Abstract

As a critical sealing component in aero-engines, the segmented annular seal is prone to friction and wear during the running-in stage, which seriously impairs its sealing performance and service life. To address this issue, this study takes the three-petal segmented annular seal made of T482 graphite as the research object, adopting a combined method of high-speed ring-block friction and wear tests and thermal–fluid–solid coupling simulation to investigate its friction and wear mechanisms and optimize its structural design. The results show that the segmented annular seal undergoes more severe friction and wear in the low-speed running-in stage; the wear rate increases with the rise in loading force and decreases with the increase in rotational speed, and the variation trend of surface roughness is consistent with that of the friction coefficient. Frictional heat and wear-induced scratches intensify the deformation and leakage of the seal, thereby leading to the risk of seal failure. Optimizing the depth of radial dynamic pressure grooves can significantly improve the opening performance of the seal, while optimizing the width of axial grooves mainly affects the seal leakage. This research provides a theoretical basis for improving the service life and sealing performance of segmented annular seals in aero-engines.

1. Introduction

The sealing property between key components of aero-engines has always been an unavoidable topic in the process of engine design and manufacturing. Due to the various rotating structures inside the engine and the existence of a large number of dynamic and static contact surfaces, efficient sealing devices are needed to tightly seal the mechanical connection interfaces to reduce fluid leakage. As a new sealing technology, the segmented annular seal was first invented and improved by NASA [1] based on the end face seal and applied to the helium gas seal of aerospace engines. In recent years, as an important component of the sealing device of aero-engines, the segmented annular seal has been able to better cope with increasingly severe sealing conditions. Thus, it has received extensive attention from scholars. The segmented annular seal is an adaptive sealing structure that can automatically adjust the gap between the sealing ring and the shaft to ensure that the gap between the shaft and the sealing ring is minimized without friction, thereby withstanding a higher-pressure difference [2].

Compared with the common floating ring seal, the segmented annular seal has the advantages of compact structure, easy assembly and lower leakage [3,4,5]. However, the friction and wear problem during the opening process of the segmented annular seal objectively exists, which affects the service life of the sealing structure and leads to its failure. Scholars have proposed that the dynamic pressure segmented annular seal with shallow grooves on the inner surface of the ring segment can enhance the hydrodynamic pressure effect, thereby improving the overall opening performance of the split float ring seal, enabling the fluid dynamic seal to form as soon as possible, and thus reducing the high-speed friction and wear caused by the contact between the ring segment and the rotor [6].

The research directions on segmented annular seals mainly focus on friction and wear tests, physical field simulation analysis, and numerical calculations. Yan et al. [7] conducted high-temperature friction and wear experiments on graphite M210 sealing materials and found that the coefficient of friction first increased, then decreased, and finally stabilized with the rise in temperature, reaching the lowest point at 450 °C. The wear rate continued to rise, and a friction and wear performance prediction model was established based on the grey theory. Ma et al. [8] found that there is an optimal range (4 to 5 N/m) for the circumferential spring specific pressure of the annular segment floating seal, within which the leakage is relatively low through experimental research. Excessive spring force will accelerate wear, causing abrasive wear and adhesive wear. Therefore, under the premise of meeting the sealing requirements, a smaller spring force should be selected. Wang et al. [9] studied a segmented annular seal using the finite element method and found that under high pressure difference and high rotational speed conditions, frictional heat generation would lead to thermal deformation of the sealing surface and an increase in leakage. Li et al. [10] found that the wear rate of a three-piece high-speed segmented annular seal increases significantly with the rise in pressure and rotational speed through a combination of numerical simulation and experiments. Meanwhile, the circumferential spring specific pressure can simultaneously control leakage and wear within a certain range, which is a key sensitive parameter affecting the friction and wear performance of the seal. Wang et al. [11] found that with the increase in friction duration, the friction coefficient of a circular graphite seal first decreased rapidly, then slightly increased, and finally levelled off. Moreover, the wear amount increased significantly with the increase in the types and quantities of grooves on the surface of the sealing ring. Hady [12] measured the operating temperature, leakage, friction torque and wear of a conventional circumferential graphite seal and compared it with the improved conventional circumferential graphite seal with an automatic floating structure. It was found that when the automatic floating circumferential graphite seal operates at a lower temperature, its torque is half that of the conventional circumferential graphite seal, and its wear is approximately one-tenth of that of the conventional circumferential graphite seal.

Under complex working conditions, unreasonable clearance design and matching can easily lead to excessive wear and seal failure. Excessive deformation of the sealing ring is often the key factor causing wear of the main sealing surface and excessive leakage. Some scholars have conducted simulation research on segmented annular seals by means of the multi-physics coupling method.

Zhou et al. [13] established a multi-field coupling analysis model based on a four-petal graphite seal and studied the flow field, temperature field and structural field characteristics of the graphite seal under conditions of high linear velocity and low-pressure difference. Chen et al. [14] established a multi-field coupling model of mixed lubrication for graphite circumferential seals using a semi-analytical solution method to study the sealing performance of the main and secondary sealing channels of graphite circumferential seals. Yun et al. [15] established a mechanical theoretical model of the circular spring in a circular graphite seal, analyzed the causes of the uneven distribution of the spring force, and studied the influence of the uneven circular spring force on the deformation of the sealing ring. Zheng [16] optimized the parameters of a circumferential spring and analyzed and solved the force of the circumferential spring under the premise of ensuring the sealing performance and followability.

To further optimize the opening characteristics, Arghir et al. [17] established a segmented annular seal model with micro-textures set on the outer surface of the rotor, studied the influence of the inclined grooves on the rotor, and proposed two numerical simplified models to solve the sealing opening force. Fourt et al. [18] studied the influences of pad waviness, groove depth and spring force on the characteristics of a segmented annular seal under given steady-state operating conditions, calculated the equilibrium positions of each seal flap, and further calculated the leakage and torque of the seal. Alessio et al. [19] studied the influence of a segmented annular seal on seal leakage and wear under the conditions of radial axial offset, angular offset, and the coexistence of both. Oike et al. [20] analyzed the leakage characteristics of a segmented annular seal under all working conditions and clearly characterized the wear morphology of the seals.

It can be concluded from the literature review that the combination of test and simulation methods enables a better investigation of the operating mechanism of segmented annular seals. This paper takes a three-petal segmented annular seal as the research object, describes the friction and wear conditions of the segmented ring before opening, studies the harm of friction and wear to the segmented annular seal, and explores its basic opening mechanism and opening effect, and by using different optimization designs for the ring, a better opening effect can be achieved, thereby reducing friction loss and increasing the life of the seal.

2. Numerical Model

2.1. Working Principle

2.1.1. Theoretical Model

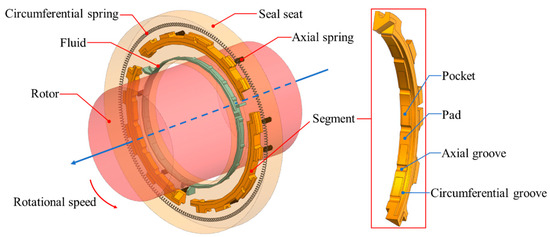

The structure of the segmented annular seal is shown in Figure 1. It is divided into the main sealing structure and the secondary sealing structure. The main sealing structure is mainly composed of a sealing ring body made of graphite material, consisting of 3 to 6 segments, which are tightly fastened to the circumferential spring on the rotor. The secondary sealing structure mainly consists of a sealing seat that wraps around the sealing ring, which serves to protect the main seal and prevent trace leakage. The sealing ring is fixed to the sealing seat under the compression action of the axial spring. The inner surface of the segment is usually provided with axial grooves and circumferential grooves to introduce fluid for lubrication. Some segments also have pockets on their inner surfaces to increase the opening force, enabling the sealing ring to reach a non-contact state as soon as possible, thereby reducing the friction loss of the sealing ring and extending its life.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the segmented annular seal.

