Formic Acid-Based Preparation in Varroa destructor Control and Its Effects on Hygienic Behavior of Apis mellifera

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

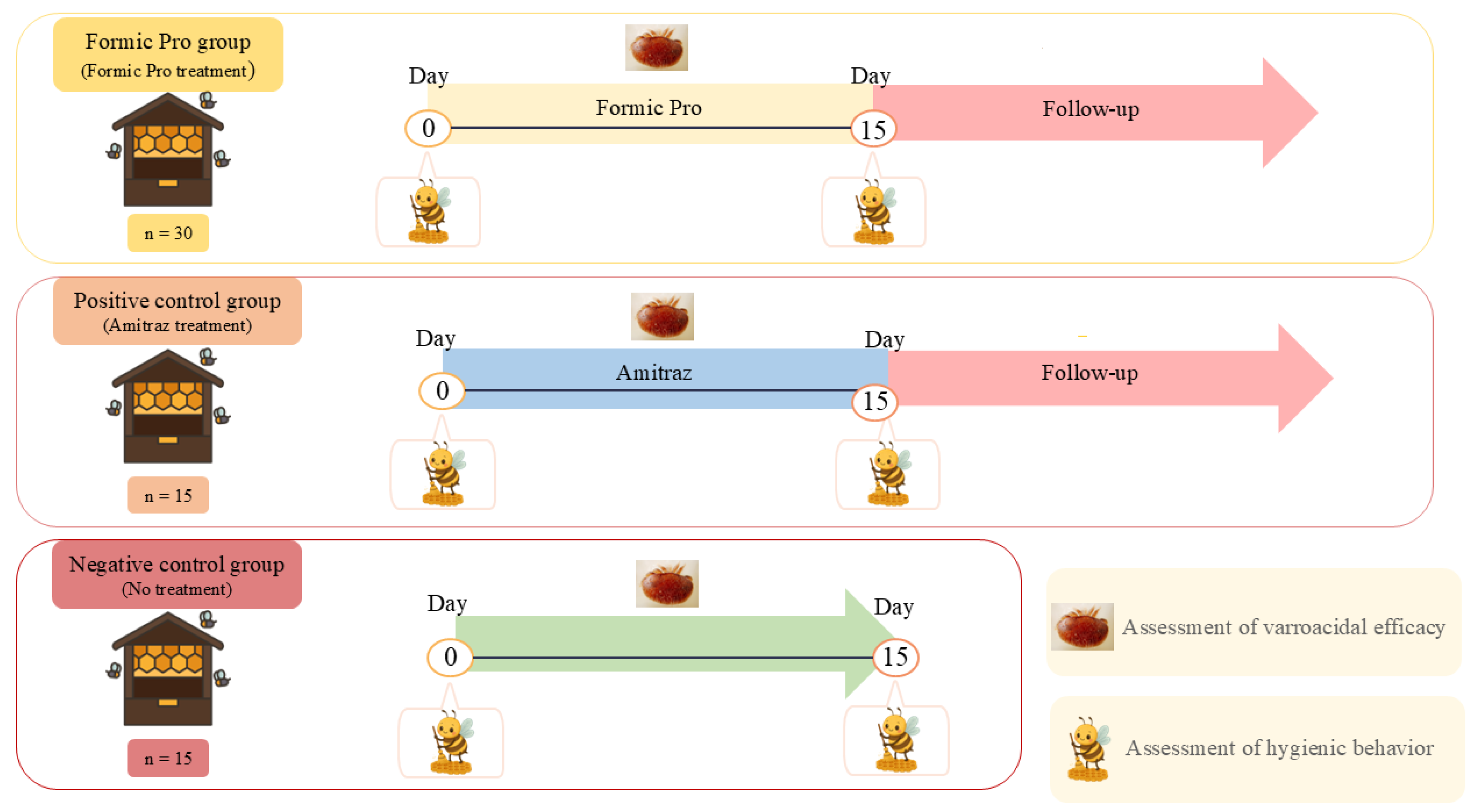

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site, Climatic Conditions, and Honey Bees

