Uncovering New Antimelanoma Strategies: Experimental Insights into Semisynthetic Pentacyclic Triterpenoids

Abstract

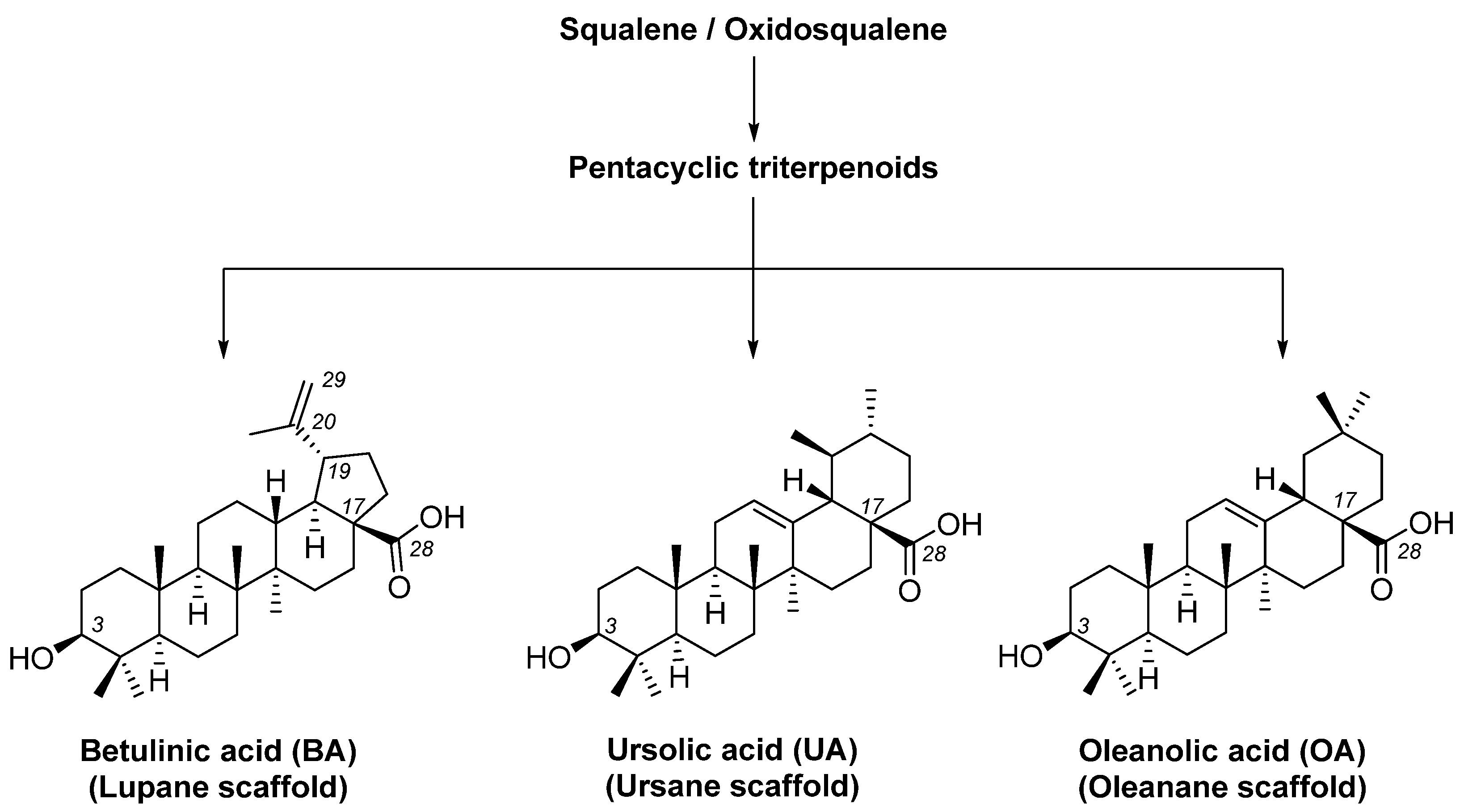

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Compounds and Their Synthesis

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. Cell Viability Assessment (MTT Assay)

