Abstract

Ti-6Al-4V alloy is a popular metal in engineering, utilized in aerospace and automotive industries because of its mechanical properties. However, Ti-6Al-4V’s poor tribological characteristics cause it to be susceptible to wear due to its low surface hardness and inadequate lubricity. In this study, thermal oxidation (TO) was performed on Ti-6Al-4V under specific conditions of 625 °C for various oxidation durations of 0.5, 1.5, 6, 24 and 96 h and the microstructure, friction, and wear behavior of TO-treated Ti-6Al-4V under dry and oil-lubricated sliding conditions were investigated. Characterization by XRD, SEM, and EDX confirms the development of oxide layers (OL) and oxygen diffusion zones (ODZ) of varying thicknesses. Tribological tests were conducted using a ball-on-disk configuration under a 5 N load against an Al2O3 counterface in both dry and 10W-40 oil-lubricated environments. Under dry conditions, extended oxidation times lead to a deterioration in friction and wear performance due to the increased brittleness and decreased adhesion of the thick OL, leading to brittle failure and interfacial delamination. In contrast, under oil lubrication conditions, all oxidized samples show stable, low-friction (~0.06) and minimal wear, dominated by boundary lubrication. The best performance is achieved at short oxidation durations, where a thin OL and a stable ODZ provide strong adhesion of the OL and high surface hardness. Wear rates up to three orders of magnitude lower than untreated Ti-6Al-4V are observed for short oxidation durations, where oxygen diffusion rather than thick oxide formation dominates the surface-hardening effect. SEM and EDX analyses confirmed the lack of tribofilms or additive-derived elements on the sliding surfaces, indicating that the improved performance results from the oxygen-enrichment in the subsurface and stable boundary lubrication, rather than chemical interactions with oil additives. Overall, oxidation duration is therefore essential to balance oxide growth and OL adhesion, ensuring superior lubricated wear resistance for titanium components.

1. Introduction

Titanium alloys, especially Ti-6Al-4V (Grade 5), are extensively used in aerospace, automotive, and biomedical applications due to their role in load-bearing components subjected to various loads and environments [1,2,3]. Their popularity stems from a combination of low density, high strength, thermal stability, and excellent corrosion resistance, which contributes to fuel efficiency and engine performance across sectors [4,5,6]. These properties not only enhance mechanical performance but also support compliance with environmental regulations targeting reduced CO2 emissions [7,8]. However, Ti-6Al-4V suffers from poor tribological performance due to its low surface hardness, particularly under sliding contacts [9,10]. Friction and wear can be reduced through proper lubrication, compatible counterbody materials, or surface treatments [9]. Titanium’s electron configuration and crystal structure hinder the adhesion of conventional lubricants, causing oil films to degrade rapidly under localized heat and pressure, even at low loads [10,11]. The low thermal conductivity and high chemical reactivity make titanium ineffective with conventional oils, especially in lightweight, high-performance applications like gears and engine components [12].

Surface-engineering treatments, including diffusion processes such as nitriding and oxygen diffusion, hard coatings such as TiN, CrN and DLC [4,13,14], laser-textured surfaces combined with DLC films, in situ composite formation, and mechanical surface modifications such as shot peening, have been extensively investigated for improving the tribological behavior of Ti-6Al-4V [15,16]. Hard coatings in particular (TiN, CrN and DLC) provide excellent friction and wear resistance, which enhances the durability and reliability of Ti-6Al-4V in demanding tribological applications [4]. Although these coatings offer significant benefits, thermal oxidation (TO) remains an attractive alternative because it is cost-effective, simple to apply, and capable of producing a strongly adhered oxide layer without restrictions on component geometry. TO also increases surface hardness and improves the ability of the surface to retain lubricant, making it well suited for industrial applications [9,17,18,19].

Researchers applied thermal oxidation methods to promote the phenomenon of oxygen diffusion, hardening the surface and promoting the formation of a thin hard oxide layer on the surface which protects the substrate and can enhance lubrication for titanium alloys [20,21]. Studies using TO were focused on the development of three tribological properties, such as surface hardness, oxide layer stability under load, and tribological behavior under lubrication conditions [15,22,23,24]. Various reports studied the wear behavior of TO Ti-6Al-4V treated at different TO temperatures and for different TO times. They have observed that the change in TO parameters influences the OL and ODZ growth, the resultant surface hardness and the wear resistance [25,26,27]. However, this enhanced resistance does not persist throughout the sliding test durations, as the OL begins to delaminate over time. This degradation is confirmed to be more pronounced with increased oxidation time and temperature. This behavior is attributed primarily to interfacial stresses occurring from thermal expansion mismatch between the oxide layer and the substrate, combined with internal growth stresses within the oxide [28].

The tribological performance of TO-treated Ti-6Al-4V was evaluated under ball-on-disk sliding conditions. It was observed that the TO treatment results in the formation of a rutile (TiO2) OL, which possesses high wettability. The treatment leads to an improvement in wear resistance under lubricated conditions [9,29]. An investigation was performed on the tribological behavior of TO-treated titanium (Ti-Ti) tribopairs under dry and lubricated conditions. While untreated Ti shows poor lubricity with engine oil, oxidized surfaces, especially when both contacting surfaces are TO treated, exhibit good lubricity with the engine oil with a much-reduced coefficient of friction (CoF) down to 0.11, attributed to boundary lubrication [22]. Significant challenges remain despite the work conducted in enhancing the wear resistance and improving the adhesion of oil films on Ti-6Al-4V, both under untreated conditions and under TO treatments. These improvements are crucial for extending the lifespan of Ti-6Al-4V components in tribosystem applications and for promoting lightweight designs in automotive and aerospace to boost fuel efficiency. There is a lack of literature on the properties of Ti-6Al-4V, and limited reporting on the effect of different oxidation times of Ti-6Al-4V under engine oil lubrication.

The novelty of this study lies in the systematic evaluation of how oxidation duration influences both surface microstructure (OL and ODZ development) and tribological behavior under dry and oil-lubricated sliding. Previous studies have typically focused either on a single oxidation duration or on dry sliding alone, leaving the combined effects of oxidation time, subsurface oxygen enrichment, and lubrication regime insufficiently explored. By examining five oxidation durations at a constant temperature, this work aims to clarify how OL growth and ODZ formation interact with dry and lubricated contact conditions to govern friction and wear behavior in Ti-6Al-4V.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Thermal Oxidation

The substrate material used was titanium alloy (Ti-6Al-4V) grade 5, sliced into square samples measuring 20 mm × 20 mm with a thickness of 5 mm. The chemical composition of the alloy, expressed in weight percent (wt.%), is as follows: 6.6% Al, 4.1% V, 0.18% O, 0.008% H, 0.02% C, 0.01% N, 0.23% Fe, with the balance being titanium (Ti). The specimens were subjected to sequential wet grinding with silicon carbide (SiC) abrasive papers ranging from P120 to P1200 grit to achieve a surface finish (Ra) of 0.056 µm. The counterbody used in this work had a spherical shape with an 8 mm diameter and was made of alumina (Al2O3) with a surface finish (Ra) of 0.08 µm. Following mechanical preparation, the samples were cleaned in methanol and air-dried before thermal oxidation.

Ti-6Al-4V samples underwent TO treatments at 625 °C for periods of 0.5, 1.5, 6, 24, and 96 h. The TO treatment was conducted in a laboratory muffle furnace (Carbolit CWF1100 (Carbolite Gero Ltd., Hope, UK)) under atmospheric oxygen partial pressure, without controlled gas composition. Subsequently, the samples were allowed to cool in the furnace naturally, which took approximately 12 h to reach ambient temperature below 35 °C, after which the samples were retrieved. This process is referred to as furnace cooling (FC). According to previous work [30], cooling rate is a critical factor in promoting proper adhesion and stable oxide layer formation during oxidation. Slow and moderate cooling rates result in good adhesion of the oxide layer with the substrate, while fast cooling causes thermal stress and spallation, especially at elevated temperatures due to the large expansion between the substrate and the oxide [31,32,33].

2.2. Dry and Oil-Lubricated Sliding Friction and Wear Tests

The sliding friction and wear behaviors of untreated and TO-treated Ti-6Al-4V samples were studied under dry and oil-lubricated conditions using a pin-on-disc tribometer manufactured by Teer Coating Ltd. During the test, an alumina (Al2O3) ball was held stationary in the jig, while the sample was rotating with a rotational speed of 60 rpm for 3600 s. The test was conducted at room temperature with 5 N applied load, and the CoF was recorded throughout the test via computer data logger and acquisition system. The sliding speed was calculated as 3.7 cms−1 for a wear track diameter of 12 mm, and a total sliding distance of 135.6 m for both dry and oil-lubricated conditions. Each tribological test was repeated to assess repeatability. If repeated runs did not converge, additional repetitions were performed until a consistent friction response was obtained.

The maximum contact pressure for the initial elastic contact between Ti-6Al-4V and the Al2O3 ball under an applied load of 5 N, calculated using Hertzian theory (with Young’s modulus of ETi-−6Al-4V = 111 GPa, and

= 370 GPa), was Pmax = 792 MPa.

During the lubricated sliding test, both the ball and disc samples were immersed in lubricant oil. The lubricant used was a multigrade motor oil, specifically 10W-40, with typical properties listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 10W-40 Motor oil used in this study.

The thickness of the oil film for Al2O3 ball-on-Ti6Al4V flat contact under 5 N load was calculated using the Hamrock and Dowson formula [34], detailed in ref [35]. The calculated oil film thickness was approximately 0.012 µm (12 nm), which is significantly smaller than the combined roughness of the contacting surfaces, i.e.,

(98 nm). This confirms that the contact operated in the boundary lubrication regime.

