Abstract

Despite major advances in guideline-directed cardiovascular therapy, residual cardiovascular risk persists, partly driven by oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and mitochondrial injury not fully addressed by current drugs. Translation of plant-based cardioprotectants is constrained by preparation-dependent variability in extract chemistry (plant part/cultivar/processing and extraction method), low and variable systemic exposure for key actives (notably curcuminoids and many polyphenols), and clinically relevant safety/interaction considerations (e.g., hepatotoxicity reports with concentrated green tea extracts and antiplatelet-related bleeding-risk considerations for some botanicals). We therefore provide a mechanism- and translation-oriented synthesis of evidence for cardioprotective botanicals, chosen for long-standing traditional use and scientific validation with reproducible experimental data and, where available, human studies, including Crataegus monogyna, Allium sativum, Olea europaea, Ginkgo biloba, Leonurus cardiaca, and Melissa officinalis. Across studies, polyphenols (especially flavonoids and phenolic acids) and organosulfur compounds are most consistently associated with cardioprotection, while terpene-derived constituents and secoiridoids contribute mechanistically in plant-specific settings (e.g., Ginkgo and Olea). Predominantly in experimental models, these agents engage redox-adaptive (Nrf2), mitochondrial (mPTP), endothelial, and inflammatory (NF-κB) pathways, with reported reductions in ischemia–reperfusion injury, oxidative damage, and apoptosis. Clinical evidence remains heterogeneous and is largely confined to short-term studies and surrogate outcomes (blood pressure, lipids, oxidative biomarkers, endothelial function), with scarce data on hard cardiovascular endpoints or event reduction. Priorities include standardized, chemotype-controlled formulations with PK/PD-guided dosing and adequately powered randomized trials that assess safety and herb–drug interactions.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with prevalence further amplified by population ageing and cardiometabolic risk factors such as obesity and type 2 diabetes [1,2,3,4]. This sustained burden, together with substantial healthcare and productivity costs and persistent inequities in access to preventive and advanced care, underscores the need for effective and scalable strategies that complement contemporary cardiovascular management [5].

The contemporary management of atherosclerotic and other major cardiovascular conditions involves a comprehensive approach that includes population-level prevention, lifestyle modifications, and evidence-based pharmacotherapy (e.g., lipid-lowering agents, antiplatelet drugs, antihypertensives) alongside invasive procedures when warranted [2,6]. Although these strategies have reduced cardiovascular mortality and improved outcomes, their real-world effectiveness is persistently constrained by adverse effects, limited access, and suboptimal long-term adherence [5,7]. Even with guideline-directed therapies, many patients remain at significant residual cardiovascular risk, including residual inflammatory risk (e.g., persistently elevated hsCRP), residual lipid-related risk (e.g., triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and lipoprotein (a) despite optimized LDL-C lowering), residual thrombotic risk, and cardiometabolic risk driven by diabetes/obesity and endothelial dysfunction, pathological drivers that are incompletely addressed by current treatments [2,6,7]. Furthermore, long-term therapy can be limited by a trade-off between efficacy, tolerability, access, and adherence, which may reduce real-world effectiveness [8]. Consequently, there is an increasing interest in complementary and alternative therapies, including nutraceuticals and herbal preparations, which may extend treatment options for cardioprotection through diverse mechanisms and improved safety profiles [5,6,9].

Plant-derived bioactive compounds are secondary metabolites produced by plants known for their biological activity. Historically utilized in traditional medicine and increasingly explored as potential therapeutic agents, these compounds encompass a range of classes relevant to cardiovascular health, including polyphenols (e.g., flavonoids, phenolic acids), alkaloids, terpenoids, saponins, and others [10,11,12,13]. Phytochemicals may be administered as isolated compounds (e.g., curcumin, resveratrol, quercetin) or as complex plant extracts, both of which have shown cardioprotective effects predominantly in preclinical settings, with a subset progressing to clinical investigation. This distinction is critical for reproducibility and translation: isolated compounds enable defined purity, dosing, and PK/PD characterization, whereas extracts exhibit batch-to-batch variability driven by chemotype, cultivation/harvesting conditions, and processing, which can confound attribution of efficacy and safety to specific constituents. Conversely, extracts may provide multi-target activity through additive or synergistic interactions, but require rigorous standardization and quality control to support mechanistic interpretation, regulatory acceptance, and reliable clinical evaluation [14,15,16,17,18].

A distinguishing characteristic of many plant-derived cardioprotective agents, as suggested largely by preclinical research, is their multimodal action. Rather than acting through a single target, phytochemicals have been reported, predominantly in in vitro, ex vivo, and animal models, to influence multiple pathways crucial to cardiovascular disease pathogenesis, including oxidative stress, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction [18,19,20]. For instance, polyphenols have been shown in experimental systems to reduce reactive oxygen species (ROS) and enhance cytoprotective signaling, thereby limiting oxidative damage in cardiac and vascular cells [21]. Concurrent anti-inflammatory actions observed mainly in preclinical models further support cardiovascular protection by attenuating chronic vascular inflammation [19]. In models of myocardial injury, selected phytochemicals have been reported to exert anti-apoptotic effects and to modulate autophagy-related pathways, with relevance to ischemic injury and drug-induced cardiotoxicity [18]. Likewise, evidence from cellular and animal ischemia models suggests that specific saponins can promote endothelial protection and pro-angiogenic signaling, potentially supporting vascular repair. However, the clinical relevance and translatability of these mechanisms remain to be established [22,23]. Beyond direct myocardial and vascular mechanisms, cardioprotection may also be achieved indirectly by modulating upstream cardiometabolic risk factors that drive disease progression. Accordingly, several phytochemicals have been reported (predominantly in preclinical and early clinical studies) to influence systemic metabolic determinants of CVD, including lipid homeostasis and related dysmetabolic profiles [4,23,24].

An increasing body of evidence supports the protective roles of phytochemicals across a range of cardiovascular conditions, with numerous in vivo and in vitro studies demonstrating efficacy against various models of myocardial injury and thrombotic events [7,17,19,20,25]. Some plant-derived agents have progressed to clinical trials, where they have shown potential benefits at the population level, emphasizing the need for well-designed randomized trials with uniform protocols and meaningful clinical outcomes [1,9]. However, substantial translational challenges persist, including issues related to variable bioavailability, instability, and the rapid metabolism of many natural compounds, as well as variability and inconsistency in botanical extracts [8,14,26]. Strategies to enhance clinical applicability involve formulation science techniques, rigorous standardization of phytochemicals, and advanced pharmacological methodologies to better understand and prioritize therapeutic prospects [14,27,28,29].

In light of the compositional variability of botanical preparations, heterogeneity of experimental designs, and the limited and often inconsistent clinical evidence, together with key translational uncertainties related to standardization and bioavailability, the present review aims to (1) synthesize and contextualize the principal mechanisms of plant-derived cardioprotection; (2) highlight plant sources and phytochemicals supported by the most reproducible experimental evidence and, where available, human data; (3) critically appraise preclinical and clinical findings with attention to methodological limitations and outcome relevance; and (4) define priority research directions to improve translatability, including extract standardization/chemotype control, PK/PD-guided optimization of bioavailability, and rational evaluation of combinations with guideline-directed therapies.

2. Concept of Cardioprotection in Cardiovascular Research

Cardioprotection refers to the ensemble of endogenous adaptive responses and exogenous interventions that reduce myocardial injury and preserve cardiac structure and function in the face of acute or chronic stressors, most notably ischemia/reperfusion (I/R), as well as pharmacologic cardiotoxins and surgical insults. Over the past decades, the field has adopted outcome-oriented definitions in which the success of a cardioprotective maneuver is judged by reductions in tissue necrosis and cell death, preservation of contractile performance and electrical stability, and mitigation of adverse remodeling. These outcomes have been operationalized in preclinical and clinical studies as infarct size, biochemical biomarkers of myocyte injury, imaging-derived salvage and functional parameters, and clinical endpoints, including heart failure and death [30,31,32,33].

The contemporary framework of cardioprotection was catalyzed by ischemic preconditioning (IPC), in which brief sublethal ischemia activates endogenous signaling that increases myocardial tolerance to subsequent ischemia/reperfusion injury [34]. IPC quickly catalyzed a large mechanistic enterprise that identified triggers (adenosine, bradykinin, nitric oxide), early mediators (reactive oxygen species—ROS), ionic effectors (sarcolemmal and mitochondrial ATP sensitive K+ channels, KATP), and downstream signal transduction modules (protein kinase C isoforms, PI3K–Akt–ERK prosurvival kinases, and regulators of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, mPTP) as central components of the cardioprotective cascade. These discoveries reframed cardioprotection from a descriptive phenomenon to a mechanistically tractable therapeutic concept [34,35,36]. In parallel, pharmacological agents (e.g., volatile anesthetics, opioids, KATP modulators, Toll-like receptor ligands) were shown to recapitulate core features of IPC (pharmacological or anesthetic preconditioning), demonstrating that molecular pathways of cardioprotection are amenable to drug-based manipulation and thereby accelerating translational interest [37,38,39,40].

Subsequent expansions of the paradigm included delayed (second window) preconditioning, ischemic postconditioning (brief cycles of reperfusion/ischemia at the onset of reperfusion), and remote ischemic conditioning (brief ischemia–reperfusion applied to a limb or distant organ producing cardioprotection), each of which extended the operational definition of cardioprotection and highlighted systemic neurohumoral as well as local myocardial mechanisms [32,41,42,43]. Importantly, these conceptual advances created a translational pipeline in which experimental manipulations (e.g., mPTP blockade by cyclosporine A) could be tested in patients with acute myocardial infarction. However, translation has proved challenging and underscores the complexity of clinical cardioprotection [33,44].

