Abstract

This article aims to make a scoping review of Validating Questionnaires used in the field of lower limb (LL) rehabilitation in which systems, devices or exergames are used. Its main objective is to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the results obtained in the validation of questionnaires, as well as to identify specific criteria for evaluating systems, devices or exergames in the area of LL rehabilitation, through the analysis of validating instruments and their application in different associated contexts. The article details the methodology employed, a PRISMA ScR method review which included database research and an evaluation of the selected studies. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to select all relevant studies, resulting in 81 studies after initial review based on titles and abstracts. Subsequently, the criteria were again applied to read the full text, resulting in 58 final studies. The document distinguishes between standardized and non-standardized validating questionnaires, emphasizing that standardized validating questionnaires have undergone rigorous statistical processes to ensure their validity, reliability and consistency. The information compiled in the tables provides a solid basis for identifying and evaluating validation questionnaires in the above-mentioned context. This resource constitutes an accurate and reliable reference for selecting the most appropriate instruments for future research and comparisons with similar work. This article is a valuable resource for those interested in the validation of questionnaires used in the field of lower limb rehabilitation systems/devices/exergames.

1. Introduction

According to the last report of World Health Organization, there are about 1.3 billion people with disabilities, about 16% of the world’s population [1]. Rehabilitation plays a crucial role in helping people recover or improve their functional capabilities after an injury, illness or health problem. The need for rehabilitation worldwide is substantial, as by the year 2024, it was estimated that 2.4 billion people around the world may benefit from these services [2]. Musculoskeletal disorders, sensory impairment and injuries are the main causes of disability that require rehabilitation. Musculoskeletal disorders affect approximately 1.710 million people (22%), while sensory impairments affect about 730 million (9.4%). Injuries, including spinal cord injuries and traumatic brain injuries, affect approximately 1000 million people (19%) [3,4,5].

Rehabilitation offers numerous benefits, such as improved functional capabilities, reduced pain and suffering, and improved overall life quality. It also plays a vital role in helping people regain their functional abilities and improve their well-being.

There are several modalities to carry out the rehabilitation process. According to the form of rehabilitation that can be incorporated, a rehabilitation system, refers to a set of tools, devices, or structured programs designed to help individuals recover or improve physical, cognitive, or emotional abilities lost due to injury, illness, or disability. Rehabilitation systems can include traditional therapeutic practices, as well as advanced technologies like robotic devices, virtual reality, or assistive software tailored to meet individual patient needs, used in conventional therapy or telemedicine. Besides those, another form that has emerged with new technologies is the rehabilitation with Exergames which refers to video games that require body movements or physical effort of the players to interact with the game environment and control the game mechanics, in this case, the potential applications of Exergames extend beyond the promotion of physical activity and health [6]. Studies have shown significant promise in therapeutic and rehabilitation settings, where motor skills training, balance improvement, and cognitive rehabilitation can be aided [7]. When talking about systems that use exergame in rehabilitation, it is essential to understand that, like other systems, they must have robustness and functionality characteristics to fulfill their purpose. However, it is also vital that these devices are attractive, motivating, and entertaining for patients [8]. In this regard, to determine the quality and impact of these exergame systems used in rehabilitation, the use of fundamental tools such as validation questionnaires plays a crucial role in collecting data on effectiveness, usability, and perceived user satisfaction. A validation questionnaire is a tool used to assess the reliability, validity, and usability of a specific instrument (e.g., a survey or test) in measuring a particular construct or outcome. Validation ensures that the questionnaire accurately reflects the intended attributes and performs consistently across different populations or settings. Through these instruments, valuable information is obtained that permits to objectively evaluate the performance of exergame systems in the context of rehabilitation, taking into account both standardized and non-standardized validating questionnaires to assess the system based on its evaluation purpose [9]. Ultimately, this combination of exergame and validating questionnaires strengthens the scientific basis of rehabilitation, ensuring that the devices used are effective, safe and capable of providing the best results in patient recovery.

After developing a prototype it is important to define and review whether it has the potential to be successful when used on people and one of the ways to verify this and move forward in the TRL process is through technical testing and people testing with validating questionnaires. This is because if we consider the process of interaction between the user and the equipment, the user serves as a measuring element of the functionality of the equipment and one of the mechanisms to evaluate this functionality has been the validating questionnaires.

The need for a literature review is evidenced by the fact that there is a wide variety of questionnaires in the literature and that no specific selection criteria have been identified for the choice of any of them for a particular type of rehabilitation system evaluation. There is no clear understanding of which validating questionnaires are best applicable according to the specific context of the systems developed and therefore a need has been identified to systematically review the existing literature on the subject associated with upper and lower limb rehabilitation and to build the necessary documentation that will allow future research in the area to apply the necessary questionnaires according to their specific system.

Although in some investigations the authors choose to use Ad-hoc questionnaires, in others, researchers opt to use validating questionnaires in which content, criterion, construct, concurrent, predictive, discrimination, internal consistency and reliability validity have been taken into account [10,11].

In this framework, the article, as study objectives, aims to report in a systematized way the validation criteria, the validation instruments by criteria with their measurement scale interpretation and several examples of their application. Section 2 presents the research methodology and the filtering of the information. Section 2 presents the research methodology and the filtering of the information. Section 3 presents the results in a systematized way, taking into account the validation criteria, the validating instruments with their scale measurement interpretation and the most relevant studies found in the literature. Section 4 presents a discussion of the results and Section 5 draws a conclusion regarding the subject matter covered.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design

A scoping review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) criteria (see Supplementary Materials) [12]. The scoping review process included several co-creation exercises among the authors to define the study, formulate questions, refine ideas, develop a working plan, review progress, discuss findings, and outline content for different sections. Additionally, detailed individual processes were required to identify, select, and synthesize studies related to validation instruments for evaluating systems, devices, or exergames in lower limb rehabilitation. Key stages of the review process are explicitly documented in compliance with PRISMA standards. No formal registration was performed for this review.

