Abstract

Background: In recent years, physical exercise has been investigated for its potential as a therapeutic tool in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) undergoing hemodialysis maintenance treatment (HD). It has been shown that regular practice of moderate-intensity exercise can improve certain aspects of immune function and exert anti-inflammatory effects, having been associated with low levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and high levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines. Purpose: The aim of this review is to examine the studies carried out in this population that analyzed the effect of intradialytic exercise on the inflammatory state and evaluate which exercise modality is most effective. Methods: The search was carried out in the MEDLINE, CINAHL Web of Science and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases from inception to June 2022. The PEDro scale was used to assess methodological quality, and the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool and MINORS were used to evaluate the risk of bias. The quality of evidence was assessed with GRADE scale. The outcome measures were systemic inflammation biomarkers. Results: Mixed results were found in terms of improving inflammation biomarkers, such as CRP, IL-6 or TNFα, after exercise. Aerobic exercise seems to improve systemic inflammation when performed at medium intensity while resistance training produced better outcomes when performed at high intensity. However, some studies reported no differences after exercise and these results should be taken with caution. Conclusions: The low quality of the evidence suggests that aerobic and resistance exercise during HD treatment improves systemic inflammation biomarkers in patients with ESRD. In any case, interventions that increase physical activity in patients with ESRD are of vital importance as sedentary behaviors are associated with mortality. More studies are needed to affirm solid conclusions and to make intervention parameters, such as modality, dose, intensity or duration, sufficiently clear.

1. Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is related to severe impairments of innate and adaptive immunity, resulting in a complex state of immune dysfunction in which signs of immune depression and activation paradoxically coexist [1,2]. Although functional immune cell imbalances susceptible CKD patients to infectious complications, persistent immune cell activation promotes a chronic inflammatory state that is related to an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Given that CVD and infections are the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in patients with CKD [3,4]. the immune dysfunction that accompanies CKD constitutes a major target for improving the outcomes of therapeutic interventions.

In recent years, the potential of physical exercise as a therapeutic tool in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) undergoing hemodialysis (HD) maintenance treatment has been investigated [5]. Regular practice of moderate-intensity exercise has been shown to improve certain aspects of immune function and exert anti-inflammatory effects [6,7], having been associated with low levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and high levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines [8]. These effects contribute, at least in part, to reducing the risk of infections and CVD [6,7]

The persistent inflammation and immune dysregulation present in CKD patients on HD can result in a loss of skeletal muscle mass, muscle strength and functional capacity. Exercise produces mechanical stress on the muscle fiber, which can alter the inflammatory response that affects structural and functional adaptation, remodeling and repairing processes in the skeletal muscles [9,10] On the other hand, physical activity can induce the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines and a selective decrease in circulating CD16 + monocytes through a transient increase in endogenous glucocorticoids [11]. In addition, exercise has been shown to decrease inflammation-dependent Toll-like receptors (TLRs), reducing cellular expression of TLR4 and consequently mitigating the inflammatory response induced by lipopolysaccharides [12].

Furthermore, it is very common for ESRD patients to have high levels of physical inactivity in their daily life, exacerbating chronic inflammation and loss of muscle mass and strength, which, associated with high cardiovascular morbidity, can create a vicious cycle in these patients [13].

In an attempt to clarify the state of the art on this topic, here, we conducted a systematic review of the literature to investigate the most effective exercise modality for reducing the inflammatory state of ESRD patients on HD, and, consequently, their cardiovascular morbidity and mortality while improving physical function and health-related quality of life.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a systematic review of studies researching the effect of exercise on inflammatory status in patients with ESRD on HD. PRISMA [14]. guidelines were followed during the design, search and reporting stages of this review. The protocol for this systematic review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42021288811).

2.1. Search Strategy

A literature search was conducted to identify all available studies on the effect of exercise on inflammatory status in ESRD patients on HD, with no publication date limit until September 2021 and no language limit, in the PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases. The PubMed search strategy was (“exercise”[MeSH Terms] OR “exercise”[All Fields] OR “exercises”[All Fields] OR “exercise therapy”[MeSH Terms] OR (“exercise”[All Fields] AND “therapy” [All Fields]) OR “exercise therapy”[All Fields] OR “exercise s”[All Fields] OR “exercised”[All Fields] OR “exerciser”[All Fields] OR “exercisers”[All Fields] OR “exercising”[All Fields]) AND (“inflammation”[MeSH Terms] OR “inflammation”[All Fields] OR “inflammations”[All Fields] OR “inflammation s”[All Fields]) AND (“haemodialysis”[All Fields] OR “renal dialysis”[MeSH Terms] OR (“renal”[All Fields] AND “dialysis”[All Fields]) OR “renal dialysis”[All Fields] OR “hemodialysis”[All Fields]). For other databases, the string was adjusted if necessary. We searched for additional records through other sources to supplement the database findings; for example, we hand-searched the reference lists of the relevant literature reviews and the indexes of peer-reviewed journals.