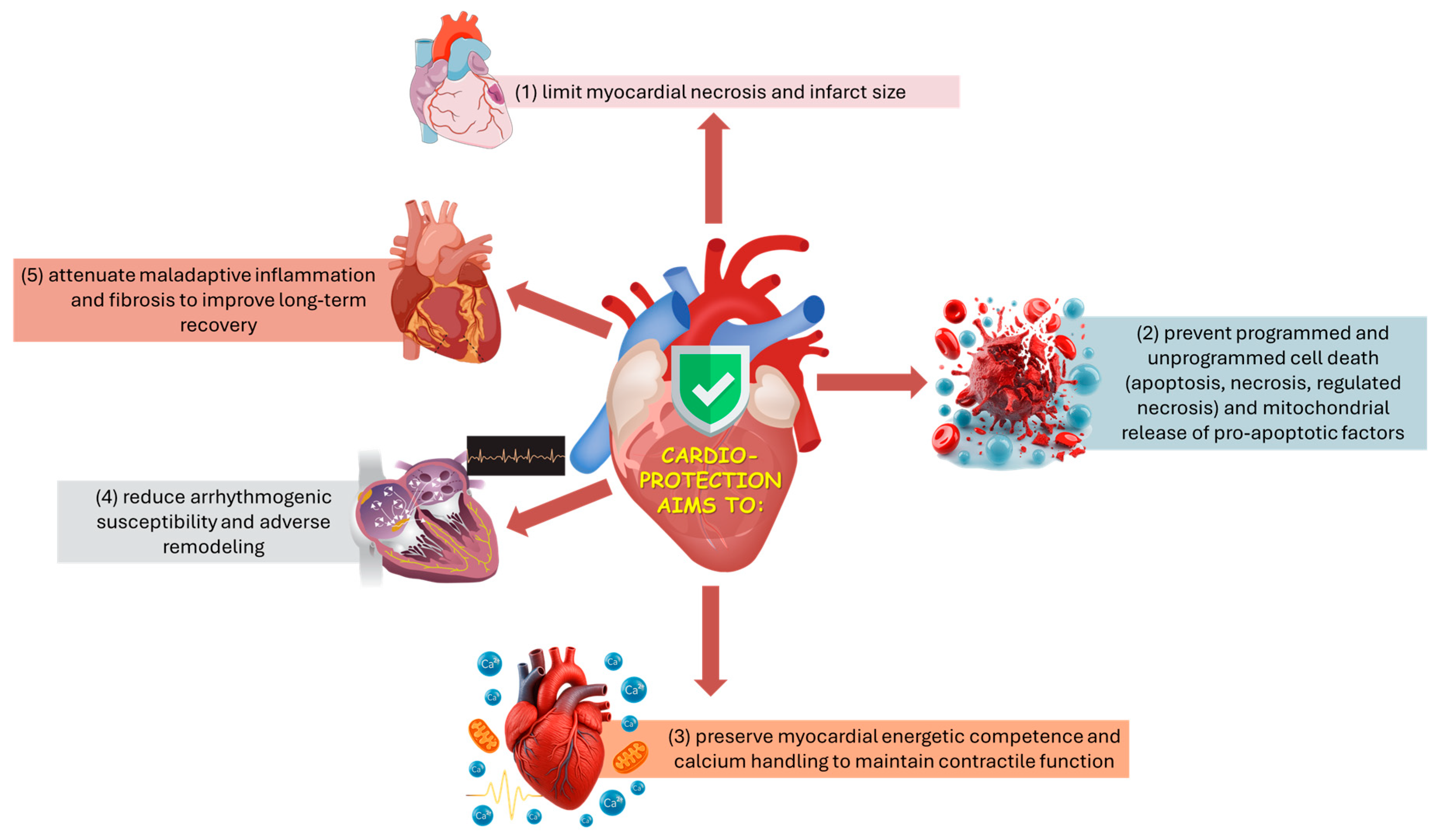

From an applied biomedical perspective, cardioprotection aims to limit infarct development and preserve post-injury cardiac performance by coordinating control of mitochondrial permeability and energy/Ca2+ homeostasis, suppression of regulated cell-death programs, and modulation of arrhythmogenic, inflammatory, and fibrotic remodeling processes (Figure 1) [30,31,33,34]. Because these processes are tightly coupled, stabilizing mitochondria, particularly by preventing mPTP opening, can simultaneously reduce necrotic cell death and downstream inflammatory amplification, improving infarct size and post-ischemic function [39,45].

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the main targets of cardioprotection.

From a mechanistic standpoint, cardioprotective strategies converge on a set of recurrent cellular targets and processes that together determine myocardial fate during and after ischemia:

- Mitochondria as nodal effectors:

Mitochondria occupy a central position in cardioprotection by integrating metabolic, redox, and cell-death signals, and by shaping susceptibility to reperfusion injury. Inhibition of mPTP opening at reperfusion is widely recognized as a final common effector of multiple conditioning strategies [39,40,45]. Additional mitochondrial-associated mechanisms implicated in protection include activation of mitochondrial KATP channels (mitoKATP) and maintenance of hexokinase II (HKII) association with the outer mitochondrial membrane, both of which have been linked to improved mitochondrial stability and reduced pro-death signaling during reperfusion [37,46,47,48]. Moreover, conditioned myocardium recruits mitochondrial quality control processes (mitophagy and regulated dynamics of fission/fusion) that remove dysfunctional mitochondria and thereby enhance post-ischemic recovery [49,50].

- Redox signaling and reactive oxygen species:

ROS play an important, double-edged role in cardioprotection: low to moderate ROS bursts act as necessary signaling triggers for IPC and for several pharmacological preconditioning mimetics, whereas excessive or sustained oxidative stress mediates cellular injury during reperfusion. Accordingly, experimental studies have shown that ROS scavengers can abrogate preconditioning in some models, and ROS generators (e.g., menadione) can mimic IPC when applied at sublethal doses. The net effect depends on timing, subcellular localization (mitochondrial versus cytosolic), and the balance between ROS formation and antioxidant buffering capacity [51,52,53,54].

- Ion channels and calcium homeostasis:

Preservation of calcium homeostasis is fundamental to cardioprotection: preconditioning attenuates reperfusion-induced calcium overload, and manipulation of ion channels—including sarcolemmal and mitochondrial KATP channels—modulates the myocardium’s resistance to injury; pharmacologic blockade of KATP channels abolishes IPC in several preparations, demonstrating their causal role in many models [55,56,57,58]. Calcium signaling also interfaces with other modules (e.g., IP3 pathways, PKC activation) that influence survival versus death decisions [59].

- Prosurvival kinase cascades and phosphorylation networks:

Conditioning stimuli activate prosurvival kinase programs—commonly summarized as the reperfusion injury salvage kinase (RISK) pathway (PI3K–Akt, ERK1/2) and other modulators including PKC isoforms (notably PKCε) and GSK 3β—that converge on mitochondrial targets (including mPTP regulation) and on transcriptional responses; phosphorylation of Akt and ERK at reperfusion is a reproducible molecular signature of IPC-mediated protection in experimental hearts [37,38,40,60]. PKCε translocation to mitochondria and phosphorylation of mitochondrial substrates (e.g., connexin43) have been implicated in the preservation of mitochondrial function and in limiting apoptotic signaling [37,60].

- Metabolic and transcriptional reprogramming:

Delayed (second-window) preconditioning and some pharmacologic interventions extend beyond acute post-translational signaling by engaging longer-term metabolic and transcriptional adaptation programs that increase stress resistance. These programs can upregulate antioxidant defenses and electron transport chain components and remodel substrate utilization, thereby improving tolerance to subsequent ischemic or metabolic insults [61,62]. Transcriptional induction of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes after delayed IPC illustrates this genomic dimension of cardioprotection [61,62]. In parallel, nutrient-sensing regulators such as TXNIP and thioredoxin systems interface with mitochondrial function and redox balance, linking metabolic status to cardioprotective resilience [63].

- Inflammation, complement, and extracellular mediators:

Conditioning influences local and systemic inflammatory responses: IPC reduces myocardial complement gene expression and modulates cytokine pathways, while systemic inflammatory mediators (and transcription factors such as NF κB) participate in the heart’s response to surgical or ischemic stress. Manipulation of inflammatory signaling represents both a target and a readout of cardioprotection [64,65].

Experimental assessment of cardioprotection employs a hierarchy of models and endpoints that span reductionist preparations to animal and human studies. In preclinical laboratories, infarct size (commonly measured by 2,3,5 triphenyl tetrazolium chloride, TTC, staining in experimental ischemia models) remains the canonical metric of tissue salvage, often complemented by measures of mitochondrial function, cytochrome C release, ROS production, and markers of apoptosis and necrosis [37,45,64]. Isolated perfused heart preparations and single cell myocyte studies enable mechanistic dissection (e.g., KATP channel function, PKCε translocation to mitochondria, mitoKATP opening) that link molecular events to functional outcomes [37,66,67,68]. In translational and clinical research, biochemical biomarkers (cardiac troponins), imaging modalities (cardiac MRI, nuclear perfusion imaging), and hard clinical endpoints (mortality, heart failure) are used to quantify protection and to evaluate therapeutic candidates, but differences between experimental conditions and clinical heterogeneity have complicated translation [31,32,33].

