Safety and Efficacy of Prestige Coils for Embolization of Vascular Abnormalities: The Embo-Prestige Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

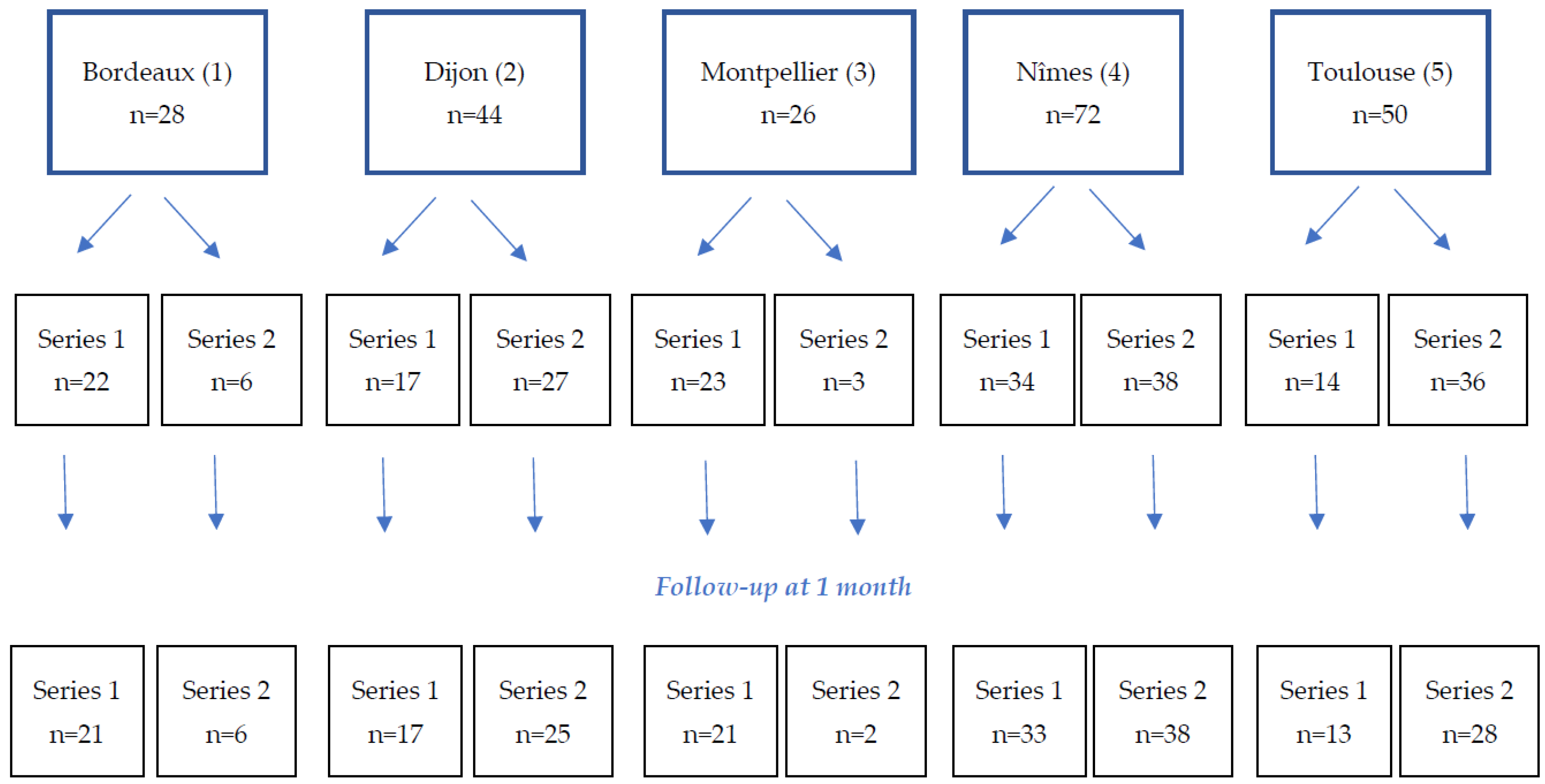

2.1. Study Design and Patients

2.2. Embolization Agents and Procedure

2.3. Follow-Up

2.4. Study Endpoints

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients

3.2. Embolization Data

3.3. Prestige Coils Characteristics

3.4. Immediate Efficacy

3.5. One-Month Efficacy

3.6. Safety

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eskridge, J.M.; Song, J.K. Endovascular embolization of 150 basilar tip aneurysms with Guglielmi detachable coils: Results of the Food and Drug Administration multicenter clinical trial. J. Neurosurg. 1998, 89, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, K.J.; Houdart, E.; Szopinski, K.T.; Levrier, O.; Guimaraens, L.; Kühne, D.; Solymosi, L.; Bartholdy, N.J.; Rüfenacht, D. Mechanical detachable platinum coil: Report of the European phase II clinical trial in 60 patients. Radiology 2001, 219, 541–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, G.E.; Szolar, D.H.; Karaic, R.; Stein, J.K.; Hausegger, K.A.; Schreyer, H.H. Extracranial aneurysm and arteriovenous fistula: Embolization with the Guglielmi detachable coil. Radiology 1996, 201, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdikakis, E.; Fezoulidis, I.; Tzortzis, V.; Rountas, C. Varicocele embolization: Anatomical variations of the left internal spermatic vein and endovascular treatment with different types of coils. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2018, 99, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molyneux, A.J.; Clarke, A.; Sneade, M.; Mehta, Z.; Coley, S.; Roy, D.; Kallmes, D.F.; Fox, A.J. Cerecyte coil trial: Angiographic outcomes of a prospective randomized trial comparing endovascular coiling of cerebral aneurysms with either cerecyte or bare platinum coils. Stroke 2012, 43, 2544–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDougall, C.G.; Johnston, S.C.; Gholkar, A.; Barnwell, S.L.; Vazquez Suarez, J.C.; Massó Romero, J.; Chaloupka, J.C.; Bonafe, A.; Wakhloo, A.K.; Tampieri, D.; et al. Bioactive versus bare platinum coils in the treatment of intracranial aneurysms: The MAPS (Matrix and Platinum Science) trial. