Abstract

The rhizosphere, a dynamic interface shaped by plant root exudates, fosters microbial communities with significant biochemical potential. This study investigated the interplay between soil properties and fungal bioactivity in the rhizospheres of Withania coagulans and Justicia adhatoda in Pakistan. Physicochemical analysis revealed silty loam textures with divergent phosphorus [25.7 vs. 71.5 mg/kg] and potassium [108 vs. 78 mg/kg] levels, alongside near-neutral pH, influencing microbial dynamics. Two fungal isolates, Aspergillus luchuensis and A. flavus, were identified through morphological traits and ITS-region sequencing. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry [GC-MS] profiling of ethyl acetate extracts uncovered 30 and 25 previously uncharacterized metabolites in A. luchuensis and A. flavus, respectively, including bioactive compounds such as tetradecanoic acid and nonadecane. Bioassays demonstrated broad-spectrum efficacy against multidrug-resistant clinical isolates, with A. flavus exhibiting notable inhibition against Salmonella typhi [31.7 mm zone] and A. luchuensis against Shigella spp. [23 mm]. Both extracts suppressed Lemna minor growth by 70%, indicating phytotoxic potential, and displayed species-specific insecticidal activity, inducing 70% mortality by A. luchuensis against Blattodea and 50% by A. flavus against the same species. These findings underscore the rhizosphere’s role as a reservoir of bioactive fungi, with Aspergillus spp. producing metabolites of pharmaceutical and agrochemical relevance. The study highlights the necessity for advanced structural elucidation and ecotoxicological assessments to harness these compounds, advocating integrated approaches combining metabolomics and genomic mining to unlock novel biotechnological applications.

1. Introduction

The rhizosphere—the thin layer of soil immediately surrounding plant roots—is enriched by root exudates such as sugars, amino acids, and organic acids, which create nutrient-rich microzones that sustain dense microbial populations and heightened biochemical activity [1]. These “hotspots” exhibit accelerated rates of organic matter decomposition and nutrient turnover compared to bulk soil, driving key processes like nitrogen mineralization and carbon cycling [2].

Soil physicochemical properties—including pH, organic carbon content, and the concentrations of nitrogen [N], phosphorus [P], and potassium [K]—strongly shape rhizosphere microbial community structure and function. Soil pH alone can account for up to 70% of the variation in bacterial diversity across different ecosystems, with neutral-pH soils supporting the greatest richness [3]. Moreover, localized pulses of labile carbon and nutrients at the root–soil interface generate “hot moments” of microbial activity that disproportionately influence overall soil biogeochemistry [2].

Fungi are central to soil ecosystem functioning: their extracellular enzymes decompose complex polymers such as cellulose, lignin, and chitin into simpler compounds available to plants and other microbes [4,5]. Beyond nutrient cycling, many soil fungi produce structurally diverse secondary metabolites—including antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and anticancer agents—that hold promise for pharmaceutical and agricultural applications [6]. In addition, certain fungal metabolites exhibit potent insecticidal activities, offering environmentally friendly alternatives to synthetic pesticides [7].

Within the genus Aspergillus, A. luchuensis is valued in fermentation industries for its high yields of amylolytic and proteolytic enzymes and prolific citric acid secretion, which lowers mash pH to suppress contaminants [8]. Genome sequencing of strain NBRC 4314 has revealed an extensive suite of glycosidase genes and regulatory networks that underlie its robustness in awamori and shōchū fermentations [8]. In contrast, A. flavus is best known for aflatoxin biosynthesis, yet its genome harbors at least 56 cryptic secondary metabolite gene clusters encoding polyketide synthases, non-ribosomal peptide synthetases, and terpene cyclases, many of which can be activated under specific environmental stimuli [9].

The main objectives of this study were to: (1) use GC-MS to profile the extracellular metabolite composition of two Aspergillus isolates that were recovered from the rhizospheres of Withania coagulans and Justicia adhatoda; (2) assess the antimicrobial, phytotoxic, and insecticidal activities of these crude extracts; and (3) investigate relationships between soil physicochemical characteristics and fungal metabolic output. It was possible to identify bioactive candidates of pharmacological or agrochemical interest for further structural and functional validation by connecting metabolite patterns to rhizosphere conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil Sampling and Processing

Rhizospheric soil samples were collected from the rhizosphere of Withania coagulans and Justicia adhatoda cultivated in Bara, District Khyber, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Samples were excavated at a depth of 15 cm using sterilized tools, transferred in aseptic polyethylene containers, and transported to the Microbiology Laboratory at Sarhad University of Science and Information Technology, Peshawar, for subsequent analysis.

2.2. Physicochemical Profiling of Soil

Temperature, pH, organic carbon (C), nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), and soil texture were all assessed. The Bouyoucos hydrometer method (Model 152H, Soiltest Inc. Wheaton, IL, USA; accuracy ±0.5%) was used to measure the particle size distribution of sand, silt, and clay. The Soil and Water Analysis Facility, Agricultural Research Institute, Tarnab, Peshawar, Pakistan, quantified organic carbon and nitrogen in accordance with recognized protocols [10]. A UV-Visible spectrophotometer (Model UV-1800, Shimadzu, Japan; accuracy ±0.3 nm) and a flame photometer (Model PFP7, Jenway, Dunmow, Essex, UK; precision ±1%) were used to measure the amounts of potassium and phosphorus, respectively. A portable digital pH meter (Model HI99121, Hanna Instruments Inc., Smithfield, RI, USA; resolution ±0.01 pH) was used to record the initial soil color and pH at the time of collection.

2.3. Fungal Isolation and Purification

The plates were incubated under static conditions for 6–8 days at 28 °C. The reason for choosing this temperature is that mesophilic soil fungi typically thrive around 25 to 30 °C, and 28 °C is a typical compromise that allows for the best growth of environmental Aspergillus species as well as other rhizosphere fungi. Due to its ability to facilitate the sporulation and growth of a wide variety of soil fungus, Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) (Thermo Scientific™ Oxoid™. CM0139B, Waltham, MA, USA) was employed. Static aerobic conditions were used for incubation, and the medium was treated with 50 µg/mL of chloramphenicol to promote fungal isolation over bacterial isolation. Pure cultures were produced by isolating the hyphal tips and repeatedly subculturing individual colonies onto new PDA. Prior to DNA extraction, uniform colony morphology and microscopic examination with lactophenol cotton blue were used to verify purity.

2.4. Microscopic Characterization

Hyphal and spore structures were analyzed using light microscopy. Slide cultures were prepared to observe reproductive features, including conidiophores and sporangia. Colony morphology [pigmentation, texture] and purity were documented via macroscopic and microscopic examination [10].

2.5. Molecular Phylogenetic Analysis

Using the CTAB-based method of [11], genomic DNA was isolated from fresh mycelia using a SolGent Fungus Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Cat. No. SGD64-S120; SolGent Co., Daejeon, Republic of Korea). By using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, the purity of the DNA was verified. Since the Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region of nuclear rDNA offers better species-level resolution and functions as the universal fungal barcode in contrast to the more conserved 18S rRNA gene, it was amplified using universal primers ITS1 and ITS4. EF-Taq polymerase (SolGent, Republic of Korea) was used for PCR amplification on a BIO-RAD T100™ thermocycler. The BigDye™ Terminator v3.1 Kit was used to sequence the purified amplicons on an ABI 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). To identify the obtained sequences, similarity searches were performed using BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool), NCBI BLAST+ version 2.17.0.

