Simple Summary

Xinjiang is the largest cotton-producing area in China. In recent years, thrips pests have become an increasing concern in cotton fields in Xinjiang. Currently, controlling thrips in cotton fields relies heavily on the use of synthetic insecticides. However, limited studies have been reported on controlling thrips (Frankliniella intonsa) during flowering and boll stages. In this study, we evaluated the susceptibility of F. intonsa populations collected from different geographical sites across major cotton planting areas in Xinjiang to three insecticides: spinetoram, imidacloprid, and acetamiprid. We found that F. intonsa populations were highly susceptible to spinetoram, indicating that this insecticide could effectively control this pest in Xinjiang’s cotton fields. Susceptibility to imidacloprid and acetamiprid varied considerably among different field populations, with reduced susceptibility observed in locations such as Korla and Manasi. These results provide useful information for appropriate chemical control of F. intonsa.

Abstract

Thrips pests have become an increasing concern in cotton fields in Xinjiang. Frankliniella intonsa is the primary thrips species during the flowering and boll stages, causing boll stiffening or cracking. However, limited studies have been conducted on controlling F. intonsa. In this study, using a leaf-tube residue method, we evaluated the susceptibility of F. intonsa field populations to three insecticides (spinetoram, imidacloprid, and acetamiprid) collected from different geographical sites across major cotton planting areas in Xinjiang. The results showed that F. intonsa populations exhibited very high susceptibility to spinetoram, ranging from 0.003 mg L−1 in the Shihezi population to 0.036 mg L−1 in the Korla population. The susceptibility of F. intonsa to imidacloprid and acetamiprid varied considerably among different field populations, with the relative resistance of 33.00 and 25.71, respectively. Reduced susceptibility to all three insecticides was detected in the Korla and Manasi populations, highlighting the importance of implementing effective resistance management and alternative control strategies. These findings provide valuable information for the appropriate control of F. intonsa in Xinjiang.

1. Introduction

Xinjiang is the largest cotton-producing area in China, with its planting area and cotton yield accounting for 85.0% and 91.0% of the total nationwide in 2023, respectively [1]. Cotton has been one of the most important crops in Xinjiang, with its planting area (2.37 million hectares) accounting for 34.6% of the total crop planting area in the region, which far exceeds that of corn (1.44 million hectares) and wheat (1.21 million hectares) [1]. The layout of cotton planting areas in Xinjiang presents a clear trend of centralization, but in some areas, cotton fields are interwoven with other crops, such as corn, orchards, and vegetables. Cotton pests have been constant threats to cotton production in China, especially in Xinjiang [2,3]. In recent years, thrips pests have become a growing concern in Xinjiang’s cotton fields, with Thrips tabaci Lindeman and Frankliniella intonsa Trybom as the dominant species [4,5]. Thrips damage cotton plants at various growth stages. During the seedling stage, thrips (mainly T. tabaci) damage cotton by directly feeding on cotyledons and developing true leaves, resulting in malformation, tearing of leaves, and apical meristem damage. This leads to symptoms such as “headless cotton”, “multi-headed cotton”, and even seedling death [6,7]. During the flowering and boll stages, F. intonsa becomes the main thrips species. Frankliniella intonsa is a common flower-inhabiting thrips on many plants. It damages plants through direct feeding, oviposition, and indirect transmission of plant viruses. Its high reproductive capacity and short generation times lead to rapid population increase and severe damage to cotton flowers and bolls, causing boll stiffening or cracking, which directly affects the cotton yield [7,8].

Management of thrips pests in the field mainly depends on the frequent application of insecticides, including neonicotinoids, organophosphates, pyrethroids and carbamates [9,10], which has led to the development of insecticide resistance in many thrips species, such as Frankliniella occidentalis [11], T. tabaci [12,13], and Thrips palmi [14,15]. Understanding the susceptibility of thrips species in the field will assist in making informed decisions about chemical control. Currently, the control of thrips in cotton fields heavily relies on the application of synthetic insecticides [16]. Neonicotinoids, spinosyns, and diamides are commonly used insecticides for thrips control. Neonicotinoid seed treatments (such as thiamethoxam and imidacloprid), along with foliar-applied insecticides, have been widely used for thrips control in early season [16]. However, widespread and variable resistance to neonicotinoids has been reported in Frankliniella fusca on cotton in the Southeast and Mid-South United States [17]. Conversely, limited studies are available on the control of thrips (F. intonsa) during flowering and boll stages in China, except for a recent study on the application of spinosyns and diamide insecticides (e.g., spinetoram and cyantraniliprole) during flowering stage [18].