Five independent researchers (E.M.O., A.A.S., O.M.P., G.M.C. and A.Q.G.) conducted the searches and evaluated all the articles found by title and abstract and, subsequently, the full-text publications to determine their eligibility. This procedure was performed by each researcher involved in this part of the study (E.M.O., A.A.S., O.M.P., G.M.C. and A.Q.G.) and according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the research. A sixth author (E.A.S.R) resolved any discrepancies. The reference list of each article was screened to find any additional original articles.

2.2. Study Selection

2.2.1. Type of Studies

The types of studies included randomized controlled trials, non-randomized controlled trials, uncontrolled trials, non-randomized clinical trials, randomized crossover trials, and non-randomized crossover trials in ESRD patients on HD who underwent exercise intervention whose effect on inflammatory levels was evaluated, without restrictions regarding the date of publication. We excluded all repeated articles, case reports, letters to the editor, pilot studies, editorials, technical notes and review articles from the analysis. Articles written in any language were included.

2.2.2. Type of Participants

Participants in selected studies had to be adults (aged 18 years or older) with a diagnosis of ESRD and undergoing HD for at least 3 months.

2.2.3. Data Extraction

Five authors (E.M.O., A.A.S., O.M.P., G.M.C. and A.Q.G.) conducted the data extraction independently. A sixth author (E.A.S.R.) resolved any discrepancies. Reviewers were not blind to information regarding the authors, journal or outcomes for each article reviewed. A standardized form was used to extract data concerning study design, number and mean age of participants, the proportion of males/females, year and country of publication, setting, association of exercise with inflammatory levels, follow-up timing, clinical outcome measures and reported findings. Following the guidelines of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions—Version 5.1.0, the form was developed. It was pilot tested for reliability based on a representative sample of the studies to be screened.

2.2.4. Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of the clinical trials was assessed using the PEDro scale, reinforced by the use of the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for the evaluation of the risk of bias, in order to provide more detail in the evaluation.

The methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS) [15] was used to assess the methodological quality and risk of bias of the included studies. This scoring system includes eight items for non-randomized studies and four additional items for comparative studies. Each item is scored between 0 and 2, and the maximum attainable score is 16 and 24 for non-randomized and comparative studies, respectively. Five authors independently answered questions with 0 (not reported), 1 (reported but inadequate) or 2 (reported and adequate); any disagreements were resolved through discussion and, if no consensus was reached, another review author was consulted and a decision made.

2.2.5. Certainty of Evidence

The certainty of the evidence analysis was established by different levels of evidence according to the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework, which is based on five domains: study design, imprecision, indirectness, inconsistency and publication bias [16]. The evidence was classified into the following four levels: high quality (all five domains are satisfied), moderate quality (one of the five domains are not satisfied), low quality (two of the five domains are not satisfied) or very low quality (three of five domains are not satisfied) [17].

For the risk of bias domain, recommendations were downgraded one level if there was unclear or high risk of bias and severe limitations in the estimation effect. For consistency, recommendations were downgraded when point estimates varied widely among studies, confidence intervals overlapped or when the I2 test was substantial (>50%). For the indirectness domain, when serious differences in interventions, populations or outcomes were found, they were downgraded by one level. For the imprecision domain, if there were fewer than 300 participants for key outcomes, it was downgraded one level. Finally, if a strong influence of publication bias was detected, one level was downgraded [18].

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

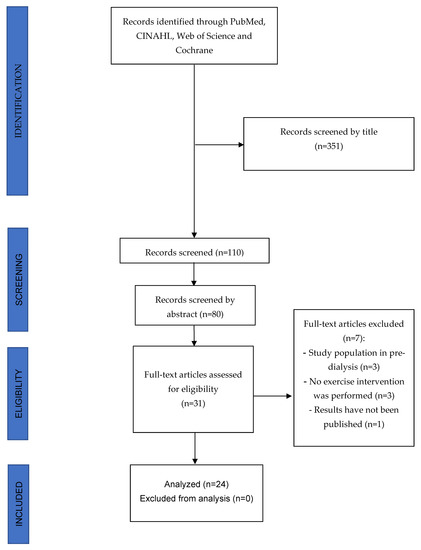

A total of 351 studies were detected and analyzed by performing the proposed searches in the detailed databases. After removing duplicates and analyzing the titles and abstracts of the remaining articles, 31 full-text articles were evaluated for possible inclusion in the present study. Finally, 9 of these manuscripts were excluded because they were not carried out in patients with ESRD on HD because they did not perform an exercise program as an intervention or because their results had not yet been published. Therefore, 24 studies were ultimately selected for this review (see Figure 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow diagram.

