Simple Summary

The vast majority of insects reproduce bisexually, and unisexual species that reproduce via parthenogenesis comprise a negligible fraction of all species. To date, very little is known about the evolutionary potential of parthenogenesis, and there remains little research related to this topic. Parthenogenetic lineages are generally considered short-lived on an evolutionary scale. It is believed that the evolutionary potential of parthenogenetic species is low due to the lack of mechanisms to counteract the effects of accumulation of deleterious mutations, which may explain the observed low incidence of parthenogenetic species among Insecta. Our study fills this gap by analysing over 5000 specimens of Cacopsylla ledi using an integrative approach that combines molecular and cytogenetic methods, as well as Wolbachia screening. We determined the reproductive mode of psyllids using cytogenetic methods, conducted phylogeographic analysis based on almost 1000 barcoded specimens, and screened specimens for Wolbachia infection by amplifying three Wolbachia-specific genes. We demonstrate that apomictic triploid parthenogenesis is not necessarily an evolutionary dead end but can lead to the emergence of a new bisexual species and that Wolbachia infection can play a significant role in this process.

Abstract

The psyllid genus Cacopsylla comprises mainly bisexually reproducing species; however, some members of this genus exhibit a unisexual mode of reproduction. Using an integrative approach that combines molecular and cytogenetic methods, as well as Wolbachia screening, we conducted a comprehensive study of the Palaearctic species C. ledi. We show that this species uses various reproductive strategies (bisexual and parthenogenetic) across its distribution range. Our findings indicate that the bisexual mode of reproduction has emerged at least twice in the evolutionary history of C. ledi. Bisexual populations in southern Fennoscandia are of ancestral origin, whereas the bisexual mode of reproduction observed in northern Fennoscandia represents a recent secondary transition from parthenogenesis. We report that in the first case, parthenogenetic and bisexual lineages can be easily distinguished not only cytogenetically but also by DNA barcoding, while in the second case, “bisexual” individuals share DNA barcodes with parthenogenetic ones. A comprehensive Wolbachia screening (1140 specimens across the entire distribution range) revealed Wolbachia infection in every specimen of C. ledi, indicating a significant role of the endosymbiont in the biology and evolution of this species.

1. Introduction

Psyllids (Hemiptera, Psylloidea), or jumping plant lice, include more than 4000 described species, most of which are monophagous or oligophagous and feed on plant sap [1]. In the superfamily Psylloidea, the genus Cacopsylla Ossiannilsson, 1970 is one of the largest and includes about 460 taxa with a predominantly Holarctic distribution [2,3,4]. The vast majority of Psylloidea species reproduce bisexually. However, recent studies have clearly shown that some Cacopsylla species can reproduce by thelytoky, a form of parthenogenesis in which females produce all-female progeny from unfertilized eggs [5,6,7,8,9].

Thelytokous parthenogenesis can be apomictic (apomixis) or automictic (automixis). In apomictic parthenogenesis, females undergo modified meiosis, resulting in offspring developing from unfertilized but diploid eggs. This mode of reproduction is strictly clonal, and populations consist exclusively of females. Apomictic parthenogenesis is usually associated with polyploidy [10,11]. In automictic parthenogenesis, females undergo normal meiosis to produce haploid gametes, but diploidy is then restored through various mechanisms [10,12,13].

In the genus Cacopsylla, the best-documented parthenogenetic species are C. borealis Nokkala et Nokkala, 2019, C. myrtilli (Wagner, 1947), and C. ledi (Flor, 1861). The recently described C. borealis [14] is the only known pentaploid jumping plant louse with apomictic females (males were not found) exhibiting the karyotype of 2n = 5x = 60 + XXXXX. Another well-studied apomictic species is C. myrtilli, which has been analysed using both cytological and molecular approaches [5,6,7,15,16,17]. Most populations of C. myrtilli consist exclusively of triploid females (2n = 3x = 36 + XXX), although rare diploid females (2n = 24 + XX) and rare males (2n = 24 +X) are occasionally found. These rare diploids are believed to be produced de novo in each generation by apomictic females as a reversion from triploidy. Rare males are non-functional, have aberrant meiosis and are unable to produce viable haploid sperm and, hence, euploid offspring. Molecular studies revealed several populations in Finland and Russia where males exhibit normal meiosis [7,16]. In these populations, diploid females and males possess distinct mitochondrial haplotypes that are not found in parthenogenetic females. This finding highlights the evolutionary potential of parthenogenesis as a driver of speciation: if males produced by parthenogenetic females become functional, then mating with diploid females can result in a new bisexual lineage reproductively isolated from its parthenogenetic ancestor, potentially leading to speciation [14,16].

Cacopsylla ledi inhabits the boreoalpine zone of the Holarctic [18], develops, lives and feeds on Ledum palustre L. 1953 (=Rhododendron tomentosum Harmaja, 1990) (Figure 1), and its distribution range matches that of its host plant.

Figure 1.

Cacopsylla ledi immature individual (left) and adult females (right) on the host plant (Ledum palustre). Russia, Murmansk Oblast, 10 km W of Kandalaksha town, 67.157280° N, 32.150402° E. 20 July 2024. Photos: G.N. Shapoval.

Recent cytological and molecular studies [8,9] have identified two evolutionary lineages of C. ledi with different reproductive strategies: the ancestral bisexual lineage and the parthenogenetic lineage. The parthenogenetic lineage is mainly represented by triploid females (2n = 3x = 36 + XXX), although rare males and diploid females have been observed in some populations. Unlike C. myrtilli, rare males of C. ledi produce normal sperm and are therefore considered functional. The bisexual lineage of C. ledi either forms mixed populations with the parthenogenetic lineage, or, which is less common, exists as completely bisexual populations. These findings suggest a complex interaction between the reproductive modes and the evolutionary history of C. ledi.

Recent studies have discovered the presence of Wolbachia infection in several Cacopsylla species, suggesting an essential role of this bacterium in their biology. It is well known, that Wolbachia has diverse impacts on its hosts. In particular, Wolbachia can skew the sex ratio towards females [19], induce parthenogenesis [20] and significantly affect mtDNA diversity in hosts [21,22,23]. At the intraspecific level, Wolbachia can reduce mtDNA polymorphism: when an endosymbiont invades a new host population, the frequency of mitochondrial haplotypes associated with Wolbachia increases due to the so-called ‘hitch-hiking’ effect. If infection has occurred recently on an evolutionary scale, mtDNA diversity within the host species may decrease significantly [22,24,25]. At the interspecific level, Wolbachia can cause mitochondrial introgression between closely related species, leading to the fixation of alien mtDNA haplotype (-s) in host populations [23,25,26,27,28,29].

