Abstract

Gene therapy represents a transformative frontier in ophthalmology, offering the potential to address inherited and acquired retinal diseases at their genetic origin rather than through symptomatic management. By introducing exogenous genetic material to restore or modulate gene expression, gene therapy aims to preserve or even restore vision in patients with mutations that disrupt normal retinal function. The eye’s small, compartmentalized structure, relative immune privilege, and direct accessibility through subretinal or intravitreal routes make it an ideal target for localized delivery with minimal systemic exposure. The approval of voretigene neparvovec-rzyl for RPE65-mediated retinal dystrophy marked a pivotal milestone, establishing proof of concept for durable and safe gene replacement therapy. Looking ahead, continued refinements in vector design, CRISPR-based editing strategies, and delivery platforms are expected to expand the therapeutic reach of gene therapy beyond monogenic disorders. With multiple early-phase clinical trials underway for inherited and acquired retinal diseases, the coming decade is poised to bring broader applicability, improved durability, and more accessible gene-based treatments across the spectrum of retinal pathology.

1. Introduction

1.1. Gene Therapy for Eye Disease

Gene therapy represents an innovative method for the treatment of inherited and acquired diseases by introducing exogenous genetic material to alter gene expression for clinical benefit. The primary objective of gene therapy is either to restore function of genes rendered inactivated by mutations, or to mitigate the effects of pathological gene variants [1]. In the context of ophthalmology, gene therapy holds immense potential, as replacing or correcting defective genes prior to significant retinal degeneration can preserve and, in some cases, restore vision [2].

The eye possesses several anatomical and physiological advantages that make it a well-suited target for gene therapy. Its small, compartmentalized structure allows for localized treatment, thereby minimizing systemic exposure and associated risks [2]. Furthermore, the eye’s relative immune privilege helps to reduce immune responses against viral vectors and transgenes, while the blood–retinal barrier limits their unintended systemic spread [3]. The ability to directly access the retina by means of intravitreal or subretinal injections further contributes to the precision and safety of ocular gene therapy [1]. However, recent evidence suggests that ocular immune privilege is not absolute, as some studies have reported inflammatory responses following retinal gene therapy [4].

Several gene therapy strategies have demonstrated clinical success, particularly using adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors, which have been instrumental in treating inherited retinal disorders (IRDs). The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of Luxturna (voretigene neparvovec-rzyl) in 2017 marked a significant milestone, providing a functional copy of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium-specific 65 kDa protein (RPE65) gene to patients with Leber congenital amaurosis type 2 (LCA-2) [5]. Clinical trials of voretigene neparvovec-rzyl demonstrated significant improvements in visual acuity and FST improvements (low light sensitivity) [6]. Despite this success, challenges remain, including the durability of gene therapy effects, vector immunogenicity, and the complexity of addressing diseases caused by multiple genetic mutations [7].

Beyond monogenic diseases, gene therapy is expanding to include polygenic and multifactorial ocular conditions such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD), diabetic retinopathy (DR), and glaucoma. Emerging approaches, such as gene silencing, gene editing, and modifier gene therapy, are being developed to target these complex disorders [8]. Optogenetics, an innovative technique that introduces light-sensitive proteins to retinal cells, is being investigated as a potential therapy for advanced retinal degeneration where traditional gene replacement strategies may no longer be effective [9].

Although the eye is often described as immune-privileged, this protection is incomplete, and viral vectors still interact with local immune pathways. Subretinal delivery exposes vectors to microglia and retinal antigen-presenting cells, while intravitreal injection encounters neutralizing antibodies and complement in the vitreous. These responses can reduce transgene expression, trigger inflammation, such as in gene-therapy–associated uveitis, and limit the feasibility of redosing due to capsid-specific antibody formation. Understanding this balance between immune privilege and vector immunogenicity is essential for ensuring long-term safety and durability of ocular gene therapies.

1.2. Personalized Medicine

Personalized medicine, also referred to as precision medicine, represents a novel approach to healthcare that tailors treatments to an individual’s unique genetic, environmental, and lifestyle characteristics. By integrating these variables, precision medicine enables more accurate disease prediction, optimized treatment strategies, and tailored medication regimens. The Precision Medicine Initiative, a national effort launched in the United States, has emphasized the importance of integrating individualized genetic information into clinical practice to improve patient outcomes [10]. Advancements in pharmacokinetics, tissue-specific biomarker discovery, and molecularly targeted therapies have reshaped treatment strategies across various medical fields, including oncology and cardiology [11]. In the field of ophthalmology, personalized medicine is novel and powerful tool for diagnosing and managing eye diseases. Genetic testing has revealed that approximately 40 loci account for 15% to 65% of the variability in AMD pathology [12]. This advancement supports a movement towards early screening and personalized risk stratification, for earlier diagnosis and prevention of irreversible vision loss by earlier intervention [12].

Beyond genetics, personalized medicine in ophthalmology also incorporates artificial intelligence (AI) and pharmacogenomics. AI-supported technologies can assist physicians in analyzing multimodal retinal imaging to detect early signs of DR, AMD and glaucoma, allowing for earlier and more precise interventions [13]. Meanwhile, personalized selection of intraocular pressure (IOP)-lowering medications based on pharmacogenomic variants has shown potential benefits in glaucoma management, mitigating risk of treatment failure and adverse events [14]. These advancements improve the specificity of care, improve patient outcomes and minimize the risk of unnecessary treatment exposure and side effects.

This narrative review explores the current landscape of gene therapy in retinal diseases, highlighting recent advancements, barriers to adoption, and future directions. Although gene therapy has shown substantial promise and early clinical success, its broader implementation remains influenced by practical, economic, and regulatory factors that are discussed in later sections. Additionally, the concept of genetic eligibility raises important questions about equitable access and individualized treatment approaches. By examining the latest developments in gene therapy delivery, the role of genetic testing in treatment selection, and emerging innovations such as Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-based editing, this review aims to provide an overview of this evolving field.

2. Advances in Retinal Gene Therapy

2.1. Overview of Gene Therapy Strategies

2.1.1. Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors

Adeno-associated virus (AVV) vectors are among the most widely used gene delivery systems in ophthalmology due to their ability to transduce quiescent cells, low immunogenicity, and capacity for long-term gene expression in postmitotic tissues [15]. AAV vectors derive from a replication-defective parvovirus and deliver episomal genetic material, reducing the risk of genomic integration-associated mutagenesis [16]. Their primary limitation is a packaging capacity of approximately 5.0 kb, which restricts the size of therapeutic genes that can be delivered [2]. Additionally, AAV-based gene therapies face large scale production challenges [17]. Despite these challenges, AAV-mediated gene therapy has demonstrated remarkable clinical success, exemplified by voretigene neparvovec-rzyl [15]. Ongoing clinical trials continue to expand the applications of AAV vectors to other monogenic retinal disorders.

Beyond these general properties, adeno-associated virus exists as a family of naturally occurring and engineered serotypes with distinct capsid structures and tissue tropism. In the eye, AAV2 has been the most extensively used serotype for subretinal delivery because of its robust transduction of retinal pigment epithelium and photoreceptors, forming the basis for voretigene neparvovec and several other IRD trials. AAV5 and AAV8 also demonstrate strong tropism for outer retinal layers when delivered subretinally and are being explored to optimize transduction efficiency and durability of expression. In contrast, vectors such as AAV2.7m8 and other engineered capsids have been developed to enhance penetration of the inner limiting membrane and improve transduction of inner retinal cells after intravitreal injection, which is particularly relevant for disorders targeting retinal ganglion cells or Müller glia. These serotype-specific differences in tropism and route-of-administration performance are central to vector selection in clinical trial design and will likely shape future indications and delivery strategies for ocular gene therapy (Table 1).

2.1.2. Lentiviral Vectors

Lentiviral (LV) vectors offer an alternative gene delivery system with a larger transgene capacity (~8 kb) and the ability to integrate into the host genome, enabling stable long-term transgene expression [16,18]. LV vectors can transduce both dividing and non-dividing cells, making them suitable for targeting retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and photoreceptors [18]. While integration into the host genome raises concerns regarding insertional mutagenesis, advances in self-inactivating (SIN) vectors have mitigated these risks [18]. SIN vectors are modified viral vectors in which the enhancer and promoter sequences in the long terminal repeat (LTR) have been deleted, rendering the LTR transcriptionally inactive after integration. This design helps prevent mobilization by replication-competent viruses [19]. LV-based therapies have shown promise in treating retinitis pigmentosa (RP), LCA2, and AMD, particularly given the eye’s compartmentalized nature, which limits systemic dissemination of the vector [1].

