Pheromone Race Composition of Ostrinia nubilalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) and Larval Co-Occurrence with Sesamia nonagrioides (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Maize in Central-Eastern Italy

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

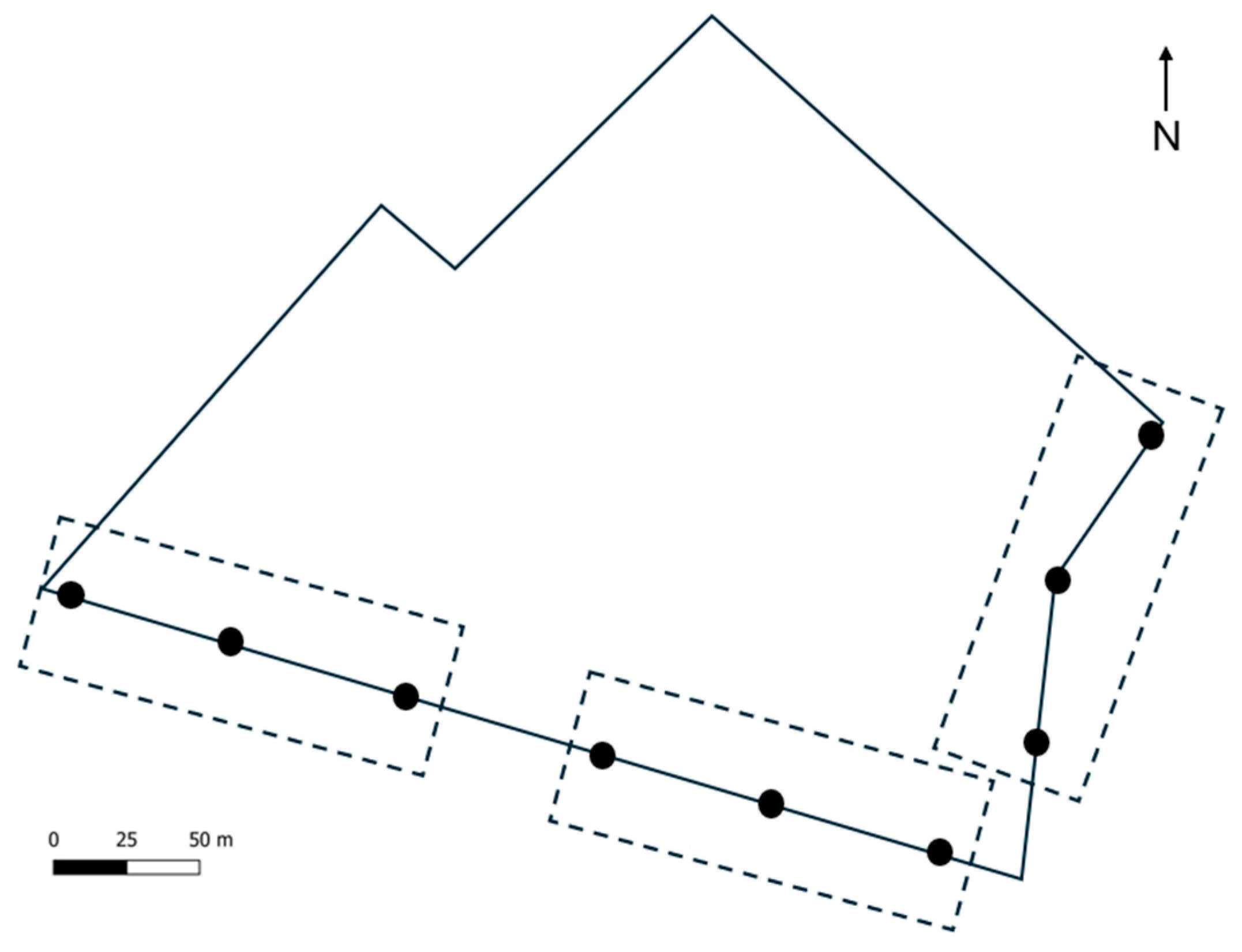

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Adult Captures

2.3. Larval Sampling

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Adult Captures

3.2. Corn Borer Larval Incidence and Abundance

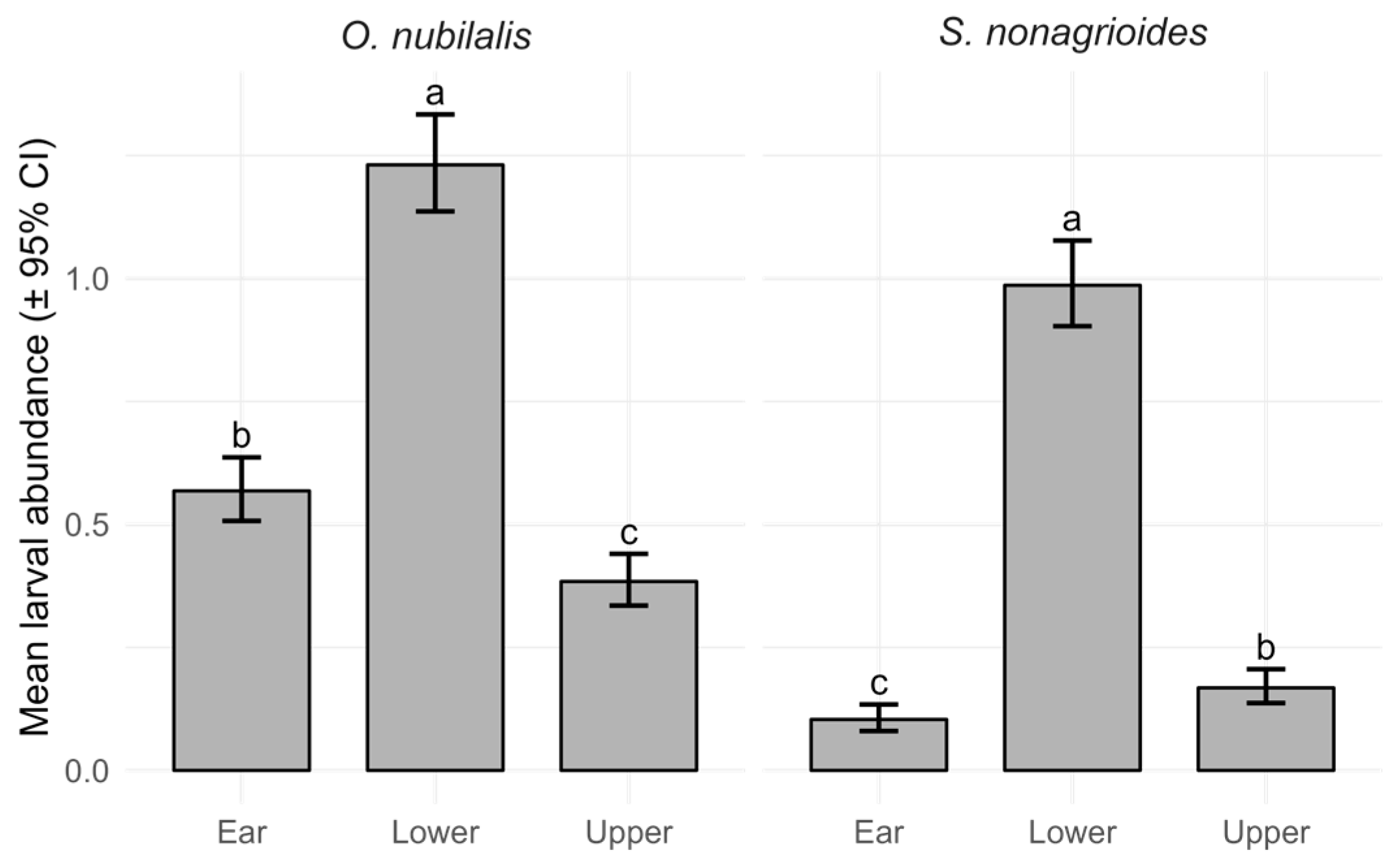

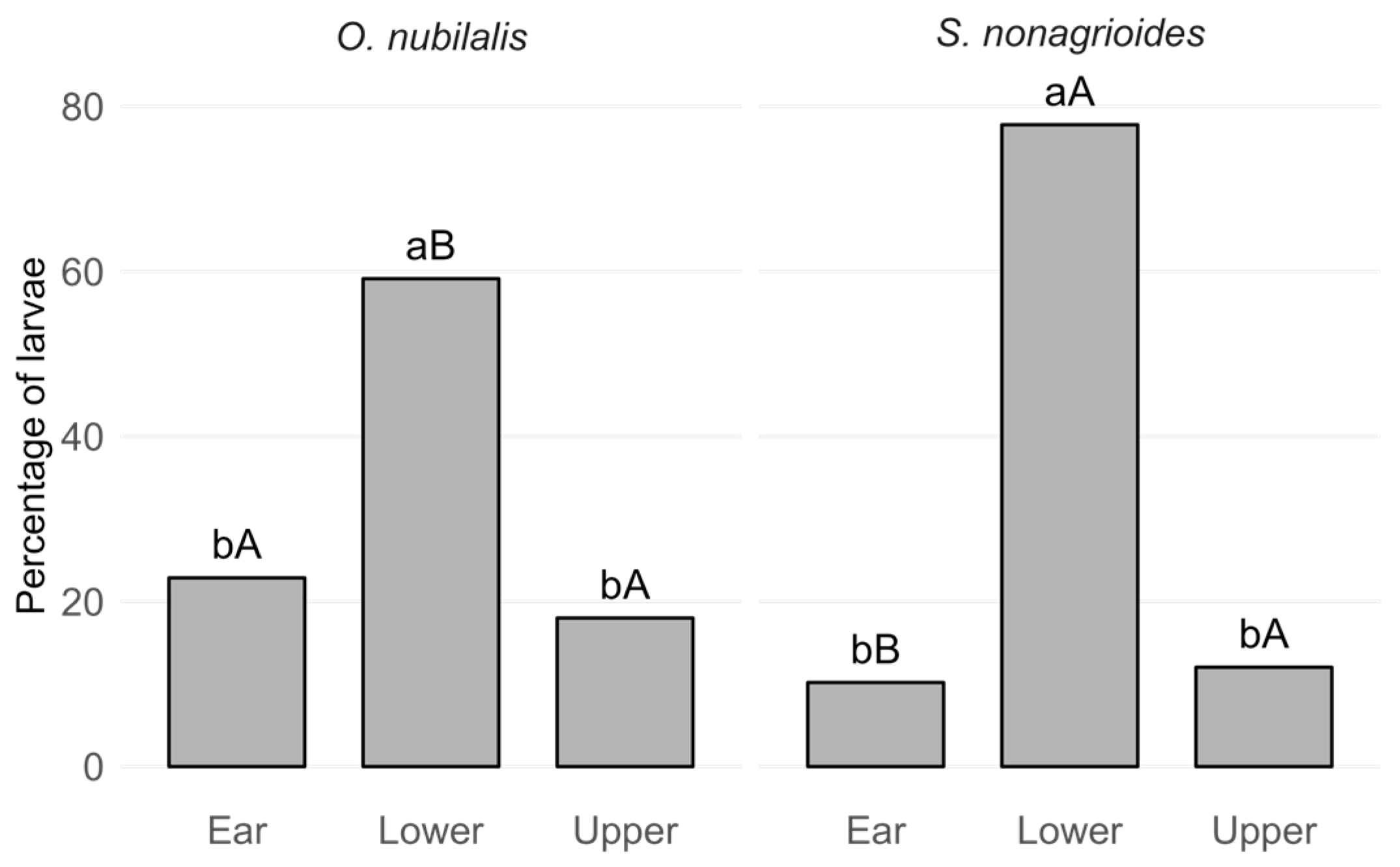

3.3. Corn Borer Larvae Distribution

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ECB | European corn borer |

| MCB | Mediterranean corn borer |

| IPM | Integrated pest management |

| LS | Lower section |

| US | Upper section |

| E | Ears |

| GLMM | Generalized linear mixed models |

References

- Ameline, A.; Frérot, B. Pheromone Blends and Trap Designs Can Affect Catches of Sesamia Nonagrioides Lef. (Lep., Noctuidae) Males in Maize Fields. J. Appl. Entomol. 2001, 125, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandino, M.; Scarpino, V.; Vanara, F.; Sulyok, M.; Krska, R.; Reyneri, A. Role of the European Corn Borer (Ostrinia nubilalis) on Contamination of Maize with 13 Fusarium Mycotoxins. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2015, 32, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero-Rivera, A.; Malvar, R.A.; Butrón, A.; Revilla, P. Population Dynamics and Life-Cycle of Corn Borers in South Atlantic European Coast. Maydica 1998, 43, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kaçar, G.; Butrón, A.; Kontogiannatos, D.; Han, P.; Peñaflor, M.F.G.V.; Farinós, G.P.; Huang, F.; Hutchison, W.D.; De Souza, B.H.S.; Malvar, R.A.; et al. Recent Trends in Management Strategies for Two Major Maize Borers: Ostrinia nubilalis and Sesamia nonagrioides. J. Pest Sci. 2023, 96, 879–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreadis, S.S.; Vryzas, Z.; Papadopoulou-Mourkidou, E.; Savopoulou-Soultani, M. Age-dependent Changes in Tolerance to Cold and Accumulation of Cryoprotectants in Overwintering and Non-overwintering Larvae of European Corn Borer Ostrinia nubilalis. Physiol. Entomol. 2008, 33, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alma, A.; Lessio, F.; Reyneri, A.; Blandino, M. Relationships between Ostrinia nubilalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) Feeding Activity, Crop Technique and Mycotoxin Contamination of Corn Kernel in Northwestern Italy. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2005, 51, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Martín, M.; Haidukowski, M.; Farinós, G.P.; Patiño, B. Role of Sesamia nonagrioides and Ostrinia nubilalis as Vectors of Fusarium Spp. and Contribution of Corn Borer-Resistant Bt Maize to Mycotoxin Reduction. Toxins 2021, 13, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capinera, J.L. European Corn Borer, Ostrinia nubilalis (Hubner) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). EDIS 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassance, J.