2.2. Varroacidal Efficacy Assessment

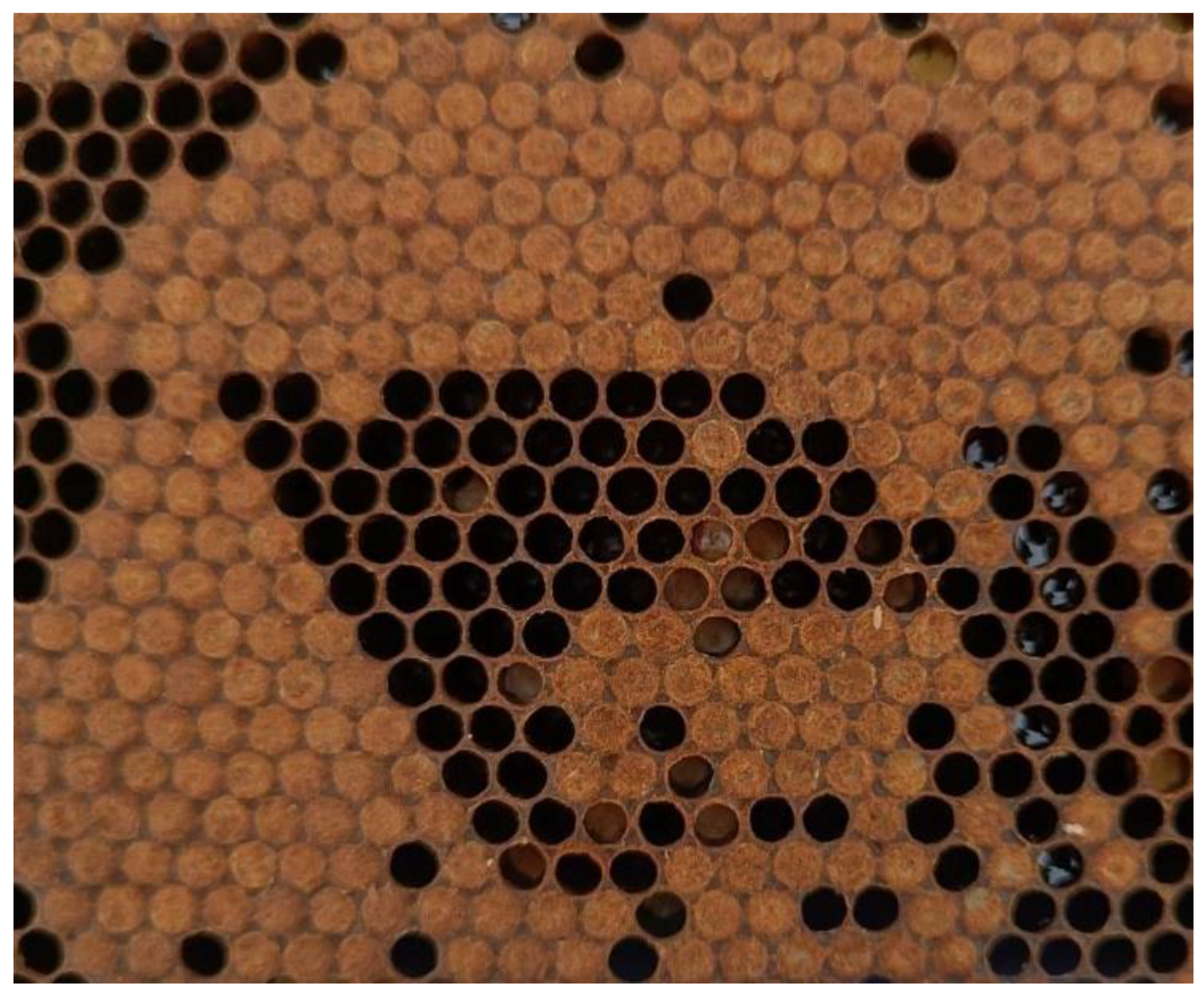

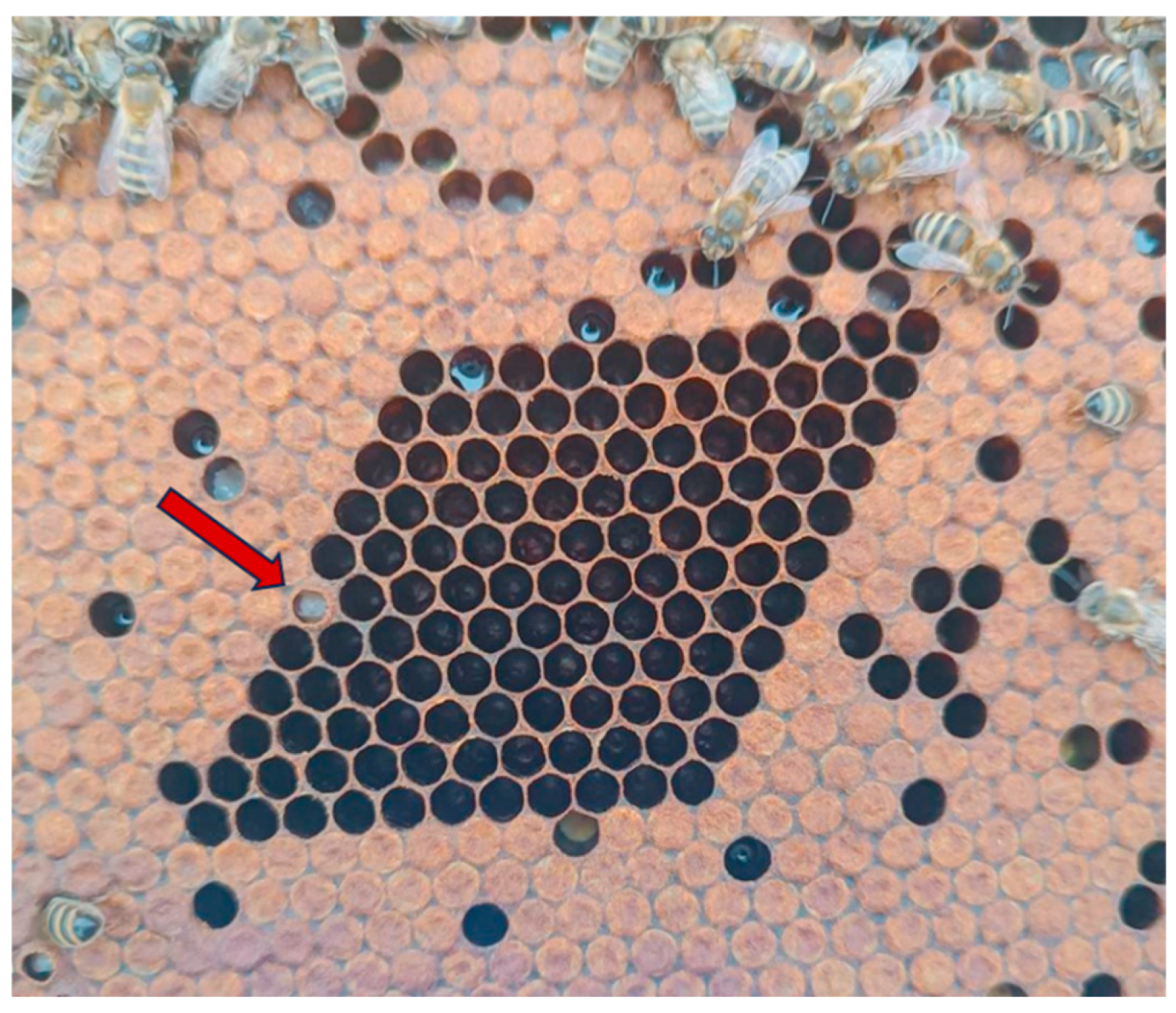

2.3. Hygienic Behavior Evaluation

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

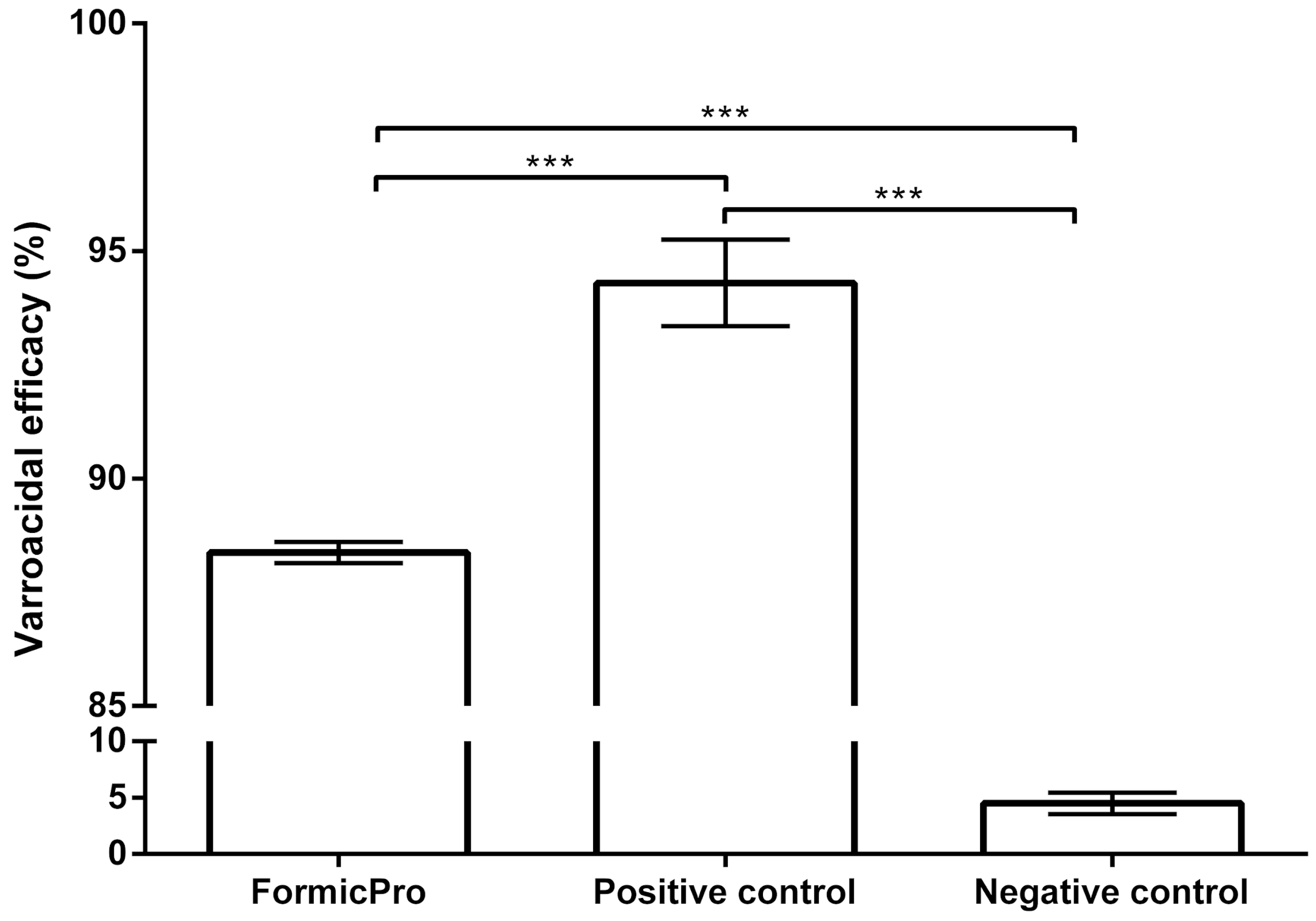

3.1. Varroacidal Efficacy

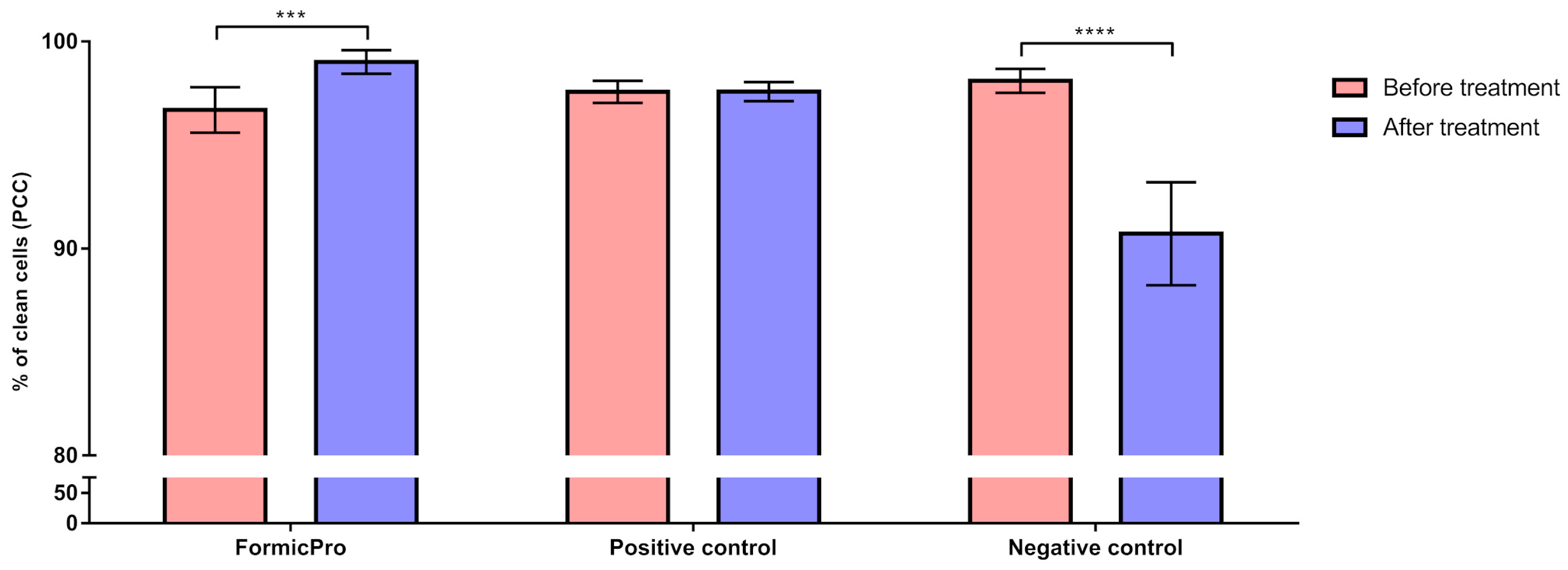

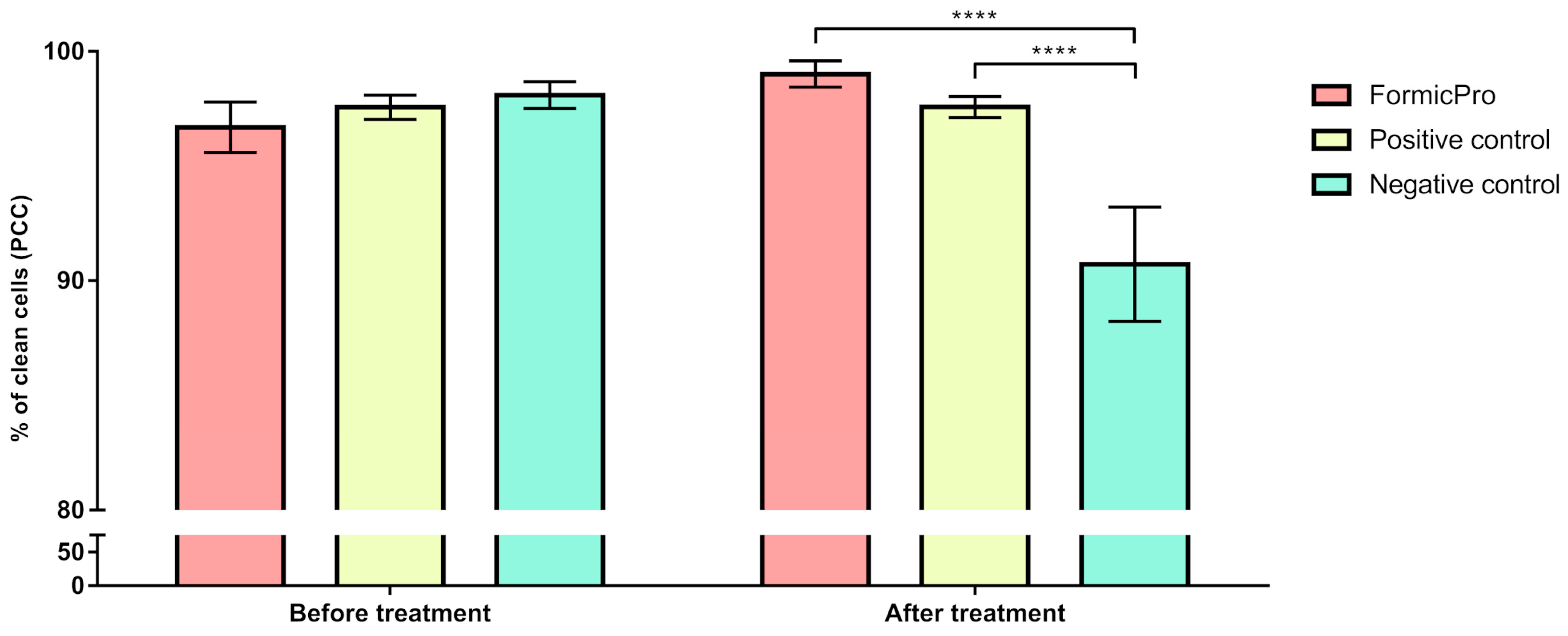

3.2. Hygienic Behavior

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stanimirović, Z.; Glavinić, U.; Ristanić, M.; Aleksić, N.; Jovanović, N.M.; Vejnović, B.; Stevanović, J. Looking for the causes of and solutions to the issue of honey bee colony losses. Acta Vet. 2019, 69, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosch, Y.; Mülling, C.; Emmerich, I.U. Assessment of resistance of Varroa destructor to formic and lactic acid treatment-A systematic review. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirkovic, D.; Stevanovic, J.; Glavinic, U.; Aleksic, N.; Djuric, S.; Aleksic, J.; Stanimirovic, Z. Honey bee viruses in Serbian colonies of different strength. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsey, S.D.; Ochoa, R.; Bauchan, G.; Gulbronson, C.; Mowery, J.D.; Cohen, A.; van Engelsdorp, D. Varroa destructor feeds primarily on honey bee fat body tissue and not hemolymph. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 1792–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxton, R.J.; Schäfer, M.O.; Nazzi, F.; Zanni, V.; Annoscia, D.; Marroni, F.; Bigot, D.; Laws-Quinn, E.R.; Panziera, D.; Jenkins, C.; et al. Epidemiology of a major honey bee pathogen, deformed wing virus: Potential worldwide replacement of genotype A by genotype B. Int. J. Parasitol-Par. 2022, 18, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, N.; Techer, M.A.; Adjlane, N.; Al-Hissnawi, M.S.; Antúnez, K.; Beaurepaire, A.; Christmon, K.; Delatte, H.; Dukku, U.H.; Eliash, N.; et