Modulation of Oxidative and ER Stress Pathways by the ADAM17 Inhibitor GW280264X in LPS-Induced Acute Liver Injury

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals, Antibodies, and Kits

2.2. Experimental Design, Animal Treatment, and Tissue Collection

- (1)

- Control: 0.9% NaCl, intraperitoneal (i.p.).

- (2)

- LPS: a single i.p. dose of lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 10 mg/kg, Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.9% NaCl.

- (3)

- LPS + GW280264X: Mice received LPS (10 mg/kg, i.p.), followed by GW280264X (500 µg/kg, i.p.) prepared in distilled water containing 10% DMSO. Each mouse (≈20 g) received 100 µL of solution (corresponding to ≈10 µg GW280264X) administered at the 1st and 3rd hours after LPS injection. The 10% DMSO formulation ensured complete solubility of GW280264X. No precipitation or visible injection-site irritation was observed with this vehicle [32].

- (4)

- LPS + DMSO: LPS (10 mg/kg, i.p.) plus an equivalent volume of vehicle (10% DMSO in distilled water, i.p.) at the 1st and 3rd hours.

2.3. Tissue Homogenization and Protein Extraction

2.4. Enzymatic Colorimetric Measurements

2.5. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISA)

2.6. Western Blotting

2.7. Histopathology (H&E)

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

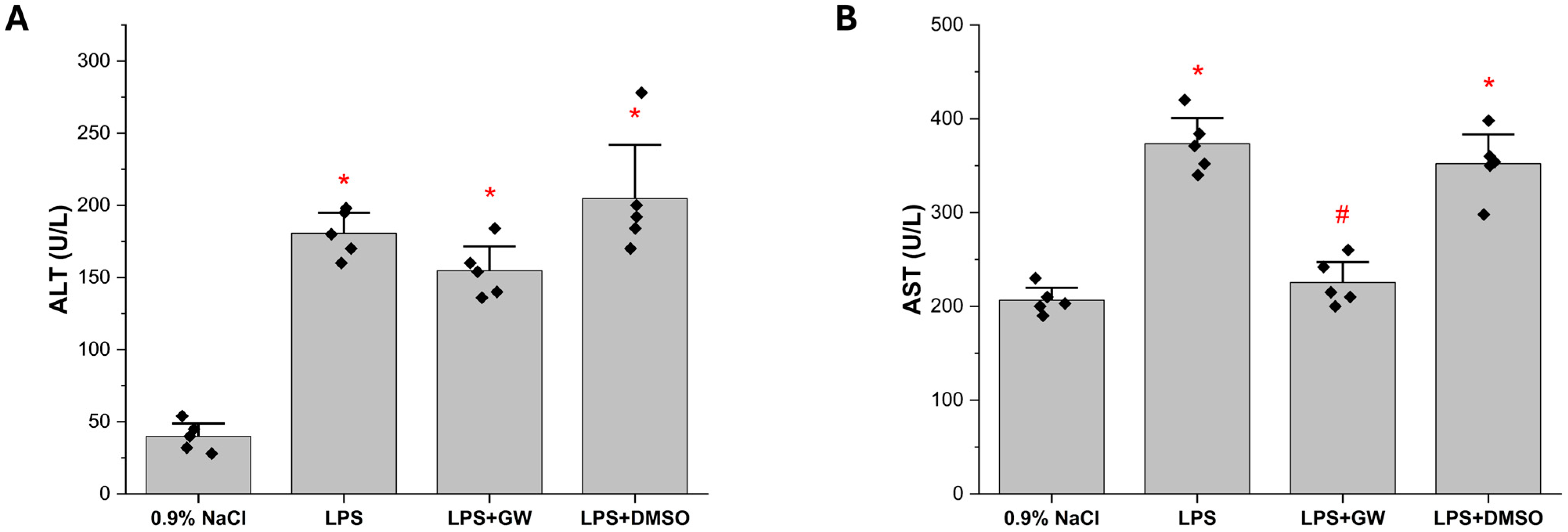

3.1. GW280264X Mitigates LPS-Induced Elevations of Serum AST Levels

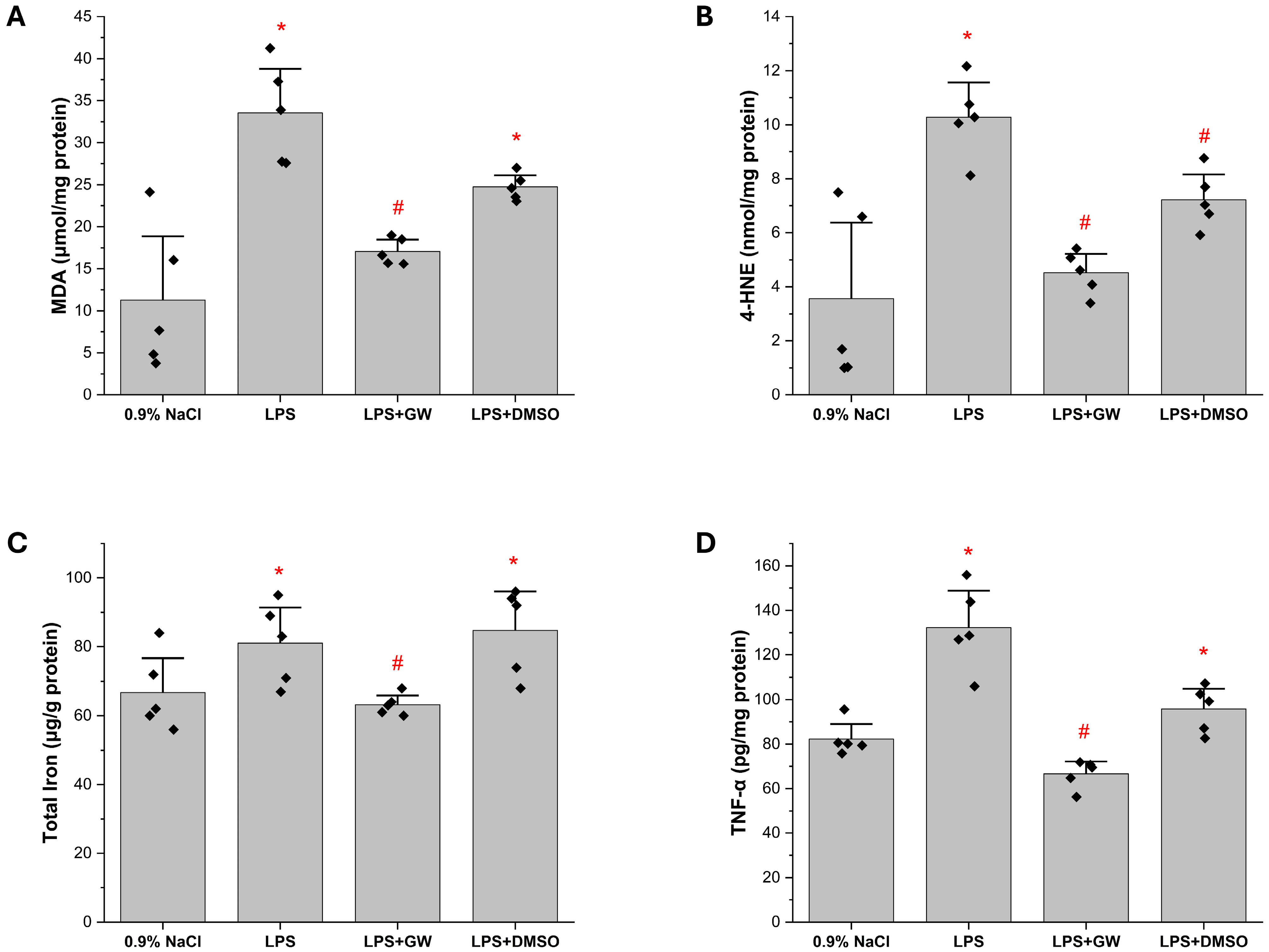

3.2. Inflammatory and Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Liver Tissue

3.3. Redox Regulatory Markers: Keap1, Nrf2, and GSH Levels in Liver Tissue

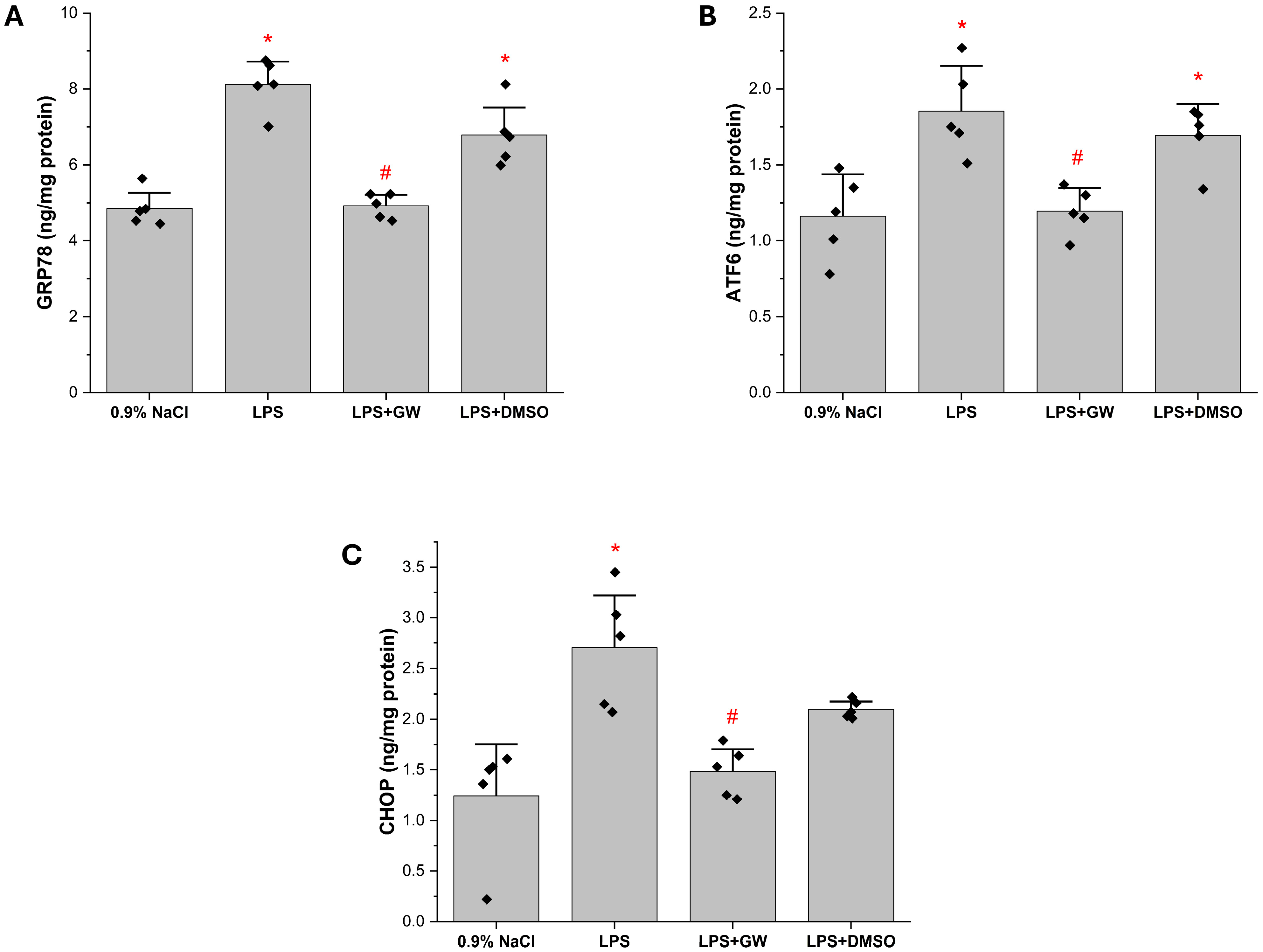

3.4. ER Stress-Associated Protein Levels in Liver Tissue

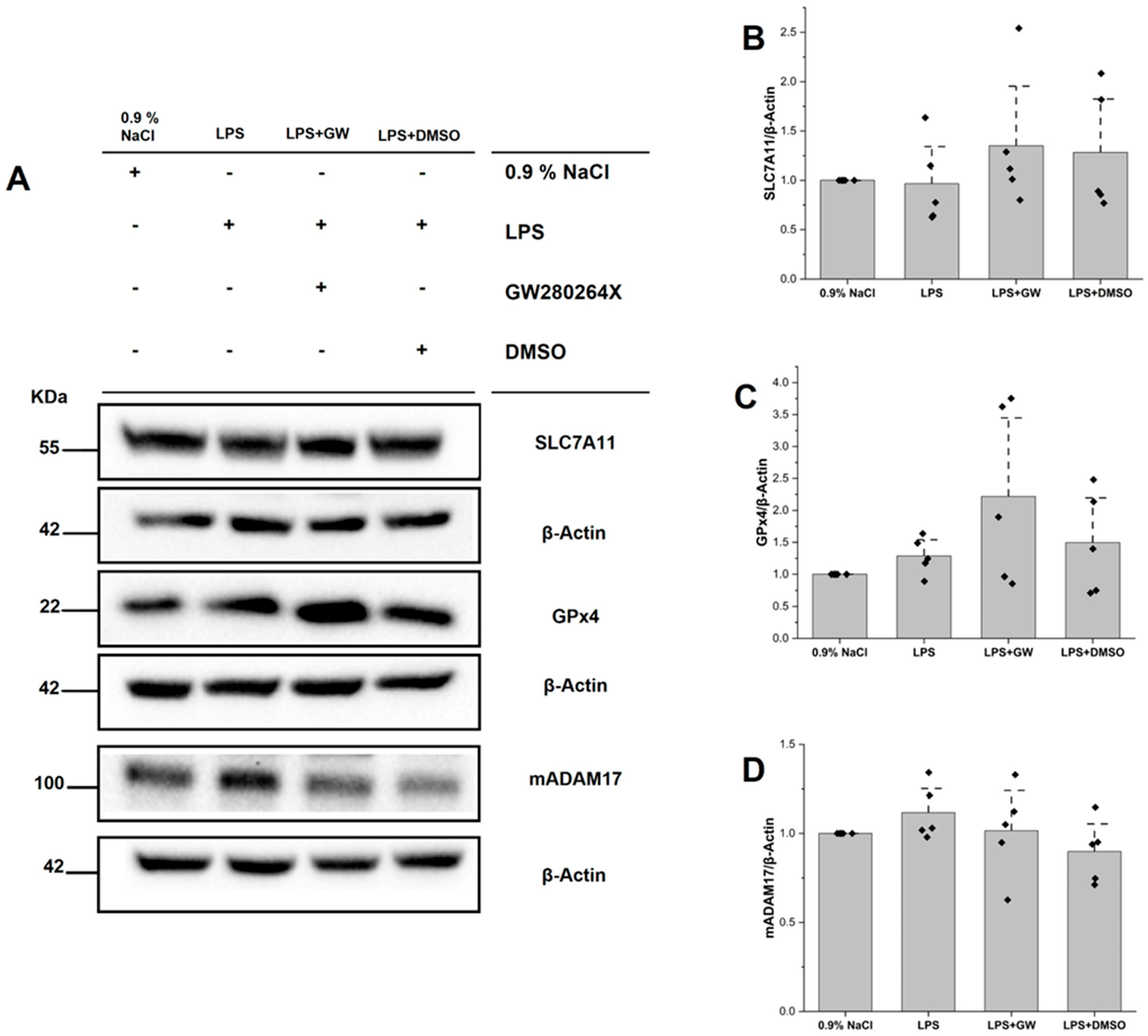

3.5. Protein Expression of SLC7A11, GPX4, and ADAM17

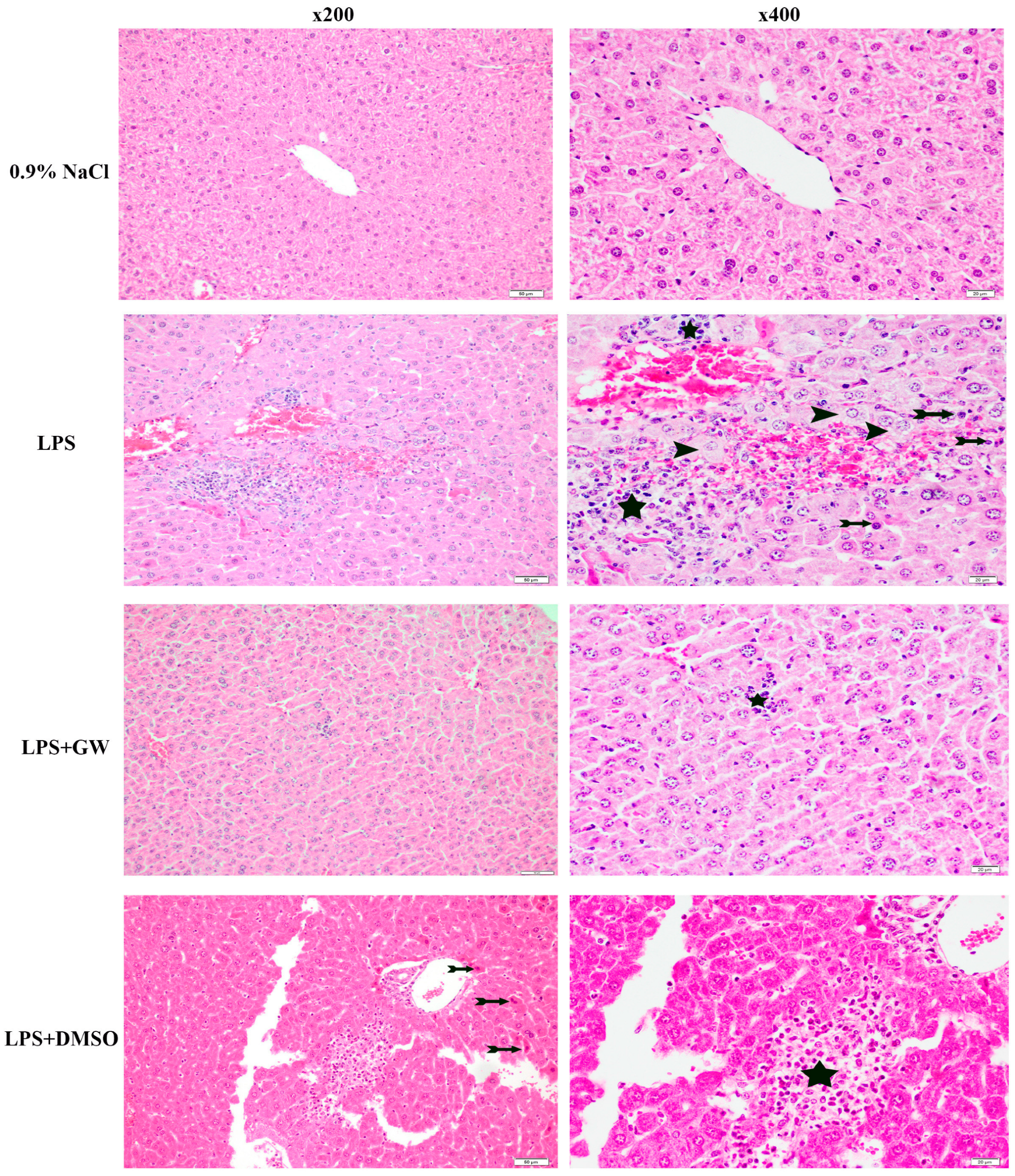

3.6. Liver Injury Assessment by Histology

