Abstract

Cadmium (Cd) contamination in agricultural soils threatens food security and exacerbates climate change through its impact on greenhouse gas (GHG) (CO2, N2O and CH4) emissions, in which N2O and CO2 are the dominant fluxes of the terrestrial carbon-nitrogen cycle whose magnitude is directly amplified by Cd stress. Key remediation approaches for this dual challenge are phytoremediation and biochar amendment. This study aims to investigate the effects of Solidago canadensis (CGR) and biochar (BC) on soil remediation and GHG emissions under different levels of Cd contamination. A pot experiment with four Cd concentration gradients (0, 5, 10, and 30 mg kg−1, i.e., Cd-0, Cd-5, Cd-10, and Cd-30, respectively) and three remediation measures (control, BC addition, and CGR cultivation) was set up to measure available soil Cd (ACd), soil physicochemical properties, GHG emissions, and plant Cd accumulations. The results demonstrated that ACd was significantly reduced by BC via adsorption through surface complexation and by CGR via immobilization through root uptake and sequestration. CGR decreased ACd by 46.2% and 41.7% under mild and moderate Cd contamination, respectively, while BC reduced ACd by 8.9% under severe contamination. In terms of GHG emissions, CGR increased cumulative CO2 by 83.4% in Cd-10 soil and 53.8% in Cd-30 soil, whereas BC significantly lowered N2O emissions by 22.1% in Cd-5 soil. Mantel analysis revealed strong correlations between ACd and key carbon and nitrogen indicators, which mediate the bioavailability of Cd. Therefore, CGR cultivation is better suited to mild-to-moderate contamination given its high removal efficiency, while BC amendment is targeted at severe contamination by stabilizing Cd and mitigating N2O. This provides a scientific basis for the remediation of Cd-contaminated soils.

1. Introduction

Cadmium (Cd) is a highly toxic metallic element characterized by high mobility, long persistence, and wide-ranging environmental impacts. It is listed as one of the globally prioritized pollutants for control [1]. Its primary sources include natural processes and human activities, such as applying cadmium-containing pesticides and fertilizers in agriculture [2]. In China, the situation of Cd pollution is particularly severe. According to the 2014 National Soil Pollution Status Survey Bulletin, the exceedance rate of Cd in arable soils reached approximately 7%, the highest among all heavy metal pollutants [3]. Notably, southern Chinese provinces form the core of Cd pollution, with areas like Guangxi, Hunan, Fujian, and Jiangxi exceeding safe cadmium limits by 3 to 4 times [4]. Therefore, the remediation of Cd-contaminated soil is now a major focus of national and international research. Strategies widely under investigation include soil remediation technologies (e.g., phytoremediation) and amendments (e.g., biochar), which aim to lower Cd bioavailability and secure agricultural safety [5].

Soil Cd contamination not only poses a potential threat to human health but also contributes to increased greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, thereby affecting agricultural production and ecosystem stability [6]. In global GHG emissions, carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O) are widely recognized as the major GHGs that cause global warming [7]. Agricultural soils account for approximately 60% of anthropogenic N2O emissions [8]. Therefore, soil processes play a crucial role in the overall greenhouse effect. The long-term Emission Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR) further shows that global emissions of CO2, CH4, and N2O have continued to rise from the early 1970s to 2022. Over the 40-year period from 1980 to 2020, total anthropogenic N2O emissions increased by 40%, indicating that N2O is an important GHG in addition to CO2 [9]. Meanwhile, the annual average growth rate of global atmospheric CO2 amounts has reached 2.2% since 1960 [10]. Although existing research indicates that Cd contamination can indirectly increase GHG emissions by stressing soil microbes and disrupting carbon and nitrogen cycles, the precise regulatory mechanisms remain unclear [11,12].

Traditional soil Cd remediation methods are often costly and have limited efficacy. Therefore, developing economical and effective soil Cd remediation technologies is particularly critical [13]. Biochar is a stable, black, carbonaceous material produced through the pyrolysis of biomass at 300–700 °C in an oxygen-deficient environment [14]. Relevant studies have shown that biochar has a certain adsorption capacity for heavy metals (Cd, Hg, Pb, Cu, Ni, Zn, As, Cr) [15]. Biochar benefits from abundant raw material sources and low production costs [16]. Moreover, its high specific surface area, porous structure, and abundance of surface functional groups enable the effective reduction in soil Cd bioavailability and mobility via adsorption and complexation [17]. Relevant data demonstrate that biochar application significantly decreases soil-available Cd and plant Cd accumulation, with average reductions of 52% and 38%, respectively [18]. Functional groups on the biochar surface can form stable complexes with Cd, which further diminishes Cd mobility and bioavailability [19]. Researchers found that a 3% (w/w) application of rapeseed straw biochar significantly altered soil Cd speciation, thereby reducing its mobility [20]. Other studies have also indicated that biochar can improve soil pH, pore structure, and microbial activity, which in turn enhances soil quality and increases crop yields [21]. In addition, biochar can mitigate GHG emissions and strengthen soil carbon-nitrogen retention by regulating soil enzyme activity and the abundance of microbial functional genes [22,23]. Thus, biochar is a soil amendment and Cd-contamination remediation material with great application prospects.

Solidago canadensis (henceforth S. canadensis), native to the eastern and north-central regions of North America, is a perennial herb of the genus Solidago (Asteraceae family) that thrives under moderate-temperature conditions. It is recognized as one of the most destructive invasive plant species [24,25,26]. Owing to its rapid growth, broad adaptability, and strong reproductive capacity, S. canadensis readily forms monodominant stands, outcompeting native plants, altering vegetation structure, and ultimately threatening biodiversity and ecosystem stability [27,28]. As an invasive plant with strong environmental adaptability and vigorous growth, S. canadensis exhibits strong adsorption and bioaccumulation capacities for heavy metals in the soil. Research has demonstrated that S. canadensis is capable of adsorbing significant quantities of copper (Cu) from soil, which highlights its high potential as a species for phytoremediation of soils polluted by heavy metals [29]. Biochar, which possesses functions of carbon sequestration, emission mitigation, and heavy metal adsorption, is widely used as a soil amendment [30,31].However, whether interactions between the growth characteristics of S. canadensis and biochar can be utilized for the remediation of Cd-contaminated soil remains a scientific question that requires clarification. Against this background, this study proposed the following questions: (1) How does the remediation efficacy of S. canadensis compare with that of biochar across a gradient of soil Cd pollution levels? (2) How do applications of S. canadensis and biochar contrast in their impacts on soil CO2 and N2O emissions under varying Cd pollution levels?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Site

The experimental site is located in the Agricultural Science and Technology Park of Jiangxi Agricultural University, Nanchang, Jiangxi, China (115°49′52.49″ E, 28°46′17.28″ N). It has a mid-subtropical warm-humid monsoon climate, with an average annual temperature ranging from 16.3 °C to 19.5 °C. The maximum summer temperature can reach 40 °C, while the minimum winter temperature can drop to -10 °C. The annual precipitation ranges from 1341 mm to 1943 mm, with an uneven distribution throughout the year; the majority of precipitation occurs from April to June.