2.1.3. CRISPR-Cas9

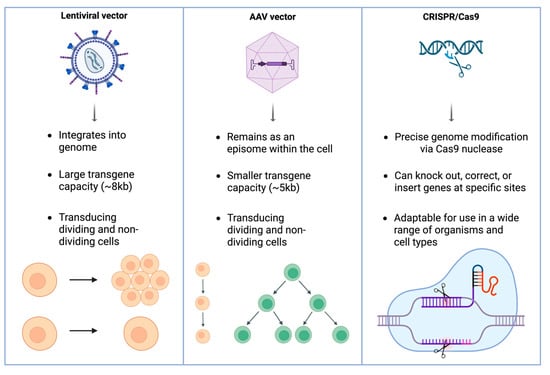

CRISPR-Cas9-based gene editing is a highly precise approach to gene therapy for inherited retinal diseases. CRISPR-Cas9 enables targeted modification of disease-causing mutations, offering the potential to correct the underlying genetic defect, although irreversible retinal degeneration that precedes treatment remains a major limitation [20]. Preclinical studies have demonstrated CRISPR’s efficacy in correcting mutations in a number of different genes [20]. Among these, the CEP290 gene (the most common mutation in LCA) encodes a centrosomal protein found at the connecting cilium of photoreceptors, where it plays a key role in ciliogenesis and the transport of molecules within cilia [21]. In addition, CRISPR has shown promise in targeting the RHO gene, which encodes rhodopsin, a light-sensitive protein in rod cells essential for vision in low light. Mutations in RHO are a common cause of RP [22]. The VEGFA gene, which encodes the vascular endothelial growth factor A protein, is another target of interest due to its key role in stimulating blood vessel formation and its implication in AMD [23]. Despite its promise, CRISPR faces challenges related to delivery efficiency, off-target effects, and immune responses [16]. Ongoing research into base editing, prime editing, and improved delivery vectors aims to enhance CRISPR’s therapeutic potential for ophthalmic applications (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of principal gene therapy platforms in ophthalmology. Lentiviral vectors integrate into the host genome and accommodate large transgenes, AAV vectors remain episomal with smaller cargo capacity, and CRISPR/Cas9 enables precise genome editing for mutation correction or gene knockout. Although AAV vectors can enter both dividing and non-dividing cells, their genomes persist primarily as episomes; thus, in rapidly dividing tissues, episomal dilution reduces long-term expression, whereas post-mitotic retinal cells permit durable transgene expression.

2.2. Key Clinical Trials and Approved Therapies

2.2.1. Voretigene Neparvovec-Rzyl (Luxturna)

Voretigene neparvovec-rzyl (VN; AAV2-hRPE65v2) is the first ocular gene augmentation therapy approved by the FDA for IRDs caused by biallelic RPE65 mutations [24]. Approved in 2017 by the FDA and in 2018 in the European Union (EU), VN is an AAV2-based vector delivering a functional copy of the RPE65 gene to viable retinal cells, thereby restoring visual cycle in affected individuals [24,25]. Clinical evidence supporting the efficacy of VN stems from two Phase 1 trials and a pivotal Phase 3 randomized trial, in which treated patients demonstrated significant improvements in multi-luminance mobility testing and full-field stimulus test (FST), indicating improvements in functional vision and residual visual function, respectively [24,26]. These benefits were accompanied by a favorable safety profile [24,26]. Further validation has come from interim analyses of the PERCEIVE study, the largest real-world registry of VN-treated patients to date [24]. The study confirmed sustained FST improvements consistent with prior trials [24]. However, measures such as best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and foveal thickness have remained largely unchanged over the two-year follow-up. The PERCEIVE trial included participants aged 2 to 51 years (with the mean age being 19.5 years) and demonstrated consistent long-term safety and efficacy outcomes across this entire age range [24]. These findings further substantiate the durability and safety profile of VN in real-world clinical settings (Table 2).

2.2.2. X-Linked Retinoschisis

X-linked retinoschisis (XLRS) is an X-linked recessive vitreoretinal dystrophy characterized by macular schisis, caused by mutations in the RS1 gene, which is responsible for encoding retinoschisin, a protein essential for retinal cell adhesion and structural integrity [27]. Gene therapy strategies have focused on delivering a functional copy of RS1 via AAV vectors to restore homeostatic protein function and retinal cell architecture. In a Phase I/II dose-escalation trial, Pennesi et al. (2022) evaluated intravitreal administration of rAAV2tYF-CB-hRS1 [28]. The therapy demonstrated an acceptable overall safety profile, although there were observations of chronic uveitis at higher dose levels not responsive to immunosuppressive therapy in 3/27 (11.1%) patients, and 2/27 (7.4%) patients experienced retinal detachment [28]. No significant improvements in BCVA, visual fields (VFs), or electroretinography (ERG) were observed. Similarly, Cukras et al. (2018) tested AAV8-RS1 on nine patients in a Phase I/IIa trial [29]. There were reports of mild transient intraocular inflammation in 4/9 (44.4%) patients, which were managed and resolved with oral and topical corticosteroid treatments. One patient exhibited transient macular schisis cavity closure, a favorable structural response, although the recurrence of schisis suggests limited durability rather than an adverse event. Otherwise, treatment was overall well tolerated [29]. Despite these promising early findings, further refinement in vector design and administration is needed to optimize therapeutic outcomes.

2.2.3. Stargardt Disease

Stargardt disease, which is the most common hereditary retinal disease, is most often the result of mutations in the ABCA4 gene. Other less frequent forms of Stargardt disease are caused by mutations in ELOVL4 and PROM1 genes. Stargardt disease leads to progressive central vision loss due to RPE dysfunction and lipofuscin accumulation [30,31]. The ABCA4 gene encodes a flippase importer protein that facilitates the removal of vitamin A derivatives from photoreceptor cells, thereby preventing their toxic accumulation in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) [32]. Parker et al. (2022) conducted a phase I/IIa trial on 22 participants using an equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) vector encoding ABCA4 (EIAV-ABCA4) [33]. In this study, subretinal injections were well-tolerated across three dose levels, with one case of chronic ocular hypertension. Although one patient demonstrated reduced macular flecks, 6/22 (27%) participants exhibited increased RPE atrophy on fundus autofluorescence as a result of subretinal injection with EIAV-ABCA4. While subretinal administration was generally tolerated, the observation that approximately one-quarter of participants developed increased RPE atrophy raises important safety concerns and highlights the need for further refinement of ABCA4 delivery approaches [33]. Beyond ABCA4-associated disease, certain PRPH2 variants can produce a Stargardt-like macular dystrophy and are relatively common, reflecting the broader genetic heterogeneity within this phenotype. A major challenge for ABCA4 gene replacement therapy is the large size of the ABCA4 coding sequence, which exceeds the packaging capacity of standard AAV vectors and limits the feasibility of traditional AAV-mediated delivery. To overcome this constraint, several alternative platforms including dual-AAV systems, RNA-based therapies, lentiviral vectors, and emerging non-viral technologies are under active investigation to enable efficient delivery of full-length ABCA4 and expand therapeutic options for patients with Stargardt disease.

2.2.4. Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD)

Gene therapies for AMD aim to provide sustained anti-VEGF expression, reducing the burden of frequent intravitreal injections. ADVM-022, developed by Adverum Biotechnologies, utilizes an AAV.7m8 vector to express an aflibercept-like protein [34]. The phase 1 OPTIC trial enrolled 30 participants, with 15 in each of the high- and low-dose cohorts, and demonstrated a reduction in anti-VEGF injection frequency of 99% and 85% in the high- and low-dose groups, respectively [34]. Although BCVA and central subfield thickness (CST) remained stable, anterior segment inflammation, particularly in high-dose groups, required long-term steroid management [35]. Similarly, RGX-314 (REGENXBIO Inc.), delivered using AAV8 via subretinal injection (SRI), encodes a ranibizumab-like monoclonal antibody fragment [35]. Early-phase RGX-314 trials involving 42 participants across 5 cohorts have demonstrated promising efficacy, with cohort 3 showing a mean BCVA gain of +14 letters at 2 years, while cohorts 4 and 5 showed changes of +1 and −1 letters, respectively, at 1.5 years. CST changed by +2 µm in cohort 3 and decreased by 46 µm and 93 µm in cohorts 4 and 5, respectively. Additionally, mean annualized anti-VEGF injection frequency was reduced by 66.7% in cohort 3 at 3 years, and by 58.3% and 81.2% in cohorts 4 and 5, respectively, at 1.5 years. While the therapy was generally well-tolerated, localized retinal pigmentary changes were noted at the injection site for 28/42 (67%) of participants [35]. Both ADVM-022 and RGX-314 continue to be evaluated in ongoing trials to determine their long-term safety and efficacy in AMD management.