-M. Journey in the Ostrinia World: From Pest to Model in Chemical Ecology. J. Chem. Ecol. 2010, 36, 1155–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiorano, A.; Donatelli, M. Validation of an Insect Pest Phenological Model for the European Corn Borer (Ostrinia nubilalis Hbn) in the Po Valley in Italy. J. Agrometeorol. 2014, 18, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Riolo, P.; Nardi, S.; Carboni, M.; Riga, F.; Piunti, A.; Isidoro, N. Insetti Associati Ad Arecaceae Nelle Marche. In Sessione V–Entomologia Agraria, Proceedings of the XXI Congresso Nazionale Italiano di Entomologia, Campobasso, Italy, 11–16 June 2007; Accademia Nazionale Italiana di Entomologia: Florence, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Peña, A.; Arn, H.; Buser, H.-R.; Rauscher, S.; Bigler, F.; Brunetti, R.; Maini, S.; Tóth, M. Sex Pheromone of European Corn Borer: Ostrinia nubilalis: Polymorphism in Various Laboratory and Field Strains. J. Chem. Ecol. 1988, 14, 1359–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerini, G.; Groppali, R.; Rama, F.; Maini, S. Semiochemicals of Ostrinia nubilalis: Diel Response to Sex Pheromone and Phenylacetaldehyde in Open Field. Bull. Insectol. 2015, 68, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Klun, J.A.; Maini, S. Genetic Basis of an Insect Chemical Communication System: The European Corn Borer. Environ. Entomol. 1979, 8, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglade, P.; Stockel, J.; I.W.G.O. Cooperators. Intraspecific Sex-Pheromone Variability in the European Corn Borer, Ostrinia nubilalis Hbn. (Lepidoptera, Pyralidae). Agronomie 1984, 4, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderbrant, O.; Marques, J.F.; Aldén, L.; Svensson, G.P. Occurrence of Z- and E-strain Ostrinia nubilalis in Sweden Shortly after First Detection of the Z-strain. J. Appl. Entomol. 