Abstract

Background: Falls are a leading cause of injury and disability among older adults. Conventional clinical tests typically do not challenge reactive postural responses to unexpected perturbations, which limits their ability to comprehensively assess fall risk. Objective: To examine the test–retest reliability of five pragmatic, low-cost, perturbation-based tests designed to identify compensatory stepping strategies in older adults, and to explore their concurrent validity against established clinical assessments. Methods: Fifty-seven older adults (44 community-dwelling and 13 institutionalized) completed five compensatory stepping tests (obstacle crossing, forward push, backward pull, and lateral pulls to the right and left) and conventional functional tests [Timed Up and Go (TUG), 30 s Chair Stand, and the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB)] on two separate days, ten days apart. Cohen’s weighted kappa (Kw) quantified test–retest reliability, and Pearson’s correlation coefficients assessed relationships with conventional tests. Results: Obstacle (Kw = 0.443), forward push (Kw = 0.518), and backward pull (Kw = 0.438) demonstrated moderate agreement overall. Lateral pull tests showed poor reliability. Nevertheless, moderate correlations were observed between some perturbation tests (particularly obstacle and backward pull) and standard clinical measures, especially TUG and SPPB. Conclusions: Although reliability was limited—most notably for lateral perturbations—specific tests showed meaningful associations with validated functional assessments. Pending methodological refinements, these low-cost tools may offer useful insights for initial fall-risk screening.

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization estimates that in 2021 there were approximately, 761 million people aged 65 years or older worldwide, a number projected to reach 1.6 billion by 2050 [1]. In Spain, 19.09% of the population already belongs to this age group [2]. With population aging, the prevalence of conditions that compromise independence and quality of life increases, with falls representing one of the most common serious threats. Approximately one in three adults over the age of 65 experiences at least one fall per year, and these events are a leading cause of injury-related morbidity, hospitalization, and mortality in this population [3]. Beyond their immediate physical consequences, such as fractures and head injuries, falls often result in long-term disability, fear of falling, reduced mobility, and loss of independence [4,5,6]. They also impose substantial economic and social burdens, making fall prevention a major public health priority [7].

Gait is a fundamental motor ability for safe mobility [8], and its deterioration is strongly associated with fall risk. Determinants such as walking speed [9], balance [10], and strength [11] have been widely studied, and various clinical tests have been developed to estimate fall risk in older adults, including the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) [12], Timed Up and Go (TUG) [13], the 30 s Chair Stand [14], the Agility Challenge for the Elderly (ACE) [15], the Functional Reach Test (FRT) [16], the Single-Leg Stance Test (SLST), and the Tinetti Performance-Oriented Mobility Assessment (POMA) [16]. While these tools are inexpensive and easy to administer, they capture only partial aspects of the multifactorial nature of falls. In contrast, most falls occur in response to sudden and unpredictable disturbances, highlighting a mismatch between conventional assessments and real-world fall scenarios [17].

In recent years, perturbation-based interventions—designed to expose individuals to unexpected balance disturbances during stance or gait—have gained increasing attention. These programs aim to enhance compensatory stepping strategies, which are essential for avoiding falls or minimizing their consequences [18,19]. Evidence shows that repeated perturbation exposure improves dynamic balance and recovery responses [18,20,21,22]. Different experimental systems were applied to induce balance loss and evaluate recovery, moving-platform paradigms [18], treadmill-based slips and trips [20,21], and lateral waist-pull systems [22], all of which demonstrated improvements in gait stability, dynamic balance and reactive stepping, with some studies reporting a reduction in fall incidence [22]. Mansfield et al. [18] used a moving-platform paradigm during standing to assess compensatory stepping responses, which were found to predict fall risk in older adults. Allin et al. [20] developed treadmill-based trip and slip perturbations and performed kinematic analyses to evaluate recovery responses. Although no direct correlations with fall risk were observed, the perturbation training improved center of mass stability and enhanced proactive gait adaptations, such as step length, which may contribute to reducing fall risk. Rieger et al. [21] employed unexpected gait perturbations using a movable treadmill platform and demonstrated that perturbation training improved various spatiotemporal gait parameters, helping older adults recover balance more effectively and potentially prevent falls. Finally, Rogers et al. [22] applied repeated lateral waist-pull perturbations as both a training and assessment method, reporting that improvements in reactive stepping translated into a significant reduction in prospective fall incidence. Although repeated exposure to perturbations can improve dynamic balance [18,20,21,22], many of the tools used are technologically demanding and ill-suited to clinical practice.

However, despite these promising results, these protocols typically require high-cost, technologically demanding systems (e.g., waist-pull devices, movable platforms, release systems) to evaluate perturbation responses [23], which limits their application in routine clinical practice. Although more accessible approaches, such as the Reactive Balance Rating [24], have been developed to assess reactive balance, their use remains largely confined to specialized environments. Consequently, there is a clear methodological gap: the absence of low-cost, clinically feasible perturbation-based tests to reliably assess compensatory protective step strategies in older adults. The present study addresses this methodological issue by analyzing the test–retest reliability of five low-cost tests that are easy to administer, require minimal equipment, and are designed for use in clinical settings to identify compensatory protective stepping strategies in older adults.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Fifty-seven healthy older adults (women and men) were enrolled in this cross-sectional study. Recruitment constraints resulted in two groups: 44 community-dwelling participants (non-institutionalized) and 13 institutionalized participants (institutionalized).