The aim of our study was to conduct a large-scale phylogeographic analysis of C. ledi with the following objectives: (1) to identify the genetic structure of this species using the mitochondrial molecular marker COI and comprehensive taxon sampling, (2) to determine the overall distribution pattern of populations with different reproductive strategies in Fennoscandia, (3) to gain new insights into the evolutionary history, diversification and post-glacial dispersal of this species.

Another objective was to study the incidence and prevalence of Wolbachia in C. ledi, analyse the impact of endosymbiont on the mtDNA diversity of its host, and determine whether the parthenogenetic and bisexual patterns observed in this species are associated with Wolbachia infection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Taxon Sampling

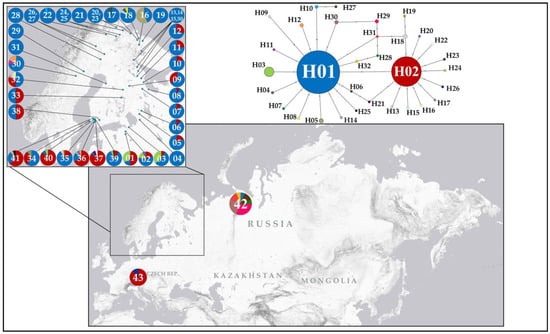

Psyllids were collected from various regions of the Palaearctic, with a particular focus on Fennoscandia, during field expeditions conducted between 2007 and 2025. In total, C. ledi individuals were sampled from 50 populations: 22 in Russia, 22 in Finland, 3 in Norway, 2 in Sweden, 1 in the Czech Republic (Figure 2, Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). Attempts to locate C. ledi in several regions in eastern Russia (Zabaykalsky Krai, Republic of Yakutia, Magadan Oblast), as well as earlier attempts to detect this species in northern Finland, where it is replaced by closely related sympatric species C. borealis [9], were unsuccessful despite the abundance of the host plant (Ledum palustre). Immediately after capture, individuals were preserved in either 96% ethanol or a 3:1 fixative solution (96% ethanol: glacial acetic acid) and stored for subsequent genetic analyses and cytological studies. Alternatively, for chromosomal and DNA analyses of the same specimens, live individuals were transported to the laboratory and dissected. For each specimen, the abdomen was placed in fixative (chromosomal preparations are made from testes) and the remainder of the body was preserved in 96% ethanol.

Figure 2.

Map showing the sampling localities of Cacopsylla ledi across the study area.

2.2. Cytological Studies

Cytological analysis was performed following previously described protocols [5]. For specimens collected in ethanol, the method first applied by Nokkala et al. [6] was used, which allows chromosomal and molecular analyses from the same individual. Chromosomal preparations were made, stained, and photographed according to Nokkala et al. [6,7,8,14].

2.3. DNA Extraction

Whole specimens or the head and thorax of individual specimens were used for DNA extraction using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocols and the CTAB-based method [30] with modifications [31,32,33]. Samples were processed at the Department of Biology, University of Turku (Finland) and the Department of Karyosystematics, Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences (St. Petersburg, Russia).

2.4. mtDNA PCR and Sequencing

Fragments of 655 bp and 725 bp in length of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene were amplified using the primer pairs HybCacoCO/HybHCOMod [8] and CACF/CACR [34], respectively. PCR was performed under conditions previously described [7,8,14,34]. PCR products were purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) or treated with FastAP and ExoI enzymes (Thermofisher, Waltham, MA, USA), and then sent for sequencing to either Macrogen Europe (Amsterdam, The Netherlands) or Evrogen (Moscow, Russia). The obtained COI sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers PX465190-PX465303, PX468288-PX468487, PX502613-PX503209, PX600319-PX600326, PX632653-PX632667. For further analysis, we used COI alignment that was trimmed to the length of the shortest sequence (655 bp). Maximum parsimony haplotype network was reconstructed to illustrate the relationships among COI haplotypes using TCS algorithm [35] implemented in PopART [36]. General sequence information was analysed and neutrality tests were performed using MEGA v.7.0.14 [37] and DnaSP v.6.12.03 [38] software.

2.5. Detection of Wolbachia Endosymbionts

To screen C. ledi specimens for Wolbachia infection, we amplified three Wolbachia-specific genes: 16S ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA), Wolbachia surface protein (wsp), and filamentation temperature-sensitive protein Z (ftsZ). We used the following primer pairs: W-Specf/W-Specr [39], wsp81F/wsp691R [40], and ftsZ-F/ftsZ-R [41], amplifying ~396 bp fragment of the 16S rRNA gene, ~549 bp fragment of the wsp gene, and ~510 bp fragment of the ftsZ gene, respectively (actual fragments sizes may vary depending on the Wolbachia strain). PCR conditions and thermal profiles were as previously described [17,33]. To determine Wolbachia presence or absence, PCR products were visualised and checked on a 1% agarose gel. For each specimen, PCR was performed twice to minimise the risk of technical error. Samples that yielded products of the expected sizes for the selected genes were considered Wolbachia-positive.

To identify the Wolbachia allele(s) infecting C. ledi, a 549 bp fragment of the wsp gene was sequenced for selected specimens. Samples, for which standard Sanger sequencing revealed intra-individual allele polymorphism (in the form of single nucleotide heterogeneities), suggesting co-infection with genetically different Wolbachia alleles, were subsequently cloned. The cloning procedure followed the previously described protocols [42,43]. Ten clones of the wsp gene per specimen were sequenced. Sequencing of the double-stranded product was performed using an ABI 3500xL analyser (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) at the Research Resource Center for Molecular and Cell Technologies (St. Petersburg State University, St. Petersburg, Russia). The obtained wsp sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers PX647420-PX647462.