2024, 148, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochansky, J.; Cardé, R.T.; Liebherr, J.; Roelofs, W.L. Sex Pheromone of the European Corn Borer, Ostrinia nubilalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae), in New York. J. Chem. Ecol. 1975, 1, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malausa, T.; Bethenod, M.T.; Bontemps, A.; Bourguet, D.; Cornuet, J.-M.; Ponsard, S. Assortative Mating in Sympatric Host Races of the European Corn Borer. Science 2005, 308, 258–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linn, C.E.; Young, M.S.; Gendle, M.; Glover, T.; Roelofs, W. Sex Pheromone Blend Discrimination in Two Races and Hybrids of the European Corn Borer Moth, Ostrinia nubilalis. Physiol. Entomol. 1997, 22, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magagnoli, S.; Lanzoni, A.; Masetti, A.; Depalo, L.; Albertini, M.; Ferrari, R.; Spadola, G.; Degola, F.; Restivo, F.M.; Burgio, G. Sustainability of Strategies for Ostrinia nubilalis Management in Northern Italy: Potential Impact on Beneficial Arthropods and Aflatoxin Contamination in Years with Different Meteorological Conditions. Crop Prot. 2021, 142, 105529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bažok, R.; Igrc Barèiæ, J.; Kos, T.; Èuljak, T.G.; Šiloviæ, M.; Jelovèan, S.; Kozina, A. Monitoring and Efficacy of Selected Insecticides for European Corn Borer (Ostrinia nubilalis Hubn., Lepidoptera: Crambidae) Control. J. Pest Sci. 2009, 82, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaafsma, A.W.; Meloche, F.; Pitblado, R.E. Effect of Mowing Corn Stalks and Tillage on Overwintering Mortality of European Corn Borer (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) in Field Corn. J. Econ. Entomol. 