2.3. Characterisation

The surface roughness values of the untreated and TO-treated samples were measured using a stylus surface profilometer (Taylor-Hobson, Leicester, UK). The thicknesses of the OL and ODZ resulting from various TO treatment durations were measured microscopically from metallographic cross-sections using an optical microscope (Nikon LV150N, Tokyo, Japan). The surface hardness of the untreated and TO-treated samples were measured under various indentation loads ranging from 0.2 Kg to 2 Kg using a microhardness tester (Zwick/Roell ZHV1M, Ulm, Germany). X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used to perform phase composition analysis of the TO-treated samples, using a diffractometer (Bruker 2nd generation D2 phaser diffractometer) and Cu-Kα radiation, with a scanning angle range of 30° to 120°. The wear volumes from the wear tracks on the samples were evaluated by measuring the cross-sectional profiles of the wear tracks using the profilometer, with measurements taken at four locations on each wear track. The wear scars on the alumina balls and wear tracks on the samples were examined under Nikon optical microscope. SEM and EDS (Carl Zeiss EVO HD 15, Jena, Germany) were also used to examine the ball scars and the wear tracks to investigate the topographical contrast and perform localized chemical mapping analyses for increased clarity.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characteristics of TO-Treated Samples

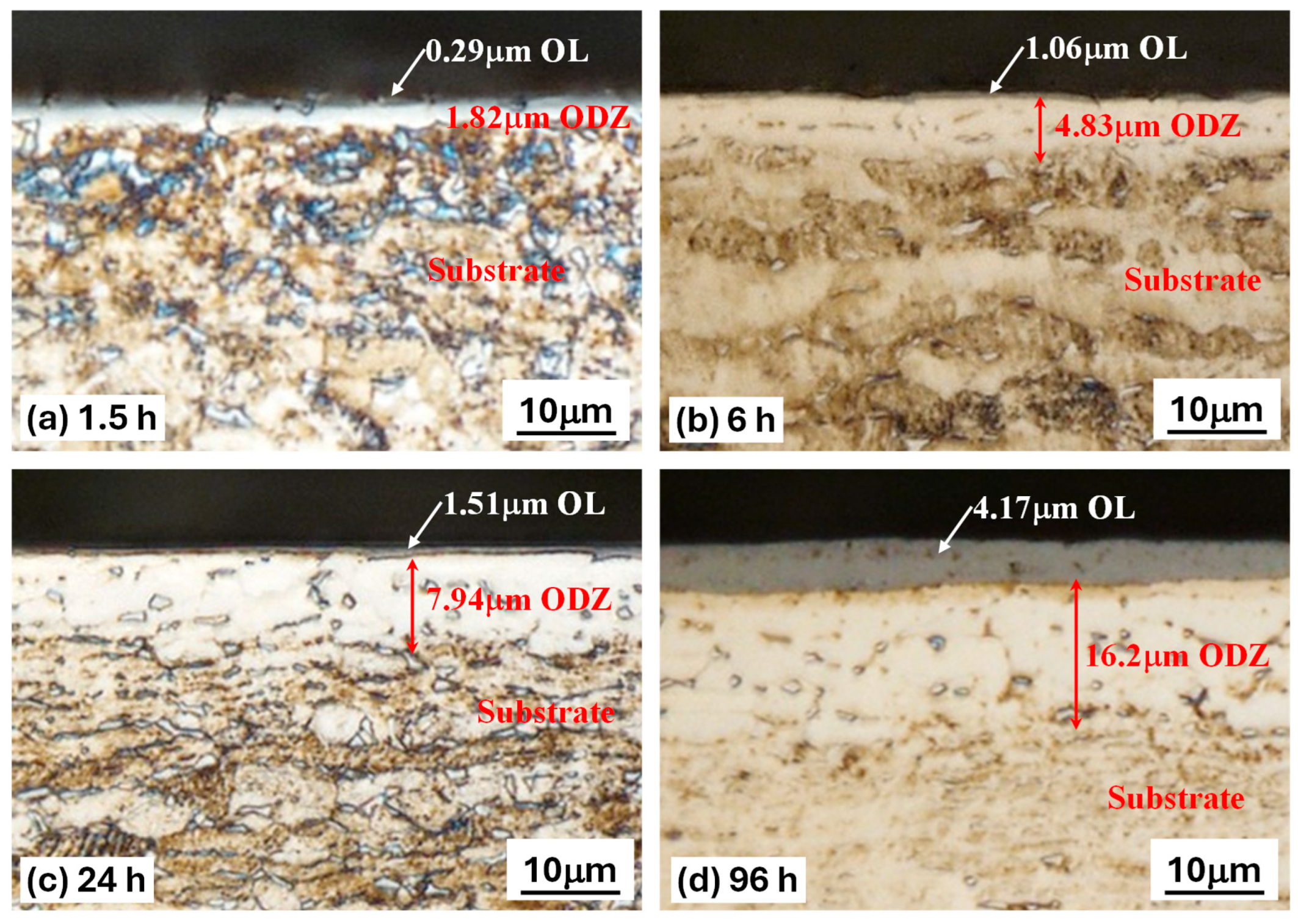

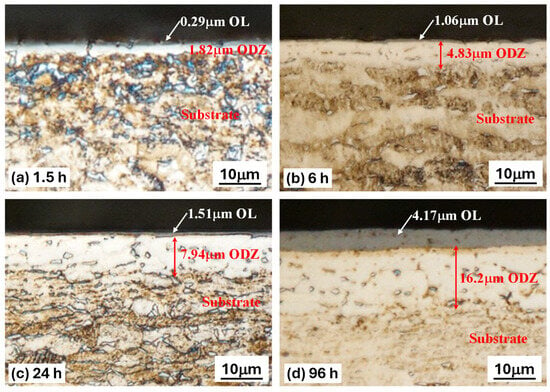

The cross-sectional microstructures of TO-treated Ti-6Al-4V samples distinctly reveal the formation of layered structures, attributed to the high oxygen affinity of Ti-6Al-4V during oxidation, as illustrated in Figure 1. Table 2 shows the measured thicknesses of the thermally grown oxide layers, oxygen diffusion zones, and surface roughness. The TO treatment led to increased surface roughness. Three distinct zones can be observed in the cross-section: the outermost OL, followed by the ODZ, and finally, the underlying Ti-6Al-4V substrate (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cross-section images of the metallographic sections of TO-treated Ti-6Al-4V, revealing the oxide layer and the oxygen diffusion zone for different oxidation durations; (a) 1.5 h TO, (b) 6 h TO, (c) 24 h TO, (d) 96 h TO.

Table 2.

Measured oxide layer thickness, oxygen diffusion zone thickness, and surface roughness parameter (Ra) for the untreated and TO samples.

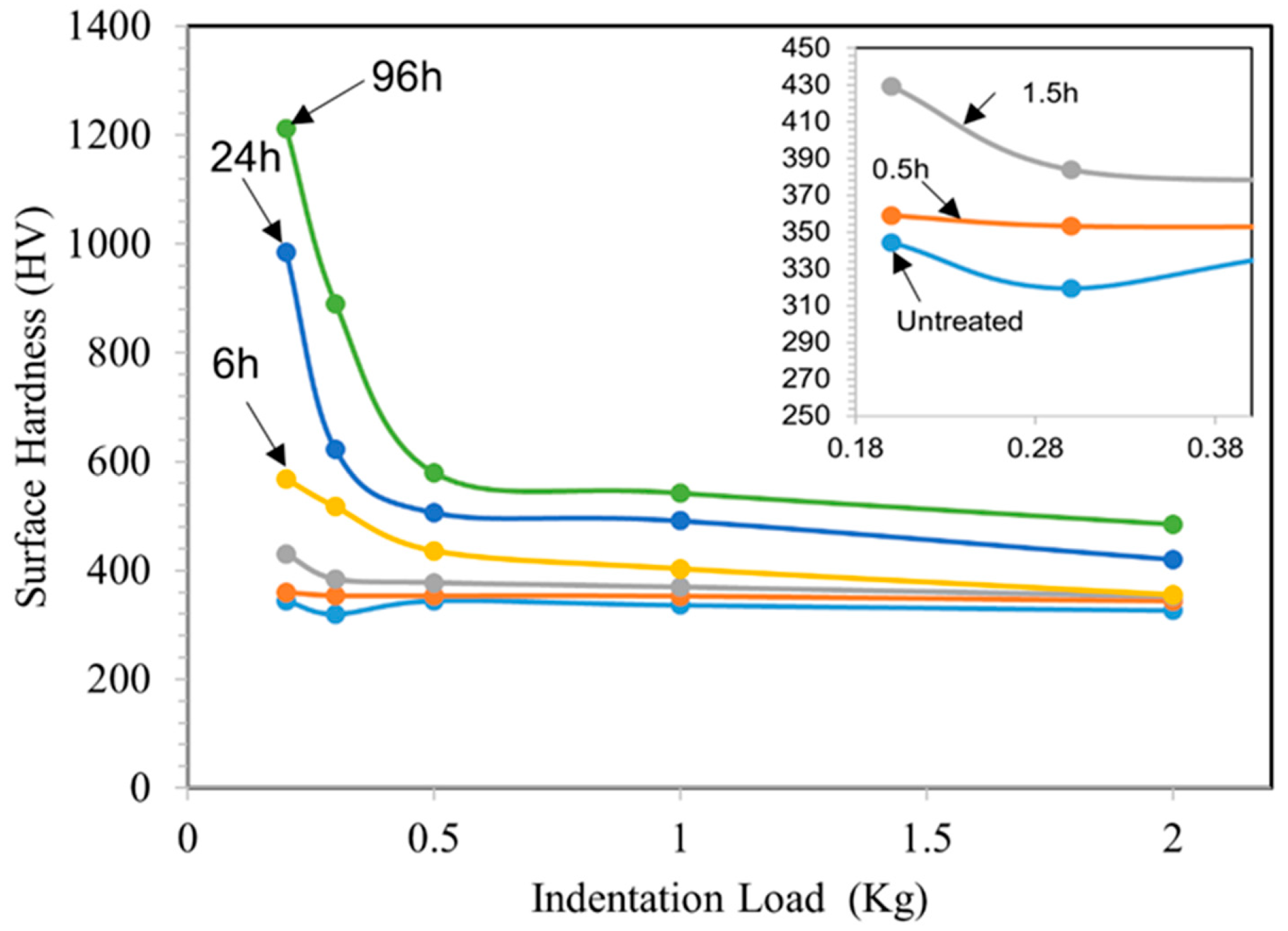

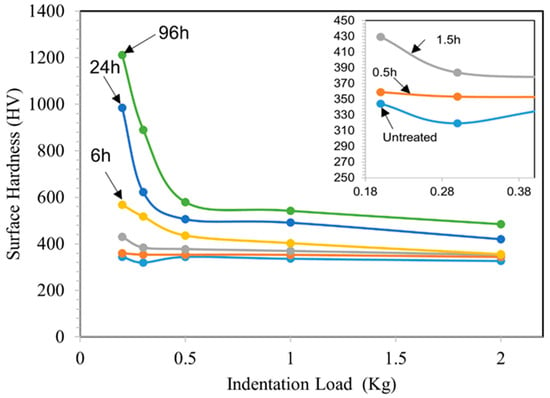

TO treatments at a temperature of 625 °C enable obtaining good-quality oxide layers, covering the entire oxidized surface without traces of spalling. The OL thickened with increasing oxidation treatment time. However, for the 0.5 h TO sample, it is difficult to distinguish the OL thickness using an optical microscope. Therefore, the chromaticity principle introduced by the International Commission on Illumination (CIE) was assessed based on the color of the sample on visual observations [36]. As a result, the thickness of a light blue color OL for the 0.5 h sample is approximately 0.08 μm. From Figure 1 and Table 2, the thicknesses of both the OL and ODZ increase with increasing oxidation duration. For short-time TO (0.5 h and 1.5 h), the resultant OL is of sub-micron thickness, and the ODZ is also very thin. However, as demonstrated below, this is sufficient in achieving effective lubrication under oil-lubricated conditions. As a result of TO treatments, the surface hardness is increased as shown in Figure 2. Cross-sectional microhardness mapping was not attempted due to the limited OL thickness at short oxidation times and indentation-size effects. Progressive-load surface hardness measurements were used as an indirect indicator of subsurface oxygen hardening. The increase in observed hardness depends on TO duration: longer durations lead to larger increases in hardness, likely due to the increased OL and ODZ thicknesses. Short-time TO treatments only lead to a marginal increase in surface hardness. However, as demonstrated below, this is sufficient to change the surface characteristics of Ti-6A-l4V such that effective oil lubrication could be achieved.