2.3. Challenges with Delivery Methods: Subretinal vs. Intravitreal

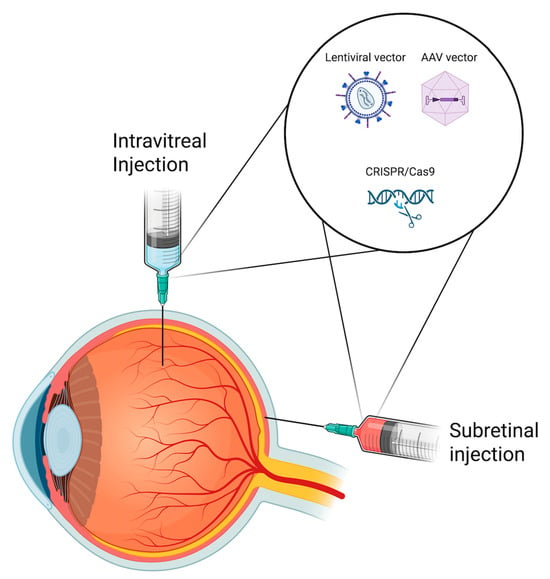

The choice between subretinal and intravitreal administration for gene therapy in ophthalmology presents its own challenges, each with implications on the efficacy and safety of treatment (Figure 2).

SRI allows for direct delivery of viral vectors to the retinal pigment epithelium and photoreceptors, but requires surgical precision to minimize complications [36]. A primary concern is temporary retinal detachment, which can damage photoreceptors and compromise visual acuity, particularly if the fovea is affected, potentially leading to macular hole formation [37]. Additionally, permanent retinal detachment and cataract progression have been observed postoperatively [37]. The procedure also demands meticulous surgical skill, as any subretinal injection inherently creates a localized retinal detachment, and detachment of the fovea is the main concern due to its impact on visual acuity. Reflux of vector material not only reduces efficacy by decreasing the amount delivered to the intended subretinal space, but also increases immune activation as free vector becomes exposed within the vitreous [38]. The mechanical properties of the retina further complicate delivery, as its limited elasticity makes precise vector placement difficult [38]. Moreover, instrument tip tremors (~100 μm) present substantial risks given the narrow margin of the subretinal space [39]. As a result, SRI requires exceptional dexterity.

In contrast, intravitreal injection (IVI) is less invasive and more accessible but has its own limitations. While it allows efficient transduction of inner retinal cells such as ganglion and Müller cells, it is less effective at reaching deeper layers like photoreceptors and the RPE due to the presence of multiple anatomical and physiological barriers [37]. The inner limiting membrane (ILM) serves as a significant diffusion barrier, restricting AAV penetration beyond the inner retina [37]. Additionally, the injected vector faces dilution in the vitreous fluid, reducing its effective concentration before reaching target cells [37,40]. Immune responses further compromise delivery, as neutralizing antibodies in the vitreous can degrade the vector and impair its integrity [40]. Even after internalization by target cells, the vector remains vulnerable to proteasomal degradation, which may prevent successful nuclear transgene delivery [40]. These challenges limit the efficacy of IVI in achieving broad retinal transduction and penetrating deeper layers of the retina.

Looking ahead, several strategies are being explored to overcome the inherent limitations of both subretinal and intravitreal delivery. For SRI, advances in robotic-assisted microsurgery and real-time OCT-guided injection aim to improve precision, reduce foveal trauma, and minimize reflux by stabilizing the needle tip during vector delivery. Novel flexible cannula designs and automated injection platforms may further reduce variability in bleb formation and lower the risk of unintended macular detachment. In parallel, engineered AAV capsids capable of penetrating the inner limiting membrane are driving renewed interest in IVI, offering the possibility of achieving outer retinal transduction without invasive surgery. Techniques such as ILM modulation, suprachoroidal injection, and the development of capsids with enhanced ganglion-cell or photoreceptor tropism are also emerging as promising avenues for improving intravitreal efficiency. Together, these innovations suggest a future where vector design, surgical robotics, and less invasive delivery routes converge to enable safer, more consistent, and broadly applicable gene therapy delivery across a wider range of retinal diseases.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of subretinal and intravitreal delivery routes used in retinal gene therapy. Gene delivery systems such as adeno-associated viral (AAV) and lentiviral vectors, as well as CRISPR/Cas9-based constructs, can be administered via either approach depending on target cell accessibility and therapeutic objective.

3. Personalised Medicine in Gene Therapy

3.1. Influence of Genetic Testing on Clinical Outcomes

IRDs occur as a result of mutations in specific genes involved in retinal development, function and maintenance [41]. The genetic complexity of IRDs is reflected in the large number of genetic associations linked to these conditions. To date, nearly 300 genes have been identified whose mutations are linked to phenotypic changes that define specific clinical subtypes [12]. Genetic testing is the sole method by which causative genetic variants can be identified, enabling accurate diagnosis and precise genotype–phenotype correlations [42].

Genotype-phenotype correlation refers to the relationship between specific genetic mutations and their associated clinical manifestations [42]. In gene therapy, understanding genotype-phenotype correlations can help predict disease progression and establish personalized treatment strategies [43]. For instance, pathogenic BEST1 variants are associated with central visual acuity impairment, leading to Best vitelliform macular dystrophy (BVMD) [42,44]. In contrast, pathogenic variants in IQCB1 lead to early childhood blindness, which precedes end-stage renal failure in early adulthood seen in Senior-Loken syndrome [45,46]. The phenotypic presentation of a mutation is often based on the degree of functional impairment caused by the altered gene, which can present along a gradient classified as mild (slow-progressing, late-onset, minimal dysfunction) to severe (rapidly progressing, early-onset, and debilitating) [47,48]. Conditions may impact not only the retina but also multiple organ systems and are broadly classified as either syndromic or non-syndromic [47]. For instance, some USH2A variants are associated with both retinitis pigmentosa and sensorineural hearing loss, while others cause isolated RP [49,50]. In contrast, BEST1 variants primarily affect the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), leading to Best vitelliform macular dystrophy, which typically shows an abnormal electro-oculogram (EOG) without extraocular manifestations [51,52].

3.2. Genetic Eligibility

An individual’s genetic mutation, including its location and type, significantly influences the effectiveness and response to prescribed gene therapies. Current gene therapies are designed to address well-characterized, monogenic mutations of specific targetable genes [53]. These therapies depend on accurately identifying the causative gene, as gene replacement targets gene-level dysfunction rather than a specific variant. For example, voretigene neparvovec treats any biallelic pathogenic variant in RPE65, illustrating that gene replacement therapies are directed at the affected gene rather than a single mutation. In contrast, multifactorial conditions like AMD arise from a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental or lifestyle factors [54]. This complexity makes gene therapy options more challenging to develop, as addressing a single genetic factor may not be sufficient to halt disease progression [55,56].

3.3. Pharmacogenetics

Gene editing approaches such as CRISPR-Cas9 require molecular interactions within the primary sequence of DNA [57]. Consequently, natural genetic variation amongst individuals can impact treatment efficacy. Variability in each individual’s genome is influenced by parental DNA and somatic mutations that determine their phenotypic traits [58]. Gene therapies target the genome to treat diseases, and genetic variations can thereby influence their effectiveness. For instance, CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing relies on endonuclease cleavage at targeted sites of nucleotide sequences [59]. Cell-based studies have shown that CRISPR-Cas9 editing can result in off-target effects, including unintended alterations at germline single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) [59]. For instance, Yang et al. identified a single-high efficiency off-target site generated by a SNV, and predicted that SNVs have a ~1.5–8.5% of creating off-target sites in human genomes. With numerous CRISPR-Cas9–based retinal gene therapies currently in clinical trials, it is crucial to consider how natural genetic variation across different populations may influence treatment outcomes [60]. Large-scale sequencing datasets now offer valuable insights into human genetic diversity, enabling better assessment of CRISPR endonuclease efficacy across various genomic contexts [61,62,63,64].

