Abstract

Background: MiRNAs have emerged as minimally invasive biomarkers with considerable potential for the early detection of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). Although numerous studies have evaluated circulating miRNAs across different biofluids, the comparative diagnostic performance of saliva-, serum-, and plasma-derived miRNAs has not been systematically clarified. Methods: A meta-analysis was performed by screening PubMed, MEDLINE, Scopus, CINAHL, and related databases. Nineteen eligible studies evaluating miRNA-based assays in saliva, serum, or plasma were included. A random-effects bivariate model was used to calculate pooled sensitivity, specificity, and area under the HSROC curve. Meta-regression using log diagnostic odds ratio (lnDOR) examined whether biofluid type significantly influenced diagnostic performance. Results: Salivary miRNAs showed a pooled sensitivity of 0.76 (95% CI: 0.68–0.82; I2 = 84.69%), specificity of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.70–0.85; I2 = 70.41%), and an AUC of 0.84 (95% CI: 0.80–0.87). Plasma miRNAs produced comparable results with a pooled sensitivity of 0.77 (95% CI: 0.61–0.88; I2 = 90.45%), specificity of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.63–0.89; I2 = 80.20%), and an AUC of 0.85 (95% CI: 0.81–0.89). Serum-derived miRNAs demonstrated the highest accuracy with a pooled sensitivity of 0.82 (95% CI: 0.70–0.90; I2 = 76.92%), specificity of 0.88 (95% CI: 0.75–0.95; I2 = 74.87%), and an AUC of 0.91 (95% CI: 0.89–0.94). Despite serum’s numerically superior performance, meta-regression revealed no significant matrix effect (Wald χ2 = 0.20, p = 0.903). Conclusions: Although serum-derived miRNAs performed best overall, biofluid type was not a statistically significant determinant of diagnostic performance.

1. Introduction

Oral cancer ranks as the sixteenth most common malignancy worldwide, with incidence and mortality strongly influenced by regional habits, ethnic predispositions, and environmental exposures [1]. In 2018, cancers of the lip and oral cavity accounted for 354,864 new cases and 177,384 deaths globally, and the overall five-year survival rate of newly diagnosed patients remains approximately 50%, reflecting the persistent global disease burden [1,2]. Among these malignancies, oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) comprises nearly 90% of all cancers arising in the oral cavity, making it the dominant histological subtype of oral cancer [3].

The current diagnostic gold standard for OSCC is histopathological evaluation of tissue biopsy [4]. While highly accurate, biopsy-based diagnosis is inherently invasive, dependent on trained clinicians and experienced pathologists, and is limited by its inability to capture tumor heterogeneity, as an incisional biopsy represents only a small portion of a potentially heterogeneous lesion [4]. These limitations have strengthened the impetus to develop non-invasive molecular biomarkers that are useful for screening and early detection of the disease [5]. Nevertheless, no individual biomarker has yet been sufficiently validated for routine use in early OSCC detection or risk stratification, underscoring a significant unmet need in oral oncology [6].

Among the promising molecular candidates, miRNAs have emerged as highly relevant diagnostic biomarkers. MiRNAs are small non-coding RNAs of approximately 19–25 nucleotides that regulate gene expression at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels through interactions with the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of target mRNAs [7,8]. Dysregulated miRNA expression plays a pivotal role in tumor initiation, progression, invasion, and metastasis, acting either as oncogenes or tumor suppressors depending on the cellular context [9,10,11]. Furthermore, miRNAs exhibit tissue- and tumor-specific expression patterns, making them highly informative molecular signatures [12].

A major advantage of miRNAs is their exceptional stability in biofluids. They are protected from RNase activity through encapsulation within extracellular vesicles or association with protein–lipid complexes, enabling robust detection in saliva, plasma, and serum [8]. Multiple studies have confirmed the stability of circulating miRNAs even under challenging pre-analytical conditions [13,14,15,16,17]. Given these properties, miRNAs represent compelling candidates for liquid biopsy-based diagnostics, with different biofluids offering distinct biological and practical advantages. However, the results across studies remain inconsistent due to variations in detection platforms, normalization strategies, patient characteristics, and sample types. Importantly, the relative diagnostic performance across different biofluids remains unclear, and no consensus exists regarding which biofluid provides the highest accuracy for OSCC detection [18].