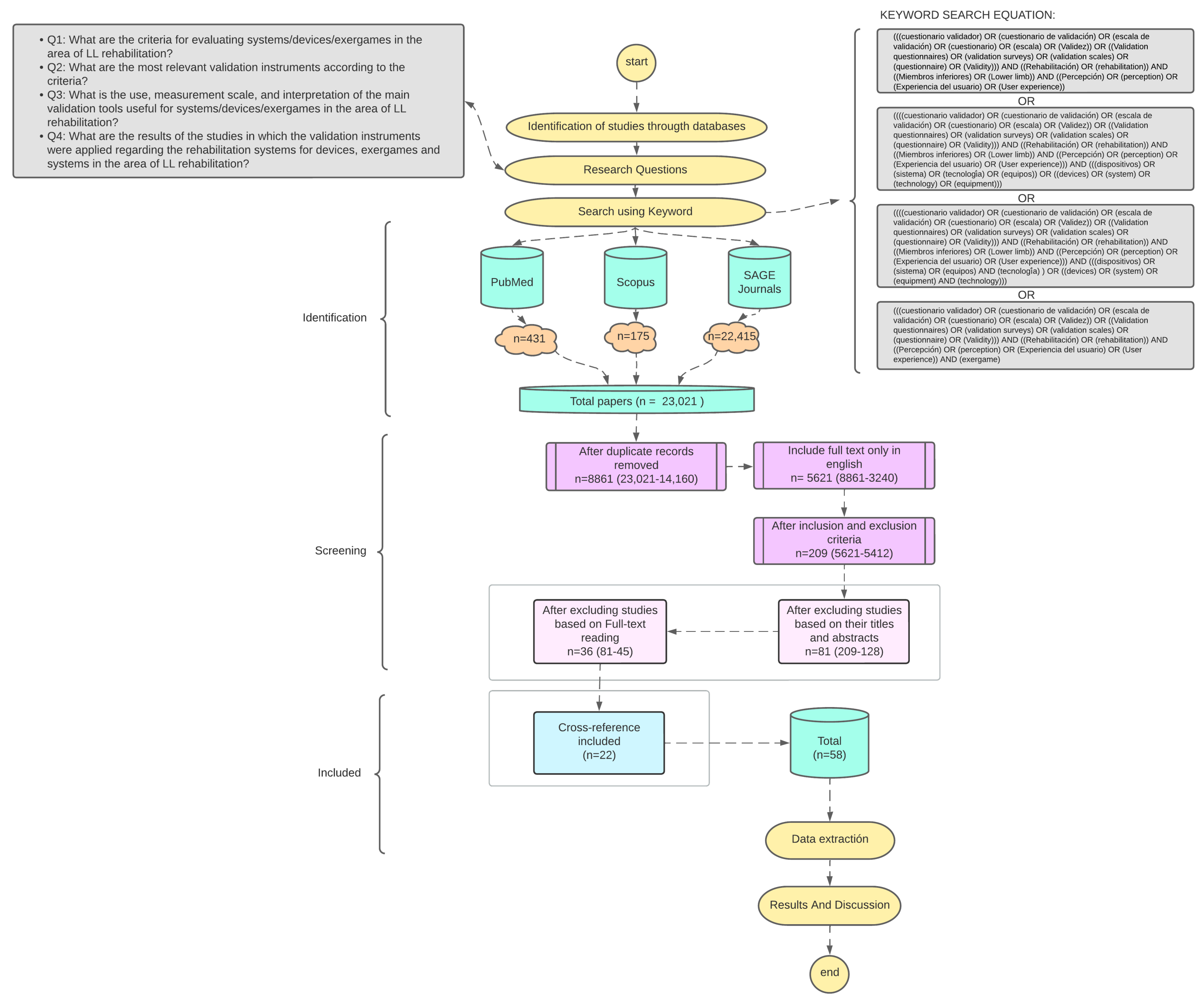

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram corresponding to the method used in this scoping review.

Figure 1.

Methodology flowchart.

2.2. Research Questions

The study’s research questions were designed through a rigorous co-creation process to directly address its objectives. Each question reflects a specific aspect of the study objectives.

Initially, based on the recent challenges faced by V.Z.P. and M.J.B in research projects on rehabilitation, the need to explore more thoroughly adequate instruments to measure performance in systems, devices, or exergames was identified. An initial co-creation exercise among the three authors resulted in a matrix of information containing preliminary ideas about specific topics to explore, known results, and potential methodologies for conducting the scoping review. At the conclusion of the co-creation exercise, research questions were addressed to guide and orient the search for validation questionnaires in the area of lower limb (LL) rehabilitation. The research questions were structured in a particular order, from general criteria to specific applications, to address the study´s objectives progressively, starting from identifying criteria (Q1, Q2) to exploring their applications and results (Q3, Q4), as follows:

- Q1: What are the criteria for evaluating systems/devices/exergames in the area of LL rehabilitation?

- Q2: What are the most relevant validation instruments according to the criteria?

- Q3: What is the use, measurement scale, and interpretation of the main validation tools useful for systems/devices/exergames in the area of LL rehabilitation?

- Q4: What are the results of the studies in which the validation instruments were applied regarding the rehabilitation systems for devices, exergames and systems in the area of LL rehabilitation?

Question Q1 is oriented and contributes to identifying specific criteria for evaluating systems, devices, and exergames in LL rehabilitation, the first study objective. Question Q2 is oriented toward finding the most relevant validation instruments to the citeria. In addition, questions Q3 seek to understand the use, measurement scale, and interpretation of validation instruments in the context of LL rehabilitation. These two questions are aligned with the second study objective. Finally, Q4 analyzes the results of previous research that applied validation instruments to specific systems, devices, or exergames used in this area of rehabilitation. It is aligned with the third study objective.

2.3. Information Sources

An exhaustive bibliographic search was conducted in electronic databases, such as PubMed, Scopus, and Sage Journal, which offer extensive coverage of scientific and medical journals, conferences, books and patents. PubMed was chosen for its focus on high-quality, peer-reviewed life sciences and biomedical articles, which are central to our research. Scopus was included due to its broad coverage of scientific disciplines, including engineering and technology, and its inclusion of conference proceedings and patents, which are essential for capturing cutting-edge developments in the field. Finally, Sage Journal was selected for its interdisciplinary approach, providing access to journals in both health and social sciences, which allows for a broader exploration of the subject matter. These three databases together offer a comprehensive range of resources, ensuring that our study is based on reliable, diverse, and up-to-date information.

2.4. Search Strategy

Four search equations were used in each database, where the following combination of keywords was used with the Boolean operators AND and OR:

- (((cuestionario validador) OR (cuestionario de validación) OR (escala de validación) OR (cuestionario) OR (escala) OR (Validez)) OR ((Validation questionnaires) OR (validation surveys) OR (validation scales) OR (questionnaire) OR (Validity))) AND ((Rehabilitación) OR (rehabilitation)) AND ((Miembros inferiores) OR (Lower limb)) AND ((Percepción) OR (perception) OR (Experiencia del usuario) OR (User experience)).

- ((((cuestionario validador) OR (cuestionario de validación) OR (escala de validación) OR (cuestionario) OR (escala) OR (Validez)) OR ((Validation questionnaires) OR (validation surveys) OR (validation scales) OR (questionnaire) OR (Validity))) AND ((Rehabilitación) OR (rehabilitation)) AND ((Miembros inferiores) OR (Lower limb)) AND ((Percepción) OR (perception) OR (Experiencia del usuario) OR (User experience))) AND (((dispositivos) OR (sistema) OR (tecnología) OR (equipos)) OR ((devices) OR (system) OR (technology) OR (equipment))).

- ((((cuestionario validador) OR (cuestionario de validación) OR (escala de validación) OR (cuestionario) OR (escala) OR (Validez)) OR ((Validation questionnaires) OR (validation surveys) OR (validation scales) OR (questionnaire) OR (Validity))) AND ((Rehabilitación) OR (rehabilitation)) AND ((Miembros inferiores) OR (Lower limb)) AND ((Percepción) OR (perception) OR (Experiencia del usuario) OR (User experience))) AND (((dispositivos) OR (sistema) OR (equipos) AND (tecnología) ) OR ((devices) OR (system) OR (equipment) AND (technology))).

- (((cuestionario validador) OR (cuestionario de validación) OR (escala de validación) OR (cuestionario) OR (escala) OR (Validez)) OR ((Validation questionnaires) OR (validation surveys) OR (validation scales) OR (questionnaire) OR (Validity))) AND ((Rehabilitación) OR (rehabilitation)) AND ((Percepción) OR (perception) OR (Experiencia del usuario) OR (User experience)) AND (exergame).

