Abstract

The machining of Ti-6Al-4V thin-walled parts is characterized by high cutting temperatures, significant force fluctuations, and complex thermomechanical coupling. Cryogenic Minimum Quantity Lubrication Technology (CMQL) uses bio-lubricant as the lubrication carrier, combined with the cooling characteristics of cryogenic temperature medium, showing good cooling and lubrication performance and environmental friendliness. However, the cooling and lubrication mechanism of different cryogenic media in synergy with bio-lubricants is still unclear. This paper establishes convective heat transfer coefficient and penetration models for cryogenic media in the cutting zone, based on the jet core theory and the continuum medium assumption. The model results show that cryogenic air has a higher heat transfer coefficient, while cryogenic CO2 exhibits a better penetration ability in the cutting zone. Further milling experiments show that compared with cryogenic air, the average temperature rise, average cutting force and surface roughness of workpiece surface with cryogenic CO2 as cryogenic medium are reduced by 23.6%, 32.8%, and 11.8%, respectively. It is considered that excellent permeability is the key to realize efficient cooling and lubrication in the cutting zone by Cryogenic CO2 Minimum Quantity Lubrication Technology. This study provides a theoretical basis and technical reference for efficient precision machining of titanium alloy thin-walled parts.

1. Introduction

Titanium alloy has an irreplaceable position in aerospace, medical equipment, national defense and military industry, and other high-tech fields due to its excellent specific strength, corrosion resistance, and high temperature stability [1,2]. Titanium alloy thin-walled parts (wing beam, door frame, satellite bracket) have become the core materials of modern high-precision equipment design because of their advantages of maintaining sufficient stiffness and fatigue life while achieving structural lightweight [3,4]. However, titanium alloy has extremely low thermal conductivity (7–15 W/(m·K)) and significant chemical activity at high temperature, which makes its thin-walled structure face multiple challenges in the machining process: the accumulation of cutting heat is easy to cause tool thermal wear and workpiece thermal deformation [5,6]; the material adhesion tendency leads to the increase in cutting force, which aggravates the deterioration of surface quality and tool failure [7,8]. Thermal–mechanical coupling also induces vibration and dimensional deviation, which seriously affects the service reliability of components [9]. Therefore, in order to effectively improve the force and heat generated in the cutting process, it is very important to optimize the cooling and lubrication conditions in the cutting zone. Efficient cooling performance can quickly derive the heat in the cutting zone and significantly reduce the temperature of the tool–workpiece interface, thereby effectively suppressing thermal deformation and extending the tool life while improving the machining accuracy [10,11]. The perfect lubrication mechanism can reduce the cutting force by reducing the friction coefficient, reduce the energy consumption while inhibiting the formation of built-up edge, and significantly improve the surface quality of the workpiece [12,13].

To address the simultaneous demand for efficient cooling and lubrication in machining, Cryogenic Minimum Quantity Lubrication (CMQL) has emerged as an advanced technique. This technology achieves synergistic enhancement of cooling and lubrication by atomizing a minimal quantity of bio-lubricant with a cryogenic gas stream and delivering it precisely to the cutting zone. Recognized for its environmental and economic benefits, CMQL offers a sustainable solution for processing titanium alloy thin-walled components [14,15]. Among various cryogenic media, cryogenic air is frequently adopted in CMQL systems due to its cost-effectiveness and safe handling. Benjamin and colleagues [16] demonstrated that integrating MQL with cryogenic air during Ti-6Al-4V milling could reduce the peak cutting temperature by 7.5% compared to conventional MQL, effectively mitigating heat accumulation issues. Subsequent studies by Su et al. [17] on titanium alloys and Zhang et al. [18] on M300 steel further confirmed the cooling efficacy of the CA+MQL approach. Research by Wu et al. [19] indicated significant improvements in the machining of thin-walled parts, where CA+MQL led to a reduction in cutting force by 28.5–31.2% and enhanced surface roughness by 34.5–45.8% compared to traditional methods. In ultra-precision turning of 3Cr2NiMo steel, Zou et al. [20] reported that CA+MQL effectively lowered cutting forces while improving tool life and surface finish. More recently, the work of Liu Mingzheng et al. [21] extended CMQL application to grinding, where a developed heat transfer model validated its capability to improve grinding zone cooling and workpiece surface integrity within a temperature range of −10 °C to −40 °C.

In addition to cryogenic air, CO2 also shows unique advantages in CMQL technology due to its excellent environmental protection characteristics and stronger cryogenic performance. Sanchez et al. [22] confirmed by grinding experiments that the CO2 medium can significantly improve the cooling and lubrication performance, effectively reducing the grinding temperature and thermal damage. Grguraš et al. [23] found that LCO2+MQL can significantly reduce the cutting force and improve the machining stability in Ti-6Al-4V drilling. The comparative study of Gross et al. [24] shows that CMQL technology not only has excellent performance in reducing cutting temperature, but also has higher energy utilization efficiency. Pereira et al. [25] proved that compared with MQL, LCO2+MQL has advantages in tool life, cost, and environmental protection through AISI 304 turning experiments.

Although the above research has carried out a lot of analysis on the performance of CMQL in metal cutting process, and verified its effectiveness in cooling, reducing friction and improving surface quality, there are still obvious cognitive gaps and deficiencies in the current research. Most of the studies focus on the experimental optimization of process parameters and the comparison of macroscopic effects, and lack the systematic mechanism analysis of the distribution behavior, penetration mechanism and thermo-mechanical coupling effect of different cryogenic media in the cutting zone. In particular, the key scientific issues such as how the physical properties of the medium (density, viscosity, diffusivity, etc.) affect its jet shape, heat transfer efficiency, and lubricant transport capacity are insufficiently understood, resulting in limited prediction and interpretation of the microscopic mechanism of the cutting zone. These shortcomings make it difficult to reveal the synergistic mechanism of different cryogenic media in CMQL.

Based on this, this paper theoretically compares the jet characteristics and heat and mass transfer behavior of the two media by establishing a heat transfer coefficient model and a cutting zone penetration model of cryogenic medium. The milling experiments of CA+MQL and LCO2+MQL were carried out to quantitatively evaluate the performance differences in cutting force, temperature, and surface integrity. Finally, combined with the model and experimental results, the cooling and lubrication mechanism of different cryogenic media in the processing of titanium alloy thin-walled parts is clarified, which provides a theoretical basis for the medium optimization and parameter optimization of CMQL process.

In order to conceptually compare the jet properties and heat/mass transfer behavior of liquid CO2 and cryogenic air, this study builds cutting zone penetration and heat transfer coefficient models for cryogenic media. To quantitatively assess the differences in cutting force, temperature control, and surface integrity between CA+MQL and LCO2+MQL, milling tests were carried out. The combined analysis of modeling and experimental findings elucidates the cooling and lubricating mechanisms of different cryogenic media in machining titanium alloy thin-walled components, providing a theoretical foundation for medium selection and parameter optimization in CMQL procedures.