A priori, the statistical power for Cohen’s kappa-based reliability analyses was estimated via empirical simulation in R (version 4.5.1; irr package). Assuming an expected agreement of Kappa = 0.70 (“good” reliability) versus a null hypothesis of Kappa = 0.40 at α = 0.05, we generated 1000 simulations of binary categorical data (two equally probable categories) with sample sizes matching the study groups (n = 44 and n = 14). Estimated power was 0.99 for n = 44 and 0.82 for n = 14, indicating adequate power to detect a kappa value significantly greater than the null in both groups. These results suggest sufficient power to detect substantial levels of agreement in the total sample and within subgroups.

Inclusion criteria were: (a) age ≥ 60 years; (b) ability to ambulate independently without assistance; and (c) provision of written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: (a) psychiatric or neurological disorders; (b) substance abuse or dependence; (c) contraindications to physical exertion; (d) diseases or active/ongoing ear infections affecting balance; (e) other conditions that impair balance; and (f) serious fractures within the previous six months (e.g., hip fracture, severe ankle sprain).

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Extremadura (approval reference: 125/2024). All participants were informed of the procedures and provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Instruments and Procedure

Participants reported demographic information (education, occupation) and clinical history (pharmacological therapies, diagnosed diseases, history of falls, and pain assessed using a visual analogue scale). Physical activity level was assessed with the Spanish short version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), which has demonstrated good reliability and validity in Spanish populations [25]. Cognitive status was evaluated with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), a multidomain screening tool covering attention, concentration, executive functions, memory, language, visuoconstruction, calculation, and orientation [26]. MoCA has greater sensitivity than the MMSE [27], with a recommended cut-off score of 23/30 to reduce false positives [28]. Health-related quality of life was assessed using the EQ-5D-5L (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression), including a visual analogue scale (VAS) for general health, validated in Spanish populations [29]. Fear of falling was measured using the Spanish version of the Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I) [30], which has shown high reliability and validity [31,32]. Anthropometrics and age were recorded with a Tanita Body Composition Analyzer BC-418 MA (Tanita Corp., Tokyo, Japan) and a SECA 769 column scale and stadiometer (SECA Corp., Hanover, MD, USA).

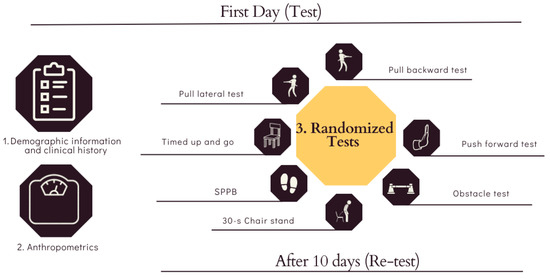

On day 1 and again ten days later (day 2), participants completed four conventional functional tests and five compensatory stepping tests, all administered by the same evaluator on both occasions. The ten-day interval aimed to minimize learning effects [33,34]. Conventional tests were: (1) Timed Up and Go (TUG)—standing up from a chair without armrests, walking 3 m at a comfortable pace without running, turning around a cone, returning, and sitting down [35]; (2) 30 s Chair Stand—assessing lower-limb strength/power [36]. The number of repetitions was recorded, with participants instructed to perform as many repetitions as possible while maintaining correct technique; (3) SPPB—comprising standing balance tasks, 4 m usual gait speed, and a five-repetition sit-to-stand [12]; and (4) five new tests as described below in Section 2.3. Before the actual tests, participants performed one familiarization trial of TUG and a brief 30 s Chair Stand practice (three complete repetitions). A one-minute seated recovery preceded each actual test. Test order was randomized, see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Assessment Procedure and Testing Flow.

2.3. Test for Compensatory Protective Step Strategies

The five tests were designed to determine compensatory protective stepping strategies through direct observation using predefined criteria. Strategy selection may be associated with fall risk, and prior work has shown that older adults more frequently adopt less efficient and less safe strategies than younger adults [23]. Scoring was informed by previous literature and anchored to the conceptual framework of the SPPB [12]. In our scheme, lower scores denote safer and more efficient strategies, whereas higher scores correspond to less effective or riskier strategies. Standardized terminology for compensatory stepping strategies was adopted based on recent Delphi-based consensus recommendations [37].

- Obstacle test: Participants walked 7.5 m at a comfortable pace. A rectangular obstacle (40 cm long × 14 cm high × 8 cm wide) was placed midway along the walkway. Scoring (1–3 points): 1 = long step strategy used effectively to clear the obstacle (safest); 2 = short step strategy used to clear the obstacle; 3 = failed execution of the chosen strategy (e.g., tripping and interrupting gait). Prior studies suggest that when reaction time permits, a lowering/long step strategy is the safer option [23,38,39]; therefore, the lowest score was assigned to the safest strategy.

- Push forward test: Standing with both feet hip-width apart, participants received a manual forward perturbation from the evaluator and were instructed to recover balance and return to the initial position. Scoring (1–2 points): 1 = single forward step longer than a usual step; 2 = multiple steps. Multiple steps to recover balance are associated with increased fall risk [40]; thus, the single-step response was scored as safer. The push was applied at a random time between 0 and 30 seconds to minimize anticipation. In addition, the evaluator applied the push form an approximately 4 cm distance to the upper back, delivered quickly, strongly and sharply.

