Abstract

The use of chemically assisted performance enhancement (CAPE) substances has become a prominent trend in today’s competitive societies. Although evidence suggests that CAPE behaviors across different life domains share common characteristics, no consistent theoretical framework exists for understanding the decision to engage in such behaviors. The aim of the present study was to examine a unified conceptualization of CAPE behaviors in four life domains. A total of 254 participants (64 competitive athletes, 40 recreational exercisers, 67 students, and 83 professionals) completed a survey assessing distal and proximal associations of CAPE behaviors (adapted for each domain). Path analysis used to evaluate the proposed model demonstrated an adequate fit. Results indicated that proximal associations of intentions (i.e., attitudes, norms, and situational temptation) were predicted by distal variables (i.e., social norms and cultural values). Intentions to engage in CAPE behaviors were predicted by attitudes and situational temptation. Goal commitment predicted only the mean of working, studying, or training. Finally, the mean of supplement use was predicted by norms. These findings provide preliminary evidence for a conceptual framework to understand CAPE behaviors across life domains, which may serve as a basis for designing intervention programs aimed at helping individuals make informed decisions about CAPE.

1. Introduction

A widespread phenomenon in modern lifestyle is the chemically assisted performance enhancement (CAPE), defined as the use of drugs for non-medical purposes. In an attempt to pursue excellence, individuals from various disciplines, including students, academics, athletes, and recreational exercisers, use drugs to enhance their intelligence, abilities, performance, and fitness [1,2]. Two main categories of CAPE have been identified: the use of drugs to improve physical performance and appearance and the use of drugs for cognitive enhancement (neuroenhancement).

CAPE behaviors are found in both physical and mental areas, with people in many fields using these methods to boost their abilities or gain a competitive edge. With respect to physical performance, CAPE refers to the use of doping substances (e.g., anabolic steroids), dietary supplements, and other over-the-counter products by athletes or other professionals (e.g., military officers) to enhance their physical performance [3,4,5]. Moreover, recreational exercisers use these substances for appearance purposes, such as increasing muscle mass and reducing body fat [6,7]. For cognitive enhancement, CAPE includes drugs (e.g., methylphenidate, modafinil) used by students, academics, and professionals (e.g., doctors) to improve concentration, manage stress, and reduce sleep needs [8,9]. While doping in sport and neuroenhancement in academic or professional contexts differ in their social meaning and regulatory status, both can be conceptualized as manifestations of CAPE behaviors that share common psychological mechanisms.

Regarding prevalence, sport and exercise are the most commonly studied CAPE behaviors. Although accurately estimating the prevalence of doping in sports is challenging, research indicates that between 14% and 39% of competitive athletes have experience with doping substances, depending on the sport, country, and competitive level [4,7]. However, using the randomized response technique, Ulrich et al. [10] found that the prevalence could be as high as 57.1% in elite competitions. In recreational sports, evidence suggests that 19.3% of exercisers have had some experience with doping substances [7], while 15% to 26% of non-users are considering or are curious about the effects of these substances [11,12]. Furthermore, military personnel and police officers are also at risk of using such substances [13,14]. A study of personnel in the US Navy and Marine Corps revealed that 73% of participants regularly used nutritional supplements [15]. The prevalence rates of neuroenhancement are similarly high and might even be underestimated [16]. Estimates suggest 6.9–55% of college students, 4% of school children, 9.73% of teachers, 19% of professionals in economics, 8.9% of surgeons, and 4.2% of the general population misuse drugs to improve cognitive function [8,17,18,19,20,21]. However, it has been suggested that prevalence may vary across different cultures [21].

Despite the commonalities in CAPE behaviors across different contexts, existing literature lacks a unified conceptual understanding of the psychological mechanisms that lead individuals to engage in these behaviors. The present study aims to address this gap by providing preliminary evidence for a model that unifies and extends existing conceptualizations of CAPE behaviors across sport and lifestyle domains.

Previous research has frequently employed the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [22] to examine performance enhancement intentions, showing that attitudes (i.e., evaluations of the behavior), subjective norms (i.e., perceived social pressure), and perceived behavioral control (i.e., perceived ability to perform the behavior) are consistent predictors in both competitive and recreational sport [23,24,25]. Extensions of this work have also applied the TPB framework to neuroenhancement, where past behavior, attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived ease of access were found to predict intentions to use substances such as caffeine tablets or prescription stimulants [26,27,28,29,30]. While this evidence highlights the utility of TPB across different CAPE contexts, the model has been criticized for its limited scope, as it does not account for distal or background factors that indirectly shape intentions. The Integrative Model of Behavioral Prediction (IMBP) [31] addresses this limitation by incorporating distal variables (e.g., beliefs, achievement goals, situational temptation, anticipated regret, descriptive norms) and background characteristics, which indirectly influence attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Studies in competitive sport have confirmed the utility of this extended framework [32,33]. Research has shown that personality traits such as sensation seeking and risk perception play an important role in doping and related CAPE behaviors. Higher levels of sensation seeking have been linked with greater willingness to experiment with performance-enhancing substances, while lower perceptions of risk are associated with stronger performance enhancement intentions [34,35,36]. These findings suggest that psychological dispositions interact with social-cognitive predictors to shape engagement in CAPE, and they can be conceptualized within the IMBP [31] as distal or background variables indirectly influencing attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. CAPE behaviors in sport and other domains share structural similarities suggesting findings from one domain could apply to another [37]. Therefore, although the IMBP has not yet been applied in neuroenhancement, it can be assumed to effectively describe the decision-making process in this context as well. Evidence has confirmed the effect of distal variables on proximal predictors (e.g., attitudes) of CAPE behaviors. For instance, individuals who perceive these drugs as harmless, feel confident about their knowledge of safe usage, are more competitive and have surface motives hold more positive attitudes toward their use [38,39]. Similarly, perceived unfairness and academic performance have been linked to more negative attitudes [38,39].

