Abstract

The lubrication properties of gallium-matrix liquid metal (GLM) are intimately connected to the tribofilms formed through frictional processes. Physico-chemical properties of the tribofilms depend on the interfacial interactions between GLM and the surfaces of frictional pairs. Therefore, it is significant to reveal the process of interfacial interactions. In this study, considering that Ga and In atoms are the main components of GLM lubricant, the adsorption processes of Ga and In atoms on Fe (111) and Cu (111) surfaces are, respectively, investigated at the atomic level by the density functional theory (DFT) method to have an insight into the lubrication behaviors of GLM for bearing steel and albronze metals. It is found that the adsorptions of Ga atom on both Fe (111) and Cu (111) surfaces are stronger than that of In atom, and thus forming Fe-Ga bond and Cu-Ga bond. Furthermore, interfacial interactional experiments and tribological experiments are conducted to verify the results of first-principles calculations. Tribological experiments demonstrate that with FeGa3 film on the bearing steel surface, the friction coefficient and wear rate can be reduced by 30% and 82%, while with CuGa2 film on the albronze surface, the friction coefficient and wear rate can be reduced by 27% and 94%.

1. Introduction

Gallium-matrix liquid metal with a melting point lower than 30 °C is an amorphous and flowable liquid metal alloy at room temperature. One important and commonly used gallium-matrix liquid metal is EGaIn (GLM). EGaIn is a eutectic binary metal alloy composed of 76 wt% gallium and 24 wt% indium. And in comparison with high-temperature MoS2 lubricant grease whose suitable working temperature is below 450 °C, GLM shows splendid thermal conductivity (16–39 W/M·K, two orders of magnitude higher than traditional lubricants) and thermal stability (decomposition temperature is above 2000 °C) because of the metallicity and fluidity, which makes GLM suitable for super-high-temperature and current-carrying working environments [1,2].

Owing to the unique physical and chemical characteristics of GLM, the investigation into GLM as a special lubricant under harsh operating conditions started early in the last century. Back in the 1960s, the applicability of GLM as a high-temperature conductive lubricant in magnetic hydrodynamic bearing was explored by Hughes [3]. NASA reported that gallium-matrix liquid metals exhibited good tribological properties when used as lubrication fluid for a high-current-density brush composed of stainless steel and nickel. And the application of liquid metals as lubricants for sliding bearing under temperatures ranging from 30 to 300 °C was also carried out. Early studies had verified the feasibility of GLMs as lubricants to a certain extent [4,5,6,7,8,9]. In recent years, Tian et al. used a four-ball friction and wear tester to explore the lubrication performance of GLM under extremely high load conditions [10]. They found that GLM was capable of preventing the seizure of friction pairs under extremely high load conditions due to its excellent thermal conductivity, which made GLM a potential new type of extreme pressure lubricant. Since then, more and more studies have been conducted to explore the lubrication mechanisms of liquid metals. The lubrication behaviors of liquid metals under different working conditions [11] and the nanoscale lubricity of GLM have also been investigated [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Several factors, including the type of gallium-matrix liquid metals, the material of friction pairs, and the working condition, have significant impacts on the lubrication effect of gallium-matrix liquid metals [20,21]. As such, the same type of gallium-matrix liquid metals may have different lubrication performance in different frictional systems due to the variations in tribofilms formed by the reactions of GLM with frictional pairs.

These studies indicated that the splendid lubrication performance of GLM intimately depends on the physico-chemical properties of tribofilms formed by the reactions of GLM with frictional pairs. However, the interfacial forming processes of the tribofilms are hard to be tested and observed. The development of first-principles calculation and density functional theory (DFT) provides an effective approach to discover the interfacial interactions between GLM and frictional pairs at the atomic level [22,23,24,25,26]. Taylor et al. [27,28] utilized DFT to model and simulate the deposition and dissolution scenarios of metals in water. The adsorption and migration processes of carbon atoms on the Cu (111) surface were carefully studied through adopting first-principles calculations within DFT by Zhan et al. [29]. Therefore, this study investigated the adsorption processes of Ga and In atoms on Fe (111) and Cu (111) surfaces using the DFT method to provide an insight into the lubrication behaviors of GLM for bearing steel and albronze tribo-pairs. Furthermore, tribological experiments were conducted to verify the results of first-principles calculations and reveal the lubrication mechanisms of GLM.