2.6. Metabolite Extraction and GC–MS Profiling

For ten days, fungal isolates were cultivated in Potato Dextrose Broth [PDB] (Thermo Scientific™ Oxoid™. CM0962B) at 28 °C and 150 rpm. Cultures were filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper, and the resulting biomass-free filtrates (cell-free supernatants) were collected and processed with Ethyl acetate (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MI, USA; CAS 141-78-6) for 24 h in a separatory funnel in 1:1 v/v. For GC-MS analysis, the organic phase was reconstituted in minimum EtOAc after being concentrated by rotational evaporation at 40 °C and 150 mbar. Chromatographic separation was carried out using an Agilent 7890B GC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) that was interfaced with a 5977B mass selective detector (Agilent Technologies, USA; mass accuracy ±0.1 m/z) and fitted with a DB-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm film thickness; J&W Scientific, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The carrier gas was helium (99.999%, purity certified, Linde Gas, Pullach, Germany) at a steady 1 mL/min flow rate. Ionization was carried out at 70 eV. Metabolites were annotated using the NIST 2020 library [12]. Following solvent partitioning, the ethyl acetate fractions were combined and dried by rotary evaporation and vacuum desiccation to a consistent weight at a lower pressure. Prior to bioassay, the dry crude extracts were weighed and kept at −20 °C. Extracts were reconstituted in less than 1% DMSO to provide stock solutions for bioactivity tests.

Ethyl acetate was solely used to extract the culture filtrate in this investigation; the mycelial biomass was not included. Extracellular metabolites were the main focus of study, since they are released into the medium and are more likely to be diffusible bioactive substances that affect rhizosphere interactions. Mycelial extraction usually targets intracellular metabolites that require acetone or methanol extraction and subsequent cleanup, while extracellular extracts frequently contain higher concentrations of volatile and low-molecular-weight compounds amenable to GC–MS analysis, according to previous reports.

2.7. Detection of Multidrug-Resistant [MDR] Bacterial Species

Clinical specimens from diabetic foot ulcers were obtained from City General Hospital, Peshawar, and streaked on nutrient agar. Isolates were identified through Gram staining, colony morphology, and biochemical assays [catalase, oxidase, indole, citrate utilization, TSI]. Antibiotic susceptibility was tested against 10 broad-spectrum antibiotics [Table 1] [13] on Mueller-Hinton agar via disk diffusion [CLSI, 2020]. MDR strains resistant to ≥3 antibiotic classes were selected for bioactivity assays [14].

Table 1.

Antibiotics used for detection of Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria.

2.8. Antimicrobial Bioassays

Crude extracts [3 mg/mL DMSO] were tested in triplicate (n = 3) against multidrug-resistant bacterial and fungal isolates using the agar-well diffusion method. Wells [6 mm] were loaded with 100 µL extract, with ciprofloxacin [5 µg/mL] and fluconazole [25 µg/mL] as positive controls. The mean diameter (mm ± SE) of inhibition zones was recorded after 24–48 h incubation at 37 °C. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values were determined via broth microdilution (range = 0.01–0.64 µg/mL), and IC50 values were calculated using % mortality [15]. The usual starting points for assessing the bioactivity of crude extracts in natural product research were determined to be 3 mg/mL for antibacterial and 4 mg/mL for antifungal tests. These concentrations are frequently employed to identify activity in unfractionated crude material.

2.9. Phytotoxicity Assessment

Lemna minor fronds were cultured in E-media supplemented with 100 µg/mL extract [1 mg/mL stock in DMSO]. Growth inhibition was quantified after 7 days at 30 °C relative to paraquat-treated [positive control (1 mg/mL)] and untreated groups and the assays were performed in triplicate [16]. Frond viability was calculated as:

2.10. Insecticidal Bioactivity

Termites [Isoptera] and cockroaches [Blattodea] were exposed to filter paper impregnated with 100 µg culture extract /mL DMSO [17]. All assays were performed in triplicate. Permethrin (0.1 mg/mL) was used as positive control for insecticidal tests. Extract concentrations ranged from 10 to 100 µg/mL to calculate IC50 values. Mortality percentages were expressed as mean ± SE.

2.11. Statistical Evaluation

Data were analyzed using SPSS 16.0 [SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA]. Mean ± standard error [SE] was calculated for triplicate experiments.

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Properties of Rhizosphere Soils

The rhizosphere soils of Withania coagulans and Justicia adhatoda exhibited a silty loam texture with distinct quantitative differences. The sand content was 54% in W. coagulans soil compared to 64% in J. adhatoda soil, while clay and silt contents were comparable [12% vs. 10% for clay and 26% for silt in both soils]. Organic matter [1.03% vs. 1.06%] and nitrogen levels [0.052 mg/kg vs. 0.053 mg/kg] were nearly identical between the two soils. However, phosphorus concentrations diverged significantly, with W. coagulans soil containing 25.7 mg/kg versus 71.5 mg/kg in J. adhatoda soil, and potassium levels were higher in W. coagulans soil [108 mg/kg] compared to J. adhatoda soil [78 mg/kg]. Both soils exhibited a slightly acidic to neutral pH, consistent with fertile brown soils [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparative Physicochemical Analysis of Rhizosphere of Withania coagulans and Justicia adhatoda.

3.2. Isolation and Morphological Characterization of Rhizospheric Fungi

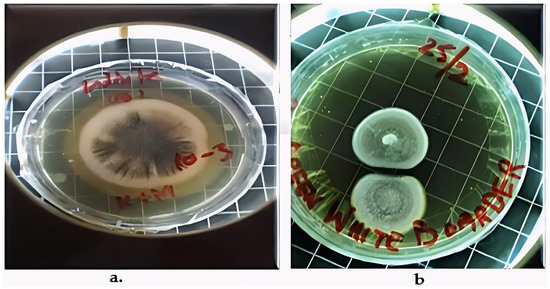

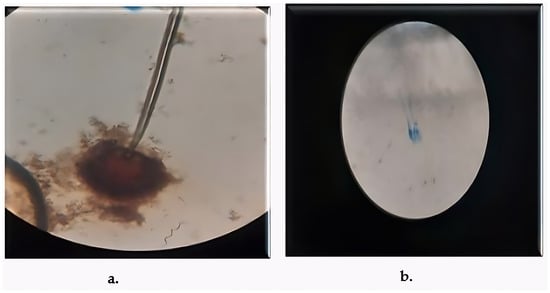

Two fungal strains, Aspergillus luchuensis and Aspergillus flavus, were isolated from the rhizospheres. On PDA, A. luchuensis developed colonies with a distinctive black-and-white mycelial pattern and formed sporangia containing coenocytic hyphae [Figure 1]. In contrast, A. flavus produced colonies characterized by olive-green conidia with white margins and displayed branched conidiophores bearing powdery conidial heads [Figure 1 and Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Colony Morphology of Rhizospheric Fungi on PDA potato dextrose agar. (a) Aspergillus luchuensis (MTCC strain) from Justicia adhatoda exhibits a distinctive black-and-white mycelial pattern with sporangia; (b) Aspergillus flavus (WTCC strain) from Withania coagulans displays olive-green conidia with white margins.

Figure 2.

Microscopic Structures of Rhizospheric Fungi Light micrographs of fungal isolates stained with lactophenol cotton blue. (a) A. luchuensis showing sporangia with clustered spores; (b) A. flavus exhibiting branched conidiophores with powdery conidial heads.

