Abstract

This paper reviews the current state of dynamic sealing technologies, examining the challenges faced by conventional sealing methods under complex working conditions, such as high temperature, high pressure, and corrosive environments. It also provides a concise overview of the status and developmental trends in sealing inspection technologies. From the perspective of obstruction mechanisms, this study reinterprets the concept of sealing science by redefining the classification of sealing types based on solid-phase medium obstruction, fluid hydrostatic and hydrodynamic obstruction, fluid pumping obstruction, fluid energy dissipation obstruction, and fluid impact obstruction. Comparative analyses of sealing structures across these obstruction mechanisms are presented. The sealing technology based on fluid impact medium obstruction, newly proposed by this paper, represents an innovative sealing approach. It offers distinct advantages such as zero wear, structural simplicity, and high stability, addressing longstanding issues in high-speed, large-clearance non-contact seals, including low leakage suppression efficiency, system complexity, and poor stability. Since its introduction, this novel sealing structure has garnered significant attention and recognition from both the academic and industrial sealing communities. With the potential to revolutionize the field, this groundbreaking sealing design is poised to lead the next wave of technological advancements in sealing science.

1. Introduction

Sealing science is an interdisciplinary field dedicated to the study of sealing structure design, sealing mechanisms, and their engineering applications. As a critical branch of sealing science, dynamic sealing technology has evolved into a multidisciplinary domain encompassing mechanical engineering, materials science, and control engineering. The primary function of dynamic sealing technology is to prevent or minimize the leakage of internal media in rotating components. Despite the relatively low cost proportion of sealing devices within equipment and systems, they often play a pivotal role. For instance, failure analysis of centrifugal compressors reveals that the failure rate of lubrication and sealing systems ranges from 55% to 60%, while their cost proportion is merely 20% to 40% [1]. According to estimates by American researchers, effective application of sealing technologies could save approximately USD 300 million annually in the operation of steam turbines, with dynamic sealing contributing significantly to this benefit [2,3].

Throughout history, sealing failures have led to significant safety incidents. For example, the 1979 Three Mile Island nuclear accident in the United States was triggered by a nuclear main pump shaft seal failure, causing a reactor leak with cleanup costs exceeding USD 1 billion. The 1986 Challenger space shuttle disaster resulted from a rocket booster seal failure, causing an explosion that tragically took the lives of seven astronauts. These examples underline the critical role of reliable sealing systems, especially in environments demanding zero leakage and high operational reliability.

It is evident that dynamic sealing technology is critical to the reliability and safety of high-end equipment. With the ever-growing demand for zero leakage, extended service life, and high reliability in modern industries, innovation and advancements in dynamic sealing technology have emerged as a research direction of significant strategic importance.

2. Applications of Sealing Technology Across Industries

Dynamic sealing technology, as a crucial technology for the reliable operation of mechanical equipment, is widely applied in aerospace, automotive manufacturing, chemical processing, and other industries. In aerospace engines, air film sealing technology notably enhances engine efficiency, offering significant advantages in high-temperature and high-speed conditions [4]. This innovation effectively reduces both fuel consumption and emissions. Sarawate et al. [5] conducted leakage tests on metal W-shaped sealing rings in industrial gas turbines, providing critical data to support sealing technologies in aerospace engines. In the chemical industry, dynamic sealing technology is essential for the safe operation of various rotary equipment. Xu Wenguang et al. [6] experimentally validated the reliability of sealing technology in alkali pumps and similar pump systems. Hashimoto et al. [7] investigated the sealing characteristics of thrust bearings under turbulent and fluid inertia conditions. Inoue et al. [8] examined non-contact end-face sealing behavior in high-speed water pumps, providing critical theoretical and empirical insights for the design of high-pressure pump seals. In the automotive manufacturing sector. The petroleum extraction industry, with its stringent sealing performance requirements, also benefits from advancements in dynamic sealing technology. Wang Chao [9] developed an integrated tool for sealing detection and adjustment, addressing unique challenges in sealing applications under specific operational conditions and providing innovative sealing solutions for the oil and gas industry. Overall, dynamic sealing technology plays a crucial role in aerospace, chemical processing, automotive manufacturing, and petroleum extraction by enhancing equipment efficiency, safety, and production quality to meet the demands of complex operating environments.

3. Advances and Trends in Sealing Technology

3.1. Optimization and Innovation in Sealing Technology Under Extreme Conditions

The demand for “zero leakage” and “zero spillage” sealing solutions continues to grow, particularly in high-stress, corrosive environments such as those found in petrochemical applications. In these environments, sealing media are often highly corrosive, flammable, explosive, or toxic, with potential leaks posing severe risks of personal injury and property damage. Consequently, numerous researchers have focused on optimizing sealing technologies to function effectively under such extreme conditions. Jackson et al. [10] investigated the wear resistance of novel solid lubricants under high-temperature and high-pressure conditions, achieving extended seal lifetimes. Wang et al. [11] developed composite-coated sealing materials specifically designed to meet high-pressure and corrosion-resistant requirements in the chemical industry. Huang [12] verified the stability of nanoparticle-based lubricants in sealing materials under extreme pressure, whereas Brown et al. [13] introduced a high-temperature gas seal design utilizing gas dynamic pressure effects. Chen et al. [14] evaluated the durability of composite ceramic seals in corrosive environments, while Singh [15] examined self-lubricating materials based on graphite and molybdenum disulfide under high-temperature and high-pressure conditions. Collectively, these studies provide essential support for advancing sealing technology in extreme conditions, thereby broadening its potential applications.

3.2. Intelligent Monitoring of Sealing Conditions

In practical engineering applications, sealing leaks generally show noticeable changes only when failure occurs, making it difficult for traditional detection methods to accurately assess seal health [16]. Seals are frequently replaced pre-emptively to avoid failure; however, prolonged use until failure could result in severe production accidents and potential personal injury [17]. From the standpoint of safety management and cost control, real-time monitoring and assessment of sealing surface frictional conditions have become crucial concerns [18]. Advances in intelligent sensing technology have markedly improved the ability to monitor seal performance, proving invaluable in both laboratory settings and increasingly in practical engineering applications.

3.2.1. Temperature Monitoring Technologies

The health of sealing systems is crucial for production safety and equipment reliability, making the accurate and real-time monitoring of sealing interfaces a prominent research focus in the field of sealing technology. Traditional detection methods often fail to provide effective early warnings before failures occur, particularly under complex working conditions where leakage from seals is frequently subtle, rendering fault prediction exceptionally challenging. To better evaluate the operational status of seals, temperature monitoring technology has emerged as a vital diagnostic tool and has been widely applied in assessing sealing performance. By measuring real-time temperature variations in the fluid surrounding the mechanical seal and friction pairs, this technique effectively reflects the operating state of sealing components, especially the thermal effects near friction and sealing contact surfaces.

Zhu Xiaoping et al. [19] reviewed common methods for measuring mechanical seal temperatures, covering contact-based methods, such as resistance thermometers and thermocouples, and non-contact methods, including ultrasonic and infrared thermometry. Resistance thermometers and thermocouples are categorized as contact-based measurements, whereas ultrasonic and infrared methods are non-contact. WILL T P [20] used thermocouples to measure the temperature of fluids surrounding mechanical seals and friction pairs, whereas DOANE J C et al. [21] embedded multiple thermocouples in the stationary rings of mechanical seals, enabling effective analysis of thermal gradient distribution across varying rotational speeds. Hu Xiaoyun [22] described a thermocouple-based temperature measurement approach in detail; the sensor design demonstrates high linearity, facilitating rapid temperature field mapping across sealing rings by integrating multi-point temperature data with computational methods. Additionally, as early as 1991, REUNGOAT D et al. [23] used a scanning infrared camera to measure the temperature distribution on end-face seals, and in 2001, Bai Yingduo et al. [24] applied infrared thermography in air film seal experiments, addressing challenges in installing conventional thermocouples on high-speed, counter-rotating shafts. Overall, contact-based methods, such as thermocouples and resistance temperature detectors (RTDs), offer the advantages of low cost and high measurement accuracy by directly embedding sensors to monitor the temperature of sealing components. However, these methods are often challenged by installation complexity and susceptibility to mechanical vibrations or high rotational speeds. In contrast, non-contact methods, such as infrared thermography and ultrasonic techniques, address the difficulties of sensor installation in high-speed equipment and enable the rapid acquisition of temperature field distributions. Nevertheless, their accuracy may be limited by environmental interferences, and the associated equipment costs are relatively high. These technologies provide effective means for evaluating sealing performance, yet they also face challenges in improving reliability and accuracy under complex working conditions.