When the engine is stationary, the sealing ring forms a relatively good static seal by means of the closing force provided by the circumferential spring and the high-precision surface that fits with the rotor. As the rotor rotates, the sealing ring opens, and a non-contact dynamic seal begins to form. A fluid domain is formed between the inner surface of the sealing ring and the rotor as the main leakage channel, and at the same time, a hydrodynamic pressure effect is generated to maintain the stable operation of the dynamic seal.

2.1.2. Force Analysis

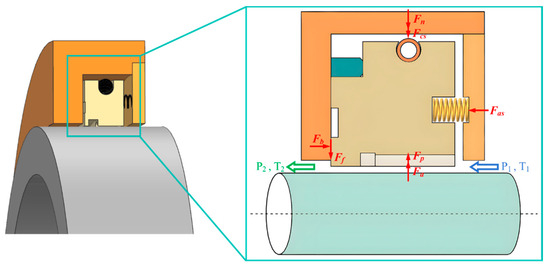

When the segmented annular seal is stably open, the radial force satisfies the following equilibrium equation:

In the formula, Fp is the hydrodynamic pressure provided by the gas film in the main sealing gap, and Fa is the supporting force provided by the rotor. Fn is the circumferential pressure generated by the medium in the sealed cavity, Fcs is the clamping force provided by the circumferential spring, Ff is the frictional force between the sealing seat and the segment, Fas is the axial force generated by the compression spring and the medium pressure, and μ is the friction coefficient between the sealing seat and the segmented annular seal. The Fp hydrodynamic pressure on the right side of the equal sign in Equation (1) provides the opening force for the segmented annular seal. Fn + Fcs + Ff on the left side of the equal sign in Equation (1) is called the opening resistance. The force analysis of the segmented annular seal is shown in Figure 2. By analyzing the opening force and opening resistance, the operating status of the seal can be better judged.

Figure 2.

Force schematic of segmented annular seal.

2.1.3. The Working Process of the Segmented Annular Seal

The working process of the segmented annular seal mainly consists of two stages: the running-in stage and the normal working stage.

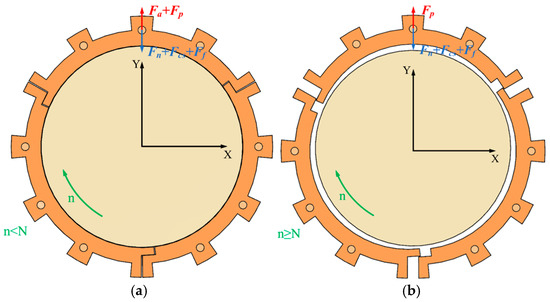

The first stage is the sealed running-in stage. When the engine is stationary, due to the “tightening” effect of the circumferential spring, the s segmented annular seals are closely attached to the rotor, and the inner diameter of the segmented annular seals is slightly smaller than the outer diameter of the metal. When the rotor starts to rotate, at this time, the rotational speed of the rotating shaft is less than the opening speed of the seal, the opening force is less than the opening resistance, the fluid dynamic seal is not opened, and there is relative motion between the graphite ring and the rotor. Due to the lower hardness of the graphite ring compared to the metal, under the action of continuous relative motion, the main sealing surface of the graphite ring undergoes high-speed friction and wear in this state, the fluid pressure Fp increases with the increase in rotational speed, the hydrodynamic pressure effect intensifies, and the rotor support force Fa decreases. When the opening rotational speed is reached, Fa = 0, and the segmented annular seal slightly adheres to the rotor. At this time, the force balance equation is

At this point, the opening force is equal to the opening resistance, and the inner diameter of the segmented annular seal is theoretically equal to the outer diameter of the metal track. The state of the sealing component is shown in Figure 3a. At this stage, the friction and wear of graphite ring segments at high rotational speeds can mainly be studied through experimental methods.

Figure 3.

The working process of the segmented annular seal: (a) running-in stage; (b) working stage.

The second stage is the sealed normal operation stage. Under the effect of relative motion, the segmented annular seal and the metal track generate a large amount of frictional heat, causing both the segmented annular seal and the metal track to rise to a certain temperature. When the metal track rotates at high speed, the dynamic pressure generated by the fluid overcomes the opening resistance such as the frictional force of the sealing seat and the elastic force of the circumferential spring, causing the segmented annular seal to gradually move away from the rotor track along the radial direction. The segmented annular seal is fully opened and segment connects from the metal track, and the thickness of the gas film begins to increase. The state of the sealing assembly is shown in Figure 3b.

As the hydrodynamic pressure Fp increases, the segmented annular seal moves away from the rotor under the action of the fluid pressure. At this time, the circumferential spring is stretched, and the spring force increases, allowing the equilibrium state of Equation (3) to continue to be maintained. When the rotor speed stabilizes, the hydrodynamic pressure no longer changes with the speed, and the segmented annular seal no longer undergoes significant displacement. Under the combined action of the opening force and opening resistance, it vibrates slightly back and forth along the radial direction. At this time, the sealing gap changes to a certain extent. When the sealing gap increases, the hydrodynamic pressure effect weakens, the opening force decreases, and the seal tends to close, resulting in a reduction in the sealing gap, an increase in the hydrodynamic pressure effect, and an increase in the opening force, and the seal tends to open. At this point, a dynamic equilibrium is formed; the seal is stably formed at this rotational speed. In the second stage, the operating principle of the seal is studied and optimized design is carried out through fluid simulation and multi-physics field coupling methods. By optimizing the structure to change the opening force, the seal can reach a stable operating state more quickly, which is conducive to reducing heat generation and wear and extending the service life of the segmented annular seal.

2.2. Computational Equation

The key research object during the normal operation stage of the segmented annular seal is the sealing fluid gap, and it is necessary to establish the fluid control equation for the sealed gas. To simplify the fluid calculation and analysis process, the following assumptions are made for the fluid domain:

- (1)

- Ignore the trace amount of lubricating oil contained in the gap and consider the fluid in the gap to be a compressible ideal gas single-phase flow;

- (2)

- The gas flow in the sealed gap is continuous;

- (3)

- Gases do not undergo sliding motion at solid interfaces.

Based on the above assumptions, the basic physical equations that need to be followed to seal the gas are constructed. The continuity equation is expressed as

In the formula, u, v, and w represent the velocity components of the fluid in the x, y, and z directions, respectively.

The Reynolds equation for fluids is expressed as

In the formula, a represents the thickness of the sealing gap, U is the surface velocity of the fluid, and μ is the viscosity of the fluid.

Fluid mechanics analysis indicates that the Reynolds number (Re) under the current working conditions is in the low value range, meeting the application conditions of laminar flow theory. However, under the combined effect of the high-speed running sealing and the complex channel structure, the airtight medium in the gap area shows turbulent characteristics, and the traditional laminar flow simulation method struggles to accurately describe its flow characteristics. For this purpose, numerical calculations are carried out through the RNG k-ε model in this paper. This model enhances the analytical accuracy of curved wall circumferential flow and rotational flow by correcting the vortices viscosity coefficient and is applicable to the high-complexity outflow field problem involved in this paper [21]. The fluid control equation is obtained as

In the formula, μt represents the turbulent viscosity coefficient.

The contact state of the solid domain involved in this paper belongs to high-speed nonlinear behaviour and is often solved by the finite element method. The equilibrium state of the sealing ring under hydrodynamic pressure can be solved by the solid-state-domain control equation [22]:

In the formula, M represents the mass matrix, C is the damping matrix, K is the stiffness matrix,

,

, and

are the acceleration vector, velocity vector and displacement vector, respectively, and F(t) is the load vector of the graphite sealing ring.

The solid-state-domain model is used for frictional heat calculation and a transient solver is used for calculation to understand the heating process. The calculation equation for frictional heat [23] is

In the formula, n represents the rotational speed, D0 is the diameter of the rotor, B is the width of the sealing ring, pc is the contact load of the main sealing surface, and f is the friction coefficient of the main sealing surface.

