Youth Soccer Development After a Forced Training Interruption: A Retrospective Analysis of Prepubertal Players

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Assessments and Procedures

- Anthropometric measurements were collected before the physical tests in a dedicated room within the club facilities, where players entered individually to be measured under standardised conditions. Body mass was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a Rowenta BS1060 scale (Offenbach am Main, Germany), with players wearing training apparel but without shoes or shin guards. Standing height was measured with a wall-mounted stadiometer with a precision of 0.01 m and a range of 60–210 cm (Lanzoni D01602H, Bologna, Italy). Body mass index (BMI) was then calculated as weight divided by height squared (kg/m2) using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet.

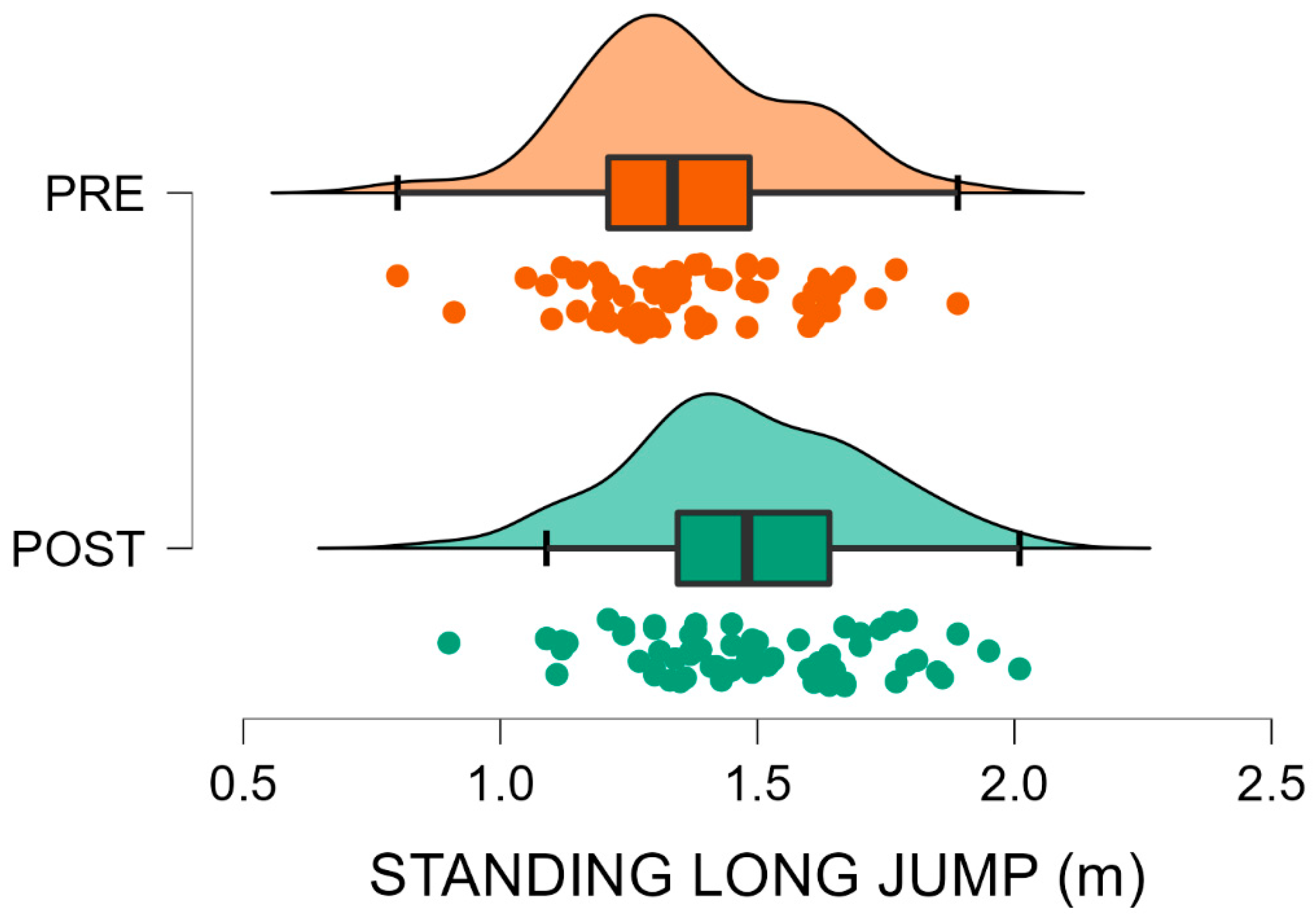

- Standing Long Jump (SLJ): assessed lower-limb explosive power. Players stood with both feet behind a marked take-off line and performed a two-footed jump as far forward as possible. Each participant completed three attempts, and the best performance was retained for analysis. The jump distance was measured from the take-off line to the nearest point of landing, typically the heels, by projecting a straight line backwards from the athlete’s heels to the take-off line (Figure 1).