Although the IMBP has been shown to effectively predict CAPE intentions and behaviors, it suggests that it represents the end of a decision-making process. However, Petróczi [40] proposed that doping serves as a means for performance enhancement, while Wolff and Brand [37] argued that the use of enhancers is a means to achieve significant ends in both sports and everyday life (e.g., winning a medal or succeeding academically). Tsorbatzoudis et al. [41] further advocated that doping is a means to an end rather than an end in itself. It is reasonable to assume that performance enhancement is not the ultimate reason for engaging in CAPE behaviors. Instead, performance enhancement is a necessary step for individuals to achieve higher-order goals (e.g., money, fame) [42]. In this sense, CAPE behaviors can be viewed as steps toward achieving an individual’s higher goals through performance enhancement. Although this process has not yet been examined in the sport literature, the Goal Systems Theory [43] could serve as a robust theoretical framework to support this hypothesis.

The Goal Systems Theory is a motivational cognitive approach suggesting that goal systems comprise mental networks where goals are cognitively linked to means of attainment, while means are also connected to other means [43]. According to the theory, multiple means may be associated with a particular goal; for example, proper diet, adequate sleep, and nutritional supplements can help an athlete achieve the ultimate goal of participating in the Olympic Games. Furthermore, means are connected with other means; proper diet, sufficient sleep, and nutritional supplements improve athletes’ performance, which is an essential means to achieving the ultimate goal of Olympic participation. Additionally, multiple goals might be linked to a single means; for instance, performance enhancement is expected to result in participation in the Olympic Games and securing better contracts. The strength of the cognitive links between goals and means is determined by their number; when the number of means is small, the link between them is stronger. The theory also emphasizes goal commitment and goal difficulty as crucial factors influencing the quality of implementing the chosen means ultimately affecting the achievement of the pursued goals [43]. According to the theory, the strength of an individual’s intention toward a behavior, e.g., doping, depends on both the perceived value of the goal and the perceived instrumentality of the means. When a means (e.g., a specific behavior) is strongly associated with a valued goal, individuals are more likely to form strong intentions to engage in that behavior. Moreover, goal difficulty and commitment play critical roles: difficult but attainable goals tend to enhance commitment, which in turn increases the likelihood of pursuing relevant means. Thus, the alignment between means, goal value, and personal commitment determines the motivational strength underlying behavioral intentions [43].

The Present Study

Existing evidence suggests that CAPE behaviors across different sport and lifestyle contexts share several commonalities [37]. For instance, common theoretical approaches have been tested in various life domains, such as sports, exercise and academia. However, no studies have yet adopted a unified theoretical framework to understand the psychological processes underlying the decision to engage in these behaviors. The present study aims to preliminarily test the integration of these approaches into a common theoretical framework suitable for describing the underlying processes leading to CAPE behaviors across four life domains: sport, exercise, studentship, and work. Although dietary supplements, prescription drugs, and illicit doping substances differ considerably in terms of accessibility, legal status, and associated health risks, they were included under the same conceptual framework to capture the full spectrum of performance-enhancing practices [15,44,45]. This inclusive approach enables the examination of common psychological mechanisms, while recognizing that the severity, motivations, and consequences of such behaviors differ across categories. Furthermore, the present study seeks to expand existing conceptualizations of CAPE behaviors. Previous research has treated CAPE behaviors as the end of the psychological process primarily focusing on identifying their determinants. Although some scholars argue that CAPE behaviors should not be viewed as end states but rather as part of a broader process that helps individuals achieve their ultimate goals [37,40,41], there is still a lack of systematic evidence and a solid conceptualization of this process. This study aims to preliminarily investigate this hypothesis based on the Goal Systems Theory [43].

Based on existing evidence, we formulated the following hypotheses:

H1.

Individual traits (i.e., perfectionism, cultural values, self-determination, group identification and orientation, distal norms, and past behavior) will be associated with proximal correlates of CAPE behaviors (i.e., attitudes, proximal norms, perceived behavioral control, and situational temptation) [32].

H2.

Proximal correlates of CAPE behaviors will be associated with intentions toward adopting CAPE behaviors and means [32,46].

H3.

Drawing from Goal Systems Theory, goal commitment and goal difficulty will be associated with the use of means [40,41,43].

H4.