Several pharmacological and natural interventions have been instrumental in defining and dissecting cardioprotective mechanisms. Classical humoral mediators of IPC (adenosine, bradykinin, and nitric oxide) were among the earliest triggers implicated in initiating protection and have been studied in both experimental and clinical contexts [35,36]. Mechanistically, these mediators activate receptor- and endothelium-linked signaling that engages kinase cascades and NO-dependent pathways, which converge on mitochondrial effectors (including KATP channel- and mPTP-related processes) to increase tolerance to ischemia/reperfusion injury [35,36]. Volatile anesthetics (e.g., isoflurane) and opioids (e.g., morphine) produce anesthetic- and opioid induced preconditioning that reproduces many IPC phenotypes and clarified intracellular effectors such as KATP channels and PKC isoforms [41,42,43,66]. Experimental application of ROS-generating agents at sublethal doses (e.g., menadione) mimicked IPC, substantiating the role of regulated ROS bursts as triggers [69], while free radical scavengers could negate protection in some models, underscoring the finely balanced role of redox signaling [70,71]. Natural products and botanical extracts (e.g., garlic preparations) have been reported to elicit IPC-like cardioprotective effects predominantly in preclinical models, supporting the concept that phytochemical agents can engage conserved endogenous defense programs [72]. Importantly, these effects often converge on canonical cardioprotective nodes described for conditioning stimuli, including redox-adaptive signaling, endothelial mediator pathways (e.g., NO/H2S), kinase-driven cytoprotective cascades, and mitochondrial stabilization with downstream control of mPTP opening. This mechanistic convergence provides a unifying rationale for evaluating botanicals as multi-target adjuncts that may address residual risk processes insufficiently mitigated by single-pathway therapies, while also highlighting the need for rigorous standardization and PK/PD-informed dosing to improve translatability. At the molecular therapeutic level, blockade of mPTP opening by cyclosporine A entered clinical testing on the premise that inhibiting mPTP at reperfusion would reduce infarct size, exemplifying how mechanistic insight can motivate early clinical translation [39,44].

Emerging evidence indicates that cardioprotective efficacy is strongly modulated by comorbid conditions (e.g., diabetes, ageing, and sex hormone status), concomitant medications (e.g., P2Y12 inhibitors and anesthetics), and the timing and intensity of the conditioning stimulus. These factors can markedly attenuate, reshape, or mask cardioprotective signaling, such that benefits observed in reductionist models may not be reproducible across heterogeneous, poly-medicated clinical populations [44,73,74,75]. Remote ischemic conditioning, which appeared promising in mechanistic and pilot clinical studies, produced neutral results in a large randomized trial of ST elevation myocardial infarction (CONDI 2/ERIC PPCI), emphasizing the challenges of clinical translation and the need to reconcile heterogeneity between model systems and patient cohorts [33,43,73,76]. Further complicating translation, conditioning stimuli are not universally benign: conditioning responses are tissue-, cell type-, and context-dependent and, in non-cardiac models, can even exacerbate injury under specific experimental conditions (e.g., deleterious effects on oligodendrocytes reported in some cerebral preconditioning paradigms) [32,77]. Collectively, these observations underscore that cardioprotective strategies must be calibrated to biological context and evaluated with explicit attention to safety, dose-timing parameters, and patient-level heterogeneity [32,77].

Collectively, decades of experimental and translational research indicate that cardioprotection converges on a conserved set of mechanistic nodes, including mitochondrial stability (notably regulation of mPTP opening and related mitochondrial effectors), redox and ion/Ca2+ homeostasis, pro-survival kinase signaling, mitochondrial quality control, and regulated inflammation, that shape myocardial resilience to ischemic and non-ischemic insults [38,39,40,45,49,50]. This mechanistic framework has informed targeted strategies (e.g., mPTP inhibition, MQC- and kinase-directed interventions, and remote conditioning paradigms) and provides a direct rationale for exploring phytochemicals and botanical extracts as multi-target modulators capable of engaging these same endogenous protective pathways [44,49,72,78]. However, the recurrent mismatch between experimental promise and clinical outcomes underscores the need for rigorous translational frameworks that explicitly account for comorbidity, drug–drug/herb–drug interactions, timing, and clinically meaningful endpoints. Addressing these challenges remains essential if cardioprotective biology is to yield robust therapies that improve patient outcomes [31,32,33,73].

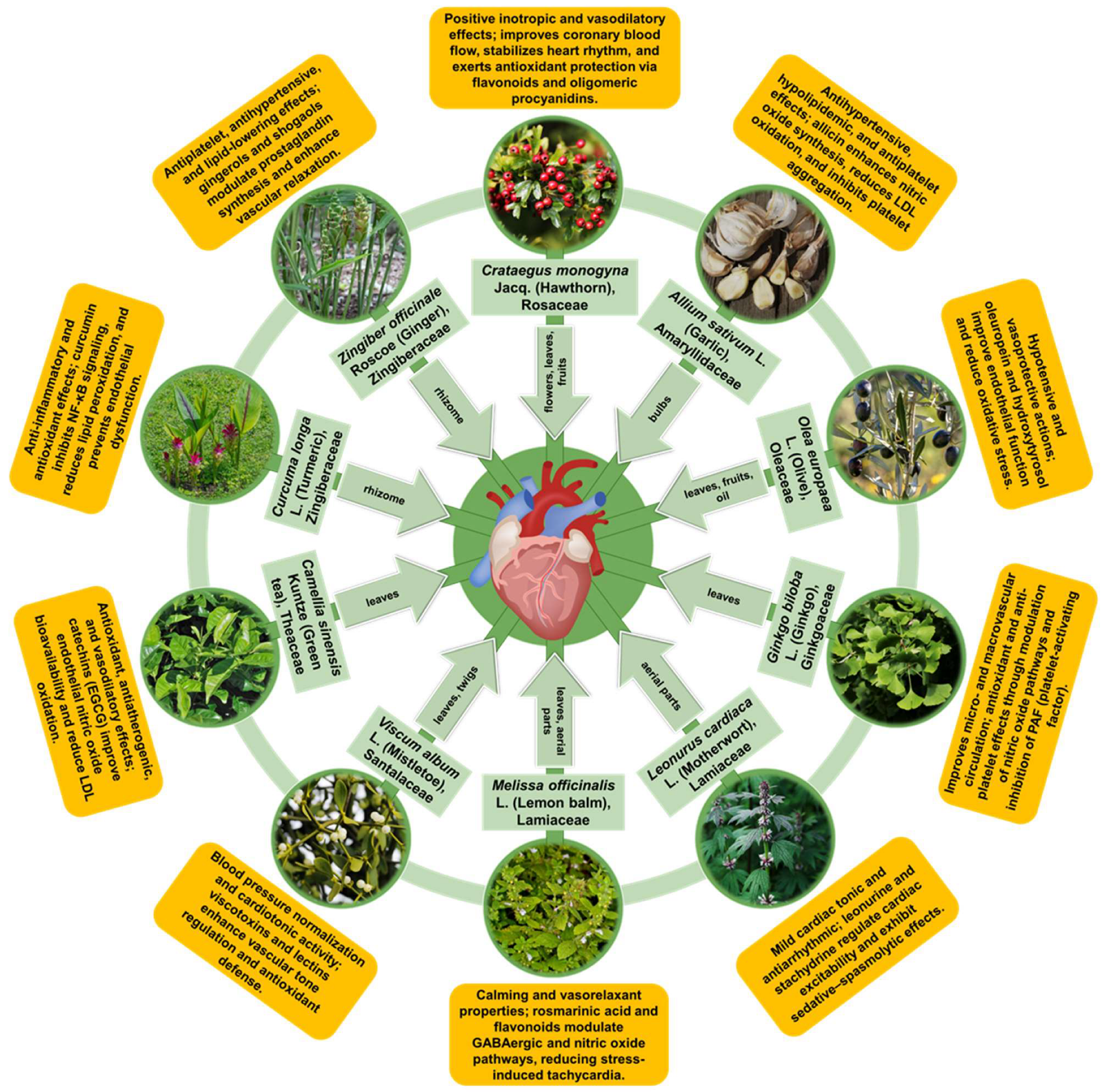

3. Common Cardioprotective Plants

In this section, we synthesize evidence for ten medicinal plant species with long-standing cardiovascular use that are also supported by reproducible experimental findings and, where available, human data. Rather than providing exhaustive monographs, we emphasize mechanistic interpretation and translational readiness by summarizing (i) the dominant phytochemical classes and standardized preparations, (ii) the convergent cardioprotective pathways mapped to the conserved nodes discussed above (e.g., redox/inflammatory control, endothelial function, and mitochondrial stability), and (iii) key limitations affecting clinical reproducibility, including extract variability, bioavailability, and safety in polypharmacy contexts.

3.1. Crataegus monogyna Jacq. (Hawthorn)

3.1.1. Historical Background

Crataegus monogyna Jacq. (hawthorn, Rosaceae family) is a well-established European cardiotonic botanical with long-standing use for functional cardiovascular complaints (e.g., palpitations and mild hypertension) and substantial pharmacological evaluation supporting this traditional rationale [79,80,81]. Ethnobotanical surveys report broadly consistent use across Mediterranean and Central European regions, with infusions or preparations from flowers, leaves, and fruits employed for hypertension, palpitations, and related circulatory symptoms, including in Romania [82,83,84]. Importantly for translation, European pharmacopoeias recognize hydroalcoholic extracts of leaves and flowering tops, and standardized preparations (notably WS®1442) have progressed into clinical testing, enabling more reproducible assessment of efficacy and safety than non-standardized products [79,81,85]. Related Crataegus species are used in other medical systems (e.g., C. pinnatifida in East Asia), underscoring cross-cultural convergence on hawthorn-derived products for cardiovascular indications [86,87,88].