2. Experimental Methods

2.1. Calculation Details

The first-principles calculations were conducted through using CASTEP code under the framework of the density functional theory. The ultrasoft pseudopotentials were utilized to explain the electron–ion interactions. The Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof function, as conducted by the gradient approximation method (GGA), was performed to describe the exchange–correlation interactions. The Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno method was further employed to handle every geometry optimization.

With regard to the adsorption of Ga atom on the Fe surface, for the sake of improving the computational precision and speed, the energy of the cutoff was set as 290 eV for the plane wave basis to expand the electronic wave functions on the convergence test. When the total energy difference was below 2 × 10−6 eV/atom, the system was considered to have reached convergence. The convergence critical value of maximum Hellmann–Feynman force was specified as 0.05 eV/Å. The value of maximum ionic displacement was specified as 0.002 Å. The Brillouin zone integrations were carried out on a special k-points mesh, 3 × 3 × 3 for the body-centered cubic structure bulk, generated by the Monkhorst–Pack scheme. With the above parameters, for bulk Fe with a body-centered cubic structure, the lattice constant was optimized to be 2.831 Å, which was consistent with the experimental data and other DFT calculations [30].

With regard to the adsorption of Ga atom on the Cu surface, the cutoff energy was set as 280 eV for the plane-wave basis. The convergence critical value of maximum Hellmann–Feynman force was specified as 0.05 eV/Å. The value of maximum ionic displacement was specified as 0.002 Å. The Brillouin zone integrations were carried out on a special k-points mesh, 5 × 5 × 5 for the face-centered cubic structure bulk. With the above parameters, the lattice constant of bulk Cu with a face-centered cubic structure was optimized to be 3.614 Å, which aligns well with the previously reported experimental value and theoretical value of 3.615 Å [31].

2.2. Model Description

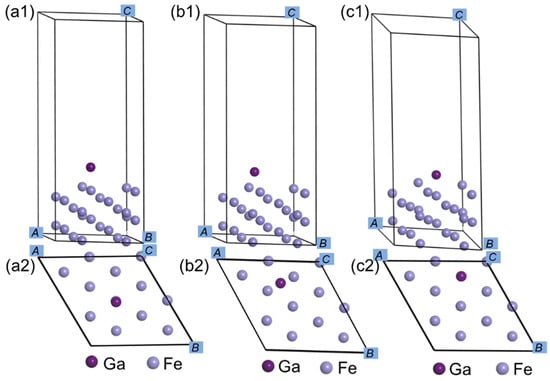

For simulating AISI52100 steel interface, bulk Fe was adopted to replace the bearing steel. The lattice parameter of bulk Fe was computed to be 2.831 Å. A six-layer 2 × 2 periodic supercell slab was established to model the surface of Fe (111), which was cut from the refined bulk Fe structure. The Fe (111) slab was isolated by the vacuum slab, of which the thickness is 15 Å along the c-direction (z-direction) for the sake of avoiding periodic interactions, which is demonstrated in Figure 1. Moreover, for the sake of simulating the bulk environment, atoms on the below three layers of the Fe (111) surface were constrained at original atomical locations, and the remained atoms on the upper three layers were permitted to be relaxed. The models of Ga atom adsorption surfaces were established by adding Ga atom on the optimized clean surface at three high-symmetric and different sites, including the top, bridge, and hollow site, to obtain the lowest energy configuration.

Figure 1.

Ga atom on clean Fe (111) surface. (a1) Side view of top site, (a2) top view of top site, (b1) side view of bridge site, (b2) top view of bridge site, (c1) side view of hollow site, (c2) top view of hollow site.

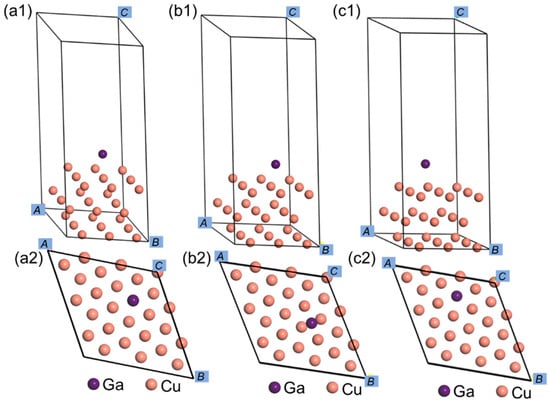

For C95200 albronze interface, bulk Cu was adopted to replace the albronze alloy. The lattice parameter of bulk Cu was calculated to be 3.614 Å. A three-layer 3 × 3 periodic and symmetric slab was adopted to simulate the Cu (111) surface, which was cut from the refined bulk Cu structure. To avoid any periodic interactions, the Cu (111) slab was isolated by vacuum layers whose thickness is 15 Å along the c-direction, as shown in Figure 2. The atoms on the two below layers of the Cu (111) surface were constrained at original atomical locations, and the atoms that remained on the upper layer were allowed to be relaxed. With regard to the clean Cu (111) surface, three common adsorption sites exist for Ga atoms, which are the top site, bridge site, and hollow site, respectively.