2.5. Elegibility Criteria

After the conceptual and strategic design of the study, the formulation of research questions, and the definition of objectives, inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied based on the PCC framework to ensure relevance and clarity, while focuses on exploring and mapping existing research. The eligibility criteria, outlined in Table 1, are related to the area of study and address the defined research questions.

Table 1.

Elegibility criteria.

Additionally, filters are applied to include only full-text studies in English.

2.6. Selection of Sources of Evidence

The first version of the search strategy was developed by A.D.M., and a complete analysis of these results was conducted by all authors in a co-creation session. Finally, V.Z.P. created a second version, updating the tables with new information considered important by the authors during the co-creation session, returning to the original sources. The first version consisted of three main stages: identification, selection, and inclusion. The identification stage involved performing an advanced search in the selected databases using the key terms and Boolean operators presented in Section 2.3, combining the four search equations with the OR operator. In the selection stage, duplicate documents from the three databases were eliminated. After obtaining the total number of documents, full-text filters were applied to include only English-language documents, and the results were imported into Mendeley (Version 1.19.8) for easier management and selection. Subsequently, the inclusion and exclusion criteria defined in Table 1 were applied, and the remaining documents were reviewed to exclude those that did not meet the criteria based on their titles, abstracts, and full text. Finally, in the inclusion stage, after a complete reading of the documents, relevant studies that met the criteria and were related to the research topic were included. The information from the remaining articles was recorded in tables created in Microsoft Word Professional Plus 2019.

Subsequently, all authors reviewed the information in the tables and discussed the ideas they considered useful for the discussion section. This collaborative review process allowed the authors to share perspectives, clarify points of ambiguity, and enhance the depth of analysis. Any disagreements, inconsistencies or gaps identified were addressed by revisiting the original sources and refining the information accordingly. The discussions facilitated a more robust understanding of the included studies, which contributed to a more comprehensive and well-rounded approach in interpreting the findings of the scoping review. The insights gathered from this review were critical in ensuring that the final manuscript accurately reflects the research question, inclusion criteria, and objectives of the study.

Finally, the second version of the search strategy included refinements to the table information, incorporating additional insights from the co-creation session. These refinements enhanced the clarity and coherence of the data presented in the tables, ensuring that the key findings were easier to interpret and aligned with the study’s objectives. This version has also updated the categorization of studies, removed any outdated references, and clarified the inclusion/exclusion rationale for some studies.

2.7. Data Extraction

In the data extraction process, a scoping review of 58 relevant studies related to validating questionnaires in the area of LL rehabilitation was carried out. The data collection and organization process was carried out through a careful reading of each of the selected studies, together with the use of Mendeley bibliographic management software.

The selected studies were imported into Mendeley and specific categories were created to classify the validating questionnaires found in the reading. In this way, it was possible to effectively organize the information and carry out a detailed analysis of the different questionnaires mentioned in the studies. In such a manner, the 58 studies were carefully examined, extracting and recording the relevant information in tables created in Word. The table contained the following elements: identifying number, bibliographic information, the target population of the study, objective of the study, validation instrument used, the objective of the validation instrument and identified limitations.

During the data extraction process, missing data was identified in specific variables, such as the number of items in the questionnaire, measurement scale, and interpretation of scores, as these were critical elements defined for reporting and analysis. The process for handling missing data followed two steps. (a) Identification: Missing data was flagged during the data extraction process, particularly in key fields that were essential for the analysis and comparison across studies. (b) Handling Strategies: In cases where only a small number of data points were missing, imputation was performed by estimating values based on existing data or patterns. When possible, additional data sources were consulted, such as supplementary articles using the same questionnaire or related sections within the same article, to retrieve the missing information. If missing data was substantial or critical to the analysis and could not be supplemented, the decision was made to exclude the study from the review. However, through supplementary resources, most missing data was resolved, ensuring that the sensitivity of the study remained unaffected.

2.8. Selection Process

By adding the key terms in the advanced search provided in the databases, 23,021 studies related to the research questions were identified. Afterwards, the studies obtained were reviewed and 14,160 were removed due to duplication, resulting in 8861 studies. Furthermore, only texts to which the full text was available in English were included, for a total of 5621 studies.

Later, with the studies of interest stored in the reference manager Mendeley, a review was made where inclusion and exclusion criteria presented in Table 1 were applied, where relevant studies were extracted and those that were irrelevant to the research were excluded, resulting in 209 studies.

Starting from the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a second detailed review was made based on the title and abstract, resulting in 81 studies. Then, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were used again for the full-text reading, which yielded 36 results. Finally, 22 additional references found within the studies that also met the criteria were evaluated by means of the full-text reading, resulting in 58 studies as the final result of the search.

2.9. Critical Appraisal

A.D.M. conducted a data extraction pilot testing to validate the information in the matrix. The pilot involved the following steps: (a) Selection of articles for pilot testing, ensuring they covered a range of study design, methodologies, and topics relevant to the research questions. (b) Development and testing of the Data Extraction Table, including fields for study characteristics. (c) Filled in the tables with information from the selected articles. After this exercise, the matrix and questions were refined.

2.10. Synthesis of Results

Results were synthesized using narrative synthesis to accommodate the diversity of study designs, outcomes, and criteria assessed in the included studies. This method was chosen because it allows for a qualitative summary and comparison of findings, which is suitable given the heterogeneity of the studies (e.g., various validation instruments, populations, and methodologies).

In that way, it provided in a structured, summarized and clear way the key information extracted from each study. This methodology permitted effective organization and visualization of the relevant data on the validating questionnaires used in the area of LL rehabilitation. Table 2 shows the items in each column and their description.

Table 2.

Data extraction items.

These details were important to understand the context and considerations associated with each validation instrument. Lastly, the results were presented clearly and concisely, using tables and narrative descriptions.

The exploration of heterogeneity was not applicable to this study due to the absence of a meta-analysis or subgroup analysis. The focus of this scoping review was on summarizing the findings across diverse studies rather than statistically assessing differences or causes of heterogeneity.

Similarly, sensitivity analysis was not conducted as it was not relevant to the study design. The emphasis was on qualitative synthesis and descriptive summary rather than on evaluating the robustness of specific quantitative models or results.