al. Evolutionarily diverse origins of deformed wing viruses in western honey bees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2301258120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higes, M.; Martín-Hernández, R.; Hernández-Rodríguez, C.S.; González-Cabrera, J. Assessing the resistance to acaricides in Varroa destructor from several Spanish locations. Parasitol. Res. 2020, 119, 3595–3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitton, G.A.; Meroi Arcerito, F.; Cooley, H.; Fernandez de Landa, G.; Eguaras, M.J.; Ruffinengo, S.R.; Maggi, M.D. More than sixty years living with Varroa destructor: A review of acaricide resistance. Int. J. Pest. Manag. 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, R.M.; Currie, R.W. The effects of temperature and dose of formic acid on treatment efficacy against Varroa destructor (Acari: Varroidae), a parasite of Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2003, 29, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genath, A.; Sharbati, S.; Buer, B.; Nauen, R.; Einspanier, R. Comparative transcriptomics indicates endogenous differences in detoxification capacity after formic acid treatment between honey bees and varroa mites. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietropaoli, M.; Formato, G. Formic acid combined with oxalic acid to boost the acaricide efficacy against Varroa destructor in Apis mellifera. J. Apic. Res. 2022, 61, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietropaoli, M.; Formato, G. Liquid formic acid 60% to control varroa mites (Varroa destructor) in honey bee colonies (Apis mellifera): Protocol evaluation. J. Apic. Res. 2018, 57, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Căuia, E.; Căuia, D. Improving