Abstract

Objectives: Prior research has found that social anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty (IU) are both related to problematic smartphone use (PSU) severity. However, research about the mediating effect of IU from social anxiety to PSU is limited. Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of self-report online data from 329 college students in the United States, evaluating IU, social anxiety, and PSU through structural equation modeling. Results: We found that confirmatory factor analytic models of social anxiety, IU and PSU each fit well. Our overall structural equation model also indicated good fit, and IU acted as a significant mediator of the link between social anxiety and PSU severity. To test model specificity, we compared it with an alternative model that added a direct path from social anxiety to PSU. Although the alternative model showed slightly better fit, the improvement was minimal, and theoretical grounds supported keeping the simpler initial model. Conclusions: These results indicate that IU may represent a critical cognitive–affective mechanism linking social anxiety to PSU. PSU might function as a coping mechanism for some individuals to alleviate the negative emotion associated with social anxiety and IU.

1. Introduction

Since their invention, smartphones have been widely used around the world, to the point that daily life without them is difficult to imagine. Although smartphones make life more convenient by supporting such activities as online shopping, social communication, education, and entertainment [1], excessive use can result in negative consequences on general health, academic performance, and social connections [2].

Problematic forms of smartphone and Internet use are particularly prevalent among university students and the younger generation, where excessive use has negatively affected various aspects of student life [3,4,5]. For instance, among a large U.S. college student sample (n = 2469), 46.9% met criteria for problematic smartphone use (PSU) [6]. Moreover, PSU has been linked to a higher likelihood of traffic accidents resulting from distraction while driving [7], as well as greater incidence of cyberbullying and phubbing [8]. Beyond these behavioral risks, PSU has also shown strong associations with mental health problems, including general anxiety, depressive symptoms, and social anxiety [9,10,11,12]. Several factors have been suggested as contributing to the emergence of PSU. In the current study, we focus on the role of social anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty in association with PSU.

PSU is conceptualized as a problematic Internet use behavior, characterized by difficulties in regulating smartphone use, which lead to various physical, psychological, and social consequences. Similarly to substance use disorders, PSU involves symptoms such as withdrawal, emotional salience, and tolerance [13,14]. We provide the caveat, however, that PSU is not a disorder defined in DSM-5 or ICD-11, but PSU is nonetheless an important construct that is of concern in society.

An increasing number of studies has shown that social anxiety is strongly associated with PSU [11,15,16]. Social anxiety, or social phobia, refers to the excessive fear that individuals experience in social situations, often driven by apprehension about being observed, scrutinized, or negatively evaluated by others [17]. Because social anxiety is highly aversive, individuals often avoid social interactions to manage discomfort, avoid social missteps, and reduce their anxiety [18,19]. For socially anxious individuals, frequent smartphone use could serve as a habitual means of coping with anxiety, and smartphones and social networking sites may function as alternative means of social engagement [20,21]. Socially anxious individuals may excessively rely on online interaction via smartphones to reduce face-to-face apprehension [22,23]. However, this reliance increases the risk of developing PSU, particularly when individuals are unable to reduce or discontinue their use [24]. Moreover, smartphones may serve as an escape from social interaction, as individuals can turn to their screens during social situations, providing a distraction from the immediate context and a sense of control [19]. Research supports that college students with elevated social anxiety tend to rely on smartphones to cope with negative emotions stemming from interpersonal experiences [25,26]. Taken together, these findings highlight that social anxiety not only increases vulnerability to PSU but may also interact with cognitive factors—such as intolerance of uncertainty—that shape how individuals cope with social distress in the digital age [19].

Intolerance of uncertainty (IU) can be conceptualized as an individual’s tendency to react negatively to ambiguous situations [27]. IU is related to a broad variety of mental disorders like depressive disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and social anxiety disorder [28,29]. People with social anxiety frequently worry about how others will perceive their self-presentation and whether their behavior will be socially appropriate [30,31]. Moreover, social situations are inherently ambiguous, and outcomes cannot be predicted. Performing well in these contexts requires the ability to tolerate some uncertainty [32]. Research suggests that IU components related to difficulty taking action or avoiding uncertain situations are more strongly related to symptoms of social anxiety [29]. As a result, handling social situations is especially challenging for people with social anxiety, because they often have a strong tendency toward experiencing IU [19,33]. Furthermore, mobile phones can function as a maladaptive coping mechanism to alleviate the distress that stems from uncertainty [34]. Supporting this role, research on pre-service teachers (teachers in training) showed that IU indirectly influenced PSU through heightened rumination and anxiety, highlighting a chain of cognitive and emotional processes that exacerbate PSU risk [35]. In another study of graduate students, IU was associated with PSU severity both directly and indirectly by increasing anxiety and reducing positive coping strategies [36]. Taken together it seems that IU can serve as a mediator between social anxiety and PSU.

While prior studies have reported associations between social anxiety and PSU [15,16], the underlying mechanisms explaining how social anxiety contributes to PSU remain unclear. We were only able to find one study that examined the mediating role of IU between social anxiety and PSU [19]. Using correlational analysis and mediation testing, this study reported that individuals experiencing heightened social anxiety also tended to report greater IU, stronger desire to use phones to alleviate anxiety, and increased smartphone use [19]. However, these findings were limited to correlational and mediation methods, which do not capture the latent cognitive and affective mechanisms underlying these relationships. Moreover, IU has often been viewed mainly as a general feature of anxiety rather than a process that explains how socially anxious people develop problematic smartphone use [37,38].