3. Results

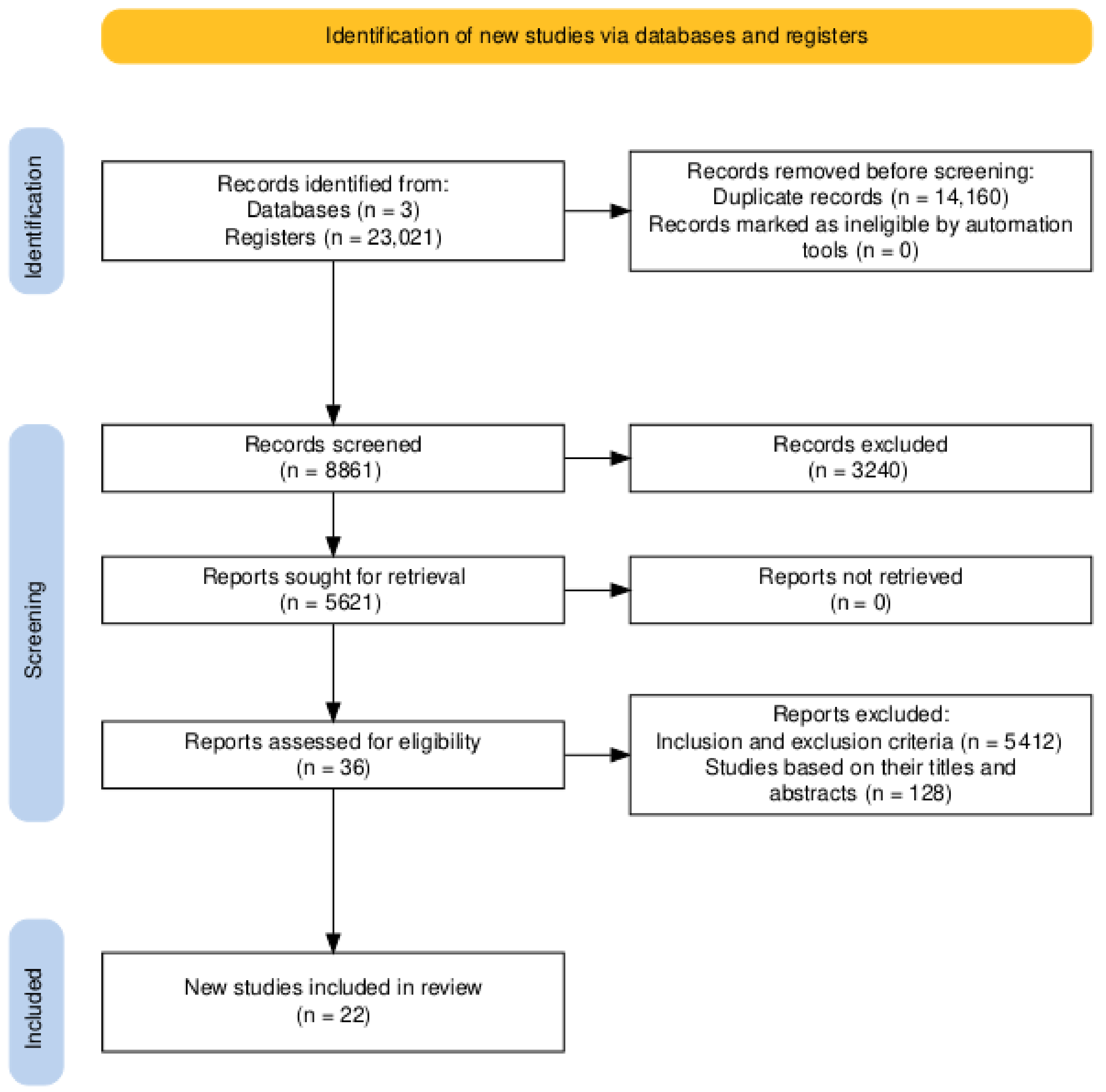

This results section uses a flow diagram developed with an online tool to describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review (see Figure 2). Additionally, it presents a synthesis of the findings of the scoping review, using tables to classify and organize the selection criteria, the validating instruments and their applications, which allows the information to be grouped, facilitating the understanding and analysis of the data. Moreover, additional information is provided to help understand and contextualize the questionnaires used in the studies.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram for the study search and selection process.

3.1. Evaluation Criteria

The criteria or categories identified in the literature are presented in Table 3, which includes the criterion, the definition of the criterion, the ad hoc questionnaires that have been used by some researchers to assess the criterion and the standardized questionnaires that have been used.

Table 3.

Criteria for validation in rehabilitation systems.

The selection criteria were obtained through a scoping review, and the results obtained were the following: gameplay, enjoyment, usability, expectation of use, motivation, satisfaction, acceptability, user experience, safety, comfort, and immersion. During this process, the different evaluation needs and purposes present in each study were analyzed. In addition, the elements that the questionnaires evaluate concerning the user’s perception were considered.

The purpose of this identification of selection criteria is to be able to determine which questionnaire is most useful in specific applications to assess user perception or experience in systems, devices or exergames utilized in the LL rehabilitation.

Table 4 details psicometric test performed for validating questionnaires, presents general aspects of validity and reliability, and amplify the context and population of studies.

Table 4.

Validity and Reliability Properties of Questionnaires.

3.2. Validation Instruments

In the present scoping review, a total of 23 validated instruments used to evaluate systems, devices or exergames in the area of lower limb (LL) rehabilitation were identified. All of these instruments focus on the user’s perception or experience of the user when interacting with these systems.

Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9 shows a compilation of the instruments found in the literature, providing important details on their use. It includes the number of items of each instrument, the measurement scale used, the interpretation of the scale and the reference where the questionnaire was proposed.

Table 5.

Validation instruments for rehabilitation systems: SUS, IMI, CEQ, SSQ, PQ, GUESS, and D-QUEST.

Table 6.

Validation instruments for rehabilitation systems: UTAUT, QFQ, Semi-structured interview, PACES, and GEQ.

Table 7.

Validation instruments for rehabilitation systems: Modified QUEST 2.0 questionnaire, IPQ, TARPP-Q, and UEQ.

Table 8.

Validation instruments for rehabilitation systems: GUESS-18, ITQ, and ITC.

Table 9.

Validation instruments for rehabilitation systems: Ad-Hoc Questionnaire, GFQ, UEQ-S, Questionnaire of Gerling et al. [14].

This table provides an organized overview of the instruments identified, which facilitates comparison and understanding. The details provided allow readers to gain a deeper knowledge of each instrument and its specific characteristics.

3.3. Application of Instruments

Table 10, Table 11, Table 12, Table 13 and Table 14 summarizes LL rehabilitation research using systems, devices or exergames in which questionnaires were used as a mechanism for validating progress. The table provides a compilation of citations of relevant research, together with the validation instruments used, the measurement results obtained using these instruments and some additional observations.

Table 10.

Lower limb rehabilitation investigations using validating questionnaires. Part 1.

Table 11.

Lower limb rehabilitation investigations using validating questionnaires. Part 2.

Table 12.

Lower limb rehabilitation investigations using validating questionnaires. Part 3.

Table 13.

Lower limb rehabilitation investigations using validating questionnaires. Part 4.

Table 14.

Lower limb rehabilitation investigations using validating questionnaires. Part 5.

Including the citation of each research, allows readers to easily track and reference relevant studies in the field of LL rehabilitation. Additionally, the validation instruments used are mentioned, which offers insight into the tools used to evaluate the progress of each research study.

The measurement results obtained through the validation instruments are presented in the table, providing a synthesis of the relevant quantitative findings in each study and reporting information on the specific tool used to assess improvements in the rehabilitation process.

Also, some additional observations are included in the table, which allows for highlighting relevant aspects or particularities of each research, providing a fuller understanding of the results obtained.

4. Discussion

This state-of-the-art review responds to the lack of explicit information identified in the literature regarding selection criteria for technology validation in LL rehabilitation. This article’s primary contribution is identifying specific evaluation criteria for systems/devices/exergames in the area of LL rehabilitation through validation instruments.