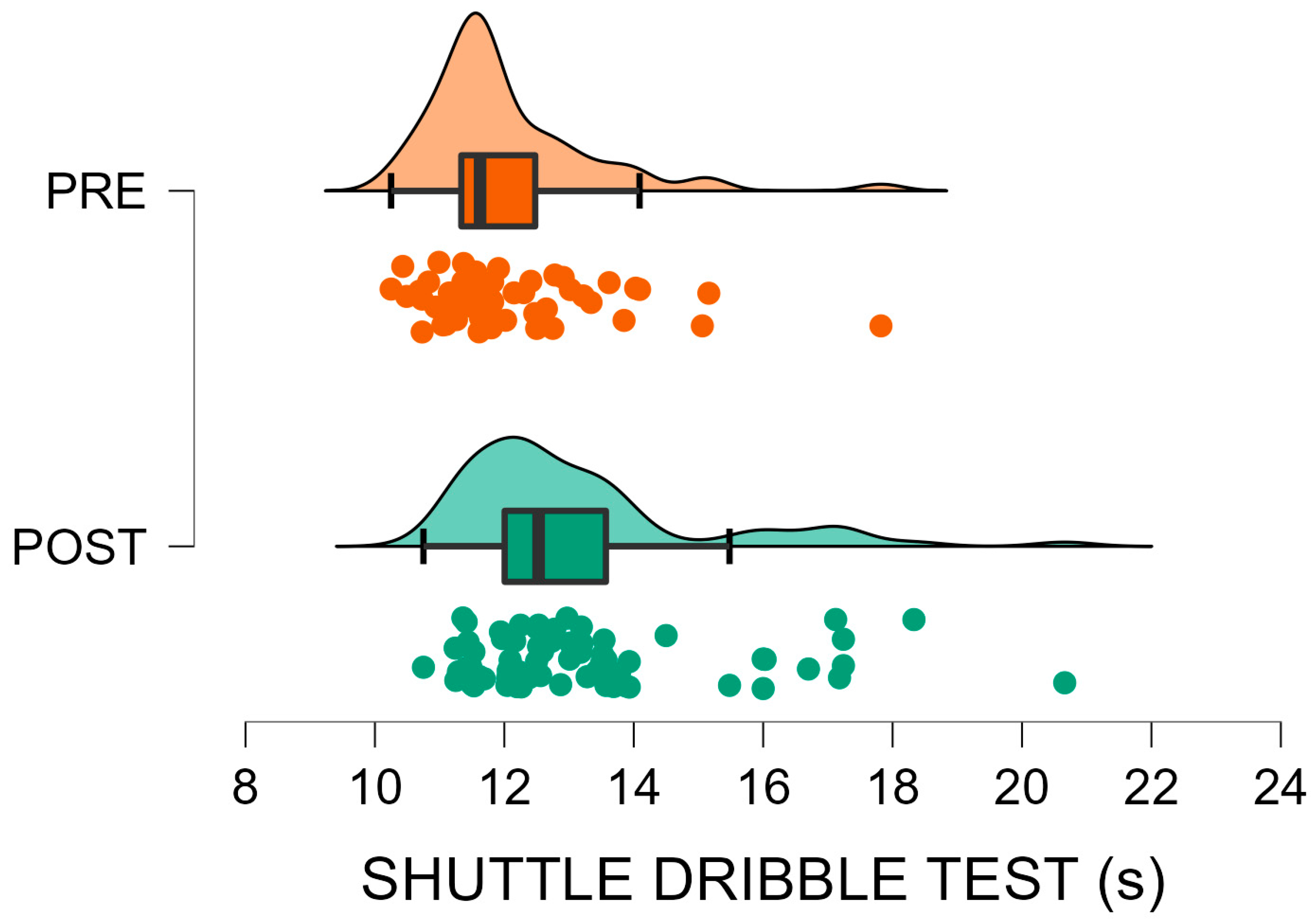

- Shuttle Dribble Test: assessed technical-agility performance. Players completed a shuttle run while leading the ball, performing 180° changes of direction at 5, 6, 9, and 10 m within a 2 m lane. As described by Huijgen et al. [24], players dribbled 5 m, executed a 180° change of direction, dribbled 6 m back toward the start, performed another 180° change of direction, dribbled 10 m, executed a 180° change of direction, and finally dribbled 9 m back to the start/finish line. Markers were placed at each turning point, and timing gates (Microgate Witty, Bolzano, Italy) were positioned only at the start/finish line. Two trials were allowed, and the fastest time was recorded. According to the club’s information, all players completed a familiarisation trial before the official measurements were taken, ensuring that each participant understood the procedures and the execution of the tests (Figure 1).