The 24 studies included were conducted in Iran [19], Brazil [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29], Poland [30], the United Kingdom [31,32,33,34,35,36], Taiwan [37], China [38], Indonesia [39], Spain [40,41] and Greece [42], and published from 2010 to 2022.

3.2. Study Characteristics

The characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1. The 24 studies were clinical trials, of which thirteen were randomized controlled trials [19,25,26,27,28,29,35,36,37,38,39,41,42], four were uncontrolled trials [20,21,30,40], one was a non-randomized clinical trial [23], one was a non-randomized controlled trial [32], four were randomized crossover trials [22,24,31,33], and one was a non-randomized crossover trial [34].

Table 1.

The effect of exercise on inflammation in HD patients.

3.3. Methodological Quality and Risk of Bias of the Included Studies

The methodological quality of the studies was evaluated with the PEDro scale, and scores are shown in Table 2. In total, seventeen studies were evaluated as being of excellent quality [19,22,24,25,26,27,28,31,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,41,42], two studies were of good quality [23,29] and five studies were of acceptable quality [20,21,30,32,40].

Table 2.

Methodological quality evaluation of the clinical trials using the PEDro Scale for assessing the risk of bias in randomized and non-randomized trials.

The risk of bias of the randomized controlled trials was evaluated with the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool, and scores are shown in Table 3. In total, seventeen studies were evaluated. Five studies were at low risk of bias [26,28,31,37,39], five studies had an unclear risk [25,35,36,41,42] and seven studies were at high risk of bias [19,22,24,27,29,33,38].

Table 3.

Methodological quality evaluation of the clinical trials using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for assessing the risk of bias in randomized trials.

For non-randomized controlled trials, the MINORS scale was used, and scores are shown in Table 4. In total, seven studies were evaluated. Six studies scored above 12/24 points and showed good quality [21,23,30,32,34,40], and only one study scored below 12/24 points with fair quality [20].

Table 4.

Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS) to assess the methodological quality and risk of bias of the included observational studies. Items are scored 0 (not reported), 1 (reported but inadequate) or 2 (reported and adequate), with the global ideal score being 16 for non-comparative studies and 24 for comparative studies.

3.4. Quality of Evidence

Quality of evidence of AE and RT was assessed with the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework, and results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of findings for clinical trials, including the GRADE quality of evidence assessment.

The low quality of the evidence supports the use of AE and RT exercises in patients with ESRD to improve biomarkers of systemic inflammation.

3.5. Data from Studies

The most relevant results obtained in the studies included in the review are mentioned below:

3.5.1. Effect of Exercise on Main Inflammatory Biomarkers

C-Reactive Protein

Fourteen studies analyzed the effects of exercise on CRP levels with different results. One study did not find differences in CRP levels after AE [30] and two studies did not find differences after RT [23,40]. Additionally, one study found no differences when AE were compared to RT [39] or when compared to usual care [24,27,32,35]. On the other hand, two studies found decreased levels of CRP after AE compared to usual care [33,37], one study found improvements favoring AE when compared to RT [19] and two studies found improvements after RT exercise [20,21]. Finally, when AE were combined with RT, one study reported decreased levels after intervention [41].

IL-6

Twelve studies analyzed the effects of exercise on IL-6 levels with different results. One study did not find differences in IL-6 after AE [30] and three studies did not find differences after RT [20,21,28]. Additionally, no changes were found when comparing AE and RT in IL-6 levels [26] or when compared to usual care [31,32,35,36]. On the other hand, two studies found decreased levels of IL-6 after AE compared to usual care [25,37]. Lastly, when AE were combined with RT, IL-6 levels were decreased after intervention [41].

TNFα

Twelve studies analyzed the effects of exercise on TNFα levels with different results. Three studies found no changes after AE [30] and three studies found no differences after RT [20,21,28]. No significant changes were reported when AE was compared to usual care in terms of TNFα improvements [31,32,35,36]. However, two studies found reduced TNFα levels after AE compared to usual care [25,33] and two studies reported decreased TNFα levels after RT compared to usual care [29,38].

3.5.2. Effect of Exercise on Other Inflammatory Biomarkers

Other biomarkers less studied were IL-10, IL-1β, IL-17a, IL-8, IL-1ra, IFN-γ, ROS and SOD.

Five studies analyzed the effects of exercise on IL-10, two of them reporting increases after AE [22,25] and another one reporting no changes after RT [28]. Likewise, AE compared to the control did not improve IL-10 levels [35,36].

