Readmissions to a Surgical Intensive Care Unit: Incidence and Risk Stratification for Personalized Patient Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data and Variables

2.4. Organization of the SICU

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Readmissions

3.2. Risk Factors for UR-SICU

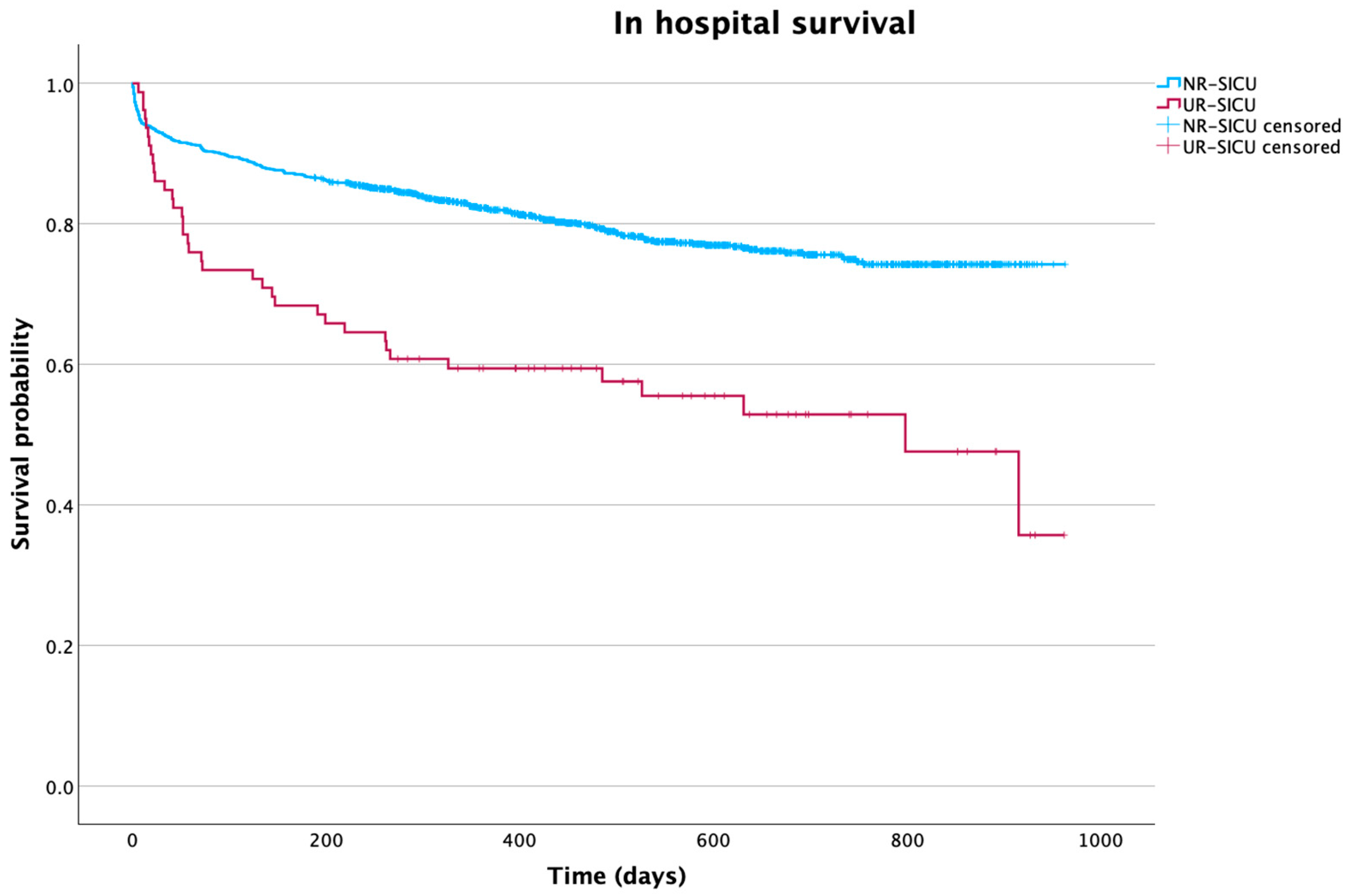

3.3. Impact of Readmission

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| MICU | Medical intensive care unit |

| SICU | Surgical intensive care unit |

| UR-SICU | Unplanned readmission to the surgical intensive care unit |

| UR-ICU | Unplanned readmission to the intensive care unit |

| NR-ICU | No readmission to the intensive care unit |

| APACHE | Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Disease Classification System II |

