Abstract

The prediction of tribological behavior in engineering systems based on output data streams is often considered empirical, as it is difficult to fully describe the underlying processes using closed-form mathematical models. For instance, accurately predicting the coefficient of friction (COF) across the three major lubrication regimes using a single model remains elusive. Machine learning (ML) offers a powerful data-driven approach for modeling complex tribological processes by learning nonlinear relationships between operating conditions and performance metrics. This work develops a high-accuracy deep learning model for predicting the COF in lubricated tribosystems across boundary, mixed, and hydrodynamic lubrication regimes. Extensive experimental data were collected using a ball-on-disk tribometer, which generated a large and diverse dataset spanning multiple materials, lubricants, temperatures, loads, and sliding speeds and covered the full Stribeck curve. These data were then used to train and optimize a neural network capable of accurately reproducing frictional transitions across lubrication regimes. The breadth of the dataset not only allows for the full Stribeck behavior to be captured, but also enables generalization across distinct tribosystems. The resulting model demonstrates strong predictive performance and is deployed using a graphical user interface as a practical tool for estimating COF in ball-on-disk lubricated sliding contacts.

1. Introduction

Tribology, the study of friction, lubrication, and wear, remains a cornerstone of modern engineering systems. Frictional losses account for nearly one-third of global energy consumption [1], underscoring the urgent need to understand and control tribological behavior to enhance energy efficiency and reliability. Tribology continues to be largely empirical [2], as it is often difficult to fully describe the multiscale and nonlinear mechanisms governing friction and lubrication using closed-form analytical models. In this context, modern artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) techniques offer powerful tools for modeling complex, multivariate systems where parameters interact nonlinearly. These methods can uncover hidden correlations, optimize system design, and enable predictive capabilities within intelligent and adaptive tribological systems, such as digital twins. Yet, the integration of ML in tribology remains comparatively underexplored relative to other disciplines [3].

Modeling the complex interdependence among all interacting features in a lubricated contact is a significant challenge. In such cases, data-driven models offer a powerful approach to learn these relationships directly from experimental data [4,5], without relying on explicit physical equations [6,7,8,9,10]. Recent studies have demonstrated the potential of ML for predicting the coefficient of friction (COF) in specific tribological contexts. Wu et al. (2025) developed an SSA-XGBoost model to predict the COF of wet friction components using data from disk-on-disk tests of copper–steel tribopairs lubricated with RP-4652D transmission oil [10]. Bucholz et al. (2012) applied data-driven informatics to estimate COF for ceramic materials, relying on datasets of intrinsic material properties [11]. Sattari Baboukani et al. (2020) used Bayesian and transfer learning to predict nanoscale frictional behavior in two-dimensional (2D) materials [12], and Barik and Woods (2024) expanded this effort by modeling frictional properties of 2D materials using high-throughput computational data [13]. Cherguy et al. (2025) trained deep learning models on the literature-derived data to predict dry friction in DLC coatings [14]. Kumar et al. (2024) developed regression and ANN models to predict frictional behavior of metal-matrix composites under lubrication with SAE20W40 oil [15]. Gutiérrez et al. (2024) correlated acoustic emission (AE) signals with friction in steel–steel sliding contacts using ML algorithms, demonstrating the feasibility of AE-based friction prediction under dry conditions [16]. Expanding on this line of work, Yang et al. (2025) used a similar AE-based ML strategy, processing HFRR acoustic emission data with STFT/STHG and training GA and PSO optimized ANN models, to model Stribeck behavior [17].

While these works demonstrate the growing interest in data-driven tribology, they share common limitations: most address restricted operating ranges, rely on a single tribo-pair or lubricant, focus on dry or single-regime conditions, or employ narrow datasets that cannot capture the full transition between boundary, mixed, and hydrodynamic lubrication, let alone represent this behavior across different tribosystems. As a consequence, existing data-driven models are generally unable to learn the continuous, multi-regime frictional transitions that define the Stribeck curve within a single unified framework. The present study addresses these limitations by introducing a deep-learning-based unified framework capable of predicting the Stribeck curve across boundary, mixed, and hydrodynamic regimes. A distinguishing feature of this work is the underlying experimental dataset, which was explicitly designed to capture full multi-regime Stribeck behavior rather than isolated lubrication conditions. The model was trained on a large and diverse, experimentally generated dataset obtained from controlled ball-on-disk tribometer tests spanning a wide range of speeds and loads to ensure comprehensive coverage of lubrication regimes. The dataset further includes multiple temperature–material–lubricant combinations and spans Stribeck numbers from to , enabling experimental representation of boundary, mixed, and hydrodynamic lubrication regimes across distinct tribosystems within a single dataset. This study incorporates a comprehensive set of input features, including thermophysical lubricant properties, material characteristics, and operating conditions. The scale, diversity, and regime completeness of the dataset enable the development of a deep neural network that accurately captures continuous transitions among lubrication regimes and generalizes across distinct tribosystems, representing a substantive advance toward generalized, data-driven modeling of lubricated friction.

Finally, to ensure usability, a graphical user interface (GUI) was developed, enabling users to input lubricant, material, and operating parameters and instantly obtain predicted COF values. This GUI is powered by the trained neural network, making the framework accessible for both research and industrial applications. Beyond its predictive capability, this work establishes a foundation for data-driven digital twins of lubricated tribosystems, enabling real-time optimization and autonomous control of tribological performance.

Challenges in Modeling and Experimentally Characterizing the Stribeck Curve

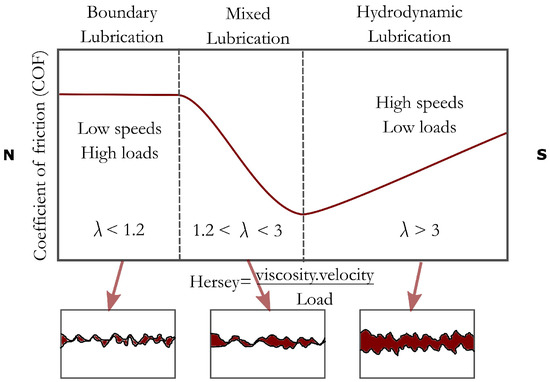

The Stribeck curve (Figure 1) is a cornerstone of tribology, describing the nonlinear relationship between the coefficient of friction (COF) and operating parameters such as sliding speed (V), load (), and lubricant viscosity (). Since the pioneering work of Richard Stribeck (1902) [18] and the dimensionless formulation proposed by Gumbel (1914) [19], this curve has served as a fundamental tool to visualize the transitions between boundary, mixed, and hydrodynamic lubrication regimes [20].