3. Results

3.1. Haplotype Diversity

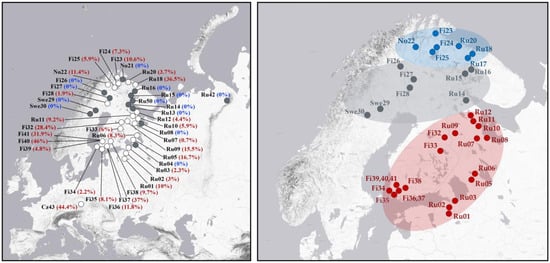

Haplotype analysis of the dataset comprising 925 specimens revealed 32 closely related COI haplotypes (H01–H32) (Figure 3), with a maximum p-distance of 0.92% (±0.35%) (Table 1). Each haplotype differed from its nearest neighbour by no more than two nucleotide substitutions. The haplotype network exhibited a star-like topology, with two major haplotypes (H01 and H02) forming a centre separated by a single nucleotide substitution (A→T at position 205 of the analysed fragment). These two major haplotypes were the most frequent, together accounting for 92.5% of all specimens analysed, and exhibited broad geographical distribution. Haplotype H02 was found in 255 specimens across 22 of the 44 genetically studied localities. Haplotype H01 was recovered in 601 specimens and occurred in all sampled localities, except for the population from the Czech Republic. A third common haplotype, H03, was found in 24 specimens from six populations, all geographically restricted to southern Finland and the Leningrad Oblast (northwestern Russia). Of the 32 haplotypes identified, 28 were private (i.e., found in only one locality), and 21 of these were “singletons” (i.e., found in only a single individual). Fu and Li’s D* test yielded a significantly negative value (−7.42374; p < 0.02) (Table 1), indicating an excess of singleton haplotypes, which may suggest recent population expansion or purifying selection. Detailed data on haplotype diversity, their distribution across specimens, and their geographical occurrence are given in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3.

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution of COI haplotypes and a haplotype network illustrating the relationships among the revealed COI haplotypes. Mutations are shown as one-step edges.

Table 1.

Summary of the mitochondrial haplotype diversity. The number of sequenced individuals (N), number of revealed haplotypes (H), number of polymorphic sites (S), nucleotide (π) and haplotype (h) diversity are given. Tajima’s D, Fu and Li’s D, Fu and Li’s F, Fu’s Fs, the max. p-distance values with standard deviations (in parentheses) are shown.

Table 2.

Composition of revealed COI haplotypes (n—number of individuals sharing a given haplotype, Sn—number of sampling sites, in which the haplotype was found).

Table 3.

Geographical distribution of revealed COI haplotypes. H—number of haplotypes found in a sampling site; Sn—number of sampling sites, in which a certain number of haplotypes (H) was found.

Haplotype diversity among the populations was generally low. In most localities, only one haplotype (found at 16 sampling sites out of 44 studied) or two haplotypes (found at 14 sites out of 44 studied) were detected (Table 3 and Figure 3). Moderate haplotype diversity was observed in populations located in southern Finland, central Sweden, the Leningrad Oblast and the Russian High North (Murmansk), where 3 to 5 different haplotypes were found in each locality. A relatively high haplotype diversity was recovered only in two geographically distant populations from central Finland (Fi32, six haplotypes) and Vorkuta (Ru42, seven haplotypes). The distribution of haplotypes showed a clear geographical pattern: haplotypes were either widespread across a large area or confined to one or more neighbouring localities.

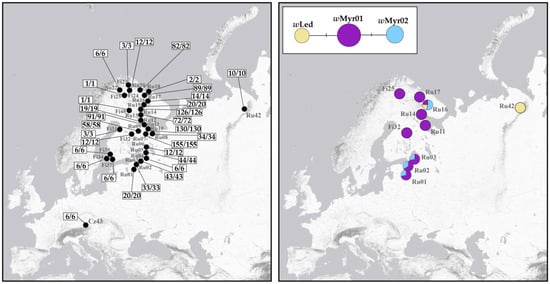

3.2. Sex Ratio in Populations

A total of 5350 specimens were included in the sex-ratio analysis. Overall, the sex ratio is strongly biased towards females, with 89.3% of all analysed individuals being females. However, the proportion of males varied significantly among populations, ranging from 0% to 46% depending on the geographical region (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S3), suggesting the presence of different reproductive strategies in this species. Males were found in 31 of the 50 populations examined. The highest male frequencies—approaching parity with females—were observed in populations from the Czech Republic (44.4%), southern Finland (32–46%), and the Russian High North (Murmansk, 36.5%) (Figure 4). Moderate male frequencies (2–16%) were recorded in several populations from northwestern Russia (the Leningrad Oblast, southern Karelia and the northern Murmansk Oblast), as well as in southern and northern Finland and northern Norway. In contrast, all-female populations or populations with single males were found predominantly in Fennoscandia between latitudes 66° and 68° N (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Maps showing male frequency in the studied populations of C. ledi (left) and the estimated distribution of two bisexual and all-female populations (right). Grey and white circles indicate all-female and mixed populations, respectively. Sampling sites where fewer than five specimens were collected are not shown. Male frequencies (in %) are given in brackets. The estimated distribution of ancestral and recently derived bisexual lineages is highlighted in red and blue, respectively; the distribution of all-female populations is highlighted in grey.

3.3. Wolbachia Infection

A total of 1140 specimens (1059 females, 80 males, and 1 immature individual) from 32 populations across Fennoscandia, northwestern Russia, and the Czech Republic were tested for the presence of Wolbachia infection (Figure 5). Of these, 1050 specimens were screened in the present study, 90 specimens were analysed earlier [17]. Overall, all 1140 specimens were positive for Wolbachia, indicating a 100% prevalence.

Figure 5.

Maps showing Wolbachia prevalence (left) and the geographical distribution of identified Wolbachia wsp alleles (right) in C. ledi. Numbers represent the ratio of infected specimens (before slash) to analysed specimens (after slash) for each population. Haplotype network illustrating the relationships among the revealed Wolbachia wsp alleles is given. Mutations are shown as one-step edges.

