Abstract

Additive manufacturing via LCD vat photopolymerisation enables direct bonding of photopolymer to textile substrates, but optimal processing parameters remain unclear. A 3 × 3 factorial design investigated the effects of layer thickness (0.01, 0.025, 0.05 mm) and UV exposure time (40, 80, 120 s) on the single-lap shear strength of woven fabric-photopolymer joints (65% polyester/35% cotton) using a novel pause-and-bond methodology, following the EN ISO 4587:2003 standard. Five replicate specimens per condition yielded 45 samples for mechanical testing. All specimens (45/45) exhibited adherend-limited failure within the textile substrate rather than at the polymer-textile interface, yielding consistent shear strengths of 1.38 ± 0.04 MPa (range: 1.30–1.45 MPa). Two-way ANOVA revealed no significant parametric effects (p > 0.05), indicating that interfacial bond strength consistently exceeded textile cohesive strength across all parameter combinations. The minimum resource-efficient condition (0.01 mm/40 s) achieves equivalent performance to higher-parameter combinations, enabling substantial process optimisation for textile-integrated photopolymer sandwich structures while reducing material and processing time requirements.

1. Introduction

The increasing prevalence of additive manufacturing (AM) technologies has fundamentally changed modern manufacturing. These technologies are highly attractive as they enable rapid fabrication of complex geometries, reduce waste, and offer design flexibility [1,2,3]. Photopolymerisation methods warrant particular attention, as 3D printing techniques such as stereolithography (SLA), digital light processing (DLP), and LCD are increasingly used due to their high dimensional accuracy, excellent surface finish, and cost-effectiveness [3,4,5]. The principle of 3D printing is based on the photopolymerisation process, in which UV light selectively cures photosensitive resins to create three-dimensional structures with a resolution ranging from a few tens to a few hundred micrometres [6].

Current trends indicate a paradigm shift in VAT photopolymerisation towards high-performance and functional applications rather than mere prototyping. As highlighted by Fagotto-Clavijo et al. [7], the strategic advancement of LCD and DLP systems now enables the processing of complex scaffolds and multi-material structures with unprecedented precision. Furthermore, comparative studies by Katheng et al. [8] have established that modern LCD systems can achieve mechanical properties competitive with industrial SLA machines, making them increasingly viable for end-use composite manufacturing. This evolution is supported by continuous improvements in resin formulations, including triboactive polymers [9] and self-healing networks [10], which expand the theoretical boundaries of what photopolymerisation can achieve in terms of material longevity and functionality.

Recent progress in photopolymerisation is making it possible to combine textiles with 3D-printed polymers, which is leading to a new generation of multifunctional composites [11,12,13]. Integrating textiles directly during 3D printing is better than traditional ways of making composites because it lets you fine-tune mechanical properties, cut processing times in half, and create complex hybrid structures in one step [14,15,16]. Functional textile–polymer composites are being developed because there is a growing need for lightweight, flexible, and strong materials in the aerospace, automotive, wearable electronics, and biomedical fields [17,18,19]. Making textile composites used to be a long process that involved preparing the fabric, soaking it in resin, and then putting it all together. Each step made the process more complicated and expensive [20,21,22]. LCD vat photopolymerization is a more straightforward method because it bonds photopolymers directly to textile substrates. This method cuts out extra steps and, most importantly, opens up new design options that weren’t possible before. The strength of the bond at the textile–polymer interface is what finally decides how well these hybrid structures work mechanically [23,24,25,26]. The fiber–matrix interface is the crucial area where stress distribution and crack propagation behaviors are determined in fiber-reinforced polymer composites (FRPCs). The hallmarks of adhesive failure at the interface, which is brought on by insufficient interfacial bonding, are debonding and separation between the constituents. However, strong interfacial adhesion can cause failure mechanisms to change from adhesive to cohesive modes, meaning that fracture happens inside one of the component materials instead of at the interface. The transition from interfacial to adherend-limited failure is a desirable state when the bond strength is greater than the cohesive strength of the weaker component [27]. The theoretical framework of polymer–textile adhesion relies heavily on the mechanical interlocking mechanism, often described as a ‘micro-riveting’ effect. Tang et al. [28] demonstrated that when resin viscosity is sufficiently low to penetrate porous substrates, the resulting soft–rigid connection significantly outperforms traditional adhesive layers. However, this interaction is complex due to the inherent anisotropy of additively manufactured parts. Sun et al. [29] noted that light-oriented printing can induce specific anisotropic behaviours in the polymer matrix, which must be compatible with the orthotropic nature of woven fabrics [30]. Recent fracture mechanics models for fibre-reinforced composites suggest that damage evolution in such hybrid interfaces is governed not only by chemical affinity, but also by the geometric constraints of the fibre architecture [31,32]. Therefore, achieving adherend-limited failure requires a critical balance between resin infiltration depth and curing degree, ensuring that the interface creates a gradient of stiffness rather than a stress concentration point [33].