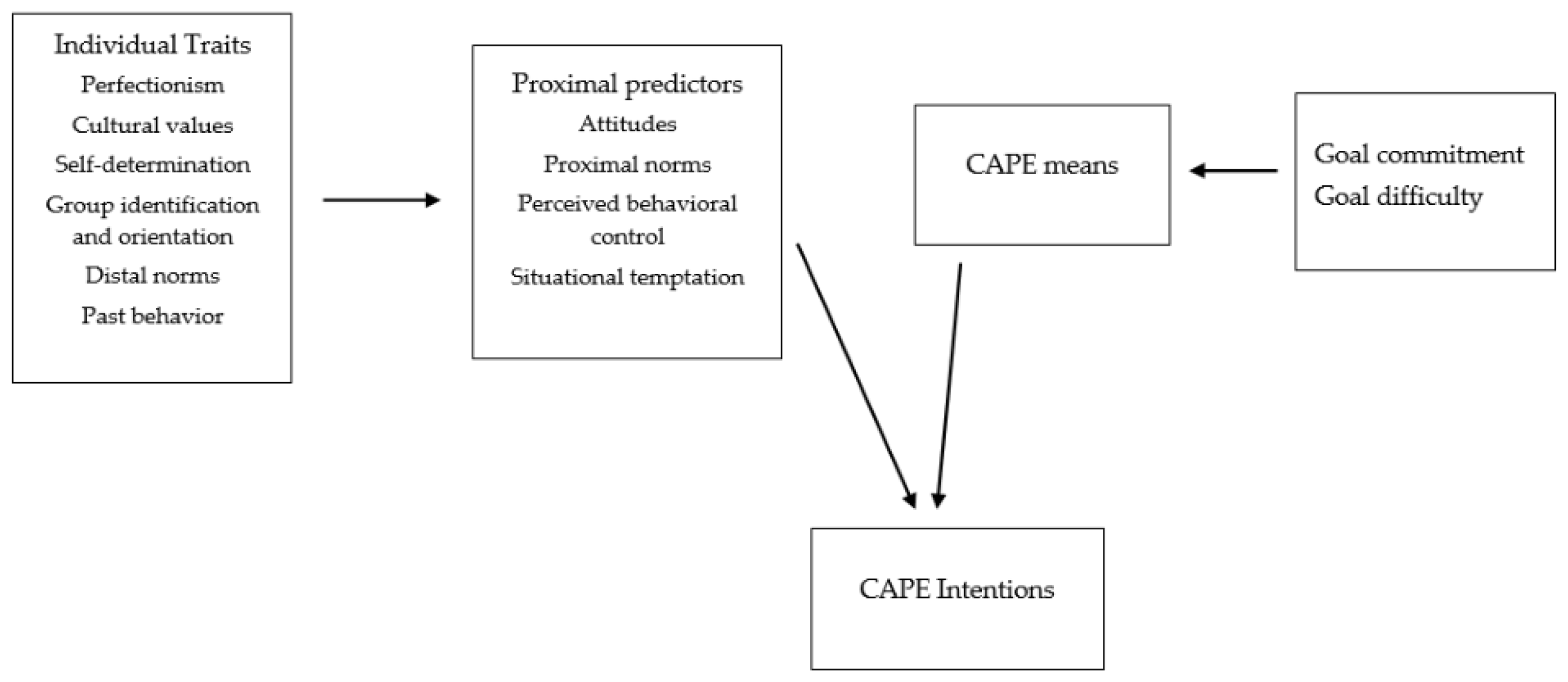

The use of means will, in turn, be associated with intentions toward CAPE behaviors [37,43] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed conceptual framework of CAPE behaviors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were 254 individuals from Greece (Mage = 28.92, SD = 10.85; 113 males). Of these, 64 were competitive athletes (Mage = 19.92, SD = 3.50; 30 males), 40 were recreational exercisers (Mage = 25.60, SD = 11.49; 10 males), 67 were students (Mage = 25.48, SD = 8.98; 22 males), and 83 were professionals (Mage = 44.71, SD = 11.12; 51 males).

The inclusion criteria for each subgroup were informed by previous literature [7] and adapted to the aims of the present study. Participants were categorized as competitive or recreational based on their self-reported level of organized sport involvement. Competitive athletes were defined as individuals who regularly participated in officially sanctioned competitions and followed a structured training program guided by a coach or club. Recreational exercisers referred to individuals who engaged in exercise or sport primarily for leisure, fitness, or personal enjoyment, without systematic participation in competitions. Both groups were required to train systematically for at least three times per week. Students were recruited from faculties with high academic workload (e.g., medicine, engineering) [8]. Professionals considered at risk for CAPE behaviors (e.g., academics, policy makers, army officers) [5] were also targeted.

Recruitment was conducted online through social media announcements, mailing lists of universities and professional institutions, and posts in regional sport clubs and gyms. The final sample size was comparable to previous studies in the field and considered adequate for path analysis [47].

2.2. Measures

Means to achieve goals: Participants rated on a 7-point scale the frequency through which they used six means (e.g., proper training, proper diet and nutrition, good sleep, nutritional supplements, performance enhancement substances (PES), etc., in order to achieve their ultimate goal.

Goal commitment and goal difficulty: One item was used to assess goal commitment (“Doing good at ‘work/study/sport/exercise is important to me”) with responses anchored on 10-point scale from 0 (Not important at all) to 100 (Extremely important). One item was used to measure goal difficulty (“Succeeding at ‘work/study/sport/exercise’ is difficult”) rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (Do not agree at all) to 7 (Extremely agree).

PES intentions: Intentions to use PES was measured via six items following the stem question I would use a PED if… (e.g., “…my performance was lower than I expected”). Responses are given on a 7-point Likert-type scale from “strongly agree” (7) to “strongly disagree” (1).

PES behavior: One item was used to measure past PES behavior (“Have you ever used PES to enhance your performance?”). Four different response options were provided (1 = no, I have never used PES; 2 = yes, I once used PES to enhance my performance, but not ever since; 3 = yes, I occasionally use PES to enhance my performance; and 4 = yes, I systematically use PES to enhance my performance).

Perfectionism: The High Standards subscale of The Greek version of the Almost Perfect Scale-Revised (APS-R) [48] was used to measure perfectionism. The subscale includes 7 items (e.g., I expect the best from myself) assessing the high standards one sets for oneself and it is scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Group-identification and orientation: Three items adjusted from Norman et al. [49] were used to assess self-identity (e.g., “I have a strong identity with my coworkers/teammates/co-exercisers”). Responses were anchored on a 7-point Likert scale, 1 (strongly disagree/not at all), 7 (strongly agree/very much). Group orientation was assessed via two items (e.g., “It is important to me to be in harmony with people in my work/school/team/gym”) [50] with responses coded on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Values: The Gelfand et al. [51] scale was used to measure cultural values through six items (e.g., ‘There are many social norms that people are supposed to abide by in my country’). Responses were provided on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree).

Self-determination: The Self-Regulation Questionnaire was used to assess self-determination. The scales included 15 items measuring intrinsic motivation (e.g., ‘For the pleasure of discovering and mastering new training techniques’), identified regulation (e.g., ‘Because I have a strong value for being active and healthy’), introjected regulation (e.g., ‘Because I feel pressured to work out’), and external regulation (e.g., ‘Because I want others to see me as physically fit’). The items were appropriately adjusted for each life domain. Participants responded on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from not at all true (1) to very true (7).

Motivation to comply: A single item was used to assess motivation to comply (“When it comes to matters of performance enhancement, I want to do what people important to me approve”). The response options ranged from completely disagree (1) to completely agree (7).

Knowledge: PES knowledge was measured with four items (e.g., ‘How often have you looked up for information about PES from an expert?’) and participants responding on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very often).