Figure 2.

Surface hardness of the untreated and TO samples as a function of indentation load. TO temperature: 625 °C; Oxidation durations: 0.5, 1.5, 6, 24 and 96 h.

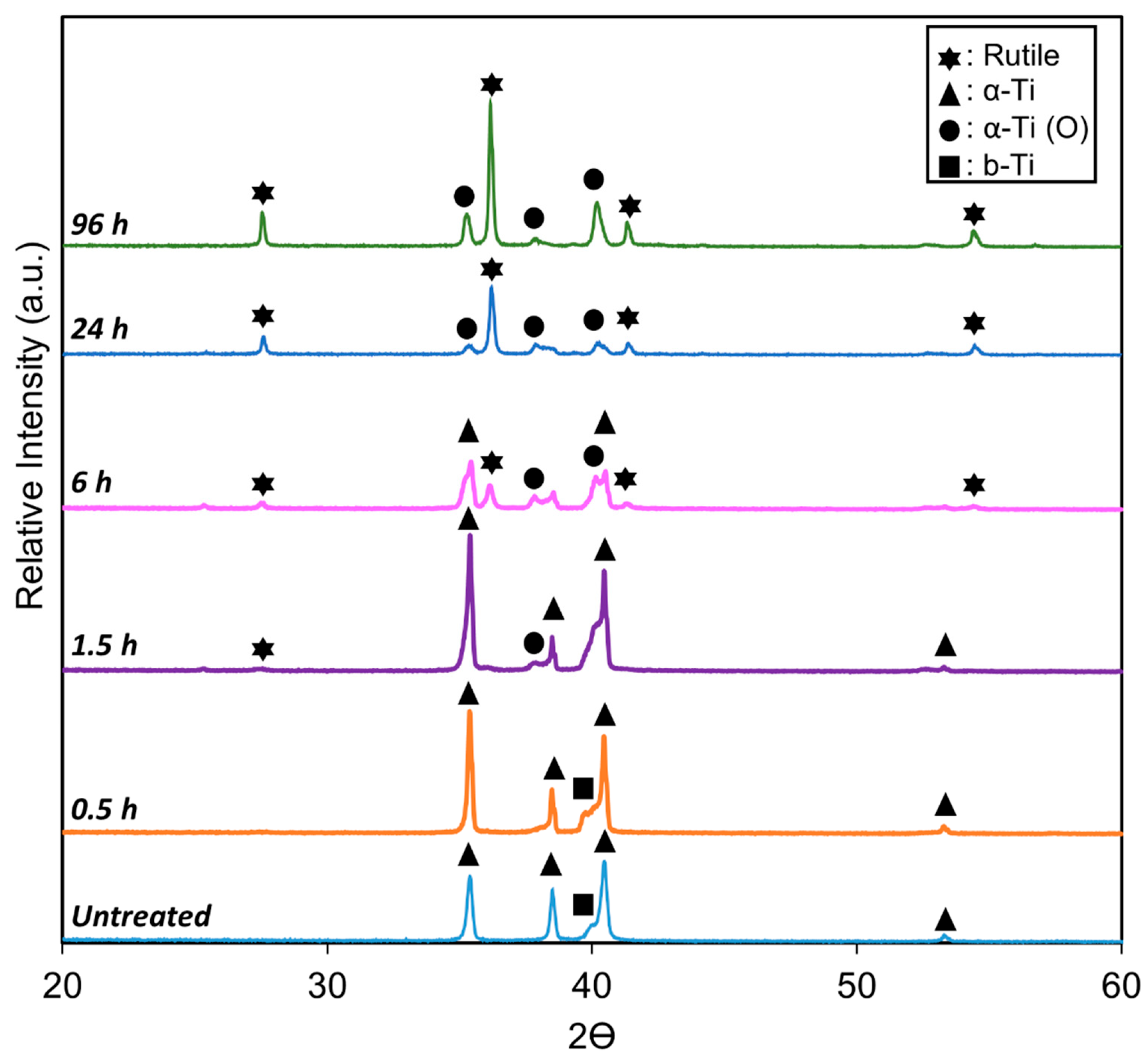

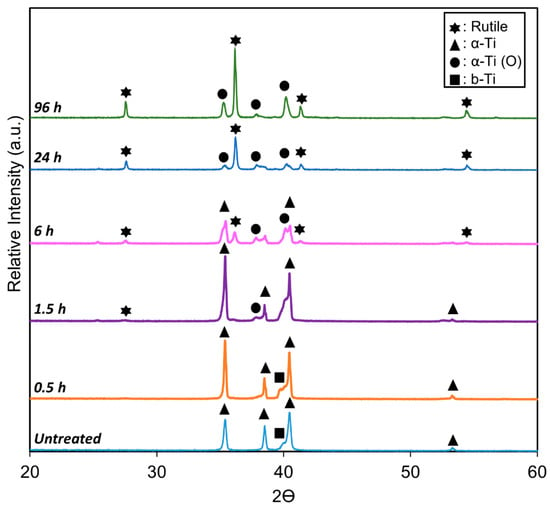

The XRD pattern of the untreated Ti6Al4V (Figure 3) clearly shows characteristic peaks for both the alpha (α-Ti) and beta (β-Ti) phases, consistent with microstructure analysis. However, a notable change occurs following TO treatment at 625 °C for various durations.

Figure 3.

XRD profiles of untreated titanium and TO-treated Ti-6Al-4V at 625 °C for 0.5, 1.5, 6, 24, and 96 h, highlighting key peaks for α-Ti, β-Ti, α-shift due to interstitial oxygen dissolution, and rutile TiO2.

As oxidation time increased from 0.5 h to 96 h, rutile (TiO2) peaks emerge and intensify in the TO samples, indicating the formation and growth of a titanium dioxide layer. This observation aligns with previous studies on the phase characterization of oxidized titanium alloys [37].

Despite the continuous growth of the oxide layer, the underlying α-Ti phase peaks remained detectable, albeit slightly shifted, even after the longest oxidation duration (96 h). This shift, widely documented [38], occurs due to the expansion of lattice parameters a and c in HCP α-Ti, and a in BCC β-Ti, causing diffraction peaks to shift toward lower 2θ angles, consistent with oxygen dissolution. The magnitude of this shift corresponds to the amount of oxygen dissolved in the titanium matrix. As oxidation duration increases, the β-phase progressively disappears, due to the formation of an α-phase layer beneath the oxide. This layer forms as oxygen diffuses into the titanium lattice, stabilizing the α-phase and effectively suppressing the β-phase signal beneath the growing oxide layer.

