans-local migrant networks [85,86] operate at different scales, linking together far-flung communities sharing a similar background [84]. Additionally, 2GoDeliver drew on the previous experience of its members both in business management in their countries of origin and in the delivery sector working for other platforms in Barcelona. This experience was extremely helpful, not only in starting the business but also in building the client portfolio:

We observed that we, as foreign-born workers, together had the different backgrounds necessary for a business like this: administration, law, marketing, etc. Additionally, we decided to form the platform.(2GoDeliver)

This finding is consistent with previous findings that cooperative members bring with them experiences of their work before cooperative formation [7]. It is also consistent with how other social movements in very precarious contexts draw on tacit knowledge as a resistance strategy [88]. Precarious workers in the platform economy are heterogeneous and bring together diverse experiences and backgrounds that became resources in the newly formed cooperatives.

7.2. Challenges and Implications

The impacts of working in these platform cooperatives are many. They facilitate the labour integration of minorities—disproportionally affected by the economic and pandemic crises—such as immigrants (e.g., Mensakas and 2GoDeliver) and women (Las Mercedes) [7]. They improve the working conditions of platform workers, offering better and more limited schedules, working under less delivery pressure (Las Mercedes), and focusing more on the B2B niche. They also provide more stable earnings and the capacity to participate in decision-making. On the other hand, sustaining the cooperatives relies on individual sacrifices due to personal and collective commitment to the cooperative and, at times, self-exploitation.

The study of the three cases opens up a repertoire of rationales for and ways of organising work collectively in digital platforms that is not exhaustive. Mensakas mirrors the SEE movement in which it is embedded. 2GoDeliver is driven by an economic rationale, a focus on mainstream markets, strong connections with migrant “glocal” communities, and a scaling-up strategy supporting the creation of small cooperatives operating intensively in small territories. Finally, Las Mercedes is built on the opportunity to develop a market niche for smaller, independent cooperatives to provide alternative and green transport solutions in progressive cities.

These three platform cooperatives have developed a set of practices that defy the hegemony of the established norms of the platform economy regarding economic injustice and precariousness, a logic of cooperation versus logics of competition, gender inequality, environmental impact, and migration, as we elaborate on in the following. First, a common feature of the three cooperatives is the lower and less exploitative fees charged to the businesses using their services. Cooperatives also construct a narrative that questions the platform economy and its business model. They describe how this model is intrinsically unfair and ultimately sustained by the artificially low prices paid by consumers which constrain how much platform cooperatives can adjust their fees and benefits:

[The service] is not cheap. The final customer is not paying [the total costs of the service]. It’s the rest who pay—the rider who is exploited, the restaurant, etc.(Mensakas)

Second, despite cooperatives’ need to compete with other businesses for survival, their strategies are pervaded by a logic of cooperation rather than competition. They introduce values and practices of cooperation in organising their work, by collaborating with other cooperatives as customers to which they provide their services. They also introduce a logic of cooperation by facilitating the creation of new cooperatives in other neighbourhoods through scaling-up strategies (e.g., 2GoDeliver) [7] in order to compete with large corporate platforms. Nevertheless, rather than replacing large corporations, some of the platform cooperatives such as Mensakas and Las Mercedes have created alternative circuits of food delivery and consumption, as Sandoval [73], Grohmann [89], and Salvagni et al. [7] have previously observed. Other cooperatives (e.g., 2GoDeliver) are competing for the same mainstream market but through articulating collaborative strategies to support the formation of new cooperatives by other workers, in order to scale up their shared digital platform.

Another example is how the gender gap is critically addressed by two of the cooperatives. Mensakas took concrete initiatives to create more egalitarian workspaces by raising female workers’ pay 5% over men’s “as a symbolic act to bridge the wage gap… and [to compensate for what] women suffer in the courier service in comparison with men” (interview, Mensakas). Las Mercedes is a women’s cooperative as it has the aim of reconciling work and motherhood. In so doing, it blurs the boundaries between productive and reproductive work in this platform cooperative. Las Mercedes also prioritises environmental values, upholding them across the organisation, its product portfolio, and practices.