3.2.2. Acoustic Emission Technology

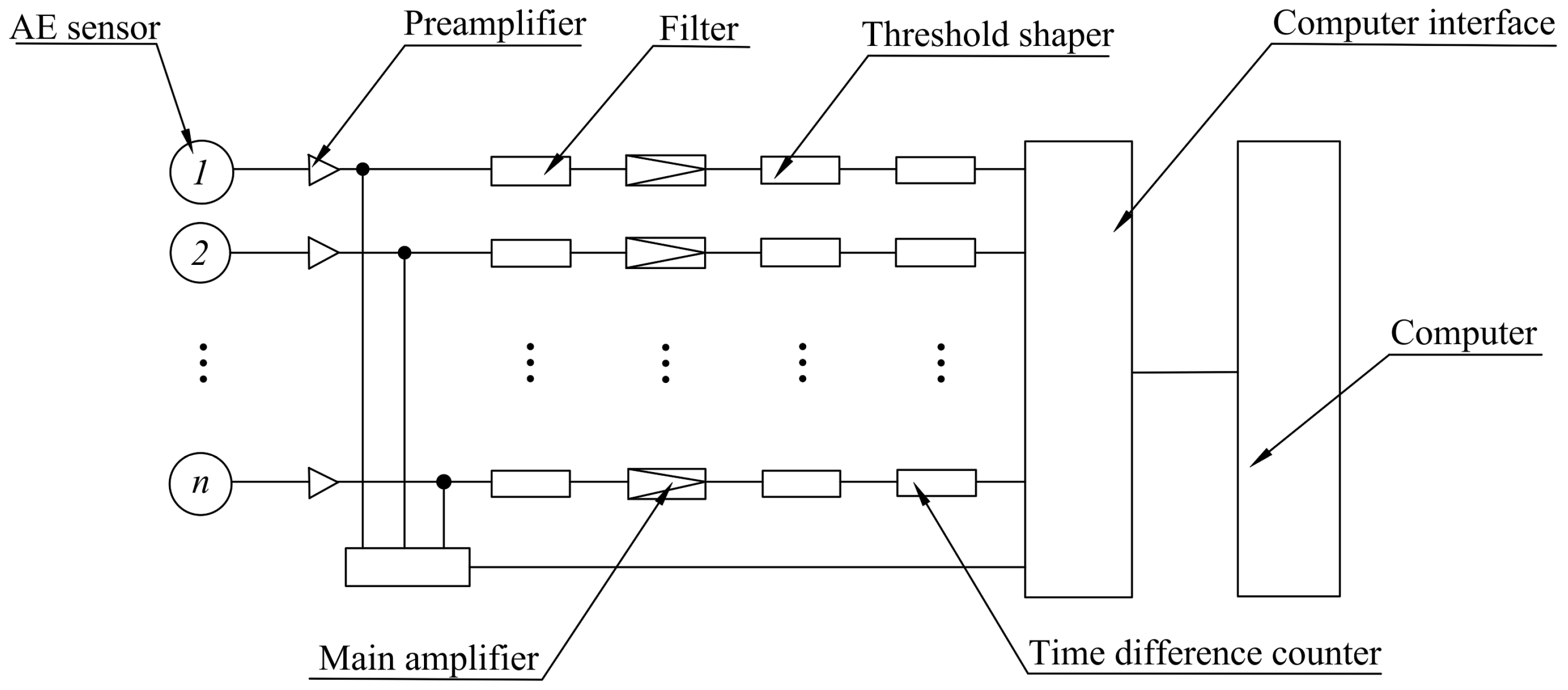

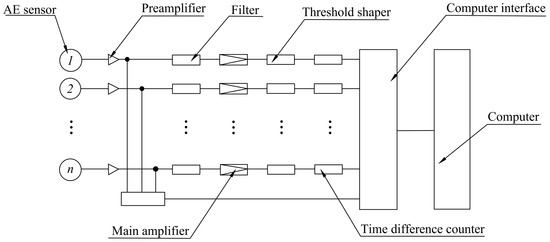

The application of contact-based temperature monitoring techniques faces significant challenges under high-speed or complex operating conditions. Although non-contact methods, such as infrared thermometry, overcome the installation difficulties inherent in traditional contact-based approaches, their accuracy can be easily compromised by external interference. In this context, the development of technologies that offer higher reliability, interference-free operation, and real-time monitoring has become particularly critical. Acoustic emission (AE) technology has emerged as a promising solution. It enables real-time monitoring of mechanical seal conditions by detecting stress fluctuations during the sealing process. The fundamental principle is illustrated in Figure 1: After the AE sensor detects the signal, it is amplified by a preamplifier, filtered to remove noise, and further amplified by the main amplifier. The signal is then passed through a threshold shaper to select valid signals. A time-difference counter is used to locate the source of the acoustic emission, and the data are subsequently transmitted to a computer for analysis, which facilitates the identification of seal failure modes and their locations.

Figure 1.

Principles of typical acoustic emission systems.

MIETTINEN J [25] investigated sliding contact processes in the mechanical seals of a 15 kW centrifugal pump, discovering that AE signal amplitudes were reduced during leakage conditions compared to normal operation but increased substantially under dry friction. Building on this, HOLENSTEIN A P [26] proposed employing AE sensors to monitor friction in large pumps used in thermal power plants. The AE signal-based early-warning system they developed effectively distinguished between normal, dry friction, and leakage conditions. Additional research by FAN Yibo et al. [27] confirmed that AE technology can detect leakage, dry friction, and cavitation phenomena in mechanical seals. BOARD C B [28] used AE technology to diagnose seal friction in gas turbine engines, identifying primary AE sources as contact friction, impact, and dynamic load variations between rotating components. MBA D et al. [29] employed piezoelectric AE sensors (100 kHz to 1 MHz) to monitor friction conditions in main shaft seals of large steam turbine generators. In 2013, TOWSYFYAN H. [30] emphasized that AE detection has become the primary method for diagnosing failures in mechanical seals. He underscored the need to distinguish AE signals from seals versus other components or background noise, recommending advanced time-frequency signal analysis to address this challenge. He also developed an experimental setup using water as the sealing medium [31], with two AE sensors (100 kHz to 1 MHz) mounted on the sealing ring to conduct sampling frequency experiments. Evidently, the application of acoustic emission (AE) technology overcomes the limitations of traditional temperature monitoring methods, enabling real-time detection of leaks, dry friction, and other potential faults within the sealing system without disrupting the operation of the equipment. However, despite its significant advantages, AE signals may still be susceptible to interference from background noise and signals from other components of the equipment, which can affect accuracy. Therefore, the adoption of advanced signal processing and analytical techniques, along with the optimization of sensor configurations, becomes crucial to enhancing the effectiveness of AE technology in seal monitoring applications.

3.2.3. Multi-Sensor Fusion for Real-Time Monitoring

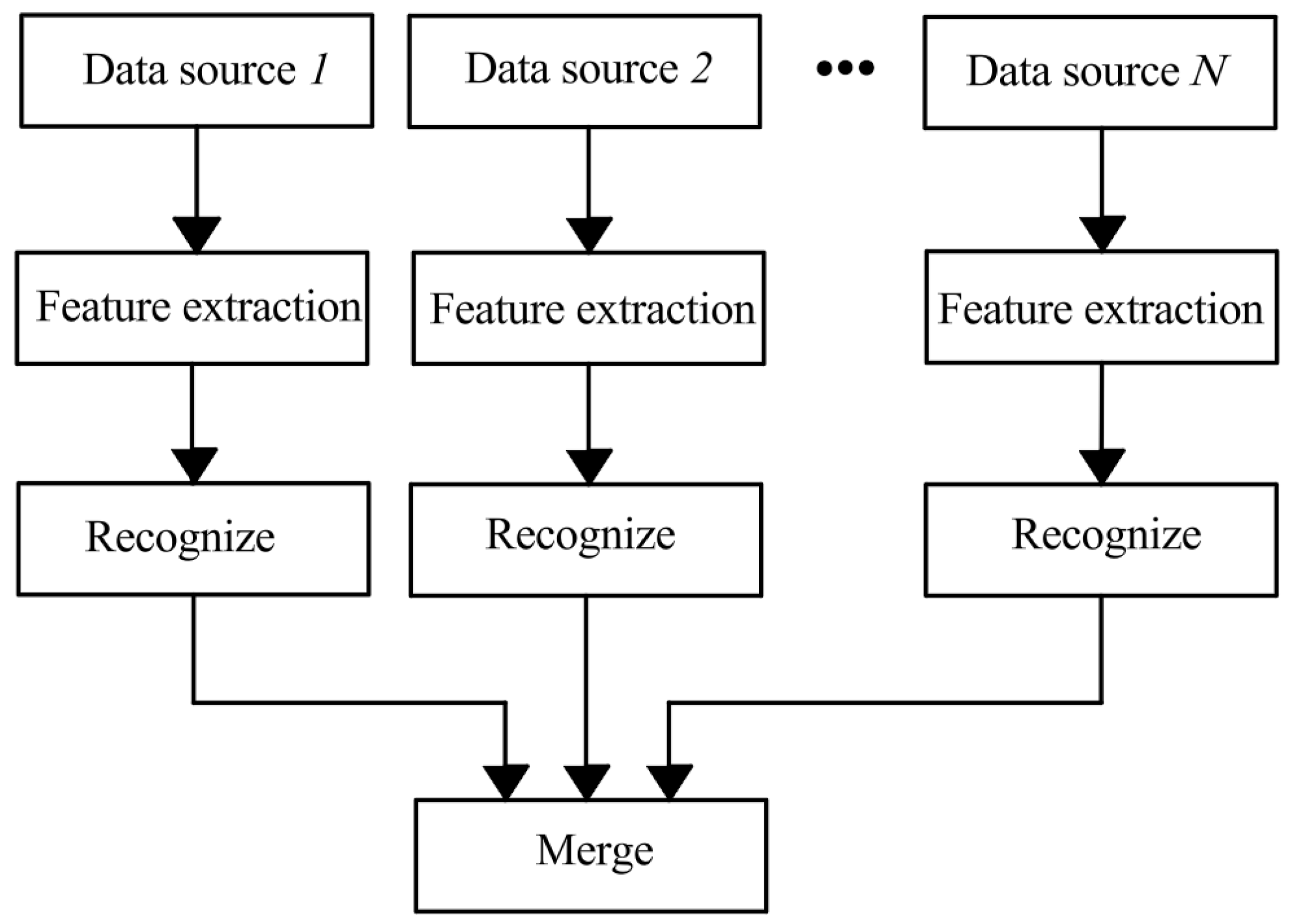

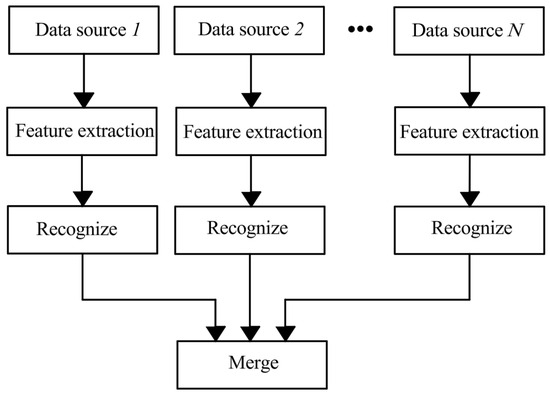

As discussed, both temperature monitoring and acoustic emission (AE) technologies have certain limitations in mechanical seal detection. Temperature monitoring still faces numerous challenges regarding accuracy and reliability under high-speed and complex operating conditions, while AE signals are highly susceptible to interference from environmental noise and other equipment components. Therefore, relying on a single sensor for monitoring often fails to provide a comprehensive and reliable assessment of seal conditions. Real-time multi-sensor fusion monitoring technology has emerged as a key development trend in the field of seal detection, as illustrated in Figure 2. This technology combines various types of sensors (such as temperature, acoustic emission, optical fiber, infrared, etc.) to perform a comprehensive analysis of data from multiple dimensions. For instance, by integrating AE sensors with temperature sensors, it becomes possible to monitor stress fluctuations while tracking temperature variations, thereby providing a multi-dimensional evaluation of the seal system’s condition. Multi-sensor fusion not only compensates for the limitations of individual sensing technologies but also enables more efficient and precise real-time monitoring under complex conditions. Especially in challenging environments, such as high temperatures, high pressures, and rapid rotations, it significantly enhances the diagnostic capability for mechanical seal systems.

Figure 2.

Multi-sensor fusion monitoring technology.

Zhang Erqing et al. [32] identified contact states and initiation speeds in nuclear electric pressurized sealing systems via AE sensor data analysis, laying a foundation for seal monitoring in nuclear applications. Chen Yuan et al. [33] employed eddy current sensors to monitor real-time variations in oil film thickness on sealing end faces, supplying critical frictional surface condition data to enable precise seal health assessments. Pfefferle et al. [34] utilized rotor-embedded thermocouples to indirectly measure the frictional temperature of seals, addressing challenges in temperature monitoring under high-stress conditions. In laboratory settings, Demiroglu et al. [35,36] employed infrared thermography to accurately measure internal temperature distributions within seals, validating the technique’s reliability in high-temperature environments. Ruggiero et al. [37,38] developed a real-time monitoring system based on fiber optic sensors, enabling the continuous tracking of internal temperature and strain states in seals to support robust health monitoring under dynamic operating conditions. Overall, the integration of multi-sensor fusion in modern seal monitoring incorporates various technologies, such as temperature, AE, fiber optic, and infrared sensors. This fusion approach facilitates real-time monitoring and precise diagnostics of seal conditions, significantly enhancing equipment safety and reliability in complex operating environments.