To our knowledge, no previous study has investigated the mediating role of IU between social anxiety and PSU using latent variable-based structural equation modeling, which allows for a more rigorous investigation of the mediating role of IU and can provide stronger evidence for the mechanisms linking social anxiety to PSU. It should be noted that treating the variables as latent rather than observed leads to greater measurement accuracy and reduced error [39,40]. By addressing this gap, the current study provides a clearer picture of how social anxiety drives PSU through cognitive mechanisms such as IU.

Considering the previous research, our main hypotheses are:

H1.

IU is positively associated with PSU severity.

H2.

Social anxiety is positively associated with PSU severity.

H3.

IU mediates the relationship between social anxiety and PSU severity.

Theory

The Interaction of Person–Affect–Cognition–Execution (I-PACE) framework is commonly used to conceptualize PSU. According to the I-PACE model [41,42], maladaptive Internet use results from the intersection of individual traits (e.g., emotional reactivity, psychopathology), cognitive processes, affective states, and executive functioning. The I-PACE model also conceptualized these affective and cognitive processes as mechanisms through which predisposing psychopathology contributes to problematic Internet use such as PSU.

Within the framework of the I-PACE model [41,42], social anxiety can be conceptualized as a predisposing variable that heightens sensitivity to ambiguous or evaluative social situations, which are often perceived as threatening [43,44]. Individuals with high social anxiety often experience greater IU, perceiving social interactions as unpredictable and threatening [17,45]. IU can further function as a key cognitive–affective vulnerability linking social anxiety to PSU within the I-PACE framework, where situational triggers (e.g., social uncertainty) interact with predispositional psychopathology (social anxiety) and cognitive–affective factors (IU) leading to smartphone use as a coping mechanism that can ultimately reinforce PSU [19,34,41,46].

This conceptualization supports the view that IU functions as a mediating pathway connecting social anxiety to problematic smartphone engagement [19]. In line with this conceptualization, a study found that IU significantly correlated with PSU tendencies, and PSU may be a coping strategy to reduce negative emotions stemming from uncertainty [34]. Another study, reported that non-social smartphone use served as a mediator between IU and PSU severity, highlighting the role of IU in driving individuals toward using smartphones to cope with uncertainty [46].

2. Method

2.1. Sample and Procedures

The initial sample included 378 students from a mid-sized public university in the Midwestern United States. The data collection took place from 16 November 2023, to 12 April 2024. Following data screening in R [47], 43 participants were excluded due to careless responding (e.g., over 19 consecutive identical responses), replicated response IDs, and substantial missing data (e.g., >50% of survey responses). We also excluded six participants who did not possess a social media account, an exclusion criterion from the larger project from which we collected these data. The final analytic sample was consisted of 329 participants, aged 18–31 years (M = 19.99, SD = 2.14). The current sample size aligns with those reported in previous PSU research [48].

The sample demographics are summarized as follows: 63.8% reported being born female (n = 210), and 35.3% born male (n = 116). 14.3% identified as LGBTQ+ (n = 47). Regarding racial/ethnic background, 59.5% identified as White or Caucasian (n = 196), 26.4% Asian (n = 87), 14.3% African American (n = 47), and 9.7% Latinx (n = 32). These categories were not independent of each other.

An online cross-sectional design was used in the current study. Participants were recruited from the university’s Sona Systems research pool of introductory psychology students, and received course credit in the form of research participation points. After initial eligibility screening, participants were directed to an online consent form. The one who provided online consent completed the survey (in English) on the PsychData platform, which included demographic items, self-report measures, and debriefing materials.

2.2. Measures

Participants provided demographic information, including age, sex assigned at birth, sexual orientation, and race/ethnicity. Additionally, the following measures were used.

2.2.1. Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN)

The SPIN has 17 items and it assesses anxiety related to social performance and observation and was used to evaluate social anxiety symptom severity over the past month [49]. Responses are measured using a 5-point scale from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Extremely), producing a total score range of 0–68, with higher scores representing more severe symptoms. The SPIN has shown excellent internal consistency and good test–retest reliability as a valid measure of social anxiety severity [49,50]. Coefficient alpha for our sample was 0.93 and Omega was 0.95.

2.2.2. Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale-Short Version (IUS-12)

IUS-12 is a 12-item instrument that assesses the degree of intolerance of uncertainty, using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all characteristic of me) to 5 (entirely characteristic of me) [51]. The IUS-12 represents a shortened form of the original 27-item Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale [52]. Although the IUS-12 has two subscales/factors (prospective and inhibitory intolerance of uncertainty), researchers commonly use the total summed score [51]; in fact, a study found that a unidimensional factor was more parsimonious than the two-factor solution [53]. The IUS demonstrated good internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.91), and its validity has been established through correlations with other measures of depression and anxiety [51]. Coefficient alpha for our sample was 0.91 and Omega was 0.93.

