Simple Summary

Immature development, larval food consumption, and adult fecundity of Chrysoperla comanche (Banks), as a predator of the leafhopper Erasmoneura variabilis (Beamer), were determined. Development times for egg, larval stages and pupa were relatively similar to those of closely related Chrysoperla species. The larval stages consumed ~250 late instar leafhoppers during a 9.6-day development period, which is comparable to feeding studies for C. carnea and C. rufilabris feeding on aphids, although prey presentation and stage (size) greatly influence consumption rates. On average, C. comanche laid >1000 eggs during a 53.6-day adult lifetime. This study indicated that C. comanche is a viable predator of vineyard leafhoppers and may be more suitable for augmentative release in some regions than the commercially available C. carnea and C. rufilabris. Results are discussed with respect to their mass production by commercial insectaries producing beneficial organisms.

Abstract

The immature development, larval food consumption, and adult fecundity of Chrysoperla comanche (Banks), as a predator of the leafhopper Erasmoneura variabilis (Beamer), were determined. The threshold temperatures of egg, first, second, and third instars, and pupal stages were 10.6, 12.9, 11.5, 10.3, and 11.0 °C, respectively, and their corresponding accumulated degree days (DDs) were 73.5, 38.5, 37.4, 44.3 and 140.4 DD. When placed in an outdoor cage, field-collected adults continued to deposit eggs during the winter months. The weight of 3 d-old cocoons was negatively related to temperature, indicating that cocoon weights decrease as temperatures near the lethal thresholds. Larvae consumed ~250 late instar E. variabilis. At 26.7 °C. Adults had an average pre-ovipositional period of 5.8 days and produced an average of 1108 eggs over their entire life of 53.6 days, with 77.3% (857 eggs) of eggs produced in the first 30 days of reproduction. The results are discussed with respect to the application and commercial production of C. comanche in biological control programs, as well as the feasibility of insectaries to produce specialty natural enemies.

1. Introduction

Green lacewings, specifically Chrysoperla and Chrysopa spp., are important insect predators and biological control agents in horticultural and agricultural ecosystems reviewed in [1,2,3]. Worldwide, Chrysoperla species rank as some of the most commonly manipulated and commercially available natural enemies [1,4,5]. However, for many years only two Chrysoperla species, C. carnea (Stephens, 1836) and C. rufilabris (Burmeister, 1839), have dominated commercial insectary programs and field studies in North America and Europe, e.g., [6,7,8,9]. Moreover, the effectiveness of C. carnea and C. rufilabris augmentative release has varied greatly; for example, studies in North America report from 0 to 100% reduction in targeted pest densities or crop damage [10]. There are numerous factors that can influence lacewing release effectiveness, such as release rate, timing and methodology, which can be controlled by the applicator. Nevertheless, the success or failure of many release programs is contingent upon the biological constraints of the lacewing species released and ecological interactions among lacewings, their prey, and the release environment [1,11,12,13]. Such interactions may be species-dependent, and there are many reasons to assume that C. carnea and C. rufilabris may not be the most appropriate lacewing species for targeted pests or ecological conditions.

A better understanding of the differences among Chrysoperla species will improve biological control programs and highlight the many Chrysoperla species, other than C. carnea and C. rufilabris, that have potential [14,15,16]. For example, C. carnea and C. rufilabris are similar in most life history traits under humid conditions (>75% RH) but under low to moderate humidity (35–55% RH) C. carnea may be more appropriate as C. rufilabris has a prolonged pre-ovipositional period, reduced fecundity, increased preimaginal mortality, and a slower developmental rate in hotter and drier conditions [17]. Plant architecture, such as leaf trichomes on cotton or leaf wax levels on cabbage, can also influence Chrysoperla spp. performance [10]. Similar to abiotic constraints, there are examples of prey species or prey stage affecting lacewing development and/or survival. Chrysoperla carnea was found to be an ineffective predator of silverleaf whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius, 1889), and the greenhouse whitefly, Trialeurodes vaporariorum (Westwood, 1856), in part, because the predator’s nutritional demands were only marginally met by feeding on whiteflies [18,19].

Here, we report on key biological parameters of Chrysoperla comanche (Banks, 1938) as a potential predator for use in biological control programs. We became aware of C. comanche’s prevalence in agricultural systems while studying commercial augmentation of C. carnea in California vineyards to suppress two leafhopper pests, Erasmoneura variabilis (Beamer, 1929), formerly Erythroneura [20], and E. elegantula Osborn, 1928 [21,22]. In post-release surveys, five green lacewing species were found: C. carnea, C. comanche, Chrysopa coloradensis Banks, 1895, Chrysopa nigricornis Burmeister, 1839, and Chrysopa oculata Say, 1839. The Chrysopa spp. were most commonly found on the ground covers but rarely on the vines, C. carnea was found on both the vines and the ground covers, and C. comanche was the most commonly found species on the vines. These results suggest that C. comanche may prove to be a better biological control agent in California San Joaquin Valley vineyard ecosystems. Nevertheless, C. comanche and other green lacewing species have received less attention as a manipulated generalist predator, and, for this reason, there are fewer studies on its biology and ecology. The study objectives were to determine C. comanche egg, larval and pupal development times; larval food consumption; and adult fecundity. The data provide some of the basic information needed to evaluate C. comanche as a potential biological control agent in comparison with C. carnea and C. rufilabris.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect Material