Due to variations in insecticide application history across different geographical locations, the susceptibility of thrips to insecticides varied considerably [19,20]. Recently, resistance to several insecticides (e.g., imidacloprid, flupyradifurone) has been reported in F. intonsa in Xinjiang cotton fields [21]. Evaluating the insecticide susceptibility of thrips will help in making informed decisions regarding appropriate chemical control strategies. Spinosyns, such as spinosad and spinetoram, are currently among the most effective insecticides for thrips control [22]. Neonicotinoids, including imidacloprid and acetamiprid, have been widely used against sucking pests on cotton [23,24,25]. We hypothesize that selection pressures in different regions lead to variations in susceptibility. In this study, we evaluated the susceptibility of F. intonsa populations from different geographical sites in Xinjiang to three insecticides: spinetoram, imidacloprid, and acetamiprid. The results provide a foundation for developing management strategies and aid in making decisions on appropriate chemical control of F. intonsa in Xinjiang.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Populations

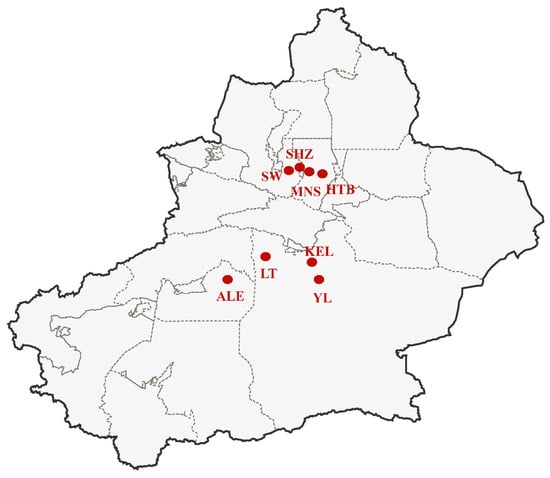

Field Frankliniella intonsa populations were collected from cotton flowers at 8 geographical sites across the major cotton planting areas in Xinjiang in 2023 (Figure 1, Table 1). Cotton flowers infested with thrips were collected, temporarily maintained in glass jars in climate chambers (25 ± 1 °C, 60% ± 5% RH, 16 h: 8 h L: D photoperiod) for less than 48 h, and subsequently used for bioassays. In each location, more than 3000 thrips were collected.

Figure 1.

Map of sampling sites of Frankliniella intonsa from cotton fields in Xinjiang. ALE: Alaer, Aksu; KEL: Korla, Bayingolin; YL: Yuli, Bayingolin; LT: Luntai, Bayingolin; SW: Shawn, Tacheng; HTB: Hutubi, Changji; MNS: Manasi, Changji; SHZ: Shihezi, Shihezi.

Table 1.

Sample collection information for field populations of Frankliniella intonsa on cotton flowers.

2.2. Insecticides

Three insecticides were used in the bioassays: spinetoram 6% SC (Formulation: soluble concentrate; Trade name: Exalt; Supplier: Dow AgroSciences, Indianapolis, IN, USA; Application rate: 30~60 mg L−1); imidacloprid 70% WDG (Formulation: Water Dispersible Granule; Trade name: Admire; Supplier: Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany; Application rate: 35~50 mg L−1); acetamiprid 50% WDG (Formulation: Water Dispersible Granule; Trade name: Yicheng; Supplier: Sichuan Runer Technology, Chengdu, China; Application rate: 25~75 mg L−1).