Perceived behavioral control: Two items were used to assess perceived behavioral control (e.g., “I feel in complete control over whether I will use PES to enhance my performance during this season”) measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (no control) to 7 (complete control).

Subjective norms: Distal-level subjective norms were measured with two items (e.g., ‘Do you think that the society approves of PES use in work/sports/school/gym’). Proximal-level subjective norms were measured with 6 items (e.g., Do your coworkers/classmates/teammates/co-exercisers approve of substance use for performance-enhancement reasons?’). Responses to these items were assessed on 7-point Likert scales (e.g., 1 = strongly disagree/definitely not/never, 7 = strongly agree/definitely yes/very frequently).

Descriptive norms: Distal level descriptive norms were measured with two items. The first item assessed the use of CAPE by professionals in other work environments/students from other departments/athletes from other sports/exercisers in other exercise settings (e.g., “How many athletes in the same competitive level as you do you believe that use substances to improve their performance?), scored on a 7-point scale from 1 (nobody) to 7 (everyone). The second item assessed the perceived percentage of CAPE used by athletes/exercisers/professionals/students (e.g., ‘Out of 100%, how many athletes/exercisers/professionals/students in your country do you think engage in substance use to enhance their performance?’). Responses ranged from 0 to 100%. Proximal-level descriptive norms were assessed with one item (e.g., How many of your coworkers/classmates/teammates/co-exercisers do you think engage in PES use to enhance their performance’). Also, items about social-moral atmosphere (e.g., ‘How many of your coworkers/classmates/teammates/co-exercisers would engage in PES use, if it was necessary for them to enhance their performance?’) [52]) were used as an additional measure of proximal descriptive norms. Lastly, the frequency of exposure to PES incidents was assessed with two items (e.g., ‘In the last year, how often have you heard about exercisers/athletes/students/professionals engaging in PES use’). In all these items participants responded on a 7-point continuous scale (1 = lower end, 7 = higher end).

Attitudes: Attitudes were measured with eight 7-point bipolar adjectives (e.g., bad-good, harmful-beneficial, ethical-unethical, and useful-useless): following the stem question “The use of PES to enhance my performance during this season is…”

Situational temptation: Efficacy to resist temptation to use PES was assessed with the question “How sure you are that you would be able to resist temptation to use performance enhancement substances if…” followed by seven items (e.g., ‘My performance was much worse than expected”). Responses were anchored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all tempted, 5 = very much).

2.3. Procedure

The study received approval from the respective committee of the authors’ university. The study aims and survey were communicated to stakeholders (i.e., club directors and coaches, gym owners and instructors, rector and dean authorities, police and army officials) in order to obtain permission to distribute the survey. Four online surveys were developed, one for each life domain. Following obtaining approval, the links to the online survey were sent to participants. The link included a sheet providing information on the aims and objectives of the study, the anonymity, the confidentiality of their responses, the use of their response for research purposes solely, GDPR guidelines and contact persons. Following the information sheet participants were presented with an informed consent form. Only participants providing inform consent took part in the study.

2.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients were performed with SPSS version 25.0. The study’s hypotheses were tested via path analysis. Due to the complexity of the model, the large number of measures and items that would increase the number of parameters tested and would require a large sample size, a path analysis was preferred over SEM. The path analysis was performed with MPLUS 8.11 software. The goodness of fit of the proposed model with the data was evaluated through incremental and absolute fit indices. In particular, χ2 was used as the main incremental index. Due to the fact that χ2 is heavily influenced by sample size, absolute fit indices were also used. More specifically, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and the Standardized Root Mean Squared residual (SRMR) were used to estimate the fit of the model to the data. Based on existing recommendations, CFI scores close or above 0.95 were considered as demonstrating adequate fit. In addition, RMSEA and SRMR scores lower than 0.08 were considered as indicators of satisfactory model fit [53].

3. Results

Descriptive statistics and analysis of correlation are presented in Table 1. Correlation analyses revealed systematic patterns consistent with the proposed framework. Intentions to engage in CAPE behaviors were strongly associated with attitudes (r = 0.68, p < 0.001) and proximal subjective norms (r = 0.50, p < 0.001), and negatively associated with situational temptation (r = −0.47, p < 0.001). Intentions were also correlated with the means of performance enhancement (r = 0.40, p < 0.001), the combined means of training/work/study with nutritional supplements (r = 0.30, p < 0.001), and the combined means of training/work/study with PES (r = 0.35, p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the study variables.

At the distal level, attitudes correlated with knowledge (r = 0.20, p < 0.001), past behavior (r = 0.38, p < 0.001), distal subjective norms (r = 0.34, p < 0.001), distal descriptive norms (r = 0.28, p < 0.001), and autonomous motivation (r = 0.17, p < 0.001), and were negatively associated with control motivation (r = −0.17, p < 0.001). Proximal subjective norms showed strong correlations with knowledge (r = 0.24, p < 0.001), past behavior (r = 0.47, p < 0.001), motivation to comply (r = 0.62, p < 0.001), distal subjective norms (r = 0.41, p < 0.0001), distal descriptive norms (r = 0.48, p < 0.001), and autonomous motivation (r = 0.19, p < 0.001). Proximal descriptive norms were associated with knowledge (r = 0.34, p < 0.001), past behavior (r = 0.21, p < 0.001), motivation to comply (r = 0.35, p < 0.001), distal subjective norms (r = 0.17, p < 0.001), and distal descriptive norms (r = 0.39, p < 0.001).

Situational temptation was negatively associated with past behavior (r = −0.22, p < 0.001) and motivation to comply (r = −0.27, p < 0.001), and positively associated with control motivation (r = 0.19, p < 0.001). PBC was correlated only with distal subjective norms (r = 0.18, p < 0.001).

Finally, goal commitment was positively associated with the combined means of training/work/study and nutritional supplements (r = 0.25, p < 0.001) and the combined means of training/work/study and PES (r = 0.35, p < 0.001), and negatively associated with the means of performance enhancement (r = −0.38, p < 0.001).