2.2. Experimental Materials

2.2.1. Preparation of Biochar

Camellia oleifera is widely cultivated in China, with large quantities of fruit shells discarded as waste after oil extraction. Converting these fruit shells into biochar not only enables efficient resource recycling but also significantly alleviates waste disposal pressure. Here, fruit shells were collected, washed to remove debris, and air-dried in a well-ventilated location. After drying, the shells were crushed using a high-speed rotary pulverizer and passed through a 2 mm sieve to ensure uniform particle size. Subsequently, the sieved shell powder was placed into a crucible, which was then transferred to a muffle furnace for pyrolysis at 600 °C for 1 h under oxygen-limited conditions. After pyrolysis, the resulting biochar (pH: 9.49 ± 0.33, TC: 752.87 ± 3.50 g kg−1,TN: 5.13 ± 0.81 g kg−1) was allowed to cool naturally to room temperature, re-sieved through a 2 mm sieve, and finally stored in a sealed container for subsequent experimental use [32].

2.2.2. Soil Sample Preparation

Soils used in this experiment were collected from farmland in the Science and Technology Park of Jiangxi Agricultural University. A random multi-point sampling method was adopted, with a soil sampling depth of 0–20 cm to ensure the representativeness of soil samples. After collection, stones, plant and animal residues, and plant roots were removed, followed by passing the soil through a 2 mm sieve and thorough mixing. To establish soil environments with different Cd contamination levels, 1.5 kg of homogenized soil was used per sample. Specifically, 0 mL, 7.5 mL, 15 mL, and 45 mL volumes of the 1000 mg L−1 CdCl2 stock solution were added to the soil samples, respectively. Deionized water was then supplemented to bring the total liquid volume to 45 mL, resulting in soil samples with four target Cd concentrations (0, 5, 10, and 30 mg kg−1) [33]. These Cd-spiked soils were thoroughly mixed, then sealed and incubated in the dark for 70 days to allow Cd ions to be evenly distributed and to better simulate actual field soil conditions. The stabilized soils were subsequently used for pot experiments. Soil background values are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic physical and chemical properties of test soil (means ± se). TC: total carbon; TN: total nitrogen; DOC: dissolve organic carbon; DON: dissolve nitrogen; NH4+-N: ammonium nitrogen; NO3−-N: nitrate nitrogen; ACd: available cadmium, the same below.

2.2.3. Selection of Test Plants

Seedlings of the test plant S. canadensis were collected from wild populations in Jiangxi Province. To ensure consistency, we selected healthy, current-year seedlings with a uniform height of approximately 18 cm for use in the experiments. After collection, the seedlings were promptly transported to the experimental site, where the soil adhering to the roots was removed and the seedlings were rinsed thoroughly. They were then placed in a cool and well-ventilated area for later use.

2.3. Experimental Design

A pot experiment was conducted using a full factorial experimental design with two factors: (i) Cd concentration and (ii) soil remediation measures. The experiment was conducted under natural, well-ventilated conditions. Plants were watered regularly to maintain soil moisture at 60–70% of field capacity. Cd concentrations were set at 0 mg kg−1 (Cd-0, None), 5 mg kg−1 (Cd-5, Mild), 10 mg kg−1 (Cd-10, Moderate), and 30 mg kg−1 (Cd-30, Severe). The three soil remediation measures including control (CK), fruit shell biochar (BC), and S. canadensis planting (CGR). Each remediation measures combination had 8 replications, resulting in a total of 4 × 3 × 8 = 96 pots, among which, 4 replicates per combination were allocated to gas sampling, and the remaining 4 to soil sampling. Uniform black plastic pots were used, with a 16 cm top diameter, 11 cm bottom diameter, and 18.1 cm height. Each pot was filled with 1.5 kg of pre-treated, Cd-spiked soil (stabilized prior to use) corresponding to the assigned Cd concentration. For the BC remediation measure, Camellia shell biochar was mixed into the Cd-spiked soil at a rate of 20 g kg−1 soil before potting. The CGR remediation measure involved planting a single S. canadensis seedling in each pot after soil preparation. In contrast, the CK pots contained soil only, with no plant or biochar amendments. The experiment began after the transplanted S. canadensis plants had established, as indicated by new leaf growth in at least 90% of individuals, and continued for a 150-day period.

2.3.1. Gas Sampling and Analysis

Soil N2O and CO2 emissions were measured using an opaque static chamber (21.1 cm diameter × 66.9 cm height), which featured an open-bottomed cylindrical design. The outer surface of the cylindrical chamber was wrapped with metal foil to minimize the impact of solar radiation during gas sampling. Two holes were made in the chamber: one at the top, and another 23 cm above the chamber bottom on the side. The top hole was fitted with a thermometer (inserted through a rubber stopper) for temperature measurement, while the side hole was connected to an internal hose (leading to the chamber top) and an external three-way valve. Gas samples were collected once every 7 days under clear weather conditions. To ensure airtightness during sampling, an appropriate volume of water was added to a tray, a base was placed inside the tray, and the potted plant was positioned on the base; the static chamber was then placed over the pot, Throughout the entire gas-sampling period, the chamber remained undisturbed to maintain an airtight seal. At 0, 10, 20, and 30 min after chamber placement, a 60 mL plastic syringe was used to extract gas, and the corresponding chamber temperature was recorded at each time point. Pressure and temperature fluctuations inside the chamber were corrected in the calculation. Four gas samples were collected per pot, sealed in the syringe, and promptly transported to the laboratory for concentration analysis via gas chromatography (Agilent 7890B, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) and an electron capture detector (ECD). During gas sampling, atmospheric temperature, soil temperature (at 10 cm depth), and soil moisture (measured using a Hydro-Sense sensor, Campbell Scientific, Logan, UT, USA) were also recorded. The calculation equations for soil N2O and CO2 emission fluxes are as follows [34]:

In the formula, F represents the emission fluxes of N2O and CO2 (μg m−2 h−1); P denotes the atmospheric pressure under standard conditions (pa); V and A are the volume (m3) and the base area (m2) of the static chamber, respectively; R is the universal gas constant, with a fixed 8.314 J·mol−1·k−1; dc/dt is the rate of change in gas concentration inside the chamber with time per unit time. over time; T represents the absolute temperature during the sampling process (K); M is the relative molecular mass. The calculation formulas for the cumulative emissions of soil N2O and CO2 are as follows [35]:

In the formula, M represents the cumulative gas emissions (CO2 cumulative emissions are measured in mg m−2, N2O cumulative emissions in μg m−2); F represents the gas emission flux (CO2 emission flux is measured in mg m−2 h−1, N2O gas e mission flux is in μg m−2 h−1); (Fi+1 + Fi) represents the sum of the gas emission fluxes from two consecutive samplings at the same sampling point, where i represents the ith gas sample collection, and (ti+1 − ti) represents the number of days between two consecutive samplings.