We analysed 44 sequences of a Wolbachia wsp gene fragment (549 bp) obtained in this study (31 samples) and in previous studies (13 samples, GenBank accession numbers MZ684119-MZ684131) (Supplementary Table S4). Sequencing revealed three different wsp alleles (wMyr01, wMyr02, and wLed) among samples representing ten localities. All three alleles were reported in Cacopsylla earlier [17]. The wMyr01 and wMyr02 alleles differ by a single nucleotide substitution (A→G transition at position 498 of the 549 bp wsp gene fragment), while the wLed allele differs from the most common wMyr01 allele in a G→C transversion at position 499. The geographical distribution of these alleles is shown in Figure 5.

The wMyr01 allele is widespread across Fennoscandia and NW Russia, being found in nine of the ten localities analysed. The wMyr02 allele was detected in four populations: in one from the Russian High North (Ru16) and in three from the Leningrad Oblast (Ru01, Ru02, and Ru03). In the north (Ru16), the wMyr02 allele occurred as a single infection in specimens with haplotype H05, whereas individuals with haplotype H01 always carried three alleles (wMyr01, wMyr02, and wLed), indicating multiple Wolbachia infection. This infection pattern was also found in all analysed specimens of C. borealis from this locality (our unpublished data). In the south (Ru01-Ru03), the wMyr02 allele has never been observed in the parthenogenetic specimens with haplotype H01. It was found exclusively in “bisexual” specimens with haplotypes H02 and H03, which were always combined with the wMyr01 allele, suggesting a double infection. The third allele, wLed, was found in two geographically remote populations. In the population Ru42 (Vorkuta), it appeared as a single infection, whereas in the population Ru16 (Russian High North), it occurred in each individual along with two other alleles, wMyr01 and wMyr02.

3.4. Cytological Analysis of Ploidy Level and Its Relationship with COI Haplotypes

We determined the ploidy of females in five populations with varying frequencies of males. In a population from the Russian High North (Ru18, male frequency 36.46%), all 30 examined females were diploid, each showing 13 bivalents (12AA + XX). These females carried either the main haplotype H01 (27 individuals), or one of its singleton derivatives: H07, H08, or H09. Additionally, three males from a nearby locality (Ru20) were examined. All of them showed normal meiosis and produced functional sperm, confirming their potential for successful mating with diploid females. In another population from southern Finland (Fi37) with an equally high male frequency (37.02%), 42 out of the 43 analysed females were diploid. They carried the second main haplotype H02 (40 individuals) or one of its singleton satellites, H21 or H22. Interestingly, the only triploid female found in this population (with 39 univalent chromosomes (36A + XXX)) carried the main haplotype H01, which is common among diploid females in Ru20. These findings suggest that both populations are of bisexual origin, although rare parthenogenetic triploid females may occur within such populations, as observed in Fi37. In the population with a moderate male frequency (13.90%) from southern Finland (Fi41b), both triploid and diploid females were present, with diploids predominating.

All diploid females carried the main COI haplotype H02 (24 individuals), whereas triploid females carried either the main haplotype H01 (14 individuals) or its singleton derivative H25. In two populations with a relatively low frequency of males—from northern Finland (Fi25, 5.88%) and southern Finland (Fi35, 8.06%)—both diploid and triploid females were observed, with triploids strongly dominating the population structure. However, in the population from northern Finland (Fi25), both diploid and triploid females shared the haplotype H01. In contrast, in southern Finland (Fi35), they carried different main haplotypes: all triploid females (26 individuals) had the haplotype H02, while diploid females carried either H02 (five individuals), or its singleton derivative H19 (see Table 4). The cytological data we obtained demonstrate a strong correlation between the ploidy level of females and the frequency of males in C. ledi populations and suggest that the analysed populations from southern (Fi35, Fi41) and northern (Fi25) Finland are of mixed origin and comprise both bisexual and parthenogenetic lineages.

Table 4.

Proportions of triploid (3n) and diploid (2n) females, and their correlation with revealed COI haplotypes in five examined populations. The number of individuals sharing a given haplotype is given in brackets.

4. Discussion

In this study, we employed an integrative approach that combines molecular, cytogenetic and phylogeographic data to study population structure, reproductive strategies, evolutionary history, Wolbachia diversity and infection patterns of the widespread psyllid species Cacopsylla ledi.

4.1. Phylogeographic Patterns Depending on the Mode of Reproduction

The haplotype network analysis of mitochondrial DNA barcodes recovered a star-like topology (Figure 3), known to be characteristic of recent population expansions of the species, likely reflecting the processes of recolonization after the last glacial maximum. A similar genetic structure with two widespread main haplotypes and a number of satellite haplotypes was previously identified in C. myrtilli [16]. Notably, most haplotypes detected in C. ledi were singletons. Such a network structure (the main haplotype (-es) with numerous singleton satellites) is a frequently observed phenomenon in insects [44,45,46]. The two main haplotypes, H01 and H02, were the most common and widespread, although their distribution was not uniform. The haplotype H01 was found throughout the studied area, except for one population in southern Bohemia (Cz43). In contrast, the haplotype H02 was confined to southern and central Fennoscandia, southern parts of northwestern Russia, and it was also found in a geographically remote locality in the Czech Republic (Červené Blato) (Figure 3). This haplotype reaches a latitude 65–66° N, not spreading further north. Despite extensive sampling in Scandinavia and northwestern Russia, no specimens carrying the H02 haplotype were found north of latitude 65.62° N. In general, C. ledi exhibits a low haplotype diversity. Four or more haplotypes were found in only a few localities restricted to narrow zones in the eastern part of central Finland, southern Finland, and the northern Murmansk Oblast (Russia) (Table 3). These haplotypes are mainly found in single individuals, being deviant variants that are not fixed in populations. This pattern suggests a recent and relatively rapid expansion of C. ledi in Fennoscandia, most likely associated with post-glacial recolonization. Interestingly, in the closely related species C. myrtilli, a much higher haplotype diversity (six to nine haplotypes) has been observed in some parts of Fennoscandia, especially in Wolbachia-free populations from southern Norway [16].