A laboratory colony of C. comanche was established with field-collected adults from vineyards in Fresno County, CA, USA. Lacewings were identified using a key developed by Dr. Hagen, University of California, Berkeley. Adults were fed an artificial diet made of whey yeast, an enzymatic protein hydrolysate of Brewer’s yeast, honey, and distilled water (6:1:10:5), using the procedures described by Johnson and Hagen [23]. Lacewing larvae were fed eggs of the Mediterranean flour moth, Ephestia kuehniella (Zeller, 1879), that were produced on a wheat bran mixture in 3.8 L glass jars topped with a cotton cloth as an oviposition substrate. The collected eggs were either used to maintain the moth colony or frozen and used as lacewing food. Lacewings used in the experiments were within F2–6 generations of field-collected material. Cultures were held at 25 ± 1 °C, 60 ± 10% RH and 16:8 photoperiod. Leafhoppers (E. variabilis) used in the prey-consumption study were field-collected on vines at the Kearney Agricultural Research and Extension Center (KREC) and used within 24 h of collection.

2.2. Temperature Dependent Development

The effect of constant rearing temperatures on C. comanche development time was tested at 12.7, 15.6, 21.1, 26.7, 29.4, 32.2, 33.9, 35 and 36.7 °C. To collect fresh eggs, adult female C. comanche were isolated in three 3.8 L cylindrical, waxed cardboard cartons, with ~20 adults per carton. The cartons contained strips of wax paper, which were provided as an oviposition substrate. After 4 h, eggs were harvested, isolated singly in 55 mL glass vials, and randomly assigned to a temperature treatment. Before the neonate larvae hatched, the vials were stocked with fresh E. kuehniella eggs to provide an immediately available food source. Thereafter, the vials were resupplied with E. kuehniella eggs every 2–3 days, providing an overabundance of food. Lacewing development was checked daily, recording developmental stages as: egg, first, second or third instar, pupa, or adult. There were 20–42 C. comanche tested at each temperature. After pupation, 3-day-old cocoons were weighed to estimate the influence of temperature on lacewing growth. Temperatures (T) were maintained at T ± 1 °C; 60 ± 10% RH, with a 16:8 (L:D) photoperiod; due to the availability of temperature cabinets, treatments at 15.6, 21.1, 26.7, and 32.2 °C were first tested, and then treatments 12.7, 29.4, 33.9, 35 and 36.7 °C were tested.

2.3. Adult Fecundity, Longevity and Overwintering

Chrysoperla comanche adult fecundity was tested using adults reared from field-collected eggs in KREC vineyards. After hatching, neonate larvae were provided with an excess of E. kuehniella eggs and larvae throughout lacewings’ larval stages. Upon adult emergence, lacewings were sexed, and male and female pairs were confined individually in 70 mL containers, ventilated by a 3 cm organdy-covered hole. A strip of wax paper placed under the lid served as an oviposition substrate. The adults were provided with an ad lib supply of artificial diet, as described above, and water was provided using a water-saturated cotton ball. Male lacewings were removed from the containers 7 days after egg deposition was first observed, and females were transferred to new vials every 2 days throughout their lives. The numbers of eggs deposited were recorded. There were 20 adults tested. The trial was conducted at 26.7 ± 1 °C, 60 ± 10% RH, and a photoperiod of 16L:8D.

Chrysoperla comanche overwintering viability at ambient temperatures in the San Joaquin Valley was assessed by holding field-collected adults in plastic containers (3.3 cm × 9.5 cm × 9.5 cm) in an outdoor sleeve cage from 26 October to 7 January. The adults were maintained on the same artificial diet, described above, and were transferred to new containers twice a week (Monday and Friday). Chrysoperla comanche incubation period and egg production were recorded haphazardly throughout the trial period.

2.4. Prey Consumption

The potential number of E. variabilis consumed by C. comanche during the larval period was determined. Lacewing eggs were confined singly in 35 mL glass vials with an organdy cover for ventilation. Upon hatching, larvae were supplied with freshly collected 4th or 5th instar leafhoppers every 2 days during the lacewings’ 1st and 2nd instar stages (25–50 leafhoppers each period) and daily during the 3rd instar (50–75 leafhoppers daily). The leafhoppers were presented on a grape leaf bouquet by cutting a 1.5 cm × 8 cm leaf section by the midrib and placing the remaining petiole section into a 5 mm vial filled with tap water and held in place by cotton around the petiole. The consumed (killed) leafhoppers were identified by their dried and shrunken bodies, and their numbers were daily recorded (initial work with a no-lacewing control established that there was no E. variabilis mortality on the bouquets). After pupation, 3-day-old cocoons were weighed. There were 20 adults tested. The trial was conducted at 26.7 ± 1 °C, 60 ± 10% RH, and a photoperiod of 16L:8D.

2.5. Statistics

Results are presented as sample means ± SE. Analyses were performed using Systat Software Inc. (version 13, San Jose, CA, USA). A nonlinear regression analysis was used to describe the relationship between temperature and C. comanche developmental rate (egg to adult eclosion), using the Brière-2 equation [24,25]:

where T is the rearing temperature (°C), α is a constant fitted to the data, TL is low temperature development threshold, TH is the high temperature threshold, and m is an empirical constant. To better determine the low temperature, data within the mid-range temperature treatments (15.6–32.2 °C) were fit to a linear equation [25], as nonlinear models often provide a poor fit to TL:

where the development rate R(T) is a linear function of temperature, T(°C), a is the intercept of the line and b is the slope of the regression line. The low development threshold is calculated as TL = −a/b, and the thermal constant (k) from birth to adult, in required degree-days (DD), is calculated as k = 1/b [26]. The optimal temperature was then computed as follows [26]:

R(T) = α T (T – TL) (TH − T)(1/m)

R(T) = a + bT

Topt = (2m TH + (m + 1) TL) + ((4m2 TH2 (m + 1)2 TL2 − 4m2 TH TL))0.5/4m + 2

This expression depends only on TH, TL, and m, which were previously determined.

