Numerical Simulation of Temperature Field, Velocity Field and Solidification Microstructure Evolution of Laser Cladding AlCoCrFeNi High Entropy Alloy Coatings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials Properties

2.2. Laser Cladding Test and Characterization

2.3. Sample Characterization Versus Performance Analysis

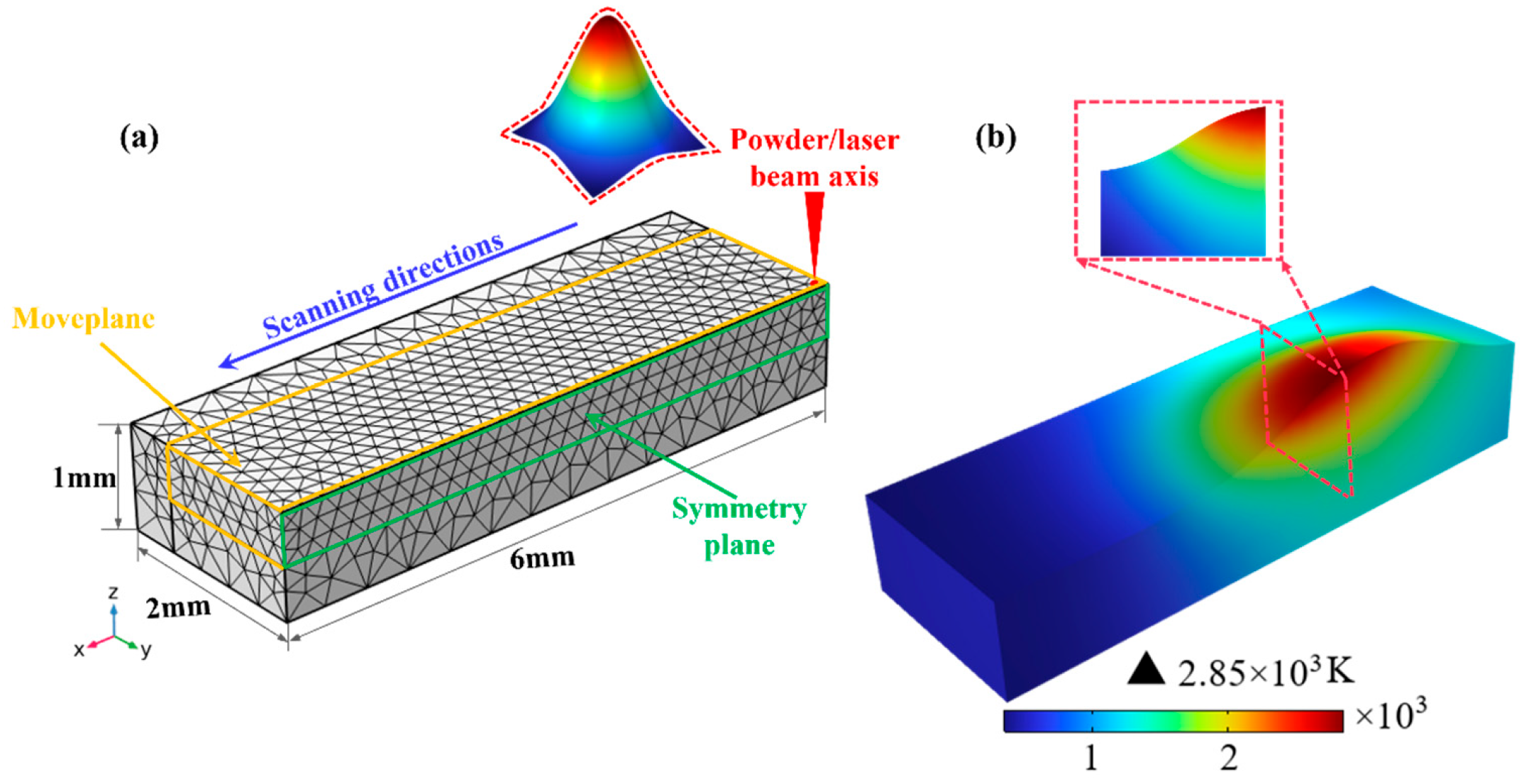

2.4. Simulation

- The laser heat input is assumed to follow a Gaussian distribution, and the heat is directly applied to the surface of the melt pool.

- It is assumed that all powder particles entering the melt pool fully participate in the formation of the coating.

- The heat flux for heating the powder and the heat loss due to evaporation are neglected.

- The fluid flow in the melt pool is assumed to be incompressible, Newtonian, and laminar, with no consideration of the effects of the carrier gas or shielding gas on the melt pool.