Current strategies to enhance specificity include high-fidelity Cas9 nucleases and high specificity vector delivery systems to ensure CRISPR-Cas9 goes to the intended site [65,66]. For instance, in the BRILLIANCE study—a clinical trial targeting CEP290 mutation–associated inherited retinal degeneration—researchers used a high-fidelity Cas9 nuclease, delivered via an AAV5 vector with strong photoreceptor specificity, to administer CRISPR-Cas9 and its associated proteins [67]. Consequently, this minimized the exposure to non-target tissues resulting in no serious adverse events present [67].

4. Barriers to Widespread Adoption

4.1. Cost and Accessibility

Retinal gene therapies mark a significant advancement in treating retinal diseases. However, their high costs and complex manufacturing processes pose significant challenges to widespread testing and availability. To date, the only approved gene therapy, voretigene neparvovec-rzyl, is priced at USD 425,000 per eye [68,69]. Additionally, as gene therapies are typically one-time treatments, the cost is heavily frontloaded, creating an immediate economic burden for healthcare systems and patients alike [68]. In Canada, the therapy is publicly funded and free for eligible patients, alleviating out-of-pocket expenses. However, this transfers the financial burden to the publicly funded healthcare system, where high upfront costs pose sustainability concerns for provincial budgets.

Economic evaluations suggest that VN provides greater quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) at a lower overall cost compared to standard medical care without gene therapy, with estimated lifetime costs per patient of $2.2 million versus $2.8 million, respectively [70]. The treatment remains cost-effective if at least 8.8% of its long-term benefits persist beyond the third year post-treatment [70]. However, the main challenge in evaluating gene therapy economic feasibility is the promise of long-term benefits. Long-term outcome data for these therapies remain limited due to their relatively recent introduction. Moreover, because IRDs often manifest from birth, gene therapy candidates are typically young and may be particularly vulnerable to long-term treatment failure or adverse effects. Real-world studies have so far confirmed the safety and effectiveness of these therapies, consistent with clinical trial results. However, with follow-up periods extending only up to two years, these studies are limited in their ability to predict potential long-term complications [24,71].

4.2. Ethical and Regulatory Challenges

Ethical concerns surrounding long-term patient outcomes remain a key challenge in the broader adoption of gene therapy. As clinical use is still in its early stages, the absence of long-term data complicates informed consent and patient education. A narrative analysis of patient perspectives revealed a consistent desire for clearer information and transparency, regardless of baseline knowledge [72,73,74,75,76,77]. While many patients reported limited understanding of gene therapy, they generally expressed trust in their healthcare providers’ guidance on its efficacy and safety [72]. However, this reliance suggests that future discoveries of adverse effects may undermine patient-provider relationships and trust.

Emerging gene therapies face many regulatory hurdles during development. First, these therapies are most effective in targeting rare, inherited genetic diseases, making patient recruitment challenging [78]. RP, the most common IRD, affects approximately 1 in 3000–4500 individuals worldwide, while the combined prevalence of all IRDs is around 1 in 3450 [79]. Due to their rarity, clinical trials for IRD gene therapies often face challenges with patient enrollment [80]. To overcome this limitation, ongoing clinical studies involve multi-centre collaborations to increase patient recruitment efforts [81].

4.3. Scalability and Infrastructure

Although current gene delivery vectors allow for highly tissue-specific targeting, large-scale vector manufacturing remains a major bottleneck limiting the scalability of gene therapy for clinical trials and widespread use [82]. The transient transfection method is the most widely used system for large-scale AAV production due to its rapid development and turnaround time [82]. Recent studies have reported successful mass production using this approach [83,84]. However, current manufacturing techniques have not yet enabled its widespread use, resulting in production rates that remain insufficient to meet the dosage demands of clinical applications [82]. Additionally, maintaining product yield and quality during rAAV manufacturing poses significant challenges when scaling up from lab bench to mass production [82]. Transient transfection involves incubating a plasmid with growth reagents in cell lines to stimulate rAAV production. Proper mixing and incubation of the transfection reagent with plasmid DNA are essential for maintaining sample homogenization and minimizing variability [82]. While this process is well-controlled on the lab bench using vortexing or shaking, achieving the same level of consistency at a large production scale is challenging [85,86]. Studies have reported productivity losses and intersample inconsistencies, leading to reagent waste and potentially compromising gene therapy efficacy [85,86].

5. Future Directions

Recent clinical trials exploring gene therapy use in other ocular regions have emerged, such as achromatopsia and Myocilin-associated Glaucoma (MYOC).

Achromatopsia is an autosomal recessive condition characterized by reduced or absent cone function, resulting in severe color blindness, photophobia, nystagmus, and reduced central visual acuity from infancy. It affects 1 in 30,000 individuals and is caused by pathogenic variants that impact cone photoreceptor function [87]. Ongoing clinical trials target specific genetic subtypes and have shown early improvements in color discrimination, with long-term follow-up still underway to assess durability and safety [87].

Glaucoma is a progressive optic neuropathy that often is characterized by increased IOP, either due to increased production or reduced outflow [88]. Mutations in the MYOC gene are the most common known cause of inherited glaucoma, affecting an estimated three million people worldwide [89]. These mutations often manifest as juvenile open-angle glaucoma, a form that is typically resistant to conventional pharmacological treatments. Importantly, surgical interventions for glaucoma have a finite duration of effectiveness; procedures performed in early childhood often lose efficacy over time, and repeat surgeries may provide diminishing benefit due to scarring and the progressive loss of viable conjunctival ‘real estate’ needed for aqueous drainage [90,91,92,93]. Given the early onset and invasive nature of standard treatment approaches, gene therapy offers a promising one-time alternative, with strong support from preclinical studies [94]. Researchers successfully developed an animal model that mimics the MYOC mutation in humans, demonstrating elevated IOP and glaucomatous progression [95]. Using this model, they demonstrated how CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing can lower IOP in mutated mice and prevent the development of glaucoma [96]. Furthermore, Patil et al. used animal models to demonstrate that LV vectors efficiently deliver Cas9 for gene editing, which gene editing subsequently lowers IOP [97]. Current research provides strong preclinical evidence supporting the efficacy of gene therapy for treating MYOC-associated glaucoma. The research group aims to use future studies to focus on minimizing off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9 base editing, by exploring alternative gene delivery approaches before advancing towards the clinical stage [97].

Current vectors often have adverse effects involving the host’s antiviral defense mechanisms, such as causing intraocular inflammation or loss of transduced, functioning cells after successful treatments [98]. How viral vectors interact with host tissue is predominantly based on non-conserved, surface-exposed proteins and can be modified to preferentially interact with specific host receptors [99]. These sequences can be collected and mapped into a library, with ongoing research using experimental approaches to evaluate their efficacy and specificity [100,101]. However, starting libraries have a plethora of different sequence variations, with many having fundamental issues in genome packaging and assembly. An algorithm to distinguish optimal vectors from all possible sequences will enhance treatment efficacy and reduce off-target effects. AI is an emerging field of research, with specific applications in refining gene delivery vehicles to treat IRDs [102,103]. Recent studies developed AI models having a greater packaging success rate than traditional libraries [95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,104]. In the future, AI may be able to provide in silico predictions of functional vector candidates over the traditional ‘trial-and-error’ laboratory experiments in validating vector feasibility [105]. This allows a cost-effective and time-efficient approach, by prioritizing high-potential variants before lab testing [98].

Table 1.

Comparison of Gene Delivery Strategies.

Table 1.

Comparison of Gene Delivery Strategies.

| Name | Description | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors | Small, non-pathogenic viruses capable of delivering genetic material to both dividing and non-dividing cells. They deliver genetic material as an episome, reducing the risk of insertional mutagenesis [15,16]. |

|

|

| Lentiviral (LV) vectors | Derived from retroviruses and can infect both dividing and non-dividing cells. They integrate into the host genome, enabling stable, long-term expression [16,18]. |

|

|

| Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 | Genome-editing technology that allows for precise DNA modifications, including gene knockout, correction, or insertion [107,108]. |

|

|

Table 2.