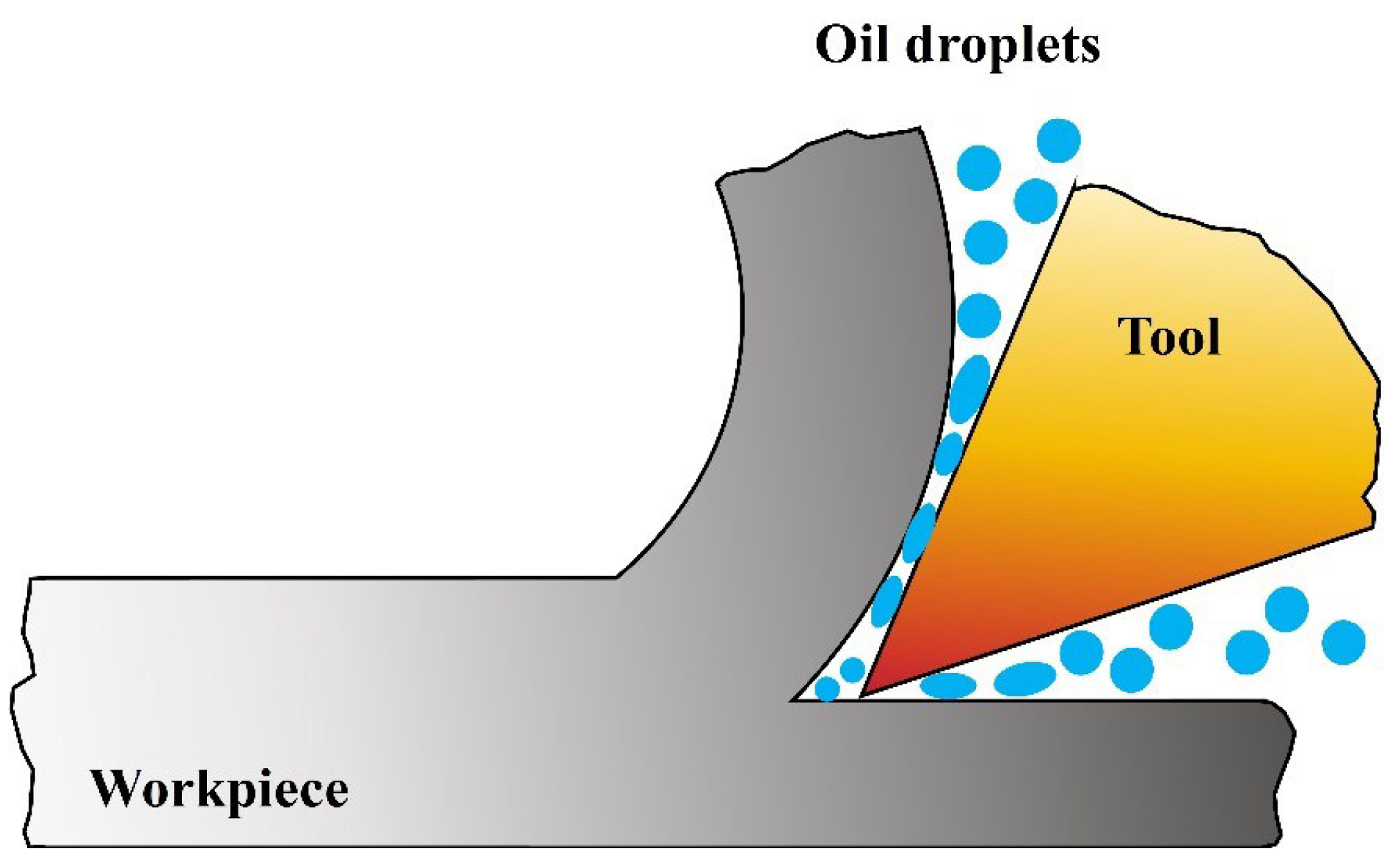

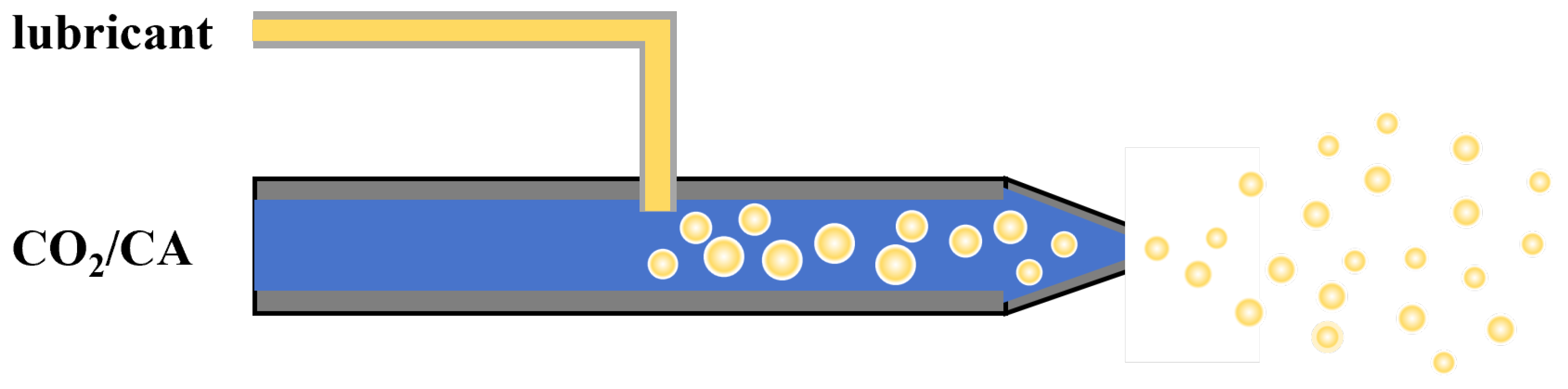

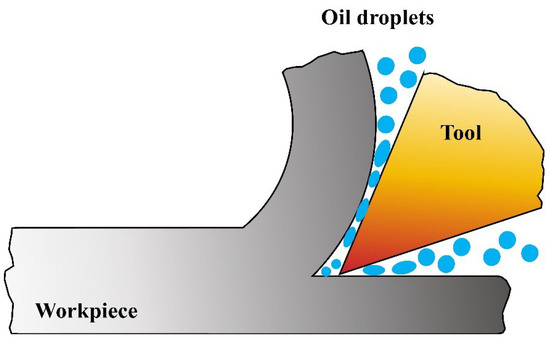

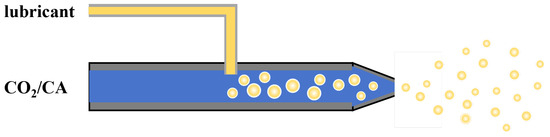

2. Heat Transfer Mechanism in the Cutting Zone Under CMQL

The cooling and lubrication effectiveness of CMQL in the cutting zone mainly depends on the forced convective heat transfer between the cryogenic medium and the cutting interface. Nevertheless, the overall performance is influenced by both the heat transfer coefficient of the cryogenic medium and the penetration ability of the cryogenic medium along with the micro-lubricant in the cutting area. An elevated heat transfer coefficient enhances the forced convective heat exchange between the cryogenic medium and the cutting zone, facilitating efficient dissipation of the substantial heat produced during machining. This contributes to better machining quality and prolonged tool service life. Concurrently, the penetration capability of the cryogenic medium plays a critical role in determining its distribution depth and coverage within the cutting area, which in turn affects both the heat transfer and lubrication outcomes. When the gas jet exhibits high permeability, it can more effectively overcome the high-temperature and high-pressure conditions in the cutting zone and reach the tool/workpiece and tool/chip contact interfaces. This improves the convective heat exchange between the cryogenic medium and the high-temperature cutting area, leading to a notable enhancement in cooling performance. It is important to highlight that the lubrication performance of the micro-lubricant is directly affected by the cryogenic medium. A cryogenic medium with outstanding penetration characteristics can efficiently assist in delivering the micro-lubricant into the cutting zone, forming a stable boundary film at the friction interface. This is essential for reducing interfacial friction and minimizing tool wear. A schematic representation of the cooling and lubrication mechanism in the cutting zone is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the cooling and lubrication mechanism in the cutting zone.

2.1. CMQL Cryogenic Medium Heat Transfer Coefficient Model

Rohsenow et al. developed a series of dimensionless correlations to describe convective boundary layers, providing an important theoretical foundation for analyzing convective heat transfer of coolant jets in the cutting zone [26]. The physical properties of cryogenic CO2 (−30 °C) and cryogenic air (−30 °C) are listed in Table 1, with all data sourced from NIST REFPROP 10.0 and the NIST Chemistry WebBook.

Table 1.

Physical parameters of cryogenic CO2 and cryogenic air.

The jet parameters of the two cooling and lubrication methods are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Jet parameters of CMQL.

The heat transfer coefficient of the coolant can be expressed using the Nusselt number as follows.

where is the convective heat transfer coefficient of the coolant (W/m2·K), is the convective heat transfer coefficient of the coolant (W/m2·K), is the thermal conductivity of the gas jet (W/m·K), and is the characteristic length (m), which in this case refers to the nozzle diameter.

The Nusselt number can be determined using the following empirical correlation [27]:

where is the Reynolds number and is the Prandtl number. The Reynolds number can be calculated using the following formula [28]:

where is the velocity of the gas jet (m/s), and is the kinematic viscosity of the gas jet (m2/s).

The velocity of the gas jet can be expressed as follows:

where is the volumetric flow rate of the gas (L/min), and is the cross-sectional area of the nozzle (m2).

The Prandtl number can be determined using the following method [28]:

and represent the specific heat capacity (J/kg·K) and density (kg/m3) of the gas jet, respectively.

The heat transfer coefficient of the gas jet can be expressed as follows [28]:

2.2. Penetration Model of Cryogenic Media in the Cutting Zone

In this paper, the penetration ability of cryogenic air and cryogenic CO2 in the cutting zone is comprehensively analyzed from three aspects: jet core length, jet mass flow rate, and jet mass transfer efficiency. The core length of the jet reflects the effective range of the jet in the cutting zone and determines the initial kinetic energy and stability of the cryogenic medium. The mass flow rate directly reflects the total amount of medium participating in heat transfer per unit time, which affects the cooling and chip removal capacity of the cutting zone. The mass transfer efficiency of the jet determines the actual heat transfer effect between the jet and the cutting interface and reveals the difference in thermodynamic characteristics in the infiltration process. The three are complementarily verified from the three dimensions of spatial action range, medium transport capacity, and energy transfer efficiency, which together constitute a multi-scale and multi-parameter comprehensive evaluation system for permeability to ensure the comprehensiveness and reliability of the conclusion.

The jet core length can be determined using the following equation [29]:

where denotes the jet core length (m); is an empirical coefficient influenced by nozzle type and fluid conditions, and is taken as 6 in this model; represents the nozzle diameter (m); is the density of the gas jet (kg/m3); and is the ambient gas density (kg/m3). In this study, the ambient gas is air at room temperature and standard atmospheric pressure, with a density of 1.184 kg/m3.

The jet mass flow rate can be expressed as follows:

where is the jet mass flow rate (kg/s); is the jet velocity (m/s); and is the cross-sectional area of the nozzle (m2).

In the study of mass transfer processes, transfer efficiency can be established through the relationship between the Sherwood number (Sh) and the mass transfer coefficient . The Sherwood number is a dimensionless quantity that characterizes the relative strength of convective mass transfer to molecular diffusion. For the flow regime of nozzle jets, the classical empirical correlation for the Sherwood number is given as follows:

where is the Reynolds number and is the Schmidt number, is the distance from the nozzle to the cutting zone, and is the nozzle diameter. In this model, L/d = 20, n = 0.5.

The Schmidt number can be expressed as

where denotes the molecular diffusion coefficient (m2/s).

The mass transfer coefficient can be expressed as

where denotes the distance from the nozzle to the cutting zone.

The mass transfer efficiency can be expressed as

where denotes the gas concentration, and the concentration difference between the inside and outside of the cutting zone is represented by . The concentration gradient can be approximated as , leading to the simplified expression:

Therefore, the mass transfer efficiency can be expressed as

2.3. Model Results and Analysis

Based on the above model calculations, the jet heat transfer coefficient, jet core length, jet mass flow rate, and jet mass transfer coefficient for cryogenic CO2 and cryogenic air are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Jet characteristics of cryogenic CO2 and cryogenic air.

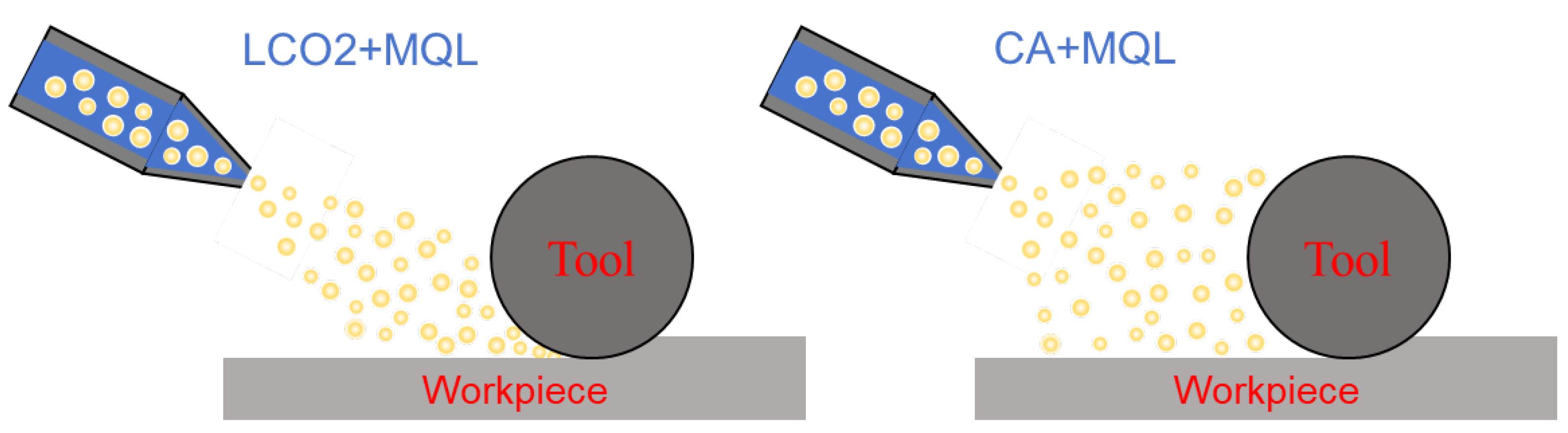

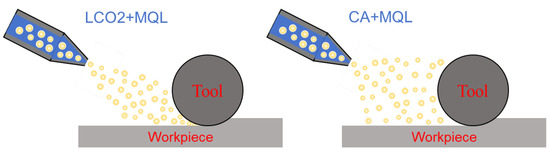

The results show that although the convective heat transfer coefficient of low-temperature CO2 jet is lower than that of low-temperature air jet, it has obvious advantages in key parameters such as jet core length, mass flow rate, and mass transfer efficiency by virtue of its physical advantages such as higher density, larger molecular weight, and lower dynamic viscosity, which directly leads to its stronger penetration ability in the cutting zone during the cutting process, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of different low temperature jet morphology and permeability force.

The specific mechanism of low-temperature CO2 showing better penetration ability in the cutting zone is as follows: First, the higher density of CO2 makes its jet core length (15.5 mm) increase by 16.5% compared with low-temperature air (13.3 mm). This means that the CO2 jet can maintain a longer undisturbed core area before reaching the cutting zone, with higher momentum and stability, providing a stronger initial kinetic energy for effectively penetrating the cutting zone. Secondly, at the same volume flow rate, higher density is directly converted into larger mass flow rate. This indicates that more CO2 medium participates in the heat exchange process in the cutting zone per unit time, thereby improving the overall transport capacity of the cooling medium. Finally, CO2 has more efficient momentum and mass transfer characteristics. Its low viscosity reduces the flow resistance, which is beneficial for the medium to cover the tool–workpiece–chip contact interface more effectively and promote the transport of micro-lubricants.

In summary, the convective heat transfer coefficient only describes the heat transfer capacity of the medium after reaching the interface, and the actual performance of the cooling efficiency depends first on whether the medium can effectively penetrate the high-temperature and high-pressure cutting zone barrier and cover the heat source. With its physical advantages, low-temperature CO2 fully surpasses low-temperature air in terms of permeability, which ensures that the cooling effect and lubricant can be directly and stably transported to the tool–workpiece and tool–chip contact interfaces that most need to cool down and reduce friction. Therefore, excellent permeability is the key physical mechanism to compensate or even exceed its theoretical convective heat transfer coefficient, and ultimately achieve better cooling and lubrication effect.

The above research results reveal the performance difference and physical mechanism of cryogenic CO2 and cryogenic air jets. However, when cryogenic CO2 and cryogenic air are used as cryogenic media in CMQL technology, the cooling and lubrication performance in the cutting zone needs to be further clarified. Therefore, in this paper, the milling experiments of titanium alloy thin-walled parts were carried out under the conditions of CA+MQL and LCO2+MQL, and the effects of two cryogenic media on the cooling and lubrication performance of CA+MQL and LCO2+MQL technology due to the difference in cooling and lubrication mechanism were explored.

3. Experimental Scheme

In this experiment, the milling experiments of titanium alloy thin-walled parts were carried out under CA+MQL and LCO2+MQL conditions, respectively. The temperature and cutting force of the cutting zone were measured, and the surface quality of the workpiece under different lubrication conditions was compared and analyzed.