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stravitz, R.T.; Lee, W.M. Acute liver failure. Lancet 2019, 394, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Wang, Y.Y.; Chen, C.; Guan, J.; Zhu, H.H.; Chen, Z. The immunological roles in acute-on-chronic liver failure: An update. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. HBPD INT 2019, 18, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowa, J.P.; Gerken, G.; Canbay, A. Acute Liver Failure—It’s Just a Matter of Cell Death. Dig. Dis. 2016, 34, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, R. The Pathogenesis of ACLF: The Inflammatory Response and Immune Function. Semin. Liver Dis. 2016, 36, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Yan, H.; Zhao, H.; Sun, W.; Yang, Q.; Sheng, J.; Shi, Y. Characteristics of systemic inflammation in hepatitis B-precipitated ACLF: Differentiate it from No-ACLF. Liver Int. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Liver 2018, 38, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensley, M.K.; Deng, J.C. Acute on Chronic Liver Failure and Immune Dysfunction: A Mimic of Sepsis. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 39, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Mateos, R.; Alvarez-Mon, M.; Albillos, A. Dysfunctional Immune Response in Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure: It Takes Two to Tango. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asrani, S.K.; O’Leary, J.G. Acute-on-chronic liver failure. Clin. Liver Dis. 2014, 18, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhi, H.; Guicciardi, M.E.; Gores, G.J. Hepatocyte death: A clear and present danger. Physiol. Rev. 2010, 90, 1165–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Xiong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, H.; Ren, Y.; Tang, X.; Song, J.; Wang, C. IL-22 ameliorates LPS-induced acute liver injury by autophagy activation through ATF4-ATG7 signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.W.; Zhao, B.W.; Li, H.F.; Zhang, G.X. Overview of ferroptosis and pyroptosis in acute liver failure. World J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 3856–3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, S.J.; Stockwell, B.R. The role of iron and reactive oxygen species in cell death. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A.; Muñoz, M.F.; Argüelles, S. Lipid peroxidation: Production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 360438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Margison, K.; Pratt, D.A. The Potency of Diarylamine Radical-Trapping Antioxidants as Inhibitors of Ferroptosis Underscores the Role of Autoxidation in the Mechanism of Cell Death. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017, 12, 2538–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockwell, B.R.; Friedmann Angeli, J.P.; Bayir, H.; Bush, A.I.; Conrad, M.; Dixon, S.J.; Fulda, S.; Gascón, S.; Hatzios, S.K.; Kagan, V.E.; et al. Ferroptosis: A Regulated Cell Death Nexus Linking Metabolism, Redox Biology, and Disease. Cell 2017, 171, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, N.; Karasawa, T.; Kimura, H.; Watanabe, S.; Komada, T.; Kamata, R.; Sampilvanjil, A.; Ito, J.; Nakagawa, K.; Kuwata, H.; et al. Ferroptosis driven by radical oxidation of n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids mediates acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zunke, F.; Rose-John, S. The shedding protease ADAM17: Physiology and pathophysiology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2017, 1864 Pt B, 2059–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, S.F.; Lemberg, M.K.; Fluhrer, R. Proteolytic ectodomain shedding of membrane proteins in mammals-hardware, concepts, and recent developments. EMBO J. 2018, 37, e99456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharfenberg, F.; Helbig, A.; Sammel, M.; Benzel, J.; Schlomann, U.; Peters, F.; Wichert, R.; Bettendorff, M.; Schmidt-Arras, D.; Rose-John, S.; et al. Degradome of soluble ADAM10 and ADAM17 metalloproteases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2020, 77, 331–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, M.L.; Minond, D. Recent Advances in ADAM17 Research: A Promising Target for Cancer and Inflammation. Mediat. Inflamm. 2017, 2017, 9673537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calligaris, M.; Cuffaro, D.; Bonelli, S.; Spanò, D.P.; Rossello, A.; Nuti, E.; Scilabra, S.D. Strategies to Target ADAM17 in Disease: From its Discovery to the iRhom Revolution. Molecules 2021, 26, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, R.A.; Rauch, C.T.; Kozlosky, C.J.; Peschon, J.J.; Slack, J.L.; Wolfson, M.F.; Castner, B.J.; Stocking, K.L.; Reddy, P.; Srinivasan, S.; et al. A metalloproteinase disintegrin that releases tumour-necrosis factor-alpha from cells. Nature 1997, 385, 729–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedger, L.M.; McDermott, M.F. TNF and TNF-receptors: From mediators of cell death and inflammation to therapeutic giants-past, present and future. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2014, 25, 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, N.; Meyer, D.; Mauermann, A.; von der Heyde, J.; Wolf, J.; Schwarz, J.; Knittler, K.; Murphy, G.; Michalek, M.; Garbers, C.; et al. Shedding of Endogenous Interleukin-6 Receptor (IL-6R) Is Governed by A Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase (ADAM) Proteases while a Full-length IL-6R Isoform Localizes to Circulating Microvesicles. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 26059–26071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garton, K.J.; Gough, P.J.; Philalay, J.; Wille, P.T.; Blobel, C.P.; Whitehead, R.H.; Dempsey, P.J.; Raines, E.W. Stimulated shedding of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) is mediated by tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme (ADAM 17). J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 37459–37464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, K.; Kobayashi, F.; Ikegawa, R.; Koyama, M.; Shintani, N.; Yoshida, T.; Nakamura, N.; Kondo, T. Metalloproteinase inhibitor prevents hepatic injury in endotoxemic mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998, 341, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, A.; Hundhausen, C.; Lambert, M.H.; Broadway, N.; Andrews, R.C.; Bickett, D.M.; Leesnitzer, M.A.; Becherer, J.D. Metalloproteinase inhibitors for the disintegrin-like metalloproteinases ADAM10 and ADAM17 that differentially block constitutive and phorbol ester-inducible shedding of cell surface molecules. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2005, 8, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbodakova, O.; Chalupsky, K.; Kanchev, I.; Zbodakova, L.; Koudelka, S.; Krivohlava, R.; Sedlacek, R. ADAM10 and ADAM17 regulate EGFR, c-Met, and TNFR1 signaling in liver regeneration and fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilley, E.; Stanford, S.C.; Kendall, D.E.; Alexander, S.P.H.; Cirino, G.; Docherty, J.R.; George, C.H.; Insel, P.A.; Izzo, A.A.; Ji, Y.; et al. ARRIVE 2.0 and the British Journal of Pharmacology: Updated guidance for 2020. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 3611–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, J.C.; Lilley, E. Implementing guidelines on reporting research using animals (ARRIVE etc.): New requirements for publication in BJP. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 172, 3189–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigit, E.; Deger, O.; Korkmaz, K.; Huner Yigit, M.; Uydu, H.A.; Mercantepe, T.; Demir, S. Propolis reduces inflammation and dyslipidemia caused by a high-cholesterol diet in mice by lowering ADAM10/17 activities. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, W.; Hao, Y.; Xie, H.; Ni, Y.; Zhao, R. Hepatic Inflammatory Response to Exogenous LPS Challenge is Exacerbated in Broilers with Fatty Liver Disease. Animals 2020, 10, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, X.; Han, L.; Ye, F.; Liu, M.; Fan, W.; Zhang, K.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shi, L.; et al. Pterostilbene alleviates polymicrobial sepsis-induced liver injury: Possible role of SIRT1 signaling. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 49, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkoç, M.; Patan, H.; Yaman, S.Ö.; Türedi, S.; Kerimoğlu, G.; Kural, B.V.; Örem, A. l-theanine alleviates liver and kidney dysfunction in septic rats induced by cecal ligation and puncture. Life Sci. 2020, 249, 117502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, E.; Ilgaz, Y.; Gurgor, P.N.; Oztas, Y.; Topal, T.; Oztas, E. Rutin ameliorates methotrexate induced hepatic injury in rats. Acta Cir. Bras. 2015, 30, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güvendi, G.F.; Eroğlu, H.A.; Makav, M.; Güvendi, B.; Adalı, Y. Selenium or ozone: Effects on liver injury caused by experimental iron overload. Life Sci. 2020, 262, 118558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIlwain, D.R.; Lang, P.A.; Maretzky, T.; Hamada, K.; Ohishi, K.; Maney, S.K.; Berger, T.; Murthy, A.; Duncan, G.; Xu, H.C.; et al. iRhom2 regulation of TACE controls TNF-mediated protection against Listeria and responses to LPS. Science 2012, 335, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Salihi, M.; Bornikoel, A.; Zhuang, Y.; Stachura, P.; Scheller, J.; Lang, K.S.; Lang, P.A. The role of ADAM17 during liver damage. Biol. Chem. 2021, 402, 1115–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, Y.; Cai, E.; Zhu, H.; Li, P.; Liu, J. Protective Effects of Sesquiterpenoids from the Root of Panax ginseng on Fulminant Liver Injury Induced by Lipopolysaccharide/d-Galactosamine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 7758–7763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Si, W.; Zeng, J.; Huang, L.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Liu, J.; Zhu, M.; Kuang, W. Niujiaodihuang Detoxify Decoction inhibits ferroptosis by enhancing glutathione synthesis in acute liver failure models. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 279, 114305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Y.; Yu, J.; Shi, L.; Zhang, P.; Yin, Y.; Li, R.; Tao, K. Maresin1 Protect Against Ferroptosis-Induced Liver Injury Through ROS Inhibition and Nrf2/HO-1/GPX4 Activation. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 865689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Luo, Y.L.; Xiang, Y.; Bai, X.Y.; Qiang, R.R.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.L.; Liu, X.L. Ferroptosis inhibitors: Past, present and future. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1407335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atak, M.; Yigit, E.; Huner Yigit, M.; Topal Suzan, Z.; Yilmaz Kutlu, E.; Karabulut, S. Synthetic and non-synthetic inhibition of ADAM10 and ADAM17 reduces inflammation and oxidative stress in LPS-induced acute kidney injury in male and female mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 983, 176964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yiğit, E.; Yiğit, M.H.; Atak, M.; Topal Suzan, Z.; Karabulut, S.; Yıldız, G.; Değer, O. Kaempferol reduces pyroptosis in acute lung injury by decreasing ADAM10 activity through the NLRP3/GSDMD pathway. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinon, F.; Chen, X.; Lee, A.H.; Glimcher, L.H. TLR activation of the transcription factor XBP1 regulates innate immune responses in macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, C.; Zhang, H.F.; Wang, Y.J.; Chen, Z.T.; Deng, B.Q.; Qiu, Q.; Chen, S.X.; Wu, M.X.; Chen, Y.X.; Wang, J.F. The Downregulation of ADAM17 Exerts Protective Effects against Cardiac Fibrosis by Regulating Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Mitophagy. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 5572088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamesch, K.; Borkham-Kamphorst, E.; Strnad, P.; Weiskirchen, R. Lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory liver injury in mice. Lab. Anim. 2015, 49 (Suppl. S1), 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Ouyang, Z.; Tan, X.; Liu, X.; Bai, J.; Wang, H.; Huang, L. Protective Effect of the Naringin–Chitooligosaccharide Complex on Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Systematic Inflammatory Response Syndrome Model in Mice. Foods 2024, 13, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakadate, K.; Saitoh, H.; Sakaguchi, M.; Miruno, F.; Muramatsu, N.; Ito, N.; Tadokoro, K.; Kawakami, K. Advances in Understanding Lipopolysaccharide-Mediated Hepatitis: Mechanisms and Pathological Features. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.; Ielapi, N.; Minici, R.; Bevacqua, E.; Ciranni, S.; Cristodoro, L.; Torcia, G.; Di Taranto, M.D.; Bracale, U.M.; Andreucci, M.; et al. Metalloproteinases between History, Health, Disease, and the Complex Dimension of Social Determinants of Health. J. Vasc. Dis. 2023, 2, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, A.; Bronk, S.F.; Cazanave, S.; Werneburg, N.W.; Mott, J.L.; Contreras, P.C.; Gores, G.J. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor, CTS-1027, attenuates liver injury and fibrosis in the bile duct-ligated mouse. Hepatol. Res. Off. J. Jpn. Soc. Hepatol. 2009, 39, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Meijer, V.E.; Sverdlov, D.Y.; Popov, Y.; Le, H.D.; Meisel, J.A.; Nose, V.; Puder, M. Broad-spectrum MMP inhibition reduces inflammation but increases fibrosis in chronic liver injury. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters Median (Min–Max) | 0.9% NaCl | LPS | LPS + GW280264X | LPS + DMSO | Kruskal-Wallis, p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatocyte disorganization | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 1 |