Key Clinical Trials.

Table 2.

Key Clinical Trials.

| First Author | Gene Therapy Mechanism | Treatment Condition(s) | Sample Size (n) | Limitations | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russell et al. (2017) [6] | Gene augmentation therapy using AAV2-hRPE65v2 to restore RPE65 function in retinal cells [6]. | RPE65 mutation-associated IRDs, including LCA2 and RP | n = 31 | No participants under age 4; No data on patients whose visual acuity was better than specified in the protocol (visual acuity 20/60, visual field less than 20 degrees in any meridian) [6]. | Mean bilateral MLMT score improved by 1.8 light levels vs. 0.2 in controls at 1 year [6]. |

| Pennesi et al. (2022) [28] | Gene augmentation therapy using intravitreal delivery of rAAV2tYF-CB-hRS1 to enhance retinal transduction efficiency in XLRS patients [28]. | X-linked Retinoschisis (XLRS) | n = 27 | Ocular inflammation, chronic uveitis, retinal detachments [28,29] | No significant improvements in BCVA, VFs, or ERG [28]. |

| Cukras et al. (2018) [29] | Gene augmentation therapy using intravitreal injection of a self-complementary AAV8-RS1 vector to restore retinoschisin expression in XLRS patients [29]. | X-linked Retinoschisis (XLRS) | n = 9 | Ocular inflammation, chronic uveitis, retinal detachments [28,29] | BCVA remained within ±10 letters of baseline in all patients over 18 months; no statistically significant ERG changes observed [29]. Transient schisis cavity closure observed in 1 patient (11%); 4/9 patients (44.4%) had dose-dependent ocular inflammation that resolved with treatment [29]. |

| Parker et al. (2022) [33] | Gene augmentation therapy using an equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) encoding ABCA4 gene delivered to RPE cells [33] | Stargardt Disease | n = 22 | RPE atrophy; Ocular hypertension; No clinically significant changes [33] | The treatment was not associated with any clinically meaningful improvements in visual function tests [33] |

| Busbee et al. (2021) [34] | Gene silencing anti-VEGF gene therapy using an AAV.7m8 vector to provide sustained anti-VEGF expression [34]. | Age-related macular degeneration | n = 30 | Ocular inflammation requiring steroid use; Unknown long-term efficacy [34] | 93% (high dose) and 67% (low dose) remained injection-free; BCVA was maintained (mean change: −2.5 to +0.2 letters) [34] CRT improved by 19.7 to 132.7 μm across Cohorts 1–3 [34] |

| Khanani et al. (2022) [35] | Anti-VEGF gene therapy using an AAV8 vector encoding a ranibizumab-like antibody fragment to provide long-term VEGF suppression [35]. | Age-related macular degeneration | n = 42 | Postoperative conjunctival hemorrhage; Post operative inflammation; Irritation and pain; Visual acuity reduction [35] | BCVA improved by +14 letters in Cohort 3 at 2 years; Cohorts 4 and 5 had changes of +1 and −1 letters at 1.5 years [35]. 67% showed retinal pigmentary changes; injection burden reduced by 58.3% to 81.2%; CRT change ranged from +2 to −93 µm [35]. |

AAV = Adeno-associated virus; ABCA4 = ATP-binding cassette sub-family A member 4; BCVA = Best corrected visual acuity; CRT = Central retinal thickness; EIAV = Equine infectious anemia virus; ERG = electroretinography; IRDs = Inherited retinal diseases; LCA2 = Leber congenital amaurosis type 2; MLMT = Multi-luminance mobility testing; RPE = Retinal pigment epithelium; RPE65 = Retinal pigment epithelium-specific 65 kDa protein; RS1 = Retinoschisin 1; RP = Retinitis pigmentosa; VEGF = Vascular endothelial growth factor; VFs = Visual Fields; XLRS = X-linked retinoschisis.