Recent studies [8,16] have demonstrated that C. ledi has a complex population structure. In southern Fennoscandia, the bisexual lineage has an ancestral origin, as indicated by its unique mitochondrial haplotype, which is not found in the parthenogenetic lineage. In contrast, the bisexual lineage found in northern Fennoscandia probably arose because of recent secondary transition (reversion) from parthenogenesis. Our data confirm this conclusion by shaping the distribution of lineages with different reproductive modes across Fennoscandia and northwestern Russia. We found that all-female populations predominantly occupy a relatively narrow zone of Fennoscandia between latitudes 66–68° N (Figure 4). In addition, males were not detected in populations from northern Norway (No21), southern Karelia (Ru08), and the northern Leningrad Oblast (Ru04). These results may reflect either a mosaic distribution of fully parthenogenetic populations or be the result of an insufficient sampling. The latter seems likely, especially for the Karelian population (Ru08), where only 18 female specimens were collected. It is noteworthy that one of the analysed females from this locality carried the H02 haplotype, typically associated with bisexuals (see explanations below), which suggests the presence of males in this population, at least in small numbers. In two other all-female populations, No21 and Ru04, a much larger number of C. ledi specimens were analysed (42 and 50, respectively). Thus, even if males do occur in these localities, their frequency in the population should be very low. Moreover, none of the 41 females sequenced from Ru04 carried the bisexual haplotype H02, indicating that all the analysed specimens are triploids.

In C. myrtilli, triploid apomictic females produce rare non-functional males and diploid females at equal frequencies of up to 11% [6,7]. In our study of C. ledi, the frequency of males was significantly higher in most populations, where both sexes were present, suggesting possible bisexual reproduction. However, the functionality of these males must be confirmed by cytological analysis of meiosis, which has not yet been done. Cytological and haplotype analyses confirmed the mixed structure of these populations, represented by both bisexual and parthenogenetic lineages occurring syntopically and synchronously. In addition, populations with very high frequencies of males (32–46%) were found in geographically remote regions, including the Russian High North, southern Scandinavia, and Central Europe, suggesting fully bisexual reproduction, although the presence of sporadic parthenogens and rare cases of parthenogenetic reproduction in these populations cannot be completely ruled out. We analysed the ploidy levels of females in five selected populations with different frequencies of males. The results of cytological analysis agree well with the inferred sex ratios and reproductive strategies (parthenogenetic, mixed, or bisexual) for these populations (Supplementary Table S3). Specifically, in populations with the highest proportion of males (almost equal to the proportion of females), the analysed females were almost exclusively diploid, supporting the conclusion that these populations are bisexual. These findings are consistent with the general assertion that a population can be considered bisexual if at least 30% of individuals are males [47]. In populations with the proportion of males less than 30%, both diploid and triploid females were found, indicating a mixed composition of these populations, consisting of both bisexual and parthenogenetic lineages. The ratio of diploid to triploid females strongly correlates with the frequency of males: the lower the frequency of males, the higher the proportion of triploid females in the population.

One of the most intriguing results of our study is that in a vast geographical area covering southern and central Fennoscandia and southern northwestern Russia, parthenogenetic and bisexual lineages co-existing within the same populations can be distinguished by mitochondrial DNA barcodes alone. Diploid females and functional males in this region carry the main haplotype H02 or its satellite haplotypes, whereas triploid females invariably carry the main haplotype H01 or its derivatives. This pattern persists in populations with low frequencies of males and diploid females, suggesting that mitochondrial DNA barcodes provide a clear genetic distinction between parthenogenetic and bisexual individuals. It remains unclear whether functional males can non-specifically mate with both abundant triploid (parthenogenetic) and rare diploid (“bisexual”) females, or whether they are able to distinguish between these two types of females. Our study also highlighted rare cases where parthenogenetic C. ledi females produce rare functional males. For example, in the Levonsuo population (Fi39) in southern Finland, which reproduces predominantly by parthenogenesis, a male carrying the same haplotype as triploid females was found, indicating a functional reversion from triploidy.

A completely different pattern was observed in northern Fennoscandia, where either mixed or completely bisexual populations were found. In contrast to southern Fennoscandia, all males and diploid females in the northern populations shared the same haplotype as triploid females. Bisexual reproduction is considered ancestral to parthenogenesis [48]. Thus, the pattern observed in northern Scandinavia and the Russian High North appears to represent a secondary reversion from parthenogenesis to bisexual reproduction, which likely occurred very recently in the evolutionary history of C. ledi, since bisexual individuals have not yet accumulated nucleotide differences in their DNA barcodes.

According to the concept of geographic parthenogenesis [49,50,51], parthenogenetic species or populations tolerate harsh climatic conditions better, often colonising higher latitudes and altitudes than their bisexual relatives. The phylogeographic pattern revealed in our study suggests that the current distribution of parthenogenetic and bisexual lineages of C. ledi is closely linked to the processes of recent post-glacial recolonization. After the retreat of the ice sheets, the bisexual lineage reached the White Sea, central Karelia and southern Finland, while the parthenogenetic lineage spread further north, colonising areas with more severe climatic conditions. Subsequently, the parthenogenetic lineage gave rise to secondary bisexual populations, most likely when climatic conditions became more favourable for the survival and persistence of bisexual individuals. This bisexual lineage is geographically well isolated (by ca. 400 km) from the ancestral bisexual populations (Figure 4) and currently descends from triploid ancestors. This geographic isolation may promote further divergence between the two bisexual lineages, potentially leading to the formation of a new species.

4.2. Wolbachia Infection

Wolbachia is one of the most common endosymbiotic bacteria in terrestrial arthropods, known for its diverse impacts on host species. Wolbachia can affect the reproduction and physiology of the host, causing feminization, altering the sex ratios by male-killing, prompting parthenogenesis, or causing cytoplasmic incompatibility. In the latter case, infected females can successfully mate only with uninfected males or males infected with the same Wolbachia strain [52,53,54]. In addition, Wolbachia has been shown to drive diversification and speciation in its hosts [55,56]. It can also induce mitochondrial selective sweeps due to genetic “hitchhiking”, leading to mito-nuclear discordance and potential misinterpretations of mtDNA-based phylogenies [28,57,58].