Two studies evaluated IL-1β levels after AE, with one study reporting reduced levels of IL-1β after AE [25] and another one not finding any differences [30].

One study found decreased levels of IL-17a during HD, but it increases after HD in patients who did not performed exercise [22]. However, another study found no significant differences when AE was compared to usual care improving IL-17a [36].

Other studies analyzed exercise on biomarkers IL-8 and IFN-γ, reporting decreased levels of IL-8 after AE [25], as well as decreased levels of IFN-γ after AE [22].

Two studies evaluated IL-1ra levels after AE, reporting no changes after AE [30,31].

Finally, one study found increased ROS levels after AE and at 60 min (but no later), suggesting a transient pro-inflammatory event [34]. On the other hand, RT reduced antioxidant enzymes after exercise, but increased on the day after exercise [23].

4. Discussion

The main objective of this systematic review was to synthesize the evidence of the effects of exercise on inflammatory mediators in patients with CKD at ESRD and HD. The different exercise approaches analyzed were the following: aerobic exercise and resistance training. The main inflammatory mediators analyzed were CPR, TNFα and IL-6, which are highly predictive of mortality in these patients, therefore, they were our focus on the present review [43].

4.1. Aerobic Exercise

Thirteen studies analyzed the effects of AE in CKD patients undergoing HD, with a total of 351 patients analyzed [22,24,25,27,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,42]. Most studies had excellent methodological quality, although the risk of bias ranged from high to low, with many studies scoring a high risk of bias and only two studies presenting a low risk of bias [31,37]. All of them used the cycloergometer as aerobic training with a total exercise duration from 30 to 60 min. Most studies performed at medium intensity (12–15 RPE).

Regarding the effectiveness of AE on inflammatory mediators, mixed evidence is found. With respect to IL-6, Liao et al., and Gonçalves da Cruz et al., found decreased IL-6 after 36 sessions of AE at medium intensity [25,37]. In contrast, Dungey et al., found no differences in inflammatory mediators after fewer sessions of AE [31]. However, other studies with longer training periods also found no differences [30,32,35,36].

The same scenario occurs in relation to CPR and TNFα, with studies reporting decreased levels after AE [37,42], and others without differences [24,27,35].

Other less investigated mediators such as IL-17a, IFNγ or IL-1ra seem to be unaffected by AE [22,31,36], while others such as IL-10 seem to increase after AE [22,25]. Finally, one study found that acute AE increased ROS (Reactive Oxygen Species), suggesting a proinflammatory response after acute exercise [34]. However, these results should be taken with caution due to the low sample size and small number of studies.

There is no clear evidence that AE reduce inflammatory mediators associated with CKD, such as IL-6, TNFα or CRP. Regarding the effectiveness of AE on other inflammatory conditions, such as COVID-19, a recent review found that aerobic training at medium intensity, from approximately 20 to 60 min and performed three times per week, improves inflammatory mediators [44]. We suggest that exercise intensity could be a parameter that could explain these differences found in patients with CKD and ESRD, as high intensity training can increase IL-6 levels compared to medium intensity training [45]. The implementation of future long-term and medium-intensity based training programs could shed light on whether AE can reduce inflammatory mediators.

4.2. Resistance Exercise

Seven studies analyzed the effects of RT in CKD patients undergoing HD, with a total of 316 patients analyzed [20,21,23,28,29,38,40]. Methodological quality was from acceptable to excellent, and the risk of bias was from low to high, with only one study with a low risk of bias [28]. Most studies used lower limb strengthening programs, although some added upper limbs as well [29,40]. Four studies did not specify exercise intensity, while others worked from 60 to 70% 1RM or high intensity training (>15 RPE).

Regarding the effectiveness of RT on the aforementioned inflammatory mediators, again, mixed results are found.

With respect to IL-6, none of the analyzed studies reported changes in IL-6 when RT was performed, all including long-term (36–72 weeks) moderate–high intensity training [20,21,28,38]. In comparison, healthy adults who performed RT had significant decreases in IL-6 after RT [46]. In addition, Gadelha et al., found that CKD patients performing RT showed a decrease in IL-6 levels after 24 weeks of moderate-intensity training [47]. Differences with our results might be associated with training intensity as well as training programs because Gadelha et al., performed whole-body exercises.

With reference to CRP, three studies found decreases after RT and two did not. Moraes et al., found decreases in CRP after RT at 70% 1RM (20), while Dong et al., found the same results after high intensity RT (>15 RPE) [38]. However, among studies that did not find differences, two of them did not report exercise intensity and the other one performed at medium intensity [23]. This is in line with a recent published meta-analysis that found that RT had larger effect sizes improving CRP when it was performed at vigorous intensity [46].