3.2. Friction Characteristics

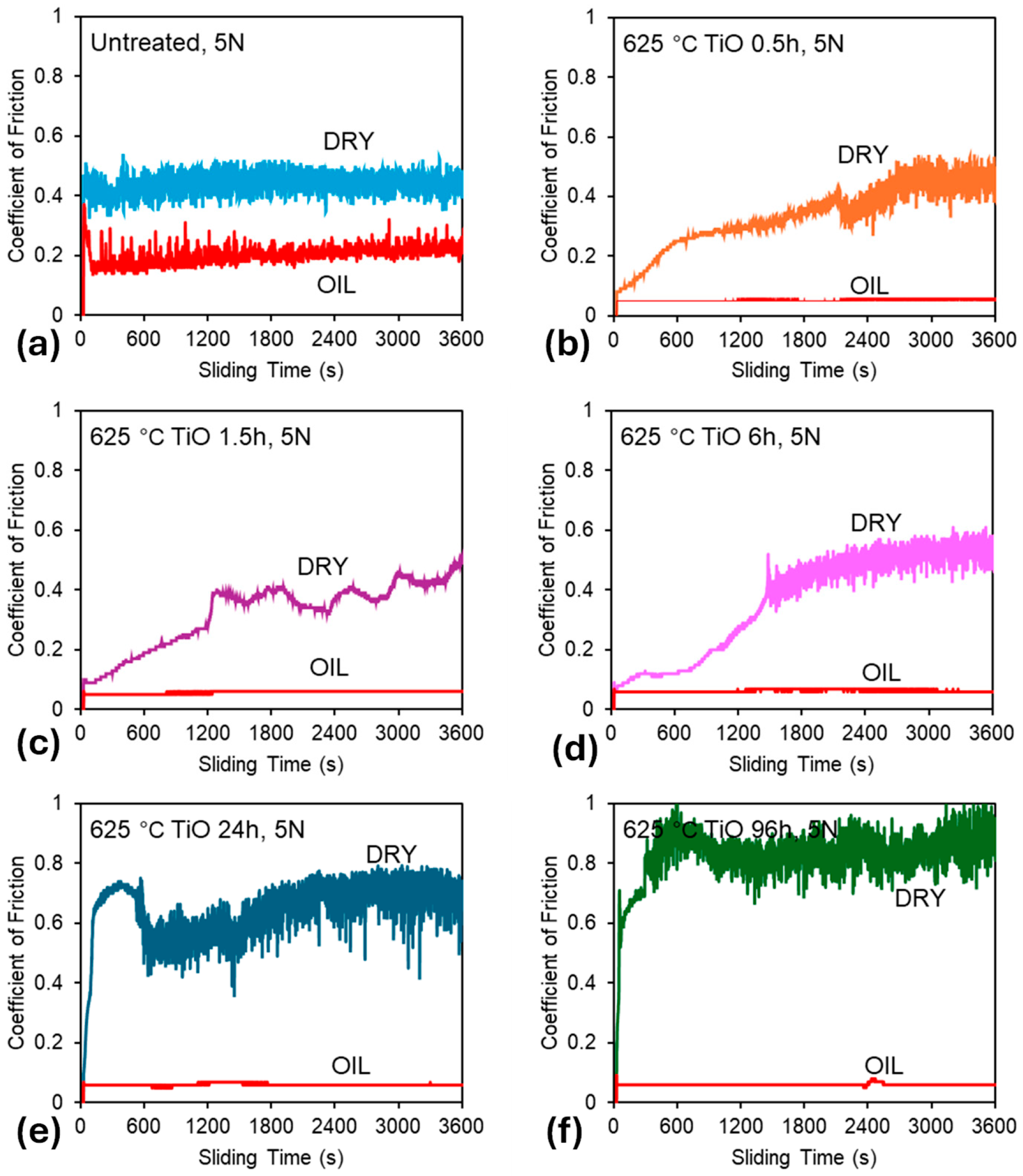

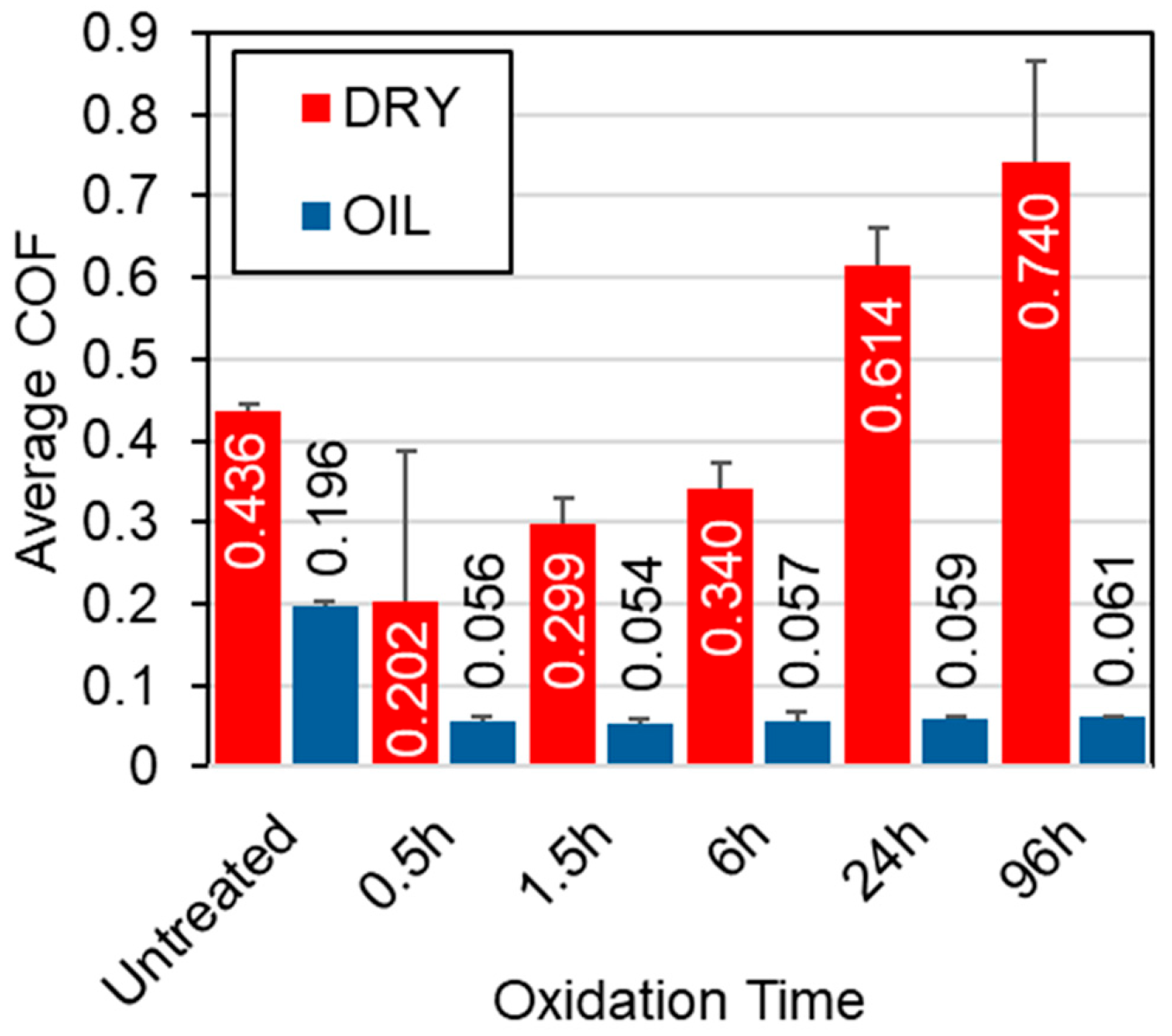

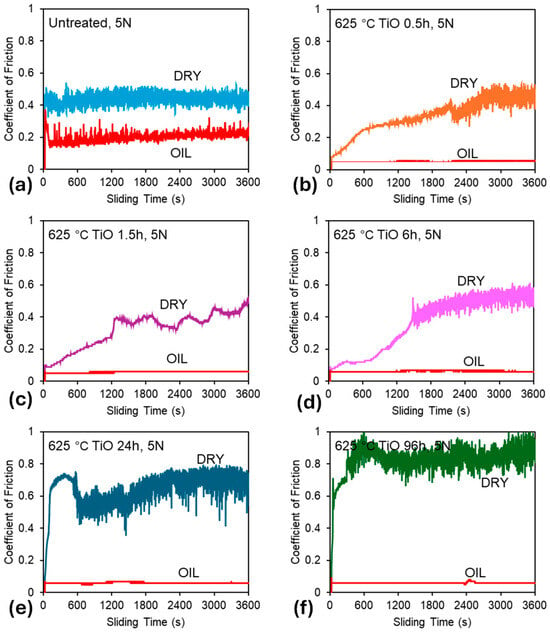

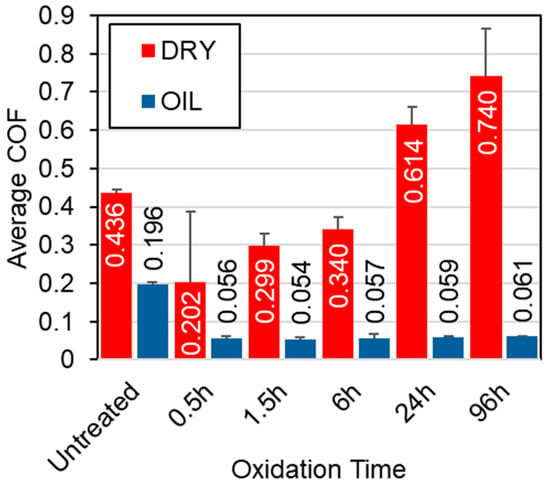

Figure 4 presents the CoF curves recorded under 5 N contact load for all tested samples, in both unlubricated (dry) and oil-lubricated conditions. Preliminary tests demonstrated that lower loads resulted in negligible wear under dry conditions. Similarly, all samples exhibited low (un-measurable) wear in oil-lubricated environments at lower loads. Therefore, a 5 N load was selected to better highlight differences in different samples. Three key observations emerge from the data presented in Figure 4 and Figure 5:

Figure 4.

Friction curves recorded during the sliding tests: (a) untreated sample, (b) 0.5 h oxidation, (c) 1.5 h oxidation, (d) 6 h oxidation, (e) 24 h oxidation, and (f) 96 h oxidation.

Figure 5.

Average CoF for the untreated and TO samples under both lubricated and unlubricated conditions during sliding contact at a 5 N load.

- •

- Untreated Ti-6Al-4V: Untreated Ti-6Al-4V displays unstable frictional behavior under both dry and 10W-40 oil-lubricated conditions (see Figure 4a). Although lubrication reduces the average CoF from 0.44 (dry) to 0.20 (lubricated), significant fluctuations persist, resulting in erratic and unstable frictional response. This instability, previously reported for alumina-titanium sliding pairs [39,40] highlights the lubricant’s inability to fully prevent adhesive contact.

- •

- TO samples under dry conditions: Under dry conditions, TO treatments provide only modest improvements to the CoF response, and in some cases, the average CoF increases compared to the untreated sample (See Figure 5). Specifically, shorter oxidation durations (0.5 h and 1.5 h) result in lower and more stable friction values compared to the untreated sample, suggesting a temporary improvement in tribological performance in the dry environment. This is attributed to the poor adhesion of the OL, caused by delamination at the oxide–substrate interface, as previously documented [41]. The breakdown of the OL from the wear track can result in third bodies entering the wear track, changing the contact mechanics, and consequently leading to higher levels of CoF as demonstrated in the 24 h and 96 h samples (see Figure 4e and Figure 4f, respectively).

- •

- TO samples under oil-lubricated conditions: Under oil-lubricated conditions, all oxidized samples exhibit low and stable CoF values (Figure 4b–f), approximately 0.06, regardless of oxidation duration (Figure 5). This behavior is typical of boundary lubrication, where a thin adsorbed lubricant film at the contact interface reduces direct asperity contact and stabilizes friction behavior [42]. Importantly, this suggests that OL thickness may not be the primary contributor to lubricity. Even a short, 0.5 h oxidation notably reduces friction, despite minimal increases in surface hardness (Figure 1) and no discernible rutile TiO2 peak in XRD patterns (Figure 3), indicating an oxide film too thin to be detected using available equipment. However, the α-Ti peak shifts (Figure 3) indicate oxygen diffusion into the subsurface. This phenomenon is expected given titanium’s high oxygen solubility. The corresponding oxygen diffusion zone, measurable through cross-sectional etching, reaches approximately 1 µm in depth for the 0.5 h sample (see Table 2), and this seemed sufficient to achieve effective lubrication.