To study the impact of Wolbachia on C. ledi and to assess whether the endosymbiont influences the parthenogenetic and bisexual reproductive patterns observed in this species, we performed PCR screening for three Wolbachia genes based on a large-scale and geographically extensive sampling. Unlike the closely related Cacopsylla species studied earlier [17], which showed a complex pattern of Wolbachia prevalence with varying infection levels in populations, including both infected and uninfected ones, all 1140 C. ledi specimens from 32 populations were infected with Wolbachia. Analysis of the Wolbachia wsp gene fragment revealed three closely related alleles in C. ledi, none of which was species-specific, being shared with at least one other Cacopsylla species. The most common allele, wMyr01, was detected in most C. ledi specimens, as well as in several other Cacopsylla species, including C. myrtilli, C. borealis, C. lapponica, and C. fraudatrix. The wMyr02 allele was found in C. ledi specimens from two regions: northern Murmansk and the Leningrad Oblast. It has also been detected in C. borealis (unpublished data) and C. myrtilli [17]. In the latter species, the wMyr02 was found exclusively in a geographically remote population from Magadan (the Russian Far East), which indicates the wide distribution of this allele across the Palaearctic. In C. ledi, the wMyr02 strain was present either as a single infection (in specimens with the H05 haplotype, unique to the population Ru16), or combined with the wMyr01 (in Leningrad Oblast) and with the wMyr01 and wLed alleles (in specimens with the H01 haplotype from the population Ru16), indicating a co-infection with two or even three Wolbachia alleles. It is noteworthy that in the Leningrad Oblast, the wMyr02 allele was characteristic exclusively of “bisexual” specimens (haplotypes H02 and H03) and was never detected in the parthenogenetic lineage (haplotype H01). The third allele, wLed, was detected only in a geographically remote population from Vorkuta (Ru42) and in one population from the Russian High North (Ru16). This allele was also identified in specimens of the closely related sympatric species C. borealis collected from these localities (unpublished data). In Ru42, wLed occurred as a single infection, while in Ru16, it was always found together with two other alleles, wMyr01 and wMyr02, suggesting multiple Wolbachia infection. Given that C. borealis utilises the same host plant (Ledum palustre) as C. ledi, the presence of identical Wolbachia alleles in both species suggests potential interspecific horizontal transmission through a common food substrate.

Our study revealed no differences in Wolbachia infection rates between males and females, between specimens with different ploidy levels (diploids and triploids), and between parthenogenetic (“female-only”), genuine bisexual, and mixed populations (where two reproductively isolated lineages, reproducing parthenogenetically and bisexually, co-exist in the same population). A well-known effect of Wolbachia is a decrease in mtDNA polymorphism in host species [22,59,60]. However, we did not detect such an effect. Our data suggest that haplotype diversity in some C. ledi populations varies significantly irrespective of Wolbachia infection. We also found that Wolbachia alleles detected in C. ledi are not limited to a specific COI haplotype (-es), as has been shown in other insects such as Lepidoptera [33,61].

5. Conclusions

- The plant louse C. ledi exhibits two different reproductive strategies throughout its distribution range: parthenogenetic and bisexual. Parthenogens are geographically widespread and have been found in all studied populations, with the exception of an isolated Central European population in the Southern Bohemia. Bisexuals occupy two geographically separated zones and appear to have emerged at least twice in the evolutionary history of C. ledi. Bisexuals found in central Europe and southern Fennoscandia are of ancestral origin, while those inhabiting northern Fennoscandia have emerged recently as a reversion from a parthenogenetic lineage.

- Haplotype analysis of DNA barcodes revealed a star-like structure with two dominant, geographically widespread major haplotypes and a number of satellite, mainly private haplotypes. This structure indicates a relatively rapid species expansion of C. ledi, most likely associated with post-glacial recolonization processes.

- The ancestral bisexual lineage is characterised by specific COI haplotypes that were not found in parthenogens, and it can be easily distinguished using DNA barcoding alone.

- Haplotype diversity, reproductive strategies, and shifts in modes of reproduction in C. ledi are not associated with Wolbachia infection. They are likely influenced by other factors, most probably environmental or biogeographical, which warrants further study. Nonetheless, the presence of Wolbachia infection in all analysed C. ledi specimens suggests that the endosymbiont plays an important role in the biology and evolution of the species, potentially contributing to the observed biogeographic patterns. No other Cacopsylla species previously screened for Wolbachia had such a total infection.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/insects16121268/s1, Table S1: List of collected material; Table S2: List of sampling localities and sequenced individuals (males and females) of Cacopsylla ledi sequenced from each locality. Asterisk (*) indicates an immature individual; Table S3: Sex ratio (number of males and females) and male frequency with 95% confidence intervals (in brackets) in studied populations of C. ledi; Table S4: List of specimens sequenced for Wolbachia wsp gene.

Author Contributions

Project design, N.A.S.; conceptualization, N.A.S.; project administration, N.A.S. and V.G.K.; supervision, N.A.S. and V.G.K.; methodology, N.A.S., C.N., S.N. and V.G.K.; taxon sampling, N.A.S., G.N.S., C.N., S.N., E.S.L. and V.G.K.; formal analysis, N.A.S., G.N.S., C.N., S.N. and A.E.R.; visualisation, N.A.S. and G.N.S.; data curation, N.A.S., G.N.S., C.N., S.N. and V.G.K.; funding acquisition, N.A.S., C.N., S.N. and V.G.K.; writing—original draft, N.A.S.; Writing—review and editing, G.N.S., C.N., S.N. and V.G.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was carried out with the support of the state research project No. 125012901042-9, the state assignment of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (project FZMW-2023-0006) and the Finnish Cultural Foundation (Varsinais-Suomi Regional Fund), the Betty Väänänen Foundation.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to N.S. Khabasova, M.Yu. Mandelshtam, G.G. Paskerova, P.P. Strelkov, for their help in collecting material for the present study; to Sona Mamedova (St. Petersburg State University, Russia) for assistance in DNA extraction and PCR-screening. The authors acknowledge Saint-Petersburg State University for a research project AAAA-A19-119091690086-6 (sequencing the samples). Sequencing was carried out at the Research Resource Center for Molecular and Cell Technologies (Scientific Park, St. Petersburg State University, St. Petersburg, Russia) within the framework of state assignment No. 125022803066-3.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Psyl’list—The World Psylloidea Database. 2021. Available online: https://data.nhm.ac.uk/dataset/psyl-list/resource/8746ceec-4846-4899-b607-9ba603002033 (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Drohojowska, J.; Kalandyk-Kołodziejczyk, M.; Simon, E. Thorax morphology of selected species of the genus Cacopsylla (Hemiptera, Psylloidea). ZooKeys 2013, 319, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hodkinson, I.D. Present-day distribution patterns of the Holarctic Psylloidea (Homoptera: Insecta) with particular reference to the origin of the Nearctic fauna. J. Biogeogr. 1980, 7, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, D. Australian Psylloidea: Jumping Plantlice and Lerp Insects; Australian Biological Resources Study: Canberra, Australia, 2004; 216p, ISBN 9780642568366. [Google Scholar]