1996, 89, 1587–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sándor, K.; Holló, G. Evaluation of influencing factors on the location and displacement of Ostrinia nubilalis larvae in maize stalks measured by computed tomography. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showers, W. European Corn Borer: Development and Management; Iowa State University: Ames, Iowa, 1989; Publication, No. 327. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantopoulou, M.A.; Krokos, F.D.; Mazomenos, B.E. Chemical Composition of Corn Leaf Essential Oils and Their Role in the Oviposition Behavior of Sesamia nonagrioides Females. J. Chem. Ecol. 2004, 30, 2243–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eizaguirre, M.; Fantinou, A.A. Abundance of Sesamia nonagrioides (Lef.) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on the Edges of the Mediterranean Basin. Psyche J. Entomol. 2012, 2012, 854045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillyboeuf, N.; Anglade, P.; Lavenseau, L.; Peypelut, L. Cold Hardiness and Overwintering Strategy of the Pink Maize Stalk Borer, Sesamia nonagrioides Lef (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae). Oecologia 1994, 99, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreadis, S.S.; Vryzas, Z.; Papadopoulou-Mourkidou, E.; Savopoulou-Soultani, M. Cold Tolerance of Field-Collected and Laboratory Reared Larvae of Sesamia nonagrioides (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). CryoLetters 2011, 32, 297–307. [Google Scholar]