Figure 2.

Ga atom on the clean Cu (111) surface. (a1) Side view of top site, (a2) top view of top site, (b1) side view of bridge site, (b2) top view of bridge site, (c1) side view of hollow site, (c2) top view of hollow site.

2.3. Interfacial Interactions and Tribological Experiments

The GLM used in this study is Ga76In24, which can be easily obtained and holds a boiling point above 2000 °C and melting point of 15.5 °C. Ga76In24 is obtained by the following procedures. Original bulk Ga and In metals adopted in this work were provided by Kunming Jusheng metal materials Co., Ltd. (Kunming, China). Ga and In materials with a mass ratio of 76:24 were put in a crucible. And then the crucible filled with Ga and In was heated to 160 °C and lasted for about 15 min under the vacuum atmosphere. After that, the mixtures of Ga and In were cooled for 5 min. Next, the mixtures were ultra-sonicated in a water bath for about 15 min at room temperature, thus obtaining a thoroughly mixed Ga and In. A solution of 1 mol/L NaOH was finally used to dispose of the oxidized residues generated during the fabrication processes.

Interaction layers on AISI52100 bearing steel and C95200 albronze substrates were prepared by making GLM directly contact with the surface of substrates in 1 wt% acetic acid solution for 30 min under room temperature. Then, the redundant GLMs were removed by cotton buds. For the sake of further identifying the morphologies and phase compositions of the interaction layers, tungsten filament scanning electron microscope (SEM; JSM-7610F, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) and X-ray diffractometer (XRD; D8 advance, Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) tests with a wavelength (λ) of 0.15418 nm were carried out.

Albronze and bearing steel disks were cut from albronze and bearing steel bars with diameters of 30 mm and thicknesses of 5 mm. The chemical compositions of albronze samples and bearing steel disks are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. For AISI52100 bearing steel, C element holds a modifying effect on the local surface chemistry and defect electronic states of bearing steel. Si and Mn elements exist in the form of solid solution to enhance the strength of the matrix and demonstrate a slight influence on the surface electronic state. Since the perturbation of the C element on the global electronic structure is second-order, and this study primarily focuses on the electronic states and band structure near the Fermi surface of the iron substrate, the simplified pure Fe model is obtained. For C95200 aluminum bronze, Al element shows little influence under anaerobic environment and Fe element shows almost no influence on electron density due to the relatively lower concentration. A simplified model Fe/Cu model is an effective tool for explaining the different adsorption behaviors of Ga atom and In atom. The surfaces of albronze and bearing steel disks were sanded with abrasive papers of #600, #800, #1000, and #1200 in sequence. The samples were then polished by a piece of lint with polishing agent until the surfaces of the disks reached a mirror effect. The surface roughness of albronze and bearing steel disks was tested with a contact surface roughness meter (TR200, TIME GROUP Inc., Beijing, China), which was Ra 0.020 + 0.002 μm.

Table 1.

The component details of C95200 albronze samples.

Table 2.

The component details of AISI52100 bearing steel disks.

The tribological performance of GLM interaction layers was tested by a ball-on-disk tribometer (UMT-2, CETR Corporation Ltd., Campbell, CA, USA) in reciprocation mode under the applied load of 15 N and a sliding speed of 24 mm/s. The disks were AISI52100 bearing steel, bearing steel with an interaction layer, C95200 albronze, and albronze with an interaction layer. When the applied load was kept constant at 15 N for AISI52100 bearing steel disk in the tribology test, the corresponding average Hertzian contact pressure was 1428 MPa, which is near the real Hertzian contact pressure of rolling bearing in the engineering applications. Experiments were performed at ambient humidity and room temperature. To assure their repeatability, each frictional test was repeated three times. The wear rate (k) for all experiments was determined based on the wear volume of the disk in accordance with the below Equations (1)–(3),

where h is the height of spherical cap/mm; R is the original radius of the ball/mm; r is corresponding wear scar radius/mm; V is wear volume/mm3; F is the applied load/N; and S is the total sliding distance/m. Three radii of each wear scar were recorded for all experiments, and the average values were calculated.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Reaction of GLM on Fe (111) Surface