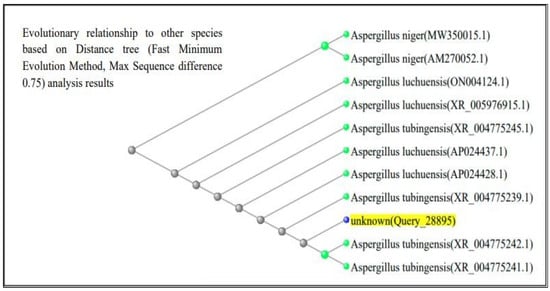

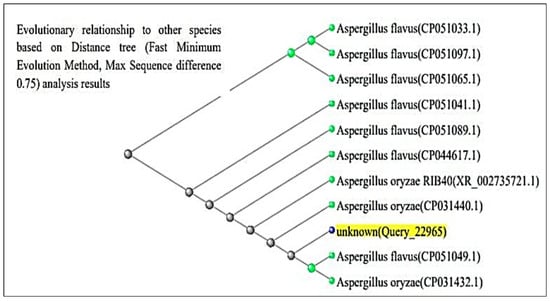

3.3. Molecular Identification via 18S rRNA Sequencing

The ITS region of nuclear rDNA from both fungal isolates was amplified using universal primers ITS1 and ITS4, and the resulting sequences were analyzed using the BLAST tool in the NCBI GenBank database. According to Figure 3 and Figure 4, BLAST analysis confirmed that both isolates shared 99–100% sequence similarity with their respective Aspergillus reference strains. The A. flavus isolate showed 100% sequence identity with A. flavus reference sequences (GenBank accession no. PQ571952), while the A. luchuensis isolate showed 99–100% sequence similarity with A. luchuensis reference sequences (GenBank accession no. PQ571950). These accession numbers correspond to the sequences submitted to GenBank following verification of full homology, ensuring taxonomic accuracy.

Figure 3.

Sequence analysis of Aspergillus luchuensis (MTCC strain). BLAST alignment confirmed 99–100% sequence similarity with reference strains of A. luchuensis (NCBI accession: PQ571950), supporting its molecular identification.

Figure 4.

The sequence of A. flavus (WTCC strain) is presented. Homology analysis demonstrated 100% similarity with the reference strain (NCBI accession: PQ571952), verifying its genetic identity.

3.4. GC–MS Profiling of Fungal Culture Filtrates

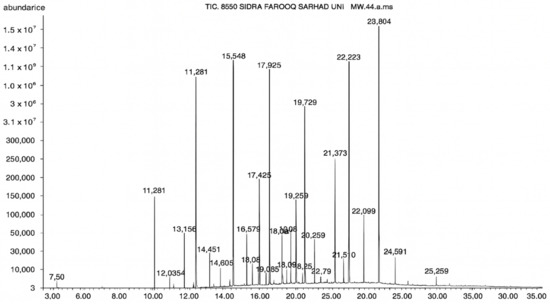

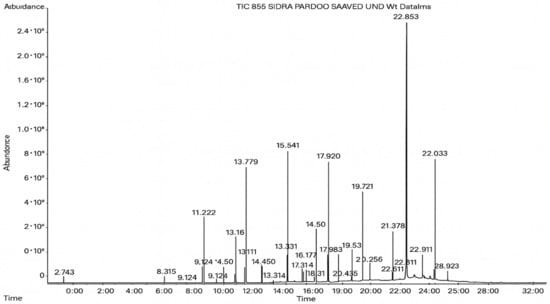

GC–MS analysis identified 30 and 25 compounds in A. luchuensis and A. flavus, respectively. Only compounds with a library match quality above 90% were included, and their relative proportions were calculated from normalized peak areas in the total ion chromatogram. Among the novel compounds detected in both extracts were p-Xylene, tetradecane, and bis[2-ethylhexyl] phthalate (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Additionally, known bioactive compounds such as tetradecanoic acid, which has documented antifungal and antioxidant properties, and nonadecane, noted for its antimicrobial activity, were also identified [Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6].

Figure 5.

GC–MS chromatogram of the ethyl acetate extract from A. luchuensis is shown, highlighting peaks corresponding to 30 hitherto unreported compounds reported for the first time from this source. Retention times and relative intensities are displayed, reflecting a complex metabolic profile.

Figure 6.

The GC–MS profile of the A. flavus ethyl acetate extract revealed 25 hitherto unreported compounds reported for the first time from this source, visualized through distinct retention peaks. The data support the metabolic versatility of the isolate.

Table 3.

Hitherto unreported compounds identified for the first time from the crude ethyl acetate extract of Aspergillus luchuensis.

Table 3.

Hitherto unreported compounds identified for the first time from the crude ethyl acetate extract of Aspergillus luchuensis.

| S. No | Peak No. | Retention Time (Mins) | Peak Areas | Reference Peaks | Quality | Structures | Functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 1 | 2.750 | 10,288,308 | 5721 | 95 |  p-Xylene | Solvent in printing and painting industries | [18] |

| 2. | 2 | 11.281 | 78,790,005 | 74,004 | 98 |  Tetradecane | Antibacterial and antifungal agent | [19] |

| 3. | 3 | 12.098 | 16,323,498 | 90,197 | 96 |  Tetradecane, 2-methyl- | Function unknown till now | |

| 4. | 4 | 12.542 | 17,945,463 | 90,192 | 97 |  Pentadecane | Antifungal agent | [20] |

| 5. | 5 | 13.158 | 56,062,405 | 101,093 | 98 |  Diethyl Phthalate | Antibacterial agent | [21] |

| 6. | 6 | 13.612 | 28,625,634 | 104,590 | 99 |  Cetene | Function unknown till now | |

| 7. | 7 | 13.754 | 240,438,495 | 107,219 | 99 |  Hexadecane | Function unknown till now | |

| 8. | 8 | 14.461 | 36,352,485 | 123,967 | 98 |  Hexadecane, 2-methyl | Function unknown till now | |

| 9. | 9 | 14.856 | 26,610,402 | 123,958 | 98 |  Heptadecane | Improves oxidative stress-related diseases | [22] |

| 10. | 10 | 15.318 | 17,507,832 | 109,284 | 98 |  Tetradecanoic acid | Antifungal, antioxidant, anticancer, nematocidal and also functions as lubricant | [23] |

| 12. | 12 | 15.948 | 293,848,711 | 141,057 | 97 |  Octadecane | Function unknown till now | |

| 13. | 17 | 17.639 | 7,140,310 | 141,058 | 96 | |||

| 14. | 32 | 20.556 | 11,375,318 | 141,058 | 96 | |||

| 15. | 14 | 16.579 | 52,483,248 | 158,611 | 98 |  Octadecane, 2-methyl- | Antimicrobial and antitumor potential | [24] |

| 16. | 15 | 15.501 | 24,273,045 | 158,597 | 98 |  Nonadecane | Activity against plant fungal pathogens | [25] |

| 17. | 16 | 17.428 | 233,542,838 | 143,511 | 99 |  n-Hexadecanoic acid | Antioxidant, nematicide and pesticide | [26] |

| 18. | 18 | 17.690 | 13,409,546 | 179,135 | 98 |  Hexadecanoic acid, ethyl ester | Antioxidant, hemolytic, hypo-cholesterolemic, nematicide and anti-androgenic | [27] |