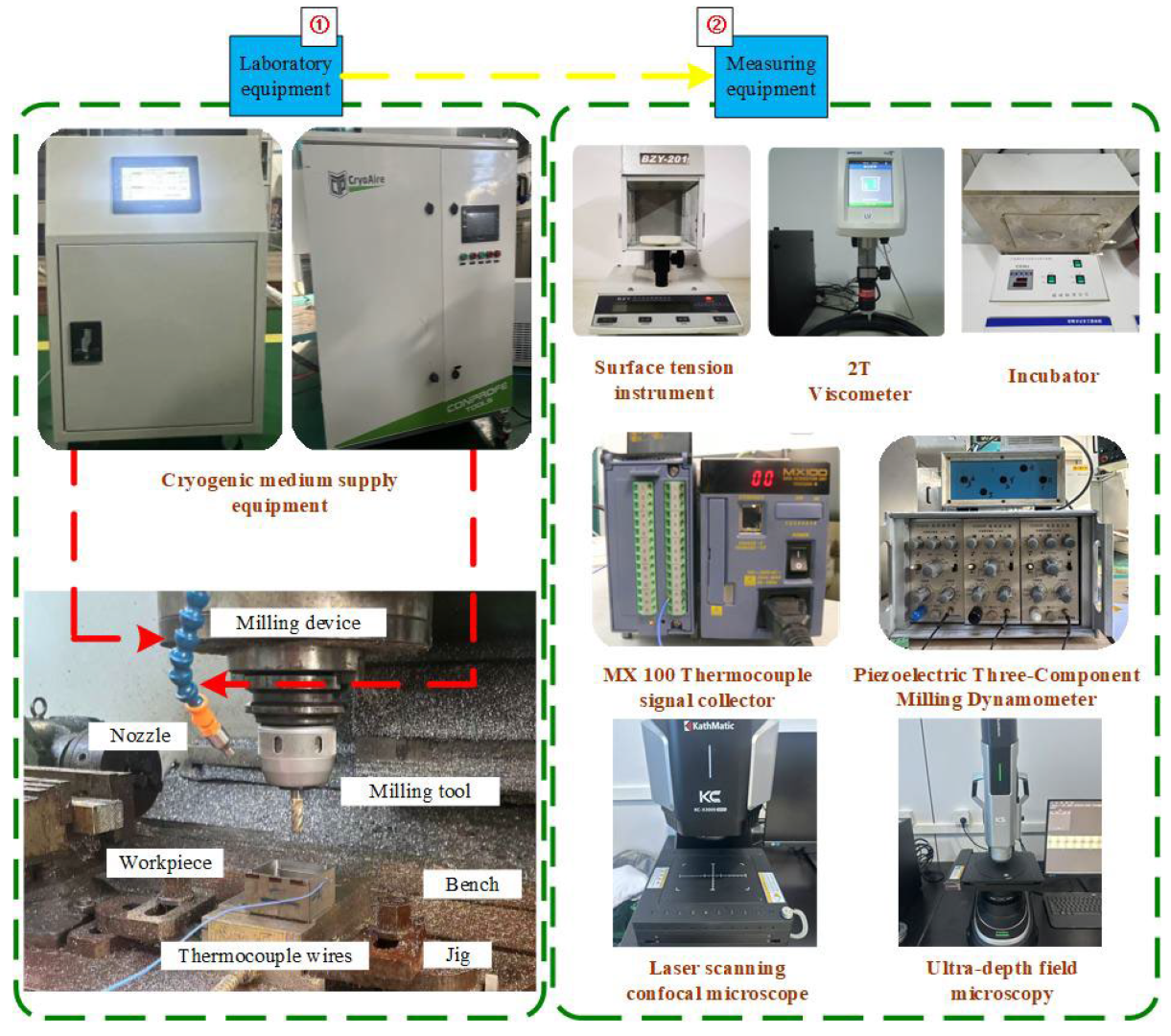

3.1. Experimental Equipment

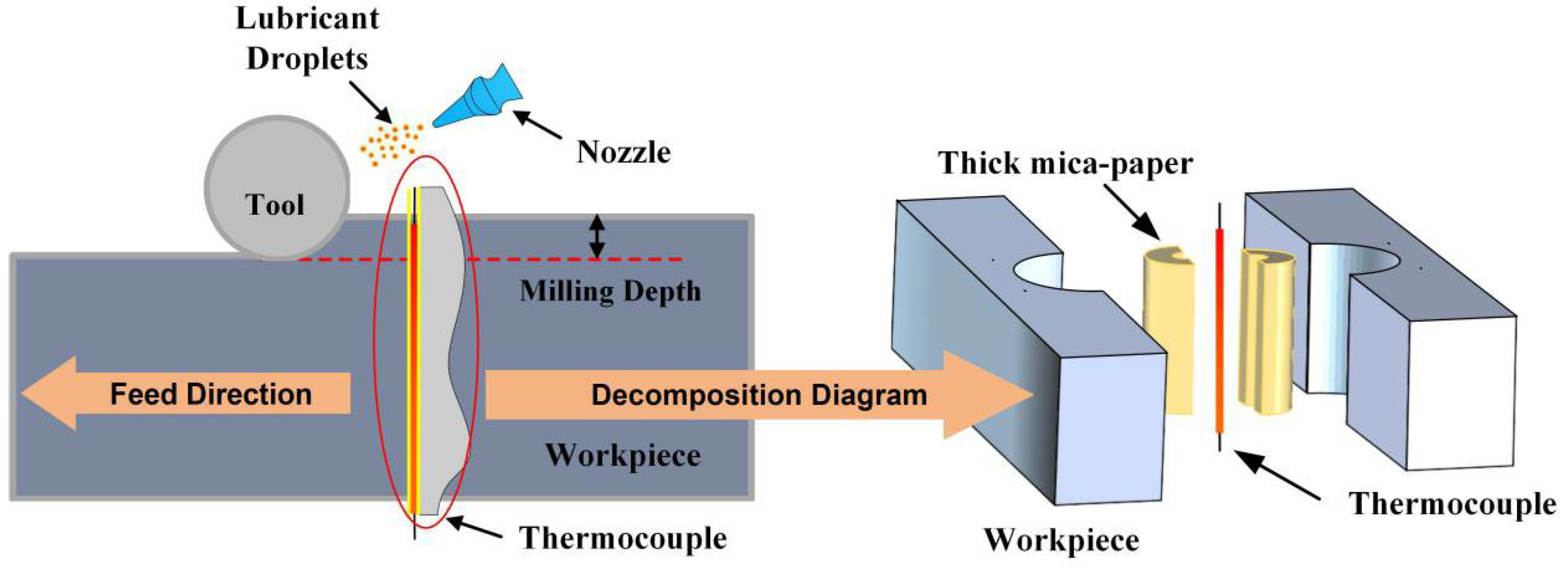

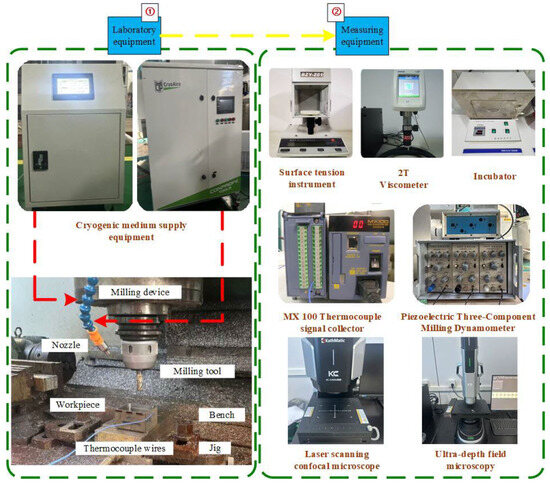

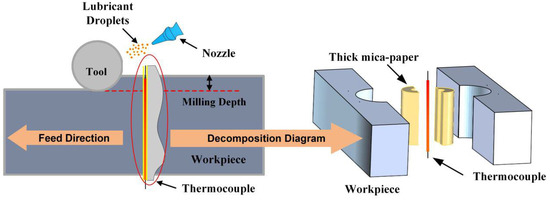

The milling process and associated measurement apparatus used in this experiment are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Cutting process and measurement equipment.

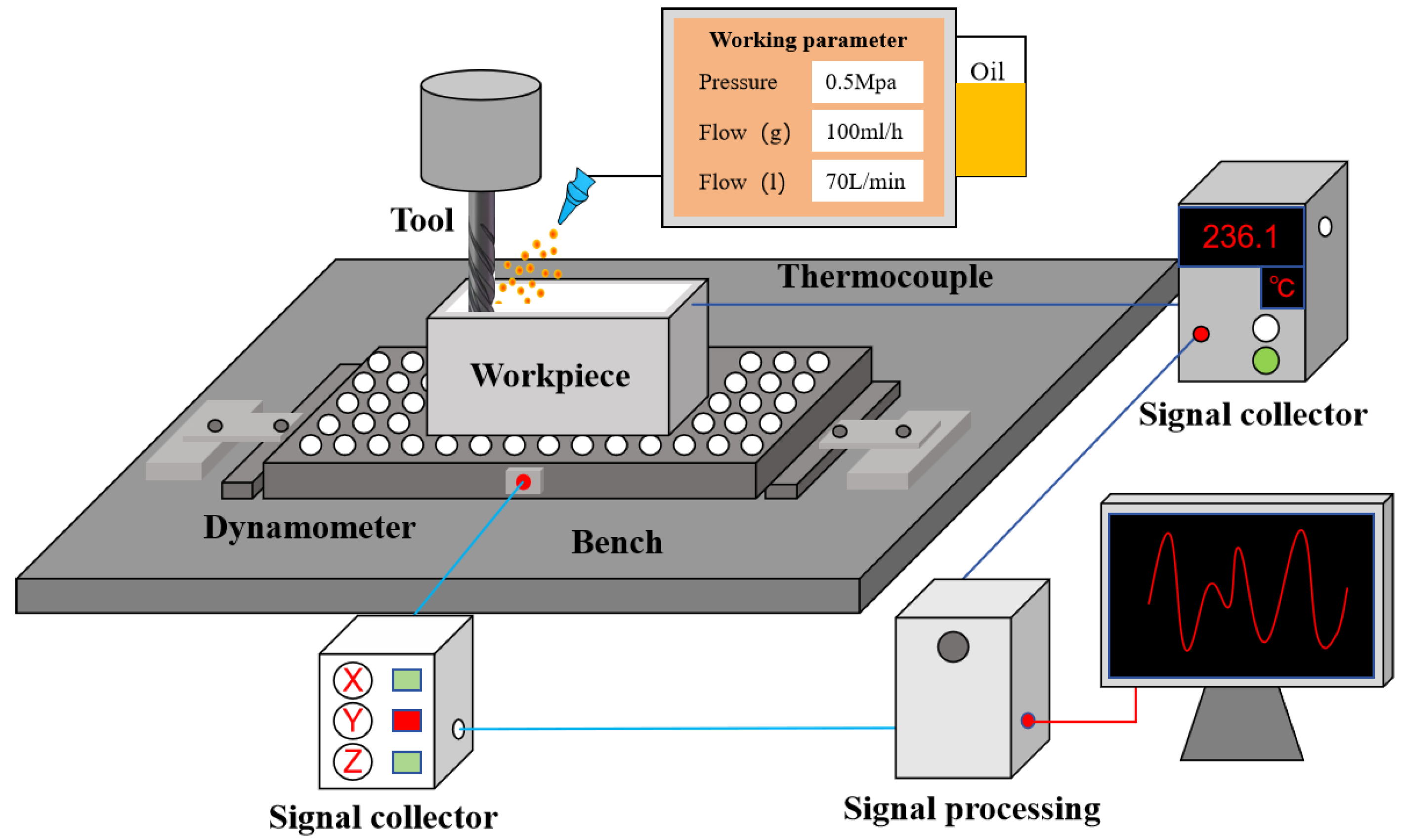

The milling machine used in the experiment is MV-80 CNC milling machine(Wintec Industries, Inc., Cypress, CA, USA), and the tool is a tungsten steel milling cutter with 4-edge spiral unequal division with a diameter of 12 mm. The surface tension of soybean oil was measured using a BZY-201 tensiometer (Shanghai Fangrui Instruments, Shanghai, China), while its dynamic viscosity was determined with a DV-2T viscometer (Brookfield Engineering Laboratories, Inc., Middleboro, MA, USA). For low-temperature viscosity measurements, the soybean oil was preconditioned using a thermostatic water bath. Surface quality of the workpiece was evaluated using a KS-X3000 laser confocal microscope (Nanjing Kaishimai Technology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China), and surface morphology was observed with a KS 3D digital microscope (Nanjing Kaishimai Technology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China). The cutting force is measured by piezoelectric three-direction milling dynamometer. Cutting zone temperature is measured by a thermocouple method. The thermocouple signal collector model used is MX 100 (Omega Engineering, Inc., Norwalk, CT, USA). Figure 4 is the cutting and measuring diagram of this experiment.

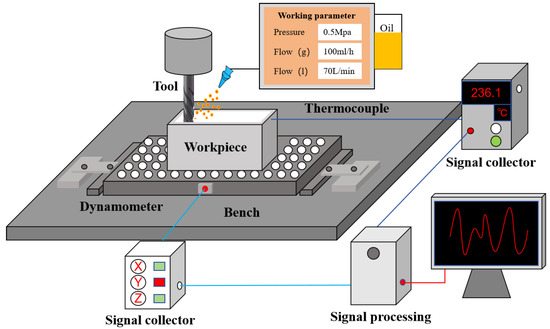

Figure 4.

Cutting and measurement diagram.

In this experiment, an internal premixed gas–liquid supply system was used. In order to realize the full atomization of lubricating oil, the oil circuit and the low temperature gas pipeline are converged at 100 mm upstream of the nozzle outlet, so that the oil is mixed and broken with the gas in a long pipeline, and finally the gas–liquid two-phase flow is formed through a convergent nozzle. The specific structure is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Gas–liquid mixing diagram.