- Pull backward test: Standing with both feet hip-width apart, participants received a manual backward perturbation (pull). Scoring (1–2 points): 1 = single backward step longer than a usual step; 2 = multiple steps. The pull was applied at a random time between 0 and 30 seconds to minimize anticipation. In addition, the evaluator performed a 4 cm pull at hip level using a rope, at maximal velocity and strongly.

- Pull lateral test (right and left): Standing with both feet hip-width apart, participants received manual lateral pulls to the right and left in random order. Scoring (1–4 points): 1 = loaded sidestep; 2 = unloaded sidestep or medial sidestep; 3 = crossover step; 4 = limb-collision compensatory step. Older adults more often exhibit unloaded or medial sidesteps, multiple steps, and collision between feet than younger adults [23,41,42]; these strategies are generally less efficient and may increase instability and collision risk [23,42]. Accordingly, the loaded sidestep received the safest score (1). Each pull was applied at a random time between 0 and 30 seconds to minimize anticipation. In addition, the evaluator performed a 4 cm pull at hip level using a rope, at maximal velocity and strongly.

All tests were video-recorded using two Xiaomi Redmi Note 8 smartphones (Xiaomi Corp., Beijing, China) positioned at 1.5 m height: one lateral view at 2.5 m and one frontal view at 4 m. Further details are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Document S1).

2.4. Timing and Repetition Measurement

A manual stopwatch was used during SPPB balance and 4 m gait speed tasks. An automatic Chronopic system (Chronojump, BoscoSystem®, Barcelona, Spain) was used for TUG via a DIN A4-sized contact platform placed on the backrest of the chair to open/close the circuit and capture test time [33,43]. The same device was placed on the seat to count repetitions during the 30 s Chair Stand and the SPPB five-times sit-to-stand.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using SPSS (version 25.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Parametric tests were conducted after verifying normality with the Shapiro–Wilk test, and the Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the baseline characteristics of the two independent groups (institutionalized and non-institutionalized).

Weighted Cohen’s kappa (Kw; linear and quadratic weights) [44] was used to evaluate test–retest reliability for each item, with significance set at p ≤ 0.05. Kw was interpreted as [45]: poor to fair (≤0.40), moderate (0.41–0.60), substantial (0.61–0.80), and excellent (≥0.81). In addition, Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC) were calculated for each test by group and for the total score of each test, to enable comparisons with previous studies. Concurrent validity was explored using Pearson’s correlations between each compensatory test and TUG, 30 s Chair Stand, and SPPB scores. Following Schober [46], correlation strengths were categorized as negligible (0.00–0.10), weak (0.10–0.39), moderate (0.40–0.69), strong (0.70–0.89), and very strong (0.90–1.00). Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Forty-four community-dwelling participants (39 women, 5 men) and thirteen institutionalized participants (3 women, 10 men) completed the study. Community-dwelling women and men had mean (SD) ages of 70.33 (4.82) and 71.80 (4.92) years, weights of 71.00 (13.05) and 76.24 (5.48) kg, and heights of 1.56 (0.09) and 1.66 (0.04) m, respectively. Institutionalized women and men had mean (SD) ages of 79.67 (8.33) and 77.60 (8.46) years, weights of 75.50 (16.68) and 78.90 (17.23) kg, and heights of 1.53 (0.03) and 1.66 (0.09) m, respectively. Both groups exhibited fear of falling and MoCA scores consistent with cognitive decline (MoCA ≤ 23), although the institutionalized group presented greater cognitive deterioration. Fear of falling was low-to-moderate among community-dwelling participants and high among institutionalized participants; see Table 1. Significant between-group differences were observed for age (p = 0.002), height (p = 0.025), MoCA (p = 0.001), FES-I (p = 0.010), TUG (p < 0.001), and 30 s Chair Stand (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the participants by sex.

3.2. Test–Retest Reliability of Perturbations Tests

Reliability outcomes for each compensatory test are summarized in Table 2. In the total sample, obstacle (Kw = 0.443; 95% CI: 0.229–0.656), forward push (Kw = 0.518; 95% CI: 0.307–0.729), and backward pull (Kw = 0.438; 95% CI: 0.146–0.729) showed moderate agreement. Among community-dwelling participants, moderate agreement was observed for forward push (Kw = 0.495; 95% CI: 0.285–0.705) and backward pull (Kw = 0.488; 95% CI: 0.190–0.787). Among institutionalized participants, obstacle showed moderate agreement and backward pull achieved excellent agreement (Kw = 1.00; 95% CI: 1.00–1.00). Lateral pull tests exhibited poor reliability overall.

Table 2.

Test–retest reliability of each compensatory protective step strategy test.