| 19. | 19 | 17.816 | 15,840,959 | 138,521 | 99 |  1-Octadecene | Medicines and cosmetics | [28] |

| 20. | 20 | 17.925 | 258,633,377 | 176,384 | 98 |  Eicosane | Antimicrobial activities | [29] |

| 21. | 31 | 20.259 | 42,778,282 | 176,387 | 93 | |||

| 22. | 45 | 26.989 | 17,988,115 | 176,384 | 98 | |||

| 23. | 22 | 18.503 | 53,705,129 | 194,594 | 99 |  Eicosane, 2-methyl- | Bioactive compound | [30] |

| 24. | 23 | 18.824 | 17,867,516 | 194,588 | 98 |  Heneicosane | Pheromonic and fumigating properties | [29] |

| 25. | 24 | 18.935 | 98,703,795 | 173,581 | 99 |  9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)- | Antimicrobial properties | [26] |

| 26. | 28 | 19.520 | 8,277,967 | 214,945 | 98 |  Octadecanoic acid, ethyl ester | Antimicrobial agent | [31] |

| 27. | 34 | 21.304 | 9,835,708 | 209,740 | 99 |  1-Docosene | Antibacterial compound | [32] |

| 28. | 35 | 21.379 | 117,296,495 | 246,483 | 99 |  Tetracosane | Antagonistic potential against toxigenic and phytopathogenic fungi | [33] |

| 29. | 43 | 24.591 | 33,753,194 | 246,483 | 99 | |||

| 30. | 36 | 21.876 | 35,975,300 | 262,016 | 99 |  2-Methyltetracosane | Function unknown till now | |

| 31. | 37 | 22.160 | 7,134,674 | 262,011 | 98 |  Pentacosane | Function unknown till now | |

| 32. | 38 | 22.229 | 282,707,118 | 295,611 | 91 |  Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate | Antibacterial and larvicidal activity | [34] |

| 33. | 40 | 22.908 | 69,037,303 | 275,538 | 98 |  Hexacosene | Function unknown till now | |

| 34. | 41 | 23.390 | 20,703,676 | 246,483 | 98 |  Tetracosane | Antagonistic potential against toxigenic and phytopathogenic fungi | [33] |

| 35. | 42 | 23.904 | 445,455,491 | 295,785 | 94 |  1,4-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis(2-ethylhexyl) ester | Function unknown till now | |

| 36. | 44 | 25.259 | 12,351,665 | 307,034 | 99 |  Octacosane, 2-methyl- | Antimicrobial agent | [31] |

Table 4.

Reported Compounds Extracted from Crude Ethyl Acetate Extract of A. luchuensis.

Table 4.

Reported Compounds Extracted from Crude Ethyl Acetate Extract of A. luchuensis.

| S. No | Peak No. | Retention Time (Mins) | Peak Areas | Reference Peaks | Quality | Structures | Functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 25 | 19.009 | 77,699,002 | 176,208 | 99 |  Oleic Acid | Function unknown till now | |

| 2. | 26 | 19.182 | 19,343,950 | 209,617 | 99 |  Linoleic acid ethyl ester | Function unknown till now | |

| 3. | 27 | 19.257 | 133,934,985 | 179,093 | 99 |  Octadecanoic acid | Function unknown till now | |

| 4. | 29 | 19.635 | 15,910,485 | 155,961 | 98 |  1-Nonadecene | Antifungal and anticancer agent | [26] |

| 5. | 30 | 19.726 | 181,536,736 | 212,282 | 99 |  Docosane | Function unknown till now | |

| 6. | 39 | 22.846 | 7,637,629 | 273,800 | 99 |  1-Hexacosene | Function unknown till now | |

Table 5.

Hitherto unreported compounds identified for the first time from the crude ethyl acetate extract of Aspergillus flavus.

Table 5.

Hitherto unreported compounds identified for the first time from the crude ethyl acetate extract of Aspergillus flavus.

| S. No | Peak No. | Retention Time (Mins) | Peak Areas | Reference Peaks | Quality | Structures | Functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 1 | 2.749 | 9,481,682 | 5720 | 97 |  p-Xylene | Solvent in printing and painting industries | [18] |

| 2. | 2 | 8.895 | 48,805,295 | 18,696 | 94 |  Benzene acetic acid | Broad-spectrum antifungal agent | [35] |

| 3. | 3 | 9.912 | 6,729,875 | 59,028 | 95 |  Tridecane | Antioxidant activity | [36] |

| 4. | 5 | 11.131 | 34,797,276 | 71,738 | 99 |  2-Tetradecene, (E)- | Anticancer, antimicrobial and antioxidant | [37] |

| 5. | 6 | 11.282 | 104,087,172 | 74,004 | 98 |  Tetradecane | Antibacterial and antifungal agent | [19,38] |

| 6. | 7 | 11.869 | 10,474,783 | 99,032 | 98 |  2,5-Cyclohexadiene-1,4-dione, 2,6-bis (1,1- dimethylethyl)- | Antibacterial and antifungal agent | [19,38] |

| 7. | 8 | 12.099 | 18,795,488 | 74,012 | 90 |  3,5-Dimethyldodecane | Function unknown till now | |

| 8. | 9 | 12.425 | 32,616,847 | 82,737 | 97 |  2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol | Exhibits strong toxicity against significant ratio of tested organisms as well as the producing species | [39] |

| 9. | 10 | 12.541 | 17,844,280 | 90,192 | 97 |  Pentadecane | Antifungal agent | [20] |

| 10. | 11 | 13.161 | 80,026,380 | 101,097 | 98 |  Diethyl Phthalate | Active against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial species | [21] |

| 11. | 12 | 13.614 | 56,298,031 | 104,590 | 99 |  Cetene | Function unknown till now | |

| 12. | 16 | 15.317 | 15,633,869 | 109,281 | 96 |  Tetradecanoic acid | Antifungal, antioxidant, anticancer, nematocidal, hypercholesterolemic and can be used as lubricant | [23] |

| 13. | 19 | 16.194 | 13,005,006 | 241,696 | 90 |  Phthalic acid, isobutyl octyl ester | Anti-microbial activity | [40] |

| 14. | 22 | 16.709 | 19,568,824 | 168,692 | 99 |  7,9-Di-tert-butyl-1-oxaspiro (4,5) deca-6,9-diene-2,8- dione | Prevention and treatment of periodontitis | [41] |

| 15. | 23 | 16.933 | 22,968,819 | 158,600 | 98 |  Nonadecane | Active against plant fungal pathogens | [25] |

| 16. | 24 | 17.106 | 22,346,257 | 170,787 | 95 |  1,4-Dibutyl benzene-1,4-dicarboxylate | Function unknown till now | |

| 17. | 30 | 18.824 | 13,405,806 | 194,587 | 98 |  Heneicosane | Antifungal compound | [42] |

| 18. | 33 | 19.635 | 46,586,432 | 209,741 | 99 |  Docosene | Function unknown till now | |

| 19. | 34 | 19.721 | 150,288,747 | 212,282 | 98 | Function unknown till now | ||

| 20. | 37 | 21.304 | 25,049,939 | 244,233 | 99 |  Cyclotetracosane | Antibacterial as well as α-amylase inhibitory activity | [43] |

| 21. | 38 | 21.376 | 95,053,436 | 246,483 | 99 |  Tetracosane | Antagonistic potential against toxigenic and phytopathogenic fungi | [33] |

| 22. | 39 | 21.872 | 49,711,235 | 262,016 | 99 |  2-Methyltetracosane | Function unknown till now | |

| 23. | 40 | 22.293 | 1,231,442,386 | 295,608 | 91 |  Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate | Antibacterial and larvicidal activity | [34] |

| 24. | 41 | 22.850 | 16,685,206 | 259,983 | 99 |  Z-12-Pentacosene | Function unknown till now | |

| 25. | 44 | 25.259 | 12,351,665 | 295,779 | 95 |  1,4-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis(2-ethylhexyl) ester | Function unknown till now | |

| 26. | 45 | 23.979 | 13,522,101 | 245,085 | 97 |  13-Docosenamide, (Z)- | Function unknown till now | |

Table 6.

