Abstract

Objective: The purpose of the study was to conduct a systematic review assessing the impact of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs). The study design follows a systematic review and meta-analysis. The data sources are CINAHL, MEDLINE, SportDiscus, ERIC, and Embase from inception until July 2025. Eligibility criteria for selecting the studies include the experimental, quasi-experimental, and pre-experimental literature that investigated interventions designed to support the symptoms of REDs. Results: A total of nineteen studies (fifteen non-pharmacological interventions, four pharmacological interventions), with a total of 759 females, were included in the review. Non-pharmacological interventions demonstrated positive benefits on menstrual function recovery, energy availability, fat mass, and body fat percentage. Meta-analyses quantified nutrition intervention benefits on an individual’s fat mass (kg), 1.36 (95% CI 0.68, 2.04), and body percentage fat (%), 2.21 (95% CI 1.34, 3.08). It was also possible to identify the impact of non-pharmacological interventions on total triiodothyronine (T3) biomarkers (nmol/L), −2.37 (95% CI −5.57, 0.83). It should be noted, however, that non-pharmacological interventions were limited by quality and certainty assessment, identifying included evidence as low to moderate. Pharmacological interventions demonstrated some positive (at times very strong effect sizes) results for impact on bone mineral density, but conclusions are currently limited by well-powered experimental studies. Conclusions: The current evidence base favors non-pharmacological management as an initial response for managing REDs. Initial pharmacological management appears to identify limited but potentially (depending on the drug) promising evidence for the impact on bone mineral density; further evidence is required to be more certain about the impact on hormonal profiling and menstrual recovery function. Further research is needed to help develop a greater understanding.

1. Introduction

Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs) is a relatively new and evolving clinical model that is defined as “A syndrome of impaired physiological and/or psychological functioning experienced by female and male athletes that is caused by exposure to problematic (prolonged and/or severe) low energy availability (LEA). The detrimental outcomes include, but are not limited to, decreases in energy metabolism, reproductive function, musculoskeletal health, immunity, glycogen synthesis and cardiovascular and haematological health, which can all individually and synergistically lead to impaired well-being, increased injury risk and decreased sports performance” [1]. LEA results when the energy intake of an athlete is insufficient to meet the demands of both exercise and normal physiological function [2]. The term REDs stems from the earlier term “Female Athlete Triad”, initially defined in 1993 [3] as the interrelationship between disordered eating, amenorrhea, and osteoporosis. REDs recognises a broader range of health and performance consequences in both female and male athletes. This syndrome is associated with a wide array of clinical outcomes, including menstrual dysfunction, impaired bone health, compromised immune function, gastrointestinal disturbances, fatigue, reduced cardiovascular and metabolic function, and poor mental health [4,5]. Contributing factors to REDs are multifactorial and may include excessive training, inadequate nutrition, mental health challenges, disordered eating or eating disorders, poor sleep, illness, or undiagnosed medical conditions [2]. REDs is highly prevalent in elite sport settings; for instance, studies report signs of LEA in both male volleyball players and professional female football players, with many athletes at risk of developing the full spectrum of REDs [6,7]. Around 70% of elite athletes have a medium to high risk of REDs [8], but some studies have also shown a higher prevalence of symptoms. For instance, an Australian study found that 80% of elite and pre-elite athletes exhibited at least one REDs-related symptom, and 37% presented with two or more [9]. Prevalence is not only applicable in a sports setting but also in a clinical setting as Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea (FHA), which accounts for 20–35% of secondary amenorrhea cases [10].

The widespread prevalence and serious health implications of REDs underscore the importance of effective management strategies, both pharmacological and non-pharmacological, which have been identified in athletic populations [2] as such strategies help mitigate the impact of REDs on athletes [1]. Currently, non-pharmacological treatment forms the cornerstone of REDs management, with an emphasis on addressing the underlying issue of LEA. These strategies primarily involve educational initiatives aimed at increasing awareness and understanding of REDs among athletes, coaches, and healthcare professionals (a primary intervention strategy [11]). In addition, tertiary prevention strategies centered around individualized nutritional interventions are critical and show promising effects [11], focusing on increasing overall energy intake to restore energy balance and support physiological recovery [12]. Modifications to training load, by reducing volume or intensity, are also commonly implemented to decrease Energy Expenditure (EE) and allow for physiological restoration [13]. These non-pharmacological approaches are often effective in reversing early symptoms of REDs and remain the first-line treatment, particularly in the absence of severe clinical manifestations. Where non-pharmacological modalities of treatment are ineffective (notably in particular groups like females with resistant amenorrhea or with low bone mineral density (BMD)), not appropriate, or when physiological effects mean immediate intervention is required, pharmacological strategies can be considered [14]. Supportive treatments, such as calcium, vitamin D, and iron supplementation, are often implemented as part of a broader therapeutic strategy [11,15], although more specific strategies have been tested and utilised. For instance, transdermal 17β-oestradiol with cyclic progesterone has been shown to be more effective than combined oral contraceptives (COCs) in improving BMD in oligo-amenorrhoeic athletes [16]. Further to this, hormone replacement or bone-active agents may target complications, such as low bone density, when conservative measures fail [16,17]. However, these treatments can be considered controversial due to long-term safety concerns [18], and further research is required to clarify their role in REDs management.

Recent reviews, including those by Tenforde et al. [19] and Melin et al. [15], provide important insights into the pathophysiology and management of REDs. However, neither uses a systematic search process, with only one [19] undertaking a search of a database in 2014. Both reviews rely on a largely narrative summary of the results, not including quality assessment of research or certainty assessment. From these reviews, there is an evident lack of high-quality comparative evidence on treatment efficacy. The International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) narrative review on primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention strategies underscores the importance of addressing LEA as the root cause, recommending tailored nutritional rehabilitation, training adjustments, and multidisciplinary care [11]. Past review evidence and position statements consistently call for more evidence-based guidelines and emphasize that most pharmacological options address secondary outcomes (e.g., menstrual restoration or bone health) rather than the underlying LEA. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no systematic review or meta-analysis has directly compared the efficacy, risks, and outcomes of pharmacological versus non-pharmacological treatments for REDs. This gap is critical given the rising prevalence of REDs and the growing diversity of affected athletic populations. Thus, the present systematic review and meta-analysis aims to fill this gap by rigorously evaluating available interventions for REDs.

2. Methods

A systematic review was undertaken and reported according to the PRISMA checklist [20]. A protocol was developed and published on 17 June 2025 on PROSPERO (reference: CRD420251073240).

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if they met the following conditions as set out by the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Study design (PICOS) acronym.

2.2. Participants

To be included, studies need to include female athletes classified as elite, recreational, pre-elite, club, active, or other levels. All athletes had to have characteristics identified within the remit of REDs [1]. Studies were included if they identified participants with oligo-amenorrhea, LEA, FHA, and/or exercise-related menstrual dysfunction (ExMD). Studies were excluded if participants were male, as limited research has been conducted on REDs in the male population. Studies were also excluded if participants had a clinical diagnosis of a psychological disorder or mental illness, were currently using hormonal contraceptives, or had Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) or endometriosis. Studies using the same group of participants without evaluating different outcome measures were excluded to avoid duplication of results.

2.3. Intervention

Interventions were grouped as pharmacological or non-pharmacological interventions. Pharmacological interventions were included if they utilised Oestrogen therapy, Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT), or calcium supplementation. Non-pharmacological interventions were included if they were based on diet alteration or dietary supplements, exercise, education, or consultation. Interventions were excluded if they did not directly target REDs, if their outcome measures were not relevant to REDs-related outcomes (see outcome eligibility criteria below), or if they focused exclusively on psychological measures (such as disordered eating, eating disorders, body image) without addressing the broader spectrum of REDs symptoms. This was identified to limit the clinical heterogeneity between different mental health diagnoses. It should be noted that any presence of a pharmacological intervention, e.g., (combined hormone therapy), when identified alongside a non-pharmacological intervention (e.g., vitamin D supplementation), was classified as pharmacological for the purpose of this review.

2.4. Outcomes

Studies were included if they utilised outcomes that included measures related to menstrual resumption, energy or dietary improvement related outcome measures, and physiological measures related to REDs, for instance, weight, fat mass, body percentage weight, cortisol, identification of hormones, and BMD. Alternative studies could be included if they identified physical or functional measures change (e.g., strength improvements) or psychological measures (e.g., mood, body image scale).

2.5. Study Design

Studies were included if they reported on the experience of, or outcomes from, an intervention-based study. Experimental, quasi-experimental, and pre-experimental designs were included. Conference proceedings, theses, and ongoing research were included to reduce the risk of publication bias. Studies were excluded if they did not report on the experience of, or outcomes from, an intervention-based study. Non-experimental designs, such as cross-sectional research pieces, were excluded. Reviews, editorials, opinion pieces, and commentaries were also excluded. Studies that were unpublished without accessible data, duplicate publications, and conference abstracts without full data were excluded unless further data were available.