the Varroa (Varroa destructor) control strategy by brood treatment with formic acid-a pilot study on spring applications. Insects 2022, 13, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spivak, M.; Danka, R.G. Perspectives on hygienic behavior in Apis mellifera and other social insects. Apidologie 2021, 52, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchler, R.; Andonov, S.; Bernstein, R.; Bienefeld, K.; Costa, C.; Du, M.; Gabel, M.; Given, K.; Hatjina, F.; Harpur, B.A.; et al. Standard methods for rearing and selection of Apis mellifera queens 2.0. J. Apic. Res. 2025, 64, 555–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Iorio, M.G.; Biffani, S.; Pagnacco, G.; Stella, A.; Cozzi, M.C.; Maggi, L.A.; Minozzi, G. Results of four generations of selection for Varroa sensitive hygienic behavior in honey bees. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 24, 1959–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpur, B.A.; Guarna, M.M.; Huxter, E.; Higo, H.; Moon, K.M.; Hoover, S.E.; Ibrahim, A.; Melathopoulos, A.P.; Desai, S.; Currie, R.W.; et al. Integrative genomics reveals the genetics and evolution of the honey bee’s social immune system. Genome Biol. Evol. 2019, 11, 937–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu-Smart, J.; Spivak, M. Sub-lethal effects of dietary neonicotinoid insecticide exposure on honey bee queen fecundity and colony development. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morfin, N.; Goodwin, P.H.; Correa-Benitez, A.; Guzman-Novoa, E. Sublethal exposure to clothianidin during the larval stage causes long-term impairment of hygienic and foraging behaviours of honey bees. Apidologie 2019, 50, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gashout, H.A.; Guzman-Novoa, E.; Goodwin, P.H. Synthetic