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the Stribeck curve illustrating the characteristic variation of the coefficient of friction with operating conditions and the transitions between boundary, mixed, and hydrodynamic lubrication regimes.

The Stribeck curve remains difficult to reproduce and model comprehensively. Each lubrication regime is governed by distinct physical laws:

- Boundary lubrication:Involves solid–solid contact dominated by asperity interactions and adhesion, requiring a solid mechanics framework.

- Mixed lubrication: Demands a fully coupled solid–fluid formulation, as load sharing occurs between asperities and a thin fluid film.

- Hydrodynamic lubrication: Is primarily fluid-mechanical and described by the Reynolds equation, where surfaces are completely separated by a viscous film.

In practice, the transition between lubrication regimes occurs naturally and continuously as operating conditions change. However, theoretical modeling treats these regimes separately, since each is governed by distinct physical principles and constitutive equations. As a result, most analytical formulations describe only one regime at a time, making it difficult to develop a unified model that captures the entire Stribeck behavior—a long-standing challenge in lubrication theory [20].

Experimentally, generating high-quality Stribeck data is equally demanding. Stable regime transitions require precise control of velocity and load ramps; small deviations can shift the contact into a different lubrication state, altering the frictional response [2,21]. Temperature control is critical because viscosity—and therefore friction—is highly temperature-sensitive; maintaining isothermal conditions during high-speed or prolonged tests is technically challenging [22,23]. Furthermore, tribological performance depends strongly on surface roughness, hardness, and cleanliness; small inconsistencies in polishing or preparation can cause significant data scatter [21,24]. Capturing frictional transitions, especially within the boundary and mixed regimes, requires high-resolution, low-noise sensors to minimize instrumental error [25,26]. Finally, comprehensive coverage of the Stribeck curve involves numerous test permutations across load, speed, and temperature, leading to long experimental campaigns and potential sample degradation [21,23]. Prior studies have underscored this experimental rigor: Czichos et al. [2] and Bhushan [21] emphasized the need for precise control of entrainment speed and pressure, while Johnson [22] and Stachowiak & Batchelor [23] highlighted thermomechanical effects that can obscure regime boundaries. These complexities demonstrate that both analytical and experimental approaches face significant limitations in capturing the complete Stribeck behavior.

Recent developments in machine learning have introduced new opportunities to model tribological systems directly from data [4,27,28]. While previous studies have successfully applied neural networks to predict wear [29], composite frictional behavior [30], and lubricant formulation effects [8,31,32], no existing work has attempted to reproduce the full Stribeck curve. The present study addresses this gap by developing a data-driven neural network framework to predict frictional behavior across all lubrication regimes using experimental data, thereby complementing the limitations of purely physics-based models.

2. Data Collection

The accurate experimental generation of Stribeck curves poses significant experimental challenges, as the coefficient of friction is a complex function of several interdependent variables, all of which must be precisely controlled and monitored. In this study, a robust data collection protocol was developed to enable the construction of a comprehensive data set suitable for training a data-driven machine learning model.

This section outlines the experimental methodology used to generate the Stribeck curves, emphasizing the rigor applied to achieve reproducibility and regime resolution across tests. To systematically capture the key physical parameters affecting tribological behavior, the input parameters are categorized into three main groups: (1) lubricant properties, (2) operating conditions, and (3) contact properties. Each of these categories is discussed in detail, with representative examples that illustrate how their variation influences the behavior of the Stribeck curve.

2.1. Stribeck Tests

In this study, a systematic experimental protocol was implemented to generate reliable Stribeck curves through carefully varied permutations of velocity and load. Significant effort was dedicated to tuning these parameters via iterative trial-and-error procedures. Several preliminary runs were required to fine-tune the velocity and load such that the transitions between boundary, mixed, and hydrodynamic lubrication regimes were clearly distinguishable and reproducible across different tests.

To ensure data quality and thermal stability, test durations were carefully calibrated—particularly during high-speed runs where frictional heating can rapidly alter the lubricant’s viscosity. Each experiment was only initiated once the lubricant bath temperature reached the desired setpoint, and all tests were conducted under quasi-isothermal conditions to minimize thermal drift.

To preserve the integrity and repeatability of surface conditions, a fresh steel ball and a new flat sample were used for each Stribeck curve. Prior to testing, both the ball and disk were subjected to a standardized cleaning procedure involving sequential rinses with acetone and heptane, followed by air drying in a clean environment. This protocol minimized surface contamination and ensured consistent tribological interfaces across experiments. Additionally, fresh lubricant was used for every test, and the lubricant reservoir was thoroughly flushed and refilled to eliminate the influence of degradation or cross-contamination from previous runs.

2.1.1. Lubricant Properties

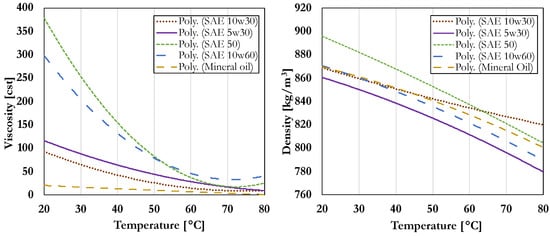

The lubricant properties considered in this study include viscosity (), density (), viscosity index (VI), and pressure–viscosity coefficient (). Viscosity measurements were conducted using an Ares G2 Rheometer in a parallel-plate configuration, with temperature (T) as the independent variable. Each sample was assessed across a temperature range from ambient conditions to 80 °C. Polynomial regression was employed to empirically model the relationship between viscosity and temperature for each lubricant (Figure 2, left).

Figure 2.

Polynomial regression curves illustrating the temperature dependence of lubricant properties. (Left): Viscosity () as a function of temperature (T). (Right): Density () as a function of temperature (T).

Density values were obtained from the manufacturers’ technical data sheets, which report experimentally measured properties for each lubricant. Polynomial regression was then applied to model the density–temperature behavior (Figure 2, right). Similarly, viscosity index and pressure–viscosity coefficient values were extracted from the corresponding technical data sheets. Table 1 summarizes the lubricants and their associated properties.