4. Classification and Current State of Dynamic Sealing Technology

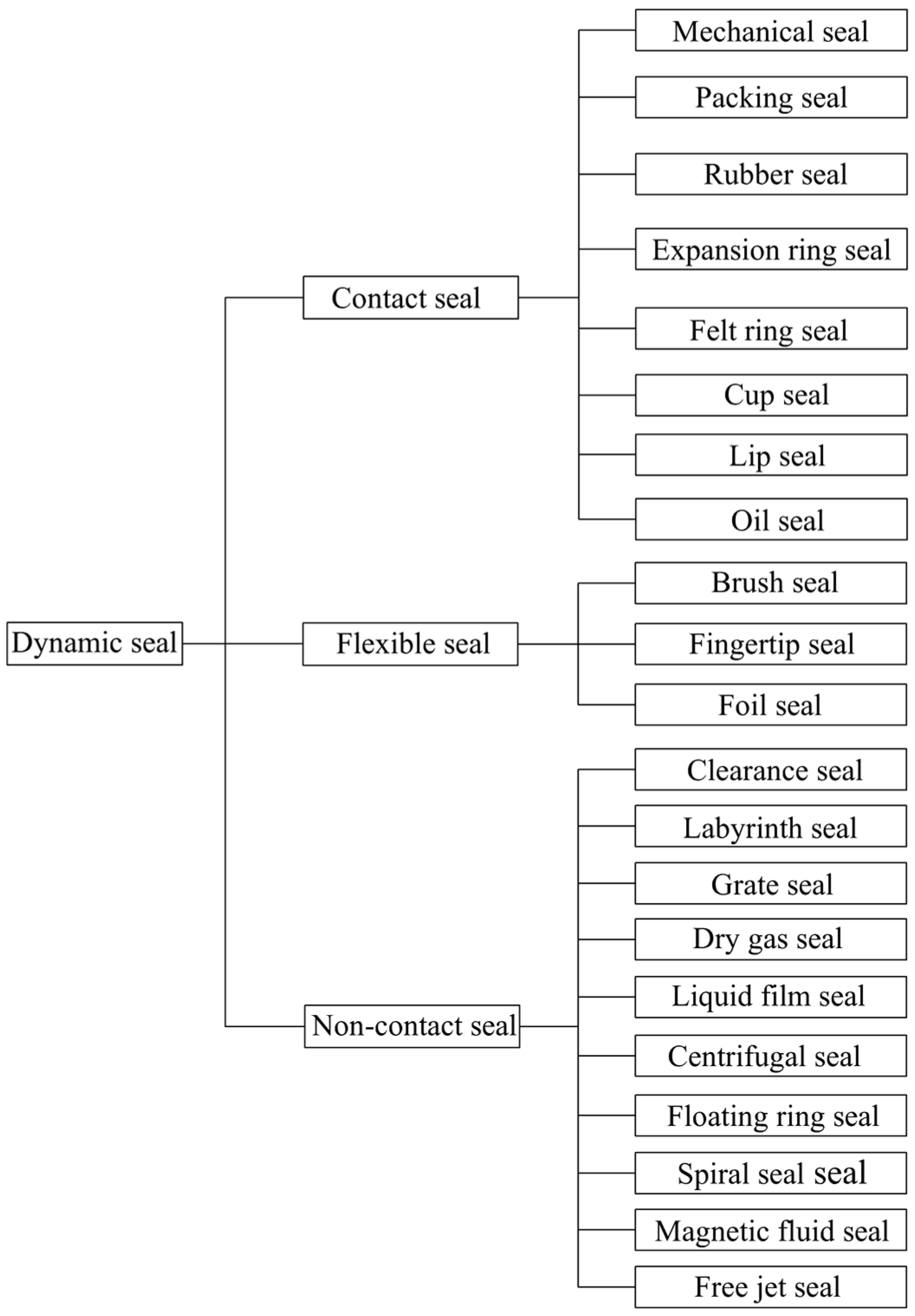

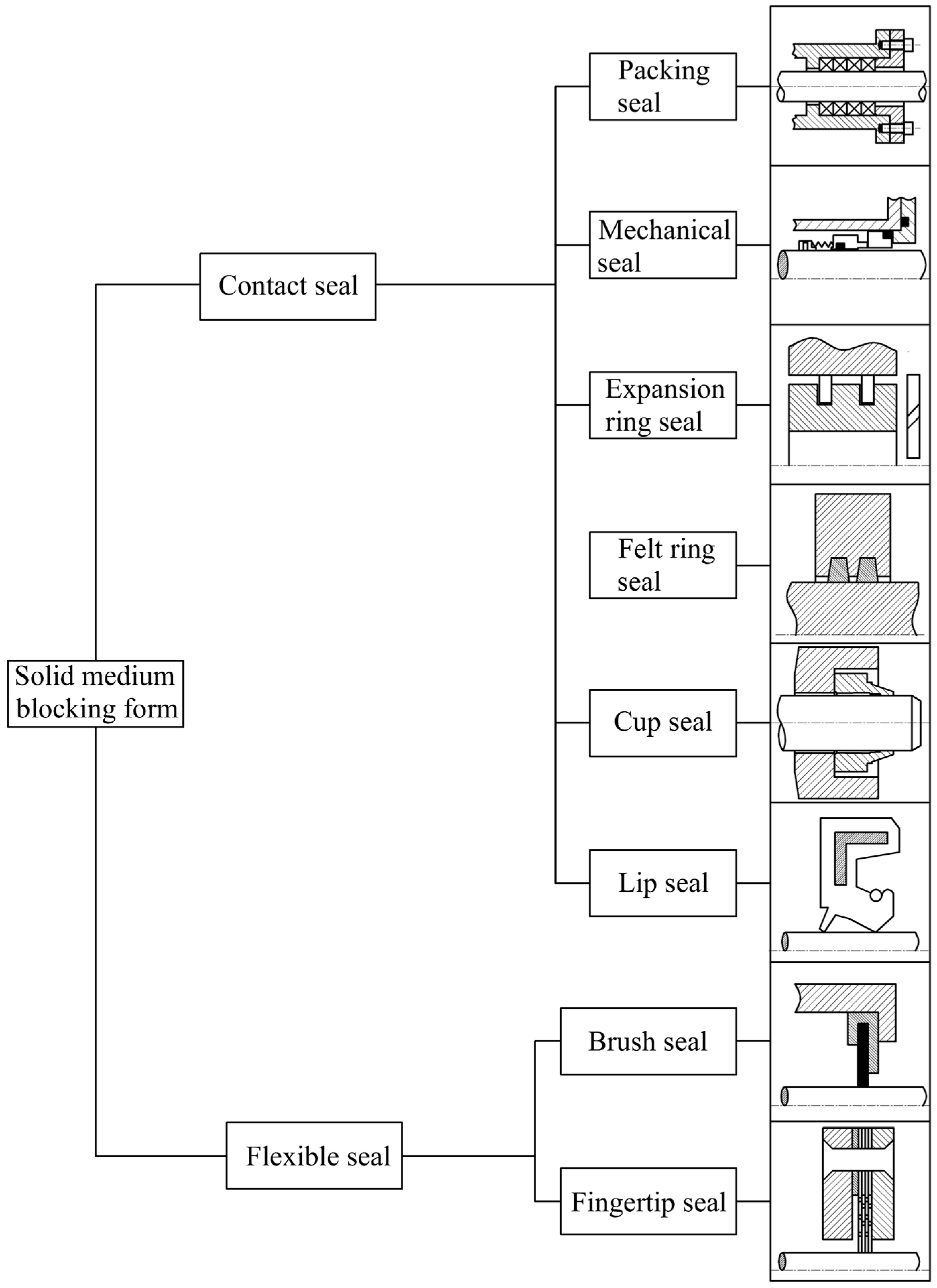

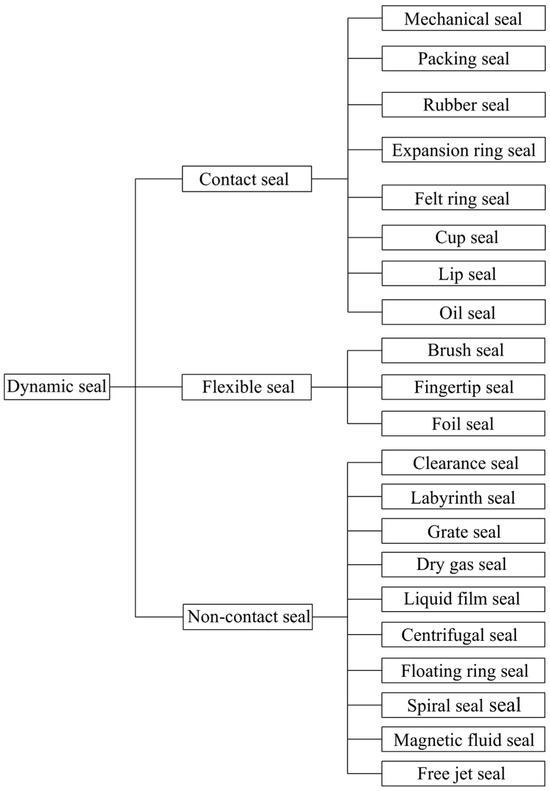

Dynamic seals are primarily used in scenarios where relative motion exists at the sealing interface and represent a critical sealing form in modern industrial equipment. As shown in Figure 3, dynamic seals can be further classified into the following three categories: ① Contact seals: These seals achieve sealing through direct contact between sealing surfaces, with common forms including mechanical seals, packing seals, felt seals, cup seals, and oil seals. Contact seals are widely used in pumps and rotating machinery, offering excellent sealing performance; however, they are susceptible to wear under high-temperature and high-pressure conditions. ② Flexible seals: Flexible seals use elastic materials or structures to accommodate surface deformations, achieving a dynamic sealing effect. Common flexible seals include brush seals, finger seals, and foil seals, suitable for industrial applications requiring larger sealing surfaces and reducing frictional losses to some extent. ③ Non-contact seals: Non-contact seals maintain a tiny gap between sealing surfaces using fluid dynamics or specialized structural designs, thereby avoiding wear. Non-contact seals include clearance seals, labyrinth seals, tooth seals, dry gas seals, liquid film seals, centrifugal seals, floating ring seals, spiral seals, magnetic fluid seals, and free-jet seals. These seals provide high durability and are commonly applied in high-speed rotating equipment to minimize energy losses [39,40].

Figure 3.

Traditional seal classification.

Non-contact sealing technology, defined by the lack of direct solid-phase contact, offers notable advantages of low wear and extended lifespan, primarily relying on frictional resistance, throttling, or hydrodynamic effects to achieve effective sealing. This technology is widely applied in advanced equipment such as compressors, steam turbines, aircraft engines, nuclear power plant coolant pumps, and marine propulsion systems, meeting the demands for high-efficiency, low-maintenance seals [41]. However, most non-contact seals rely heavily on the dynamic pressure generated by powered components, making their performance closely tied to main shaft speed. When operating at low speeds or during shutdown, sealing efficacy decreases substantially, often requiring auxiliary shutdown seals to maintain system integrity. This auxiliary structure complicates the design and upkeep of non-contact sealing systems, while increasing maintenance demands and costs. Consequently, enhancing the lifespan and structural stability of sealing devices, simplifying system design, and reducing maintenance cycles while ensuring sealing performance have become key research priorities in sealing technology. Simultaneously, advancements in sealing materials, design optimization, and interdisciplinary research have emerged as pivotal strategies for advancing sealing technology capabilities.