The vat photopolymerisation success depends on two key processing decisions which are the layer thickness and the UV exposure time [34,35,36]. These factors cannot be avoided and therefore they determine not only whether a structure is printed, but also whether it performs as intended.

Layer thickness controls three interconnected factors: UV light penetration depth, resin flow between layers, and inter-layer adhesion [37]. Thinner layers produce sharper details but require longer printing times. UV exposure time is the other critical variable. It determines how completely the photoinitiation reactions proceed—essentially deciding whether the polymer network is strong or brittle. While too much exposure time results in over-curing, which causes brittleness, trapped stress, and microscopic cracks, too little exposure time results in a weak, defect-ridden part. The difficulty comes from the way these two parameters interact, meaning that changing one usually necessitates changing the other.

The factors that collectively affect the performance of woven fabrics are fiber composition, weave structure, fabric density, and surface treatment [38]. Blends of cotton and polyester are a good example of this idea. They combine the engineering benefits of polyester, such as dimensional stability, strength, and durability, with the inherent advantages of cotton, such as comfort and moisture absorption [39]. Because it successfully strikes this balance, the 65% polyester/35% cotton blend has become the industry standard for technical textiles [40].

What determines the strength of woven fabric? The mechanical interlock between the warp and weft threads, yarn-to-yarn friction, and the fibers’ own tensile strength are the three factors that contribute to the solution [41,42,43]. However, durability is just as important as strength. The failure of various fabrics under shear loading varies. Some experience yarn slippage, others see fibre breakage, and some develop localised tearing. The actual failure mode depends entirely on how the fabric is woven and what loads it experiences [44]. Direct photopolymer bonding to textiles using pause-and-bond techniques in LCD systems has received little attention, although researchers have thoroughly examined photopolymer properties and textile-polymer composites. Few studies have investigated vat photopolymerisation for textile bonding; most research on textile-integrated additive manufacturing has focused on FDM and extrusion processes [13,14,15]. Importantly, the effects of layer thickness and UV exposure duration on the strength of the textile-photopolymer bond have not been systematically studied. Optimising processing parameters becomes crucial for increasing reliability and reducing resource consumption if they significantly affect interfacial adhesion. However, if bonds remain strong under various processing conditions, this presents an alternative opportunity: using minimal processing parameters (shorter exposures, thinner layers) without compromising performance. Such findings would enable more sustainable manufacturing while maintaining quality [45]. It should be noted that all failures were adherend-limited—regardless of processing parameters—which suggests a specific direction for future work. Rather than attempting to strengthen the interface, efforts should focus on improving the textile substrate itself [20].

Beyond mechanical performance, theoretical discourse in additive manufacturing is increasingly focusing on process sustainability. Maturi et al. [46] argue that the next generation of AM processes must prioritise resource efficiency, specifically by minimising resin consumption and energy-intensive post-processing. This ‘green manufacturing’ perspective suggests that parameter optimisation should target not only maximum strength but also the most efficient use of materials to achieve the required safety factor [47]. Consequently, understanding the threshold parameters—the minimum exposure and thickness required to shift failure from the interface to the adherend—becomes a critical research objective for sustainable composite fabrication [48,49].

Using a pause-and-bond technique, this study examines the failure mechanisms and lap-shear strength of woven fabric–photopolymer joints made by LCD vat photopolymerisation. The effects of layer thickness (0.01, 0.025, 0.05 mm) and UV exposure duration (40, 80, 120 s) on bond performance are methodically assessed. A robust methodology for evaluating interfacial adhesion and determining process parameters suitable for creating future textile-integrated photopolymer sandwich structures is emphasised.