Table 1.

Summary of the physical properties and empirical temperature-dependent models of the lubricants evaluated in this study.

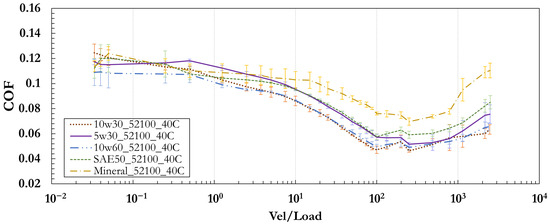

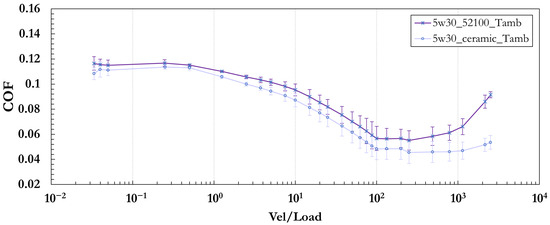

Figure 3 portrays the influence of different lubricants on the Stribeck curve. These curves were obtained from pin-on-disk tribometer experiments conducted at 40 °C using a 52100 Chrome steel ball. Each point in the Stribeck curves represents the mean of four independent repetitions. The error bars correspond to one standard error of the mean, which quantifies the precision of the averaged values rather than the full variability of individual measurements. Consequently, the standard errors shown here are smaller than the total measurement scatter (standard deviation). This distinction is important, as the larger experimental variability quantified by the standard deviation is used later in the definition of the Bayes error applied to model evaluation.

Figure 3.

Effect of lubricant over Stribeck curve tested at the same operating conditions.All curves shown in this plot were obtained experimentally at 40 °C using 52100 chrome steel balls to isolate the influence of lubricant type on frictional behavior.

2.1.2. Operating Conditions

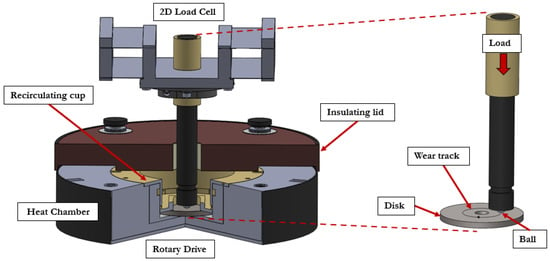

The test-rig used is an Rtec MFT-5000 multi-function tribometer (Rtec Instruments Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). equipped with a series of sensors and controllers enabling the accurate setting of operating conditions and precise reporting of the results in a wide operation range. The operating range of the testing parameters is as follows:

- Average angular speed of the ball-on-disk contact (): 1–2750 [rpm].

- Lubricant bath temperature (): –80 [°C].

- Contact load (): 1–30 [N].

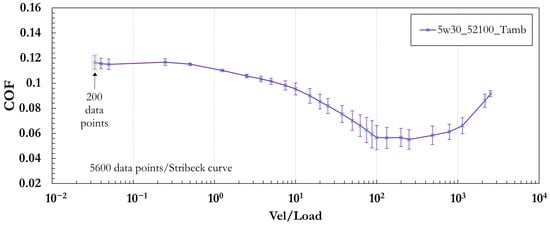

Table 2 summarizes the range of operating conditions used. The full test matrix was repeated for four lubricant bath temperatures: ambient (), 40 °C, 60 °C, and 80 °C. Figure 4 illustrates a representative Stribeck curve generated using 5W30 lubricating oil at ambient temperature, with a 52100 chrome steel ball serving as the tribological counterpart.

Table 2.

Operating conditions used for Stribeck curve generation at each test temperature (, 40 °C, 60 °C, and 80 °C). Each Stribeck curve is obtained from 28 unique speed–load combinations, repeated four times per temperature to ensure reproducibility. The speed-to-load ratio is used as the dimensionless parameter on the x-axis of the Stribeck curve.

Figure 4.

Experimentally measured Stribeck curve for SAE 5W-30 oil at ambient temperature using 52100 chrome steel balls. The coefficient of friction was measured across 28 speed–load combinations, with 200 data points collected per condition from four repeated tests (totaling 5600 data points). Error bars represent one standard error (n = 200) for each operating condition.

2.1.3. Contact Properties

Direct contact occurs between the ball and the disk, which serve as the primary counterbodies within the tribosystem, fully immersed in the selected lubricant. Figure 5 provides a detailed view of the ball-on-disk configuration used in this study. The ball is pressed against the rotating disk, generating a wear track. While the disk material, 52100 Chrome Steel G25, is kept constant throughout all experiments, the ball material is systematically varied to investigate its influence on the COF.

Figure 5.

Detailed schematic of the ball-on-disk tribo-pair configuration used in this study.

Three distinct ball materials are employed to assess the impact of contact properties on the Stribeck behavior of the lubricated tribosystem. Key material properties—including Poisson’s ratio (), Young’s modulus (E), hardness (HR), and surface roughness ()—are considered and summarized in Table 3. These properties significantly influence interfacial contact mechanics, leading to variations in the frictional response captured by the Stribeck curve. Figure 6 presents Stribeck curves obtained under ambient temperature conditions using 5W30 oil. One curve corresponds to tests conducted with a 52100 chrome steel ball, while the other illustrates the response with a silicon nitride ball. The observed differences in Stribeck behavior are directly attributable to the variations in ball material, highlighting the critical role of contact properties in influencing tribological performance.

Table 3.

Contact and material properties of the ball and disk specimens used in this study.

Figure 6.

Effect of ball material on the Stribeck curve of SAE 5W-30 oil measured at ambient temperature. The curves compare tests performed with 52100 chrome steel and silicon nitride balls, showing the influence of contact material on frictional behavior across lubrication regimes.

However, it is interesting to note that the curves show relatively similar trends in the boundary and mixed lubrication regimes, where direct asperity contact plays a dominant role, and a more pronounced difference is observed in the hydrodynamic regime, where a full fluid film separates the surfaces. This observation suggests that factors beyond classical contact mechanics may influence performance at higher speeds. Potential contributors include differences in elastic modulus (E), which can affect the formation and stability of the lubricant film and the load-carrying capacity of the contact [33,34]. Surface energy variations may also influence lubricant spreading and wetting behavior [35,36]. Additionally, the silicon nitride ball exhibits a significantly lower surface roughness ( µm) compared to the chrome steel ball ( µm), which may lead to differences in film thickness development and interfacial shear behavior in the hydrodynamic regime [21,37]. These findings highlight the complex interplay between material and surface characteristics in defining tribological behavior across lubrication regimes.