Given these uncertainties this meta-analysis aims to compare the diagnostic accuracy of salivary, plasma, and serum miRNA profiles to determine which biofluid provides the most reliable performance for OSCC detection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Protocol

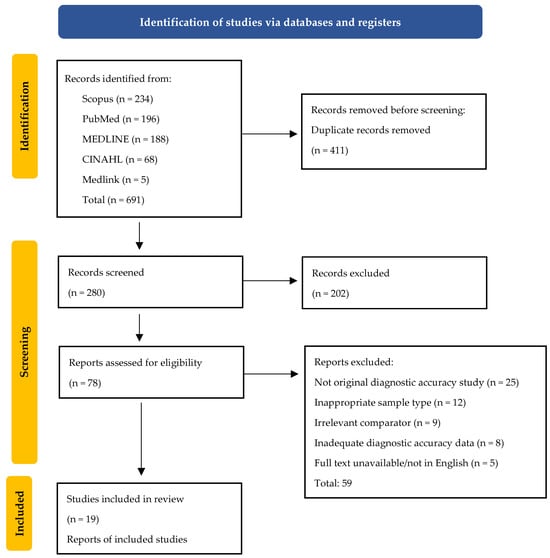

This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Figure 1). All methodological steps including search design, eligibility screening, data extraction, and statistical synthesis were defined a priori to ensure transparency and reproducibility. The review protocol was prospectively registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under registration number CRD420251245619. The PRISMA checklist and flow diagram used in this study are presented in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis) flow diagram of the study selection.

2.2. Search Strategy

A comprehensive systematic literature search was conducted by two independent reviewers (A.W. and N.S.) in the PubMed, MEDLINE, Scopus, CINAHL and Medlink databases to identify studies published between January 2015 and December 2025 that evaluated the diagnostic performance of microRNAs for detecting oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). The search strategy incorporated MeSH terms and free-text keywords:

(“oral squamous cell carcinoma” OR OSCC OR “oral cancer”) AND (saliva OR salivary OR plasma OR serum) AND (microRNA OR miRNA OR “miR-21” OR “miR-31” OR “miR-184” OR “miR-200” OR “microRNAs”) AND (diagnos* OR sensitivity OR specificity OR ROC OR AUC OR “receiver operating”).

All records were imported into Rayyan “https://www.rayyan.ai/’ (accessed on 1 October 2025) for automated duplicate removal and blinded screening. Study selection proceeded through three predefined stages: database searching, title and abstract screening, and full-text evaluation according to the PICOS eligibility framework. Disagreements between reviewers (A.W. and N.S.) were resolved through discussion, and unresolved cases were adjudicated by a third reviewer (V.J.). The complete search process, including the number of studies identified, screened, excluded, and included, is illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria (PICOS Framework)

Study eligibility was defined according to the PICOS framework (Table 1). The Population consisted of patients with histopathologically confirmed oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). The Intervention (Index Test) included the detection and quantification of microRNAs (miRNA/microRNA) in non-invasive biofluids, specifically saliva, plasma, or serum, using validated molecular platforms such as RT-qPCR, microarray, or next-generation sequencing. The Comparison group comprised healthy controls without any clinical evidence of disease. Eligible studies were required to report diagnostic accuracy outcomes, including sensitivity, specificity, area under curve (AUC), positive and negative predictive values (PPV, NPV), and sufficient data to derive true positives (TP), false positives (FP), true negatives (TN), and false negatives (FN). The Study design was restricted to observational diagnostic accuracy studies, including case–control and cohort designs. Studies were excluded if they did not assess diagnostic accuracy, involved inappropriate or non-specified biofluids, lacked extractable 2 × 2 contingency data, were non-original publications (such as reviews, letters, or editorials), were not available in English, or did not include a healthy control group.

Table 1.

PICOS (Population, Index test, Comparison, Outcomes, and Study design) criteria used for study selection.

2.4. Data Extraction

Two investigators (A.W. and N.S.) independently screened all eligible references by title and abstract, followed by full-text evaluation to extract relevant data according to a predefined protocol. The extracted information included: (1) study characteristics, encompassing study ID, year of publication, and country; (2) sample details, including total sample size and the type of biofluid analyzed (saliva, plasma, or serum); (3) miRNA-related features, such as the specific miRNAs evaluated, expression direction (upregulated or downregulated), whether the biomarkers were assessed individually or as part of a multi-miRNA panel, and the molecular detection platform used (RT-qPCR, microarray, or next-generation sequencing); and (4) diagnostic accuracy data, comprising true positives (TP), false positives (FP), true negatives (TN), false negatives (FN), sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and area under the ROC curve (AUC). All extracted data were cross-verified by both reviewers to ensure completeness and accuracy.

2.5. Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of each included study was independently evaluated by two examiners (A.W. and N.S.) using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 (QUADAS-2) tool. This instrument assesses four key domains: patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing to determine the risk of bias and, for the first three domains, concerns regarding applicability. Each domain was rated as low, high, or unclear risk based on predefined signaling questions, and a study was considered at high risk of bias if any signaling question within that domain indicated a potential methodological limitation. All assessments were conducted in duplicate, and any discrepancies or uncertainties were resolved through discussion. When consensus could not be reached, a third reviewer (V.J.) provided adjudication to ensure methodological rigor and consistency.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 19.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Pooled sensitivity, specificity, and AUC values were calculated using a random-effects bivariate model, with HSROC curves generated for overall and biofluid-specific (saliva, serum, plasma) analyses. Between-study heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic, and potential contributors to heterogeneity were explored through meta-regression based on lnDOR. Funnel plots were used to assess possible publication bias across all studies and within subgroups.