2. Materials and Methods

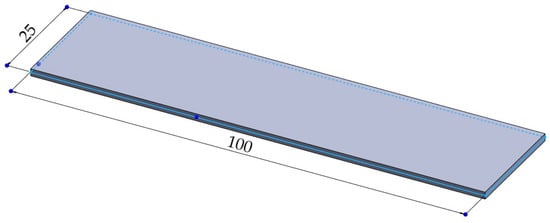

LCD vat photopolymerization was performed using an Anycubic Photon Mono X 6Ks printer (Anycubic, Shenzhen, China) equipped with a 405 nm LED light source. The printer features are 9.1″ 6K monochrome LCD screen with 5760 × 3600 pixel resolution, providing 34 µm XY resolution and variable Z-axis layer thickness control from 0.01 to 0.20 mm. Standard photopolymer resin (eSUN S200 Light Blue, Shenzhen Esun Industrial Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, Guangdong, China) compatible with 405 nm wavelength was used throughout the study. The resin was stored at room temperature (20–25 °C) and mixed thoroughly before each printing session to ensure homogeneous composition. Plain woven fabric with 65% polyester and 35% cotton with an approximate weight of 200 g/m2 was selected as the textile substrate. Fabric samples were cut into rectangular strips (100 mm × 50 mm) and conditioned at 21 ± 2 °C and 65 ± 2% relative humidity for 24 h prior to testing according to standard textile conditioning procedures. Test specimens were designed using SolidWorks Student Standard 2024 SP5.0 CAD software (Dassault Systèmes, Vélizy-Villacoublay, France). Polymer specimens were modeled as the rectangular blocks with the dimensions of 100 mm × 25 mm × 1.6 mm to accommodate single lap joint testing requirements (Figure 1). Models were created as solid bodies and exported in the STL format with the fine resolution settings (deviation tolerance: 0.047 mm, angular tolerance: 10°). STL files were processed using Anycubic Photon Workshop v3.1.4 slicing software (Anycubic, Shenzhen, China). STL files were then imported and oriented with the bonding surface parallel to the build platform. The printer’s default parameters were configured as follows: layer thickness 0.05 mm, normal exposure time 2.5 s, bottom layer exposure time 20 s, and 5 bottom reinforcement layers to ensure build platform adhesion during initial printing stages.

Figure 1.

CAD model of the specimen.

Layer thickness and UV exposure time were selected as the primary experimental factors because they are the two independent control variables available to operators in LCD vat photopolymerisation systems. Previous literature on vat photopolymerisation [34,35,36] has established that these parameters influence polymer network development and inter-layer bonding quality. Specifically, in the context of textile-polymer bonding, controlling these variables allows precise regulation of the extent to which the liquid photopolymer resin infiltrates and bonds to textile fibres during the final curing stage. The selected numerical levels span practical manufacturing ranges: the layer thickness values (0.01, 0.025, 0.05 mm) represent relevant printing conditions, while the UV exposure times (40, 80, 120 s) cover sub-stoichiometric to moderately over-cured states. This bounded experimental design enables identification of whether textile-photopolymer bonding exhibits threshold sensitivity or robust performance across realistic processing windows.

A full factorial design (32) was implemented with the two primary factors: layer thickness (0.01, 0.025, 0.05 mm) and exposure time (40, 80, 120 s), resulting in nine unique parameter combinations and the textile as a constant. Five replicate specimens were prepared for each combination, yielding 45 total samples for mechanical testing. While stereolithography on textiles has been reported [12], these approaches involve direct printing with textiles fully immersed in resin. The pause-and-bond methodology presented here is an original contribution, employing controlled print interruption to place textiles after partial curing, enabling superior interfacial control compared to standard vat photopolymerisation approaches.

The 3D printing protocol involved a controlled pause-and-bond methodology:

- Initial Printing: Polymer blocks were printed to n − 1 layers using standard exposure parameters (20 s bottom exposure time) and layer thickness was set to the target value (0.01, 0.025, or 0.05 mm)

- Print Interruption: Immediately before the final layer, printing was paused using the printer’s pause function. The overall number of layers was given by the slicer software in dependence of the layer thickness, e.g., if the layers thickness is set to 0.01 mm the slicer software gives total of 159 layers (n), therefore, the printer should be paused at layer 158 (n − 1).

- Build Plate Preparation: The build plate was carefully removed and excess uncured resin was cleaned from the surface using 96% Ethyl Alcohol and lint-free cloth;

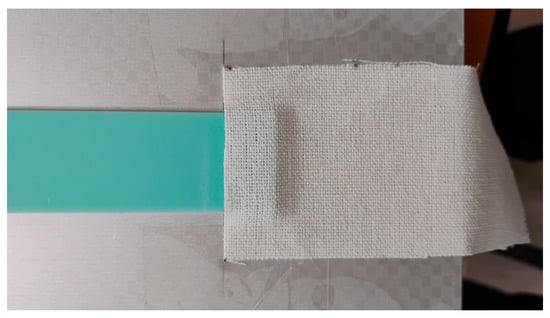

- Textile Placement: Textile fabric strips were positioned on the printed polymer surface to create a 12.7 mm overlap length, consistent with EN ISO 4587:2003; Adhesives—Determination of tensile lap-shear strength of rigid-to-rigid bonded assemblies. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003 [50], single lap joint geometry. Fabric positioning was secured using adhesive tape applied to areas outside the bonding zone (Figure 2);

Figure 2. Textile placement on the bonding zone.

Figure 2. Textile placement on the bonding zone. - Parameter Adjustment: Normal Exposure Time was adjusted in the printer settings to the designated experimental value (40, 80, or 120 s);

- Final Layer Curing: The build plate was returned to the printer and printing resumed to cure the final bonding layer under the specified experimental conditions;

- Post-Processing: Completed specimens were removed from the build plate and excess resin was cleaned using Ethyl Alcohol 96%. No post-curing was applied to maintain pure 3D printing conditions (Figure 3a).