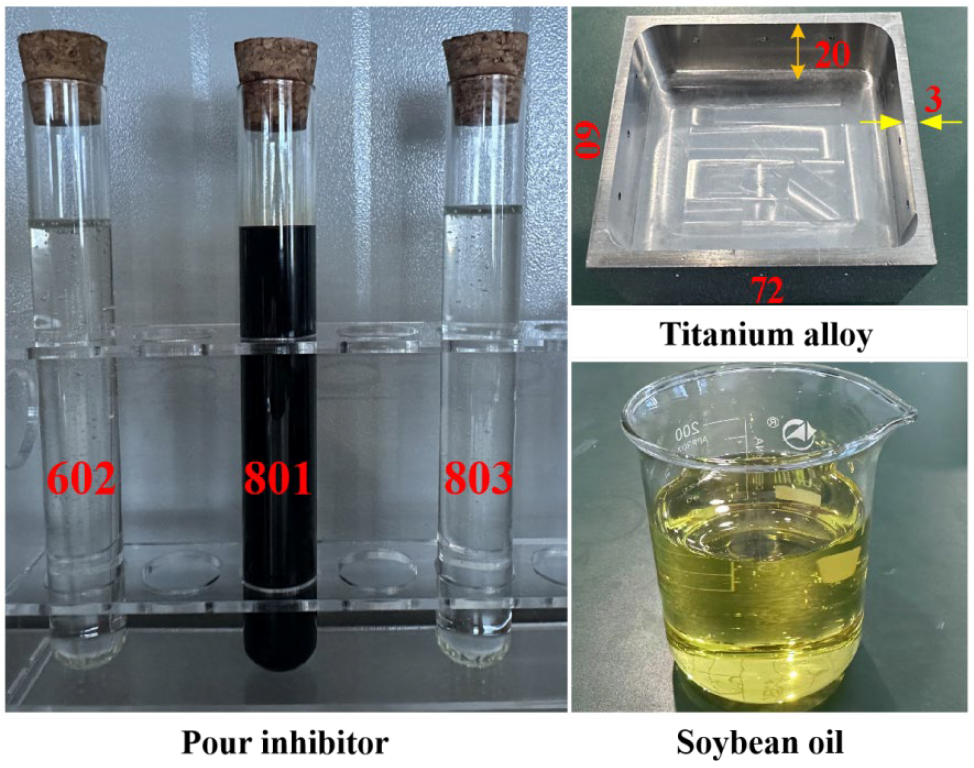

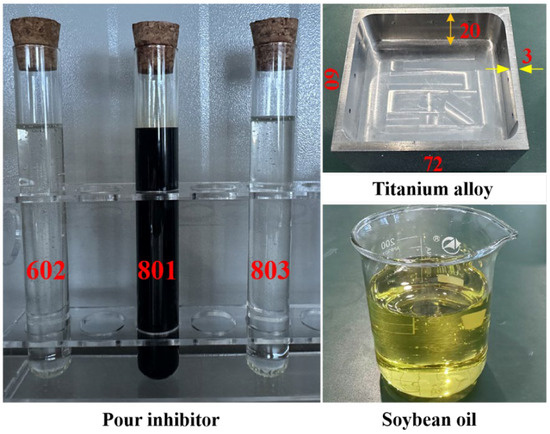

3.2. Experimental Materials

The base oil used in the experiment was soybean oil, and the effects of three different types of pour inhibitors (T602, T801 and T803) on the properties of soybean oil were determined. The workpiece material is titanium alloy, the brand is Ti-6Al-4V, the size is 72 mm × 60 mm × 38 mm, which contains four thin walls, the thickness is 3 mm, and the thin wall height is 20 mm. The structure is a typical thin-walled workpiece; the details are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Experimental materials.

Thin-walled parts were obtained by pre-processing on Ti-6Al-4V material, and all final dimensions (including 3 mm wall thickness) were precisely milled to ensure geometric accuracy. The workpiece was rigidly clamped from the bottom by a special precision fixture to ensure stable clamping. We ensured the uniformity of the clamping force by controlling the bolt torque and checked the clamping state of the workpiece before each experiment to ensure the consistency of the workpiece to the maximum extent.

The main physical properties of titanium alloy Ti-6Al-4V are shown in Table 4:

Table 4.

Physical property of Ti-6Al-4V.

Soybean oil is primarily composed of fatty acids, with its specific chemical composition detailed in Table 5. Relevant studies indicate that soybean oil serves as an ideal lubricant because it can form not only a physical adsorption film but also a chemical adsorption layer on metal surfaces [30,31].

Table 5.

Contents of various fatty acids in soybean oil.

3.3. Experimental Parameters and Method

In order to maintain the consistency of the experiment, the jet parameters and cutting parameters of the two lubrication conditions are consistent. The jet parameters are given in Table 2 above, and the cutting parameters are shown in Table 6:

Table 6.

Milling parameters.

In this experiment, the supply temperature of the two low-temperature media is set to −30 °C, but the refrigeration mechanism of the two is completely different. CA+MQL is passive cooling, and its cooling capacity comes from an external refrigerator. LCO2+MQL is an active refrigeration system: liquid CO2 undergoes a phase change in the pipeline due to pressure changes, absorbing a large amount of latent heat, thereby achieving rapid cooling. This phase change process interacts with the heat exchange between the pipeline and the environment, so that the nozzle outlet temperature is regulated by a complex system. The key influencing factors include nozzle structure, pipeline size, working pressure and flow rate, mixing strategy, and environmental conditions. Therefore, under the processing parameters set in this experiment, the temperature of the low-temperature medium at the nozzle outlet is controlled by adjusting the length of the pipeline. After measurement, the temperature at 40 mm downstream of the nozzle outlet can be stabilized at −30 ± 2 °C when the pipeline length is 1.8 m. The temperature can maintain a stable cooling time of about 5–8 min under the condition that the cylinder capacity is allowed.

Before each cutting experiment, the parallelism of thin-walled parts is measured by a micrometer, and then adjusted accordingly to avoid dimensional errors caused by the geometric shape and clamping of the workpiece. Each cutting uses a new tool and measures the overhang length of the tool to avoid the effect of tool runout.