2.6. Other Criteria

Date restrictions were not applied to the search dates. No restriction on language was made. No publications written in languages other than English were used. Where any translation could not be comprehended, the study was excluded.

2.7. Information Sources and Search Strategy

A blind search by two authors (A.W., A.S.), supported by the management software Covidence 2025 ©, was undertaken from a total of five electronic databases. They included CINAHL, MEDLINE, SportDiscus, ERIC, and Embase from inception until July 2025. Search strategies combined controlled vocabulary (e.g., MeSH terms) and free-text keywords relating to the population, including women or females. These conditions include Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs), female athlete triad, low energy deficiency, amenorrhea, oligomenorrhea, and menstrual disturbance. The intervention includes terms like intervention, treatment, therapy, female, or women. The search was adapted for each database, with Boolean operators, truncations, and limits applied as appropriate. Full search strings for each database are provided in Supplementary Files. In addition to this, three electronic search engines, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, and Findit.Bham, were searched for the first 30 pages of results using the terms “females and relative energy deficiency and sport”. The gray literature was searched using the Grey Matters search engine. Citation chasing was undertaken with all included articles and all identified previous reviews.

2.8. Selection Process

Two blind authors (A.W., A.S.) undertook the selection process using Covidence 2025 © software. A separate academic with experience in systematic reviews was available to arbitrate discussions when a decision could not be made (two studies were identified for this process, which were included following arbitration). Both authors made decisions by title, then by abstract, and then by reading the full text independently.

2.9. Data Items

A pre-determined extraction data tool devised in Microsoft Excel identified specific variables that included demographic variables (study title, journal, design, type of intervention, geographical location, population, age, sport, athlete level, participant identifying group, if a clinical diagnosis was obtained, and method of assessment). The extraction tool was pilot tested on three studies and refined before full extraction occurred. Intervention variables were identified according to the TEDieR guidelines [21], tabulated, and outcome measures (identification of all outcomes and identification of primary and secondary outcome measures) were considered, which were then grouped by domains.

2.10. Risk of Bias Assessment

A risk of bias assessment was undertaken using the ROB-2 tool [22] for randomised control trials or the Robins-I Version 2 tool [23] for non-randomised control trials. For other types of design or instance case control or case series, the JBI critical appraisal tools were utilised (https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools, accessed on 25 June 2025). See the Supplementary Files for the assessment.

2.11. Effect Measures

Mean differences were considered where possible for all outcome measures. Fixed effects models were used for the meta-analysis. Statistical heterogeneity was quantified using I2. Thresholds of 25%, 50%, and 75% represented low, moderate, and high heterogeneity [24]. However, we did not use these as absolute cut-offs and did consider clinical and methodological diversity of studies [25]. When the standard deviation of change scores could not be identified, a formula for estimating it was used as follows:

No multi-arm studies were used in the meta-analysis conducted. All meta-analyses were conducted using RevMan version 5.4.

2.12. Synthesis

A narrative synthesis documented the results by outcome domain. The following outcome domain areas were identified (a) physiological (including menses and menses restoration, weight, cortisol, identification of hormones, BMD), (b) physical and functional (including measures of strengths or function), and (c) psychological outcomes (including mood, body image scale, or eating disorder questionnaire). A meta-analysis was possible and conducted for three outcome measures as part of the synthesis for non-pharmacological interventions. Requirements for the meta-analysis included having at least 3 studies that used consistent measurement methods, outcome measures that were comparable, and intervention durations that were consistent, ensuring that clinical characteristics of the included studies were homogenous. A primary focus was on physiological outcome measures, which were most consistently reported. Clinical heterogeneity, heterogeneity in measurement tools, and insufficient data meant that no other meta-analysis was possible due to the limited evidence currently available.

2.13. Certainty Assessment

GRADE [26] was used to assess the certainty of the outcome measure results and supplement narrative synthesis and meta-analysis.

2.14. Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Statement

Authors used a narrative synthesis to identify common demographics and intervention characteristics. The group selected within the eligibility criteria and represented across studies are reasonably homogenous due to the individuals representing studies mainly from the USA and from university-based settings that represent female endurance and distance sports/athletes. The focus of this work was only on females and is not extended to males.

2.15. Patient and Public Involvement

No patient or public involvement in this review was undertaken.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

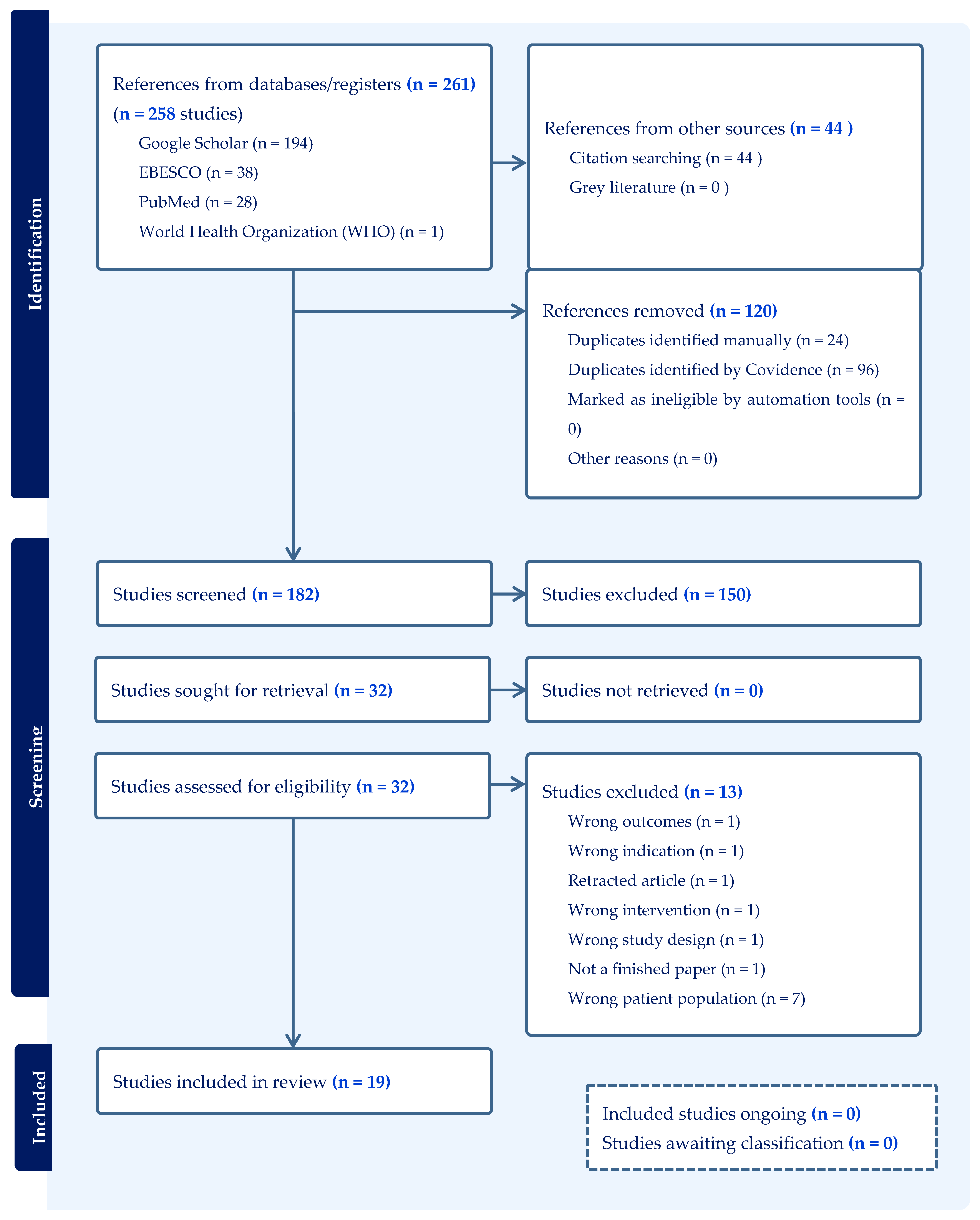

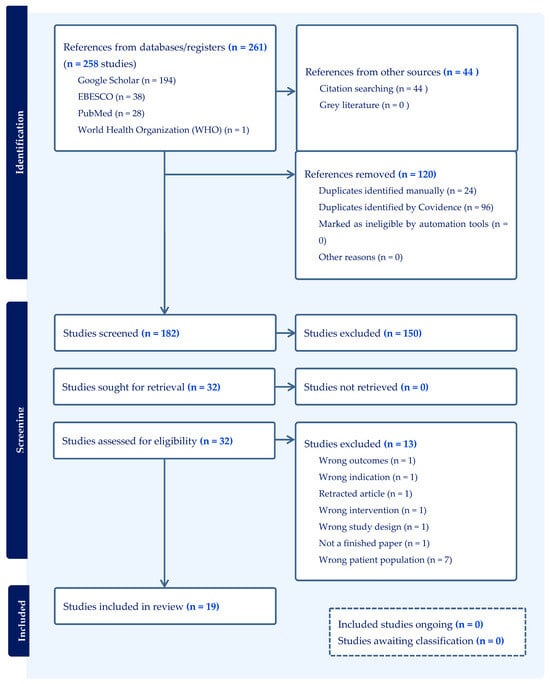

A total of 3156 articles were examined by both reviewers. A total of 261 were input into the Covidence database, of which 162 were identified for screening, and 19 studies met the inclusion criteria for this systematic review. This comprised fifteen [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] (15/19, 79%) non-pharmacological interventions and four [16,42,43,44] (4/19, 21%) pharmacological interventions. See Figure 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram (see Supplementary File S1 for additional information).