- Ciampolini, M.; Zancheri, S. Sesamia nonagrioides (Lef.) e Peridroma saucia Hb. (Lep. Noctuidae) dannose a colture floricole. Boll. Zool. Agrar. Bachic. 1975, 13, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Porcelli, F.; Parenzan, P. Danni Da Opogona sacchari e Sesamia nonagrioides a Strelitzia in Italia Meridionale. Inf. Fitopatol. 1993, 12, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Nucifora, A. Appunti Sulla Biologia Di Sesamia nonagrioides (Lef.) in Sicilia. Tec. Agric. 1966, 18, 395–419. [Google Scholar]

- Maini, S.; Conti, B.; Rizzoli, L.; Mencarelli, M. La Nottua Del Mais Ha Sconfinato in Emilia. Agricoltura 2016, 63–64. [Google Scholar]

- Pollini, A. Parte Speciale-Ordine: Lepidoptera. In Manuale di Entomologia Applicata; Edagricole: Bologna, Italy, 2002; pp. 658–660. [Google Scholar]

- Prota, R. Osservazioni Sull’etologia Di Sesamia nonagrioides (Lefebvre) in Sardegna. Studi Sass. Sez 1965, 3, 336–360. [Google Scholar]

- Avantaggiato, G.; Quaranta, F.; Desiderio, E.; Visconti, A. Fumonisin Contamination of Maize Hybrids Visibly Damaged by Sesamia. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2003, 83, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandino, M.; Carnaroglio, F.; Reyneri, A.; Vanara, F.; Pascale, M.; Haidukowski, M.; Saporiti, M. Impiego Di Insetticidi Piretroidi Contro La Piralide Del Mais. Inf. Agriario 2006, 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Tonğa, A.; Bayram, A. Natural Parasitism of Maize Stemborers, Sesamia Spp. (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Eggs by Trichogramma Evanescens (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae) in Southeastern Turkey. Int. J. Agric. Environ. Food Sci. 2021, 5, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, B.P.; Tóth, Z.; Fejes-Tóth, A.; Dekker, T.; Kárpáti, Z. Electrophysiologically-Active Maize Volatiles Attract Gravid Female European Corn Borer, Ostrinia nubilalis. J. Chem. Ecol. 2015, 41, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasco, P.; Revilla, P.; Monetti, L.; Butrón Gómez, A.M.; Ordás Pérez, A.; Malvar Pintos, R.A. Corn Borers (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae; Crambidae) in Northwestern Spain: Population Dynamics and Distribution. Maydica 2007, 52, 195–203. [Google Scholar]

- Riolo, P. Sesamia e Piralide: Attacchi Su Mais Da Granella Nel Marchigiano. Inf. Agrar. 2001, 57, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, R.P.; Charlton, R.E.; Schal, C.; Cardé, R.T. High-Efficiency Pheromone Trap for the European Corn Borer (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 1986, 79, 1139–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using Lme4. J. Stat. Soft. 2015, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, F. DHARMa: Residual Diagnostics for Hierarchical (Multi-Level/Mixed) Regression Models, Version 0.4.7. CRAN: Contributed Packages. The R Foundation: Vienna, Austria, 2016.

- Lenth, R. Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, Aka Least-Squares Means, R Package Version 1.11.2; The R Foundation: Vienna, Austria, 2023.