The same results are found when evaluating TNFα. Three studies found no differences while another two studies found decreases after RT [20,21,28,38]. The studies that reported no differences were performed at high intensity and for long periods of time, but those that found differences also did so, suggesting that intensity may not be a key factor in decreasing TNFα. Studies suggest that specific populations (such as heart failure) may benefit more from RT than others [46].

Other mediators such as VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and oxidative stress mediators were reduced after RT [21,23]. Two studies found no differences in IL-10 after RT, while one study found increases afterwards, although results should be taken with caution due to low sample sizes [28,29,38].

We found clear evidence of a reduction in CRP in patients with CKD who performed high-intensity RT. However, we found no changes in IL-6 levels after long periods of RT and mixed evidence in terms of TNFα. Although high intensity training suggests better results for decreasing inflammatory mediators, future studies are required.

4.3. Compared and Combined Interventions

Two studies compared AE vs. RT in CKD patients undergoing HD, with a total of 58 patients analyzed [19,26]. All studies had excellent methodological quality and risk of bias ranging from low to high, with only one study presenting a low risk of bias [26].

Afsar et al., found that both interventions reduced CRP compared to the baseline, but with better results in favor of AE [19]. In terms of Il-6, Figueredo et al., reported slight improvements in IL-6 but without differences between groups [26].

Two studies combined AE with RT in CKD patients undergoing HD, with a total of 191 patients analyzed [39,41]. All studies had excellent methodological quality and risk of bias ranging from unclear to low, with only one study presenting a low risk of bias [41].

Regarding CRP, Suhardjono et al., found no differences when AE was combined with RT in terms of CRP decrease [39], while Meléndez et al., found decreases in CRP levels after intervention [41]. With respect to IL-6, combined exercise reduced IL-6 levels [41].

Strategies that combine AE with RT may exert better outcomes than both modalities alone. In line with these findings, Sadjapong et al., found that elderly patients with chronic inflammation who performed AE at medium intensity and RT at high intensity improved their levels of IL-6 and CRP more than a control group receiving usual care [47]. Our results show similar effects, with a greater improvement in IL-6 after AE and improvements in CRP after RT, so that combining both exercises could be more beneficial than performing them separately. However, the limited number of studies makes it difficult to draw strong conclusions. Future studies should evaluate the efficacy of a combined intervention in CKD patients with ESRD under HD.

4.4. Future Directions

Although more studies are still needed to analyze the effects of exercise on inflammatory levels in patients with ESRD on HD, it is well-demonstrated in this review that exercise has a beneficial effect by decreasing different inflammatory cytokines and improving oxidative stress in this population. However, it is not clear which is superior.

It seems that medium-intensity training produces better results in patients who perform AE and high intensity training in patients who perform RT, hence, adjusting the intensity of training is a key point for these patients. In addition, acute exercise can increase some proinflammatory mediators so longer periods of training may be beneficial in developing long-term anti-inflammation adaptation [7]. Combining both trainings might be a better strategy than performing them separately, but again, intensity must be regulated. Regular AE may promote an anti-inflammatory environment, decreasing proinflammatory mediators and RT, in addition to favoring the same environment and improving muscular mass and functional capacity [48].

Finally, CKD is a multifactorial disease and must be approached in a multidisciplinary way. Sarcopenia is commonly found in CKD patients, and it is associated with disease progression and mortality. Combining strategies such as exercise and nutritional advice are highly recommended. For example, patients with CKD who underwent RT and a nutritionist-supervised diet showed decreases in IL-6, emphasizing the importance of nutrition in these patients [49]. Adding nutritional behavioral changes (such as increasing protein intake) to exercise programs could help clinicians to slow down sarcopenia in CKD patients, although more studies are needed [50].

4.5. Limitations

Due to the great heterogeneity of the included studies, no meta-analysis of the results has been carried out, which should be considered as a limitation of the study. However, the systematic review carried out amply responds to the stated objectives.

Regardless of the exercise intervention, it should be noted that most of the included studies had a high risk of bias, with allocation concealment and blinding of participants/therapist being the lowest scoring items. In contrast, the methodological quality of included studies was good to excellent in most of them.

5. Conclusions

Some studies have shown the positive effect of exercise in reducing the inflammatory state of HD patients, achieving better benefits with long-duration programs with an intensity >15 on the scale of perceived exertion (RPE).

However, other studies were presented in which exercise had no effect on these parameters, which calls for caution in drawing strong conclusions to avoid overestimating its effect.