Figure 1.

A PRISMA 2020 flow diagram produced by Covidence to identify the blind search process undertaken by two authors.

3.2. Study Characteristics

A total of 759 female participants were included (n = 759). This included individuals most often in the age bracket of 18–35 years. Where possible (n = 12 studies, n = 473 participants), an aggregated mean age was calculated as 20.9 years. The most included group of females was female ‘athletes” (n = 12/19, 63%), followed by “exercising” or “active” females (n = 5/19, 26%). Non-pharmacological trials included nine (9/15, 60%) as athletes, five as “exercising” or “active” females (5/15, 33.33%), and one (1/15, 7%) identified without classification. Pharmacological trials included athletes (3/4, 75%), and one study included ballet dancers (1/4, 25%). The classification of included sports most often related to a multi-sport, 7/19 (37%; 6/15, 40% for non-pharmacological and 1/4, 25% pharmacological) or a multi-sport with the term endurance or distance, 10/19 (53%; 8/15, 53% for non-pharmacological and 2/4, 50% for pharmacological). The most common specific sport mentioned was running, followed by cycling. Although, exact numbers for these specific sports would be hard to determine due to the use and inclusion of multi-sports. The most common country location for studies was the USA (n = 12/19, 60%), including 10/15 (67%) for non-pharmacological interventions and 2/4 (50%) for pharmacological; this was followed by Germany (n = 3/19, 16%), all coming from non-pharmacological interventions. See Table 1 for a summary of non-pharmacological interventions and Table 2 for a summary of pharmacological interventions.

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of non-pharmacological interventions.

Table 2.

Summary characteristics of pharmacological interventions.

3.3. Intervention Characteristics

The most common characteristics across studies was as follows. The classification system used to identify athletes most often identified amenorrhea (n = 6/19) as a clinical inclusion criterion for participation. Common intervention components included (a) increasing energy intake/diet supplementation (n = 10/19; 53%; 10/15, 67% for non-pharmacological interventions) and (b) dietary/nutritional counseling or advice (out of all studies, n = 6/19, 32%), and 6/15 (40%) for non-pharmacological interventions was the most prevalent intervention component. The average duration of intervention for non-pharmacological interventions was 28.3 ± 15.8 weeks (n = 12/15, 80%). The setting selected for the intervention was most often described as a “university” setting (n = 8/19, 42%), which included 8/15 (53%) for non-pharmacological studies. Staff involved in the interventions were most often identified as dietitians (n = 12/19), 12/15 (80%) for non-pharmacological studies and 1/4 (25%) for pharmacological interventions, or as researchers (n = 9/19, 47%), including 8/15 (53%) for non-pharmacological interventions and 1/4 (25%) for pharmacological evidence. See Table 3 for a TIDieR summary of the non-pharmacological studies and Table 4 for a TIDieR summary table for the intervention studies.

Table 3.

A summary table for non-pharmacological studies (using TIDieR sub-headings).

Table 4.

Tider summary table for intervention studies.

3.4. Critical Appraisal

The following risk of bias tools were used depending on study design: ROB 2 (for Randomised control trials) (RCTs, n = 7/19, 37%), ROBINS-I V2 (for non-randomised interventional studies, n = 11, 58%), and the JBI checklist (for case reports, n = 1, 5%).

Overall, RCTs demonstrated low (n = 3/7, 43%) to moderate (n = 4/7, 57%) risk of bias, with most (n = 5/7, 71%) studies showing low risk across all key domains. However, two RCTs [40,42] had “some concerns”, particularly in randomisation and outcome reporting. In contrast, all non-randomised studies were rated as having serious risk due to the influence of confounding variables (e.g., baseline differences of energy availability, variation in training load, duration of menstrual dysfunction, age). Additional concerns were noted in non-RCTs in domains, such as intervention classification (serious risk (n = 1/11, 9%), moderate risk (n = 10/11, 91%)), outcome measurement (n = 10/11, 91%), and missing data (n = 6/11, 55%), typically rated at moderate risk. The single case report by Mallinson et al. [38] was methodologically sound across most JBI criteria but lacked reporting on adverse or unanticipated events. Supplementary File S2 provides further information regarding critical appraisal.

3.5. Synthesis and Certainty Assessment

Findings are provided below for non-pharmacological evidence and pharmacological evidence. Supplementary File S3 is available that provides the assessment of critical appraisal (quality) and certainty assessment.

3.6. Non-Pharmacological

Among the studies assessing non-pharmacological interventions, the most frequently reported outcomes were menstrual function recovery (n = 8/15, 53%), improvements in energy availability (EA) (n = 5/15, 33%), changes in body composition (n = 7/15, 47%), and alterations in relevant biomarkers (n = 9/15, 60%). These are reported below.

3.7. Menstrual Function Recovery

Menstrual function recovery was utilized as an outcome measure in eight (n = 8/15, 53%) of the included papers. Seven (n = 7/8, 88%) reported statistically significant improvements (p-values ranging from <0.01 to 0.05), with large, estimated effect sizes (0.8–1.2). One case report lacked statistical analysis but described clinically meaningful recovery in both participants. All nine studies were judged to show clinically meaningful outcomes, primarily associated with increased EA through nutritional (n = 5/8, 63%) or non-pharmacological interventions (n = 1/8, 13%) or both nutritional and non-pharmacological interventions (n = 2/8, 25%). Six (6/8, 75%) studies reported the number of intervention participants who experienced improved or recovery of menses. Of the 142 intervention group participants, 47 (47/142, 33%) had partial or full recovery of menses.

3.8. Confidence in Evidence

Summary of evidence contributing to certainty rating: GRADE study ratings included one very low, five low, and two high.

The overall confidence rating was low, although findings can be taken with reasonable confidence due to the consistency of evidence.

3.9. Energy Availability

Changes in EA were evaluated in five studies (n = 5/15, 33%). All five reported statistically significant improvements (p-values ranging from <0.01 to 0.05), with estimated effect sizes between 0.5 and 1.0. Each study demonstrated clinically meaningful improvements, achieved through increased caloric intake (n = 5/15, 33%).

3.10. Confidence in Evidence

Summary of evidence contributing to certainty rating: GRADE study ratings included five low.

The overall confidence rating was low, although the findings can be taken with reasonable confidence due to the consistency of evidence.