Tribofilm formation is supported by the strong adsorption of molecules or atoms on the frictional surface. With GLM as lubricants for AISI52100 bearing steel frictional pair, there are Ga atoms and In atoms which can undergo an adsorption reaction with the substrate. Adsorption strength is expressed by adsorption energy (Eads), which can be obtained by calculating the difference between the energy of the adsorption system and the sum of the energy, as shown in the following Equation (4),

where Eslab+ada is the total energy of the adsorption model system after geometry optimization/eV; Eslab represents the total energy of isolated Fe (111) layer or Cu (111) layer/eV; and Eada is the energy of separated Ga atom or In atom/eV.

Eads = Eslab+ada − Eslab − Eada

For the sake of confirming the most stable site of adsorption, the adsorption energies of the Ga atom adsorbed on the Fe (111) surface are calculated. The adsorption energies and other related energies for Ga atom adsorbed on the clean Fe (111) surface are calculated and listed in Table 3. It is clear that the adsorption processes of Ga atom adsorbed at different sites of the clean Fe (111) surface can be regarded as the strong chemical adsorption because all values of adsorption energy are calculated to be negative. And among the three adsorption sites, the adsorption energy of Ga atom on the bridge adsorption site is the smallest, which is −5.7 eV. Therefore, the bridge site is the most stable adsorption site for this system. Furthermore, the adsorption energies of the In atom on the Fe (111) surface at the top site, bridge site, and hollow site are calculated, which are −1.13 eV, −4.04 eV, and −3.07 eV, respectively. It can be deduced that the adsorption behavior of Ga atom on Fe (111) surface is stronger than the adsorption behavior of In atom.

Table 3.

The adsorption energies of Ga atom on clean Fe (111) surface for different adsorption sites.

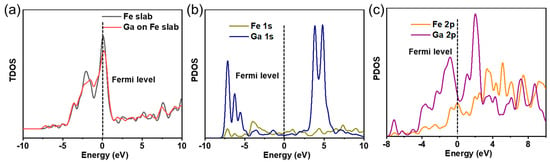

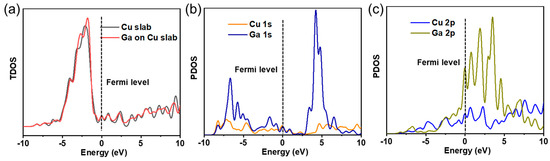

The total density of state (TDOS) and partial density of state (PDOS) are further performed to gain a deep understanding of the interaction between Ga atom and Fe surface, and the results are demonstrated in Figure 3. From Figure 3a, where the TDOS comparison of clean Fe (111) slab with the Ga adsorption system is displayed, it can be clearly seen that the TDOS curve shape of Fe (111) slab around the Fermi level is significantly changed by the adsorption of Ga atom. The interaction of Ga atom with the Fe (111) slab gives rise to the generation of two novel peaks at −2.51 eV and −1.81 eV. The redistribution of electrons can be mainly ascribed to the interactions between Ga atom and the nearby atoms on Fe (111) slab. Figure 3b gives the PDOS curves of Fe1s and Ga1s for Ga atom adsorbed on clean Fe (111) slab. It is displayed that there is a clear overlap peak ranging from −8 eV to −5 eV between Fe1s and Ga1s orbitals. Figure 3c gives the PDOS curves of Fe2p and Ga2p for Ga atom adsorbed on clean Fe (111) slab, which shows that there are several obvious overlap peaks between Fe2p and Ga2p orbitals. The above results manifest that the adsorption of Ga atom is able to influence the electronic structure of the Fe atoms, meaning the formation of Fe-Ga bond.

Figure 3.

(a) TDOS of Fe (111) surface and the adsorption system. (b) PDOS of Fe1s and Ga1s. (c) PDOS of Fe2p and Ga2p.