2.2.3. Smartphone Addiction Scale-Short Version (SAS-SV)

The SAS-SV (version 4.3.3) [54] is a 10-item scale measuring PSU, with items rated on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). For consistency, we phrased items in the first person [55]. A composite score is computed, where higher values correspond to greater PSU. The SAS-SV has shown good reliability and validity [56]. In our sample, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87 and McDonald’s omega was 0.90.

2.3. Statistical Procedure

R software v.4.3.3 [47] was used for cleaning the data and conducting preliminary analysis. We employed several R packages v.4.3.3, including naniar (to examine missing data), pastecs (for descriptive statistics), careless (to identify inattentive responding), mice (for imputing missing data), dplyr (for data cleaning), fmsb (to assess internal consistency), skimr (for frequency tables), sjstats (for ANOVA effect sizes), and apaTables (to generate scale intercorrelations).

Following the mentioned data exclusions, missing item-level responses were estimated and imputed using maximum likelihood (ML) procedures separately for each scale prior to computing total and subscale scores. Item-level imputation was performed when fewer than 50% of responses were missing within a given scale. After computing scale scores, a second round of ML estimation was conducted at the scale level for participants who were missing fewer than 50% of their corresponding scores. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were then examined to evaluate normality assumptions, detect potential outliers, and guide the selection of covariates for subsequent analyses.

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM) were conducted with Mplus version 8.11 [57]. Measures used Likert-type response formats with verbal anchors for each option, involving five response options for the IUS-12 and SPIN (six response options for the SAS-SV), reflecting an ordinal rather than continuous response scale. Accordingly, items were treated as ordinal variables, and models were estimated with weighted least squares with mean and variance adjustment (WLSMV). This approach relies on a polychoric correlation matrix and estimates factor loadings via probit regression [58]. Given the ordinal scaling and estimation method, item-level normality indices are not reported, as such statistics are primarily relevant for continuous variables. Model fit was assessed using commonly accepted criteria for excellent fit (with acceptable fit in parentheses): Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) and Comparative Fit Index (CFI) values > 0.95 (0.90–0.94), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) values < 0.06 (0.07–0.08), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) values < 0.08 (0.09–0.10) [59]. However, RMSEA should be interpreted with caution, as its accuracy is reduced when applied to ordinal data [60], as conducted in this study.

For scaling purposes, the first unstandardized loading of each scale was fixed to 1. For the SAS-SV, residual error covariances were specified between items 1 and 2 (both reflecting missing school and/or work due to smartphone use) and between items 4 and 5 (both reflecting attachment to one’s smartphone) to account for their similar item content. For the SPIN, residual error covariances were specified between items 1 and 16 (both reflecting anxiety around authority figures), items 5 and 12 (both concerning fear of criticism), items 3 and 8 (both related to parties), and items 4 and 10 (both involving talking to strangers) to account for their overlapping content.

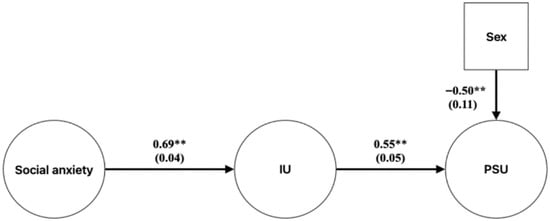

Following the CFAs, we estimated the SEM depicted in Figure 1, employing latent variables to represent our scales. In this model, social anxiety (predictor) was specified to predict IU (mediator), which then in turn was specified to predict PSU (dependent variable). We specified sex as a covariate of PSU [61]. Given the truncated age range of our college sample, we did not model age as a covariate. The mediation was assessed using the delta method for calculating indirect effect standard errors with the WLSMV estimator, using 1000 non-parametric bootstrapped replications.

Figure 1.

The mediating role of IU between social anxiety and PSU. PSU = problematic smartphone use; IU = intolerance of uncertainty. Path coefficients are presented, with their corresponding standard errors in parentheses. ** indicates p < 0.01.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations for age and the scale scores are shown in Table 1. All scale scores were significantly correlated with one another. Age was unrelated to scale scores, except for a significant association with PSU severity. Table 2 displays sex differences on the scale scores, showing that sex was significantly associated with all three scale scores, with women scoring higher than men; however, all three effects would be considered small in magnitude.

Table 1.

Correlations for age and scale scores.

Table 2.

Analyses of variance result for Sex differences in scale scores.

3.2. Individual CFA Results

Table 3 summarizes the CFA results for the three measures, with detailed factor loadings reported in Table A1, Table A2 and Table A3. Consistent with the previously outlined benchmarks, all three CFAs showed adequate to excellent fit, except for the RMSEA index, which, as noted previously, is not an appropriate indicator of model fit for ordinal items [60], such as those used in the present study.

Table 3.

Results of individual confirmatory factor analyses.

3.3. SEM Results

The SEM model, examining the mediating role of the IU factor in the relationship between social anxiety and PSU is presented in Figure 1. The model indicated good fit: robust χ2(732) = 1469.51, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.94, SRMR = 0.08, RMSEA = 0.05 (90% CI = 0.05–0.06). Figure 1 shows the model’s estimated path coefficients and standard errors. A significant association was found between social anxiety and IU; and IU was significantly related to PSU severity after adjusting for sex. Female sex also was significantly associated with PSU severity.