2.3.2. Soil Sampling and Analysis

Soil samples were collected once a month for a total of five months. For each treatment, three soil cores (using a 1.5 cm-diameter small soil auger) were collected from three random points in each of the four replicate pots; these cores were then mixed into a composite sample, resulting in a total of 48 samples. Plant roots and gravel impurities were removed from the soil samples, which were subsequently passed through a 2 mm sieve, a portion of the samples was stored at 4 °C for refrigeration, while the remainder was air-dried at ambient temperature, and preserved for no more than 7 days prior to chemical analysis. Before the analysis, for analyses conducted on fresh soil, the moisture content was first determined and used to convert all results to a dry-soil basis; subsequently, each assay was performed using an equivalent dry-mass of fresh soil to ensure consistency. Soil pH was measure by a pH meter (PH-3E). Total carbon (TC), dissolved organic carbon (DOC), and dissolved organic nitrogen (DON) in the soil were determined using a total organic carbon analyzer (Analytik Jena, Multi N/C 3100, Jena, Germany) [36]. For soil total nitrogen (TN) and ammonium nitrogen (NH4+), an automatic discrete chemical analyzer (Smart Chem 200, Westco, Rome, Italy) was employed [37]. Nitrate nitrogen (NO3−) was tested via a flame photometer. Available cadmium (ACd) was extracted following the BCR method (European Community Bureau of Reference), and its concentration was analyzed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS); soil samples were tested both at the start and end of the experiment. After the experiment, the ACd concentrations in the roots, stems, and leaves of plant samples were determined, and their absorption capacity was calculated using the following formula:

In the formula, Q represents the Cd absorption of plant (mg); C represents the cadmium concentration in plants (mg kg), and B represents the plant biomass (mg).

2.3.3. Statistical Analysis

Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine the effects of remediation measures, Cd concentration, and their interaction on each index. Normality and homogeneity were conducted on all measured indices to ensure that the statistical analysis prerequisites were met. For significant differences, post hoc multiple comparisons (Duncan method) were conducted to compare specific differences among means. Correlations among ACd and soil physicochemical properties were elucidated by Mantel analysis. All statistical analyses were completed using SPSS 27.0 and R.4.4.3 software.

3. Results

3.1. Soil Physicochemical Properties

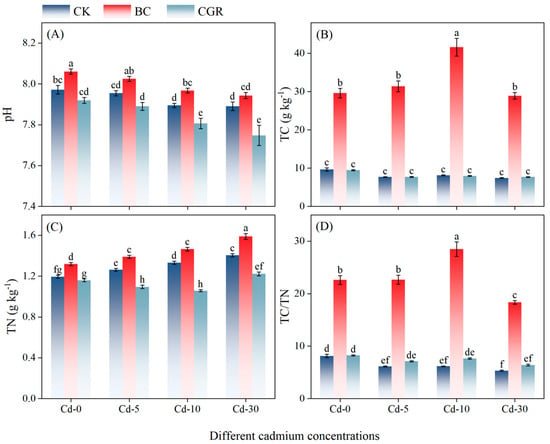

Both remediation measures and Cd concentrations exerted extremely significant effects on TC and TN (p < 0.001; Table 2). Under different Cd concentrations, the application of BC significantly increased the content of TC (Figure 1B), with an increase of 207.45% to 412.3% compared to the CK, and the TN content of the BC was also higher than that of the CK and CGR (Figure 1C).

Table 2.

The effects of remediation measures and pollution levels on soil properties in ANOVAs. Remediation measures: control (CK), biochar (BC), and S. canadensis planting (CGR); Cd: 0 (Cd-0), 5 (Cd-5), 10 (Cd-10), and 30 (Cd-30) mg kg−1, respectively. F with p values indicated by asterisks. ***, p < 0.001.

Figure 1.

The effects of remediation of Cd-contaminated soil under different remediation measures on soil pH (A), TC (B), TN (C), TC/TN ratio (D). Different letters indicate significant differences. CK: control; BC: biochar; CGR: S. canadensis cultivation. Cd-0: 0 mg kg−1; Cd-5: 5 mg kg−1; Cd-10: 0 mg kg−1; Cd-30: 30 mg kg−1, the same below.

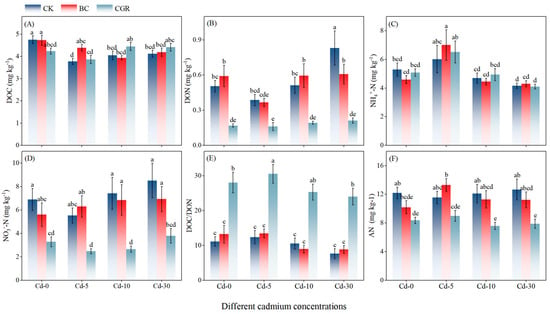

DOC exhibited a declining trend with increasing Cd concentrations (Figure 2A). At Cd-10 and Cd-30 levels, DOC content was significantly higher in the CGR than in the BC. For DON (Figure 2B), concentrations in the CGR were lower than in the CK across all Cd levels. In the BC treatment, DON was 17.3% higher than in CK at Cd-0, but comparable to CK at Cd-30. Regarding inorganic nitrogen, NO3−-N content in the BC treatment exceeded that in CGR by 154.7% at Cd-5 and 159.1% at Cd-10 (Figure 2D). Meanwhile, NH4+-N in BC was 16.3% higher than in CK at Cd-5 (Figure 2C). For available nitrogen (AN; Figure 2F), no significant difference was observed between CGR and CK across Cd concentrations, while AN content in BC was higher than in CGR. Finally, the CGR treatment elevated the DOC/DON ratio compared to both BC and CK at all Cd levels (Figure 2E). This ratio peaked at Cd-5, where it was 147.3% higher than in CK.

Figure 2.

The effects of remediation of Cd-contaminated soil under different remediation measures on soil DOC (A), DON (B), NH4+-N (C), NO3−-N (D), DOC/DON ratio (E), and AN (F). Different letters indicate significant differences.