3.11. Body Composition Measures

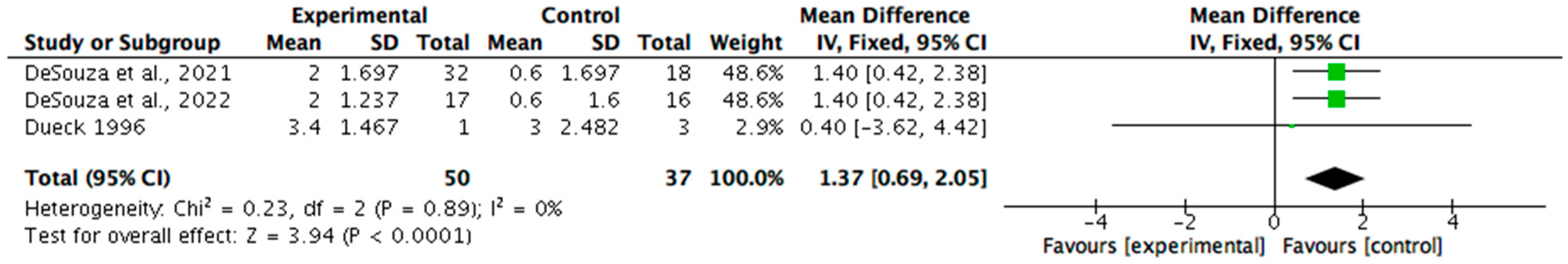

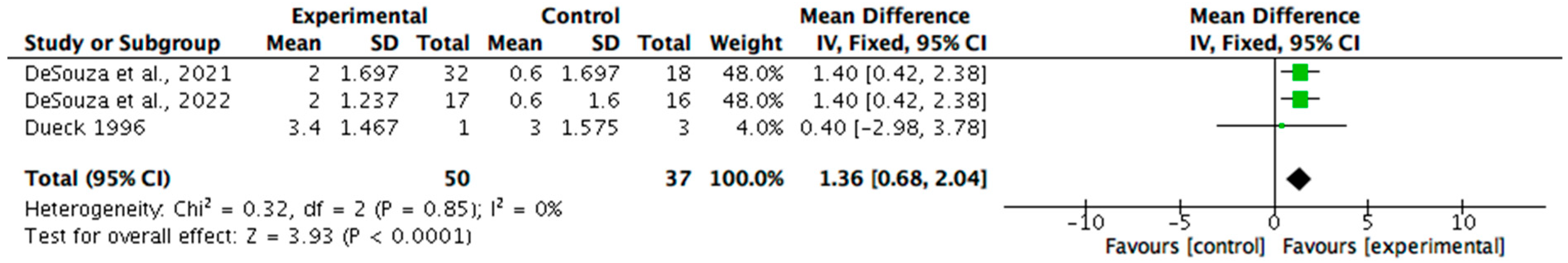

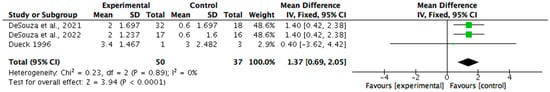

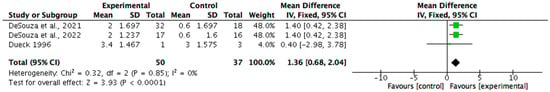

Body composition was measured in seven (n = 7/15, 47%) of the non-pharmacological papers. Six (n = 6/7, 86%) reported statistically significant improvements in at least one parameter, such as body weight, fat mass, or body fat percentage, with p-values ranging from <0.001 to 0.05 and effect sizes between 0.5 and 2.5. One study did not report statistical significance but showed large, estimated effects. All seven studies were considered clinically meaningful, with improvements primarily associated with increased energy intake. Meta-analysis was undertaken for the measures of changes in fat mass and percentage of body fat (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). The change in body mass (kg) was identified as 1.36 (95% CI 0.68, 2.04). Statistical heterogeneity was identified as low (I2 = 0%). The change in body fat percentage (%) was identified as 2.21 (95% CI 1.34, 3.08). Statistical heterogeneity was identified as moderate (I2 = 32%).

Figure 2.

A meta-analysis showing the benefit of nutrition-based interventions on fat mass [29,30,31].

Figure 3.

A forest plot showing the benefit of nutrition-based interventions on percentage body fat [29,30,31].

3.12. Confidence in Evidence

Summary of evidence contributing to certainty rating: GRADE study ratings included five low and two very high.

The overall confidence rating: moderate, although findings can be taken with reasonable confidence as the evidence is supported by a meta-analysis.

3.13. Hormonal and Blood Biomarkers

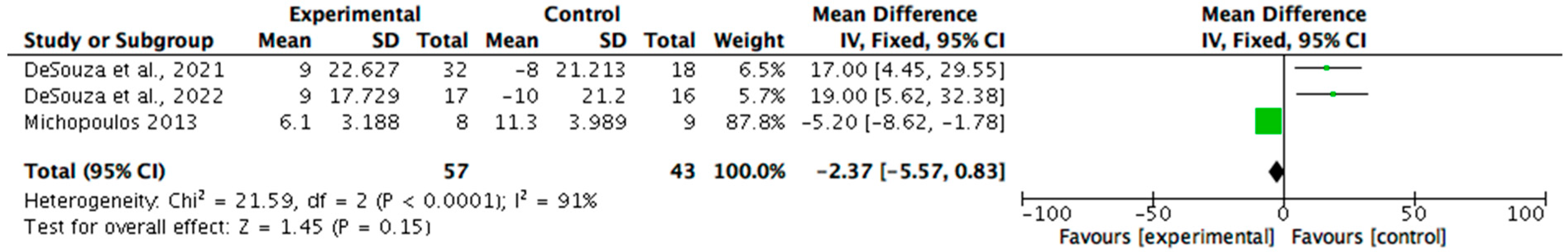

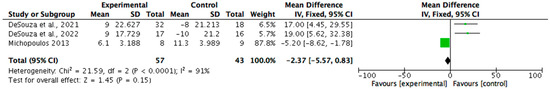

Biomarkers related to REDs were analysed in nine (n = 9/15, 60%) studies. Eight (n = 8/9, 89%) reported statistically significant improvements (p < 0.05), with effect sizes ranging from 0.5 to 0.8. The most assessed markers included serum leptin, triiodothyronine (T3), cortisol, oestradiol, and luteinizing hormone (LH) pulsatility. One study, while lacking statistical testing, demonstrated substantial changes in multiple biomarkers and was considered clinically meaningful. All nine studies reported clinically meaningful outcomes, supporting the utility of biomarker monitoring in evaluating recovery in REDs and the effectiveness of dietary and non-pharmacological interventions. A meta-analysis (see Figure 4) was possible regarding the reporting of T3 by three studies. The results identified a mean change of −2.37 (95% CI −5.57, 0.83) on T3 biomarkers (nmol/L). Statistical heterogeneity was identified as high (I2 = 91%).

Figure 4.

A forest plot showing the T3 biomarker changes from non-pharmacological interventions [29,30,40].

3.14. Confidence in Evidence

Summary of evidence contributing to certainty rating: GRADE study ratings included six low, three very high, and eight with a moderate effect.

The overall confidence rating was low; evidence was affected by quality downgrades, and a meta-analysis favored the control group. Further evidence is required.

3.15. Pharmacological

Studies examining pharmacological treatments commonly assessed BMD (n = 4/4, 100%), hormonal profiles (e.g., oestrogen, L, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)) (n = 3/4, 75%), recovery of menstrual function (n = 3/4, 75%), and bone turnover markers (n = 1/4, 25%) as indicators of skeletal health and remodeling.

3.16. Bone Mineral Density Markers

BMD was assessed in four (n = 4/4, 100%) pharmacological studies.

Ackerman et al. [16] identified only the protective effect on BMD of one intervention group named PATCH (physiological oestrogen replacement via 100 mcg transdermal 17β-E2 and 200 mg cyclic micronized progesterone) versus no intervention. They identified protective effects as risk ratios of 11.22 (95% CI; 2.12–59.29; p = 0.008) for the spine, 10.76 (95% CI; 2.07–55.98; p = 0.001) for the femoral neck, and 1.44 (95% CI; 0.19–10.76; p = 0.292) for the total hip. The results were controlled for age, height, race, ethnicity, and weight change. The PILL (combined oral contraceptives of 30 µg ethinyl estradiol with 0.15 mg desogestrel) identified no differences.

Dadgostar et al. [42] utilized a low dose oral contraceptive (30 µg ethinyl estradiol and 150 µg levonorgestrel) and identified no statistically significant changes in a small sample (n = 8 for the intervention group and n = 5 for control group that received calcium and vitamin d) but identified a slight increase (0.3% increase) in BMD values at the lumbar spine at 9 months in those receiving and a minor decrease (1.6%) in the control group over the same time period. The effect size when comparing the change scores was d = 0.23 for the spine (small effect) compared to the control and d = 0.11 for the femur (limited or no effect) compared to the control.

Gibson et al. [43] utilized three groups, the intervention group with 1 mg estriol and 2 mg estradiol for 12 days and then 1 mg estriol, and 1 mg of estradiol for 6 days, and 1000 mg calcium carbonate (n = 10) versus the calcium carbonate (1000 mg; n = 14) group versus the control group with no treatment (n = 10). The intervention group was identified as having positive changes in the following locations expressed by percentage change: the trochanteric region (1.71%, SD = 2.86), the lumbar spine L2-L4 (5.67%) (SD = 9.47), and Ward’s triangle (3.55%) (SD = 4.05). This resulted in effect sizes compared to the control group of d = 0.73 for the trochanteric region, d = 0.80 for the lumbar spine, and d = 0.94 for Ward’s triangle. The neck of the femur showed a decrease of −0.63% (SD = 2.21), although this still created a small positive effect size of d = 0.18 against the control group.