Figure 3. (a) Single-lap joint after 3D printing and cleaning; (b) Markers on the textile side.

Figure 3. (a) Single-lap joint after 3D printing and cleaning; (b) Markers on the textile side.

According to the EN ISO 4587:2003, each specimen is typically 100 mm in length and 25 mm in width. Therefore, the specimen must be trimmed on the textile side to the standardised dimensions. The markers define the precise area that will form the joint (Figure 3b). Using sharp scissors, any excess textile extending beyond these markers is carefully removed. Additionally, to ensure correct placement within the machine grips, markers are applied to both the textile and the resin surface before mounting on the machine. Single-lap shear strength testing was performed using a Shimadzu AGS-X 10 kN universal tensile testing machine (Shimadzu Europa GmbH, Duisburg, Germany). Specimens were mounted with precision alignment marks applied to ensure correct positioning within the machine grips. The grip separation distance was set to 120 mm with the crosshead speed of 1 mm/min and 50 Hz of the data acquisition frequency.

3. Results

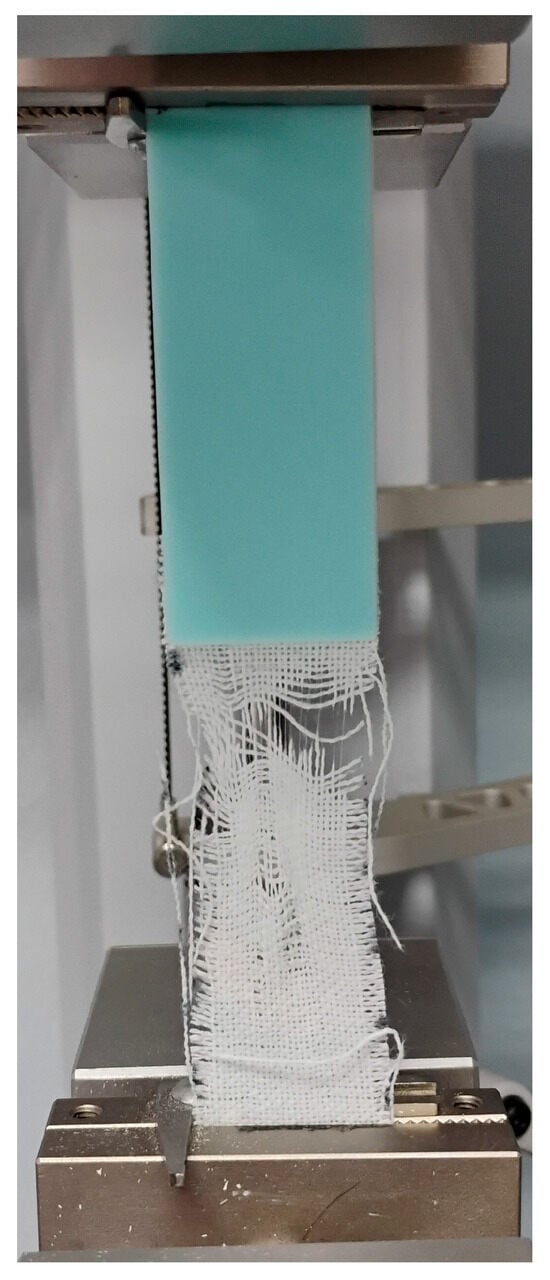

The 100% occurrence of adherend failure (45/45 specimens) demonstrates that the pause-and-bond LCD photopolymerisation methodology consistently produces interfacial bond strengths exceeding the effective strength of the textile substrate under EN ISO 4587:2003 loading conditions (Figure 4). This outcome validates the fundamental hypothesis that the controlled resin infiltration during final layer curing enables robust mechanical interlocking at the textile–photopolymer interface. The failure loads across all 45 specimens ranged from 247 N to 277.14 N, with the minimal variation between the parameter combinations (Table 1). Converting to apparent shear stress using the nominal overlap area (12.7 mm × 15 mm = 190.5 mm2), the overall mean shear strength was 1.38 ± 0.04 MPa (range: 1.30–1.45 MPa).

Figure 4.

Adherend-limited failure mode.

Table 1.

Apparent Shear Strength by parameter combination.

The narrow strength distribution with a coefficient of variation of approximately 3.1% reveals that the variability comes from the natural differences in cotton fibre properties and yarn construction, not from the inconsistencies in the bonding process itself. Across all tested parameter combinations, the bond performance remained statistically equivalent, which means that the failure is limited by the substrate, not the interface.

Statistics

For experimental planning, data processing, and statistical analysis, the software Design-Expert version 22.0.8 (Stat-Ease, Inc., 1300 Godward Street Northeast, Suite 6400, Minneapolis, MN 55413, USA) was employed. While force–displacement plots provide some basic insights, more precise quantitative information about the effects of individual factors on the measured outputs can be obtained through DOE and ANOVA analysis [51].