and natural acaricides impair hygienic and foraging behaviors of honey bees. Apidologie 2020, 51, 1155–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colin, T.; Lim, M.Y.; Quarrell, S.R.; Allen, G.R.; Barron, A.B. Effects of thymol on European honey bee hygienic behaviour. Apidologie 2019, 50, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanimirovic, Z.; Glavinic, U.; Ristanic, M.; Jelisic, S.; Vejnovic, B.; Niketic, M.; Stevanovic, J. Diet supplementation helps honey bee colonies in combat infections by enhancing their hygienic behaviour. Acta Vet. 2022, 72, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, N.M.; Glavinić, U.; Stevanović, J.; Ristanić, M.; Vejnović, B.; Dolašević, S.; Stanimirović, Z. A field trial to demonstrate the potential of a vitamin B diet supplement in reducing oxidative stress and improving hygienic and grooming behaviors in honey bees. Insects 2025, 16, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morfin, N.; Goodwin, P.H.; Guzman-Novoa, E. Varroa destructor and its impacts on honey bee biology. Front. Bee Sci. 2023, 1, 1272937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tihelka, E. Effects of synthetic and organic acaricides on honey bee health: A review. Slov. Vet. Res. 2018, 55, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaplane, K.S.; Van Der Steen, J.; Guzman-Novoa, E. Standard methods for estimating strength parameters of Apis mellifera colonies. J. Apic. Res. 2013, 52, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, N.M.; Glavinic, U.; Delic, B.; Vejnovic, B.; Aleksic, N.; Mladjan, V.; Stanimirovic, Z. Plant-based supplement containing B-complex vitamins can improve bee health and increase colony performance. Prev. Vet. Med. 2021, 190, 