5. Methods for Sealing Technology Improvement

Bai et al. [42] conducted a study combining numerical simulation and experimental validation, demonstrating that novel composite materials significantly enhance corrosion and wear resistance in high-pressure fluid sealing systems, rendering them suitable for high-pressure equipment in the oil and gas sector. Xu Wenguang et al. [7] optimized seal design and material selection to improve sealing efficiency and durability in alkali pumps, achieving leak-free operation in highly corrosive environments. Feng et al. [43] extended seal lifespan through lightweight design and structural improvements in sealing systems, supporting environmental goals within the automotive sector. Integrated diagnostic sealing technologies have become widely applied in the oil and gas industry. Wang Chao [9] developed an integrated seal inspection tool capable of diagnosing and adjusting sealing performance in eccentric layered injection wells, ensuring safe operation. Jones [44] introduced an ultrasonic sensor-based diagnostic tool that detects downhole seal failures in real time and provides adjustment recommendations, ensuring equipment integrity. These tools underscore the essential role of cross-disciplinary technologies in advancing sealing innovations. Kim et al. [45] explored non-contact seal applications in the turbopumps of liquid rocket engines, proposing an air-film non-contact design that enhances both operational efficiency and seal reliability. Müller et al. [46] investigated the impact of the coupling between normal and in-plane elastic responses on the tribological properties in frictional contacts. They proposed that the coupling induced by compressibility affects sealing performance by altering the gap topology. This provides a crucial theoretical foundation for the development of new materials and structural designs. Aderikha et al. [47] studied the effects of RF plasma-modified PBO fibers and carbon black on the structure and tribological properties of PTFE composites, while Fenghua Su et al. [48] examined the performance of PTFE composites filled with nano-TiO2 and glass fibers. Burris et al. [49] and Yang Y.L. et al. [50] respectively examined the wear behavior of PTFE composites incorporating nano α-Al2O3, flake graphite, and serpentine, while Xie et al. [51] enhanced the wear resistance of PEEK/PTFE composites by adding potassium carbonate whiskers. The application of these high-performance materials has significantly improved seal durability, providing strong support for technological advancements within the sealing industry.

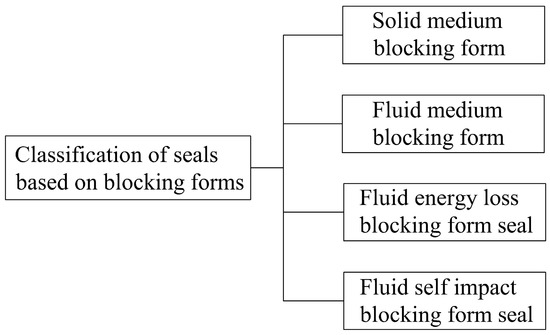

6. Classification of Sealing Technology Based on Obstruction Mechanisms

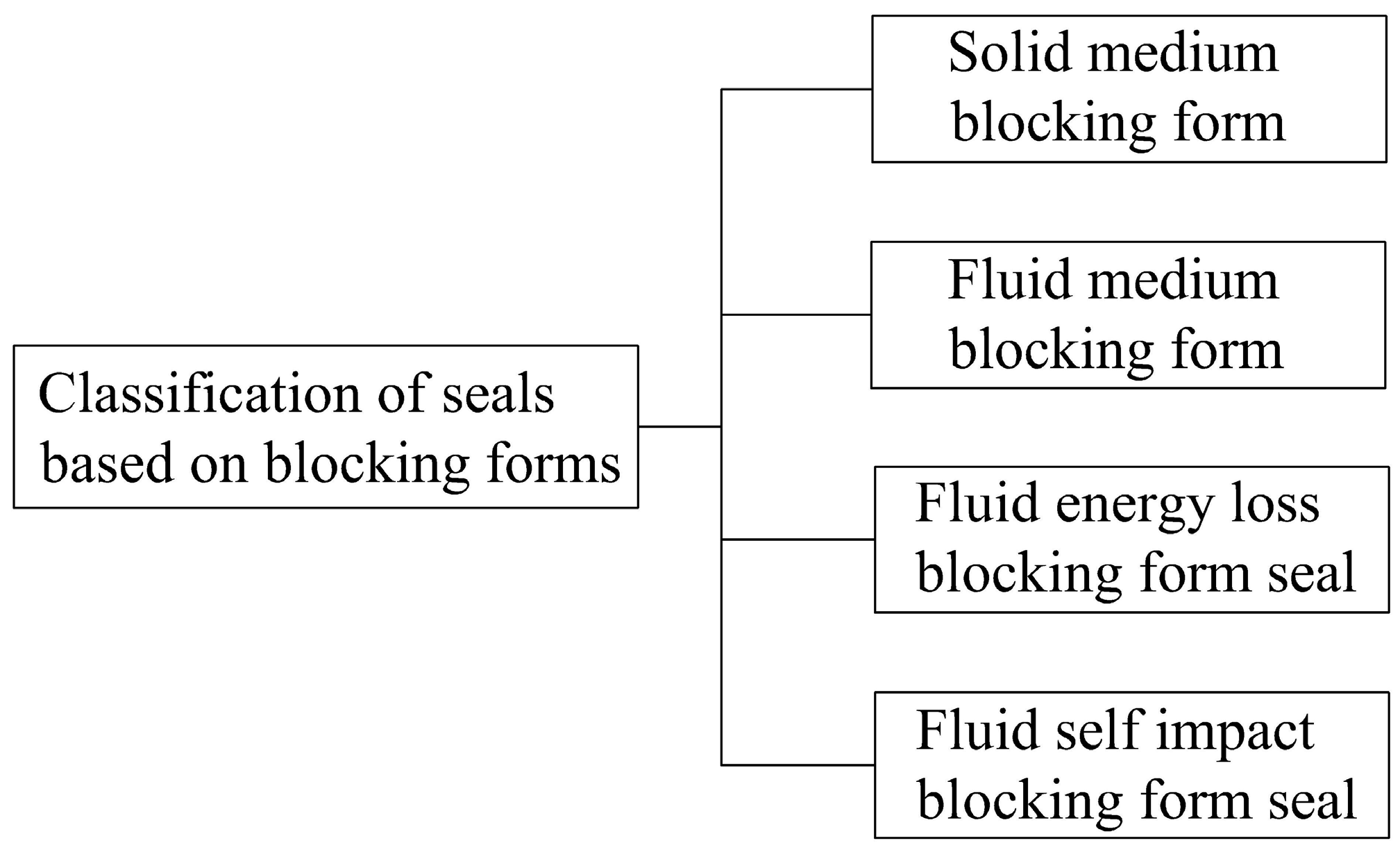

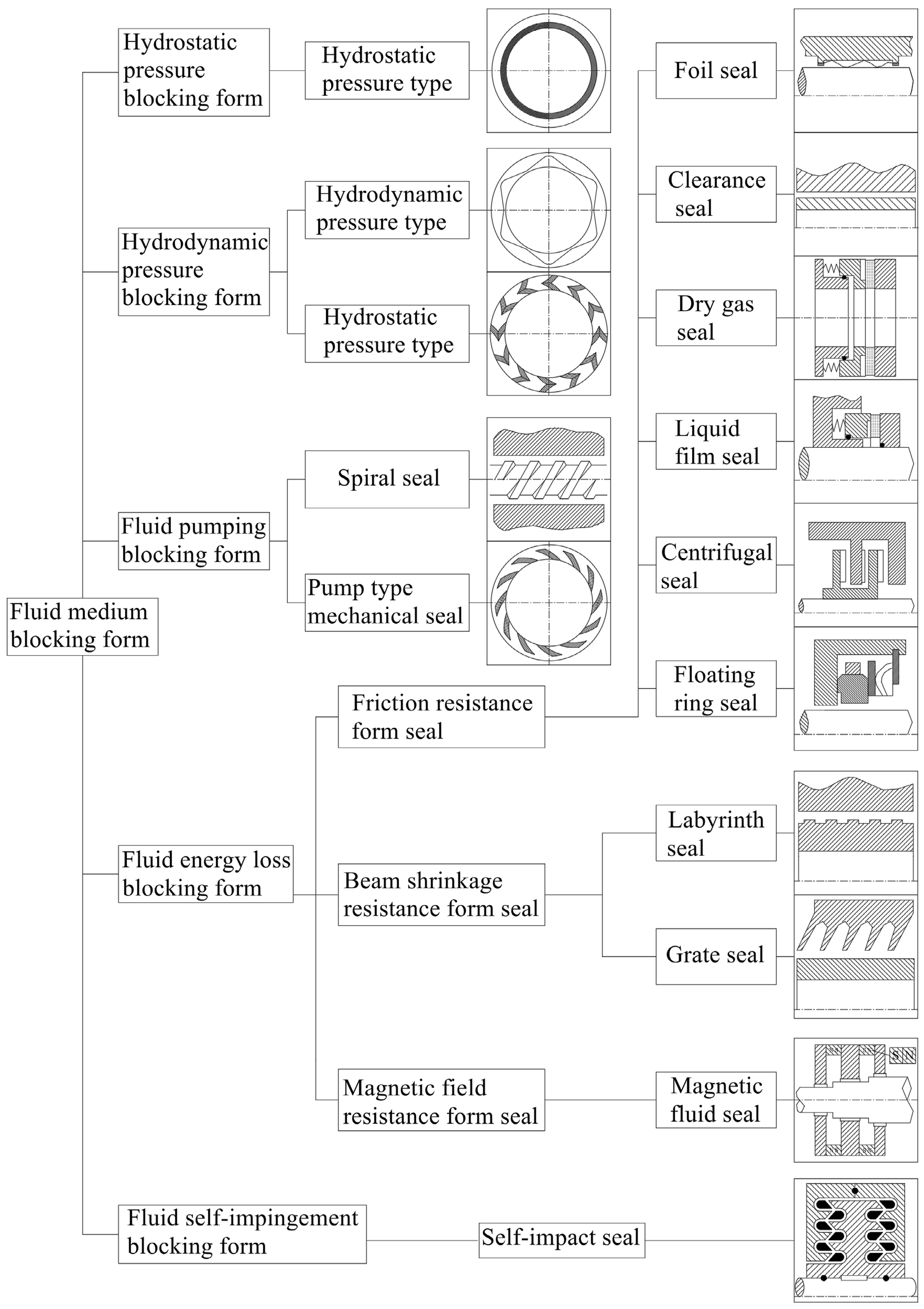

The core function of dynamic seals is to prevent the exchange of substances between the sealed space and the external medium, provided there is relative motion between the moving and static components. The fundamental sealing form is determined by the selected blocking medium and its introduction method. Therefore, classifying dynamic seals based on the form of the blocking medium is more targeted. As shown in Figure 4, this paper classifies dynamic seal types based on the blocking form into the following categories: solid-phase medium blocking form, fluid medium blocking form, fluid energy dissipation blocking form, and fluid self-impact blocking form.

Figure 4.

Classification of seals based on blocking forms.

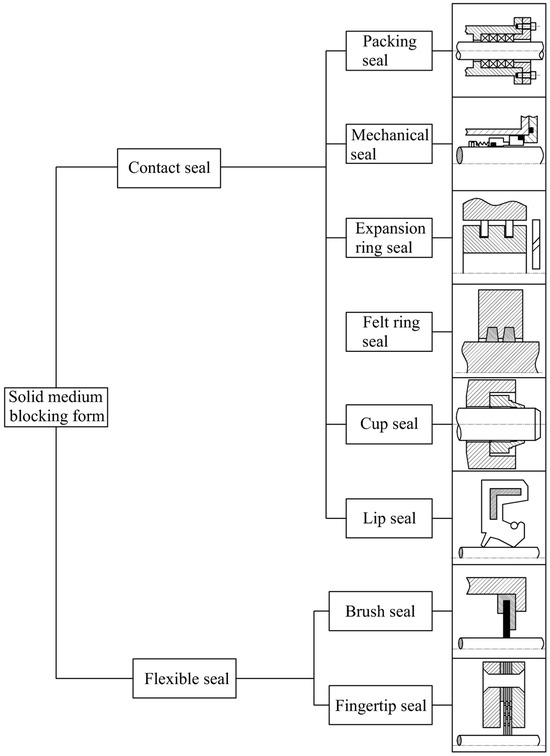

6.1. Solid-Phase Obstructive Media

Solid-phase blocking medium seals primarily prevent leakage through direct contact and compression between solid materials. These seals mainly include contact-type seals such as packing seals, mechanical seals, gasket seals, felt seals, lip seals, and oil seals, as shown in Figure 5. Flexible seals, such as brush seals and finger seals, also fall under the solid-phase media classification [52]. Solid-phase obstructive media seals present notable advantages. Direct contact of the solid obstructive medium effectively prevents leakage of gasses or solid particles, ensuring stable and reliable sealing performance. These seals have simple structures, are easy to maintain, and can be replaced promptly through wear monitoring, with relatively low manufacturing costs. They are well-suited to standard materials and manufacturing processes. However, this type of seal presents certain limitations. Solid contact may lead to significant power consumption and wear, limiting lifespan under extreme conditions, such as high pressure, high speed, or high temperature. Additionally, increased energy consumption lowers overall operational efficiency [53].