Two-way ANOVA with layer thickness and exposure time as the independent factors revealed no statistically significant effects on the measured shear strength (Table 2). Post-hoc power analysis confirmed adequate statistical power (β > 0.90) to detect meaningful differences (≥0.05 MPa), giving out Type II error. The absence of the parametric effects is consistent with the adherend-dominated failure, where measured strength reflects cotton substrate properties rather than interfacial bond quality.

Table 2.

Two-way ANOVA results.

Since all parameter combinations achieved adherend-limited performance, process optimization focuses on resource efficiency rather than strength maximization. The combination of 0.01 mm layer thickness and 40 s exposure time represents the most resource-efficient condition, offering:

- Minimum processing time: 40 s vs. 120 s (67% time reduction);

- Lowest resin consumption: Thinner layers require less material per bond;

- Maintained reliability: 100% adherend failure consistency.

This finding enables significant process optimization for high-volume manufacturing applications where cotton textile serves as the mechanical limiting factor. Conversely, the 0.05 mm/120 s combination may be preferred for applications requiring maximum environmental durability or fatigue resistance, despite equivalent quasi-static strength.

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with the Literature

The tensile lap-shear performance of textile–polymer joints is significantly influenced by the fibre composition and the corresponding interfacial adhesion mechanisms. In this study, the 65% polyester–35% cotton blend exhibited hybrid adhesion behaviour, reflecting the differing surface properties and chemical affinities of the two fibre types. The cotton component enabled the polymer matrix to achieve mechanical interlocking and anchorage in specific areas, while the polyester component, being less reactive and less wettable, provided only limited interfacial bonding, which affected both the strength and the failure mode.

The role of fibre type in determining failure behaviour is increasingly clear from recent research. When textiles contain sufficient natural fibres, something predictable happens: failure occurs within the material itself, not at the adhesive interface. The efficiency of fibre–matrix interlocking renders the interface stronger than the adherend itself, thereby becoming the controlling factor in failure. Hybrid fabrics like polyester–cotton blends show the same pattern [52].

4.2. Microstructural Mechanisms Underlying Adherend-Limited Failure

Three interconnected physical mechanisms that strengthen the textile–photopolymer interface beyond the intrinsic cohesive strength of the woven substrate are responsible for the consistent occurrence of adherend-limited failure (100% of specimens) in all 45 samples.

- (a)

- Controlled Resin Infiltration: The pause-and-bond methodology allows uncured liquid photopolymer to penetrate textile interstices immediately before the final layer. Unlike conventional vat photopolymerisation, where textiles become fully saturated, this approach restricts infiltration to the final layer interface, enabling resin to flow into and around individual cotton and polyester fibres (estimated yarn spacing: 150–300 µm). According to the layer thickness values used, this creates a mechanically interlocked boundary zone that is roughly 0.5–2 mm thick.

- (b)

- Mechanical Fibre Anchoring: The 65/35 cotton–polyester blend’s cotton fibres have a distinctive fibrillar surface texture. The uncured photopolymer wets and conforms to this texture. After UV polymerisation, the photopolymer network permanently locks around these surface features, producing micro-mechanical interlocking comparable to adhesive anchoring in fibre-reinforced composites. Polyester fibres, being synthetic and smoother, contribute less to mechanical interlocking [53].

- (c)

- Cohesive Weakness of the Woven Substrate: Woven fabrics derive their tensile strength from the mechanical crimp between orthogonal warp and weft threads, yarn-to-yarn friction, and the tensile strength of individual fibres. Under lap-shear loading, the shear plane intersects both warp and weft directions, requiring simultaneous failure of multiple load-bearing yarn crossings. The measured shear strength (1.38 ± 0.04 MPa) indicates the initiation of yarn slippage or fibre micro-fracture within the textile, which consistently occurs before interfacial debonding. This suggests that the critical stress for internal textile yarn displacement is lower than the interfacial strength (estimated at >1.5–1.6 MPa based on ANOVA statistical power).