Reported Compounds Extracted from Crude Ethyl Acetate Extract of A. flavus.

Table 6.

Reported Compounds Extracted from Crude Ethyl Acetate Extract of A. flavus.

| S. No | Peak No. | Retention Time (Mins) | Peak Areas | Reference Peaks | Quality | Structures | Functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 4 | 11.068 | 22,425,688 | 22,402 | 94 |  4H-Pyran-4-one, 5-hydroxy-2-(hydroxymethyl) | Natural kojic acid | [44] |

| 2. | 13 | 13.749 | 202,662,852 | 107,219 | 99 |  Hexadecane | Function unknown till now | |

| 3. | 14 | 14.460 | 30,280,445 | 123,967 | 99 |  Hexadecane, 2-methyl | Function unknown till now | |

| 4. | 15 | 14.854 | 22,603,766 | 123,960 | 98 |  Heptadecane | Improves oxidative stress-related diseases | [22] |

| 5. | 17 | 15.821 | 54,267,257 | 138,490 | 99 |  E-15-Heptadecenal | Antifungal, anti-cancerous, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties | [45] |

| 6. | 18 | 15.941 | 239,852,366 | 141,058 | 98 |  Octadecane | Function unknown till now | |

| 8. | 36 | 20.555 | 6,645,236 | 141,056 | 95 | |||

| 9. | 46 | 24.593 | 22,146,253 | 141,056 | 96 | |||

| 10. | 20 | 16.521 | 21,799,447 | 87,012 | 97 |  Pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine-1,4-dione, hexahydro-3-(2- methylpropyl)- | Function unknown till now | |

| 11. | 21 | 16.577 | 50,622,981 | 158,611 | 97 |  Octadecane, 2-methyl | Function unknown till now | |

| 12. | 25 | 17.420 | 208,755,615 | 143,511 | 99 |  n-Hexadecanoic acid | Antioxidant, nematicide and pesticide | [26] |

| 14. | 28 | 17.920 | 209,202,265 | 176,384 | 99 |  Eicosane | Pheromonic, antimicrobial activities and fumigating properties | [29] |

| 15. | 29 | 18.505 | 76,888,883 | 194,594 | 97 |  Eicosane, 2-methyl | Bioactive compound | [30] |

| 16. | 31 | 18.970 | 15,114,772 | 176,208 | 99 |  Oleic Acid | Function unknown till now | |

| 17. | 32 | 19.236 | 88,525,166 | 179,093 | 99 |  Octadecanoic acid | Function unknown till now | |

| 18. | 35 | 20.256 | 37,411,957 | 212,282 | 97 |  Docosane | Function unknown till now | |

| 19. | 42 | 22.911 | 49,585,222 | 275,538 | 97 |  Hexacosane | Function unknown till now | |

| 20. | 43 | 23.392 | 16,166,875 | 246,483 | 97 |  Tetracosane | Antagonistic potential against toxigenic and phytopathogenic fungi | [33] |

3.5. Antibiotic Resistance Profiling of Diabetic Foot Ulcer Bacteria

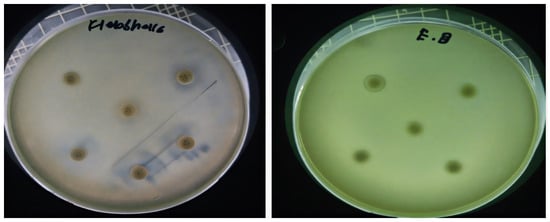

Eight multidrug-resistant [MDR] bacterial species were isolated from diabetic foot ulcer samples and identified through gram staining and biochemical tests, including Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Shigella spp., Salmonella typhi, Enterobacter aerogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, and Staphylococcus epidermidis [Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9]. Antibiotic susceptibility assays conducted according to CLSI-2020 guidelines revealed resistance to three or more drug classes, with P. aeruginosa demonstrating resistance to 9 out of the 10 antibiotics tested [Figure 7 and Figure 8].

Table 7.

Bacterial Characterization by Gram Stain and Growth Characteristics.

Table 8.

Biochemical Profiling of Diabetic Foot Ulcer Bacteria.

Table 9.

Antibiotic Resistance Profile of Bacterial Isolates from Diabetic Foot Ulcers.

Figure 7.

Antibiotic resistance patterns of bacterial isolates recovered from diabetic foot ulcers are depicted. Clear area represents the diameter of inhibition zones for each antibiotic, emphasizing extensive resistance observed among multiple strains.

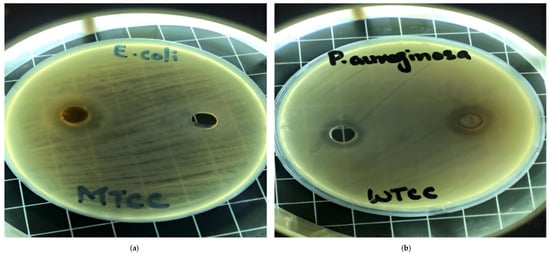

Figure 8.

Antibacterial activity of fungal culture filtrates against MDR bacteria. Panel (a) illustrates zones of inhibition induced by A. luchuensis extract, while panel (b) shows enhanced activity by A. flavus extract, particularly against S. typhi, S. epidermidis, and K. pneumoniae.

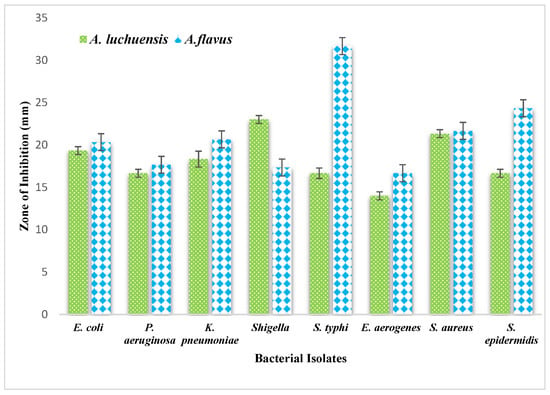

3.6. Antibacterial Activity of Fungal Extracts

The antibacterial potential of the fungal culture filtrates was evaluated using a 3 mg/mL solution in diluted DMSO. The A. luchuensis filtrate exhibited inhibition zones of 23 mm against Shigella, 21.33 mm against S. aureus, and 19.33 mm against Enterobacter aerogenes. In contrast, the A. flavus filtrate demonstrated broader antibacterial efficacy, with inhibition zones of 31.66 mm against Salmonella typhi, 24.33 mm against S. epidermidis, 21.66 mm against S. aureus, 20.66 mm against K. pneumoniae, and 20.33 mm against E. coli [Figure 9].

Figure 9.