2.4. Cell Cytotoxicity Assessment (LDH Assay)

2.5. Cell Migration Assay (Scratch Method)

2.6. Hoechst Nuclear Staining

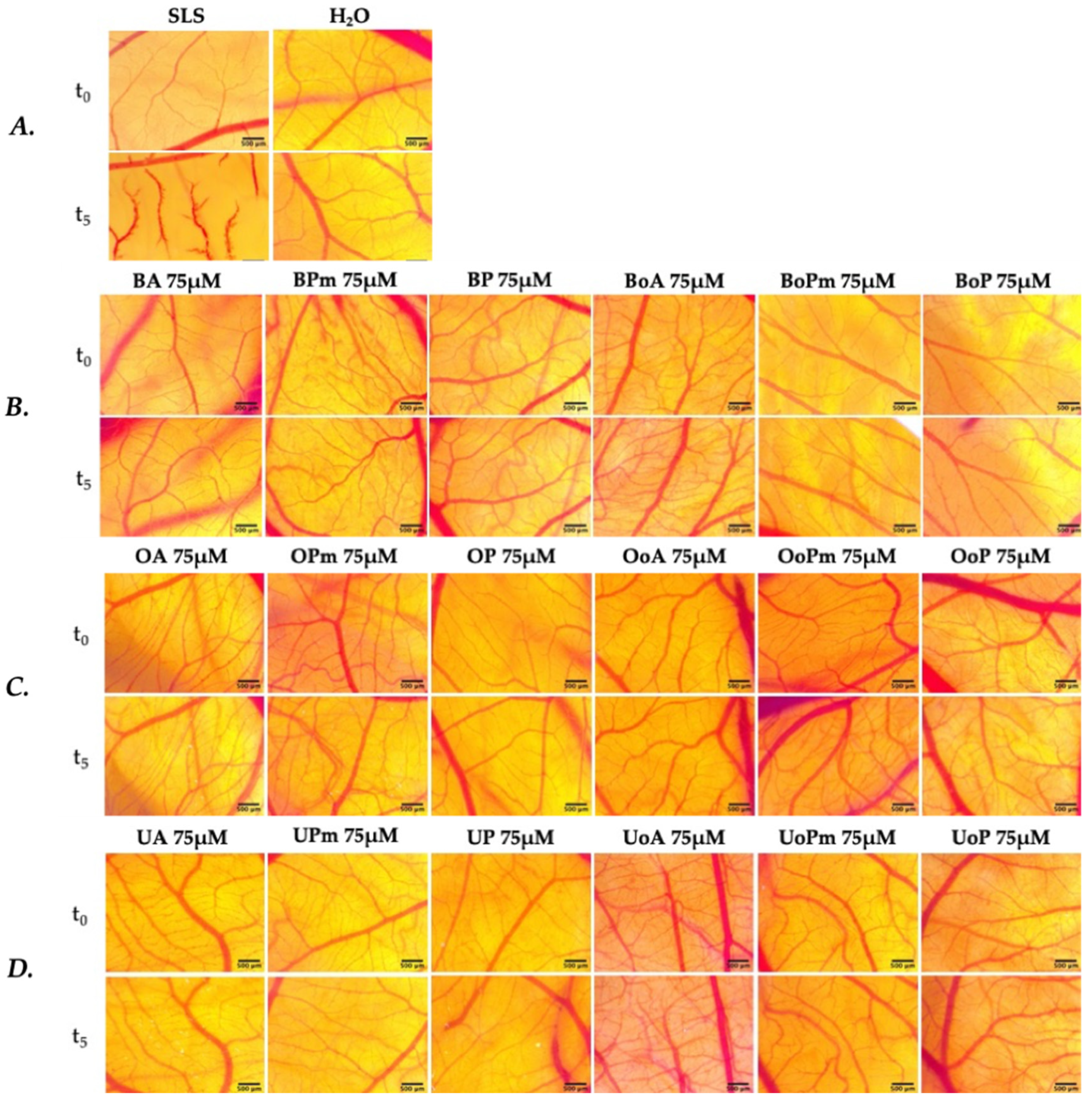

2.7. HET−CAM Assay

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

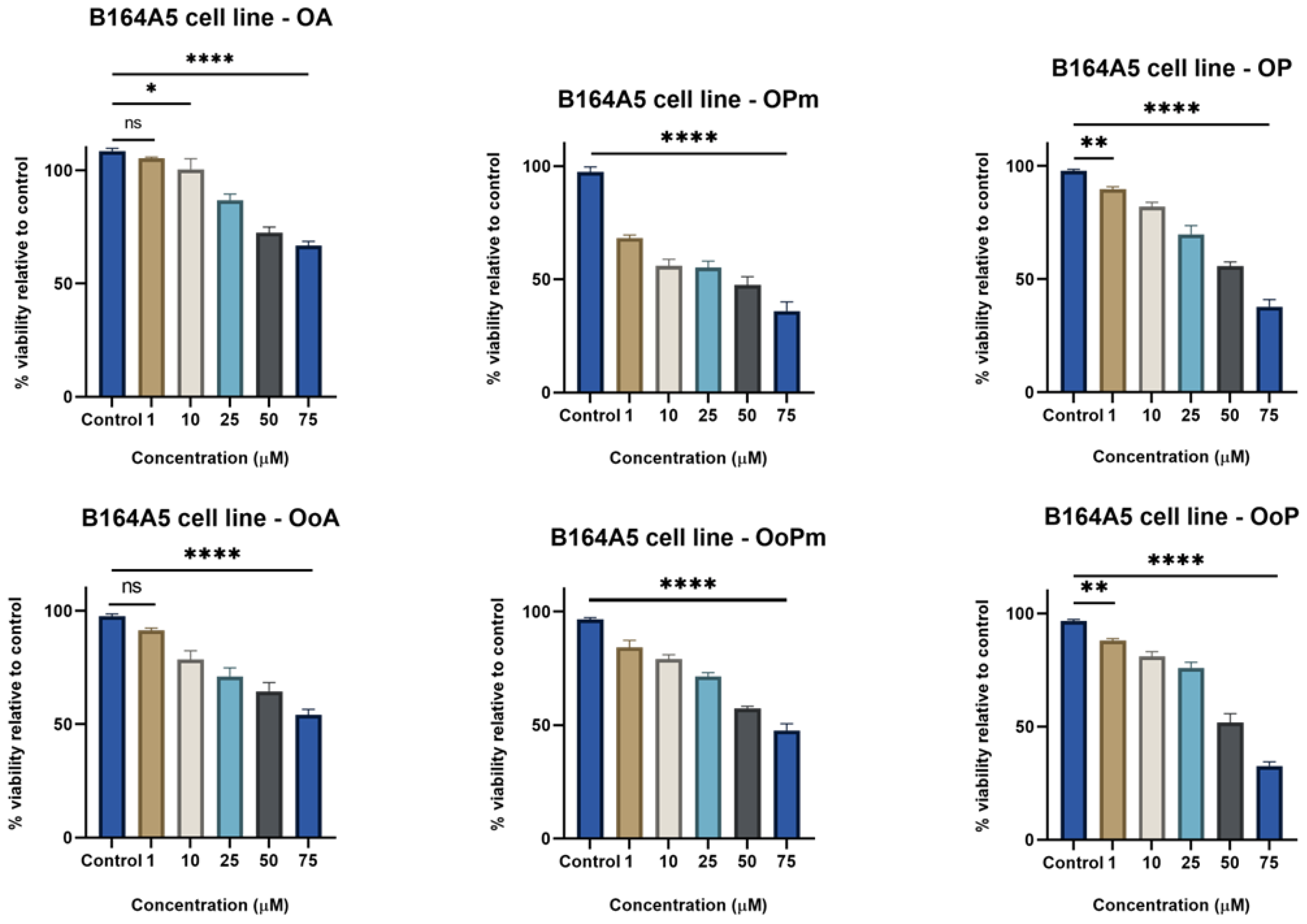

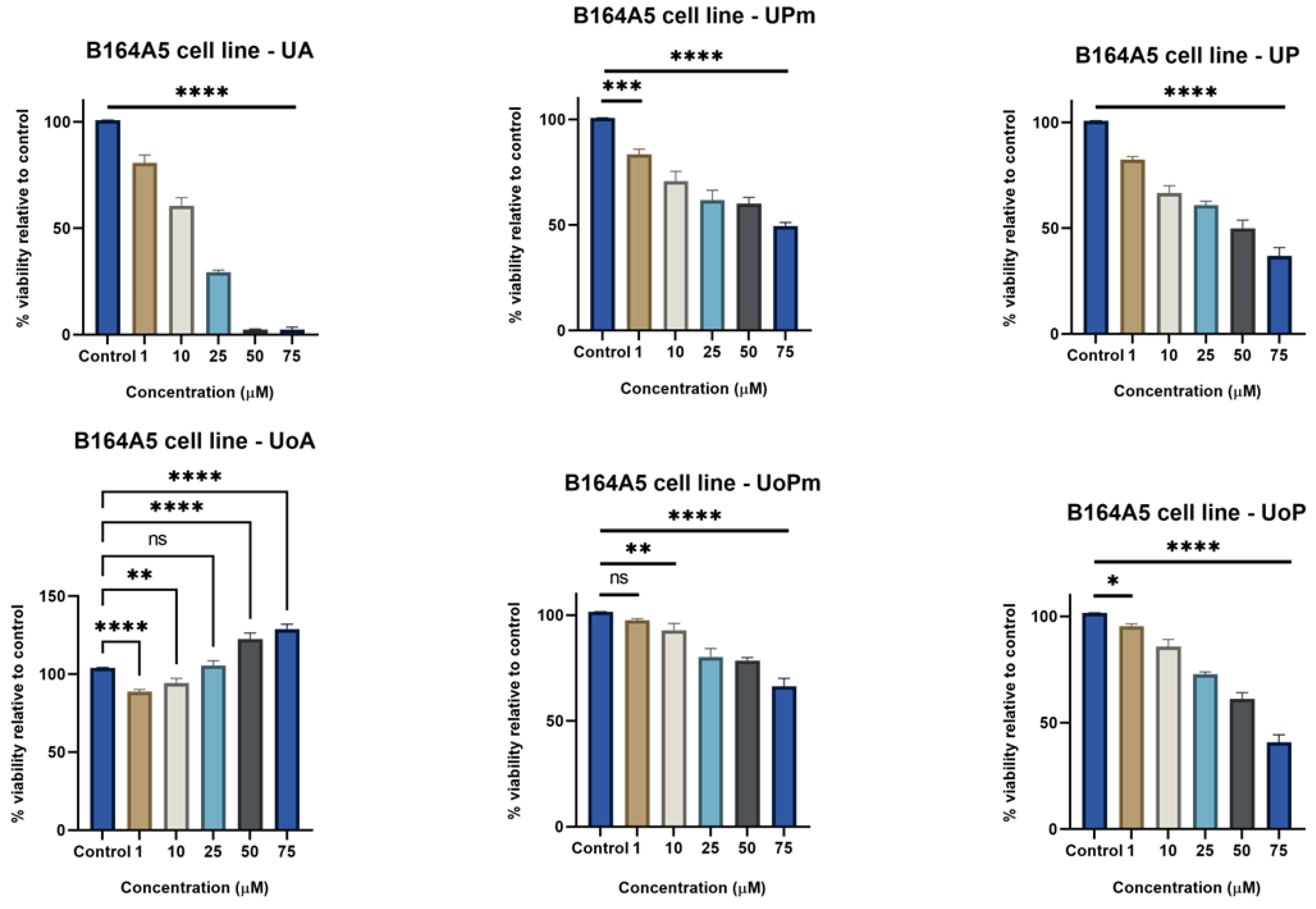

3.1. MTT Assay

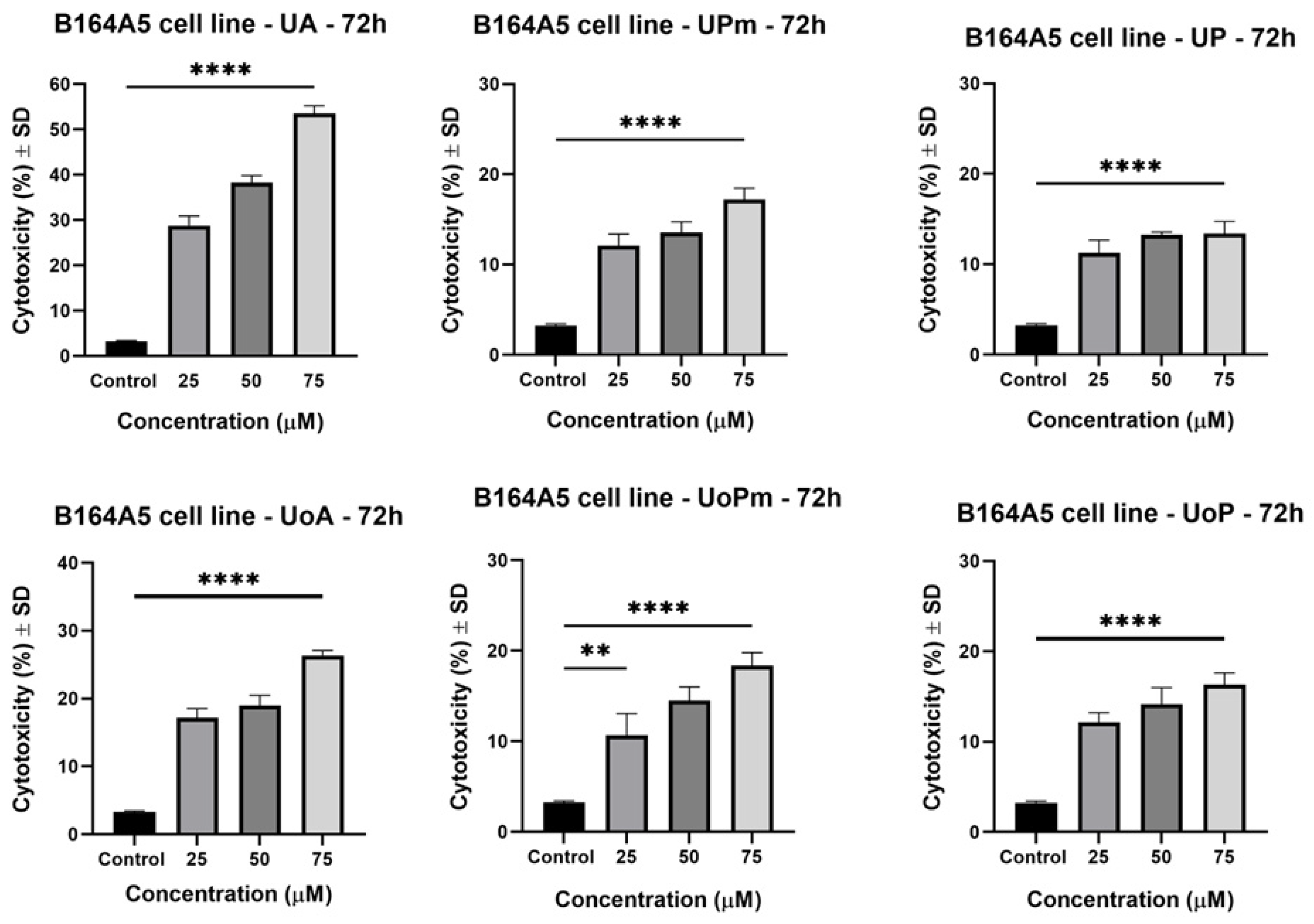

3.2. LDH Assay

3.3. Scratch Assay

3.4. Hoechst Staining

3.5. Irritative Potential in Ovo, Using the HET-CAM Assay

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Najmi, A.; Javed, S.A.; Al Bratty, M.; Alhazmi, H.A. Modern Approaches in the Discovery and Development of Plant-Based Natural Products and Their Analogues as Potential Therapeutic Agents. Molecules 2022, 27, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Süntar, I. Importance of Ethnopharmacological Studies in Drug Discovery: Role of Medicinal Plants. Phytochem. Rev. 2020, 19, 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdigaliyev, N.; Aljofan, M. An Overview of Drug Discovery and Development. Future Med. Chem. 2020, 12, 939–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, B.; Dhingra, A.K. Natural Products: A Lead for Drug Discovery and Development. Phyther. Res. 2021, 35, 4660–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.S.; Thangaraju, M.; Lokeshwar, B.L. Ursolic Acid Analogs as Potential Therapeutics for Cancer. Molecules 2022, 27, 8981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, S.; Smith, C.; Wernberg, J. Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Melanoma. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 100, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giavina-Bianchi, M.H.; Festa-Neto, C.; Sanches, J.A.; Teixeira, M.L.P.; Waldvogel, B.C. Worse Survival of Invasive Melanoma Patients in Men and “de Novo” Lesions. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2020, 95, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, M.; Singh, D.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Vaccarella, S.; Meheus, F.; Cust, A.E.; De Vries, E.; Whiteman, D.C.; Bray, F. Global Burden of Cutaneous Melanoma in 2020 and Projections to 2040. JAMA Dermatol. 