The results of the path analysis showed an adequate fit model with the data [χ2 (129) = 204.953, p = 0.000; CFI = 0.941; SRMR = 0.050; RMSEA = 0.054, RMSEA CI90 lower limit = 0.040, RMSEA CI90 upper limit = 0.068].

With respect to the first hypothesis, results showed that the first distal subjective norms item (acceptance of CAPE by the general public) (β = 0.170, p < 0.05), proximal subjective norms (β = 0.544, p < 0.01) and past behavior (β = 0.168, p < 0.05) were positively associated with attitudes. Group identification, knowledge, cultural values, perfectionism and proximal descriptive norms were not associated with attitudes. With respect to perceived behavioral control, the results indicated that it was not associated with none of the studied variables (perfectionism, controlling and autonomous motivation, means of using PES and means of combining work/study/training and PES and past behavior). Controlling motivation (β = 0.166, p < 0.05) and past behavior (β = −0.201, p < 0.01) were positively and negatively associated with situational temptation, respectively, while perfectionism had a marginally insignificant negative association (β = −0.130, p = 0.052). Autonomous motivation was not significantly associated with situational temptation. With respect to proximal subjective norms, it was found to be associated with group identification (β = −0.112, p < 0.05), group orientation (β = −0.118, p < 0.05) and the second distal descriptive norms item (β = −0.130, p < 0.05). Motivation to comply (β = 0.392, p = 0.000), the first distal subjective norms item (acceptance of CAPE by the general public) (β = 0.206, p = 0.000), the second distal descriptive norms item (use by professionals in other work environments/students from other departments/athletes from other sports/exercisers in other exercise settings) (β = 0.189, p < 0.01) and past behavior (β = 0.251, p = 0.000) were positively associated with proximal subjective norms. Finally, group identification (β = 0.158, p < 0.05), motivation to comply (β = 0.168, p < 0.05), both distal descriptive norms (β = 0.184, p < 0.015 and β = 0.172, p < 0.05) and past behavior were positively associated with proximal descriptive norms, whereas cultural values were negatively associated (β = −0.131, p < 0.05). In contrast, group orientation and both distal subjective norms did not show significant associations with proximal descriptive norms (Table 2).

Table 2.

Standardized associations between distal and proximal variables related to CAPE behaviors (H1).

Regarding the second hypothesis that the proximal correlates of CAPE behaviors would be associated with intentions towards adopting CAPE behaviors and means, the results indicated that attitudes (β = 0.497, p = 0.000) and past behavior (β = 0.192, p = 0.001) were positively associated with intention to use PES, while situational temptation was negatively associated with intention to use PES (β = −0.224, p = 0.000). Perceived behavioral control, proximal subjective norms, proximal descriptive norms, goal commitment and goal difficulty were not significantly associated with intentions. With respect to the means of training/working/studying, the results indicated a negative association with proximal subjective norms (β = −0.244, p < 0.01), while attitudes, situational temptation, perceived behavioral control, and proximal descriptive norm, were not significantly related with these means. Regarding the means of using nutritional supplements, results revealed they were negatively associated with proximal subjective norms (β = −0.255, p = 0.010), while a positive association was found with descriptive norms (β = 0.263, p < 0.01). Attitudes, temptation and perceived behavioral control were not significantly related with the means of using nutritional supplements. Lastly, attitudes, temptation, perceived behavioral control, subjective norms and descriptive norms were not significantly related with the means of using substances, the means of combining training/work/study and use of nutritional supplements, the means of combining training/work/study and use of PES, as well as means of combining PES and nutritional supplement use (Table 3).

Table 3.

Standardized scores of proximal correlates of intentions and means of CAPE behaviors (H2).

Concerning the third hypothesis that goal commitment and goal difficulty will be associated with means of performance enhancement, the results showed that goal difficulty was not significantly associated with any of the means (training/working/studying, using nutritional supplements, using substances, combining training/work/study and use of nutritional supplements, combining training/work/study and use of PES and combining PES and nutritional supplement use), while goal commitment (β = 0.258, p = 0.000) was positively associated with only the means of training/work/study.

With respect to the fourth hypothesis, it was found that PES as a means (β = 0.208, p < 0.05), was positively associated with intention to use PES. On the contrary, all other means, were not significantly related to intentions.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated a common conceptual framework for the understanding of CAPE behaviors in four different life domains. The results of the path analysis partially supported our hypotheses. Attitudes and situational temptation were associated with intentions to adopt CAPE behaviors, whereas perceived behavioral control and norms were not. Goal commitment was associated with the mean of working/studying/training but no other means. In addition, norms were associated with the means of using nutritional supplements. With respect to the associations between distal variables and proximal correlates of intentions, distal norms and past behavior were associated with attitudes, controlling motivation and past behavior was associated with situational temptation. Furthermore, cultural values, group identification, group orientation and distal descriptive norms, motivation to comply distal subjective norms and past behavior were associated with proximal norms.

The results of the study confirmed the association of distal variables with proximal correlates of intentions. Importantly, attitudes, social norms and situational temptation were the proximal correlates that were mostly associated with the distal variables. This finding highlights the important role these variables can play in the decision-making process [32,33]. The normative and cultural environment was most strongly related to these proximal variables. This finding signifies that CAPE behaviors are closely associated with the extent to which such behaviors are perceived as acceptable. In this case, a competitive mentality in achieving tangible outcomes and a broader mentality of improvement at all costs are linked to a dopogenic environment that increases the chances for CAPE behaviors. This was further corroborated by the observed association with controlling motivation, a type of motivation focusing on achieving rewards [42].