2.3. Bioassays

A leaf-tube residue method was used to test the susceptibility of F. intonsa to three insecticides [26]. Each insecticide was serially diluted to five to seven concentrations with distilled water containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (Beijing Solar Bio Science and Technology Co. Ltd., Beijing, China) to obtain the mortality rate in the range of 20~80%. The concentrations of spinetoram were 0.005, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1, and 5 mg L−1. The concentrations of imidacloprid were 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, and 500 mg L−1. The concentrations of acetamiprid were 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, and 50 mg L−1. A solution of distilled water with 0.1% Triton X-100 served as the control, and the control mortality rate was kept below 10%. Centrifuge tubes (1.5 mL) were treated by filling with the diluted solutions for 4 h and then dried for 2 h. The bottom of each tube was cut to create a small hole, through which thrips were aspirated into the tube by a pump. Cabbage leaf discs (Brassica oleracea L.) with a diameter of 1 cm were dipped into the dilutions for 10 s and dried for 30 min. The dried leaf discs were transferred individually into the tubes treated with the same concentration. Ten adult female thrips were aspirated into each tube through the hole, after which the hole was sealed with parafilm. Four to five replicates were prepared for each insecticide at each concentration. The treated thrips were placed in climate chambers (25 ± 1 °C, 60% ± 5% RH, 16 h: 8 h L: D photoperiod). Mortality was assessed 24 h after treatment. Thrips unable to move were considered dead.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The mortality data were analyzed by probit analysis using POLO Plus software Version 2.0. The estimated parameters included the LC50 value (median lethal concentration) and LC90 value of active ingredient (90% lethal concentration) with 95% CI (confidence intervals) and the slope of the regression line. LC50 values were considered to be significantly different if their 95% CI did not overlap. Relative resistance was calculated by dividing the LC50 of a population by the lowest LC50.

3. Results

3.1. Susceptibility of Field Populations of Frankliniella intonsa to Spinetoram

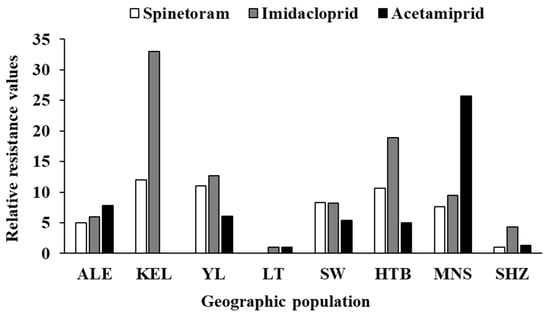

Field populations of F. intonsa from Xinjiang cotton fields showed very high susceptibility to spinetoram (Table 2). The LC50 values for all seven populations were below 0.05 mg L−1, ranging from 0.003 mg L−1 in Shihezi (SHZ) to 0.036 mg L−1 in Korla (KEL) (Table 2). The LC90 values ranged from 0.024 mg L−1 in Shihezi (SHZ) to 0.142 mg L−1 in Korla (KEL) (Table 2). The Shihezi (SHZ) and Alaer (ALE) populations were the most susceptible, with LC50 values below 0.02 mg L−1 and LC90 values below 0.1 mg L−1 (Table 2). Based on the overlap of 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) from the LC50, the SHZ population showed significantly higher susceptibility than all others. The Alaer (ALE) population was more susceptible than the KEL and Yuli (YL) populations (Table 2). Although the KEL population had the highest LC50 and LC90, there were no significant differences among KEL, YL, Shawan (SW), Hutubi (HTB) and Manasi (MNS) populations (Table 2). The greatest difference in toxicity was between populations from SHZ and KEL, with a relative resistance of 12.00 (Table 2, Figure 2).

Table 2.

Susceptibility of field populations of Frankliniella intonsa to spinetoram.

Figure 2.

The relative resistance of different Frankliniella intonsa geographic populations to three insecticides. ALE: Alaer, Aksu; KEL: Korla, Bayingolin; YL: Yuli, Bayingolin; LT: Luntai, Bayingolin; SW: Shawn, Tacheng; HTB: Hutubi, Changji; MNS: Manasi, Changji; SHZ: Shihezi, Shihezi.

