Abstract

Gout is an inflammatory arthritis triggered by monosodium urate crystal deposition, especially in obese patients. However, distinctions between the characteristics of obese and non-obese patients with gout remain unclear. We aimed to investigate the clinical differences by body mass index (BMI) with gout. We conducted a single-center retrospective cross-sectional study of 269 patients with gout from March 2020 to May 2024. Patients were classified into two groups: underweight/normal BMI and overweight/obesity. Baseline demographics, laboratory data, and clinical outcomes were compared between these groups. Stepwise logistic regression analysis was performed to identify predictors of underweight/normal BMI in gout patients. The underweight/normal BMI group included 35 patients (13.0%), characterized by older age, a higher proportion of females, and a lower prevalence of hypertension and alcohol consumption. This group also demonstrated lower uric acid, lipid profile, and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels but had a higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Logistic regression analysis identified female sex (odds ratio [OR] 3.831, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.254–11.705, p = 0.018), presence of hypertension (OR 0.367, 95% CI 0.166–0.809, p = 0.013), total cholesterol (OR 0.990, 95% CI 0.982–0.999, p = 0.031), and ALT (OR 0.967, 95% CI 0.941–0.995, p = 0.019) as significant predictors of underweight/normal BMI gout. Understanding these characteristics may improve the identification of underweight/normal BMI subgroups, leading to improved approaches for gout management.

1. Introduction

Gout is an inflammatory arthritis caused by monosodium urate (MSU) crystal deposition, leading to acute and recurrent inflammation in affected joints and soft tissue [1,2]. While the first metatarsophalangeal joint is most commonly involved, gout can also affect the ankles, knees, elbows, wrists, and fingers [3]. Recurrent gout attacks can result in significant disability and may lead to destructive arthropathy [4]. Hyperuricemia—defined as serum uric acid levels of ≥7 mg/dL in males and ≥6 mg/dL in females—is a representative laboratory finding in patients with gout [5]. An interplay of environmental and genetic factors drives the elevation of uric acid levels in circulation, and subsequent MSU crystal formation, which are key events in gout pathogenesis [1,3,6]. The diagnosis typically requires the presence of suggestive symptoms or radiographic findings and elevated uric acid levels. With the global burden of gout rising, an estimated 95.8 million individuals may be affected by 2050 [7], prompting increased interest in characterizing patients with gout clinically.

Recently, there has been a remarkable increase in the obese population, affecting over 650 million adults worldwide [8]. In the United States alone, more than 42% of adults are now classified as having obesity [9]. The rise has significantly contributed to the prevalence of other metabolic disorders, including gout. Unbalanced dietary habits commonly found in obese individuals, such as the consumption of foods high in purines and fructose, have been identified as important contributors to hyperuricemia [10]. Furthermore, obesity itself is a risk factor for gout by promoting uric acid production and reducing renal excretion [11,12]. However, despite this strong correlation, gout is not limited to the obese population. Non-obese patients may develop gout through alternative pathogenic pathways, including genetic susceptibility, renal dysfunction, or other comorbid conditions [13,14,15]. Clinically, gout is often regarded as a disease of obesity, and the risk in non-obese individuals may be underestimated, potentially leading to delayed diagnosis or suboptimal management. Therefore, non-obese patients with gout may represent a distinct subgroup with different demographic or metabolic profiles. To the best of our knowledge, few studies have investigated their clinical characteristics. Therefore, we aimed to analyze differences in patient characteristics and clinical outcomes between underweight/normal body mass index (BMI) and overweight/obese patients. We hypothesized that gout patients with an underweight/normal BMI would exhibit a less pronounced metabolic syndrome profile and distinct demographic and laboratory outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study by analyzing the medical records of patients diagnosed with gout who visited the rheumatology clinic (either as outpatients or inpatients) at our hospital between March 2020 and May 2024. The diagnosis of gout was made according to the 1977 criteria of the American Rheumatism Association [16]. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (i) first-time visitors to our rheumatology clinic, (ii) patients not currently taking uric acid-lowering medications, (iii) patients with a comprehensive medical history available, including BMI, current alcohol consumption, and smoking status, and (iv) patients with available routine laboratory results, including blood cell count and biochemical tests, as described in Section 2.2 (“Investigated variables”). The enrolled patients were categorized into two groups based on the WHO Asia–Pacific BMI classification, which defines 23 kg/m2 as the threshold for increased cardiometabolic risk in Asian populations and is widely applied in large epidemiologic studies and national screening programs in Republic of Korea [16,17].