- Rozsypal, J. Estimating the Potential of Insects from Warmer Regions to Overwinter in Colder Regions under a Warming Winter Scenario Using Simulation Experiments: A Case Study in Sesamia nonagrioides. Insects 2023, 14, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiorano, A.; Cerrani, I.; Fumagalli, D.; Donatelli, M. New Biological Model to Manage the Impact of Climate Warming on Maize Corn Borers. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 34, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcagno, V.; Bonhomme, V.; Thomas, Y.; Singer, M.C.; Bourguet, D. Divergence in Behaviour between the European Corn Borer, Ostrinia nubilalis, and Its Sibling Species Ostrinia scapulalis: Adaptation to Human Harvesting? Proc. R. Soc. B. 2010, 277, 2703–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, J.; Xie, R.; Zhang, W.; Wang, K.; Hou, P.; Ming, B.; Gou, L.; Li, S. Research Progress on Reduced Lodging of High-Yield and -Density Maize. J. Integr. Agric. 2017, 16, 2717–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Gu, S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, P.; Huang, S. The Relationships between Maize (Zea mays L.) Lodging Resistance and Yield Formation Depend on Dry Matter Allocation to Ear and Stem. Crop J. 2023, 11, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpino, V.; Reyneri, A.; Vanara, F.; Scopel, C.; Causin, R.; Blandino, M. Relationship between European Corn Borer Injury, Fusarium Proliferatum and F. Subglutinans Infection and Moniliformin Contamination in Maize. Field Crops Res. 2015, 183, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Variable | Single-Species (%) | Co-Occurrence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| O. nubilalis | Larvae in LS | 59.1 | 55.0 |

| Larvae in US | 18.0 | 17.4 | |

| Larvae in E | 22.9 | 27.6 | |

| S. nonagrioides | Larvae in LS | 77.8 | 78.5 |

| Larvae in US | 12.0 | 13.6 | |

| Larvae in E | 10.2 | 7.9 |

| Timing | Type of Activity | Recommendations | Aims |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early spring/Pre-sowing—Growing season | Monitoring | Annual adult monitoring of corn borer species. For O. nubilalis, use pheromone traps baited with each E, Z, and E/Z pheromone lures. | Early detection and monitoring of adults to optimize timing of interventions. |

| Growing season | Field inspections | Sample and dissect symptomatic plants at multiple locations in the field to identify larvae. | Assess the species composition present in the field. |

| Growing season | Control measures | Chemical, microbiological, or biological treatments applied based on adult monitoring data and egg mass scouting (if possible). | Improve control efficacy by targeting susceptible stages (e.g., eggs and larvae before entering the stalk). |

| Growing season | Biological control | Select biological control agents considering the corn borer species present (e.g., in the case of egg parasitoids) and promote generalist predators. | Enhance management through complementary strategies, reducing reliance on chemical products. |

| Post-harvest | Agronomic control | Shred and incorporate crop residues between October and March, preferably in autumn or winter. | Increase mortality of overwintering larvae of corn borers via mechanical disruption combined with low-temperature exposure. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Battistelli, M.C.; Palpacelli, D.; Sperandio, G.; Pacella, M.; Ramilli, F.; Ruschioni, S.; Abulebda, A.M.A.; Riolo, P. Pheromone Race Composition of Ostrinia nubilalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) and Larval Co-Occurrence with Sesamia nonagrioides (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Maize in Central-Eastern Italy. Insects 2025, 16, 1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121267

Battistelli MC, Palpacelli D, Sperandio G, Pacella M, Ramilli F, Ruschioni S, Abulebda AMA, Riolo P. Pheromone Race Composition of Ostrinia nubilalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) and Larval Co-Occurrence with Sesamia nonagrioides (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Maize in Central-Eastern Italy. Insects. 2025; 16(12):1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121267

Chicago/Turabian StyleBattistelli, Maria Chiara, Diego Palpacelli, Giorgio Sperandio, Matteo Pacella, Fabio Ramilli, Sara Ruschioni, Abdalhadi M. A. Abulebda, and Paola Riolo. 2025. "Pheromone Race Composition of Ostrinia nubilalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) and Larval Co-Occurrence with Sesamia nonagrioides (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Maize in Central-Eastern Italy" Insects 16, no. 12: 1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121267

APA StyleBattistelli, M. C., Palpacelli, D., Sperandio, G., Pacella, M., Ramilli, F., Ruschioni, S., Abulebda, A. M. A., & Riolo, P. (2025). Pheromone Race Composition of Ostrinia nubilalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) and Larval Co-Occurrence with Sesamia nonagrioides (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Maize in Central-Eastern Italy. Insects, 16(12), 1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121267