2.1.4. Family of Stribeck Curves

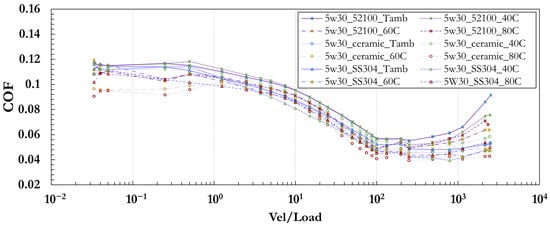

A comprehensive family of Stribeck curves was collected for each lubricant during the data collection phase. Figure 7 illustrates the variations in Stribeck behavior observed for 5W30 oil using different ball materials and testing temperatures.

Figure 7.

Family of Stribeck curves for SAE 5W-30 oil illustrating the effect of ball material (52100 chrome steel, silicon nitride, and 304 stainless steel) and lubricant bath temperature (, 40 °C, 60 °C, and 80 °C) on tribological performance. Each curve represents a unique material–temperature combination. Similar color tones are used intentionally to emphasize that all curves correspond to the same lubricant, while variations in line and markers style distinguish the different test conditions.

A comprehensive family of Stribeck curves was collected for each lubricant during the data collection phase. Figure 7 illustrates the variations in Stribeck behavior observed for 5W30 oil across different combinations of ball materials and lubricant bath temperatures (). Specifically, the curves represent tests conducted using three different ball materials—52100 chrome steel, silicon nitride, and 304 stainless steel—at four lubricant bath temperatures: ambient (), 40 °C, 60 °C, and 80 °C. Each curve in the figure corresponds to one unique combination of ball material and temperature, resulting in a total of twelve Stribeck curves for the 5W30 oil.

3. Data-Driven Modeling

3.1. Data Matrix

Each training instance corresponds to a single COF measurement taken at a specific speed/load condition during a Stribeck test. For each test, 50 COF values are recorded per speed/load step, with 28 steps in total, yielding approximately 1400 data points per test. Each test is repeated four times to enable statistical averaging, resulting in 5600 training instances per Stribeck curve. In total, 60 unique Stribeck curves are collected across five lubricants, three ball materials, and four lubricant bath temperatures (), leading to a combined dataset of 336,000 training instances. Each instance includes features: fifteen input features () describing the lubricant properties, operating conditions, and the bulk and surface properties of the ball and disk, and one output feature corresponding to the measured COF. Table 4 presents an example of a single training instance.

Table 4.

Example of a single machine learning training instance showing the input parameters and corresponding output used for model training.

Let denote the input data matrix, where 336,000 is the number of training examples, and is the number of input features. The corresponding output vector, , contains the target values, i.e., the measured COF for each instance.

Each row of in Equation (1) corresponds to one experimental configuration, composed of lubricant, operational, and material properties. Equation (2) represents the vector of observed output values, where is the measured COF for the ith instance.

The neural network is trained to learn a function , parameterized by weights , such that accurately predicts the COF for a given input vector . All input features were standardized before training to ensure numerical stability and consistent feature scaling.

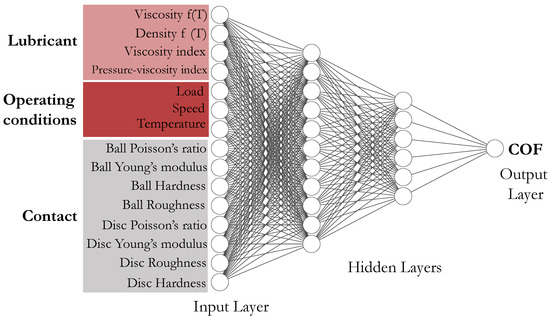

3.2. NN Architecture

A Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) deep learning model is trained to process input variables and predict the COF based on the tribosystem features. An MLP is a type of feedforward artificial neural network consisting of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer, with each layer comprising fully interconnected neurons. Figure 8 illustrates the general architecture of the current tribosystem’s NN. Although a single hidden layer is often sufficient for many problems, the complex, nonlinear behavior of COF necessitates the use of at least two or three hidden layers to capture intricate patterns in the data.

Figure 8.

Neural network (NN) architecture used for the prediction of the coefficient of friction (COF) in lubricated ball-on-disk tribo-pairs. The model includes multiple hidden layers to capture the complex nonlinear relationships governing frictional behavior.

3.3. Model Training

To ensure statistical independence and prevent data leakage, the dataset—comprising approximately 336,000 input–output instances collected from tribological experiments under various lubricants, materials, and operating conditions—was divided into three subsets: training, validation (development), and testing, following a 60–20–20 split. Each subset corresponds to distinct lubricants and, therefore, independent tribosystems rather than a random partition of a single dataset. Specifically, the model was trained using data from SAE 5W-30, SAE 50, and Mineral Oil; validated on SAE 10W-30; and tested on SAE 10W-60. Each subset includes multiple material–lubricant combinations and temperature conditions, ensuring that the testing data remained completely unseen during training and allowing for the model to learn both lubricant- and material-dependent effects.

Model training was designed to minimize bias and variance through an iterative optimization process. The model’s initial performance on the training data was assessed for bias—defined as the error arising from the model’s inability to capture the underlying nonlinear relationships within the data. High bias, indicative of underfitting, was mitigated by increasing the network’s complexity (e.g., additional hidden layers or neurons) or extending the training duration. Once bias was minimized, the validation dataset was used to evaluate variance. High variance, associated with overfitting, was detected when model performance diverged between training and validation datasets. To address this, regularization techniques (e.g., L2 penalties) and early stopping were applied until training and validation losses converged to comparable levels.

The hyperparameters—including the number of hidden layers, number of neurons per layer, learning rate, and regularization strength ()—were optimized through a systematic grid search. This procedure ensured that the selected model architecture achieved an optimal balance between expressiveness and generalization capability. The convergence of training and validation losses was continuously monitored to detect any onset of overfitting; divergence triggered early stopping or additional regularization.