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

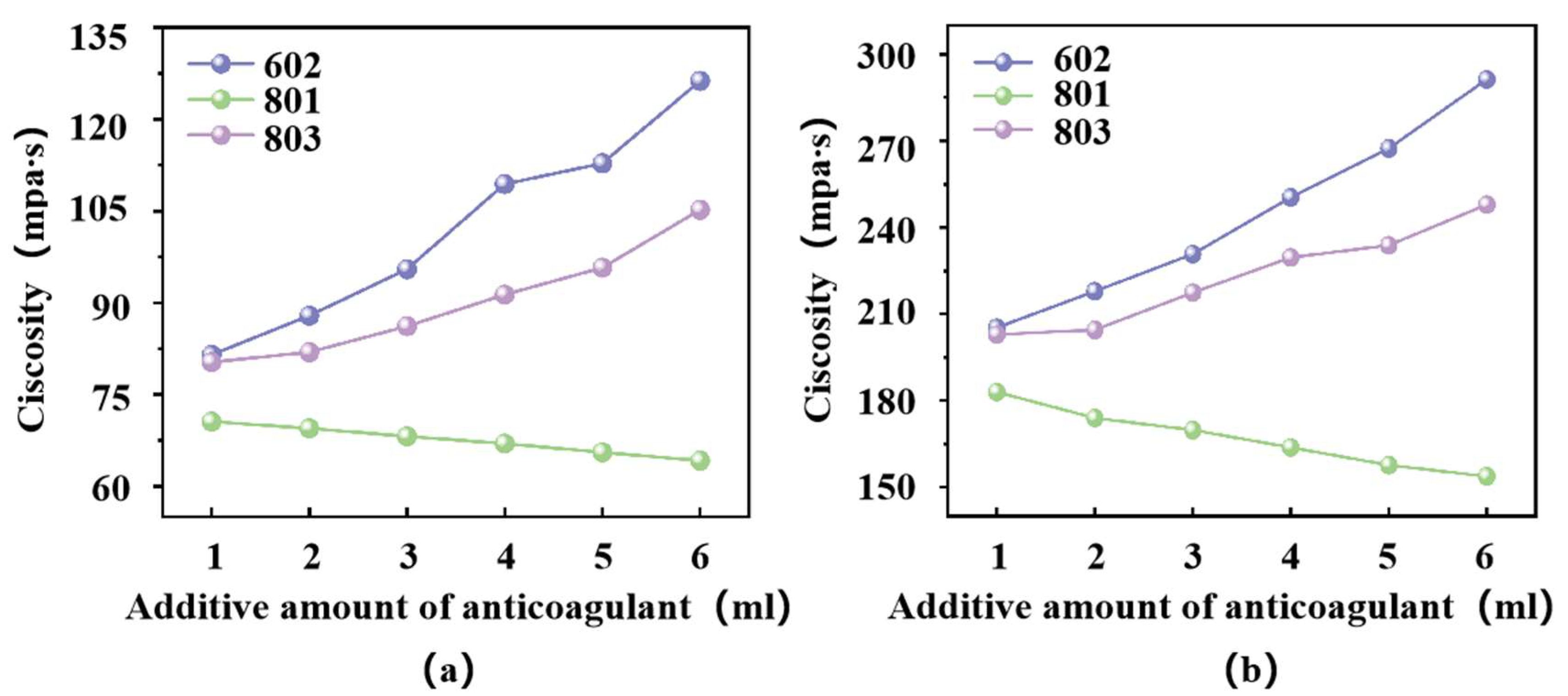

4.1. Anticoagulant Type and Optimum Dosage

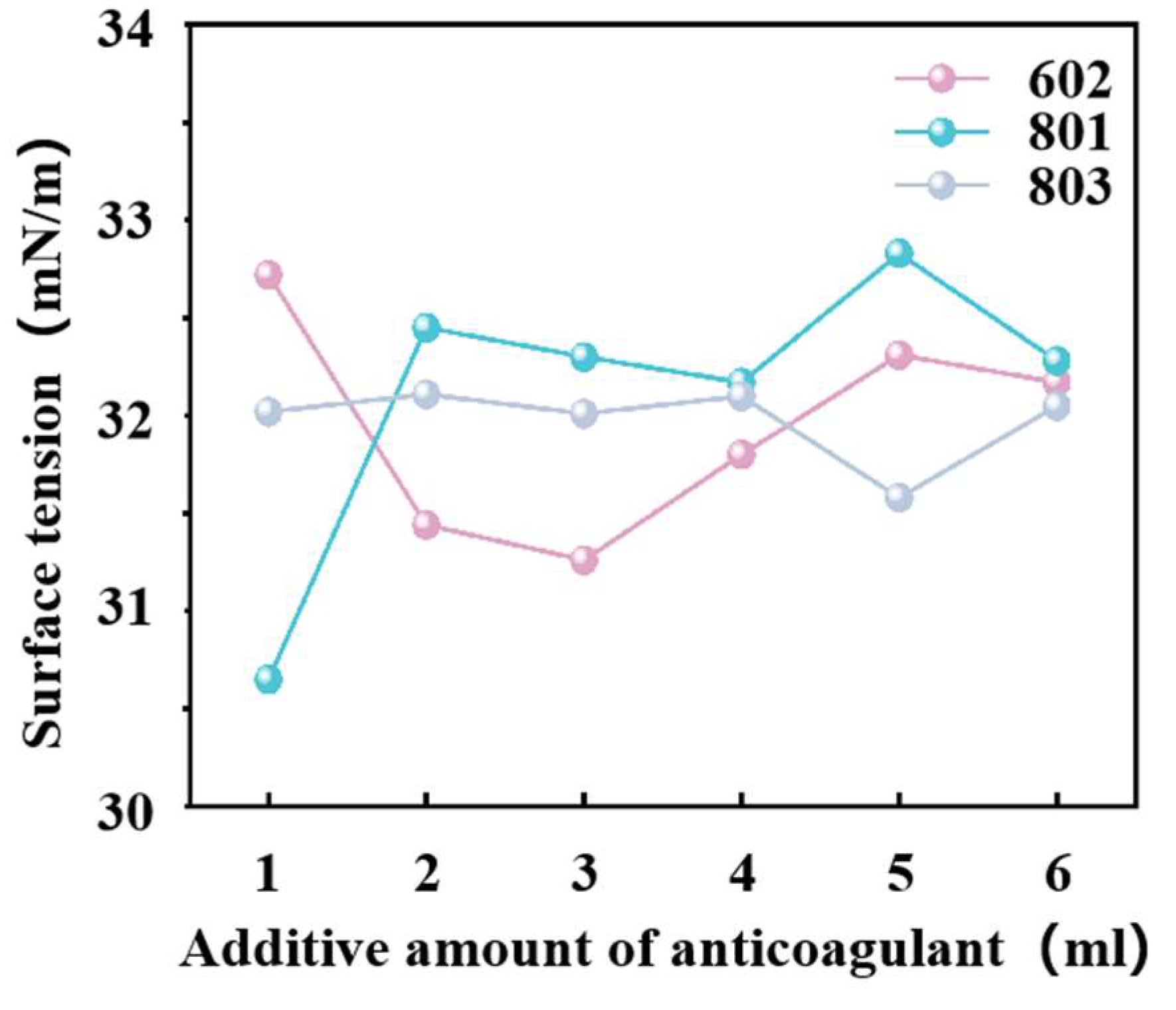

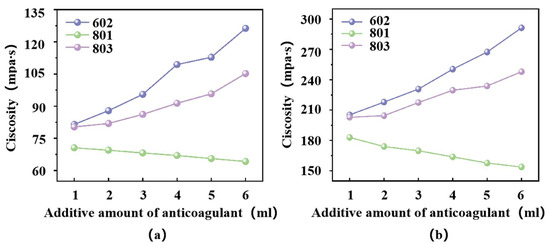

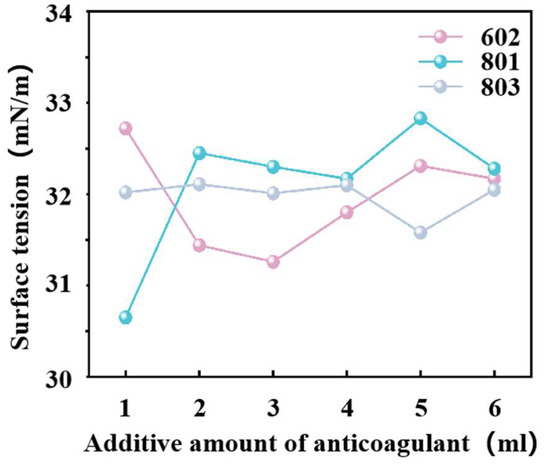

The dynamic viscosity and surface tension of the lubricant directly affect the cooling and lubrication performance of CMQL during the cutting process. Therefore, this experiment measured the effects of three different types of pour inhibitors on the dynamic viscosity and surface tension of soybean oil under different addition amounts. The anticoagulant models were T602, T801, and T803.

The viscosity curves and surface tension curves of soybean oil with different pour inhibitors are shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8. The experimental results show that when different pour inhibitors are added to soybean oil, the surface tension does not show a significant change trend. The reason may be that the molecular structure of the anticoagulant is highly compatible with soybean oil, resulting in its uniform dispersion in the oil phase rather than enrichment at the interface. At room temperature (25 °C), the 602 anticoagulant showed significant thickening effect (increased to 126.3 mPa·s), the 803 anticoagulant showed mild thickening effect (increased to 105.2 mPa·s), and the 801 anticoagulant showed viscosity reduction characteristics (decreased to 64.20 mPa·s). In the low-temperature (0 °C) environment, this trend is more obvious, and the viscosity of the 801 anticoagulant system is reduced by 19%, which is significantly better than the other two pour inhibitors. It is noteworthy that when the dosage of anticoagulant 801 exceeds 3% of the lubricant’s volume fraction, flocculent precipitates emerge within the oil phase. Upon analysis, this phenomenon is likely attributed to the mismatch between the polymeric characteristics of the anticoagulant and the solubility parameters of soybean oil, resulting in limited solubility in the oil phase. Consequently, molecular chains undergo entanglement and self-aggregation, ultimately leading to the precipitation of flocculent matter.

Figure 7.

Dynamic viscosity of soybean oil with different pour inhibitors. (a) Dynamic viscosity of soybean oil with different anticoagulants at room temperature. (b) Dynamic viscosity of soybean oil with different anticoagulants at low temperature.

Figure 8.

Surface tension of soybean oil with different pour inhibitors at room temperature.

Based on the above experimental results, T801 was selected as a lubricant additive in this study, and the optimum addition amount was determined to be 3% of the base oil volume fraction. This concentration is within the solubility safety threshold range and can achieve significant viscosity reduction effect.

4.2. Cutting Temperature Analysis

In this study, the cutting zone temperature under CA+MQL and LCO2+MQL conditions was measured via the thermocouple method. As shown in Figure 9, a temperature measuring hole with a diameter of 1.5 mm and a depth of 3 mm was pre-processed on the wall surface of the thin-walled specimen. During the measurement, the thermocouple probe is inserted horizontally from the outside of the specimen into the bottom of the hole to ensure that the insertion depth is 3 mm. Although the thermocouple has a certain response delay to the dynamic temperature change, which may lead to the deviation between the measured temperature value and the instantaneous cutting temperature, the core of this study is the relative comparison of the two cooling and lubrication conditions, rather than the absolute accurate value of the temperature, and all experiments are carried out under the same conditions. Therefore, the systematic deviation does not affect the conclusion of the cooling performance of the two.

Figure 9.

Thermocouple measurement diagram.

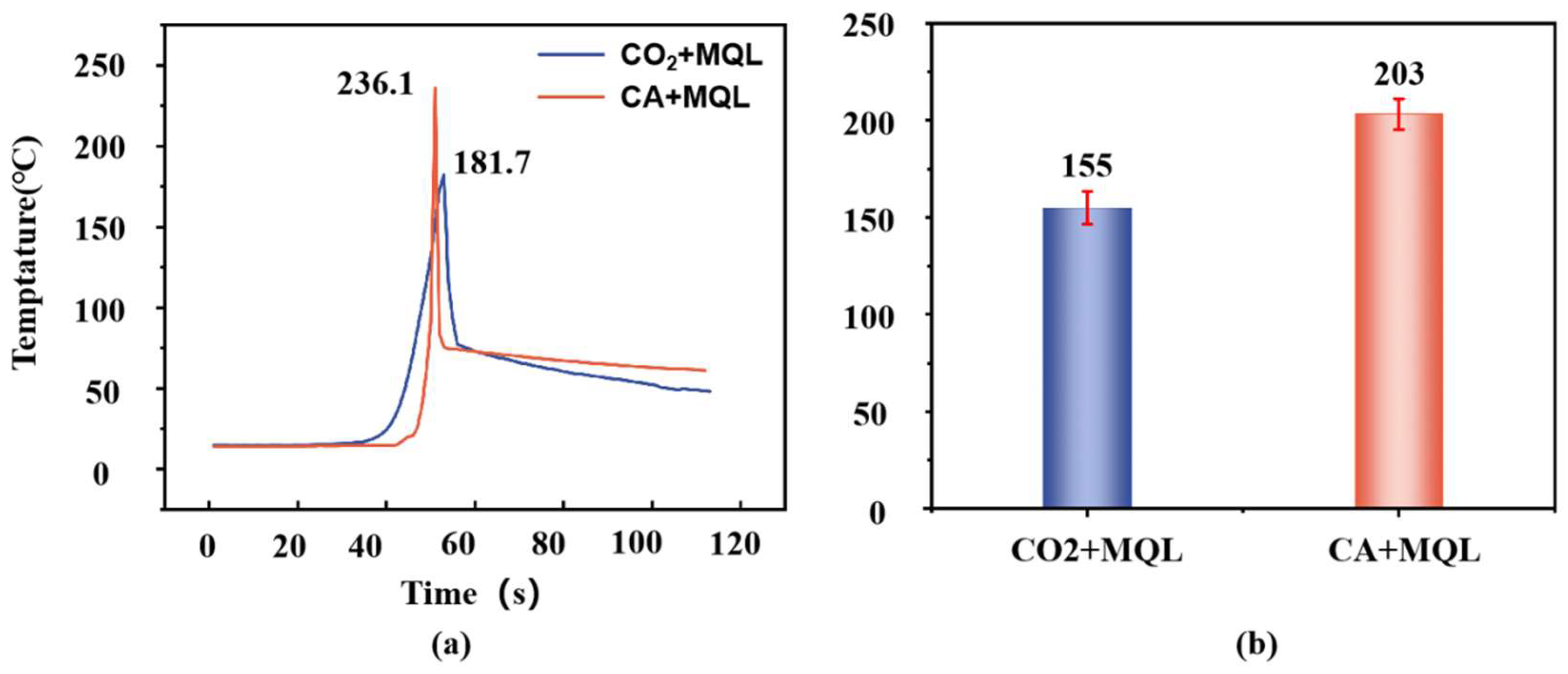

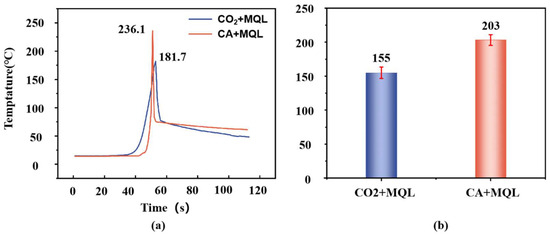

The temperature profiles measured under the two cooling conditions are presented in Figure 10a. The peak temperatures recorded for CA+MQL and LCO2+MQL conditions reached 236.1 °C and 181.7 °C, respectively. For each condition, ten temperature peaks were collected and averaged, with the initial temperature values subtracted to determine the mean temperature rise, as illustrated in Figure 10b. The results show that the average temperature rise in the workpiece surface was 203 °C under CA+MQL and 155 °C under LCO2+MQL. These findings indicate that the CA+MQL condition produces a greater average temperature increase in the cutting zone compared to LCO2+MQL. This demonstrates that when applied in CMQL technology, cryogenic CO2 exhibits superior cooling performance as a cryogenic medium.

Figure 10.

Temperature curve and average temperature rise in cutting zone under different working conditions. (a) Temperature curve. (b) Average temperature rise.

Based on the comprehensive analysis of the model calculation results and the experimental results, it is concluded that although the heat transfer coefficient of cryogenic CO2 is lower than that of cryogenic air, it has significantly higher density and lower dynamic viscosity. This high density–low viscosity physical property makes the cryogenic CO2 jet have stronger penetration ability in the cutting zone, which can effectively penetrate the micron-scale gap between the tool–workpiece and tool–chip. This not only promotes the entry of more micro-lubricants into the cutting core area, but also ensures the continuous and stable coverage of the cooling medium and lubricant at the cutting interface. In addition, the excellent permeability of CO2 in the cutting zone significantly improves the renewal rate of the flow liquid film and accelerates the heat transfer process from the cutting zone by indirectly increasing the convective heat transfer coefficient. This deep penetration characteristic is particularly important for thin-walled parts processing. It can effectively suppress the cutting vibration caused by the low stiffness characteristics of the workpiece by reducing the temperature fluctuation in the cutting zone, and improve the thermal–mechanical coupling effect in the cutting process. In contrast, although the heat transfer coefficient of cryogenic air is high, it is difficult for the cooling and lubricating medium to enter the cutting core area, which cannot effectively inhibit the heat accumulation in the cutting area, resulting in a rapid increase in the temperature of the cutting area.