The coupling interface between the sealing gas in the sealing gap and the graphite seal should satisfy the equality of displacement, stress, temperature and heat flux density; that is, the governing equations for thermal–fluid–solid coupling are expressed as [24]

In the formula, m is the normal vector of the coupling interface; τf and τs are the stresses on the contact surfaces of the sealing gas and the solid; df and ds are the displacements of the sealing gas and the solid; Qf and Qs are the heat flux densities on the contact surfaces of the fluid domain and the solid domain; and Tf and Ts are the temperatures on the contact surfaces of the sealing gas and the solid domain.

During the calculation of the thermal–fluid–solid coupling model, it is necessary to transfer data at the coupling interface to solve the deformation of the solid domain. After incorporating heat calculation, according to Fourier’s law, the convective heat flux qw [25] between the seal and the sealing gas at the fluid–solid coupling interface is

In the formula, λ is the thermal conductivity of the sealing fluid.

2.3. Test Description

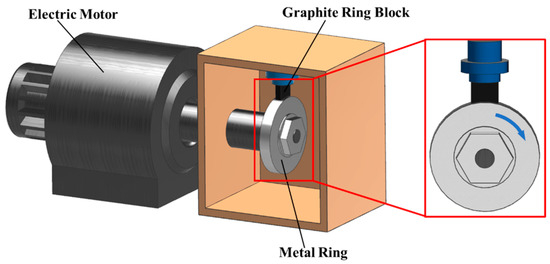

The test in this study was a high-speed ring-block friction and wear test, and the test principle is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The principle of high-speed ring-block friction and wear test.

High-speed ring-block friction and wear test is a testing method used to evaluate the wear resistance of materials under high-speed friction conditions. The two samples to be tested are installed on the test bench. Among them, the metal ring is installed on the main shaft of the motor and can rotate at high speed driven by the motor. The graphite block is installed in the fixture and a certain load is applied to rub against the metal ring to simulate the high-speed friction and wear process of the material in the actual process. By rotating the annular sample and making it in fixed contact with the graphite block, the high-speed friction condition is simulated. By changing the load, rotational speed and type of graphite material, the changes in the friction coefficient, friction force and surface roughness are observed to infer the relationship between each factor and high-speed friction wear and to study the wear behaviour of the material surface caused by frictional heat and mechanical stress. By analyzing the high-speed friction and wear between the segmented annular seal and the rotating shaft before it floats up, the friction and wear process and wear mechanism in the formation of the segmented annular seal are explored.

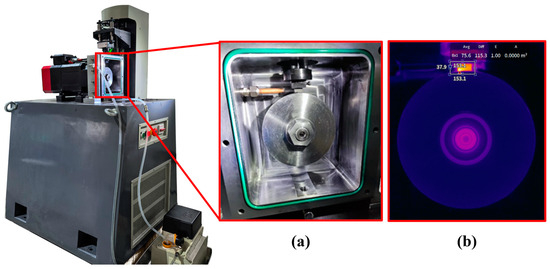

To complete the high-speed graphite ring-block friction and wear test, a high-speed ring-block friction and wear test bench was designed and used, as shown in Figure 5, and was equipped with corresponding measurement and detection equipment. The high-speed ring-block friction and wear test bench could simulate the actual working state of the sample under the action of high speed and force load and study the high-speed friction and wear process of graphite ring-blocks under real working conditions, and at the same time, the control end of the test bench could output result parameters such as the friction coefficient and friction force. Through the thermal imager, the change in temperature with time was recorded for the analysis of the law and mechanism after the test.

Figure 5.

High-speed ring block friction and wear test bench: (a) Friction and wear specimen mounting area. (b) Thermal infrared imaging of the specimen mounting area.

The samples for this test were the upper sample made of T482 graphite material and the lower sample made of GH4169 superalloy. The material parameters are shown in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Performance parameters of T482 graphite material.

Table 2.

Performance parameters of GH4169 superalloy.

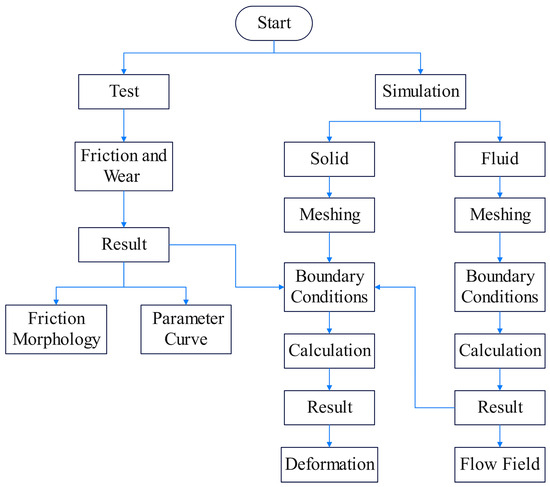

2.4. Flow Chart

The main research process of this article is shown in Figure 6. Firstly, through friction and wear tests, the surface friction and wear morphology and wear rate of the graphite material were obtained. Then, the parameters such as the friction coefficient, friction force, and temperature in the tests were plotted and analyzed in accordance with the rules. The fluid in the sealed gap was simulated and calculated through fluent to analyze the flow field characteristics. By combining the friction force and temperature obtained from the friction test, as well as the temperature and pressure calculated from the fluid, with the solid-domain analysis, the thermal–solid coupling and thermo-fluid–solid coupling calculations were carried out to obtain the deformation characteristics of the graphite ring segment, which intuitively reflected the harm of friction wear and frictional heat generation to the segmented annular seal. Finally, the structure of the segmented annular seal was optimized by designing pocket and micro-textures, and simulation calculations of the sealing fluid were carried out. The leakage volume and hydrodynamic pressure were analyzed to determine the optimization results, and the optimization theory was summarized.

Figure 6.

Calculation flow chart for the combination of testing and simulation.

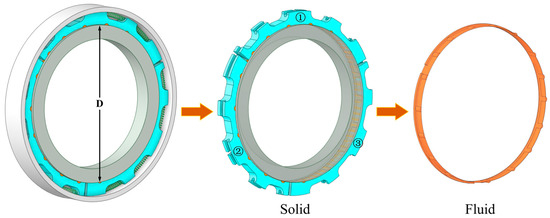

2.5. Calculation Model

The simulation research object used in this paper is a contact segmented annular seal. The calculation model is shown in Figure 7, and the model parameters are shown in Table 3. Based on this model, solid-state-domain analysis, flow field analysis and structural optimization design were carried out. The solid domain is the gap between the rotor and the sealing ring, and the fluid domain is the main sealing fluid gap. The key research objects of this paper include the flow field characteristics of the main seal of the segmented annular seal, and thus the fluid gap at the lap joint of the ring segments is ignored.

Figure 7.

The solid domain and fluid domain of the computational model.

Table 3.

Parameters of the segmented annular seal model.

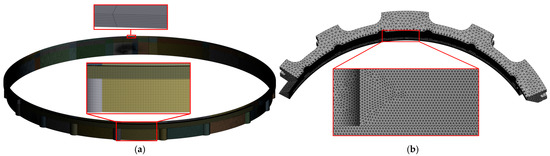

2.6. Grid Division Method

The fluid domain was meshed by the sweeping method. The main seal gap was divided into four parts: the air film, the pocket, the circumferential groove and the axial groove. Meshing was carried out for each of the four parts, respectively. If the thickness of the gas film was greater than 10 microns, the grid could be generated by the method of overall sweeping and external surface grid division. If the thickness of the gas film was less than 10 microns, the gas film needed to be pre-treated and swept in sections to generate the grid. The meshing of the fluid domain is shown in Figure 8a. The size of the gas film varied significantly by orders of magnitude compared with other regions. To ensure calculation accuracy, the size of the gas film in the thickness direction needed to be additionally densified. Tetrahedral meshes were used for solid-domain meshing. The fluid-solid contact surface needed to be additionally densified, and the element size was 0.1 mm. The meshing of the solid domain is shown in Figure 8b.

Figure 8.

Computational model meshing method: (a) Fluid domain. (b) Solid domain.