3.4. Mediation Analysis

Mediation analyses are summarized in Table 4, with p-values reported to indicate the significance of indirect effects. The path from social anxiety to PSU was significantly mediated by IU.

Table 4.

Standardized estimate for the indirect effect of IU in the relationship between social anxiety and PSU.

3.5. Model Comparison

To examine whether including an additional direct path between social anxiety to PSU would improve model fit above the model from Figure 1, we tested an alternative model in comparison to the original hypothesized model and compared the two models using a chi-square difference test using Mplus’s DIFFTEST command. The alternative model fit significantly better, χ2 diff (1) = 17.84, p < 0.001. However, while the original model’s CFI was 0.942, the alternative model’s CFI was only 0.005 points higher (CFI = 0.949). Given that a difference of at least 0.01 CFI units is required to suggest a substantial fit increase [62], results suggest that the magnitude of fit increase for the alternative model was nominal. Given the negligible difference and the stronger theoretical grounding of the original model, we retained the original model as the more parsimonious model.

4. Discussion

4.1. Overall Discussion

The present study examined whether IU mediates the relationship between social anxiety and PSU severity. Unlike prior research that has largely examined simple associations or relied on cross-sectional correlations, we used SEM to test the mediational pathway using latent constructs, providing a more rigorous analysis of underlying cognitive–affective mechanisms. Our findings supported the main hypotheses, indicating that people with higher levels of social anxiety tend to report greater IU, which in turn is associated with greater PSU severity. These results extend previous mediation studies by demonstrating that IU functions as a latent, mechanism-level mediator linking social anxiety to PSU, offering stronger evidence for the role of IU as a psychological vulnerability contributing to maladaptive technology use. Our study provides a clearer understanding of how individual cognitive–affective processes contribute to PSU.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies indicating that socially anxious people tend to experience higher levels of IU, which can drive maladaptive coping behaviors including excessive smartphone use, as an attempt for reducing these negative emotions and anxiety [25,34,36,63]. This view is consistent with Brown and Medcalf-Bell’s work, which reported that individuals with elevated social anxiety had greater IU, and stronger motives to use phones to decrease their anxiety, which in turn increased smartphone use [19].

From a theoretical standpoint, the findings reinforce the transdiagnostic role of IU in problematic behaviors [64]. The I-PACE model [41,42] suggests that predispositional factors such as social anxiety influence problematic Internet use through cognitive and affective mechanisms. Our study highlights IU as one such mechanism, providing empirical support for the model’s emphasis on individual differences and their impact on technology-related excessive behaviors. Socially anxious individuals often perceive social interactions as threatening and unpredictable, prompting them to rely on smartphone-based communication as a strategy to manage uncertainty [19]. While this behavior may provide short-term relief from uncertainty, it likely reinforces avoidance of face-to-face interaction and leads to dependence on the smartphone, thereby contributing to PSU [65,66].

Although we also examined an alternative model that included a direct path from social anxiety to PSU, the improvement in model fit was minimal. The difference in CFI between the two models was only 0.005, well below the 0.01 threshold typically used to indicate meaningful improvement [40,62]. Therefore, while the alternative model was statistically superior in a narrow sense, the theoretical value and parsimony of the original model remain stronger. As mentioned before, according to the I-PACE framework [41,42] predispositional factors like social anxiety may lead to PSU through cognitive–affective mechanisms, rather than being represented by only a single direct path. Keeping the mediation model aligns with prior research that identifies IU as a key process linking social anxiety to maladaptive smartphone use [19,34,64]. Therefore, keeping the original model of our study was more consistent with previous research and theory.

Our findings also carry important practical implications. Clinically, interventions that focus on reducing IU could help reduce PSU among socially anxious individuals. For instance, cognitive–behavioral strategies targeting IU could be used for socially anxious young adults, a group particularly vulnerable to PSU [64,67,68]. In educational settings, prevention programs could incorporate modules that teach students strategies for managing uncertainty in both offline and online contexts, fostering digital resilience and healthier technology use [69,70]. From a policy perspective, our findings support the development of guidelines that emphasize the early detection of at-risk individuals and promote evidence-based interventions targeting psychological vulnerabilities such as IU [64].

Our study emphasizes the importance of integrating psychological and behavioral mechanisms into personalized approaches to mental healthcare and digital well-being. Our findings contribute to the growing field of personalized and precision mental health by emphasizing the role of individual psychological mechanisms in maladaptive Internet use. Identifying IU as a key mediator between social anxiety and PSU severity highlights how specific cognitive–affective vulnerabilities may increase susceptibility to excessive or maladaptive engagement with digital technologies [41]. Such insights align with the principles of precision mental health, which aim to tailor prevention and intervention strategies based on individual cognitive and emotional profiles [71].