2022, 158, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conforti, C.; Zalaudek, I. Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Melanoma: A Review. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2021, 11, e2021161S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G.V.; Swetter, S.M.; Menzies, A.M.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Scolyer, R.A. Cutaneous Melanoma. Lancet 2023, 402, 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, R.W.; Fisher, D.E. Treatment of Advanced Melanoma in 2020 and Beyond. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saginala, K.; Barsouk, A.; Aluru, J.S.; Rawla, P.; Barsouk, A.; Sanguedolce, F.; Murray-Stewart, T. Epidemiology of Melanoma. Med. Sci. 2021, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W.; Wang, H.; Li, C. Signal Pathways of Melanoma and Targeted Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.; Rodrigues, C.M.P.; Gaspar, M.M.; Reis, C.P. Melanoma Management: From Epidemiology to Treatment and Latest Advances. Cancers 2022, 14, 4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Lu, J.J.; Ding, J. Natural Products in Cancer Therapy: Past, Present and Future. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2021, 11, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, S.; Khan, K.; Hafeez, A.; Irfan, M.; Armaghan, M.; Rahman, A.U.; Gürer, E.S.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Butnariu, M.; Bagiu, I.C.; et al. Ursolic Acid: A Natural Modulator of Signaling Networks in Different Cancers. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaković-Vidović, S.; Dariš, B.; Knez, Ž.; Vidović, K.; Oprić, D.; Ferk, P. Antiproliferative Activity of Selected Triterpene Acids from Rosemary on Metastatic Melanoma Cell Line Wm-266-4. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 9, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudzik, M.; Korzonek-Szlacheta, I.; Król, W. Triterpenes as Potentially Cytotoxic Compounds. Molecules 2015, 20, 1610–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, M.K.; Dai, X.; Kumar, A.P.; Tan, B.K.H.; Sethi, G.; Bishayee, A. Ursolic Acid in Cancer Prevention and Treatment: Molecular Targets, Pharmacokinetics and Clinical Studies. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2013, 85, 1579–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bildziukevich, U.; Wimmerová, M.; Wimmer, Z. Saponins of Selected Triterpenoids as Potential Therapeutic Agents: A Review. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, Z.; Wimmer, Z. Selected Plant Triterpenoids and Their Amide Derivatives in Cancer Treatment: A Review. Phytochemistry 2022, 203, 113340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, H.; Xiong, Y. Recent Advances in Antiviral Activities of Triterpenoids. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, L.; Xu, H.; Huang, C.; Wang, C.; Wang, R.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, H. A Link Between Chemical Structure and Biological Activity in Triterpenoids. Recent Pat. Anti-Cancer Drug Discov. 2021, 17, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, N.A.J.C.; Pirson, L.; Edelberg, H.; Miranda, L.M.; Loira-Pastoriza, C.; Preat, V.; Larondelle, Y.; André, C.M. Pentacyclic Triterpene Bioavailability: An Overview of In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. Molecules 2017, 22, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, R.; Aruna, A.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, M.; Shivakumar, M.S.; Natarajan, D. Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Potential of Bioactive Molecules Ursolic Acid and Thujone Isolated from Memecylon Edule and Elaeagnus indica and Their Inhibitory Effect on Topoisomerase II by Molecular Docking Approach. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 8716927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczyk-Cwynar, B.; Leśków, A.; Szczuka, I.; Zaprutko, L.; Diakowska, D. The Effect of Oleanolic Acid and Its Four New Semisynthetic Derivatives on Human MeWo and A375 Melanoma Cell Lines. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.W.C.; Soon, C.Y.; Tan, J.B.L.; Wong, S.K.; Hui, Y.W. Ursolic Acid: An Overview on Its Cytotoxic Activities against Breast and Colorectal Cancer Cells. J. Integr. Med. 2019, 17, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Li, T.; Gong, E.S.; Liu, R.H. Antiproliferative Activity of Ursolic Acid in MDA-MB-231 Human Breast Cancer Cells through Nrf2 Pathway Regulation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 7404–7415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hordyjewska, A.; Ostapiuk, A.; Horecka, A.; Kurzepa, J. Betulin and Betulinic Acid: Triterpenoids Derivatives with a Powerful Biological Potential. Phytochem. Rev. 2019, 18, 929–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewska-Łuczka, P.; Cabaj, J.; Bąk, W.; Bargieł, J.; Grabarska, A.; Góralczyk, A.; Łuszczki, J.J. Additive Interactions between Betulinic Acid and Two Taxanes in In Vitro Tests Against Four Human Malignant Melanoma Cell Lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csuk, R. Betulinic Acid and Its Derivatives: A Patent Review (2008–2013). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2014, 24, 913–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali-Seyed, M.; Jantan, I.; Vijayaraghavan, K.; Bukhari, S.N.A. Betulinic Acid: Recent Advances in Chemical Modifications, Effective Delivery, and Molecular Mechanisms of a Promising Anticancer Therapy. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2016, 87, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebscher, G.; Vanchangiri, K.; Mueller, T.; Feige, K.; Cavalleri, J.M.V.; Paschke, R. In Vitro Anticancer Activity of Betulinic Acid and Derivatives Thereof on Equine Melanoma Cell Lines from Grey Horses and Invivo Safety Assessment of the Compound NVX-207 in Two Horses. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2016, 246, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebenek, E.; Chodurek, E.; Orchel, A.; Dzierzewicz, Z.; Boryczka, S. Antiproliferative Activity of Novel Acetylenic Derivatives of Betulin Against G-361 Human Melanoma Cells. Acta Pol. Pharm.-Drug Res. 2015, 72, 669–703. [Google Scholar]