Since there were participants in the non-institutionalized group who obtained higher or lower scores on the MoCA, it was decided to conduct a detailed study of the different perturbation-based functional tests, considering the score of cognitive impairment provided by MoCA. In this sense, test–retest reliability outcomes for compensatory protective step strategies in the non-institutionalized group are summarized in Table 3. In participants with MoCA ≤ 23, push forward showed moderate agreement (Kw = 0.529; 95%CI: 0.135–0.924), whereas obstacles (kw = 0.463; 95% IC: 0.185–0.741) and backward pull (kw = 0.294; 95% IC: −0.141–0.730) yielded lower values. In those with MoCA >23, backward pull demonstrated substantial reliability (Kw = 0.704; 95% IC: 0.328–1.079), while lateral pulls to the left and right showed poor to fair agreement.

Table 3.

Test–retest reliability of each compensatory protective step strategy test in the non-institutional group, with and without cognitive impairment.

3.3. Correlations

Table 4 presents correlations between compensatory tests and conventional assessments. In community-dwelling participants, the obstacle test correlated significantly with TUG at retest (r = 0.448), and with SPPB at test (r = −0.443) and retest (r = −0.354). In the total sample, significant relationships were evident for most comparisons involving the obstacle test, except for the 30 s Chair Stand at test. For the backward pull test, significant values were observed in the community-dwelling group for TUG at retest (r = 0.305). In the total sample, the backward pull test correlated significantly at retest with TUG (r = 0.403), 30 s Chair Stand (r = −0.267), and SPPB (r = −0.370). For the right lateral pull, significant associations were found with SPPB at test in community-dwelling participants (r = −0.338) and, in the total sample at retest, with TUG (r = 0.332) and 30 s Chair Stand (r = −0.296).

Table 4.

Correlations between the value obtained in each compensatory protective step strategy test in test and retest with TUG, 30 s Chair and SPPB.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to analyze the reliability of five pragmatic, low-cost, perturbation-based tests designed to identify compensatory protective stepping strategies in older adults. This represents a pioneering attempt to create simple, inexpensive field tests. However, the results indicate that only the forward and backward push tests demonstrated moderate agreement, with confidence intervals ranging from poor to substantial agreement. In addition, some correlations were observed between the compensatory protective stepping tests and the TUG, the 30-Second Chair Stand Test, and the SPPB. Overall, these findings suggest that the five tests do not exhibit sufficient reproducibility, as reflected by low Kappa coefficients. Nevertheless, the moderate-to-strong correlations found for the obstacle test, the backward pull test, and the right lateral pull test with the TUG, the 30-Second Chair Stand Test, and/or the SPPB support their potential convergent validity in assessing fall risk.

In the current literature, tripping simulations are commonly used. Some studies employ treadmill deceleration or acceleration methods [47], while others focus on obstacle avoidance strategies [39]. The treadmill approach is widely used to analyze the relationship between trunk kinematics and kinetics and recovery responses [38,48,49]. Although frequently applied, this method presents some inconsistencies [50], even though Shih et al. [50] proposed a reliable treadmill-based protocol. Despite this, its high cost and laboratory requirements limit its applicability in clinical settings. For these reasons, obstacle avoidance strategies were adopted, as these require only an obstacle and a walkway, making them inexpensive and easy to implement. They could serve as an initial cost-effective screening tool to detect gait problems or support clinical assessments.

The obstacle test demonstrated low reliability across all groups and in the overall sample, with Cohen’s Kappa values below acceptable thresholds. This may be due since participants were instructed to walk at their preferred pace. Variability in walking speed could have influenced compensatory gait responses and, consequently, the reliability of the test. Walking speed is a crucial factor in these assessments, as it affects the stepping strategy used during obstacle avoidance. According to Chen et al. [39], older adults are more likely to adopt a short-step strategy at both high and low walking speeds, as it is easier for them to execute compared to younger adults, who more often use the long-step strategy. The latter, however, is safer [23]. The choice of strategy depends on the time available to react to the obstacle, which is determined by walking speed: the faster the pace, the shorter the reaction time. A potential solution to this limitation would be to have participants complete the obstacle test four times—two at a comfortable walking speed and two at their maximum walking speed, presented in randomized order. This design could help identify the stepping strategies participants tend to use at different speeds, providing insight into their ability to adapt gait to environmental demands. Such demands are influenced by external conditions (e.g., outdoor obstacles or uneven surfaces) [51], as well as motor control, balance, environmental perception, and motor planning [52]. Notably, motor planning is closely linked to cognitive flexibility. Early detection of deficits in these areas may guide the development of targeted interventions to reduce fall risk in older adults.

Release and pull methods have also been used to evaluate balance recovery through compensatory stepping responses, either forward or backward. More recent protocols have attempted to increase control and replicability, particularly regarding release speed or the force applied during the pull [53,54,55,56]. However, as with the obstacle test, these methods are not easily applicable in clinical practice due to their technical complexity. In line with this study’s objectives, two simplified tests—the forward push and the backward pull—were developed, based on previously established protocols [53,54,55,56]. In these tests, the perturbation distance was set at 4 cm [41,57,58,59], and the evaluator performed both movements at maximum speed. The results of the present study demonstrated moderate reliability across the overall sample and within both institutionalized and non-institutionalized groups. Notably, among non-institutionalized participants, those without cognitive impairment showed strong reliability, whereas those with cognitive impairment exhibited lower reliability. This pattern is consistent with previous studies indicating that mild cognitive impairment compromises reactive balance control and increases response variability under both single and dual-task perturbations [60,61]. A plausible explanation is that unimpaired individuals can consistently select the same transition strategy across sessions, suggesting the learning of a specific response pattern [62,63]. Consequently, this group may benefit from shorter response times, greater motor control, and more effective motor planning. Future studies with larger and more diverse samples are warranted to further clarify the role of cognitive status in test reliability and to determine whether compensatory strategies differ across populations. This study represents the first attempt to translate a laboratory-based test into a low-cost clinical assessment. To increase standardization, the researchers designed protocols with more consistent perturbation directions and displacements (backward pull and forward push), thereby facilitating execution and identification of compensatory stepping strategies. Nevertheless, the findings cannot be directly compared to laboratory-based studies, where variables such as speed, acceleration, displacement, and perturbation type are more rigorously controlled. Moreover, laboratory perturbations are typically less predictable for participants, unlike the more structured procedures used here.