2.7. Simulation Validation

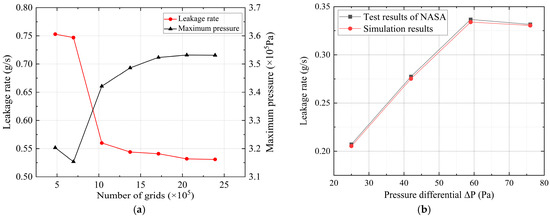

The results of grid independence are shown in Figure 9a. With the change in the number of grids, the leakage rate and the maximum pressure tend to stabilize. At this point, the total number of grids is determined to be 2 million. The calculation results are relatively accurate, with less waste of computing power and high calculation efficiency. At the same time, the thickness of the air film is determined to be encrypted by 7 layers. In subsequent calculations, the fluid domain in the pocket needs to be encrypted to 5 layers to ensure the accuracy of the calculation. Figure 9b shows the comparison of the leakage in the fluid domain of the segmented annular seal at a rotational speed of 500 revolutions per second (rps) and pressure differences of 0.25 MPa, 0.42 MPa, 0.59 MPa, and 0.76 MPa, respectively, with the data in reference [6]. As can be seen from Figure 9b, the calculated data is in good agreement with the data in the literature, and the maximum deviation of the leakage is 3%. This indicates that the adopted calculation method is feasible.

Figure 9.

Simulation validation: (a) Grid independence validation. (b) Model validation.

3. Results

3.1. Surface Morphology

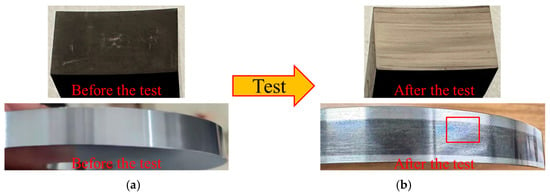

The wear degree of the graphite ring block was relatively uniform at high rotational speeds, the physical comparison diagrams before and after the test are shown in Figure 10. After high-speed friction, the arc-shaped surface showed a certain metallic lustre, was covered with scratches, and became visibly smooth; the frictional surface of the ring block exhibits light reflection and appears off-white in the photograph. Thanks to the self-lubricating effect of the graphite material, the overall surface roughness of the ring block decreased [26]. During the high-speed friction process, under the influence of graphite and frictional heat, the metal ring of the lower sample underwent sintering to varying degrees, with local areas presenting a bluish or bluish purple colour. Moreover, the graphite adhered closely to the metal ring and was difficult to remove.

Figure 10.

Comparison of physical pictures of the sample before and after friction test: (a) The friction surfaces of the upper and lower samples before the test. (b) The friction surfaces of the upper and lower samples after the test.

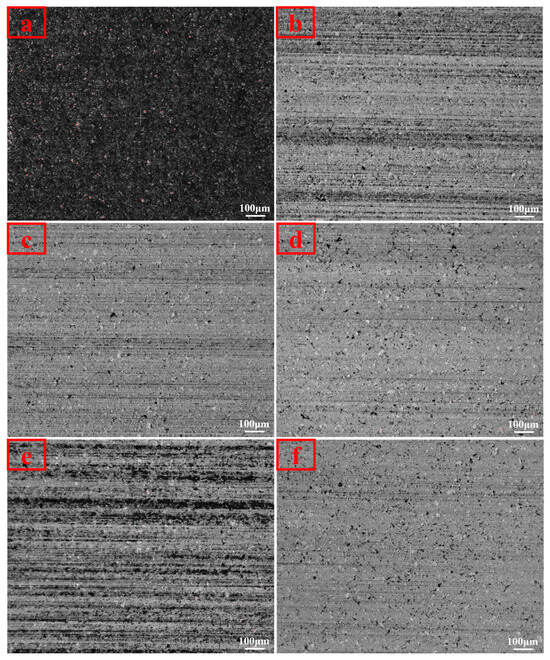

Through the measurement and analysis of the surface morphology of the T482 graphite ring block, it was found that the initial surface of the test piece may have had certain processing defects, and some test pieces may have had surface pits and scratches. However, the overall roughness met the test requirements and the test could be carried out. Figure 11 shows a microscopic schematic diagram of the surface morphology of a graphite ring block after high-speed friction with a metal ring under different loading conditions. By comparison, it can be seen that through the high-speed ring block friction and wear test, the samples on the graphite ring block had different degrees of wear under different loading forces and rotor speeds. After a certain period of high-speed friction, the reflection on the surface of the graphite ring block became clearer and its brightness was higher than it was before the friction. The irregular marks originally caused by processing became shallower and fewer under the effect of high-speed friction and were replaced by regular grinding marks along one direction. There were some pits caused by the shedding and wear of graphite on the surface of the ring block, as well as some graphite particles. Under conditions of low rotational speed and low loading force, the wear marks on the surface of the graphite ring block were densely and evenly distributed, and scratches were more likely to occur. When the rotational speed remained constant, as the loading force increased, the wear marks became shallower and fewer. Under the condition that the loading force remained constant, as the rotational speed increased, the wear marks also became shallower and fewer.

Figure 11.

Microscopic diagram of the surface morphology of the graphite ring block: (a) the microscopic morphology before friction and wear; (b) the friction and wear morphology of the ring block under the loading condition of 16,000 rpm to 10 N; (c) the friction and wear morphology of the ring block under the loading condition of 16,000 rpm to 20 N; (d) the friction and wear morphology of the ring block under the loading condition of 16,000 rpm and 30 N; (e) the friction and wear morphology of the ring block under the loading condition of 12,000 rpm and 30 N; (f) the friction and wear morphology of the ring block under the loading condition of 14,000 rpm and 30 N.

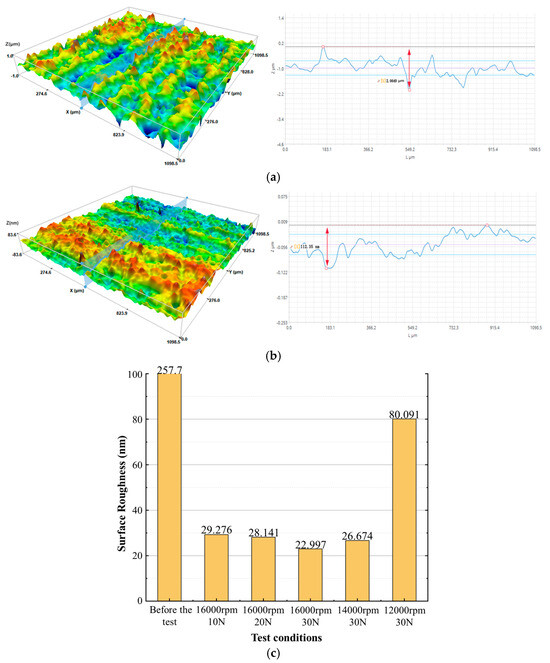

The morphology, roughness and scratch depth of the friction surface of the ring block before and after the test were measured by a white light interferometer, and the influence of friction and wear on the graphite ring block was further analyzed. The results are shown in Figure 12. According to the roughness of the high-speed ring block of T482 material before friction in Figure 12a, there were a large number of “spike synapses” on its surface, with processing scratches roughly along the Y-axis, that is, the axial direction. The surface roughness was obtained by cutting along the interface in the X-axis in one dimension. The difference between the deepest part of the scratch and the highest point of the synapse was 2.0649 μm, and the surface roughness of the ring block was approximately 0.2577 μm. According to the friction and wear conditions of the T482 ring block under the working conditions of 16,000 rpm and 30 N in Figure 12b, the wear marks on the surface of the ring block were relatively evenly distributed, with a small number and low depth. Compared with the conditions before friction, a large number of spike-shaped synapses were rubbed off, and the wear marks presented a band-like distribution along the X-axis, that is, the circumferential direction. One-dimensional roughness was obtained by cutting the interface along the X-axis. The difference between the deepest part of the wear mark and the highest point of the synapse was approximately 112.35 nm, and the surface roughness of the ring block was approximately 22.997 nm. Using the same method, the surface roughness of the graphite ring block under various working conditions was measured and statistically analyzed to obtain Figure 12c. It can be seen that the surface roughness of the ring block was larger before the friction test and smaller after the test. Moreover, as the test force increased, the roughness decreased, and as the rotational speed decreased, the roughness increased.