4.2. Limitations

Several limitations should be considered. First, because we used a cross-sectional design, causal conclusions cannot be drawn, and future longitudinal or experimental research is needed to confirm IU’s role as a mediator over time [72]. Second, reliance on self-report measures can lead to potential biases, including social desirability and shared method variance; therefore, objective assessments of smartphone use would provide more accurate and reliable data [73]. Third, this study focused specifically on IU as a mediator, whereas the I-PACE model emphasizes multiple interacting mechanisms [41]. Also, we did not analyze depression or general anxiety measures. Future studies should examine how IU interacts with other factors, such as emotion regulation difficulties, fear of missing out, or executive functions, to provide a more comprehensive account of PSU or other forms of Internet misuse [74,75,76]. The current sample consisted primarily of university students from a Midwestern USA State, thereby limiting the generalizability of the findings to wider populations. Future research should investigate these pathways across culturally diverse samples, as cultural norms surrounding uncertainty and technology use may shape both the expression of social anxiety and reliance on smartphones [77]. In particular, collectivist versus individualist orientations may influence the relationship between IU, social anxiety, and PSU, and future studies should examine these potential cultural moderators [78].

4.3. Conclusions

In conclusion, the current study demonstrates that IU serves as a mediator in the relationship between social anxiety and PSU, consistent with the I-PACE framework [41,42]. By identifying IU as a key mechanism, this research advances theoretical knowledge of PSU and highlights practical directions for interventions aimed at reducing both social anxiety and PSU.

Author Contributions

S.A.: Writing—original draft, Formal analysis. E.F.H.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing—review & editing. J.D.E.: Writing—original draft, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was not supported by any targeted grant from funding bodies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

IRB approval was received from the University of Toledo’s Social/Behavioral/Emotional IRB (Approval #301914) before the project was conducted. The approval date was 15 November 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Participants gave their consent through an informed consent form before taking part in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The de-identified data from this study are available for download and use, using the following link: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/sp3h5k27xk/1.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT v.5.1 for the purposes of English language editing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest pertaining to the current study. Beyond the scope of this paper, Elhai discloses that he receives royalties from several books on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), occasionally serves as a paid expert witness in PTSD-related legal cases, and has recently obtained research funding from the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Single-factor problematic smartphone use model: standardized estimates for factor loadings (top) and residual error covariances (bottom).

Table A1.

Single-factor problematic smartphone use model: standardized estimates for factor loadings (top) and residual error covariances (bottom).

| SAS-SV Item | Estimate | S.E. | Est./S.E. | Two-Tailed p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.56 | 0.04 | 13.10 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 0.65 | 0.04 | 18.31 | <0.001 |

| 3 | 0.59 | 0.04 | 14.72 | <0.001 |

| 4 | 0.66 | 0.03 | 20.83 | <0.001 |

| 5 | 0.84 | 0.02 | 37.51 | <0.001 |

| 6 | 0.86 | 0.02 | 46.02 | <0.001 |

| 7 | 0.74 | 0.03 | 26.40 | <0.001 |

| 8 | 0.74 | 0.03 | 25.20 | <0.001 |

| 9 | 0.64 | 0.03 | 19.25 | <0.001 |

| 10 | 0.64 | 0.04 | 17.57 | <0.001 |

| Estimate | S.E. | Est./S.E. | Two-Tailed p-Value | |

| Item 1 with 2 | 0.27 | 0.06 | 4.71 | <0.001 |

| Item 4 with 5 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 3.69 | <0.001 |

Note: SAS-SV = Smartphone Addiction Scale-Short Version; S.E. = Standard Error; Est./S.E. = Estimate divided by Standard Error.

Appendix B

Table A2.

Single-factor social anxiety model standardized estimates for factor loadings (top) and residual error covariances (bottom).

Table A2.

Single-factor social anxiety model standardized estimates for factor loadings (top) and residual error covariances (bottom).

| SPIN Item | Estimate | S.E. | Est./S.E. | Two-Tailed p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.58 | 0.04 | 13.57 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 0.63 | 0.04 | 16.51 | <0.001 |

| 3 | 0.79 | 0.03 | 30.51 | <0.001 |

| 4 | 0.74 | 0.03 | 25.55 | <0.001 |

| 5 | 0.74 | 0.03 | 26.82 | <0.001 |

| 6 | 0.84 | 0.02 | 40.48 | <0.001 |

| 7 | 0.72 | 0.03 | 23.48 | <0.001 |

| 8 | 0.64 | 0.04 | 17.57 | <0.001 |

| 9 | 0.76 | 0.03 | 28.79 | <0.001 |

| 10 | 0.79 | 0.02 | 33.49 | <0.001 |

| 11 | 0.69 | 0.03 | 20.99 | <0.001 |

| 12 | 0.73 | 0.03 | 23.74 | <0.001 |

| 13 | 0.73 | 0.04 | 21.11 | <0.001 |

| 14 | 0.87 | 0.02 | 52.19 | <0.001 |

| 15 | 0.82 | 0.02 | 42.36 | <0.001 |

| 16 | 0.72 | 0.04 | 20.03 | <0.001 |

| 17 | 0.77 | 0.03 | 26.11 | <0.001 |

| Estimate | S.E. | Est./S.E. | Two-Tailed p-Value | |

| Item 1 with 16 | 0.49 | 0.05 | 9.31 | <0.001 |

| Item 5 with 12 | 0.41 | 0.05 | 9.15 | <0.001 |

| Item 3 with 8 | 0.45 | 0.05 | 8.37 | <0.001 |

| Item 4 with 10 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 6.87 | <0.001 |

Note: SPIN = Social Phobia Inventory; S.E. = Standard Error; Est./S.E. = Estimate divided by Standard Error.