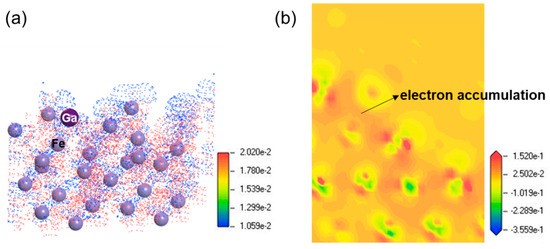

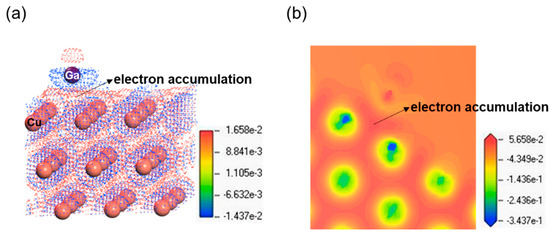

The charge density difference in Ga atom adsorbed on clean Fe (111) surface is calculated and analyzed as shown in Figure 4. A three-dimensional dot map and 2D cross-sectional map are given in Figure 4a and Figure 4b, respectively. We can observe in Figure 4a that the blue and red areas for the charge density difference signify the regions of electron depletion and accumulation, respectively. This indicates that some electrons of Fe atoms have transferred to Ga atom, thus producing Fe-Ga bond. The phenomenon of charge transfer between Ga atom and adjacent Fe atoms is consistent with the analyses of density of states.

Figure 4.

Charge density difference around the adsorption interface of Ga atom adsorbed on clean Fe (111) surface. (a) Three-dimensional dot view; (b) cross-sectional view of contour map.

3.2. Reaction of GLM on Cu (111) Surface

The adsorption energies and related energies for Ga atom adsorption on the clean Cu (111) surface are calculated and listed in Table 4. It is clear that among the three adsorption sites, the adsorption energy of Ga atom on the hollow adsorption site is the smallest. Therefore, the hollow site is the most stable adsorption site. The Eads of In atom on the top site, bridge site, and hollow site of clean Cu (111) surface are further calculated, which are −0.75 eV, −1.08 eV, and −1.62 eV, respectively.

Table 4.

The adsorption energies of Ga atom on clean Cu (111) surface for different adsorption sites.

It can be deduced from the TDOS curves in Figure 5a that the interaction of Ga atom with the Cu (111) slab gives rise to the generation of two novel peaks at 3.78 eV and 7.5 eV. Moreover, it can be discovered that compared with clean Cu (111) slab, three peaks located from −4 eV to −1 eV for Ga atom adsorption on the clean surface of Cu (111) mildly shift toward higher energy locations. This phenomenon indicates that the structure of Ga atom adsorption on Cu (111) slab is more stable than the structure of clean Cu (111) slab.

Figure 5.

(a) TDOS of Cu (111) surface and the adsorption system. (b) PDOS of Cu1s and Ga1s. (c) PDOS of Cu2p and Ga2p.

The redistribution of electrons can be mainly ascribed to the interactions between Ga atom and the nearby Cu atoms of Cu (111) slab. Figure 5b gives the PDOS curves of Cu1s and Ga1s for Ga atom adsorption on the clean Cu (111) slab. It is displayed that there are clear overlap peaks ranging from −9 eV to −1 eV between Cu1s and Ga1s orbitals. Figure 5c gives the PDOS curves of Cu2p and Ga2p for Ga atom adsorption on the clean Cu (111) slab, which shows that there are obvious overlap peaks ranging from −4 eV to 5 eV between Cu2p and Ga2p orbitals. The above results make clear that Ga atom adsorption is able to influence the electronic structure of the Cu atoms, indicating the formation of Cu-Ga bond.

As shown in Figure 6, the charge density difference in Ga atom adsorption on the clean Cu (111) surface is calculated. The dot map and cross-sectional view of the contour map are given in Figure 6a and Figure 6b, respectively. It is clear that the blue area and red area for the charge density difference, respectively, signify the electron depletion region and the electron accumulation region in Figure 6. And it can be obviously seen that electron accumulations exist between the Ga atom and nearby Cu atoms on the clean Cu (111) slab. This indicates that a number of electrons of Cu atoms have transferred to Ga atom, thus producing Cu-Ga bond. The phenomenon of charge transfer between Ga atom and adjacent Cu atoms is consistent with the analyses of DOS above in Figure 5. Therefore, we can draw a conclusion that a strong bonding interaction happens between Ga and Cu atoms.

Figure 6.

Charge density difference in Ga atom adsorbed on clean Cu (111) surface. (a) Three-dimensional dot view; (b) cross-sectional view of contour map.