The calcium group identified positive changes but high standard deviations in the neck of the femur (1.33%) (SD = 6.29) and Ward’s triangle (1.33%) (SD = 9.00). The effect size compared to the control group was a small effect size of d = 0.26 at the neck of the femur and d = 0.29 at Ward’s triangle. The other sites, including the trochanteric region (−0.33%, SD = 5.21) and the lumbar region (−0.03, SD = 5.01), demonstrated a small negative change.

Warren et al. [44] compared the intervention group (n = 13) with Premarin (0.625 mg; 25 days) and then with Provera (10 mg, 9 days [days 16–25]) versus placebo (n = 11). The intervention group identified some positive percent change in BMD across the 24-month period at the spine (5.60) (SD = 1.10) and wrist (0.91) (SD = 5.12) but not at the foot (−6.49) (SD = 2.04). The placebo group arguably outperformed the intervention group with a positive change across all sites, including the spine (4.46%) (SD = 2.80), the wrist (3.19%) (SD = 1.48), and the foot (1.48%) (SD = 2.83).

3.17. Confidence in Evidence

Summary of evidence contributing to certainty rating: GRADE study ratings included one very low, one low, one high, and one very high.

The overall confidence rating was moderate, and the findings can be taken with reasonable confidence due to the consistency of evidence, but some caution is needed when considering the exact pharmacological intervention used.

3.18. Hormonal Profiling

Hormonal profiles were evaluated in three (n = 3/4, 75%) studies, with two [16,43] (n = 2/4, 50%) showing significant improvements (p < 0.05) in key hormones, such as oestradiol and progesterone, with effect sizes around 0.7–0.8. One study [44] reported normalization of hormonal levels in treatment groups with significance at baseline. Three [16,43,44] (n = 3/4, 75%) studies assessing hormonal outcomes were considered clinically meaningful.

Ackerman et al. [16] identified a significant number of results comparing two intervention groups against the control. See Table 5 for a summary of the effect size identified comparing all groups at 6 months and 12 months.

Table 5.

Identifying effect sizes (Cohen’s d) from Ackerman et al.’s [16] study on biomarkers.

Dadgostar et al. [42] only measured lipid profiles and apolipoprotein levels and did not report hormonal data, and Warren et al. [44] only identified hormonal data at baseline.

3.19. Confidence in Evidence

Summary of evidence contributing to certainty rating: GRADE study ratings included one very low, one low, and one very high.

The overall confidence rating was low. The findings can be taken with caution due to inconsistency of reported outcomes and evidence.

3.20. Menstrual Function Recovery

Menstrual function recovery was reported in three (n = 3/4, 75%) [16,43,44] studies, all demonstrating statistically significant improvements (p-values ranging from p < 0.05 [43] to 0.0001 [16]). These improvements were deemed clinically meaningful, indicating effective restoration of menstrual function with pharmacological treatment.

3.21. Confidence in Evidence

Summary of evidence contributing to certainty rating: GRADE study ratings included one very low, one low, one high, and one with a large effect and a dose response.

The overall confidence rating was moderate, and the findings can be taken with reasonable confidence due to the consistency of evidence.

3.22. Bone Turnover Markers

Bone turnover markers were evaluated in one (n = 1/4, 25%) study [16], which found significant changes in markers, including P1NP and IGF-1 (p = 0.016), with clinically meaningful effects observed. Effect sizes can be observed in Table 6. Changes in P1NP over 12 months were positively associated with changes in estradiol (r = 0.35, p = 0.004) and IGF-1 (r = 0.37, p = 0.003) and inversely with changes in SHBG (r = −0.28, p = 0.019). For changes in BMD over time, changes in estradiol were associated with changes in the femoral, neck, spine, and hip BMD at 12 months (r ≥ 0.27, p ≤ 0.024).

Table 6.

Identifying effect sizes from Ackerman et al.’s [16] study on bone turnover markers.

3.23. Confidence in Evidence

Summary of evidence contributing to certainty rating: GRADE study ratings included one study rated as high certainty.

The overall confidence rating was low. Further evidence is required to repeat the results.

3.24. Comparative Overview of Intervention Effects

Across the included studies, non-pharmacological interventions consistently demonstrated improvements in menstrual recovery, energy availability, and body composition, with meta-analyses confirming modest but significant benefits for fat mass and body fat percentage. However, certainty of evidence was generally rated low to moderate, reflecting methodological limitations and heterogeneity in outcome definitions. Pharmacological interventions yielded some (at times) very positive changes in hormonal and bone-related biomarkers, often with clearer short-term physiological effects, but the small number of trials and sample sizes utilized and concerns about masking underlying energy deficiency limited confidence in their broader applicability. Taken together, these patterns suggest that while both approaches can produce measurable benefits, current evidence included here suggests that non-pharmacological strategies offer more consistent though less certain improvements across multiple domains, whereas pharmacological options provide targeted effects supported by fewer, but sometimes higher-certainty, studies.

4. Discussion

This review provides initial insight and certainty of evidence considering the effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions compared to pharmacological interventions. Non-pharmacological interventions demonstrated consistent improvements across multiple outcome domains, including recovery of menstrual function, EA, body composition, and hormonal biomarkers. Pharmacological interventions, utilising oestrogen therapy and hormone replacement, showed some effectiveness in improving BMD, restoring menstrual function, and enhancing hormonal profiles. However, the certainty of evidence across both intervention types was limited by methodological weakness and the number of contributing studies. The discussion now provides consideration of the main findings by intervention type.

4.1. Non-Pharmacological Interventions

4.1.1. Menstrual Function Recovery

Despite the overall low quality of evidence, all studies consistently demonstrated clinically meaningful improvements in menstrual function following non-pharmacological interventions. These findings align with the broader physiological and clinical literature. Mechanistically, energy deficiency resulting from insufficient fuel availability suppresses the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian (HPO) axis, leading to menstrual dysfunction [45]. Supporting this, research shows that LH pulsatility is disrupted when EA drops below a clinical threshold, highlighting that EA, rather than body fat or exercise alone, is the primary regulator of reproductive function in active women [46]. Clinical evidence further supports this, with several studies showing that dietary or training modifications can restore menses within several months in affected athletes [27,35].

Current studies vary widely in how recovery is defined, often relying on menstrual bleeding alone [27,28,35,36], which does not confirm ovulation or hormonal restoration [34,38]. Menstrual bleeding alone does not guarantee hormonal balance or ovulation, highlighting the need for standardized, hormonally validated definitions in future research. Future research should adopt standardized, hormonally validated definitions of menstrual recovery to improve consistency and clinical relevance. In addition, longer follow-up periods and consistent use of hormonal markers are needed to assess the long-term health impacts of interventions on reproductive, bone, and overall health in female athletes with REDs.

4.1.2. Energy Availability

EA was identified as improving following interventions. These findings are strongly supported by past research demonstrating the central role of EA in hormonal, reproductive, and metabolic regulation. Low EA has been shown to impair LH pulsatility, suppress resting metabolic rate, and reduce estrogen and IGF-1 levels, negatively affecting reproductive and bone health [47,48]. Importantly, even modest increases in EA can reverse these changes, restoring LH pulsatility, resuming menstrual function, and normalizing metabolic function, highlighting EA as a key modifiable factor in both the development and recovery from REDs. Improvements in bone health have also been observed with prolonged energy restoration, though severe cases may require combined nutritional and pharmacological intervention [49].

Accurate measurement of EA remains a major challenge due to the difficulty of precisely assessing dietary intake, exercise, and fat-free mass. Common reliance on self-reported data and indirect proxy markers, such as menstrual dysfunction, resting metabolic rate, and hormonal changes (reduced leptin and T3), introduces variability and error, limiting confidence in the current findings [17,47]. Therefore, future research needs improved, objective methods to accurately quantify EA in free-living athletes, alongside standardized and sensitive biomarkers, to strengthen the evidence base and guide effective REDs management.

4.1.3. Body Composition

Consistent and clinically relevant improvements in body composition were observed across studies.

Past evidence highlights the complexity of using body composition as a primary indicator of recovery in REDs. Although improvements in fat mass and body weight may reflect enhanced EA and nutritional rehabilitation [17], they are not universally required for physiological recovery. Critically, key outcomes such as the return of menses and improvements in BMD, central to REDs recovery, can occur independently of significant changes in body composition [50]. This is particularly relevant in athletes who are constitutionally lean, where minimal or no changes in fat mass may accompany full recovery of hormonal and metabolic function [51]. Moreover, reliance on body composition alone may overlook meaningful clinical progress or delay appropriate intervention if weight change is minimal. As such, the current consensus, including the 2023 IOC statement on REDs [1], emphasizes that body composition should not be used in isolation to define recovery. Instead, it should be interpreted within a broader clinical framework, incorporating menstrual status, hormonal markers, non-pharmacological changes, and performance indicators. This multidimensional approach is essential for accurately monitoring recovery and tailoring individualized treatment strategies in athletes affected by REDs.