Figure 12.

Analysis of the surface roughness of blocks: (a) Before-test graphite surface morphology and roughness. (b) Post-test graphite surface morphology and roughness. (c) Surface roughness of graphite ring blocks before each working condition.

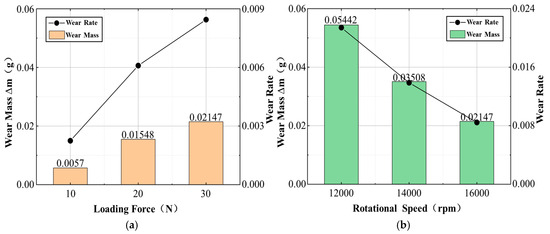

The mass of the graphite ring blocks before and after the friction test was weighed, and the wear mass and wear rate were calculated. The different wear conditions caused by the changes in loading force and rotational speed were compared. The results are shown in Figure 13. Under the condition that the rotational speed was both 16,000 rpm, with the increase in loading force, the wear rate of the ring blocks increased, and the differences in the average wear mass of the ring blocks were approximately 0.01 g and 0.006 g, respectively. When the loading force was all 30 N, as the rotor speed increased, the wear rate of the ring blocks decreased. The differences in the average wear mass of the ring blocks were approximately 0.02 g and 0.0136 g, respectively. It can be inferred that compared with the loading force or the elastic force of the circumferential spring, the rotor speed is an important factor affecting the friction and wear of the segmented annular seal. The friction and wear of the graphite ring mainly occur during the low-speed running-in stage before the opening of the float ring seal. When the speed stabilizes and approaches the opening speed, the friction and wear are relatively lower. Therefore, making the rotor speed reach the opening speed faster is an important method to reduce the friction and wear of the segmented annular seal.

Figure 13.

Changes in the wear quality and wear rate of ring blocks: (a) The influence of load force on wear mass and wear rate. (b) The influence of rotational speed on wear mass and wear rate.

3.2. Parameter Curves of the Test

By processing the data obtained after the test and conducting graph analysis, the variation patterns of the parameters could be better summarized. Due to the relatively high noise of the original curve, smoothing processing was carried out in the subsequent data processing to suppress high-frequency jitter and better preserve the changing trend of the parameter curve.

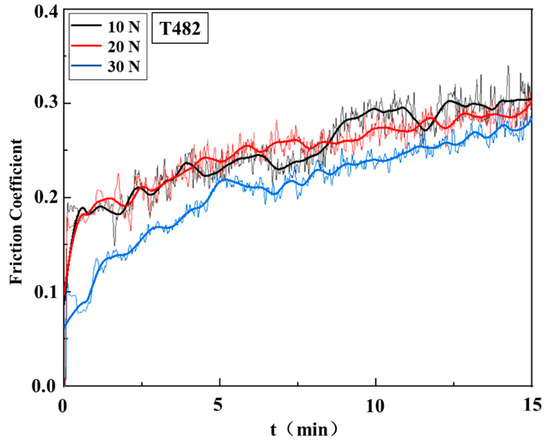

Figure 14 shows the surface friction coefficient–time curve graph of the high-speed ring-block friction and wear test of T482 graphite material under the same ambient temperature and the same metal ring speed conditions, with only the loading force (10 N, 20 N, 30 N) changed. Due to the loss of materials caused by friction and wear, the surface of the graphite ring block and the surface of the metal ring separated. However, the loading force maintained a dynamic equilibrium, forcing the surface of the ring block to come into contact with the surface of the metal ring. Under this state, the measured frictional force had certain fluctuations, which also caused the final measured friction coefficient to fluctuate to a certain extent. Test errors may have occurred at the start of the test due to factors such as test operations, materials wear and spalling, and ambient conditions. Therefore, the analysis was mainly conducted on the data obtained after the 7 min stabilization period. Overall, all curves go through the process of “transient initiation–climbing–near-steady state”. The three curves rapidly rise from the low point within 0 to 1 min and then monotonically rise. The friction coefficients at the ends of the three curves are all within the range of 0.25 to 0.30. During the stable stage of the curve after 10 min, the positional relationship of the three curves is as follows: the friction coefficient curve under a 10 N loading force is at the top, the friction coefficient curve under a 30 N loading force is at the bottom, and the friction coefficient curve under a 20 N loading force is in the middle. This indicates that the friction coefficient on the surface of the ring block decreased as the loading force increased, which followed the variation law of roughness with the loading force.

Figure 14.

Friction coefficient–time curves under different loading forces.

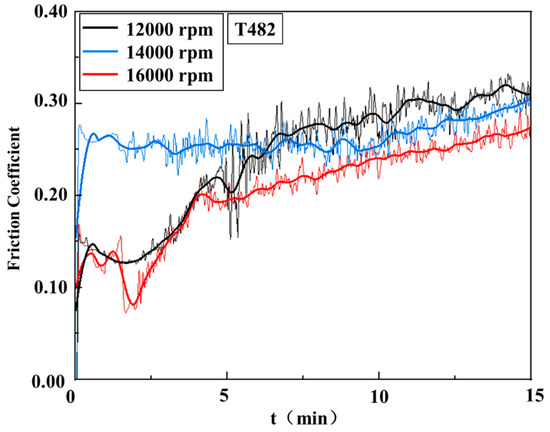

Figure 15 shows the surface friction coefficient–time curve graph of the high-speed ring-block friction and wear test of T482 graphite material under the same ambient temperature and loading force conditions, with only the metal ring speed (12,000 rpm, 14,000 rpm, 16,000 rpm) changed. Similarly to Figure 14, it shows certain fluctuations in the coefficient of friction. Generally speaking, all curves go through the process of “transient initiation –climbing–near-steady state”. The coefficient of friction is the highest at 14,000 rpm at the start. In thermal imaging detection and analysis, at 14,000 rpm, due to the large-scale peeling of the graphite ring block, there is a certain error in the results in the initial 5 min. After 5 min, the friction is relatively stable, and the curve shows a certain upward trend. The results are relatively reliable. In the initial stages at 12,000 rpm and 16,000 rpm, the differences are not significant. After 5 min, the curves continue to rise, and the ends of all three curves are within the range of approximately 0.27 to 0.33. During the stable stage of the curve after 10 min, the positional relationship of the three curves is as follows: the friction coefficient curve at 12,000 rpm is at the top, the one at 16,000 rpm is at the bottom, and the one at 14,000 rpm is in the middle. This indicates that the friction coefficient on the surface of the ring block decreased as the rotor speed increased, which followed the variation law of roughness with speed.

Figure 15.

Friction coefficient–time curves at different rotor speeds.