After convergence, the model was evaluated on the completely unseen testing dataset (SAE 10w-60). The primary performance metric was the coefficient of determination (). An value above 90% was considered satisfactory, as this threshold corresponds to the estimated Bayes error derived from the experimental standard deviation. The Bayes error represents the minimum achievable uncertainty imposed by the inherent variability of tribological measurements. It was calculated from the standard deviation of repeated tests, which captures the overall experimental variability or irreducible noise level. This differs from the standard errors shown as error bars in the Stribeck curves, which indicate only the precision of the mean. Defining the Bayes error using the standard deviation ensures that model performance is evaluated against the true experimental noise floor rather than the statistical precision of averaged data.

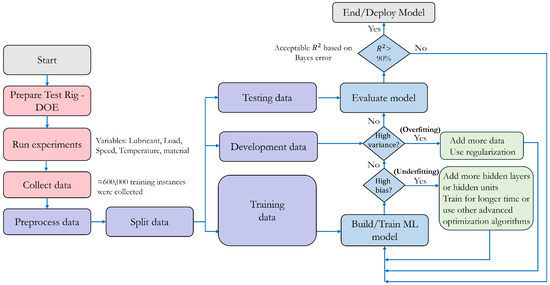

The methodology for building, training, and deploying the machine learning model is summarized in the diagram in Figure 9. This workflow systematically guides the deployment of a data-driven model for tribological studies, ensuring robust evaluation at each stage to deliver a reliable and accurate predictive tool for understanding and optimizing tribological behavior.

Figure 9.

Workflow illustrating the systematic process used for developing the data-driven machine learning (ML) model, including data preprocessing, model training, validation, and deployment. Each stage incorporates evaluation steps to ensure a robust and accurate predictive framework for tribological analysis.

The NN was trained using an optimized multilayer perceptron (MLP) architecture implemented in Python 3.6.13 using the scikit-learn library [38]. The architecture consists of three hidden layers with 100, 50, and 25 neurons, respectively. These values were selected through a systematic grid search that optimized the number of layers, neurons per layer, learning rate, and regularization strength () based on minimum validation loss and convergence stability. The rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function introduces nonlinearity, enabling the model to capture complex patterns within the input data. To control model complexity and mitigate overfitting, L2 regularization (Ridge penalty) was applied with a strength parameter . Training was performed for up to 400 epochs using Adam optimizer [39], which combines the advantages of the Adaptive Gradient Algorithm (AdaGrad) and Root Mean Square Propagation (RMSProp). These design choices, informed by grid search optimization, enabled the MLP to effectively learn intricate relationships within the dataset and enhance prediction accuracy for frictional behavior.

4. Results and Discussion-Model Deployment

A critical stage in the development of AI/ML predictive frameworks is the deployment phase, where the trained model is applied to generate predictions for new, unseen data—a process referred to as inference. During this stage, the model uses the relationships learned during training to infer outcomes from novel inputs while its generalization capability is quantitatively assessed. To confirm that the model does not overfit the training data, its predictive accuracy was evaluated on both training and testing subsets that represent independent tribosystems. The model achieved a coefficient of determination () for both training and testing datasets. This close agreement indicates that the model generalizes well across different lubrication systems rather than memorizing specific data trends. Moreover, the achieved exceeds the Bayesian error threshold derived from experimental uncertainty, confirming that the model captures the dominant physical relationships governing frictional behavior with accuracy comparable to experimental reproducibility. These results demonstrate a balanced learning process and validate the model’s robustness for deployment. Nevertheless, as a data-driven framework, the model’s predictive accuracy remains bounded by the range of the training data; reliable performance can be expected for lubricants, materials, and operating conditions whose properties fall within the envelope represented in this study.

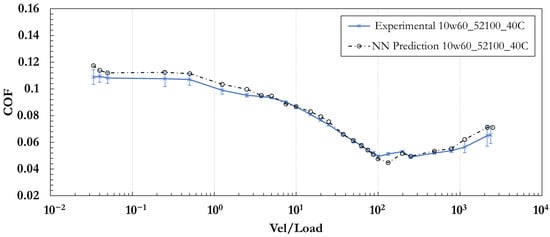

The trained model is subsequently used to predict the COF across the entire Stribeck curve for SAE 10W60 oil—an entirely unseen lubricant excluded from the training and validation datasets. This test represents a stringent assessment of extrapolation capability, as it requires the model to transfer learned relationships to a new lubricant–material combination. Figure 10 compares the predicted and experimental Stribeck curves for SAE 10W-60 at 40 °C using a 52100 chrome steel ball. To quantitatively assess the discrepancy between predicted and measured values, we report a mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.0048, a root-mean-square error (RMSE) of 0.0075, and a mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of 7.6%. All three global metrics lie below the Bayes-error threshold (10%), confirming that the deviations fall within the inherent experimental noise of the tribological measurements. The predicted curve successfully reproduces the characteristic evolution of friction across the boundary, mixed, and hydrodynamic regimes, demonstrating that the model can accurately infer frictional behavior across distinct tribosystems. Minor deviations near regime transition zones are attributed to experimental variability and differences in film formation dynamics, which fall within the expected measurement uncertainty. Overall, the agreement between predictions and experiments confirms the model’s capacity to generalize beyond the training data and reliably predict tribological responses under new operating conditions.

Figure 10.

Experimental and NN-predicted Stribeck curves of SAE 10W-60 at 40 °C using a 52100 chrome steel ball. SAE 10W-60 was unseen during training, demonstrating the model’s generalization capability. For this case, the MAE, RMSE, MAPE, and between predicted and experimental COF values are 0.0028, 0.0036, 3.7%, and 0.97, respectively.

To further assess the model’s interpretability, a permutation feature importance analysis was conducted to quantify the relative contribution of each input variable to the predicted COF. This method estimates the average decrease in model performance () when each feature is randomly permuted, indicating its relative influence on the model’s predictions. The resulting hierarchy of importance (Table 5) identifies sliding speed as the dominant factor governing friction, followed by ball roughness, load, and ball hardness. This ranking aligns with Stribeck theory, where entrainment velocity drives transitions between boundary, mixed, and hydrodynamic lubrication regimes, while surface and material properties control asperity deformation and the real area of contact. Viscosity and temperature are next, showing a coupled influence through their combined effect on film thickness and viscous shear, whereas disk-related properties show negligible importance since the disk material was constant across all experiments.

Table 5.