3.3. Wear Track Morphology

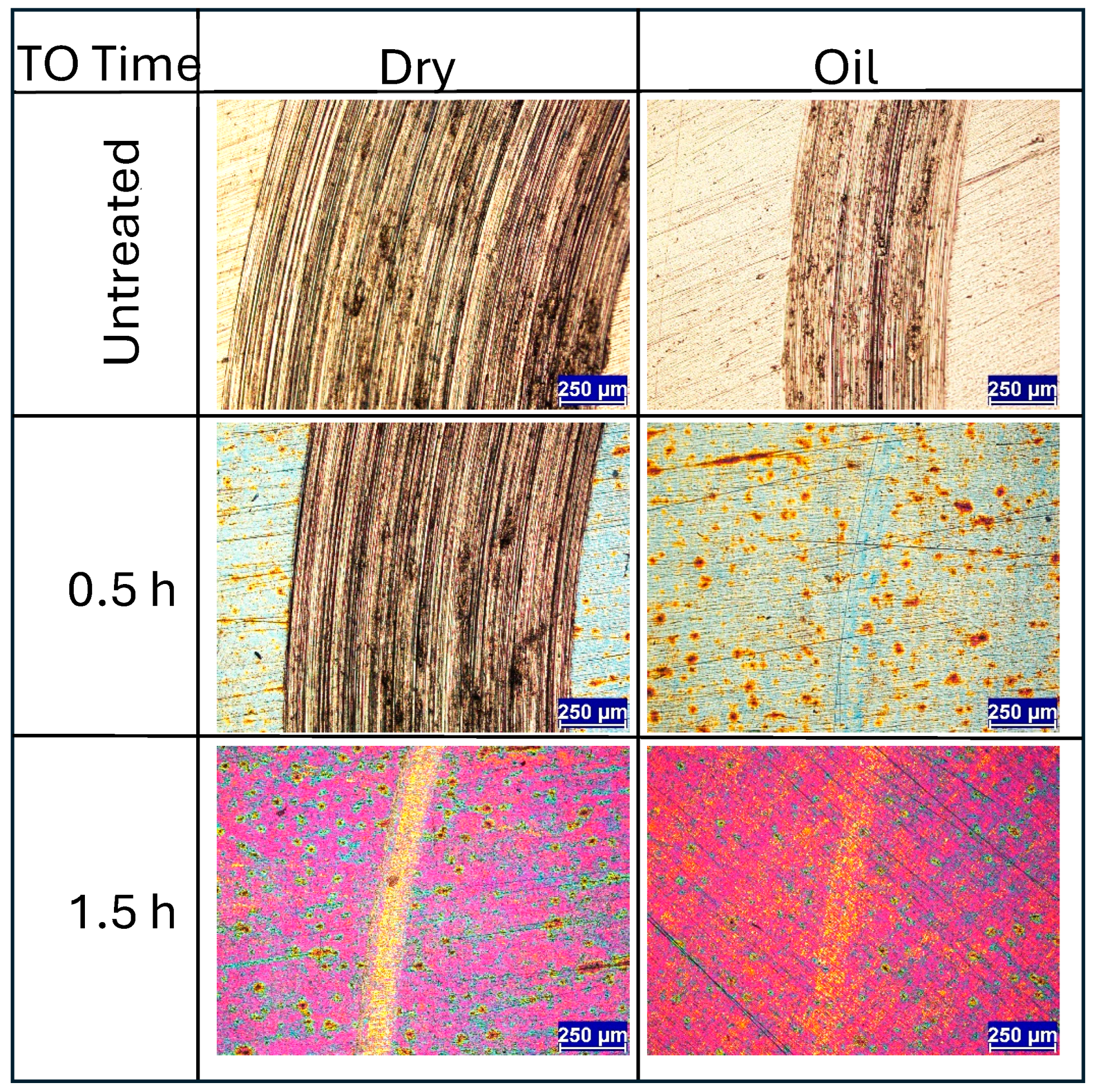

The wear track morphologies were examined using optical microscopy to characterize surface features and identify dominant wear mechanisms. While the core focus of this study is on oil-lubricated performance, a brief comparison with unlubricated (dry) conditions is included to assess the impact of thermal oxidation in both settings.

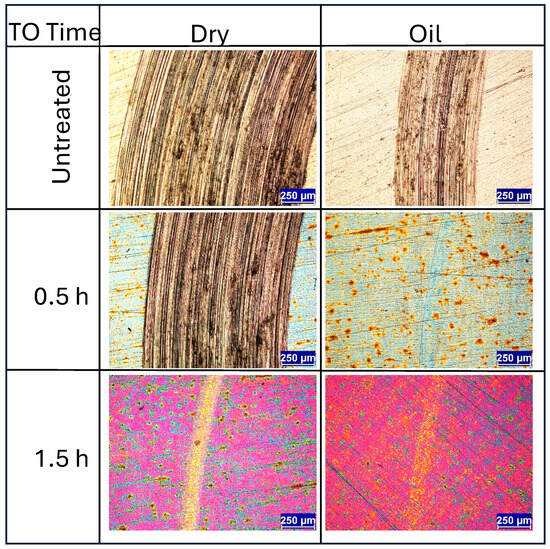

Initial observations centre on the short-time TO samples. Figure 6 presents wear track images for untreated Ti-6Al-4V and samples TO treated for 0.5 h and 1.5 h, tested under both dry and lubricated conditions. Under dry condition, the untreated sample exhibits typical wear behavior for Ti-6Al-4V sliding against an alumina counterface, dominated by adhesive and abrasive wear mechanisms with substantial amounts of galling [4,30,43,44]. Under lubricated conditions, the same wear mechanisms persist, though the wear track is reduced in width and depth, which is consistent with the lower CoF observed in Figure 4a. However, the friction response remains unstable under lubricated conditions, a result attributed to persistent adhesive interactions, evidenced by distinct galling signs shown in Figure 6. The poor lubrication response of titanium and its alloys is often attributed to its high chemical reactivity and low heat conduction, resulting in a tendency towards galling [45,46].

Figure 6.

Wear track images of the untreated and the short-time TO samples (≤1.5 h) when subjected to dry and lubricated sliding against an Al2O3 ball at a load of 5N under dry and oil (10W-40) conditions.

Under dry conditions, a comparison of the 0.5 h and 1.5 h TO samples reveals clear differences in wear track morphology. The 0.5 h sample shows wear behavior nearly identical to the untreated specimen, though with a slightly smaller wear track width (1.38 mm versus 1.07 mm, respectively). This indicates limited mechanical protection from the thin oxide layer. Figure 4b supports this observation, showing a gradual rise in CoF throughout the test, eventually matching that of untreated Ti-6Al-4V. In contrast, the 1.5 h TO sample shows marked improvements under dry conditions. Traditional abrasive wear is largely absent, replaced instead by mild surface polishing with occasional deeper scratches. This suggests that even a short TO duration can substantially reduce wear rates. The corresponding CoF curve displays less fluctuation and a more stable response, though it gradually rises from ~0.1 to ~0.3 (Figure 4c). Beyond this point, the CoF becomes more erratic, potentially due to counterface material interactions. SEM and counterface analysis indicate that some material pull-out occurs from the alumina ball, likely resulting from mixed-mode contact. Localized removal of the thin OL from the titanium surface, combined with alumina debris transfer, appears to contribute to the irregular CoF behavior.

When tested under oil lubrication, both 0.5 h and 1.5 h TO samples show substantial reductions in wear track size and severity. The 0.5 h sample exhibits minimal abrasive wear with only light surface polishing within the contact zone (see Figure 6). This sharp contrast with the dry condition underscores the effectiveness of boundary lubrication, in alignment with the low and stable CoF observed in Figure 4b. The pattern is consistent in Figure 4c for the 1.5 h TO sample, further confirming that the tribological benefits of thermal oxidation are significantly enhanced in lubricated environments.

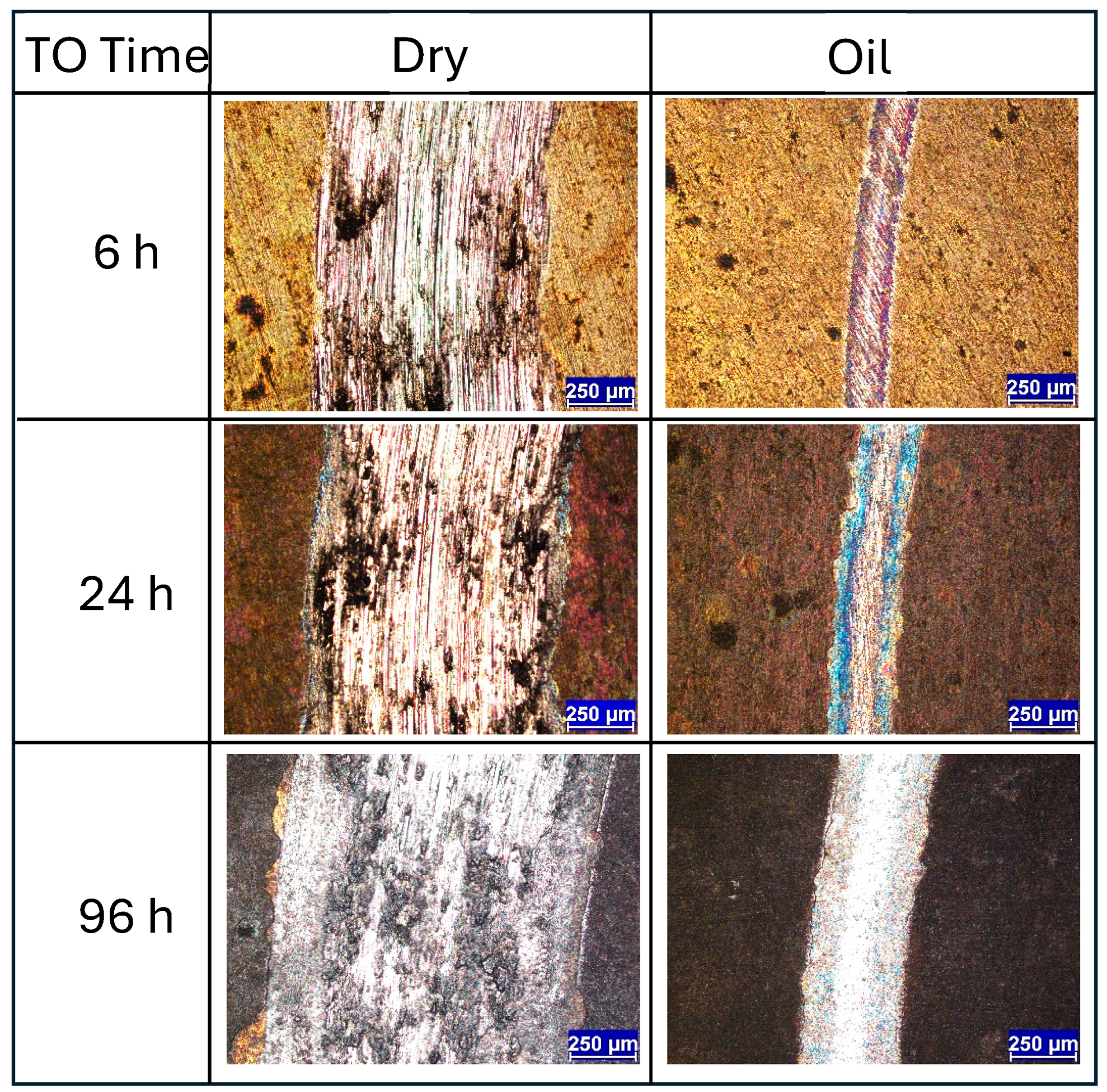

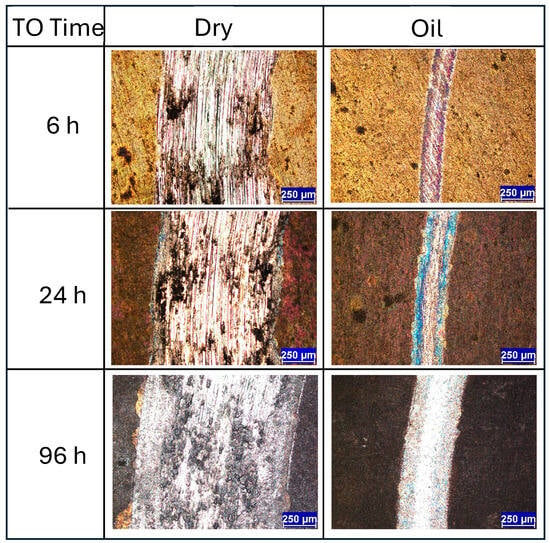

When evaluating the wear track morphologies for the 6 h, 24 h, and 96 h TO samples, several notable trends emerge. Under dry sliding conditions, TO treatments appear largely ineffective in preventing wear at 5 N contact load. The wear track images (Figure 7) show that the surface oxide layer has been extensively removed, resulting in wear morphologies closely resembling those of untreated Ti-6Al-4V and are dominated by abrasion, adhesion, and oxide layer flaking. Similar limitations in the oxide layer performance under elevated contact loads have been reported by other studies for thermally oxidized Ti [24,32]. Analysis of both wear morphology (Figure 7) and CoF data (see Figure 4d–f) suggests that each sample experiences an OL breakdown point during testing. Interestingly, the thicker the OL, the earlier this breakdown occurs: approximately 1500 s for the 6 h sample, 600 s for the 24 h sample, and just 300 s for the 96 h sample (derived from Figure 4). This trend reflects the trade-off between increased OL thickness and reduced OL adhesion to the substrate. Figure 7 clearly indicates that in the 24 h and 96 h samples, shear-induced delamination of the OL occurs both inside and outside the contact zone. As oxidation time increases, the tendency for brittle failure along the oxide–substrate interface becomes more pronounced, contributing to larger and more fragmented wear regions.