6. Conclusions

Gene therapy is a promising approach for treating inherited and acquired retinal diseases by targeting underlying genetic etiology rather than symptom management approaches [110]. Although addressing the underlying genetic cause is essential, symptom management remains a critical component of patient care, and patient-reported outcome measures provide valuable insight into functional vision, treatment satisfaction, and real-world quality-of-life impacts. This review has assessed key clinical trials targeting prevalent IRDs, such as X-linked retinoschisis and Stargardt disease, which have all achieved clinical success. However, challenges remain in scalability and vector viability [82,98]. Emerging alternatives, including LV vectors and non-viral delivery systems, offer potential solutions to these challenges but require further optimization to mitigate risks such as insertional mutagenesis and off-target effects. Given the ongoing innovation and advancements in vector engineering, genome editing strategies, and viral system delivery, gene therapy demonstrates the promise of becoming a powerful tool for providing personalized, precision treatment for lifelong IRDs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.R.B., T.D., M.B., B.K.T., A.P., P.Y., and P.A.; Data curation, F.R.B., T.D., B.L., and M.A.; Writing—original draft preparation, F.R.B., T.D., B.L., and M.A.; Writing—review and editing, F.R.B., T.D., B.L., M.A., B.K.T., M.B., A.P., P.Y., and P.A.; Supervision, M.B., B.K.T., A.P., P.Y., and P.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hu, M.L.; Edwards, T.L.; O’Hare, F.; Hickey, D.G.; Wang, J.-H.; Liu, Z.; Ayton, L.N. Gene Therapy for Inherited Retinal Diseases: Progress and Possibilities. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2021, 104, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botto, C.; Rucli, M.; Tekinsoy, M.D.; Pulman, J.; Sahel, J.-A.; Dalkara, D. Early and Late Stage Gene Therapy Interventions for Inherited Retinal Degenerations. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2022, 86, 100975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, K.; Bennett, J. Immunology of AAV-Mediated Gene Transfer in the Eye. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdy, R.; John, M.; Bray, A.; Clare, A.J.; Copland, D.A.; Chan, Y.K.; Henderson, R.H.; Nerinckx, F.; Leroy, B.P.; Yang, P.; et al. Gene Therapy-Associated Uveitis (GTAU): Understanding and Mitigating the Adverse Immune Response in Retinal Gene Therapy. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2025, 106, 101354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-H.; Gessler, D.J.; Zhan, W.; Gallagher, T.L.; Gao, G. Adeno-Associated Virus as a Delivery Vector for Gene Therapy of Human Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.; Bennett, J.; Wellman, J.A.; Chung, D.C.; Yu, Z.-F.; Tillman, A.; Wittes, J.; Pappas, J.; Elci, O.; McCague, S.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Voretigene Neparvovec (AAV2-hRPE65v2) in Patients with RPE65-Mediated Inherited Retinal Dystrophy: A Randomised, Controlled, Open-Label, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askou, A.L.; Jakobsen, T.S.; Corydon, T.J. Retinal Gene Therapy: An Eye-Opener of the 21st Century. Gene Ther. 2021, 28, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drag, S.; Dotiwala, F.; Upadhyay, A.K. Gene Therapy for Retinal Degenerative Diseases: Progress, Challenges, and Future Directions. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrella, S.; Indrieri, A.; Franco, B.; Banfi, S. Mutation-Independent Therapies for Retinal Diseases: Focus on Gene-Based Approaches. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 588234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, E.A. The Precision Medicine Initiative: A New National Effort. JAMA 2015, 313, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, D.; Quake, S.R.; McCabe, E.R.B.; Chng, W.J.; Chow, E.K.; Ding, X.; Gelb, B.D.; Ginsburg, G.S.; Hassenstab, J.; Ho, C.-M.; et al. Enabling Technologies for Personalized and Precision Medicine. Trends Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 497–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panikker, P.; Roy, S.; Ghosh, A.; Poornachandra, B.; Ghosh, A. Advancing Precision Medicines for Ocular Disorders: Diagnostic Genomics to Tailored Therapies. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 906482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, M.; Pachauri, P.; Akram, W.; Parvez, M.; Ahmad, S.; Yahya, Z. Enhancing Retinal Disease Diagnosis through AI: Evaluating Performance, Ethical Considerations, and Clinical Implementation. Inform. Health 2024, 1, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Wang, L.; Wei, X. Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics in Glaucoma Therapeutics: The Way to Personalized Therapy. Chin. Med. J. 2023, 136, 2573–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Fu, Y.; Ma, L.; Yao, Y.; Ge, S.; Yang, Z.; Fan, X. AAV for Gene Therapy in Ocular Diseases: Progress and Prospects. Research 2023, 6, 0291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, C.E.; High, K.A.; Joung, J.K.; Kohn, D.B.; Ozawa, K.; Sadelain, M. Gene Therapy Comes of Age. Science 2018, 359, eaan4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Dalby, P.A. Challenges in Scaling up AAV-Based Gene Therapy Manufacturing. Trends Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 1268–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenijevic, Y.; Berger, A.; Udry, F.; Kostic, C. Lentiviral Vectors for Ocular Gene Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, H.; Blömer, U.; Takahashi, M.; Gage, F.H.; Verma, I.M. Development of a Self-Inactivating Lentivirus Vector. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 8150–8157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohia, A.; Sahel, D.K.; Salman, M.; Singh, V.; Mariappan, I.; Mittal, A.; Chitkara, D. Delivery Strategies for CRISPR/Cas Genome Editing Tool for Retinal Dystrophies: Challenges and Opportunities. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 17, 153–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnight, E.R.; Wiley, L.A.; Drack, A.V.; Braun, T.A.; Anfinson, K.R.; Kaalberg, E.E.; Halder, J.A.; Affatigato, L.M.; Mullins, R.F.; Stone, E.M.; et al. CEP290 Gene Transfer Rescues Leber Congenital Amaurosis Cellular Phenotype. Gene Ther. 2014, 21, 662–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, D.; Ragi, S.D.; Tsang, S.H. Therapy in Rhodopsin-Mediated Autosomal Dominant Retinitis Pigmentosa. Mol. Ther. 2020, 28, 2139–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Sosa, J.F.; Caviedes-Bucheli, J.; Díaz Barrera, L.E. Gene Expression of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A and Its Receptors in Dental Pulp of Immature and Mature Teeth. Eur. Endod. J. 2021, 6, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.D.; Simonelli, F.; Sahni, J.; Holz, F.G.; Maier, R.; Fasser, C.; Suhner, A.; Stiehl, D.P.; Chen, B.; Audo, I.; et al. Real-World Safety and Effectiveness of Voretigene Neparvovec: Results up to 2 Years from the Prospective, Registry-Based PERCEIVE Study. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Hussain, R.M.; Weng, C.Y. Voretigene Neparvovec in Retinal Diseases: A Review of the Current Clinical Evidence. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2020, 14, 3855–3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, A.M.; Russell, S.; Wellman, J.A.; Chung, D.C.; Yu, Z.-F.; Tillman, A.; Wittes, J.; Pappas, J.; Elci, O.; Marshall, K.A.; et al. Efficacy, Safety, and Durability of Voretigene Neparvovec-Rzyl in RPE65 Mutation–Associated Inherited Retinal Dystrophy. Ophthalmology 2019, 126, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, C.A.; Wei, L.W.; Sieving, P.A. X-Linked Retinoschisis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2023, 13, a041288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennesi, M.E.; Yang, P.; Birch, D.G.; Weng, C.Y.; Moore, A.T.; Iannaccone, A.; Comander, J.I.; Jayasundera, T.; Chulay, J.; Chulay, J.; et al. Intravitreal Delivery of rAAV2tYF-CB-hRS1 Vector for Gene Augmentation Therapy in Patients with X-Linked Retinoschisis. Ophthalmol. Retin. 2022, 6, 1130–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukras, C.; Wiley, H.E.; Jeffrey, B.G.; Sen, H.N.; Turriff, A.; Zeng, Y.; Vijayasarathy, C.; Marangoni, D.; Ziccardi, L.; Kjellstrom, S.; et al. Retinal AAV8-RS1 Gene Therapy for X-Linked Retinoschisis: Initial Findings from a Phase I/IIa Trial by Intravitreal Delivery. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 2282–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujinami, K.; Waheed, N.; Laich, Y.; Yang, P.; Fujinami-Yokokawa, Y.; Higgins, J.J.; Lu, J.T.; Curtiss, D.; Clary, C.; Michaelides, M. Stargardt Macular Dystrophy and Therapeutic Approaches. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 108, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohli, P.; Tripathy, K.; Kaur, K. Stargardt Disease. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khuzaei, S.; Broadgate, S.; Foster, C.R.; Shah, M.; Yu, J.; Downes, S.M.; Halford, S. An Overview of the Genetics of ABCA4 Retinopathies, an Evolving Story. Genes 2021, 12, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.A.; Erker, L.R.; Audo, I.; Choi, D.; Mohand-Said, S.; Sestakauskas, K.; Benoit, P.; Appelqvist, T.; Krahmer, M.; Ségaut-Prévost, C.; et al. Three-Year Safety Results of SAR422459 (EIAV-ABCA4) Gene Therapy in Patients with ABCA4-Associated Stargardt Disease: An Open-Label Dose-Escalation Phase I/IIa Clinical Trial, Cohorts 1-5. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 240, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busbee, B.; Boyer, D.S.; Khanani, A.M.; Wykoff, C.C.; Pieramici, D.J.; Regillo, C.; Danzig, C.J.; Joondeph, B.C.; Major, J.; Hoang, C.; et al. Phase 1 Study of Intravitreal Gene Therapy with ADVM-022 for Neovascular AMD (OPTIC Trial). Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2021, 62, 352. [Google Scholar]