Four focus questions guided this review, covering aspects such as identifying evaluation criteria and tools, and analyzing their application and outcomes (see Section 2.2). The results of the scoping review highlight three fundamental elements: (a) Eleven evaluation criteria were identified, along with Ad-hoc and standardized instruments supported by the literature to evaluate each criterion. (b) Each selected validation instruments was presented with information on its use, measurement scale and interpretation; (c) Significant studies were analyzed, illustrating the application of instruments and evaluation criteria.

4.1. Evaluation Criteria for LL Rehabilitation Systems Using Validated Questionnaires

The review revealed a lack of systematic guidelines for selecting validation questionnaires for systems, devices, or exergames in LL rehabilitation. Despite the diversity of questionnaires reported in the literature, no standardized selection processes were evident [72]. This study addresses that gap by offering a structured proposal based on the PRISMA methodology, ensuring transparency and reproducibility [12].

This proposal, summarized in Table 3, groups questionnaires by evaluation criteria and aligns with ad-hoc and standardized categories. This framework serves as a valuable resource for researchers, simplifying the process of identifying suitable validation tools for LL rehabilitation studies. Criteria selected are gameplay, enjoyment, usability, Expectation of use, Motivation, Satisfaction, Acceptability, User Experience, Safety, Comfort, and Immersion, supported by studies of the art [73,74]. The scoping review by Nawaz et.al and Tao et.al present several criteria as parameters of their analysis, which align with our proposal [47,75].

The scoping review by Nawaz et al. presents several criteria as parameters of their analysis, which align with our proposal [47].

This proposal is a resource that facilitates the selection process of a specific questionnaire for a future application, since it allows to properly identify the use of validating questionnaires related to the evaluation purpose. This resource is intended to facilitate this selection task in projects that require validation questionnaires for systems/devices/exergames for LL rehabilitation.

Analyzing cost-benefit for ad-hoc and standardized instruments, while standardized tools have undergone rigorous psychometric testing (e.g., content, construct, and criterion validity) making them a broader acceptance in academical and clinical settings, they could have direct cost associated. Conversely, ad hoc questionnaires may be more practical but have limitations as reduced reliability and lack of generalizability. One possible use of this scoping review is that taking an overview of different tools for applications favor a good cost-benefit decision.

4.2. Validation Instruments

Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9, in this review serves as a critical resource, consolidating detailed insights about each identified instrument, including their use or application contexts, number of items, measurement scales, and interpretation guidelines. For example, SUS, with its simplicity and widespread adoption, offers a straightforward 10-item Likert scale to assess usability, making it highly compatible with both clinical and research settings [19,76]. Similarly, GUESS evaluates dimensions such as engagement and challenge in gaming contexts, which are increasingly relevant in gamified rehabilitation systems [27]. By presenting these tools with this useful information, alongside their evaluation criteria (Table 3), the process of selecting appropriate instruments for specific research objectives and compare with similar works is simplified for a researcher.

The increasing incorporation of advanced technologies, such as virtual and augmented reality, into LL rehabilitation underscores the importance of selecting instruments that can evaluate both technical and experiential dimensions. Tools like Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) are specifically designed to capture user interaction with cutting-edge technologies [29]. These instruments provide valuable feedback on how technological features influence patient engagement, motivation, and overall therapy outcomes.

Also, there are situations were a questionnaire is adapted from other, taking into account specific populations or conditions. It is the case of Modified QUEST 2.0 Questionnaire that adapts QUEST [45,77]. Other case is the GUESS-18 questionnaire that adapt to only 18 questions the instrument Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale GUESS [27]. The last example is the case of UEQ-S as a short version of User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ) [34].

The comprehensive analysis presented in this review offers researchers actionable insights for integrating the most suitable validation instruments into their projects, ensuring high-quality and impactful rehabilitation solutions.

4.3. Application of Instruments

After the selection and filtering process resulted in the identification of references that were considered applicable to systems/devices/exergames in the area of lower limb rehabilitation. In spite of the differences found among the studies regarding the definition of criteria or categories due to their specific evaluation purpose and their application, a unification has been achieved that seeks to provide usefulness for future practical work.

These research studies, detailed in Table 10, Table 11, Table 12, Table 13 and Table 14 becomes a valuable resource in this scoping review and reflect consistency with external evidence, as it shows research that includes validating questionnaires used and that aligns with the established evaluation criteria. These questionnaires address specific needs of LL rehabilitation, such as gameplay, usability, or patient engagement, especially because always this LL systems requires interaction with the user and develop of physical activity. Additionally, as it is confirmed for previous literature reviews, modern systems for LL rehabilitation every time incorporate more technological advances and topics related to virtual reality, augmented reality, and gamification, in enhancing patient motivation and interaction [78]. This references could be the base to other works in Sports or illness rehabilitation in the field of lower limb. While validation questionnaires are particularly valuable during the user interaction phase, rigorous evaluation of technical functionality remains essential, as each system possesses unique technical requirements.

4.4. Practical Guidelines for Questionnaire Selection

Researchers can benefit from the following guidelines for questionnaire selection:

- (a)

- Align questionnaires with study goals, e.g., usability, safety, patient satisfaction. (See Table 3).

- (b)

- (c)

- (d)

- Prioritize user-friendly instruments with proven psychometric properties.

- (e)

- (f)

- Integrate questionnaires that support real-time feedback and data collection, especially for systems and exergames.

- (g)

- Opt for instruments enabling longitudinal comparisons if required.

These strategies are especially critical in remote rehabilitation settings, where compatibility with telehealth platforms is necessary. In telerehabilitation, some practical implications include ensuring questionnaires can be seamlessly integrated into digital platforms or telehealth systems used in remote rehabilitation; verifying the availability of compatible devices, internet connectivity, and software adaptability; using tools that are user-friendly for both patients and clinicians in remote settings, while still addressing the need for training; and selecting questionnaires with simple formats (e.g., Likert scales or yes/no questions) to minimize technical challenges during virtual interactions.

4.5. Limitations

Implementing questionnaires poses several challenges, including a lack of infrastructure and technology, particularly in resource-limited settings. Additionally, the need for trained personnel to administer and interpret complex validation instruments adds another layer of difficulty. When questionnaires are not designed for specific populations or contexts, the absence of proper adaptation and training can lead to misuse or misinterpretation of the data, further complicating their effective implementation.

Existing questionnaires for rehabilitation systems face unique limitations. Many tools lack a specific focus on outcomes related to lower-limb rehabilitation and are mainly useful during the final stages of user interaction. In areas such as device construction, there is a need for the development of new instruments and validation studies. A promising avenue lies in the creation of hybrid tools that combine the rigor of standardized instruments with the adaptability of ad-hoc solutions. Efforts should also include strategies to address contextual barriers, such as designing validation processes for diverse populations and settings.

Cultural and linguistic misalignment of questionnaires presents significant challenges to their implementation. It was noted that some research described validated instruments but mentioned the need to adapt the questionnaires to the specific conditions of the region in which they were applied. This adaptation is crucial to ensure the validity and applicability of the questionnaires in different geographical and cultural contexts. Some recommendations to develop culturally adapted tools involve a systematic process, including translation, back-translation, involvement of bilingual experts, cultural mediation, piloting with target populations, and subsequent revalidation of psychometric properties. Addressing these steps ensures the reliability and validity of adapted questionnaires. Additionally, advancements in technology offer opportunities for digitizing tools, improving accessibility, and enhancing usability in diverse contexts.