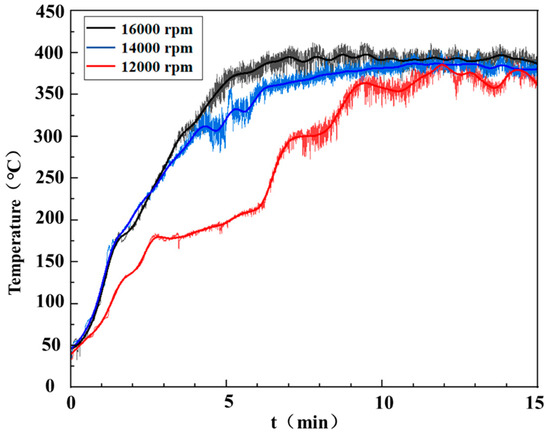

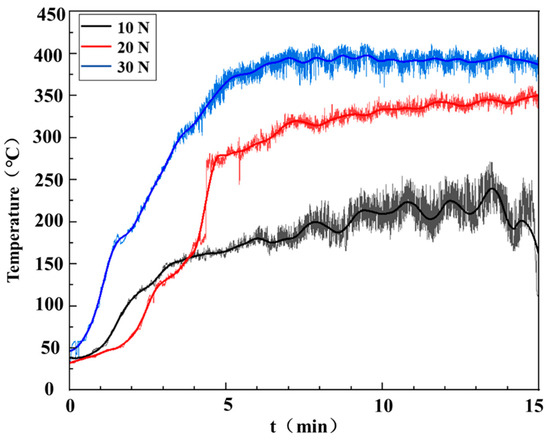

The temperature distribution at the test interface was obtained through a thermal infrared imager, the temperature changes were recorded, and the original data was exported for graphic analysis. Figure 16 shows the temperature–time curve of the ring-block surface in the high-speed ring-block friction and wear test of T482 graphite material under the same ambient temperature and loading force conditions, with only the metal ring speed (12,000 rpm, 14,000 rpm, 16,000 rpm) changed. Due to the heat absorption of the metal ring and the unstable factors in the surrounding environment, there are certain fluctuations in the temperature measurement. The overall trend of all the three curves is shown as “rapid heating after startup–slow heating–dynamic equilibrium”. The graphite ring block was rapidly heated to approximately 175 °C at 12,000 rpm, then went through a temperature slow rise zone of about 200 s to reach 200 °C, and finally continued to rapidly heat up to 370 °C. At 14,000 rpm and 16,000 rpm, the graphite ring block maintained rapid heating to reach equilibrium temperatures of approximately 380 °C and 390 °C, respectively. The slopes of the three curves are quite large from 0 to 2.5 min, and the noise around the fitting curves is relatively small. During this stage, the curves are characterized by strong frictional heat generation, reaching the equilibrium temperature in approximately 10 min, with low-frequency fluctuations superimposed above and below the equilibrium temperature. During the stable stage after 10 min of the curve, the positional relationship of the three curves is as follows: the temperature curve at 12,000 rpm is at the bottom, the temperature curve at 16,000 rpm is at the top, and the temperature curve at 14,000 rpm is in the middle. This indicates that the surface temperature of the ring block increased as the rotor speed increased. The higher the overall temperature of the material was, the greater the frictional work or surface thermal resistance per unit time was, and the slower the heat diffusion was.

Figure 16.

The surface temperature–time curves at different rotor speeds.

Figure 17 shows the surface temperature–time curve of the high-speed ring-block friction and wear test on T482 graphite material under the same ambient temperature and rotor speed conditions, with only the test loading force (10 N, 20 N, 30 N) changed. The overall trend of the three curves is “rapid heating–slow heating–dynamic equilibrium”, but there are differences in the equilibrium temperature, the time required to reach a stable temperature, and the amplitude of fluctuations. Under a loading force of 30 N, temperature rose to 400 °C in about 7 min and fluctuated up and down at the equilibrium temperature. The equilibrium temperature under a loading force of 20 N was approximately 330 °C. The equilibrium temperature under a loading force of 10 N was approximately 200 °C. During the stable stage after 10 min, the positional relationship of the three curves is as follows: the temperature curve under a 10 N loading force is at the bottom, the curve under a 30 N loading force is at the top, and the temperature curve under a 20 N loading force is in the middle. This indicates that the surface temperature of the ring block increased with the increase in the loading force.

Figure 17.

The surface temperature–time curves under different loading forces.

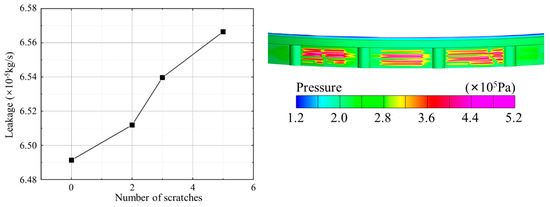

3.3. Detrimental Effects of Friction and Wear

The friction and wear of the main sealing surface can cause certain harm to the operation of the segmented annular seal. The friction and wear are severe, and the wear marks will increase. The scratches are approximately regarded as fine triangular grooves. According to simulation analysis, as shown in Figure 18, the fluid leakage will increase with the increase in wear marks, and the seal is more likely to fail. The unevenness of friction causes different wear marks on the main sealing surface. When the inlet pressure is 0.3 MPa, due to the squeezing effect of the scratch on the fluid, the local pressure reaches 0.5 MPa. The excessive fluid pressure intensifies the deformation of the ring disc under hydrodynamic pressure. Due to the different wear marks, the hydrodynamic pressure effect is uneven. The uniformity of deformation in each part of the graphite ring disc is also affected, thereby influencing the service life of the segmented annular seal.

Figure 18.

The condition of friction and scratches on the inner surface of the annulus.

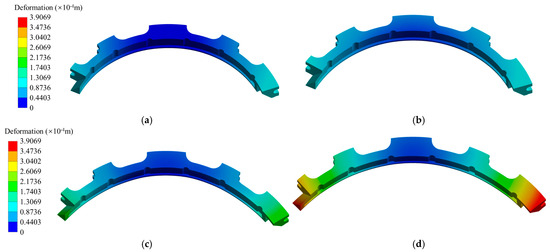

The frictional heat generated by the high-speed friction between the main sealing surface of the segmented annular seal and the rotor is one of the important factors affecting the service life of the seal. It can be known from the experiments that the temperature of the graphite ring block can reach nearly 400 °C after high-speed frictional heat generation. Therefore, it is necessary to study the thermal deformation characteristics of the ring disc before and after friction wear by introducing frictional heat. Assuming 14,000 rpm is the opening speed of this segmented annular seal, before opening, the friction coefficient was measured through experiments to calculate the frictional heat, and the thermo-solid coupling workflow was introduced to calculate the influence of the frictional heat on the deformation of the ring disc. After opening, the combined influence of hydrodynamic pressure and heat on the deformation of the ring flap was analyzed by the method of thermo-fluid–solid coupling. To make the sealing ring easier to open and the deformation more obvious, the circumferential spring force was set at 10 N. The deformation of the ring disc under the influence of frictional heat and hydrodynamic pressure is shown in Figure 19. As can be seen from Figure 19a,b, when no frictional heat is applied, the overall deformation of the ring disc is relatively small. Under the anti-rotation effect of the anti-rotation pin, the deformation in the middle of the ring disc is relatively small, and only the lap joint of the ring disc shows a slight warping. Under the influence of fluid pressure, the warping of the ring disc in Figure 19b is more severe than that in Figure 19a. After the application of frictional heat, the warping at the lap joint of the ring disc is severe. After the seal is opened, due to the combined effect of frictional heat and hydrodynamic pressure, the deformation of the ring disc intensifies, and its deformation is 0.13 mm higher than that of the ring disc only under the effect of frictional heat.

Figure 19.

The influence of frictional heat on the deformation of annulus discs: (a) Deformation of the segment during the seal running-in stage without frictional heat. (b) Deformation of the segment during the seal opening without frictional heat. (c) Deformation of the segment during the seal running-in stage with frictional heat. (d) Deformation of the segment during the seal opening with frictional heat.

3.4. Optimal Structural Design

To reduce or avoid the situation of increased leakage and severe deformation of the ring disc caused by high-speed friction, which leads to seal failure, a dynamic pressure segmented annular seal is usually adopted to replace the contact segmented annular seal. A dynamic pressure groove is opened on the main sealing surface to enhance the opening force, reduce the opening speed, improve the fluid lubrication performance, and at the same time ensure that the leakage is within the normal range to prevent seal failure. The dynamic pressure groove is optimized in design to further enhance the opening performance, reduce the friction loss of the ring disc, and extend the service life of the seal.