Appendix C

Table A3.

Single-factor intolerance of uncertainty model standardized estimates for factor loadings.

Table A3.

Single-factor intolerance of uncertainty model standardized estimates for factor loadings.

| IUS Item | Estimate | S.E. | Est./S.E. | Two-Tailed p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.72 | 0.03 | 24.43 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 0.66 | 0.03 | 19.93 | <0.001 |

| 3 | 0.78 | 0.03 | 31.72 | <0.001 |

| 4 | 0.69 | 0.03 | 24.01 | <0.001 |

| 5 | 0.78 | 0.02 | 33.01 | <0.001 |

| 6 | 0.82 | 0.02 | 35.20 | <0.001 |

| 7 | 0.82 | 0.02 | 39.13 | <0.001 |

| 8 | 0.64 | 0.04 | 18.24 | <0.001 |

| 9 | 0.73 | 0.03 | 23.45 | <0.001 |

| 10 | 0.72 | 0.03 | 24.03 | <0.001 |

| 11 | 0.63 | 0.03 | 18.74 | <0.001 |

| 12 | 0.75 | 0.03 | 28.29 | <0.001 |

Note: IUS = Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale-Short version; S.E. = Standard Error; Est./S.E. = Estimate divided by Standard Error.

References

- Shen, X.; Wang, J.-L. Loneliness and excessive smartphone use among Chinese college students: Moderated mediation effect of perceived stressed and motivation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 95, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albursan, I.S.; Al. Qudah, M.F.; Al-Barashdi, H.S.; Bakhiet, S.F.; Darandari, E.; Al-Asqah, S.S.; Hammad, H.I.; Al-Khadher, M.M.; Qara, S.; Al-Mutairy, S.H.; et al. Smartphone addiction among university students in light of the COVID-19 pandemic: Prevalence, relationship to academic procrastination, quality of life, gender and educational stage. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, L.; He, J.; Li, M.; Dai, J.; Zhou, Y.; Lai, F.; Zhu, G. Based on a decision tree model for exploring the risk factors of smartphone addiction among children and adolescents in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 652356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, A.; Nejad-Ebrahim Soumee, Z.; Tirgari Seraji, H.; Ramzi, F.; Saed, O. The self-control bridge: Connecting social media use to academic procrastination. Psychol. Rep. 2025, 00332941251330538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Fernandez, M.; Borda-Mas, M. Problematic smartphone use and specific problematic Internet uses among university students and associated predictive factors: A systematic review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 7111–7204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitta, A.S.L.; Oliveira, W.A.d.; Oliveira, L.G.d.; Silva, L.S.d.; Freires, É.M.; Semolini, F.F.; Baptista, M.N.; Romualdo, C.; Kim, H.S.; de Micheli, D.; et al. Examining the link between problematic smartphone use and substance use disorders among college students: Association patterns using network analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ajlouny, S.A.; Alzboon, K.K. Effects of mobile phone using on driving behavior and risk of traffic accidents. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 2023, 16, 100662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isrofin, B.; Munawaroh, E. The effect of smartphone addiction and self-control on phubbing behavior. J. Kaji. Bimbing. Dan Konseling 2024, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Yang, H.; Fang, J.; Bai, X.; Hall, B.J. Depression and anxiety symptoms are related to problematic smartphone use severity in Chinese young adults: Fear of missing out as a mediator. Addict. Behav. 2020, 101, 105962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Hu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, L.; Chen, J.; Xi, J.; Fang, J.; Zhang, S. Problematic smartphone usage and inadequate mental health literacy potentially increase the risks of depression, anxiety, and their comorbidity in Chinese college students: A longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2025, 20, 100907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Feng, B. Social anxiety and smartphone addiction among college students: The mediating role of loneliness. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1621900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alavinikoo, S.; Elhai, J.D.; Hutcheson, E.F.; Montag, C. Underlying dimensions of depression and negative affect are equally related to problematic smartphone and social media use severity. Psychiatry Res. 2025, 353, 116769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Servidio, R.; Koronczai, B.; Griffiths, M.D.; Demetrovics, Z. Problematic smartphone use and problematic social media use: The predictive role of self-construal and the mediating effect of fear missing out. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 814468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, C.H.; Chen, Y.Y. Smartphone addiction. In Adolescent Addiction; Essau, C.A., Delfabbro, P.H., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 215–240. [Google Scholar]