2.2. Investigated Variables

Patient demographic data were collected at the initial visit, including age, sex, BMI, current alcohol consumption, smoking status, and diagnosis of new-onset disease (defined as disease onset within one month). Medical comorbidities were also noted, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), and dyslipidemia. Hypertension was identified by either the use of antihypertensive medications or a measured blood pressure of ≥140/90 mmHg, DM was determined by the use of anti-diabetic medications or a glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level of ≥6.5%, while dyslipidemia was diagnosed based on the use of anti-dyslipidemic medications or in accordance with the proposed criteria by the Korea National Health Screening Program [18]. For clinical outcomes, the incidence of gout flares and severe flares requiring hospitalization were investigated among those with one-year follow-up data.

All laboratory variables were measured using blood samples obtained at first hospital visit for diagnostic evaluation. Routine laboratory results included white blood cell (WBC) count, C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), serum creatinine, serum uric acid, total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), triglycerides, HbA1c, fasting glucose, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Continuous data were presented as means with standard deviations and categorical data as counts and percentages. Comparisons between the underweight/normal BMI and overweight/obesity groups were conducted using Student’s t-test, chi-square test, or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Pearson or Spearman correlation analyses were used to evaluate the relationship between BMI and the investigated variables in each group. Furthermore, univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed using a stepwise variable selection method, with variables entered at p < 0.05 and removed at p < 0.05, thereby identifying the predictors associated with underweight/normal BMI in patients with gout. Additionally, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were performed to calculate the area under the curve (AUC) for classifying underweight/normal-BMI patients with gout. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), with a significance level set at a two-tailed p-value < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Baseline Patient Characteristics Between the Two Groups

Among the 269 eligible patients with gout, 250 were male (92.9%) and 19 were female (7.1%). The mean age of the study population was 47.6 years, and the mean BMI was 27.4 kg/m2. Of these, 35 (13.0%) patients were grouped as the underweight/normal BMI group (BMI < 23 kg/m2) and 234 (87.0%) patients as the overweight/obesity group (BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2). Compared with the overweight/obesity group, the underweight/normal BMI group was older, included a higher proportion of females, and had lower rates of current alcohol consumption and hypertension. In addition, this group showed lower levels of uric acid, TC, LDL-C, triglycerides, and ALT but higher ESR levels (Table 1). Additionally, the comparison of patient groups based on the WHO BMI classification with a cutoff of 25 kg/m2 was presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of the underweight/normal BMI and overweight/obese groups.

Correlation analyses showed that, in the underweight/normal BMI group, only the female sex was significantly correlated with BMI (correlation coefficient: −0.337, 95% CI −0.603 to −0.004, p = 0.048). In contrast, in the overweight/obesity group, age (correlation coefficient: −0.287, 95% CI −0.400 to −0.165, p < 0.001), hypertension (correlation coefficient: 0.201, 95% CI 0.075 to 0.321, p = 0.002), ESR (correlation coefficient: −0.134, 95% CI −0.258 to −0.006, p = 0.040), and ALT (correlation coefficient: 0.314, 95% CI 0.194 to 0.425, p < 0.001) showed significant associations with BMI (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation between BMI and patient characteristics.