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

A total of 19 studies were included in this meta-analysis, comprising 1872 patients with OSCC and 783 healthy controls. The studies were conducted across multiple geographic regions, predominantly in Asia (China, Japan, Korea, India, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Taiwan; n = 13), followed by Europe (Hungary, Bulgaria, and Italy; n = 3), Australia (n = 2), and Africa/Middle East (Egypt; n = 1). The included studies evaluated a wide range of salivary, plasma, and serum microRNAs using RT-qPCR, microarray, or NGS platforms, assessing both single-miRNA markers and multi-miRNA panels. Detailed study characteristics including publication year, country, sample size, biofluid type, and miRNA features are presented in Table 2. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of OSCC patients and control groups across the included studies are summarized in Table 3, while comprehensive diagnostic accuracy data (TP, FP, TN, FN, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and AUC) for each study are summarized in Table 4.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies.

Table 3.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of OSCC patients and control groups in the included studies.

Table 4.

Summary of diagnostic performance metrics of the included studies.

3.2. Data Analysis

We compared three diagnostic subsets based on biofluid type: saliva, serum, and plasma, and additionally performed a combined analysis integrating all miRNA matrices. A random-effects model was applied to pool sensitivity, specificity, and AUC estimates across all studies and within each biofluid-specific subgroup. Forest plots and HSROC curves were generated to illustrate overall diagnostic performance.

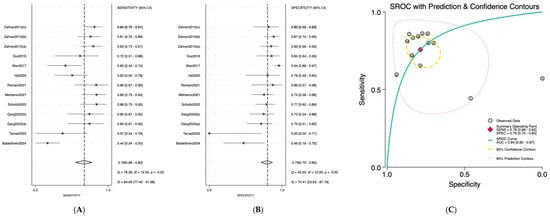

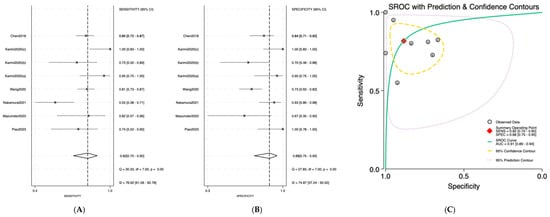

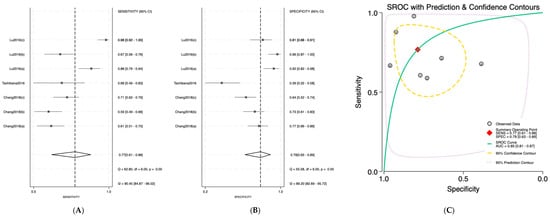

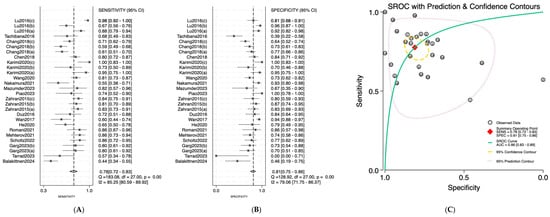

Salivary miRNAs demonstrated a pooled sensitivity of 0.76 (95% CI: 0.68–0.82; I2 = 84.69%), specificity of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.70–0.85; I2 = 70.41%), and an AUC of 0.84 (95% CI: 0.80–0.87) (Figure 2). Serum-derived miRNAs showed higher diagnostic accuracy, with a pooled sensitivity of 0.82 (95% CI: 0.70–0.90; I2 = 76.92%), specificity of 0.88 (95% CI: 0.75–0.95; I2 = 74.87%), and an AUC of 0.91 (95% CI: 0.89–0.94) (Figure 3). Plasma-based miRNAs yielded a pooled sensitivity of 0.77 (95% CI: 0.61–0.88; I2 = 90.45%), specificity of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.63–0.89; I2 = 89.20%), and an AUC of 0.85 (95% CI: 0.81–0.89) (Figure 4). When all three biofluids were combined, the overall pooled sensitivity was 0.78 (95% CI: 0.72–0.83; I2 = 85.25%), specificity was 0.81 (95% CI: 0.75–0.86; I2 = 79.06%), and the overall AUC was 0.86 (95% CI: 0.83–0.89) (Figure 5).

Figure 2.

Diagnostic performance of salivary microRNAs for detecting OSCC. (A) Forest plot of pooled sensitivity of salivary microRNAs among 19 studies; (B) Forest plot of pooled sensitivity of salivary microRNAs; (C) SROC Curve with pooled estimates of sensitivity, specificity, and AUC of salivary microRNAs in OSCC. Abbreviations: AUC, area under the SROC curve; miRNA, microRNAs; OSCC, oral squamous cell carcinoma; SROC, summary receiver operator characteristic [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28].

Figure 3.

