Warming Up for Basketball: Comparing Traditional vs. Small-Sided Game Approaches in Youth Players

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

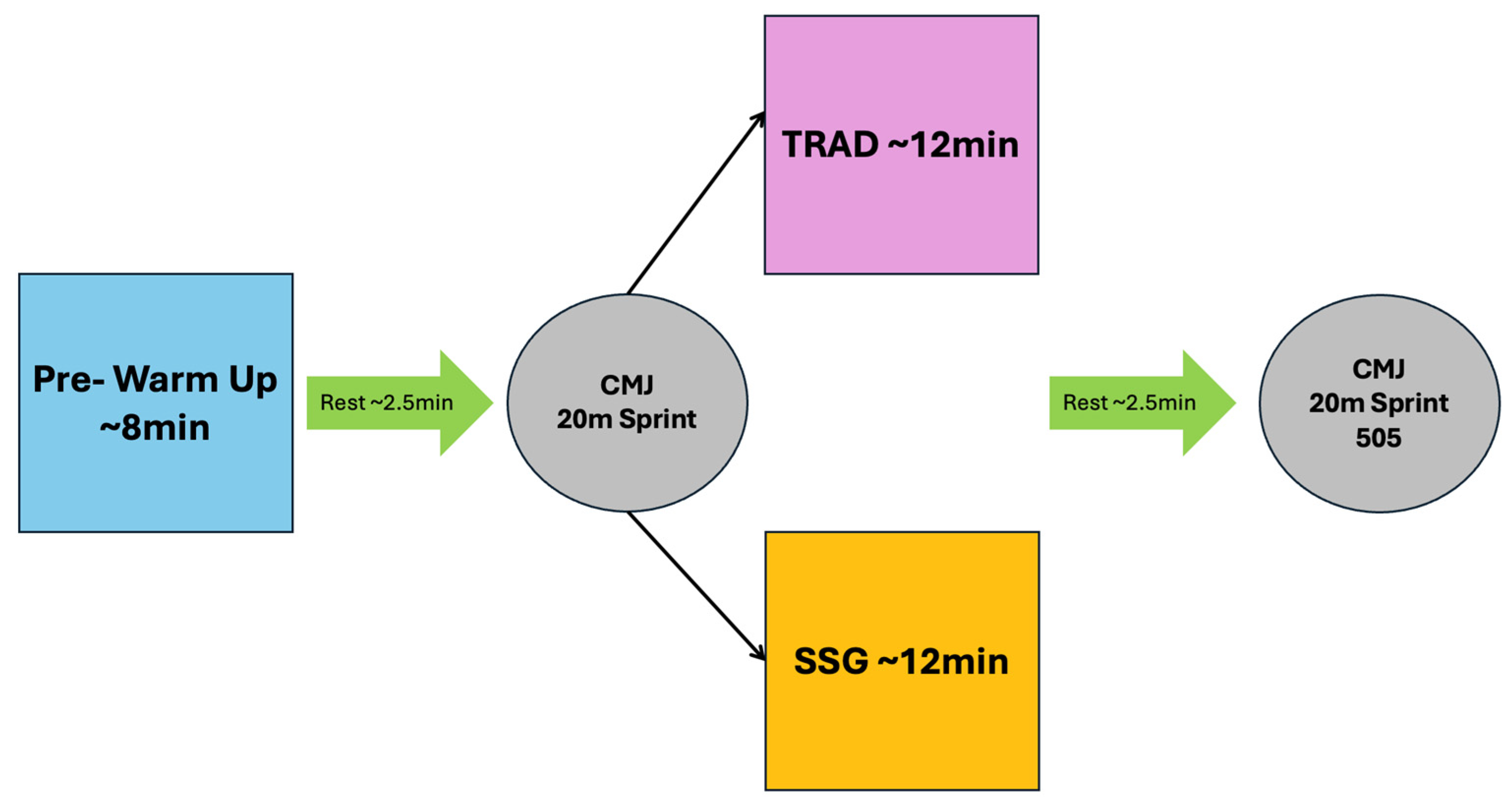

2.2. Design

2.3. Procedures

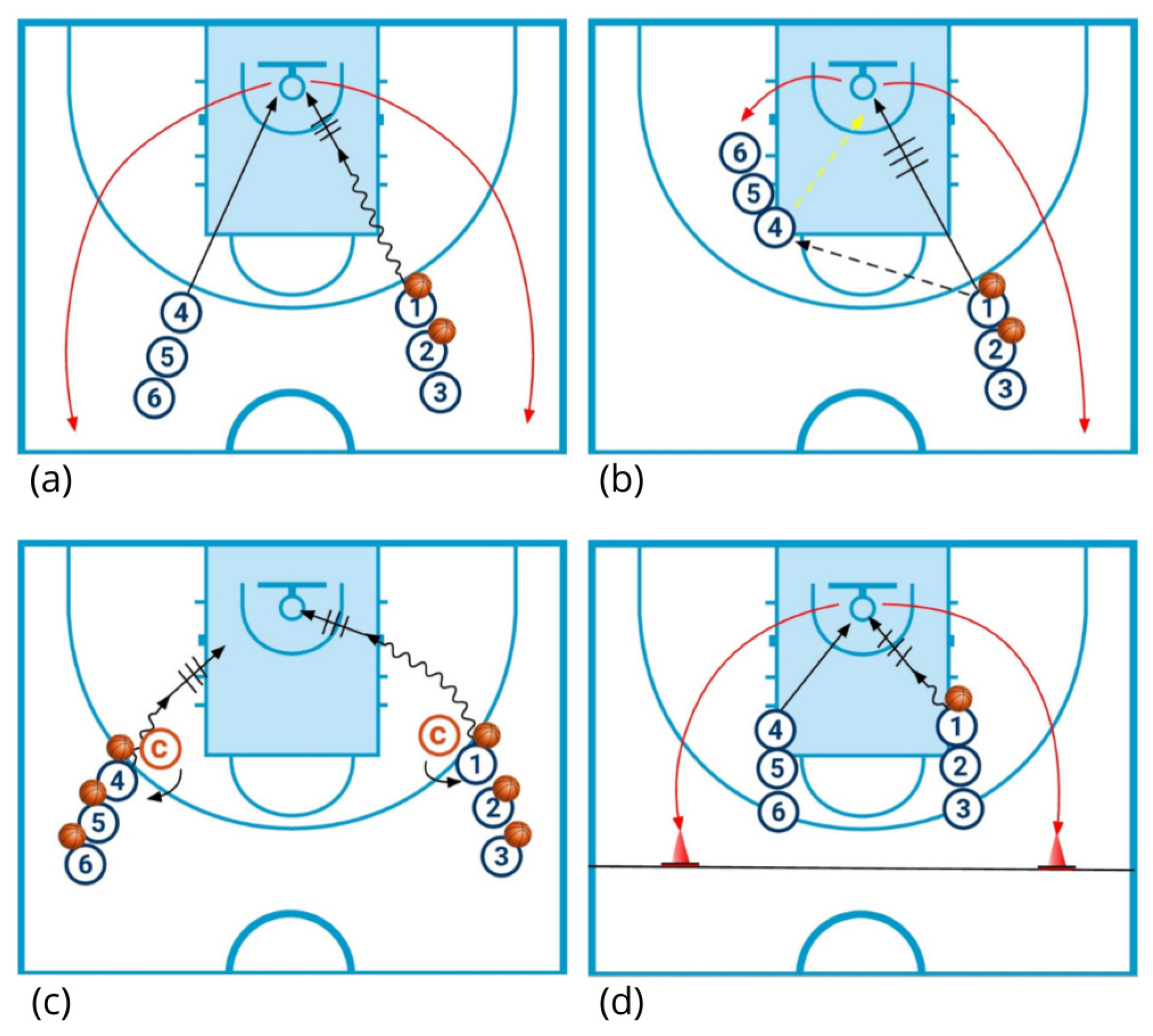

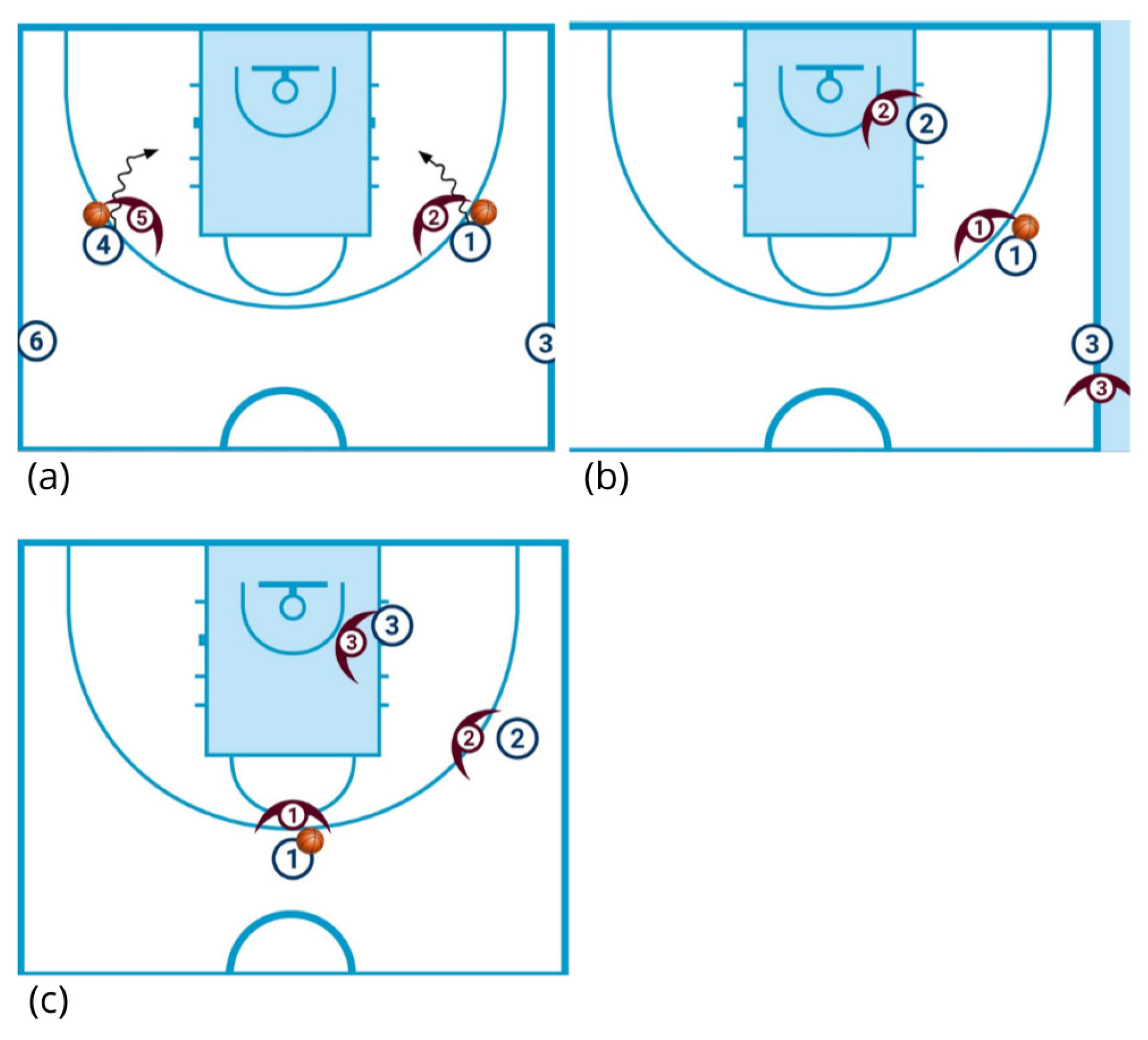

2.3.1. Warm-Up Typologies

2.3.2. Load Monitoring

2.3.3. Performance Tests

2.3.4. Perceived Fatigue and Enjoyment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

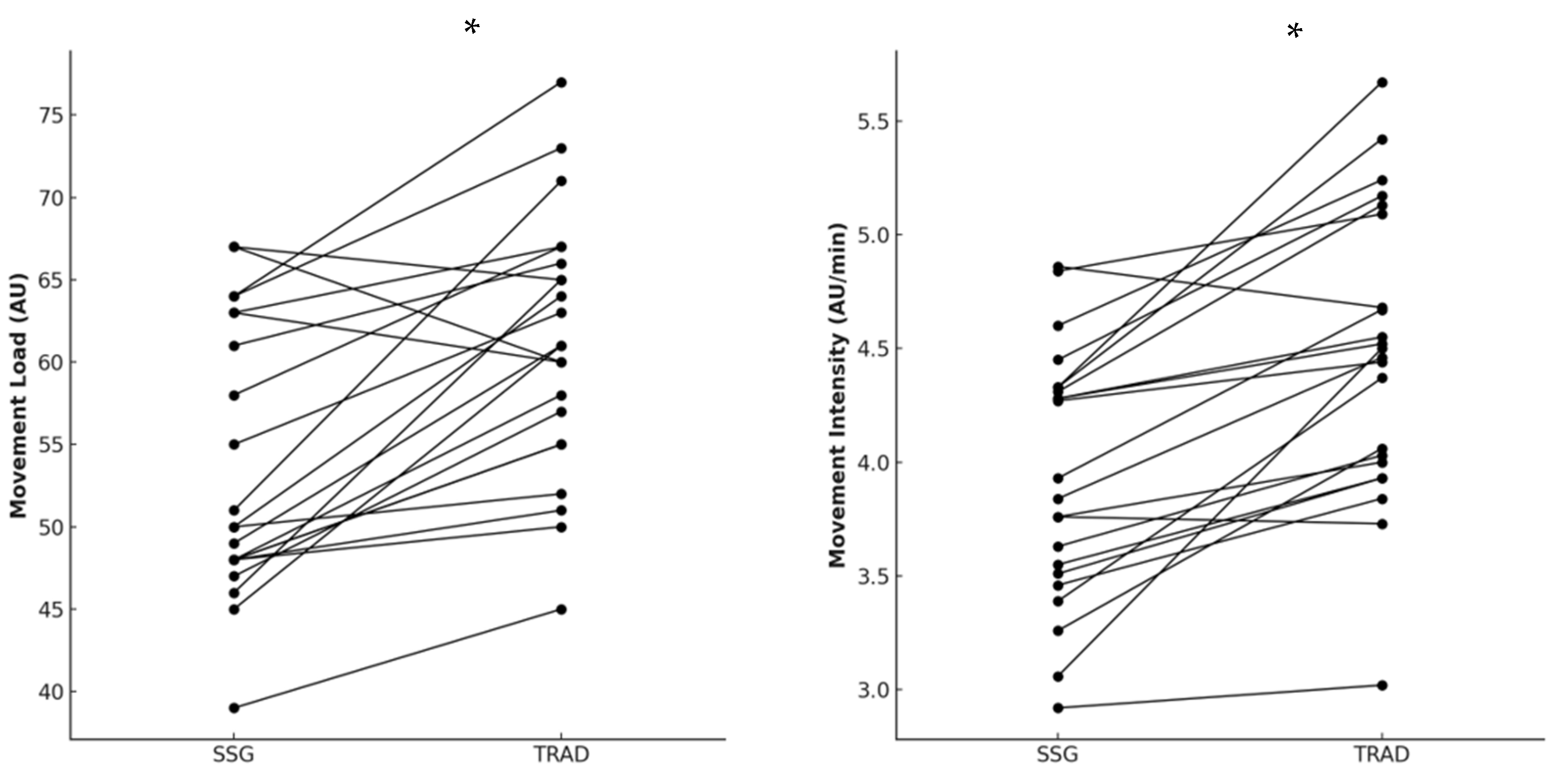

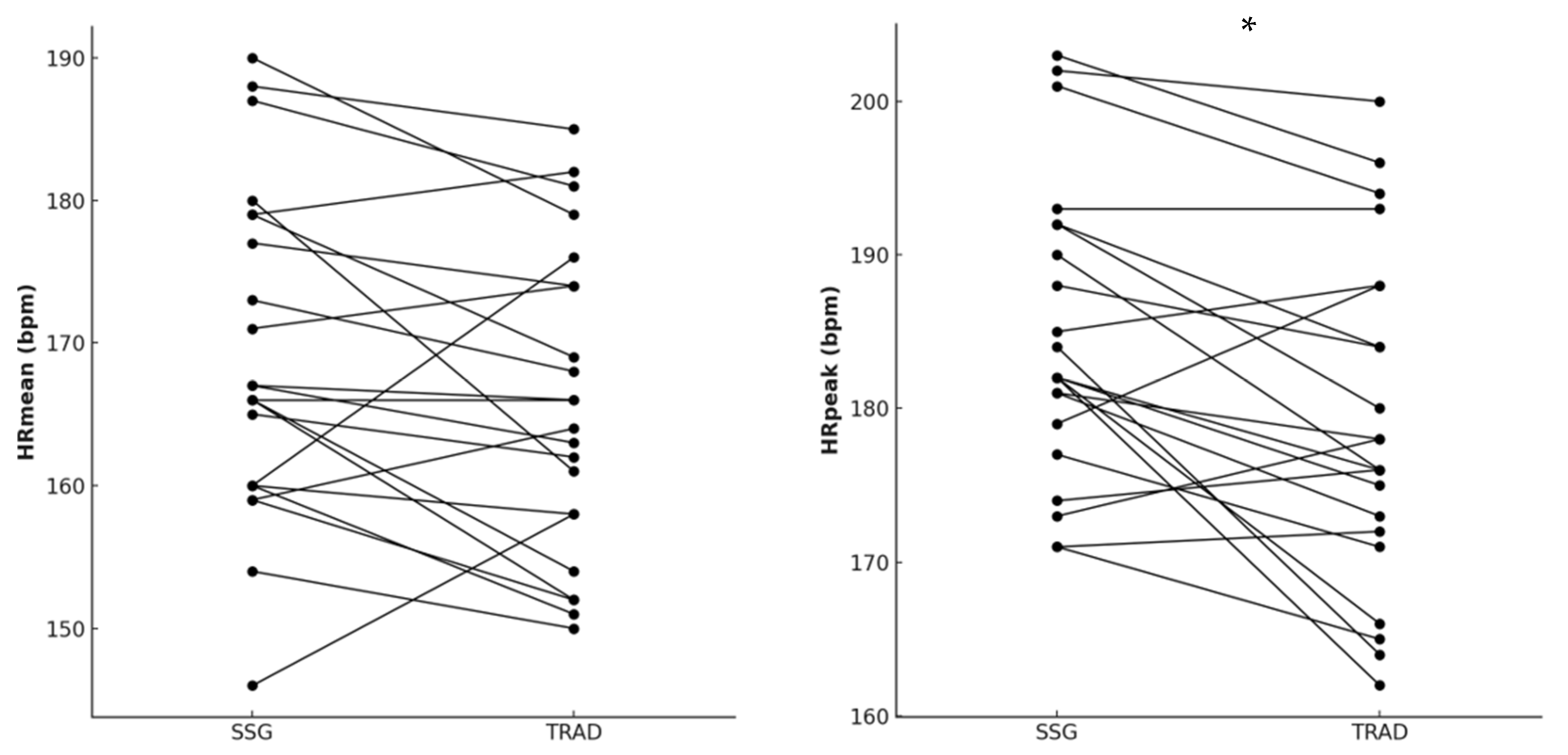

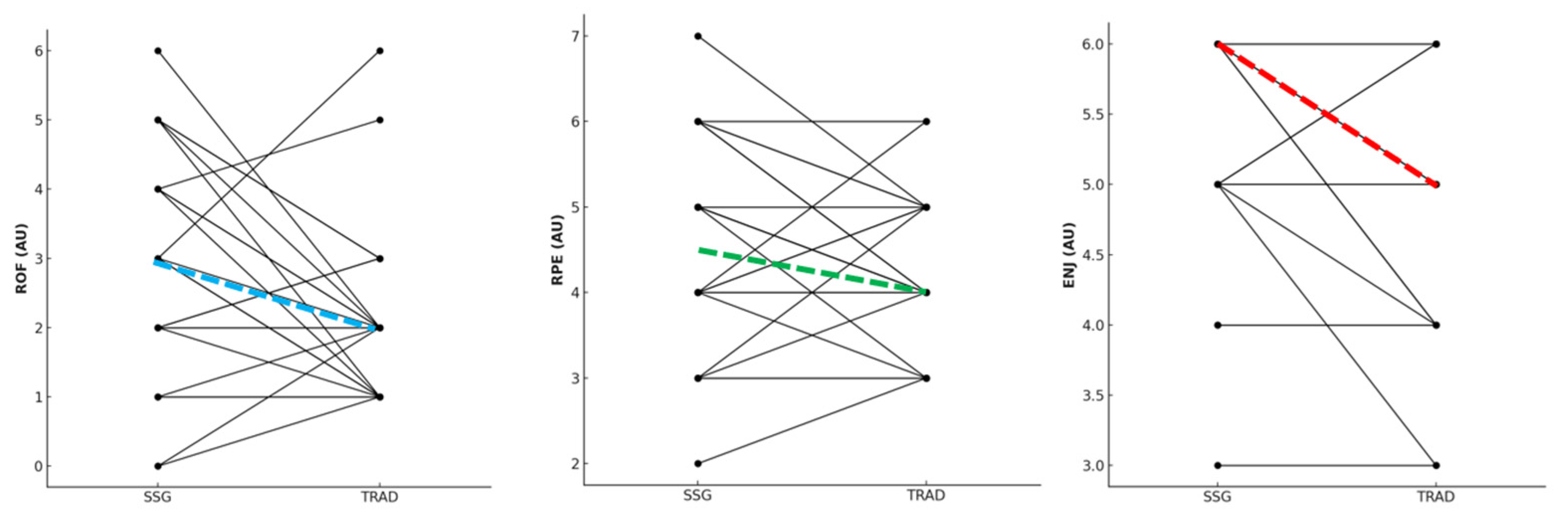

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stojanović, E.; Stojiljković, N.; Scanlan, A.T.; Dalbo, V.J.; Berkelmans, D.M.; Milanović, Z. The activity demands and physiological responses encountered during basketball match-play: A systematic review. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, D.T.; Williams, A.M.; Ward, P.; Janelle, C.M. Perceptual-cognitive expertise in sport: A meta-analysis. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2007, 29, 457–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferioli, D.; Rampinini, E.; Martin, M.; Rucco, D.; Torre, A.; Petway, A.; Scanlan, A. Influence of ball possession and playing position on the physical demands encountered during professional basketball games. Biol. Sport 2020, 37, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flórez-Gil, E.; Boullosa, D.; Calleja-González, J.; Vaquera, A. A cross-national survey of basketball strength and conditioning coaches’ warm-up practices. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2025, 20, 1501–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelling, X.; Fernández, J.; Ward, P.; Fernández, J.; Robertson, S. Decision support system applications for scheduling in professional team sport: The team’s perspective. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 678489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGowan, C.J.; Pyne, D.B.; Thompson, K.G.; Rattray, B. Warm-up strategies for sport and exercise: Mechanisms and applications. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 1523–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aerts, I.; Cumps, E.; Verhagen, E.; Wuyts, B.; Van De Gucht, S.; Meeusen, R. The effect of a 3-month prevention program on the jump-landing technique in basketball: A randomized controlled trial. J. Sport Rehabil. 2015, 24, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-García, J.; Rubio-Morales, A.; Manzano-Rodríguez, D.; García-Calvo, T.; Ring, C. Cognitive priming during warmup enhances sport and exercise performance: A Goldilocks effect. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa Fortes, L.; Paes, P.P.; Mortatti, A.L.; Perez, A.J.; Cyrino, E.S.; de Lima-Júnior, D.R.A.A.; Moreira, A. Effect of different warm-up strategies on countermovement jump and sprint performance in basketball players. Isokinet. Exerc. Sci. 2018, 26, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrillo-Sanchis, J.; Muñoz-Criado, I.; Pérez-Puchades, V.; Palmero-Martín, I.; Galcerán-Ruiz, J.; Portes-Sanchez, R.; Chulvi-Medrano, I.; Domínguez-Navarro, F.; Morales-Hilario, E.; Mur-Gomar, B.; et al. Applying a specific warm-up on basketball performance: The Basket-Up approach. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Basketball Association. Advanced Stats. 2020. Available online: https://www.nba.com/stats/teams/advanced/ (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Sansone, P.; Gasperi, L.; Makivic, B.; Gomez-Ruano, M.A.; Tessitore, A.; Conte, D. An ecological investigation of average and peak external load intensities of basketball skills and game-based training drills. Biol. Sport 2023, 40, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bredt, S.G.; de Souza Camargo, D.; Vidigal Borges Mortoza, B.; Pereira de Andrade, A.G.; Paolucci, L.A.; Lemos Nascimento Rosso, T.; Moreira Praça, G.; Chagas, M.H. Additional players and half-court areas enhance group tactical-technical behavior and decrease physical and physiological responses in basketball small-sided games. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2022, 17, 1079–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zois, J.; Bishop, D.; Aughey, R. High-intensity warm-ups: Effects during subsequent intermittent exercise. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2015, 10, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, R.K.; Clemente, F.M.; Moran, J.; Garcia-Pinillos, F.; Scanlan, A.T.; Ramirez-Campillo, R. Warm-up optimization in amateur male soccer players: A comparison of small-sided games and traditional warm-up routines on physical fitness qualities. Biol. Sport 2023, 40, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dello Iacono, A.; Vigotsky, A.D.; Laver, L.; Halperin, I. Beneficial effects of small-sided games as a conclusive part of warm-up routines in young elite handball players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 1724–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bompa, T.O.; Haff, G.G. Periodization; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, D. Warm up II: Performance changes following active warm up and how to structure the warm up. Sports Med. 2003, 33, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conte, D.; Rampinini, E.; Trimarchi, F.; Ferioli, D. Interunit reliability of Firstbeat Sport sensors as accelerometer-based tracking devices in basketball. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2025, 20, 727–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, C.; Florhaug, J.A.; Franklin, J.; Gottschall, L. A new approach to monitoring exercise training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2001, 15, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernigoni, M.; Calleja-González, J.; Lukonaitienė, I.; Tessitore, A.; Stanislovaitienė, J.; Kamarauskas, P.; Conte, D. Comparative effectiveness of active recovery and static stretching during post-exercise recovery in elite youth basketball. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2024, 95, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, A.; Dhahbi, W.; Chaouachi, A.; Padulo, J.; Wong, D.P.; Chamari, K. Measurement errors when estimating the vertical jump height with flight time using photocell devices: The example of Optojump. Biol. Sport 2017, 34, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernigoni, M.; Perazzetti, A.; Digno, M.; Tessitore, A.; Kamandulis, S.; Conte, D. Chill without thrill: A crossover study on whole-body cryotherapy and postmatch recovery in high-level youth basketball players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2024, 19, 1218–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimphius, S.; McGuigan, M.R.; Newton, R.U. Relationship between strength, power, speed, and change of direction performance of female softball players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010, 24, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micklewright, D.; St Clair Gibson, A.; Gladwell, V.; Al Salman, A. Development and validity of the rating-of-fatigue scale. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 2375–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernigoni, M.; Kreivytė, R.; Lukonaitienė, I.; Toper, C.R.; Kamandulis, S.; Conte, D. Is foam rolling as effective as its popularity suggests? A randomised crossover study exploring post-match recovery in female basketball. J. Sports Sci. 2023, 41, 1718–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendzierski, D.; DeCarlo, K.J. Physical activity enjoyment scale: Two validation studies. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1991, 13, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golluceli, B.; Kamandulis, S.; Pernigoni, M.; Lukonaitiene, I.; Kreivyte, R.; Conte, D. Physiological, perceived, and physical demands of recreational 3×3 basketball and high-intensity interval training in sedentary adult women. Biol. Sport 2025, 42, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, W.G.; Marshall, S.W.; Batterham, A.M.; Hanin, J. Progressive statistics for studies in sports medicine and exercise science. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, C.O.; Morris, P.E.; Richler, J.J. Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2012, 141, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, rev. ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.M.; Hoffman, J.R.; Rogowski, J.P.; Burgos, W.; Manalo, E.; Weise, K.; Fragala, M.S.; Stout, J.R. Performance changes in NBA basketball players vary in starters vs. nonstarters over a competitive season. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 611–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delextrat, A.; Badiella, A.; Saavedra, V.; Matthew, D.; Schelling, X.; Torres-Ronda, L. Match activity demands of elite Spanish female basketball players by playing position. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2015, 15, 687–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, T.; Lenis, G.; Reichensperger, P.; Beran, T.; Doessel, O.; Deml, B. Electrocardiographic features for the measurement of drivers’ mental workload. Appl. Ergon. 2017, 61, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selmi, O.; Haddad, M.; Majed, L.; Ben Khalifa, W.; Hamza, M.; Chamari, K. Soccer training: High-intensity interval training is mood disturbing while small sided games ensure mood balance. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2018, 58, 1163–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Los Arcos, A.; Vázquez, J.S.; Martín, J.; Lerga, J.; Sánchez, F.; Villagra, F.; Zulueta, J.J. Effects of small-sided games vs. interval training in aerobic fitness and physical enjoyment in young elite soccer players. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beato, M.; Madsen, E.E.; Clubb, J.; Emmonds, S.; Krustrup, P. Monitoring readiness to train and perform in female football: Current evidence and recommendations for practitioners. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2024, 19, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