Finally, the challenges posed by a labour market that discriminates against employees with a foreign background have led to the overrepresentation of the immigrant community in the gig economy. This is also mirrored in the predominant participation of foreign-born workers in two of these platform cooperatives. Simply by creating alternative ways of organising work for discriminated-against collectives such as immigrants, these cooperatives challenge the hegemony of the established norms of the platform economy. While cooperatives such as Mensakas have developed specific measures to compensate this group, others such as 2GoDeliver, consist completely of foreign-born workers, are connected to migrant businesses, and developed thanks to foreign digital know-how. All this resonates with how recent research on platform cooperativism accounts for the potential to redesign the platform economy in the interest of social justice [90,91] in terms of the economic, gender, environmental, and cultural diversity dimensions.

The findings also show how the three platform cooperatives combine social and market logics to prompt change to different degrees. 2GoDeliver focuses on the strategy of growing and scaling up its platform by facilitating replication by other workers in other locations and, by so doing, competing with large corporate platforms:

New groups test our platform for one or two months—“Are you going to create a delivery node?” … If not, we can’t renew the contract.(2GoDeliver)

Discursively, Mensakas and Las Mercedes uphold a social logic by explicitly addressing values of environmental sustainability, social justice, and gender equity. To what extent these values correspond to practice and do not conflict with the financial sustainability of these cooperatives remains to be seen and goes beyond the scope of this study. The risk of platform cooperatives succumbing to a market logic of competition and growth [6] and reproducing the contradictions of the platform capitalism model [81] remains as a question for future research.

8. Conclusions

Informed by the case of platform cooperatives in Barcelona, this paper has examined how alternative ways of organising work collectively in the platform economy are being mobilised, as well as what their challenges and implications are. The paper makes a twofold contribution to the emergent body of literature on platform cooperatives. First, it concludes that all forms of embeddedness in governance arrangements—in the SSE movement, in workers’ knowledge, and in the territory where workers work and live—are essential: none alone is sufficient to mobilise the necessary resources for platform cooperatives to thrive. Despite the relevance of the multi-layered embeddedness of these cooperatives in existing structures, networks, and governance arrangements, the paper also shows how the agency of these workers, who are among today’s most precariously employed, remains crucial to initiating this transformation. The paper also confirms how platform cooperatives and their workers can appeal to different scales [5], ranging from the global to the very local—that is, from their inclusion in global cooperative movements to their territorial embeddedness in the neighbourhoods where they operate. It also identifies the role of trans-local immigrant networks and their agency in rescaling and reconnecting communities within the city and transnationally by forming multi-scalar relations, typical of migrant communities [84,85,86].

Second, our study helps demonstrate how territorial embeddedness [87] is crucial for the mobilisation of platform cooperatives operating in place-based platform economies. The space and the territory where riders meet facilitate worker interactions that give rise to mobilisations and to the exchange of knowledge and ideas [5]. Although platform corporations have tried to erode these spaces that facilitate worker exchanges, paradoxically, this aggression was answered with protests and resistance that ultimately led to platform cooperative formation. We also show, for the first time, how the territory facilitates the embedding of platform cooperatives’ economic services within social relations, institutional arrangements, knowledge, and like-minded organisations within, across, and beyond the city. The cooperatives’ strategy is to embed their economic activities in delimited territories and to expand their services through cooperation with other cooperatives and actors with which they can share infrastructure costs while strengthening their collective voice.

The present study has certain limitations, however. The most important is the exploratory nature of our examination of the challenges and implications of these nascent cooperatives since our data are limited to the voices of cooperative representatives. Further research is necessary to examine in greater depth the tensions and conflicts experienced by cooperative members and the ways these can be resolved in a democratic workplace [73,74].