Diagnostic performance of serum microRNAs for detecting OSCC; (A) Forest plot of pooled sensitivity of serum microRNAs among 19 studies; (B) Forest plot of pooled sensitivity of serum microRNAs; (C) SROC Curve with pooled estimates of sensitivity, specificity, and AUC of serum microRNAs in OSCC. Abbreviations: AUC, area under the SROC curve; miRNA, microRNAs; OSCC, oral squamous cell carcinoma; SROC, summary receiver operator characteristic [29,30,31,32,33,34].

Figure 4.

Diagnostic performance of plasma microRNAs for detecting OSCC. (A) Forest plot of pooled sensitivity of plasma microRNAs among 19 studies; (B) Forest plot of pooled sensitivity of plasma microRNAs; (C) SROC Curve with pooled estimates of sensitivity, specificity, and AUC of plasma microRNAs in OSCC. Abbreviations: AUC, area under the SROC curve; miRNA, microRNAs; OSCC, oral squamous cell carcinoma; SROC, summary receiver operator characteristic [35,36,37].

Figure 5.

Diagnostic performance of combined sample (saliva, serum, and plasma) microRNAs for detecting OSCC. (A) Forest plot of pooled sensitivity of combined sample (saliva, serum, and plasma) microRNAs among 19 studies; (B) Forest plot of pooled sensitivity of combined sample (saliva, serum, and plasma) microRNAs; (C) SROC Curve with pooled estimates of sensitivity, specificity, and AUC of combined sample (saliva, serum, and plasma) microRNAs in OSCC. Abbreviations: AUC, area under the SROC curve; miRNA, microRNAs; OSCC, oral squamous cell carcinoma; SROC, summary receiver operator characteristic [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

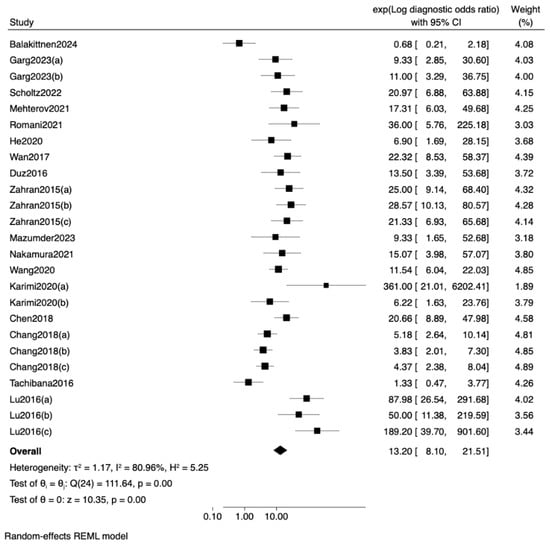

To further examine the influence of sample type on diagnostic accuracy, a meta-regression analysis using log diagnostic odds ratio (lnDOR) as the effect size was conducted (Table 5). The model showed no statistically significant differences across matrices (Wald χ2 = 0.20, p = 0.9038). Compared with saliva (reference), neither serum (exp[b] = 1.38, p = 0.653) nor plasma (exp[b] = 1.13, p = 0.836) produced a meaningful change in DOR (Figure 6). Collectively, these findings indicate that the choice of biofluid does not materially modify the diagnostic performance of miRNA-based assays for OSCC.

Table 5.

Comparison of diagnostic performance across saliva, serum, and plasma matrices using meta-regression of log diagnostic odds ratios (lnDOR).

Figure 6.

Forest plot and random-effects meta-regression of diagnostic odds ratios (DOR) for miRNA-based detection of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) across different sample [19,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

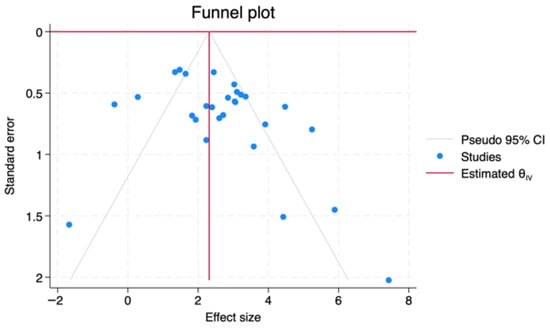

Funnel plots were constructed by plotting the log diagnostic odds ratio (lnDOR) for each study against its standard error, allowing visual detection of small-study effects or publication bias (Figure 7). The saliva subgroup showed a relatively symmetric distribution, with studies clustering around the pooled lnDOR and narrowing at higher precision levels. Serum studies displayed wider scatter, particularly among lower-precision datasets, but without directional skew. Plasma studies, being fewer in number, produced a less distinct funnel shape, limiting interpretability due to small-study variance. The combined dataset demonstrated the most stable funnel structure, indicating no strong evidence of publication bias. Overall, visual inspection across all subgroups did not identify systematic asymmetry, supporting the assumption of unbiased reporting.

Figure 7.

Funnel plots assessing potential publication bias for lnDOR across biofluid types.