: off-ball run;

: off-ball run;  : ball pass;

: ball pass;  : give-and-go pass;

: give-and-go pass;  : movements while dribbling the ball;

: movements while dribbling the ball;  : shooting;

: shooting;  : switch lines;

: switch lines;  : coach;

: coach;  players without ball;

players without ball;  players with ball.

players with ball.

: off-ball run;

: off-ball run;  : ball pass;

: ball pass;  : give-and-go pass;

: give-and-go pass;  : movements while dribbling the ball;

: movements while dribbling the ball;  : shooting;

: shooting;  : switch lines;

: switch lines;  : coach;

: coach;  players without ball;

players without ball;  players with ball.

players with ball.

: offensive player without ball;

: offensive player without ball;  offensive player with ball.

offensive player with ball.  : defensive player;

: defensive player;  : movements while dribbling the ball.

: movements while dribbling the ball.

: offensive player without ball;

: offensive player without ball;  offensive player with ball.

offensive player with ball.  : defensive player;

: defensive player;  : movements while dribbling the ball.

: movements while dribbling the ball.

| Dependent Variable | TRAD | SSG | P Interaction | P WU Typology | P Time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRE | POST | PRE | POST | ||||

| CMJ (cm) | 47.5 ± 11.4 | 47.4 ± 11.6 | 46.6 ± 11.3 | 46.7 ± 11.6 | 0.804 | 0.047 | 0.996 |

| 20 m (s) | 3.18 ± 0.90 | 2.91 ± 0.89 | 2.93 ± 0.89 | 2.93 ± 0.89 | 0.459 | 0.680 | 0.592 |

| 10 m (s) | 1.86 ± 0.12 | 1.70 ± 0.51 | 1.72 ± 0.52 | 1.69 ± 0.51 | 0.959 | 0.796 | 0.140 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sansone, P.; Vanacore, M.; Lorenzo-Calvo, J.; Bustamante-Sánchez, Á.; Vaquera, A.; Conte, D. Warming Up for Basketball: Comparing Traditional vs. Small-Sided Game Approaches in Youth Players. Sports 2025, 13, 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120452

Sansone P, Vanacore M, Lorenzo-Calvo J, Bustamante-Sánchez Á, Vaquera A, Conte D. Warming Up for Basketball: Comparing Traditional vs. Small-Sided Game Approaches in Youth Players. Sports. 2025; 13(12):452. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120452

Chicago/Turabian StyleSansone, Pierpaolo, Massimiliano Vanacore, Jorge Lorenzo-Calvo, Álvaro Bustamante-Sánchez, Alejandro Vaquera, and Daniele Conte. 2025. "Warming Up for Basketball: Comparing Traditional vs. Small-Sided Game Approaches in Youth Players" Sports 13, no. 12: 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120452

APA StyleSansone, P., Vanacore, M., Lorenzo-Calvo, J., Bustamante-Sánchez, Á., Vaquera, A., & Conte, D. (2025). Warming Up for Basketball: Comparing Traditional vs. Small-Sided Game Approaches in Youth Players. Sports, 13(12), 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120452