Similarly, the lateral pull test represents another attempt to standardize a laboratory-based perturbation into a low-cost clinical tool. The lateral pull test is commonly employed to analyze compensatory protective stepping responses following perturbations in the sagittal plane [41,55,64,65,66]. In this study, the evaluator applied a 4 cm pull at maximum speed, following standardized instructions. As with the push and backward pull tests, the relatively low variability in speed, acceleration, and direction may have allowed participants to anticipate perturbation during the second trial. Nevertheless, these tests may be valuable as screening tools, as the initial responses recorded in the first trial were unanticipated. This provides insight into older adults’ natural abilities to respond to sudden perturbations and helps identify innate compensatory strategies. With targeted training, such responses can be strengthened or replaced with more effective motor strategies, as demonstrated by Mansfield et al. [18] and Rogers et al. [22].

Despite these limitations, significant correlations were found between some of the new tests—particularly the obstacle test, the backward pull test, and the right lateral pull test—and established functional measures such as the Timed Up and Go (TUG) [13], the 30-Second Chair Stand Test [14], and the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) [12]. These findings suggest that, although the new instruments are not yet sufficiently reliable, they may still provide valuable information regarding the motor strategies older adults adopt in response to perturbations and their relationship to fall risk. Importantly, the tests developed in this study differ from other low-cost clinical tools, such as the SPPB [12], TUG [13], 30-Second Chair Stand Test [14], Agility Challenge for the Elderly (ACE) [15], Functional Reach Test (FRT) [16], Single-Leg Stance Test (SLST), or the Tinetti Performance-Oriented Mobility Assessment (POMA) [16], as these do not involve external perturbations and therefore offer greater objectivity and reliability.

An important consideration when interpreting these findings is whether the modest reliability reflects test limitations or true variability in compensatory responses. The non-standardized walking speed in the obstacle test and the manual application of perturbations may have reduced reproducibility. At the same time, variability in compensatory protective stepping is inherent to balance recovery, which depends on motor control, environmental perception, motor planning, and cognitive flexibility. Evidence from Batcir et al. [41] or Borrelli et al. [19] shows that recurrent fallers exhibit greater variability in step initiation, step duration, larger centre of mass displacement and different strategy selection compared to non-fallers, suggesting that such differences are systematic and clinically meaningful rather than random noise. Taken together, the modest reliability observed here likely reflects a combination of methodological constraints and genuine variability in protective responses, the latter of which may offer valuable insights for individualized fall-risk assessment.

5. Practical and Clinical Implications

Developed perturbation-based tests, despite their limited reliability, may provide useful preliminary information for clinicians and therapists. The initial, unanticipated responses observed could help identify deficits in gait adaptability, balance recovery, and compensatory stepping strategies that are not captured by traditional functional tests. This approach may support the early detection of individuals at higher risk of falls.

In practice, these tests could be implemented in clinical or community settings as low-cost screening tools, particularly when complemented with simple modifications such as trials at different walking speeds or longer intervals between assessments. The outcomes may guide targeted interventions focused on balance training, obstacle negotiation, and cognitive-motor functions, ultimately contributing to fall prevention and the preservation of independence in older adults.

6. Conclusions

An initial effort to translate laboratory perturbation paradigms into low-cost, clinically applicable tests for assessing compensatory stepping strategies in older adults is presented. Reliability was limited overall—particularly for lateral perturbations—yet several tests showed moderate agreement and meaningful correlations with established functional assessments. With methodological refinements and further validation, these pragmatic tools could support affordable, field-based screening of reactive balance capacity and inform targeted preventive interventions