Ranked feature importance derived from permutation analysis, showing the mean reduction in model performance () when each variable is randomly permuted. Values are normalized with respect to the most influential feature (speed = 100%).

This behavior contrasts with conventional Stribeck curve analyses, which typically examine variations within a single lubricant–material pair and emphasize viscosity, load, and speed as the dominant parameters. In contrast, the present data-driven framework generalizes across multiple tribosystems—each defined by different combinations of lubricants and materials. Consequently, the model captures not only the influence of lubricant properties and operating conditions but also the material-specific effects that modulate frictional response and regime transitions. Overall, these findings confirm that the model encapsulates physically meaningful dependencies among operating conditions, material characteristics, and lubricant properties, representing an initial step toward a more integrated and interpretable description of lubricated friction across different tribosystems.

4.1. Evaluation of Gradient Boosting

To complement the neural network (NN) analysis and explore alternative modeling strategies, a Gradient Boosting (GB) model was implemented. The configuration included 400 estimators, a learning rate of 0.1, and the least squares loss function. Gradient Boosting is an ensemble method that builds additive models in a forward stage-wise manner, combining multiple shallow decision trees to minimize prediction errors sequentially [40].

The GB model achieved for the testing data set, slightly outperforming the MLP NN, which reached for the testing data set. This result aligns with the well-documented strength of tree-based ensemble methods in handling structured, tabular datasets. Gradient Boosting is particularly effective in capturing non-linear relationships and feature interactions with relatively low preprocessing requirements, which can be advantageous when working with moderate-sized datasets.

Neural networks, by contrast, tend to require larger datasets and more careful tuning of hyperparameters— such as the number of layers, neurons per layer, activation functions, and learning rates—to generalize well. Their training process can be more sensitive to initialization and prone to overfitting if not adequately regularized. The slightly lower observed for the MLP in this study may reflect these factors rather than a limitation in its representational capacity.

Despite Gradient Boosting’s stronger performance in this specific context, neural networks remain a relevant modeling choice for tribological applications. Their architecture can be adapted for use with high-dimensional, time-series, or sensor-based inputs, which are common in real-world tribology systems. Moreover, NNs offer flexibility for incorporating additional domain knowledge, such as physics-informed constraints, which can enhance generalization in data-scarce or extrapolative scenarios.

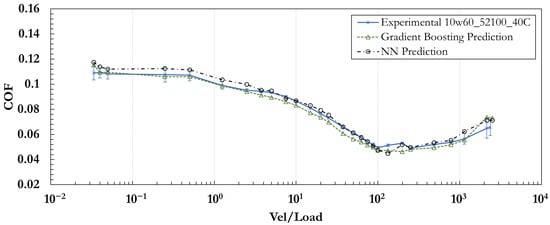

In summary, both Gradient Boosting and neural networks demonstrated strong predictive performance on the task of COF estimation. While Gradient Boosting yielded a higher test , neural networks provide a flexible foundation for extending this work to more complex data modalities and modeling tasks. The selection of one approach over the other should depend on the nature of the dataset, the modeling goals, and the potential for future integration with more advanced or dynamic input sources. Figure 11 compares the experimental results with the predictions from both the MLP NN and Gradient Boosting models, demonstrating strong agreement and confirming the reliability of both approaches.

Figure 11.

Comparison of experimental and predicted Stribeck curves for SAE 10W-60 at 40 °C using a 52100 chrome steel ball. Predictions were generated using MLP NN and Gradient Boosting models, both exhibiting strong agreement with experimental data. For the Gradient Boosting model, the MAE, RMSE, MAPE, and are 0.0032, 0.0039, 4.7%, and 0.97, respectively.

4.2. A Graphical User Interface (GUI) for Model Deployment

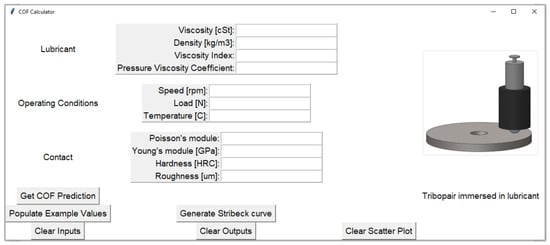

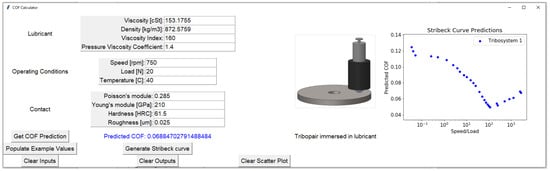

To facilitate the practical application of the trained model, a graphical user interface (GUI) was developed to provide a user-friendly platform for model deployment. This GUI integrates the machine learning model, enabling users to predict the COF based on specified operating conditions, material properties, and lubricant characteristics. In addition to COF predictions, the GUI generates the corresponding Stribeck curve for the selected tribosystem, offering insights across various speeds and loads to cover the entire friction regime.

Figure 12 presents a snapshot of the developed GUI, showcasing its intuitive layout and functionality. Users can input parameters such as sliding speed, load, temperature, and lubricant properties to obtain precise COF predictions. This interface simplifies the deployment of the model, making it accessible for both research and industrial applications. On the other hand, Figure 13 illustrates an example where the GUI is used to predict the COF and generate the Stribeck curve for Tribosystem 1, based on user-defined input values. The tool demonstrates robust performance, offering comprehensive insights into tribological behavior across different operational conditions.

Figure 12.

Graphical User Interface (GUI) designed for the prediction of the coefficient of friction (COF) and visualization of Stribeck curves in lubricated tribosystems. Users can specify parameters such as sliding speed, load, temperature, and lubricant properties to generate COF predictions and corresponding Stribeck curves.

Figure 13.

Example of COF prediction and Stribeck curve generation for Tribosystem 1 using the developed graphical user interface (GUI).