Attitudes and situational temptation emerged showed the strongest associations with CAPE behaviors intentions. This is in line with previous research [32,33,54] suggesting them as important variables in the decision-making process. These findings signify that individuals expecting positive outcomes from use or hold a positive view about substance use form stronger intentions towards use. Similarly, individuals who cannot resist the temptation to use these substances in order to achieve their goals have also higher intentions from use. Interestingly, perceived behavioral control that had been reported as important mediator in this process [32,33] was not significantly related to distal variables. This finding highlights an important trans-contextual mechanism. That is, perceived behavioral control may appears more relevant in competitive sport where the availability of prohibited substances and the potential sanctions are salients factors shaping the decision to use them. However, this may not be a barrier in work and studentship where PES are easily accessible and there are no restrictions in use. Accordingly, norms did not show significant associations, in contrast to previous evidence [55]. In this line, norms may be an important barrier for doping in sport due to the fact that it is considered unethical behavior [56]. However, in other life domains, such as exercise, work or studentship there may be no ethical concerns about the use of PES, and thus, norms may be less strongly related to substance use.

An important addition to the existing models of CAPE behaviors was the integration of aspects of the Goal System Theory [43]. More specifically we investigated the associations between proximal correlates of CAPE behavior on the means that individuals may use to achieve their objectives as well as the associations between these means and the intention for future CAPE behaviors. The results of the analysis indicated that using PES as means to achieve was positively associated with stronger intentions. This finding signifies a maladaptive reasoning suggesting that individuals considering PES use as a potential way to achieve are more susceptible in using such behaviors in the future. This evidence corroborates Barkoukis et al. [57] who advocated that a maladaptive mentality and biased reasoning results in favorable intentions towards CAPE behaviors. Interestingly, a mixed pattern was found on the association of norms with means. The means of working/studying/training was positively associated with subjective norms and negatively by descriptive norms. In addition, the means of using nutritional supplements was negatively associated with subjective norms and positively with descriptive norms. No clear explanations can be provided for these mixed findings. Clearly, more research is warranted to understand how norms relate to beliefs about effective means and reasoning for their use.

In interpreting these findings, it is important to acknowledge the substantial variability observed across participants. As shown in the descriptive data (Table 1), several variables, including intentions, temptation, and distal descriptive norms, displayed wide standard deviations, indicating that CAPE-related beliefs and tendencies were far from homogeneous. This heterogeneity carries theoretical significance, suggesting that individuals may differ not only in the strength but also in the configuration of their motivational and normative profiles. For example, some participants may experience strong temptation but weak intentions, whereas others may hold favorable attitudes or perceive permissive norms without necessarily engaging in use. Recognizing these distinct constellations of CAPE-related cognitions highlights the potential for person-centered approaches, such as cluster or latent-profile analyses, that could identify meaningful subgroups and refine the current framework by accounting for individual differences in vulnerability and goal regulation.

The study is not free of limitations. Firstly, its cross-sectional design and reliance on self-reported data preclude any causal inferences. Consequently, all findings describe associations rather than effects. In this respect, alternative explanations should be acknowledged. For instance, individuals with stronger CAPE intentions or previous experience with performance enhancement may retrospectively adjust their attitudes and perceptions of norms to justify their behavior. Likewise, cultural and social influences may not only shape but also be shaped by individual engagement in CAPE-related activities. To evolve into a fully testable theory, future research should generate and examine falsifiable hypotheses regarding the proposed causal pathways and their potential boundary conditions. Evidence inconsistent with these predictions, such as the reverse influence of intentions on attitudes or norms, would help refine or challenge the framework, advancing it from a conceptual to a predictive model. Future studies could employ longitudinal designs to establish the temporal ordering of variables and clarify potential feedback loops among distal, proximal, and behavioral components. Experimental or intervention-based approaches could further examine directionality by manipulating specific variables (e.g., attitudes, temptation, or normative perceptions) to test their effects on CAPE intentions or behaviors. Additionally, qualitative approaches could help unpack contextual meanings, providing insight into how individuals interpret sociocultural influences, motivational conflicts, and goal hierarchies underlying CAPE decisions. Also, the analytic approach presents limitations. The use of path analysis is ambitious given the modest overall sample size and the subgroup splits across four life domains. These conditions may increase the risk of overfitting and lead to unstable parameter estimates. Moreover, the use of path analysis without error estimation further limits the robustness of the conclusions. Future studies with larger and more balanced samples should employ structural equation modeling (SEM) to validate the model, account for measurement error, and confirm the stability of the observed associations. In addition, the small sample size in each life domain did not allow meaningful group comparisons. Future studies should include larger samples in each life domain and investigate via multigroup analyses the common and different paths across the domains. Lastly, our operationalization of CAPE encompassed substances of very different legal status and risk profiles. While dietary supplements and over-the-counter products are legally accessible, the use of anabolic steroids constitutes a controlled and more hazardous behavior. Future studies should examine these categories separately to disentangle common from substance-specific predictors.

5. Conclusions

The study findings provide preliminary evidence of a new conceptualization of CAPE behavior. Distal sociocultural and motivational variables are associated with proximal cognitive correlates of intentions and various means toward achieving higher-order goals. This is the first study to provide a conceptual framework and identify common correlates of CAPE behavior intentions across different life domains. In addition, it extends previous conceptualizations of CAPE behaviors by acknowledging that intentions are also influenced by the means that are available and that these means may guide behavior towards the attainment of a higher goal. The findings of the present study can provide the basis for the development of a common theoretical understanding of CAPE behavior (see Figure 1) and accordingly develop effective interventions to help people achieve informed decisions about the ways they can use to achieve their goals. The present findings carry several practical implications for educational, occupational, and sport settings. Understanding the sociocultural and motivational factors associated with CAPE behaviors can inform the development of prevention and education programs that address both individual and contextual influences. In applied contexts, coaches, educators, and health professionals can play a pivotal role in shaping ethical norms and promoting non-chemical pathways to achievement by encouraging self-regulation, adaptive goal pursuit, and critical reflection on social pressures for performance. Interventions based on this framework may emphasize informed decision-making and psychological well-being rather than performance outcomes alone.