The different examined ways of organising work collectively, together with their underlying rationales, as represented by the three cooperatives, are, however, not exhaustive. Platform cooperatives are a nascent phenomenon, still underexamined. Further research is necessary to investigate the different organisational forms and rationales of platform cooperatives, and their relations with the social, institutional, territorial, and knowledge embeddedness of these organisations. Future studies should also explore how different forms of territorial embeddedness shape the formation of platform cooperatives based on crowdwork, rather than place-based work, and to what extent this factor is determinant or not.

Another research avenue would be to comparatively analyse different scaling strategies, as well as strategies of networking, federation, and cooperation between platform cooperatives, that could strengthen cooperatives’ capacity to grow and increase their advocacy power. More studies are also needed to understand how changes in platform corporations affect the organisation of their services, the profile of their workers, and these workers’ corresponding responses in terms of unionisation or cooperative formation. A final research avenue would be to identify and evaluate diverse public policy strategies for supporting platform cooperativism in different national and local contexts. As Barcelona is a critical case, it represents a very favourable context for the emergence of these cooperatives. How to understand the role of embeddedness in less favourable contexts is another question remaining for future research.

Finally, the policy implications of this study suggest a need to strengthen the support for nascent platform cooperatives from public organisations, trade unions, and SSE networks, particularly during the process of operational consolidation. Although our study examines a favourable context for the emergence of these alternative forms of work organisation, it also confirms the insufficient continuity of that support. Meriting exploration is the role of the public procurement of courier and delivery services reserved for platform cooperatives, part of a growing trend to support services and goods provided by social enterprises and work-integration social enterprises. Another avenue of institutional action would be to support the digitalisation of the SSE, to facilitate the incorporation of workers’ cooperatives in the platform economy. This would allow workers to access the greater creativity, economic autonomy, and working-life flexibility promised by the platform economy, but to the benefit of workers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.C. and C.I.; Methodology, E.C. and C.I.; Formal analysis, C.I. and M.J.Z.C.; Investigation, E.C. and C.I.; Writing—original draft, E.C., C.I. and M.J.Z.C.; Writing—review & editing, E.C., C.I. and M.J.Z.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Post-doctoral grant funded by the Ministery of Universities of Spain, funded with Next Generation funds in the framework of the Plan for Recuperation, Transformation and Resilience managed by the University of Baleares Islands: Programa de Ayudas Margarita Sala; Grant PID2020-114186RB-C21 funded by MCIN-AEI/10.13039/50110001103; Swedish Research Council: 2019-02109, “The changing role of local governments in labour market integration”; Swedish Research Council for Health Working Life and Welfare: 2016-07205, “Organising Integration”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- De Stefano, V. The rise of the “Just-in-Time Workforce”: On-demand work, crowdwork, and labor protection in the gig economy. Comp. Labor Law Policy J. 2016, 37, 471–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schor, J.B.; Attwood-Charles, W.; Cansoy, M.; Ladegaard, I.; Wengronowitz, R. Dependence and precarity in the platform economy. Theory Soc. 2020, 49, 833–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunders, D.J. Gigs of their own: Reinventing worker cooperativism in the platform economy and its implications for collective action. In Platform Economy Puzzles; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; pp. 188–208. [Google Scholar]