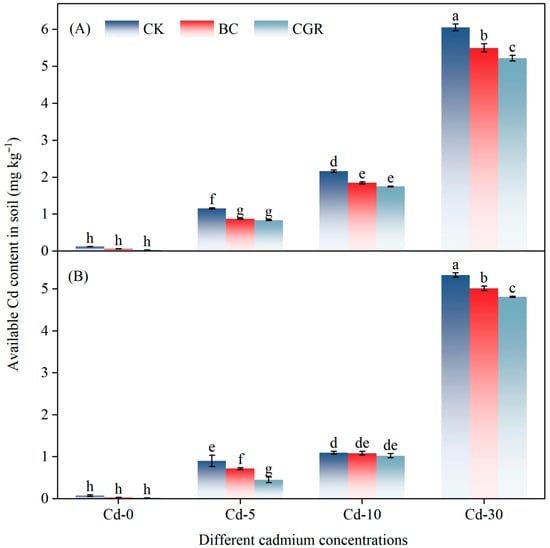

3.2. Soil-Available Cadmium

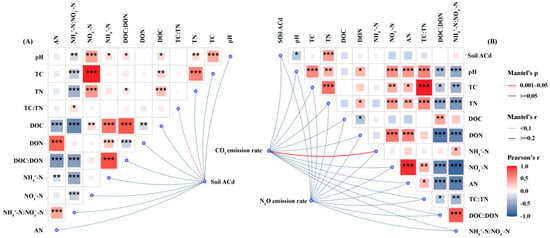

Both remediation measures and cadmium concentrations had a highly significant effect on ACd in the soil (p < 0.001; Table 2). Under Cd-5 and Cd-10, the ACd content in soils treated with BC or CGR was lower than that in the CK Under Cd-30, at the experiment initiation (Figure 3A), BC reduced soil ACd by 9.8% relative to CK, while CGR reduced it by 13.8%; at the experiment termination (Figure 3B), BC and CGR decreased ACd by 5.9% and 9.7%, respectively, compared with CK. ACd was significantly and positively correlated with several soil physicochemical properties (Figure 4A). Among these properties, the Mantel tests for TC and TN with ACd reached an extremely significant level (p < 0.001), with Pearson correlation coefficients close to 1.0. DOC and DON were also extremely significantly and positively correlated with ACd (p < 0.001). In addition, NH4+-N and AN also showed an extremely significant correlation with ACd (p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

The effects of remediation of Cd-contaminated soil under different remediation measures on soil-available cadmium (at the initial stage of the experiment, (A)) and (at the end of the experiment, (B)). Different letters indicate significant differences.

Figure 4.

Mantel test and Pearson correlations between soil-available Cd (A), GHG emission rates (N2O and CO2) (B), and measured soil variables across all remediation measures and Cd contamination levels. The soil variables include basic physicochemical properties, carbon and nitrogen components, and inorganic nitrogen forms. Line width and color in the network diagram correspond to the strength and significance of the correlations, respectively. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001.

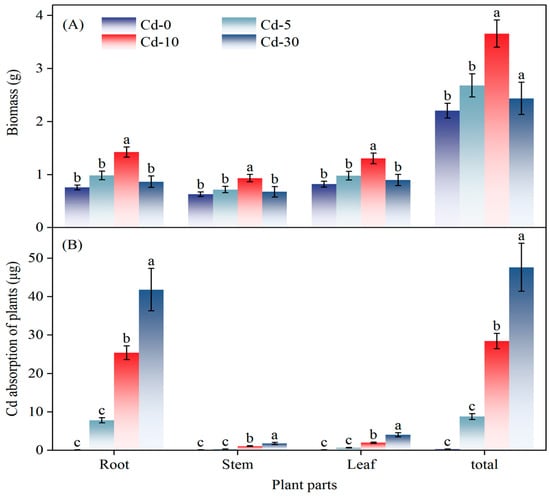

3.3. Plant Cadmium Content

Under Cd-10 conditions, CGR produced significantly greater total and root biomass compared to other treatments, though no inter-treatment differences were observed in stem or leaf biomass (Figure 5A). Cd uptake in CGR plants increased significantly with soil Cd concentration, peaking at the Cd-30 level. Root Cd content at Cd-30 was 64.6% higher than at Cd-10. Roots served as the primary site of accumulation: per-plant root Cd uptake reached 41.8 μg under Cd-30, exceeding all other treatments. Across all Cd levels, stem and leaf Cd absorption remained lower than in the roots (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Effect of Cd-contaminated level on (A) biomass production and (B) Cd accumulation in different tissues of S. canadensis. Different letters indicate significant differences.

3.4. Effect on Soil GHG

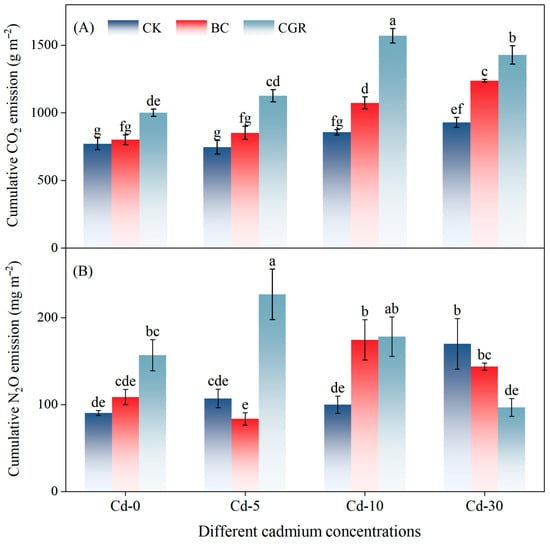

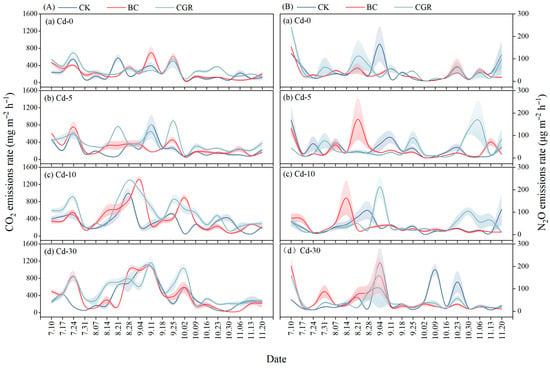

3.4.1. CO2 Emission

CO2 emissions were significantly influenced by remediation measures, Cd concentration, and their interaction (p < 0.001; Table 3). The BC reduced the CO2 emission rate, whereas CGR significantly increased it—an effect that intensified with higher Cd contamination (Figure A1A). Under moderate and severe contamination, cumulative CO2 emissions in the CGR treatment were 83.4% and 53.8% higher than in the CK, respectively, and were also significantly greater than in the BC (Figure 6A).

Table 3.

The effects of remediation measures, cadmium (Cd) pollution level, and their interaction on greenhouse gas emissions in ANOVAs. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001.

Figure 6.

Effects of different remediation measures on cumulative emissions of soil CO2 (A) and N2O (B). Different letters indicate significant differences.

3.4.2. N2O Emission

Cumulative N2O emissions were significantly influenced by remediation measures (p < 0.001), Cd concentration (p < 0.05), and their interaction (p < 0.001) (Table 3). In Cd-30 soils, the BC increased the N2O emission rate, while the CGR inhibited N2O emissions in Cd-10 soils (Figure A1B). At Cd-5, cumulative N2O emissions in the CGR were 172.3% higher than those in the BC and 111.2% higher than those in the CK. At Cd-10, cumulative N2O emissions in the CGR and BC were 78.4% and 74.8% higher than those in the CK, respectively. The CGR promoted N2O emissions at Cd-5 but inhibited them at Cd-10 and Cd-30; in contrast, the BC generally inhibited N2O emissions or had no significant effect on them (Figure 6B).