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/sports13110375/s1, Document S1: Five Low-Cost Tests to identify compensatory protective step strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.G. and M.M.-A.; methodology, M.M.-A. and S.V.; validation, N.G., S.V. and J.L.L.-L., formal analysis, M.M.-A.; investigation, M.M.-A.; resources, N.G.; data curation, M.M.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.-A.; writing—review and editing, J.L.L.-L., S.V., J.P.F.-G. and N.G.; visualization J.P.F.-G. and F.J.D.-M.; supervision J.L.L.-L., S.V. and N.G., project administration, N.G.; funding acquisition, N.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by in the framework of the Spanish National R + D + i Plan, the current project PID2019-107191RB I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 was funded by the Spanish Agency of Research of the Spanish Ministry of Sciences and Innovation MICIU/AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033 and by “ERDF A way of making Europe”. The author M.M.-A. was supported by a grant from the “Sistema Extremeño de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación” by Junta de Extremadura and co-financed by FSE+ of Extremadura (PD23108). This study was co-funded by the Research Grant for Groups (GR24088, AFYCAV Group) co-funded in its part at 85% by European Union, ERDF/EU and Junta de Extremadura “a way of doing Europe.” This study was supported by the Biomedical Research Excellence Networking Center on Frailty and Healthy Aging (CIBERFES) and ERDF/EU funds from the European Union (CB16/10/00477) “a way of making Europe”. The funders played no role in the study design, the data collection, and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Extremadura (protocol code 125//2024 and date of approval 8 May 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available because participants consented to keep their information confidential. Nevertheless, the data may be made available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This study was made possible through the collaboration of the Fundación Jóvenes y Deporte of the Junta de Extremadura, the Servicio Extremeño de Promoción de la Autonomía Personal y Atención a la Dependencia (SEPAD) of the Junta de Extremadura, within the framework of the program El Ejercicio Te Cuida in Cáceres and Casar de Cáceres. Appreciation is also extended to the Geryvida and Ciudad Jardín San Jorge residences in Cáceres for their valuable collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Una Población Que Envejece Exige Más Pensiones y Más Salud. Available online: https://news.un.org/es/story/2023/01/1517857#:~:text=En2021%2C761millonesde,a1600millonesen2050 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- INE. Pirámide de La Población Empadronada En España. 2022. Available online: http://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736145519&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735576715 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Salari, N.; Darvishi, N.; Ahmadipanah, M.; Shohaimi, S.; Mohammadi, M. Global Prevalence of Falls in the Older Adults: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2022, 17, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Wang, D.; Ren, W.; Liu, X.; Wen, R.; Luo, Y. The Global Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Fear of Falling among Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Ou, X.; Li, J. The Risk of Falls among the Aging Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 902599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishya, R.; Vaish, A. Falls in Older Adults Are Serious. Indian J. Orthop. 2020, 54, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, Y.K.; Miller, G.F.; Kakara, R.; Florence, C.; Bergen, G.; Burns, E.R.; Atherly, A. Healthcare Spending for Non-Fatal Falls among Older Adults, USA. Inj. Prev. 2024, 30, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stergiou, N. Biomechanics and Gait Analysis; Academix Press: Omaha, NE, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bridenbaugh, S.A.; Kressig, R.W. Laboratory Review: The Role of Gait Analysis in Seniors’ Mobility and Fall Prevention. Gerontology 2011, 57, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesinski, M.; Hortobágyi, T.; Muehlbauer, T.; Gollhofer, A.; Granacher, U. Effects of Balance Training on Balance Performance in Healthy Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 1721–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, A.T.; Steele, J.; Angielczyk, D.; Belio, M.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Quiles, N.; Askin, N.; Abou-Setta, A.M. Comparison of Power Training vs Traditional Strength Training on Physical Function in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2211623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guralnik, J.M.; Simonsick, E.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Glynn, R.J.; Berkman, L.F.; Blazer, D.G.; Scherr, P.A.; Wallace, R.B. A Short Physical Performance Battery Assessing Lower Extremity Function: Association with Self-Reported Disability and Prediction of Mortality and Nursing Home Admission. J. Gerontol. 1994, 49, M85–M94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, E.; Galvin, R.; Keogh, C.; Horgan, F.; Fahey, T. Is the Timed Up and Go Test a Useful Predictor of Risk of Falls in Community Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta- Analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2014, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.J.; Rikli, R.E.; Beam, W.C. A 30-s Chair-Stand Test as a Measure of Lower Body Strength in Community-Residing Older Adults. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 1999, 70, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, E.; Faude, O.; Zubler, A.; Roth, R.; Zahner, L.; Rössler, R.; Hinrichs, T.; Van Dieën, J.H.; Donath, L. Validity and Reliability of a Novel Integrative Motor Performance Testing Course for Seniors: The “Agility Challenge for the Elderly (ACE)”. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omaña, H.; Bezaire, K.; Brady, K.; Davies, J.; Louwagie, N.; Power, S.; Santin, S.; Hunter, S.W. Functional Reach Test, Single-Leg Stance Test, and Tinetti Performance-Oriented Mobility Assessment for the Prediction of Falls in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Phys. Ther. 2021, 101, pzab173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hezel, N.; Buchner, T.; Becker, C.; Bauer, J.M.; Sloot, L.H.; Steib, S.; Werner, C. The Stepping Threshold Test for Assessing Reactive Balance Discriminates between Older Adult Fallers and Non-Fallers. Front. Sport. Act. Living 2024, 6, 1462177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, A.; Peters, A.L.; Liu, B.A.; Maki, B.E. Effect of a Perturbation-Based Balance Training Program on Compensatory Stepping and Grasping Reactions in Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Phys. Ther. 2010, 90, 476–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, J.; Creath, R.; Gray, V.; Rogers, M. Untangling Biomechanical Differences in Perturbation-Induced Stepping Strategies for Lateral Balance Stability in Older Individuals. J. Biomech. 2021, 114, 110161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allin, L.J.; Brolinson, P.G.; Beach, B.M.; Kim, S.; Nussbaum, M.A.; Roberto, K.A.; Madigan, M.L. Perturbation-Based Balance Training Targeting Both Slip- and Trip-Induced Falls among Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieger, M.M.; Papegaaij, S.; Pijnappels, M.; Steenbrink, F.; van Dieën, J.H. Transfer and Retention Effects of Gait Training with Anterior-Posterior Perturbations to Postural Responses after Medio-Lateral Gait Perturbations in Older Adults. Clin. Biomech. 2020, 75, 104988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, M.W.; Creath, R.A.; Gray, V.; Abarro, J.; McCombe Waller, S.; Beamer, B.A.; Sorkin, J.D. Comparison of Lateral Perturbation-Induced Step Training and Hip Muscle Strengthening Exercise on Balance and Falls in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2021, 76, e194–e202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo-Alonso, M.; Murillo-Garcia, A.; Leon-Llamas, J.L.; Villafaina, S.; Gomez-Alvaro, M.C.; Morcillo-Parras, F.A.; Gusi, N. Classification and Definitions of Compensatory Protective Step Strategies in Older Adults: A Scoping Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, M.L.; Aviles, J.; Allin, L.J.; Nussbaum, M.A.; Alexander, N.B. A Reactive Balance Rating Method That Correlates with Kinematics after Trip-like Perturbations on a Treadmill and Fall Risk among Residents of Older Adult Congregate Housing. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2018, 73, 1222–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboubi Anarjan, P.; Monfared, H.H.; Arslan, N.B.; Kazak, C.; Bikas, R. Analysis of the International Physical Guidelines for Data Processing and Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)—Short and Long Forms. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E Struct. Rep. Online 2005, 68, o2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Brief Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Garcia, A.; Leon-Llamas, J.L.; Villafaina, S.; Rohlfs-Dominguez, P.; Gusi, N. MoCA vs. MMSE of Fibromyalgia Patients: The Possible Role of Dual-Task Tests in Detecting Cognitive Impairment. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carson, N.; Leach, L.; Murphy, K.J. A Re-Examination of Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) Cutoff Scores. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2017, 33, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, G.; Garin, O.; Pardo, Y.; Vilagut, G.; Pont, À.; Suárez, M.; Neira, M.; Rajmil, L.; Gorostiza, I.; Ramallo-Fariña, Y.; et al. Validity of the EQ–5D–5L and Reference Norms for the Spanish Population. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 2337–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomas-Vega, R.; Hita-Contreras, F.; Mendoza, N.; Martínez-Amat, A. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Falls Efficacy Scale International in Spanish Postmenopausal Women. Menopause 2012, 19, 904–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbaere, K.; Close, J.C.T.; Mikolaizak, A.S.; Sachdev, P.S.; Brodaty, H.; Lord, S.R. The Falls Efficacy Scale International (FES-I). A Comprehensive Longitudinal Validation Study. Age Ageing 2010, 39, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardley, L.; Beyer, N.; Hauer, K.; Kempen, G.; Piot-Ziegler, C.; Todd, C. Development and Initial Validation of the Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I). Age Ageing 2005, 34, 614–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Garcia, A.; Villafaina, S.; Leon-Llamas, J.L.; Sánchez-Gómez, J.; Domínguez-Muñoz, F.J.; Collado-Mateo, D.; Gusi, N. Mobility Assessment under Dual Task Conditions in Women with Fibromyalgia: A Test-Retest Reliability Study. PM R 2021, 13, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon-Llamas, J.L.; Villafaina, S.; Murillo-Garcia, A.; Collado-Mateo, D.; Domínguez-Muñoz, F.J.; Sánchez-Gómez, J.; Gusi, N. Strength Assessment Under Dual Task Conditions in Women with Fibromyalgia: A Test–Retest Reliability Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsiadlo, D.; Richardson, S. The Timed Up and Go: A Test of Basic Functional Mobility for Frail Elderly Persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1991, 39, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collantes, M.B.; García, C.L.A.; Fonseca, A.A.; Patiño, J.P.; Monsalve, A.; Gómez, E. Reproducibilidad de Las Pruebas Arm Curl y Chair Stand Para Evaluar Resistencia Muscular En Población Adulta Mayor. Rev. Cienc. La Salud 2012, 10, 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Melo-Alonso, M.; Leon-Llamas, J.L.; Villafaina, S.; Gomez-Alvaro, M.C.; Olivares, P.R.; Padilla-Moledo, C.; Gusi, N. Interdisciplinary Expert Agreement on Group and Definitions for Compensatory Protective Step Strategies to Prevent Falls: A e-Delphi Method Study. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2025, 29, 101227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavol, M.J.; Owings, T.M.; Foley, K.T.; Grabiner, M.D. The Sex and Age of Older Adults Influence the Outcome of Induced Trips. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 1999, 54, M103–M108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.C.; Ashton-Miller, J.; Alexander, N.; Schultz, A. Age Effects on Strategies Used to Avoid Obstacles. Gait Posture 1994, 2, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te, B.; Komisar, V.; Aguiar, O.M.; Shishov, N.; Robinovitch, S.N. Compensatory Stepping Responses during Real-Life Falls in Older Adults. Gait Posture 2023, 100, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batcir, S.; Shani, G.; Shapiro, A.; Alexander, N.; Melzer, I. The Kinematics and Strategies of Recovery Steps during Lateral Losses of Balance in Standing at Different Perturbation Magnitudes in Older Adults with Varying History of Falls. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mille, M.-L.; Johnson, M.E.; Martinez, K.M.; Rogers, M.W. Age-Dependent Differences in Lateral Balance Recovery through Protective Stepping. Clin. Biomech. 2005, 20, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collado-Mateo, D.; Domínguez-Muñoz, F.J.; Adsuar, J.C.; Merellano-Navarro, E.; Olivares, P.R.; Gusi, N. Reliability of the Timed up and Go Test in Fibromyalgia. Rehabil. Nurs. 2018, 43, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Gao, Q.; Yu, T. Kappa Statistic Considerations in Evaluating Inter-Rater Reliability between Two Raters: Which, When and Context Matters. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portney, L.G. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Evidence-Based Practice, 4th ed.; F.A. Davis Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Nguyen, T.K.; Bhatt, T. Trip-Related Fall Risk Prediction Based on Gait Pattern in Healthy Older Adults: A Machine-Learning Approach. Sensors 2023, 23, 5536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavol, M.J.; Owings, T.M.; Foley, K.T.; Grabiner, M.D. Mechanisms Leading to a Fall from an Induced Trip in Healthy Older Adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owings, T.M.; Pavol, M.J.; Grabiner, M.D. Mechanisms of Failed Recovery Following Postural Perturbations on a Motorized Treadmill Mimic Those Associated with an Actual Forward Trip. Clin. Biomech. 2001, 16, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, H.T.; Gregor, R.; Lee, S.P. Description, Reliability and Utility of a Groundreaction- Force Triggered Protocol for Precise Delivery of Unilateral Trip-like Perturbations during Gait. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chippendale, T.; Raveis, V. Knowledge, Behavioral Practices, and Experiences of Outdoor Fallers: Implications for Prevention Programs. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2017, 72, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, J.J.; Winter, D.A.; Patla, A.E. Strategies for Recovery from a Trip in Early and Late Swing during Human Walking. Exp. Brain Res. 1994, 102, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, M.L.; Smith, L.K.; Dibble, L.E.; Foreman, K.B. Age-Related Difference in Postural Control during Recovery from Posterior and Anterior Perturbations. Anat. Rec. 2015, 298, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelen, D.G.; Wojcik, L.A.; Schultz, A.B.; Ashton-Miller, J.A.; Alexander, N.B. Age Differences in Using a Rapid Step to Regain Balance during a Forward Fall. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 1997, 52, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mille, M.-L.; Johnson-Hilliard, M.; Martinez, K.M.; Zhang, Y.; Edwards, B.J.; Rogers, M.W. One Step, Two Steps, Three Steps More... Directional Vulnerability to Falls in Community-Dwelling Older People. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2013, 68, 1540–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.-Y.; Gadareh, K.; Bronstein, A.M. Forward-Backward Postural Protective Stepping Responses in Young and Elderly Adults. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2014, 34, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batcir, S.; Shani, G.; Shapiro, A.; Melzer, I. Characteristics of Step Responses Following Varying Magnitudes of Unexpected Lateral Perturbations during Standing among Older People-a Cross-Sectional Laboratory-Based Study. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidcoe, P.E.; Rogers, M.W. A Closed-Loop Stepper Motor Waist-Pull System for Inducing Protective Stepping in Humans. J. Biomech. 1998, 31, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, B.W.; Horak, F.B.; Kamsma, Y.P.T.; Peterson, D.S. Older Adults Can Improve Compensatory Stepping with Repeated Postural Perturbations. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015, 7, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kannan, L.; Pitts, J.; Szturm, T.; Purohit, R.; Bhatt, T. Perturbation-Based Dual Task Assessment in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2024, 5, 1384582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangen, G.G.; Engedal, K.; Bergland, A.; Moger, T.A.; Mengshoel, A.M. Relationships between Balance and Cognition in Patients with Subjective Cognitive Impairment, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and Alzheimer Disease. Phys. Ther. 2014, 94, 1123–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrum, C.; Bhatt, T.S.; Gerards, M.H.G.; Karamanidis, K.; Rogers, M.W.; Lord, S.R.; Okubo, Y. Perturbation-Based Balance Training: Principles, Mechanisms and Implementation in Clinical Practice. Front. Sport. Act. Living 2022, 4, 1015394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, N.; Tanaka, S.; Mani, H.; Inoue, T.; Wang, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Asaka, T. Adaptation of the Compensatory Stepping Response Following Predictable and Unpredictable Perturbation Training. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 674960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrelli, J.; Creath, R.A.; Pizac, D.; Hsiao, H.; Sanders, O.P.; Rogers, M.W. Perturbation-Evoked Lateral Steps in Older Adults: Why Take Two Steps When One Will Do? Clin. Biomech. 2019, 63, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonneau, E.; Smeesters, C. Effects of Age and Lean Direction on the Threshold of Single-Step Balance Recovery in Younger, Middle-Aged and Older Adults. Gait Posture 2014, 39, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yungher, D.A.; Morgia, J.; Bair, W.-N.; Inacio, M.; Beamer, B.A.; Prettyman, M.G.; Rogers, M.W. Short-Term Changes in Protective Stepping for Lateral Balance Recovery in Older Adults. Clin. Biomech. 2012, 27, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).