- The mushy zone, defined as the region where the temperature lies between the solidus and liquidus, is modeled as a porous medium with isotropic permeability.

- It is assumed that there is no diffusion in the solid phase, meaning that the solidified material does not contribute to mass transfer by diffusion.

- The concentration distribution of the powder is assumed to follow a Gaussian distribution, and any powder falling into the melt pool is immediately melted.

- The attenuation of laser energy through the powder flow is neglected.

2.4.1. Governing Equations

Phase-Change Heat-Transfer

Fluid Flow Model

2.4.2. Initial and Boundary Conditions

3. Results

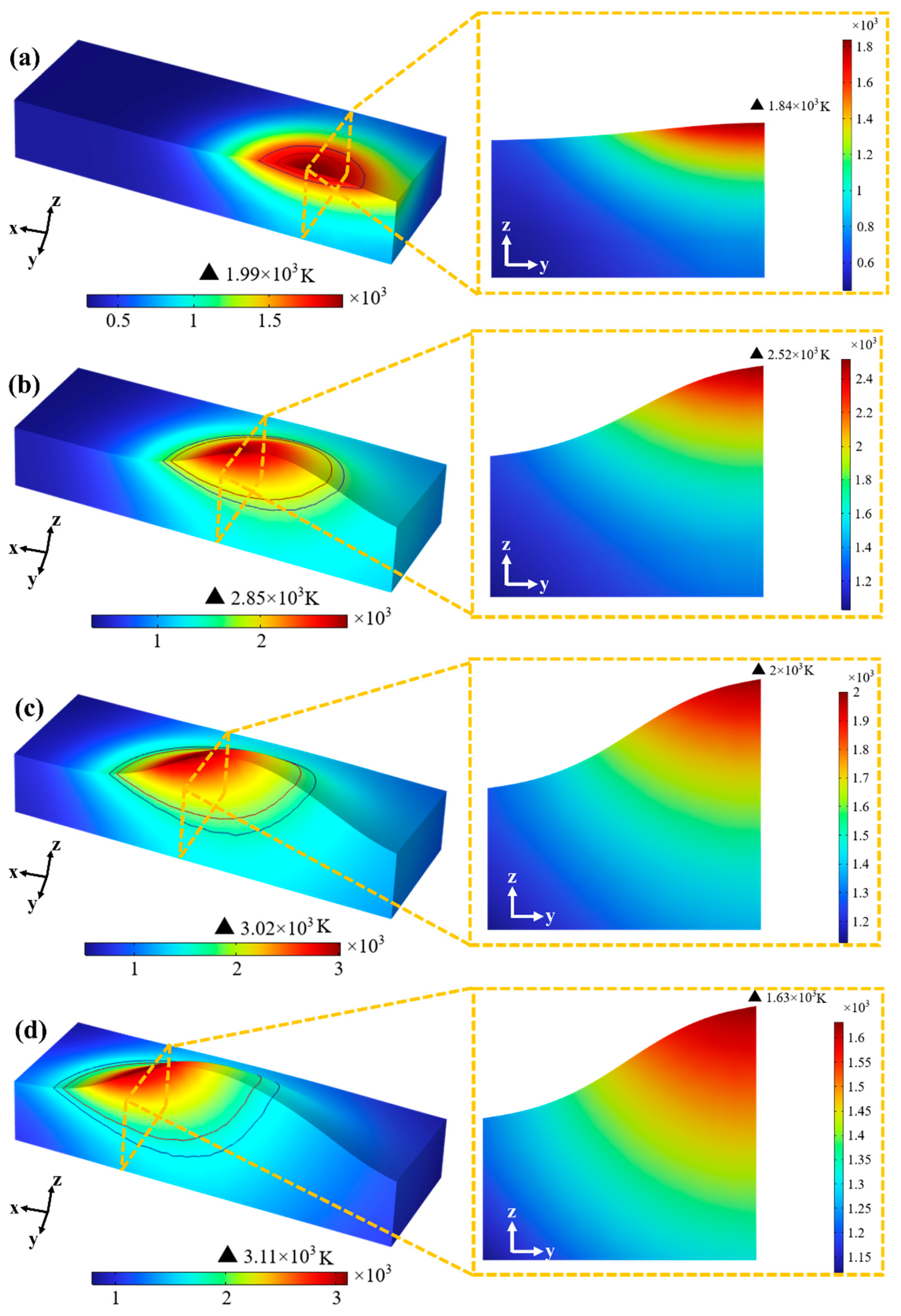

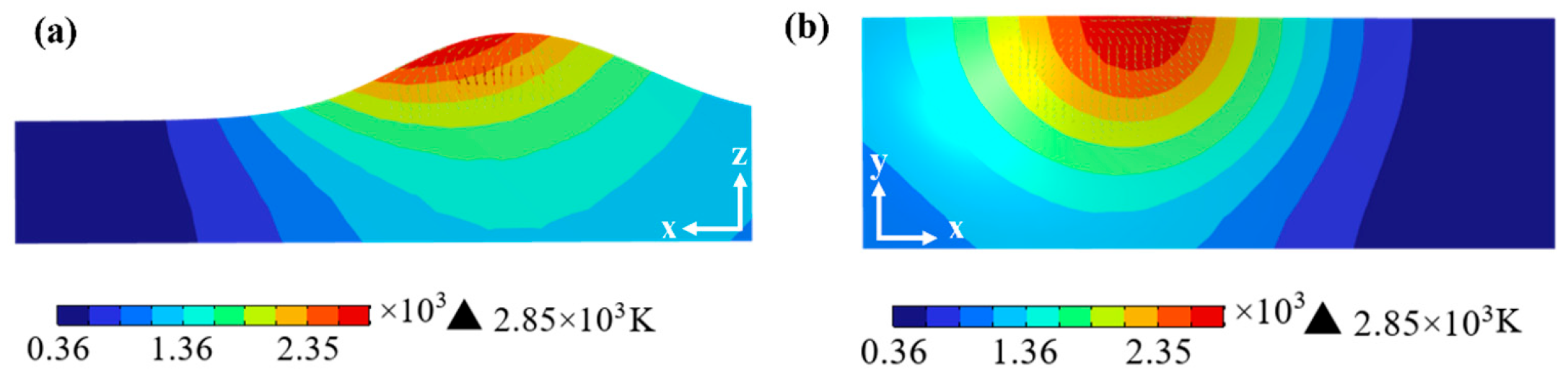

3.1. Thermal History and Velocity Field