Comparative graphical representation of antibacterial efficacy of A. luchuensis and A. flavus extracts. Inhibition zones against multiple MDR bacterial strains are shown, with A. flavus exhibiting a broader spectrum of activity.

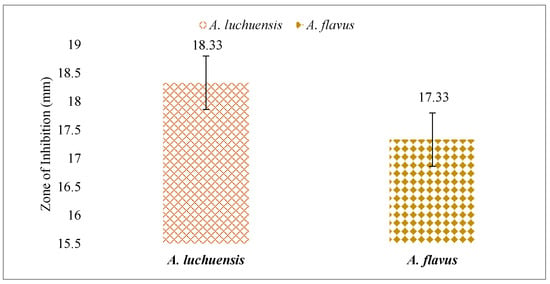

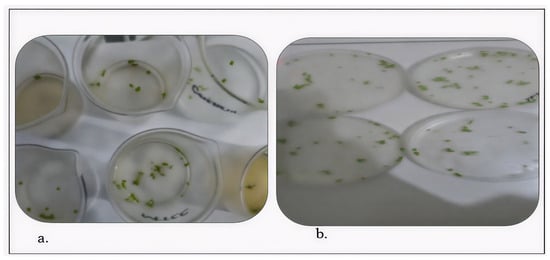

3.7. Antifungal and Phytotoxic Effects

Both fungal extracts were tested against Candida albicans. The A. luchuensis filtrate produced an inhibition zone of 18.33 mm, slightly exceeding the 17.33 mm zone produced by the A. flavus filtrate [Figure 10 and Figure 11]. Additionally, when applied at 100 μg/mL, both extracts suppressed the growth of Lemna minor by 70%, indicating comparable phytotoxicity (Table 10).

Table 10.

Gram Staining and Biochemical Characteristics of Candida albicans Isolated from Diabetic Foot Ulcers.

Table 10.

Gram Staining and Biochemical Characteristics of Candida albicans Isolated from Diabetic Foot Ulcers.

| Test | Method/Medium Used | Observation/Result |

|---|---|---|

| Gram staining | Smear stained with crystal violet–iodine–safranin sequence | Purple oval budding yeast cells |

| Cell morphology (microscopy) | Wet mount (40×) | Oval to spherical budding cells, pseudohyphae observed |

| Sugar fermentation | Glucose, maltose, sucrose, lactose broths with Durham tubes | Glucose and maltose fermented with gas; sucrose/lactose not fermented |

| Urease test | Christensen’s urea agar | No color change (-ive) |

| Catalase test | 3% hydrogen peroxide | Immediate effervescence (+ive) |

Figure 10.

A comparative assessment of antifungal activity between A. luchuensis and A. flavus is presented. Both extracts showed inhibition against Candida albicans, with marginally higher efficacy observed for A. luchuensis.

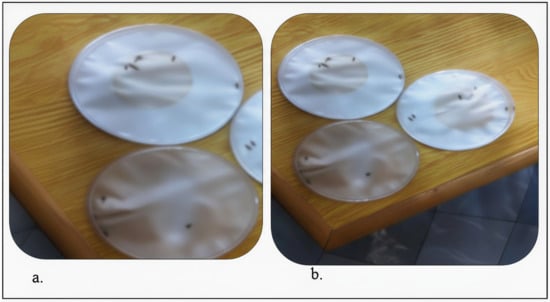

Figure 11.

Phytotoxic effects of fungal crude extracts on Lemna minor are shown. Panel (a) depicts results from A. luchuensis, and panel (b) from A. flavus. Both treatments caused 70% growth inhibition after 7 days of exposure at 100 µg/mL.

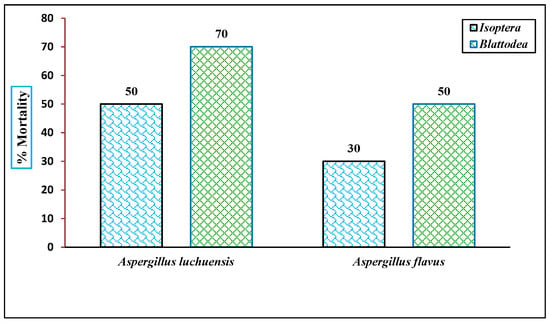

3.8. Insecticidal Potential

The insecticidal activities of the fungal culture filtrates were evaluated at a concentration of 100 μg/mL against two insect orders. The A. luchuensis filtrate induced a mortality rate of 40% in Isoptera and 70% in Blattodea, while the A. flavus filtrate caused 30% mortality in Isoptera and 50% in Blattodea within 24 h [ Figure 12 and Figure 13]. These results concluded that the insecticidal properties are species-specific, with A. luchuensis exhibiting a more pronounced effect.

Figure 12.

The insecticidal activity of fungal extracts is displayed against Isoptera and Blattodea. Mortality rates were recorded at 100 µg/mL after 24 h, with A. luchuensis showing higher efficacy across both insect taxa.

Figure 13.

Insecticidal activity of Culture filtrate of (a) A. luchuensis and (b) A. flavus

4. Discussion

The differential P and K levels and minor textural variations between the two rhizospheres may have an impact on secondary metabolism and the composition of fungal communities, even though causality cannot be conclusively proved from the current dataset. The different chemical profiles seen for the two isolates may partially reflect local soil chemistry since factors like nutrient status and root exudation patterns might alter the expression of fungal biosynthetic gene clusters. To firmly connect soil properties to biosynthetic output, future research integrating metagenomics, transcriptomics, and targeted metabolomics will be required.

The bioactivities and extracellular metabolite profiles of two rhizospheric Aspergillus isolates linked to Withania coagulans and Justicia adhatoda were evaluated in this investigation. Numerous volatile and non-polar metabolites with documented antibacterial or insecticidal properties were included in the preliminary inventory of metabolites produced by the GC–MS study. The biological effects of crude ethyl acetate extracts included phytotoxicity against Lemna minor and detectable inhibition against clinical isolates that were resistant to many drugs. Local soil chemistry, particularly variations in phosphate and potassium levels, may be the cause of the observed variations in metabolite composition between the two isolates. These variations have been shown to affect secondary metabolism in soil fungi. Integration of transcriptomics and metabolomics is still needed to test the mechanistic relationships between soil characteristics and metabolite expression.

Axenic cultures of A. luchuensis and A. flavus were corroborated by characteristic colony pigmentation and microscopy, and then validated by ITS region sequencing. The genome of A. luchuensis NBRC 4314 [~34.7 Mb] encodes extensive glycosidase repertoires and regulatory networks underpinning its robust enzyme secretion [18]. Conversely, A. flavus harbors at least 55 cryptic secondary metabolite gene clusters—including polyketide synthases, nonribosomal peptide synthetases, and terpene cyclases—many of which can be activated by environmental cues [19].

GC–MS analyses revealed 30 novel compounds in A. luchuensis and 25 in A. flavus, such as p-xylene, tetradecane, and bis[2-ethylhexyl] phthalate. Fungal extracellular enzymes decompose complex polymers [cellulose, lignin, chitin] into simpler precursors for secondary metabolism [20,21]. The identification of known bioactive—tetradecanoic acid [antifungal, antioxidant] and nonadecane [antimicrobial]—reinforces the biochemical versatility of rhizosphere fungi.