- Khanani, A.M.; Thomas, M.J.; Aziz, A.A.; Weng, C.Y.; Danzig, C.J.; Yiu, G.; Kiss, S.; Waheed, N.K.; Kaiser, P.K. Review of Gene Therapies for Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Eye 2022, 36, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irigoyen, C.; Amenabar Alonso, A.; Sanchez-Molina, J.; Rodríguez-Hidalgo, M.; Lara-López, A.; Ruiz-Ederra, J. Subretinal Injection Techniques for Retinal Disease: A Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siontas, O.; Ahn, S. Challenges in AAV-Based Retinal Gene Therapies and the Role of Magnetic Nanoparticle Platforms. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladha, R.; Caspers, L.E.; Willermain, F.; de Smet, M.D. Subretinal Therapy: Technological Solutions to Surgical and Immunological Challenges. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 846782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Edwards, T.L.; Meenink, H.C.M.; Beelen, M.J.; Naus, G.J.L.; Simunovic, M.P.; de Smet, M.D.; MacLaren, R.E. Robot-Assisted Retinal Surgery: Overcoming Human Limitations. In Surgical Retina; Ohji, M., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 109–114. ISBN 978-981-13-6214-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, M.; Ofri, R. The Future of Retinal Gene Therapy: Evolving from Subretinal to Intravitreal Vector Delivery. Neural Regen. Res. 2021, 16, 1751–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, H.; Tripathy, K.; Vohra, V. Retinal Dystrophies. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ellingford, J.M.; Hufnagel, R.B.; Arno, G. Phenotype and Genotype Correlations in Inherited Retinal Diseases: Population-Guided Variant Interpretation, Variable Expressivity and Incomplete Penetrance. Genes 2020, 11, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvasi, M.; Casillo, L.; Avogaro, F.; Abbouda, A.; Vingolo, E.M. Gene Therapy in Hereditary Retinal Dystrophies: The Usefulness of Diagnostic Tools in Candidate Patient Selections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrukhin, K.; Koisti, M.J.; Bakall, B.; Li, W.; Xie, G.; Marknell, T.; Sandgren, O.; Forsman, K.; Holmgren, G.; Andreasson, S.; et al. Identification of the Gene Responsible for Best Macular Dystrophy. Nat. Genet. 1998, 19, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, E.A.; Loeys, B.; Khanna, H.; Hellemans, J.; Sudbrak, R.; Fan, S.; Muerb, U.; O’Toole, J.F.; Helou, J.; Attanasio, M.; et al. Nephrocystin-5, a Ciliary IQ Domain Protein, Is Mutated in Senior-Loken Syndrome and Interacts with RPGR and Calmodulin. Nat. Genet. 2005, 37, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellingford, J.M.; Sergouniotis, P.I.; Lennon, R.; Bhaskar, S.; Williams, S.G.; Hillman, K.A.; O’Sullivan, J.; Hall, G.; Ramsden, S.C.; Lloyd, I.C.; et al. Pinpointing Clinical Diagnosis through Whole Exome Sequencing to Direct Patient Care: A Case of Senior-Loken Syndrome. Lancet 2015, 385, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Rodriguez, R.; Lantero, E.; Blanco-Kelly, F.; Avila-Fernandez, A.; Martin Merida, I.; del Pozo-Valero, M.; Perea-Romero, I.; Zurita, O.; Jiménez-Rolando, B.; Swafiri, S.T.; et al. RPE65-Related Retinal Dystrophy: Mutational and Phenotypic Spectrum in 45 Affected Patients. Exp. Eye Res. 2021, 212, 108761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, L.; Arrigo, A.; Antropoli, A.; Manitto, M.P.; Martina, E.; Aragona, E.; Bandello, F.; Battaglia Parodi, M. Association Between Genotype and Phenotype Severity in ABCA4-Associated Retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2023, 141, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Ramírez, L.P.; Lenassi, E.; Ellingford, J.M.; Sergouniotis, P.I.; Ramsden, S.C.; Bruce, I.A.; Black, G.C.M. Establishing Genotype–Phenotype Correlation in USH2A-Related Disorders to Personalize Audiological Surveillance and Rehabilitation. Otol. Neurotol. 2020, 41, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenassi, E.; Vincent, A.; Li, Z.; Saihan, Z.; Coffey, A.J.; Steele-Stallard, H.B.; Moore, A.T.; Steel, K.P.; Luxon, L.M.; Héon, E.; et al. A Detailed Clinical and Molecular Survey of Subjects with Nonsyndromic USH2A Retinopathy Reveals an Allelic Hierarchy of Disease-Causing Variants. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2015, 23, 1318–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, R.; Millar, I.D.; Leroy, B.P.; Urquhart, J.E.; Fearon, I.M.; De Baere, E.; Brown, P.D.; Robson, A.G.; Wright, G.A.; Kestelyn, P.; et al. Biallelic Mutation of BEST1 Causes a Distinct Retinopathy in Humans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008, 82, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Poornachandra, B.; Verma, A.; Mehta, R.A.; Phalke, S.; Battu, R.; Ramprasad, V.L.; Peterson, A.S.; Ghosh, A.; Seshagiri, S. Next Generation Sequencing Identifies Novel Disease-Associated BEST1 Mutations in Bestrophinopathy Patients. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, N.; Sundaresan, Y.; Gopalakrishnan, P.; Beryozkin, A.; Hanany, M.; Levanon, E.Y.; Banin, E.; Ben-Aroya, S.; Sharon, D. Inherited Retinal Diseases: Linking Genes, Disease-Causing Variants, and Relevant Therapeutic Modalities. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2022, 89, 101029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, K.J.; Liu, Z.; Millen, A.E.; Iyengar, S.K.; Blodi, B.A.; Johnson, E.; Snodderly, D.M.; Klein, M.L.; Gehrs, K.M.; Tinker, L.; et al. Joint Associations of Diet, Lifestyle, and Genes with Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, 2286–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasiak, J.; Pawlowska, E.; Ciupińska, J.; Derwich, M.; Szczepanska, J.; Kaarniranta, K. A New Generation of Gene Therapies as the Future of Wet AMD Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, D.L.; Burr, A.; Pennesi, M. RPE65-Related Leber Congenital Amaurosis/Early-Onset Severe Retinal Dystrophy. In GeneReviews®; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Asmamaw, M.; Zawdie, B. Mechanism and Applications of CRISPR/Cas-9-Mediated Genome Editing. Biol. Targets Ther. 2021, 15, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Coorens, T.H.H.; Uddin, M.M.; Ardlie, K.G.; Lennon, N.; Natarajan, P. Genetic Variation across and within Individuals. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2024, 25, 548–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Grishin, D.; Wang, G.; Aach, J.; Zhang, C.-Z.; Chari, R.; Homsy, J.; Cai, X.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, J.-B.; et al. Targeted and Genome-Wide Sequencing Reveal Single Nucleotide Variations Impacting Specificity of Cas9 in Human Stem Cells. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.A.; Zhang, F. Implications of Human Genetic Variation in CRISPR-Based Therapeutic Genome Editing. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1095–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lek, M.; Karczewski, K.J.; Minikel, E.V.; Samocha, K.E.; Banks, E.; Fennell, T.; O’Donnell-Luria, A.H.; Ware, J.S.; Hill, A.J.; Cummings, B.B.; et al. Analysis of Protein-Coding Genetic Variation in 60,706 Humans. Nature 2016, 536, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durbin, R.M.; Altshuler, D.; Durbin, R.M.; Abecasis, G.R.; Bentley, D.R.; Chakravarti, A.; Clark, A.G.; Collins, F.S.; De La Vega, F.M.; Donnelly, P.; et al. A Map of Human Genome Variation from Population-Scale Sequencing. Nature 2010, 467, 1061–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVean, G.A.; Altshuler, D.M.; Durbin, R.M.; Abecasis, G.R.; Bentley, D.R.; Chakravarti, A.; Clark, A.G.; Donnelly, P.; Eichler, E.E.; Flicek, P.; et al. An Integrated Map of Genetic Variation from 1,092 Human Genomes. Nature 2012, 491, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auton, A.; Abecasis, G.R.; Altshuler, D.M.; Durbin, R.M.; Abecasis, G.R.; Bentley, D.R.; Chakravarti, A.; Clark, A.G.; Donnelly, P.; Eichler, E.E.; et al. A Global Reference for Human Genetic Variation. Nature 2015, 526, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimasu, H.; Shi, X.; Ishiguro, S.; Gao, L.; Hirano, S.; Okazaki, S.; Noda, T.; Abudayyeh, O.O.; Gootenberg, J.S.; Mori, H.; et al. Engineered CRISPR-Cas9 Nuclease with Expanded Targeting Space. Science 2018, 361, 1259–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinstiver, B.P.; Pattanayak, V.; Prew, M.S.; Tsai, S.Q.; Nguyen, N.T.; Zheng, Z.; Joung, J.K. High-Fidelity CRISPR–Cas9 Nucleases with No Detectable Genome-Wide off-Target Effects. Nature 2016, 529, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, E.A.; Aleman, T.S.; Jayasundera, K.T.; Ashimatey, B.S.; Kim, K.; Rashid, A.; Jaskolka, M.C.; Myers, R.L.; Lam, B.L.; Bailey, S.T.; et al. Gene Editing for CEP290-Associated Retinal Degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 1972–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spark’s Gene Therapy Price Tag: $850,000. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 122. [CrossRef]