105322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainat, B.; Dietemann, V.; Imdorf, A.; Charrière, J.D. A scientific note on the ‘Liebefeld Method’ to estimate honey bee colony strength: Its history, use, and translation. Apidologie 2020, 51, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanimirovic, Z.; Glavinic, U.; Lakic, N.; Radovic, D.; Ristanic, M.; Taric, E.; Stevanovic, J. Efficacy of plant-derived formulation Argus Ras in Varroa destructor control. Acta Vet. 2017, 67, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMA-European Medicines Agency. EMA/CVMP/EWP/459883/2008, Committee for Medicinal Products for Veterinary Use (CVMP), Guideline on Veterinary Medicinal Products Controlling Varroa destructor Parasitosis in Bees. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-veterinary-medicinal-products-controlling-varroa-destructor-parasitosis-bees-revision-1_en.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Gregorc, A.; Planinc, I. Use of thymol formulations, amitraz, and oxalic acid for the control of the varroa mite in honey bee (Apis mellifera carnica) colonies. J. Apic. Sci. 2012, 56, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semkiw, P.; Skubida, P.; Pohorecka, K. The amitraz strips efficacy in control of Varroa destructor after many years of application of amitraz in apiaries. J. Apic. Sci. 2013, 57, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietropaoli, M.; Formato, G. Acaricide efficacy and honey bee toxicity of three new formic acid-based products to control Varroa destructor. J. Apic. Res. 2019, 58, 824–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefuss, J.; Taber, S.; Vanpoucke, J.; Rey, F. A practical method to test for disease resistance in honey bees. Am. Bee J. 1996, 136, 31–32. [Google Scholar]