Taken together, the findings indicate that a set of factors, namely motivation to comply, group identification, distal descriptive and subjective norms, and past behavior, play a key role in shaping the proximal cognitive processes associated with CAPE. Through their influence on attitudes, proximal norms, and situational temptation, these variables contribute to the formation of CAPE intentions. In addition, goal commitment and the use of PES as a means further strengthen this pathway. Overall, these significant factors form an empirically grounded model that can meaningfully enhance our understanding of how CAPE behaviors develop.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.B. and H.T.; methodology, L.S., D.O., V.B. and H.T.; software, V.B. and L.S.; validation, V.B. and H.T. formal analysis, V.B. and L.S.; investigation, D.O. and L.S.; resources, L.S. and D.O.; data curation, V.B. and H.T.; writing—original draft preparation, L.S., D.O. and V.B.; writing—review and editing, L.S., D.O., H.T. and V.B.; visualization, L.S. and D.O.; supervision, H.T. and V.B.; project administration, H.T.; funding acquisition, H.T., V.B., L.S. and D.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is co-financed by Greece and the European Union (European Social Fund—ESF) through the Operational Programme “Human Resources Development, Education and Lifelong Learning 2014–2020” in the context of the project “A longitudinal investigation of Chemically Assisted Performance Enhancement in four life domains” (MIS 5047945). This publication reflects the views only of the author, and the funding organization cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Physical Education and Sport Science at Thessaloniki (21/2021, 29 April 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions related to participant confidentiality. Data may be made available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CAPE | Chemically Assisted Performance Enhancement |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

| IMBP | Integrative Model of Behavioral Prediction |

| PES | Performance Enhancement Substances |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Squared |

References

- Daubner, J.; Arshaad, M.I.; Henseler, C.; Hescheler, J.; Ehninger, D.; Broich, K.; Weiergräber, M. Pharmacological neuroenhancement: Current aspects of categorization, epidemiology, pharmacology, drug development, ethics, and future perspectives. Neural Plast. 2021, 2021, 8823383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVeigh, J.; Evans-Brown, M.; Bellis, M.A. Human Enhancement Drugs: The Emerging Challenges to Public Health; North West Public Health Observatory: Liverpool, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Baume, N.; Hellemans, L.; Saugy, M. Guide to over-the-counter sports supplements for athletes. Int. Sport Med. J. 2007, 8, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- de Hon, O.; Kuipers, H.; van Bottenburg, M. Prevalence of doping use in elite sports: A review of numbers and methods. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, I.; Pattinson, E.; Leyland, S.; Soos, I.; Ling, J. Performance and image enhancing drugs use in active military personnel and veterans: A contemporary review. Transl. Sports Med. 2021, 4, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolding, G.; Sherr, L.; Elford, J. Use of anabolic steroids and associated health risks among gay men attending London gyms. Addiction 2002, 97, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazuras, L.; Barkoukis, V.; Loukovitis, A.; Brand, R.; Hudson, A.; Mallia, L.; Zelli, A. “I want it all, and I want it now”: Lifetime prevalence and reasons for using and abstaining from controlled performance and appearance enhancing substances among young exercisers and amateur athletes in five European countries. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietz, P.; Soyka, M.; Franke, A.G. Pharmacological neuroenhancement in the field of economics—Poll results from an online survey. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, S.; Guirguis, A.; Fergus, S.; Schifano, F. The use and impact of cognitive enhancers among university students: A systematic review. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.; Pope, H.G.; Cléret, L.; Petróczi, A.; Nepusz, T.; Schaffer, J.; Kanayama, G.; Comstock, R.D.; Simon, P. Doping in two elite athletics competitions assessed by randomized-response surveys. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojsen-Møller, J.; Christiansen, A.V. Use of performance- and image-enhancing substances among recreational athletes: A quantitative analysis of inquiries submitted to the Danish anti-doping authorities. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2010, 20, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ne’eman-Haviv, V.; Bonny-Noach, H.; Berkovitz, R.; Arieli, M. Attitudes, knowledge, and consumption of anabolic-androgenic steroids by recreational gym goers in Israel. Sport Soc. 2020, 23, 1864–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdős, Á. Cops and drugs: Illicit drug abuse by police personnel. Belügyi Szle. 2022, 70, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoberman, J. Police officers’ use of anabolic steroids in the United States. In Routledge Handbook of Drugs and Sport; Waddington, I., Smith, A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 291–301. [Google Scholar]

- Knapik, J.J.; Trone, D.W.; Austin, K.G.; Steelman, R.A.; Farina, E.K.; Lieberman, H.R. Prevalence, adverse events, and factors associated with dietary supplement and nutritional supplement use by US Navy and Marine Corps personnel. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1423–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Cocimano, G.; Ministrieri, F.; Rosi, G.L.; Di Nunno, N.; Messina, G.; Salerno, M. Smart drugs and neuroenhancement: What do we know? Front. Biosci.-Landmark 2021, 26, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSantis, A.D.; Noar, S.M.; Webb, E.M. Nonmedical ADHD stimulant use in fraternities. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2009, 70, 952–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franke, A.G.; Bagusat, C.; Dietz, P.; Hoffmann, I.; Simon, P.; Ulrich, R.; Lieb, K. Use of illicit and prescription drugs for cognitive or mood enhancement among surgeons. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, S.E.; Knight, J.R.; Teter, C.J.; Wechsler, H. Non-medical use of prescription stimulants among US college students: Prevalence and correlates from a national survey. Addiction 2005, 100, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thier, R.; Gresser, U. Methylphenidate misuse in adults: Survey of 414 primary care physicians in Germany and comparison with the literature. J. Behav. Brain Sci. 2017, 7, 180–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, W.; Brand, R.; Baumgarten, F.; Lösel, J.; Ziegler, M. Modeling students’ instrumental (mis-)use of substances to enhance cognitive performance: Neuroenhancement in the light of job demands–resources theory. BioPsychoSoc. Med. 2014, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahverdipour, H.; Jalilian, F.; Shaghaghi, A. Vulnerability and the intention to anabolic steroids use among Iranian gym users: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Subst. Use Misuse 2012, 47, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blank, C.; Kopp, M.; Niedermeier, M.; Schnitzer, M.; Schobersberger, W. Predictors of doping intentions, susceptibility, and behaviour of elite athletes: A meta-analytic review. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntoumanis, N.; Dølven, S.; Barkoukis, V.; Boardley, I.D.; Hvidemose, J.S.; Juhl, C.B.; Gucciardi, D.F. Psychosocial predictors of doping intentions and use in sport and exercise: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2024, 58, 1145–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, R.; Koch, H. Using caffeine pills for performance enhancement: An experimental study on university students’ willingness and intention to try neuroenhancements. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, R.; Wolff, W.; Ziegler, M. Drugs as instruments: Describing and testing a behavioral approach to the study of neuroenhancement. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweighart, R.; Kruck, S.; Blanz, M. Taking drugs for exams: An investigation with social work students. Soc. Work Educ. 2020, 39, 1131–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazuras, L.; Ypsilanti, A.; Lambrou, E.; Kontogiorgis, C. Pharmaceutical cognitive enhancement in Greek university students: Differences between users and non-users in social cognitive variables, burnout, and engagement. Subst. Use Misuse 2017, 52, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Galli, F.; Chirico, A.; Mallia, L.; Alivernini, F.; Manganelli, S.; Zelli, A.; Lucidi, F. Identifying determinants of neuro-enhancement substance use in students. Eur. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 29, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M. An integrative model for behavioral prediction and its application to health promotion. In Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research, 2nd ed.; DiClemente, R.J., Crosby, R.A., Kegler, M.C., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 215–234. [Google Scholar]