| SOFA | Sequential Organ Failure Assessment |

| RRT | Renal replacement therapy |

| MDRB | Multidrug-resistant bacteria |

| ICUAW | ICU-acquired weakness |

| ISS | Injury severity score |

References

- Hoffman, R.L.; Saucier, J.; Dasani, S.; Collins, T.; Holena, D.N.; Fitzpatrick, M.; Tsypenyuk, B.; Martin, N.D. Development and implementation of a risk identification tool to facilitate critical care transitions for high-risk surgical patients. Int. J. Qual. Health Care J. Int. Soc. Qual. Health Care 2017, 29, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, M.; Worrall-Carter, L.; Page, K. Intensive care readmission: A contemporary review of the literature. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2014, 30, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, A.A.; Higgins, T.L.; Zimmerman, J.E. The association between ICU readmission rate and patient outcomes. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 41, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, A.L.; Hofer, T.P.; Hayward, R.A.; Strachan, C.; Watts, C.M. Who bounces back? Physiologic and other predictors of intensive care unit readmission. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 29, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnuma, T.; Shinjo, D.; Brookhart, A.M.; Fushimi, K. Predictors associated with unplanned hospital readmission of medical and surgical intensive care unit survivors within 30 days of discharge. J. Intensive Care 2018, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C.; Huang, S.J.; Tsauo, J.Y.; Ko, W.J. Definition, risk factors and outcome of prolonged surgical intensive care unit stay. Anaesth. Intensive Care 2010, 38, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, T.; Kim, D.E.; Jo, E.M.; Kim, D.W.; Kim, H.J.; Seong, E.Y.; Song, S.H.; Rhee, H. Differences in the incidence, characteristics, and outcomes of patients with acute kidney injury in the medical and surgical intensive care units. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2024, 43, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchino, S.; Kellum, J.A.; Bellomo, R.; Doig, G.S.; Morimatsu, H.; Morgera, S.; Schetz, M.; Tan, I.; Bouman, C.; Macedo, E.; et al. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: A multinational, multicenter study. JAMA 2005, 294, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, H.; Park, M.; Kim, I.Y. Nephrology consultation improves the clinical outcomes of patients with acute kidney injury. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2025, 44, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, C.T.; Franca, S.A.; Okamoto, V.N.; Salge, J.M.; Carvalho, C.R.R. Infection as an independent risk factor for mortality in the surgical intensive care unit. Clinics 2013, 68, 1103–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.U.; Eichenhorn, M.; DiGiovine, B.; Ritz, J.; Jordan, J.; Rubinfeld, I. Different Harm and Mortality in Critically Ill Medical vs Surgical Patients: Retrospective Analysis of Variation in Adverse Events in Different Intensive Care Units. Perm. J. 2018, 22, 16–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woldhek, A.L.; Rijkenberg, S.; Bosman, R.J.; van der Voort, P.H.J. Readmission of ICU patients: A quality indicator? J. Crit. Care 2017, 38, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, A.L.; Watts, C. Patients readmitted to ICUs*: A systematic review of risk factors and outcomes. Chest 2000, 118, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, A.A.; Higgins, T.L.; Zimmerman, J.E. Intensive care unit readmissions in U.S. hospitals: Patient characteristics, risk factors, and outcomes. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 40, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzoni, C.R.; Corrêa, T.D.; Filho, R.R.; Serpa Neto, A.; Assunção, M.S.C.; Pardini, A.; Schettino, G.P.P. Readmission to the Intensive Care Unit: Incidence, Risk Factors, Resource Use, and Outcomes. A Retrospective Cohort Study. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2017, 14, 1312–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaben, A.; Corrêa, F.; Reinhart, K.; Settmacher, U.; Gummert, J.; Kalff, R.; Sakr, Y. Readmission to a surgical intensive care unit: Incidence, outcome and risk factors. Crit. Care 2008, 12, R123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejerina Álvarez, E.E.; Gómez Mediavilla, K.A.; Rodríguez Solís, C.; Valero González, N.; Lorente Balanza, J.Á. Risk factors for readmission to ICU and analysis of intra-hospital mortality. Med. Clin. 2022, 158, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, R. ICU Readmission Is a More Complex Metric Than We First Imagined. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, 2064–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Yang, K.M.; Kwak, J.Y.; Jung, Y.T. Risk Factors for Invasive Candidiasis in Critically Ill Patients Who Underwent Emergency Gastrointestinal Surgery for Complicated Intra-Abdominal Infection. Surg. Infect. 2024, 25, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.-H.; Wu, Y.; Nguyen, V.; Rastogi, S.; McConnell, B.K.; Wijaya, C.; Uretsky, B.F.; Poh, K.-K.; Tan, H.-C.; Fujise, K. Heart Protection by Combination Therapy with Esmolol and Milrinone at Late-Ischemia and Early Reperfusion. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2011, 25, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Quinn, P.C.; Gee, K.N.; King, S.A.; Yune, J.-M.J.; Jenkins, J.D.; Whitaker, F.J.; Suresh, S.; Bollig, R.W.; Many, H.R.; Smith, L.M. Predicting Unplanned Readmissions to the Intensive Care Unit in the Trauma Population. Am. Surg. 2024, 90, 2285–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M. Readmission to intensive care: A review of the literature. Aust. Crit. Care Off. J. Confed. Aust. Crit. Care Nurses 2006, 19, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.M.; Martin, C.M.; Keenan, S.P.; Sibbald, W.J. Patients readmitted to the intensive care unit during the same hospitalization: Clinical features and outcomes. Crit. Care Med. 1998, 26, 1834–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharaj, R.; Terblanche, M.; Vlachos, S. The Utility of ICU Readmission as a Quality Indicator and the Effect of Selection. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nates, J.L.; Nunnally, M.; Kleinpell, R.; Blosser, S.; Goldner, J.; Birriel, B.; Fowler, C.S.; Byrum, D.; Miles, W.S.; Bailey, H.; et al. ICU Admission, Discharge, and Triage Guidelines: A Framework to Enhance Clinical Operations, Development of Institutional Policies, and Further Research. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 44, 1553–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fein, I.A. Readmissions as a Quality Metric: Ready for Prime Time? Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, 821–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.E.S.; Ratcliffe, S.J.; Halpern, S.D. Assessing the utility of ICU readmissions as a quality metric: An analysis of changes mediated by residency work-hour reforms. Chest 2015, 147, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Sluisveld, N.; Bakhshi-Raiez, F.; de Keizer, N.; Holman, R.; Wester, G.; Wollersheim, H.; van der Hoeven, J.G.; Zegers, M. Variation in rates of ICU readmissions and post-ICU in-hospital mortality and their association with ICU discharge practices. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alban, R.F.; Nisim, A.A.; Ho, J.; Nishi, G.K.; Shabot, M.M. Readmission to surgical intensive care increases severity-adjusted patient mortality. J. Trauma 2006, 60, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.-T.; Chen, W.-L.; Chao, C.-M.; Lai, C.-C. The outcomes and prognostic factors of the patients with unplanned intensive care unit readmissions. Medicine 2018, 97, e11124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, B.-H.; Na, S.J.; Lee, D.-S.; Chung, C.R.; Suh, G.Y.; Jeon, K. Readmission and hospital mortality after ICU discharge of critically ill cancer patients. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscedere, J.; Waters, B.; Varambally, A.; Bagshaw, S.M.; Boyd, J.G.; Maslove, D.; Sibley, S.; Rockwood, K. The impact of frailty on intensive care unit outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2017, 43, 1105–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.M. Biological age as a predictor of unplanned intensive care readmission during the same hospitalization. Heart Lung J. Crit. Care 2023, 62, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuSara, A.K.; Nazer, L.H.; Hawari, F.I. ICU readmission of patients with cancer: Incidence, risk factors and mortality. J. Crit. Care 2019, 51, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaechea Astigarraga, P.M.; Álvarez Lerma, F.; Beato Zambrano, C.; Gimeno Costa, R.; Gordo Vidal, F.; Durá Navarro, R.; Ruano Suarez, C.; Aldabó Pallás, T.; Garnacho Montero, J.; ENVIN-HELICS Study Group; et al. Epidemiology and prognosis of patients with a history of cancer admitted to intensive care. A multicenter observational study. Med. Intensiva 2021, 45, 332–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelbaky, A.M.; Eldelpshany, M.S. Patient Outcomes and Management Strategies for Intensive Care Unit (ICU)-Associated Delirium: A Literature Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e61527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotfis, K.; Marra, A.; Ely, E.W. ICU delirium—A diagnostic and therapeutic challenge in the intensive care unit. Anaesthesiol. Intensive Ther. 2018, 50, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, T.D.; Thompson, J.L.; Pandharipande, P.P.; Brummel, N.E.; Jackson, J.C.; Patel, M.B.; Hughes, C.G.; Chandrasekhar, R.; Pun, B.T.; Boehm, L.M.; et al. Clinical phenotypes of delirium during critical illness and severity of subsequent long-term cognitive impairment: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2018, 6, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo-Valbuena, B.; Gordo, F.; Abella, A.; Garcia-Manzanedo, S.; Garcia-Arias, M.-M.; Torrejón, I.; Varillas-Delgado, D.; Molina, R. Risk factors associated with the development of delirium in general ICU patients. A prospective observational study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.-L.; Shehabi, Y.; Walsh, T.S.; Pandharipande, P.P.; Ball, J.A.; Spronk, P.; Longrois, D.; Strøm, T.; Conti, G.; Funk, G.-C.; et al. Comfort and patient-centred care without excessive sedation: The eCASH concept. Intensive Care Med. 2016, 42, 962–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Varga-Martínez, O.; Badenes, R.; Gordaliza, C.; de Miguel Manso, S.; Landázuri Castillo, G.E.; Armenteros Aragon, C.; Fernández Castro, M.; Martin Santos, A.B.; Lopez Herrero, R.; Navarro Pérez, R.; et al. Clinical guidelines and strategic plan for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of delirium: The zero delirium project. Rev. Esp. Anestesiol. Reanim. 2025, 72, 501805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonna, J.E.; Dalton, A.; Presson, A.P.; Zhang, C.; Colantuoni, E.; Lander, K.; Howard, S.; Beynon, J.; Kamdar, B.B. The Effect of a Quality Improvement Intervention on Sleep and Delirium in Critically Ill Patients in a Surgical ICU. Chest 2021, 160, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouillet, J.-L.; Collange, O.; Belafia, F.; Blot, F.; Capellier, G.; Cesareo, E.; Constantin, J.-M.; Demoule, A.; Diehl, J.-L.; Guinot, P.-G.; et al. Tracheotomy in the intensive care unit: Guidelines from a French expert panel: The French Intensive Care Society and the French Society of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 2018, 37, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Saran, S.; Baronia, A.K. The practice of tracheostomy decannulation-a systematic review. J. Intensive Care 2017, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumholz, H.M. Post-hospital syndrome--an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 100–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, M.A. The truth about consequences--post-intensive care syndrome in intensive care unit survivors and their families. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 40, 2506–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Readmission Due to Medical Cause | 41 (50%) | Readmission Due to Surgical Cause | 41 (50%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiologic | 6 (7.3%) | Hemorrhage | 19 (23.2%) |