3. Results

3.1. Temperature-Dependent Development

Tested C. comanche completed development at temperatures from 15.6 to 35 °C; eggs did not hatch after 3 weeks, at the lowest (12.7 °C) or highest (36.7 °C) temperatures tested. Therefore, the temperatures tested covered the range of constant temperatures that permit complete development. From egg to adult eclosion, developmental time was longest at 15.6 °C (56.1 ± 2.9 d) and shortest at 32.2 °C (16.7 ± 0.7 d), with development times relatively similar between 26.6 and 29.4 °C and 32.2 and 33.9 °C (Table 1). At all temperatures, development times of all instars (1st to 3rd) were relatively similar to pupal development time, and eggs eclosed in about half that time.

Table 1.

Development time (in days ± SEM) for different life stages of Chrysoperla comanche at seven constant temperatures that permitted complete development.

The linear model, using the mid-range temperatures from 15.6 to 32.2 °C, provided low temperature development rates for egg (10.7 °C, y = −0.167 + 0.015x, R2 = 0.97), first instar (9.7 °C, y = −0.195 + 0.020x, R2 = 0.97), second instar (8.7 °C, y = −0.198 + 0.023x, R2 = 0.95), third instar (8.5 °C, y = −0.179 + 0.021x, R2 = 0.92), and pupa (8.0 °C, y = −0.045 + 0.005x, R2 = 0.92). From egg to adult eclosion, the low temperature threshold was 9.97 °C (y = −0.017 + 0.002x, R2 = 0.97). The corresponding accumulated degree days are 64.4, 49.7, 44.1, 47.8, and 173.2 for egg and first, second, third instar and pupa, respectively; the accumulated degree day from egg to adult emergence is 519.4. The proportion of time spent in each stage was relatively similar for each temperature (15.6–35 °C), ranging from 15.2 to 21.5% (egg), 36.5–44.3% (all instars) and 39.9–46.8 (pupa).

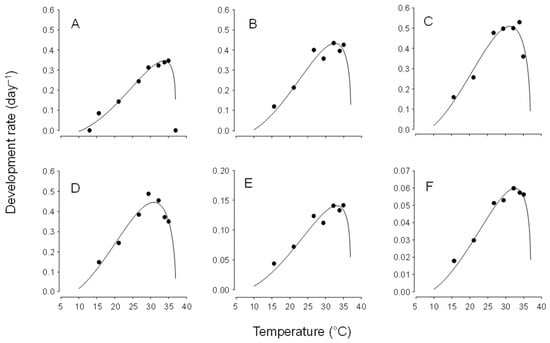

Using these low temperature thresholds and setting the upper threshold at 36 °C (there was complete development at 35 °C and no survival at 36.7 °C), the Briere-2 nonlinear model provided a good fit to the data set for development for egg, larvae, pupa and egg to adult eclosion (Figure 1) and provides Topt as 25.8, 28.2, 28.9, 28.8, 31.6, and 29.7 °C for egg, fist instar, second instar, third instar, pupa and egg to adult eclosion, respectively.

Figure 1.

The relationship between temperature and development rate of Chrysoperla comanche at constant temperatures, as described by the Brière-2 nonlinear model [24] for (A) egg (R2 = 0.97), (B) first instar (R2 = 0.97), (C) second instar (R2 = 0.95), (D) third instar (R2 = 0.92), (E) pupa (R2 = 0.92) and (F) egg to adult eclosion (R2 = 0.97).

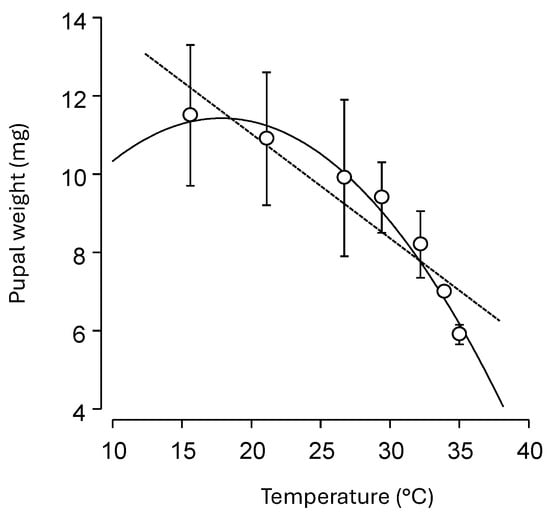

Weight of 3-day-old pupae ranged from 11.5 ± 1.8 mg at 15.6 °C to 5.9 ± 0.25 mg at 35 °C. Weight was negatively associated with increasing temperature using a linear model (y = 16.37 − 0.27x; R2 = 0.84, F = 33.19, df = 1.6, p = 0.002; Figure 2, dashed line). A simple quadratic equation better captured the decline in weight at both lower and upper temperatures to show a negative relationship with a sharp decline as temperatures reached the lethal limits (y = 5.78 + 0.629x − 0.018x2; R2 = 0.96, F = 1417.8, df = 3.7, p < 0.001; Figure 2, solid line).

Figure 2.

Relationship between constant temperature and average (±SEM) weight of 3-day-old cocoons of Chrysoperla comanche; dashed line fits data to a linear model, solid curve fits data to a simple quadratic model.