3.2. Susceptibility of Field Populations of Frankliniella intonsa to Imidacloprid

Susceptibility to imidacloprid varied considerably among different field populations of F. intonsa in Xinjiang (Table 3). The LC50 values of the eight populations ranged from 4.361 mg L−1 in Luntai (LT) to 143.930 mg L−1 in Korla (KEL) (Table 3). The LC90 values ranged from 151.278 mg L−1 in Luntai (LT) to 4771.991 mg L−1 in Korla (KEL) (Table 3). Based on 95% CI comparisons of LC50, the LT population was significantly more susceptible to imidacloprid than all other populations except Shihezi (SHZ) (Table 3). The KEL population was the least susceptible, with the LC50 and LC90 values significantly higher than those of the LT, SHZ, ALE, SW and MNS populations (Table 3). No significant differences were detected in LC50 values among KEL, YL, and HTB populations (Table 3). The highest difference in toxicity was between the populations from LT and KEL, with a relative resistance of 33.00 (Table 3, Figure 2).

Table 3.

Susceptibility of field populations of Frankliniella intonsa to imidacloprid.

3.3. Susceptibility of Field Populations of Frankliniella intonsa to Acetamiprid

The susceptibility of F. intonsa populations to acetamiprid also varied (Table 4). The LC50 values of the seven populations ranged from 1.873 mg L−1 in Luntai (LT) to 48.154 mg L−1 in Manasi (MNS) (Table 4). The LC90 values ranged from 27.068 mg L−1 in Luntai (LT) to 172.306 mg L−1 in Manasi (MNS) (Table 4). Based on the overlap of 95% CI from the LC50, the LT population was significantly more susceptible to acetamiprid than all other populations except SHZ (Table 4). The least susceptible population to acetamiprid was found in the MNS population, with the LC50 value significantly higher than all other populations (Table 4). The highest difference in toxicity was observed between the LT and MNS populations, with a relative resistance of 25.71 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Susceptibility of field populations of Frankliniella intonsa to acetamiprid.

4. Discussion

As one of the most effective insecticide classes for thrips management, spinosyns have been extensively used for thrips control in China. However, resistance to spinosad and spinetoram in thrips has been widely reported in vegetable crops, especially in western flower thrips (Frankliniella occidentalis) [19,20,27]. In contrast, field populations of F. intonsa on various vegetables across China have been reported to be more susceptible to spinetoram [20,27,28]. In our study, field populations of F. intonsa from Xinjiang cotton fields also showed higher susceptibility to spinetoram, with LC50 values ranging from 0.003 mg L−1 to 0.036 mg L−1, significantly lower than the recommended dose of spinetoram (30~60 mg L−1). These values were lower than those reported in vegetable fields, which ranged from 0.0044 mg L−1 to 0.6476 mg L−1 [20]. The higher susceptibility observed in cotton fields compared to vegetable fields might be due to differences in insecticide selection pressure between cotton and vegetable crops. The short growth cycle and frequent cultivation of vegetable crops may lead to more frequent occurrences and intensive insecticide use, which could contribute to higher resistance levels. The high susceptibility to spinetoram observed in this study aligns with the high control efficacy (79.22% after 7 days) of spinetoram against thrips during the cotton flowering stage in Xinjiang [18]. These results suggest that spinetoram can be used for effective control of F. intonsa in major cotton planting areas of Xinjiang.