In any case, interventions that increase physical activity in patients with ESRD are of vital importance as sedentary behaviors are associated with mortality. The low quality of evidence supports the inclusion of exercise programs in patients with ESRD undergoing HD; although, more studies are needed to affirm solid conclusions and make intervention parameters such as modality, dose, intensity, or duration sufficiently clear.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M.O., J.H.V. and E.A.S.R.; methodology, J.H.V. and E.A.S.R.; software, J.H.V.; validation, all authors; formal analysis, E.M.O., E.A.S.R. and J.H.V.; investigation, all authors; resources, J.L.A.P.; data curation, E.M.O., E.A.S.R. and J.H.V.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M.O., E.A.S.R., J.L.A.P., A.A.S., G.M.C., A.Q.G., S.T. and J.H.V.; writing—review and editing, E.A.S.R., E.M.O., S.T., N.V.I., O.M.-P. and J.H.V.; visualization E.M.O., E.A.S.R. and J.H.V.; supervision, all authors; project administration J.H.V. and E.A.S.R.; funding acquisition, J.L.A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The publication of this work has been financed by the European University of Canary Islands, C/Inocencio García 1 38300 La Orotava, Tenerife, 38300 Canary Islands, Spain.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health-Ricerca Corrente 2021.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors certify that they have no affiliations with or financial involvement in any organization or entity with a direct financial interest in the subject matter or materials dis-cussed in the article.

References

- Stenvinkel, P. Chronic kidney disease: A public health priority and harbinger of premature cardiovascular disease. J. Intern. Med. 2010, 268, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eleftheriadis, T.; Antoniadi, G.; Liakopoulos, V.; Kartsios, C.; Stefanidis, I. Basic science and dialysis: Disturbances of acquired immunity in hemodialysis patients. In Seminars in Dialysis; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2007; Volume 20, pp. 440–451. [Google Scholar]

- Dalrymple, L.S.; Go, A.S. Epidemiology of acute infections among patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 3, 1487–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naqvi, S.B.; Collins, A.J. Infectious complications in chronic kidney disease. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2006, 13, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura-Ortí, E. Ejercicio en pacientes en hemodiálisis: Revisión sistemática de la literatura. Nefrología 2010, 30, 236–246. [Google Scholar]

- Nieman, D.C. Moderate exercise improves immunity and decreases illness rates. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2011, 5, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, M.; Bishop, N.C.; Stensel, D.J.; Lindley, M.R.; Mastana, S.S.; Nimmo, M.A. The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: Mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, A.M.W.; Pedersen, B.K. The anti-inflammatory effect of exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 98, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiter, T.; Hoene, M.; Prenzler, F.; Mooren, F.C.; Steinacker, J.M.; Weigert, C.; Niess, A.M.; Munz, B. Exercise, skeletal muscle and inflammation: ARE-binding proteins as key regulators in inflammatory and adaptive networks. Exerc. Immunol. Rev. 2015, 21, 42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Pillastrini, P.; Ferrari, S.; Rattin, S.; Cupello, A.; Villafañe, J.H.; Vanti, C. Exercise and tropism of the multifidus muscle in low back pain: A short review. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 943–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmerman, K.L.; Flynn, M.G.; Coen, P.M.; Markofski, M.M.; Pence, B.D. Exercise training-induced lowering of inflammatory (CD14 CD16) monocytes: A role in the anti-inflammatory influence of exercise? J. Leukoc Biol. 2008, 84, 1271–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlin, B.K.; Flynn, M.G.; Campbell, W.W.; Stewart, L.K.; Timmerman, K.L. TLR4 is lower in resistance-trained older women and related to inflammatory cytokines. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2004, 36, 1876–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrero, J.J.; Stenvinkel, P.; Cuppari, L.; Ikizler, T.A.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Kaysen, G.; Mitch, W.E.; Price, S.R.; Wanner, C.; Wang, A.Y.; et al. Etiology of the protein-energy wasting syndrome in chronic kidney disease: A consensus statement from the international society of renal nutrition and metabolism (ISRNM). J. Ren. Nutr. 2013, 23, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015, 349, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slim, K.; Nini, E.; Forestier, D.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Panis, Y.; Chipponi, J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J. GRADE Working Group GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, J.; Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A.D.; Alderson, P.; Dahm, P.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Nasser, M.; Meerpohl, J.; Post, P.N.; Kunz, R.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 14. Going from evidence to recommendations: The significance and presentation of recommendations. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013, 66, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca-Martínez, F.; Suso-Martí, L.; Herranz-Gómez, A.; Varangot-Reille, C.; Calatayud, J.; Romero-Palau, M.; Blanco-Díaz, M.; Salar-Andreu, C.; Casaña, J. Effectiveness of Telematic Behavioral Techniques to Manage Anxiety, Stress and Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, R.; Shegarfy, L.; Shavandi, N.; Sanavi, S. Effects of aerobic exercise and resistance training on lipid profiles and inflammation status in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Indian J. Nephrol. 2010, 20, 185–189. [Google Scholar]