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2014, 35, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemoto, S.; Iwama, J.; Mayanagi, Y.; Kirino, T. Coil Embolization of Cerebral Aneurysms. Experience with IDC and GDC. Interv. Neuroradiol. 1998, 4 (Suppl. S1), 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slob, M.J.; van Rooij, W.J.; Sluzewski, M. Coil thickness and packing of cerebral aneurysms: A comparative study of two types of coils. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2005, 26, 901–903. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- White, P.M.; Lewis, S.C.; Nahser, H.; Sellar, R.J.; Goddard, T.; Gholkar, A.; HELPS Trial Collaboration. HydroCoil Endovascular Aneurysm Occlusion and Packing Study (HELPS trial): Procedural safety and operator-assessed efficacy results. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2008, 29, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hongo, N.; Kiyosue, H.; Ota, S.; Nitta, N.; Koganemaru, M.; Inoue, M.; Nakatsuka, S.; Osuga, K.; Anai, H.; Yasumoto, T.; et al. Vessel Occlusion using Hydrogel-Coated versus Nonhydrogel Embolization Coils in Peripheral Arterial Applications: A Prospective, Multicenter, Randomized Trial. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2021, 32, 602–609.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taschner, C.A.; Chapot, R.; Costalat, V.; Machi, P.; Courthéoux, P.; Barreau, X.; Berge, J.; Pierot, L.; Kadziolka, K.; Jean, B.; et al. GREAT-a randomized controlled trial comparing HydroSoft/HydroFrame and bare platinum coils for endovascular aneurysm treatment: Procedural safety and core-lab-assessedangiographic results. Neuroradiology 2016, 58, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guglielmi, G.; Viñuela, F.; Dion, J.; Duckwiler, G. Electrothrombosis of saccular aneurysms via endovascular approach. Part 2: Preliminary clinical experience. J. Neurosurg. 1991, 75, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medical Advisory Secretariat. Coil embolization for intracranial aneurysms: An evidence-based analysis. Ont. Health Technol. Assess. Ser. 2006, 6, 1–114. [Google Scholar]