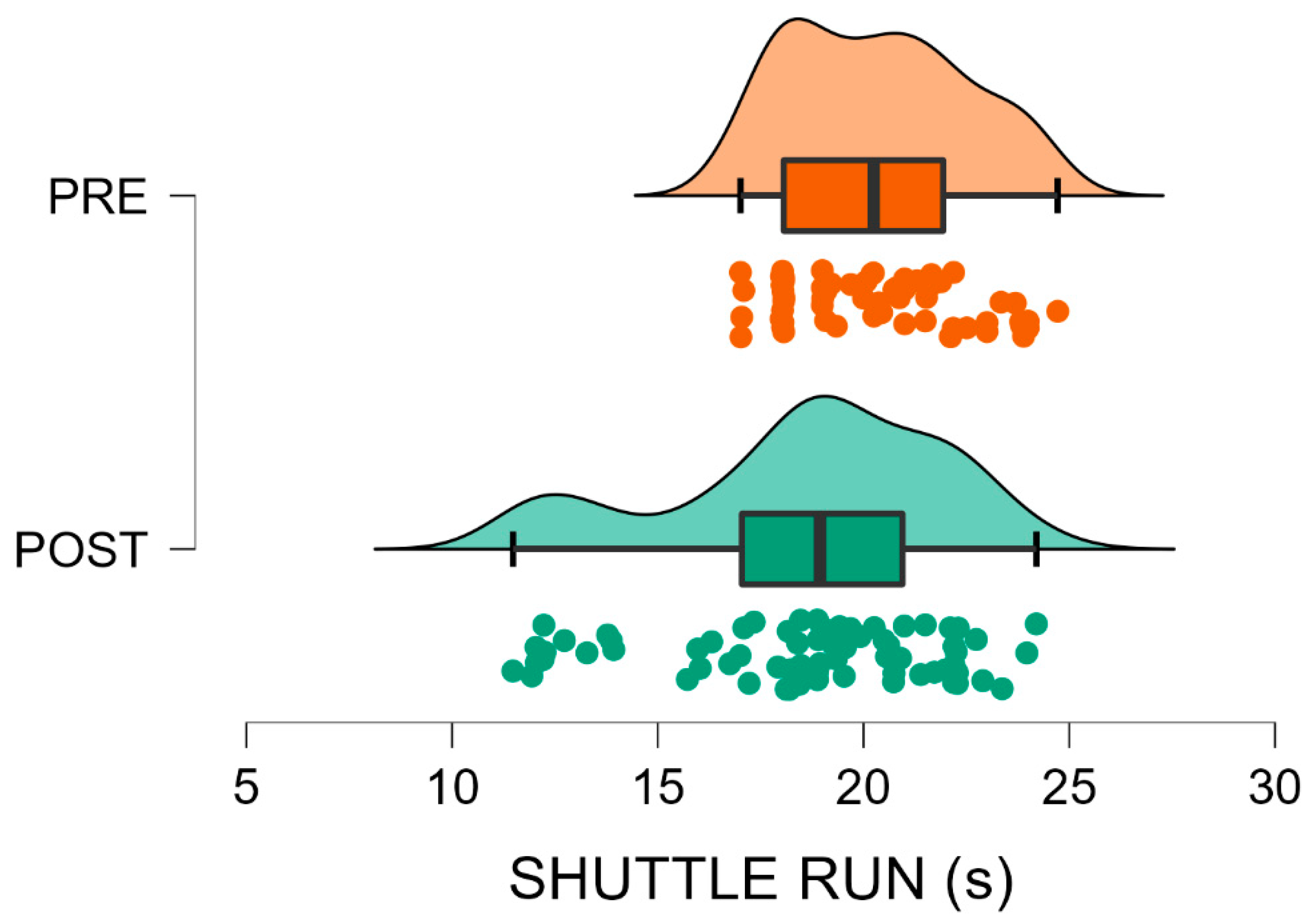

- 10 × 5 m Shuttle Run: evaluated agility and repeated sprint ability. Each participant completed 10 times 5 m sprints with 180° changes of direction, timed manually with a professional stopwatch (Casio HS-3V-1RET, Tokyo, Japan). The test started upon the coach’s verbal “go” signal, which simultaneously activated the stopwatch, and ended when the player completed all shuttle segments. Although timing gates were available, the Shuttle Run was manually timed for both practical and methodological reasons. Practically, the test was administered after the Shuttle Dribble Test, for which the timing gates were already configured at the start/finish line, making manual timing the most efficient option. Methodologically, the Shuttle Run is part of the EUROFIT test battery for children, which recommends using a handheld stopwatch due to its practicality, widespread applicability, and established normative data collected through manual timing [25]. In contrast, the Shuttle Dribble Test, according to its original protocol, requires electronic timing gates to ensure accuracy during ball-dribbling trials [24] (Figure 1).