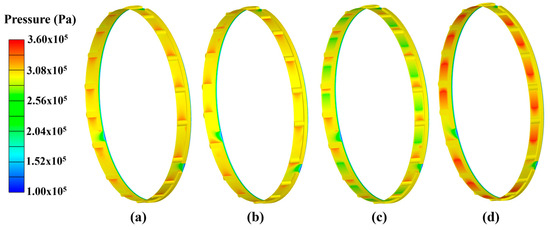

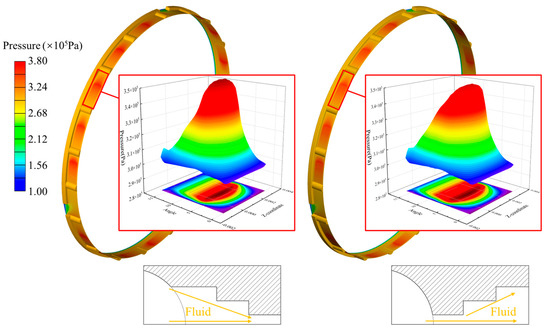

A comparative fluid analysis was carried out for the contact-type segmented floating ring seal and the hydrodynamic-type segmented floating ring seal, as shown in Figure 20. As can be seen from Figure 20c,d, the arrangement of hydrodynamic grooves significantly alters the pressure distribution. The tail sections of the grooves exert obstruction and extrusion effects on the fluid, resulting in distinct high-pressure zones. An analysis of the pressure field of the hydrodynamic-type segmented floating ring seal was conducted by changing the rotor rotation direction. When the opening direction of the hydrodynamic grooves is consistent with the rotor rotation direction (forward direction), the hydrodynamic effect of the grooves is enhanced and the opening force increases. In contrast, when the opening direction of the hydrodynamic grooves is opposite to the rotor rotation direction (reverse direction), the hydrodynamic effect is weakened, and the opening force is lower than that of the contact-type segmented floating ring seal.

Figure 20.

Comparison of pressure between contact and hydrodynamic segmented annular seals: (a) Reverse-direction contact segmented annular seal. (b) Forward-direction contact segmented annular seal. (c) Reverse-direction hydrodynamic segmented annular seal. (d) Forward-direction hydrodynamic segmented annular seal.

In terms of structural optimization, this paper proposes two design ideas: (1) changing the depth of the dynamic pressure groove along the radial direction, and (2) changing the width of the dynamic pressure groove along the axial direction.

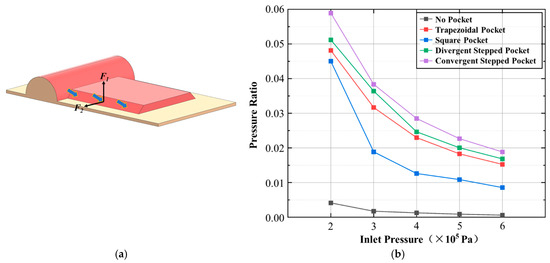

In the design direction of changing the depth of the dynamic pressure groove along the radial direction, a greater opening pressure can be obtained by setting up stepped grooves instead of square grooves, thereby improving the opening performance of the high-disc float ring. There are two types of step grooves: divergent and convergent. Both can change the fluid state by radially altering the gas film distribution, thereby altering the hydrodynamic pressure. As can be seen from Figure 21, the convergent step groove exerts a stepwise compression effect on the sealed fluid in the radial direction, increasing the local fluid density and enhancing the dynamic pressure effect. In contrast, the divergent step groove exerts a stepwise release effect on the fluid in the radial direction. Due to the expansion of the space inside the groove along the circumferential direction, the fluid flow rate decreases and the pressure rises. Due to the smaller fluid inlet of the divergent step groove, the amount of gas flowing in is lower, so the hydrodynamic pressure effect is weaker compared to the convergent step groove. However, the step structure of both has an auxiliary enhancing effect on the hydrodynamic pressure effect, and thus the opening pressure generated is higher than that of the square groove.

Figure 21.

The pressure distribution of the segmented annular seal with convergent and divergent step grooves.

The structure of the trapezoidal groove can also change the depth of the dynamic pressure groove along the radial direction, thereby altering the hydrodynamic pressure effect. As shown in Figure 22a, due to the trapezoidal inclined surface of the trapezoidal groove having a squeezing effect on the fluid in the dynamic pressure groove towards the middle, the reaction force exerted by the sealing fluid on the trapezoidal inclined surface has a radial component, F1. The trapezoidal groove enhances the hydrodynamic pressure effect along the radial direction, thereby increasing the opening pressure. To better analyze the data, specific pressure is introduced, which is the ratio of the opening pressure to the pressure difference between the inlet and outlet. As shown in Figure 22b, due to the increase in inlet pressure, the split pressure of each slot type gradually decreases, and the trend of decrease without slots is the smallest. The opening pressure provided by the trapezoidal groove is greater than that of the traditional square groove, with an average difference in specific pressure of 0.01. However, due to the depth of the dynamic pressure groove, the extrusion effect of the trapezoidal groove is relatively weaker compared to that of the step groove, and the generated pressure is smaller. The opening characteristics of the trapezoidal groove can be optimized by changing the slope on the side of the trapezoidal groove.

Figure 22.

Optimal design scheme for trapezoidal grooves: (a) Force analysis of trapezoidal grooves. (b) Comparison of specific pressures when the groove depth is radially changed.

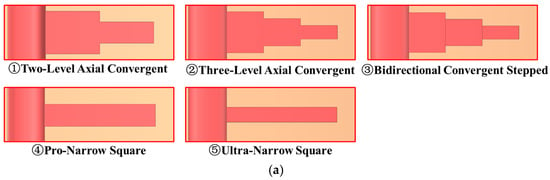

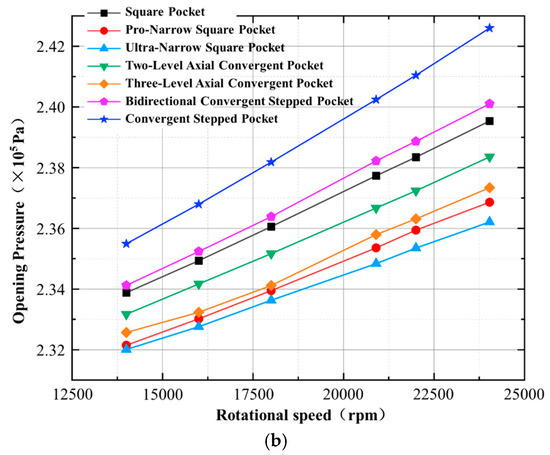

The hydrodynamic pressure on the surface of the gas film is changed by altering the width of the groove in the axial direction. Figure 23a shows the groove type design with the width of the dynamic pressure groove changed along the axial direction. The tail widths of the grooves ① and ④ are equal, and ② and ⑤ are also equal. ③ adds a convergent step groove design on the basis of ②. Figure 23b shows the variation law of the opening pressure of each groove type with the rotational speed. By comparing the axial converging groove type with the three square grooves, it can be seen that the axial converging groove type solves the problem of less fluid flow in the narrow square groove. However, compared with the traditional square grooves, the axial converging groove type provides a smaller opening pressure. Moreover, the hydrodynamic pressure effect produced by the secondary axial constricting is superior to that produced by the tertiary axial constricting. This is because the width of the dynamic pressure groove decreases, the amount of sealing fluid entering the dynamic pressure groove reduces, and the provided opening pressure relatively decreases. The axial constricting structure weakens the hydrodynamic pressure effect of the convergent step structure. The main reason for this is that the compression of the fluid by the axial constricting structure is mainly concentrated in the axial direction, and the reaction force generated by the fluid mainly acts in the axial direction of the sealing ring. The radial opening force produced by the compression is relatively small. When the axial constricting structure and the radial convergent structure coexist, due to the insufficient dynamic pressure groove space and less fluid, under this condition, the dynamic pressure effect is smaller than when only the convergent step structure exists. Therefore, for the structural optimization of dynamic pressure grooves, the focus should be on radial depth optimization, which results in better opening characteristics.

Figure 23.

The design concept of axially optimized groove type: (a) Several types of dynamic pressure grooves with axial changes in groove width. (b) The opening pressure of the axially optimized groove type varies with the rotational speed.