3.1.2. Relevant Cardioprotective Phytocompounds

The cardioprotective properties of Crataegus monogyna have been attributed to a complex phytochemical matrix. Phytochemical profiling of C. monogyna consistently identifies polyphenols as the dominant bioactive fraction, with flavonoids (flavonol glycosides and related aglycones) and phenolic acids/anthocyanins most frequently implicated in the antioxidant, vasoregulatory, and endothelial effects attributed to hawthorn preparations [79,86,87,88,89,90]. These polyphenolic constituents are distributed across leaves, flowers, and fruits, with anthocyanin enrichment in ripe berries supporting additional lipid-modulating and endothelial-relevant activities [87,90]. Beyond polyphenols, triterpene/sterol-like fractions (e.g., cycloartenol-rich constituents) and minor components such as saponins and essential oils have been reported and provide complementary anti-inflammatory and functional contributions, although evidence for these classes is generally less extensive and more preparation-dependent [80,83,87,89,91].

Critically, the relative abundance of these phytochemical groups varies substantially with plant organ (leaves/flowers vs. berries), geographic origin, and post-harvest processing, and extraction conditions can markedly shift the recovered chemical profile and apparent bioactivity. Solvent selection is therefore a major determinant of reproducibility: in some endothelial assays, water fractions showed limited activity, whereas ethanol/methanol/acetone extracts retained bioactive fractions, underscoring the need to report and standardize extraction parameters when comparing studies or translating findings [83,88,92].

3.1.3. Mechanisms of Cardioprotective Effects and Medicinal Benefits

Collective experimental and clinical literature supports a multi-modal cardioprotective profile for Crataegus monogyna, in which different phytochemical fractions engage complementary molecular and physiological mechanisms. The principal mechanisms, with types of evidence, are summarized below:

- Antioxidant and direct ROS scavenging:

Hawthorn extracts and isolated polyphenolic fractions have shown robust radical-scavenging and lipid peroxidation–inhibiting properties in chemical assays and in vitro model systems. Electron paramagnetic resonance and biochemical studies indicate scavenging of superoxide-, hydroxyl-, and peroxyl-type radicals by Crataegus preparations, alongside reductions in lipid peroxidation and myoglobin oxidation in experimental settings [88,90,93]. In vivo, mainly in rodent models of cardiac injury (e.g., doxorubicin-induced chronic heart failure), hawthorn treatment has been associated with lower markers of oxidative injury (e.g., malondialdehyde) and increased endogenous antioxidant enzyme activity (e.g., glutathione peroxidase, catalase) [84,94]. While these findings support antioxidant/ROS-modulatory potential, the extent to which they translate into clinically meaningful cardioprotection remains incompletely established.

- Anti-inflammatory signaling and cytokine modulation:

Anti-inflammatory effects of hawthorn constituents have been reported primarily in experimental models. For example, a triterpene fraction reduced leukocyte migration and inhibited phospholipase A2 activity in acute inflammation paradigms, suggesting modulation of early inflammatory cascades [91]. In animal models of cardiac injury, hawthorn extracts have been associated with reduced myocardial pro-inflammatory cytokine expression (e.g., IL-1β, TNF-α) and attenuated histological inflammation, paralleling functional improvements in preclinical settings [84,94,95]. However, confirmatory clinical data for anti-inflammatory endpoints in cardiovascular populations remain limited.

- Endothelial protection, barrier integrity, and NO-mediated vasodilation:

Evidence from endothelial/vascular experimental models and limited clinical studies suggests that hawthorn preparations can improve endothelial function. An example of clinical evidence (surrogate endpoint) is a randomized, controlled crossover trial that reported that a standardized hawthorn extract improved flow-mediated dilation (FMD; an NO-dependent surrogate measure of endothelial function) in adults with prehypertension or mild hypertension [96]. Fractionation and molecular studies of WS®1442 indicate dual endothelial actions: promotion of barrier integrity via cortactin activation and inhibition of barrier-disruptive calcium signaling. These effects were localized to non-aqueous phytochemical fractions (ethanol/methanol/acetone) rather than the water fraction [92,97]. Together, these data support both vasodilatory (NO-mediated) and barrier-stabilizing effects of hawthorn phytochemicals (predominantly polyphenolic fractions) in clinical and laboratory settings [92,96,97].

- Lipid-lowering and anti-atherosclerotic effects

Hawthorn fruit and leaf extracts have shown hypolipidemic activity in animal models of dyslipidemia and cardiometabolic disease (e.g., JCR:LA-cp rodents) with improved plasma lipid profiles and concurrent cardiac benefits, supporting an anti-atherogenic potential of hawthorn polyphenols [90,98]. Studies concerning Crataegus clinical usage report favorable effects on hyperlipidemia and cardiovascular risk factors in clinical studies, although heterogeneity in extracts and study designs limits quantitative conclusions [88,99].

- Anti-apoptotic, anti-ischemia/reperfusion, and mitochondrial-protective actions:

Hawthorn extracts reduce ischemia–reperfusion (I/R) injury and biochemical indices of myocardial necrosis in perfused heart and cellular models. These cardioprotective outcomes are associated with ROS scavenging, preserved energy turnover, and reduced release of myocardial enzymes (CK, LDH) in preclinical experiments [93,94,100]. Although direct molecular dissection in hawthorn preparations is incomplete, these effects are consistent with established cardioprotective strategies that inhibit mitochondrial pathways of cell death [101,102].

- Positive inotropy and anti-arrhythmic properties:

In isolated human cardiac tissue and other experimental systems, standardized Crataegus extracts produced concentration-dependent increases in myocardial contractility accompanied by transient intracellular calcium changes. Studies suggest a cAMP-independent inhibition of Na+/K+-ATPase and concomitant improvements in myocyte energy turnover that differ from classical cardiac glycosides [103]. Additionally, Crataegus extracts can prolong action potential duration and refractory period, yielding anti-arrhythmic effects observed in experimental studies and invoked in clinical usage as cardiotonic/antiarrhythmic agents [99,103,104].

- Pro-cardiogenic and pro-angiogenic cues from stem/progenitor populations:

Recent studies indicate that WS®1442 stimulates cardiomyogenesis and angiogenesis from murine and human embryonic stem cells by promoting differentiation of cardiovascular progenitors rather than proliferation. Bioassay-guided profiling points to high-molecular-weight oligomeric procyanidin-containing fractions as drivers of this activity [97]. These findings suggest a novel pharmacology for hawthorn that extends beyond symptomatic modulation to potential support of reparative processes, although translation to in vivo regeneration remains to be established.

The hawthorn literature spans chemical, cellular, and whole-organism preclinical models (in vitro radical scavenging and molecular assays [88,93]; ex vivo myocardial contractility and endothelial fractionation experiments [92,103]; in vivo cardiac injury and metabolic models [94,98,100]) and is complemented by randomized clinical trials and multicenter evaluations of standardized extracts (e.g., WS®1442) that attest to symptomatic and functional cardiovascular benefits in specific populations [85,96,99,103]. However, heterogeneity in species, plant parts, extraction methods, and dose regimens complicates direct generalization across studies [83,86,88].

3.1.4. General Conclusion

Overall, Crataegus monogyna exhibits a multi-modal cardioprotective profile supported by a chemically complex phytochemistry dominated by polyphenols (notably oligomeric procyanidins and flavonoids), with additional contributions from triterpenes and other minor constituents [88,92,93,94,97]. Preclinical evidence supports effects on oxidative stress/ROS handling, inflammatory signaling, endothelial function (including NO-related vasodilation), lipid-related cardiometabolic parameters, and tolerance to ischemia–reperfusion–relevant insults; however, much of the mechanistic literature remains model-dependent [88,92,93,94,97]. In humans, studies using standardized preparations (e.g., WS®1442) suggest improvements mainly in symptoms and surrogate/functional outcomes such as endothelial function (FMD) and selected heart-failure related measures, whereas evidence for hard cardiovascular endpoints remains limited [85,96,99,103]. Hawthorn extracts are generally well-tolerated in clinical studies, but systematic pharmacokinetic characterization and interaction assessment in cardiovascular polypharmacy are still incomplete [81,99,105]. From a dosing perspective, the clinical literature for standardized hawthorn extract WS®1442 is largely anchored around ~900 mg/day, while dose-ranging exposures up to ~1800 mg/day have been evaluated with acceptable tolerability. Importantly, available dose-comparison data do not consistently show incremental benefit at the higher dose on vascular/functional surrogate endpoints, suggesting a possible plateau within commonly studied ranges and underscoring the need for PK/PD-linked dose–exposure analyses in future trials [81,88,92,93,94,97,99,105].

To strengthen translatability, priority should be given to (i) pharmacokinetic and bioavailability studies that define exposure to key constituents/metabolites and establish PK/PD relationships, including herb–drug interaction potential with common cardiovascular therapies, and (ii) harmonized clinical evaluation using standardized, chemotype-controlled formulations and pre-specified, standardized endpoint sets that clearly distinguish surrogate vascular/metabolic outcomes from hard cardiovascular endpoints in adequately powered randomized trials [81,88,97,99].