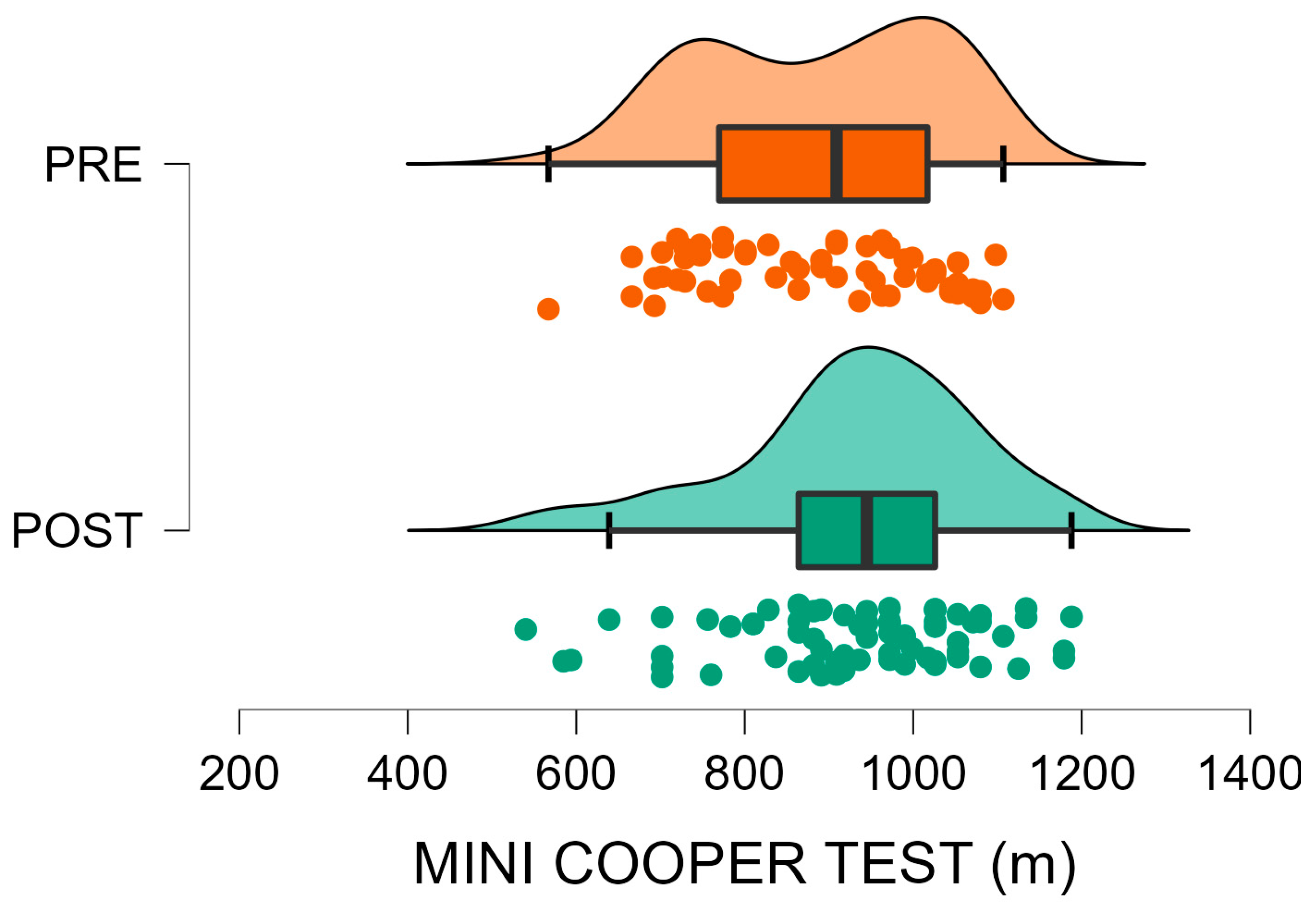

- Mini Cooper Test: evaluated aerobic endurance. The Mini Cooper Test used in this study corresponded to the 6 min version commonly applied in youth field testing [26]. Players ran continuously for six minutes around a 9 × 18 m rectangular course marked by cones at each corner, and the total distance covered was recorded. Children were permitted to walk whenever they could no longer run. According to the club’s guidelines, the trainer stands near the starting cone. Each time a player crossed the starting line, the coach recorded one completed lap. At the end of the six minutes, the coach signalled the cessation of the test with a whistle, and the children were instructed to stop immediately at their current position. The total distance covered was then derived by summing the number of fully completed laps and the additional portion of the final lap, calculated using the known lengths of the circuit sides (18 m for the long side and 9 m for the short side) (Figure 1).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