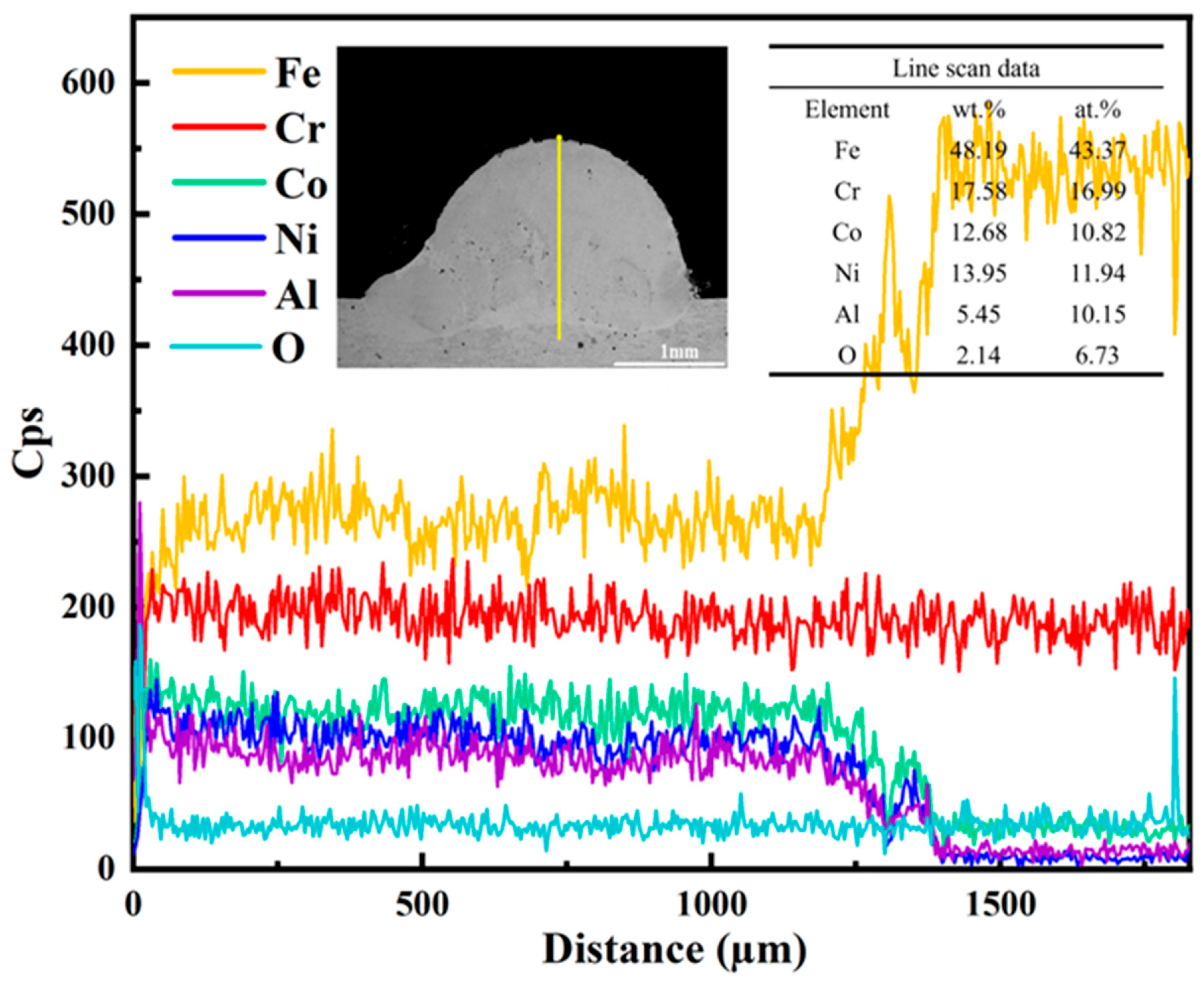

3.2. Verification of Model

3.3. Pool Solidification Behavior

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The simulated geometric characteristics of the coating exhibit good agreement with experimental measurements, showing relative errors of 4.94% (W), 17.35% (H), and 17.36% (h), respectively, which verifies the reliability of the model. Furthermore, the simulation reveals a transition in melt pool dynamics from conduction-dominated (Pet < 5, hemispherical shape) to Marangoni convection-dominated (Pet > 50, elliptical shape). The peak temperature reaches 2850 K with a maximum flow velocity of 2.31 mm/s. The temperature and flow fields are strongly coupled, where Marangoni convection significantly promotes efficient mixing and degassing.

- (2)