3.3. Experimental Verifications

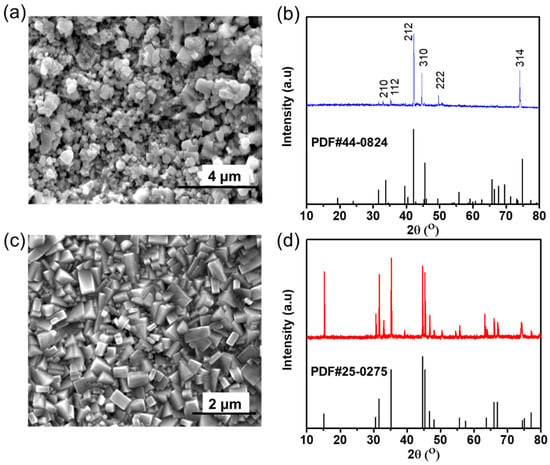

The above simulation results manifest that Ga atoms in the GLM can adsorb strongly on the surfaces of ferrous-based and copper-based metal, while the adsorption of In atoms in the GLM is weaker than that of Ga atoms. In order to verify the interactions between GLM and the surfaces of frictional pairs, SEM, XRD, and tribological experiments are carried out. After making GLM come in direct contact with the substrates, there are silver layers covering the surface of bearing steel and albronze. The characterization results are given in Figure 7. The SEM image in Figure 7a depicts that irregular and loose FeGa3 grains are formed. And from the XRD pattern in Figure 7b, it can be clearly seen that the peaks of the film are almost consistent with the standard card of FeGa3. The intensity difference in XRD pattern between the test results and standard card may be caused by the preferred orientation of grains and other oxide impurities, including Ga2O3 and In2O3. Figure 7c,d confirm the formation of the intermetallic CuGa2 layers with triangle-like grains, and the peaks of CuGa2 film ideally match with the standard card of CuGa2. The XRD peaks are indexed according to the ICDD international database, and the miller indexes are labeled.

Figure 7.

(a) Microstructure and (b) XRD pattern of FeGa3 film on bearing steel surface, (c) microstructure, and (d) XRD pattern of CuGa2 film on albronze surface.

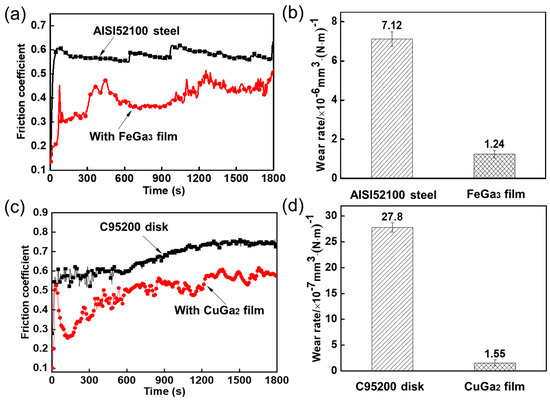

The tribological properties of formed FeGa3 film and CuGa2 film are demonstrated in Figure 8. As we can see in Figure 8a, the friction coefficient of FeGa3 film is lower than that of bearing steel, and the average friction coefficients of bearing steel with and without FeGa3 film are 0.40 and 0.57, respectively. Moreover, wear scar images of steel balls sliding against bearing steel disks with and without FeGa3 film are observed, and the wear rates of steel balls are calculated and given in Figure 8b. With FeGa3 film on the bearing steel surface, the wear rate can be reduced from 7.12 × 10−6 mm3(N·m)−1 to 1.24 × 10−6 mm3(N·m)−1. It should be mentioned that under the same tribological experimental condition, the friction coefficient and wear rate of the steel ball sliding against bearing steel with FeGa3 film are similar to those of the steel ball sliding against bearing steel substrates under GLM lubrication in our previous study [16]. This phenomenon indicates that FeGa3 film holds good lubricity, and the lubrication mechanisms of GLM can be ascribed to the interaction of Ga atoms with the surface of bearing steel.

Figure 8.

(a) Friction curves and (b) wear rates of AISI52100 steel substrate and FeGa3 film; (c) friction curves and (d) wear rates of C95200 albronze substrate and CuGa2 film.