3.2. Predictive Factors for Underweight/Normal BMI in Patients with Gout and Subgroup Analyses

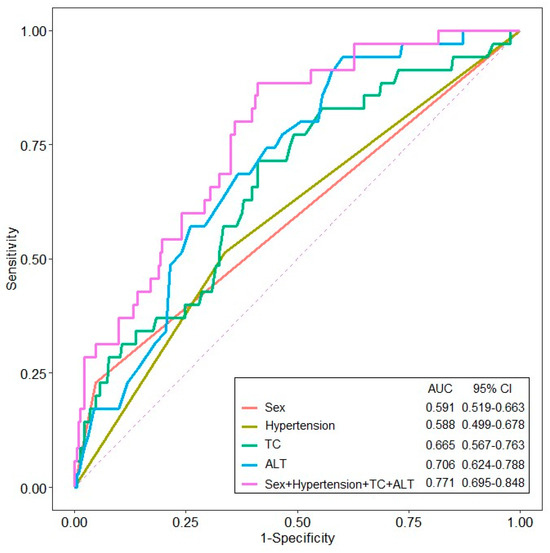

Logistic regression analysis identified female sex (OR = 3.831, 95% CI 1.254–11.705, p = 0.018), hypertension (OR = 0.367, 95% CI 0.166–0.809, p = 0.013), TC (OR = 0.990, 95% CI 0.982–0.999, p = 0.031), and ALT (OR = 0.967, 95% CI 0.941–0.995, p = 0.019) as factors associated with underweight/normal BMI (Table 3). The logistic regression analysis based on the WHO BMI classification of 25 kg/m2 was presented in Supplementary Table S2. ROC analysis of these factors revealed AUC values of 0.591 for females, 0.588 for those with a history of hypertension, 0.665 for TC, and 0.706 for ALT. A combined model of all four factors achieved an AUC of 0.771 (95% CI, 0.695–0.848) for distinguishing underweight/normal BMI from overweight/obese patients with gout (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of patient characteristics of underweight/normal BMI gout.

Figure 1.

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of variables for predicting underweight/normal BMI patients with gout (ALT, alanine aminotransferase; TC, total cholesterol).

Subgroup analyses were performed on a subset of patients with new-onset gout (n = 81) and male patients (n = 250). For new-onset patients, female sex (OR = 12.345, 95% CI 1.856–82.120, p = 0.009) and TC (OR = 0.964, 95% CI 0.942–0.987, p = 0.002) were predictive of underweight/normal BMI gout (Supplementary Table S3). Among male patients, LDL-C (OR = 0.989, 95% CI 0.978–0.999, p = 0.039) and ALT (OR = 0.966, 95% CI 0.938–0.995, p = 0.022) were associated with underweight/normal BMI in patients with gout (Supplementary Table S4).

3.3. Gout Flares After One-Year Follow-Up by BMI Status

At the one-year follow-up, no statistically significant differences were observed in gout flares (p = 0.755) or in flares requiring hospitalization (p = 0.686) between the underweight/normal BMI and overweight/obese patient groups (Supplementary Table S5).

4. Discussion

The global increase in the occurrence of gout and obesity, along with their close association, has resulted in these conditions becoming significant societal concerns. Notably, obesity and metabolic disorders are especially prevalent among patients with gout [19,20,21]. Nevertheless, the clinical characteristics of patients with non-obese gout remain poorly understood, and evaluating the clinical features of this disease subset could enhance the identification of these patients. In this study, comparison of baseline patient characteristics revealed that underweight/normal BMI patients were more likely to be older, included a higher proportion of females, and had lower rates of hypertension and alcohol consumption compared to overweight/obese patients. In addition, the underweight/normal BMI group had lower levels of uric acid, TC, LDL-C, triglycerides, and ALT, indicating distinct clinical characteristics. In the logistic regression analysis, female sex and the presence of hypertension, TC, and ALT were significant predictors of underweight/normal BMI. When these factors were integrated into the ROC analysis, the model achieved an AUC of 0.771, indicating fair diagnostic accuracy for underweight/normal BMI gout.

Obesity is traditionally considered a major risk factor for gout by increasing adipose tissue, which elevates uric acid levels in the circulation via enhanced production and diminished renal excretion [11,22]. Notably, our study revealed that 13.0% of patients were classified as underweight or normal BMI and showed distinct clinical characteristics compared with the overweight/obese group. These findings are in agreement with previous population-based studies reporting that gout prevalence was approximately 1–2% in normal-weight individuals and 4–7% in those with obesity [23]. These patients, who were more frequently elderly and female, showed lower prevalence of hypertension and reduced values of laboratory tests related to dyslipidemia, which are components of the metabolic syndrome. Specifically, the underweight/normal-BMI group showed lower lipid profiles and serum uric acid levels than overweight/obese patients (Table 1). In line with our findings, previous studies have reported that a lower BMI is associated with fewer metabolic abnormalities [24,25]. Furthermore, multivariate logistic regression analysis identified female sex, absence of hypertension, and lower TC and ALT levels as factors increasing the risk of being classified as underweight/normal BMI patient with gout. These findings emphasize that gout can also affect patients with lower BMI, even in the absence of traditional metabolic risk factors, and clinical vigilance by the attending physician is imperative for optimal diagnosis.