4.3. Process Parameter Independence

All the tested parameter combinations exceeded the critical threshold required for the adherend-limited performance. This process demonstrates the noticable robustness in providing a significant manufacturing latitude without compromising bond quality. Furthermore, the statistical equivalence of all combinations suggests that the interfacial bond formation is not the limiting factor within the investigated ranges, but rather the inherent mechanical properties of the textile substrate. The narrow coefficient of variation (3.1%) across all parameter groups supports this interpretation, as observed scatter reflects natural variability in fiber properties, yarn construction, and local fabric architecture rather than process-induced variations.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that adherend-limited failure in woven fabric–photopolymer joints (65% polyester/35% cotton) is consistently achieved by LCD vat photopolymerisation using the pause-and-bond methodology. All 45 specimens (100%) failed within the textile substrate, with a mean lap-shear strength of 1.38 ± 0.04 MPa (range: 1.30–1.45 MPa). Across the entire tested parameter space, interfacial bond strength consistently exceeded the cohesive strength of the woven fabric, as confirmed by two-way ANOVA, which found no statistically significant parametric effects (p > 0.05). This adherend-limited performance confirms the robustness of the pause-and-bond approach for textile bonding applications. The adherend-limited failure observed across all parameter combinations allows process optimisation without the usual strength-reliability trade-offs. The minimum resource-efficient condition (0.01 mm/40 s), compared to the maximum-parameter condition (0.05 mm/120 s), offers measurable benefits, including a 67% reduction in final-layer cure time (saving 80 s per bond). A resin volume per layer thickness of 0.01 mm requires 1.6 cm3 of resin per specimen (100 mm × 25 mm × 0.01 mm), while a 0.05 mm thickness requires 8 cm3 of resin per specimen. The resin volume difference is 6.4 cm3 saved per bond (an 80% reduction in bonding-layer material).

Future work should systematically investigate multiple fabric weights (60–200 g/m2) to identify critical substrate strength thresholds, and alternative loading modes (peel tests, cyclic fatigue) that may be more sensitive to interfacial quality variations. Environmental ageing (moisture, temperature cycling) should be assessed to determine long-term durability differences, and different textile constructions (twill, satin weaves) should be tested to validate the generalisability of the methodology. Such investigations would provide comprehensive design guidance for textile-integrated LCD printing across diverse application requirements. Therefore, the applications of textile-integrated additive manufacturing will be immediately impacted by the strong adherend-limited bonding shown across all parameter combinations. Wearable electronics: The technique eliminates the possibility of interfacial delamination and allows for the dependable attachment of rigid electronic housings to flexible textile substrates. Instead of at potentially disastrous interface locations, the substrate-limited failure mode guarantees that mechanical failure happens predictably within the textile. Intelligent Textiles: With the assurance that the textile-polymer interface won’t turn into the weakest component of the system architecture, functional polymer elements can be directly incorporated during printing. Applications of Reinforcement: With the knowledge that the reinforced area will be stronger than the base material, it becomes possible to strategically place polymers to strengthen textile structures locally.

The next step will be to form textile-reinforced resin sandwich structures and examine their mechanical behaviour. This study has shown that the textile exhibits excellent interlocking with the resin and indicates a promising future for textile-reinforced resin structures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.G.; methodology, I.G.; software, V.K.T.; validation, I.G.; formal analysis, I.G.; investigation, I.G.; resources, I.G.; data curation, I.G.; writing—original draft preparation, I.G.; writing—review and editing, I.G.; visualization, I.G.; supervision, M.K. and P.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research paper was funded by the University of Slavonski Brod through the institutional research project Analysis of the influence of design and process parameters of FDM technology on the mechanical and vibrational properties of polyamide PA6 tooth of a cylindrical spur gear for the purpose of optimizing the hybrid infill structure design (ASPFDM-PA6), financed by the European Union—NextGenerationEU. The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the European Union or the European Commission. Neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be held responsible for them.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors reviewed and edited all AI-generated content and take full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LCD | Liquid Crystal Display |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| AM | Additive Manufacturing |