- Khalilzadeh, O.; Baerlocher, M.O.; Shyn, P.B.; Connolly, B.L.; Devane, A.M.; Morris, C.S.; Cohen, A.M.; Midia, M.; Thornton, R.H.; Gross, K.; et al. Proposal of a New Adverse Event Classification by the Society of Interventional Radiology Standards of Practice Committee. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2017, 28, 1432–1437.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Gregorio, M.A.; Bernal, R.; Ciampi-Dopazo, J.J.; Urbano, J.; Millera, A.; Guirola, J.A. Safety and Effectiveness of a New Electrical Detachable Microcoil for Embolization of Hemorrhoidal Disease, November 2020-December 2021: Results of a Prospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amouyal, G.; Tournier, L.; De Margerie-Mellon, C.; Pachev, A.; Assouline, J.; Bouda, D.; De Bazelaire, C.; Marques, F.; Le Strat, S.; Desgrandchamps, F.; et al. Safety Profile of Ambulatory Prostatic Artery Embolization after a Significant Learning Curve: Update on Adverse Events. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gremen, E.; Frandon, J.; Lateur, G.; Finas, M.; Rodière, M.; Horteur, C.; Benassayag, M.; Thony, F.; Pailhe, R.; Ghelfi, J. Safety and Efficacy of Embolization with Microspheres in Chronic Refractory Inflammatory Shoulder Pain: A Pilot Monocentric Study on 15 Patients. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Jiang, G.; Song, Z.; Cheng, W.; Wu, W.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Z.; You, W.; Chen, G. Efficacy and Safety of Different Bioactive Coils in Intracranial Aneurysm Interventional Treatment, a Systematic Review and Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, B.; Henrik, S.; Ioannis, T.; Veit, R.; Marios-Nikos, P. SMART coils for intracranial aneurysm repair - a single center experience. BMC Neurol. 2020, 20, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellamkonda, K.S.; Fereydooni, A.; Trott, K.; Lee, Y.; Mehra, S.; Nassiri, N. Superselective intranidal delivery of platinum-based high-density packing coils for treatment of arteriovenous malformations. J. Vasc. Surg. Cases Innov. Tech. 2021, 7, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greffier, J.; Dabli, D.; Kammoun, T.; Goupil, J.; Berny, L.; Touimi Benjelloun, G.; Beregi, J.P.; Frandon, J. Retrospective Analysis of Doses Delivered during Embolization Procedures over the Last 10 Years. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n (%) | Series 1 (n = 110) | Series 2 (n = 110) | Total (n = 220) | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age * | 64.5 (38.3–73.0) | 59.0 (34.0–71.8) | 62.5 (35.8–73) | 0.13 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 71 (64.5) | 78 (70.9) | 149 (67.7) | 0.31 |

| Female | 39 (35.5) | 32 (29.1) | 71 (32.3) | |

| Comorbidities | 0.011 | |||

| Diabetes | 13 (11.7) | 7 (6.4) | 20 (9.1) | |

| Arterial hypertension | 47 (42.3) | 31 (28.2) | 78 (35.5) | |

| Cirrhosis | 4 (3.6) | 2 (1.8) | 6 (2.7) | |

| Performance status | 0.14 | |||

| 0 | 50 (45.9) | 65 (59.6) | 115 (52.8) | |

| 1 | 37 (33.9) | 25 (22.9) | 62 (28.4) | |

| 2 | 14 (12.8) | 15 (13.8) | 29 (13.3) | |

| 3 | 3 (2.8) | 3 (2.8) | 6 (2.8) | |

| 4 | 5 (4.6) | 1 (0.9) | 6 (2.8) | |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Previous treatments | 0.006 | |||

| Anti-coagulant | 24 (21.6) | 11 (10.0) | 35 (15.9) | |

| Anti-platelet | 25 (22.5) | 16 (14.5) | 41 (18.6) |

| n (%) | Series 1 (n = 110) | Series 2 (n = 110) | Total (n = 220) | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk of the procedure | 0.16 | |||