Figure 7.

Wear track images of the longer-time TO samples (≥6 h) when subjected to dry and lubricated sliding against an Al2O3 ball at a load of 5 N under dry and oil (10W-40) conditions.

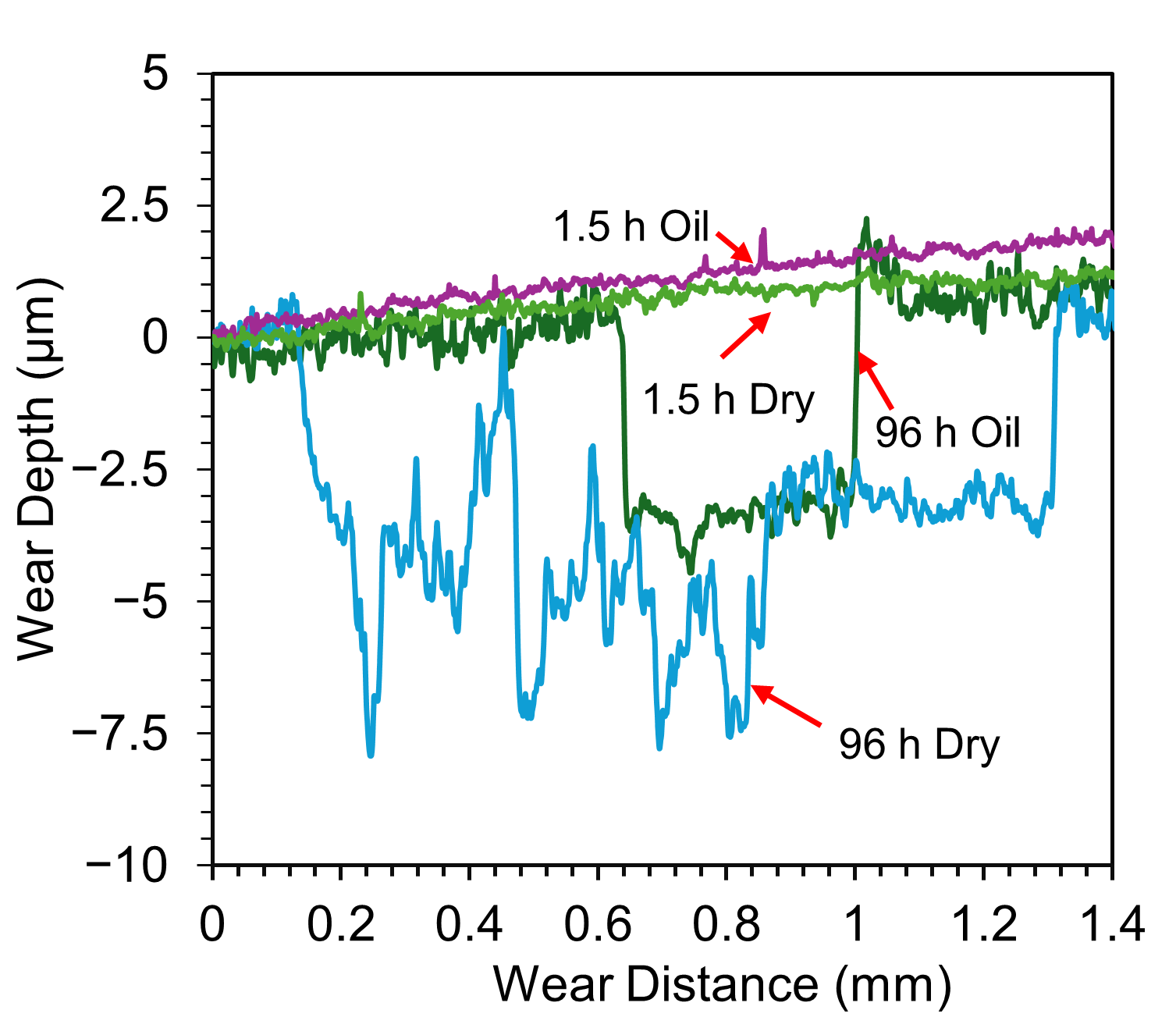

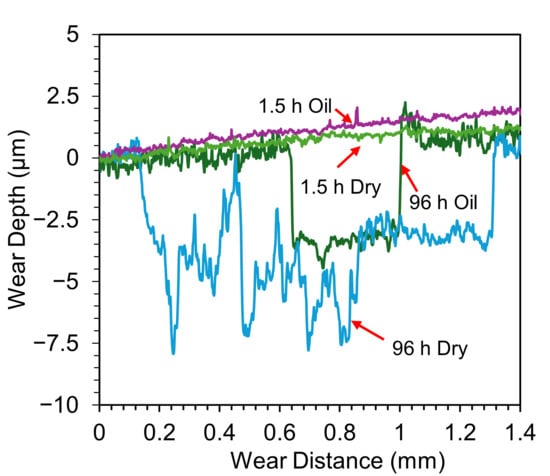

Under oil-lubricated conditions, the wear tracks for all three samples (6 h, 24 h, 96 h) are noticeably smaller. Nevertheless, inspection reveals that the OL has still undergone mechanical removal in each case, with shear failure caused by tractive forces during sliding. In the 24 h and 96 h TO samples, delamination extends beyond the central wear path, indicating widespread mechanical instability of the OL. Interestingly, the exposed ODZ exhibit limited wear, primarily in the form of mild abrasive polishing when in the contact zone. Adjacent areas show obvious signs of OL removal along the interface, suggesting poor adhesion between the OL and the substrate. Further insight is provided by the wear track profiles in Figure 8, which compare the 1.5 h and 96 h samples. These traces confirm that OL failure is not restricted to the sliding contact zone but extends beyond its boundaries, reinforcing the observation of interfacial delamination driven by mechanical shear during sliding for the extended oxidation durations. The friction curves (Figure 4e,f) show that, despite some fluctuations, the overall CoF remains low under oil lubrication. The disruption observed in the CoF curve of the 96 h TO sample (Figure 4f) is attributed to the OL failure, which transitions the contact mechanics from an alumina–OL interface to an alumina–ODZ interface. During this transition, wear debris may briefly contribute to third-body interactions. However, the oil flow helps displace these particles from the contact region, effectively re-establishing boundary lubrication over the ODZ, which, as shown in earlier sections, provides excellent wear performance. The 6 h TO sample shows slightly different behavior. OL removal appears more gradual, due to enhanced adhesion between the OL and substrate, typical of intermediate oxidation durations [32]. While the OL is ultimately stripped from the contact region, it does not produce abrupt changes in CoF (Figure 4d). Instead, fluctuations and noise in the COF curve reflect a slower, progressive removal process, consistent with better oxide–substrate bonding. Importantly, once the surface OL is lost, wear on the exposed ODZ is minimal and this further supports the finding that the oxygen-enriched sub-surfaces perform exceptionally well under oil-lubricated sliding in terms of both low CoF and limited material loss.

Figure 8.

Comparison of wear track profiles for untreated, 1.5 h, and 96 h TO samples after sliding against Al2O3 under a 5 N load in both dry and oil-lubricated (10W-40) conditions.

3.4. SEM and EDX Analysis of Wear Tracks

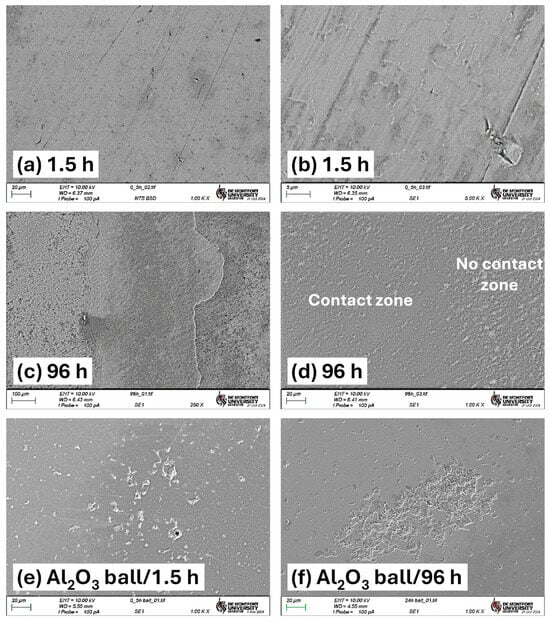

Further investigations into the wear track morphologies were conducted using SEM and EDX analysis on oil-lubricated samples oxidized for 1.5 h and 96 h. High-magnification SEM imaging and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) mapping were performed on both the sample surfaces and the corresponding alumina counterface balls. The SEM results reinforce the trends observed in optical microscopy.

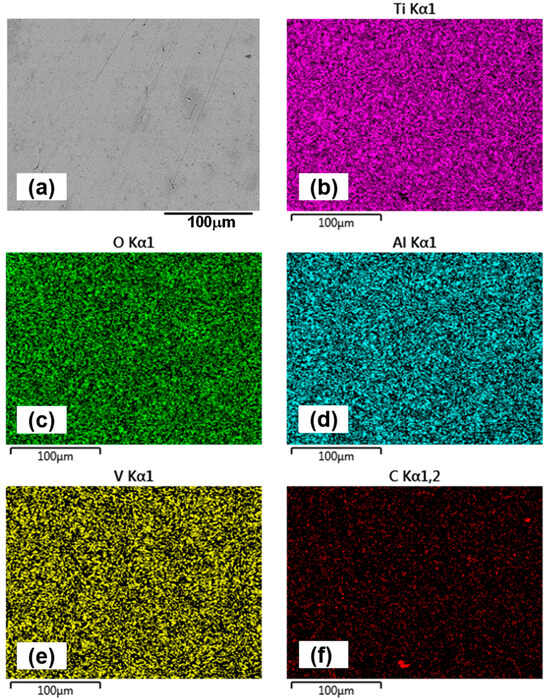

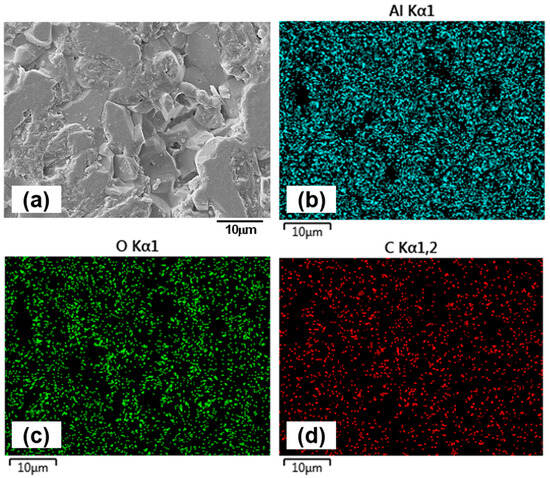

For the 1.5 h sample, wear track images (Figure 9a,b) reveal fine scratches and polishing effects within the contact region. At 5000× magnification (Figure 9b), grain boundaries are clearly visible, indicating surface smoothing due to mild abrasion. The alumina counterface (Figure 9e) shows minimal wear, though signs of grain pull-out suggest that intermittent adhesive interactions occur during sliding. EDX mapping of the 1.5 h wear track (Figure 10) confirms the presence of titanium (Ti), aluminum (Al), vanadium (V), oxygen (O), and carbon (C). No evidence of oil additive-related elements such as zinc (Zn) or sulphur (S) is found on either the wear track or the counterface, implying that tribofilm formation does not occur or is not sustained. This aligns with expectations, given that the lubricant is tailored for ferrous systems and lacks reactivity with titanium and its alloys [47,48]. EDX analysis of the counterface (Figure 11) also supports the absence of tribochemical films, consistent with prior literature [49]. The presence of carbon is likely due to residual lubricant, rather than tribofilm formation.