| VP | Vat Photopolymerisation |

| FRPC | Fibre-Reinforced Polymer Composites |

References

- Dogan, H.I.; Mavi, A.; Uzun, G. Development of Additive Manufacturing in the Medical Field: A review. Teh. Vjesn. Tech. Gazzete 2025, 32, 2011–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamazadeh, V.; Shen, M.L.; Ravanbakhsh, H.; Sohrabi-Kashani, A.; Okhovatian, S.; Savoji, H.; Radsic, M.; Juncker, D. High-Resolution Additive Manufacturing of a Biodegradable Elastomer with A Low-Cost LCD 3D Printer. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 13, 2303708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paral, S.K.; Lin, D.-Z.; Cheng, Y.-L.; Lin, S.-C.; Jeng, J.-Y. A Review of Critical Issues in High-Speed Vat Photopolymerization. Polymers 2023, 15, 2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, F.d.C.; Leite, W.d.O.; Rubio, J.C.C. A study of mechanical properties of photosensitive resins used in vat photopolymerization process. J. Elastomers Plast. 2024, 56, 807–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, N.; Srinivasaraghavan Govindarajan, R.; Perry, S.; Coote, K.; Kim, D. Development of Additively Manufactured Embedded Ceramic Temperature Sensors via Vat Photopolymerization. Crystals 2024, 14, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplins, B.W.; Higgins, C.I.; Kolibaba, T.J.; Arp, U.; Miller, C.C.; Poster, D.L.; Zarobila, C.J.; Zong, Y.; Killgore, J.P. Characterizing light engine uniformity and its influence on liquid crystal display-based vat photopolymerization printing. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 62, 103381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagotto-Clavijo, R.; Lodoso-Torrecilla, I.; Diez-Escudero, A.; Ginebra, M.P. Strategic advances in Vat Photopolymerization for 3D printing of calcium phosphate-based bone scaffolds: A review. Bioact. Mater. 2025, 52, 719–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katheng, A.; Prawatvatchara, W.; Chaiamornsup, P.; Sornsuwan, T.; Lekatana, H.; Palasuk, J. Comparison of mechanical properties of different 3D printing technologies. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, A.; Aliyana, A.K.; O’Hara, C.; Kumar, C.; Boal, C.; Goswami, A.; Stylios, G.K.; Mulvihill, D.M.; Pillai, S.C. Direct 3D-printed triboactive polymer layers on stretchable conductive fabric for high-performance T-TENGs. Nano Energy 2025, 142, 111218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, J. Regulation of the Interface Compatibility of the 3D-Printing Interpenetration Networks Toward Reduced Structure Anisotropy and Enhanced Performances. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 32984–32992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keefe, E.M.; Thomas, J.A.; Buller, G.A.; Banks, C.E. Textile additive manufacturing: An overview. Cogent Eng. 2022, 9, 2048439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrendt, D.; Romero Karam, A. Development of a computer-aided engineering–supported process for the manufacturing of customized orthopaedic devices by three-dimensional printing onto textile surfaces. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 2020, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco Urquiza, E.A. Advances in Additive Manufacturing of Polymer-Fused Deposition Modeling on Textiles: From 3D Printing to Innovative 4D Printing—A Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, G.H.; Sotayo, A.; Pei, E. Development and testing of material extrusion additive manufactured polymer–textile composites. Fash. Text. 2021, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirků, P.; Urban, J.; Müller, M.; Kolář, V.; Chandan, V.; Svobodová, J.; Mishra, R.K.; Jamshaid, H. Evaluation of Mechanical Properties and Filler Interaction in the Field of SLA Polymeric Additive Manufacturing. Materials 2023, 16, 4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khajavi, S.H. Additive Manufacturing in the Clothing Industry: Towards Sustainable New Business Models. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, H.C.; Schmelzeisen, D.; Gries, T. 4D Textiles Made by Additive Manufacturing on Pre-Stressed Textiles—An Overview. Actuators 2021, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, S.S.; John, S.; Roy Choudhury, N.; Dutta, N.K. Additive Manufacturing of Polymer Materials: Progress, Promise and Challenges. Polymers 2021, 13, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilek, E.; Yildirim, M.; Uzun, M. Additive manufacturing (3D printing) in technical fashion industry applications. Tekst. Ind. 2021, 69, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.K.; Petru, M.; Behera, B.K.; Behera, P.K. 3D Woven Textile Structural Polymer Composites: Effect of Resin Processing Parameters on Mechanical Performance. Polymers 2022, 14, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tichý, M.; Kolář, V.; Müller, M.; Mishra, R.K.; Šleger, V.; Hromasová, M. Quasi-Static Shear Test of Hybrid Adhesive Bonds Based on Treated Cotton-Epoxy Resin Layer. Polymers 2020, 12, 2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionesi, S.D.; Ciobanu, L.; Dumitraș, C.G.; Avădănei, M.; Dulgheriu, I.; Ionescu, I.; Loghin, M.C. FEM Analysis of Textile Reinforced Composite Materials Impact Behavior. Materials 2021, 14, 7380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brighenti, R.; Marsavina, L.; Marghitas, M.P.; Cosma, M.P.; Montanari, M. Mechanical characterization of additively manufactured photopolymerized polymers. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2023, 30, 1853–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goda, I.; Padayodi, E.; Raoelison, R.N. Enhancing fiber/matrix interface adhesion in polymer composites: Mechanical characterization methods and progress in interface modification. J. Compos. Mater. 2024, 58, 3077–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehlivan, M.; Atalik, B.; Gokcesular, S.; Ozbek, S.; Ozbek, B. Optimization of Adhesion in Textile Cord–Rubber Composites: An Experimental and Predictive Modeling Approach. Polymers 2025, 17, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekube, B.M.; Badiola, J.H.; Larreategi, P.; Ares, F.; Chiminelli, A.; Valero, C.; Ozgur, T. Metal-composite hybrid joint adhesion and testing optimization for electric vehicle applications. J. Adhes. 