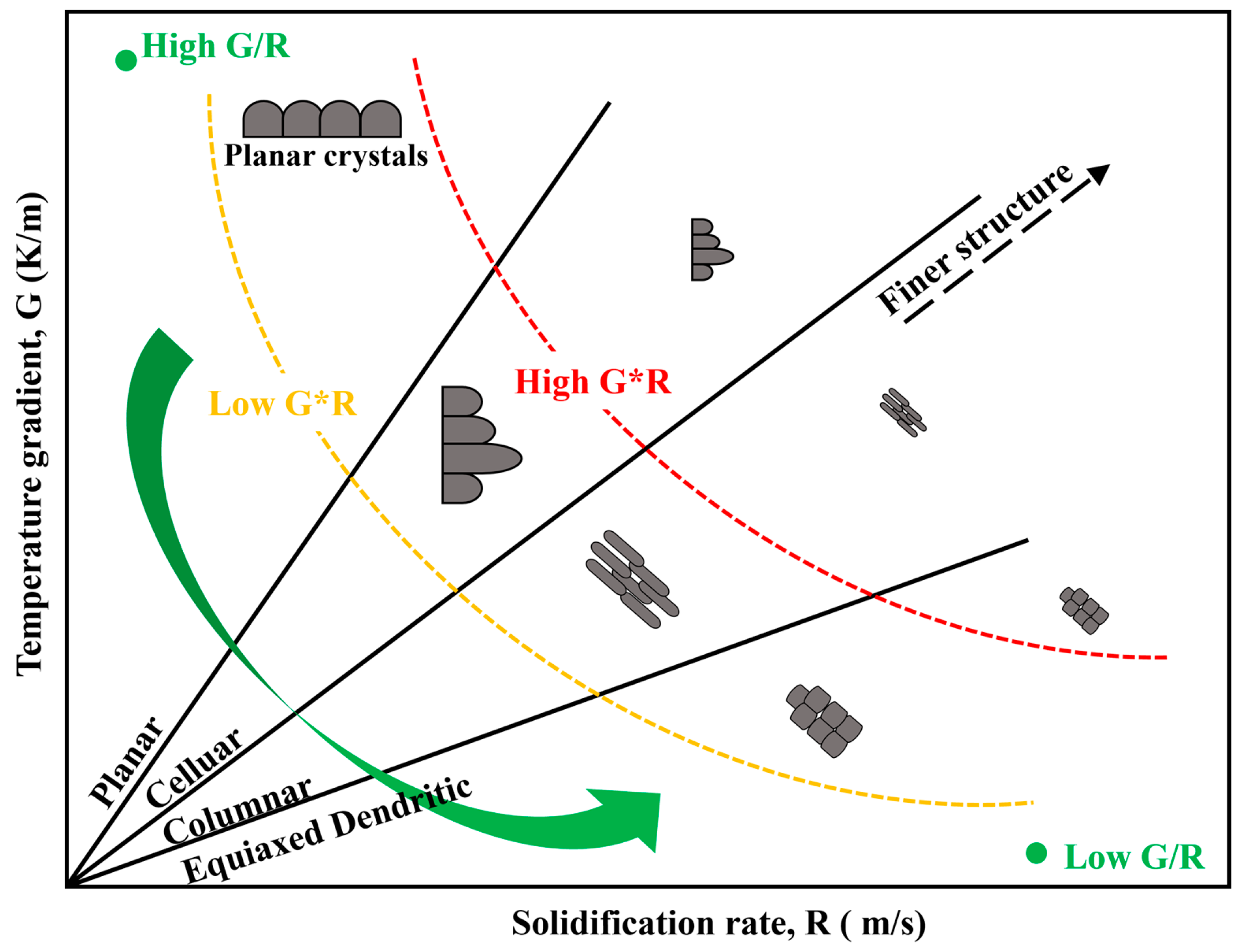

- Numerical simulations were performed to investigate the evolution of solidification parameters (G and R) during LMD. Results showed that the temperature gradient (G) peaked at 1.8 × 105 K/m at the bottom of the coating and decreased towards the top. Conversely, the solidification rate (R) exhibited an inverse trend, increasing to a maximum of 0.018 m/s at the surface. Consequently, the resulting cooling rate (G*R) profile led to grain coarsening along the build direction.

- (3)

- The microstructure evolution was governed by the G/R ratio, creating a gradient from 3.22 × 106 to 3.02 × 107 s·K·m−2. This variation caused the morphology to evolve from planar to cellular and finally equiaxed dendrites from the interface upwards. SEM analysis validated this trend and indicated that grain refinement was driven by increasing cooling rates (G*R). Crucially, the accumulation of constitutional undercooling ahead of the columnar interface promoted the nucleation of equiaxed grains, leading to a distinct CET behavior.

- (4)