The N2O emission rate positively correlated with soil pH, TC, TN, NO3−-N, AN, TC/TN ratio, DOC/DON ratio, and NH4+-N/NO3−-N ratio (p < 0.001), and positively correlated with dissolved DON and NH4+-N (p < 0.05). Additionally, the spatial distribution of N2O emission rates was significantly coupled with NO3−-N (p < 0.001–0.05). The CO2 emission rate correlated positively with NO3−-N, AN, TC/TN ratio, DOC/DON ratio, and NH4+-N/NO3−-N ratio (p < 0.01), with an extremely strong correlation with NO3−-N (p < 0.001; Figure 4B).

4. Discussion

4.1. Remediation Effects of CGR and BC on Cd-Contaminated Soil

Heavy metal Cd contamination seriously threatens soil and food security, making effective remediation materials a key research focus. CGR shows substantial remediation potential across Cd-contaminated soils, consistent with Fu et al. [38] and further validates the application value of invasive plants in heavy metal remediation [15]. Its mechanism relies on rhizosphere microenvironment regulation and enrichment, with stronger efficacy in severely polluted soils [39], confirming our initial hypothesis. Under Cd-10 and Cd-30 levels, DOC was significantly higher in CGR soils than in BC soils, likely due to root-secreted low-molecular-weight organic acids that elevate DOC and enhance Cd immobilization [40]. Meanwhile, CGR’s DON uptake enhances rhizosphere microbial activity, promoting Cd transformation and immobilization. This finding aligns with the theory of “rhizodeposition-driven rhizosphere nutrient cycling” [41].

The remediation advantage of CGR in Cd-contaminated soil stems from its “root enrichment–low above-ground translocation” trait [42]. Cellulose and pectin carboxyl groups in CGR root cell walls intercept Cd2+ via ion exchange, and cortical Casparian strips physically block Cd2+ transport to the xylem—a mechanism experimentally confirmed in multiple crops [43,44]. A small fraction of Cd2+ entering the cytoplasm forms stable Cd-phytochelatin (Cd-PC) complexes with PCs, which ABCC-type transporters pump into vacuoles for compartmentalization [45]. Vacuolar compartmentalization reduces Cd2+ toxicity and facilitates long-term immobilization. Consequently, Cd levels in CGR shoots remain minimal, preventing food chain transfer and allowing for continuous sequestration. However, the long-term field stability and growth-cycle dynamics of CGR remediation still require verification through extended field observation. This study’s validation of CGR’s remediation efficacy aligns with Richardson et al.’s view that invasive plants are potential remediation materials owing to their stress tolerance and enrichment capacity [46].

In contrast to CGR’s bioremediation mechanism, BC remediates Cd-contaminated soil through the dual effects of physicochemical passivation and soil improvement. This synergistic action lowers Cd bioavailability while enhancing soil fertility, a finding consistent with existing research [47]. This study shows BC significantly increases soil carbon and nitrogen pools: under different Cd contamination levels, its TC content is notably higher than CK, benefiting from its aromatic stable carbon skeleton and well-developed porous structure that reduce the mineralization loss of soil organic carbon, with a high specific surface area of 246.18 m2 g−1 further strengthening the carbon sequestration effect [48]. This is also confirmed by Chen et al., who reported that BC reduces organic carbon decomposition and loss by increasing soil aromatic carbon ratio and aggregate stability [30]. Meanwhile, BC electrostatically adsorbs NH4+-N via surface negative charges and may activate urease, significantly increasing TN and AN content—consistent with Ren et al.’s reported nutrient enhancement [49]. Enhanced carbon and nitrogen pools reduce nutrient leaching and improve soil physicochemical properties, creating favorable conditions for Cd passivation [50]. BC reduces soil-available Cd mainly through three mechanisms: (1) its porous structure physically intercepts Cd2+ to prevent soil matrix infiltration; (2) surface functional groups (e.g., -OH, -COOH) form stable complexes with Cd2+ via coordination bonds to strengthen adsorption; and (3) increased AN promotes NH4+ and Cd2+ competition for adsorption sites, further lowering Cd bioavailability [51]. However, this study’s short-term observations limit our assessment of biochar aging and long-term Cd fixation; extended field trials are needed to systematically evaluate remediation sustainability.

4.2. Effects of CGR and BC on CO2 and N2O Emissions

For the second hypothesis, the driving patterns of GHG emissions differed markedly between CGR and BC. In alignment with our experimental hypothesis, CGR significantly promoted soil CO2 emissions, with the emission levels increasing alongside higher cadmium concentrations. This positive concentration-dependent stimulatory effect further corroborates the global consensus that invasive plants generally enhance soil CO2 emissions [52]. This phenomenon stems from two mechanisms: first, CGR roots directly release CO2 via respiration and secrete low-molecular-weight organic acids to boost rhizosphere DOC, supplying ample substrates for microbial carbon mineralization [41]. Second, high Cd stress elevates CGR’s energy demand for Cd enrichment and detoxification, thus increasing root respiration rates [53]. The findings indicate that plant metabolic compensation demand increases with Cd stress intensity, aligning with previous evidence that heavy metal stress stimulates plant respiratory carbon emissions [54].

CGR regulates soil nitrogen cycling and thereby modulates N2O production [55]. In this experiment, its effect on N2O emissions showed a low-promotion, high-inhibition pattern with rising Cd concentrations, with AN dynamics as the core regulator. This pattern aligns with our hypothesis that CGR differentially affects GHG emissions. In Cd-5 soil, CGR significantly increased N2O emissions, likely via root exudates stimulating nitrifying and denitrifying bacteria—consistent with findings that invasive plants affect nitrogen transformation through rhizosphere microecology regulation [28,56]. However, at Cd-10 and Cd-30, enhanced AN uptake by CGR roots reduced soil NH4+-N and NO3−-N levels; below the microbial demand threshold, nitrification and denitrification were inhibited, cutting N2O emissions. Moreover, excessive Cd accumulation in CGR roots might suppress nitrogen-cycling microbial activity [57]. Overall, CGR’s regulatory effect on N2O emissions shifts from promotion to inhibition with increasing Cd concentrations, primarily due to root-exudate-mediated AN regulation and direct microbial inhibition by Cd stress. This highlights invasive plants’ environmental dependence regarding soil GHG emissions [52,58].

BC application regulates GHG emissions by modifying soil physicochemical properties, microbial community structure, and nutrient cycling [59]. In Cd-contaminated soils, BC remediation enhances short-term but strongly inhibits long-term CO2 emission rates; yet, cumulative CO2 emissions in BC treatments rise with increasing soil Cd concentrations, while remaining generally lower than those in the CGR remediation measure. This phenomenon links directly to Cd-driven shifts in carbon pool stability: BC is rich in aromatic carbon skeletons with low mineralization potential, which resist microbial degradation and protect soil organic carbon (SOC). Additionally, BC’s porous surface physically adsorbs DOC and particulate organic carbon (POC), reducing labile carbon availability for microorganisms and thus inhibiting SOC mineralization and CO2 emissions [60,61]. Notably, BC’s carbon sequestration effect is most pronounced under mild-to-moderate Cd contamination, while its CO2 emission inhibition weakens with rising Cd levels. This may be attributed to two factors: under high Cd stress, Cd-tolerant microorganisms secrete enzymes that partially degrade BC-adsorbed labile organic carbon, integrating it into mineralization; meanwhile, high Cd concentrations damage oxygen-containing functional groups (e.g., -OH, -COOH) on BC surfaces, lowering adsorption capacity [62]. In summary, the data show that BC’s efficacy as a carbon sink diminishes with higher Cd concentrations, consistent with the broader finding that elevated heavy metals disrupt carbon sequestration mechanisms via multiple pathways [63].