In Figure 8c, in comparison with the friction coefficient at 0.67 of albronze substrate, the CuGa2 film shows a lower friction coefficient at 0.49, indicating the better anti-friction ability of the CuGa2 film than albronze substrate. For the sake of evaluating the anti-wear performance of the CuGa2 film, the wear rates of the substrate and the CuGa2 film are calculated according to Equations (1)–(3), and the results are show in Figure 8d. With CuGa2 film on the albronze surface, the wear rate can be reduced from 27.8 × 10−7 mm3(N·m)−1 to 1.55 × 10−7 mm3(N·m)−1. It can be concluded that the lubrication mechanisms of GLM for albronze frictional pairs can be ascribed to the formation of CuGa2 film.

4. Conclusions

In summary, the DFT calculations were adopted to conduct a detailed investigation into the adsorption of Ga and In atoms on Fe and Cu frictional pairs, respectively. And further interfacial interactional experiments and tribological experiments were carried out to verify the interactions between the Ga and In atoms of GLM and the surfaces of frictional pairs. Our results indicate that Ga atom prefers to adsorb on the bridge site of the Fe (111) surface, while the hollow site is the most stable adsorption site for Ga atom on the Cu (111) surface. In comparison with the In atom, the adsorptions of the Ga atom on both Fe (111) and Cu (111) surfaces are stronger, thus forming the Fe-Ga bond and Cu-Ga bond. The phenomenon of stronger adsorptions of Ga atom and the formation of new bonds are further verified by the XRD results, with peaks of FeGa3 and CuGa2. Tribological experiments also indicate that the lubrication mechanisms of GLM for bearing steel and albronze frictional pairs can be attributed to the formation of FeGa3 and CuGa2 tribofilms during frictional processes. With FeGa3 film on the bearing steel surface, the friction coefficient and wear rate can be reduced to 0.40 and 1.24 × 10−6 mm3(N·m)−1, while with CuGa2 film on the albronze surface, the friction coefficient and wear rate can be reduced to 0.49 and 1.55 × 10−7 mm3(N·m)−1.

Author Contributions

X.L. (Xing Li) and J.L. conceived and designed the project; J.L., X.L. (Xing Li), G.D. and R.W. performed the experiments; Y.T., X.L. (Xiaoliang Liang) and R.W. analyzed the data; J.L., Y.C. and X.L. (Xing Li) wrote the manuscript and supervised the study; X.L. (Xing Li) and D.L. supervised the project. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

X. Li acknowledges the financial support received from the National Science Fund for Young Scholars (52505500), Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2023QE170) and the Collaborative Innovation Center for Shandong’s Main crop Production Equipment and Mechanization (SDXTZX-20). J. Li acknowledges the financial support received from Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation Excellent Young Scientists Fund Overseas (2024HWYQ-025), Taishan Scholar Young Expert of Shandong Province (tsqn202312034), Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2023ME026), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2024A1515012074), National Key Laboratory of Spacecraft Thermal Control (NKLST-JJ-202401010), and Qilu Youth Scholar Program of Shandong University. Authors also acknowledge the support received from Double-Hundred Talent Plan of Shandong Province (WSR2023047).