Crude extracts exhibited broad-spectrum antibacterial effects against multidrug-resistant clinical isolates, with inhibition zones up to 31.7 mm. Fungal secondary metabolites disrupt bacterial cell walls, inhibit protein synthesis, or induce oxidative stress [22]. The pronounced activity of A. flavus extracts against Salmonella typhi and Klebsiella pneumoniae underscores their potential as novel antimicrobials. At 100 µg/mL, both extracts suppressed L. minor growth by ~70%, indicating the presence of phytotoxic compounds that may interfere with photosynthetic pigments or hormone signaling. Fungal terpenoids and alkaloids are known to induce oxidative damage and growth inhibition in aquatic plants, suggesting potential for bioherbicide development [23,24,25,26]. Aspergillus luchuensis extracts caused 70% mortality in Blattodea and 40% in Isoptera at 100 µg/mL, outperforming A. flavus in certain assays. Fungal metabolites such as indole diterpenoids and tetramic acids target insect nervous systems or digestive enzymes [27,28,29,30], and species-specific efficacy suggests distinct metabolite spectra.

Numerous metabolites that were inferred by GC-MS have been reported to have antibacterial, antioxidant, or insecticidal qualities in the past, which recommended that they may have contributed to the bioactivities that were observed. Tetradecanoic acid and n-hexadecanoic acid, for example, have well-established antibacterial, antifungal, and nematocidal qualities [31,32,33,34]. Both eicosane and nonadecane have showed inhibitory effects on insect pests and phytopathogenic fungi [35,36,37,38]. Similarly, 1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acid bis(2-ethylhexyl) ester and bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate showed larvicidal and antibacterial properties [39,40,41,42]. Even though correlation alone cannot prove causation, these activities backed by the literature advised that these metabolites probably have a role in the antibacterial and insecticidal effects seen in this investigation [43,44].

Notably, GC–MS spectrum library matching (NIST 2020) was used for compound identification in this investigation. This method offers a tentative chemical annotation but no conclusive structural confirmation [45]. The identities of the identified metabolites should therefore be regarded as tentative until confirmed by reliable standards or spectroscopic characterization (e.g., 1H/13C-NMR, HR-MS). This restriction is recognized in order to avoid interpreting the GC-MS data too broadly.

Alkaloids, polyketides, and peptides such gliotoxin, kojic acid, and aspergillic acid are examples of semi-polar or polar secondary metabolites that are typically represented under these analytical circumstances, whereas GC-MS preferentially detects volatile and non-polar chemicals. Such compounds are known to be synthesized by Aspergillus species, and they may play a significant role in the observed insecticidal and antibacterial properties.

Activation of silent gene clusters via epigenetic modulators or co-culture can unlock further metabolite diversity [46]. Integrating shotgun metabolomics, genome mining, and bioassay-guided fractionation will accelerate discovery of novel antibiotics, herbicides, and insecticides from rhizosphere fungi.

5. Conclusions

This study established a clear link between rhizosphere soil properties and the biosynthetic potential of Aspergillus luchuensis and A. flavus isolated from the rhizospheres of Withania coagulans and Justicia adhatoda. Variations in soil phosphorus, potassium, and pH influenced fungal metabolite production, leading to the identification of 55 previously unreported compounds from these sources for the first time through GC–MS analysis. Several metabolites, including tetradecanoic acid and nonadecane, exhibited strong antibacterial, phytotoxic, and insecticidal activities, with inhibition zones up to 31.7 mm against Salmonella typhi and 70% mortality against Blattodea. These results position rhizospheric Aspergillus species as promising biotechnological resources for the development of eco-friendly antimicrobial and agrochemical agents. Future studies integrating metabolomics, genomics, and bioassay-guided fractionation are essential to structurally characterize these compounds and validate their efficacy and safety for sustainable pharmaceutical and agricultural applications.

Author Contributions

A.M. and N.A.: Designed and supervised the project. S.F., A.M. and N.A.: Wrote the original manuscript. N.K., S.F. and A.K.: Revised the MS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| A. luchuensis | Aspergillus luchuensis |

| A. flavus | Aspergillus flavus |

| PDA | Potato Dextrose Agar |

| DNA | Dioxyribonucleic acid |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| MDR | Multi Drug Resistance |

References

- Philippot, L.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; Lemanceau, P.; van der Putten, W.H. Going back to the roots: The microbial ecology of the rhizosphere. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzyakov, Y.; Blagodatskaya, E. Microbial hotspots and hot moments in soil: Concept & review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 83, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N.; Jackson, R.B. The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrian, P.; Valášková, V. Degradation of cellulose by basidiomycetous fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 501–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, Á.T.; Speranza, M.; del Río, J.C.; Gutiérrez, A.; Ferreira, P. Biodegradation of lignocellulosics: Microbial, chemical, and enzymatic aspects of the fungal attack of lignin. Int. Microbiol. 2005, 8, 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Brakhage, A.A.; Schroeckh, V. Fungal secondary metabolites: Strategies to activate silent gene clusters. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2011, 48, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berestetskiy, A.; Hu, Q. The chemical ecology approach to reveal fungal metabolites for arthropod pest management. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, O.; Machida, M.; Hosoyama, A.; Goto, M.; Takahashi, T.; Futagami, T.; Takeuchi, M.; Gomi, K. Genome sequence of Aspergillus luchuensis NBRC 4314. DNA Res. 2016, 23, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amare, M.G.; Keller, N.P. Molecular mechanisms of Aspergillus flavus secondary metabolism and development. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2014, 66, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamekh, R.; Deniel, F.; Donot, C.; Jany, J.L.; Nodet, P.; Belabid, L. Isolation, identification and enzymatic activity of halotolerant and halophilic fungi from the Great Sebkha of Oran in Northwestern of Algeria. Mycobiology 2019, 47, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, V.; Patharajan, S.; Palani, P.; Spadaro, D. Modified simple protocol for efficient fungal DNA extraction highly. Glob. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 5, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Baazeem, A.; Almanea, A.; Manikandan, P.; Alorabi, M.; Vijayaraghavan, P.; Abdel- Hadi, A. In vitro antibacterial, antifungal, nematocidal and growth promoting activities of Trichoderma hamatum FB10 and its secondary metabolites. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wamala, S.P.; Mugimba, K.K.; Mutoloki, S.; Evensen, Ø.; Mdegela, R.; Byarugaba, D.K.; Sørum, H. Occurrence and antibiotic susceptibility of fish bacteria isolated from Oreochromis niloticus [Nile tilapia] and Clarias gariepinus [African catfish] in Uganda. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2018, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N. Exploring plant resilience through secondary metabolite profiling: Advances in stress response and crop improvement. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 4823–4837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimmino, A.; Masi, M.; Evidente, M.; Superchi, S.; Evidente, A. Fungal phytotoxins with potential herbicidal activity: Chemical and biological characterization. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2015, 32, 1629–1653. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, R.M.; Park, M.G.; Choi, J.Y.; Park, D.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Wang, M.; Je, Y.H. Insecticidal and insect growth regulatory activities of secondary metabolites from entomopathogenic fungi, Lecanicillium attenuatum. J. Appl. Entomol. 2020, 144, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, S.; Mehmood, A.; Ali, N.; Irshad, M.; Hussain, A.; Khan, N. Isolation and characterization of Aspergillus oryzae from Withania coagulans rhizosphere: Metabolite profiling and bioactivity assessment. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2025, 34, 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Zhong, Z.; Zhang, T.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Wu, S.; Xu, J. Synergistic degradation performance of UV/TiO2 photocatalysis and bio trickling filtration inoculated with Aspergillus sp. S1 for gaseous m-xylene. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2023, 98, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubraiz, N.; Bano, A.; Mahmood, T.; Khan, N. Microbial and plant assisted synthesis of cobalt oxide nanoparticles and their antimicrobial activities. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, M.G.; Badr, A.N.; El Sohaimy, S.A.; Asker, D.; Awad, T.S. Characterization of antifungal metabolites produced by novel lactic acid bacterium and their potential application as food bio preservatives. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2019, 64, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.N. Bioactive natural derivatives of phthalate ester. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2020, 40, 913–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finamore, A.; Palmery, M.; Bensehaila, S.; Peluso, I. Antioxidant, immunomodulating, and microbial-modulating activities of the sustainable and ecofriendly spirulina. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 8, e59316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.K.; Kar, B.R.; Deepthi, K.; Pallath, S.K.; Dakni, S.J.; Samal, P.; Sneha, T. Gas chromatography and mass spectroscopy analysis and phytochemical characterization of Aegle marmelos (Bael) leaf, Stem and its screening of antimicrobial activity. GSC Biol. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 8, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, S.K.; Basavarajappa, D.S.; Kumaraswamy, S.H.; Bepari, A.; Hiremath, H.; Nagaraja, S.K.; Nayaka, S. GC-MS Based Characterization, Antibacterial, Antifungal and Anti-Oncogenic Activity of Ethyl Acetate Extract of Aspergillus niger Strain AK-6 Isolated from Rhizospheric Soil. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 3733–3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholkamy, E.N.; Palsamy, S.; Raja, S.S.S.; Alarjani, K.M.; Alharbi, R.M.; Abdel- Raouf, N.; Habila, M.A. GC-MS Analysis and Bioactivity of Streptomyces sp. nkm1 Volatile Metabolites against some Phytopathogenic Fungi. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2023, 66, e23220626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.H.; Javaid, A. In vitro screening of Aspergillus spp. for their biocontrol potential against Macrophomina phaseolina. J. Plant Pathol. 2021, 103, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragunath, C.; Kumar, Y.A.S.; Kanivalan, I.; Radhakrishnan, S. Phytochemical screening and GC-MS analysis of bioactive constituents in the methanolic extract of Caulerpa racemosa (Forssk.) j. agardh and Padina boergesenii allender & kraft. Curr. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2020, 20, 380–393. [Google Scholar]