Our data revealed a significant correlation between sex and BMI in the underweight/normal-BMI group, a relationship not observed in other variables. In contrast, we observed that hypertension, dyslipidemia, uric acid, and ALT were positively correlated in the overweight/obese subgroup, which is consistent with typical gout-related characteristics. The inverse association between sex and BMI in the underweight/normal BMI subgroup could partly be attributed to the higher proportion of females, who generally have lower BMI than males [26]. However, the relatively small percentage of females (22.9%) in the underweight/normal BMI group suggests that additional factors likely contributed to the observed group differences. Indeed, in logistic regression analysis, hypertension, TC, and ALT decreased the risk of underweight/normal BMI gout. Similarly, in patients with new-onset disease, female sex and TC level were statistically significant predictors in logistic analysis. In an exclusive analysis of male patients, LDL-C and ALT levels were found to have an inverse relationship with underweight or normal BMI. Collectively, these findings suggest that patients with underweight/normal BMI with gout represent a distinct subgroup compared to patients with overweight/obesity, which likely reflects a different phenotype rather than a direct protective effect of these parameters on gout risk. From a pathophysiological aspect, lower TC and ALT in this subgroup may indicate a distinct metabolic condition characterized by reduced visceral adiposity and hepatic steatosis, in contrast to the typical phenotype of obesity-related “metabolic gout” [27,28]. Furthermore, older age, chronic inflammatory or catabolic states can be associated with both reduced serum cholesterol and impaired renal urate excretion, thereby predisposing to gout despite favorable lipid profiles [29,30]. In this context, low TC is more likely to indicate an alternative disease pathway than to act as a protective factor against gout itself. Although insulin resistance is a well-known risk factor for gout, our cross-sectional design could not directly assess this relationship. Nevertheless, the disparate metabolic pattern observed in our patients with underweight/normal BMI implies that, even in the absence of obesity or classical features of metabolic syndrome, subclinical insulin resistance or other non-obesity-related metabolic abnormalities may contribute to gout development [31,32]. Therefore, our findings indicate that gout should not be regarded only as a disease of patients with obesity and metabolic syndrome. Furthermore, genetic predisposition is also likely to contribute to gout development in patients with underweight/normal BMI. Genetic studies have identified urate transporter variants in genes such as ABCG2 and SLC2A9 as major determinants of serum urate levels and gout risk, with several risk alleles reported to be more prevalent in East Asian populations [33,34]. In this patient group, such genetic susceptibility may interact with modest environmental exposures to precipitate gout, while genetic testing for these variants is not possible in routine gout care. Accordingly, although our dataset did not include genetic information, future studies that integrate clinical, metabolic, and genomic data are warranted to clarify these gene–environment interactions.

In our cohort, underweight/normal-BMI patients with gout were more frequently female with lower ALT, TC, and hypertension rates than overweight/obese patients; however, these patients still developed gout. Thus, it is recommended for the clinicians be precautious to exclude gout solely based on BMI or the lack of typical metabolic syndrome features and diagnoses should be made with care in normal-BMI patients, particularly women, who present with compatible joint symptoms or hyperuricemia. Basic screening for blood pressure, lipid profile, and liver and renal function remains crucial in all patients with gout; however, in non-obese individuals, greater attention should be directed towards non–obesity-related factors such as renal urate handling, concomitant medications, and alcohol use. In addition, our study identified hypertension, lipid profile, and the liver enzyme ALT, along with female sex, as distinguishing factors between underweight/normal BMI and overweight/obese patients with gout. Intriguingly, ROC analysis using a model that included female sex, hypertension, TC, and ALT yielded an AUC of 0.771. This integrated model demonstrated higher diagnostic accuracy than individual variables alone, supporting its clinical utility in differentiating between underweight/normal BMI and overweight/obesity patients with gout [35]. Nevertheless, due to the modest performance of this model, further research is needed to precisely understand the diverse clinical aspects of gout.

Notably, some limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings. First, as a retrospective cross-sectional study, selection bias may have occurred, which could have influenced our results. Second, we did not include other relevant factors, such as genetic predisposition, intensity and frequency of exercise, or dietary intake. Third, BMI classification in this study was based on the WHO Asia–Pacific criteria, which divide patients into underweight/normal-BMI and overweight/obesity groups using a cutoff of 23 kg/m2. This threshold has been widely used in epidemiologic studies and clinical guidelines in Korea, as it better reflects cardiometabolic risk patterns in Asian populations. However, it differs from the global WHO classification. Because our study population consisted solely of Korean patients from a single medical center, the generalizability of our findings to other ethnic or regional populations may be limited. Fourth, because of the cross-sectional design, detailed information on gout history, including flare frequency, duration, and symptom severity, was unavailable. In addition, the gout phase at the time of blood sampling could not be standardized, as not all laboratory data were obtained at the identical phase of disease. Therefore, transient fluctuations in serum uric acid levels during acute attacks could not be completely excluded. Lastly, only 35 patients in our cohort had gout without obesity, and only 19 of them were female, representing a relatively small subgroup. Because of this limited sample size, the results of the multivariable analysis should be interpreted with caution, and some clinically important variables, such as serum uric acid, were not retained in the final model. Therefore, these findings should be considered exploratory, and further multicenter or nationwide cohort studies including a larger number of non-obese and female patients with gout are needed to validate and refine our understanding of this subgroup.