4.1.4. Biomarkers

Endocrine markers, particularly serum leptin and triiodothyronine (T3), along with LH and estradiol, showed consistent, clinically meaningful improvements across studies, indicating recovery of metabolic and reproductive function in REDs. The current findings are consistent with the previous literature highlighting the utility of endocrine biomarkers as sensitive indicators of physiological recovery in REDs. Increases in serum leptin, an adipocyte-derived hormone that signals energy sufficiency to the hypothalamus, are closely associated with improvements in reproductive function [52,53]. Similarly, elevations in T3, a well-established marker of metabolic adaptation, reflect the reversal of energy-conserving mechanisms and the restoration of metabolic homeostasis [17]. Additional improvements in cortisol, estradiol, and LH pulsatility further support the reactivation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis [19,47]. Given the low certainty of current evidence, future research must focus on high-quality, standardized studies to validate endocrine biomarkers as reliable indicators of REDs recovery. Markers like leptin, T3, estradiol, and LH pulsatility show promise but are limited by inconsistent measurement, variability, and unclear clinical thresholds [17,47]. To improve utility, studies should standardize biomarker timing, consider menstrual cycle, diurnal variation, and assay methods, and establish validated cut-offs. Longitudinal research linking hormonal changes to clinical outcomes, such as menstrual resumption and bone health, is needed. Importantly, biomarkers should be combined with clinical assessments, symptom tracking, and performance measures for a comprehensive evaluation [16]. Rigorous validation of these markers is essential to enhance REDs diagnosis, monitoring, and management.

4.1.5. Pharmacological Interventions

Bone Mineral Density

BMD outcomes in REDs interventions were inconsistent across studies, with some evidence suggesting that hormonal therapies may support bone health when nutritional recovery alone is inadequate.

These findings align with existing evidence suggesting that while hormonal therapies may offer some benefit to BMD [50], their effectiveness remains inconsistent. For instance, a review by Indirli et al. [54] reported that hormone therapies using estrogen or leptin showed limited impact on bone metabolism in women with FHA. This variability is likely since such treatments do not address the underlying cause of REDs: chronic low EA. Pharmacological interventions may alleviate certain symptoms but risk masking the broader physiological dysfunction if used in isolation [17,53]. As such, current evidence supports their use only as adjuncts in cases where nutritional rehabilitation and restoration of EA, the foundation of REDs treatment, have not been sufficient, or where bone health is severely compromised [55]. Further to this, out of the four studies currently identified, it should be noted that the strongest evidence was linked to one trial [16], with some support from another trial [43]. Understanding the interventions in these two studies would be important if considering pharmacological treatment as an adjunct.

Menstrual Function Recovery

Although pharmacological interventions have shown promise in supporting menstrual recovery in REDs, current evidence, particularly from non-pharmacological studies, suggests that nutritional and non-pharmacological strategies may offer equally, if not more, effective outcomes, albeit from a smaller and methodologically limited evidence base.

Evidence supporting the current findings aligns with established physiological mechanisms, indicating that hormonal therapy in REDs may obscure true recovery. Combined oral contraceptives (COCs) and other exogenous hormone regimens induce withdrawal bleeding through artificial endometrial shedding, without restoring endogenous ovulatory cycles or HPG axis function [56,57]. As such, withdrawal bleeding can be misinterpreted as menstrual recovery, potentially delaying appropriate treatment interventions targeting LEA. This masking effect is well-documented and underscores the need for more accurate markers of reproductive recovery. Objective indicators such as serum progesterone levels, LH pulsatility, or basal body temperature tracking are recommended to assess ovulatory function and HPG axis restoration [58]. Given these considerations, hormonal therapies should be used with caution and only as adjuncts to primary nutritional and non-pharmacological strategies that address the underlying energy deficiency central to REDs.

Hormonal Profiles

Hormonal interventions demonstrated significant and clinically meaningful effects on estrogen and progesterone levels, with estradiol notably higher in treatment groups compared to those receiving oral contraceptives. But, the certainty of evidence is mixed.

Ackerman et al. [16] demonstrated that improvements in BMD can occur without endogenous hormonal normalization, as menstrual function did not resume during treatment with transdermal estrogen. This indicates that symptom recovery, such as bone health improvement, may happen independently of menstrual and hormonal recovery when exogenous hormones are administered. Interpreting endocrine responses in this context is complex because exogenous hormones, like transdermal estradiol or COCs, suppress endogenous hormone production via negative feedback on the HPG axis [16,59]. This suppression can create misleading hormonal profiles that suggest normalization without true recovery of natural reproductive function, such as ovulation and menstrual cycles [59]. Therefore, clinical improvements in outcomes may reflect the direct effects of hormone therapy rather than restoration of endogenous endocrine function [16]. These complexities highlight the need for a comprehensive assessment of REDs recovery that goes beyond hormone levels to include clinical symptoms and functional reproductive status [17].

Bone Turnover Markers

Analysis of bone turnover markers, specifically P1NP and IGF-1, showed statistically and clinically significant changes indicative of meaningful effects on bone metabolism, supported by high-certainty evidence; however, the findings are limited by being based on a single study, highlighting the need for further research to validate their utility in monitoring bone health in athletes with REDs.

These findings are supported by the literature recognizing bone turnover markers, such as P1NP and IGF-1, as sensitive indicators of bone metabolism [60]. However, their clinical utility is challenged by variability in assay methods, biological fluctuations, and influences from nutrition, exercise, and hormonal status [61]. The limited number of studies reporting these markers, alongside inconsistent measurement protocols and definitions, further complicates cross-study comparisons [62]. Nevertheless, bone turnover markers provide valuable early insight into bone remodeling processes that may occur before detectable changes in BMD, emphasizing the importance of standardized assessment methods and additional research to fully establish their role in monitoring bone health in REDs.

4.1.6. Limitations of the Evidence

Most included studies forming the evidence were rated as having moderate to high risk of bias, and the consistency of using a standard set of reporting outcome measures was poor. This limits the strength of the evidence base. Reporting on intervention fidelity, participant compliance, and follow-up was often incomplete or unclear, reducing confidence in the consistency and applicability of reported outcomes. These methodological limitations highlight the need for more robust, standardized research in this field. Another limitation is that the standard deviation of change used in the meta-analysis for the Dueck [31] was estimated. It is important to recognize characteristics of the studies that limit the results. These include the variability in diagnostic criteria for REDs and the other conditions identified, inconsistency in definitions of menstrual recovery (e.g., bleeding versus ovulation), and the impact of access to cohorts, which were often based at a university from high-income countries and not fully powered and, in some cases, had very small sample sizes. Where interventions combined pharmacological with non-pharmacological components, the impact of each was not assessed. Finally, REDs is acknowledged as affecting both genders, and this review is limited by a focus on females.

4.1.7. Implications for Practice/Clinical Implications

Implications for Practice (Expanded)

The current review primarily included female athletes engaged in distance and endurance sports, with most non-pharmacological interventions focusing on dietary modifications delivered in university-based settings. Effective management of REDs should begin with restoring energy availability through nutritional strategies, as these remain the cornerstone of treatment and are consistently supported by evidence. Clinicians should avoid relying solely on menstrual status or body composition as indicators of recovery; instead, a multidimensional approach is recommended, incorporating hormonally validated markers such as leptin, T3, LH, and estradiol alongside behavioral changes to ensure accurate diagnosis, monitoring, and long-term management.

Hormonal therapies may offer benefits for bone health and symptom relief when nutritional rehabilitation and energy restoration prove insufficient; however, they do not address the underlying cause and can mask true reproductive recovery, warranting cautious use. Combined oral contraceptives, in particular, may induce withdrawal bleeding without restoring ovulatory function, underscoring the need to prioritize non-pharmacological interventions and objective monitoring. Finally, bone turnover markers, such as P1NP and IGF-1, show promise as sensitive indicators of bone metabolism, but their clinical utility remains limited by variability and insufficient evidence, highlighting the need for standardized assessment and further research.

Practical Implementation for Clinicians

In practice, clinicians should start by conducting a comprehensive assessment of energy availability, dietary intake, and training load, ideally in collaboration with a sports dietitian. Establishing realistic nutritional goals and monitoring adherence through food diaries or digital tracking tools can help ensure progress. Hormonal profiles and bone markers should be integrated into routine evaluations, using consistent timing and validated assays to improve reliability. When considering hormonal therapy, clinicians should clearly communicate its role as an adjunct rather than a primary treatment and set expectations regarding its limitations in restoring ovulatory function. Regular multidisciplinary reviews involving dietitians, psychologists, and sports physicians can support behavioral change and optimize long-term outcomes.