2025, 101, 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekunle, F.; Li, A.; Vallabh, R.; Seyam, A.-F.M. Assessment of Adhesion in Woven Fabric-Reinforced Laminates (FRLs) Using Novel Yarn Pullout in Laminate Test. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Wang, H.; Ren, J.; Jiang, X. Highly robust soft-rigid connections via mechanical interlocking for assembling ultra-stretchable displays. npj Flex. Electron. 2024, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Chen, S.; Qu, B.; Wang, R.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Gao, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhuo, D. Light-oriented 3D printing of liquid crystal/photocurable resins and in-situ enhancement of mechanical performance. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, H.S.; Mostafa, N.H. Tensile and Impact Properties of Woven Glass Fibers Epoxy Composites Filled With Short Glass Fibers. J. Eng. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 28, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.-J.; Shi, X.; Sun, X.; Feng, X.-Q.; Zhao, Z.-L. Fracture mechanics model of biological composites reinforced by helical fibers. Compos. Struct. 2024, 346, 118430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruhn, P.; Koske, D.; Storck, J.L.; Ehrmann, A. Three-Dimensional Printing by Vat Photopolymerization on Textile Fabrics: Method and Mechanical Properties of the Textile/Polymer Composites. Textiles 2024, 4, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Bai, W.; Cheng, X.; Tian, J.; Wei, D.; Sun, Y.; Di, P. Effects of printing layer thickness on mechanical properties of 3D-printed custom trays. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 126, 671.e1–671.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pszczółkowski, B.; Zaborowska, M. Effect of Layer Exposure Time in SLA-LCD Printing on Surface Topography, Hardness and Chemical Structure of UV-Cured Photopolymer. Lubricants 2025, 13, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radyantho, K.D.; Situmeang, R.E.; Ismail, A.I. Post-Curing and Layer Thickness Variations Effect on Tensile Strength of Resin 3D Print. Key Eng. Mater. 2025, 1020, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Wang, P.; Yan, X. Effect of Process Parameters and Layer Thickness on the Quality and Performance of Ti-6Al-4V Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting. Coatings 2021, 11, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj Ahmad, K.; Mohamad, Z.; Khan, Z.I.; Habib, M. Tailoring UV Penetration Depth in Photopolymer Nanocomposites: Advancing SLA 3D Printing Performance with Nano-fillers. Polymers 2025, 17, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patti, A.; Acierno, D. Materials, Weaving Parameters, and Tensile Responses of Woven Textiles. Macromol 2023, 3, 665–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, N.; Repon, M.R.; Pranta, A.D.; Islam, S.; Khan, A.A.; Malik, A. Effect of cotton-polyester composite yarn on the physico-mechanical and comfort properties of woven fabric. SPE Polym. 2024, 5, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Reddy, N.; Yang, Y. Reusing polyester/cotton blend fabrics for composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2011, 42, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sülar, V.; Öner, E.; Okur, A. Roughness and frictional properties of cotton and polyester woven fabrics. Indian J. Fibre Text. Res. 2014, 38, 349–356. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Li, X.; Krugl, S.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, P. Towards yarn-to-yarn friction behavior in various architectures during the manufacturing of engineering woven fabrics. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2024, 185, 108363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajalakshmi, M.; Kubera Sampath Kumar, S.; Vasanth Kumar, D.; Siva Jagadish Kumar, M.; Prakash, C. Effect of plasma sericin glutaraldehyde treatments on the low stress mechanical properties of micro denier polyester/cotton blended fabric. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Islam, M.M.; Dey, S.C.; Hasan, N. An approach to improve the pilling resistance properties of three thread polyester cotton blended fleece fabric. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohut, S.; Schwentenwein, M. Vat Photopolymerization Additive Manufacturing of Functionally Graded Materials: A Review. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2022, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maturi, M.; Locatelli, E.; Sanz de Leon, A.; Franchini, M.C.; Molina, S.I. Sustainable approaches in vat photopolymerization: Advancements, limitations, and future opportunities. Green Chem. 2025, 27, 8710–8754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheadle, A.M.G.; Maier, E.; Palin, W.M.; Tomson, P.L.; Poologasundarampillai, G.; Hadis, M.A. The impact of modifying 3D printing parameters on mechanical strength and physical properties in vat photopolymerisation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatua, V.; Gurumoorthy, B.; Ananthasuresh, G.K. A vat photopolymerization process for structures reinforced with spatially steered flexible fibers. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 86, 104183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahari, S.; Melenka, G.W. Analysis of the interface porperties of multimaterial fused filament fabricated (FFF) printed polymer composite structures. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2025, 142, 104074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN ISO 4587:2003; Adhesives—Determination of Tensile Lap-Shear Strength of Rigid-to-Rigid Bonded Assemblies. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- Tiwary, V.K.; Arunkumar, P.; Malik, V.R. Investigations on microwave-assisted welding of MEX additive manufactured parts to overcome the bed size limitation. J. Addit. Manuf. Process. 2023, 1, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Meng, Y. Mechanical interlocking of cotton fibers on slightly textured surfaces of metallic cylinders. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, D.; Amza, C.G. 3D Printing onto Textiles: A Systematic Analysis of the Adhesion Studies. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 11, e586–e606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.