- Grudzinska, M.; Stachnik, B.; Galanty, A.; Sołtys, A.; Podolak, I. Progress in Antimelanoma Research of Natural Triterpenoids and Their Derivatives: Mechanisms of Action, Bioavailability Enhancement and Structure Modifications. Molecules 2023, 28, 7763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlala, S.; Oyedeji, A.O.; Gondwe, M.; Oyedeji, O.O. Ursolic Acid and Its Derivatives as Bioactive Agents. Molecules 2019, 24, 2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer-Dubowska, W.; Narożna, M.; Krajka-Kuźniak, V. Anti-Cancer Potential of Synthetic Oleanolic Acid Derivatives and Their Conjugates with Nsaids. Molecules 2021, 26, 4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.S.; Yoo, E.S.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, J.H.; Han, S.H.; Jung, S.H.; Jung, G.H.; Jung, J.Y. Anticancer Effects of Oleanolic Acid on Human Melanoma Cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2021, 347, 109619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Es-saady, D.; Simon, A.; Ollier, M.; Maurizis, J.C.; Chulia, A.J.; Delage, C. Inhibitory Effect of Ursolic Acid on B16 Proliferation Through Cell Cycle Arrest. Cancer Lett. 1996, 106, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Ding, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Fang, W.; Chen, X. Anti-Tumor Activity of a 3-Oxo Derivative of Oleanolic Acid. Cancer Lett. 2006, 233, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugiņina, J.; Kroškins, V.; Lācis, R.; Fedorovska, E.; Demir, Ö.; Dubnika, A.; Loca, D.; Turks, M. Synthesis and Preliminary Cytotoxicity Evaluation of Water Soluble Pentacyclic Triterpenoid Phosphonates. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.R.; Pan, B.W.; Cai, J.; Liu, L.J.; Dong, Z.C.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, T.T.; Shi, Y. Construction, Structural Modification, and Bioactivity Evaluation of Pentacyclic Triterpenoid Privileged Scaffolds in Active Natural Products. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 39436–39461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsepaeva, O.V.; Nemtarev, A.V.; Grigor’eva, L.R.; Mironov, V.F. Synthesis of C(28)-Linker Derivatives of Betulinic Acid Bearing Phosphonate Group. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2021, 70, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista-Duharte, A.; Jorge Murillo, G.; Pérez, U.M.; Tur, E.N.; Portuondo, D.F.; Martínez, B.T.; Téllez-Martínez, D.; Betancourt, J.E.; Pérez, O. The Hen’s Egg Test on Chorioallantoic Membrane: An Alternative Assay for the Assessment of the Irritating Effect of Vaccine Adjuvants. Int. J. Toxicol. 2016, 35, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugiņina, J.; Linden, M.; Bazulis, M.; Kumpiņš, V.; Mishnev, A.; Popov, S.A.; Golubeva, T.S.; Waldvogel, S.R.; Shults, E.E.; Turks, M. Electrosynthesis of Stable Betulin-Derived Nitrile Oxides and Their Application in Synthesis of Cytostatic Lupane-Type Triterpenoid-Isoxazole Conjugates. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 2021, 2557–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Health Security Agency. Culture Collection, B16 Melanoma 4A5. Available online: https://www.culturecollections.org.uk/nop/product/b16-melanoma-4a5 (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Apostolova, S.; Georgieva, I.; Ossowicz-Rupniewska, P.; Klebeko, J.; Todinova, S.; Tzoneva, R.; Guncheva, M. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assessment of Betulinic Acid Organic Salts on Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Sci 2025, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magyari-Pavel, I.Z.; Moacă, E.A.; Avram, Ș.; Diaconeasa, Z.; Haidu, D.; Ștefănuț, M.N.; Rostas, A.M.; Muntean, D.; Bora, L.; Badescu, B.; et al. Antioxidant Extracts from Greek and Spanish Olive Leaves: Antimicrobial, Anticancer and Antiangiogenic Effects. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarău, O.S.; Moacă, E.A.; Semenescu, A.D.; Dumitru, R.; Jijie, A.R.; Poenaru, M.; Dehelean, C.A.; Chevereşan, A. Physicochemical and Toxicological Screening of Silver Nanoparticle Biosynthesis from Punica Granatum Peel Extract. Inorganics 2024, 12, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. ICCVAM Test Method Evaluation Report: Current Validation Status of In Vitro Test Methods Proposed for Identifying Eye Injury Hazard Potential of Chemicals and Product; NIEHS: Durham, NC, USA, 2010; Volume 2.