- Barkoukis, V.; Lazuras, L.; Tsorbatzoudis, H.; Rodafinos, A. Motivational and social cognitive predictors of doping intentions in elite sports: An integrated approach. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2013, 23, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazuras, L.; Barkoukis, V.; Tsorbatzoudis, H. Toward an integrative model of doping use: An empirical study with adolescent athletes. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2015, 37, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelli, A.; Lucidi, F.; Mallia, L. The complexity of neuroenhancement and the adoption of a social cognitive perspective. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagoe, D.; Molde, H.; Andreassen, C.S.; Torsheim, T.; Pallesen, S. The global epidemiology of anabolic–androgenic steroid use: A meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. Ann. Epidemiol. 2014, 24, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallia, L.; Lazuras, L.; Barkoukis, V.; Lucidi, F. Doping attitudes and the use of legal and illegal performance-enhancing substances among Italian adolescents. J. Child Adolesc. Subst. Abus. 2013, 22, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, W.; Brand, R. Subjective stressors in school and their relation to neuroenhancement: A behavioral perspective on students’ everyday life “doping”. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2013, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, P.; Ho, H.; Sykes, G.; Szekely, P.; Dommett, E.J. Learning approaches and attitudes toward cognitive enhancers in UK university students. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2020, 52, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champagne-Jorgensen, K.; Kunze, W.A.; Forsythe, P.; Bienenstock, J.; Neufeld, K.A.M. Antibiotics and the nervous system: More than just the microbes? Brain Behav. Immun. 2019, 77, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petróczi, A. The doping mindset—Part I: Implications of the functional use theory on mental representations of doping. Perform. Enhanc. Health 2013, 2, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsorbatzoudis, H.; Lazuras, L.; Barkoukis, V. Next steps in doping research and prevention. In The Psychology of Doping in Sport; Barkoukis, V., Lazuras, L., Tsorbatzoudis, H., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 230–243. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Brick by brick: The origins, development, and future of self-determination theory. In Advances in Motivation Science; Elliot, A.J., Ed.; Elsevier: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; Volume 6, pp. 111–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglanski, A.W.; Shah, J.Y.; Fishbach, A.; Friedman, R.; Chun, W.Y.; Sleeth-Keppler, D. A theory of goal systems. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 34, 331–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVeigh, J.; Begley, E. Anabolic steroids in the UK: An increasing issue for public health. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2017, 24, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, T.; Roberts, K. Motives for Illicit Prescription Drug Use among University Students. Addict. Behav. 2017, 65, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D.J.; Mallinson-Howard, S.H.; Grugan, M.C.; Hill, A.P. Perfectionism and attitudes towards doping in athletes: A continuously cumulating meta-analysis and test of the 2 × 2 model. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2020, 20, 1245–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulou, G.; Platsidou, M. Factorial validity and psychometric properties of the Greek version of the Almost Perfect Scale-Revised (APS-R). Hell. J. Psychol. 2014, 11, 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, P.; Clark, R.; Walker, G. The theory of planned behavior, descriptive norms, and the moderating role of group identification. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 35, 1008–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapinski, M.K.; Rimal, R.N.; DeVries, R.; Lee, E.L. The role of group orientation and descriptive norms on water conservation attitudes and behaviors. Health Commun. 2007, 22, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelfand, M.J.; Raver, J.L.; Nishii, L.; Leslie, L.M.; Lun, J.; Lim, B.C.; Duan, L.; Almaliach, A.; Ang, S.; Arnadottir, J.; et al. Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study. Science 2011, 332, 1100–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ommundsen, Y.; Roberts, G.C.; Lemyre, P.N.; Treasure, D. Perceived motivational climate in male youth soccer: Relations to social–moral functioning, sportspersonship and team norm perceptions. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2003, 4, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallia, L.; Lucidi, F.; Zelli, A.; Violani, C. Doping attitudes and the use of legal and illegal performance-enhancing substances among Italian adolescents: The moderating role of self-regulation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2017, 30, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, P.; Ng, P.Y.; Under, L.; Fuggle, C. Dietary supplement use is related to doping intention via doping attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control. Perform. Enhanc. Health 2024, 12, 100278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkoukis, V.; Elbe, A.M. Moral behavior and doping. In Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology: Research Directions to Advance the Field; Filho, E., Basevitch, I., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 308–322. [Google Scholar]

- Barkoukis, V.; Lazuras, L.; Lucidi, F.; Tsorbatzoudis, H. Nutritional supplement and doping use in sport: Possible underlying social cognitive processes. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2015, 25, e582–e588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).