The impact of BC on N2O emissions was characterized by promotion at high Cd concentrations and no significant effect at low-to-medium levels, an outcome directly driven by Cd-regulated nitrogen species transformation. When Cd stress is moderate or mild, low ACd content enables BC to adsorb NH4+-N and NO3−-N via surface electrostatic attraction, which helps maintain soil nitrogen stability [64]. Additionally, BC raises soil pH and inhibits denitrifying bacteria activity; these two factors collectively lead to unchanged N2O emissions [65]. Conversely, under high Cd stress, ACd content rises sharply, and BC markedly accelerates N2O emissions. The promotion may be attributed to a dual pathway: (1) competitive displacement of adsorbed NH4+-N by Cd2+ on BC surfaces, which enhances nitrification substrate availability [66], and (2) inhibition of the N2O reductase enzyme under high Cd stress, blocking the reduction of N2O to N2 and causing its accumulation [67]. The impact of BC on N2O emissions was characterized by promotion at high Cd concentrations and no significant effect at low-to-medium levels, an outcome directly driven by Cd-regulated nitrogen species transformation. This study clarified the differential effects of S. canadensis and biochar on soil CO2 and N2O emissions across the Cd contamination gradient. However, as it did not include other GHGs, more comprehensive monitoring is needed in the future to systematically evaluate the climate impact of the remediation strategies.

5. Conclusions

The remediation performance of BC and CGR is highly dependent on Cd concentration. BC proves more effective under severe contamination (Cd-30), reducing ACd by 8.9% via increases in TC, DOC, and pH. Conversely, CGR shows a more targeted effect at lower concentrations, achieving substantial ACd reductions of 46.2% and 41.7% at Cd-5 and Cd-10, respectively, by modulating AN and DON. For GHG regulation, CGR increases cumulative CO2 emissions by 83.4% (Cd-10) and 53.8% (Cd-30), while BC inhibits N2O by 22.1% (Cd-5) and does not elevate CO2 across all levels, with better environmental potential. For balanced and effective remediation, CGR is advised for mild to moderate Cd contamination (≤10 mg kg−1), and BC for severe pollution (30 mg kg−1). This study not only offers a new direction for the resource utilization of invasive plants but also provides a quantitative basis and technical support to advance green remediation practices for Cd-contaminated soil. Based on the limitations of this study, future research should focus on the long-term field validation of these strategies, explore their synergistic effects in integrated applications, and monitor and assess multiple GHG emissions to inform optimal environmental outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.N., X.L. and L.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.N.; formal analysis, Y.Y., W.N., Y.H. and J.B.; investigation, Z.Y., W.L., L.X., X.X., Y.Z., Z.Z. and Q.Y. (Qingye Yu); writing—review and editing, S.W., Q.Y. (Qin Ying), N.W. and L.Z.; supervision, L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

The effects of different remediation measures and cadmium concentration treatments on the dynamic changes in soil CO2 (A) and N2O (B) emission rates in cadmium-contaminated soil. The shaded area indicates the standard error of the mean.