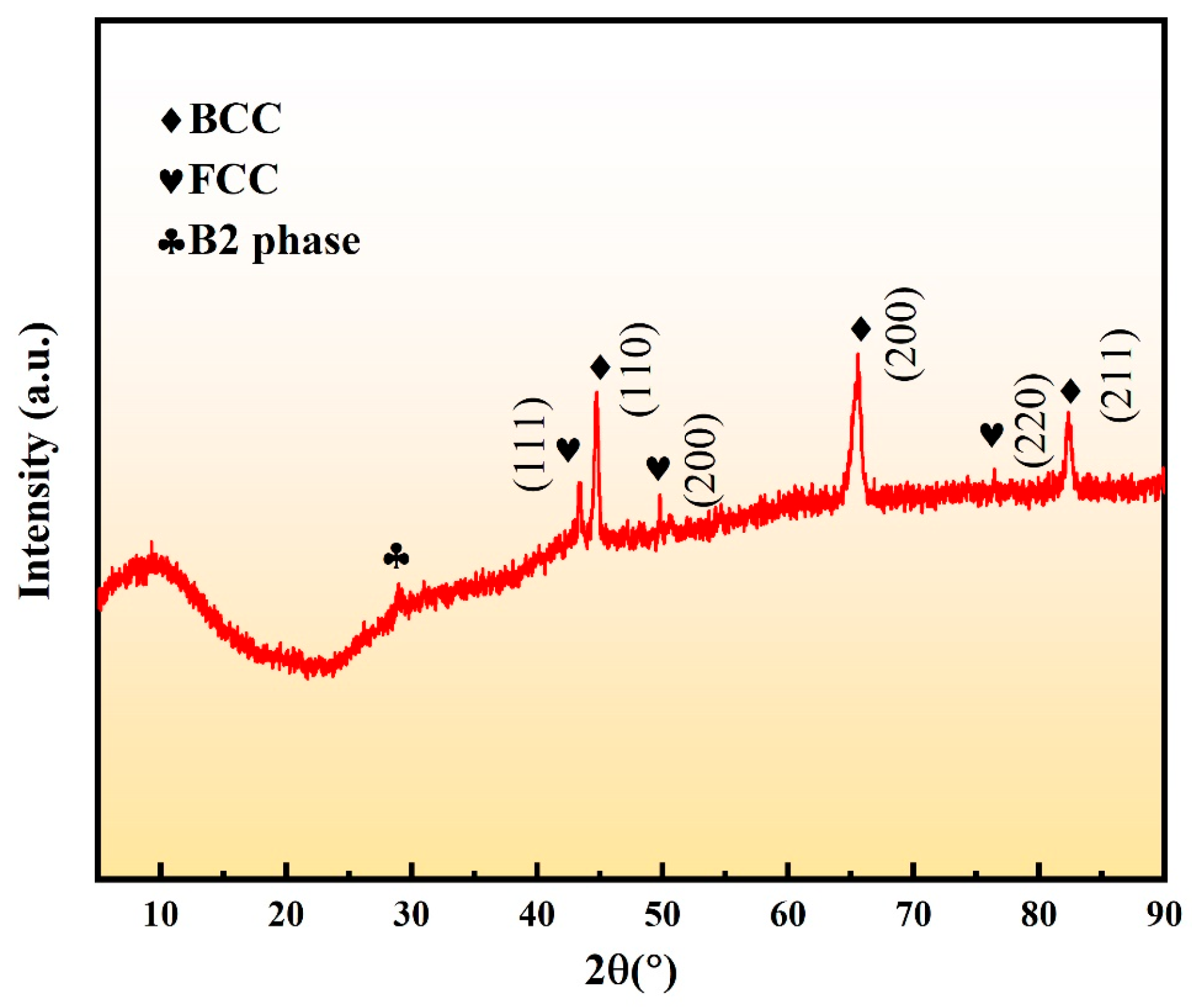

- XRD analysis revealed that the AlCoCrFeNi HEAs coating primarily consists of BCC, FCC, and ordered B2 phases, with FCC phase forming during rapid heating and BCC phase stabilizing during cooling. High-quality, defect-free coatings were successfully fabricated due to sufficient energy input maintaining elevated temperatures (>2800 K) for effective gas escape. As a result, the functionally graded microstructure can achieve enhanced surface properties while ensuring strong substrate bonding.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Odetola, P.I.; Babalola, B.J.; Afolabi, A.E.; Anamu, U.S.; Olorundaisi, E.; Umba, M.C.; Phahlane, T.; Ayodele, O.O.; Olubambi, P.A. Exploring high entropy alloys: A review on thermodynamic design and computational modeling strategies for advanced materials applications. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, E.P.; Raabe, D.; Ritchie, R.O. High-entropy alloys. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2019, 4, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, R.; Bajpai, A.; Biswas, K. A critical review on mechanical alloying of high-entropy materials. High Entropy Alloys Mater. 2025, 3, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.-W.; Chen, S.K.; Lin, S.-J.; Gan, J.-Y.; Chin, T.-S.; Shun, T.-T.; Tsau, C.-H.; Chang, S.-Y. Nanostructured high-entropy alloys with multiple principal elements: Novel alloy design concepts and outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2004, 6, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, B.; Chang, I.T.H.; Knight, P.; Vincent, A.J.B. Microstructural development in equiatomic multicomponent alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 375–377, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, H.; Abedi, H.R.; Zhang, Y. A study on outstanding high-temperature wear resistance of high-entropy alloys. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2023, 25, 2201915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, V.M.; Arulvel, S. A review on the steels, alloys/high entropy alloys, composites and coatings used in high temperature wear applications. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 43, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Fu, H. Improvement of high temperature wear resistance of laser-cladding high-entropy alloy coatings: A review. Metals 2024, 14, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Li, K.; Zhao, G.-L.; Guo, S.M. Electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness of high entropy AlCoCrFeNi alloy powder laden composites. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 734, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, K.; Davies, C.; Wu, X. Evolution of microstructure, mechanical and corrosion properties of AlCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy prepared by direct laser fabrication. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 694, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochvíl, P.; Průša, F.; Thürlová, H.; Strakošová, A.; Karlík, M.; Čech, J.; Haušild, P.; Čapek, J.; Ekrt, O.; Jarošová, M.; et al. The role of the preparation route on microstructure and mechanical properties of AlCoCrFeNi high entropy alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 4248–4260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraji, A.; Farvizi, M.; Ebadzadeh, T.; Kim, H.S. Microstructure, wear performance, and mechanical properties of spark plasma-sintered AlCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy after heat treatment. Intermetallics 2022, 149, 107656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ding, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; He, P.; Narayanan, J.A.; Du, S.; Zhou, L. Evolution of microstructure and properties of AlCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy coatings fabricated at different laser power levels. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 46, 112644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Xing, Y.; Dong, E.; Zhao, L.; Liu, H.; Chang, T.; Chen, M.; Wang, J.; Lu, J.; Wan, J. An overview of laser metal deposition for cladding: Defect formation mechanisms, defect suppression methods and performance improvements of laser-cladded layers. Materials 2022, 15, 5522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Chen, Y.; Liou, F. Additive manufacturing of functionally graded metallic materials using laser metal deposition. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 31, 100901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayatnejad, R.; Sabet, H.; Rahmati, S.; Golezani, A.S. Investigation of additive manufacturing process by LMD method, affecting process parameters on microstructure and quality of deposition layers. J. Environ. Friendly Mater. 2021, 5, 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, D.D.; Meiners, W.; Wissenbach, K.; Poprawe, R. Laser additive manufacturing of metallic components: Materials, processes and mechanisms. Int. Mater. Rev. 2012, 57, 133–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selcuk, C. Laser metal deposition for powder metallurgy parts. Powder Metall. 2011, 54, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrzanski, L.; Jonda, E.; Lukaszkowicz, K.; Labisz, K.; Klimpel, A. Surface modification of the X40CrMoV5-1 steel by laser alloying and PVD coatings deposition. J. Achiev. Mater. Manuf. Eng. 2008, 27, 179–182. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, S.; Wu, C.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Abdullah, A.O. Design, preparation, microstructure and properties of novel wear-resistant stainless steel-base composites using laser melting deposition. Vacuum 2019, 165, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Song, J.; Li, W.; Ma, Z.; Liu, H.; Liu, B.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, F. Research progress on structure and performance of metal (steel and titanium) matrix composite materials manufactured by laser additive manufacturing: A review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 140, 4643–4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Gong, S.; Xu, H.; Chen, W.; Wang, Z.; Yang, G.; Qi, B. In-situ multi-principal element alloying of equiaxed and lamellar tial alloys via electron beam freeform fabrication with dual-wire synergistic control. SSRN Sch. Pap. 2024, 4830412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Lu, C.; Fu, Y.; Ye, X.; Song, L. Progress on experimental study of melt pool flow dynamics in laser material processing. In Liquid Metals; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Z.; Yu, G.; He, X.; Li, S. Numerical simulation of thermal behavior and multicomponent mass transfer in direct laser deposition of Co-base alloy on steel. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2017, 104, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Attia, H. Current status and future direction in the numerical modeling and simulation of machining processes: A critical literature review. Mach. Sci. Technol. 2010, 14, 149–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.; Tiwari, B.; Sun, D.-W. Computational fluid dynamics in the design and analysis of thermal processes: A review of recent advances. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzepieciński, T.; Dell’Isola, F.; Lemu, H.G. Multiphysics modeling and numerical simulation in computer-aided manufacturing processes. Metals 2021, 11, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picasso, M.; Hoadley, A.F.A. Finite element simulation of laser surface treatments including convection in the melt pool. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow 1994, 4, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Mazumder, J.; Ki, H. Numerical simulation of heat transfer and fluid flow in coaxial laser cladding process for direct metal deposition. J. Appl. Phys. 2006, 100, 24903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Zhang, R.; Li, Z.; Jiang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yin, H.; Qu, X. An integrated multiscale model to study the marangoni effect on molten pool and microstructure evolution. Integr. Mater. Manuf. Innov. 