- Nokkala, S.; Maryańska-Nadachowska, A.; Kuznetsova, V.G. First evidence of polyploidy in Psylloidea (Homoptera, Sternorrhyncha): A parthenogenetic population of Cacopsylla myrtilli (W. Wagner, 1947) from northeast Finland is apomictic and triploid. Genetica 2008, 133, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokkala, C.; Kuznetsova, V.G.; Nokkala, S. Meiosis in rare males in parthenogenetic Cacopsylla myrtilli (Wagner, 1947) (Hemiptera, Psyllidae) populations from northern Europe. Comp. Cytogenet. 2013, 7, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Nokkala, C.; Kuznetsova, V.G.; Nokkala, S. Rare diploid females coexist with rare males: A novel finding in triploid parthenogenetic populations in the psyllid Cacopsylla myrtilli (W.Wagner, 1947) (Hemiptera, Psylloidea) in northern Europe. Genetica 2015, 143, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokkala, S.; Kuznetsova, V.G.; Nokkala, C. Characteristics of parthenogenesis in Cacopsylla ledi (Flor, 1861) (Hemiptera, Sternorryncha, Psylloidea): Cytological and molecular approaches. Comp. Cytogenet. 2017, 11, 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nokkala, S.; Kuznetsova, V.G.; Pietarinen, P.; Nokkala, C. Evolutionary potential of parthenogenesis—Bisexual lineages within triploid apomictic thelytoky in Cacopsylla ledi (Flor, 1861) (Hemiptera, Psylloidea) in Fennoscandia. Insects 2022, 13, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normark, B.B. The evolution of alternative genetic systems in insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2003, 48, 397–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, J.-C.; Delmotte, F.; Rispe, C.; Crease, T. Phylogenetic relationships between parthenogens and their sexual relatives: The possible routes to parthenogenesis in animals. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2003, 79, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccari, M.; Gómez, A.; Hontoria, F.; Amat, F. Functional rare males in diploid parthenogenetic Artemia. J. Evol. Biol. 2013, 26, 1934–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vershinina, A.O.; Kuznetsova, V.G. Parthenogenesis in Hexapoda: Entognatha and non-holometabolous insects. J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 2016, 54, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokkala, C.; Kuznetsova, V.G.; Rinne, V.; Nokkala, S. Description of two new species of the genus Cacopsylla Ossiannilsson, 1970 (Hemiptera, Psylloidea) from northern Fennoscandia recognized by morphology, cytogenetic characters and COI barcode sequence. Comp. Cytogenet. 2019, 13, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labina, E.S.; Nokkala, S.; Maryańska-Nadachowska, A.; Kuznetsova, V.G. The distribution and population sex ratio of Cacopsylla myrtilli (W. Wagner, 1947) (Hemiptera: Psylloidea). Folia Biol. 2009, 57, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokkala, C.; Kuznetsova, V.G.; Shapoval, N.A.; Nokkala, S. Phylogeography and Wolbachia infections reveal postglacial recolonization routes of the parthenogenetic plant louse Cacopsylla myrtilli (W. Wagner 1947), (Hemiptera, Psylloidea). J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 2022, 2022, 5458633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapoval, N.A.; Nokkala, S.; Nokkala, C.; Kuftina, G.N.; Kuznetsova, V.G. The incidence of Wolbachia bacterial endosymbiont in bisexual and parthenogenetic populations of the psyllid genus Cacopsylla (Hemiptera, Psylloidea). Insects 2021, 12, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ossiannilsson, F. The Psylloidea (Homoptera) of Fennoscandia and Denmark; Fauna Entomologica Scandinavica; Brill Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1992; Volume 26, pp. 1–347. [Google Scholar]