Descriptive and Comparative Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murr, D.; Feichtinger, P.; Larkin, P.; O’Connor, D.; Höner, O. Psychological talent predictors in youth soccer: A systematic review of the prognostic relevance of psychomotor, perceptual-cognitive and personality-related factors. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, M.; Eyre, E.L.J.; Noon, M.; Morris, R.; Thake, D.; Clarke, N. Fundamental movement skills and perceived competence, but not fitness, are the key factors associated with technical skill performance in boys who play grassroots soccer. Sci. Med. Footb. 2021, 6, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, G.; Raiola, G. Monitoring the performance and technique consolidation in youth football players. Trends Sport Sci. 2020, 27, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trecroci, A.; Cavaggioni, L.; Caccia, R.; Alberti, G. Jump Rope Training: Balance and Motor Coordination in Preadolescent Soccer Players. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2015, 14, 792–798. Available online: http://www.jssm.org/14-4>Contents (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Sannicandro, I.; Agostino, S.; Daga, M.A.; Veglio, F.; Daga, F.A. Developing the Physical Performance in Youth Soccer: Short-Term Effect of Dynamic-Ecological versus Traditional Training Approach for Sub-Elite U13 Players—An Ecological Exploratory Cluster Randomised Trial. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raiola, G.; Altavilla, G. Testing motor skills, general and special coordinative, in young soccer. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2020, 15, S206–S212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merbah, S.; Meulemans, T. Learning a Motor Skill: Effects of Blocked Versus Random Practice a Review. Psychol. Belg. 2011, 51, 15–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, G.B.; Alexandre, D.R.O.; Pinto, J.C.B.L.; Assis, T.V.L.; Faigenbaum, A.D.; Mortatti, A.L. Effects of Integrative Neuromuscular Training on Motor Performance in Prepubertal Soccer Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 1667–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig-Walz, H.; Siemens, W.; Heinisch, S.; Dannheim, I.; Loss, J.; Bujard, M. How the COVID-19 pandemic and related school closures reduce physical activity among children and adolescents in the WHO European Region: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2023, 20, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daga, F.A.; Agostino, S.; Peretti, S.; Beratto, L. COVID-19 nationwide lockdown and physical activity profiles among North-western Italian population using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). Sport Sci. Health 2021, 17, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’isanto, T.; D’elia, F. Body, movement, and outdoor education in pre-school during the COVID-19 pandemic: Perceptions of teachers. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2021, 21, 709–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatedaga, F.; Agostino, S.; Peretti, S.; Beratto, L. The impact of physical activity rate on subjective well-being among North-Western Italian population during COVID-19 nationwide lockdown. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2022, 62, 1127–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, C.M.; Batchelor, F.; Duque, G. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical Activity, Function, and Quality of Life. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2022, 38, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampinini, E.; Donghi, F.; Martin, M.; Bosio, A.; Riggio, M.; Maffiuletti, N.A. Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown on Serie A Soccer Players’ Physical Qualities. Int. J. Sports Med. 2021, 42, 917–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzimiński, Ł.; Padrón-Cabo, A.; Konefał, M.; Chmura, P.; Szwarc, A.; Jastrzębski, Z. The Influence of COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown on the Physical Performance of Professional Soccer Players: An Example of German and Polish Leagues. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampinini, E.; Martin, M.; Bosio, A.; Donghi, F.; Carlomagno, D.; Riggio, M.; Coutts, A.J. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on professional soccer players’ match physical activities. Sci. Med. Footb. 2021, 5, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekulic, D.; Versic, S.; Decelis, A.; Castro-Piñero, J.; Javorac, D.; Dimitric, G.; Idrizovic, K.; Jukic, I.; Modric, T. The Effect of the COVID-19 Lockdown on the Position-Specific Match Running Performance of Professional Football Players; Preliminary Observational Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douchet, T.; Michel, A.; Verdier, J.; Babault, N.; Gosset, M.; Delaval, B. Intensity vs. Volume in Professional Soccer: Comparing Congested and Non-Congested Periods in Competitive and Training Contexts Using Worst-Case Scenarios. Sports 2025, 13, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgans, R.; Di Michele, R.; Drust, B. Soccer Match Play as an Important Component of the Power-Training Stimulus in Premier League Players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018, 13, 665–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, K.A.; Jones, B.; Bennett, M.; Close, G.L.; Gill, N.; Hull, J.H.; Kasper, A.M.; Kemp, S.P.T.; Mellalieu, S.D.; Peirce, N.; et al. Returning to Play after Prolonged Training Restrictions in Professional Collision Sports. Int. J. Sports Med. 2020, 41, 895–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adi-Japhaid, E.; Berke, R.; Shaya, N.; Julius, M.S. Different post-training processes in children’s and adults’ motor skill learning. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padrón-Cabo, A.; Lorenzo-Martnez, M.; De Dios-Álvarez, V.; Rey, E.; Solleiro-Durán, D. Effects of a Short-Term Detraining Period on the Physical Fitness in Elite Youth Soccer Players: A Comparison Between Chronological Age Groups. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2025, 39, e149–e154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotzsch, A.; Papke, A.; Heine, A. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Development of Motor Skills of German 5- to 6-Year-Old Children. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijgen, B.C.H.; Elferink-Gemser, M.T.; Post, W.J.; Visscher, C. Soccer skill development in professionals. Int. J. Sports Med. 2009, 30, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Council of Europe; Committee of Experts on Sports Research. Eurofit: Handbook for the Eurofit Tests of Physical Fitness, 2nd ed.; Council of Europe, Committee for the Development of Sport: Strasbourg, France, 1993; Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/Eurofit.html?hl=it&id=dPH2zQEACAAJ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Ayán, C.; Cancela, J.M.; Romero, S.; Alonso, S. Reliability of two field-based tests for measuring cardiorespiratory fitness in preschool children. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 2874–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, N.; Welsman, J. Clarity and Confusion in the Development of Youth Aerobic Fitness. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asimakidis, N.D.; Vasileiou, S.S.; Dalamitros, A.A.; Nikolaidis, P.T.; Manou, V. Effect of the COVID-19 Confinement Period on Selected Neuromuscular Performance Indicators in Young Male Soccer Players: Can the Maturation Process Counter the Negative Effect of Detraining? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauty, M.; Grondin, J.; Daley, P.; Louguet, B.; Menu, P.; Fouasson-Chailloux, A. Consequences of the SARS-CoV-2 Infection on Anaerobic Performances in Young Elite Soccer Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neville, R.D.; Lakes, K.D.; Hopkins, W.G.; Tarantino, G.; Draper, C.E.; Beck, R.; Madigan, S. Global Changes in Child and Adolescent Physical Activity During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualtieri, A.; Rampinini, E.; Iacono, A.D.; Beato, M. High-speed running and sprinting in professional adult soccer: Current thresholds definition, match demands and training strategies. A systematic review. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5, 1116293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, A.M.; Petiot, G.H.; Clemente, F.M.; Nakamura, F.Y.; Aquino, R. Home training recommendations for soccer players during the COVID-19 pandemic. SportRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washif, J.A.; Sandbakk, Ø.; Seiler, S.; Haugen, T.; Farooq, A.; Quarrie, K.; van Rensburg, D.C.J.; Krug, I.; Verhagen, E.; Wong, D.P.; et al. COVID-19 Lockdown: A Global Study Investigating the Effect of Athletes’ Sport Classification and Sex on Training Practices. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2022, 17, 1242–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, R.S.; Oliver, J.L. The youth physical development model: A new approach to long-term athletic development. Strength Cond. J. 2012, 34, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Sun, G.; Guo, E.; Xu, H.; Wang, Z. Impact of COVID-19 on football attacking players’ match technical performance: A longitudinal study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatedaga, F.; Baseggio, L.; Gollin, M.; Beratto, L. Game-based versus multilateral approach: Effects of a 12-week program on motor skill acquisition and physical fitness development in soccer school children. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2020, 60, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davids, K. Principles of Motor Learning in Ecological Dynamics A comment on Functions of Learning and the Acquisition of Motor Skills (With Reference to Sport). Open Sports Sci. J. 2012, 5, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, G.; Ceruso, R.; Aliberti, S.; Raiola, G. Ecological-Dynamic Approach vs. Traditional Prescriptive Approach in Improving Technical Skills of Young Soccer Players. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Valenciano, A.; Suárez-Iglesias, D.; Sanchez-Lastra, M.A.; Ayán, C. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on University Students’ Physical Activity Levels: An Early Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 624567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharel, M.; Sakamoto, J.L.; Carandang, R.R.; Ulambayar, S.; Shibanuma, A.; Yarotskaya, E.; Basargina, M.; Jimba, M. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdown on movement behaviours of children and adolescents: A systematic review. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e007190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowland, T.W. Developmental Exercise Physiology; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Pre-Interruption (Mean ± SD) | Post-Interruption (Mean ± SD) | Δ% | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass (kg) | 28.81 ± 4.40 | 31.51 ± 6.16 | +9.3% | 0.003 * |