Imidacloprid and acetamiprid have been extensively used for controlling sucking pests (e.g., aphids and whiteflies) in cotton [24,25]. Frankliniella intonsa often co-occurs with cotton aphids during flowering and boll stages [29], exposing it to high insecticide selection pressure. Our results showed that the susceptibility of F. intonsa to imidacloprid and acetamiprid varied considerably among different field populations from Xinjiang cotton fields. The Luntai and Shihezi populations were the most susceptible to imidacloprid, while the Korla population was the least susceptible, with LC50 values ranging from 4.361 mg L−1 to 143.930 mg L−1. The LC50 values for the Korla and Manasi populations (143.930 and 41.506 mg L−1, respectively) reported in this study were higher than the recommended rate (35~50 mg L−1). Furthermore, the values also exceeded those in a previous study, in which Korla and Manasi populations had LC50 values of 73.58 and 12.46 mg L−1, respectively [21]. Similarly, Lutai and Shihezi were the most susceptible to acetamiprid, whereas the Manasi population (LC90 value 172.306 mg L−1) was the least susceptible, with its LC90 value higher than the recommended application rate (25~75 mg L−1). The susceptibility of F. intonsa populations in cotton fields to acetamiprid reported here (LC50 values from 1.873 mg L−1 to 48.154 mg L−1) was much lower than that of previously reported F. intonsa populations in alfalfa fields, where the LC50 values ranged from 1.35 mg L−1 to 5.52 mg L−1 [30], but higher than other thrips species, F. occidentalis and Thrips palmi, in vegetable fields in China [31]. These results indicate that F. intonsa has developed resistance to imidacloprid and acetamiprid in some cotton planting areas of Xinjiang (such as Korla and Manasi).

The variation in susceptibility of F. intonsa to the three insecticides among populations showed similar trends. The Lutai and/or Shihezi populations were the most susceptible populations to all three insecticides. The Korla population was the least susceptible to both spinetoram and imidacloprid, and the Manasi population was the least susceptible to acetamiprid. Similar relative resistance trends of imidacloprid and acetamiprid in the same populations (e.g., ALE, YL, SW) indicate that cross-resistance might exist in these two neonicotinoid insecticides. The reduced insecticide susceptibility in the Korla and Manasi populations emphasizes the importance of delaying the development of resistance. Judicious use of insecticides, for instance, rotating insecticides with different modes of action and applying insecticides only when necessary and at correct doses, is an effective measure for resistance management. In addition, complementing chemical control with environmentally friendly insecticides, biological control, and behavioral control would be useful strategies for long-term sustainable management of cotton thrips [32,33,34].