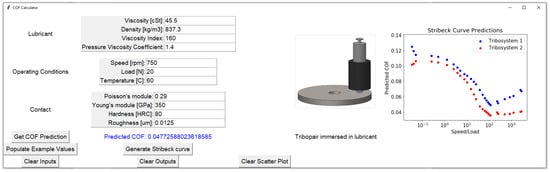

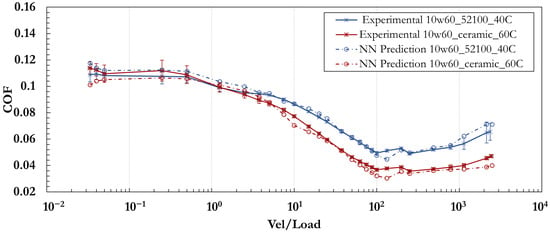

To further showcase the GUI’s capabilities, Figure 14 displays a comparative analysis between Tribosystem 1 and Tribosystem 2. In this case, the GUI generates Stribeck curves for both tribosystems, allowing users to visually compare frictional behavior under different conditions. This functionality is particularly useful for evaluating the performance of different lubricants or materials in diverse tribological applications. Table 6 summarizes the input features and operational parameters used for Tribosystem 1 and Tribosystem 2. This table provides a detailed overview of the variables considered in the GUI, highlighting the versatility of the model in accommodating a wide range of tribological scenarios. In addition to the GUI-generated comparison, Figure 15 contrasts the model predictions against the corresponding experimental Stribeck curves for both tribosystems. The strong agreement between predicted and experimental data demonstrates the model’s reliability and validates its integration within the GUI for real-time Stribeck curve exploration and comparative analysis.

Figure 14.

Comparative Stribeck curve predictions for Tribosystem 1 and Tribosystem 2 obtained using the developed GUI.

Table 6.

Input features of Tribosystem 1 and Tribosystem 2 used for COF prediction and Stribeck curve generation through the graphical user interface (GUI).

Figure 15.

Comparison between experimental and predicted Stribeck curves for Tribosystem 1 (SAE 10W-60 at 40 °C with a 52100 chrome steel ball) and Tribosystem 2 (SAE 10W-60 at 60 °C with ceramic balls). Predictions were generated using the trained machine-learning model, showing good agreement with experimental data. For Tribosystem 2, the MAE, RMSE, MAPE, and are 0.0039, 0.0047, 6.6%, and 0.97, respectively.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the potential of machine learning for predicting the tribological properties of lubricated tribosystems through data-driven approaches, i.e., the integration of experimental data and advanced AI methodologies. By leveraging both empirical data and deep learning techniques, a robust, data-driven model was developed to accurately forecast the coefficient of friction (COF) in ball-on-flat tribosystems across all lubrication regimes. These results highlight the feasibility of unified Stribeck curve prediction when sufficiently comprehensive experimental data are available.

Extensive data collection was undertaken to ensure the model’s reliability and generalization capabilities. A central contribution of this work is the underlying experimental dataset, which was designed to span: multiple lubricants, multiple temperatures, multiple materials, and the full Stribeck curve ( to ). The multilayer perceptron (MLP) regression model achieved a coefficient of determination () of 91%, highlighting its strong predictive performance. Additionally, a Gradient Boosting model was trained, yielding a slightly higher of 93%. Despite the superior performance of Gradient Boosting on structured data, the MLP model’s ability to capture complex, nonlinear relationships underscores its importance for modeling dynamic tribological behavior.

Both models demonstrated excellent generalization to unseen data, with predictions aligning closely with experimental results. Notably, for the first time to our knowledge, a single experimentally validated model successfully captured the behavior of the COF across all three major lubrication regimes: boundary, mixed, and hydrodynamic. This achievement addresses a longstanding challenge in tribological modeling, where accurately representing transitions between regimes has proven elusive.

To validate the accuracy and robustness of the developed model, experimental Stribeck curves were generated for Tribosystem 1 and Tribosystem 2. Figure 15 displays these experimental results, which were directly compared to the Stribeck curves predicted by the GUI. The strong alignment between the predicted and experimental curves demonstrates the model’s ability to accurately capture frictional behavior across diverse operational conditions. This high degree of agreement underscores the model’s potential for practical applications, providing a reliable tool for predicting tribological performance in a wide range of lubricated systems.

The successful deployment of this model opens new avenues for predictive maintenance, lubricant formulation, and system optimization. By offering accurate, real-time predictions, the model supports the development of more intelligent and adaptive tribological systems, contributing to enhanced performance and efficiency in industrial applications.

It is important to note, however, that as a data-driven framework, the model performs optimally within the experimental domain defined by the training dataset. Its predictive accuracy is therefore limited to lubricants and operating conditions that fall within this range—for example, viscosity values comparable to those included in the present study. Nonetheless, the framework is inherently scalable: by incorporating additional data from new lubricants, especially low-viscosity or additive-free base oils, the model can be progressively extended to achieve reliable predictions across a wider range of lubrication systems and industrial applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.G. and C.F.H.III; Methodology, V.G.; Software, V.G.; Validation, V.G.; Formal analysis, V.G.; Investigation, V.G.; Resources, C.F.H.III; Data curation, V.G.; Writing—original draft, V.G.; Writing—review & editing, V.G. and C.F.H.III; Visualization, V.G.; Supervision, C.F.H.III; Project administration, C.F.H.III; Funding acquisition, C.F.H.III. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| Artificial Intelligence | |