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, X.; Ma, J.; Guo, J.; Chen, J.; Tan, H.; Cheng, J.; Zhu, S.; Yang, J. Current-carrying lubricating behavior of gallium-based liquid metal for Cu/Al tribo-pair. Wear 2025, 564–565, 205715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Gao, W.; Duan, L.; Li, Q.; Gong, S.; Li, R.; Zhang, J. Performance analysis of Gallium-based liquid metal as thermal interface material for chip heat dissipation. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2025, 218, 110121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, W.F. Magnetohydrodynamic Lubrication and Application to Liquid Metals. Ind. Lubr. Tribol. 1963, 15, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerkema, J. Gallium-Based Liquid-Metal Full-Film Lubricated Journal Bearings. ASLE Trans. 1985, 28, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R.G.; Burton, R.A. Gallium alloy as lubricant for high current density brushes. IEEE Trans. Compon. Hybrids Manuf. Technol. 1988, 11, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kezik, V.Y.; Kalinichenko, A.S.; Kalinitchenko, V.A. The application of gallium as a liquid metal lubricant. Int. J. Mater. Res. 2003, 94, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Guo, S.; Chen, J.; Li, B.; Dong, G. Gallium-based liquid metal as a special lubricant: A review. Friction 2025, 3, 9441047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, R.; Cai, Y.; Xu, B.; Shi, Z.; Li, J. Biomimetic eco-friendly matter-repellent surfaces with superior soil adhesion resistance. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 56, 105630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, X.; Li, W.; Yang, L.; Li, X.; Wang, L. Nature-inspired reentrant surfaces. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 133, 101064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tian, P.; Lu, H.; Jia, W.; Du, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, Q.; Tian, Y. State-of-the-Art of Extreme Pressure Lubrication Realized with the High Thermal Diffusivity of Liquid Metal. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 5638–5644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Qi, P.; Liu, Q.; Dong, G. Improving tribological behaviors of gallium-based liquid metal by h-BN nano-additive. Wear 2021, 484, 203852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Yuan, Y.U.; Zhu, S.; Qian, Y.E.; Yang, J.; Liu, W. Lubrication Characteristics of Multifunctional Liquid-State Metal Materials under Different Sliding-Pairs. Tribology 2017, 37, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, X.; Guo, J.; Tan, H.; Cheng, J.; Zhu, S.; Yang, J. Lubricating behavior of gallium-based liquid metal for Cu/Al tribo-pair. Tribol. Int. 2024, 200, 110090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; He, B.; Xue, S.; Chen, X.; Liu, S.; Ye, Q.; Zhou, F.; Liu, W. Supramolecular gelator functionalized liquid metal nanodroplets as lubricant additive for friction reduction and anti-wear. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 653, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; He, B.; Liu, S.; Ye, Q.; Zhou, F.; Liu, W. Fabrication of ionic supramolecular oleogel lubricants enhanced with liquid metal nanodroplets for superior tribological performance. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 33468–33478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Tong, Z.; Ma, Q.; Ni, Y.; Dong, G. Enhanced lubrication effect of gallium-based liquid metal with laser textured surface. Tribol. Int. 2019, 129, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Dong, G. Preparation of nanoscale liquid metal droplet wrapped with chitosan and its tribological properties as water-based lubricant additive. Tribol. Int. 2020, 148, 106349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, R.; Li, J.; Dong, G.; Song, Q.; Wang, B.; Liu, Z. Gallium-based liquid metal hybridizing MoS2 nanosheets with reversible rheological characteristics and enhanced lubrication properties. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 20365–20372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Wu, H.; Dong, J.; Yin, S.; Feng, N.; Hua, K.; Wang, H. Enhancing Lubrication Performance of Ga–In–Sn Liquid Metal via Electrochemical Boronising Treatment. Lubr. Sci. 2025, 37, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Cheng, J.; Wang, S.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, S.; Yang, J.; Liu, W. A Protective FeGa 3 film on the steel surface prepared by in-situ hot-reaction with liquid metal. Mater. Lett. 2018, 228, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Jin, G.; Xue, S.; Liu, S.; Ye, Q.; Zhou, F.; Liu, W. Laser manufactured-liquid metal nanodroplets intercalated Mxene as oil-based lubricant additives for reducing friction and wear. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 187, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Shao, Y. Graphyne-based single atom catalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction: A constant-potential first-principles study. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 22066–22073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.E.; Carter, E.A. Carbon atom adsorption on and diffusion into Fe(110) and Fe(100) from first principles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 71, 045402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.C.; Zhang, J.M.; Xu, K.W. First-principles study of the adsorption of oxygen atoms on copper nanowires. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 2012, 55, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Cheng, Z.; Lu, Z.; He, Q. Advances in DFT-Based Computational Tribology: A Review. Lubricants 2025, 13, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hande, U.; Daniele, T. Tribology at the atomic scale with density functional theory. Electron. Struct. 2022, 4, 023002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuwono, J.A.; Birbilis, N.; Taylor, C.D.; Williams, K.S.; Samin, A.J.; Medhekar, N.V. Aqueous electrochemistry of the magnesium surface: Thermodynamic and kinetic profiles. Corros. Sci. 2019, 147, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.D.; Neurock, M.; Scully, J.R. First-Principles Investigation of the Fundamental Corrosion Properties of a Model Cu38 Nanoparticle and the (111), (113) Surfaces. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2008, 155, C407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Yang, J.; Pang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhan, Y. Enhanced C atom adsorption on Cu(111) substrate by doping rare earth element Y for Cu–diamond composites: A first-principles study. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 831, 154747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, M.; Gupta, M.; Gupta, R.P. Electronic origin of the anomalous segregation behavior of Cr in Fe-rich Fe-Cr alloys. Physics 2012, 85, 064111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peljhan, S.; Kokalj, A. Adsorption of Chlorine on Cu(111): A Density-Functional Theory Study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 14363–14376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.