Implications for Research Design

Future research should move beyond small, single-center studies and prioritize larger, multi-center trials to improve generalizability and statistical power. Inclusion of male athletes is essential to address current gender gaps and broaden the applicability of the findings. Standardization of REDs diagnostic criteria and core outcome sets—including hormonal markers, bone health indicators, and validated measures of energy availability—would enhance comparability across studies. Longer follow-up periods are needed to capture sustained changes in bone mineral density and reproductive function, as short-term interventions may not reflect long-term recovery. Additionally, integrating behavioral and psychological outcomes alongside physiological markers could provide a more comprehensive understanding of treatment efficacy.

5. Conclusions

Non-pharmacological interventions, predominantly dietary energy restoration and adjustments to training load, consistently demonstrate benefits on clinically relevant outcomes in athletes with REDs. However, the certainty of this evidence is often low to moderate due to methodological limitations such as small sample sizes, short follow-up periods, and heterogeneity in outcome measures. In contrast, pharmacological interventions, including hormonal therapies, appear to improve bone mineral density and certain hormonal parameters, yet they do not address the underlying issue of low energy availability and may obscure true reproductive recovery. These findings underscore the importance of prioritizing nutritional and behavioral strategies as first-line management while reserving pharmacological approaches for carefully selected cases and ensuring ongoing monitoring of physiological recovery. Further research is needed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/sports13120453/s1, File S1: PRISMA flow diagram [63]; File S2: Critical appraisal results; File S3: Certainty Assessment results.