In specific, this scoping review identifies several limitations that provide opportunities for improvement in future research. It must be mentioned that although a thorough effort was made to include as much relevant research as possible, the cut-off date for this paper restricted to studies published until May 2023 implies that some research after may not have been considered in the analysis. It is therefore recommended that future reviews take into account more recent research to obtain a more complete and up-to-date picture of the issue.

Within the systematic search, the inclusion and exclusion criteria took into account the lack of accessibility, so some studies were eliminated despite being related to the research topic, which may affect the representation of the results and the completeness of the review. For future work, it is suggested that additional effort be made to gain access to complete information to ensure a more comprehensive review.

4.6. Future Directions

Technological advancements are shaping the near future by enabling the creation of more customized and intelligent systems. Artificial intelligence combined with mechatronics systems offers a powerful toolset for the design, development, and validation of rehabilitation systems. Additionally, modern technologies have the potential to positively impact various communities and populations facing disability-related challenges.

Technological advancements will also influence questionnaire validity, particularly in the design, implementation, and validation of questionnaires within specific research contexts.

Advances in data collection have been enhanced by modern tools such as mobile apps, wearable devices, and online platforms, introducing new methods for administering questionnaires. These tools often improve accessibility and scalability but may also pose challenges, such as digital literacy barriers or variations in user interaction, which could affect validity.

Modern advancements involve the integration of various technologies, systems, and devices. In specific contexts of lower limb rehabilitation, advanced technologies such as robotics, virtual reality, and exergames have been widely adopted. In this context, questionnaires designed for these systems must address the criteria analyzed in this paper, including usability and immersion. AI-driven algorithms support adaptive questionnaires that adjust questions based on user responses. This dynamic adaptation and personalization can enhance relevance but pose challenges to traditional validation methods, likely requiring more sophisticated approaches to evaluate consistency and reliability.

5. Conclusions

This article has succeeded in identifying criteria for evaluating systems, devices or exergames in the area of LL rehabilitation through validation instruments. A compendium of selection criteria for the application of these instruments is presented, detailing the characteristics of the main instruments and providing relevant research where it has been used.

The systematic analysis conducted in this study has been supported by theory, considering both Ad-hoc and standardized questionnaires, together with the corresponding validation process. This rigorous methodology ensures a thorough and accurate evaluation of the systems and devices used in LL rehabilitation.

Moreover, the tabulated information presented in this article can be used as a reference to establish evaluation criteria, select the most appropriate instrument according to the system to be evaluated or perform a comprehensive review of the state-of-the-art in the field of LL rehabilitation. These tables provides an overview of the instruments and criteria used in previous research, facilitating comparison and analysis of the results.

The selection criteria presented in this study support the process of validating systems/devices/exergames in the area of LL rehabilitation, allowing the identification of relevant questionnaires and their characteristics, as well as comparison with other related work. Additionally, this work has contributed to overcoming some limitations identified in the literature, such as the selection process and the interpretation of questionnaires, and has mapped research using different instruments and analysing different criteria in the field of LL rehabilitation.

While it is acknowledged that there are limitations to this scoping review, such as the exclusion of research due to lack of accessibility, this study has laid the groundwork for future research in this area. Researchers are encouraged to address these limitations and further improve knowledge in the validation of systems and devices for LL rehabilitation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/sports13010004/s1. The completed checklist for the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) criteria is available as supplementary material for this paper [12].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D.M., V.Z.P. and M.J.B.; methodology, A.D.M., V.Z.P. and M.J.B.; validation, A.D.M. and V.Z.P.; investigation, A.D.M. and V.Z.P., resources, V.Z.P.; data curation, A.D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.M. and V.Z.P.; writing—review and editing, V.Z.P. and M.J.B.; visualization, A.D.M. and V.Z.P.; supervision, V.Z.P. and M.J.B.; software, A.D.M. and V.Z.P.; project administration, V.Z.P.; funding acquisition, V.Z.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Valentina Arango and Alejandro Pelaez Vargas for their valuable contributions to this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SUS | System Usability Scale |

| IMI | the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory |

| CEQ | Credibility and Expectancy Questionnaire |

| SSQ | Simulator Sickness Questionnaire |

| PQ | Presence Questionnaire |

| GUESS | Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale |

| D-QUEST | Quebec User Evaluation of Satisfaction with assistive Technology |

| UTAUT | Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology |

| QFQ | Qualitative Feedback Questionnaire |

| PACES | Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale |

| GEQ | Game Experience Questionnaire |

| IPQ | Igroup Presence Questionnaire |

| TARPP-Q | Technology Assisted Rehabilitation Patient Perception Questionnaire |