Figure 9.

SEM images of wear tracks for the 1.5 h and 96 h oxidized samples. (a) 1.5 h TO sample, 1000×, (b) 1.5 h TO sample, 5000×, (c,d) 96 h TO sample, (e) wear scar on alumina ball used in the 1.5 h oil-lubricated test, and (f) counterface from the 96 h oil-lubricated test.

Figure 10.

EDX mapping of the wear track surface of the 1.5 h sample after oil-lubricated sliding test, highlighting its chemical composition (a) represents the overall wear track surface at 1000× magnification, while elemental maps show: (b) titanium (Ti), (c) oxygen (O), (d) aluminum (Al), (e) vanadium (V), and (f) carbon (C).

Figure 11.

EDX mapping of the counterface ball surface after sliding against the 1.5 h sample under oil-lubricated condition, illustrating its chemical composition. (a) shows the overall ball surface at 5000× magnification, while elemental maps highlight: (b) aluminum (Al), (c) oxygen (O), and (d) carbon (C).

In the 96 h sample, Figure 9c clearly shows surface OL failure and the exposure of the subsurface propagating into adjacent non-contact regions beyond the primary wear path. High-magnification SEM imaging (Figure 9d) reveals a clear contrast between the central wear zone and the adjacent non-contact interfacial surface. Within the central contact area, surface peaks are polished, while scratch features are notably absent. This is due to the higher hardness of the ODZ and the efficient removal of wear debris by the oil, which helped to limit third-body abrasion.

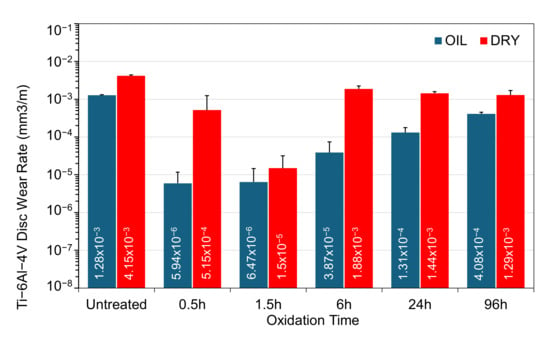

3.5. Wear Rates

Figure 12 reveals a clear trend: all samples tested under oil-lubricated conditions exhibit reduced wear rates compared to their dry, unlubricated counterparts. However, the extent of this reduction is strongly influenced by the TO duration applied to Ti-6Al-4V. The untreated sample shows only a modest reduction in wear rate with oil lubrication, which is expected, given the high and unstable friction observed in both conditions and the prominent adhesive wear seen in the track morphology.

Figure 12.

Comparison of wear rates for the untreated and TO samples subjected to sliding contact under a 5 N load, under dry and oil-lubricated conditions.

Under dry sliding, the most notable improvement in wear resistance is observed in the 1.5 h oxidized sample. Although the average coefficient of friction remains high and unstable (≈0.30), both the optical wear-track images (Figure 6) and the measured wear rates (Figure 12) demonstrate a clear reduction in material loss compared with untreated Ti-6Al-4V. In contrast, longer oxidation durations such as 24 h and 96 h provide only limited protection at the 5 N load. These samples exhibit wear rates that are only marginally lower than the untreated alloy, indicating that the formation of a thick oxide layer alone does not confer improved dry-wear resistance when the layer suffers from poor adhesion and increased brittleness.

In oil-lubricated tests, the relationship between TO time and wear performance becomes more complex. Although the 24 h and 96 h TO samples show low friction values, their wear rates are higher than expected (Figure 12). This mismatch is attributed to premature failure of the OL, which contributes to material removal. The wear track morphology (Figure 7) supports this conclusion, showing widespread delamination and removal of the OL. The 6 h sample, however, shows a much lower wear rate than its dry-tested equivalent (Figure 12). This improvement is likely due to better OL adhesion at intermediate TO durations, allowing the OL to remain attached to the subsurface ODZ. The shortest oxidation durations, 0.5 h and 1.5 h, result in the lowest overall wear rates. Compared to untreated Ti-6Al-4V under the same loading, the reduction is approximately 2.5 orders of magnitude. Microscopy confirms that oxygen diffusion into the subsurface improves surface lubricity, even without a thick oxide layer. This highlights that OL thickness is not the main factor in achieving good lubrication performance. Longer oxidation samples, even after losing their surface OL, continue to show low friction and minimal wear on the exposed ODZ (see Figure 4).

This finding is particularly important when considering stoichiometric rutile titanium dioxide, due to its tetragonal crystal structure, lacks natural shear planes. This limits its potential to act as a low-friction material. However, oxygen-deficient rutile phases, known as Magnéli phases (TinO2n−1), have been proposed as lubricious due to their altered crystal structure [50,51]. These non-stoichiometric oxides may be present in the short-time TO surfaces or at the OL–ODZ interface in longer treatments and could explain the excellent friction and wear performance observed under lubrication.

3.6. General Discussion

The tribological results presented in this study demonstrate the influence of thermal oxidation duration on the friction and wear behavior of Ti-6Al-4V under dry and oil-lubricated conditions. Short-time TO treatments (0.5 h to 1.5 h), in conjunction with oil lubrication, produced the most favorable performance, with significant reductions in both friction and wear. These improvements are attributed primarily to the presence of an ODZ beneath the surface, rather than the development of a thick rutile oxide layer. The results indicate that a thin ODZ is sufficient to achieve effective lubrication of titanium alloy with a conventional motor oil.

In contrast, samples exposed to longer TO durations (24 h and 96 h) developed thicker surface OLs, which proved to be mechanically unstable under a 5 N load. These layers showed poor adhesion to the substrate and were prone to delamination, contributing to increased wear, particularly in dry conditions. Even under lubrication, these thick OLs failed prematurely, exposing the underlying subsurface and influencing the wear response. The 6 h TO sample demonstrated more gradual film removal, suggesting improved adhesion and intermediate behavior between short-time and long-time TO treatments. In all the TO samples, effective lubrication (in terms of low friction) persists even after the OL is removed, due to the existence of the ODZ in the subsurface.

SEM and EDX analyses confirmed the absence of oil additive-derived tribofilms on both the oxidized samples and the alumina counterface. The reduction in friction under lubricated conditions is therefore attributed to boundary lubrication, in which a thin oil film is formed and sustained at the contact interface rather than through tribochemical film formation. Although no additive-derived elements (Zn, S, P) were detected by EDX, this technique cannot reliably identify ultrathin tribofilms with thicknesses below approximately 100 nm. As a result, the absence of such elements should not be interpreted as definitive evidence that no transient tribofilm formed during sliding. However, effective lubrication can still occur through adsorption-based boundary films: titanium oxides possess high surface energy and polarity, promoting physisorption and enhanced wetting of lubricant molecules [47,52]. This mechanism is consistent with the low and stable CoF (~0.06) observed during lubrication.

While the lubricant regime was not characterized using direct film-thickness measurements (e.g., Stribeck analysis or optical interferometry), the friction curves and observed wear morphologies are fully consistent with boundary-lubrication behavior. The retained wear resistance after OL removal further indicates that the subsurface ODZ continues to contribute significantly to low friction and wear under lubricated conditions. Oxygen-deficient titanium oxide phases, such as Magnéli-type structures, may also play a role, although additional work is required to confirm their presence and influence.

These findings highlight the need to optimize oxidation duration not only to develop protective surface layers but also to ensure their mechanical stability under load. To broaden the applicability of this work across different tribological systems, future studies should investigate a wider range of contact loads, counterface materials, and lubricants. Additional characterization techniques such as Raman spectroscopy, XPS or transmission electron microscopy would also be valuable for confirming the presence of Magnéli-type TiO2−x phases and clarifying their contribution to lubricity. Because direct OL–substrate adhesion measurements were not performed, interpretations of interfacial instability in this study rely on wear morphology rather than quantitative adhesion data.

Despite these limitations, the findings are directly relevant to titanium components used in aerospace, automotive, biomedical, and energy sectors. Ti-6Al-4V could be exposed to low-to-moderate contact loads under boundary-lubricated conditions in components such as actuators, sliding valves, linkages and bearing interfaces if subjected to a short duration oxidation cycle. The demonstrated ability of short-duration thermal oxidation to significantly reduce wear without the formation of tribofilms or chemical interactions with oil additives indicates a promising surface-engineering route for such systems. Since the lubrication mechanism is governed by the boundary-film and strengthening of the subsurface ODZ, the approach is suitable for applications where continuous hydrodynamic films cannot be sustained. Overall, these results provide practical guidance for selecting oxidation durations that maximize lubricated wear resistance while maintaining mechanical integrity.

4. Conclusions

- Short thermal oxidation durations (0.5–1.5 h) produced the best overall tribological performance under oil lubrication, with the lowest friction and wear. This behavior is primarily attributed to the formation of a subsurface oxygen diffusion zone (ODZ), rather than the development of a thick surface oxide layer.

- Prolonged oxidation (24–96 h) generated thicker rutile oxide layers that were mechanically unstable under a 5 N load. These layers showed poor adhesion and were prone to delamination, which limited their effectiveness in both dry and lubricated sliding.

- Under oil-lubricated conditions, no tribofilm or additive-derived elements were detected by EDX. Wear reduction therefore results from boundary lubrication acting on the oxygen-hardened subsurface, rather than from tribochemical reactions with oil additives.

- Even after removal of the surface oxide layer, the ODZ provided excellent lubricated wear resistance. This underscores that subsurface oxygen strengthening, rather than oxide-layer thickness, governs the friction and wear behavior of thermally oxidized Ti-6Al-4V in boundary lubrication.