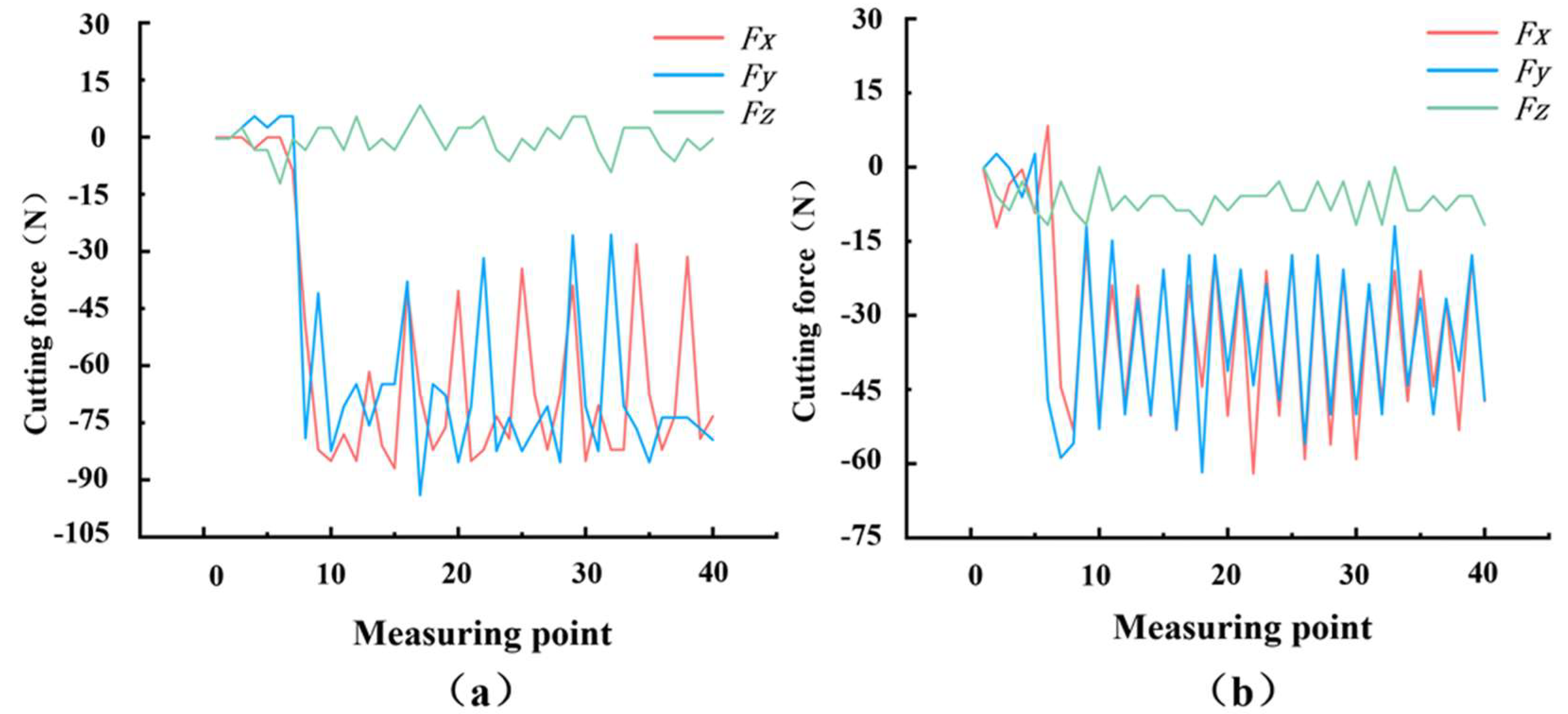

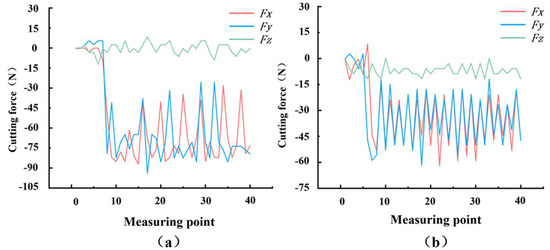

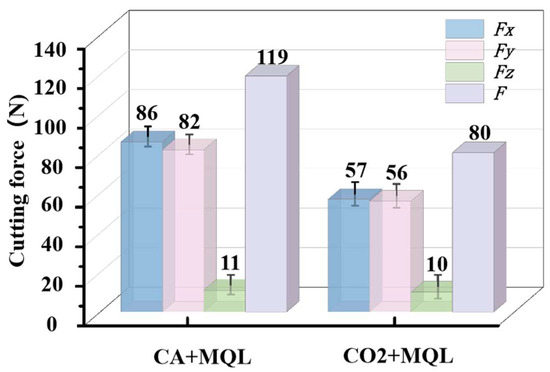

4.3. Cutting Force Analysis

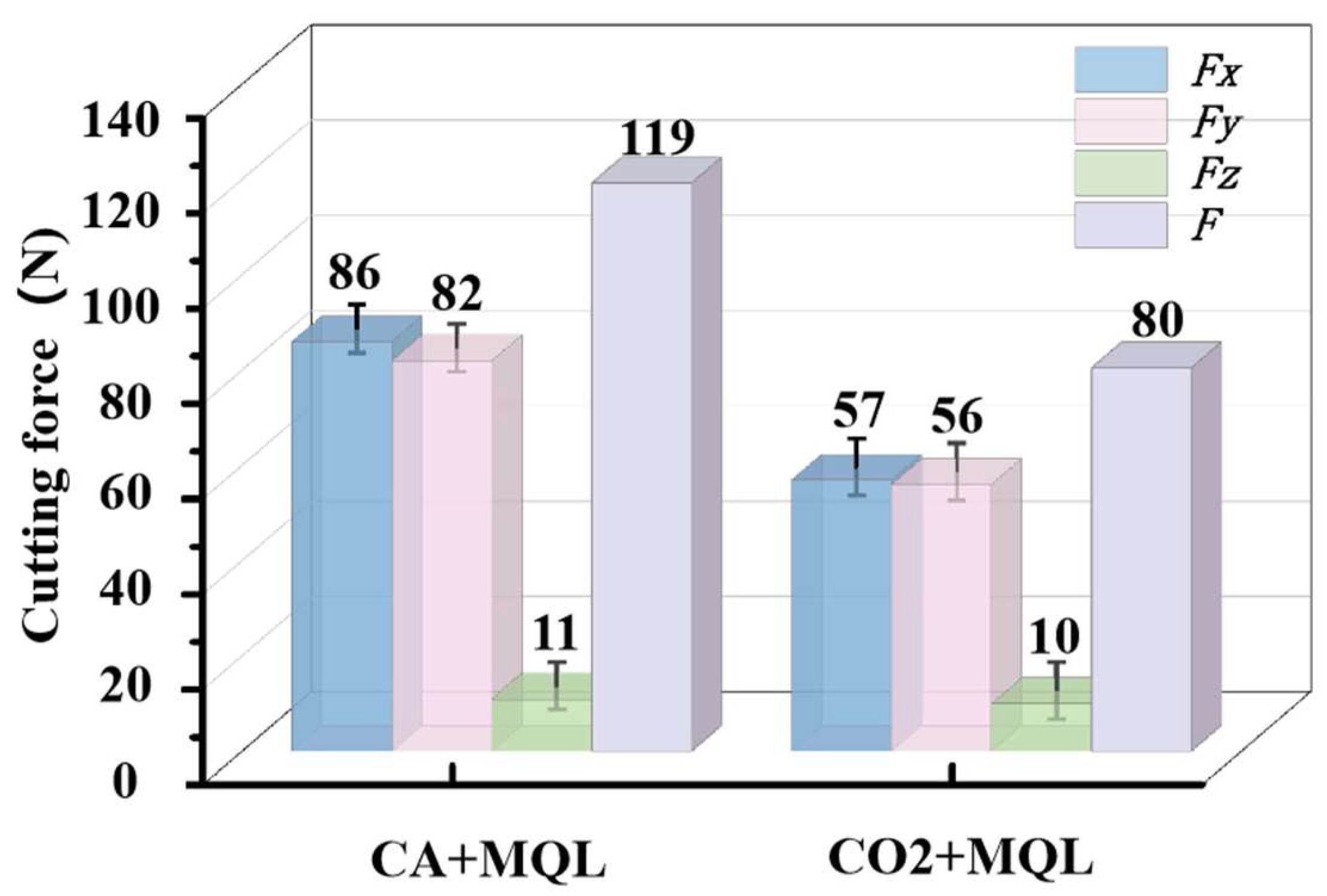

In the milling experiment of titanium alloy thin-walled parts, milling force is an important index for milling of titanium alloy thin-walled parts. It can not only reflect the performance of different cooling and lubrication methods, but also reflect the milling state of the machining process. Figure 11 is the three-way milling force under different lubrication conditions collected during the milling process. Due to the discontinuous contact between the tool and the workpiece during the milling process, the milling force shows obvious dynamic fluctuation characteristics. In this experiment, five peaks of Fi are selected from the same data segment of the milling force in each direction, and the average value is calculated and the milling force is calculated. The calculation formula is shown in Equations (15) and (16). As shown in Figure 12, compared with CA+MQL, Fx, Fy, Fz, and F under LCO2+MQL decreased by 34%, 32%, 9%, and 32.8%, respectively.

Figure 11.

Three-way milling force diagram. (a) Three-way milling force diagram under CA+MQL condition. (b) Three-way milling force diagram under LCO2+MQL condition.

Figure 12.

Three-way average milling force diagram.

The experimental results show that compared with cryogenic air, CO2 as a cryogenic medium applied to CMQL technology is beneficial to reduce the milling force. The analysis shows that under the condition of LCO2+MQL, the deep penetration characteristics of CO2 can effectively promote the uniform distribution of lubricant in the cutting core area, improve the contact state between the tool and the workpiece interface, and directly reduce the cutting force by reducing the friction coefficient. In addition, the excellent heat transfer performance of LCO2+MQL can quickly reduce the temperature of the cutting zone and reduce the thermal softening effect of titanium alloy, thereby inhibiting the material sticking and work hardening and further reducing the cutting force. In contrast, under CA+MQL conditions, the weak permeability of cryogenic air leads to insufficient cooling medium at the cutting interface. At the same time, the infiltration and spreading ability of micro-lubrication droplets in the cutting zone is poor, which not only aggravates the friction between the tool–workpiece interface, but also leads to heat accumulation in the cutting zone and increased adhesion of titanium alloy materials, eventually leading to an increase in cutting force. This difference fully reflects the decisive influence of different cooling and lubrication mechanisms of cryogenic medium on the thermal–mechanical coupling behavior in the cutting process.

4.4. Surface Quality Evaluation

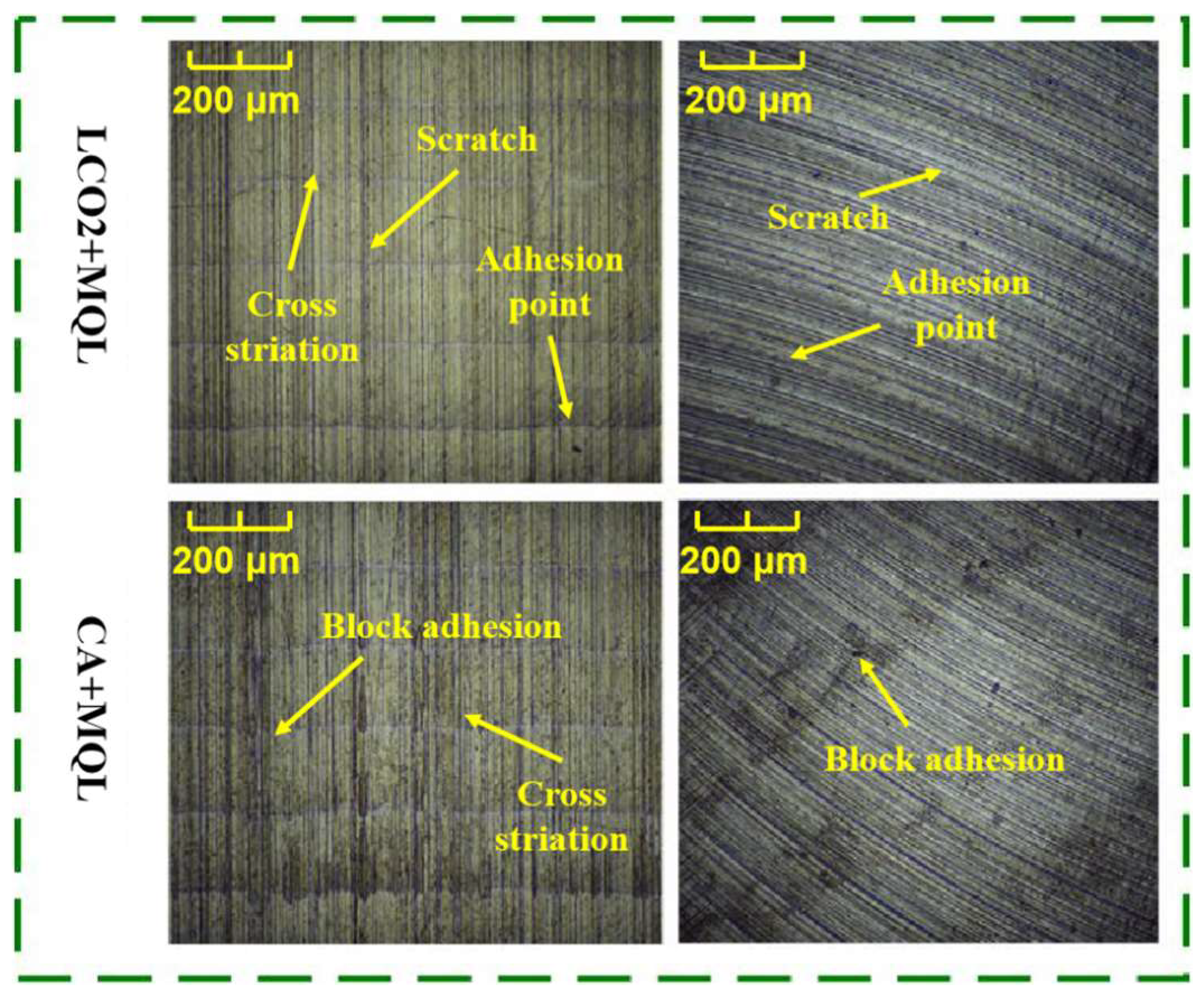

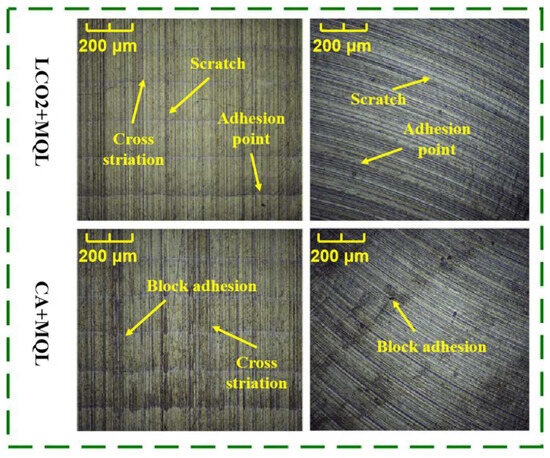

The surface morphology of the workpiece bottom and side wall under different lubrication conditions was examined using a super-depth-of-field microscope. Figure 13 shows the surface characteristics under two lubrication conditions, displaying the side wall (left) and bottom surface (right) morphologies. Observation reveals that under CA+MQL conditions, the workpiece surface exhibits large-area continuous patches and multiple granular adhesion contamination, with poor regularity in the cutting marks generated during processing. Under LCO2+MQL conditions, the surface integrity shows significant improvement, with adhesion contamination appearing only as particulate matter, reduced in both quantity and size, and the cutting marks demonstrating a more uniform distribution. Furthermore, cross striations perpendicular to the feed direction are observed under both conditions, resulting from the combined effects of intermittent cutting path superposition, minor vibrations due to insufficient workpiece rigidity, and material rebound caused by localized heat accumulation. Compared with CA+MQL, the striations formed under LCO2+MQL conditions are shallower and more regularly distributed.