| UEQ | User Experience Questionnaire |

| ITQ | Immersive Tendencies Questionnaire |

| ITC | Sense of Presence Inventory |

| GFQ | GameFlow questionnaire |

| UEQ-S | short version User Experience Questionnaire |

References

- World Health Organization. Global Health Report 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/sensory-functions-disability-and-rehabilitation/global-report-on-health-equity-for-persons-with-disabilities (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- World Health Organization. Rehabilitation. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rehabilitation (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Koenig, A.; Member, S.; Brütsch, K.; Zimmerli, L.; Guidali, M.; Duschau-wicke, A.; Wellner, M.; Meyer-heim, A.; Lünenburger, L.; Koeneke, S.; et al. Virtual environments increase participation of children with cerebral palsy in robot-aided treadmill training. Res. Collect. Conf. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schuler, T.; Brütsch, K.; Müller, R.; Hedel, H.J.A.V.; Meyer-Heim, A. Virtual realities as motivational tools for robotic assisted gait training in children: A surface electromyography study. NeuroRehabilitation 2011, 28, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, C.Y.; Lin, K.H.; Hu, M.H.; Wu, R.M.; Lu, T.W.; Lin, C.H. Effects of virtual reality-augmented balance training on sensory organization and attentional demand for postural control in people with Parkinson disease: A randomized controlled trial. Phys. Ther. 2011, 91, 862–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staiano, A.E.; Calvert, S.L. Exergames for Physical Education Courses: Physical, Social, and Cognitive Benefits. Child Dev. Perspect. 2011, 5, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, Y.; Yang, S. Defining Exergames & Exergaming; Technical Report; University of Wisconsin: Madison, WI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mosna, P. Integrated Approaches Supported by Novel Technologies in Functional Assessment and Rehabilitation. Ph.D. Thesis, Universita Degli Studi di Brescia, Brescia, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Boynton, P.M.; Greenhalgh, T. Hands-on guide to questionnaire research Selecting, designing, and developing your questionnaire. Br. Med. J. 2004, 328, 1312–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.A.; Watson, D. Constructing Validity: New Developments in Creating Objective Measuring Instruments. Psychol. Assess. 2019, 31, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkin, T.R. A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Organ. Res. Methods 1998, 1, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahan, A.Y.; Karahan, A.Y.; Tok, F.; Taşkın, H.; Küçüksaraç, S.; Başaran, A.; Yıldırım, P. Effects of exergame on balance, functional mobility, and quality of life of geriatrics versus home exercise programme: Randomized controlled study. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 23, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerling, K.M.; Schild, J.; Masuch, M. Exergaming for Elderly: Analyzing Player Experience and Performance; Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag GmbH: Munich, Germany, 2011; pp. 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalmann, M.; Ringli, L.; Adcock, M.; Swinnen, N.; de Jong, J.; Dumoulin, C.; Guimarães, V.; de Bruin, E.D. Usability study of a multicomponent exergame training for older adults with mobility limitations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, A.; Nilsagard, Y.; Boström, K. Perceptions of using videogames in rehabilitation: A dual perspective of people with multiple sclerosis and physiotherapists. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.W.J.; Heim, W.; Fairley, K.; Clement, R.J.; Biddiss, E.; Torres-Moreno, R.; Andrysek, J. Evaluation of an instrument-assisted dynamic prosthetic alignment technique for individuals with transtibial amputation. Prosthetics Orthot. Int. 2016, 40, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medola, F.; Lanutti, J.; Bentim, C.; Sardella, A.; Franchinni, A.; Paschoarelli, L. Experiences, Problems and Solutions in Computer Usage by Subjects with Tetraplegia; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 9187, pp. 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, J. SUS: A Quick and Dirty Usability Scale System Usability Scale View Project Fault Diagnosis Training View Project. 1995. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228593520 (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- McAuley, E.D.; Duncan, T.; Tammen, V.V. Psychometric properties of the intrinsic motivation inventory in a competitive sport setting: A confirmatory factor analysis. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 1989, 60, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrow, K.S.; Heffernan, N.T. Testing the validity and reliability of intrinsic motivation inventory subscales within ASSISTments. In Artificial Intelligence in Education, Proceedings of the 19th International Conference, AIED 2018, London, UK, 27–30 June 2018; Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 10947, pp. 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devilly, G.J.; Borkovec, T.D. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2000, 31, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knippenberg, E.; Lamers, I.; Timmermans, A.; Spooren, A. Motivation, usability, and credibility of an intelligent activity-based client-centred training system to improve functional performance in neurological rehabilitation: An exploratory cohort study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balk, S.A.; Bertola, M.A.; Inman, V.W. Simulator sickness questionnaire: Twenty years later. In Proceedings of the 7th International Driving Symposium on Human Factors in Driver Assessment, Training, and Vehicle Design, Bolton Landing, NY, USA, 17–20 June 2013; Available online: https://pubs.lib.uiowa.edu/driving/article/28474/galley/136766/view/ (accessed on 25 April 2023).