- These findings indicate that short-duration thermal oxidation is a practical and efficient surface-engineering route for titanium components that operate under boundary-lubricated, low-to-moderate load conditions. Optimizing oxidation duration is critical to balancing surface hardening with oxide-layer stability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S., R.B. and M.A.-S.; methodology, Y.S., R.B. and M.A.-S.; software, M.A.-S.; validation, R.B., Y.S. and M.A.-S.; formal analysis, R.B. and M.A.-S.; investigation, M.A.-S.; resources, R.B. and M.A.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.B. and M.A.-S.; writing—review and editing, Y.S.; visualization, Y.S., R.B. and M.A.-S.; supervision, Y.S. and R.B.; project administration, R.B. and Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original data of this work is available from the authors upon reasonable: request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to DMU for providing the time and resources necessary to carry out this work. Additionally, they thank Shamima Choudhury for her valuable assistance with SEM imaging and EDX mapping.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Williams, J.A.; Dwyer-Joyce, R.S. Contact Between Solid Surfaces. In Modern Tribology Handbook: Principles of Tribology; Bhushan, B., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000; Volume 1, pp. 121–162. [Google Scholar]

- Popov, V.L. Contact Mechanics and Friction, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, D.G.; Eryilmaz, O.L.; Blau, P.J. Surface engineering to improve the durability and lubricity of Ti–6Al–4V alloy. Wear 2011, 271, 2006–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Wang, D.; Taylor, C.; Secker, J.; de Boer, G.; Thompson, H.; Kapur, N.; Morina, A. Adhesive layer formation and its dual role in tribological performance and surface integrity of Ti-6Al-4V: Implications for the machining process. Tribol. Int. 2025, 214, 111228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushp, P.; Dasharath, S.M.; Arati, C. Classification and applications of titanium and its alloys. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 54, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafizadeh, M.; Yazdi, S.; Bozorg, M.; Ghasempour-Mouziraji, M.; Hosseinzadeh, M.; Zarrabian, M.; Cavaliere, P. Classification and applications of titanium and its alloys: A review. J. Alloys Compd. Commun. 2024, 3, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, D.Z.; He, S.Y.; Wu, W.L. Microstructure developed in the surface layer of Ti-6Al-4V alloy after sliding wear in vacuum. Mater. Charact. 2003, 50, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, A.; Straffelini, G.; Tesi, B.; Bacci, T. Dry sliding wear mechanisms of the Ti6Al4V alloy. Wear 1997, 208, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guleryuz, H.; Cimenoglu, H. Surface modification of a Ti–6Al–4V alloy by thermal oxidation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2005, 192, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-H.; Li, C.-Y.; Chan, C.-C.; Chi, P.-C.; Shih, J.-H.; Liao, F.-Y.; Chang, S.-H. Effect of Low-Pressure Gas Oxynitriding on the Microstructural Evolution and Wear Resistance of Ti-6Al-4V Alloy. Lubricants 2025, 13, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Bell, T. Enhanced wear resistance of titanium surfaces by a new thermal oxidation treatment. Wear 2000, 238, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salihu, S.A.; Suleiman, Y.I.; Eyinavi, A.I. Classification, Properties and Applications of titanium and its alloys used in automotive industry- A Review. Am. J. Eng. Res. 2019, 8, 185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, A.; Masjuki, H.; Varman, M.; Kalam, A.; Quazi, M.; Al Mahmud, K.; Gulzar, M.; Habibullah, M. Effects of texture diameter and depth on the tribological performance of DLC coating under lubricated sliding condition. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 356, 1135–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbi, S.J.; Ferreira, J.L.d.A.; Araújo, J.A.; André, P.; Henriques, V.A.R.; Airoldi, V.J.T.; da Silva, C.R.M. The Effect of DLC Surface Coatings on Microabrasive Wear of Ti-22Nb-6Zr Obtained by Powder Metallurgy. Coatings 2024, 14, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicen, M.; Bokůvka, O.; Trško, L.; Joch, R.; Bronček, J.; Nikolić, R.; Ulewicz, R. Influence of the surface roughness, lubrication and grinding on tribological properties of the c35 steel shot-peened surfaces. Appl. Eng. Lett. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2024, 9, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Q.L.; Zheng, X.H.; Ming, W.W.; Chen, M. Friction and Wear Performance of Titanium Alloys against Tungsten Carbide under Dry Sliding and Water Lubrication. Tribol. Trans. 2013, 56, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafizadeh, A.; Ashrafizadeh, F. Structural features and corrosion analysis of thermally oxidized titanium. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 480, 849–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Dutta Majumdar, J. Surface characterization and mechanical property evaluation of thermally oxidized Ti-6Al-4V. Mater. Charact. 2009, 60, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kümmel, D.; Schneider, J.; Gumbsch, P. Influence of Interstitial Oxygen on the Tribology of Ti6Al4V. Tribol. Lett. 2020, 68, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Fedrizzi, L.; Bacci, T.; Pradelli, G. Corrosion behaviour of glow discharge nitrided titanium alloys. Corros. Sci. 2003, 45, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, L.Z.; Abd Elmomen, S.S.; El-Hadad, S. Influence of the oxidation behavior of Ti–6Al–4V alloy in dry air on the oxide layer microstructure. Chem. Pap. 2022, 76, 1627–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Bailey, R.; Zhang, J.; Lian, Y.; Ji, X. Improving oil lubrication effectiveness of Ti-Ti tribopair by thermal oxidation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 512, 132346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, F.P.; Tabor, D. The Friction and Lubrication of Solids; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Aniołek, K. The influence of thermal oxidation parameters on the growth of oxide layers on titanium. Vacuum 2017, 144, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güleryüz, H.; Çimenoğlu, H. Effect of thermal oxidation on corrosion and corrosion–wear behaviour of a Ti–6Al–4V alloy. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 3325–3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, E.; Yu, W.; Cai, Q.; Cheng, L.; Shi, J. High-Temperature Oxidation Kinetics and Behavior of Ti–6Al–4V Alloy. Oxid. Met. 2017, 88, 719–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgioli, F.; Galvanetto, E.; Iozzelli, F.; Pradelli, G. Improvement of wear resistance of Ti–6Al–4V alloy by means of thermal oxidation. Mater. Lett. 2005, 59, 2159–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, J.; Lv, K.; Zhang, W.; Ding, X.; Yang, G.; Liu, X.; Jiang, X. Surface thermal oxidation on titanium implants to enhance osteogenic activity and in vivo osseointegration. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Hu, T.; Fan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, L. Thermal oxidation behavior and tribological properties of textured TC4 surface: Influence of thermal oxidation temperature and time. Tribol. Int. 2016, 94, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.; Sun, Y. Unlubricated sliding friction and wear characteristics of thermally oxidized commercially pure titanium. Wear 2013, 308, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.; Kumar, S.; Dawari, A.; Kirwai, S.; Patil, A.; Singh, R. Effect of Temperature and Cooling Rates on the α + β Morphology of Ti-6Al-4V Alloy. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2019, 14, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siva Rama Krishna, D.; Brama, Y.L.; Sun, Y. Thick rutile layer on titanium for tribological applications. Tribol. Int. 2007, 40, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamesh, M.; Kumar, S.; Sankara Narayanan, T.S.N.; Chu, P.K. Effect of thermal oxidation on the corrosion resistance of Ti6Al4V alloy in hydrochloric and nitric acid medium. Mater. Corros. 2013, 64, 902–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrock, B.J.; Dowson, D. Isothermal Elastohydrodynamic Lubrication of Point Contacts: Part III—Fully Flooded Results. J. Lubr. Technol. 1977, 99, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatehallah, H.S.; Hammoudi, Z.S.; Zidane, L.Y. Effect of Oil Temperature on Load Capacity and Friction Power Loss in Point Contact Elasto-hydrodynamic Lubrication. Al-Nahrain J. Eng. Sci. 2019, 22, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karambakhsh, A.; Afshar, A.; Ghahramani, S.; Malekinejad, P. Pure Commercial Titanium Color Anodizing and Corrosion Resistance. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2011, 20, 1690–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, W. Influence of thermal oxidation duration on the microstructure and fretting wear behavior of Ti6Al4V alloy. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2015, 159, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sankara Narayanan, T.S.N.; Ganesh Sundara Raman, S.; Seshadri, S.K. Thermal oxidation of Ti6Al4V alloy: Microstructural and electrochemical characterization. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2010, 119, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Deepak, K.B.; Muzakkir, S.M.; Wani, M.F.; Lijesh, K.P. Enhancing tribological performance of Ti-6Al-4V by sliding process. Tribol. Mater. Surf. Interfaces 2018, 12, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Bell, T.; Mynott, G. Surface engineering of titanium alloys for the motorsports industry. Sports Eng. 1999, 2, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Raman, S.G.S. High Temperature Sliding Wear Behaviour of Ti6Al4V Thermal Oxidised for Different Oxidation Durations. Met. Mater. Int. 2023, 29, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echávarri Otero, J.; De La Guerra Ochoa, E.; Chacón Tanarro, E.; Del Río López, B. Friction coefficient in mixed lubrication: A simplified analytical approach for highly loaded non-conformal contacts. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2017, 9, 168781401770626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniołek, K.; Kupka, M.; Barylski, A. Sliding wear resistance of oxide layers formed on a titanium surface during thermal oxidation. Wear 2016, 356–357, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obadele, B.A.; Andrews, A.; Mathew, M.T.; Olubambi, P.A.; Pityana, S. Improving the tribocorrosion resistance of Ti6Al4V surface by laser surface cladding with TiNiZrO2 composite coating. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 345, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezugwu, E.O.; Wang, Z.M. Titanium alloys and their machinability—A review. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 1997, 68, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Wong, Y.S.; Rahmath, Z. Machinability of Titanium Alloys. JSME Int. J. 2003, 46, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, F.; Cui, K.; Tian, B.; Dong, R.; Fan, M. Interfacial adsorption and tribological response of various functional groups on titanium surface: In-depth research conducted on the lubricating mechanism of liquid lubricants. Tribol. Int. 2023, 189, 108885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Li, P.; Yang, Z.; Sun, J.; Zhang, R.; Fu, B. Study on the evolution mechanism and concentration regulation of dynamic gradient tribofilm in ionic liquid/nanodiamond synergistic lubrication of titanium alloys. Carbon 2025, 243, 120566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Al-Shan, M.; Bailey, R.; Sun, Y. Effect of Counterbody Material on the Boundary Lubrication Behavior of Commercially Pure Titanium in a Motor Oil. Lubricants 2024, 12, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardos, M.N.; Hong, H.-S.; Winer, W.O. The Effect of Anion Vacancies on the Tribological Properties of Rutile (TiO2-x), Part II: Experimental Evidence. Tribol. Trans. 1990, 33, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langlade, C.; Vannes, B.; Sarnet, T.; Autric, M. Characterization of titanium oxide films with Magnéli structure elaborated by a sol–gel route. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2002, 186, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, A.-E.; Avilés, M.-D.; Pamies, R.; Bermúdez, M.-D.; Carrión-Vilches, F.-J.; Sanes, J. Ecofriendly Protic Ionic Liquid Lubricants for Ti6Al4V. Lubricants 2022, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).