Collectively, the body of evidence positions Crataegus as a scientifically plausible source of cardioprotective phytopharmacology with a favorable safety profile and multiple mechanistic pathways amenable to deeper translational and clinical investigation.

3.2. Allium sativum L. (Garlic)

3.2.1. Historical Background

Allium sativum L. (garlic, Amaryllidaceae family) has a long history as both a culinary ingredient and a medicinal plant, with widespread traditional use for circulatory and cardiometabolic complaints across European, Ayurvedic, and Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) practices [106,107]. These historical indications have stimulated extensive experimental and clinical investigation of garlic-derived preparations as potential cardioprotective adjuncts, particularly in relation to blood pressure and lipid-related risk factors. Importantly, the evidence base is shaped by variability among formulations (e.g., raw garlic, powders, oils, and standardized preparations such as aged garlic extract), which differ in organosulfur composition, bioavailability, and tolerability. Consequently, mechanistic findings are predominantly derived from experimental models, whereas human data are heterogeneous and largely focused on surrogate cardiometabolic endpoints rather than hard cardiovascular outcomes [106,107,108].

3.2.2. Relevant Cardioprotective Phytocompounds

The cardioprotective activity of garlic is primarily attributed to organosulfur compounds (OSCs), with additional contributions from polyphenols/flavonoids, saponins, and polysaccharides that vary across bulb tissues and processing fractions [106,107,109]. In intact cloves, cysteine sulfoxides—particularly alliin (S-allyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide) and related γ-glutamyl derivatives—serve as key precursors [110,111]. Upon mechanical disruption (crushing, chopping, chewing), alliinase converts alliin to allicin (diallyl thiosulfinate), a highly reactive and unstable intermediate that rapidly decomposes into multiple oil- and water-soluble OSCs (e.g., diallyl sulfide (DAS), diallyl disulfide (DADS), diallyl trisulfide (DATS), ajoenes, and vinyldithiins) [110,112]. Aged or processed preparations are enriched in more stable, water-soluble metabolites such as S-allylcysteine (SAC) and S-allylmercaptocysteine (SAMC), which are frequently measured as bioactive markers and may better reflect in vivo exposure than allicin itself [113,114]. Beyond OSCs, garlic also contains phenolic constituents (e.g., quercetin) that can contribute to antioxidant and vasoactive effects, although these are generally considered secondary to OSC-driven activity [106,109,115].

Importantly, garlic phytochemistry is highly sensitive to cultivar/ecotype (e.g., purple vs. white cultivars), tissue composition, storage, and processing, leading to substantial differences in OSC yield and speciation across products. This variability is a major determinant of reproducibility and complicates direct comparison of mechanistic and clinical findings unless preparation methods and standardization markers are explicitly reported [110,116].

3.2.3. Mechanisms of Cardioprotective Effects and Medicinal Benefits

Mechanistic and efficacy evidence for garlic spans in vitro studies, ex vivo tissue models, and in vivo animal experiments, whereas human trials remain heterogeneous and are largely focused on surrogate cardiometabolic endpoints rather than hard cardiovascular outcomes [106,107,108,109,117]. Interpretation is further shaped by formulation-dependent differences in organosulfur composition, bioavailability, and dosing (e.g., raw garlic, oils, powders, aged garlic extract), which can confound cross-study comparability [110,111,113,114]. Within this evidence hierarchy, garlic—driven predominantly by organosulfur compounds (OSCs) and supported by polyphenols and other minor constituents—has been reported to modulate antioxidant/ROS pathways, inflammatory signaling (including NF-κB and Nrf2-related programs), endothelial/vasoactive regulation (notably H2S and NO pathways), lipid-related and anti-atherosclerotic mechanisms, cell-death/remodeling processes, and mitochondrial function [106,107,108,109,117]. The principal mechanisms, with types of evidence, are summarized below:

- Antioxidant and ROS scavenging:

Garlic extracts and isolated OSCs exert direct radical scavenging activity and indirectly enhance endogenous antioxidant defenses across experimental systems [106,108,109,118]. Ex vivo and in vivo investigations report reductions in lipid peroxidation markers (e.g., TBARS), attenuation of oxidative damage, and induction of antioxidant responses after garlic or OSC treatment [109,112,118,119]. Mechanistically, several garlic constituents have been reported to activate Nrf2-dependent antioxidant signaling and reduce oxidative stress predominantly in cellular and animal models. For example, allicin and related compounds have been associated with Nrf2 pathway modulation and downstream antioxidant gene expression in cellular systems [109,120,121].

- Anti-inflammatory signaling (NF κB, cytokine modulation):

Multiple studies have reported that garlic OSCs can suppress pro-inflammatory signaling and cytokine production in vitro and in animal models, including inhibition of NF-κB activation and reductions in mediators such as TNF-α and interleukins [106,111,120,121]. Ex vivo models and animal experiments show attenuation of inflammatory responses after garlic extract or isolated OSC administration, and mechanistic reports implicate cross-talk between Nrf2 activation and NF κB suppression as part of the protective signature [109,118,120,121]. Clinical studies assessing inflammatory biomarkers have yielded variable results and are generally limited to surrogate measures, emphasizing that translation of anti-inflammatory mechanisms into consistent clinical benefit likely requires standardized preparations, exposure-aware dosing, and adequately powered trials [109,122,123].

- Endothelial protection and NO/H2S regulation:

Garlic-derived OSCs influence vascular tone and endothelial function by modulating gaseous signaling mediators: hydrogen sulfide (H2S) production and nitric oxide (NO) signaling. Benavides et al. reported in preclinical models that OSCs can stimulate H2S generation in thiol-containing systems and proposed H2S-mediated relaxation of vascular smooth muscle via KATP channel activation as a major vasoactive mechanism [117]. Subsequent animal studies corroborate an H2S-dependent component of garlic’s vasoregulatory and cardioprotective effects, and S-allylcysteine or related metabolites have been implicated in these pathways in disease models (e.g., diabetic cardiomyopathy) [108,117,119]. Ex vivo isolated heart experiments with hydroalcoholic garlic extracts further support endothelial/vascular protective effects under oxidative and ischemic stress conditions [109].

- Lipid-lowering and anti-atherosclerotic effects:

Human trials most consistently report modest effects on blood pressure and lipid parameters, with substantial between-study heterogeneity and limited endpoint standardization [111,122,123].

Clinical trials indicate that certain garlic preparations can produce modest but statistically significant reductions in total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, as well as improvements in cardiometabolic indices in some populations, while heterogeneity in study design, dose, duration, and garlic formulation leads to inconsistent findings across studies [111,122,123]. Notably, most trials evaluate lipid profiles and related cardiometabolic surrogates rather than hard cardiovascular endpoints, which remain insufficiently studied for garlic preparations. Preclinical mechanistic work implicates OSC modulation of hepatic lipid metabolism (e.g., downregulation of lipogenic regulators such as SREBP-1 and ACC) and systemic effects mediated in part via alterations of the gut microbiome that favor improved lipid handling. These pathways have been described in dietary and obesity/non-alcoholic fatty liver disease models treated with garlic oil or defined OSCs [107,111,112]. Studies highlight that the precise active hypolipidemic moiety among allicin, SAC, DATS, and other OSCs remains uncertain, complicating therapeutic standardization [123,124].

- Anti-apoptotic and anti-fibrotic pathways:

In experimental cardiac injury models, garlic preparations and OSCs have been reported to reduce apoptotic signaling and improve contractile indices. In streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats, garlic oil supplementation reduced myocardial apoptosis and improved contractile indices, a benefit linked mechanistically to H2S signaling and to SAC activity in vivo [119]. At the molecular level, allyl sulfur compounds modulate apoptotic regulators (Bcl 2 family proteins, caspases, p53) in cell models and in vivo tissues, consistent with an ability to stabilize cell survival pathways in stressed myocardium and to reduce maladaptive remodeling [109,113,125]. These anti-apoptotic effects are reported across isolated cell systems, rodent disease models, and ex vivo heart preparations, although clinical evidence addressing cardiac remodeling remains limited [109,119,125].

- Mitochondrial protection and energy metabolism modulation:

OSCs preserve mitochondrial integrity by maintaining membrane potential, limiting mitochondrial swelling and cytochrome C release, and attenuating mitochondrial lipid peroxidation in isolated mitochondria and tissue models [109,112,113]. Such mitochondrial stabilization can translate into improved myocardial resilience to ischemia–reperfusion injury and metabolic insults in animal and ex vivo models, providing a plausible mechanistic bridge between cellular protection and organ-level cardiac function [109,119]. The variety of OSCs (oil and water-soluble) differs in mitochondrial bioactivity and cellular uptake, and metabolic conversion (e.g., to SAMC) modulates both potency and pharmacokinetics [113,114,124].

- Antiplatelet and antithrombotic actions:

Garlic exhibits antiplatelet and anticoagulant activities in multiple preclinical and some clinical reports, which may contribute to reduced atherothrombotic risk but also carries the potential for interaction with antithrombotic drugs. Reviews of garlic’s cardiovascular effects therefore recommend consideration of platelet modulating activity when garlic is used concomitantly with anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapies and emphasize the need for clinical monitoring in those settings [107,108].