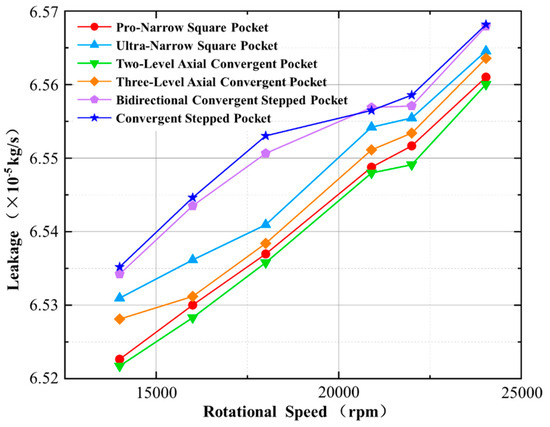

In response to the variation in leakage in various groove types, the leakage of segmented annular seal with various dynamic pressure grooves increases with the increase in rotational speed. Due to the increase in rotational speed, the opening pressure increases, the gas film gap becomes larger, and the leakage also increases. As can be seen from Figure 24, the leakage differences among the four slotting methods of the convergent groove and the narrow square groove are not significant. However, in general, the leakage of convergent groove types of the same class is less than that of the narrow square groove. The convergent structure has a certain role in reducing the leakage. Due to the larger opening force provided by the step groove, the leakage is relatively large. Therefore, combining the step groove with the convergent structure can reduce the leakage while ensuring a large opening force.

Figure 24.

The leakage of the axially optimized groove type varies with the rotational speed.

4. Conclusions

This paper focuses on a segmented annular seal made of T482 graphite material. Through the combination of experiments and the thermal–fluid–solid coupling model, the mechanism of high-speed friction and wear of graphite rings and the influence of high-speed friction and wear on the segmented annular seal are studied. In addition, based on the opening characteristics and leakage characteristics, optimization ideas for the segmented annular seal are proposed. The conclusions are as follows:

- The segmented annular seal is more prone to friction and wear during the running-in stage at low speeds, resulting in more wear marks. When the loading force increases, the wear rate of the graphite ring disc will rise, but when the rotational speed increases, the wear rate of the ring disc will decrease, and the change in wear rate caused by the change in rotational speed is more obvious. The variation patterns of roughness and friction coefficient are the same. Both roughness and friction coefficient will decrease as the loading force increases and increase as the rotational speed decreases. High-speed friction and wear generate a large amount of frictional heat, causing the temperature of the ring disc to increase with the increase in rotational speed and loading force.

- During the running-in stage before the opening of the segmented annular seal, high-speed friction and wear will cause scratches on the main sealing surface of the sealing ring disc, which in turn will lead to increased leakage and uneven deformation under force. The large amount of frictional heat generated by high-speed friction and wear will intensify the deformation of the segmented annular seal during operation, thereby causing the problem of seal failure.

- The performance of the segmented annular seal can be well optimized by opening the dynamic pressure groove along the axial direction. Further, by designing a new groove type and changing the depth of the dynamic pressure groove radially, the opening performance and leakage characteristics of the segmented annular seal can be better optimized, thereby extending the service life of the seal. However, changing the width of the dynamic pressure groove axially mainly optimizes the leakage characteristics of the seal. It has a poor effect on optimizing the opening characteristics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.H., H.W. and J.S.; Methodology, Z.H., H.W., S.Z. and B.L.; Validation, H.W.; Data curation, H.W.; Writing—original draft, H.W.; Writing—review and editing, Z.H., H.W., S.Z., J.S., N.L. and W.L.; Visualization, H.W.; Supervision, Z.H., J.S. and N.L.; Funding acquisition, Z.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Tianjin science and technology bureau science and technology program nature foundation (23JCYBJC00110), Basic research business fees of central universities-key project of natural science (3122025046), Chongqing natural science foundation (2024NSCQ-MSX1756), Chongqing education commission research project (KJQN202303007), Chongqing education commission research project (KJQN202403005), Tianjin education commission research project (2024KJ140).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely acknowledge the financial support mentioned above, which made it possible to conduct this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- NASA. Liquid Rocket Engine Turbopumps; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Burcham, R.E. High-Speed Cryogenic Self-Acting Shaft Seals for Liquid Rocket Turbopumps; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1983; NASA-CR-168194. [Google Scholar]

- Sorokina, N.E.; Redchitz, A.V.; Ionov, S.; Avdeev, V. Different Exfoliated Graphite as a Base of Sealing Materials. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2006, 67, 1202–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.Z.; Zhai, G.T.; Song, J.R.; Li, G.-S.; Shi, J.-L.; Guo, Q.-G.; Liu, L. Seal and wear properties of graphite from MCMBs/pitch-based carbon/phenolic-based carbon composites. Carbon 2006, 44, 2793–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baklanova, N.I.; Zima, T.M.; Boronin, A.; Kosheev, S.; Titov, A.; Isaeva, N.; Graschenkov, D.; Solntsev, S. Protective Ceramic Multilayer Coatings for Carbon Fibers. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2006, 201, 2313–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, G.P. Self-Acting Lift-Pad Geometry for Circumferential Seals-A Non-Contacting Concept; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1980; NASA TP1583. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.T.; Li, X.J.; Hu, G.Y.; Hu, T.Q.; Sun, Z.L. High-temperature friction and wear behavior and prediction of Graphite Sealing materials. J. Aerosp. Power 2014, 29, 314–320. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, R.M.; Zhao, X.; Li, S.X.; Yang, H. Floating ring seal leakage characteristics of high-speed gas ring valve type of experimental study. J. Fan Technol. 2020, 62, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.X.; Li, S.X.; Ma, W.J.; Feng, R.P.; Liu, Z.W. Frictional heat analysis of Ring Disc Floating Ring Seal in Bearing Cavity. J. Mech. Electr. Eng. 2020, 37, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.Z.; Li, S.X.; Zheng, R.; Ma, W.; Zhuang, S. Sensitive parameters Affecting the Sealing Performance of Three-lobe High-Speed floating ring. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 2020, 46, 571–578. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, J.Y.; Liu, D.; Zhang, R.; Ren, G. Circular graphite seal friction and wear performance test. J. Aircr. Engine 2025, 51, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Hady, W.F.; Ludwig, L.P. New Circumferential Seal Design Concept Using Self-Acting Lift Geometries; National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.N. Multi-Physical Field Coupling Analysis and Optimization Design of High Linear Velocity Graphite Seals. Master’s Thesis, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Research on Fluid-Solid-Thermal Multi-Field Coupling Analysis of Graphite Circular Seals in Aero Engines. Master’s Thesis, Xidian University, Xi’an, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, R.D.; Chen, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.Y. Circumferential spring force distribution on circular seal sealing performance influence. J. Propuls. Technol. 2021, 42, 1361–1371. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.S. Thermal-Structural Analysis of Circumferential Sealing Rings in Aero-Engines. Master’s Thesis, Northeastern University, Shenyang, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Arghir, M.; Mariot, A. Theoretical Analysis of the Static Characteristics of the Carbon Segmented Seal. J. Tribol.-Trans. Asme 2017, 139, 062202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourt, E.; Arghir, M. Experimental Analysis of the Leakage Characteristics of Three Types of Annular Segmented Seals. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2023, 145, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessio, P.; Lou, D. Development of High Misalignment Carbon Seals. In Proceedings of the 37th Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 8–11 July 2001; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Oike, M.; Nagao, R. Characteristics of a Shaft Seal System for the LE-7 Liquid Oxygen Turbopump. In Proceedings of the 31st Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit, San Diego, CA, USA, 10–12 July 1995; pp. 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.G. Turbulence; Tianjin University Press: Tianjin, China, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, H.; Li, F.C. Numerical Calculation of the Influence of Fluid-Structure Interaction on Propeller Strength. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. 2015, 39, 144–147+152. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.T.; Zhang, B.; Hu, G.; Zhao, Z. Thermal-Structural Coupling Analysis of Circumferential Graphite Seals. J. Aerosp. Power 2018, 33, 273–281. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, L. Numerical Simulation of Fluid-Solid Coupling for Composite Hydrofoils. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.Y.; Ma, Y.M.; Ding, W.; Zou, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, G.; Tao, S.; Zhang, Z. Analysis of thermal-fluid-solid coupling at the interface of mechanical seal friction pairs. Mech. Des. Manuf. Eng. 2017, 46, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hokao, M.; Hironaka, S.; Suda, Y.; Yamamoto, Y. Friction and wear properties of graphite-glassy carbon composites. Wear 2000, 237, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.