2023, 12, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yu, G.; He, X.; Li, S.; Shu, Z. Surface tension-driven flow and its correlation with mass transfer during L-DED of Co-based powders. Metals 2022, 12, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, C.; Markl, M.; Koepf, J.A. Modeling and simulation of microstructure evolution for additive manufacturing of metals: A critical review. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2020, 51, 4970–4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, H.; Williams, M.; Levine, L.; Ramazani, A. Integrating phase field modeling and machine learning to develop process-microstructure relationships in laser powder bed fusion of IN718. Metall. Microstruct. Anal. 2024, 13, 983–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhao, J. Process parameters optimization and numerical simulation of AlCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy coating via laser cladding. Materials 2024, 17, 4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, H.; Chen, X.; Yan, Z.; Zhi, X.; Yang, Q.; Yuan, Z. Finite-element simulation of melt pool geometry and dilution ratio during laser cladding. Appl. Phys. A 2019, 125, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, E.R.; Doria, C.C.; Ocaña, J.L.; Istrate, B.; Cimpoesu, N.; Baltes, L.S.; Stanciu, E.M.; Croitoru, C.; Pascu, A.; Munteanu, C.; et al. Morphological analysis of laser surface texturing effect on AISI 430 stainless steel. Materials 2022, 15, 4580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jie, D.; Wu, M.; He, R.; Cui, C.; Miao, X. A multiphase modeling for investigating temperature history, flow field and solidification microstructure evolution of FeCoNiCrTi coating by laser cladding. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 169, 110197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okunkova, A.; Volosova, M.; Peretyagin, P.; Vladimirov, Y.; Zhirnov, I.; Gusarov, A. Experimental approbation of selective laser melting of powders by the use of non-gaussian power density distributions. Phys. Procedia 2014, 56, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murzin, S.P.; Bielak, R.; Liedl, G. Algorithm for calculation of the power density distribution of the laser beam to create a desired thermal effect on technological objects. Comput. Opt. 2016, 40, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Extensions to the navier–stokes equations. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34, 53106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeshoji, T.; Hafskjold, B. Non-equilibrium molecular dynamics calculation of heat conduction in liquid and through liquid-gas interface. Mol. Phys. 1994, 81, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Durst, F.; Ray, S. Modeling moving-boundary problems of solidification and melting adopting an arbitrary lagrangian-eulerian approach. Numer. Heat Transf. Part B 2006, 49, 299–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, T.; Rossi, M.; Boeck, T. Viscous instability of a sheared liquid-gas interface: Dependence on fluid properties and basic velocity profile. Phys. Fluids 2013, 25, 32103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, N. Thermal transport regimes and effects of prandtl number in molten pool transport in laser surface melting processes. Numer. Heat Transf. Part A 2007, 53, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogi, K.; Ogino, K.; McLean, A.; Miller, W.A. The temperature coefficient of the surface tension of pure liquid metals. Metall. Trans. B 1986, 17, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, S.W. A molecular parameter relationship between surface tension and liquid compressibility. J. Phys. Chem. 1963, 67, 2160–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S. No. | Element | Purity | Particle Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Al | 99.9% | 45–106 μm |