The mechanistic and efficacy evidence for garlic spans in vitro cell culture and isolated mitochondria or tissue studies [113,121,125]; in vivo rodent disease models demonstrating improvements in blood lipids, blood pressure surrogates, myocardial function, and reduced apoptosis [112,114,119]; ex vivo isolated heart protection [109]; and randomized clinical trials showing modest cardiometabolic benefit but considerable between-study heterogeneity [111,122,123]. Dose–response interpretation in humans is formulation-dependent. Across hypertension and cardiometabolic trials, the most commonly studied regimens include standardized garlic powder (~600–900 mg/day; typically characterized by allicin yield) and aged garlic extract (often ~1.2 g/day, standardized to S-allyl cysteine). A dose–response program with aged garlic extract suggests a threshold/plateau pattern (a moderate daily dose achieving BP reductions, with no clear added benefit at higher dosing), highlighting why standardized chemistry and exposure-guided dosing are essential for reproducible clinical translation. A persistent translational challenge is formulation and bioavailability: allicin is generated only after tissue disruption and is chemically labile; metabolism in the gut and reactions with dietary thiols alter circulating OSC species, and different products (raw garlic, garlic oil, aged garlic extract, powdered preparations) yield divergent OSC profiles and pharmacokinetics. These factors underlie variability in clinical outcomes and complicate dose-effect interpretation [110,111,123,124].

3.2.4. General Conclusion

Overall, garlic (Allium sativum L.) is supported by a substantial preclinical literature and a growing, albeit heterogeneous, clinical literature as a multitarget cardioprotective botanical whose primary bioactivity is mediated by organosulfur chemistry (including allicin-derived sulfur species and the more stable water-soluble metabolites SAC and SAMC), with additional contributions from polyphenols and other constituents [106,107,110,111]. Mechanistically, garlic exerts antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, modulates endothelial vasoactive pathways (notably via H2S and NO), favorably influences lipid metabolism (including via gut microbiome interactions), stabilizes mitochondria, and reduces apoptotic signaling, actions documented in cell, isolated organ, and animal models and only partly reflected in human studies that primarily assess surrogate cardiometabolic outcomes (e.g., lipids and blood pressure), with limited evidence for hard cardiovascular endpoints [109,111,113,117,122,123]. Accordingly, translation would benefit from standardized, chemotype-controlled formulations with defined OSC markers and exposure-aware dosing, alongside adequately powered randomized trials that pre-specify harmonized endpoint sets, distinguishing surrogate vascular/metabolic and biomarker readouts (e.g., endothelial function, inflammatory markers, and NO/H2S-related measures) from hard cardiovascular outcomes, to clarify efficacy and dose–response relationships [108,110,116,123,124,126]. Safety considerations, including gastrointestinal tolerability, inter-individual differences in bioavailability/metabolism, and potential interactions with antithrombotic therapy, should be addressed prospectively through pharmacokinetic and herb–drug interaction studies and integrated into clinical development and practice recommendations [106,107,108]. Taken together, the preclinical mechanistic convergence and the suggestive clinical signal support continued rigorous translational research on garlic-derived compounds as candidate cardioprotective agents, with emphasis on standardized chemistry, pharmacokinetics, mechanism-directed biomarkers, and well-designed clinical trials.

3.3. Olea europaea L. (Olive)

3.3.1. Historical Background

Olea europaea L. (olive, Oleaceae family) and its products, most notably olive oil, are central to Mediterranean dietary patterns and have longstanding use in European traditional medicine, where leaf preparations and oil consumption were historically linked to circulatory and metabolic health [127,128,129]. Contemporary research has connected olive-derived interventions with the modulation of cardiovascular risk factors such as blood lipids, blood pressure, and low-grade inflammation, providing a mechanistic rationale for cardioprotective effects. However, the strength of human evidence varies by preparation and is often based on surrogate risk markers rather than hard cardiovascular endpoints [127,128,130,131]. Importantly, olive leaves and other non-culinary fractions (e.g., pomace and olive-mill by-products) can be enriched in phenolics and are increasingly explored for functional foods and nutraceuticals, but their translational interpretation depends on the rigorous characterization and standardization of phenolic profiles across sources and processing conditions [132,133,134].

3.3.2. Relevant Cardioprotective Phytocompounds

The cardioprotective bioactivity of Olea europaea is mainly attributed to (i) the phenolic fraction of olive-derived products—encompassing polyphenols and secoiridoids—and (ii) the monounsaturated fatty acid profile of olive oil. Across olive matrices, the most emphasized bioactive phenolic groups include secoiridoids (notably oleuropein and related ligstroside derivatives), simple phenolic alcohols (hydroxytyrosol and tyrosol), and phenolic aldehydes such as oleocanthal and oleacein, with additional contributions from flavonoids and other minor phenolics (e.g., phenolic acids, flavanols, verbascoside, and lignans) [128,131,135,136].

Compositional analyses consistently indicate compartmentation across plant parts and products: extra-virgin olive oil (EVOO) and fruits are relatively enriched in hydroxytyrosol/tyrosol and oleocanthal/oleacein, whereas olive leaves typically accumulate higher concentrations of oleuropein and related secoiridoids [135,136,137]. Critically, cultivar, processing, storage, and agronomic stressors (e.g., water deficit, salinity) can substantially shift phenolic abundance and speciation, making phenolic profiling and marker-based standardization (e.g., key secoiridoids and hydroxytyrosol-related metrics) central to reproducibility and translational interpretation [135,136,137]. Hydroxytyrosol, a principal in vivo derivative of oleuropein, is often highlighted for antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity, while oleocanthal and oleacein have attracted interest for distinct bioactivities. In contrast, the mechanistic contribution to the overall atheroprotective signal of several minor classes (lignans, verbascoside) remains less well-defined [131,137,138,139,140].

3.3.3. Mechanisms of Cardioprotective Effects and Medicinal Benefits

Mechanistic evidence for cardioprotection by olive-derived constituents is extensive but derives predominantly from chemical/cellular systems and animal models, while human evidence is largely drawn from dietary patterns and intervention studies that primarily assess intermediate (surrogate) risk markers rather than hard cardiovascular outcomes [128,130]. Interpretation is also preparation-dependent, as phenolic content and speciation vary markedly across EVOO, leaf extracts, and phenolic-enriched products depending on cultivar and processing, making phenolic profiling and standardization essential for reproducibility and translation [135,136,137]. The principal mechanistic themes include antioxidant/redox modulation, inflammatory signaling control, endothelial protection, lipid and metabolic regulation, anti-platelet/anti-atherogenic effects, and modulation of cell survival and energy metabolism.

- Antioxidant and ROS scavenging:

Hydroxytyrosol, oleuropein, and related phenols act as direct radical scavengers and chain-breaking antioxidants in chemical and cellular assays, reduce markers of oxidative damage (protein carbonyls, 4-hydroxynonenal), and limit LDL oxidation in experimental systems, thereby opposing a key early driver of atherogenesis and endothelial dysfunction [131,140,141,142]. Beyond direct scavenging, olive phenolics activate endogenous cytoprotective programmes; for example, hydroxytyrosol induces heme oxygenase 1 (HO 1) via Nrf2 stabilization in vascular endothelial cells, linking antioxidant chemistry to regulated redox signaling and improved cellular resilience [127,143,144,145].

- Anti-inflammatory signaling (NF κB, cytokine modulation, eicosanoid pathways):

Olive phenolics blunt pro-inflammatory pathways at multiple levels. Several studies show suppression of NF κB and AP 1 activation and consequent downregulation of adhesion molecules, cytokines, and matrix-remodelling enzymes in endothelial cells and immune cells [146,147,148]. For example, HT and other EVOO polyphenols attenuate TNF α-induced ROS production and NF κB signaling and reduce expression of MCP 1, CXCL10, COX 2, and MMP 2 in cell models, while oleuropein inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory responses in macrophages and zebrafish and reduces pro-inflammatory cytokine production in vitro and in vivo [146,148,149,150]. In parallel, inhibition of eicosanoid biosynthesis (lipoxygenase and downstream leukotriene formation) by oleuropein, hydroxytyrosol, and related phenols has been demonstrated in leukocyte models, providing a mechanistic basis for reduced leukocyte recruitment and vascular inflammation [149,151,152]. These anti-inflammatory actions are well-documented in experimental systems and provide biological plausibility for vascular benefit. However, direct evidence for coronary artery disease prevention or treatment in humans remains limited and requires confirmation in standardized, endpoint-driven clinical trials [149,152,153].

- Endothelial protection and nitric oxide regulation:

Olive phenolics protect endothelial cells from oxidative and inflammatory insults and suppress endothelial activation, specifically reducing expression of VCAM 1, ICAM 1, and E-selectin, thereby limiting leukocyte adhesion and early atherogenic events in vessel walls [131,146,148]. Hydroxytyrosol and its major circulating metabolites preserve endothelial function in human aortic endothelial cells and reduce markers of dysfunction in vitro. HT-dependent induction of HO-1 (Nrf2 pathway) contributes to endothelial repair and resilience, linking redox regulation to maintenance of endothelial homeostasis [127,143,148]. In inflammatory cell systems, HT also modulates nitric oxide pathways and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)-dependent responses, supporting a role for olive phenolics in balancing NO signaling under inflammatory stress [147,148].