References

- Sun, S.; Fan, X.; Feng, Y.; Wang, X.; Gao, H.; Song, F. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Influence the Uptake of Cadmium in Industrial Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). Chemosphere 2023, 330, 138728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Li, Y.; Ding, L.; Ye, Y.; Tang, F.; Wang, F.; Bao, H.; Jiang, Q.; Peng, W.; Zhang, L.; et al. Regulation of Cadmium Accumulation and Tolerance by Receptor-Like Kinase OsSRK and Putative Ligand OsTDL1B in Rice. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, G.; Niu, Z.; Yu, J.; Li, Z.; Ma, J.; Xiang, P. Soil Heavy Metal Pollution and Food Safety in China: Effects, Sources and Removing Technology. Chemosphere 2021, 267, 129205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Yu, L.; Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Liu, T. Review of Soil Heavy Metal Pollution in China: Spatial Distribution, Primary Sources, and Remediation Alternatives. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 181, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elik, Ü.; Gül, Z. Accumulation Potential of Lead and Cadmium Metals in Maize (Zea mays L.) and Effects on Physiological-Mor phological Characteristics. Life 2025, 15, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drabesch, S.; Planer-Friedrich, B.; Kappler, A.; Fendorf, S.; Muehe, E.M.; León-Ninin, J.; Lezama-Pacheco, J. Coupled Cadmium and Climatic Stress Increase Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Emissions. In Goldschmidt2021 Abstracts; European Association of Geochemistry: Aubière, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, B.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. Reshaping Agriculture Eco-Efficiency in China: From Greenhouse Gas Perspec tive. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 172, 113268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, R.; Du, Y.; Han, H.; Guo, S.; Song, X.; Ju, X. Significant Increases in Nitrous Oxide Emissions under Simulated Extreme Rainfall Events and Straw Amendments from Agricultural Soil. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 246, 106361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens-Maenhout, G.; Crippa, M.; Guizzardi, D.; Muntean, M.; Schaaf, E.; Dentener, F.; Bergamaschi, P.; Pagliari, V.; Olivier, J.G.J.; Peters, J.A.H.W.; et al. EDGAR v4.3.2 Global Atlas of the Three Major Greenhouse Gas Emissions for the Period 1970–2012. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 959–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Zhu, B.; Davis, S.J.; Ciais, P.; Guan, D.; Gong, P.; Liu, Z. Global Carbon Emissions and Decarbonization in 2024. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Lin, J.; Wang, X.; Shi, J.; Dahlgren, R.A.; Xu, J. Dynamics of Soil Microbial N-Cycling Strategies in Response to Cadmium Stress. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 14305–14315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Yang, S.; Pang, Q.; Abdalla, M.; Karbin, S.; Qi, S.; Hu, J.; Qiu, H.; Song, X.; Smith, P. Metagenomic Insights into the Influence of Soil Microbiome on Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Paddy Fields under Varying Irrigation and Fertilisation Regimes. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 393, 127129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, P.D.T.; Nguyen, H.T.; Thi, K.V.; Quang, P.N. Insights into the Remediation of Cadmium-Contaminated Vegetable Soil: Co-Application of Low-Cost by-Products and Microorganism. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Optimizing Biochar Production: A Review of Recent Progress in Lignocellulosic Biomass Pyrolysis. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 148–172. [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Zhuang, S.; Wang, J. Adsorption of Heavy Metals by Biochar in Aqueous Solution: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 968, 178898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Chen, L.; Hu, P.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, H.; Wang, D.; Lu, X.; Mi, B. Comparison of Properties, Adsorption Performance and Mechanisms to Cd(II) on Lignin-Derived Biochars under Different Pyrolysis Temperatures by Microwave Heating. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 25, 102196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, P.; Li, L.; Zhou, X.; Huang, J.; Ye, J.; Liu, X.; Xie, J.; Wang, Z. Modification of Arsenic and Cadmium Species and Accumu lation in Rice Using Biochar-Supported Iron-(Oxyhydr)Oxide and Layered Double Hydroxide: Insight from Fe Plaque Conversion and Nano-Bioassembly in the Root. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 494, 152847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Geng, N.; Hou, X.; Wang, H.; Pan, H.; Yang, Q.; Lou, Y.; Zhuge, Y. Potassium Permanganate-Hematite-Modified Biochar Enhances Cadmium and Zinc Passivation and Nutrient Availability and Promotes Soil Microbial Activity in Heavy Metal-Contaminated Soil. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 376, 124469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Liu, L.; Sun, J.; He, X.; Li, Z.; Tang, J. Iron-Silicon Modified Biochar for Remediation of Cadmium/Arsenic Co-Contam inated Paddy Fields: Is It Possible to Kill Two Birds with One Stone? J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 494, 138702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Hu, H.; Fu, Q.; Li, Z.; Xing, Z.; Ali, U.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Y. Remediation of Pb, Cd, and Cu Contaminated Soil by Co-Pyrolysis Biochar Derived from Rape Straw and Orthophosphate: Speciation Transformation, Risk Evaluation and Mechanism Inquiry. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 730, 139119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koprivica, M.; Petrović, J.; Simić, M.; Dimitrijević, J.; Ercegović, M.; Trifunović, S. Characterization and Evaluation of Biomass Waste Biochar for Turfgrass Growing Medium Enhancement in a Pot Experiment. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; De Almeida Moreira, B.R.; Bai, Y.; Nadar, C.G.; Feng, Y.; Yadav, S. Assessing Biochar’s Impact on Greenhouse Gas Emis sions, Microbial Biomass, and Enzyme Activities in Agricultural Soils through Meta-Analysis and Machine Learning. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 963, 178541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasar, B.J.; Agarwala, N. Unravelling the Role of Biochar-Microbe-Soil Tripartite Interaction in Regulating Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Budget: A Panacea to Soil Sustainability. Biochar 2025, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Liu, S.; Liu, X.; Zou, J.; Siemann, E. Perennial Forb Invasions Alter Greenhouse Gas Balance between Ecosys tem and Atmosphere in an Annual Grassland in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 642, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kama, R.; Javed, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Iqbal, B.; Diatta, S.; Sun, J. Effect of Soil Type on Native Pterocypsela Laciniata Performance under Single Invasion and Co-Invasion. Life 2022, 12, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likhanov, A.; Oliinyk, M.; Pashkevych, N.; Churilov, A.; Kozyr, M. The Role of Flavonoids in Invasion Strategy of Solidago Cana densis L. Plants 2021, 10, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.-T.; Wang, Y.-F.; Hou, X.-Y.; Du, D.-L.; Li, Z.-Y.; Wang, X.-Y. Solidago canadensis Enhances Its Invasion by Modulating Prokaryotic Communities in the Bulk Soil. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2024, 194, 105881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M.P.; Gu, Z.; van Kleunen, M.; Zhou, X. Invasion Impacts in Terrestrial Ecosystems: Global Patterns and Predictors. Science 2025, 390, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.U.; Qi, S.-S.; Gul, F.; Manan, S.; Rono, J.K.; Naz, M.; Shi, X.-N.; Zhang, H.; Dai, Z.-C.; Du, D.-L. A Green Approach Used for Heavy Metals ‘Phytoremediation’ via Invasive Plant Species to Mitigate Environmental Pollution: A Review. Plants 2023, 12, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Wang, J.; Lv, J.; Liu, Z.; Sun, T.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, Y.-G. Carbon Sequestration Strategies in Soil Using Biochar: Advances, Challenges, and Opportunities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 11357–11372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Xiang, X.; Yu, X.; Dai, J.; Tian, X. Biochar Superior than Straw in Enhancing Soil Carbon Sequestration via Altering Organic Matter Stability and Carbon Cycle Genes in Cd-Contaminated Soil. Environ. Res. 2025, 287, 123128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Fang, H.; Jiang, N.; Feng, W.; Luo, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Hu, D.; Guo, X.; Zhang, L. Biochar Is Comparable to Dicyan diamide in the Mitigation of Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Camellia Oleifera Abel. Fields. Forests 2019, 10, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.H.; Owens, V.N.; Park, S.; Kim, J.; Hong, C.O. Adsorption and Precipitation of Cadmium Affected by Chemical Form and Addition Rate of Phosphate in Soils Having Different Levels of Cadmium. Chemosphere 2018, 206, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; He, C.; Zhong, C.; Zhang, Q.; Yuan, X.; Hu, X.; Deng, W.; Wang, J.; Du, Q.; Zhang, L. Soil N2O Emission in Cinnamomum Camphora Plantations along an Urbanization Gradient Altered by Changes in Litter Input and Microbial Community Composition. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 299, 118876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, B.