- Moraes, C.; Stockler-Pinto, M.B.; Lobo, J.C.; Barros, A.F.; Wady, M.T.; Seguins, W.S.; Bessa, B.; Fouque, D.; Mafra, D. Resistance exercise program: Intervention to reduce inflammation and improve nutritional status in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2012, 31, A16–A96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moraes, C.; Marinho, S.M.; Da Nobrega, A.C.; de Oliveira Bessa, B.; Jacobson, L.V.; Stockler-Pinto, M.B.; Da Silva, W.S.; Mafra, D. Resistance exercise: A strategy to attenuate inflammation and protein-energy wasting in hemodialysis patients? Int. Urol Nephrol. 2014, 46, 1655–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, A.; Perotto, D.L.; Dorneles, G.P.; Fuhro, M.I.S.; Monteiro, M.B. Effects of intradialytic exercise on systemic cytokine in patients with chronic kidney disease. Ren. Fail. 2015, 37, 1430–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esgalhado, M.; Stockler-Pinto, M.B.; de França Cardozo, L.F.M.; Costa, C.; Barboza, J.E.; Mafra, D. Effect of acute intradialytic strength physical exercise on oxidative stress and inflammation responses in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2015, 34, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Fuhro, M.I.; Dorneles, G.P.; Andrade, F.P.; Romão, P.R.; Peres, A.; Monteiro, M.B. Acute exercise during Hemodialysis prevents the decrease in natural killer cells in patients with chronic kidney disease: A pilot study. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2017, 50, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, L.G.D.; Zanetti, H.R.; Andaki, A.C.R.; Mota, G.R.D.; Barbosa Neto, O.; Mendes, E.L. Intradialytic aerobic training improves inflammatory markers in patients with chronic kidney disease: A randomized clinical trial. Mot. Rev. Educ. Física 2018, 24, e017517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Figueiredo, P.H.S.; Lima, M.M.O.; Costa, H.S.; Martins, J.B.; Flecha, O.D.; Gonçalves, P.F.; Alves, F.L.; Rodrigues, V.G.B.; Maciel, E.H.B.; Mendonça, V.A.; et al. Effects of the inspiratory muscle training and aerobic training on respiratory and functional parameters, inflammatory biomarkers, redox status and quality of life in hemodialysis patients: A randomized clinical trial. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- e Silva, V.R.O.; Belik, F.S.; Hueb, J.C.; de Souza Gonçalves, R.; Caramori, J.C.T.; Vogt, B.P.; Barretti, P.; Bazan, S.G.Z.; De Stefano, G.M.M.F.; Martin, L.C.; et al. Aerobic Exercise Training and Nontradicional Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Hemodialysis Patients: Results from a Prospective Randomized Trial. Cardiorenal Med. 2019, 9, 391–399. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, L.C.C.; Mota, J.F.; Prestes, J.; Schincaglia, R.M.; Silva, D.M.; Queiroz, N.P.; de Souza Freitas, A.T.V.; Lira, F.S.; Peixoto, M.D.R.G. Intradialytic Resistance Training Improves Functional Capacity and Lean Mass Gain Individuals on Hemodialysis: A Randomized Pilot Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 100, 2151–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, H.L.; Moura, S.R.G.; Neves, R.V.P.; Tzanno-Martins, C.; Souza, M.K.; Haro, A.S.; Costa, F.; Silva, J.A.B.; Stone, W.; Honorato, F.S. Resistance training improves sleep quality, redox balance and inflammatory profile in maintenance hemodialysis patients: A randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołȩbiowski, T.; Kusztal, M.; Weyde, W.; Dziubek, W.; Woźniewski, M.; Madziarska, K.; Krajewska, M.; Letachowicz, K.; Strempska, B.; Klinger, M. A Program of physical rehabilitation during hemodialysis sessions improves the fitness of dialysis patients. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2012, 35, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dungey, M.; Young, H.M.; Churchward, D.R.; Burton, J.O.; Smith, A.C.; Bishop, N.C. Regular exercise during haemodialysis promotes an anti-inflammatory leucocyte profile. Clin. Kidney J. 2017, 10, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dungey, M.; Bishop, N.C.; Young, H.M.; Burton, J.O.; Smith, A.C. The impact of exercise during haemodialysis on blood pressure, markers of cardiac injury and systemic inflammation—Prelimminay results of a pilot study. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2015, 40, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.; Davis, P.; Patidar, A.; Zhang, Y.; Vilar, E.; Finkelman, M.; Farrington, K. The effect of intra-dialytic exercise on inflammation and blood endotoxin levels. Blood Purif. 