| 2 | Co | 99.9% | 45–106 μm |

| 3 | Cr | 99.9% | 15–53 μm |

| 4 | Fe | 99.9% | 45–106 μm |

| 5 | Ni | 99.9% | 15–53 μm |

| C | Si | Mn | Ni | Cr | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤0.12 | ≤0.75 | ≤1 | ≤0.6 | 16~18 | Bal. |

| Parameter | 430 Substrate | Cladding Layer (AlCoCrFeNi) |

|---|---|---|

| Solidus temperature, Ts (K) | 1658.2 | 1683.2 |

| Liquidus temperature, Tl (K) | 1784.2 | 1824.7 |

| Latent heat, L (J/g) | 232 | 22.1 |

| Melting temperature, Tm (K) | 1721.2 | 1753.2 |

| Solid phase-specific heat capacity, Cp1 (J/kg/K) | 500 | 565 |

| Liquid phase-specific heat capacity, Cp2 (J/kg/K) | 850 | 1100 |

| Process Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Laser power, p (W) | 1450 |

| Powder feeding rate, mf (g/s) | 0.9 |

| Carrier gas flow rate, vc (L/min) | 7.5 |

| Beam radius, rd (mm) | 1.5 |

| Laser energy density, Led (J/mm2) | 205.7 |

| Scanning speed, v (mm/s) | 8 |

| Mass flow radius, rp (mm) | 1.6 |

| Emissivity, ε | 0.6 |

| Ambient temperature, (K) | 293.15 |

| W (μm) | H (μm) | h (μm) | η (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment | 2931.05 | 1199.69 | 340.82 | 22.55 |

| Simulation | 3075.83 | 991.53 | 400.73 | 28.78 |

| Error (%) | 4.94 | 17.35 | 17.36 | 27.60 |

| Crystalline Phase | Strongest Peak Crystal Plane | 2θ (°) | Peak Intensity | RIR | Mass Fraction (wt.%) | Volume Fraction (vol.%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCC | (111) | 43.40 | 3613.48 | 2.0 | 29.8 | 27.7 |

| BCC | (200) | 65.56 | 5486.14 | 1.8 | 49.8 | 50.7 |

| B2 | (100) | 28.98 | 2409.47 | 1.9 | 20.7 | 21.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, A.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, S. Numerical Simulation of Temperature Field, Velocity Field and Solidification Microstructure Evolution of Laser Cladding AlCoCrFeNi High Entropy Alloy Coatings. Lubricants 2025, 13, 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120541

Huang A, Liu Y, Li X, Liu J, Yang S. Numerical Simulation of Temperature Field, Velocity Field and Solidification Microstructure Evolution of Laser Cladding AlCoCrFeNi High Entropy Alloy Coatings. Lubricants. 2025; 13(12):541. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120541

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Andi, Yilong Liu, Xin Li, Jingang Liu, and Shiping Yang. 2025. "Numerical Simulation of Temperature Field, Velocity Field and Solidification Microstructure Evolution of Laser Cladding AlCoCrFeNi High Entropy Alloy Coatings" Lubricants 13, no. 12: 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120541

APA StyleHuang, A., Liu, Y., Li, X., Liu, J., & Yang, S. (2025). Numerical Simulation of Temperature Field, Velocity Field and Solidification Microstructure Evolution of Laser Cladding AlCoCrFeNi High Entropy Alloy Coatings. Lubricants, 13(12), 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120541