- Avram, Ș.; Bora, L.; Vlaia, L.L.; Muț, A.M.; Olteanu, G.E.; Olariu, I.; Magyari-Pavel, I.Z.; Minda, D.; Diaconeasa, Z.; Sfirloaga, P.; et al. Cutaneous Polymeric-Micelles-Based Hydrogel Containing Origanum vulgare L. Essential Oil: In Vitro Release and Permeation, Angiogenesis, and Safety Profile In Ovo. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribatti, D.; Annese, T.; Tamma, R. The Use of the Chick Embryo CAM Assay in the Study of Angiogenic Activiy of Biomaterials. Microvasc. Res. 2020, 131, 104026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luepke, N.P. Hen’s Egg Chorioallantoic Membrane Test for Irritation Potential. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1985, 23, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, C.C.; Grenho, L.; Gomes, P.S.; Quadros, P.A.; Fernandes, M.H. Nano-Hydroxyapatite in Oral Care Cosmetics: Characterization and Cytotoxicity Assessment. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Similie, D.U.; Bora, L.; Avram, S.; Turks, M.; Muntean, D.; Danciu, C. Assessment of the Antiproliferative, Cytotoxic, Antimigratory, Antimicrobial, and Irritative Potential of Novel Phosphonate Derivatives of Betulinic Acid. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Interdisciplinary Approaches and Emerging Trends in Pharmaceutical Doctoral Research: Innovation and Integration, Timisoara, Romania, 7–9 July 2025; pp. 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombrea, A.; Scurtu, A.D.; Avram, S.; Pavel, I.Z.; Turks, M.; Lugiņina, J.; Peipiņš, U.; Dehelean, C.A.; Soica, C.; Danciu, C. Anticancer Potential of Betulonic Acid Derivatives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soica, C.; Danciu, C.; Savoiu-Balint, G.; Borcan, F.; Ambrus, R.; Zupko, I.; Bojin, F.; Coricovac, D.; Ciurlea, S.; Avram, S.; et al. Betulinic Acid in Complex with a Gamma-Cyclodextrin Derivative Decreases Proliferation and In Vivo Tumor Development of Non-Metastatic and Metastatic B164A5 Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 8235–8255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farcas, C.G.; Moaca, E.A.; Dragoi, R.; Vaduva, D.B.; Marcovici, I.; Mihali, C.V.; Loghin, F. Preliminary Results of Betulinic Acid-Loaded Magnetoliposomes—A Potential Approach to Increase Therapeutic Efficacy in Melanoma. Rev. Chim. 2019, 70, 3372–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombrea, A.; Watz, C.G.; Bora, L.; Dehelean, C.A.; Diaconeasa, Z.; Dinu, S.; Turks, M.; Lugiņina, J.; Peipiņš, U.; Danciu, C. Enhanced Cytotoxicity and Antimelanoma Activity of Novel Semisynthetic Derivatives of Betulinic Acid with Indole Conjugation. Plants 2024, 13, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombrea, A.; Semenescu, A.D.; Magyari-Pavel, I.Z.; Turks, M.; Lugiņina, J.; Peipiņš, U.; Muntean, D.; Dehelean, C.A.; Dinu, S.; Danciu, C. Comparison of In Vitro Antimelanoma and Antimicrobial Activity of 2,3-Indolo-Betulinic Acid and Its Glycine Conjugates. Plants 2023, 12, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drag-Zalesińska, M.; Drag, M.; Poreba, M.; Borska, S.; Kulbacka, J.; Saczko, J. Anticancer Properties of Ester Derivatives of Betulin in Human Metastatic Melanoma Cells (Me-45). Cancer Cell Int. 2017, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.J.; Liu, M.C.; Xiang, H.M.; Zhao, Q.; Xue, W.; Yang, S. Synthesis and In Vitro Antitumor Evaluation of Betulin Acid Ester Derivatives as Novel Apoptosis Inducers. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 102, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stammer, R.M.; Kleinsimon, S.; Rolff, J.; Jäger, S.; Eggert, A.; Seifert, G.; Delebinski, C.I. Synergistic Antitumour Properties of ViscumTT in Alveolar Rhabdomyosarcoma. J. Immunol. Res. 2017, 2017, 4874280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, X.; Chen, L.; Ouyang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Qiu, P.; Su, X.; Dou, Y.; Tang, L.; Yan, M.I.N.; Zhang, H.; et al. Pregnenolone, a Cholesterol Metabolite, Induces Glioma Cell Apoptosis via Activating Extrinsic and Intrinsic Apoptotic Pathways. Oncol. Lett. 2014, 8, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oprean, C.; Ivan, A.; Bojin, F.; Cristea, M.; Soica, C.; Drăghia, L.; Caunii, A.; Paunescu, V.; Tatu, C. Selective in Vitro Anti-Melanoma Activity of Ursolic and Oleanolic Acids. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2018, 28, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, T.; Boyd, L.; Rivas, F. Triterpenoids as Reactive Oxygen Species Modulators of Cell Fate. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 35, 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Jiang, W.; Ou, M.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zheng, Q.; Wu, F.; Wang, L.; et al. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel Ursolic Acid Derivatives as Potential Anticancer Prodrugs. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2015, 86, 1397–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahnt, M.; Hoenke, S.; Fischer, L.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Csuk, R. Synthesis and Cytotoxicity Evaluation of DOTA-Conjugates of Ursolic Acid. Molecules 2019, 24, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqathama, A.; Shao, L.; Bader, A.; Khondkar, P.; Gibbons, S.; Prieto, J.M. Differential Anti-Proliferative and Anti-Migratory Activities of Ursolic Acid, 3-O-Acetylursolic Acid and Their Combination Treatments with Quercetin on Melanoma Cells. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.; Lee, S.Y. Therapeutic Potential of Ursonic Acid: Comparison with Ursolic Acid. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan, A.; Mioc, M.; Mioc, A.; Gogulescu, A.; Mardale, G.; Avram, Ș.; Maksimović, T.; Mara, B.; Șoica, C. Cytotoxic Potential of Betulinic Acid Fatty Esters and Their Liposomal Formulations: Targeting Breast, Colon, and Lung Cancer Cell Lines. Molecules 2024, 29, 3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazakova, O.; Șoica, C.; Babaev, M.; Petrova, A.; Khusnutdinova, E.; Poptsov, A.; Macașoi, I.; Drăghici, G.; Avram, Ş.; Vlaia, L.; et al. 3-Pyridinylidene Derivatives of Chemically Modified Lupane and Ursane Triterpenes as Promising Anticancer Agents by Targeting Apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazakova, O.; Mioc, A.; Smirnova, I.; Baikova, I.; Voicu, A.; Vlaia, L.; Macașoi, I.; Mioc, M.; Drăghici, G.; Avram, Ş.; et al. Novel Synthesized N-Ethyl-Piperazinyl-Amides of C2-Substituted Oleanonic and Ursonic Acids Exhibit Cytotoxic Effects through Apoptotic Cell Death Regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