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L.; Ma, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, W.; Guo, X.; Niu, D.; Siemann, E. Increases in Soil CO2 and N2O Emissions with Warming Depend on Plant Species in Restored Alpine Meadows of Wugong Mountain, China. J. Soils Sediments 2016, 16, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Zheng, L.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Huang, W.; Hu, X.; Guo, X.; et al. Effects of Mixing Biochar on Soil N2O, CO2, and CH4 Emissions after Prescribed Fire in Alpine Meadows of Wugong Mountain, China. J. Soils Sediments 2020, 20, 3062–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zhang, L.; Deng, B.; Liu, X.; Yi, H.; Xiang, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, W.; Guo, X.; Niu, D. Alpine Meadow Restorations by Non-Dominant Species Increased Soil Nitrogen Transformation Rates but Decreased Their Sensitivity to Warming. J. Soils Sediments 2017, 17, 2329–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Huang, K.; Cai, H.-H.; Li, J.; Zhai, D.-L.; Dai, Z.-C.; Du, D.-L. Exploring the Potential of Naturalized Plants for Phytore mediation of Heavy Metal Contamination. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2017, 11, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Ma, X.; Chu, S.; You, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, T.; et al. Nitrogen Cycle Induced by Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria Drives “Microbial Partners” to Enhance Cadmium Phytoremediation. Microbiome 2025, 13, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, T. Low Molecular Weight Organic Acids in Root Exudates and Cadmium Accumulation in Cadmium Hyperaccumu lator Solanum Nigrum L. and Non-Hyperaccumulator Solanum Lycopersicum L. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 17180–17185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzyakov, Y.; Xu, X. Competition between Roots and Microorganisms for Nitrogen: Mechanisms and Ecological Relevance. New Phytol. 2013, 198, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, P.; Wang, M.; Zhang, T.; Liu, X.; Jiang, H.; Sun, Y.; Cheng, X.; Yan, Q. Enhanced Cadmium Accumulation and Tolerance in Transgenic Hairy Roots of Solanum Nigrum L. Expressing Iron-Regulated Transporter Gene IRT1. Life 2020, 10, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Xia, R.; Zhong, J.; Liu, X.; Xia, T.; Tang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Bao, E.; Cao, K.; Chen, Q.; et al. Silicon and Iron Co-Application Modulates Cadmium Accumulation and Cell Wall Composition in Tomato Seedlings. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Wu, X.; Deng, X.; Lin, Z.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J.; He, T.; Yi, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. Mechanisms of Low Cadmium Accumulation in Crops: A Comprehensive Overview from Rhizosphere Soil to Edible Parts. Environ. Res. 2024, 245, 118054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, S. Molecular Mechanisms of Plant Metal Tolerance and Homeostasis. Planta 2001, 212, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyšek, P.; Richardson, D.M. Invasive Species, Environmental Change and Management, and Health. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2010, 35, 25–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Naggar, A.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, W.; Cai, Y.; Chang, S.X. Biochar Effectively Remediates Cd Contamination in Acidic or Coarse- and Medium-Textured Soils: A Global Meta-Analysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 442, 136225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lin, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Wang, B.; Ping, M.; Meng, Y.; Luo, W.; Chen, J.; Li, X. Synergistic Superiority of AMF and Biochar in Enhancing Rhizosphere Microbiomes to Support Plant Growth under Cd Stress. Biochar 2025, 7, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Feng, H.; Wan Mahari, W.A.; Yun, F.; Li, M.; Ma, N.L.; Cai, X.; Liu, G.; Liew, R.K.; Lam, S.S. Biochar and Microbial Synergy: Enhancing Tobacco Plant Resistance and Soil Remediation under Cadmium Stress. Biochar 2025, 7, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Chen, C.; Ni, C.; Xiong, J.; Wang, Z.; Cai, J.; Tan, W. How Different Is the Remediation Effect of Biochar for Cadmium Contaminated Soil in Various Cropping Systems? A Global Meta-Analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 448, 130939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Sun, X.; Zheng, S.; Wang, S.; Wu, L.; An, Y.; Luo, Y. Optimal Biochar Selection for Cadmium Pollution Remediation in Chinese Agricultural Soils via Optimized Machine Learning. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 476, 135065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.; Zhou, L.; Fu, Y.; Long, J.; Zhang, Z.; Miao, Y.; Guo, L.; Thakur, M.P.; Zhou, X. Invasive C4 Plants Cause Greater Soil Greenhouse Gas Emissions than C3 Plants. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 936–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocito, F.F.; Espen, L.; Crema, B.; Cocucci, M.; Sacchi, G.A. Cadmium Induces Acidosis in Maize Root Cells. New Phytol. 2008, 179, 700–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Zhou, Q.; Meng, B.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, T.; Yin, D.; Li, B.; Wang, C.; Gao, X.; Liu, J.; et al. Coupling of Mercury Contamination and Carbon Emissions in Rice Paddies: Methylmercury Dynamics versus CO2 and CH4 Emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 10274–10285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jiang, K.; Zhou, J.; Wu, B. Solidago Canadensis Invasion Affects Soil N-Fixing Bacterial Communities in Heteroge neous Landscapes in Urban Ecosystems in East China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 631–632, 702–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Xu, S.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lou, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, X.; Li, J.; Iqbal, B.; Cheng, P.; et al. Spartina Alterniflora Invasion Altered Soil Greenhouse Gas Emissions via Affecting Labile Organic Carbon in a Coastal Wetland. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2024, 203, 105615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrys, A.S.; Wen, Y.; Feng, D.; El-Mekkawy, R.M.; Kong, M.; Qin, X.; Lu, Q.; Dan, X.; Zhu, Q.; Tang, S.; et al. Cadmium Inhibits Carbon and Nitrogen Cycling through Soil Microbial Biomass and Reduces Soil Nitrogen Availability. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 489, 137524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezabih Beyene, B.; Li, J.; Yuan, J.; Dong, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, Z.; Kim, J.; Kang, H.; Freeman, C.; Ding, W. Non-Native Plant Invasion Can Accelerate Global Climate Change by Increasing Wetland Methane and Terrestrial Nitrous Oxide Emissions. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 5453–5468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omokaro, G.O.; Kornev, K.P.; Nafula, Z.S.; Chikukula, A.A.; Osayogie, O.G.; Efeni, O.S. Biochar for Sustainable Soil Man agement: Enhancing Soil Fertility, Plant Growth and Climate Resilience. Farming Syst. 2025, 3, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Gao, C.; Yang, K.; Sheng, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Lou, J.; Sun, R.; Zhu, L. Effects of Biochar Aging in the Soil on Its Mechanical Property and Performance for Soil CO2 and N2O Emissions. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 782, 146824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalu, S.; Seppänen, A.; Mganga, K.Z.; Sietiö, O.-M.; Glaser, B.; Karhu, K. Biochar Reduced the Mineralization of Native and Added Soil Organic Carbon: Evidence of Negative Priming and Enhanced Microbial Carbon Use Efficiency. Biochar 2024, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zou, T.; Lian, J.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, L.; Hamid, Y.; He, Z.; Jeyakumar, P.; Yang, X.; Wang, H. Simultaneous Mitigation of Cadmium Contamination and Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Paddy Soil by Iron-Modified Biochar. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 488, 137430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shi, L.; Zhai, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Zou, J.; Shen, Z.; Lian, C.; Chen, Y. Analysis of the Long-Term Effectiveness of Biochar Immobilization Remediation on Heavy Metal Contaminated Soil and the Potential Environmental Factors Weakening the Remediation Effect: A Review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 207, 111261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Wang, W.; Lu, L.; Yan, L.; Yu, D. Utilization of Biochar for the Removal of Nitrogen and Phosphorus. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 257, 120573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tang, Y.; Gao, W.; Pan, W.; Jiang, C.; Lee, X.; Cheng, J. Response of Soil N2O Production Pathways to Biochar Amend ment and Its Isotope Discrimination Methods. Chemosphere 2024, 350, 141002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.; Bao, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, R.; Huang, M.; Xia, Y.; Li, C.; Huang, Y. Experimental and Numerical Investigations of Biochar-Facilitated Cd2+ Transport in Saturated Porous Media: Role of Solution pH and Ionic Strength. Biochar 2023, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Fang, H.; Cheng, S.; Guo, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Pu, H.; Liu, B. Cadmium Accumulation Suppresses Rice Nitrogen Use Efficiency by Inhibiting Rhizosphere Nitrification and Promoting Nitrate Reduction. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 496, 139298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).