3.2. Adult Fecundity and Longevity

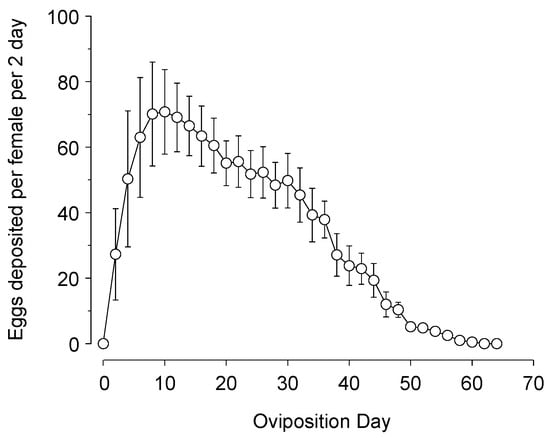

Adults had an average of 5.8 ± 0.9-day pre-ovipositional period and deposited an average of 1087.2 ± 199.5 eggs over the lifetime of 53.6 ± 10.2 days (Figure 3). Egg production reached a peak in about 10 days and steadily declined thereafter, with 80.9% of eggs deposited in the first 30 days of oviposition.

Figure 3.

Lifetime fecundity of Chrysoperla comanche (eggs per 2 days ± SEM) when fed an artificial diet made of whey yeast, enzymatic protein hydrolysate of brewer’s yeast, honey and water (6:1:10:5).

Overwintered adults continuously deposited eggs from 26 October to 7 January. Eggs deposited from 16 to 19 November hatched from 7 to 13 January after 49–53 days at an average temperature of 7.8 °C (range −7.7 to 26.7 °C). Adult C. comanche were collected from grape vines and prune trees at KREC in mid-November, when all or most leaves had senesced and dropped, and collected C. comanche adults were green in color (compared to the brown color of diapausing C. carnea). Therefore, it appears that C. comanche does not enter a diapause in winter in California’s San Joaquin Valley.

3.3. Prey Consumption

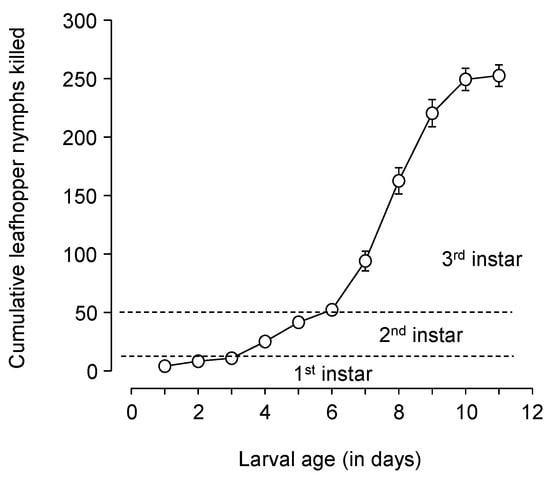

Larvae consumed or killed 252.6 ± 9.2 late-instar E. variabilis in an average 9.6 ± 0.2-day larval development period. More leafhoppers were consumed in the third instar (200.2 ± 8.6) than in the second instar (41.4 ± 3.0), which consumed more than the first instar (10.9 ± 1.2) (F = 371.02, DF = 2.39, p < 0.001; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Chrysoperla comanche cumulative consumption of late instar (4th and 5th instar) leafhopper nymphs, in a controlled environment with prey provided in excess, showing more consumption in the lacewing’s 3rd instar than the 1st and 2nd instars combined. The dashed lines show the approximate time periods for the three instars at 26.7 °C.

4. Discussion

Two Chrysoperla species dominate the commercial insectary market—C. carnea and C. rufilabris in North America [27] and C. carnea in Europe [5,28]. Other species have been occasionally available, such as C. externa and C. nipponensis (Okamoto, 1914) in Latin America and Asia [29,30]. Still, there have been many studies indicating that other lacewing species are better suited to some environments or against some targeted pests—based on the presence of different species, e.g., [14,31]. For example, the brown lacewing Micromus angulatus (Stephens, 1836) and Chrysopa formosa (Brauer, 1851) were shown to control the green peach aphid Myzus persicae (Sulzer, 1776) on peppers, and the authors highlight the potential of these two widespread but overlooked species for use in biological pest control [16]. Cortez-Mondaca et al. [15] showed that Ceraeochrysa cubana (Hagen, 1861) and C. externa were abundant in sorghum fields infested with sugarcane aphid, Melanaphis sacchari (Zehntner, 1897) in Mexico and suggested the mass rearing and release of C. cubana. Finally, Koutsoula et al. [14] showed that C. agilis (in the carnea species group) and Chrysoperla mutata (McLachlan, 1898) (in the pudica species group) were efficient in controlling aphids and mealybugs on sweet pepper and suggested their use in pest control programs. This study focused on C. comanche, which is considered to be native to western North America. The natural range of C. comanche appears to be better suited to warm-hot, dry habitats, and there are numerous reports of C. comanche’s importance in agricultural systems within this region. For example, C. comanche and C. nigricornis were abundant in western US pecan trees feeding on two specialist aphids, Monellia caryella (Fitch, 1855) and Melanocallis caryaefoliae (Davis, 1910) [32]. In a glasshouse study in Mexico, C. comanche, along with C. externa, was shown to reduce tomato fruit damage from Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande, 1895) [33]. Here, the development, larval food consumption and adult fecundity of C. comanche were determined to better compare this lacewing species to C. carnea and C. rufilabris that are most commonly used in augmentation programs.