Figure 5.

Solid medium blocking form seal classification.

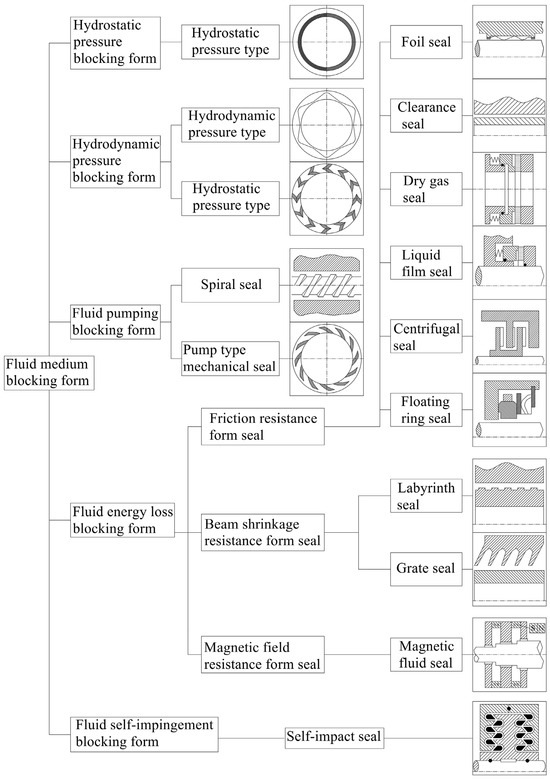

6.2. Fluid-Phase Obstructive Media

Sealing through solid-phase medium blocking achieves effective leakage suppression via direct contact and compression of solid materials. This method features a simple structure and low cost, exhibiting high stability under standard operating conditions. However, its limitations become apparent under extreme conditions such as high pressure, high speed, or elevated temperatures, where it suffers from high energy consumption and significant wear. In contrast, fluid medium blocking seals leverage the dynamic pressure, static pressure, or pumping characteristics of fluids to form a stable fluid barrier or lubrication film between sealing surfaces. This non-contact sealing approach effectively eliminates energy losses and wear caused by direct contact. It not only reduces operational energy consumption but also significantly extends the service life of sealing components, making it particularly well-suited for demanding conditions such as high-speed and high-pressure environments. The superior performance of fluid medium blocking in both sealing efficiency and energy savings offers a critical solution for the advancement of high-performance sealing technologies. Figure 6 categorizes sealing forms based on the various blocking mechanisms of fluid mediums.

Figure 6.

Fluid medium blocking form seal classification.

6.2.1. Fluid Dynamic and Static Pressure Obstructive Sealing

Fluid dynamic and static pressure obstructive seals employ dynamic, static, or combined hydrodynamic and hydrostatic pressure principles to achieve advanced sealing performance and are widely applied across liquid, gas, and powder sealing applications [54]. Common non-contact mechanical seals in this category include conical hydrostatic, wavy hydrodynamic, and dual spiral groove hybrid designs, such as dry gas seals and liquid film seals. By forming a lubricating film between sealing surfaces using fluid dynamic or static pressure, these seals effectively prevent direct contact, significantly reducing frictional losses and enhancing sealing efficiency. Relying on a fluid film with sufficient pressure to block medium leakage, this type of seal is particularly suited to high-speed, high-pressure, and other demanding conditions, making it ideal for high-speed rotating and reciprocating equipment. These seals lower energy consumption and extend the service life of sealing components, thereby reducing replacement frequency and maintenance costs. However, this technology imposes strict requirements on the alignment and structural rigidity of sealing surfaces, as any deformation [55] or vibration [56] can directly affect sealing performance. Furthermore, fluid dynamic and static pressure seals are highly sensitive to environmental cleanliness, particularly to dust and particulates, requiring operation in controlled, clean environments [57]. Additionally, these seals require precise control of pressure, temperature, and lubrication parameters, increasing maintenance complexity and costs. Complex maintenance and repair protocols are essential to ensuring stability, requiring strict parameter control and regular servicing to maintain reliability and longevity [58].

6.2.2. Fluid Pumping Obstructive Sealing

Fluid pumping obstructive sealing technology prevents leakage paths by using a specially designed structure to redirect fluid entering the sealing gap back into the sealing chamber. This technology utilizes a grooved design with a pumping function that converts the rotational kinetic energy of the shaft into fluid pressure potential energy, creating a localized high-pressure barrier between sealing surfaces. Common types of pumping seals include spiral groove seals and pumping mechanical seals. This sealing structure is relatively simple and reliable; as a non-contact seal, it offers low energy consumption, making it ideal for high-speed rotating equipment. However, a primary limitation of this type of seal is its strong dependence on rotational speed; it fails to establish the necessary high-pressure barrier at low speeds, which compromises sealing effectiveness [59]. Additionally, fluid pumping seals exhibit limited adaptability to axial or radial movement, making them less effective in applications with frequent displacement variations. The manufacturing and maintenance costs of these seals are relatively high, requiring a careful balance between reliability and cost in their application.

6.2.3. Fluid Energy Dissipation Obstructive Sealing

Fluid energy dissipation obstructive sealing technology achieves sealing by dissipating the kinetic energy of fluid within the sealing channel. This sealing method uses various mechanisms to reduce fluid kinetic energy, including frictional resistance (e.g., foil seals, clearance seals, dry gas seals, liquid film seals, centrifugal seals, floating ring seals, and spiral seals), flow contraction resistance (e.g., labyrinth seals, tooth seals), thermal expansion (e.g., labyrinth and tooth seals), and magnetic resistance (e.g., magnetic fluid seals). The effectiveness of this type of seal is closely related to the gap size within the leakage channel: smaller gaps result in greater energy dissipation, enhancing sealing performance, while larger gaps increase leakage. Non-contact seals such as clearance seals, labyrinth seals, and tooth seals are particularly suited to high-speed and ultra-high-speed applications and are widely used in high-speed equipment such as gas turbines. However, due to the relatively low throttling efficiency of these seals, they are frequently combined with other sealing methods to improve overall effectiveness [60]. For instance, the performance of magnetic fluid seals depends on the properties of the magnetic fluid; however, achieving effective sealing at high pressure and high speed remains challenging, often requiring combination with other seal types [61,62]. Other types, such as foil seals [63], centrifugal seals [64], floating ring seals [65], and spiral seals [66], rely on sufficient rotational speed to establish a stable fluid film for effective sealing. In general, the low throttling efficiency of fluid energy dissipation obstructive seals is a key factor limiting their performance and hindering system simplification. To optimize their application and enhance overall efficiency, these seals are generally used in conjunction with other sealing technologies to meet the demands of complex operational conditions.

6.2.4. Fluid Self-Impact Obstructive Sealing

To address the high power consumption, limited adaptability to extreme conditions, and speed dependency of traditional contact fluid seals, as well as the structural complexity and high maintenance costs of non-contact fluid sealing systems, the authors propose a novel self-impact obstructive sealing structure inspired by the passive fluid control principles of the Tesla valve and its unidirectional flow properties. Utilizing the Tesla valve’s design concept, the authors extend its planar flow structure into a three-dimensional tubular channel to achieve unidirectional leakage suppression from the high-pressure to the low-pressure side, thereby mitigating reverse fluid leakage.

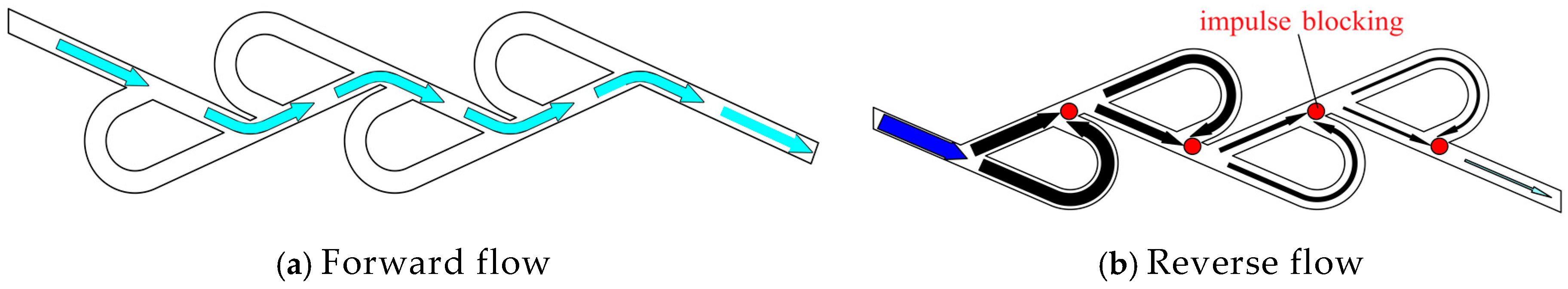

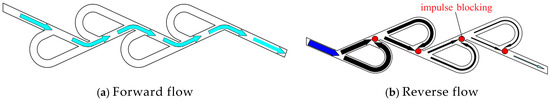

Figure 7 presents the structural diagram of a planar Tesla valve, renowned for its unique unidirectional flow characteristics. When fluid flows in the forward direction (Figure 7a), it bypasses all wing-shaped obstacles, allowing for a smooth and uninterrupted passage. Conversely, during reverse flow (Figure 7b), intense impact blocking occurs at the intersections of the curved and horizontal channels, significantly impeding fluid progression. This resistance increases markedly with the number of wing-shaped obstacles. Leveraging this property, we developed a novel self-impact sealing structure, as illustrated in Figure 8, optimizing the fluid flow path within the sealing system to allow passage exclusively under unidirectional pressure. This design effectively minimizes energy consumption while enhancing sealing performance and stability. The innovative self-impact sealing structure demonstrates significant potential for practical applications, particularly in scenarios demanding suppression of reverse leakage and improved sealing efficiency.

Figure 7.

Principle of unidirectional conductivity of Tesla valve.