- Witmer, B.G.; Singer, M.J. Measuring Presence in Virtual Environments: A Presence Questionnaire. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 1998, 7, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keebler, J.R.; Shelstad, W.J.; Google, D.C.S.; Chaparro, B.S.; Phan, M.H. Validation of the GUESS-18: A Short Version of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (GUESS). J. Usability Stud. 2020, 16, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, M.H.; Keebler, J.R.; Chaparro, B.S. The Development and Validation of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (GUESS). Hum. Factors 2016, 58, 1217–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demers, L.; Rhoda, W.L.; Bernadette, S. The Quebec User Evaluation of Satisfaction with Assistive Technology (QUEST 20): An overview of recent progress. Technol. Disabil. 2002, 14, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D.; Smith, R.H.; Walton, S.M. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a unified view user acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laura, C.; Díaz-Bravo, P.; Díaz-Bravo, L.; Torruco-García, U.; Martínez-Hernández, M.; Varela-Ruiz, M. La entrevista, recurso flexible y dinámico. Investig. Educ. Med. 2013, 2, 162–167. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, K.L. GEQ (Game Engagement/experience questionnaire): A review of two papers. Interact. Comput. 2013, 25, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlker Berkman, M.; ÇAtak, G. I-group Presence Questionnaire: Psychometrically Revised English Version. Mugla J. Sci. Technol. 2021, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundarò, C.; Casale, R.; Maestri, R.; Traversoni, S.; Colombo, R.; Salvini, S.; Ferretti, C.; Bartolo, M.; Buonocore, M.; Giardini, A. Technology Assisted Rehabilitation Patient Perception Questionnaire (TARPP-Q): Development and implementation of an instrument to evaluate patients’ perception during training. J. NeuroEng.Rehabil. 2023, 20, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrepp, M.; Hinderks, A.; Thomaschewski, J. Design and Evaluation of a Short Version of the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ-S). Int. J. Interact. Multimed. Artif. Intell. 2017, 4, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinderks, A.; Meiners, A.L.; Mayo, F.J.D.; Thomaschewski, J. Interpreting the results from the user experience questionnaire (UEQ) using importance-performance analysis (IPA). In Proceedings of the WEBIST 2019—15th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies, Vienna, Austria, 18–20 September 2019; SciTePress: Setubal, Portugal, 2019; pp. 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessiter, J.; Freeman, J.; Keogh, E.; Davidoff, J. A cross-media presence questionnaire: The ITC-sense of presence inventory. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2001, 10, 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chardonnet, J.R.; Mirzaei, M.A.; Mérienne, F. Features of the Postural Sway Signal as Indicators to Estimate and Predict Visually Induced Motion Sickness in Virtual Reality. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2017, 33, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, R.; O’Neil, S.; Carroll, F. Measuring presence in virtual environments. In Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vienna, Austria, 24–29 April 2004; pp. 783–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, S. 28 Tips for Creating Great Qualitative Surveys. 2016. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/qualitative-surveys/ (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Murrock, C.J.; Bekhet, A.K.; Zauszniewski, J.A. Psychometric Evaluation of the Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale in Adults with Functional Limitations. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2016, 37, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laugwitz, B.; Held, T.; Schrepp, M. Construction and evaluation of a user experience questionnaire. In HCI and Usability for Education and Work, Proceedings of the 4th Symposium of the Workgroup Human-Computer Interaction and Usability Engineering of the Austrian Computer Society, USAB 2008, Graz, Austria, 20–21 November 2008; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 5298, pp. 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.K.; Basford, J.R.; Heinemann, A.W.; Cheville, A. Assessing whether ad hoc clinician-generated patient questionnaires provide psychometrically valid information. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, F.L.; Su, R.C.; Yu, S.C. EGameFlow: A scale to measure learners’ enjoyment of e-learning games. Comput. Educ. 2009, 52, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo, A.; Castrillo, A.; López, C.; Perea, L.; Alnajjar, F.; Moreno, J.; Raya, R. PedaleoVR: Usability study of a virtual reality application for cycling exercise in patients with lower limb disorders and elderly people. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kablan, N.; Bakhsh, H.; Alammar, W.; Tatar, Y.; Ferriero, G. Psychometric Evaluation of the Arabic Version of the Quebec User Evaluation of Satisfaction with Assistive Technology (A-QUEST 2.0) in Prosthesis Users. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2022, 58, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dijsseldonk, R.; van Nes, I.; Geurts, A.; Keijsers, N. Exoskeleton home and community use in people with complete spinal cord injury. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawaz, A.; Skjæret, N.; Helbostad, J.L.; Vereijken, B.; Boulton, E.; Svanaes, D. Usability and acceptability of balance exergames in older adults: A scoping review. Health Inform. J. 2016, 22, 911–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, S.; Jiménez, M.; Múnera, M.; Frizera-Neto, A.; Cifuentes, C. Remote-Operated Multimodal Interface for Therapists during Walker-Assisted Gait Rehabilitation: A Preliminary Assessment. In Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Daegu, Republic of Korea, 11–14 March 2019; Volume 2019, pp. 528–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothgangel, A.; Braun, S.; Smeets, R.; Beurskens, A. Feasibility of a traditional and teletreatment approach to mirror therapy in patients with phantom limb pain: A process evaluation performed alongside a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2019, 33, 1649–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qiu, J.; Cheng, H.; Wang, L. A Prospective Study of Haptic Feedback Method on a Lower-Extremity Exoskeleton; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 12786, pp. 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puyuelo-Quintana, G.; Cano-De-La-Cuerda, R.; Plaza-Flores, A.; Garces-Castellote, E.; Sanz-Merodio, D.; Goñi-Arana, A.; Marín-Ojea, J.; García-Armada, E. A new lower limb portable exoskeleton for gait assistance in neurological patients: A proof of concept study. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2020, 17, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, V.; Yepes, J.; Vargas, J.; Franco, J.; Escobar, N.; Betancur, L.; Sánchez, J.; Betancur, M. Virtual Reality Game for Physical and Emotional Rehabilitation of Landmine Victims. Sensors 2022, 22, 5602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, M.; Kinany, N.; Rinne, P.; Rayner, A.; Bentley, P.; Burdet, E. Balancing the playing field: Collaborative gaming for physical training. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2017, 14, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhu, B.; Fan, Y.; Wu, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Yao, L.; Sun, Y.; Su, B.; Ma, Z. Design and evaluation of an exergame system to assist knee disorders patients’ rehabilitation based on gesture interaction. Health Inf. Sci. Syst. 2022, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenk, M.; Sabbagh, M.; Lin, I.; Morgan, P.; Grewal, G.S.; Mohler, J.; Coon, D.W.; Najafi, B. Sensor-based balance training with motion feedback in people with mild cognitive impairment. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2016, 53, 945–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenk, M.; Grewal, G.S.; Honarvar, B.; Schwenk, S.; Mohler, J.; Khalsa, D.S.; Najafi, B. Interactive balance training integrating sensor-based visual feedback of movement performance: A pilot study in older adults. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2014, 11, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugueta-Aguinaga, I.; Garcia-Zapirain, B. Frailty level monitoring and analysis after a pilot six-week randomized controlled clinical trial using the FRED exergame including biofeedback supervision in an elderly day care centre. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Xiong, S. A dynamic time warping based algorithm to evaluate Kinect-enabled home-based physical rehabilitation exercises for older people. Sensors 2019, 19, 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringgenberg, N.; Mildner, S.; Hapig, M.; Hermann, S.; Kruszewski, K.; Martin-Niedecken, A.L.; Rogers, K.; Schättin, A.; Behrendt, F.; Böckler, S.; et al. ExerG: Adapting an exergame training solution to the needs of older adults using focus group and expert interviews. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2022, 19, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdivia, S.; Blanco, R.; Uribe-Quevedo, A.; Penuela, L.; Rojas, D.; Kapralos, B. Development and evaluation of two posture-tracking user interfaces for occupational health care. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2018, 10, 1687814018769489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, T.H.; Tseng, K.C.; Wong, A.M.; Chang, H.J. A study exploring the usability of an exergaming platform for senior fitness testing. Health Inform. J. 2020, 26, 963–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorado, J.; del Toro, X.; Santofimia, M.J.; Parreño, A.; Cantarero, R.; Rubio, A.; Lopez, J.C. A computer-vision-based system for at-home rheumatoid arthritis rehabilitation. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2019, 15, 1550147719875649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baluz, R.; Teles, A.; Fontenele, J.E.; Moreira, R.; Fialho, R.; Azevedo, P.; Sousa, D.; Santos, F.; Bastos, V.H.; Teixeira, S. Motor Rehabilitation of Upper Limbs Using a Gesture-Based Serious Game: Evaluation of Usability and User Experience. Games Health J. 2022, 11, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plow, M.; Finlayson, M. A qualitative study exploring the usability of nintendo wii fit among persons with multiple sclerosis. Occup. Ther. Int. 2014, 21, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Mann, J.; Mansfield, A.; Wang, R.H.; Harris, J.E.; Taati, B. Investigating the feasibility and acceptability of real-time visual feedback in reducing compensatory motions during self-administered stroke rehabilitation exercises: A pilot study with chronic stroke survivors. J. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. Eng. 2019, 6, 205566831983163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, C.; Tudella, E.; Rocha, N.; de Campos, A. Lower Limb Sensorimotor Training (LoSenseT) for Children and Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy: A Brief Report of a Feasibility Randomized Protocol. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2021, 24, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, D.; Clarkson, C. Effects of moving cupping therapy on hip and knee range of movement and knee flexion power: A preliminary investigation. J. Man. Manip. Ther. 2019, 27, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmer, S.E.; Pearce, G.; Whittall, J.; Quinlivan, R.C.; Patrick, J.H. The use of stock orthoses to assist gait in neuromuscular disorders: A pilot study. Prosthetics Orthot. Int. 2006, 30, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.Q.; Du, D.; Wei, X.Y.; Tong, R.K.Y. Augmented reality for stroke rehabilitation during COVID-19. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2022, 19, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, R.M.; Gianoudis, J.; Hall, T.; Mundell, N.L.; Maddison, R. Feasibility, usability, and enjoyment of a home-based exercise program delivered via an exercise app for musculoskeletal health in community-dwelling older adults: Short-term prospective pilot study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2021, 9, e21094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.H.; Liu, K.H.; Kajihara, H.; Lien, W.C.; Chen, P.T.; Hiyama, A.; Lin, Y.C.; Chen, C.H.; Inami, M. Designing a Somatosensory Interactive Game of Lower Extremity Muscle Rehabilitation for the Elderly. In Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population. Supporting Everyday Life Activities, Proceedings of the 7th International Conference, ITAP 2021, HCII 2021, Virtual Event, 24–29 July 2021; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 12787, pp. 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Rong, X.; Luo, H. Optimizing lower limb rehabilitation: The intersection of machine learning and rehabilitative robotics. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2024, 5, 1246773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaklouk, A.M.; Zin, N.A.M. Design and Usability Evaluation of Rehabilitation Gaming System for Cognitive Deficiencies. In Proceedings of the 2017 6th International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Informatics (ICEEI), Langkawi, Malaysia, 25–27 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Born, F.; Abramowski, S.; Masuch, M. Exergaming in VR: The Impact of Immersive Embodiment on Motivation, Performance, and Perceived Exertion. In Proceedings of the 2019 11th International Conference on Virtual Worlds and Games for Serious Applications (VS-Games), Vienna, Austria, 4–6 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, G.; Garrett, B.; Taverner, T.; Cordingley, E.; Sun, C. Immersive virtual reality health games: A narrative review of game design. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2021, 18, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.R. The System Usability Scale: Past, Present, and Future. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2018, 34, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessels, R.D.; Witte, L.P.D. Reliability and validity of the Dutch version of QUEST 2.0 with users of various types of assistive devices. Disabil. Rehabil. 2003, 25, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staiano, A.E.; Flynn, R. Therapeutic Uses of Active Videogames: A Systematic Review. Games Health J. Res. Dev. Clin. Appl. 2014, 3, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).