The developmental time for C. comanche was 15.4 days at 26.7 °C from neonate first instar to adult eclosure (Table 1). The proportion of total developmental time that C. comanche spent in the egg, larval and pupal stages was relatively similar among temperatures, suggesting rate isomorphy [34]. In comparison, Peterson and Hunter [32] report a slightly faster time of 16.4 days (females) and 16.0 days (males) at 27 °C, the only other developmental study found for C. comanche. In their study, C. comanche was fed the pecan aphids M. caryella and M. caryaefoliae, which may have slowed development time because of the additional energy used and handling time for prey capture. The cocoon weight (9.9 mg) reported herein was also larger than the 9.5 mg (females) and 7.7 mg (males) reported [32], but this might have also been a result of different diets and the fact that female and male specimens were not weighed separately. Many factors can impact development time, making comparisons of different studies difficult. For example, C. carnea that were resistant to Spinosad had a shorter development time than a susceptible population [35], C. carnea fed increasing prey (aphids) densities had reduced developmental time [36,37], and C. rufilabris fed pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum (Harris, 1776), reared on alfalfa developed faster than those fed pea aphids reared on faba beans [38]. Even in this study, the developmental time of larvae fed leafhopper nymphs was a day longer compared to larvae fed moth eggs held at the same temperature.

Work conducted on C. carnea, C. rufilabris and other Chrysoperla spp. suggests that developmental times are, within reason, similar to C. comanche. For example, Amarasekare and Shearer [39] report that C. carnea and C. johnsoni Henry et al., 1993 developed from egg to adult, at 23 °C, in 28.5 and 31.8 days, respectively. Giles et al. [38] report that C. rufilabris developed from egg to adult, at 22 °C, in 22 and 24.1 days when fed pea aphids reared on alfalfa and faba beans, respectively. These development times are comparable to C. comanche developmental times of 33.6 and 19.5 days, at 21.1 and 26.7 °C, respectively (Table 1). Fewer studies used a range of constant temperatures to determine lower and upper thresholds. Aghdam and Nemati [40] investigated the C. carnea developmental rate at seven constant temperatures and analyzed that data with nonlinear models. Their reported lower and upper temperature thresholds were higher and lower, respectively, at each developmental stage for C. carnea than those reported here for C. comanche. Similarly, Butler and Ritchie [41] report that C. carnea upper threshold temperatures were about 2 °C lower, for each life stage, than C. comanche reported here. Thus, C. comanche is probably better adapted to warmer than cooler regions as compared with C. carnea. The estimated upper threshold for C. comanche (36.5 °C) is not outside of that reported for other chrysopids, with Pappas et al. [42] reporting Chrysoperla agilis. Henry et al. 2003 reported a European chrysopid in the C. carnea group, with a lower threshold between 11.4 and 11.8 °C and an upper threshold between 36.6 and 36.9 °C for females and males, respectively.

Weight of 3-day-old C. comanche pupae was negatively associated with increasing temperature, with a sharper decline near the upper temperature threshold. For many species, the temperature-size rule suggests that insects reared at cooler temperatures develop more slowly but reach a larger final body size and mass than those raised in warmer conditions [43]. Chrysoperla comanche larvae consumed or killed >250 late-instar E. variabilis in about a 10-day larval development period. Based on the size difference between first instar leafhoppers and the late instars used in the trial, the C. comanche larvae are probably capable of consuming >1000 early instar leafhoppers. Under field conditions, larvae should be expected to consume fewer prey and will probably require a longer development time, because of additional searching time and energy consumption used to find prey. No other studies detail Chrysoperla spp. consumption of leafhoppers; however, Luna-Espinosa et al. [33] investigated predation of adult F. occidentalis on tomato by C. comanche and C. externa larvae and showed relatively similar numbers of 258 and 297 prey killed, respectively. Still, direct comparison is difficult as the researchers used a 24 h period for each lacewing stage, thus reducing the total lifetime consumption, but they did show a similar trend of greater consumption by the later lacewing instars.

Many feeding studies have used moth eggs or aphids as prey, with results commonly showing that C. carnea or C. rufilabris will consume 100s to 1000s of moth eggs, e.g., [37,44,45,46,47,48] or 100s of aphids, e.g., [47,49,50,51]. Basically, most Chrysoperla spp. are generalist predators of soft-bodied insects and mites, a trait that underlies their great commercial demand. Still, Chrysoperla spp. prey preferences can vary [47,52,53] and could be better defined among species to provide reliable recommendations for the improved use of Chrysoperla species and biotypes against specific types of pests [1,54]. Moreover, laboratory prey consumption studies indicate that lacewings can feed and develop on specific prey species, but their effectiveness in the field can be quite different depending on conditions at the release site [55]. As examples, smooth or hirsute cotton leaves affect C. rufilabris larval mobility and prey consumption [56], and the structure of cabbage and wheat plants impacts the effectiveness of C. carnea [49,57]. Even more subtle differences can occur—in pecan, C. rufilabris can feed on the aphids M. caryella, M. caryaefoliae, and Monelliopsis pecanis Bissell, 1983, but will lay more eggs on trees infested with the M. caryella [58].

Chrysoperla comanche oviposited >1000 eggs over about 55 days, with about a 6-day pre-ovipositional period. While the recorded fecundity may seem high, it is actually in line with other studies that used well-fed larvae and an artificial diet to increase adult longevity. Amarasekare and Shearer [39] report that C. carnea and C. johnsoni had a lifetime fecundity of 1264 and 960 eggs per female, respectively. Greenberg et al. [59] reported C. rufilabris with 440.6 to 802.6 eggs per female, depending on larval prey species. What is clear is that adult Chrysoperla spp. fecundity is dependent on larval diet, with Zheng et al. [37] reporting 217 to 1205 eggs per female from low to high prey densities of E. kuehniella moth eggs and Athhan et al. [36] reporting 514.2 to 806.6 eggs per female fecundity from low to high densities of Hyalopterus pruni (Geoffer, 1762) aphid nymphs. Adult females that developed from the high feeding treatment not only had higher fecundity but also a substantially shorter preoviposition period and a later decline in egg deposition as well [37].