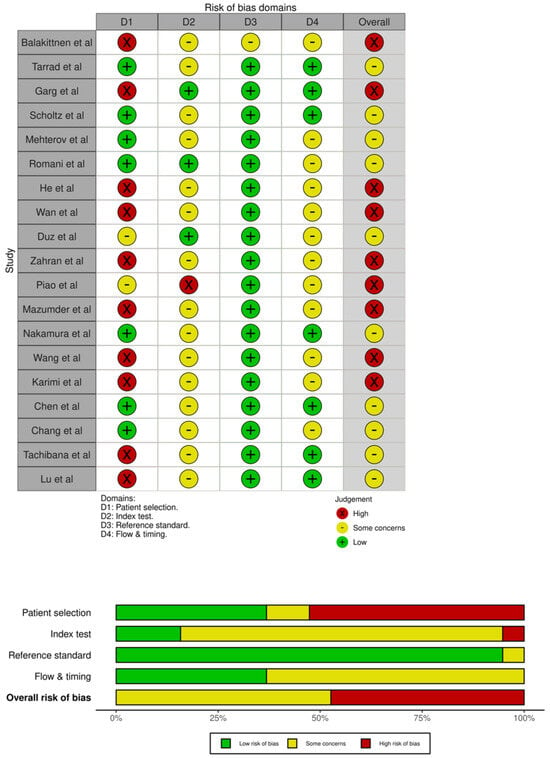

3.3. Result of Quality Assessment

The QUADAS-2 evaluation is summarized in Figure 8 Most studies demonstrated low risk of bias in the index test, reference standard, and flow/timing domains. However, patient selection frequently showed high or unclear risk, largely due to case–control designs and non-random sampling approaches. Applicability concerns were generally low across all domains. Overall, the methodological quality of the included studies was acceptable, with no critical limitations likely to substantially affect the pooled diagnostic estimates.

Figure 8.

QUADAS−2 quality assessment of the 19 included articles. Abbreviations: QUADAS-2, Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

4. Discussion

In 2020, an estimated 377,713 new OSCC cases were reported worldwide [38]. Projections from the Global Cancer Observatory indicate that the incidence of OSCC will increase by nearly 40% by 2040, accompanied by a corresponding rise in mortality [39]. While early-stage OSCC (stages I and II) shows favorable five-year survival rates exceeding 80%, prognosis declines sharply to around 60% in advanced stages (III and IV) [31]. This disparity highlights the critical importance of early diagnosis. MiRNAs are now widely investigated as noninvasive diagnostic biomarkers for early diagnosis of OSCC [40,41].

In this meta-analysis, 19 studies evaluating miRNA-based diagnostic assays for OSCC were included across three biofluids: saliva, serum, and plasma. Collectively, a total of 54 unique miRNAs were identified. Of these, 38 were reported as upregulated in OSCC, 12 were downregulated, and four exhibited mixed or inconsistent expression patterns across studies. Among all investigated biomarkers, miR-21 emerged as the most frequently studied miRNA, appearing in three independent studies (Garg et al. [21], Zahran et al. [28], and Karimi et al. [33]). This finding highlights the biological relevance of miR-21, a well-known oncogenic microRNA (“oncomiR”) that promotes tumor proliferation, invasion, and metastasis through the suppression of multiple tumor-suppressor pathways especially in oral cancer [42]. The importance of miR-21 as a circulating biomarker has also been emphasized in a meta-analysis by Peng et al. that identified miR-21 as one of the most representative and extensively validated miRNAs across various cancer types, including colorectal cancer [43].

Building upon this biomarker profile, we next evaluated the pooled diagnostic performance across saliva, serum, and plasma. The pooled diagnostic estimates demonstrated notable variation among biofluid types. Salivary miRNAs yielded a pooled sensitivity of 0.76, specificity of 0.79, and an AUC of 0.84, indicating moderate diagnostic accuracy. Serum-derived microRNAs showed the highest performance, with a pooled sensitivity of 0.82, specificity of 0.88, and an AUC of 0.91, surpassing both saliva and plasma. Plasma microRNAs exhibited a pooled sensitivity of 0.77, specificity of 0.79, and an AUC of 0.85, comparable to saliva but still inferior to serum. When all matrices were combined, the overall pooled values were a sensitivity of 0.78, specificity of 0.81, and an AUC of 0.86. Among the three biofluids, serum consistently demonstrated superior diagnostic accuracy, achieving the highest sensitivity, specificity, and AUC, exceeding even the combined analysis of all biofluid types.

The superior diagnostic performance observed for serum-derived miRNAs in this meta-analysis likely reflects both biological and pre-analytical effects related to coagulation process [44,45,46,47]. Regarding the effects of the coagulation process, studies comparing serum and plasma collected simultaneously from the same individuals have consistently demonstrated higher total RNA and miRNA concentrations in serum, suggesting the release of additional miRNAs during coagulation [46]. Furthermore, a study reported significant differences in approximately one-third of measured miRNAs between serum and plasma, with higher miRNA levels observed in serum [47]. These differences were attributed to the serum preparation process, particularly clot formation, during which miRNA-containing blood cells may become incorporated into the clot and release additional miRNAs [47]. Differences in miRNA abundance have also been shown to correlate more closely with platelet and leukocyte-derived miRNA spectra, supporting the concept of regulated RNA/miRNA trafficking from cellular compartments into the extracellular environment [45]. During coagulation, blood cells are subjected to a stress-inducing environment that can actively promote the release of specific miRNAs and other RNA species, a process that has also been observed in vitro under serum-free conditions [44].