- Augner, C.; Vlasak, T.; Aichhorn, W.; Barth, A. The association between problematic smartphone use and symptoms of anxiety and depression—A meta-analysis. J. Public Health 2023, 45, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Cao, B.; Sun, Q. The association between problematic internet use and social anxiety within adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1275723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.S.; Heimberg, R.G. Social anxiety and social anxiety disorder. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 9, 249–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.R.; Kowalski, R.M. Social Anxiety; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.; Medcalf-Bell, R. Phoning it in: Social anxiety, intolerance of uncertainty, and anxiety reduction motivations predict phone use in social situations. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 2022, 6153053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Shen, X. Unveiling the relationship between social anxiety, loneliness, motivations, and problematic smartphone use: A network approach. Compr. Psychiatry 2024, 130, 152451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidin, S.H.; Midin, M.; Sidi, H.; Choy, C.L.; Nik Jaafar, N.R.; Mohd Salleh Sahimi, H.; Che Roos, N.A. The relationship between emotion regulation (ER) and problematic smartphone use (PSU): A system-atic review and meta-analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billieux, J.; Maurage, P.; Lopez-Fernandez, O.; Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Can disordered mobile phone use be considered a behavioral addiction? An update on current evidence and a comprehensive model for future research. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2015, 2, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enez Darcin, A.; Kose, S.; Noyan, C.O.; Nurmedov, S.; Yılmaz, O.; Dilbaz, N. Smartphone addiction and its relationship with social anxiety and loneliness. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2016, 35, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, G.; Feng, B. Social anxiety and smartphone addiction among college students: The mediating role of depressive symptoms. Curr. Psychol. 2025, 44, 882–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Wang, X.; Feng, T.; Xie, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Ren, L.; Liu, X. Network analysis of the association between social anxiety and problematic smartphone use in college students. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1508756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhai, J.D.; Gallinari, E.F.; Rozgonjuk, D.; Yang, H. Depression, anxiety and fear of missing out as correlates of social, non-social and problematic smartphone use. Addict. Behav. 2020, 105, 106335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladouceur, R.; Gosselin, P.; Dugas, M.J. Experimental manipulation of intolerance of uncertainty: A study of a theoretical model of worry. Behav. Res. Ther. 2000, 38, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N.; Mulvogue, M.K.; Thibodeau, M.A.; McCabe, R.E.; Antony, M.M.; Asmundson, G.J. Increasingly certain about uncertainty: Intolerance of uncertainty across anxiety and depression. J. Anxiety Disord. 2012, 26, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counsell, A.; Furtado, M.; Iorio, C.; Anand, L.; Canzonieri, A.; Fine, A.; Fotinos, K.; Epstein, I.; Katzman, M.A. Intolerance of uncertainty, social anxiety, and generalized anxiety: Differences by diagnosis and symptoms. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 252, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, K.; Davila, J.; Beck, J.G. Is social anxiety associated with both interpersonal avoidance and interpersonal dependence? Cogn. Ther. Res. 2005, 29, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalino, L.I.; Furr, R.M.; Bellis, F.A. A multilevel analysis of the self-presentation theory of social anxiety: Contextualized, dispositional, and interactive perspectives. J. Res. Personal. 2012, 46, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, P.; Wenseleers, T. Uncertainty about social interactions leads to the evolution of social heuristics. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, K.; Ünlü, S.; Arslan, G. Does intolerance of uncertainty influence social anxiety through rumination? A mediation model in emerging adults. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ren, L.; Li, K.; Yang, W.; Li, Y.; Rotaru, K.; Wei, X.; Yücel, M.; Albertella, L. Understanding the association between intolerance of uncertainty and problematic smartphone use: A network analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 917833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yong, S.; Tang, Y.; Feng, H.; Chen, L.; Zhang, L.; Deng, Y.; Chen, J. Intolerance of uncertainty fuels preservice teachers’ smartphone dependence through rumination and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Lu, H.; Wang, X.; Guo, Z.; Xing, C.; Zhang, Y. A moderated chain mediation model examining the relation between smartphone addiction and intolerance of uncertainty among master’s and PhD students. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelen, P.A.; Reijntjes, A. Intolerance of uncertainty and social anxiety. J. Anxiety Disord. 2009, 23, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEvoy, P.M.; Mahoney, A.E. To be sure, to be sure: Intolerance of uncertainty mediates symptoms of various anxiety disorders and depression. Behav. Ther. 2012, 43, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, M.; Young, K.S.; Laier, C.; Wölfling, K.; Potenza, M.N. Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific internet-use disorders: An interaction of person-affect-cognition-execution (I-PACE) model. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 71, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.; Wegmann, E.; Stark, R.; Müller, A.; Wölfling, K.; Robbins, T.W.; Potenza, M.N. The interaction of person-affect-cognition-execution (I-PACE) model for addictive behaviors: Update, generalization to addictive behaviors beyond internet-use disorders, and specification of the process character of addictive behaviors. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 104, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimberg, R.G.; Brozovich, F.A.; Rapee, R.M. A cognitive behavioral model of social anxiety disorder: Update and extension. In Social Anxiety; Hofmann, S.G., Dibartolo, P.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 395–422. [Google Scholar]