- Schor, J.B. Debating the sharing economy. J. Self Gov. Manag. Econ. 2016, 4, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Muñoz, K.; Roca, B. The spatiality of collective action and organization among platform workers in Spain and Chile. Econ. Space 2022, 54, 1411–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, M. Entrepreneurial activism? Platform cooperativism between subversion and co-optation. Crit. Sociol. 2020, 46, 801–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvagni, J.; Grohmann, R.; Matos, É. Gendering platform co-operativism: The rise of women-owned rider co-operatives in Brazil and Spain. Gend. Dev. 2022, 30, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, T.; Mannan, M.; Pentzien, J.; Plotkin, H. Policies for Cooperative Ownership in the Digital Economy; Platform Cooperativism Consortium, Berggruen Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.berggruen.org/ideas/articles/policies-for-cooperative-ownership-in-the-digital-economy/ (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Scholz, T. Plattform Cooperativism. Challenging the Corporate Sharing Economy; Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, H. Labour geographies of the platform economy: Understanding collective organizing strategies in the context of digitally mediated work. Int. Labour Rev. 2020, 159, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.; Furrer, M.; Harmon, E.; Rani, U.; Silbderman, M.S. Digital Labour Platforms and the Future of Work: Towards Decent Work in the Online World; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Howcroft, D.; Bergvall-Kåreborn, B. A typology of crowdwork platforms. Work Employ. Soc. 2019, 33, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.; Hjorth, I.; Lehdonvirta, V. Digital labour and development: Impacts of global digital labour platforms and the gig economy on worker livelihoods. Transfer 2017, 23, 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Sun, P. Temporal arbitrage, fragmented rush, and opportunistic behaviors: The labor politics of time in the platform economy. New Media Soc. 2020, 22, 1561–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schor, J.B.; Attwood-Charles, W. The “sharing” economy: Labor, inequality, and social connection on forprofit platforms. Sociol. Compass 2017, 11, e12493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippas, A.; Horton, J.J.; Zeckhauser, R.J. Owning, Using and Renting: Some Simple Economics of the “Sharing Economy”; National Bureau of Economic Research; Working Paper No. 22029; Cambridge, MA USA, 2016; Available online: http://john-joseph-horton.com/papers/sharing.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Fitzmaurice, C.J.; Ladegaard, I.; Attwood-Charles, W.; Cansoy, M.; Carfagna, L.B.; Schor, J.B.; Wengronowitz, R. Domesticating the market: Moral exchange and the sharing economy. Socio-Econ. Rev. 2020, 18, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, T.; Baglioni, S. Defining the gig economy: Platform capitalism and the reinvention of precarious work. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2021, 41, 1012–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrejevic, M. Automating surveillance. Surveill. Soc. 2019, 17, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, N. The rating game: The discipline of Uber’s user-generated ratings. Surveill. Soc. 2019, 17, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, R. Uber and the making of an algopticon—Insights from the daily life of Montreal drivers. Cap. Cl. 2020, 44, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabo, B.; Karanovic, J.; Dukova, K. In search of an adequate European policy response to the platform economy. Transf. Eur. Rev. Labour Res. 2017, 23, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, J. The resurgence of gig work: Historical and theoretical perspectives. Econ. Labour Relat. Rev. 2017, 28, 382–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S. Raw Deal: How the “Uber Economy” and Runaway Capitalism Are Screwing American Workers; St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ravenelle, A.J. Precariedad y Pérdida de Derechos. Historias de la Economia Gig; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Slee, T. Lo Tuyo es mío: Contra la Economía Colaborativa; Taurus: Barcelona, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, K.J.; Attoh, K.; Cullen, D. “Just-in-Place” labor: Driver organizing in the Uber workplace. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2021, 53, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Martínez, G.; Haz-Gómez, F.E.; Manzanera-Román, S. Identities and Precariousness in the Collaborative Economy, Neither Wage-Earner, nor Self-Employed: Emergence and Consolidation of the Homo Rider, a Case Study. Societies 2022, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, J.; Kincaid, R. Gig Work and the Pandemic: Looking for Good Pay from Bad Jobs during the COVID-19 Crisis. Work. Occup. 2022, 50, 60–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubal, V. Wage slave or entrepreneur? Contesting the dualism of legal worker identities. Calif. Law Rev. 2017, 105, 65–123. [Google Scholar]