- Zeh, D.; Zeh, J.; Bonilla, M. Wolbachia, sex ratio bias and apparent male killing in the harlequin beetle riding pseudoscorpion. Heredity 2005, 95, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huigens, M.E.; de Almeida, R.P.; Boons, P.A.; Luck, R.F.; Stouthamer, R. Natural interspecific and intraspecific horizontal transfer of parthenogenesis-inducing Wolbachia in Trichogramma wasps. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 271, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Muhammad, A.; Bala, N.S.; Wang, G.; Chen, Z.; Peng, Z.; Hou, Y. Genomic evaluations of Wolbachia and mtDNA in the population of coconut hispine beetle, Brontispa longissima (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2018, 127, 1000–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhu, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Ge, C.; Wang, Y.; Endersby, N.M.; Hoffmann, A.A.; Yu, W. Influence of Wolbachia infection on mitochondrial DNA variation in the genus Polytremis (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2018, 129, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitworth, T.L.; Dawson, R.D.; Magalon, H.; Baudry, E. DNA barcoding cannot reliably identify species of the blowfly genus Protocalliphora (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2007, 274, 1731–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlat, S.; Duplouy, A.; Hornett, E.A.; Dyson, E.A.; Davies, N.; Roderick, G.K.; Wedell, N.; Hurst, G.D.D. The joint evolutionary histories of Wolbachia and mitochondria in Hypolimnas bolina. BMC Evol. Biol. 2009, 9, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, S.; Nomura, M.; Kato, Y.; Fukatsu, T. Genetic structure of sibling butterfly species affected by Wolbachia infection sweep: Evolutionary and biogeographical implications. Mol. Ecol. 2006, 15, 1095–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, J.W.O. Comparative genomics of mitochondrial DNA in Drosophila simulans. J. Mol. Evol. 2000, 51, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballard, J.W.O. When one is not enough: Introgression of mitochondrial DNA in Drosophila. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000, 17, 1126–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiggins, F.M. Male-killing Wolbachia and mitochondrial DNA: Selective sweeps, hybrid introgression and parasite population dynamics. Genetics 2003, 164, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousset, F.; Solignac, M. Evolution of single and double Wolbachia symbioses during speciation in the Drosophila simulans complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 6389–6393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.G.; Thompson, W.F. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980, 8, 4321–4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukhtanov, V.A.; Shapoval, N.A. Detection of cryptic species in sympatry using population analysis of unlinked genetic markers: A study of the Agrodiaetus kendevani species complex (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae). Dokl. Biol. Sci. 2008, 423, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukhtanov, V.A.; Shapoval, N.A.; Dantchenko, A.V. Agrodiaetus shahkuhensis sp. n. (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae), a cryptic species from Iran discovered by using molecular and chromosomal markers. Comp. Cytogenet. 2008, 2, 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Shapoval, N.A.; Kir’yanov, A.V.; Krupitsky, A.V.; Yakovlev, R.V.; Romanovich, A.E.; Zhang, J.; Cong, Q.; Grishin, N.V.; Kovalenko, M.G.; Shapoval, G.N. Phylogeography of two enigmatic sulphur butterflies, Colias mongola Alphéraky, 1897 and Colias tamerlana Staudinger, 1897 (Lepidoptera, Pieridae), with relations to Wolbachia Infection. Insects 2023, 14, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, V.G.; Labina, E.S.; Shapoval, N.A.; Maryańska-Nadachowska, A.; Lukhtanov, V.A. Cacopsylla fraudatrix sp.n. (Hemiptera: Psylloidea) recognised from testis structure and mitochondrial gene COI. Zootaxa 2012, 3547, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, M.; Posada, D.; Crandall, K.A. TCS: A computer program to estimate gene genealogies. Mol. Ecol. 2000, 9, 1657–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, J.W.; Bryant, D. PopART: Full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 3299–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werren, J.H.; Windsor, D.M. Wolbachia infection frequency in insects: Evidence of a global equilibrium? Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2000, 267, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Rousset, F.; O’Neil, S. Phylogeny and PCR-based classification of Wolbachia strains using wsp gene sequences. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1998, 265, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeyaprakash, A.; Hoy, M.A. Long PCR improves Wolbachia DNA amplification: Wsp sequences found in 76% of sixty-three arthropod species. Insect Mol. Biol. 2000, 9, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukhtanov, V.A.; Shapoval, N.A.; Anokhin, B.A.; Saifitdinova, A.F.; Kuznetsova, V.G. Homoploid hybrid speciation and genome evolution via chromosome sorting. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 282, 20150157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapoval, N.A.; Lukhtanov, V.A. Intragenomic variations of multicopy ITS2 marker in Agrodiaetus blue butterflies (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae). Comp. Cytogenet. 2015, 9, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çoraman, E.; Dundarova, H.; Dietz, C.; Mayer, F. Patterns of mtDNA introgression suggest population replacement in Palaearctic whiskered bat species. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2000, 7, 191805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincă, V.; Dapporto, L.; Somervuo, P.; Vodă, R.; Cuvelier, S.; Gascoigne-Pees, M.; Huemer, P.; Mutanen, M.; Hebert, P.D.N.; Vila, R. High resolution DNA barcode library for European butterflies reveals continental patterns of mitochondrial genetic diversity. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Joshi, P.C.; Joshi, B.D. Molecular data suggest population expansion and high level of gene flow in the Plain Tiger (Danaus chrysippus; Nymphalidae: Danainae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2018, 3, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norton, R.A.; Kethley, J.B.; Johnston, D.E.; O’Connor, B.M. Phylogenetic perspectives on genetic systems and reproductive modes of mites. In Evolution and Diversity of Sex Ratio in Haplodiploid Insects and Mites; Wrench, D., Ebbert, M., Eds.; Chapman & Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 8–99. ISBN 9780412022210. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.J.D. Animal Cytology and Evolution, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1973; 468p, ISBN 9780521292276. [Google Scholar]

- Hörandl, E. The complex causality of geographical parthenogenesis. New Phytol. 2006, 171, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, M. Hybridization, glaciation and geographical parthenogenesis. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundmark, M. Polyploidization, hybridization and geographical parthenogenesis. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2006, 21, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukui, T.; Kawamoto, M.; Shoji, K.; Kiuchi, T.; Sugano, S.; Shimada, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Katsuma, S. The endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia selectively kills male hosts by targeting the masculinizing gene. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiggins, F.M.; Hurst, G.D.D.; Dolman, C.E.; Majerus, M.E.N. High-prevalence male-killing Wolbachia in the butterfly Acraea encedana. J. Evol. Biol. 2000, 13, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stouthamer, R.; Breeuwer, J.A.J.; Hurst, G.D.D. Wolbachia pipientis: Microbial manipulator of arthropod reproduction. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1999, 53, 71–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly-Bechet, M.; Martins-Simões, P.; Szöllősi, G.J.; Mialdea, G.; Sagot, M.-F.; Charlat, S. How long does Wolbachia remain on board? Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 1183–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werren, J.H. Wolbachia and speciation. In Endless Forms: Species and Speciation; Howard, D., Berlocher, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 245–260. ISBN 9780195109016. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, S.; Michalski, S.G.; Settele, J.; Wiemers, M.; Fric, Z.F.; Sielezniew, M.; Šašić, M.; Rozier, Y.; Durka, W. Wolbachia infections mimic cryptic speciation in two parasitic butterfly species, Phengaris teleius and P. nausithous (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telschow, A.; Gadau, J.; Werren, J.H.; Kobayashi, Y. Genetic incompatibilities between mitochondria and nuclear genes: Effect on gene flow and speciation. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Gao, J.; Wang, G.; Zhao, M.; Xing, D.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, H. Effects of Wolbachia on mitochondrial DNA variation in Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae). Acta Trop. 2025, 263, 107561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoemaker, D.D.; Dyer, K.A.; Ahrens, M.; McAbee, K.; Jaenike, J. Decreased diversity but increased substitution rate in host mtDNA as a consequence of Wolbachia endosymbiont infection. Genetics 2004, 168, 2049–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sucháčková Bartoňová, A.; Konvička, M.; Marešová, J.; Wiemers, M.; Ignatev, N.; Wahlberg, N.; Schmitt, T.; Fric, Z.F. Wolbachia affects mitochondrial population structure in two systems of closely related Palaearctic blue butterflies. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).