- Karvay, Y.; Imbriano, G.; Jin, J.; Mohanty, A.; Jarcho, J.M. They’re watching you: The impact of social evaluation and anxiety on threat-related perceptual decision-making. Psychol. Res. 2022, 86, 1174–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, Y.; Fracalanza, K.; Rector, N.A.; Laposa, J.M. Social anxiety and negative interpretations of positive social events: What role does intolerance of uncertainty play? J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 78, 2513–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozgonjuk, D.; Elhai, J.D.; Täht, K.; Vassil, K.; Levine, J.C.; Asmundson, G.J. Non-social smartphone use mediates the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and problematic smartphone use: Evidence from a repeated-measures study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 96, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Developement Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Developement Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Elhai, J.D.; Levine, J.C.; Hall, B.J. The relationship between anxiety symptom severity and problematic smartphone use: A review of the literature and conceptual frameworks. J. Anxiety Disord. 2019, 62, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.; Churchill, L.E.; Sherwood, A.; Weisler, R.H.; Foa, E. Psychometric properties of the social phobia inventory (SPIN): New self-rating scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 2000, 176, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antony, M.M.; Rowa, K.; Liss, A.; Swallow, S.R.; Swinson, R.P. Social comparison processes in social phobia. Behav. Ther. 2005, 36, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N.; Norton, M.P.J.; Asmundson, G.J. Fearing the unknown: A short version of the intolerance of uncertainty scale. J. Anxiety Disord. 2007, 21, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeston, M.H.; Rhéaume, J.; Letarte, H.; Dugas, M.J.; Ladouceur, R. Why do people worry? Personal. Individ. Differ. 1994, 17, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renjan, V.; McEvoy, P.M.; Handley, A.K.; Fursland, A. Stomaching uncertainty: Relationships among intolerance of uncertainty, eating disorder pathology, and comorbid emotional symptoms. J. Anxiety Disord. 2016, 41, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Kim, D.-J.; Cho, H.; Yang, S. The smartphone addiction scale: Development and validation of a short version for adolescents. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, É.; Montag, C. Smartphone addiction, daily interruptions and self-reported productivity. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2017, 6, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, B.; McCredie, M.; Fields, S. Examining the psychometric properties of the smartphone addiction scale and its short version for use with emerging adults in the US. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2020, 1, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B. Mplus User’s Guide: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables, User’s Guide; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst, B.; Neale, M.C. Best practices for binary and ordinal data analyses. Behav. Genet. 2021, 51, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Yang, Y. RMSEA, CFI, and TLI in structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: The story they tell depends on the estimation methods. Behav. Res. Methods 2019, 51, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Maydeu-Olivares, A.; Rosseel, Y. Assessing fit in ordinal factor analysis models: SRMR vs. RMSEA. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2020, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.A.; Sandra, D.A.; Veissière, S.P.; Langer, E.J. Sex, age, and smartphone addiction across 41 countries. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2025, 23, 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Huang, J. The relation between college students’ social anxiety and mobile phone addiction: The mediating role of regulatory emotional self-efficacy and subjective well-being. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 861527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N. Into the unknown: A review and synthesis of contemporary models involving uncertainty. J. Anxiety Disord. 2016, 39, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Levine, J.C.; Dvorak, R.D.; Hall, B.J. Fear of missing out, need for touch, anxiety and depression are related to problematic smartphone use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegmann, E.; Brand, M. Internet-communication disorder: It’s a matter of social aspects, coping, and internet-use expectancies. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraff, P.; Shikatani, B.; Rogic, A.M.; Dodig, E.F.; Talluri, S.; Murray-Latin, H. Intolerance of uncertainty and social anxiety: An experimental investigation. Behav. Change 2023, 40, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.L.; McGuire, J.F. Targeting intolerance of uncertainty in treatment: A meta-analysis of therapeutic effects, treatment moderators, and underlying mechanisms. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 341, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billieux, J.; Philippot, P.; Schmid, C.; Maurage, P.; De Mol, J.; Van der Linden, M. Is dysfunctional use of the mobile phone a behavioural addiction? Confronting symptom-based versus process-based approaches. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2015, 22, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Li, Y.; Kwok, S.Y.; Mu, W. The relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and problematic social media use during the COVID-19 pandemic: A serial mediation model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Insel, T.R. The NIMH research domain criteria (RDoC) project: Precision medicine for psychiatry. Am. J. Psychiatry 2014, 171, 395–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.E.; Cole, D.A. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Sapci, O.; Yang, H.; Amialchuk, A.; Rozgonjuk, D.; Montag, C. Objectively-measured and self-reported smartphone use in relation to surface learning, procrastination, academic productivity, and psychopathology symptoms in college students. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 3, 912–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Yang, H.; McKay, D.; Asmundson, G.J. COVID-19 anxiety symptoms associated with problematic smartphone use severity in Chinese adults. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolniewicz, C.A.; Tiamiyu, M.F.; Weeks, J.W.; Elhai, J.D. Problematic smartphone use and relations with negative affect, fear of missing out, and fear of negative and positive evaluation. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 262, 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavinikoo, S.; Pirmoradi, M.; Zahedi Tajrishi, K.; Arezoomandan, R. Structural equation modeling of problematic internet use based on executive function, interpersonal needs, fear of missing out and depression. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2025, 47, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.; Stevens, C.; Wong, S.H.; Yasui, M.; Chen, J.A. The prevalence and predictors of mental health diagnoses and suicide among US college students: Implications for addressing disparities in service use. Depress. Anxiety 2019, 36, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, H.-R. Values, intercultural sensitivity, and uncertainty management: A cross-cultural investigation of motivational profiles. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1623929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).