- Lipid-lowering and anti-atherosclerotic effects:

Olive oil and leaf phenolics act additively with the monounsaturated fatty acid matrix to produce favorable effects on lipid metabolism and atherogenesis. Experimental work shows modulation of adipocyte transcriptional programmes, improvements in lipid and glucose handling (notably by oleacein and hydroxytyrosol), a reduction in LDL oxidation, and beneficial changes in plasma lipoprotein profiles in preclinical models, while population studies and diet-based interventions implicate olive oil consumption in lower cardiovascular risk [130,152,154,155]. Notably, most human studies in this area focus on lipid profiles, blood pressure, and inflammatory/oxidative biomarkers, whereas evidence for hard cardiovascular endpoints attributable to specific olive phenolics is still limited. Whole-genome transcriptomics in adipocytes exposed to oleacein identifies pathways linked to lipid and glucose metabolism and inflammation, linking a defined olive phenolic to specific metabolic gene networks [154]. Preclinical dietary studies of olive leaf extracts and phenolic-rich preparations report attenuation of cardiac, hepatic, and metabolic perturbations induced by obesogenic diets, and comparative studies indicate that both oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol-rich extracts can ameliorate high-fat diet-induced dyslipidaemia and liver injury in rats [130,152,154].

- Anti-apoptotic and anti-remodelling effects:

Isolated secoiridoids such as oleuropein exert cytoprotective and anti-apoptotic effects in tissue injury models. For example, attenuation of cisplatin-induced renal apoptosis via inhibition of ERK signaling has been reported, and olive leaf extracts reduce pathological cardiac and hepatic remodeling in diet-induced rodent models, suggesting potential for limiting maladaptive post-injury cardiac remodeling in preclinical systems [130,138,152]. While direct evidence for anti-fibrotic effects in human cardiac pathology remains limited, the preclinical data indicate plausibility for modulation of cell survival and fibrotic pathways by olive phenolics [128,152].

- Mitochondrial protection and energy metabolism modulation:

Emerging data from in vitro and transcriptomic studies indicate that olive phenolics influence energy metabolism, mitochondrial resilience, and redox-sensitive metabolic signaling, effects that are mechanistically relevant to cardiomyocyte energetics and systemic metabolic risk factors for cardiovascular disease [137,143,154]. These pleiotropic metabolic actions support the capacity of olive phenolics to act both on the vascular compartment and on metabolic tissues that drive cardiometabolic risk.

- Anti-platelet and anti-thrombotic properties:

Hydroxytyrosol, tyrosol, and other olive phenols exhibit anti-platelet and anti-PAF (platelet-activating factor) biosynthesis effects in cellular systems and have been associated with reduced platelet activation in experimental models, providing a mechanistic rationale for reduced thrombotic risk in the context of atherosclerotic disease [155,156,157].

- Epigenetic and transcriptomic modulation (nutrigenomic effects):

Beyond classical biochemical mechanisms, olive phenolics exert epigenetic and transcriptomic effects (microRNA modulation, histone modifications, and gene expression changes) that may underlie long-term modulation of inflammatory and metabolic pathways. Experimental omics studies document these epigenetic signals as a promising avenue for durable nutraceutical effects and precision nutrigenomics approaches [143,144,145,154]. These regulatory layers offer mechanistic bridges between dietary exposure, chronic disease risk modification, and individual variability in responses.

The mechanistic profile above is supported by a spectrum of data types: in vitro work using endothelial cells, macrophages, and adipocytes documents molecular targets and pathways (e.g., NF κB, AP 1, Nrf2/HO 1, 5-LOX) [146,148,150,151]; in vivo experiments (rodents, zebrafish) demonstrate organ-level benefits and improvements in lipid, inflammatory, and structural endpoints [130,138,152]; omics and transcriptomics approaches reveal pathway-level reprogramming by specific phenolics (e.g., oleacein) [154]; and human observational and dietary intervention literature (including Mediterranean-diet centered epidemiology and enriched-oil functional food studies) support associations between olive product consumption and lower cardiovascular risk, although high-quality randomized trials of isolated phytochemicals remain limited and are an active area for translation [128,130,149,156]. Pharmacokinetic studies indicate rapid metabolism of secoiridoids (oleuropein → hydroxytyrosol → conjugated metabolites) and renal excretion predominantly as glucuronides and sulfates, an important consideration for dosing, bioavailability, and clinical translation [137,138,139]. Safety and toxicology assessments of hydroxytyrosol and related phenolics are favorable in preclinical studies, and a growing body of human data supports tolerability at dietary and supplemental exposures, yet systematic clinical dose–response and long-term safety trials are still needed [128,156].

Overall, Olea europaea provides a spectrum of phenolic constituents (e.g., hydroxytyrosol-related species, oleuropein-derived secoiridoids, oleacein, and oleocanthal) that, predominantly in experimental models, have been reported to converge on redox-adaptive (Nrf2/HO-1) and inflammatory (NF-κB-related) pathways, preservation of endothelial homeostasis, modulation of platelet/eicosanoid signaling, and favorable lipid–glucose regulatory networks [128,131,140,146]. These mechanistic observations are broadly consistent with epidemiological and dietary-intervention literature linking olive-centered dietary patterns—particularly EVOO-rich diets—to improved cardiometabolic risk profiles and lower cardiovascular risk, but causal attribution to individual phytochemicals and demonstration of hard endpoint benefit remain areas for further translation [129,130,149].

Key research directions include adequately powered randomized trials of phenolic-enriched EVOO and chemotype-controlled standardized extracts with harmonized endpoint sets (clearly separating surrogate biomarkers from hard outcomes), PK/PD-informed dosing and exposure biomarkers, and mechanistic human studies (endothelial function, platelet reactivity, and omics-informed signatures) that account for processing/stability effects and inter-individual response variability [133,145,154].

3.3.4. General Conclusion

Overall, Olea europaea L. provides a chemically diverse repertoire of phenolic constituents that, predominantly in experimental models, have been reported to modulate redox and inflammatory pathways, support endothelial homeostasis, and influence lipid-related and platelet-associated processes. In humans, the most consistent evidence derives from olive-centered dietary patterns and phenolic-enriched interventions that primarily improve intermediate (surrogate) cardiometabolic markers, while demonstration of hard cardiovascular endpoint benefit attributable to specific phytochemicals remains limited. These considerations justify continued translational efforts to define standardized, chemotype-controlled formulations, PK/PD-informed dosing regimens, and clinically meaningful, harmonized endpoints that can establish efficacy and safety with reproducible bioavailability [128,133,140,154,155,156].

3.4. Ginkgo biloba L.

3.4.1. Historical Background

Ginkgo biloba L. (Ginkgoaceae family) has long-standing use in traditional Chinese medicine for conditions linked to impaired circulation and was later adopted in European phytotherapy, particularly for cerebrovascular insufficiency and peripheral circulatory symptoms such as intermittent claudication [158,159]. In modern phytopharmacology, Ginkgo is most closely associated with standardized leaf extracts (notably EGb 761), which provide a defined chemical profile and have been evaluated extensively in experimental models and, to a more limited and heterogeneous extent, in human studies relevant to vascular function [158,159,160,161]. These trans-cultural uses and the availability of standardized preparations have motivated continued research into Ginkgo leaf extracts as multi-constituent agents capable of engaging conserved pathways implicated in ischemia/reperfusion injury, endothelial dysfunction, and related cardiovascular contexts, while highlighting the need to interpret cardioprotective claims in light of evidence hierarchy and endpoint selection [158,159,161].

3.4.2. Relevant Cardioprotective Phytocompounds

The cardiovascular bioactivity of Ginkgo leaf preparations is primarily attributed to two dominant phytochemical families: (i) flavonoid glycosides (largely quercetin-, kaempferol-, and isorhamnetin-derived flavones/flavonols) and related polyphenols, and (ii) terpene trilactones (ginkgolides A–C and bilobalide) [160,162,163]. Evidence for the predominance of these phytocompounds in standardized preparations is exemplified by EGb 761 (typical composition: ≈24% flavone glycosides, ≈6% terpenes including ginkgolides and bilobalide) and by pharmacokinetic analyses that quantify ginkgolides and bilobalide in plasma after oral dosing [160,162,164].

Additional constituents (e.g., smaller phenolic acids, proanthocyanidins, and polysaccharide fractions) contribute to redox-related and immunomodulatory effects in experimental studies, but they are generally less emphasized in standardized leaf extracts and cardiovascular translation [164,165]. In mechanistic literature, the most frequently cited cardiovascular-relevant constituents include the flavonoid fraction and terpene trilactones—particularly ginkgolide B (often discussed in relation to PAF signaling) and bilobalide (reported to influence inflammatory and cell-survival pathways)—with most evidence deriving from preclinical models [162,166,167].

3.4.3. Mechanisms of Cardioprotective Effects and Medicinal Benefits

The cardioprotective profile of Ginkgo biloba extracts is attributed to multi-target actions of their major constituent classes (primarily flavonoids and terpene trilactones, with potential contributions from other fractions) that have been reported to influence oxidative stress, inflammation, endothelial function, platelet reactivity, mitochondrial integrity, and related signaling networks. Mechanistic support derives predominantly from in vitro and animal models (e.g., cardiac I/R, drug-induced cardiotoxicity, atherosclerosis paradigms), whereas human evidence is heterogeneous and largely focused on cerebrovascular and peripheral circulatory outcomes rather than hard cardiovascular endpoints [159,161,162,168]. The principal mechanisms, with types of evidence, are summarized below:

- Antioxidant and reactive oxygen species scavenging:

Ginkgo leaf flavonoids and proanthocyanidins exhibit direct free-radical scavenging and redox-modulatory activities that reduce lipid peroxidation (e.g., lower malondialdehyde) and restore endogenous antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT, GSH) in cell and animal models. Antioxidant synergy among flavones, proanthocyanidins, and organic acids has been demonstrated in vitro and underlies part of the extract’s protective effect against oxidative injury [163,169,170]. These antioxidant actions have been mechanistically linked to reduced oxidative stress in endothelial cells and myocardium in experimental ischemia/reperfusion and cardiotoxicity models [158,159].