- Goods, C.; Veen, A.; Barratt, T. “Is your gig any good?” Analysing job quality in the Australian platform- based food-delivery sector. J. Ind. Relat. 2019, 61, 502–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ophir, Y.; Sisso, I.; Asterhan, C.S.; Tikochinski, R.; Reichart, R. The turker blues: Hidden factors behind increased depression rates among Amazon’s mechanical turkers. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 8, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavin, P.; Schieman, S. Dependency and Hardship in the Gig Economy: The Mental Health Consequences of Platform Work. Socius 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, C. Gender and precarity in platform work: Old inequalities in the new world of work. New Technol. Work Employ. 2022, 37, 206–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Zaidi, M.; Ramachandran, R. Locating women workers in the platform economy in India–old wine in a new bottle? Gend. Dev. 2022, 30, 765–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez Crocco, F.; Atzeni, M. The effects of the pandemic on gig economy couriers in Argentina and Chile: Precarity, algorithmic control and mobilization. Int. Labour Rev. 2022, 161, 441–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.A.; Graham, M. Hidden transcripts of the gig economy: Labour agency and the new art of resistance among African gig workers. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2020, 52, 1269–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, H.D. “Gig” unionism or collective action in the platform economy. Cuad. Relac. Labor. 2022, 40, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, K.; Abal, P. Precarization of platforms. Case Cour. Spain. Psicoperspectivas 2020, 19, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Tassinari, A.; Maccarrone, V. Riders on the storm: Workplace solidarity among gig economy couriers in Italy and the UK. Work Employ. Soc. 2020, 34, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandaele, K. Collective resistance and organizational creativity amongst Europes platform workers: A new power in the labour movement? In Work and Labour Relations in Global Platform Capitalism; Haidar, J., Keune, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; pp. 206–235. [Google Scholar]