| Respiratory | 11 (13.4%) | Sepsis or septic shock | 17 (20.7%) |

| Neurologic | 7 (8.5%) | Decreased level of consciousness | 2 (2.4%) |

| Infectious | 10 (12.2%) | Arterial thrombosis | 3 (3.7%) |

| Metabolic | 4 (4.9%) | ||

| Other | 3 (3.7%) |

| Variable | NR-SICU (n = 1279) | UR-SICU (n = 82) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age a | 60 (48–71) | 66 (56–73) | <0.001 |

| Sex. Male b | 749 (58.6%) | 50 (61%) | 0.667 |

| Severity scale a | |||

| APACHE II | 9 (6–13) | 13 (9–16) | <0.001 |

| SOFA | 2 (1–5) | 4 (1–6) | 0.002 |

| Comorbidities b | |||

| Neoplasia | 471 (36.8%) | 43 (52.4%) | 0.005 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 105 (8.2%) | 7 (8.5%) | 0.917 |

| Heart failure | 67 (5.2%) | 7 (8.5%) | 0.202 |

| Liver disease | 123 (9.9%) | 10 (12.2%) | 0.446 |

| CKD | 97 (7.6%) | 9 (11.0%) | 0.267 |

| COPD | 162 (12.7%) | 14 (17.1%) | 0.249 |

| Diabetes | 242 (18.9%) | 23 (28.0%) | 0.043 |

| Hypertension | 534 (41.8%) | 45 (54.9%) | 0.020 |

| Primary diagnosis for SICU admission b | <0.001 | ||

| Postoperative care. Planned admission. | 678 (53.0%) | 49 (59.7%) | |

| Medical complication in a postoperative patient | 90 (7%) | 11 (13.4%) | |

| Trauma | 207 (16.2%) | 1 (2.4%) | |

| Emergency surgery | 228 (17.8%) | 19 (23.2%) | |

| Liver transplant | 76 (5.9%) | 2 (2.4%) | |

| Nature of first SICU admission b | |||

| Emergency admission | 601 (46.9%) | 34 (41.5%) | 0.331 |

| Variable | NR-SICU (n = 1279) | UR-SICU (n = 82) | p Value | Univariate OR, p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vasoactive drugs b | 359 (30.6%) | 31 (42.5%) | 0.034 | OR 1.67 (IC95% 1.03–2.70), p = 0.03 |

| Days of invasive ventilation a | 6 (4–9) | 6 (4–10) | 0.303 | N/A |

| Tracheostomy b | 111 (8.6%) | 12 (14.6%) | 0.068 | OR 1.80 (IC95% 0.94–3.43), p = 0.07 |

| ARDS b | 19 (1.5%) | 2 (2.4%) | 0.497 | OR 1.65 (IC95% 0.38–7.24), p = 0.50 |

| Pneumonia b | 92 (7.2%) | 10 (12.2%) | 0.095 | OR 1.79 (IC95% 0.89–3.58), p = 0.10 |

| Bacteremia b | 32 (2.5%) | 4 (5.2%) | 0.158 | OR 2.10 (IC95% 0.73–6.15), p = 0.16 |

| Infection or colonization by MDRB b | 67 (5.3%) | 6 (7.8%) | 0.346 | OR 1.51 (IC95% 0.63–3.61), p = 0.34 |

| Renal insufficiency b | 264 (20.7%) | 26 (31.7%) | 0.025 | OR 1.78 (IC95% 1.09–2.89), p = 0.02 |

| RRT | 49 (3.8%) | 10 (12.2%) | <0.001 | OR 3.48 (IC95% 1.69–7.16), p < 0.001 |

| Delirium | 148 (11.6%) | 19 (23.2%) | 0.002 | OR 2.30 (IC95% 1.34–3.95), p = 0.002 |

| ICUAW | 67 (5.2%) | 6 (7.3%) | 0.441 | OR 1.42 (IC95% 0.60–3.39), p = 0.42 |

| Days of primary SICU admission a | 2 (1–5) | 3 (2–8) | 0.00 | N/A |

| Transfer day. Weekday b | 1030 (80.5%) | 70 (85.36%) | 0.281 | OR 1.41 (IC95% 0.75–2.64), p = 0.283 |

| Variable | Odds Ratio (OR) | IC 95% | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.026 | 1.010–1.042 | 0.002 |

| Neoplasia | 1.792 | 1.140–2.818 | 0.012 |

| Delirium | 1.855 | 1.061–3.243 | 0.030 |

| Tracheostomy | 1.638 | 0.850–3.156 | 0.140 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramos, S.; Ramos Fernández, R.; Sevilla, R.; Cabezuelo, E.; Calvo, A.; Vela, R.; Menendez, C.; Garcia Ramos, S.; Hortal Iglesias, J.; Garutti, I.; et al. Readmissions to a Surgical Intensive Care Unit: Incidence and Risk Stratification for Personalized Patient Care. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 618. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120618

Ramos S, Ramos Fernández R, Sevilla R, Cabezuelo E, Calvo A, Vela R, Menendez C, Garcia Ramos S, Hortal Iglesias J, Garutti I, et al. Readmissions to a Surgical Intensive Care Unit: Incidence and Risk Stratification for Personalized Patient Care. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(12):618. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120618

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamos, Silvia, Rafael Ramos Fernández, Raul Sevilla, Eneko Cabezuelo, Alberto Calvo, Raquel Vela, Claudia Menendez, Sergio Garcia Ramos, Javier Hortal Iglesias, Ignacio Garutti, and et al. 2025. "Readmissions to a Surgical Intensive Care Unit: Incidence and Risk Stratification for Personalized Patient Care" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 12: 618. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120618

APA StyleRamos, S., Ramos Fernández, R., Sevilla, R., Cabezuelo, E., Calvo, A., Vela, R., Menendez, C., Garcia Ramos, S., Hortal Iglesias, J., Garutti, I., & Piñeiro, P. (2025). Readmissions to a Surgical Intensive Care Unit: Incidence and Risk Stratification for Personalized Patient Care. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(12), 618. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120618