| Machine Learning | |

| Neural Network | |

| Multilayer Perceptron | |

| Activation of unit i in layer j | |

| Matrix of weights from layer j to layer | |

| g | Activation function (e.g., sigmoid, ReLU, softmax) |

| Learning rate | |

| b | Bias term |

| Derivative of cost function with respect to weights | |

| Input data matrix, | |

| Output vector of target values, | |

| Input feature vector for the ith instance | |

| Predicted output for the ith instance | |

| Neural network model parameterized by weights | |

| m | Number of training examples |

| n | Total number of features |

| Number of input features | |

| Coefficient of Friction | |

| V | Linear speed [m/s] |

| Rotational or angular speed [rpm] | |

| Applied normal load [N] | |

| Kinematic viscosity [cSt] | |

| Density [kg/m3] | |

| VI | Viscosity index |

| Pressure-viscosity coefficient | |

| T | Temperature [°C] |

| Lubricant bath temperature [°C] | |

| Ambient temperature, approximately 20 °C | |

| Poisson’s ratio of the ball | |

| Young’s modulus of the ball [GPa] | |

| Hardness of the ball [HRC] | |

| Surface roughness of the ball [µm] | |

| Poisson’s ratio of the disk | |

| Young’s modulus of the disk [GPa] | |

| Hardness of the disk [HRC] | |

| Surface roughness of the disk [µm] | |

| He | Hersey number, |

| S | Sommerfeld number, |

| Lambda ratio, | |

| N | Rotational speed [rpm] |

| R | Effective or journal radius [mm] |

| Minimum lubricant film thickness [µm] | |

| Surface roughness of surface 1 [µm] | |

| Surface roughness of surface 2 [µm] |

References

- Hutchings, I.; Shipway, P. Tribology: Friction and Wear of Engineering Materials; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Czichos, H. Tribology: A Systems Approach to the Science and Technology of Friction, Lubrication, and Wear; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Marian, M.; Tremmel, S. Current trends and applications of machine learning in tribology—A review. Lubricants 2021, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz, A.; Marian, M.; Profito, F.J.; Aragon, N.; Shah, R. The Use of Artificial Intelligence in Tribology—A Perspective. Lubricants 2020, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paturi, U.M.R.; Palakurthy, S.T.; Reddy, N.S. The Role of Machine Learning in Tribology: A Systematic Review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2023, 30, 1345–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, K.; Reinicke, R.; Zhang, Z. Wear of polymer composites. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2002, 216, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, P.; Granja, V.; Higgs, C., III. Lifetime Prediction Using a Tribology-Aware, Deep Learning-Based Digital Twin of Ball Bearing-Like Tribosystems in Oil and Gas. Processes 2021, 9, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, M.; Mursak, J.; Bartz, M.; Profito, F.J.; Rosenkranz, A.; Wartzack, S. Predicting EHL film thickness parameters by machine learning approaches. Friction 2023, 11, 992–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Fu, B.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, G. Machine learning and experimental study on a novel Cr–Mo–V–Ti high manganese steel: Microstructure, mechanical properties and abrasive wear behavior. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 31, 1270–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhao, P.; Cui, J.; Wang, L.; Yang, C.; Ouyang, J. Data-Driven Prediction of Coefficient of Friction in Wet Friction Components: A Model Development and Interpretability Analysis. J. Tribol. 2025, 147, 074601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucholz, E.W.; Kong, C.S.; Marchman, K.R.; Sawyer, W.G.; Phillpot, S.R.; Sinnott, S.B.; Rajan, K. Data-Driven Model for Estimation of Friction Coefficient Via Informatics Methods. Tribol. Lett. 2012, 47, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattari Baboukani, B.; Ye, Z.; Reyes, K.G.; Nalam, P.C. Prediction of Nanoscale Friction for Two-Dimensional Materials Using a Machine Learning Approach. Tribol. Lett. 2020, 68, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, R.K.; Woods, L.M. Frictional Properties of Two-Dimensional Materials: Data-Driven Machine Learning Predictive Modeling. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 40149–40159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherguy, O.; Chmielowski, R.; Hachem, E.; Lahouij, I. Deep Learning Prediction of Dry Friction in DLC Coatings Using Literature-Derived Data. Tribol. Lett. 2025, 73, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Gautam, G.; Singh, M.K.; Ji, G.; Katiyar, J.K.; Mohan, S.; Mohan, A. Prediction of Frictional Behaviour Through Regression Equations: A Statistical Modelling Approach Validated with Machine Learning. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2024, 239, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, R.; Fang, T.; Mainwaring, R.; Reddyhoff, T. Predicting the Coefficient of Friction in a Sliding Contact by Applying Machine Learning to Acoustic Emission Data. Friction 2024, 12, 1299–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Gutierrez, R.; Kirkby, T.; Bouassida, H.; Hilbert, M.; Yu, M.; Reddyhoff, T. Complete Stribeck curve prediction by applying machine learning to acoustic emission data from a lubricated sliding contact. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 241, 113544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stribeck, R. Kugellager für Beliebige Belastungen; Buchdruckerei AW Schade: Berlin, Germany, 1901. [Google Scholar]

- Gümbel, L. Das problem der Lagerreibung. Mbl. Berlin. Bez. Ver. Dtsch. Ing 1914, 5, 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Khonsari, M.M.; Booser, E.R.; Nikas, G. On the Stribeck curve. Recent Dev. Wear Prev. Frict. Lubr. 2010, 661, 263–278. [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan, B. Modern Tribology Handbook; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K. Contact Mechanics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Stachowiak, G.; Batchelor, A.W. Engineering Tribology; Butterworth-Heinemann: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM G99-17; Standard Test Method for Wear Testing with a Pin-on-Disk Apparatus. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- Axén, N.; Hogmark, S.; Jacobson, S. Friction and wear measurement techniques. In Modern Tribology Handbook; Bhushan, B., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000; Volume 1, pp. 493–510. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 7148-1:2012; Plain Bearings—Testing of the Tribological Behaviour of Bearing Materials. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- Argatov, I. Artificial neural networks (ANNs) as a novel modeling technique in tribology. Front. Mech. Eng. 2019, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sose, A.T.; Joshi, S.Y.; Kunche, L.K.; Wang, F.; Deshmukh, S.A. A review of recent advances and applications of machine learning in tribology. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 4408–4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velten, K.; Reinicke, R.; Friedrich, K. Wear volume prediction with artificial neural networks. Tribol. Int. 2000, 33, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paturi, U.M.R.; Cheruku, S.; Reddy, N. The role of artificial neural networks in prediction of mechanical and tribological properties of composites—A comprehensive review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 3109–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaumik, S.; Kamaraj, M. Artificial neural network and multi-criterion decision making approach of designing a blend of biodegradable lubricants and investigating its tribological properties. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2021, 235, 1575–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, J.; El Hajj, A.; Vergne, P.; Habchi, W. Machine learning for film thickness prediction in elastohydrodynamic lubricated elliptical contacts. Lubricants 2023, 11, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrock, B.J.; Schmid, S.R.; Jacobson, B.O. Fundamentals of Fluid Film Lubrication; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Zhou, F.; Liu, W. Influence of elastic modulus and surface texture on elastohydrodynamic lubrication film thickness. Tribol. Int. 2021, 155, 106776. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Q.; Huang, J.Y.; Zhong, Y. Effects of surface energy on boundary lubrication: A molecular dynamics study. Langmuir 2011, 27, 14176–14181. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Seeger, S.; Grunlan, J.C. Role of surface energy and wettability in contact angle hysteresis. Langmuir 2016, 32, 5214–5220. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, B.N.; Volokitin, A.I. Rubber friction: Role of the flash temperature. Eur. Phys. J. E 2002, 9, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.