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that underweight/normal-BMI patients with gout exhibit distinct clinical characteristics compared to overweight/obese patients. Female sex, hypertension, TC, and ALT levels were helpful in identifying this subgroup. Our findings suggest that the integration of these features may facilitate the recognition of a unique patient subpopulation with gout, contributing to a more nuanced understanding of the disease.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/life15121876/s1, Table S1: Patient characteristics between the underweight/normal BMI and overweight/obesity groups by the standard WHO classification; Table S2: Logistic regression analysis of patient characteristics of underweight/normal BMI gout by the standard WHO classification; Table S3: Logistic regression analysis of predictive variables for gout in underweight/normal BMI patients with new-onset disease (n = 81); Table S4: Logistic regression analysis of the predictive variables for underweight/normal BMI gout in male patients (n = 250); Table S5: Disease outcomes during 1-year follow-up (n = 98).

Author Contributions

S.S.A.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing; J.A.K.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing—original draft; S.R.: Data curation, Validation, Writing—original draft; Y.S.: Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft; K.Y.C.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft; S.H.C.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft; K.B.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the research fund of Hanyang University. (HY-202400000003302).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yongin Severance Hospital (IRB number: 9-2024-0006; Approval date: 14 March 2024). All research procedures were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BMI | Body mass index |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| WBC | White blood cell |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| ESR | Erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| BUN | Blood urea nitrogen |

| TC | Total cholesterol |

| LDL-C | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HDL-C | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HbA1c | Glycated hemoglobin |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| MSU | Monosodium urate |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

References

- Pascual, E.; Addadi, L.; Andres, M.; Sivera, F. Mechanisms of crystal formation in gout-a structural approach. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2015, 11, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, J.S.; Vina, E.R.; Munk, P.L.; Klauser, A.S.; Elifritz, J.M.; Taljanovic, M.S. Gouty Arthropathy: Review of Clinical Manifestations and Treatment, with Emphasis on Imaging. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 11, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalbeth, N.; Merriman, T.R.; Stamp, L.K. Gout. Lancet 2016, 388, 2039–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecherstorfer, C.; Simon, D.; Unbehend, S.; Ellmann, H.; Englbrecht, M.; Hartmann, F.; Figueiredo, C.; Hueber, A.; Haschka, J.; Kocijan, R.; et al. A Detailed Analysis of the Association between Urate Deposition and Erosions and Osteophytes in Gout. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020, 2, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.C.; Lin, H.Y.; Chou, P. Community based epidemiological study on hyperuricemia and gout in Kin-Hu, Kinmen. J. Rheumatol. 2000, 27, 1045–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Bursill, D.; Taylor, W.J.; Terkeltaub, R.; Dalbeth, N. The nomenclature of the basic disease elements of gout: A content analysis of contemporary medical journals. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2018, 48, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Other Musculoskeletal Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of other musculoskeletal disorders, 1990-2020, and projections to 2050: A systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023, 5, e670–e682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, T.I.A.; Martinez, A.R.; Jorgensen, T.S.H. Epidemiology of Obesity. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2022, 274, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, E.A.; Khavjou, O.A.; Thompson, H.; Trogdon, J.G.; Pan, L.; Sherry, B.; Dietz, W. Obesity and severe obesity forecasts through 2030. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 42, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannou, S.A.; Haslam, D.E.; McKeown, N.M.; Herman, M.A. Fructose metabolism and metabolic disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, F.; Yamashita, S.; Nakamura, T.; Nishida, M.; Nozaki, S.; Funahashi, T.; Matsuzawa, Y. Effect of visceral fat accumulation on uric acid metabolism in male obese subjects: Visceral fat obesity is linked more closely to overproduction of uric acid than subcutaneous fat obesity. Metabolism 1998, 47, 929–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panlu, K.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, L.; Ge, L.; Wen, C.; Lv, H. Associations between obesity and hyperuricemia combing mendelian randomization with network pharmacology. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, T.J.; Dalbeth, N.; Stahl, E.A.; Merriman, T.R. An update on the genetics of hyperuricaemia and gout. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2018, 14, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigham, M.D.; Milgroom, A.; Lenco, M.O.; Wang, Z.; Kent, J.D.; LaMoreaux, B.; Johnson, R.J.; Mandell, B.F.; Hadker, N.; Sanchez, H.; et al. Immunosuppressant Use and Gout in the Prevalent Solid Organ Transplantation Population. Prog. Transpl. 2020, 30, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalbeth, N.; Choi, H.K.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Khanna, P.P.; Matsuo, H.; Perez-Ruiz, F.; Stamp, L.K. Gout. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, S.L.; Robinson, H.; Masi, A.T.; Decker, J.L.; McCarty, D.J.; Yu, T.F. Preliminary criteria for the classification of the acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum. 1977, 20, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.C.B.; WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004, 363, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Son, H.; Ryu, O.H. Management Status of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors for Dyslipidemia among Korean Adults. Yonsei Med. J. 2017, 58, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Tsumura, K.; Endo, G.; Fujii, S.; Okada, K. Serum uric acid and the risk for hypertension and Type 2 diabetes in Japanese men: The Osaka Health Survey. J. Hypertens. 2001, 19, 1209–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copur, S.; Demiray, A.; Kanbay, M. Uric acid in metabolic syndrome: Does uric acid have a definitive role? Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 103, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thottam, G.E.; Krasnokutsky, S.; Pillinger, M.H. Gout and Metabolic Syndrome: A Tangled Web. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2017, 19, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, S.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Tokunaga, K.; Fujioka, S.; Tarui, S. Studies on the impaired metabolism of uric acid in obese subjects: Marked reduction of renal urate excretion and its improvement by a low-calorie diet. Int. J. Obes. 1986, 10, 255–264. [Google Scholar]