| Height (m) | 1.315 ± 0.057 | 1.341 ± 0.053 | +2.0% | 0.003 * |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 16.61 ± 1.95 | 17.48 ± 2.89 | +5.3% | 0.108 |

| Standing Long Jump (m) | 1.36 ± 0.21 | 1.52 ± 0.24 | +11.2% | <0.001 * |

| Shuttle Dribble Test (s) | 12.03 ± 1.30 | 13.64 ± 2.74 | −13.4% (slower) | <0.001 * |

| Shuttle Run (s) | 20.33 ± 2.15 | 18.71 ± 3.12 | +8.0% (faster) | 0.011 * |

| Mini Cooper Test (m) | 889.2 ± 140.9 | 922.8 ± 148.4 | +3.8% | 0.176 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abate Daga, F.; Sannicandro, I.; Tanturli, A.; Agostino, S. Youth Soccer Development After a Forced Training Interruption: A Retrospective Analysis of Prepubertal Players. Sports 2025, 13, 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120435

Abate Daga F, Sannicandro I, Tanturli A, Agostino S. Youth Soccer Development After a Forced Training Interruption: A Retrospective Analysis of Prepubertal Players. Sports. 2025; 13(12):435. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120435

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbate Daga, Federico, Italo Sannicandro, Alice Tanturli, and Samuel Agostino. 2025. "Youth Soccer Development After a Forced Training Interruption: A Retrospective Analysis of Prepubertal Players" Sports 13, no. 12: 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120435

APA StyleAbate Daga, F., Sannicandro, I., Tanturli, A., & Agostino, S. (2025). Youth Soccer Development After a Forced Training Interruption: A Retrospective Analysis of Prepubertal Players. Sports, 13(12), 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120435