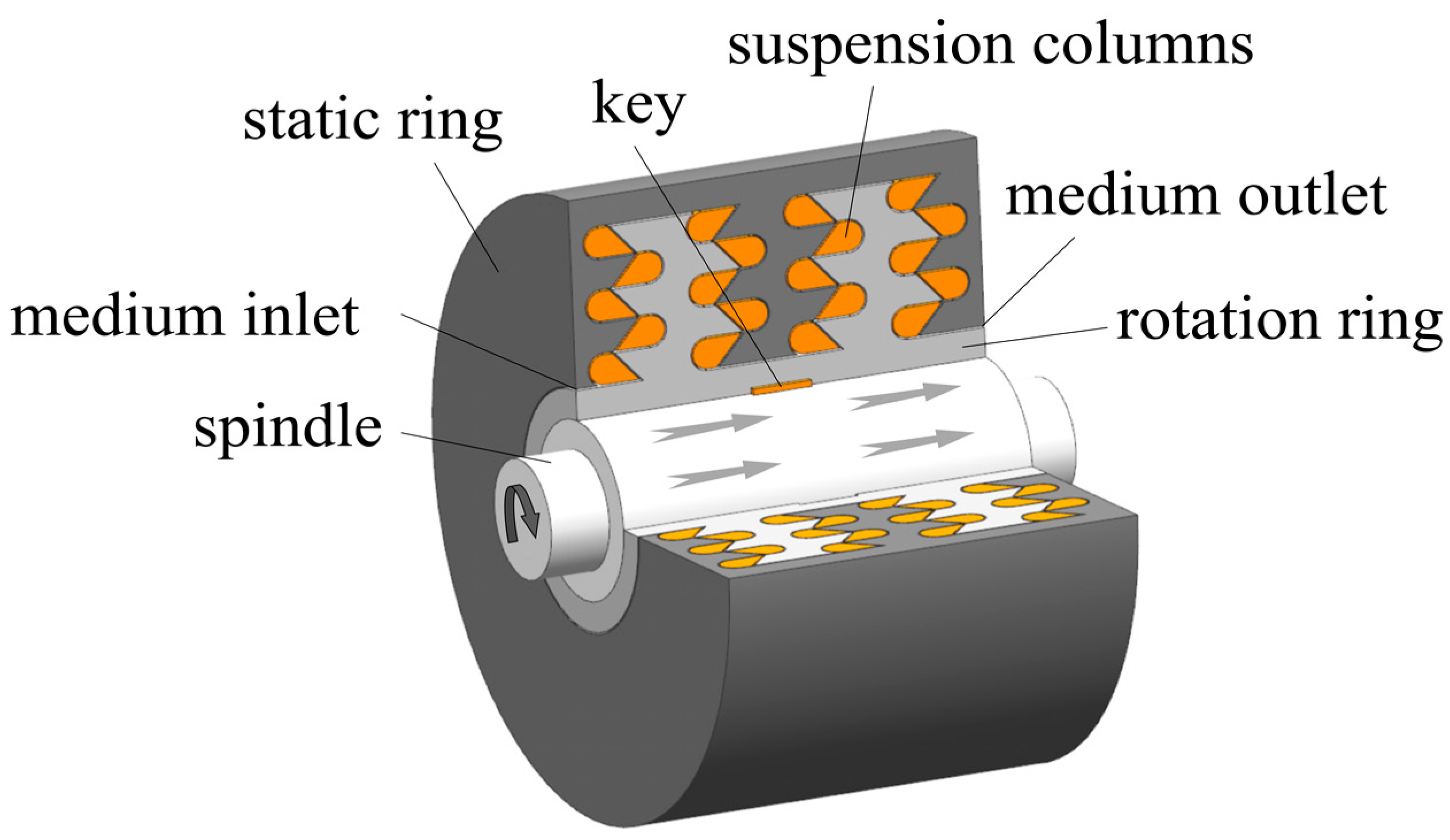

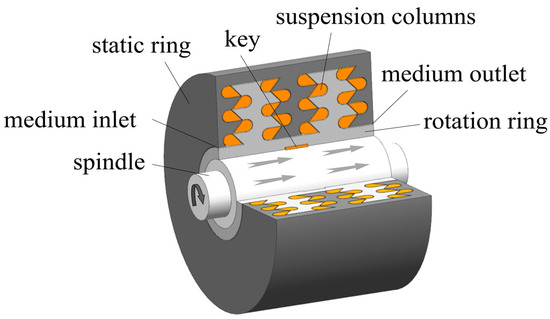

Figure 8.

Self-impacting seal structure [67].

Overall, solid-phase blocking mechanisms achieve leakage prevention through solid contact and compression, characterized by their structural simplicity and low manufacturing costs. However, under high-pressure, high-speed, and high-temperature conditions, they incur significant power consumption and wear, which limits their service life and energy efficiency. In contrast, fluid hydrodynamic and hydrostatic blocking mechanisms form a lubricating fluid film between sealing surfaces, making them suitable for demanding conditions such as high speed and high pressure. These mechanisms effectively reduce frictional losses and extend operational lifespan but require high standards for structural rigidity, cleanliness, and precise parameter control, resulting in considerable maintenance costs.

Fluid pumping blocking mechanisms rely on specialized structures to recirculate the fluid into the sealing chamber, creating a high-pressure fluid barrier. While suitable for high-speed applications, their sealing efficacy heavily depends on rotational speed, rendering them ineffective at low speeds and incapable of accommodating frequent displacement variations. Fluid kinetic energy dissipation mechanisms achieve sealing by consuming the fluid’s kinetic energy, making them appropriate for ultra-high-speed applications. However, their throttling efficiency is low, often necessitating integration with other sealing methods.

By comparison, fluid self-impact blocking mechanisms utilize the unidirectional flow properties of Tesla valves to optimize fluid pathways, effectively suppress reverse leakage, significantly reduce energy consumption, and enhance sealing performance and stability. This technology demonstrates high sealing efficiency and holds considerable application potential under conditions requiring high pressure, high speed, and reverse leakage suppression. It is particularly advantageous for complex scenarios demanding superior sealing performance and energy conservation, offering distinct innovative advantages. Table 1 summarizes the sealing characteristics of various blocking mechanisms.

Table 1.

Comparison of the characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages of various sealing forms.

7. Novel Self-Impact Sealing Technology

Building on the principles of passive fluid obstruction and Tesla valve design, the authors performed a three-dimensional macro reconstruction of the micro sealing channel, resulting in a novel sealing structure model. This innovative design leverages a near-millimeter-scale three-dimensional tubular flow field to achieve non-contact sealing under specific operating conditions, while rigid fixation of the inner and outer rings enhances the seal’s resistance to axial and radial vibrations.

In performance evaluations, comparative tests used dry gas sealing conditions as a leakage benchmark. The results show that, under identical conditions, the novel seal achieves leakage levels comparable to dry gas seals even with sealing gaps several to dozens of times wider. This substantial advantage underscores the potential of the novel seal to enhance non-contact seal stability, providing strong support for high-demand sealing applications.

7.1. Fluid Obstruction Mechanism

The obstruction mechanism of gas media in self-impact sealing has been studied in depth, yet the mechanism for liquid media remains unclear. In gas-based self-impact seals, gas behavior within the three-dimensional channel is influenced by three primary effects: ① Thermodynamic effect: Within the Tesla valve flow path, gas particles collide, converting kinetic energy into thermal energy, increasing temperature. This rise in temperature raises gas viscosity and reduces flow velocity, enhancing the sealing effect. The thermodynamic effect is the primary mechanism by which self-impact seals achieve their sealing function. ② Flow contraction effect: Under pressure differentials and impact, gas undergoes compression, momentarily increasing flow velocity. Although this effect can have a minor adverse impact on sealing, it intensifies subsequent impact obstruction, positively contributing to overall sealing effectiveness. ③ Frictional effect: At high rotational speeds, friction between the gas and both the rotor and stationary surfaces converts kinetic energy into internal energy, increasing temperature and further reducing flow velocity. This impedes gas movement and enhances sealing performance. These three effects collectively determine the flow characteristics and sealing efficacy of gas within the three-dimensional channels of self-impact seals. The thermodynamic effect is critical for achieving sealing, while the frictional effect strengthens seal integrity. Although the flow contraction effect briefly accelerates flow, it amplifies subsequent impact obstruction, contributing positively to overall sealing performance. Although the obstruction mechanism for liquid media in self-impact seals has not been thoroughly investigated, it is inferred that the frictional effect may play a more significant role for liquids. This characteristic may be crucial in designing liquid-based self-impact seals, necessitating further research to clarify its precise operating mechanisms.