- Stanimirovic, Z.; Pejovic, D.; Stevanovic, J.; Vucinic, M.; Mirilovic, M. Investigations of hygienic behaviour and disease resistance in organic beekeeping of two honeybee ecogeographic varieties from Serbia. Acta Vet. 2002, 52, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanimirovic, Z.; Glavinic, U.; Jovanovic, N.M.; Ristanic, M.; Milojković-Opsenica, D.; Mutic, J.; Stevanovic, J. Preliminary trials on effects of lithium salts on Varroa destructor, honey and wax matrices. J. Apic. Res. 2022, 61, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabbri, R.; Danielli, S.; Galuppi, R. Treatment based on formic acid for Varroa destructor control with two different evaporators: Efficacy and tolerability comparison. J. Apic. Res. 2023, 62, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriksma, H.P.; Cornelissen, B.; Panziera, D. Liquid and solid matrix formic acid treatment comparison against Varroa mites in honey bee colonies. J. Apic. Res. 2024, 63, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smodiš Škerl, M.I.; Rivera-Gomis, J.; Tlak Gajger, I.; Bubnič, J.; Talakić, G.; Formato, G.; Baggio, A.; Mutinelli, F.; Tollenaers, W.; Laget, D.; et al. Efficacy and toxicity of VarroMed® used for controlling Varroa destructor infestation in different seasons and geographical areas. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Formic Acid Livestock. 2011. Available online: https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/Formic%20Acid%20TR.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Kim, H.; You, E.; Cha, J.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, Y.H. Toxicity of consecutive treatments combining synthetic and organic miticides to nurse bees of Apis mellifera. Insects 2025, 16, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz, P.; Aumeier, P.; Ziegelmann, B. Biology and control of Varroa destructor. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010, 103, S96–S119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, P.J. Integrated resistance management for acaricide use on Varroa destructor. Front. Bee Sci. 2023, 1, 1297326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albero, B.; Miguel, E.; García-Valcárcel, A.I. Acaricide residues in beeswax. Implications in honey, brood and honeybee. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karazafiris, E.; Kanelis, D.; Tananaki, C.; Goras, G.; Menkissoglu-Spiroudi, U.; Rodopoulou, M.A.; Liolios, V.; Argena, N.; Thrasyvoulou, A. Assessment of synthetic acaricide residues in royal jelly. J. Apic. Res. 2024, 63, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genath, A.; Petruschke, H.; von Bergen, M.; Einspanier, R. Influence of formic acid treatment on the proteome of the ectoparasite Varroa destructor. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Steen, J.; Vejsnæs, F. Varroa control: A brief overview of available methods. Bee World 2021, 98, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman-Novoa, E.; Corona, M.; Alburaki, M.; Reynaldi, F.J.; Invernizzi, C.; Fernández de Landa, G.; Maggi, M. Honey bee populations surviving Varroa destructor parasitism in Latin America and their mechanisms of resistance. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 12, 1434490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Sharma, R.; Chaudhary, A.; Singh, R. Factors affecting immune responses in honey bees: An insight. J. Apic. Sci. 2021, 65, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, Y.; Tomasco, I.H.; Antúnez, K.; Castelli, L.; Branchiccela, B.; Santos, E.; Invernizzi, C. Unraveling honey bee–Varroa destructor interaction: Multiple factors involved in differential resistance between two Uruguayan populations. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li-Byarlay, H.; Young, K.; Cleare, X.; Cao, D.; Luo, S. Biting behavior against Varroa mites in honey bees is associated with changes in mandibles, with tracking by a new mobile application for mite damage identification. Apidologie 2025, 56, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanimirović, Z.; Stevanović, J.; Mirilović, M.; Stojić, V. Heritability of hygienic behavior in grey honey bees (Apis mellifera carnica). Acta Vet. 2008, 58, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Page, P.; Li, L.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, F.; Neumann, P.; Zheng, H.; Dietemann, V. Go east for better honey bee health: Apis cerana is faster at hygienic behavior than A. mellifera. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erez, T.; Bonda, E.; Kahanov, P.; Rueppell, O.; Wagoner, K.; Chejanovsky, N.; Soroker, V. Multiple benefits of breeding honey bees for hygienic behavior. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2022, 193, 107788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, M.E.; Allam, S.F. Effect of some aromatic oils and chemical acaricides on the mechanical defense behavior of honey bees against Varroa invasion and relationship with sensation responses. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 2007, 3, 653–661. [Google Scholar]