| Edema | 1 (1–2) | 2 (2–3) * | 2 (2–2) | 1 (1–1) | 0.040173 |

| Congestion | 1 (1–2) | 2 (2–2) | 2 (2–2) | 1 (1–2) | 0.138639 |

| Hemorrhage | 1 (0–1) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–1) | 0.356239 |

| Sinusoidal dilatation | 1 (1–1) | 2 (2–3) * | 2 (2–2) * | 1 (1–1) | 0.015104 |

| Portal inflammation | 0 (0–0) | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–1) | 0.299781 |

| Lobular inflammation | 1 (1–1) | 3 (2–3) * | 1 (1–1) # | 2 (2–3) * | 0.019315 |

| Ballooning degeneration | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | 1 |

| Apoptosis | 1 (1–1) | 2 (2–2) * | 2 (1–2) | 1 (1–1) | 0.036971 |

| Necrosis | 0 (0–0) | 1 (0–1) | 0 (0–0) | 1 (0–1) | 0.138639 |

| Steatosis | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 1 |

| Fibrosis | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 1 |

| Total Score | 7 (7–8) | 16 (14–16) * | 12 (9–13) *,# | 9 (9–11) * | 0.01422 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huner Yigit, M.; Okcu, O.; Atak, M.; Karabulut, S.; Yıldız, G.; Yigit, E. Modulation of Oxidative and ER Stress Pathways by the ADAM17 Inhibitor GW280264X in LPS-Induced Acute Liver Injury. Life 2025, 15, 1877. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121877

Huner Yigit M, Okcu O, Atak M, Karabulut S, Yıldız G, Yigit E. Modulation of Oxidative and ER Stress Pathways by the ADAM17 Inhibitor GW280264X in LPS-Induced Acute Liver Injury. Life. 2025; 15(12):1877. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121877

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuner Yigit, Merve, Oguzhan Okcu, Mehtap Atak, Soner Karabulut, Gökhan Yıldız, and Ertugrul Yigit. 2025. "Modulation of Oxidative and ER Stress Pathways by the ADAM17 Inhibitor GW280264X in LPS-Induced Acute Liver Injury" Life 15, no. 12: 1877. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121877

APA StyleHuner Yigit, M., Okcu, O., Atak, M., Karabulut, S., Yıldız, G., & Yigit, E. (2025). Modulation of Oxidative and ER Stress Pathways by the ADAM17 Inhibitor GW280264X in LPS-Induced Acute Liver Injury. Life, 15(12), 1877. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121877