The resistance mechanisms of thrips to spinetoram have been linked to metabolic detoxification and target site mutations in nicotinic acetylcholine receptors [28,35]. Unlike the commonly reported target site mutation in other thrips species, no such mutations have been reported in F. intonsa, which aligns with its high susceptibility in the field [28]. Similarly, thrips’ resistance to neonicotinoid insecticides has also been associated with metabolic detoxification and target site mutations of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors [15,36,37]. However, the resistance mechanisms of F. intonsa to neonicotinoids, such as imidacloprid and acetamiprid, have been rarely studied. Investigating variations in detoxification enzyme activity and the mutation frequency at receptor target sites among different populations could provide insights into the biochemical or genetic basis of susceptibility differences in this species. It is important to note that only three insecticides were tested, and the populations were collected during a single year. Consequently, these results may not fully represent susceptibility variations over time. Ongoing monitoring of the susceptibility of F. intonsa populations to a wide range of insecticides across multiple years is necessary in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L., R.Z. and Y.L.; methodology, X.L. and R.Z.; formal analysis, L.W.; investigation, L.W., W.W. and J.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L.; writing—review and editing, X.L., F.U., C.L., R.Z. and Y.L.; supervision, Y.L. and R.Z.; funding acquisition, R.Z. and C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Major Scientific R&D Program of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (2023A02009).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are fully contained within the figures of the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) of China. Announcement of the National Bureau of Statistics on Cotton Production in 2024; National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) of China: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K.; Guo, Y.Y. The evolution of cotton pest management practices in China. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2005, 50, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Y.D.; Wu, K.M. Managing practical resistance of lepidopteran pests to Bt cotton in China. Insects 2023, 14, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, P.; Liu, J.; Lu, Y. Research progress in the status evolution and integrated control of cotton pests in Xinjiang. Plant Prot. 2018, 44, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Luo, J.Y.; Wang, L.; Zhu, X.Z.; Zhang, K.X.; Li, D.Y.; Niu, L.; Gao, X.K.; Ji, J.C.; Hua, H.X.; et al. Thripidae pest species community identification and population genetic diversity analyses of 2 dominant thrips in cotton fields of China. J. Econ. Entomol. 2024, 117, 1113–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reay-Jones, F.; Greene, J.; Herbert, D.; Jacobson, A.; Kennedy, G.; Reisig, D.; Roberts, P. Within-plant distribution and dynamics of thrips species (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in cotton. J. Econ. Entomol. 2017, 110, 1563–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chappell, T.M.; Ward, R.V.; DePolt, K.T.; Roberts, P.M.; Greene, J.K.; Kennedy, G.G. Cotton thrips infestation predictor: A practical tool for predicting tobacco thrips (Frankliniella fusca) infestation of cotton seedlings in the south-eastern United States. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 4018–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, R.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Yao, J. Occurrence dynamics and spatial distribution pattern of Frankliniella intonsa in cotton fields in Xinjiang. Xinjiang Agric. Sci. 2025, 62, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Tang, L.; Zhang, X.; Xing, Z.; Lei, Z.; Gao, Y. A decade of a thrips invasion in China: Lessons learned. Ecotoxicology 2018, 27, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitz, S.R.; Gao, Y.L.; Kirk, W.D.J.; Hoddle, M.S.; Leiss, K.A.; Funderburk, J.E. Invasion biology, ecology, and management of western flower thrips. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020, 65, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.L.; Lei, Z.R.; Reitz, S.R. Western flower thrips resistance to insecticides: Detection, mechanisms and management strategies. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2012, 68, 1111–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazemi, A.; Khajehali, J.; Van Leeuwen, T. Incidence and characterization of resistance to pyrethroid and organophosphorus insecticides in Thrips tabaci (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in onion fields in Isfahan, Iran. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2016, 129, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizawa, M.; Watanabe, T.; Kumano, A.; Miyatake, T.; Sonoda, S. Cypermethrin resistance and reproductive types in onion thrips, Thrips tabaci (Thysanoptera: Thripidae). J. Pestic. Sci. 2016, 41, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.X.; Narai, Y.; Nakano, A.; Kaneda, T.; Murai, T.; Sonoda, S. Spinosad resistance of melon thrips, Thrips palmi, is conferred by G275E mutation in α6 subunit of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and cytochrome P450 detoxification. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2014, 112, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, W.X.; Kataoka, Y.; Fukada, K. Imidacloprid resistance of melon thrips, Thrips palmi, is conferred by CYP450-mediated detoxification. J. Pestic. Sci. 2015, 40, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.; Herbert, A.; Akin, D.S.; Reed, J. Biology, crop injury, and management of thrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) infesting cotton seedlings in the United States. J. Integr. Pest. Manag. 