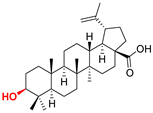

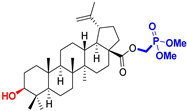

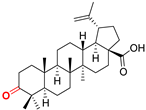

| Natural Product Class | Natural Product Standard | Semi-Synthetic Phosphonate Methyl Ester | Semi-Synthetic Phosphonate Sodium Salt |

|---|---|---|---|

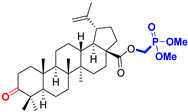

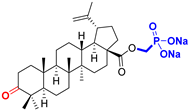

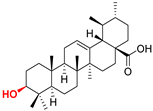

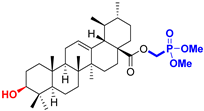

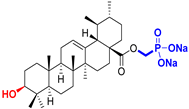

| Lupane type triterpenoids |  BA Betulinic acid CAS: 472-15-1 |  BPm (17 S)-17-(((dimethoxyphosphoryl)methoxy)carbonyl)-3β-hydroxy-28-norlup-20(29)-ene |  BP sodium (3β-hydroxy-(17R)-17-28-norlup-20(29)-en)-2-oxoethyl-phosphonate |

BoA Betulonic acid CAS: 4481-62-3 |  BoPm 3-oxo-(17 S)-17-(((dimethoxyphosphoryl)methoxy)carbonyl)-28-norlup-20(29)-ene |  BoP sodium (3-oxo-(17R)-17-28-norlup-20(29)-en)-2-oxoethyl-phosphonate | |

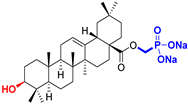

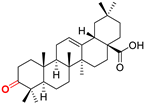

| Oleanane type triterpenoids |  OA Oleanolic acid CAS: 508-02-1 |  OPm (17 S)-17-(((dimethoxyphosphoryl)methoxy)carbonyl)-3β-hydroxy-28-norolean-12(13)-ene |  OP sodium (3β-hydroxy-(17R)-17-28-norolean-12(13)-en)-2-oxoethyl-phosphonate |

OoA Oleanonic acid CAS: 17990-42-0 |  OoPm 3-oxo-(17 S)-17-(((dimethoxyphosphoryl)methoxy)carbonyl)-28-norolean-12(13)-ene |  OoP sodium (3-oxo-(17R)-17-28-norolean-12(13)-en)-2-oxoethyl-phosphonate | |

| Ursane type triterpenoids |  UA Ursolic acid CAS: 77-52-1 |  UPm (17 S)-17-(((dimethoxyphosphoryl)methoxy)carbonyl)-3β-hydroxy-28-norurs-12(13)-ene |  UP sodium (3β-hydroxy-(17R)-17-28-norurs-12(13)-en)-2-oxoethyl-phosphonate |

UoA Ursonic acid CAS: 6246-46-4 |  UoPm 3-oxo-(17 S)-17-(((dimethoxyphosphoryl)methoxy)carbonyl)-28-norurs-12(13)-ene |  UoP sodium (3-oxo-(17R)-17-28-norurs-12(13)-en)-2-oxoethyl-phosphonate |

| Triterpenic Acid C(17)-COOH Series (μM) | Triterpenic Methylphosphonate C(17)-C(O)OCH2P(O)(OMe)2 Series (μM) | Triterpenic Methylphosphonate C(17)-C(O)OCH2P(O)(ONa)2 Series (μM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA | 26.68 | BPm | 143.70 | BP | 57.04 |

| BoA | 100.60 | BoPm | 82.60 | BoP | 108.8 |

| OA | 118.9 | OPm | 29.05 | OP | 54.50 |

| OoA | 76.25 | OoPm | 88.92 | OoP | 49.31 |

| UA | 12.57 | UPm | 55.35 | UP | 40.94 |

| UoA | - | UoPm | 199.9 | UoP | 62.58 |

| Samples | Irritation Score (IS) | Type of Effect |

|---|---|---|

| SLS 0.5% | 15.74 ± 0.52 | strong irritant |

| H2O dist. | 0 ± 0 | non-irritant |

| All tested pentacyclic triterpenoids (BA, BPm, BP BoA, BoPm, BoP OA, OPm, OP OoA, OoPm, OoP UA, UPm, UP UoA, UoPm, UoP) | 0 ± 0 | non-irritant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ungureanu, D.; Bora, L.; Chiriac, S.D.; Avram, Ș.; Minda, D.; Lugiņina, J.; Kroškins, V.; Turks, M.; Magyari-Pavel, I.Z.; Dinu, Ș.; et al. Uncovering New Antimelanoma Strategies: Experimental Insights into Semisynthetic Pentacyclic Triterpenoids. Life 2025, 15, 1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121884

Ungureanu D, Bora L, Chiriac SD, Avram Ș, Minda D, Lugiņina J, Kroškins V, Turks M, Magyari-Pavel IZ, Dinu Ș, et al. Uncovering New Antimelanoma Strategies: Experimental Insights into Semisynthetic Pentacyclic Triterpenoids. Life. 2025; 15(12):1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121884

Chicago/Turabian StyleUngureanu (Similie), Diana, Larisa Bora, Sorin Dan Chiriac, Ștefana Avram, Daliana Minda, Jevgeņija Lugiņina, Vladislavs Kroškins, Māris Turks, Ioana Zinuca Magyari-Pavel, Ștefania Dinu, and et al. 2025. "Uncovering New Antimelanoma Strategies: Experimental Insights into Semisynthetic Pentacyclic Triterpenoids" Life 15, no. 12: 1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121884

APA StyleUngureanu, D., Bora, L., Chiriac, S. D., Avram, Ș., Minda, D., Lugiņina, J., Kroškins, V., Turks, M., Magyari-Pavel, I. Z., Dinu, Ș., Dehelean, C. A., & Danciu, C. (2025). Uncovering New Antimelanoma Strategies: Experimental Insights into Semisynthetic Pentacyclic Triterpenoids. Life, 15(12), 1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121884