5. Conclusions

Here, the development, larval food consumption and adult fecundity of C. comanche were compared with the commercially available C. carnea and C. rufilabris. At the onset of this study, the objective was to determine if C. comanche might be a better fit for augmentative release in perennial crops in California’s interior valleys. Clearly, there are differences among lacewing species; for example, C. carnea does well under low humidity and could be released in hot, dry agricultural settings, whereas C. rufilabris does better under high humidity and might be best used in greenhouses rather than the desert southwest of the USA [1]. Here, we showed that, while most biological traits were similar, C. comanche had a higher temperature threshold, and adults appeared not to enter a winter diapause in California’s San Joaquin Valley. Still, a general call for greater species diversity among commercially available Chrysoperla spp. may not be feasible. At the insectary level, first, there is now a more global market for beneficial insects, and import/export permit regulations for international shipment of an even greater number of beneficial insects would be impractical. Second, mass rearing of closely related species at one facility could be problematic because of contamination of insect colonies, and that would then require more costly examination of product for species identification before shipments. Third, product loyalty for the different generalist natural enemies would be disrupted by consumers trying different lacewing species without a clear understanding of each species best usage practices, whereas C. carnea and C. rufilabris have been known commodities for some time.

At the field level, it has been abundantly clear that release rates, release methods and release environment probably have more impact on Chrysoperla than differences among species or biotypes. For example, lacewing releases reduced aphid abundance in apples, but release efficacy is dependent on release method, life stage, and timing [60]. There is also the potential impact of intraguild predation that could release efficiency [61,62,63]. For example, the Argentine ant, Linepithema humile (Mayr, 1868), removed 98% of the C. carnea eggs that were dispensed on tulip trees to control the aphid Illinoia liriodendri (Monell, 1879) [64]. Therefore, while the data presented here suggest that C. comanche has potential as a biological control agent of E. variabilis, it may be unreasonable to call for the larger commercial insectaries to offer C. comanche as a mass-produced beneficial arthropod—or any of the other lacewing species discussed. Rather, specialty crop systems and beneficial arthropods that are especially advantageous for specific situations might best be produced by cooperatives or larger farm operations that address specific pest needs that cannot be met by one of the hundreds of beneficial arthropods currently under commercial production.

Funding

This research was funded by the California Table Grape Commission, the American Vineyard Foundation, and the University of California’s Statewide IPM Program.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

I thank Yuwei Zheng for initiating this project with data collection and developing an initial manuscript and Yvonne Rasmussen and Glenn Yokota for additional data collection. I thank Lynn LeBeck for reviewing an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviation is used in this manuscript:

| DDs | Degree Days |

References

- Tauber, M.J.; Tauber, C.A.; Daane, K.M.; Hagen, K.S. Commercialization of predators: Recent lessons from green lacewings (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae: Chrosoperla). Am. Entomol. 2000, 46, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour, M.; Asadi, M.; Jooyandeh, A.; Madadi, H. Lacewings: Research and applied aspects. In Biological Control of Insect and Mite Pests in Iran; Karimi, J., Madadi, H., Eds.; Progress in Biological Control; Springer: Cham, Swizerlands, 2021; Volume 18, pp. 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, P.K.; New, T.R.; Whittington, A.E. (Eds.) Lacewings in the Crop Environment; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- vanLenteren, J.C.; Roskam, M.M.; Timmer, R. Commercial mass production and pricing of organisms for biological control of pests in Europe. Biol. Control 1997, 10, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemanski, K.; Herz, A. Commercial availability of invertebrate biological control agents targeting plant pests in Germany. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2025, 132, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Alcalá, A.; Rodríguez-Leyva, E.; Lomeli-Flores, J.R.; Guzmán-Franco, A.W.; Velázquez-González, J.C. Combining a predator and a parasitoid for biological control of Phenacoccus madeirensis (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae). Biocontrol 2025, 70, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehler, L.E.; Long, R.F.; Kinsey, M.G.; Kelley, S.K. Potential for augmentative biological control of black bean aphid in California sugarbeet. BioControl 1997, 42, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutson, A.E.; Tedders, L. Augmentation of green lacewing, Chrysoperla rufilabris, in cotton in Texas. Southwest Entomol. 2002, 27, 231–239. [Google Scholar]