- Anti-inflammatory signaling:

Preclinical studies suggest that multiple Ginkgo constituents can modulate inflammatory cascades. For example, polysaccharide fractions and leaf-derived constituents have been reported to attenuate NF-κB and MAPK signaling in macrophage and endothelial models and to influence cytokine-related regulatory networks (including microRNA-associated pathways) in experimental systems [165,167,171,172]. In animal and cellular models, these anti-inflammatory effects act in parallel with redox modulation to reduce endothelial activation and vascular inflammation relevant to atherogenesis [173,174].

- Endothelial protection and NO/HO-1 signaling:

Ginkgo preparations protect endothelial cells by attenuating oxidative stress-induced adhesion molecule expression and by activating cytoprotective enzyme systems. Notable mechanisms include the induction of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and activation of PI3K/Akt → eNOS signaling in endothelial progenitor and endothelial cells, with downstream increases in NO bioavailability, improved vasorelaxation, and facilitation of vascular repair in experimental vascular injury models [173,175,176].

- Lipid-lowering and anti-atherosclerotic effects:

Preclinical studies suggest that Ginkgo extracts attenuate atherogenesis through combined redox, inflammatory, and metabolic actions. Proposed mechanisms include Nrf2-linked cytoprotective signaling in vascular models and, in some experimental settings, associations with altered gut microbiota composition and microbial metabolites that could influence systemic lipid and inflammatory homeostasis [174,177]. While these findings support pleiotropic anti-atherosclerotic hypotheses, translation to consistent human lipid or atherosclerosis-related endpoints remains uncertain and requires controlled trials using standardized preparations and predefined outcomes [177].

- Anti-apoptotic and mitochondrial protective pathways:

Ginkgo phytoconstituents prevent programmed cell death through multiple mitochondrial targets: flavonoids (e.g., quercetin, myricetin) can inhibit apoptosis-inducing factor translocation from mitochondria to nucleus, bilobalide attenuates p53- and caspase-dependent mitochondrial apoptosis signaling, and extract-level treatments up-regulate Bcl-2 and down-regulate Bax in endothelial and cardiac models, thereby preserving mitochondrial membrane potential and reducing cytochrome-C release in studies of cardiotoxicity and I/R injury [166,167,169]. These mitochondrial actions underlie reported reductions in infarct size and improved cellular viability in animal experiments but require confirmation for hard clinical cardiovascular endpoints [158].

- Antiplatelet and antithrombotic activity:

Terpenic ginkgolides (especially ginkgolide B) exert antagonism at the platelet-activating factor (PAF) receptor, and standardized extracts show antiplatelet properties in experimental assays. These antithrombotic effects contribute to improved microvascular flow in models of vascular insufficiency but also create a mechanistic basis for potential bleeding risk when combined with other antithrombotic therapies, a safety consideration emphasized in research of herbal agents used in cardiovascular contexts [178].

- Vasoactivity, vasorelaxation, and antihypertrophic signaling:

Through eNOS activation and NO-mediated signaling (and possibly cholinergic/M2 receptor-linked pathways), Ginkgo preparations can induce vasorelaxation and have been reported to counter-regulate hypertrophic signaling in experimental models. Such vasodilatory and antihypertrophic effects have been demonstrated primarily in in vitro and in vivo animal studies and are invoked to explain improvements in peripheral circulation observed clinically for intermittent claudication and related disorders [173,175].

- Pharmacokinetics, metabolomics, and synergistic interactions:

Recent pharmacokinetic and metabolomic studies emphasize that Ginkgo flavonoids and terpenoids are extensively metabolized, that bioactive metabolites can contribute to systemic effects, and that synergistic interactions among flavones, proanthocyanidins, and organic acids enhance antioxidant capacity in vitro. These data argue that standardized extracts (rather than single isolated constituents) better capture the multi-target cardiovascular biology of Ginkgo but also highlight the need to characterize active metabolites and dose–response relationships in humans [160,162,163].

The mechanistic actions above are supported predominantly by in vitro assays and animal models (e.g., cardiac ischemia/reperfusion, drug-induced cardiotoxicity, atherosclerosis, and vascular injury paradigms). Human data are mixed and often derive from studies targeting cerebrovascular/cognitive indications and peripheral circulatory outcomes (e.g., intermittent claudication), whereas evidence that Ginkgo preparations reduce major cardiovascular clinical events remains inconclusive. Larger randomized trials using standardized extracts and clearly defined cardiovascular endpoint sets are therefore required to establish clinical relevance in cardiovascular populations [159,161,168,169,170,177]. Safety-oriented pharmacology and pharmacokinetic studies additionally document bioavailability constraints, metabolite formation, and dose-dependent responses that must be accounted for in clinical translation [162,179].

3.4.4. General Conclusion

Ginkgo biloba L. leaf preparations have been reported in preclinical research to exhibit a multi-modal cardioprotective signature, including antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity, endothelial protection involving HO-1/eNOS/NO-related pathways, mitochondrial and anti-apoptotic effects, antiplatelet activity linked to PAF antagonism, and vasoactive actions. Emerging microbiome-associated anti-atherosclerotic hypotheses have also been proposed primarily from experimental studies. These convergent mechanisms are attributable to flavonoid glycosides, proanthocyanidins, and terpenic lactones (ginkgolides, bilobalide) acting in concert within standardized extracts [163,174,175]. The majority of mechanistic and efficacy data derive from in vitro and animal models, with human studies being comparatively limited and largely focused on cerebrovascular/cognitive indications and peripheral circulatory outcomes. Accordingly, while Ginkgo may represent a multi-target adjunct for vascular protection, robust cardiovascular translation requires randomized trials using standardized extracts and clearly prespecified cardiovascular endpoint sets, with explicit distinction between validated surrogate outcomes and hard clinical events [159,161,168,169,178,180].

Practical research priorities include (i) rigorous standardization of extract composition and PK/PD-informed dose-exposure relationships (building on EGb 761 as a reference preparation); (ii) integrated pharmacokinetic/metabolomic and herb–drug interaction studies to define circulating active metabolites and bleeding-risk modifiers in cardiovascular polypharmacy; and (iii) adequately powered randomized trials in cardiovascular-risk populations that use harmonized, clinically meaningful endpoint sets (validated surrogate measures and/or hard outcomes) alongside systematic safety monitoring during co-administration with antithrombotic therapies [159,160,161,162,177].

3.5. Leonurus cardiaca L. (Motherwort)

3.5.1. Historical Background

Leonurus cardiaca L. (motherwort, Lamiaceae family) is a perennial herb widely used in European and parts of Asian traditional medicine and now naturalized across temperate regions [181,182]. In western herbal tradition, Leonurus cardiaca has been mainly applied for cardiac and circulatory complaints (such as palpitations and tachyarrhythmias), for nervous-cardiac symptoms (including anxiety and insomnia), and for female reproductive disorders. These indications are consistently documented in various phytotherapeutic compendia and modern research of the species’ pharmacology [183,184,185]. Preparations traditionally include infusions (teas), alcoholic tinctures, and standardized hydroalcoholic extracts of the aerial parts (leaves, stems, flowering tops). Such preparations have attracted experimental and pharmacopoeial attention, including European Pharmacopoeia-style extracts used in mechanistic studies [184,186]. Importantly, interpretation across studies is preparation-dependent (infusions vs. tinctures vs. standardized hydroalcoholic extracts), and much of the mechanistic evidence remains preclinical, underscoring the need for well-characterized formulations and endpoint-driven clinical evaluation in cardiovascular contexts. Parallel traditions in East Asia center on related Leonurus species (notably L. japonicus), which are prominent in Traditional Chinese Medicine for gynecological and circulatory disorders. Chemical and pharmacological similarities among Leonurus species warrant cross-species pharmacological inference, although species differences have been highlighted in chemotaxonomic and genetic studies [181,187].

3.5.2. Relevant Cardioprotective Phytocompounds

Phytochemical investigations of Leonurus cardiaca (primarily aerial parts) indicate a chemically complex profile in which alkaloids and polyphenols (flavonoids and phenylethanoid glycosides) are most frequently emphasized, alongside iridoid glycosides and minor terpenoid/volatile constituents [182,183,184]. Among alkaloids, stachydrine is consistently reported in L. cardiaca material, whereas leonurine—although widely studied across Leonurus taxa and often discussed in relation to L. japonicus—has also been detected/quantified in Leonurus preparations and is commonly cited for vascular and myocardial activities in preclinical literature [188,189,190]. In motherwort extracts, recurrent polyphenolic markers include hyperoside, rutin/quercetin derivatives, and phenylethanoid glycosides such as verbascoside, with additional contributions from iridoid glycosides (e.g., ajugol, harpagide) and phenolic acids (e.g., chlorogenic acid) [184,191]. Volatile and other terpenoid/sterol constituents have also been described and may contribute context-dependent hemodynamic effects, although mechanistic attribution is less well defined [182,183]. Mostly, the aerial parts (leaves/flowering tops) undergo comprehensive analysis, with contemporary studies utilizing analytical techniques (HPLC/HPTLC, GC–MS) establishing marker constituents (e.g., hyperoside, verbascoside) useful for standardization and activity-guided isolation [191]. Given preparation-dependent variability, reporting these marker constituents is important for cross-study comparability and for translating pharmacological findings to defined formulations.