7.2. Geometric Model

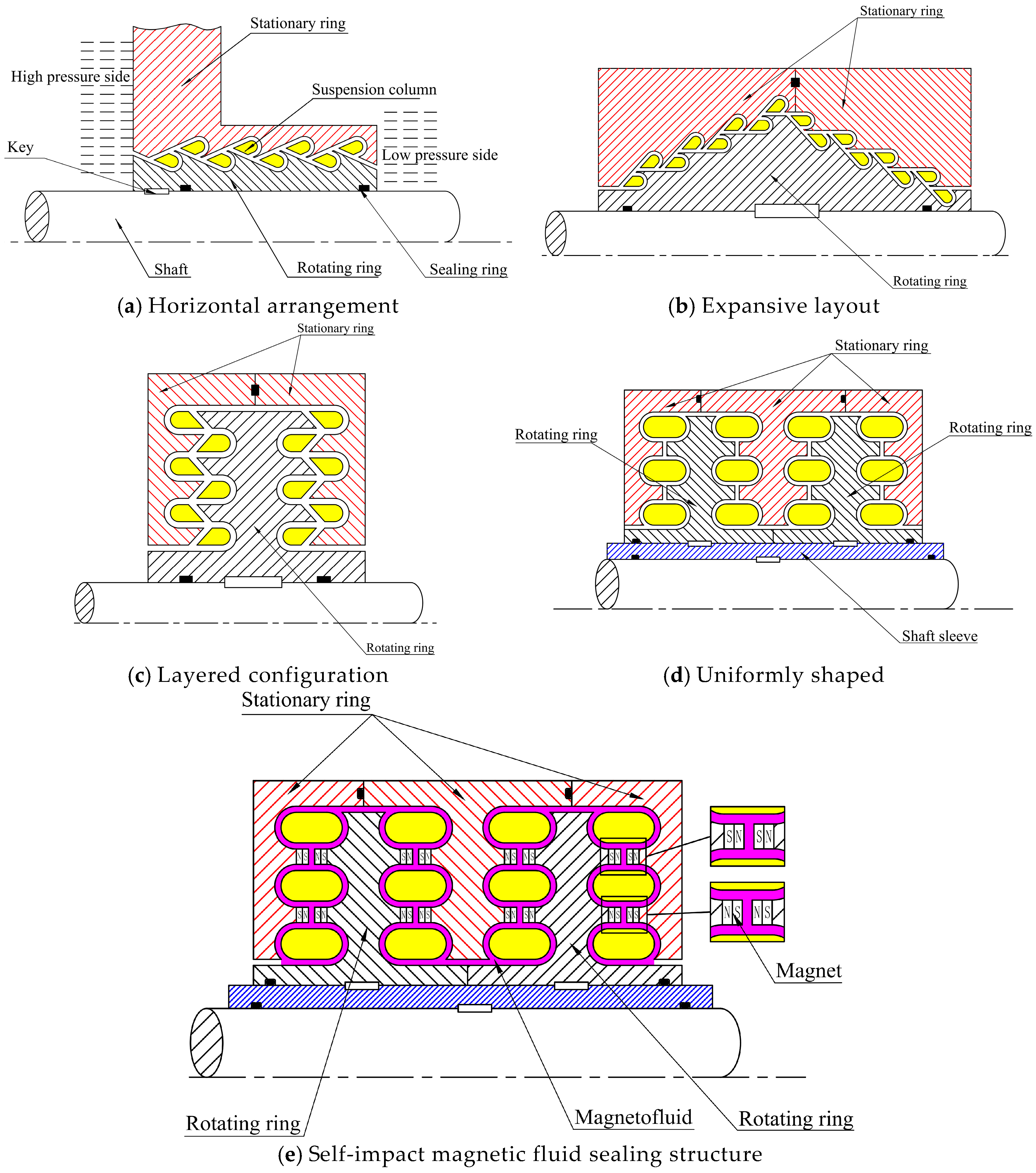

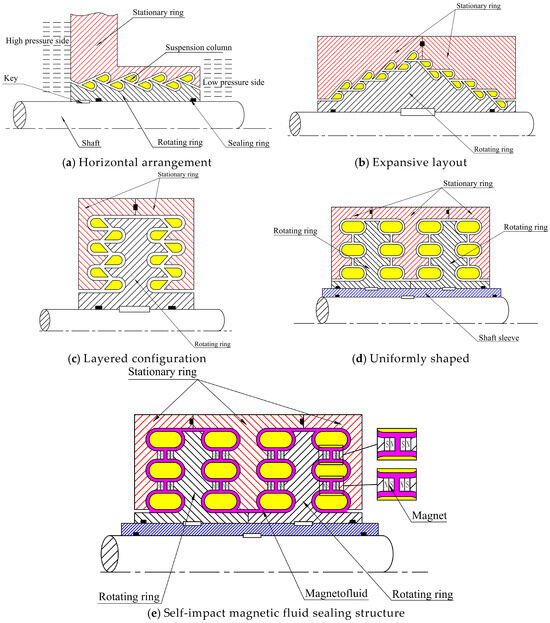

Figure 9 illustrates several typical structural configurations of self-impact seals, which have evolved from horizontal layouts to more advanced designs such as expanded configurations [68] and stacked structures [69] to simplify installation and enhance staging efficiency. To reduce manufacturing costs, the winged cantilever structure has been further optimized into a regular disk-shaped cantilever design. Building on these advancements, a novel self-impact magnetic fluid sealing structure [70], as depicted in Figure 9e, has been recently proposed, significantly improving the pressure resistance of existing ferrofluid seals. In these designs, the cantilever elements can be affixed to the rotating ring using threaded connections, bolts, or spot welding, with appropriate gaps maintained among the rotating ring, stationary ring, and cantilevers. This arrangement ensures stable fluid control and effective sealing during operation. These structural innovations enhance the applicability and economic viability of self-impact seals, offering critical technological support for the adoption of novel high-efficiency sealing solutions.

Figure 9.

Several structural forms of self-impacting seals.

In the seal structures shown, the cantilevered pillars are secured to the rotating ring by point welding or similar techniques, with a defined gap maintained between the rotating ring, stationary ring, and cantilevers. This gap ensures stable fluid control and effective sealing performance during operation. These enhancements improve the applicability and economic feasibility of self-impact seals, providing essential technical support for the adoption of advanced, high-efficiency sealing technologies.

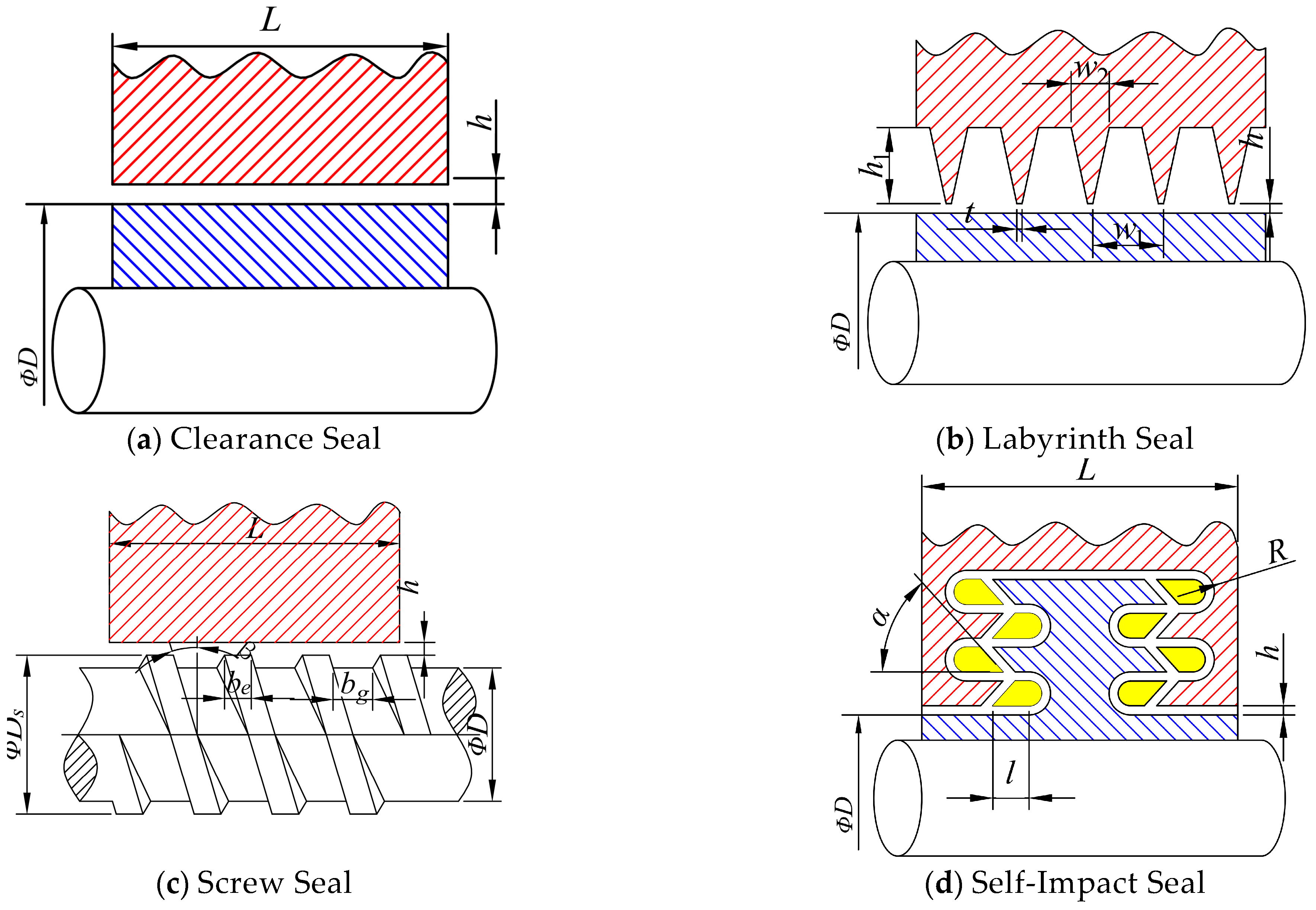

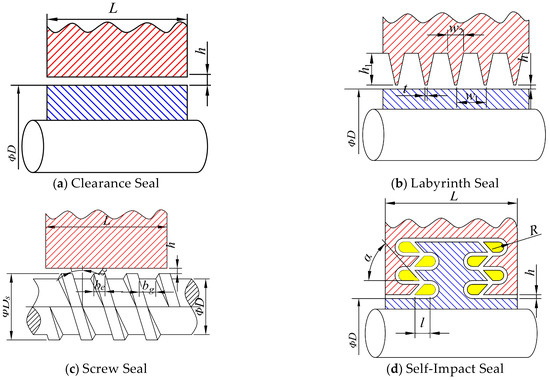

7.3. Performance Comparison

A comparative analysis of various non-contact sealing types shown in Figure 10 yields the conclusions summarized in Table 2: compared to other non-contact seals, self-impact seals exhibit a significant advantage in leakage suppression. This characteristic provides self-impact seals with unique adaptability and competitiveness in applications requiring high sealing performance.

Figure 10.

Model structure of each non-contact seal.

Table 2.

Comparison of calculation results of leakage of several non-contact seals [68].

Self-impact seals offer several distinct performance advantages, including efficient throttling, zero leakage, high stability, strong adaptability, an extended service life, and minimal maintenance requirements [71]. The structural design allows high-pressure media to undergo progressive throttling upon entering the seal, theoretically achieving “zero leakage” by increasing the number of throttling stages, significantly enhancing sealing efficiency and system reliability. Compared to traditional dry gas seals, self-impact seals maintain a significantly larger sealing gap at the same leakage level, with a rigid gap design that provides superior stability and reduces the risk of failure due to seal breakdown. By converting kinetic energy into internal energy through the fluid’s self-impact mechanism, self-impact seals effectively dissipate energy, enhancing sealing effectiveness and optimizing performance. Additionally, they accommodate variations in pressure, rotational speed, and geometric parameters, addressing the demands of diverse sealing applications in complex environments. With efficient throttling and a stable, rigid gap design, self-impact seals offer extended service life and low maintenance requirements, while the simplified structure reduces overall operational and maintenance costs.

8. Conclusions and Outlook

Dynamic sealing technology, as a critical foundational element in modern industrial equipment, directly impacts the safety, stability, and operational lifespan of machinery. With rapid advancements in material science, fluid mechanics, surface engineering, and digital design, significant progress has been achieved in the research and application of dynamic sealing. Innovations such as the development of high-performance sealing materials, microstructured surface treatments, and the integration of intelligent monitoring and fault prediction systems have provided a robust foundation for enhancing the reliability and efficiency of sealing technologies. However, current methodologies face inherent limitations when confronted with extreme operating conditions—such as ultra-high temperatures, high pressures, and highly corrosive environments—and emerging demands in areas such as green energy, aerospace, and deep-sea exploration. Future research should prioritize the following areas:

- Development of novel materials: Designing advanced sealing materials with superior thermal resistance, corrosion resistance, and self-lubricating properties to address complex and variable operational demands.

- Structural design and optimization: Leveraging multiphysics coupling simulations and optimization algorithms to achieve precision in seal structure design, thereby enhancing sealing performance and reliability.

- Digitalization and intelligent management: Integrating sensor technology, intelligent diagnostic systems, and big data analytics to establish real-time monitoring and fault prediction systems, enabling intelligent management and precise control of sealing performance.

- Sustainability and green development: Focusing on the development of environmentally friendly sealing materials to minimize the environmental impact of sealing systems, promoting green manufacturing and circular economy practices.

The reclassification of seal types based on blocking medium forms offers a novel perspective for the design and optimization of sealing systems. The newly proposed self-impact sealing structure, through the introduction of impact-medium blocking mechanisms, achieves zero wear, simplified structures, and high stability, making it particularly suitable for non-contact sealing in high-speed and large-clearance applications. This innovation provides a groundbreaking approach to the efficient design of future sealing systems. By integrating self-impact sealing with advanced functional materials, its corrosion resistance, thermal stability, and wear resistance can be further enhanced to meet the stringent demands of modern industrial sealing applications. In-depth investigations into the fluid flow mechanisms within self-impact seals are expected to be pivotal for improving sealing performance. Self-impact sealing holds significant promise for leading future advancements in sealing technology, contributing to the safety, reliability, and efficiency of high-end equipment across diverse industries. This innovative self-impact sealing design is especially suitable for aerospace engines and chemical reactors, where traditional seals face significant limitations due to high rotational speeds and complex operational demands.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W. (Yan Wang); methodology, Y.W. (Yan Wang) and S.N.; literature review and analysis, Y.W. (Yan Wang), S.N. and C.F.; data curation, J.Z., T.L. and Y.W. (Yutong Wang); writing—original draft, Y.W. (Yan Wang) and S.N.; writing—review and editing, Y.W. (Yan Wang), S.N. and D.S.; visualization, J.Z. and T.L.; supervision, D.L.; formal analysis, S.N. and C.F.; Software, P.C. and Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52275192), the Basic Research Project of Lianyungang City (Grant No. JCYJ2301), the “Cyan and Blue Project” for universities in Jiangsu Province, the Sixth “521” Project of Lianyungang City (Grant No. LYG06521202262), the Jiangsu Province Graduate Research and Practice Innovation Program (Grant No. KYCX23-3453), and the Jiangsu Province College Students Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (Grant No. SZ202411641635003; Grant No. SY202411641635014).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| be | Tooth top width of screw seal [mm] | h1 | Cavity depth of labyrinth seal [mm] |

| bg | Groove width of screw seal [mm] | w1 | Cavity width of labyrinth seal [mm] |

| β | Helix angle [°] | w2 | Blade space width of labyrinth seal [mm] |

| L | Sealing medium seal axial width [mm] | t | Blade thickness of labyrinth seal [mm] |

| Ds | Outer diameter of screw seal [mm] | Φ | Diagram of holes of labyrinth seal [mm] |

| D | Sealing shaft diameter [mm] | α | Diverting angle [°] |

| h | Seal spacing [μm] | l | Flow distance [mm] |

| R | Suspension radius [mm] |

References

- Wei, L. (Ed.) Sealing Technology; Chemical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y. Practical Technology of Mechanical Seals; Machinery Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.J. Theory and Application of Leakage Prediction for Mechanical Seals; China Electric Power Press: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, R.; Gu, C.; Kang, Y.; Ge, X. Experimental study on adhesive and sealing performance of fire protection spray materials. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2024, 9, 455–463. [Google Scholar]