Despite these biological and technical differences favoring serum, the findings of our meta-regression provide an important complementary perspective. Although pooled estimates showed that serum-derived miRNAs achieved the highest sensitivity, specificity, and AUC among the three matrices, the meta-regression demonstrated that the diagnostic performance of miRNA-based assays was not significantly influenced by the type of biofluid (saliva, serum, or plasma). The higher diagnostic odds ratio observed for serum was numerically superior but did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.65). This indicates that, once between-study variability and within-study assay structure are accounted for, the biological source of circulating miRNAs may be sufficiently consistent across oral and systemic biofluids. Accordingly, these results support the methodological flexibility of liquid biopsy approaches in OSCC, suggesting that clinically meaningful detection of tumor-associated miRNAs can be achieved across multiple biofluid types, even if serum tends to exhibit incremental empirical advantages in raw diagnostic metrics.

Our meta-analysis offers an important advantage over previous reviews, as no earlier study has directly compared diagnostic performance across all three major biofluid matrices: saliva, serum, and plasma within the same analytic framework. However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, meta-regression was limited to biofluid type due to insufficient and heterogenous reporting of important covariates such as age, smoking and alcohol consumption, tumor stage, and miRNAs analytical methods across studies. As a result, residual confounding may exist, and the absence of a statistically significant matrix effect should be interpreted with caution, as the true influence of biofluid type may be underestimated. In addition, several included studies evaluated single-miRNA biomarkers, some of which are dysregulated across a broad range of non-malignant diseases, raising concerns regarding disease specificity. For example, miR-106a has been reported to be altered in inflammatory bowel disease, alzheimer’s disease, and multiple sclerosis, while miR-21 is a well-known inflammation and stress-responsive miRNA dysregulated in multiple cancers and non-malignant inflammatory conditions [48,49,50,51]. Consequently, diagnostic performance observed for single-miRNA markers may partly reflect non-specific inflammatory signals rather than OSCC-specific biology. In contrast, multi-miRNA panels may mitigate this limitation by capturing combinatorial expression patterns more representative of tumor-specific processes. Finally, these limitations point to key areas for improvement in future studies.

5. Conclusions

Among the three biofluids, serum-derived miRNAs showed the highest pooled performance, with superior sensitivity, specificity, and AUC. However, meta-regression indicated that biofluid type did not significantly influence overall diagnostic accuracy, suggesting that clinically relevant miRNA signatures can be reliably detected across different matrices.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jpm16010052/s1, Table S1: PRISMA checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.W., T.S., N.S. and V.J.; Methodology: A.W., N.S. and V.J.; Software: A.W. and T.F.; Validation: A.W., N.S. and V.J.; Formal analysis: B.B., A.R.S. and D.J.P.; Investigation: N.S., V.J. and D.J.P.; Resources: T.S., M.M. and Y.H.; Data curation: A.W. and T.F.; Writing—original draft preparation: A.W., N.S., V.J., B.B. and A.R.S.; Writing—review and editing: A.W., N.S., V.J., T.S., M.M. and Y.H.; Supervision: T.S., M.M. and Y.H.; Project administration: A.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OSCC | Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| NGS | Next Generation Sequencing |

| RT-qPCR | Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| TP | True positive |

| FP | False positive |

| FN | False negative |

| TN | True negative |

| PPV | Positive Predictive Value |

| NPV | Negative Predictive Value |

| lnDOR | log Diagnostic Odds Ratios |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| miR | miRNAs/microRNAs |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| QUADAS-2 | Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 |