- Mcloughlin, M.; Los “riders” contratados se organizan contra Glovo y montan su primer comité de empresa. Confidencial 2022. Available online: https://www.elconfidencial.com/tecnologia/2022-05-11/glovo-comite-de-empresa-riders-barcelona_3423229/ (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Heiland, H. Controlling space, controlling labour? Contested space in food delivery gig work. New Technol. Work Employ. 2021, 36, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolber, B. From Independent Contractors to an Independent Union: Building Solidarity through Rideshare Drivers United’s Digital Organizing Strategy; Media Inequality Change: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- De Andrés, E.A.; Zapata Campos, M.J.; Zapata, P. Stop the evictions! The diffusion of networked social movements and the emergence of a hybrid space: The case of the Spanish Mortgage Victims Group. Habitat Int. 2015, 46, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, T. Platform cooperativism vs. the sharing economy. Big Data Civ. Engagem. 2014, 47, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, T. Uberworked and Underpaid: How Workers Are Disrupting the Digital Economy; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Carrión, J.R. Deconstruyendo la ”peer-to-peer sharing economy”: El desafío de la ”economía colaborativa” a las cooperativas de plataforma en la era del pos-trabajo del siglo XXI. CIRIEC-España Rev. Economía Pública Soc. Coop. 2022, 105, 177–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster Morell, M.; Espelt, R.; Renau Cano, M. Sustainable platform economy: Connections with the sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohmann. 2021. Available online: https://repo.funde.org/id/eprint/1839/ (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Kokkinidis, G. Spaces of possibilities: Workers’ self-management in Greece. Organization 2015, 22, 847–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumbers, A.; Shaw, D.; Crossan, J.; McMaster, R. The work of community gardens: Reclaiming place for community in the city. Work Employ. Soc. 2018, 32, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster Morell, M.; Espelt, R. A framework for assessing democratic qualities in collaborative economy platforms: Analysis of 10 cases in Barcelona. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott-Cato, M.; Hillier, J. How could we study climate-related social innovation? Applying Deleuzean philosophy to Transition Towns. Environ. Politics 2010, 19, 869–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M.; Spicer, A. Critical leadership studies: The case for critical performativity. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 367–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, M. From passionate labour to compassionate work: Cultural co-ops, do what you love and social change. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 2018, 21, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzeni, M.; Vieta, M. Between class and the market: Self-management in theory and in the practice of worker-recuperated enterprises in Argentina. In The Routledge Companion to Alternative Organization; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli, P. Social and solidarity economy in a neoliberal context: Transformative or palliative? The case of an Argentinean worker cooperative. J. Entrep. Organ. Divers. 2016, 5, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Domenico, M.; Haugh, H.; Tracey, P. Social bricolage: Theorizing social value creation in social enterprises. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 681–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear, R.; Teasdale, S.; Lyon, F.; Hazenberg, R.; Bull, M.; Aiken, M.; Kopec-Massey, A. Social Enterprise in the United Kingdom: Models and Trajectories; Working Paper No 40; ICSEM: Northampton, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M.S. Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, P.; Kibler, E. Institutional complexity and social entrepreneurship: A fuzzy-set approach. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1314–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufays, F.; Huybrechts, B. Connecting the dots for social value: A review on social networks and social entrepreneurship. J. Soc. Entrep. 2014, 5, 214–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, I.A.; Haugh, H.; Chambers, L. Barriers to social enterprise growth. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 1616–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, V.; Raffaelli, P. The interconnected influences of institutional and social embeddedness on processes of social innovation: A Polanyian perspective. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2022, 34, 319–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkler, Y. Peer production, the commons, and the future of the firm. Strateg. Organ. 2017, 15, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Marti, I. Entrepreneurship in and around institutional voids: A case study from Bangladesh. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, A.; Battilana, J.; Mair, J. The governance of social enterprises: Mission drift and accountability challenges in hybrid organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 2014, 34, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M. The EMES approach of social enterprise in a comparative perspective. In Social Enterprise and the Third Sector; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 58–81. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Graham, J.K.; Cameron, J.; Healy, S. Take Back the Economy: An Ethical Guide for Transforming Our Communities; U of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, L. The Mass Strike; Bookmarks Publications: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval, M. Fighting Precarity with co-oPeration? worker co-oPeratives in the cultural sector. New Form. 2016, 88, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasparian, D. Co-Operative Struggles: Conflicts in Argentina’s New Worker Co-Operatives; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, A.; Charmaz, K. (Eds.) The SAGE Handbook of Current Developments in Grounded Theory; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miró, I. Ciutats Cooperatives. Esbossos d’una Altra Economia Urbana; Icaria Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Barcelona City Council. Estratègia de l’Economia Social i Solidària a Barcelona. Reactivació i Enfortiment d’una Economía per a la Vida a la Ciutat. 2021. Available online: https://essbcn2030.decidim.barcelona/processes/essbcn2030/f/1594/ (accessed on 29 December 2022).

- Mena, M.; Las Plataformas de Delivery Preferidas en España. Statista. 29 November 2021. Available online: https://es.statista.com/grafico/23022/proveedores-online-de-servicios-de-restauracion-o-comida-a-domicilio-usados-en-espana/ (accessed on 29 December 2022).

- Grohmann, R. Rider platforms? building worker-owned experiences in Spain, France, and Brazil. South Atl. Q. 2021, 120, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, J. The limits of algorithmic management: On platforms, data, and workers’ struggle. South Atl. Q. 2021, 120, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer-Witheford, N. Cyber-Proletariat: Global Labour in the Digital Vortex; Pluto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schiller, N.G.; Çağlar, A. Locality and Globality: Building a Comparative Analytical Framework in Migration and Urban Studies. In Locating Migration; Cornell University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 60–82. [Google Scholar]

- Greiner, C. Patterns of translocality: Migration, livelihoods and identities in Northwest Namibia. Sociologus 2010, 60, 606–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzold, B. Migration, informal labour and (trans) local productions of urban space—The case of Dhaka’s street food vendors. Popul. Space Place 2016, 22, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]