- Breene, R.G.; Meagher, R.L.; Nordlund, D.A.; Wang, Y.T. Biological control of Bemisia tabaci (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae) in a greenhouse using Chrysoperla rufilabris (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae). Biol. Control 1992, 2, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daane, K.M.; Hagen, K.S. An evaluation of lacewing releases in North America. In Lacewings in the Crop Environment; McEwen, P.K., New, T.R., Whittington, A.E., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 2000; pp. 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, J.F.; Mendes, S.; Alves da Silva, A.; Sousa, J.P.; Paredes, D. Land-use effect on olive groves pest Prays oleae and on its potential biocontrol agent Chrysoperla carnea. Insects 2021, 12, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, J.P. Problems inherent to augmentation of natural enemies in open agriculture. Neotrop. Entomol. 2018, 47, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, T.; Van Steenwyk, R. A critical evaluation of augmentative biological control. Biol. Control 2004, 31, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoula, G.; Stamkopoulou, A.; Pekas, A.; Wäckers, F.; Broufas, G.; Pappas, M.L. Predation efficiency of the green lacewings Chrysoperla agilis and C. mutata against aphids and mealybugs in sweet pepper. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2023, 113, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez-Mondaca, E.; López-Buitimea, M.; López-Arroyo, J.I.; Orduño-Cota, F.J.; Herrera-Rodríguez, G. Chrysopidae species associated with the sugarcane aphid in northern Sinaloa, Mexico. Southwest. Entomol. 2016, 41, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntalia, P.; Broufas, G.D.; Wäckers, F.; Pekas, A.; Pappas, M.L. Overlooked lacewings in biological control: The brown lacewing Micromus angulatus and the green lacewing Chrysopa formosa suppress aphid populations in pepper. J. Appl. Entomol. 2022, 146, 796–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauber, M.J.; Tauber, C.A. Life history traits of Chrysopa cornea and Chrysopa rufilabris (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae): Influence of humidity. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1983, 76, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerling, D.; Kravchenko, V.; Lazare, M. Dynamics of common green lacewing (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) in Israeli cotton fields in relation to whitefly (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae) populations. Environ. Entomol. 1997, 26, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senior, L.J.; McEwen, P.K. Laboratory study of Chrysoperla carnea (Stephens) (Neuropt., Chrysopidae) predation on Trialeurodes vaporariorum (Westwood) (Hom., Aleyrodidae). J. Appl. Entomol. 1998, 122, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, C.H.; Dmitriev, D.A. Review of the new world genera of the leafhopper tribe Erythroneurini (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae: Typhlocycbinae). Ill. Nat. Hist. Surv. Bull. 2006, 37, 119–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daane, K.M.; Yokota, G.Y. Release strategies affect survival and distribution of green lacewings (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) in augmentation programs. Environ. Entomol. 1997, 26, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daane, K.M.; Yokota, G.Y.; Zheng, Y.; Hagen, K.S. Inundative release of common green lacewings, (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) to suppress Erythroneura variabilis and E. elegantula (Homoptera: Cicadellidae) in vineyards. Environ. Entomol. 1996, 25, 1224–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.B.; Hagen, K.S. A neuropterous larva uses an allomone to attack termites. Nature 1981, 289, 506–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briere, J.F.; Pracros, P.; Le Roux, A.Y.; Pierre, J.S. A novel rate model of temperature-dependent development for arthropods. Environ. Entomol. 1999, 28, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekera, M.J.; Acharya, R.; Mostafiz, M.M.; Hwang, H.S.; Bhusal, N.; Lee, K.Y. Temperature-dependent development models describing the effects of temperature on the development of the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Insects 2022, 13, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, N.; Brière, J.F.; Fargues, J. Comparison of non-linear temperature-dependent development rate models applied to in vitro growth of entomopathogenic fungi. Mycol. Res. 2003, 107, 1476–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBeck, L.M.; Leppla, N.C. Guidelines for Purchasing and Using Commerical Natural Enemies in North America; The Association of Natural Biocontrol Producers and University of Florida, Entomology and Nematology Department: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2023; Available online: https://anbp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Guidelines_for_Natural_Enemies_2021.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- EPPO. PM 6/3 (5) Biological control agents safely used in the EPPO region. EPPO Bull. 2021, 51, 452–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Nordlund, D.A. Use of Chrysoperla spp. (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) in augmentation release programmes for control of arthropod pests. BioControl News Inf. 1994, 15, 51N–57N. [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez, E.Z. Chrysopidae (Neuroptera) del Perú y sus especies más comunes. Rev. Peurivian Entomol. 1989, 31, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, M.J.; Daane, K.M. Abundance of spiders and insect predators on grapes in central California. J. Arachnol. 1999, 27, 531–538. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, M.K.; Hunter, M.S. Ovipositional preference and larval—Early adult performance of two generalist lacewing predators of aphids in pecans. Biol. Control 2002, 25, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Espino, H.M.; Jiménez-Pérez, A.; Castrejón-Gómez, V.R. Assessment of Chrysoperla comanche (Banks) and Chrysoperla externa (Hagen) as biological control agents of Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande) (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) on tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) under glasshouse conditions. Insects 2020, 11, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarošík, V.; Honěk, A.; Dixon, A.F.G. Developmental rate isomorphy in insects and mites. Am. Nat. 2002, 160, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, N.; Mansoor, M.M.; Shad, S.A.; Pathan, A.K.; Waheed, A.; Ejaz, M.; Razaq, M.; Zulfiqar, M.A. Fitness cost and realized heritability of resistance to spinosad in Chrysoperla carnea (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae). Bull. Entomol. Res. 2014, 104, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlıhan, R.; Kaydan, B.; Özgökçe, M.S. Feeding activity and life history characteristics of the generalist predator, Chrysoperla carnea (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) at different prey densities. J. Pest Sci. 2004, 77, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Daane, K.M.; Hagen, K.S.; Mittler, T.E. Influence of larval food consumption on the fecundity of the lacewing Chrysoperla carnea. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1993, 67, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, K.L.; Madden, R.D.; Payton, M.E.; Dillwith, J.W. Survival and development of Chrysoperla rufilabris (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) supplied with pea aphids (Homoptera: Aphididae) reared on alfalfa and faba bean. Environ. Entomol. 2000, 29, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasekare, K.G.; Shearer, P.W. Comparing effects of insecticides on two green lacewings species, Chrysoperla johnsoni and Chrysoperla carnea (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2013, 106, 1126–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghdam, H.R.; Nemati, Z. Modeling of the effect of temperature on developmental rate of common green lacewing, Chrysoperla carnea (Steph.) (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae). Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control. 2020, 30, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, G.D.; Ritchie, P.L., Jr. Development of Chrysopa carnea at constant and fluctuating temperatures. J. Econ. Entomol. 1970, 63, 1028–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, M.L.; Karagiorgou, E.; Papaioannou, G.; Koveos, D.S.; Broufas, G.D. Developmental temperature responses of Chrysoperla agilis (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae), a member of the European carnea cryptic species group. Biol. Control 2013, 64, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, R.J.; Hassall, M. The temperature-size rule in ectotherms: May a general explanation exist after all? Am. Nat. 2006, 167, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadek, H.E.; Moawad, S.S.; Ebadah, I.M.; Momen, F. Predation, fecundity and life table parameters of Chrysoperla carnea Stephens, 1836 (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) on two factitious preys. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2025, 58, 490–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legaspi, J.C.; Carruthers, R.I.; Nordlund, D.A. Life-history of Chrysoperla rufilabris (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) provided sweet-potato whitefly Bemisa tabaci (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae) and other food. Biol. Control 1994, 4, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, B.; Obrycki, J.J. Prey suitability of Galerucella calmariensis L. (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) and Myzus lythri (Schrank) (Homoptera: Aphididae) for development of three predatory species. Environ. Entomol. 2006, 35, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordlund, D.A.; Morrison, R.K. Handling time, pre preference, and functional response for Chrysoperal rufilabris in the laboratory. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1990, 57, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Araiza, M.D.; Díaz-García, J.A.; Martínez-Jaime, O.A. Survival and reproduction of Chrysoperla carnea (Stephens) fed different diets. Southwest. Entomol. 2015, 40, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, F.J.; Jones, T.A.; Nielson, D.C. Host plant affects the interaction beyween the Russian wheat aphid and a generalist predator, Chrysoperla carnea. J. Kans. Entomol. Soc. 1995, 68, 313–319. [Google Scholar]