Figure 13.

The surface morphology of the workpiece under two working conditions.

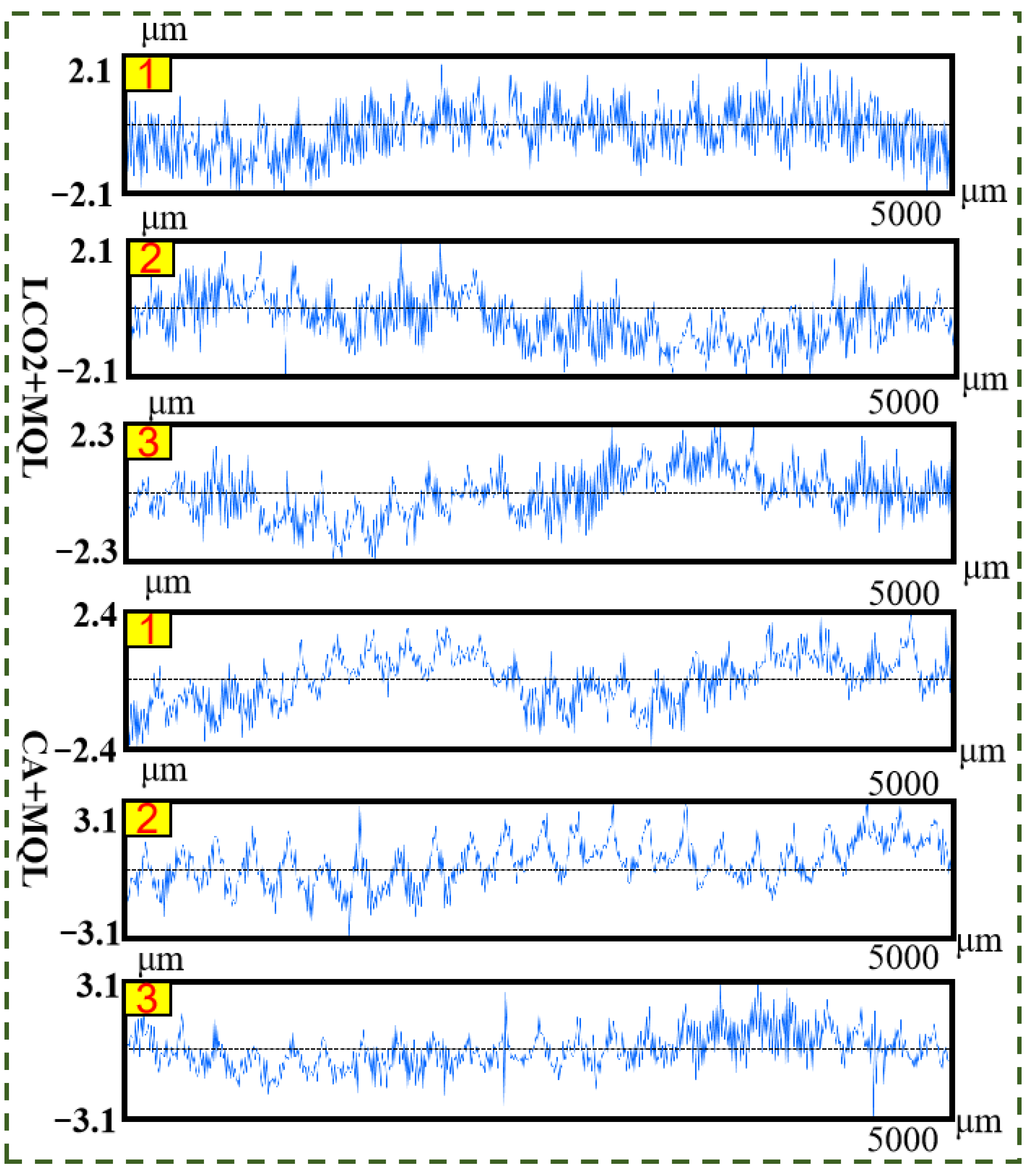

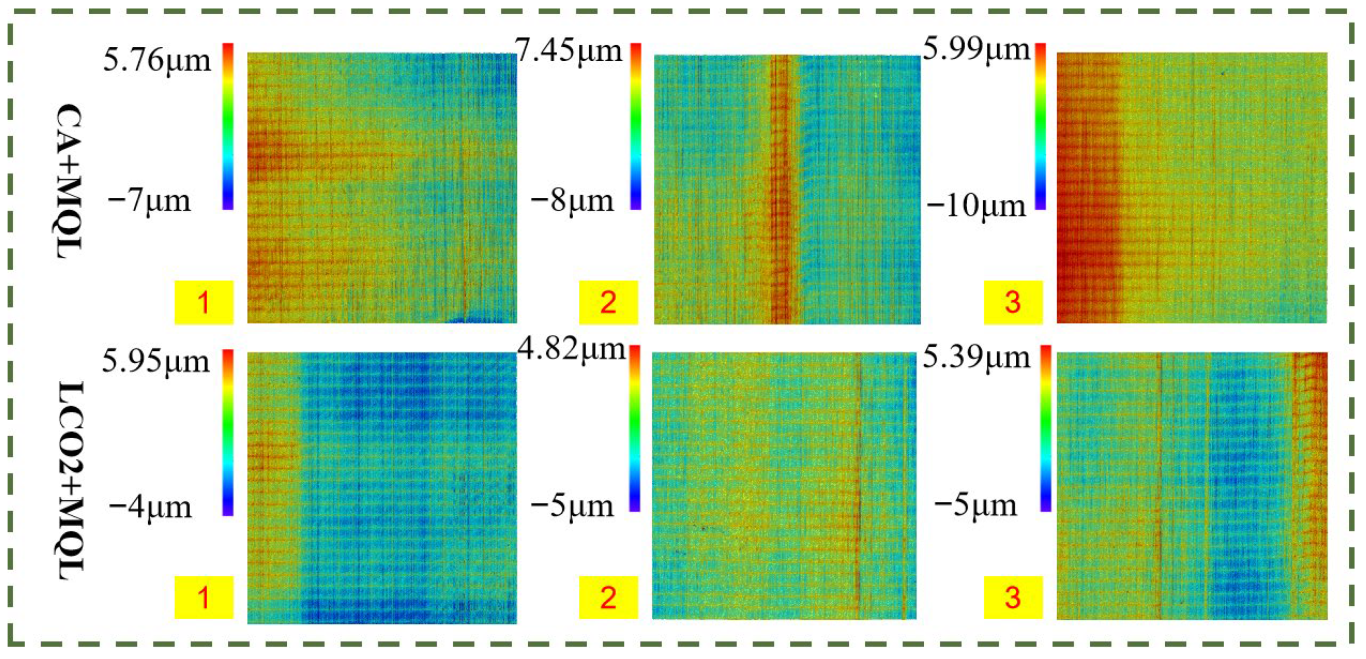

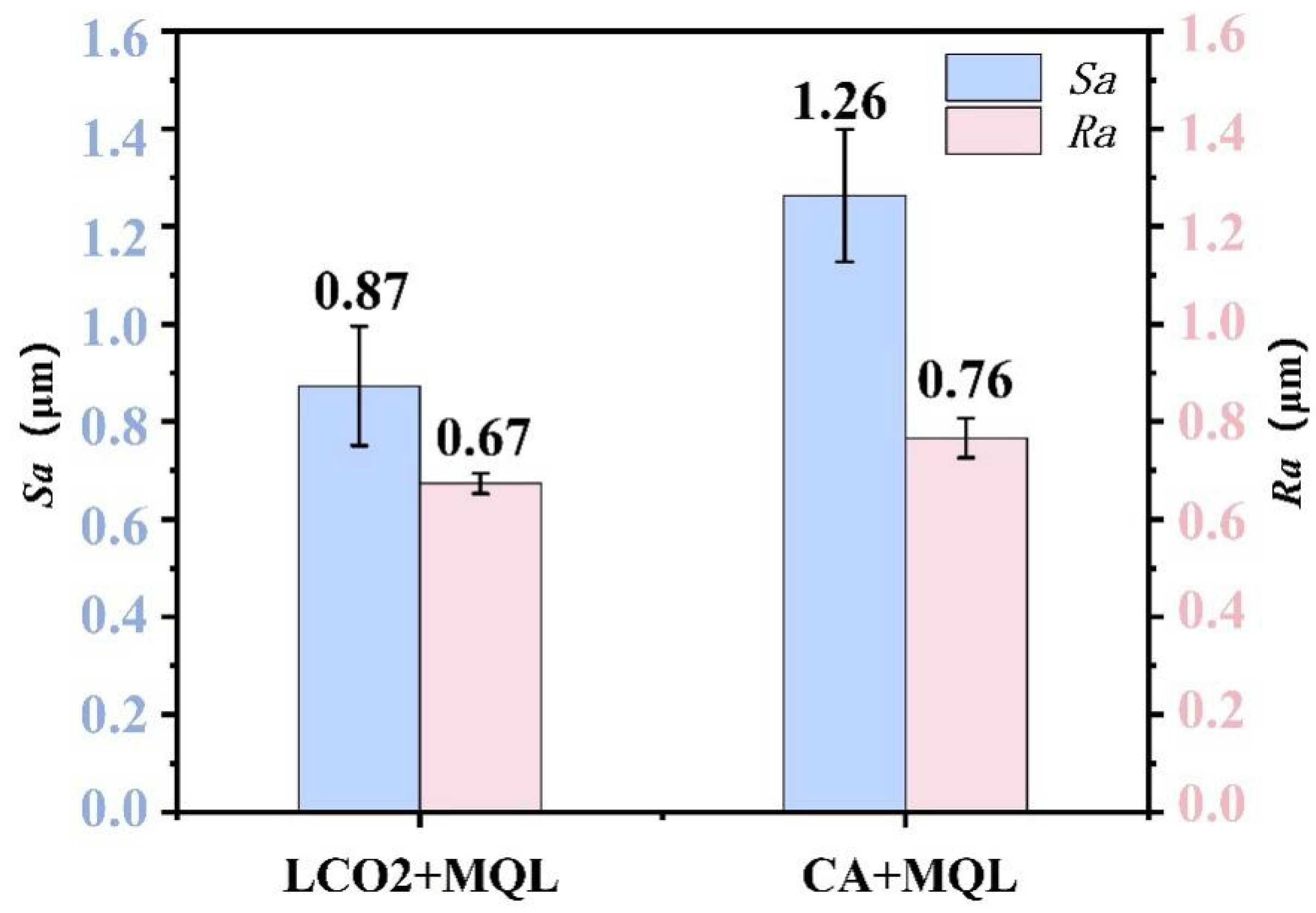

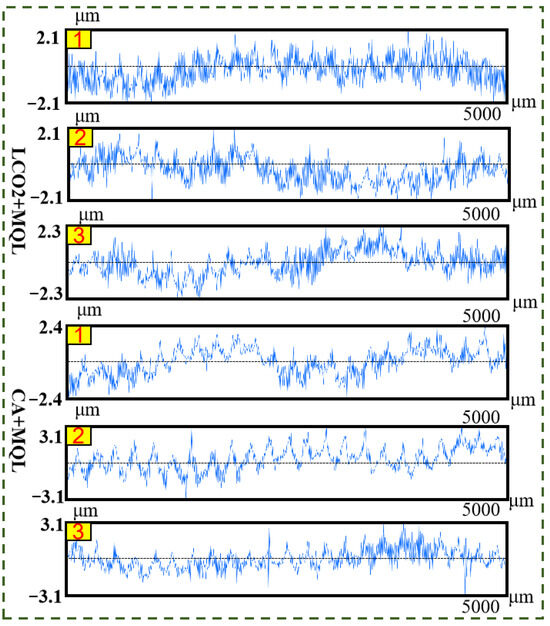

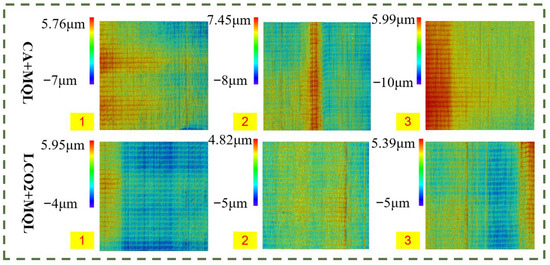

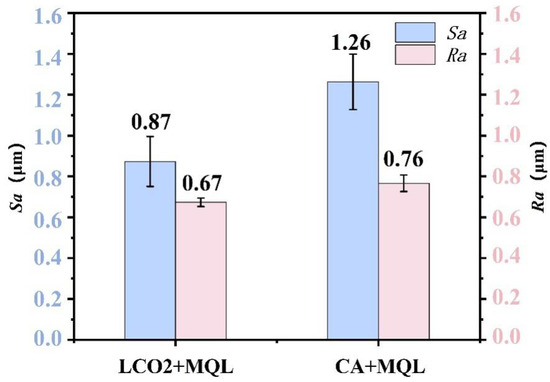

To evaluate the surface quality under different lubrication conditions, three representative samples were selected for analysis using the arithmetic mean deviation (Ra) and the three-dimensional arithmetic mean height (Sa) as evaluation parameters. The workpiece profiles and three-dimensional topographies are shown in Figure 14 and Figure 15, respectively. Results demonstrate that the surface roughness is significantly improved under LCO2+MQL conditions, with Ra and Sa values reduced by 30.9% and 11.8%, respectively, compared to CA+MQL conditions, as shown in Figure 16.