2011, 2, B1–B9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ambrosio, D.A.; Huseth, A.S.; Kennedy, G.G. Evaluation of alternative mode of action insecticides in managing neonicotinoid-resistant Frankliniella fusca in cotton. Crop Prot. 2018, 113, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.P.; Dou, Z.C.; Ren, H.; Ma, X.L.; Liu, C.Y.; Qasim, M.; Han, X.Q. Study on plant protection unmanned aerial vehicle spraying technology based on the thrips population activity patterns during the cotton flowering period. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1337560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-H.; Gong, Y.-J.; Jin, G.-H.; Li, B.-Y.; Chen, J.-C.; Kang, Z.-J.; Zhu, L.; Gao, Y.-L.; Reitz, S.; Wei, S.-J. Field-evolved resistance to insecticides in the invasive western flower thrips Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande) (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in China. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2016, 72, 1440–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.-F.; Gong, Y.-J.; Cao, L.-J.; Chen, J.-C.; Gao, Y.-L.; Mirab-balou, M.; Chen, M.; Hoffmann, A.; Wei, S.-J. Geographical and interspecific variation in susceptibility of three common thrips species to the insecticide, spinetoram. J. Pest. Sci. 2021, 94, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chang, J.; Xiang, H.; Gui, J.; Ma, D.; Fan, Z.; Lu, W. Resistance monitoring of the field populations of Frankliniella intonsa (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) to six insecticides in four major cotton growing areas of Xinjiang, Northwest China. Acta Entomol. Sin. 2025, 68, 619–625. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, T.C.; Wessels, F.J.; Perry, T.; Price, M.J.; Siebert, M.W.; Mann, D.G.J. Spinosyn resistance and cross-resistance–A 25 year review and analysis. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 210, 106363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomizawa, M.; Casida, J.E. Neonicotinoid insecticide toxicology: Mechanisms of selective action. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2005, 45, 247–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.H.; Li, R.; Chen, Z.B.; Ni, J.P.; Lv, N.N.; Liang, P.Z.; Guo, T.F.; Zhen, C.A.; Liang, P.; Gao, X.W. Comparative susceptibility of Aphis gossypii Glover (Hemiptera: Aphididae) on cotton crops to imidacloprid and a novel insecticide cyproflanilide in China. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 192, 116053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.S.; Cao, Q.; Li, G.Z.; Ma, D.Y. Role of several cytochrome P450s in the resistance and cross-resistance against imidacloprid and acetamiprid of Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) MEAM1 cryptic species in Xinjiang, China. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2020, 163, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yuan, J.; Wang, J.; Hua, D.; Zheng, X.; Tao, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wan, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Susceptibility levels of field populations of Frankliniella occidentalis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) to seven insecticides in China. Crop Prot. 2022, 153, 105886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.L.; Tao, M.; Xue, H.; Jin, H.F.; Liu, K.; Qiu, H.Y.; Yang, S.Y.; Yang, X.; Gui, L.Y.; Zhang, Y.J.; et al. Spinetoram resistance drives interspecific competition between Megalurothrips usitatus and Frankliniella intonsa. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 2129–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, H.P.; Chen, J.C.; Li, F.J.; Kang, J.J.; Li, H.J.; Gao, J.P.; Lu, G.C.; Gong, Y.J.; Wei, S.J. Susceptibility of five thrips pests to spinetoram and the frequency of G275E target-site mutation in a major vegetable production region of China. Crop Prot. 2025, 198, 107398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, B.; Lu, W.; Lu, Y. Niche and interspecific associations of major pests and predatory enemies in cotton fields of Xinjiang, China. Plant Prot. 2025, 51, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.; Wang, C.; Zhu, W.; Han, T. Susceptibility of Frankliniella intonsa in Hohhot Region to nine insecticides. J. Green. Sci. Technol. 2021, 23, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.J.; Chen, J.C.; Cao, L.J.; Ma, Z.Z.; Sun, L.N.; Gao, Y.F.; Ma, L.J.; Wang, J.X.; Ren, Y.J.; Cao, H.Q.; et al. Interspecific and intraspecific variation in susceptibility of two co-occurring pest thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis and Thrips palmi, to nine insecticides. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 3218–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielza, P. Insecticide resistance management strategies against the western flower thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2008, 64, 1131–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouden, S.; Sarmiento, K.F.; Klinkhamer, P.G.; Leiss, K.A. Integrated pest management in western flower thrips: Past, present and future. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2017, 73, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, W.D.J.; de Kogel, W.J.; Koschier, E.H.; Teulon, D.A.J. Semiochemicals for thrips and their use in pest management. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2021, 66, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mocchetti, A.; Dermauw, W.; Van Leeuwen, T. Incidence and molecular mechanisms of insecticide resistance in Frankliniella occidentalis, Thrips tabaci and other economically important thrips species. Entomol. Gen. 2023, 43, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Chen, J.W.; Huang, H.X.; Wen, H.Q.; Yang, J.F.; Geng, J.J.; Wu, S.Y. The amino acid Ser223 acts as a key site for the binding of Thrips palmi α1 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor to neonicotinoid insecticides. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 213, 106484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jouraku, A.; Hirata, K.; Kuwazaki, S.; Nishio, F.; Shimomura, H.; Yokoyama, T.; Kusano, H.; Takagi, M.; Shirotsuka, K.; Shibao, M.; et al. Cythochrome P450-mediated dinotefuran resistance in onion thrips, Thrips tabaci. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 210, 106399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).