- Valizadeh, S.; Naseri, M.; Babaei, S.; Hosseini, S.M.H.; Imani, A. Development of bioactive composite films from chitosan and carboxymethyl cellulose using glutaraldehyde, cinnamon essential oil and oleic acid. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 134, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanovic, J.; Stanimirovic, Z.; Lakic, N.; Aleksic, N.; Simeunovic, P.; Kulisic, Z. Safety assessment of sugar dusting treatments by analysis of hygienic behaviour in honey bee colonies. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2011, 63, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Groups | n | (%) | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formic Pro | 30 | 88.37 | 0.23 | 88.05 | 88.76 |

| Positive control | 15 | 94.30 | 0.95 | 93.06 | 95.36 |

| Negative control | 15 | 4.50 | 0.95 | 3.64 | 6.94 |

| Groups | Time-Points of Hygienic Behavior Evaluation | n | PCC | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formic Pro | Before treatment | 30 | 96.69 | 1.10 | 95.32 | 98.70 |

| After treatment | 30 | 99.01 | 0.57 | 97.52 | 99.45 | |

| Positive control | Before treatment | 15 | 97.57 | 0.53 | 96.83 | 98.21 |

| After treatment | 15 | 97.58 | 0.46 | 97.04 | 98.10 | |

| Negative control | Before treatment | 15 | 98.10 | 0.58 | 97.52 | 99.03 |

| After treatment | 15 | 90.72 | 2.49 | 86.36 | 92.70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ristanić, M.; Glavinić, U.; Stevanović, J.; Cvetković, T.; Mijatović, A.; Vejnović, B.; Stanimirović, Z. Formic Acid-Based Preparation in Varroa destructor Control and Its Effects on Hygienic Behavior of Apis mellifera. Insects 2025, 16, 1236. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121236

Ristanić M, Glavinić U, Stevanović J, Cvetković T, Mijatović A, Vejnović B, Stanimirović Z. Formic Acid-Based Preparation in Varroa destructor Control and Its Effects on Hygienic Behavior of Apis mellifera. Insects. 2025; 16(12):1236. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121236

Chicago/Turabian StyleRistanić, Marko, Uroš Glavinić, Jevrosima Stevanović, Tamara Cvetković, Aleksa Mijatović, Branislav Vejnović, and Zoran Stanimirović. 2025. "Formic Acid-Based Preparation in Varroa destructor Control and Its Effects on Hygienic Behavior of Apis mellifera" Insects 16, no. 12: 1236. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121236

APA StyleRistanić, M., Glavinić, U., Stevanović, J., Cvetković, T., Mijatović, A., Vejnović, B., & Stanimirović, Z. (2025). Formic Acid-Based Preparation in Varroa destructor Control and Its Effects on Hygienic Behavior of Apis mellifera. Insects, 16(12), 1236. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121236