2017, 44, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, N.; Smith, A.C.; Dungey, M.R.; Young, H.M.; Burton, J.O.; Bishop, N.C. Exercise during hemodialysis does not affect the phenotype or prothrombotic nature of microparticles but alters their proinflammatory function. Physiol. Rep. 2018, 6, e13825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- March, D.S.; Lai, K.B.; Neal, T.; Graham-Brown, M.P.M.; Highton, P.J.; Churchward, D.R.; Young, H.M.L.; Dungey, M.; Stensel, D.J.; Smith, A.C.; et al. Circulating endotoxin and inflammation: Associations with fitness, physical activity and the effect of a 6-month programme of cycling exercise during haemodialysis. Nephrol. Dial. Trans. 2022, 37, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highton, P.J.; March, D.S.; Churchward, D.R.; Grantham, C.E.; Young, H.M.L.; Graham-Brown, M.P.M.; Estruel, S.; Martin, N.; Brunskill, N.J.; Smith, A.C.; et al. Intradialytic cycling does not exacerbate microparticles or circulating markers of systemic inflammation in haemodialysis patients. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2022, 122, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.T.; Liu, W.C.; Lin, F.H.; Huang, C.F.; Chen, S.Y.; Liu, C.C.; Lin, S.H.; Lu, K.C.; Wu, C.C. Intradialytic aerobic cycling exercise alleviates inflammation and improves endothelial progenitor cell count and bone density in hemodialysis patients. Medicine 2016, 95, e4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.J.; Zhang, H.L.; Yin, L.X. Effects of intradialytic resistance exercise on systemic inflammation in maintenance hemodialysis patients with sarcopenia: A randomized controlled trial. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2019, 51, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umami, V.; Tedjasukmana, D.; Setiati, S. The effect of intradialytic exercise twice a week on the physical capacity, inflammation, and nutritional status of dialysis patients: A randomized controlled trial. Hemodial. Int. 2019, 23, 486–493. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, E.; Aragoncillo, I.; Moreno, J.; Vega, A.; Abad, S.; García-Prieto, A.; Macias, N.; Hernandez, A.; Godino, M.T.; Luño, J. Exercise training during hemodialysis sessions: Physical and biochemical benefits. Ther. Apher. Dial. 2020, 24, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meléndez-Oliva, E.; Sánchez-Vera Gómez-Trelles, I.; Segura-Orti, E.; Pérez-Domínguez, B.; García-Maset, R.; García-Testal, A.; Lavandera-Díaz, J.L. Effect of an aerobic and strength exercise combined program on oxidative stress and inflammatory biomarkers in patients undergoing hemodialysis: A single blind randomized controlled trial. In International Urology and Nephrology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sovatzidis, A.; Chatzinikolaou, A.; Fatouros, I.G.; Panagoutsos, S.; Draganidis, D.; Nikolaidou, E.; Avloniti, A.; Michailidis, Y.; Mantzouridis, I.; Batrakoulis, A.; et al. Intradialytic Cardiovascular Exercise Training Alters Redox Status, Reduces Inflammation and Improves Physical Performance in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dungey, M.; Hull, K.L.; Smith, A.C.; Burton, J.O.; Bishop, N.C. Inflammatory factors and exercise in chronic kidney disease. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2013, 2013, 569831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolucci, E.M.; Loukov, D.; Bowdish, D.M.E.; Heisz, J.J. Exercise reduces depression and inflammation but intensity matters. Biol. Psychol. 2018, 133, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.D.; Yeun, Y.R. Effects of Resistance Training on C-Reactive Protein and Inflammatory Cytokines in Elderly Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadelha, A.B.; Cesari, M.; Corrêa, H.L.; Neves, R.V.P.; Sousa, C.V.; Deus, L.A.; Souza, M.K.; Reis, A.L.; Moraes, M.R.; Prestes, J.; et al. Effects of pre-dialysis resistance training on sarcopenia, inflammatory profile, and anemia biomarkers in older community-dwelling patients with chronic kidney disease: A randomized controlled trial. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2021, 53, 2137–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadjapong, U.; Yodkeeree, S.; Sungkarat, S.; Siviroj, P. Multicomponent Exercise Program Reduces Frailty and Inflammatory Biomarkers and Improves Physical Performance in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, T.J.; Shur, N.F.; Smith, A.C. “Exercise as medicine” in chronic kidney disease. Scand J. Med. Sci. Sports 2016, 26, 985–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moinuddin, I.; Leehey, D.J. A comparison of aerobic exercise and resistance training in patients with and without chronic kidney disease. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2008, 15, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, H.; Reid, J.; Slee, A. Resistance exercise and nutritional interventions for augmenting sarcopenia outcomes in chronic kidney disease: A narrative review. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2021, 12, 1621–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).