- Sarawate, N.; Wolfe, C.; Sezer, I.; Ziegler, R.; Chupp, R. Characterization of metallic W-Seals for inner to outer shroud sealing in industrial gas turbines. In Turbo Expo: Power for Land, Sea, and Air; ASME TurboExpo Proceedings; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.G.; Tian, R.G.; Zhang, Z.D.; Li, L.; Zhao, C.L.; Yu, H. Application of leak-free seals in alkaline pumps. Pet. Chem. Equip. 2020, 23, 84–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, H. Effects of fluid inertia forces on the static characteristics of high-speed thrust bearings in turbulent flow regimes. J. Tribol.—Trans. ASME 1989, 111, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, H.; Kamiyama, S. Effects of fluid inertia forces on non-contact mechanical seals. Trans. Jpn. Soc. Mech. Eng. 1996, 62, 4668–4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, C. Development of integrated testing and adjustment tools for eccentric layered injection well sealing. Pet. Min. Mach. 2021, 50, 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, A.; Stachowiak, G. Solid lubricants for high-temperature mechanical seals. Wear 2019, 426–427, 160–170. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Z. Development of corrosion-resistant seals for high-pressure chemical environments. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 278, 121209. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P.; Zhou, Y. Nano-lubricants for ultra-high pressure sealing applications. Tribol. Int. 2018, 126, 269–278. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.; Johnson, K. High-temperature gas seals: Enhancing performance through aerodynamic design. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2021, 143, 071014. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Li, F. Advanced composite ceramic seals for harsh chemical environments. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 2209–2217. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Gupta, S. Self-lubricating seals for high-temperature and high-pressure systems. Tribol. Lett. 2017, 65, 121. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. Study on Mechanical Seal Failure Analysis and Monitoring Systems for Reactors. Doctoral Dissertation, Beijing University of Chemical Technology, Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.T. Application and leakage management of mechanical seals in the chemical industry. Chem. Eng. Equip. 2018, 3, 185–186. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Y.; Huang, W.F.; Liu, X.F. Technological foundations and development trends in intelligent mechanical seals. J. Mech. Eng. 2021, 57, 116–128. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.P.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, Y.S. Study on diamond coating temperature measurement methods for mechanical seals. Lubr. Seal. 1996, 3, 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Will, T.P. Experimental observations of a face-contact mechanical shaft seal operating on water. Lubr. Eng. 1982, 38, 767–771. [Google Scholar]

- Doane, J.C.; Myrum, T.A.; Beard, J.E. An experimental-computational investigation of heat transfer in mechanical face seals. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1991, 34, 1027–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.Y. Information Acquisition and Application of Diamond Coatings in Mechanical Seals. Doctoral Dissertation, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Reungoat, D.; Frene, J. Temperature measurements by infrared thermography at the interface of a radial face seal. J. Tribol. 1991, 113, 571–576. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.D.; Xiong, Y.F. Application of infrared thermometry in gas film seal testing. In Proceedings of the Academic Symposium on Power Transmission of the Chinese Society of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Datong, China, 1 October 2001; pp. 223–227. [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen, J.; Siekkinen, V. Acoustic emission in monitoring sliding contact behavior. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 1995, 22 (Suppl. S1), 897–900. [Google Scholar]

- Holenstein, A.P. Diagnosis of mechanical seals in large pumps. Seal. Technol. 1996, 1996, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.E.; Gu, F.; Ball, A. A review of the condition monitoring of mechanical seals. In Proceedings of the 7th Biennial Conference on Engineering Systems Design and Analysis, Manchester, UK, 19–22 July 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Board, C.B. Stress wave analysis of turbine engine faults. In Aerospace Conference Proceedings; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Mba, D.; Cooke, A.; Roby, D. Detection of shaft-seal rubbing in large-scale power generation turbines with acoustic emissions: Case study. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part A J. Power Energy 2004, 218, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towsyfyan, H. A review of mechanical seals tribology and condition monitoring. In Proceedings of the Computing and Engineering Annual Researchers’ Conference, Huddersfield, UK, 1–4 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Towsyfyan, H.; Gu, F.; Ball, A.D. Modelling acoustic emissions generated by the tribological behavior of mechanical seals for condition monitoring and fault detection. Tribol. Int. 2018, 125, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, Z.; Xiaohui, L. Acoustic emission monitoring for film thickness of mechanical seals based on feature dimension reduction and cascaded decision. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Measuring Technology & Mechatronics Automation, Zhangjiajie, China, 10–11 January 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Theoretical and Experimental Research on Dynamic Performance of High-Speed Spiral Groove Dry Gas Seals. Doctoral Dissertation, Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferle, D.; Dullenkopf, K.; Bauer, H.J. Design and validation of a new test rig for brush seal testing under engine-relevant conditions. In Proceedings of the ASME 2011 Turbo Expo: Turbine Technical Conference and Exposition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 6–10 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Demiroglu, M.; Tichy, J.A. An investigation of heat generation characteristics of brush seals. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2007: Power for Land, Sea, and Air, Montreal, QC, Canada, 14–17 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Flouros, M.; Stadlbauer, M.; Cottier, F.; Proestler, S.; Beichl, S. Transient temperature measurements in the contact zone between brush seals using a pyrometric technique. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2012: Turbine Technical Conference and Exposition, Copenhagen, Denmark, 11–15 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero, E.J. Experimental results from a sensor brush seal. In Proceedings of the 46th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit, Nashville, TN, USA, 25–28 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero, E.J. Exploratory work in fiber optic brush seals for turbomachinery health prognostics. In Proceedings of the ASME 2009 Conference on Smart Materials, Adaptive Structures and Intelligent Systems, Oxnard, CA, USA, 21–23 September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tarudanafuski, K. Non-Contact Sealing; Machinery Industry Press: Beijing, China, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lebeck, A.O. Principles and Design of Mechanical Seals; Machinery Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.S.; Green, I. Physical modeling and data analysis of the dynamic response of a flexibly mounted rotor-mechanical seal. J. Tribol. 1995, 117, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M.; Ni, J. A study on composite material seals in high-pressure fluid environments. J. Tribol. 2018, 140, 051701. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, H.; Liu, X. Optimization of sealing coatings for automotive door seals: A study on material performance and environmental impact. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2019, 271, 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.; Harris, P. Development of integrated diagnostic tools for sealing systems in oil wells. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 187, 106819. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Park, J. Non-contact seals for liquid rocket engine turbopumps: Design and application. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2017, 66, 217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, C.; Müser, M.H.; Carbone, G.; Menga, N. Significance of elastic coupling for stresses and leakage in frictional contacts. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 131, 156201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aderikha, V.N.; Shapovalov, V.A. Mechanical and tribological behavior of PTFE-polyoxadiazole fiber composites: Effect of filler treatment. Wear 2011, 271, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.H.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Liu, W.M. Tribological behavior of hybrid glass/PTFE fabric composites with phenolic resin binder and nano-TiO2 filler. Wear 2008, 264, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burris, D.L.; Zhao, S.; Duncan, R.; Lowitz, J.; Perry, S.S.; Schadler, L.S.; Sawyer, W.G. A route to wear-resistant PTFE via trace loadings of functionalized nanofillers. Wear 2009, 267, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.N.; Yang, Y.L.; Chen, J.J.; Yu, X.J. Influence of serpentine content on the tribological behavior of PTFE/serpentine composite under dry sliding conditions. Wear 2010, 268, 996–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.Y.; Zhuang, G.S.; Sui, G.X.; Yang, R. Tribological behavior of PEEK/PTFE composites reinforced with potassium titanate whiskers. Wear 2010, 268, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, C.G. Laminated Finger Seal. U.S. Patent No. 5071138, 13 October 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y. Dynamic Fluid Sealing; Sinopec Press: Beijing, China, 1990; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Xu, H.J.; Chen, W. Critical choked characteristics of supercritical CO2 spiral groove dry gas seals. CIESC J. 2024, 75, 604–615. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, S.X.; Song, Y.S.; Yang, J. Elastic deformation of liquid spiral groove face seals operating at high speeds and low pressure. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 226, 107397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dong, G.H.; Yin, G.F. Vibration analysis and structural optimization of non-contact seals. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Eng. Sci.) 2018, 52, 1390–1397. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Sun, J.J. Self-cleaning analysis of self-pumping hydrodynamic and hydrostatic mechanical seals. Tribology 2019, 39, 259–268. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.F.; Jia, Q.; Zheng, Y.B. Influence of gas-liquid phases on ultrasonic testing accuracy for mechanical seal lubrication films. Lubr. Eng. 2022, 47, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.C.; Qian, C.F.; Li, S.X. Study of sealing mechanisms in gas-liquid backflow pumping seals. Tribol. Int. 2020, 142, 105974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.D.; Zhao, H.; Wang, P. Numerical and experimental analysis of oil-air two-phase leakage characteristics in bearing cavity seals. J. Mech. Eng. 2024, 60, 214–225. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.X.; Yang, S.; Tan, J. Pressure resistance of magnetic fluid seals with asymmetric polar teeth. J. Beijing Univ. Chem. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 50, 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.J.; Li, D.C.; He, X.Z. Effect of rotational speed on the failure-pressure of magnetic fluid seals. Chin. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. 2016, 36, 945–949. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Yu, S.R.; Ding, X.X. Performance analysis of floating foil gas seals based on bump foil deformation. CIESC J. 2022, 73, 2083–2093. [Google Scholar]

- Zhi, D.; Li, S.X.; Zhang, Q.X. Performance analysis of gas centrifugal seals with continuous fluid injection. Lubr. Eng. 2012, 37, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.P.; Ding, X.X.; Ding, J.H. Influence of elliptical micro-texture parameters on floating ring gas seals. Surf. Technol. 2023, 52, 146–159. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.K.; Peng, X.D.; Wang, L.Q. Axisymmetric dynamic model and seal behavior analysis of mechanical seals during startup and shutdown. CIESC J. 2011, 62, 1620–1625. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, X.F.; Xu, H. Design and performance analysis of a new non-contact self-impact seal. J. Mech. Eng. 2023, 59, 204–215. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; He, Y.M.; Xie, X.F. Design and Simulation of a New Near Zero-Wear Non-Contact Self-Impact Seal Based on the Tesla Valve Structure. Lubricants 2023, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, Z.X.; He, Y.M. Initial research on leakage characteristics and sealing mechanism of a new self-impact seal. Tribology 2023, 43, 1330–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, Y.M.; Li, M. A Self-Impact Magnetic Liquid Sealing Structure. China Patent 202410578708.9, 23 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, X.F.; He, Y.M. A new non-contact fluid seal technology based on the Tesla valve. Tribology 2023, 43, 975–985. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).