| Low | 42 (38.2) | 36 (32.7) | 78 (35.5) | |

| Medium | 48 (43.6) | 42 (38.2) | 90 (40.9) | |

| High | 20 (18.2) | 32 (29.1) | 52 (23.6) | |

| Vascular anomaly | 0.08 | |||

| Arterial | 89 (80.9) | 78 (70.0) | 167 (75.9) | |

| Venous (variquous) | 20 (18.2) | 32 (29.1) | 52 (23.6) | |

| Other | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (0.05) | |

| Arterial anomalies | 0.21 | |||

| Aneurism | 21 (23.6) | 10 (14.3) | 31 (21.1) | |

| Faux aneurism | 18 (20.2) | 19 (27.1) | 37 (25.2) | |

| Bleeding | 29 (32.6) | 36 (51.4) | 65 (44.2) | |

| Arteriovenous fistula | 4 (4.5) | 3 (4.3) | 7 (4.8) | |

| Malformation | 5 (5.6) | 2 (2.9) | 7 (4.8) | |

| Missing | 12 | 8 | 19 | |

| Embolized artery | ||||

| Hepatic artery | 3 (3.5) | |||

| Splenic artery | 13 (15.1) | |||

| Superior mesenteric artery | 4 (4.7) | |||

| Inferior mesenteric artery | 4 (4.7) | NA | NA | |

| Left gastric artery | 1 (1.2) | |||

| Gastroduodenal artery | 5 (5.8) | |||

| Hypogastric artery | 13 (15.1) | |||

| Renal artery | 13 (15.1) | |||

| Other | 30 (34.9) | |||

| Missing | 3 | |||

| Embolized vein | ||||

| Spermatic vein | 16 (80.0) | |||

| Ovarian vein | 1 (5.0) | NA | NA | |

| Other | 3 (15.0) | |||

| Size of the vascular anomaly * | 6 (4–14) | 6 (5–10) | 6 (4–12) | 0.056 |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Size of the occluded vessel * | 4 (3–6) | 5 (3–6) | 5 (3–6) | 0.038 |

| n (%) | Series 1 (n = 110) | Series 2 (n = 110) | Total (n = 220) | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Embolization agent used | ||||

| Prestige coils | 110 (100) | 0 | 110 (50) | |

| Other coils | 16 (14.5) | 49 (44.5) | 65 (29.5) | |

| Liquid agent | 24 (21.8) | 50 (45.5) | 74 (33.6) | |

| Spongel | 6 (5.5) | 16 (14.5) | 22 (10.0) | |

| Microparticles | 3 (2.7) | 7 (6.4) | 10 (4.5) | |

| Plug | 3 (2.7) | 16 (14.5) | 19 (8.6) | |

| Number of coils used ** | 0.11 | |||

| 0–9 | 89 (80.9) | 45 (93.8) | 134 (84.8) | |

| 10–29 | 17 (15.5) | 3 (6.3) | 20 (12.7) | |

| 30–50 | 4 (3.6) | 0 | 4 (2.5) | |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Length of the first coil pushed ** | 0.4 | |||

| ≤15 cm | 63 (57.3) | 26 (54.2) | 89 (56.3) | |

| 15–30 cm | 27 (24.5) | 9 (18.8) | 36 (22.8) | |

| >30 cm | 20 (18.2) | 13 (27.1) | 33 (20.9) | |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Diameter of the first coil pushed ** | 0.31 | |||

| <6 mm | 65 (59.1) | 26 (55.3) | 91 (58.0) | |

| 6–10 mm | 27 (24.5) | 17 (36.2) | 44 (28.0) | |

| 11–20 mm | 13 (11.8) | 2 (4.3) | 15 (9.6) | |

| ≥20 mm | 5 (4.5) | 2 (4.3) | 7 (4.5) | |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Microcatheter size | <0.001 | |||

| ≤2.0 fr | 12 (11.2) | 5 (4.9) | 17 (8.1) | |

| 2.4 fr | 52 (48.6) | 18 (17.5) | 70 (33.3) | |

| ≥2.7 fr | 43 (40.2) | 80 (77.7) | 123 (58.6) | |

| Missing | 3 | 7 | 10 | |

| Scopy time * | 25 (16–39) | 17.5 (10–30) | 22 (13–37) | 0.015 |

| Missing | 2 | 10 | 12 | |

| Radiation dose * | 47,060 (23,637–115,621) | 34,385 (18,077–98,077) | 39,470 (19,550–107,878) | 0.26 |