- Juraschek, S.P.; Miller, E.R., 3rd; Gelber, A.C. Body mass index, obesity, and prevalent gout in the United States in 1988–1994 and 2007–2010. Arthritis Care Res. 2013, 65, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meigs, J.B.; Wilson, P.W.; Fox, C.S.; Vasan, R.S.; Nathan, D.M.; Sullivan, L.M.; D’Agostino, R.B. Body mass index, metabolic syndrome, and risk of type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 2906–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobo, O.; Leiba, R.; Avizohar, O.; Karban, A. Normal body mass index (BMI) can rule out metabolic syndrome: An Israeli cohort study. Medicine 2019, 98, e14712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, S.; Nakamura, S. Why are women slimmer than men in developed countries? Econ. Hum. Biol. 2018, 30, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Jiang, X.; Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Wu, Y.; Gao, P.; Hua, F. Visceral adipose accumulation increased the risk of hyperuricemia among middle-aged and elderly adults: A population-based study. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C. Hyperuricemia and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: From bedside to bench and back. Hepatol. Int. 2016, 10, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orkaby, A.R. The Highs and Lows of Cholesterol: A Paradox of Healthy Aging? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 236–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroevers, J.L.; Richard, E.; Hoevenaar-Blom, M.P.; van den Born, B.-J.H.; van Gool, W.A.; Moll van Charante, E.P.; van Dalen, J.W. Adverse Lipid Profiles Are Associated with Lower Dementia Risk in Older People. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2024, 25, 105132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, N.; O’Connor, M.J.; Yokose, C.; Merriman, T.R.; Mount, D.B.; Leong, A.; Choi, H.K. Assessing the Causal Relationships Between Insulin Resistance and Hyperuricemia and Gout Using Bidirectional Mendelian Randomization. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021, 73, 2096–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, W.G.; Martins-Santos, M.E.; Chaves, V.E. Uric acid as a modulator of glucose and lipid metabolism. Biochimie 2015, 116, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatochi, M.; Kanai, M.; Nakayama, A.; Hishida, A.; Kawamura, Y.; Ichihara, S.; Akiyama, M.; Ikezaki, H.; Furusyo, N.; Shimizu, S.; et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies multiple novel loci associated with serum uric acid levels in Japanese individuals. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.J.; Chen, I.C.; Lin, H.J.; Lin, Y.C.; Chang, J.C.; Chen, Y.M.; Hsiao, T.H.; Chen, P.C.; Lin, C.H. Association of ABCG2 rs2231142 Allele and BMI With Hyperuricemia in an East Asian Population. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 709887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çorbacıoğlu, Ş.K.; Aksel, G. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis in diagnostic accuracy studies: A guide to interpreting the area under the curve value. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2023, 23, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).