Figure 14.

The surface roughness curve of the workpiece under two working conditions.

Figure 15.

The height map of the workpiece surface under two working conditions.

Figure 16.

Average Ra and Sa of workpiece surface under two working conditions.

Based on the comprehensive analysis of surface morphology and roughness characteristics, the surface quality of workpieces processed under LCO2+MQL conditions demonstrates significant superiority over those under CA+MQL conditions. This enhancement can be attributed to the exceptional cooling and lubrication performance of LCO2+MQL, which effectively regulates cutting zone temperature, suppresses cutting force fluctuations, and mitigates thermomechanical coupling effects during machining. Furthermore, it minimizes forced vibrations induced by the low stiffness of thin-walled components, thereby ensuring process stability and substantially improving workpiece surface integrity. In contrast, the limited cooling–lubrication capacity of CA+MQL fails to adequately control heat accumulation and cutting force variations in the cutting zone, ultimately leading to surface quality deterioration.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, through the establishment of the cryogenic medium heat transfer coefficient and cutting zone penetration model, combined with the experimental verification of the system, the mechanism difference between cryogenic CO2 and cryogenic air in micro-lubrication cutting is revealed. The main conclusions are as follows:

- The heat transfer coefficient and penetration model of cryogenic air and cryogenic CO2 were established. The model results show that the cryogenic air jet has a higher convective heat transfer coefficient (907 W/m2·K), while the cryogenic CO2 has better permeability due to its high density and low viscosity. The core length, mass flow rate, and mass transfer efficiency of the jet are 16.5%, 31.8%, and 22.9% higher than those of the cryogenic air, respectively. This finding clarifies that the permeability is the key factor to determine the cooling and lubrication effect, which makes up for the lack of attention to the mechanism of medium transport behavior in previous studies.

- The effects of different pour point depressants on the viscosity of lubricants were systematically evaluated. It was found that T801 had a significant pour point depression effect at low temperature, but the optimum addition amount was 3%. Excessive use will cause flocculent precipitation. This study provides an experimental basis for the selection of CMQL lubricants, and also lays a foundation for subsequent lubricant modification research.

- Through cutting experiments, it is found that the average temperature rise in the workpiece surface and cutting force under the condition of LCO2+MQL are 23.6% and 32.8% lower than those of CA+MQL, respectively. This result is highly consistent with the model prediction, which confirms that the superior permeability is the internal mechanism for the better process performance of cryogenic CO2, and strengthens the correlation between the model and the experiment.

- The surface morphology analysis shows that the surface adhesion contamination of the workpiece is significantly reduced under the LCO2+MQL condition, and the surface roughness Sa and Ra are reduced by 30.9% and 11.8%, respectively. This shows that the improvement of penetration ability directly improves the distribution effect of lubricant in the cutting area, thus improving the surface quality.

- This study mainly focuses on the cutting process of Ti-6Al-4V titanium alloy thin-walled parts at −30 °C, which can be extended to other difficult-to-cut materials and multi-temperature conditions in the future. It is suggested that the follow-up study should directly observe the jet behavior through high-speed photography, and develop a dynamic temperature field monitoring method to further improve the theoretical system of the mechanism of cryogenic media.

Author Contributions

Z.H.: investigation, writing (original draft), and writing (review and editing); D.J.: technical and material support, instructional support, and writing (review); Q.G.: collect and organize data, and writing (review and editing); X.W.: formal analysis, validation; L.W.: formal analysis, validation; Y.F.: modify paper, formal analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Liaoning Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2024-BS-239); Basic Research Project of Liaoning Provincial Department of Education for Universities (LJ212410154018); Liaoning Provincial Science and Technology Program Project (Grant No. 2023JH1/10400074); Inner Mongolia Natural Science Foundation (2025MS05062); and Shandong Province Higher Education Institutions Youth Innovation Team Project (2023KJ116).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the reviewers of this paper for their comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, L.; Xu, Q.F.; Yang, H.Y.; Yang, Y.; Cao, Z.H.; Guo, D.Z.; Ji, V. Design and Rate Control of Large Titanium Alloy Springs for Aerospace Applications. Aerospace 2024, 11, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.J.; To, S.; Zhu, Z.W.; Yin, T.F. A theoretical and experimental investigation of cutting forces and spring back behaviour of Ti6Al4V alloy in ultraprecision machining of microgrooves. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2020, 169, 105315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.J.; Peng, Y.Y.; Zuo, Y.J. Ultrasonic impact surface strengthening treatment and fatigue behaviors of titanium alloy thin-walled open hole components. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2024, 307, 110292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.P.; Pan, X.L.; Zhang, X.B.; Meng, S.P.; He, P.; Yu, Z.C.; Xie, C.C.; Zhou, L.C. Effect of femtosecond laser shock peening on surface integrity and fatigue property of ultra-thin-walled Ti6Al4V. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 192, 113439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Li, C.H.; Zhang, Y.B.; Said, Z.; Debnath, S.; Sharma, S.; Ali, H.M.; Yang, M.; Gao, T.; Li, R.Z. Grindability of titanium alloy using cryogenic nanolubricant minimum quantity lubrication. J. Manuf. Process 2022, 80, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.Y.; Wei, T.; Li, S.P.; Li, G.X.; Ding, S.L. Multi-Channel Electrical Discharge Machining of Ti-6Al-4V Enabled by Semiconductor Potential Differences. Micromachines 2025, 16, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Li, G.X.; Pan, W.C.; Wang, X.; Ding, S.L. A prediction model for the milling of thin-wall parts considering thermal-mechanical coupling and tool wear. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 107, 4645–4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Q.L.; Rong, L.; Jing, L.; Gao, H.; Tang, S.W.; Qiu, X.Y.; Liu, L.P.; Wang, X.H.; Dai, F.P. Study on force-thermal characteristics and cutting performance of titanium alloy milled by ultrasonic vibration and minimum quantity lubrication. J. Manuf. Process 2023, 95, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanikumar, K.; Boppana, S.B.; Natarajan, E.; Natarajan, E. Analysis of chip formation and temperature measurement in machining of titanium alloy (Ti-6Al-4V). Exp. Techniques 2023, 47, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.L.; Wang, Q.H.; Zhu, B.; Wang, B.D.; Zhu, W.M.; Du, J.M.; Sun, B.C. Experimental study on thermal deformation suppression and cooling structure optimization of double pendulum angle milling head. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 127, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.Z.; Wang, Y.; LI, Y.X. Design and Finite Element Analysis of an Internal Cooling Tool. Mech. Res. Appl. 2024, 37, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, N.R.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Ahmed, M. Effect of minimum quantity lubrication (MQL) on tool wear and surface roughness in turning AISI-4340 steel. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2006, 172, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.H.; Yao, Y.; Wu, B.F.; Zhao, B.; Ding, W.F.; Muhammad, J.; Ahmar, K.; Asra, B.; Liu, Q.; Xu, D. Recent developments in MQL machining of aeronautical materials: A comparative review. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2025, 38, 102918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.P.; Ding, C.L.; Shi, R.X.; Liu, R.H. Optimization of technological parameters and application conditions of CMQL in high-speed milling 300M steel. Integr. Ferroelectr. 2021, 217, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Zhang, W.K.; Zhang, X.N.; Li, X.K.; Ju, L.Y.; Gu, T.P. Research on Tool Wear and Machining Characteristics of TC6 Titanium Alloy with Cryogenic Minimum Quantity Lubrication (CMQL) Technology. Processes 2024, 12, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, D.M.; Sabarish, V.N.; Hariharan, M.; Raj, D.S. On the benefits of sub-zero air supplemented minimum quantity lubrication systems: An experimental andmechanistic investigation on end milling of Ti-6-Al-4-V alloy. Tribol. Int. 2018, 119, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; He, N.; Li, L. Effect of cryogenic minimum quantity lubrication (CMQL) on cutting temperature and tool wear in high-speed end milling of titanium alloys. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2010, 34, 1816–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.P.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Ren, Y.; Shay, T.; Liu, G.L. Simulation and experiments on cutting forces and cutting temperature in high speed milling of 300M steel under CMQL and dry conditions. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2018, 19, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Li, G.X.; Pan, W.C.; Izamshah, R.; Wang, X.; Ding, S.L. Experimental investigation of eco-friendly cryogenic minimum quantity lubrication (CMQL) strategy in machining of Ti–6Al–4V thin-wall part. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 357, 131993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Yang, Y.G. Effect of cryogenic minimum quantitylubrication on machinability of diamond tool in ultraprecision turning of 3Cr2NiMo steel. Mater. Manuf. Process 2018, 33, 943–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.Z.; Li, C.H.; Zhang, Y.B.; Yang, M.; Cui, X.; Li, B.K.; Gao, T.; Wang, D.Z.; An, Q.L. Heat Transfer Mechanism and Convective Heat Transfer Coefficient Model of Cryogenic Air Minimum Quantity Lubrication Grinding Titanium Alloy. J. Mech. Eng. 2023, 59, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.A.; Pombo, I.; Alberdi, R.; Izquierdo, B.; Ortega, N.; Plaza, S.; Martinez-Toledano, J. Machining evaluation of a hybrid MQL-CO2 grinding technology. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1840–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grguraš, D.; Sterle, L.; Pušavec, F. Cutting forces and chip morphology in LCO2 + MQL assisted robotic drilling of Ti6Al4V. Proc. CIRP 2021, 102, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, D.; Hanenkamp, N. Energy efficiency assessment of cryogenic minimum quantity lubrication cooling for milling operations. Proc. CIRP 2021, 98, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, O.; Rodríguez, A.; Fernández-Abia, A.I.; Barreiro, J.; Lopez de Lacalle, L.N. Cryogenic and minimum quantity lubrication for an eco-efficiency turning of AISI304. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 139, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohsenow, W.M.; Hartnett, J.P.; Ganic, E.N. Handbook of Heat Transfer Applications; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Jamil, M.; Khan, A.M.; Gupta, M.K.; Mia, M.; He, N.; Li, L.; Sivalingam, V.K. Influence of CO2-snow and subzero MQL on thermal aspects in the machining of Ti-6Al-4V. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 177, 115480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sofyani, S.; Marinescu, I.D. Analytical modeling of the thermal aspects of metalworking fluids in the milling process. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 92, 3953–3966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.W.; Law, A.W. Second-order integral model for a round turbulent buoyant jet. J. Fluid Mech. 2002, 459, 397–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.B.; Li, C.H.; Yang, M.; Jia, D.Z.; Wang, Y.G.; Li, B.K.; Hou, Y.L.; Zhang, N.Q.; Wu, Q.D. Experimental evaluation of cooling performance by friction coefficient and specific friction energy in nanofluid minimum quantity lubrication grinding with different types of vegetable oil. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 139, 685–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.M.; Li, C.H.; Zhang, Y.B.; Wang, Y.G.; Li, B.K.; Yang, M.; Zhang, X.P.; Liu, G.T. Experimental evaluation of the lubrication performance of mixtures of castor oil with other vegetable oils in MQL grinding of nickel-based alloy. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 140, 1060–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).