| Missing | 3 | 10 | 10 |

| n (%) | Series 1 (n = 110) |

|---|---|

| Flexibility of the coil | |

| Very flexible | 61 (55.5) |

| Flexible | 49 (44.5) |

| Rigid | 0 |

| Very rigid | 0 |

| Pushability | |

| Very easy to push | 61 (55.5) |

| Easy to push | 47 (42.7) |

| Difficult to push | 2 (1.8) |

| Very difficult to push | 0 |

| Packing density | |

| Not dense at all | 2 (1.8) |

| A little dense | 17 (15.6) |

| Quite dense | 56 (51.4) |

| Very dense | 34 (31.2) |

| Missing | 1 |

| n (%) | Series 1 (n = 110) | Series 2 (n = 110) | Total (n = 220) | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct positioning of the coil/embolization agent | ||||

| Prestige coil | 110 (100) | NA | ||

| Other coils * | 15 (13.6) | 46 (41.8) | ||

| Liquid agent * | 24 (21.8) | 49 (44.5) | ||

| Spongel * | 6 (5.5) | 15 (13.6) | NA | |

| Microparticles * | 2 (1.8) | 7 (6.4) | ||

| Plug * | 3 (2.7) | 15 (13.6) | ||

| Complete occlusion of the target vessel | 106 (96.4) | 109 (99.1) | 215 (97.7) | 0.17 |

| Confidence of the radiologist in his/her procedure | 0.04 | |||

| Not very confident | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | |

| A bit confident | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (0.9) | |

| Confident | 53 (48.2) | 70 (63.6) | 123 (55.9) | |

| Very confident | 55 (50.0) | 39 (35.5) | 94 (42.7) |

| n (%) | Series 1 (n = 105) | Series 2 (n = 99) | Total (n = 204) | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lost to follow-up/missing | 5 | 11 | 16 | 0.12 |

| Improvement | 83 (79.0) | 74 (74.7) | 157 (77.0) | 0.99 |

| Steady state | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (1.0) | 0.97 |

| Back to baseline state | 16 (15.2) | 18 (18.2) | 34 (16.7) | 0.57 |

| Aggravation Incl death | 6 (5.7) 5 (4.8) | 6 (6.1) 5 (5.1) | 12 (5.9) 10 (5.4) | 0.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frandon, J.; Loffroy, R.; Marcelin, C.; Vernhet-Kovacsik, H.; Greffier, J.; Dabli, D.; Sammoud, S.; Marek, P.; Chevallier, O.; Beregi, J.-P.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Prestige Coils for Embolization of Vascular Abnormalities: The Embo-Prestige Study. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1464. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13101464

Frandon J, Loffroy R, Marcelin C, Vernhet-Kovacsik H, Greffier J, Dabli D, Sammoud S, Marek P, Chevallier O, Beregi J-P, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Prestige Coils for Embolization of Vascular Abnormalities: The Embo-Prestige Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2023; 13(10):1464. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13101464

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrandon, Julien, Romaric Loffroy, Clement Marcelin, Hélène Vernhet-Kovacsik, Joel Greffier, Djamel Dabli, Skander Sammoud, Pierre Marek, Olivier Chevallier, Jean-Paul Beregi, and et al. 2023. "Safety and Efficacy of Prestige Coils for Embolization of Vascular Abnormalities: The Embo-Prestige Study" Journal of Personalized Medicine 13, no. 10: 1464. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13101464

APA StyleFrandon, J., Loffroy, R., Marcelin, C., Vernhet-Kovacsik, H., Greffier, J., Dabli, D., Sammoud, S., Marek, P., Chevallier, O., Beregi, J.-P., & Rousseau, H. (2023). Safety and Efficacy of Prestige Coils for Embolization of Vascular Abnormalities: The Embo-Prestige Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 13(10), 1464. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13101464