| HSROC | Hierarchical Summary Receiver Operating Characteristic |

References

- Thavarool, S.B.; Muttath, G.; Nayanar, S.; Duraisamy, K.; Bhat, P.; Shringarpure, K.; Priyakanta, N.; Jaya, P.T.; Alfonso, T.; Sairu, P.; et al. Improved survival among oral cancer patients: Findings from a retrospective study at a tertiary care cancer centre in rural Kerala, India. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, P.; Dadhich, A.; Saluja, H.; Bawane, S.; Sachdeva, S. The prevalence of squamous cell carcinoma in different sites of oral cavity at our Rural Health Care Centre in Loni, Maharashtra–a retrospective 10-year study. Współczesna Onkol. 2017, 2, 178–183. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.F.; Chen, Y.J.; Tsai, F.T.; Li, W.C.; Hsu, M.L.; Wang, D.H.; Yang, C.C. Current insights into oral cancer diagnostics. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.; Kotimoole, C.N.; Ghoshal, S.; Bakshi, J.; Chatterjee, A.; Prasad, T.S.K.; Pal, A. Identification of potential salivary biomarker panels for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouaoud, J.; Bossi, P.; Elkabets, M.; Schmitz, S.; van Kempen, L.C.; Martinez, P.; Saintigny, P. Unmet Needs and Perspectives in Oral Cancer Prevention. Cancers 2022, 14, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakittnen, J.; Weeramange, C.E.; Wallace, D.F.; Duijf, P.H.G.; Cristino, A.S.; Kenny, L.; Punyadeera, C. Noncoding RNAs in oral cancer. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2023, 14, e1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Quintero, B. Extracellular micrornas as intercellular mediators and noninvasive biomarkers of cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Zhang, D.Y.; Zhang, J.Y.; Hayat, M.K.; Ren, J.; Nasir, S.; Bai, Q. The Key Role of microRNAs in Initiation and Progression of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 950374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekarek, L.; Torres-Carranza, D.; Fraile-Martinez, O.; García-Montero, C.; Pekarek, T.; Saez, M.A.; Ortega, M.A. An Overview of the Role of MicroRNAs on Carcinogenesis: A Focus on Cell Cycle, Angiogenesis and Metastasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashi, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Takaoka, R.; Tani, M.; Noma, Y.; Mori, K.; Sugiura, T. Identification of Neck Lymph Node Metastasis-Specific microRNA—Implication for Use in Monitoring or Prediction of Neck Lymph Node Metastasis. Cancers 2023, 15, 3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sempere, L.F.; Azmi, A.S.; Moore, A. microRNA-based diagnostic and therapeutic applications in cancer medicine. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2021, 12, e1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz-Rubio, D.; Martin-Burriel, I.; Gil, A.; Cubero, P.; Forner, M.; Khalyfa, A.; Marin, J.M. Stability of Circulating Exosomal miRNAs in Healthy Subjects article. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quirico, L.; Orso, F. The power of microRNAs as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in liquid biopsies. Cancer Drug Resist. 2020, 3, 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandau, U.S.; Wiedrick, J.T.; McFarland, T.J.; Galasko, D.R.; Fanning, Z.; Quinn, J.F.; Saugstad, J.A. Analysis of the longitudinal stability of human plasma miRNAs and implications for disease biomarkers. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, E.S.; Hue, J.J.; Loftus, A.W.; Ali, S.A.; Graor, H.J.; Rothermel, L.D.; Winter, J.M. Stability of microRNAs in serum and plasma reveal promise as a circulating biomarker. Noncoding RNA Res. 2025, 15, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupec, T.; Bleilevens, A.; Iborra, S.; Najjari, L.; Wittenborn, J.; Maurer, J.; Stickeler, E. Stability of circulating microRNAs in serum. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Xin, Z.; Guo, S.; Li, S.; Cheng, J.; Jiang, H. Blood and Salivary MicroRNAs for Diagnosis of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 79, e1082–1082.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakittnen, J.; Ekanayake Weeramange, C.; Wallace, D.F.; Duijf, P.H.G.; Cristino, A.S.; Hartel, G.; Punyadeera, C. A novel saliva-based miRNA profile to diagnose and predict oral cancer. Int. J. Oral. Sci. 2024, 16, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrad, N.A.F.; Hassan, S.; Shaker, O.G.; AbdelKawy, M. “Salivary LINC00657 and miRNA-106a as diagnostic biomarkers for oral squamous cell carcinoma, an observational diagnostic study”. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Urs, A.B.; Koner, B.C.; Augustine, J.; Guru, S.A. Evaluation of Diagnostic Significance of Salivary miRNA-184 and miRNA-21 in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders. Head. Neck Pathol. 2023, 17, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtz, B.; Horváth, J.; Tar, I.; Kiss, C.; Márton, I.J. Salivary miR-31-5p, miR-345-3p, and miR-424-3p Are Reliable Biomarkers in Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Pathogens 2022, 11, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehterov, N.; Sacconi, A.; Pulito, C.; Vladimirov, B.; Haralanov, G.; Pazardjikliev, D.; Sarafian, V. A novel panel of clinically relevant miRNAs signature accurately differentiates oral cancer from normal mucosa. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1072579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romani, C.; Salviato, E.; Paderno, A.; Zanotti, L.; Ravaggi, A.; Deganello, A.; Bignotti, E. Genome-wide study of salivary miRNAs identifies miR-423-5p as promising diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Theranostics 2021, 11, 2987–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Ping, F.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, C.; Deng, M.; Cheng, B.; Xia, J. Salivary exosomal miR-24-3p serves as a potential detective biomarker for oral squamous cell carcinoma screening. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 121, 109553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Y.; Vagenas, D.; Salazar, C.; Kenny, L.; Perry, C.; Calvopiña, D.; Punyadeera, C. Salivary miRNA panel to detect HPV-positive and HPV-negative head and neck cancer patients. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 99990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duz, M.B.; Karatas, O.F.; Guzel, E.; Turgut, N.F.; Yilmaz, M.; Creighton, C.J.; Ozen, M. Identification of miR-139-5p as a saliva biomarker for tongue squamous cell carcinoma: A pilot study. Cell. Oncol. 2016, 39, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahran, F.; Ghalwash, D.; Shaker, O.; Al-Johani, K.; Scully, C. Salivary microRNAs in oral cancer. Oral. Dis. 2015, 21, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, Y.; Jung, S.N.; Lim, M.A.; Oh, C.; Jin, Y.L.; Kim, H.J.; Koo, B.S. A circulating microRNA panel as a novel dynamic monitor for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, S.; Basu, B.; Ray, J.G.; Chatterjee, R. MiRNAs as non-invasive biomarkers in the serum of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC) and Oral Potentially Malignant Disorder (OPMD) patients. Arch Oral Biol 2023, 147, 105627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Hiyake, N.; Hamada, T.; Yokoyama, S.; Mori, K.; Yamashiro, K.; Sugiura, T. Circulating microRNA panel as a potential novel biomarker for oral squamous cell carcinoma diagnosis. Cancers 2021, 13, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Song, H.; Yang, S. MicroRNA-206 has a bright application prospect in the diagnosis of cases with oral cancer. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 8169–8173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, A.; Bahrami, N.; Sayedyahossein, A.; Derakhshan, S. Evaluation of circulating serum 3 types of microRNA as biomarkers of oral squamous cell carcinoma; A pilot study. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2020, 49, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Hu, J.; Pan, L.; Yin, X.; Wang, Q.; Chen, H. Diagnostic and prognostic value of serum miR-99a expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Biomark. 2018, 23, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.A.; Weng, S.L.; Yang, S.F.; Chou, C.H.; Huang, W.C.; Tu, S.J.; Huang, H.D. A three–MicroRNA signature as a potential biomarker for the early detection of oral cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachibana, H.; Sho, R.; Takeda, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yoshida, Y.; Narimatsu, H.; Iino, M. Circulating miR-223 in oral cancer: Its potential as a novel diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.C.; Chang, J.T.C.; Huang, Y.C.; Huang, C.C.; Chen, W.H.; Lee, L.Y.; Cheng, A.J. Combined determination of circulating miR-196a and miR-196b levels produces high sensitivity and specificity for early detection of oral cancer. Clin. Biochem. 2015, 48, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, M.; Li, B.; Huang, Z.; Qin, S.; Huang, C. Oral squamous cell carcinomas: State of the field and emerging directions. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2023, 15, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siravegna, G.; Marsoni, S.; Siena, S.; Bardelli, A. Integrating liquid biopsies into management of cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chang, S.; Li, G.; Sun, Y. Application of liquid biopsy in precision medicine: Opportunities and challanges. Front. Med. 2017, 11, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.; Hamsa, D.; Fareed, M.; Karobari, M.I. An update on the molecular mechanisms underlying the progression of miR-21 in oral cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 23, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Zhang, X.; Min, M.; Zou, L.; Shen, P.; Zhu, Y. The clinical role of microRNA-21 as a promising biomarker in the diagnosis and prognosis of colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 44893201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padroni, L.; De Marco, L.; Dansero, L.; Fiano, V.; Milani, L.; Vasapolli, P.; Sacerdote, C. An Epidemiological Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis on Biomarker Role of Circulating MicroRNAs in Breast Cancer Incidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Pozo, V.A.; Cadena-Ullauri, S.; Guevara-Ramírez, P.; Paz-Cruz, E.; Tamayo-Trujillo, R.; Zambrano, A.K. Differential microRNA expression for diagnosis and prognosis of papillary thyroid cancer. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1139362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motshwari, D.D.; George, C.; Matshazi, D.M.; Weale, C.J.; Davids, S.F.G.; Zemlin, A.E.; Matsha, T.E. Expression of whole blood miR-126-3p, -30a-5p, -1299, -182-5p and -30e-3p in chronic kidney disease in a South African community-based sample. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakabayashi, I.; Marumo, M.; Ekawa, K.; Daimon, T. Differences in serum and plasma levels of microRNAs and their time-course changes after blood collection. Pract. Lab. Med. 2024, 39, e00376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, Y.N.; Kamel, A.M.; Medhat, M.A.; Hetta, H.F. MicroRNA signatures in the pathogenesis and therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Exp. Med. 2024, 24, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.B.; Fu, Q.; Guo, M.; Du, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, Y. MicroRNAs: Pioneering regulators in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Transl. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor Eddin, A.; Hamsho, K.; Adi, G.; Al-Rimawi, M.; Alfuwais, M.; Abdul Rab, S.; Yaqinuddin, A. Cerebrospinal fluid microRNAs as potential biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1210191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.C.; O’Connell, R.M. MicroRNAs: At the Interface of Metabolic Pathways and Inflammatory Responses by Macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.