- Ikram, M.; Ali, N.; Jan, G.; Jan, F.G.; Pervez, R.; Romman, M.; Zainab, R.; Yasmin, H.; Khan, N. Isolation of endophytic fungi from halophytic plants and their identification and screening for auxin production and other plant growth promoting traits. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 4707–4723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, A.; Hussain, A.; Irshad, M.; Khan, N.; Hamayun, M.; Gul Afridi, S.I.; Lee, I.J. IAA and flavonoids modulates the association between maize roots and phytostimulant endophytic Aspergillus fumigatus greenish. J. Plant Interact. 2018, 13, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Octarya, Z.; Novianty, R.; Suraya, N.; Saryono, S. Antimicrobial activity and GC-MS analysis of bioactive constituents of Aspergillus fumigatus 269 isolated from Sungai Pinang Hot Spring, Riau, Indonesia. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 2021, 22, 1839–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhetso, T.; Shubharani, R.; Roopa, M.S.; Sivaram, V. Chemical constituents, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activity of Allium chinense G. Don. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 6, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albratty, M.; Alhazmi, H.A.; Meraya, A.M.; Najmi, A.; Alam, M.S.; Rehman, Z.; Moni, S.S. Spectral analysis and Antibacterial activity of the bioactive principles of Sargassum tenerrimum J. Agardh collected from the Red sea, Jazan, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Braz. J. Biol. 2021, 83, e249536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.E.; Ul-Hassan, Z.; Zeidan, R.; Al-Shamary, N.; Al-Yafei, T.; Alnaimi, H.; Jaoua, S. Biocontrol activity of Bacillus megaterium BM344-1 against toxigenic fungi. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 10984–10990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.R.; Salman, M.; Tariq, A.; Tawab, A.; Zahoor, M.K.; Naheed, S.; Ali, H. The Antibacterial and Larvicidal Potential of Bis-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. Molecules 2022, 27, 7220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S.A.; Salman, M.; Numan, M.; Javed, M.R.; Zubair, M.; Mustafa, G. Characterization of antifungal metabolites produced by Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus coryniformis isolated from rice rinsed water. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 1871–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.; Ali, N.; Jan, G.; Jan, F.G.; Romman, M.; Ishaq, M.; Islam, Y.; Khan, N. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of methanolic extract and fractions of Epilobium roseum (Schreb.) against bacterial strains. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonisi, S.; Okaiyeto, K.; Hoppe, H.; Mabinya, L.V.; Nwodo, U.U.; Okoh, A.I. Chemical constituents, antioxidant and cytotoxicity properties of Leonotis leonurus used in the folklore management of neurological disorders in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almustafa, H.I.; Yehia, R.S. Antioxidant, cytotoxic, and DNA damage protection activities of endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis neglecta isolated from Ziziphus spina-christi medicinal plant. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F.; Wang, P.; Lucardi, R.D.; Su, Z.; Li, S. Natural sources and bioactivities of 2, 4-di-tert-butylphenol and its analogs. Toxins 2020, 12, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piechowicz, B.; Kwiatek, A.; Sadło, S.; Zaręba, L.; Koziorowska, A.; Kloc, D.; Balawejder, M. Use of Gas Chromatography and SPME Extraction for the Differentiation between Healthy and Paenibacillus larvae Infected Colonies of Bee Brood—Preliminary Research. Agriculture 2023, 13, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, M.T.; Rabie, G.H.; Hamed, E.A. Biodegradation of low-density polyethylene (LDPE) using the mixed culture of Aspergillus carbonarius and A. fumigates. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 14556–14584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, Y.M.; Abdalla, S.A.; Shehata, A.S. Aspergillus flavus YRB2 from Thymelaea hirsuta (L.) Endl., a non-aflatoxigenic endophyte with ability to overexpress defense-related genes against Fusarium root rot of maize. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wash, P.; Yasmin, H.; Ullah, H.; Haider, W.; Khan, N.; Ahmad, A.; Mumtaz, S.; Hassan, M.N. Deciphering the genetics of antagonism and antimicrobial resistance in Bacillus velezensis HU-91 by whole genome analysis. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2023, 35, 102954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, B.; Dwivedi, K.D.; Chowhan, L.R. Review on synthesis and medicinal application of dihydropyrano [3, 2-b] pyrans and spiro-pyrano [3, 2- b] pyrans by employing the reactivity of 5-hydroxy-2-(hydroxymethyl)-4 H- pyran-4-one. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2022, 42, 5893–5937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, R.H.; Darwis, W.; Yudha, S.; Purnaningsih, I.; Siboro, R. Potential Antimicrobe Producer of Endophytic Bacteria from Yellow Root Plant (Arcangelisia flava (L.)) Originated from Enggano Island. Int. J. Microbiol. 2022, 2022, 6435202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brück, S.A.; Contato, A.G.; Gamboa-Trujillo, P.; de Oliveira, T.B.; Cereia, M.; de Moraes Polizeli, M.D.L.T. Prospection of Psychrotrophic Filamentous Fungi Isolated from the High Andean Paramo Region of Northern Ecuador: Enzymatic Activity and Molecular Identification. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).