- Zarei, M.; Madadi, H.; Zamani, A.A.; Nedved, O. Predation rate of competing Chrysoperla carnea and Hippodamia variegata on Aphis fabae at various prey densities and arena complexities. Bull. Insectology 2019, 72, 273–280. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, N.X.; Enkegaard, A. Predation capacity and prey preference of Chrysoperla carnea on Pieris brassicae. Biocontrol 2010, 55, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shands, W.A.; Simpson, G.W.; Gordon, C.C. Insect predators for controlling aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae) on potatoes. 5. Numbers of eggs and schedules for introdcuing them in large field cages. J. Econ. Entomol. 1972, 65, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrycki, J.J.; Hamid, M.N.; Sajap, A.S.; Lewis, L.C. Suitability of corn insect pests for development and survival of Chrysoperla carnea and Chrysopa oculata (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae). Environ. Entomol. 1989, 18, 1126–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Marco, F.; Gebiola, M.; Simmons, G.S.; Stouthamer, R. Native, naturalized and commercial predators evaluated for use against Diaphorina citri. Crop. Prot. 2022, 155, 105907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daane, K.M. Ecological studies of released lacewings in crops. In Lacewings in the Crop Environment; McEwen, P.K., New, T.R., Whittington, A.E., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 2000; pp. 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treacy, M.F.; Benedict, J.H.; Lopez, J.D.; Morrison, R.K. Functional response of a predator (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) to bollworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) eggs on smooth leaf, hirsute, and pilose cotton. J. Econ. Entomol. 1987, 80, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigenbrode, S.D.; Castagnola, T.; Roux, M.B.; Steljes, L. Mobility of three generalist predators is greater on cabbage with glossy leaf wax than on cabbage with a wax bloom. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1996, 81, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunkel, B.A.; Cottrell, T.E. Oviposition response of green lacewings (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) to aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae) and potential attractants on pecan. Environ. Entomol. 2007, 36, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, S.M.; Nordlund, D.A.; King, E.G. Influence of different larval feeding regimes and diet presentation methods on Chrysoperla rufilabris (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) development. J. Entomol. Sci. 1994, 29, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Jeffris, R.A.; Moretti, E.A.; Hausler, D.; Taylor, K.L.; Ohler, B.J.; Tempest, H.; Cooper, W.R. Augmentative releases of insectary-reared lacewings for aphid control in apples. Biol. Control 2025, 208, 105833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, M.; Madadi, H.; Zamani, A.A.; Nedvěd, O. Intraguild predation between Chrysoperla carnea (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) and Hippodamia variegata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) at various extraguild prey densities and arena complexities. Insects 2020, 11, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoofolo, M.W.; Obrycki, J.J. Potential for intraguild predation and competition among predatory Coccinellidae and Chrysopidae. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1998, 89, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golsteyn, L.; Mertens, H.; Audenaert, J.; Verhoeven, R.; Gobin, B.; De Clercq, P. Intraguild Interactions between the Mealybug Predators Cryptolaemus montrouzieri and Chrysoperla carnea. Insects 2021, 12, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreistadt, S.H.; Hagen, K.S.; Dahlsten, D.L. Predation by Iridomyrmex humilis [Hym.: Formicidae] on eggs of Chrysoperla carnea [Neu.: Chrysopidae] released for inundative control of Illinoia liriodendri [Hom.; Aphididae] infesting Liriodendron tulipifera. Entomophaga 1986, 31, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).