- FDA Approves Hereditary Blindness Gene Therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.; Buessing, M.; O’Connell, T.; Pitluck, S.; Ciulla, T.A. Cost-Effectiveness of Voretigene Neparvovec-Rzyl vs Standard Care for RPE65-Mediated Inherited Retinal Disease. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019, 137, 1115–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Zhao, P.Y.; Branham, K.; Schlegel, D.; Fahim, A.T.; Jayasundera, K.T.; Khan, N.; Besirli, C.G. Real-World Outcomes of Voretigene Neparvovec Treatment in Pediatric Patients with RPE65-Associated Leber Congenital Amaurosis. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2022, 260, 1543–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiyegbusi, O.L.; Macpherson, K.; Elston, L.; Myles, S.; Washington, J.; Sungum, N.; Briggs, M.; Newsome, P.N.; Calvert, M.J. Patient and Public Perspectives on Cell and Gene Therapies: A Systematic Review. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, W.D.; Wyatt, G.E.; Liu, H.; Williams, J.K.; DiNardo, A.D.; Mitsuyasu, R.T. Pilot Assessment of HIV Gene Therapy-Hematopoietic Stem Cell Clinical Trial Acceptability Among Minority Patients and Their Advisors. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2010, 102, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, H.; Mitchell, M.J.; Goldstein-Leever, A.; Shook, L.; Malik, P.; Crosby, L.E. Patient Perspectives on Gene Transfer Therapy for Sickle Cell Disease. Adv. Ther. 2017, 34, 2007–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peay, H.; Fischer, R.; Beaverson, K.; Morris, C.; Hesterlee, S.E.; Ricotti, V.; Martin, A.; Rensch, C.; Wand, H.; Mansfield, C.A.; et al. Parent and Adult Patient Attitudes About Gene Therapy as a Therapeutic Option for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Value Health 2018, 21, S256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, C.; Petersen, A.; Munsie, M. ‘No One Here’s Helping Me, What Do You Do?’: Addressing Patient Need for Support and Advice about Stem Cell Treatments. Regen. Med. 2017, 12, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, K.J.; Kwon, B.K.; Lo, C.; Snyder, J.; Illes, J. Perspectives on Strategies and Challenges in the Conversation about Stem Cells for Spinal Cord Injury. Spinal Cord 2015, 53, 811–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kempf, L.; Goldsmith, J.C.; Temple, R. Challenges of Developing and Conducting Clinical Trials in Rare Disorders. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2018, 176, 773–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanany, M.; Shalom, S.; Ben-Yosef, T.; Sharon, D. Comparison of Worldwide Disease Prevalence and Genetic Prevalence of Inherited Retinal Diseases and Variant Interpretation Considerations. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2024, 14, a041277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustine, E.F.; Adams, H.R.; Mink, J.W. Clinical Trials in Rare Disease: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Child Neurol. 2013, 28, 1142–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belite Bio Finalizes Phase 3 Clinical Trial Plans for Advanced Dry AMD Treatment with Tinlarebant (LBS-008)|Belite Bio, Inc. Available online: https://investors.belitebio.com/news-releases/news-release-details/belite-bio-finalizes-phase-3-clinical-trial-plans-advanced-dry/ (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Fu, Q.; Polanco, A.; Lee, Y.S.; Yoon, S. Critical Challenges and Advances in Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus (rAAV) Biomanufacturing. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2023, 120, 2601–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.N.T.; Park, D.; Canova, C.T.; Sangerman, J.; Srinivasan, P.; Ou, R.W.; Barone, P.W.; Neufeld, C.; Wolfrum, J.M.; Springs, S.L.; et al. Perfusion-Based Production of rAAV via an Intensified Transient Transfection Process. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2025, 122, 1424–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Z.; Lv, Y.-L.; Wang, X.-T.; Yuan, L.-H.; Zhao, K.; Du, Z.-M.; Xiao, X. Production of Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus Through High-Cell-Density Transfection of HEK293 Cells Based on Fed-Perfusion Culture. Hum. Gene Ther. 2025, 36, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, M.D.; Emerson, S.G.; Punt, J.; Goff, W.D. Decreased Naïve T-Cell Production Leading to Cytokine Storm as Cause of Increased COVID-19 Severity with Comorbidities. Aging Dis. 2020, 11, 742–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Lee, K.-J.; Daris, M.; Lin, Y.; Wolfe, T.; Sheng, J.; Plewa, C.; Wang, S.; Meisen, W.H. Creation of a High-Yield AAV Vector Production Platform in Suspension Cells Using a Design-of-Experiment Approach. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020, 18, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, M.F.; Borchert, G.A. Gene Therapy for Achromatopsia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Understanding Glaucoma: Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis, Treatment. Available online: https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/what-is-glaucoma (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Sharma, R.; Grover, A. Myocilin-Associated Glaucoma: A Historical Perspective and Recent Research Progress. Mol. Vis. 2021, 27, 480. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Wiggs, J.L. Common and Rare Genetic Risk Factors for Glaucoma. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014, 4, a017244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, A.; Souzeau, E.; Agar, A.; Ridge, B.; Dubowsky, A.; Burdon, K.P.; Craig, J.E. Identification of a Novel MYOC Mutation, p.(Trp373*), in a Family with Open Angle Glaucoma. Gene 2014, 545, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.E.; Baird, P.N.; Healey, D.L.; McNaught, A.I.; McCartney, P.J.; Rait, J.L.; Dickinson, J.L.; Roe, L.; Fingert, J.H.; Stone, E.M.; et al. Evidence for Genetic Heterogeneity within Eight Glaucoma Families, with the GLC1A Gln368STOP Mutation Being an Important Phenotypic Modifier. Ophthalmology 2001, 108, 1607–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, Y.-H.; Wei, Y.-T.; Bai, Y.-J.; Duan, S.; Lin, M.-K.; Saragovi, H.U.; Ge, J. Pro370Leu MYOC Gene Mutation in a Large Chinese Family with Juvenile-Onset Open Angle Glaucoma: Correlation Between Genotype and Phenotype. Mol. Vis. 2008, 14, 1533–1539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Anton, N.; Geamănu, A.; Iancu, R.; Pîrvulescu, R.A.; Popa-Cherecheanu, A.; Barac, R.I.; Bandol, G.; Bogdănici, C.M. A Mini-Review on Gene Therapy in Glaucoma and Future Directions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zode, G.S.; Kuehn, M.H.; Nishimura, D.Y.; Searby, C.C.; Mohan, K.; Grozdanic, S.D.; Bugge, K.; Anderson, M.G.; Clark, A.F.; Stone, E.M.; et al. Reduction of ER Stress via a Chemical Chaperone Prevents Disease Phenotypes in a Mouse Model of Primary Open Angle Glaucoma. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 3542–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.; Zode, G.; Kasetti, R.B.; Ran, F.A.; Yan, W.; Sharma, T.P.; Bugge, K.; Searby, C.C.; Fingert, J.H.; Zhang, F.; et al. CRISPR-Cas9–Based Treatment of Myocilin-Associated Glaucoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 11199–11204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.V.; Kaipa, B.R.; Ranshing, S.; Sundaresan, Y.; Millar, J.C.; Nagarajan, B.; Kiehlbauch, C.; Zhang, Q.; Jain, A.; Searby, C.C.; et al. Lentiviral Mediated Delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 Reduces Intraocular Pressure in a Mouse Model of Myocilin Glaucoma. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, K.; Rodríguez-Bocanegra, E.; Dauletbekov, D.; Fischer, M.D. Immune Responses to Retinal Gene Therapy Using Adeno-Associated Viral Vectors—Implications for Treatment Success and Safety. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2021, 83, 100915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbandje-McKenna, M.; Kleinschmidt, J. AAV Capsid Structure and Cell Interactions. In Adeno-Associated Virus: Methods and Protocols; Snyder, R.O., Moullier, P., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 47–92. ISBN 978-1-61779-370-7. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, B.A.; Miranda, A.X.; Reed, S.C.; Bergman, R.E.; Kemp, J.D.J.; Reddy, A.P.; Pantone, M.V.; Fox, E.K.; Dorand, R.D.; Hurley, P.J.; et al. An in Vitro CRISPR Screen of Cell-Free DNA Identifies Apoptosis as the Primary Mediator of Cell-Free DNA Release. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, R.A.; Wang, Q.; Xu, H.; Hu, G.; Bell, P.; Arroyo, E.J.; Sims, J.J.; Wilson, J.M. Vector Affinity and Receptor Distribution Define Tissue-Specific Targeting in an Engineered AAV Capsid. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e0017423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Lin, L.F.; Oraskovich, S.V.; de Jesús, J.A.R.; Listgarten, J.; Schaffer, D.V. Computationally Guided AAV Engineering for Enhanced Gene Delivery. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2024, 49, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.D.; Kummer, M.; Kondratov, O.; Banerjee, A.; Moskalenko, O.; Zolotukhin, S. Applying Machine Learning to Predict Viral Assembly for Adeno-Associated Virus Capsid Libraries. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2021, 20, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.; Brookes, D.H.; Busia, A.; Carneiro, A.; Fannjiang, C.; Popova, G.; Shin, D.; Donohue, K.C.; Lin, L.F.; Miller, Z.M.; et al. Optimal Trade-off Control in Machine Learning–Based Library Design, with Application to Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) for Gene Therapy. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadj3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.; Fakhiri, J.; Grimm, D. Fantastic AAV Gene Therapy Vectors and How to Find Them—Random Diversification, Rational Design and Machine Learning. Pathogens 2022, 11, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milone, M.C.; O’Doherty, U. Clinical Use of Lentiviral Vectors. Leukemia 2018, 32, 1529–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. The New Frontier of Genome Engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 2014, 346, 1258096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komor, A.C.; Badran, A.H.; Liu, D.R. CRISPR-Based Technologies for the Manipulation of Eukaryotic Genomes. Cell 2017, 168, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayanoğlu, F.B.; Elçin, A.E.; Elçin, Y.M. Bioethical Issues in Genome Editing by CRISPR-Cas9 Technology. Turk. J. Biol. 2020, 44, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahel, J.-A.; Marazova, K.; Audo, I. Clinical Characteristics and Current Therapies for Inherited Retinal Degenerations. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5, a017111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).