Author Contributions

Study conceptualization, A.N.W. and A.S.; methodology, A.N.W. and A.S.; narrative synthesis, A.N.W.; meta-analysis, A.S.; review processes, A.N.W. and A.S.; writing—original draft and subsequent drafts, A.N.W. and A.S.; supervision, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was obtained for the project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Critical appraisal, narrative synthesis, and meta-analysis data are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mountjoy, M.; Ackerman, K.E.; Bailey, D.M.; Burke, L.M.; Constantini, N.; Hackney, A.C.; Heikura, I.A.; Melin, A.; Pensgaard, A.M.; Stellingwerff, T.; et al. 2023 International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) consensus statement on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs). Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 1073–1098, Erratum in Br. J. Sports Med. 2024, 7, e4. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2023-106994corr1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeukendrup, A.E.; Areta, J.L.; Genechten, L.V.; Langan-Evans, C.; Pedlar, C.R.; Rodas, G.; Sale, C.; Walsh, N.P. Does relative energy deficiency in sport (REDs) syndrome exist? Sports Med. 2025, 54, 2793–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, K.K.; Agostini, R.; Nattiv, A.; Drinkwater, A. The female athlete triad: Disordered eating, amenorrhea, osteoporosis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1993, 25, 775–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidi, A.M.; Stefanakis, K.; Chou, S.H.; Valenzuela-Vallejo, L.; Dipla, K.; Boutari, C.; Ntoskas, K.; Tokmakidis, P.; Kokkinos, A.; Goulis, D.G.; et al. Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs): Endocrine Manifestations, Pathophysiology and Treatments. Endocr. Rev. 2024, 45, 676–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavrilova, E.A.; Churganov, O.A.; Pavlova, O.Y.; Bryntseva, E.V.; Rasskazova, A.V.; Gorkin, M.V.; Sarkisov, A.K.; Didora, A.B.; Shitova, V.I. The Commonality of Overtraining Syndrome and Relative Energy Deficit Syndrome in Sports (REDs). Literature Review. Hum. Physiol. 2024, 50, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasa, M.S.; Fribogr, O.; Kristoffersen, M.; Pettersen, G.; Sagen, J.V.; Torstviet, M.K.; Sundogt-Borgen, J.; Rosenvinge, J.H. Risk and prevalence of relative energy deficiency in sport (REDs) among professional female football players. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2024, 24, 1032–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesbreno, E.; Blondin, D.P.; Dziedzic, C.; Sygo, J.; Haman, F.; Leclerc, S.; Brazeau, A.S.; Mountjoy, M. Signs of low energy availability in elite male volleyball athletes but no association with risk of bone stress injury and patellar tendinopathy. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2023, 23, 2067–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzuki, M.I.H.; Mohamad, M.I.; Chai, W.J.; Farah, N.M.F.; Safii, N.S.; Jasme, J.K.; Jamil, N.A. Prevalence of Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) among National Athletes in Malaysia. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M.A.; Appaneal, R.N.; Hughes, D.; Vlahovich, N.; Waddington, G.; Burke, L.M.; Drew, M. Prevalence of impaird physiological function consistent with relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S): An Australian elite and pre-elite cohort. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 55, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meczekalski, B.; Katulski, K.; Czyzyk, A.; Podfigurna-Stopa, A.; Maciejewska-Jeske, M. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea and its influence on women’s health. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2014, 37, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torstveit, M.K.; Ackerman, K.E.; Constantini, N.; Holtzman, B.; Koehler, K.; Mountjoy, M.L.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Melin, A. Primary, secondary and tertiary prevention of relative energy deficiency in Sport (REDs): A narrative review by a subgroup of the IOC consensus on REDs. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stellingwerff, T.; Heikura, I.A.; Meeusen, R.; Bermon, S.; Seiler, S.; Mountjoy, M.L.; Burke, L.M. Overtraining Syndrome (OTS) and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S): Shared Pathways, Symptoms and Complexities. Sports Med. 2021, 51, 2251–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logue, D.M.; Madigan, S.M.; Melin, A.; Delahunt, E.; Heinen, M.; Donnell, S.-J.M.; Corish, C.A. Low Energy Availability in Athletes 2020: An Updated Narrative Review of Prevalence, Risk, Within-Day Energy Balance, Knowledge, and Impact on Sports Performance. Nutrients 2020, 12, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuna, M.; Hetnar, P.; Kiper, S.; Toczek, S.; Tomala, M.; Jastrowicz-Chec, K.; Korysko Klaudia, K.; Pokrywka, N.; Suala, D.; Polak, M. Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S): A Systematic Overview of Mechanisms, Effects, and Clinical Implications. Qual. Sport 2025, 42, 60506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, A.K.; Heikura, I.A.; Tenforde, A.; Mountjoy, M. Energy Availability in Athletics: Health, Performance, and Physique. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2019, 29, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, K.E.; Singhal, V.; Baskaran, C.; Slattery, M.; Campoverde Reyes, K.J.; Toth, A.; Eddy, K.T.; Bouxsein, M.L.; Lee, H.; Klibanski, A.; et al. Oestrogen replacement improves bone mineral density in oligo-amenorrhoeic athletes: A randomised clinical trial. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountjoy, M.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.K.; Burke, L.M.; Ackerman, K.E.; Blauwet, C.; Constantini, N.; Lebrun, C.; Lundy, B.; Melin, A.K.; Meyer, N.L.; et al. IOC consensus statement on relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S): 2018 update. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapik, J.; Montain, S.J.; McGraw, S.; Grier, T.; Ely, M.; Jones, B.H. Stress fracture risk factors in basic combat training. Int. J. Sports Med. 2012, 33, 940–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenforde, A.S.; Barrack, M.T.; Nattiv, A.; Fredericson, M. Parallels with the Female Athlete Triad in Male Athletes. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardern, C.L.; Büttner, F.; Andrade, R.; Weir, A.; Ashe, M.C.; Holden, S.; Impellizzeri, F.M.; Delahunt, E.; Dijkstra, H.P.; Mathieson, S.; et al. Implementing the 27 PRISMA 2020 Statement items for systematic reviews in the sport and exercise medicine, musculoskeletal rehabilitation and sports science fields: The PERSiST (implementing Prisma in Exercise, Rehabilitation, Sport medicine and SporTs science) guidance. Br. J. Sports Med. 2022, 56, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Glasziou, P.P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Barbour, V.; Macdonald, H.; Johnston, M.; et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014, 348, g1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.; Higgins, J. The Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies—Of Interventions, Version 2 (ROBINS-I V2). 2024. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/riskofbiastool/welcome/robins-i-v2 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borenstein, M.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Hedges, L.V.; Rothstein, H.R. Basics of meta-analysis: I2 is not an absolute measure of heterogeneity. Res. Synth. Methods 2017, 8, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M. Introduction to the GRADE tool for rating certainty in evidence and recommendations. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2024, 25, 101484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arends, J.C.; Cheung, M.Y.C.; Barrack, M.T.; Nattiv, A. Restoration of menses with nonpharmacologic therapy in college athletes with menstrual disturbances: A 5-year retrospective study. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2012, 22, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdella-Kam, L.; Guebels, C.P.; Maddalozzo, G.F.; Manore, M.M. Dietary intervention restored menses in female athletes with exercise-associated menstrual dysfunction with limited impact on bone and muscle health. Nutrients 2014, 6, 3018–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza, M.J.; Mallinson, R.J.; Strock, N.C.A.; Koltun, K.J.; Olmsted, M.P.; Ricker, E.A.; Scheid, J.L.; Allaway, H.C.; Mallinson, D.J.; Kuruppumullage Don, P.; et al. Randomised controlled trial of the effects of increased energy intake on menstrual recovery in exercising women with menstrual disturbances: The ‘REFUEL’ study. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 36, 2285–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, M.J.; Ricker, E.A.; Mallinson, R.J.; Allaway, H.C.M.; Koltun, K.J.; Strock, N.C.A.; Gibbs, J.C.; Kuruppumullage Don, P.; Williams, N.I. Bone mineral density in response to increased energy intake in exercising women with oligomenorrhea/amenorrhea: The REFUEL randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 1457–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueck, C.A.; Matt, K.S.; Manore, M.M.; Skinner, J.S. Treatment of athletic amenorrhea with a diet and training intervention program. Int. J. Sport Nutr. 1996, 6, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrenholtz, I.L.; Melin, A.K.; Garthe, I.; Hollekim-Strand, S.M.; Ivarsson, A.; Koehler, K.; Logue, D.; Lundström, P.; Madigan, S.; Wasserfurth, P.; et al. Effects of a 16-Week Digital Intervention on Sports Nutrition Knowledge and Behavior in Female Endurance Athletes with Risk of Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs). Nutrients 2023, 15, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredericson, M.; Roche, M.; Barrack, M.T.; Tenforde, A.; Sainani, K.; Kraus, E.; Kussman, A.; Miller Olson, E.; Kim, B.Y.; Fahy, K.; et al. Healthy Runner Project: A 7-year, multisite nutrition education intervention to reduce bone stress injury incidence in collegiate distance runners. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2023, 9, e001545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guebels, C.P.; Kam, L.C.; Maddalozzo, G.F.; Manore, M.M. Active women before/after an intervention designed to restore menstrual function: Resting metabolic rate and comparison of four methods to quantify energy expenditure and energy availability. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2014, 24, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp-Woodroffe, S.A.; Manore, M.M.; Dueck, C.A.; Skinner, J.S.; Matt, K.S. Energy and Nutrient Status of Amenorrheic Athletes Participating in a Diet and Exercise Training Intervention Program. Int. J. Sport Nutr. 1999, 9, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagowska, K.; Kapczuk, K.; Jeszka, J. Nine-month nutritional intervention improves restoration of menses in young female athletes and ballet dancers. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2014, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łagowska, K.; Kapczuk, K.; Friebe, Z.; Bajerska, J. Effects of dietary intervention in young female athletes with menstrual disorders. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2014, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallinson, R.J.; Williams, N.I.; Olmsted, M.P.; Scheid, J.L.; Riddle, E.S.; De Souza, M.J. A case report of recovery of menstrual function following a nutritional intervention in two exercising women with amenorrhea of varying duration. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2013, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.; Haigis, D.; Klos, B.; Zipfel, S.; Resmark, G.; Rall, K.; Dreser, K.; Hagmann, D.; Nieß, A.; Kopp, C.; et al. Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport—Multidisciplinary Treatment in Clinical Practice. Nutrients 2025, 17, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michopoulos, V.; Mancini, F.; Loucks, T.L.; Berga, S.L. Neuroendocrine recovery initiated by cognitive behavioral therapy in women with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea: A randomized, controlled trial. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 99, 2084–2091.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solstad, B.E.; Fahrenholtz, I.L.; Melin, A.; Garthe, I.; Torstveit, M.K. Participant evaluations of the FUEL intervention designed for female endurance athletes at risk of REDs. A mixed methods approach. Sports Psychiatry 2025, 4, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadgostar, H.; Soleimany, G.; Movaseghi, S.; Dadgostar, E.; Lotfian, S. The effect of hormone therapy on bone mineral density and cardiovascular factors among Iranian female athletes with amenorrhea/oligomenorrhea: A randomized clinical trial. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2018, 32, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, J.H.; Mitchell, A.; Reeve, J.; Harries, M.G. Treatment of reduced bone mineral density in athletic amenorrhea: A pilot study. Osteoporos. Int. 1999, 10, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, M.P.; Brooks-Gunn, J.; Fox, R.P.; Holderness, C.C.; Hyle, E.P.; Hamilton, W.G.; Hamilton, L. Persistent osteopenia in ballet dancers with amenorrhea and delayed menarche despite hormone therapy: A longitudinal study. Fertil. Steril. 2003, 80, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, M.J.; West, S.L.; Jamal, S.A.; Hawker, G.A.; Gundberg, C.M.; Williams, N.I. The presence of both an energy deficiency and estrogen deficiency exacerbate alterations of bone metabolism in exercising women. Bone 2008, 43, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucks, A.B.; Thuma, J.R. Luteinizing Hormone Pulsatility Is Disrupted at a Threshold of Energy Availability in Regularly Menstruating Women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza, M.J.; Nattiv, A.; Joy, E.; Misra, M.; Williams, N.I.; Mallinson, R.J.; Gibbs, J.C.; Olmsted, M.; Goolsby, M.; Matheson, G.; et al. 2014 Female Athlete Triad Coalition Consensus Statement on Treatment and Return to Play of the Female Athlete Triad: 1st International Conference held in San Francisco, California, May 2012 and 2nd International Conference held in Indianapolis, Indiana, May 2013. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountjoy, M.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Burke, L.; Carter, S.; Constantini, N.; Lebrun, C.; Meyer, N.; Sherman, R.; Steffen, K.; Budgett, R.; et al. The IOC consensus statement: Beyond the Female Athlete Triad—Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nattiv, A.; Loucks, A.B.; Manore, M.M.; Sanborn, C.F.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Warren, M.P.; American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. The female athlete triad. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007, 39, 1867–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, K.E.; Singhal, V.; Slattery, M.; Eddy, K.T.; Bouxsein, M.L.; Lee, H.; Klibanski, A.; Misra, M. Effects of Estrogen Replacement on Bone Geometry and Microarchitecture in Adolescent and Young Adult Oligoamenorrheic Athletes: A Randomized Trial. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2020, 35, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, A.; Tornberg, Å.B.; Skouby, S.; Møller, S.S.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Faber, J.; Sidelmann, J.J.; Aziz, M.; Sjödin, A. Energy availability and the female athlete triad in elite endurance athletes. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2015, 25, 610–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastorakos, G.; Pavlatou, M.; Diamanti-Kandarakis, E.; Chrousos, G.P. Exercise and the stress system. Hormones 2005, 4, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Misra, M.; Klibanski, A. Endocrine consequences of anorexia nervosa. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indirli, R.; Lanzi, V.; Mantovani, G.; Maura, A.; Ferrante, E. Bone health in functional hypothalamic amenorrhea: What the endocrinologist needs to know. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 946695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalberg, K.; Stavem, K.; Norheim, F.; Russell, M.B.; Chaibi, A. Effect of oral and transdermal oestrogen therapy on bone mineral density in functional hypothalamic amenorrhoea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2021, 7, e001112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelingh Bennink, H.J.T.; van Gennip, F.A.M.; Gerrits, M.G.F.; Egberts, J.F.M.; Gemzell-Danielsson, K.; Kopp-Kallner, H. Health benefits of combined oral contraceptives—A narrative review. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2024, 29, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, C.M.; Ackerman, K.E.; Berga, S.L.; Kaplan, J.R.; Mastorakos, G.; Misra, M.; Murad, M.H.; Santoro, N.F.; Warren, M.P. Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 1413–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchard, T.; Yong, P.; Doyle-Baker, P. Establishing a gold standard for quantitative menstrual cycle monitoring. Medicina 2023, 59, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaniyi, G.G.; Ajao, B.H.; Akor, U.J.; Babaniyi, E. Reproductive endocrinology drug development Hormones metabolism fertility in female reproductive health. In Perspective of Quorum Quenching in New Drug Development, 1st ed.; Maddela, N.R., Thiriveedi, V., Siliya, L.R., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Cai, W. Bone metabolism factors in predicting the risk of osteoporosis fracture in the elderly. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2024, 25, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastell, R.; Szulc, P. Use of bone turnover markers in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 5, 908–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banfi, G.; Lombardi, G.; Colombini, A.; Lippi, G. Bone metabolism markers in sports medicine. Sports Med. 2010, 40, 697–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).